Abstract

Toxoplasmic encephalitis (TE) is a life-threatening disease of immunocompromised individuals and has increased in prevalence as a consequence of AIDS. TE has been modeled in inbred mice, with CBA/Ca mice being susceptible and BALB/c mice resistant to the development of TE. To better understand the innate mechanisms in the brain that play a role in resistance to TE, nitric oxide (NO)-dependent and NO-independent mechanisms were examined in microglia from BALB/c and CBA/Ca mice and correlated with the ability of these cells to inhibit Toxoplasma gondii replication. These parameters were measured 48 h after stimulation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) gamma interferon (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), or combinations of these inducers in T. gondii-infected microglia isolated from newborn mice. CBA/Ca microglia consistently produced less NO than did BALB/c microglia after stimulation with LPS or with IFN-γ plus TNF-α, and they inhibited T. gondii replication significantly less than did BALB/c microglia. Cells of both strains treated with IFN-γ alone significantly inhibited uracil incorporation by T. gondii, and NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (NMMA) treatment did not reverse this effect. In cells treated with IFN-γ in combination with other inducers, NMMA treatment resulted in only partial recovery of T. gondii replication. This IFN-γ-dependent inhibition of replication was not due to generation of reactive oxygen species or to increased tryptophan degradation. These data suggest that NO production and an IFN-γ-dependent mechanism contribute to the inhibition of T. gondii replication after in vitro stimulation with IFN-γ plus TNF-α or with LPS. Differences in NO production but not in IFN-γ-dependent inhibition of T. gondii replication were observed between CBA/Ca and BALB/c microglia.

In individuals with functional immune systems, infection by Toxoplasma gondii is limited by a strong innate and acquired T-cell-mediated immune response. This response drives the actively replicating tachyzoites to encyst and convert into the quiescent bradyzoite form (10, 11). The cysts persist in various tissues, including the brain, heart, and skeletal muscle (43), for the life of the individual. When the immune system is compromised, as during infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1, toxoplasmic encephalitis (TE) occurs as a result of the recrudescence of these cysts and the failure of the host to generate a protective immune response in the brain (25). TE is frequently a severe life-threatening disease in these individuals. Only approximately one-third of seropositive AIDS patients infected with T. gondii will develop TE (14, 26). This implies that genetic differences in host resistance may play a role in control of T. gondii infection in the central nervous system (CNS) and supports the importance of understanding these differences.

Inbred mice have been used to determine what immunological parameters are important in the development of resistance to TE (3, 8, 18, 42). In these mice, initial infection with T. gondii stimulates interleukin-12 (IL-12) production, probably from dendritic cells in the spleen (35). Stimulation with IL-12 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) results in the production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) by natural killer (NK) cells (39, 49) and, in the later stages of infection, by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (12). IFN-γ plays a major role in the control of both acute infection and reactivation of latent cysts in the brain (40, 41). IFN-γ stimulation of cells of the macrophage lineage results in secretion of TNF-α, and synergistic stimulation by IFN-γ and TNF-α, rather than cytotoxic effector functions, is critical for host resistance (22, 49). Yap and Sher have demonstrated that both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells act as IFN-γ-and TNF-α-dependent effectors of resistance to T. gondii (48). Generation of reactive nitrogen intermediates, such as nitric oxide (NO), through stimulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) by IFN-γ and TNF-α is one of the major mechanisms of resistance to parasitic infection in hematopoietic cells (1, 6, 19–21) of TE-susceptible mice. IFN-γ also acts in concert with IL-1 or IL-6 to stimulate NO production (8, 16, 46). In addition, NO-independent mechanisms are stimulated by the actions of IFN-γ in concert with other cytokines. IFN-γ induces macrophage-mediated killing of intracellular parasites by stimulating increases in the production of reactive oxygen metabolites (28, 30) and inhibits T. gondii replication via induction of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and consequent degradation of tryptophan (29, 32). Additional NO-independent mechanisms that have not yet been identified are involved in resistance of macrophages as well as astrocytes to T. gondii (16, 23).

Studies with inbred mice have demonstrated that the factors involved in resistance to chronic infection in the CNS differ from those required for resistance to acute infection. The most notable difference in an acute compared to a chronic response appears to be the role of NO. Use of iNOS knockout mice has demonstrated that resistance to acute infection with T. gondii can occur in the absence of NO but that iNOS-deficient mice develop lesions in the CNS and do not survive chronic infection (37). Bohne et al. have proposed a role for NO in triggering conversion of the tachyzoite to the bradyzoite form of T. gondii (2). This role would be critical in the control of chronic infection in the CNS.

Infection of in vitro cultures of primary astrocytes and microglia has been used to study host resistance to T. gondii in the CNS. Such cultures have demonstrated that astrocytes support growth of the tachyzoite stage and do not mount a NO-dependent defense against the organism (15, 31). However when astrocytes are stimulated with IFN-γ, T. gondii replication is inhibited via a NO-independent mechanism (16). Microglial cells, the functional equivalents of macrophages in the CNS, possess an intrinsic NO-dependent inhibitory activity against T. gondii (5, 7).

We have studied mechanisms of resistance to chronic T. gondii infection in the CNS in inbred mice that differ in resistance to TE. To test the hypothesis that microglial cells from TE-susceptible and -resistant mice respond differently to activating cytokines, we isolated primary microglial cells from TE-susceptible CBA/Ca and TE-resistant BALB/c mice and, treating cells from both strains in the same experiment, measured both NO production and the effects of activation on T. gondii replication. This work demonstrated greater NO production in microglia from TE-resistant mice than in those from TE-susceptible mice. A strong correlation was observed between the increased NO production and increased ability to inhibit T. gondii replication in vitro. When microglial cells of both strains were stimulated with IFN-γ alone, substantial inhibition of T. gondii replication occurred in the absence of NO production, suggesting that this NO-independent mechanism for inhibition of T. gondii replication did not differ between microglia from BALB/c and CBA/Ca mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 10× minimum essential medium, penicillin-streptomycin, Hanks balanced salt solution, and phosphate-buffered saline used for dissections and cell culture were obtained from Life Technologies (Bethesda, Md.), as were trypsin and IFN-γ. l-Glutamine was obtained from BioWhittaker (Walkersville, Md.). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was obtained from List Biologicals (Campbell, Calif.), and TNF-α was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn.)., Catalase and NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (NMMA) was obtained from Calbiochem-Novabiochem (La Jolla, Calif.). Defined fetal bovine serum (FBS) (low endotoxin, lot matched) was obtained from HyClone Laboratories (Logan, Utah). Cytokines for microglial cell culture growth, natural human macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1), and recombinant murine IL-3 were obtained from Biosource International (Camarillo, Calif.). Benzoic acid (sodium salt), d-mannitol, diazabicyclooctane (DABCO), sulfanilamide, sodium nitrite, and l-tryptophan were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.); N-(1-naphthyl)ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (NEDD) was obtained from Fluka (Ronkonkoma, N.Y.), and [5,6-3H]uracil was obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Arlington Heights, Ill.).

