Abstract

The immunogenicity and protective capacity of Streptococcus pneumoniae 6B capsular polysaccharide (PS)-derived synthetic phosphate-containing disaccharide (Rha-ribitol-P-), trisaccharide (ribitol-P-Gal-Glc-), and tetrasaccharide (Rha-ribitol-P-Gal-Glc-)-protein conjugates in rabbits and mice were studied. In rabbits, all saccharides conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) evoked high levels of pneumococcal (Pn) type 6B antibodies that facilitated type-specific phagocytosis. Unlike the disaccharide rabbit antisera, tri- and tetrasaccharide rabbit antisera also reacted with 6A PS in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and promoted phagocytosis of 6A pneumococci. All these rabbit antisera passively protected mice against a Pn 6B challenge. The disaccharide conjugate-induced antiserum, however, failed to protect mice against a 6A challenge. In mice, phagocytic and protective anti-Pn 6B antibodies were only induced by the tetrasaccharide conjugate and not by PS 6B or PS 6B-protein conjugates. These antibodies did not cross-react with 6A PS in ELISA and were unable to phagocytize 6A pneumococci. In conclusion, the disaccharide and tetrasaccharide conjugates already contain epitopes capable of inducing 6B-specific, fully protective antibodies in rabbits and mice, respectively.

Worldwide, Streptococcus pneumoniae remains a major cause of acute respiratory bacterial infections, leading to approximately 1 million childhood deaths each year (23). Type 6 pneumococci are a frequent cause of pneumococcal disease in infants (6, 9, 10). Together with 14, 19F, and 23F, these pneumococci are major causes of infection in young children (so-called pediatric types) (3, 9, 23). In general, maturation of the human antibody response against capsular polysaccharides of pediatric serotypes is slow. This holds true in particular for type 6 pneumococci, for which maturation of the antibody response is the slowest of all the serotypes (4, 15). Moreover, type 6 pneumococci are frequently associated with antibiotic resistance (5, 18), and recently vancomycin tolerance in S. pneumoniae has been described (17). Therefore, there is a need for a safe and effective vaccine against pneumococci especially for infants.

Recently, the first pneumococcal (Pn) conjugate vaccine was licensed in the United States. This vaccine includes polysaccharides (PS) of serotypes 4, 6B, 9V, 19F, and 23F conjugated to CRM197 carrier protein and an oligosaccharide (OS) conjugate of serotype 18C (22). More Pn conjugates, however, will have to be included in future Pn vaccines in order to broaden the coverage to more serotypes and to address the potential problem of the shifting of the prevalence of serotypes in time, a problem which probably will be accelerated as a result of the use of currently licensed Pn-conjugate vaccines. Inclusion of more conjugates within one vaccine will start posing problems with respect to safety (too-large amounts of carrier protein and saccharide) and efficacy (immunodominancy of certain serotypes). The design of conjugates composed of only the most necessary components, i.e., only the protective saccharide epitopes and strong T-helper-cell epitopes, might be a solution for these anticipated problems. Synthetic OS conjugate vaccines can be precisely designed to a desired structure and composition (28–30). Synthetic saccharides have been produced for (among others) serotypes 4, 9V, 14, 19A/F, and 23F (13). An important first step towards a synthetic conjugate vaccine is to define minimal protective epitopes on these saccharides. The aim of this study was to examine the antigenicity and immunogenicity of synthetic serotype 6B Pn OS-protein conjugates in order to delineate the minimal saccharide structure required for induction of protective immunity in mice.

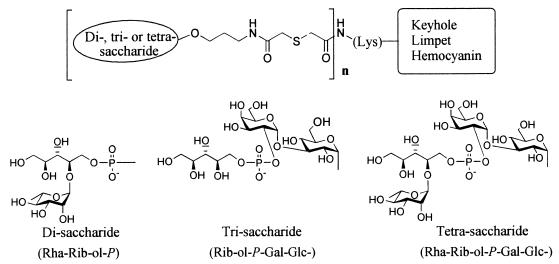

The repeating unit of Pn 6B PS consists of →3)-α-l-Rha-p-(1→4)-d-Rib-ol-(5→PO4→2)-α-d-Galp-(1→3)-α-d-Glcp-(1→ (28). The serotype 6B and 6A PS structure only differs in the rhamnosyl-ribitol linkage, which is (1→4) for the 6B PS and (1→3) for the 6A PS (13). Three overlapping fragments of the 6B PS were synthesized, namely, spacered disaccharide Rha-ribitol-P, trisaccharide ribitol-P-Gal-Glc (30), and tetrasaccharide Rha-ribitol-P-Gal-Glc- (28, 29). These fragments were conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) and tested for their immunological and protective properties in rabbits and mice. Inhibition studies with human sera obtained after vaccination with Pneumovax or Pn conjugates were performed in order to establish whether human anti-6B PS antibodies that recognize such small epitopes can be elicited.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

KLH was purchased from Calbiochem Co. (La Jolla, Calif.). N-Succinimidyl S-acetylthioacetate, N-succinimidyl bromoacetate, and N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide were obtained from Pierce Chemical Co. (Rockford, Ill.). Cyanogen bromide, adipic acid dihydrazide, β-mercaptoethylamine, 1-ethyl-3-dimethylaminopropylcarbodiimide, and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) isomer were supplied by Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). Ficoll-Paque was from Pharmacia (Uppsala, Sweden).

