Abstract

Aim:

Research has shown that preventative intervention in individuals at ultra-high risk of psychosis (UHR) improves symptomatic and functional outcomes. The STEP trial aims to determine the most effective type, timing and sequence of interventions in the UHR population by sequentially studying the effectiveness of (1) support and problem solving, (2) cognitive-behavioural case management, and (3) antidepressant medication with an embedded fast-fail option of (4) omega-3 fatty acids or low-dose antipsychotic medication. This paper presents the recruitment flow and baseline clinical characteristics of the sample.

Methods:

STEP is a sequential multiple assignment randomised trial (SMART). We present the baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and acceptability and feasibility of this treatment approach as indicated by the flow of participants from first contact up until enrolment into the trial. Recruitment took place between April 2016 and January 2019.

Results:

Of 1343 help-seeking young people who were considered for participation, 402 participants were not eligible and 599 declined/disengaged, resulting in a total of 342 participants enrolled in the study. The most common reason for exclusion was an active prescription of antidepressant medication. Eighty-five percent of the enrolled sample had a non-psychotic DSM-5 diagnosis and symptomatic/functional measures showed a moderate level of clinical severity and functional impairment.

Discussion:

The present study demonstrates the acceptability and participant’s general positive appraisal of sequential treatment. It also shows, in line with other trials in UHR individuals, a significant level of psychiatric morbidity and impairment, demonstrating the clear need for care in this group and that treatment is appropriate.

Keywords: antidepressant medication, clinical trial, prodrome, psychosis, ultra-high risk

1. INTRODUCTION

The introduction of the at-risk mental state framework to prospectively identify young people at ‘clinical’ or ‘ultra-high’ risk (UHR) for psychosis resulted in a wide range of candidate early interventions being trialled, aiming to improve symptomatic and functional outcomes in this population. The results of these trials, ranging from (single and combined) psychological (Ising et al., 2016; Miklowitz et al., 2014; Morrison et al., 2012; Stain et al., 2016; van der Gaag et al., 2012), pharmacological (McGlashan et al., 2006; McGorry et al., 2013; Woods et al., 2017), and nutritional (Amminger et al., 2010; Kantrowitz et al., 2015; Nelson, Amminger, Yuen, Markulev, et al., 2018; Woods et al., 2013) interventions, showed that early treatment is associated with better outcomes (Preti & Cella, 2010; Stafford, Jackson, Mayo-Wilson, Morrison, & Kendall, 2013; van der Gaag, Smit, et al., 2013; McGorry, Mei, Hartmann, Yung, & Nelson, 2021; Mei et al., 2021). However, recent (network) meta-analytic studies failed to find evidence in support of any specific type of intervention over others (Davies, Cipriani, et al., 2018; Davies, Radua, et al., 2018; Devoe, Farris, Townes, & Addington, 2019). Given the now widely recognised heterogeneity of the UHR population (Fusar-Poli et al., 2016; Nelson & Yung, 2009; van Os & Guloksuz, 2017), the current lack of conclusive evidence for a single most effective form of intervention for the group as a whole is unsurprising. This indicates the need for more ‘adaptive’ intervention trials, i.e. trials which tailor the treatment type and intensity to an individual’s needs and subsequently adapt this treatment according the individual’s response and characteristics over time, in order to be able to determine the optimal type, timing and sequence of treatments in the UHR population (Murphy, 2005).

1.1. Clinical staging

The idea of adaptive intervention is inherent to the clinical staging framework. Clinical staging, a transdiagnostic heuristic approach adapted from other areas of medicine, blends a dimensional approach to mental illness classification with a categorical overlay of stepwise anchors for stage-specific treatment selection (McGorry, Hickie, Yung, Pantelis, & Jackson, 2006; Scott et al., 2013; McGorry & Hickie, 2019). It also allows for understanding and testing neurobiological and psychosocial processes underlying the onset and progression of mental illness across the syndromal landscape of emerging mental illness. An individual’s clinical presentation is mapped onto the spectrum of mental illness, facilitating treatment selection and offering a prognosis of possible progression/remission trajectories (Mei, McGorry, & Hickie, 2019). Stages are defined using symptom severity, specificity, persistence and disability. An early stage is typified by mild symptom severity, a lack of specificity, and mild functional impairment; an advanced stage is associated with severe symptom burden, clearer syndromal specificity and stability, although comorbid syndromes accumulate too, significant functional impairment and persistent/recurrent patterns of illness (Cross et al., 2014; Hickie et al., 2013).

Clinical staging applied to UHR intervention proposes a sequential approach to treatment, with the safest, most benign, and least specialised interventions offered initially, and more targeted, more intensive interventions with increased risk of adverse effects, provided only to those who do not respond to initial steps in the intervention (Nelson, Amminger, Yuen, Wallis, et al., 2018). Intervention is, however, proactive, seeks to be pre-emptive, and identifies early failure to respond, rather than waiting for deterioration. This approach leads to a stepwise enrichment of the sample: non-responders to early simple interventions are likely to be enriched for higher transition rates and higher functional impairment. By sequentially enriching the UHR sample, the issues of ‘false positives’, low statistical power due to low transition rates, and ethical concerns (e.g. overtreatment) are addressed (van Os & Guloksuz, 2017; Ajnakina, David, & Murray, 2018; Fusar-Poli et al., 2018; Carpenter, 2018; Guloksuz & van Os, 2018; but see McGorry & Mei, 2020; McGorry & Nelson, 2020; Yung et al., 2021). Offering low risk, less specific and benign treatment as a first step may enable those with milder or self-limiting problems to remit, while those who do not respond to this first step - likely representing a subset of UHR at greater risk - can move quickly on to more specific and intensive treatment.

1.2. Adaptive trials

To be able to empirically test this staged treatment approach it is necessary to move away from traditional randomized controlled trials consisting of a single phase and type of treatment. A sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART) design (Murphy, 2005) is perfectly suited for the purpose of evaluating multi-stage treatment trials and build the evidence-base to support adaptive clinical care (Bhatt & Mehta, 2016; Bothwell, Avorn, Khan, & Kesselheim, 2018). In a SMART, individuals are randomisedd to different treatments at each critical decision stage, where randomisation depends on the individual’s response (e.g., responder vs non-responder) up to that stage. SMART trials have been increasingly implemented in a variety of fields, beginning in cancer research (Auyeung et al., 2009), and more recently, in the field of psychiatry, such as schizophrenia (Shortreed & Moodie, 2012), insomnia (Morin et al., 2020) and mood disorders (Kilbourne et al., 2014).