Primary microglial cultures.

Primary cultures of microglial cells were obtained from newborn mice of the BALB/c (Simonsen Laboratories, Gilroy, Calif., and B&K Universal, Fremont, Calif.) and CBA/Ca (B&K Universal) strains by a modification of the method of Chao et al. (4). Briefly, brains were removed on the day of birth and the neocortices were removed, pooled, minced, and trypsinized (in 0.09% trypsin) for 30 to 45 min at 37°C. The cells were triturated, filtered through a 70-μm-pore-size filter, and plated in 75-cm2 Falcon flasks (VWR Scientific, Chicago, Ill.) in medium stock prepared using minimal essential medium (supplied without bicarbonate or glutamine) and glucose-bicarbonate by the method of Rose et al. (36). To this preparation were added 20% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml and 100 μg/ml respectively), CSF-1 (0.4 ng/ml), and IL-3 (0.4 ng/ml). The doses of CSF-1 and IL-3 were optimized for these cultures by U. Gawlick (University of Illinois) (personal communication). Cells from three hemispheres were plated per 75-cm2 flask. The medium was replenished on day 1 after plating, and the cells were fed every other day with freshly prepared medium. Flasks were shaken on an orbital shaker at 180 rpm for 20 min on day 8 to remove oligodendrocytes. Microglial cells were isolated on day 12 by shaking for 2 h at 180 rpm and passing cells through a 20-μm-pore-size filter. Microglial cells were plated in 96-well Falcon plates at a density of 1.5 × 104 to 1.8 × 104 cells/well in 200 μl of medium. The cultures reached confluency on days 7 to 9 after plating and were then used for experiments. Cells from both strains of mice were isolated at the same time, treated identically, and used for experiments at the same time, with nitrite and [3H]uracil incorporation by T. gondii being assayed in parallel. The cells were also plated in wells of 24-well Falcon plates, stained for nonspecific esterase by the method of Yam et al. (47), and confirmed to be >98% microglial cells.

T. gondii growth and experimental infection.

Tachyzoites of the PLK strain of T. gondii (obtained from J. Boothroyd, Stanford University, Stanford, Calif.) were maintained in vitro in human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) by passaging twice a week in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM l-glutamine. T. gondii was passaged by infecting HFF cultures at 8 × 105 organisms per 25-cm2 flask and allowing replication to occur for 3.5 days before parasites were transferred to fresh HFF. When T. gondii was to be used in an experiment, parasites were allowed to replicate in HFF for 2.5 days before use, to ensure that the organisms would be in an exponential growth state when microglia were infected. Microglia were infected by adding 105 tachyzoites (25 μl) per well of 96-well plates 24 h after the addition of LPS and other inducers. An equal volume of assay medium was added to control wells, which did not receive T. gondii.

Experimental design.

Experiments to measure NO production and T. gondii replication were conducted simultaneously on microglia from the two mouse strains. Cells in wells of 96-well plates were stimulated with inducers in groups of eight replicates. After 24 h, four of these wells were infected with T. gondii and an equal volume of medium was added to the four remaining wells. The effects of the inducers on NO production, in the presence or absence of T. gondii, was measured in quadruplicate. In parallel, microglia were plated in identical fashion and assayed for T. gondii replication after 48 h. Wells that did not contain T. gondii were used to establish background incorporation of [3H]uracil.

NO measurements.

Griess reagents were used to measure nitrite as an indicator of NO in cell culture supernatants (9). Briefly, 50-μl aliquots of cell culture supernatants were added to 96-well plates, followed by 50 μl of 1% sulfanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid. After a 10-min incubation at room temperature, 50 μl of 0.1% NEDD in water was added, and the incubation was continued for an additional 3 min. Absorbances of the samples were read at 540 nm, using a PowerWave 200 microplate scanning spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, Vt.), and the nitrite concentration was determined by comparison with a standard curve generated using sodium nitrite in water (concentration range, 0 to 100 μM). The absorbance of the blank (consisting of assay medium alone) was subtracted from the value for each sample. Each treatment of microglia was performed in quadruplicate, and each of the wells was assayed in duplicate in the NO assay.

Measurement of T. gondii replication by [3H]uracil incorporation.

T. gondii proliferation was determined by measuring [3H]uracil incorporation by a micromethod developed by Mack and McLeod (27). [3H]uracil is selectively incorporated by replicating T. gondii, because the presence of uracil phosphoribosyltransferase allows the synthesis of UTP and TTP from [3H]uracil (33). [3H]uracil was added to the cultured cells immediately after infection with T. gondii, 24 h after addition of NO inducers. Each well of the 96-well plates, including those with and without T. gondii, received 25 μCi of [3H]uracil. Background counts were measured in wells that did not contain T. gondii but were stimulated in parallel. The plates were harvested after 24 h, using a Tomtec harvester and a slow-pulse wash to ensure that all cells were removed from the wells. After the harvest, 50 μl of 2.5% trypsin in phosphate-buffered saline was added to the cells remaining in each well and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 10 min. After trypsinization, the cells were again harvested onto the same filter mat by using the Tomtec harvester.

Radioactive counts on filter mats were read in a Betaplate liquid scintillation counter (Wallac Instruments, Gaithersburg, Md.). [3H]uracil incorporation by T. gondii in the presence of NO inducers was compared to incorporation in the absence of inducers in BALB/c and CBA/Ca microglia, and the percent inhibition of T. gondii replication was calculated.