Conjugate synthesis.

Pn 6B PS was isolated from a 6B American Type Culture Collection strain by ethanol-calcium chloride fractionation and coupled to KLH by carbodiimide-mediated condensation as described elsewhere (32). Disaccharide α-l-Rhap-(1→4)-d-Rib-ol-[5→P→(CH2)3NH2], Trisaccharide-d-Rib-ol-(5→P→2)-α-d-Galp-(1→3)-α-d-Glcp-[1→O(CH2)3NH2], and tetrasaccharide α - l - Rhap - (1→4) - d - Rib - ol - (5→P→2) - α - d - Galp - (1→3) - α - d - Glcp - [1→O(CH2)3NH2], representing partial structures of the repeating unit of 6B PS with a 3-aminopropyl spacer, were synthesized as described previously (28, 30). The saccharides were coupled via the 3-aminopropyl spacer to carrier protein KLH in a stepwise reaction: the amino-terminal groups of the OS fragment and KLH were activated by S acetylation and Br acetylation, respectively, and coupled via a thioether linkage (2). The conjugates were purified over a Sepharose CL-6B column and dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline. Carbohydrate (7) and protein (27) contents were analyzed using PS 6B and KLH, respectively, as standards. Schematic structures of the conjugates are shown in Fig. 1. All OS conjugates had similar molar carbohydrate/protein ratios (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of synthetic di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharide conjugates. Di- and trisaccharides are overlapping fragments of the tetrasaccharide, the latter representing one repeating unit of 6B PS. Saccharides were coupled to KLH via a spacer at their reducing end.

TABLE 1.

Carbohydrate/protein ratios

| Conjugatea | Carbohydrate/protein ratio

|

|

|---|---|---|

| wt/wt | mol/molb | |

| 6B PS-KLH | 0.31 | |

| Disaccharide-KLH | 0.03 | 360 |

| Trisaccharide-KLH | 0.05 | 434 |

| Tetrasaccharide-KLH | 0.06 | 390 |

Synthetic di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharide fragments of 6B PS coupled to KLH. The OS/KLH molar ratio during the coupling reaction was approximately 4,000. After coupling and purification, conjugates were analyzed for protein and carbohydrate content.

The molar ratio between KLH and OS was calculated assuming a molar weight of 5.25 × 106 g/mol for KLH. The molar ratio of the 6B PS-KLH conjugate could not be calculated because of variability in the PS chain length.

Immunization and sera.

Inbred 8-week-old female BALB/c mice and adult female New Zealand White rabbits (Iffa-Credo, Someren, The Netherlands) were maintained at the Animal Laboratory of Utrecht University. Pairs of rabbits weighing approximately 3 kg were immunized subcutaneously at four sites with the di-, tri-, or tetrasaccharide conjugates (10 μg of saccharide per rabbit, emulsified with complete Freund's adjuvant in a total volume of 0.8 ml). Rabbits were boosted intraperitoneally with the conjugates in Freund's incomplete adjuvant at weeks 3 and 7. Blood was withdrawn at weeks 0, 2, 5, and 8.

To study the immunogenicity of 6B PS and the 6B conjugates in mice, groups of 10 mice were immunized subcutaneously at day 0 and boosted at weeks 3, 7, 10, and 14 with either 6B PS, 6B PS-KLH conjugate, or 6B OS-KLH conjugates (2.5 μg of saccharide with 20 μg of Quil A per mouse per immunization). Blood was withdrawn at weeks 3, 5, 9, 16, and 25, and 6B-specific antibody titers were determined. In order to investigate the ability of the synthetic OS-protein conjugates to induce protection against a 6B challenge, second groups of mice were immunized with the 6B OS conjugates, using the same protocol as in the first experiment, followed by a challenge with 6B pneumococci at week 25 as described below.

Rabbit anti-6B PS antiserum was raised by formalin-killed S. pneumoniae type 6B, as described previously (12). Two human vaccination serum pools were obtained by pooling 10 infant conjugate antisera (heptavalent Pn CRM197-conjugate vaccine containing 4 μg of 6B PS coupled to CRM197, sera obtained at 16 months; Wyeth-Lederle Vaccines and Pediatrics, Rochester, N.Y.) (22), and 10 antisera from adults vaccinated with a 23-valent PS vaccine (Pneumovax) containing 10 μg of 6B PS. These quality control sera were obtained from David Goldblatt (London, England) and have been described previously (16).

ELISA.

To measure anti-6B antibodies in mouse and rabbit sera by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), Nunc MaxiSorp plates were coated directly with 6B or 6A PS (1 μg/ml in saline) overnight at 37°C as described previously (1). Alternatively, to measure antibodies in human pooled vaccination antisera and rabbit anti-6B antiserum (described above) that recognize the synthetic 6B OS, the various synthetic OS-protein conjugates were coated (4 μg of protein/ml in 0.1 M Na2CO3 buffer, pH 9.6) overnight at 4°C. ELISA was further performed, as described previously (2), using horseradish peroxidase-labeled conjugates (goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G [IgG], goat anti-mouse IgG, or goat anti-human IgG; drawer 2517; Nordic Immunological Laboratories, Capistrano Beach, Calif.). Antibody titers were calculated as log10 (reciprocal dilution giving an absorbance of 0.5) and corrected against a rabbit anti-6B antiserum (12), which was included on every ELISA plate.