The STEP study aimed to determine the most effective type, timing and sequence of intervention in the UHR population. More specifically, it evaluated the short-term and long-term symptomatic and functional outcomes of a stepped treatment sequence: a general, benign psychosocial intervention strategy (Step 1: supportive problem solving therapy), a more intensive and specialised psychological intervention (Step 2: CBT), and finally a psychopharmacological intervention (Step 3: antidepressant medication) with an embedded rescue option consisting of a low-dose antipsychotic or omega-3 fatty acid (‘fast fail’ option). These particular steps and order were chosen for their suggested benefit and safety (Nelson, Amminger, Yuen, Wallis, et al., 2018). Psychological interventions, specifically CBT, have been shown to be particularly beneficial and safe (Mei et al., 2021; van der Gaag, van den Berg, & Ising, 2019). Although not yet empirically tested, naturalistic evidence points to the benefit of antidepressant medication in UHR, possibly being more appropriate as first-line therapy compared to antipsychotic medication (Cornblatt et al., 2007; Fusar-Poli et al., 2015). An in-depth discussion of these issues is provided in the STEP protocol paper (Nelson, Amminger, Yuen, Wallis, et al., 2018). The STEP study also aimed to explore biological, psychological, and cognitive moderators and mediators of response in order to inform a more personalised approach to treatment, i.e., matching treatment to individual patients biological and psychological profile.

In this paper, we present the baseline demographic characteristics and diagnostic, symptomatic, and functional profile of the STEP study sample. Study recruitment flow and issues will be presented.

2. METHODS

2.1. Setting

This community study was conducted at the PACE clinic and four headspace centres (Sunshine, Werribee, Glenroy, Craigieburn) located in Metropolitan Melbourne. The Australian headspace system is a nationwide ‘one stop shop’ universal access model for young people with emerging mental health issues (McGorry et al., 2007; McGorry, 2007; McGorry, Trethowan, & Rickwood, 2019; McGorry, Goldstone, Parker, Rickwood, & Hickie, 2014). The study was approved by the Melbourne Health Human Research Ethics Committee and the trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12616000098437) and clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02751632). Informed consent was obtained from participants prior to study commencement. For participants under the age of 18, consent was also obtained from their parent/guardian.

2.2. Participants

Young people seeking help at the recruitment clinics were eligible for participation if all the following criteria were met: (i) age between 12-25; (ii) ability to speak adequate English; (iii) ability to provide informed consent; and (iv) meeting UHR criteria1. Exclusion criteria were: (i) past history of a psychotic episode of one week or longer; (ii) attenuated psychotic symptoms only present during acute intoxication; (iii) organic brain disease known to cause psychotic symptoms; (iv) any metabolic, endocrine or other physical illness; (v) diagnosis of a serious developmental disorder; (vi) documented history of developmental delay or intellectual disability. Participants on current antidepressant or antipsychotic medication were assessed for rationale of prescription and excluded if needing ongoing prescription. Young people were screened using a standardized clinical assessment and the Prodromal Questionnaire-16 (PQ-16). Those who scored 6 and above on the PQ-16 or who had a family history of psychotic disorder were identified by a Research Assistant (RA). The RA would then approach and consent the young person (as well as parent or guardian if they were under 18). To ensure that the young person satisfactorily understood the consent form and what was expected of them, the RA would ask them to repeat important details back to them in their own words. They would then conduct a thorough clinical assessment to establish if study entry criteria were met. UHR status was determined using the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS), Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS), SCID-II Schizotypal PD and Family History Index (FHI).

2.3. Measures

In addition to background demographic information and medical history, the following clinical measures were administered at baseline:

Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-5 (SCID-5)(First, Williams, Karg, & Spitzer, 2015).

The SCID-5 is a semi structured interview guide for making the major DSM-5 diagnoses according to the classification and diagnostic criteria of the American Psychiatric Association (2013).

Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS)(Yung et al., 2005).

The CAARMS is a semi-structured assessment tool to identify help-seeking young people who are at ultra high risk (UHR) of developing psychosis. CAARMS has subscales for disorders of thought content, non-bizarre ideas, perceptual abnormalities and disorganised speech, which receive a global ‘severity’ rating and a frequency rating. The severity score ranges from 0 (‘never, absent’) to 6 (‘psychotic and severe); the frequency score ranges from 0 (absent) to 6 (continuous).

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)(Overall & Gorham, 1962; Ventura et al., 1993).

The BPRS is a clinician-rated scale to measure psychiatric symptoms. It consists of 24 items rated on a continuum from not present (1) to extremely severe (7), with a maximum score of 168.

Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)(Andreasen, 1982).

The SANS is a clinician-rated 20-item scale which globally evaluates affective flattening, anhedonia-asociality, attention, alogia, and avolition-apathy. To enhance reliability, these symptoms feature a general description and each domain is divided into observable behaviours (e.g., lack of vocal inflections, physical anergia) and measured on a 6-point scale (from “none” to “severe”).

Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)(Montgomery & Asberg, 1979).

The MADRS is a ten-item (scored 0 to 6) diagnostic questionnaire used to measure the severity of depressive episodes. A higher score indicates more severe depression, with a maximum score of 60. The following cut-off points have been published: symptoms absent (0-6); mild depression (7-19); moderate depression (20-34); severe depression (> 34).

Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST)(WHO ASSIST Working Group, 2002).

The ASSIST was designed to detect and manage substance use and related problems in primary and general medical care settings and consists of eight questions covering tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine-type stimulants (including ecstasy) inhalants, sedatives, hallucinogens, opioids and 'other drugs'. A risk score is provided for each substance, and scores are grouped into 'low risk' (alcohol: 0-10; other substances: 0-3), 'moderate risk' (alcohol: 11-26; other substances 4-26) or 'high risk'(alcohol: >26; other substances: > 26).

Davos Assessment of Cognitive Biases Scale (DACOBS)(van der Gaag, Schutz, et al., 2013).

