Abstract

The P2 porin protein is the most abundant protein in the outer membrane of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHI). Analysis of sequences of P2 from different strains reveals the presence of both heterogeneous and conserved surface-exposed loops of the P2 molecule among strains. The present study was undertaken to test the hypothesis that antibodies to a conserved surface-exposed loop are bactericidal for multiple strains of NTHI and could thus form the basis of vaccines to prevent infection due to NTHI. Polyclonal antiserum to a peptide corresponding to loop 6 was raised and was immunopurified over a loop 6 peptide column. Analysis of the antibodies to whole organisms and peptides corresponding to each of the eight loops of P2 by immunoassays revealed that the antibodies were highly specific for loop 6 of P2. The immunopurified antibodies bound to P2 of 14 of 15 strains in immunoblot assays. These antibodies to loop 6 demonstrated complement-mediated bactericidal killing of 8 of 15 strains. These results support the concept of using conserved regions of the P2 protein as a vaccine antigen.

Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHI) is a small, gram-negative bacillus which causes otitis media in children and lower respiratory infections in adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In both otitis media and COPD, patients routinely suffer recurrent episodes of disease (15, 21). Factors such as health care costs, pain and suffering, and lost work time underscore the need for a vaccine against NTHI (10, 14, 22).

The ability of NTHI to cause recurrent infections is in part attributable to antigenic variability in several surface-exposed loops of major outer membrane protein P2 (2, 5, 26). The P2 protein is a homotrimeric porin which constitutes approximately one-half of the total outer membrane protein of the organism. The loop 5 region is highly heterogeneous among strains and contains almost all of the epitopes to which an antibody response is mounted when animals are immunized with the whole organism (30). Adults with COPD make new antibodies to strain-specific epitopes on P2 following infection by NTHI (31). Thus, immunity against NTHI is most often strain specific, leaving the patient vulnerable to reinfection by other strains.

One approach to vaccine development for NTHI has been to study antigenically conserved outer membrane proteins as potential vaccine antigens. In view of the abundant expression of P2 on the bacterial surface, identification of a conserved region on the P2 molecule to which immune responses could be directed would be a significant step towards developing a vaccine against NTHI.

In this study, antibodies to a conserved loop of the P2 molecule of NTHI (loop 6) were raised and studied for their ability to recognize the P2 molecules of heterologous strains. Since bactericidal antibody is associated with protection from otitis media due to NTHI (8, 25), antibodies to loop 6 were also assessed for their ability to direct killing of heterologous strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The 15 strains of NTHI used in this study were recovered from the sputum of adults with chronic bronchitis in Buffalo, N.Y. The identities of strains were confirmed by growth requirements for hemin and NAD. Strains were cultured on chocolate agar at 35°C in 5% CO2. For bactericidal assays, bacteria were grown in brain heart infusion broth supplemented with 10 μg of hemin and 20 μg of NAD/ml at 35°C either in 5% CO2 or with vigorous shaking.

Immunization of animals.

A 20-mer multiple antigenic peptide (MAP) corresponding to the loop 6 sequence of the P2 molecule of NTHI strain 5657 was ordered from QCB (Hopkinton, Mass.). The sequence of the peptide was DSGYAKTKNYKDKHEKSYFV. A rabbit was immunized as follows: 50 μg of loop 6 MAP in complete Freund's adjuvant was administered subcutaneously on day 0, and 50 μg of loop 6 MAP in incomplete Freund's adjuvant was administered subcutaneously on days 14 and 28. Blood was obtained on day 35.

Comparison of P2 sequences.

The sequences of P2 from 15 strains of NTHI were obtained from GenBank (2, 5, 6, 26). The amino acid sequences in the loop 6 regions of these molecules were compared using the MacVector program.

SDS-PAGE.

Samples were solubilized in sample buffer and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 12% gels as previously described (18). Gels were stained with Coomassie blue or transferred to nitrocellulose for immunoblot assays as previously described (17, 20).

Immunoblot assays.