The specificity of ELISA was determined by inhibition ELISA. Pn 14 and 17F PS were purified as described previously (2, 32). Sera, diluted to an absorbance of 0.5, were incubated overnight at 4°C with different amounts of PS 6A, 6B, 14, and 17F as inhibitors. No inhibition was observed with PS 14 and 17F in all inhibition ELISAs (data not shown). Percentages of inhibition were calculated, after subtracting the absorbance of the control wells without serum, as [(1-A450 of serum with inhibitor)/A450 of serum without inhibitor] × 100%. The inhibitor concentration (grams per milliliter) at which 50% reduction of binding was reached (IC50) was calculated by interpolation assuming linearity near the point of 50% inhibition. Inhibition titers were calculated as log10 (1/IC50).

Phagocytosis assay.

The assay was performed as described previously (12). This assay is standardized by using only functional components that are of human origin (e.g., human complement and human polymorphonuclear leukocytes [PMN]), is serotype specific, and exhibits, in general, highly significant correlations with ELISA (12) and the classical killing assay (unpublished results). Pn strains of serotypes 6A (American Type Culture Collection) and 6B (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.; strain DS2215-94) were grown three times consecutively to log phase to ensure high encapsulation (12) and subsequently heat inactivated and FITC labeled. Human pooled serum was depleted of IgG by protein G affinity chromatography and used as a complement source. Human PMN were isolated from the blood of healthy, Fcγ receptor-typed volunteers (11) by a Ficoll-Histopaque gradient. Complement (2% final concentration in the assay), serum dilutions, and samples of 2.5 × 106 pneumococci were added to each well. After 30 min of opsonization at 37°C, 2.5 × 105 PMN were added to each well and phagocytosis was performed for 30 min at 37°C. FITC-positive PMN were measured by flow cytometry. The percentage of FITC-positive PMN was used as a measure for the phagocytic activity of the serum. Results are expressed as 25% phagocytosis titers (log10 of the serum dilution resulting in 25% FITC-positive PMN).

Protection experiments.

Rabbit sera obtained 1 week after the second booster injection were heat inactivated, pooled for each OS conjugate group, and used for passive protection experiments with mice. Groups of 16 female inbred BALB/c mice 25 weeks old were injected intravenously with 0.5 ml of pooled conjugate antiserum or with 0.5 ml of normal rabbit serum (n = 16). After 2 h, 10 mice of each group were challenged intraperitoneally with 1.5 × 107 CFU (15 times the 50% lethal dose [LD50]) of S. pneumoniae type 6B and 6 mice were challenged with 5.0 × 101 CFU (10 times the LD50) of S. pneumoniae type 6A. Survival was recorded daily for 14 days.

Mice were immunized with the OS conjugates as described above and challenged at week 25 intraperitoneally with 1.5 × 107 CFU (15 times the LD50) of S. pneumoniae type 6B. Survival was recorded daily for 14 days.

Statistical analysis.

Correlations between ELISA and fluorescence-activated cell sorter phagocytosis titers were analyzed by linear regression tests. The statistical significance of correlations was assessed by Pearson correlation analysis. Challenge survival data were analyzed by the Fisher exact test. Differences in ELISA titer and phagocytosis titer between survivors and nonsurvivors, as well as differences in ELISA titer among different immunization groups, were analyzed by Student's t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Immunogenicity of synthetic 6B OS conjugates and epitope specificity of the elicited antisera in rabbits.

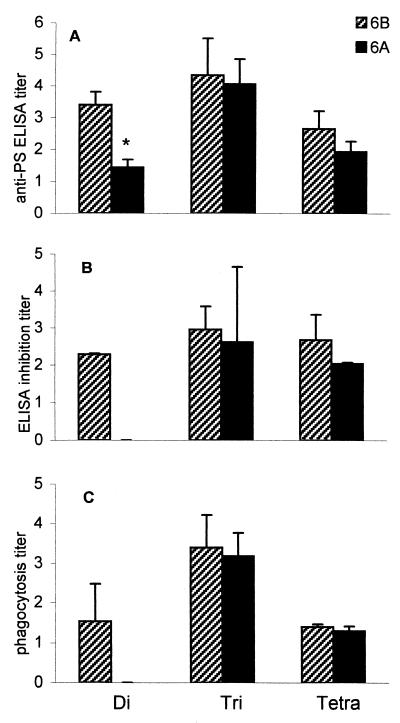

In none of the rabbits could anti-6B antibodies be detected before immunization (data not shown), whereas all rabbits produced anti-6B PS antibodies after the first immunization with the synthetic conjugates. Anti-6B antibody titers strongly increased after the booster injections (for the sake of clearness only week-8 titers are shown) (Fig. 2A). Specificity and phagocytic capacity of anti-OS conjugate antibodies were determined for the antisera obtained at week 8 (Fig. 2). Tri- and tetrasaccharide conjugates, but not the disaccharide conjugate, were able to induce anti-6A antibodies (Fig. 2A). These results were in agreement with the inhibition ELISA results (PS 6B as the coated antigen; Fig. 2B). The binding of all antisera elicited with the conjugates was inhibited with 6B PS. In contrast to what was found for the other OS conjugate antisera, the binding of the disaccharide conjugate antisera to 6B PS was not prevented by 6A PS (Fig. 2B).