The DACOBS is a 42-item self-report instrument used to measure cognitive biases specific to positive symptoms of psychosis. In completing the DACOBS, the individual is required to indicate whether they agree or disagree with the statement presented considering the previous two weeks. Each item is scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 'strongly agree' to 'strongly disagree'. There are seven subscales: jumping to conclusions bias; cognitive inflexibility bias; attention to threat bias; external attribution bias; social cognition problems; subjective cognitive problems; and safety behaviours.

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)(Bernstein et al., 2003).

The CTQ is a 28-item retrospective, self-report measure of childhood abuse and neglect. It has five subscales: physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, and physical and emotional neglect. The total score for each subscale ranges from 5 to 25. The higher the score, the more maltreatment is being reported.

Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS)(Goldman, Skodol, & Lave, 1992).

SOFAS is a numeric scale (1 through 100) used to rate subjectively the social, occupational, and psychological functioning. The SOFAS focuses exclusively on the individual's level of social and occupational functioning and is not directly influenced by the overall severity of the individual's clinical symptoms. A higher score indicates higher functioning.

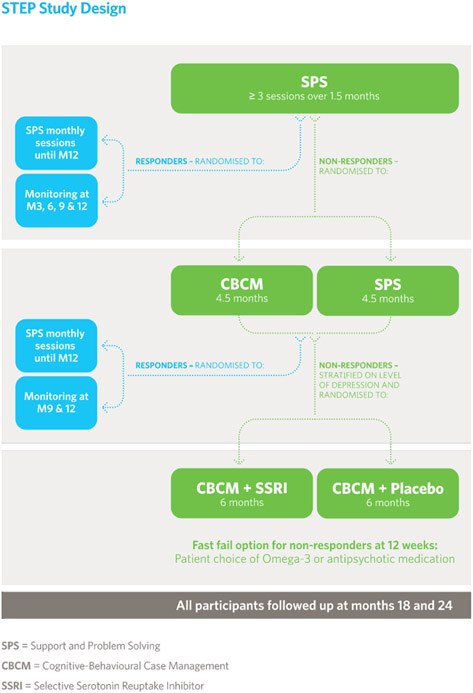

2.4. Study Design

This was a sequential multiple assignment randomised trial (SMART) with three treatment stages plus a fast-fail option (detailed below and in Figure 1), totalling a 12-month intervention phase and a 24-month follow-up phase. Progression through the stages was determined by response versus non-response (Nelson, Amminger, Yuen, Wallis, et al., 2018). Recruitment commenced in April 2016, with all sites operational in September 2016, and ceased in January 2019. The majority of clinical assessments took place at the recruitment clinics, while in some cases the assessments took place at the participant’s choice of location (e.g., at their home) or via the phone/videocall.

Figure 1.

Staged Treatment in Early Psychosis (STEP) study design.

Treatment stages

There were three treatment stages with one or two treatment arms, plus a fast-fail option: (1) Support and problem solving (SPS) alone, (2) SPS versus cognitive behavioural case management (CBCM2); (3) antidepressant versus placebo. Within the last step, there was a fast-fail option. These steps are outlined below. ‘Response’ was defined using the CAARMS (global rating and frequency score < 3 on all positive symptom scales over the past 2 weeks) and SOFAS (at least a 5-point improvement compared with baseline or at least a score of 70). Non-response was defined as not meeting the response criteria. The definition of response was set at a relatively high threshold, as the goal of treatment in our view should be substantial recovery or full remission (including both symptoms and functioning) not merely a modest response (Figure 1).

Step 1:

Single-arm treatment consisting of SPS (6 weeks). All included participants went through this first stage of treatment which was not randomised and therefore not blinded. After this initial stage, non-responders were randomised to Step 2. Responders (during assessments at both week 4 & 6) were randomised to either SPS (monthly sessions) or monitoring only (3 monthly intervals) to assess response maintenance until the end of the intervention period.

Step 2:

Double arm treatment consisting of CBCM vs SPS (20 weeks). This was a single-blind treatment stage, i.e., assessors were unaware of the participant’s treatment allocation. At the end of stage 2, non-responders were randomized (stratified by depression as rated by the MADRS total score <21 or ≥21) to Step 3. Responders (week 12 & 24) were randomized to either SPS (monthly sessions) or monitoring only (at 3 monthly intervals) to assess response sustainment until the end of the intervention and follow up period.

Step 3:

Double arm treatment consisting of antidepressant vs placebo in addition to CBCM (26 weeks). This was a double-blind treatment stage, i.e., both assessors and participants were blind to treatment allocation.

Fast fail:

There was a ‘fast fail’ option within step 3 which facilitated a treatment intensification for participants not responding after 12 weeks. In this fast-fail option, participants were offered (a) an increase in dosage of antidepressant/placebo, (b) the addition of omega-3 fatty acids or (c) low-dose antipsychotic medication. The choice was made via a collaborative and shared-decision-making approach.

All participants were closely monitored for adverse events and concomitant medication use (medication for medical conditions and intermittent benzodiazepines) throughout the study. Over the follow-up period (year 2), treatment was not controlled – participants were referred on for further treatment on an ‘as needs’ basis.

For more information regarding the interventions, as well as definition of responders and non-responders, please see Nelson et al. (2018).

2.5. Analysis

This paper reports descriptive statistics on the baseline clinical characteristics of the cohort in terms of demographics, diagnosis, symptomatic, functional, cognitive bias and exposure measures (mean, standard deviation, and frequencies) and participant recruitment flow.