Measurement of the effect of l-tryptophan on IFN-γ-induced inhibition of T. gondii replication.

Microglial cells from BALB/c mice were cultured, treated with IFN-γ, and infected with T. gondii as described above. Immediately prior to IFN-γ addition, increasing concentrations of l-tryptophan in medium were added to quadruplicate wells. Final l-tryptophan concentrations ranged from 2.5 to 160 μg/ml. l-Tryptophan was also added to wells in the absence of IFN-γ to monitor potential toxicity and effect on T. gondii replication. At 24 h after IFN-γ treatment, the same concentrations of l-tryptophan were again added to each well, along with 105 tachyzoites of T. gondii per well. T. gondii replication was measured by [3H]uracil incorporation 24 h after infection, as described above.

Measurement of the effect of oxygen scavengers on IFN-γ-induced inhibition of T. gondii replication.

Microglial cells from BALB/c mice were cultured, treated with IFN-γ, and infected with T. gondii as described above. At 3 h before addition of T. gondii, the following oxygen scavengers were added to quadruplicate wells by the methods of Woodman et al. (44): catalase (specific activity, 46,590 U/mg of protein, 16,540 U/mg of material) at final concentrations of 1.15 and 2.3 mg/ml, mannitol at a final concentration of 50 mM, DABCO at 0.5 mM, and benzoic acid at 5 mM. The concentrations initially used by Woodman et al. were modified so that the doses used did not result in toxic effects on T. gondii replication. Fresh dilutions of oxygen scavengers were added immediately before T. gondii addition, and proliferation of T. gondii in the presence of each scavenger was measured by [3H]uracil incorporation 24 h after infection, as described above.

Statistics.

Student's t test was used to detect statistically significant differences in NO production between strains for each treatment group in the experiment in Fig. 1. In the experiment in Fig. 2, differences between treatments and cells treated with medium were compared using Dunnett's method, and differences between treatments were compared across strains by using analysis of variance (ANOVA). All statistical tests (except two that contained observations of zero concentration of NO) were performed on log-transformed data to stabilize the variance.

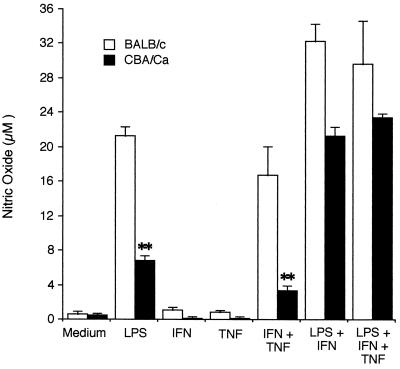

FIG. 1.

NO production by BALB/c and CBA/Ca microglia. Microglia were isolated from newborn BALB/c and CBA/Ca mice as described in Materials and Methods and stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml), IFN-γ (50 U/ml), TNF-α (100 ng/ml), or combinations of these inducers for 48 h in 96-well plates (4 wells/ treatment group). NO production was measured in supernatants as described in the text. Results are expressed as mean and standard deviation for each treatment and are representative of one of six experiments performed. Student's t test was used to compare differences between strains in the effect of various treatments on NO production. ∗∗, P < 0.01.

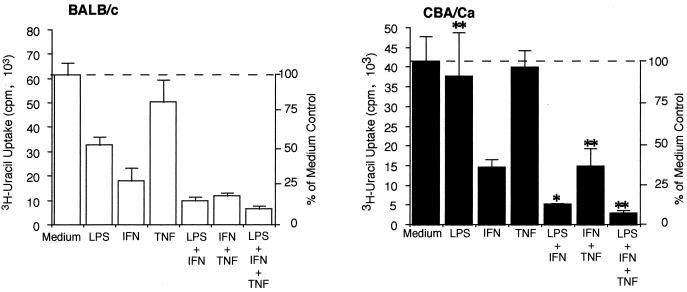

FIG. 2.

T. gondii replication in BALB/c and CBA/Ca microglia. BALB/c and CBA/Ca microglia were isolated as described in Materials and Methods and stimulated in 96-well plates using LPS (10 ng/ml), IFN-γ (50 U/ml), TNF-α (100 ng/ml), or combinations of these inducers. After 24 h, cells were infected with 105 PLK strain tachyzoites per well. Control uninfected wells for each treatment received assay medium alone. [3H]uracil was added to all wells (infected and uninfected), and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 h before uracil incorporation was measured. Results are expressed as mean and standard deviation for each treatment and are representative of one of five experiments performed. ANOVA was used to determine differences between strains in the effects of various treatments on uracil incorporation compared to the respective medium controls. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01.

RESULTS

Since activation of macrophages is known to require a priming signal from IFN-γ as well as a triggering signal (13, 21), cells were treated with the combination of IFN-γ plus LPS or IFN-γ plus TNF-α. As controls, cells were treated with each inducer alone. Finally, cells were treated with LPS plus IFN-γ plus TNF-α to determine whether CBA/Ca microglia under maximal stimulation would produce as much NO as BALB/c microglia did. Since activation with LPS does not occur during infection with T. gondii, treatment with IFN-γ plus TNF-α represents the physiologically relevant activation during T. gondii infection of the CNS. Optimum concentrations of all inducers were determined in preliminary experiments.

Parallel cultures of microglial cells from BALB/c and CBA/Ca mice were stimulated with 10 ng of LPS per ml, 50 U of IFN-γ per ml, 100 ng of TNF-α per ml, or combinations of these inducers for 48 h. Supernatants were removed from quadruplicate cultures in a 96-well plate and assayed in duplicate for nitrite production, using the Griess reagent. The results of a representative experiment are shown in Fig. 1.

Microglia from both strains produced significantly higher levels of NO after treatment with LPS, LPS plus IFN-γ, IFN-γ plus TNF-α, and LPS plus IFN-γ plus TNF-α than after treatment with medium alone. Microglia from CBA/Ca mice produced consistently less NO than did those from BALB/c mice. This difference was most pronounced (P < 0.01) after stimulation with LPS or with IFN-γ plus TNF-α. In the experiment in Fig. 1, CBA/Ca microglia produced 33% of the amount of NO produced by microglia from BALB/c cells after stimulation with LPS. In three separate experiments where microglia were cultured for 48 h with LPS, NO production by microglia from CBA/Ca mice ranged between 32 and 35% of that by microglia from BALB/c mice. In two additional experiments where cells were cultured with LPS for 72 h, CBA/Ca microglia produced 56 and 64%, respectively, of the amount of NO produced by BALB/c microglia.