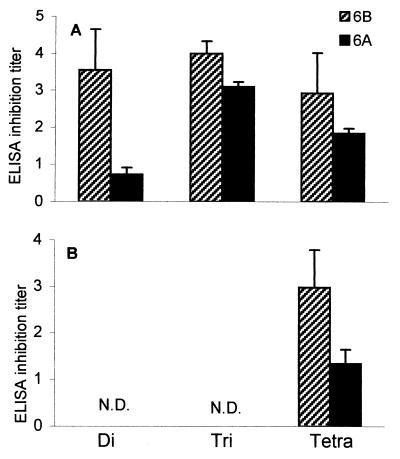

FIG. 2.

Rabbit antisera elicited by disaccharide OS conjugate were specific for serotype 6B. Di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharide conjugate antisera (n = 2) at 1 week after the second booster injection were analyzed by ELISA, inhibition ELISA, and a phagocytosis assay. Results are expressed as mean titers ± SD (n = 2). (A) Sera were analyzed for antibody titers against PS 6B and 6A by ELISA using respectively, 6B PS and 6A PS as the coating antigen. ∗, antibody titer not significantly above preimmunization antibody titer. (B) Inhibition of binding of sera to 6B PS. As inhibitors, 6B PS or 6A PS were used. (C) Promotion of phagocytosis of serotype 6B and 6A pneumococci, measured in a serotype-specific phagocytosis assay based on flow cytometry.

To investigate their phagocytic capacities OS conjugate antisera (week 8) were tested in a phagocytosis assay based on flow cytometry using highly encapsulated 6B and 6A pneumococci. All OS conjugate antisera were able to promote phagocytosis of 6B pneumococci, whereas only tri- and tetrasaccharide conjugate antisera facilitated phagocytosis of 6A pneumococci (Fig. 2C). When sera from all rabbits obtained at different time points were included, a highly significant correlation between 6B phagocytosis titers and 6B ELISA titers was observed (r = 0.93; P < 0.001; n = 24). In conclusion, tri- and tetrasaccharide conjugates both elicited functional 6A and 6B antibodies, whereas disaccharide antibodies were 6B specific.

Immunogenicities of 6B PS, 6B PS-KLH conjugate, and synthetic 6B OS-KLH conjugates in mice.

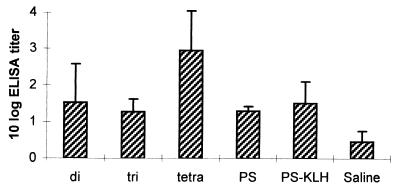

To study interspecies differences, mice were immunized with 6B PS, 6B PS-KLH conjugate, and the di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharide-KLH conjugates. This allowed a comparison of the immunogenicities of the OS conjugates with the immunogenicities of 6B PS-KLH and 6B PS. Pn 6B PS was used as the coating antigen in the ELISA. Anti-6B antibody titers were low, even after repeated immunizations, except for the tetrasaccharide conjugate (Fig. 3). All tetrasaccharide conjugate-immunized mice produced sustained levels of anti-6B antibodies, whereas for the other immunizations only a few mice per group showed detectable 6B PS-specific antibodies. In contrast to 6B PS and 6B PS-KLH conjugate, none of the OS conjugates induced anti-6A antibodies in mice (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Tetrasaccharide conjugate induced highest anti-PS 6B responses in mice. Mean antibody titers ± SD (n = 10) against 6B PS were determined by ELISA using antisera obtained at week 25 after primary immunization with 6B PS, 6B PS-KLH conjugate, or 6B di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharide-KLH conjugates. The tetrasaccharide conjugate induced significantly higher anti-PS 6B antibody titers than the disaccharide (P < 0.01), trisaccharide (P < 0.001), 6B PS (P < 0.001), 6B PS-KLH conjugate (P < 0.05), and saline (P < 0.0001).

Specificity and phagocytic capacity of mouse anti-6B synthetic OS conjugate antisera.

In order to study the specificity and phagocytic capacity of mouse anti-6B synthetic OS conjugate antisera, a second immunization experiment was performed. In this experiment, using the same protocol for immunization and bleeding, mice were immunized with the synthetic OS conjugates only. Because of the poor immunogenicities of the 6B PS and 6B PS-KLH conjugate in the first experiment, it was decided not to include these vaccines in this experiment. Similar immunogenicity profiles were observed for the synthetic OS conjugates (data not shown).

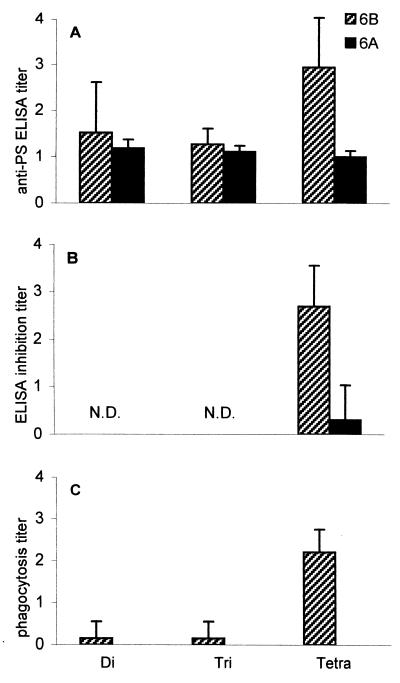

The specificity of the synthetic OS-protein conjugate antisera of week 25 (second immunization experiment) was studied in more detail by an inhibition ELISA in which 6B PS was used as a coating antigen and 6A and 6B PS were used as inhibitors. Tetrasaccharide conjugate antisera could be inhibited by 6B PS but not by 6A PS (Fig. 4B). The biological functionality of these OS conjugate antisera was tested in a phagocytosis assay using highly encapsulated 6B or 6A pneumococci. Antitetrasaccharide sera were able to promote phagocytosis of 6B pneumococci but not, as expected, of 6A pneumococci (Fig. 4C). Phagocytosis titers of tetrasaccharide conjugate antisera correlated significantly with ELISA titers (r = 0.77; P < 0.01; n = 10).