Nitrocellulose membranes were blocked in 3% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 0.01 M Tris, 0.15 M NaCl [pH 7.4]) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed three times in TBS and incubated with a 1:500 dilution of affinity-purified anti-loop 6 antibody in TBS at 4°C overnight. Membranes were washed again as described above and incubated with a 1:3,000 dilution of peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Kirkegaard and Perry, Gaithersburg, Md.) in TBS. The membranes were washed once again, and the bands were visualized by a brief incubation in horseradish peroxidase color development solution containing 0.15% H2O2 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.).

Recombinant fusion proteins.

Fusion proteins corresponding to the exposed loops of the P2 molecule of NTHI 1479 were grown and purified from previously constructed clones containing P2 gene fragments in the pGEX-2T vector (13, 30).

Affinity purification of serum.

A loop 6 affinity column with a bed volume of 1 ml was constructed using CNBr-Sepharose (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) and loop 6 MAP according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, ∼3 mg of loop 6 MAP dissolved in 1.7 ml of coupling buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 8.3) was incubated with 1 ml of CNBr-Sepharose (0.3 g of freeze-dried beads reconstituted in 1 mM HCl) for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. The beads were washed in 8 ml of coupling buffer and blocked in 0.2 M glycine, pH 8.0, for 2 h at room temperature. The CNBr-Sepharose was subjected to three cycles of low-pH washes (0.1 M CH3COOH, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 4.0) followed by high-pH washes (0.2 M glycine, pH 8.0). Finally the beads were placed in a column and washed with 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). A blank column was constructed using the same method in the absence of MAP 6 peptide.

A 0.5-ml aliquot of rabbit anti-loop 6 serum was applied to the loop 6 affinity column, and the flowthrough was collected. Following a 15-ml PBS wash, antibodies were eluted from the column with 2 ml of 0.1 M glycine, pH 2.5. Eluate was collected in a 15-ml conical tube containing 160 μl of 1 M Tris, pH 9.0, and the column was washed again with 5 ml of PBS. The flowthrough was again applied to the column and subjected to this procedure two more times. The eluates were pooled. The pooled eluates were exchanged into PBS and concentrated to 0.5 ml using 10,000-Da-exclusion Centricon filters (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). To control for nonspecific binding of antibody to resin, this same procedure was performed using a blank column.

Bactericidal assays.

Bacteria grown to mid-logarithmic phase in broth were diluted to 5 × 104 CFU/ml in Gey's balanced salt solution containing 10% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin. Reaction mixtures consisted of 25 μl of diluted bacteria, 22 μl of complement, an appropriate volume of normal human serum (as a positive control) or anti-loop 6 antibody, and 2.5% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum in Gey's balanced salt solution to bring the final volume to 250 μl. Normal human serum depleted of immunoglobulin G by adsorption over a protein G column was used as a complement source. Normal human serum was used as an antibody source in positive control assays. For this purpose, the serum was heat inactivated at 56°C for 30 min. The reaction mixtures were incubated at either 37°C with vigorous shaking or at 35°C in 5% CO2. Duplicate 25-μl aliquots from each reaction mixture were plated on chocolate agar at 0 and 60 min. In some assays, additional samples were taken at 30 min. The plates were incubated at 35°C overnight, and the colonies were counted the next day.

Primer sequences.

Oligonucleotides used for the amplification and sequencing of the loop 6-encoding region of the P2 gene were purchased from Sigma-Genosys (The Woodlands, Tex.). The forward and reverse primers used in amplification, P2F1 (5′ ACGCGGATCCTGCTGTTGTTTATAACAACG) and P2R1 (5′ ATCAGGATCCTTAGAAGTAAACGCGTAAACCTAC), are complementary to regions upstream and downstream of the P2 gene, respectively. Primers used for sequencing were P2R1 and two oligonucleotides complementary to sequences within the P2 gene, P2F2 (5′ GGTGAAGTAAAACTTGGTC) and P2R2 (5′ CAATAGACATTAGTATCTTCC).

Amplification of the loop 6-encoding region of the P2 gene.