3. RESULTS

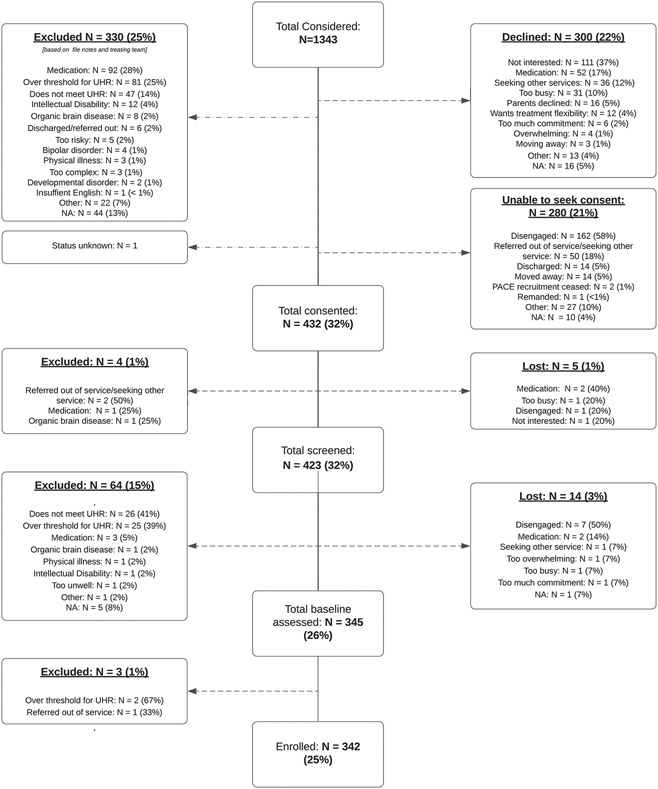

3.1. Participants and participant recruitment flow

A flowchart detailing recruitment flow up until point of enrolment is presented in Figure 2. In total, 1343 help-seeking young people were considered for the study. Of these, 330 (25%) were deemed ineligible based on file notes and discussion with the treating team (for details please see below and the flowchart in Figure 2); 580 (43%) declined participation or the research assistants were unable to seek consent; and 432 (32%) were consented to the study. After the screening and baseline assessments, a total of 342 young people (25% of those considered) were formally enrolled into the STEP study (Figure 2). The most common reason for excluding an individual based on file notes and discussion with the treating team (N = 92) was medication-related: individuals were already prescribed antidepressant medication for a specific and recognised indication and, after review with the study psychiatrist, it was deemed unreasonable to stop the treatment in order to participate in the study. The second most common reason for excluding an individual based on file notes and discussion with the treating team (N = 81) was being over-threshold for UHR (e.g., meeting criteria for a first episode of psychosis currently or in the past) (Figure 2). Most young people who declined participation did so because they were not interested in taking part in this particular study or in participating in research studies generally (N = 111). The second most common reason for declining was medication-related (N = 52): the young person did not wish to participate in a trial involving medication or was already prescribed antidepressant medication and did not wish to discontinue if presented with the option.

Figure 2.

STEP study recruitment flow up until enrolment. Please note, ‘exclusion due to medication’ refers to participants who were already prescribed antidepressant medication and, after review with the study psychiatrist, it was deemed unreasonable to discontinue the treatment. On the other hand, ‘declining due to medication’ refers to either (1) participants who were already prescribed an antidepressant and given the option to discontinue (if reasonable from a clinical point of view) but declined; or (2) the participant was not prescribed antidepressants but declined because they did not wish to participate in a trial involving antidepressant medication.

Disengagement (N = 162) and referral out of service/seeking other service (N = 50) were the most common reasons that no consent could be sought from the young person.

3.2. Demographics, symptomatic/functional profile and other characteristics

The mean age of the 342 enrolled participants was 17.7 years (range 12 to 25) and 58% were female (sex assigned at birth). The majority of the sample was born in Australia (89%), living with their families (78%) and currently in education (72%). Further details regarding the baseline demographic characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics (N=342)

| Category | Attribute | Mean/Count | ±SD or % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 17.7 (12-25) | 3.1 | |

| Gender | Female | 198 | 57.9 |

| Male | 144 | 42.1 | |

| Region of Birth | Australia | 305 | 89.2 |

| Asia | 15 | 4.4 | |

| Europe | 8 | 2.3 | |

| New Zealand | 5 | 1.5 | |

| Other | 9 | 2.6 | |

| Current Accommodation | House/flat with family of origin | 268 | 78.4 |

| Rented room/flat/house | 51 | 14.9 | |

| Owned flat/house | 4 | 1.2 | |

| Other | 17 | 5.0 | |

| Missing | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Current Relationship status | Single/never married | 232 | 67.8 |

| Partnered (3 months to 2 years) | 60 | 17.5 | |

| Partnered (< 3months) | 24 | 7.0 | |

| Married/de facto | 19 | 5.6 | |

| Separated/divorced | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Other | 5 | 1.5 | |

| Currently in education | No | 95 | 27.8 |

| Yes | 245 | 71.6 | |

| Missing | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Highest level of education 1 | Primary school | 2 | 0.6 |

| Year 7-10 | 160 | 46.8 | |

| Year 11-12 | 101 | 29.5 | |

| TAFE | 30 | 8.8 | |

| University undergraduate | 33 | 9.6 | |

| University postgraduate | 4 | 1.2 | |

| Other | 10 | 2.9 | |

| Missing | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Current Employment | Unemployed | 218 | 63.7 |

| Casual paid employment | 70 | 20.5 | |

| Part-time paid employment | 27 | 7.9 | |

| Full-time paid employment | 12 | 3.5 | |

| Casual unpaid employment | 8 | 2.3 | |

| Part-time unpaid employment | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Missing | 5 | 1.5 |

Completed or currently enrolled

As detailed in Table 2, the majority (87%) of the enrolled sample was diagnosed with a non-psychotic DSM-5 diagnosis, mainly mood and anxiety disorders (>60%, see Table 2). The sample displayed symptoms comparable with a moderate illness as indicated by the global BPRS scores (Leucht et al., 2005) and moderate difficulty in social, occupational and school functioning as indicated by SOFAS scores (Table 2). The MADRS indicated a moderate level of depression. Negative symptoms, as measured by the SANS, were comparable to other UHR samples (McGorry et al., 2017; McHugh et al., 2018). The WHO ASSIST substance use score revealed a moderate level of tobacco and cannabis use, and low level for alcohol. Further details are displayed in Table 2. As shown in Table 3, the sample reported a history of severe levels of emotional and physical abuse, moderate levels of sexual abuse, none or low levels of emotional neglect, and moderate levels of physical neglect, as measured by the CTQ. The DACOBS total score indicated cognitive problems and cognitive biases higher than what has previously been reported in a schizophrenia spectrum patient sample (van der Gaag, Schutz, et al., 2013). This seems to have been largely driven by the cognitive limitation subscales (social cognition problems: above average; subjective cognition problems: above average) and behaviour subscales (safety behaviour: above average) and less so by the cognitive bias subscales (jumping to conclusions: below average; belief inflexibility bias: average; attention for threat bias: average; external attribution bias: average).