FIG. 4.

Tetrasaccharide conjugate-induced 6B-specific, phagocytic antibodies in mice. Di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharide conjugate antisera (n = 10) were analyzed at week 25 after primary immunization for sustained antibody levels by ELISA (A), inhibition ELISA (B), and phagocytosis assay (C). Results are expressed as mean titers ±SD (n = 10). Sera were analyzed for inhibition of binding of sera to 6B PS (coating antigen), with 6B PS or 6A PS as inhibitors in an inhibition ELISA (B) and for promotion of phagocytosis of serotype 6B and 6A pneumococci, measured in a serotype-specific phagocytosis assay based on flow cytometry (C). None of the control animals were able to produce anti-6B or -6A PS antibodies (data not shown). N.D., not done.

Rabbit and human vaccination antisera recognize the synthetic OSs.

In order to determine whether vaccination of humans with either Pn conjugate vaccine or Pneumovax leads to production of antibodies that recognize the epitopes defined by the synthetic OS conjugates used in this study, two pools of human 6B antisera (sera taken from infants vaccinated with Pn PS conjugates and adults vaccinated with Pneumovax) were tested for their capacities to bind to the 6B OS conjugates. A rabbit antiserum elicited with whole 6B pneumococci (12) was tested in the same assays. The rabbit anti-6B PS was able to bind to all three conjugates in ELISA (log10 antibody titers [means of two experiments ±standard deviations {SD}]: disaccharide conjugate 2.7 ± 0.02; trisaccharide conjugate, 3.2 ± 0.03; tetrasaccharide conjugate, 2.2 ± 0.02). The specificity of this binding to the conjugates was investigated by inhibition ELISA. The binding to the tri- and tetrasaccharide conjugates was inhibited by 6A PS and 6B PS, whereas the binding to the disaccharide conjugate was only inhibited by 6B PS (Fig. 5A). Infant conjugate antisera only recognized the tetrasaccharide fragment (log10 antibody titer [mean of two experiments ± SD]: 2.2 ± 0.05 [n = 2]). None of the OS conjugates were recognized by the Pneumovax serum pool (data not shown). The binding of human conjugate antisera to the OS conjugates was inhibited by PS 6A and 6B but not by any other PS or KLH (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

OS conjugates contained epitopes for anti-6B PS antibodies induced by vaccination of either humans with a heptavalent conjugate vaccine or rabbits with 6B pneumococci. Binding to OS conjugates of rabbit anti-Pn 6B antiserum (A) or pooled sera from 10 infant 6B conjugate vaccinees (B) was inhibited by 6A PS and 6B PS. Results are expressed as means of two experiments ±SD. N.D., not done.

Transfer protection experiments with rabbit antisera.

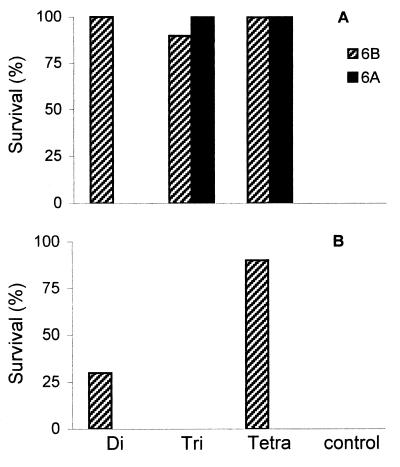

To investigate the protective capacities of the rabbit anti-di-, -tri-, and -tetrasaccharide conjugate antisera, mice were injected intravenously with rabbit conjugate antisera or normal rabbit serum and challenged with 15 times the LD50 of 6B pneumococci or 10 times the LD50 of 6A pneumococci. Following challenge with Pn type 6B organisms, 100% protection was observed for mice that received di- or tetrasaccharide conjugate antisera (P for both, < 0.001) and 90% protection was observed for mice that received the trisaccharide conjugate antiserum (P < 0.001), whereas all mice in the control group died. Disaccharide conjugate antiserum was not able to confer to mice passive protection against a 6A challenge. All mice that received the tri- or tetrasaccharide conjugate antiserum survived the 6A challenge (P < 0.01 for both; Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Protective capacities of OS conjugates and OS conjugate-derived rabbit antisera in mice. Shown are percentages of survival for mice after serotype 6B and 6A challenge. (A) Passive protection of mice against serotype 6B and 6A challenge 2 h after intravenous injection with rabbit anticonjugate antisera or normal rabbit serum (control). (B) Active protection of mice against a 6B challenge after immunization with di-, tri-, or tetrasaccharide conjugates (second immunization experiment). Challenge was performed 25 weeks after primary immunization.

Induction of protection by synthetic 6B OS-protein conjugates.