Genomic DNA was isolated from strains of NTHI. Template DNA was prepared from overnight cultures of NTHI grown on chocolate agar using the Wizard genomic DNA prep kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, Wis.). The genomic DNA preparations were diluted 1:100, and 1 μl was added to reaction mixtures containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.001% (wt/vol) gelatin, 200 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dGTP, dATP, dTTP, and dCTP), 500 ng of each primer (P2F1 and P2R1), and 1.25 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase in a 25-μl volume. Template DNA was melted at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 amplification cycles of 30s at 94°C, 30s at 58°C, and 90 at 72°C. The amplicons were resolved on a 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. Bands were excised and purified with the Gene Clean kit (BIO 101, Vista, Calif.). The products were diluted to a concentration of 10 to 20 ng/μl for sequencing.

DNA sequencing.

The DNA sequencing of the PCR products was carried out by the Roswell Park Cancer Institute Biopolymer Facility (Buffalo, N.Y.) using primers P2F2, P2R1, and P2R2.

RESULTS

Specificity of immunopurified antibodies to loop 6.

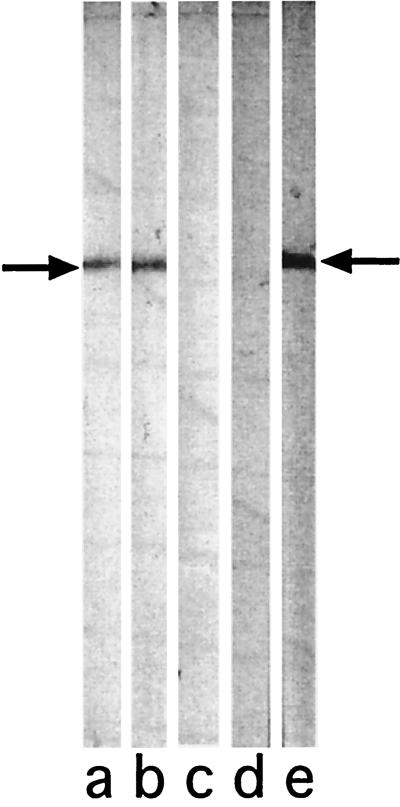

To assess the specificity of antibodies immunopurified from the loop 6 affinity column, a whole-cell preparation of NTHI 5657 (the homologous strain) was subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose. Strips cut from the blotted nitrocellulose membrane were probed with whole rabbit anti-loop 6 serum (Fig. 1, lane a), fall-through from a blank column (lane b), eluate from a blank column (lane c), fall-through from a loop 6 affinity column (lane d), and eluate from a loop 6 affinity column (lane e). A single band with the mobility of the P2 molecule (∼42 kDa) is seen in the strips probed with whole rabbit anti-loop 6 serum and loop 6 affinity column eluate. These data indicate that antibodies eluted from the loop 6 affinity column are specific for P2 of NTHI 5657. The results from the blank column exclude the possibility that antibodies in loop 6 antiserum interact nonspecifically with CNBr-Sepharose beads.

FIG. 1.

Immunoblot assay with whole-bacterial-cell lysate of NTHI strain 5657. The lysate was probed with fractions from aliquots of rabbit anti-loop 6 antiserum subjected to affinity chromatography with a loop 6 peptide column and a control blank column. Lanes: a, whole rabbit anti-loop 6 antiserum; b, fall-through from control blank column; c, sham eluate from blank column; d, fall-through from loop 6 affinity column; e, eluate from loop 6 affinity column. All serum fractions were diluted 1:500. Arrow, location of P2.