Table 2.

Diagnostic, symptomatic and functional characteristics

| Category | N | Attribute | Mean/Count | ±SD or % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current diagnosis | 342 | No diagnosis | 45 | 13.2 |

| Anxiety, dissociative, stress-related, somatoform and other nonpsychotic mental disorders | 225 | 65.8 | ||

| Mood [affective] disorders | 207 | 60.5 | ||

| Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use | 54 | 15.8 | ||

| Behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors | 30 | 8.8 | ||

| Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence | 26 | 7.6 | ||

| Borderline personality disorder | 17 | 5.0 | ||

| Pervasive and specific developmental disorders | 7 | 2.0 | ||

| Schizotypal disorder | 6 | 1.8 | ||

| Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| Other | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| Missing | 15 | 4.4 | ||

| CAARMS severity | 342 | Unusual thought content | 2.6 (0-5) | 1.8 |

| Non-bizarre ideas | 2.9 (0-6) | 1.7 | ||

| Perceptual abnormalities | 3.1 (0-5) | 1.5 | ||

| Disorganised speech | 1.7 (0-5) | 1.2 | ||

| CAARMS frequency | 339 | Unusual thought content | 2.4 (0-6) | 1.7 |

| 341 | Non-bizarre ideas | 3.0 (0-6) | 1.7 | |

| 340 | Perceptual abnormalities | 2.6 (0-6) | 1.4 | |

| 341 | Disorganised speech | 2.6 (0-6) | 1.9 | |

| CAARMS Composite † | 341 | Attenutated positive psychotic severity score | 34.6 (0-80) | 16.8 |

| Other symptoms | 340 | General psychopathology (BPRS) | 44.6 (26-76) | 8.7 |

| 341 | Negative symptoms (SANS) | 18.4 (0-57) | 11.2 | |

| 337 | Depressive symptoms (MADRS) | 23.5 (0-50) | 9.9 | |

| Functioning | 342 | Social and Occupational Functioning (SOFAS) | 56.7 (31-93) | 11.6 |

| Substance use (ASSIST) | 332 | Tobacco | 7.0 (0-38) | 9.6 |

| 333 | Alcohol | 5.9 (0-35) | 7.6 | |

| 334 | Cannabis | 6.3 (0-39) | 10.6 | |

| 334 | Amphetamine | 1.9 (0-37) | 5.6 | |

| 334 | Sedatives | 0.9 (0-29) | 3.5 | |

| 333 | Hallucinogens | 0.9 (0-29) | 3.2 | |

| 334 | Inhalants | 0.6 (0-27) | 2.7 | |

| 333 | Cocaine | 0.5 (0-15) | 1.8 | |

| 335 | Opioids | 0.3 (0-19) | 1.6 | |

| 335 | Other | 0.2 (0-39) | 2.4 |

CAARMS = Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States; BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; SANS = Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; MADRS = Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; SOFAS = Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale; ASSIST = Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test

Composite score according to Morrison et al. (2012)

Table 3.

Other baseline characteristics

| Category | N | Attribute | Mean/Count | ±SD or % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive problems and bias (DACOBS) | 314 | Cognitive Bias Total | 169.7 (85-251) | 31.3 |

| 327 | Jumping to conclusions bias | 23.1 (8-38) | 5.5 | |

| 315 | Belief inflexibility bias | 20.6 (6-37) | 6.2 | |

| 327 | Attention to threat bias | 27.4 (10-42) | 6.4 | |

| 314 | External attribution bias | 23.4 (6-41) | 6.8 | |

| 327 | Social cognition problems | 27.6 (9-42) | 6.6 | |

| 315 | Subjective cognitive problems | 29.0 (9-42) | 6.3 | |

| 315 | Safety behaviour | 18.2 (6-39) | 6.9 | |

| Trauma (CTQ) | 329 | CTQ total | 61.2 (43-111) | 13.5 |

| 330 | Emotional Abuse | 17.4 (10-25) | 4.6 | |

| 330 | Physical Abuse | 12.9 (10-25) | 3.8 | |

| 314 | Sexual Abuse | 11.7 (10-25) | 3.7 | |

| 330 | Emotional Neglect | 8.8 (5-20) | 3.5 | |

| 330 | Physical Neglect | 10.6 (8-22) | 2.9 | |

| UHR subgroups | 342 | Trait vulnerability | 9 | 2.6 |

| 342 | APS | 292 | 85.4 | |

| 342 | Trait + APS group | 32 | 9.4 | |

| 342 | BLIPS group | 1 | 0.3 | |

| 342 | APS + BLIPS | 4 | 1.2 | |

| 342 | Trait + APS + BLIPS group | 4 | 1.2 |

DACOBS = Davos Assessment of Cognitive Biases Scale; CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; APS = Attenuated Positive Psychotic Symptoms; BLIPS = Brief Limited Intermittent Psychotic symptoms

With regard to UHR subgroups, the vast majority of participants (N = 292, 85.4%) met criteria for the attenuated positive psychotic symptoms (APS) group; N = 32 (9.4%) met criteria for both APS and trait vulnerability groups. Table 3 provides a full break down of UHR subgroups.

4. DISCUSSION

This is the first SMART in UHR individuals evaluating three steps of sequential treatment with increasingly intensive interventions. Different interventions were provided depending on the clinical response at each step, with the view to establishing a stepwise approach in the provision of care to UHR individuals.

Of the 1343 help-seeking young people considered for this study over the recruitment period, 342 (25%) were enrolled. One of the most frequent reasons for participants to decline participation or to be excluded was related to current medication use. Some young people were already prescribed antidepressant medication for a specific and recognised indication and, after the review with the study psychiatrist, it was deemed unreasonable to stop the treatment in order to participate in the study. Other participants did not want to stop their prescribed medication before enrolment or did not want to take the chance of being in the medication arm of the study. Only 22% of potential participants actively declined participation, which is lower than in RCT’s involving antipsychotics in this population. For example, in an RCT in the UHR population involving risperidone, only one third of potential participants agreed to be involved in the study (Phillips et al., 2009). This result underlines the apparent patients’ acceptability of – and openness to - sequential treatment trials. It is comparable to higher consent rates involving CBT or omega-3 fatty acids, which indicates that RCT’s involving psychotherapy or nutraceuticals have higher consent rates than RCT’s involving antipsychotics (Addington, Marshall, & French, 2012; McGorry et al., 2009).