When microglial cells from both strains of mice were stimulated with either IFN-γ or TNF-α alone, insignificant amounts of NO were produced after 48 h. In experiments not shown, treatment with 100 or 500 U of IFN-γ per ml also did not stimulate significant NO production after 48 h.

When microglia were treated for 48 h with IFN-γ plus TNF-α administered simultaneously, cells from CBA/Ca mice produced only 26% of the amount of NO that was produced by cells from BALB/c mice (P < 0.01). In three experiments in which cells were cultured for 48 h, the levels of NO produced by CBA/Ca cells ranged between 20 and 30% of the levels observed in BALB/c cells. When cells were stimulated for 72 h with IFN-γ plus TNF-α, CBA/Ca microglia produced 46% of the NO that BALB/c microglia produced.

Stimulation with LPS plus IFN-γ or LPS plus IFN-γ plus TNF-α also resulted in consistently higher levels of NO in cells from BALB/c mice than in cells from CBA/Ca mice; however, differences between the two strains were not as dramatic as when cells were stimulated with either LPS alone or IFN-γ plus TNF-α. In three experiments, NO production by CBA/Ca microglia ranged from 53 to 85% of the amount produced by BALB/c microglia after treatment with LPS plus IFN-γ and from 59 to 79% of the amount produced by BALB/c microglia after treatment with LPS plus IFN-γ plus TNF-α.

When microglia from either mouse strain were stimulated with LPS or cytokines for 24 h and then half the cultures were infected with T. gondii and assayed for NO production after an additional 24 h, cells infected with T. gondii showed a significant decrease in NO production compared with cells not infected with T. gondii. This decrease was more pronounced when cells were treated with combinations of inducers that resulted in high levels of NO production, as shown in Table 1. Infection with T. gondii decreased NO production in cells from both strains of mice.

TABLE 1.

Effect of T. gondii infection on nitric oxide production by BALB/c and CBA/Ca microglia

| Mouse strain and expt | T. gondii infection | Nitric oxide production (μM)a after treatment with:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| LPS + IFN-γ | LPS + IFN-γ + TNF-α | ||

| BALB/c | |||

| Expt I | − | 32.3 ± 2.0 | 29.7 ± 5.0 |

| + | 20.2 ± 1.3** | 22.3 ± 1.3* | |

| Expt II | − | 18.0 ± 1.0 | 21.7 ± 1.4 |

| + | 12.6 ± 0.7** | 13.4 ± 0.4** | |

| CBA/Ca | |||

| Expt I | − | 21.3 ± 1.1 | 23.4 ± 0.5 |

| + | 17.5 ± 1.8* | 16.7 ± 1.2** | |

| Expt II | − | 9.6 ± 0.5 | 12.9 ± 0.4 |

| + | 7.0 ± 1.0** | 7.7 ± 1.1** | |

Cells were treated for 24 h with 10 ng of LPS per ml, 50 U of IFN-γ per ml, 100 ng of TNF-α per ml, or combinations of these inducers and then infected with 105 PLK strain tachyzoites per well, and NO production was measured after an additional 24 h of culture. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The results shown are from two of six experiments performed. **, statistically significant (P < 0.01) compared with treatment without T. gondii infection; *, statistically significant (P < 0.05) compared with treatment without T. gondii infection.

The role of NO production as a mechanism of resistance against T. gondii infection in the brain has been actively debated (37, 38, 42). NO production has been thought to be a major mechanism of resistance against parasitic infection in activated macrophages (1) as well as in microglia (6, 7, 20). To determine whether differences in NO production between microglia from BALB/c and CBA/Ca mice corresponded to differences in the ability of these cells to affect T. gondii replication in vitro, cells were stimulated with NO inducers and then infected with T. gondii. T. gondii replication and NO production were measured in parallel cultures. In all experiments, NO production and [3H]uracil incorporation assays were performed on the same cells at the same time points. Data on T. gondii replication from a representative experiment are shown in Fig. 2. In microglia from both strains, treatment with TNF-α alone did not alter the replication of T. gondii. Microglia from BALB/c mice inhibited [3H]uracil incorporation by T. gondii to a significantly greater extent than did microglia from CBA/Ca mice after treatment with LPS, LPS plus IFN-γ, IFN-γ plus TNF-α, or LPS plus IFN-γ plus TNF-α, as determined by ANOVA. Treatment with LPS resulted in 46% inhibition of T. gondii replication in BALB/c microglia but only 4% inhibition of replication in CBA/Ca microglia (compared to their respective controls). Treatment with IFN-γ plus TNF-α caused 81% inhibition of T. gondii replication in BALB/c cells compared to 64% inhibition in CBA/Ca cells.

Although microglia from both strains of mice did not produce measurable amounts of NO after 48 h stimulation with 50 U of IFN-γ per ml, substantial inhibition of T. gondii replication occurred after treatment with IFN-γ in both strains of mice (71% inhibition in BALB/c cells and 64% in CBA/Ca cells). These data suggest that stimulation of microglia with IFN alone results in inhibition of T. gondii replication via a pathway that is NO independent. To further determine the role of NO production in the inhibition of T. gondii replication and to confirm that IFN-γ-mediated inhibition of T. gondii replication was NO independent, cells were treated with cytokines in the presence or absence of the arginine analog NMMA and [3H]uracil incorporation by T. gondii was measured. Cells were treated sequentially with 500 μM NMMA and NO inducers, allowed to incubate for 24 h, and then infected with T. gondii and given [3H]uracil. After an additional 24-h incubation, both NO production and [3H]uracil incorporation were measured. Table 2 shows that addition of NMMA inhibited NO production after treatment with LPS plus IFN-γ or LPS plus IFN-γ plus TNF-α. When NMMA was added to microglia infected with T. gondii in the absence of inducers, it had no significant effect on T. gondii replication, demonstrating that NMMA by itself does not adversely affect T. gondii replication. When cells from both mouse strains were treated with IFN-γ in the presence of NMMA, the inhibition of T. gondii replication that had been previously observed was not reversed, confirming that inhibition of replication by IFN-γ was independent of NO production.