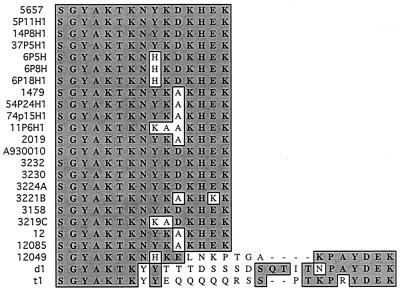

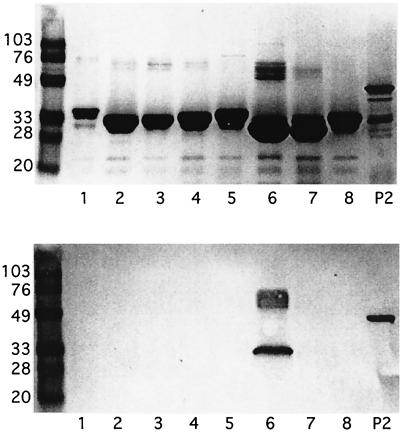

To further evaluate the specificity of the antibodies recovered in the loop 6 affinity column eluate, glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins corresponding to the eight loops of the P2 protein of NTHI 1479 were expressed and purified using the pGEX-2T vector as previously described (13). Loop 6 of NTHI 1479 differs from loop 6 of NTHI 5657 at a single residue (D to A at position 273; see Fig. 4). When subjected to immunoblot analysis, immunopurified antibodies to loop 6 MAP bound exclusively to the GST-loop 6 protein and purified P2 (Fig. 2). These data indicate that antibodies immunopurified from the loop 6 affinity column are specific for loop 6 of the P2 molecule.

FIG. 4.

Amino acid sequences of loop 6 regions of P2 of 24 strains of NTHI.

FIG. 2.

(Top) Coomassie blue-stained SDS gel. (Bottom) Immunoblot assay with immunopurified anti-loop 6 peptide antiserum (1:500 dilution). Lanes 1 through 8 (both panels), purified GST fusion proteins corresponding to the eight loops of P2 of strain 1479; lanes P2, purified P2 with some proteolytic degradation. Molecular mass standards (kilodaltons) are on the left. The upper bands in lanes 6 likely represent dimerization of the fusion protein.

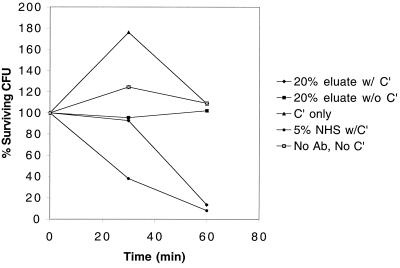

Bactericidal activity of anti-loop 6 antibodies for NTHI 5657.

To determine if immunopurified anti-loop 6 antibodies are bactericidal against NTHI, bactericidal assays were performed using NTHI 5657. Reaction mixtures containing 20% anti-loop 6 antibodies or 5% normal human serum exhibited significant killing in the presence of complement at the 60-min time point (Fig. 3). At the 30-min time point, there was consistently more killing in the normal human serum control than in the anti-loop 6 reaction mixture. Interestingly, these kinetics are similar to results with immunopurified antibodies to P6 used in bactericidal assays (19). No bactericidal activity was apparent in a control reaction mixture in which both complement and the anti-loop 6 antibody were omitted. Other controls included reaction mixtures containing complement without anti-loop 6 antibody and anti-loop 6 antibody without complement, both of which consistently showed no killing (Fig. 3). These results demonstrate that immunopurified antibodies raised against peptides corresponding to the amino acid sequence of loop 6 of the P2 protein of NTHI strain 5657 are bactericidal against strain 5657.

FIG. 3.

Results of bactericidal assay with NTHI strain 5657. Legend: 20% eluate w/C′, immunopurified loop 6 antibodies comprised 20% of the bactericidal assay mixture, and complement was present in the reaction mixture; 20% eluate w/o C′, same as above except no complement (negative control); C′ only, complement was present in the reaction mixture in the absence of antibody; 5% NHS w/C′, normal human serum comprised 5% of the bactericidal assay mixture, and complement was present in the reaction mixture (positive control); no ab, no C′, bactericidal reaction mixture consisted of bacteria and buffer alone (negative control).

Sequence homology in the loop 6 region of P2.

The amino acid sequences of loop 6 from 11 of the strains used in this study and 15 strains of NTHI found in GenBank were compared using the Mac Vector program. The 24 sequences are 87.3% identical on average to the loop 6 sequence of NTHI 5657 (Fig. 4). When the 24 strains were grouped geographically, it was found that the 19 strains isolated in the United States are 94.8% identical to NTHI 5657 in the loop 6 region, while the 5 strains isolated outside the United States are 57.4% identical to NTHI 5657 in the loop 6 region.

Reactivities of antibodies to loop 6 with heterologous strains.