In terms of baseline diagnostic and symptomatic characteristics, the enrolled STEP study participants are comparable to other UHR samples previously recruited from PACE and headspace centres. As in other studies, the vast majority of this sample had at least one DSM-5 diagnosis, mostly mood and anxiety disorders. Compared to the symptomatic and functional profile at baseline of the NEURAPRO sample (N=304 - a recent RCT in UHR testing the effectiveness of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids) (Nelson, Amminger, Yuen, Markulev, et al., 2018) the STEP sample shows slightly higher levels of general psychopathology, negative and depressive symptoms, but also slightly higher functioning. Moreover, in line with other UHR cohorts, they present with a significant symptomatic and functional impairment, and high level of childhood trauma. This supports the clear need for care in the UHR group and that treatment is appropriate and fully justified (Fusar-Poli et al., 2013). Furthermore, a high level of baseline general psychopathology seems to be an important predictor of poor outcomes broadly defined in the UHR population and therefore an important element to respond to in this population (Polari et al., 2020). Regarding cognitive problems and biases, the scores of the present UHR sample were comparable to those with later stage schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Future papers from this cohort will report on whether these subjective cognitive problems and cognitive biases correlated with symptom severity and functioning and whether they modulated treatment response.

Clinical implications

The results presented in this paper demonstrate that it is feasible to rapidly recruit a large sample of UHR individuals from a metropolitan catchment area. Furthermore, it became apparent that these individuals are significantly unwell and manifest high rates of anxiety/depression and prescription of antidepressants. A non-negligible portion of potential participants declined participation as they were already prescribed an antidepressant and did not want to titrate off when this was proposed by their clinician (if indicated), suggesting either that a) participants prioritised medication over psychological interventions or b) prioritised maintaining existing treatment over an experimental treatment, or both. This highlights the need for education of General Practioners and other health care providers about the value of effective psychological interventions, which should be offered to most individuals before antidepressants and other psychopharmacological agents are prescribed to young people (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2014, 2016)). It also indicates the need for the provision of information about the UHR clinical phenotype to health care providers as well as health care consumers , especially since UHR status is a marker of clinical severity and risk for adverse transdiagnostic outcomes (Hazan et al., 2020) and poorer prognosis in young people with anxiety and depression (Kelleher et al., 2012).

Limitations

A substantial proportion of UHR participants declined or were excluded because they were already prescribed an antidepressant medication. This may raise questions about the wider applicability of this particular staged approach to treatment, i.e., is it feasible to titrate UHR individuals off medication prior to starting a stepped treatment approach? Notwithstanding this issue, it is necessary to empirically test the clinical efficacy and utility of antidepressants in this clinical group, particularly given that the present data and data from previous studies indicate the widespread prescription of these medications for the UHR group without a sufficient evidence base to date.

5. Conclusion

The relatively low rate of declining consent indicates the acceptability of the trial’s sequential treatment approach in this clinical population, which models standard sequential clinical practice of moving from benign psychosocial intervention to more specific and intensive treatment. It also demonstrates, in line with other studies in UHR individuals, a significant level of clinical morbidity and functional impairment, confirming the clear need for stepwise and expert treatment and care. Subsequent papers will report on participant flow through the staged treatment approach and clinical and functional outcomes in response to the trial treatments.

6. Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute Of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 1U01MH105258-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

PDM reported receiving grant funding from National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression and unrestricted research funding from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Pfizer, and Novartis, as well as honoraria for educational activities with AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, and the Lundbeck Institute. TN is co-founder and share holder in Safari Health, Inc. No other conflict of interests was reported.

The UHR criteria are assessed using the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS, Yung et al., 2005). Young people at UHR are identified by one or more of the following characteristics: 1) Attenuated Psychotic Symptoms (APS) — young people who have experienced subthreshold, attenuated forms of positive psychotic symptoms during the past year, 2) Brief Limited Intermittent Psychotic Symptoms (BLIPS) — young people who have experienced episodes of frank psychotic symptoms that have not lasted longer than a week and have spontaneously abated, and 3) Trait and State Risk Factor (Trait) — individuals who have a first-degree relative with a psychotic disorder or who have a schizotypal personality disorder in addition to a significant decrease in functioning, or chronic low functioning, during the previous year.

Cognitive behavioural case management (CBCM) is cognitive behavioural therapy for UHR delivered within a case management framework, i.e. the same person delivers psychotherapeutic aspects of CBT, as developed for this clinical population, and provides practical case management support, such as liaisong with schools, family, accommodation support services.