TABLE 2.

Nitric oxide production and T. gondii proliferation in the presence or absence of l-NMMA in microglia from BALB/c and CBA/Ca micea

| Mouse strain and l-NMMA treatment | Medium

|

IFN-γ

|

LPS + IFN-γ

|

LPS+ IFN-γ + TNF-α

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO productionb | [3H]uracil incorporationc | NO production | [3H]uracil incorporation | NO production | [3H]uracil incorporation | NO production | [3H]uracil incorporation | |

| BALB/c | ||||||||

| −NMMA | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 24,360 ± 7,687 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 4,406 ± 313 | 12.6 ± 0.7 | 1,245 ± 317 | 13.4 ± 0.4 | 835 ± 165 |

| +500 μM NMMA | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 20,265 ± 7,663 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 3,331 ± 430** | 3.8 ± 0.4** | 5,315 ± 608** | 3.7 ± 0.2** | 2,260 ± 289** |

| CBA/Ca | ||||||||

| −NMMA | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 10,492 ± 1,231 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 3,523 ± 721 | 7.0 ± 1.0 | 1,182 ± 245 | 7.7 ± 1.1 | 623 ± 127 |

| +500 μM NMMA | 0.9 ± 0.2* | 10,156 ± 2,233 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 2,798 ± 692 | 3.2 ± 0.3** | 4,958 ± 412** | 3.3 ± 0.3** | 2,519 ± 278** |

Cells were treated for 24 h with 50 U of IFN-γ per ml, 100 ng of TNF-α per ml, and/or 10 ng of LPS per ml or combinations of these inducers. T. gondii and [3H]uracil were added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 h before measurement of NO production and [3H]uracil incorporation. The experiment shown is a representative of five performed. **, statistically significant (P < 0.01) by Student's t test compared with treatment in the absence of NMMA. *, statistically significant (P < 0.05) by Student's t test compared with treatment in the absence of NMMA.

NO (micromolar concentration) production in the presence of T. gondii, measured in duplicate for each of four replicate wells per treatment (mean ± standard deviation).

[3H]uracil (counts per minute) incorporation by T. gondii. [3H]uracil uptake was measured in four replicate wells per treatment (mean ± standard deviation).

When cells stimulated with LPS plus IFN-γ or LPS plus IFN-γ plus TNF-α were treated with 500 μM NMMA, [3H]uracil incorporation by T. gondii was significantly increased: fourfold when NMMA was administered in combination with LPS plus IFN-γ and three- to fourfold when it was administered in combination with LPS plus IFN-γ plus TNF-α. However, even with the highest concentrations of NMMA, [3H]uracil incorporation did not return to the levels seen when T. gondii was allowed to replicate in the absence of inducers. The fact that full recovery of T. gondii replication was not seen provides further evidence that an NO-independent mechanism is operating and that this mechanism is activated by the presence of IFN-γ.

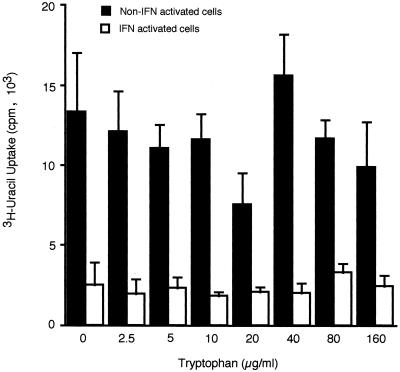

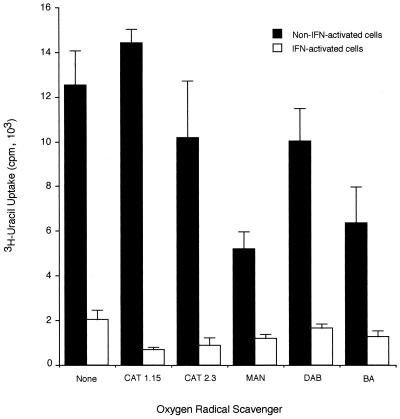

IFN-γ can induce macrophage-mediated killing of intracellular parasites by stimulating increases in the production of reactive oxygen metabolites (28, 30) or inhibiting T. gondii replication via induction of IDO and consequent degradation of tryptophan (29, 32). The possibility that T. gondii replication was inhibited in BALB/c microglia via either of these mechanisms was investigated. Data presented in Fig. 3 demonstrate that addition of increasing concentrations of tryptophan did not reverse the inhibitory effect of IFN-γ on T. gondii replication. A series of scavengers of reactive oxygen species were added to microglial cells stimulated with IFN-γ to determine whether the scavenger molecules blocked the inhibitory effect of IFN-γ on T. gondii replication. The addition of catalase, mannitol, DABCO, or benzoic acid did not block the inhibitory effects of IFN-γ (Fig. 4). These data suggest that the mechanism that contributes to the inhibition of T. gondii replication by IFN-γ does not involve degradation of l-tryptophan or generation of oxygen radicals.

FIG. 3.

Effect of l-tryptophan on IFN-γ-induced inhibition of T. gondii replication in BALB/c microglia. Microglia were stimulated with 50 U of IFN-γ per ml in the presence of increasing concentrations of l-tryptophan for 24 h before being infected with 105 PLK strain tachyzoites per well. [3H]uracil was added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 h before [3H]uracil incorporation by T. gondii was measured. Results are expressed as means and standard deviations of quadruplicate samples in one of two replicate experiments.

FIG. 4.

Effect of oxygen scavengers on IFN-γ-induced inhibition of T. gondii replication in BALB/c microglia. Microglia were stimulated for 24 h with 50 U of IFN-γ per ml in the presence of the following oxygen radical scavengers at the given concentrations: catalase (CAT) at 1.15 and 2.3 mg/ml, d-mannitol (MAN) at 50 mM, DABCO (DAB) at 0.5 mM, and benzoic acid (BA) at 5 mM; they were then infected with 105 PLK strain tachyzoites per well. [3H]uracil was added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 h before [3H]uracil incorporation by T. gondii was measured. Results are expressed as means and standard deviations of quadruplicate samples in one of two replicate experiments.