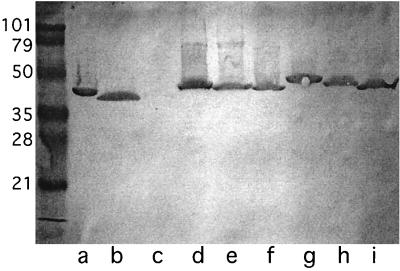

To determine the strain specificity of antibodies to loop 6 of NTHI 5657, whole-cell preparations of 15 clinical isolates were subjected to immunoblot assays. Figure 5 shows the results with nine strains. The immunopurified loop 6 antibodies bound to a band corresponding to P2 in 14 of the 15 clinical isolates of NTHI. These data indicate that antibodies to loop 6 of NTHI 5657 bind to P2 of multiple strains of NTHI.

FIG. 5.

Immunoblot assay with immunopurified rabbit anti-loop 6 antiserum (1:500 dilution). Lanes contain whole-bacterial-cell lysates of the following strains of NTHI: 5657(a), 6P18H1(b), 11P6H1(c), 5P11H1(d), 56P34H1(e), 70P11H1(f), 1479(g), 74P15H1(h), and 13P24H1 (i). Molecular mass standards (kilodaltons) are on the left.

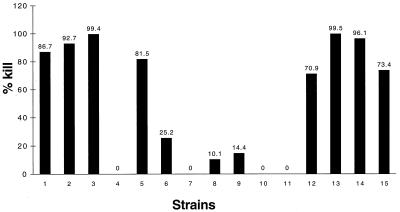

In order to test the hypothesis that immunopurified antibodies against loop 6 of P2 are bactericidal against multiple strains, bactericidal assays with the 15 clinical isolates used in the immunoblot assay were performed. Immunopurified antibodies to loop 6 of P2 of NTHI 5657 showed >50% kill against 8 of the 15 strains tested (Fig. 6). Not surprisingly, no killing of the strain which was nonreactive in the immunoblot (strain 11P6H; Fig. 5, lane c) was observed. Sequence, bactericidal, and immunoblot data are summarized in Table 1. Interestingly, sequence differences are restricted to a small region corresponding to amino acids 263 to 265 of the homologous strain (see Discussion). Controls included reaction mixtures in which complement, anti-loop 6 antibody, or both complement and anti-loop 6 antibody were omitted. No killing was observed in any of these controls.

FIG. 6.

Results of bactericidal assays with immunopurified anti-loop 6 antibodies for 15 clinical isolates of NTHI (percentages of killing at 60 min). Strains of NTHI are as follows: 1, 5657; 2, 1479; 3, 5P11H1; 4, 13P24H1; 5, 3P16H1; 6, 6P18H1; 7, 11P6H1; 8, 56P34H1; 9, 74P15H1; 10, 70P11H1; 11, 54P24H1; 12, 6P5H; 13, 6P8H; 14, 14P8H1; 15, 37P5H1.

TABLE 1.

Summary of loop 6 amino acid sequences and results of immunoblot and bactericidal assays of clinical isolates of NTHI

| Strain | Loop 6 sequencea | Results of indicated assay

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Bactericidal | Immunoblot | ||

| 5657 | SGYAKTKNYKDKHEK | + | + |

| 5P11H1 | SGTAKTKNYKDKHEK | + | + |

| 14P8H1 | SGYAKTKNYKDKHEK | + | + |

| 37P5H1 | SGYAKTKNYKDKHEK | + | + |

| 6P5H | SGYAKTKNHKDKHEK | + | + |

| 6P8H | SGYAKTKNHKDKHEK | + | + |

| 6P18H1 | SGYAKTKNHKDKHEK | − | + |

| 1479 | SGYAKTKNYKAKHEK | + | + |

| 54P24H1 | SGYAKTKNYKAKHEK | − | + |

| 75P15H1 | SGYAKTKNYKAKHEK | − | + |

| 11P6H1 | SGYAKTKNKAAKHEK | − | − |

Amino acids 263 to 265 are in boldface.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have demonstrated that antibodies from rabbits vaccinated with loop 6 MAP can be recovered intact by affinity chromatography. The specificity of these antibodies for loop 6 of the P2 molecule was established by probing immunoblots of NTHI 5657 whole-organism lysate and GST fusion proteins corresponding to the loops of the P2 molecule. Comparison of the loop 6 sequences from the P2 molecules of 24 strains of NTHI revealed an average identity of 87.3%, with higher identity in geographically related strains. Immunoblot analysis of whole-organism lysates of 15 clinical isolates revealed that the anti-loop 6 antibody recognized P2 in 14 of the 15 isolates. In bactericidal assays, the immunopurified antibody was bactericidal against the homologous isolate, as well as 7 of 14 heterologous clinical isolates.