To study whether the synthetic 6B OS-protein conjugates can induce protective antibodies in mice, immunized mice from the second immunization experiment were challenged with 15 times the LD50 of 6B pneumococci at week 25. All mice within the saline group died (Fig. 6B). None of the trisaccharide-immunized mice and only three (30%) of the disaccharide-immunized mice survived (P = 0.21), whereas nine mice (90%) in the tetrasaccharide group survived the challenge (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6B). Survivors (n = 12) had significantly higher 6B antibody titers (P < 0.01; median log10 titer: 3.6) and 6B phagocytosis titers (P < 0.001; median log10 titer: 2.2) than nonsurvivors (n = 28; median log10 antibody and phagocytosis titers: 0).

DISCUSSION

The immunogenicities, antigenicities, and protective capacities of small synthetic 6B di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharide conjugates in rabbits and mice were investigated. In rabbits, all conjugates were able to induce anti-6B PS antibodies that could passively protect mice against a 6B challenge. Antibodies to the disaccharide conjugate were specific for 6B and failed to confer protection to mice against a 6A challenge. In mice, only antitetrasaccharide antibodies induced serotype 6B-specific antibodies that provided protection against challenge with 6B pneumococci. We conclude that the minimal saccharide fragment capable of inducing specific, phagocytic, and highly protective anti-6B antibodies is the disaccharide in rabbits and the tetrasaccharide in mice.

For both rabbits and mice 6B ELISA titers correlated significantly with 6B phagocytosis assay titers. Since survivors of 6B challenge had significantly higher serum titers in 6B ELISA and the 6B phagocytosis assay, both in vitro parameters can be used as predictors for survival after challenge. Therefore, the absence of 6A ELISA and phagocytosis assay titers in the tetrasaccharide conjugate-immunized mice predicts that these mice are not protected against a 6A challenge. Since the 6A challenge dose was 105-fold lower than the 6B challenge dose, the absence of 6A cross-protection in the passive protection experiment was certainly not simply a result of an insufficient antibody concentration in the serum. It is known that mice poorly respond to 6B PS (8). Therefore, in mice it is interesting that the tetrasaccharide conjugate induced significantly higher antibody titers than the 6B PS and PS-KLH conjugate, resulting in a higher level of protection. Since 6B OS fragments and 6B PS were coupled to KLH by different coupling methods, the possibility that other factors beside saccharide length contributed to this observed difference in immunogenicity cannot be excluded. Nevertheless, synthetic OS conjugates that induce antibody levels comparable to, or even higher than, those induced by PS conjugates in mice or monkeys have been described (19, 21). These results and our results therefore suggest that the approach of using synthetic OSs in the design of improved Pn vaccines is a valid one and worthwhile to pursue when Pn conjugate vaccines including (much) higher numbers of serotypes have to be developed.

In both the disaccharide and the tetrasaccharide the Rha-α(1→4)-Rib-ol structure, which forms the essential difference between serotype 6A and 6B, is present. The trisaccharide and the tetrasaccharide contain the Rib-ol-(5→P→2)-α-d-Galp-(1→3)-α-d-Glcp structure, which is common to both serotypes 6A and 6B. Interestingly, our immunological results for rabbits are completely in line with the structural differences between these OSs. The disaccharide, which contains only the 6B-specific structure, only induces antibodies specific for 6B PS. Both the trisaccharide and tetrasaccharide, in which a structure common to 6A and 6B is present, elicited antibodies against both serotypes. Part of the antibodies elicited by the tetrasaccharide, however, will certainly also be only specific for 6B and are probably directed against the same structure present in the disaccharide. Our results for mice support this notion. Therefore, we concluded that the disaccharide contains a serotype 6B-specific epitope, that the trisaccharide contains a common 6A and 6B epitope, and that the tetrasaccharide contains both a 6B-specific and a common 6A and 6B epitope.

The finding that these small saccharide fragments can induce highly specific antibodies that can discriminate between closely related serotype 6A and 6B pneumococci suggests that these conjugates can be used for the development of 6B- or 6A-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) recognizing precisely defined protective 6A or 6B PS epitopes. Furthermore, these synthetic conjugates can be used for epitope mapping type 6 MAbs. Indeed, an analysis of the binding of two type 6 PS MAbs (26) to the three synthetic OS-KLH conjugates in ELISA revealed the putative epitope of these MAbs. This epitope structure appeared to have a predictive value for MAb cross-reactivity to 6A PS (W. T. M. Jansen and G. P. J. M. van den Dobbelsteen, unpublished data). In addition, synthetic OS conjugates lack common impurities and cell wall PS that are copurified in PS preparations. Therefore, using synthetic OS conjugates instead of PS as the coating antigen in ELISA can be the solution for the problems recently described for the standardized Pn ELISA (25, 34).