DISCUSSION

This work demonstrates both NO-dependent and NO-independent mechanisms of inhibition of T. gondii replication in primary microglial cell cultures from newborn BALB/c and CBA/Ca mice. In our studies, microglia from BALB/c mice produced significantly more NO after stimulation with LPS or with IFN-γ plus TNF-α than did microglia from CBA/Ca mice and they inhibited replication of T. gondii to a greater extent. These studies also indicate that an IFN-γ-dependent, NO-independent mechanism exists for inhibition of T. gondii replication in vitro, and from these initial observations, it appears that inhibition of T. gondii replication by this mechanism may not differ significantly between the two mouse strains.

The observed differences in NO production do not appear to be due to trivial differences in treatment of cells from the two strains, since all procedures for dissections, growth of the cells, and assays were performed at the same times and with the same reagents for both strains. Microscopic examination of cells from the two strains did not suggest that major differences in growth rates or viability contributed to differences in NO production or uracil incorporation by T. gondii. When microglia from the two strains were tested for their ability to inhibit T. gondii replication in the presence of IFN-γ only, no NO was detected; however, T. gondii replication was inhibited to a similar extent in cultures from both strains.

In the present study, we observed that IFN-γ alone did not induce iNOS expression, even when the concentration was increased to 500 U/ml. Xie et al. (45) and Lowenstein et al. (24) have investigated the molecular basis of the inability of IFN-γ to induce the full transcriptional response of the iNOS promoter. The murine iNOS promoter from RAW 264.7 cells, of BALB/c origin, has been sequenced, and various regulatory elements in the region have been identified; they include several copies of IFN-γ response elements, NF-κB and AP-1 sites, and TNF-α response elements, as well as other elements. Lowenstein et al. (24), using a luciferase reporter assay, observed that maximal expression of iNOS depended on two discrete regulatory regions upstream of the TATA box: region I (positions −48 to −209), which contained LPS response elements, and region II (positions −913 to −1029), which alone did not increase the expression of reporter genes but together with region I caused an additional 10-fold increase in reporter gene expression in the presence of IFN-γ. Region II was responsible for IFN-γ-mediated regulation of LPS-induced iNOS, while both regions I and II were necessary for LPS-activated expression. Since the binding of IFN-γ induced transcription factors to region II of the iNOS promoter is not sufficient to activate gene expression, one would not expect NO production after cells are stimulated in vitro with IFN-γ alone.

Microglia from BALB/c mice were examined to determine the mechanism whereby treatment with IFN-γ inhibits T. gondii replication. The inhibition was not due to either degradation of tryptophan or production of oxygen radicals. Tryptophan degradation resulting from IFN-γ induction of IDO, a tryptophan-decyclizing enzyme, can be overcome by supplementing the medium with increasing amounts of tryptophan. Addition of up to 160 μg of tryptophan per ml did not reverse the inhibitory effect of IFN-γ on [3H]uracil incorporation by T. gondii in the microglial cultures.

T. gondii is susceptible to toxicity mediated by reactive oxygen intermediates in certain in vitro macrophage cultures. The use of catalase to break down hydrogen peroxide and of mannitol, benzoic acid, and the superoxide anion scavenger (DABCO) to scavenge hydroxyl free radicals and reactive oxygen species had no effect on the IFN-γ-mediated inhibition of T. gondii replication in these microglial cell cultures. Thus, we concluded that in this system the inhibitory effect of IFN-γ on T. gondii replication was not due to the activity of IDO or oxygen free radicals.

Pfefferkorn and Guyre (34) have shown that 128 U of IFN-γ per ml has no direct effect on T. gondii viability in vitro. Leenen et al. (23) showed that IFN-γ plus TNF-α stimulated a macrophage precursor line to kill Listeria monocytogenes in a NO-independent manner and speculated that the mechanism involved might be phagocytosis of the parasite by the activated macrophage. Microglia, as well as activated macrophages, have an intrinsic phagocytosis-mediated defense against T. gondii (31), as well as a NO-dependent pathway. Recently, Halonen et al. (15, 16) have observed that the combination of IFN-γ with IL-1 or IL-6 significantly inhibited T. gondii growth in cultured astrocytes and showed that the mechanism was independent of NO, tryptophan starvation, oxygen radical production, or iron deprivation. To date, the mechanism of this in vitro IFN-γ-dependent inhibition of T. gondii replication is unknown. Our observation that a similar mechanism operates in microglial cells supports the importance of this mechanism as a protection against T. gondii replication in the CNS.

The relative importance of the NO-dependent and NO-independent mechanisms of inhibiting T. gondii replication during CNS infection in the CBA/Ca and the BALB/c strains is difficult to assess. Recently, a significant amount of information has become available on possible roles of NO-dependent mechanisms of protection in TE-susceptible and -resistant mouse strains.

Mice with a targeted disruption of the iNOS gene on a 129SvEv × C57BL/6 background have been used to demonstrate that while NO is not required for host control of acute infection, it appears to be critical for control of T. gondii replication in the CNS (37). At 3 to 4 weeks after infection, the iNOS knockout mice succumbed to T. gondii infection, with parasite proliferation and pathologic manifestations in the CNS. NO production, however, is not the only mechanism of resistance in the CNS. Yap and Sher (48), using iNOS-deficient mice on a C57BL/6 background, made bone marrow chimeras to dissect the roles of hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells in control of T. gondii infection in the CNS. These studies demonstrated that NO is required for hematopoietic cell-derived (microglial) effector cell activity against T. gondii but is not required for nonhematopoietic cell-derived activity. This observation corroborates that of Halonen and Weiss (17) that nonhematopoietic astrocytes inhibit T. gondii replication via an NO-independent mechanism.

The role of NO in resistance to T. gondii in the BALB/c (TE-resistant) mouse appears to be very different from that in the C57BL/6 (TE-susceptible) mouse. Recently, Schluter et al. (38) demonstrated that treatment of BALB/c mice with the selective iNOS inhibitor l-N6-iminoethyl-lysine (L-NIL) did not result in reactivation of a latent infection in BALB/c mice although it exacerbated T. gondii infection in the CNS of C57BL/6 mice. Thus, NO does not appear to play a role in maintaining a latent infection in BALB/c mice. Further experiments by Suzuki et al. (42), using IFN-γ-deficient mice on a BALB/c background, demonstrated that in the absence of IFN-γ, mRNAs for TNF-α and NO are still detected in the brains of T. gondii-infected animals; however, this is insufficient to control the infection in the absence of IFN-γ.