Comparison of sequence, bactericidal, and immunoblot data reveals that amino acids 263 to 265 (Tyr-Lys-Asp) of strain 5657 are important in the recognition of the molecule by antibodies in immunoblot and bactericidal assays. The sequence of loop 6 of strain 11P6H1 differs exclusively in this region (Lys-Ala-Ala), accounting for negative bactericidal and immunoblot assays with anti-loop 6 antibodies. On the other hand, strains whose loop 6 sequence was identical to that of strain 5657 all bound antibodies in both immunoblot and bactericidal assays (Table 1). Table 1 shows strains with two sequences in which one of the three amino acids is different (His-Lys-Asp and Tyr-Lys-Ala). Anti-loop 6 antibodies bind these strains in immunoblot assays but show variable results in bactericidal assays. For example, strains 6P8H and 6P18H1 have identical loop 6 sequences and are both reactive in an immunoblot assay (Table 1). In spite of identical sequences, 6P8H is sensitive to bactericidal antibodies while 6P18H1 resists bactericidal killing. Based on the results summarized in Table 1, we conclude that two different mechanisms account for differences in the susceptibilities of strains to killing by anti-loop 6 antibodies. One mechanism is differences in the sequences of amino acids 263 to 265 of some strains (e.g., 5657 and 11P6H1). However, since strains with identical amino acid sequences in this region show differences in susceptibility to killing (e.g., 1479 and 54P24H1), other mechanisms must be operative as well. We speculate that differences in surface structures adjacent to P2 among NTHI strains affect the availability of epitopes on loop 6 to antibodies or possibly affect the ability of bound antibodies to fix complement.

Two attributes of the P2 protein of NTHI make antigenically conserved regions of this molecule attractive as vaccine antigens. First, P2 is abundantly expressed on the bacterial surface, comprising approximately one-half of the total outer membrane protein of the organism. Immunoelectron microscopy indicates that a panel of monoclonal antibodies directed against surface-exposed regions of the P2 molecule recognize abundantly expressed epitopes (12). These same monoclonal antibodies were highly bactericidal against the homologous strain in the presence of complement. Second, P2 is the only known porin expressed by NTHI and P2-deficient mutants exhibit slow growth (4). Thus, the immune response would target abundant epitopes on a molecule whose expression is not likely to be down regulated.

Two observations concerning the P2 molecule of NTHI cast doubt on the suitability of conserved regions of this molecule as vaccine antigens. Work by van Alphen and colleagues has demonstrated that regions of the P2 gene encoding surface-exposed loops undergo point mutations under immune selective pressure (6, 7, 11, 28). This observation raises the possibility that point mutations could occur in conserved loops targeted as vaccine antigens and render a vaccine useless. However, these point mutations were observed in two patients with COPD persistently infected with a single strain of NTHI over the course of 5 and 6 months. Similar results were observed in strains maintained in subcutaneous cages in rabbits for 15 months (29). Recent work involving a prospective study of COPD has demonstrated that active turnover of strains of NTHI occurs in adults with COPD (23; our unpublished observations). Furthermore, Faden et al. (9) showed that the mean duration of colonization by a single strain of NTHI in the nasopharynges of children is 2 months. These studies suggest that persistence of a strain of NTHI in the respiratory tract may be the exception rather than the rule. Since point mutations are a phenomenon associated with persistent colonization, it remains to be determined how commonly point mutations in the P2 molecule occur as a mechanism to evade the human immune response.