Epitope size on Pn PS can vary among serotypes (1, 2), among species (1), and with age (20). The fact that rabbits and mice clearly recognize different epitopes on 6B PS is therefore not surprising. It has been suggested that, unlike mice, rabbits can produce two types of anticarbohydrate antibodies: those with a cavity-like antigen-binding site, which recognize one or two monosaccharides, and antibodies with a groove-like antigen-binding site, which recognize elongated sugar epitopes of up to six or seven monosaccharides (1, 33). In addition, the use of different adjuvants might also have played a role. For instance, studies with meningococcal OS-protein conjugates in rabbits with the adjuvant Quil A showed that this adjuvant had a strong influence on the epitope specificity of the antibodies induced (31). Although mice and rabbit models reveal the existence of protective PS epitopes smaller than one repeating unit of the PS, the situation might be different for humans. Alonso de Velasco et al. showed that the epitope recognized by human IgG on PS 23F is larger than one repeating unit which is the epitope recognized by rabbit IgG (1). Moreover, an observed trend is that longer saccharides that comprise more than four repeating units induce higher antibody titers in rabbits (14) and humans (20), probably because of the presence of conformational epitopes. The absence of displayed conformational epitopes might be one of the drawbacks for small synthetic OS conjugate vaccines.

To investigate whether the minimal PS 6B epitopes defined in our mouse and rabbit studies are recognized by human IgG antibodies, human pooled vaccination antisera were tested for binding with the OS conjugates in ELISA. Human conjugate antisera were able to bind to the tetrasaccharide. Therefore, this saccharide fragment probably comprises an epitope for human anti-6B conjugate IgG antibodies. The lack of binding of Pneumovax antisera to OS conjugates might be explained by differences in affinity or epitope specificity. The ability of rabbit anti-6B antiserum to bind all three OS conjugates in ELISA and the 6B specificity of disaccharide-binding antibodies are in agreement with the potential of OS conjugates to induce anti-PS 6B (specific) antibodies in rabbits. Therefore, the presence of an epitope for human 6B conjugate antibodies on the tetrasaccharide supports the possibility that such synthetic OS conjugates may induce anti-6B antibodies in humans as well. Clearly, human vaccination studies with the OS conjugates are required to prove this hypothesis.