Thus, the recent literature argues against a significant role for NO in the control of a latent infection in the CNS of BALB/c mice, but it supports the requirement for a role of NO in T. gondii control in strains where a chronic persistent infection occurs in the CNS. In this context, CBA/Ca mice, like C57BL/6 mice, experience a persistent chronic infection in the CNS after T. gondii infection (26). The fact that CBA/Ca mice produce less NO than do strains that contain the infection and allow the development of latency may explain why T. gondii does not establish a latent infection in the CNS of CBA/Ca mice. In keeping with this analysis, Bohne et al. (2) have suggested that the increased NO production by BALB/c microglia may serve to promote the conversion of tachyzoites to bradyzoites observed in this strain.

In conclusion, our work demonstrates that both NO-dependent and NO-independent mechanisms contribute to the inhibition of T. gondii replication in microglial cultures from BALB/c and CBA/Ca mice. The mechanism of the NO-independent inhibition remains to be elucidated; however, this mechanism appears to be equally functional in both the TE-susceptible CBA/Ca mouse and the TE-resistant BALB/c mouse. Microglia from CBA/Ca mice show decreased production of NO and inhibition of T. gondii replication after stimulation with LPS or IFN-γ plus TNF-α compared to microglia from BALB/c mice. To date, this is the first observation of in vitro differences in NO production between microglia from TE-susceptible and TE-resistant mice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. Hokama for technical assistance, S. Miller and K. Laderoute for critically reading the manuscript, M. Saunders for editorial support, and M. Williamson for secretarial assistance.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI31544 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams L B, Hibbs J B, Jr, Taintor R R, Krahenbuhl J L. Microbiostatic effect of murine-activated macrophages for Toxoplasma gondii. Role of synthesis of inorganic nitrogen oxides from l-arginine. J Immunol. 1990;144:2725–2729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohne W, Heesemann J, Gross U. Reduced replication of Toxoplasma gondii is necessary for induction of bradyzoite-specific antigens: a possible role for nitric oxide in triggering stage conversion. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1761–1767. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1761-1767.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown C, Hunter C A, Estes R G, Beckmann E, Forman J, David C, Remington J S, McLeod R. Definitive identification of a gene that confers resistance against Toxoplasma cyst burden and encephalitis. Immunology. 1995;85:419–428. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chao C C, Hu S, Close K, Choi C S, Molitor T W, Novick W J, Peterson P K. Cytokine release from microglia: differential inhibition by pentoxifylline and dexamethasone. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:847–853. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.4.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chao C C, Hu S, Molitor T W, Shaskan E G, Peterson P K. Activated microglia mediate neuronal cell injury via a nitric oxide mechanism. J Immunol. 1992;149:2736–2741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chao C C, Anderson W R, Hu S, Gekker G, Martella A, Peterson P K. Activated microglia inhibit multiplication of Toxoplasma gondii via a nitric oxide mechanism. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;67:178–183. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chao C C, Hu S, Gekker G, Novick W J, Jr, Remington J S, Peterson P K. Effects of cytokines on multiplication of T. gondii in microglial cells. J Immunol. 1993;150:3404–3410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deckert-Schluter M, Albrect S, Hof H, Wiestler O D, Schluter D. Dynamics of the intracerebral and splenic cytokine mRNA production in Toxoplasma gondii-resistant and -susceptible congenic strains of mice. Immunology. 1995;85:408–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding A H, Nathan C F, Stuehr D J. Release of reactive nitrogen intermediates and reactive oxygen intermediates from mouse peritoneal macrophages. Comparison of activating cytokines and evidence for independent production. J Immunol. 1988;141:2407–2412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frenkel J K. Adoptive immunity to intracellular infection. J Immunol. 1967;98:1309–1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gazzinelli R T, Hakim F T, Hieny S, Shearer G M, Sher A. Synergistic role of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in IFN-γ production and protective immunity induced by an attenuated Toxoplasma gondii vaccine. J Immunol. 1991;146:286–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gazzinelli R, Xu Y, Hieny S, Cheever A, Sher A. Simultaneous depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes is required to reactivate chronic infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 1992;149:175–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gifford G E, Lohmann-Matthes M L. Gamma interferon priming of mouse and human macrophages for induction of tumor necrosis factor production by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. JNCI. 1987;78:121–124. doi: 10.1093/jnci/78.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant I H, Gold J W, Rosenblum M, Niedzwiecki D, Armstrong D. Toxoplasma gondii serology in HIV-infected patients: the development of central nervous system toxoplasmosis in AIDS. AIDS. 1990;4:519–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halonen S K, Lyman W D, Chiu F C. Growth and development of Toxoplasma gondii in human neurons and astrocytes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55:1150–1156. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199611000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halonen S K, Chiu F C, Weiss L M. Effects of cytokines on growth of Toxoplasma gondii in murine astrocytes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4989–4993. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4989-4993.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halonen S K, Weiss L M. Investigation into the mechanism of gamma interferon-mediated inhibition of Toxoplasma gondii in murine astrocytes. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3426–3430. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3426-3430.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter C A, Litton M J, Remington J S, Abrams J S. Immunocytochemical detection of cytokines in the lymph nodes and brains of mice resistant or susceptible to toxoplasmic encephalitis. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:939–945. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.James S. Role of nitric oxide in parasitic infections. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:533–547. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.533-547.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jun C D, Kim S H, Soh C T, Kang S S, Chung H T. Nitric oxide mediates the toxoplasmastatic activity of murine microglial cells in vitro. Immunol Investig. 1993;22:487–501. doi: 10.3109/08820139309084178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koerner T J, Adams D O, Hamilton T A. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) expression: interferon-γ enhances the accumulation of mRNA for TNF induced by lipopolysaccharide in murine peritoneal macrophages. Cell Immunol. 1987;109:437–443. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(87)90326-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langermans J A, Van der Hulst M E B, Nibbering P H, Hiemstra P S, Fransen L, Van Furth R. IFN-γ-induced l-arginine-dependent toxoplasmastatic activity in murine peritoneal macrophages is mediated by endogenous tumor necrosis factor-α. J Immunol. 