Another potential drawback to using conserved regions of the P2 molecule as vaccine antigens was raised by the work of Smith-Vaughn et al. (27), who demonstrated horizontal transfer of P2 genes in four Aboriginal infants persistently colonized with multiple strains of NTHI. The children of this community are colonized by NTHI by the age of 3 weeks and have otitis media by the age of 6 weeks, and 50% have perforated ear drums by the age of 6 months (16). Each child carries an average of four strains of NTHI at a time. It is possible that horizontal transfer of a P2 gene encoding P2 with highly heterogeneous surface-exposed regions would function as a mechanism to evade a protective immune response. However, the chronic and severe nature of the disease in this select population may be unique. Similar studies of infants and children in Buffalo, N.Y., have demonstrated that children are colonized with a single strain of NTHI at a time (3) and are colonized for shorter periods of time (9). Studies from Sweden show colonization rates which are similar to those from the Buffalo study (1, 24). Future studies are needed to address the question of whether horizontal transfer of the P2 gene is an important mechanism of immune system evasion.

Although loop 6 generally shows sequence conservation among strains, some isolates have loop 6 sequences that are remarkably different. For example, strains 12049 (a blood isolate from a child in Pakistan) and d1 and t1 (sputum isolates from persistently infected adults in The Netherlands) all show little similarity to other strains after the first seven residues of loop 6. However, it is difficult to link these differences to geography alone, since other isolates from the same areas had loop 6 sequences which were similar or identical to that of our homologous strain (e.g., strains 12085 and A930010). Indeed Duim et al. (5) have observed that in Dutch isolates, sequence heterogeneity in loop 6 is observed exclusively in strains which have persisted in the respiratory tracts of adults with chronic lung disease. Middle-ear isolates and isolates which colonize the adult respiratory tract for shorter periods demonstrate a high degree of sequence conservation among strains in the loop 6 region of P2 (5). A speculation that might explain this phenomenon is that a progenitor of these three strains somehow acquired an insertion in the loop 6 region. Increased loop size as the result of an insertion would make epitopes contained on the distal portion of the loop more accessible to the immune system, subjecting the organism to selective pressure. Point mutations which allow the organism to escape a specific immune response would be selected for, resulting in sequence heterogeneity. The portions of the loop more proximal to the outer membrane would be affected the least by selective pressure from the immune system and would remain unchanged. This hypothesis would account for the homology among the first seven and last six amino acids in loop 6 of these three strains.