Although synthetic saccharide-KLH conjugates have been proved to be safe and immunogenic in both animals (1, 2) and humans (24), KLH is not the first choice as a carrier in human conjugate vaccines. The potential of synthetic conjugates to induce anti-6B antibodies in humans should therefore be evaluated by administration of OS conjugates to humans using a clinically relevant carrier, dosage, and formulation (21). Once the capsule synthesis machinery of the pneumococcus is understood better, enzymatic, large-scale synthesis of saccharide fragments of different lengths may be within reach. This will enable the development of optimized synthetic Pn conjugate vaccines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Wyeth-Lederle Vaccines and Pediatrics for providing antisera obtained from infants vaccinated with their 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. We acknowledge David Goldblatt for the kind gift of his Pn quality control QC sera and Dirk Lefeber for generating Fig. 1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso De Velasco E, Verheul A F M, van Steijn A M P, Dekker H A T, Feldman R G, Fernandez I M, Kamerling J P, Vliegenthart J F G, Verhoef J, Snippe H. Epitope specificity of rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) elicited by pneumococcal type 23F synthetic oligosaccharide- and native polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines: comparison with human anti-polysaccharide 23F IgG. Infect Immun. 1994;62:799–808. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.799-808.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso De Velasco E, Verheul A F M, Veeneman G H, Gomes L J F, van Boom J H, Verhoef J, Snippe H. Protein-conjugated synthetic di- and trisaccharides of pneumococcal type 17F exhibit a different immunogenicity and antigenicity than tetrasaccharide. Vaccine. 1993;11:1429–1436. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90172-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso De Velasco E, Verheul A F M, Verhoef J, Snippe H. Streptococcus pneumoniae: virulence factors, pathogenesis, and vaccines. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:591–603. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.591-603.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borgono J M, Mclean A A, Vella P P. Vaccination and revaccination with polyvalent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines in adults and infants. Proc Soc Biol Med. 1978;157:148–154. doi: 10.3181/00379727-157-40010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breiman R F, Butler J C, Tenover F C, Elliott J A, Facklam R R. Emergence of drug-resistant pneumococcal infections in the United States. JAMA. 1994;271:1831–1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler J C, Breiman R F, Lipman H B, Hofmann J, Facklam R R. Serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae infections among preschool children in the United States, 1978-1994: implications for development of a conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:885–889. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubois M, Gilles K A, Hamilton J K, Rebers P A, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;3:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairchild R L, Braley-Mullen H. Characterization of the murine immune response to type 6 pneumococcal polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1983;39:615–622. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.2.615-622.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray B M, Converse G M, Dillon H C., Jr Serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae causing disease. J Infect Dis. 1979;140:979–983. doi: 10.1093/infdis/140.6.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Invasive Bacterial Infection Surveillance Group. Prospective multicentre hospital surveillance of Streptococcus pneumoniae disease in India. Lancet. 1999;353:1216–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jansen W T M, Breukels M A, Snippe H, Sanders E A M, Verheul A F M, Rijkers G T. Fcγ receptor polymorphisms determine the magnitude of in vitro phagocytosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae mediated by pneumococcal conjugate sera. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:888–891. doi: 10.1086/314920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jansen W T M, Gootjes J, Zelle M, Madore D V, Verhoef J, Snippe H, Verheul A F M. Use of highly encapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae strains in a flow-cytometric assay for assessment of the phagocytic capacity of serotype-specific antibodies. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:703–710. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.5.703-710.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamerling J P C. Pneumococcal polysaccharides: a chemical view. In: Tomasz A, editor. Streptococcus pneumoniae, molecular biology and mechanisms of disease. New York, N.Y: Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.; 2000. pp. 81–114. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laferriere C A, Sood R K, De Muys J M, Michon F, Jennings H J. Streptococcus pneumoniae type 14 polysaccharide-conjugate vaccines: length stabilization of opsonophagocytic conformational polysaccharide epitopes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2441–2446. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2441-2446.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leinonen M, Sakkinen A, Kallioski R, Luotonen J, Timonen M, Makela H. Antibody response to 14-valent pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide vaccine in pre-school age children. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1986;5:39–44. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198601000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez J E, Romero-Steiner S, Pilishvili T, Barnard S, Schinsky M F, Goldblatt D, Carlone G M. A flow cytometric opsonophagocytic assay for measurement of functional antibodies elicited after vaccination with 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:581–587. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.4.581-586.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novak R, Henriques B, Charpentier E, Normark S, Tuomanen E. Emergence of vancomycin tolerance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nature. 1999;399:590–593. doi: 10.1038/21202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parkinson A J, Davidson M, Fitzgerald M A, Bulkow L R, Parks D J. Serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance patterns of invasive isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae: Alaska 1986-1990. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:461–464. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peeters C C A M, Evenberg D, Hoogerhout P, Kayhty H, Saarinen L, van Boeckel C A A, van der Marel G A, van Boom J H, Poolman J T. Synthetic trimer and tetramer of 3-β-d-ribose-(1-1)-d-ribitol-5-phosphate conjugated to protein induce antibody responses to Haemophilus influenzae type b capsular polysaccharide in mice and monkeys. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1826–1833. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.1826-1833.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pichichero M E, Porcelli S, Treanor J, Anderson P. Serum antibody responses of weanling mice and two-year-old children to pneumococcal-type 6A-protein conjugate vaccines of differing saccharide chain lengths. Vaccine. 1998;16:83–91. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pozsgay V, Chu C, Pannell L, Wolfe J, Robbins J B, Schneerson R. Protein conjugates of synthetic saccharides elicit higher levels of serum IgG lipopolysaccharide antibodies in mice than do those of the O-specific polysaccharide from Shigella dysenteriae type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5194–5197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rennels M B, Edwards K M, Keyserling H L, Reisinger K S, Hogerman D A, Madore D V, Chang I, Paradiso P R, Malinoski F J, Kimura A. Safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal vaccine conjugated to CRM197 in United States infants. Pediatrics. 1998;101:604–611. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siber G R. Pneumococcal disease: prospects for a new generation of vaccines. Science. 1994;265:1385–1387. doi: 10.1126/science.8073278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slovin S F, Ragupathi G, Adluri S, Ungers G, Terry K, Kim S, Spassova M, Bornmann W G, Fazzari M, Dantis L, Olkiewicz K, Lloyd K O, Livingston P O, Danishefsky S J, Scher H I. Carbohydrate vaccines in cancer: immunogenicity of a fully synthetic globo H hexasaccharide conjugate in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5710–5715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snippe H, Jansen W T M, Kamerling J P, Lefeber D J. Towards a synthetic pneumococcal vaccine: synthetic oligosaccharides as tools for improving the specificity of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:325. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.2.325-325.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soininen A, van den Dobbelsteen G P J M, Oomen L, Kayhty H. Are the enzyme immunoassays for antibodies to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides serotype specific? Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:468–476. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.3.468-476.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorensen K, Brodbeck U. A sensitive protein assay method using micro-titer plates. Experientia. 1986;42:161–162. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thijssen M J L, Bijkerk M H G, Kamerling J P, Vliegenthart J F G. Synthesis of four spacer-containing ‘tetrasaccharides’ that represent four possible repeating units of the capsular polysaccharide of Streptococcus pneumoniae type 6B. Carbohydr Res. 1998;306:111–125. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(97)10013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thijssen M J G, Halkes K M, Kamerling J P, Vliegenthart J F G. Synthesis of a spacer-containing tetrasaccharide representing a repeating unit of the capsular polysaccharide of Streptococcus pneumoniae type 6B. Bioorg Med Chem. 1994;2:1309–1317. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)82081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thijssen M J G, van Rijswijk M N, Kamerling J P, Vliegenthart J F G. Synthesis of spacer-containing di- and tri-saccharides that represent parts of the capsular polysaccharide of Streptococcus pneumoniae type 6B. Carbohydr Res. 1998;306:93–109. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(97)00271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verheul A F M, Poolman J T, Snippe H, Verhoef J. The influence of the adjuvant Quil A on the epitope specificity of meningococcal lipopolysaccharide anti-carbohydrate antibodies. Mol Immunol. 1991;28:1193–1200. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(91)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verheul A F M, Versteeg A A, De Reuver M J, Jansze M, Snippe H. Modulation of the immune response to pneumococcal type 14 capsular polysaccharide-protein conjugates by the adjuvant Quil A depends on the properties of the conjugates. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1078–1083. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1078-1083.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood C, Kabat E A. Immunochemical studies of conjugates of isomaltosyl oligosaccharides to lipid: specificities and reactivities of the antibodies formed in rabbits to stearyl-isomaltosyl oligosaccharides. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1981;212:262–276. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(81)90366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu X, Sun Y, Frasch C, Concepcion N, Nahm M H. Pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide preparations may contain non-C-polysaccharide contaminants that are immunogenic. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:519–524. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.4.519-524.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]