1992;148:568–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leenen P J M, Canono B P, Drevets D A, Voerman J S A, Campbell P A. TNF-α and IFN-γ stimulate a macrophage precursor cell line to kill Listeria monocytogenes in a nitric oxide-independent manner. J Immunol. 1994;153:5141–5147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowenstein C J, Alley E W, Raval P, Snowman A M, Synder S H, Russell S W, Murphy W J. Macrophage nitric oxide synthase gene: two upstream regions mediate induction by interferon-γ and lipopolysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9730–9734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luft B J, Remington J S. AIDS Commentary. Toxoplasmic encephalitis. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:1–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luft B J, Hafner R, Korzun A H, Leport C, Antoniskis D, Bosler E M, Bourland III D D, Uttamchandani R, Fuhrer J, Jacobsen J, et al. Toxoplasmic encephalitis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Members of the ACTB 077p/ANRS 009 study team. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:995–1000. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mack D G, McLeod R. New micromethod to study the effect of antimicrobial agents on Toxoplasma gondii: comparison of sulfadoxine and sulfadiazine individually and in combination with pyrimethamine and study of clindamycin, metronidazole, and cyclosporin A. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;26:26–30. doi: 10.1128/aac.26.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray H W, Rubin B Y, Carriero S M, Harris A M, Jaffee E A. Human mononuclear phagocyte antiprotozoal mechanisms: oxygen-dependent versus oxygen-independent activity against intracellular Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 1985;134:1982–1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murray H W, Szuro-Sudol A, Wellner D, Oca M J, Granger A M, Libby D M, Rothermel D D, Rubin B Y. Role of tryptophan degradation in respiratory burst-independent anti-microbial activity of gamma interferon-stimulated human macrophages. Infect Immun. 1989;57:845–849. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.3.845-849.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nathan D F, Murray H W, Wiebe M E, Rubin B Y. Identification of interferon-γ as the lymphokine that activates human macrophage oxidative metabolism and antimicrobial activity. J Exp Med. 1983;158:670–689. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.3.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peterson P K, Gekker G, Hu S, Chao C C. Intracellular survival and multiplication of T. gondii in astrocytes. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1472–1478. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.6.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfefferkorn E R. Interferon gamma blocks the growth of T. gondii in human fibroblasts by inducing the host cells to degrade tryptophan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:908–912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfefferkorn E R. Cell biology of Toxoplasma gondii. In: Wyler D J, editor. Modern parasite biology: cellular, immunological and molecular aspects. W. H. New York, N.Y: Freeman & Co.; 1990. p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfefferkorn E R, Guyre P M. Inhibition of growth of Toxoplasma gondii in cultured fibroblasts by human recombinant gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 1984;44:211–216. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.2.211-216.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reis e Sousa C, Hieny S, Scharton-Kersten T, Jankovic D, Charest H, Germain R N, Sher A. In vivo microbiol stimulation induced rapid CD40 ligand-independent production of interleukin 12 by dendritic cells and their redistribution to T cell areas. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1819–1829. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.11.1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rose K, Goldberg M P, Choi D W. Cytotoxicity in murine cortical cell culture. In: Tyson C A, Frazer J M, editors. Methods in toxicology, part A. In vitro biological methods. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1993. p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scharton-Kersten T M, Yap G, Magram J, Sher A. Inducible nitric oxide is essential for host control of persistent but not acute infection with the intracellular pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1261–1273. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schluter D, Deckert-Schluter M, Lorenz E, Meyer T, Rollinghoff M, Bogdan C. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase exacerbates chronic cerebral toxoplasmosis in Toxoplasma gondii-susceptible C57BL/6 mice but does not reactivate the latent disease in T. gondii-resistant BALB/c mice. J Immunol. 1999;162:3512–3518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sher A, Oswald I P, Hieny S, Gazzinelli R T. Toxoplasma induces a T-independent IFN-γ response in natural killer cells that requires both adherent accessory cells and tumor necrosis factor-α. J Immunol. 1993;150:3982–3989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki Y, Orellana M A, Schreiber R D, Remington J S. Interferon-γ: the major mediator of resistance against Toxoplasma gondii. Science. 1988;240:516–518. doi: 10.1126/science.3128869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki Y, Conley F K, Remington J S. Importance of endogenous IFNγ for prevention of toxoplasmic encephalitis in mice. J Immunol. 1989;143:2045–2050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki Y, Kang H, Parmley S, Lim S, Park D. Induction of tumor necrosis factor-α and inducible nitric oxide synthase fails to prevent toxoplasmic encephalitis in the absence of interferon-γ in genetically resistant BALB/c mice. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:455–462. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00318-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong S-Y, Remington J S. Toxoplasmosis in AIDS. In: Phair J P, editor. Opportunistic complications of HIV. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Meniscus Health Care Communications; 1993. pp. 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woodman J P, Dimier I H, Bout D T. Human endothelial cells are activated by IFN-γ to inhibit Toxoplasma gondii replication. Inhibition is due to a different mechanism from that existing in mouse macrophages and human fibroblasts. J Immunol. 1991;147:2019–2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xie Q, Whisnant R, Nathan C. Promoter of the mouse gene encoding calcium-independent nitric oxide synthase confers inducibility by interferon-γ and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1779–1784. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiong J, Nishibori T, Ohya S, Tanabe Y, Mitsuyama M. Involvement of various combinations of endogenous inflammatory cytokines in Listeria monocytogenes-induced expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in mice. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1996;16:257–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yam L T, Li C Y, Crosby W H. Cytochemical identification of monocytes and granulocytes. Am J Clin Pathol. 1971;55:283–290. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/55.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yap G S, Sher A. Effector cells of both nonhemopoietic and hemopoietic origin are required for interferon (IFN)-γ- and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α-dependent host resistance to the intracellular pathogen, Toxoplasma gondii. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1083–1091. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yap G S, Sher A. Cell-mediated immunity to Toxoplasma gondii: initiation, regulation and effector function. Immunobiology. 1999;201:240–247. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(99)80064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]