In view of the association of bactericidal antibodies with protection from infection (8, 25), the results presented here support the feasibility of inducing a protective immune response to loop 6 of the P2 molecule of NTHI. Further work may focus on identifying other conserved, surface-exposed loops of P2. Utilizing more than one loop will contribute to overcoming potential antigenic heterogeneity and point mutations as mechanisms of immune system evasion since multiple mutations would be required to evade antibodies to multiple loops.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant AI19641 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aniansson G, Alm B, Andersson B, Larsson P, Nylen O, Peterson H, Rigner P, Svanborg M, Svanborg C. Nasopharyngeal colonization during the first year of life. J Infect Dis. 1992;165(Suppl. 1):S38–S42. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165-supplement_1-s38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell J, Grass S, Jeanteur D, Munson R S., Jr Diversity of the P2 protein among nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae isolates. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2639–2643. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2639-2643.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein J M, Dryja D, Yuskiw N, Murphy T F. Analysis of isolates recovered from multiple sites of the nasopharynx of children colonized by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:750–753. doi: 10.1007/BF01709258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cope L D, Pelzel S E, Latimer J L, Hansen E J. Characterization of a mutant of Haemophilus influenzae type b lacking the P2 major outer membrane protein. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3312–3318. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3312-3318.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duim B, Dankert J, Jansen H M, van Alphen L. Genetic analysis of the diversity in outer membrane protein P2 of non-encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae. Microb Pathog. 1993;14:451–462. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duim B, van Alphen L, Eijk P, Jansen H M, Dankert J. Antigenic drift of non-encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae major outer membrane protein P2 in patients with chronic bronchitis is caused by point mutations. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:1181–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duim B, Vogel L, Puijk W, Jansen H M, Meloen R H, Dankert J, van Alphen L. Fine mapping of outer membrane protein P2 antigenic sites which vary during persistent infection by Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4673–4679. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4673-4679.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faden H, Bernstein J, Brodsky L, Stanievich J, Krystoflk D, Shuff C, Hong J J, Ogra P L. Otitis media in children. I. The systemic immune response to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:999–1004. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.6.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faden H, Duffy L, Williams A, Krystofik D A, Wolf J Tonawanda/Williamsville Pediatrics. Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal colonization with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in the first 2 years of life. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:132–135. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foxwell A R, Kyd J M, Cripps A W. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: pathogenesis and prevention. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:294–308. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.294-308.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groeneveld K, van Alphen L, Voorter C, Eijk P P, Jansen H M, Zanen H C. Antigenic drift of Haemophilus influenzae in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3038–3044. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.10.3038-3044.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haase E M, Campagnari A A, Sarwar J, Shero M, Wirth M, Cumming C U, Murphy T F. Strain-specific and immunodominant surface epitopes of the P2 porin protein of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1278–1284. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1278-1284.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haase E M, Yi K, Morse G D, Murphy T F. Mapping of bactericidal epitopes on the P2 porin protein of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3712–3722. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3712-3722.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan B, Wandstrat T L, Cunningham J R. Overall cost in the treatment of otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:S9–S11. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199702001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein J O. Otitis media. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:823–833. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.5.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leach A J, Boswell J B, Asche V, Nienhuys T G, Mathews J D. Bacterial colonization of the nasopharynx predicts very early onset and persistence of otitis media in Australian Aboriginal infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:983–989. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199411000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy T F, Bartos L C. Purification and analysis with monoclonal antibodies of P2, the major outer membrane protein of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1084–1089. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1084-1089.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy T F, Bartos L C, Campagnari A A, Nelson M B, Apicella M A. Antigenic characterization of the P6 protein of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1986;54:774–779. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.3.774-779.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy T F, Bartos L C, Rice P A, Nelson M B, Dudas K C, Apicella M A. Identification of a 16,600-dalton outer membrane protein on nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae as a target for human serum bactericidal antibody. J Clin Investig. 1986;78:1020–1027. doi: 10.1172/JCI112656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy T F, Dudas K C, Mylotte J M, Apicella M A. A subtyping system for nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae based on outer-membrane proteins. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:838–846. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.5.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy T F, Sethi S. Bacterial infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:1067–1083. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.4.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy T F, Sethi S. A national strategy for research in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 1997;277:1596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy T F, Sethi S, Klingman K L, Brueggemann A B, Doern G V. Simultaneous respiratory tract colonization by multiple strains of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: implications for antibiotic therapy. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:404–409. doi: 10.1086/314870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samuelson A, Freijd A, Jonasson J, Lindberg A A. Turnover of nonencapsulated Haemophilus influenzae in the nasopharynges of otitis-prone children. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2027–2031. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2027-2031.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shurin P A, Pelton S I, Tazer I B, Kasper D L. Bactericidal antibody and susceptibility to otitis media caused by nontypeable strains of Haemophilus influenzae. J Pediatr. 1980;97:364–369. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(80)80182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sikkema D J, Murphy T F. Molecular analysis of the P2 porin protein of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1992;60:5204–5211. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5204-5211.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith-Vaughan H C, Sriprakash K S, Mathews J D, Kemp D J. Nonencapsulated Haemophilus influenzae in aboriginal infants with otitis media: prolonged carriage of P2 porin variants and evidence for horizontal P2 gene transfer. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1468–1474. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1468-1474.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Alphen L, Eijk P, Geelen-van den Broek L, Dankert J. Immunochemical characterization of variable epitopes of outer membrane protein P2 of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1991;59:247–252. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.247-252.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogel L, Duim B, Geluk F, Eijk P, Jansen H, Dankert J, van Alphen L. Immune selection for antigenic drift of major outer membrane protein P2 of Haemophilus influenzae during persistence in subcutaneous tissue cages in rabbits. Infect Immun. 1996;64:980–986. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.980-986.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yi K, Murphy T F. Importance of an immunodominant surface-exposed loop on outer membrane protein P2 of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1997;65:150–155. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.150-155.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yi K, Sethi S, Murphy T F. Human immune response to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in chronic bronchitis. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1247–1252. doi: 10.1086/514119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]