8. REFERENCES

- Ising HK, Kraan TC, Rietdijk J, Dragt S, Klaassen RMC, Boonstra N, Nieman DH, Willebrands-Mendrik M, van den Berg DPG, Linszen DH, Wunderink L, Veling W, Smit F, & van der Gaag M (2016). Four-year follow-up of cognitive behavioral therapy in persons at ultra-high risk for developing psychosis: The Dutch Early Detection Intervention Evaluation (EDIE-NL) Trial. Schizophr Bull, 42(5), 1243–1252. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, O'Brien MP, Schlosser DA, Addington J, Candan KA, Marshall C, Domingues I, Walsh BC, Zinberg JL, De Silva SD, Friedman-Yakoobian M, & Cannon TD (2014). Family-focused treatment for adolescents and young adults at high risk for psychosis: Results of a randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 53(8), 848–858. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison AP, French P, Stewart SLK, Birchwood M, Fowler D, Gumley AI, Jones PB, Bentall RP, Lewis SW, Murray GK, Patterson P, Brunet K, Conroy J, Parker S, Reilly T, Byrne R, Davies LM, & Dunn G (2012). Early detection and intervention evaluation for people at risk of psychosis: Multisite randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 344, e2233. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stain HJ, Bucci S, Baker AL, Carr V, Emsley R, Halpin S, Lewin T, Schall U, Clarke V, Crittenden K, & Startup M (2016). A randomised controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy versus non-directive reflective listening for young people at ultra high risk of developing psychosis: The detection and evaluation of psychological therapy (DEPTh) trial. Schizophr Res, 176(2-3), 212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Gaag M, Nieman DH, Rietdijk J, Dragt S, Ising HK, Klaassen RM, Koeter M, Cuijpers P, Wunderink L, & Linszen DH (2012). Cognitive behavioral therapy for subjects at ultrahigh risk for developing psychosis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Schizophr Bull, 38(6), 1180–1188. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins D, Addington J, Miller T, Woods SW, Hawkins KA, Hoffman RE, Preda A, Epstein I, Addington D, Lindborg S, Trzaskoma Q, Tohen M, & Breier A (2006). Randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry, 163(5), 790–799. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Nelson B, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, Francey SM, Thampi A, Berger GE, Amminger GP, Simmons MB, Kelly D, Dip G, Thompson AD, & Yung AR (2013). Randomized controlled trial of interventions for young people at ultra-high risk of psychosis: Twelve-month outcome. J Clin Psychiatry, 74(4), 349–356. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods S, Saksa J, Compton M, Daley M, Rajarethinam R, Graham K, Breitborde N, Cahill J, Srihari V, Perkins D, Bearden C, Cannon T, Walker E, & McGlashan T (2017). Effects of ziprasidone versus placebo in patients at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Bull, 43(Suppl 1), S58–S58. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx021.150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amminger GP, Schafer MR, Papageorgiou K, Klier CM, Cotton SM, Harrigan SM, Mackinnon A, McGorry PD, & Berger GE (2010). Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 67(2), 146–154. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantrowitz JT, Woods SW, Petkova E, Cornblatt B, Corcoran CM, Chen H, Silipo G, & Javitt DC (2015). D-serine for the treatment of negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk of schizophrenia: A pilot, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised parallel group mechanistic proof-of-concept trial. Lancet Psychiatry, 2(5), 403–412. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00098-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson B, Amminger GP, Yuen HP, Markulev C, Lavoie S, Schäfer MR, Hartmann JA, Mossaheb N, Schlögelhofer M, Smesny S, Hickie IB, Berger G, Chen EYH, de Haan L, Nieman DH, Nordentoft M, Riecher-Rössler A, Verma S, Thompson A, Yung AR, & McGorry PD (2018). NEURAPRO: A multi-centre RCT of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids versus placebo in young people at ultra-high risk of psychotic disorders—medium-term follow-up and clinical course. NPJ Schizophr, 4(1), 11. doi: 10.1038/s41537-018-0052-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SW, Walsh BC, Hawkins KA, Miller TJ, Saksa JR, D'Souza DC, Pearlson GD, Javitt DC, McGlashan TH, & Krystal JH (2013). Glycine treatment of the risk syndrome for psychosis: Report of two pilot studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol, 23(8), 931–940. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preti A, & Cella M (2010). Randomized-controlled trials in people at ultra high risk of psychosis: A review of treatment effectiveness. Schizophr Res, 123(1), 30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford MR, Jackson H, Mayo-Wilson E, Morrison AP, & Kendall T (2013). Early interventions to prevent psychosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 346, f185. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Gaag M, Smit F, Bechdolf A, French P, Linszen DH, Yung AR, McGorry P, & Cuijpers P (2013). Preventing a first episode of psychosis: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled prevention trials of 12 month and longer-term follow-ups. Schizophr Res, 149(1), 56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Mei C, Hartmann J, Yung AR, & Nelson B (2021). Intervention strategies for ultra-high risk for psychosis: Progress in delaying the onset and reducing the impact of first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res, 228, 344–356. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei C, van der Gaag M, Nelson B, Smit F, Yuen HP, Berger M, Krcmar M, French P, Amminger GP, Bechdolf A, Cuijpers P, Yung AR, & McGorry PD (2021). Preventive interventions for individuals at ultra high risk for psychosis: An updated and extended meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev, 86, 102005. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies C, Cipriani A, Ioannidis JPA, Radua J, Stahl D, Provenzani U, McGuire P, & Fusar-Poli P (2018). Lack of evidence to favor specific preventive interventions in psychosis: A network meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 17(2), 196–209. doi: 10.1002/wps.20526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies C, Radua J, Cipriani A, Stahl D, Provenzani U, McGuire P, & Fusar-Poli P (2018). Efficacy and acceptability of interventions for attenuated positive psychotic symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis: A network meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry, 9, 187. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoe DJ, Farris MS, Townes P, & Addington J (2019). Attenuated psychotic symptom interventions in youth at risk of psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Early Interv Psychiatry, 13(1), 3–17. doi: 10.1111/eip.12677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Cappucciati M, Borgwardt S, Woods SW, Addington J, Nelson B, Nieman DH, Stahl DR, Rutigliano G, Riecher-Rossler A, Simon AE, Mizuno M, Lee TY, Kwon JS, Lam MM, Perez J, Keri S, Amminger P, Metzler S, Kawohl W, Rossler W, Lee J, Labad J, Ziermans T, An SK, Liu CC, Woodberry KA, Braham A, Corcoran C, McGorry P, Yung AR, & McGuire PK (2016). Heterogeneity of Psychosis Risk Within Individuals at Clinical High Risk: A Meta-analytical Stratification. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(2), 113–120. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson B, & Yung AR (2009). Psychotic-like experiences as overdetermined phenomena: when do they increase risk for psychotic disorder? Schizophr Res, 108(1-3), 303–304. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Os J, & Guloksuz S (2017). A critique of the "ultra-high risk" and "transition" paradigm. World Psychiatry, 16(2), 200–206. doi: 10.1002/wps.20423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA (2005). An experimental design for the development of adaptive treatment strategies. Stat Med, 24(10), 1455–1481. doi: 10.1002/sim.2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Hickie IB, Yung AR, Pantelis C, & Jackson HJ (2006). Clinical staging of psychiatric disorders: a heuristic framework for choosing earlier, safer and more effective interventions. Aust N Z J Psychiatry, 40(8), 616–622. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01860.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Leboyer M, Hickie I, Berk M, Kapczinski F, Frank E, Kupfer D, & McGorry P (2013). Clinical staging in psychiatry: a cross-cutting model of diagnosis with heuristic and practical value. Br J Psychiatry, 202(4), 243–245. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.110858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, & Hickie IB (Eds.). (2019). Clinical Staging in Psychiatry. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mei C, McGorry PD, & Hickie IB (2019). Clinical Staging and Its Potential to Enhance Mental Health Care. In Hickie IB & McGorry PD (Eds.), Clinical Staging in Psychiatry: Making Diagnosis Work for Research and Treatment (pp. 12–33). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cross SP, Hermens DF, Scott EM, Ottavio A, McGorry PD, & Hickie IB (2014). A clinical staging model for early intervention youth mental health services. Psychiatr Serv, 65(7), 939–943. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickie IB, Scott EM, Hermens DF, Naismith SL, Guastella AJ, Kaur M, Sidis A, Whitwell B, Glozier N, Davenport T, Pantelis C, Wood SJ, & McGorry PD (2013). Applying clinical staging to young people who present for mental health care. Early Interv Psychiatry, 7(1), 31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2012.00366.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson B, Amminger GP, Yuen HP, Wallis N, M JK, Dixon L, Carter C, Loewy R, Niendam TA, Shumway M, Morris S, Blasioli J, & McGorry PD (2018). Staged Treatment in Early Psychosis: A sequential multiple assignment randomised trial of interventions for ultra high risk of psychosis patients. Early Interv Psychiatry, 12(3), 292–306. doi: 10.1111/eip.12459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajnakina O, David AS, & Murray RM (2018). 'At risk mental state' clinics for psychosis - an idea whose time has come - and gone! Psychol Med, 1–6. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718003859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Palombini E, Davies C, Oliver D, Bonoldi I, Ramella-Cravaro V, & McGuire P (2018). Why transition risk to psychosis is not declining at the OASIS ultra high risk service: The hidden role of stable pretest risk enrichment. Schizophr Res, 192, 385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter WT (2018). Clinical High Risk Controversies and Challenge for the Experts. Schizophr Bull, 44(2), 223–225. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guloksuz S, & van Os J (2018). Need for evidence-based early intervention programmes: a public health perspective. Evid Based Ment Health, 21(4), 128–130. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2018-300030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, & Mei C (2020). Why do psychiatrists doubt the value of early intervention? The power of illusion. Australas Psychiatry, 28(3), 331–334. doi: 10.1177/1039856220924323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, & Nelson B (2020). Clinical High Risk for Psychosis-Not Seeing the Trees for the Wood. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(7), 559–560. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, Wood SJ, Malla A, Nelson B, McGorry P, & Shah J (2021). The reality of at risk mental state services: a response to recent criticisms. Psychol Med, 51(2), 212–218. doi: 10.1017/S003329171900299X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt DL, & Mehta C (2016). Adaptive Designs for Clinical Trials. N Engl J Med, 375(1), 65–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1510061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bothwell LE, Avorn J, Khan NF, & Kesselheim AS (2018). Adaptive design clinical trials: a review of the literature and ClinicalTrials.gov. BMJ Open, 8(2), e018320. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auyeung SF, Long Q, Royster EB, Murthy S, McNutt MD, Lawson D, Miller A, Manatunga A, & Musselman DL (2009). Sequential multiple-assignment randomized trial design of neurobehavioral treatment for patients with metastatic malignant melanoma undergoing high-dose interferon-alpha therapy. Clin Trials, 6(5), 480–490. doi: 10.1177/1740774509344633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortreed SM, & Moodie EE (2012). Estimating the optimal dynamic antipsychotic treatment regime: Evidence from the sequential multiple assignment randomized CATIE Schizophrenia Study. J R Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat, 61(4), 577–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9876.2012.01041.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, Edinger JD, Beaulieu-Bonneau S, Ivers H, Krystal AD, Guay B, Belanger L, Cartwright A, Simmons B, Lamy M, & Busby M (2020). Effectiveness of Sequential Psychological and Medication Therapies for Insomnia Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne AM, Almirall D, Eisenberg D, Waxmonsky J, Goodrich DE, Fortney JC, Kirchner JE, Solberg LI, Main D, Bauer MS, Kyle J, Murphy SA, Nord KM, & Thomas MR (2014). Protocol: Adaptive Implementation of Effective Programs Trial (ADEPT): cluster randomized SMART trial comparing a standard versus enhanced implementation strategy to improve outcomes of a mood disorders program. Implement Sci, 9, 132. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0132-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Gaag M, van den Berg D, & Ising H (2019). CBT in the prevention of psychosis and other severe mental disorders in patients with an at risk mental state: A review and proposed next steps. Schizophr Res, 203, 88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Smith CW, Olsen R, Auther AM, Nakayama E, Lesser ML, Tai JY, Shah MR, Foley CA, Kane JM, & Correll CU (2007). Can antidepressants be used to treat the schizophrenia prodrome? Results of a prospective, naturalistic treatment study of adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry, 68(4), 546–557. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Frascarelli M, Valmaggia L, Byrne M, Stahl D, Rocchetti M, Codjoe L, Weinberg L, Tognin S, Xenaki L, & McGuire P (2015). Antidepressant, antipsychotic and psychological interventions in subjects at high clinical risk for psychosis: OASIS 6-year naturalistic study. Psychol Med, 45(6), 1327–1339. doi: 10.1017/S003329171400244X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Tanti C, Stokes R, Hickie IB, Carnell K, Littlefield LK, & Moran J (2007). headspace: Australia's National Youth Mental Health Foundation--where young minds come first. Med J Aust, 187(S7), S68–70. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01342.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD (2007). The specialist youth mental health model: strengthening the weakest link in the public mental health system. Med J Aust, 187(S7), S53–56. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01338.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry P, Trethowan J, & Rickwood D (2019). Creating headspace for integrated youth mental health care. World Psychiatry, 18(2), 140–141. doi: 10.1002/wps.20619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Goldstone SD, Parker AG, Rickwood DJ, & Hickie IB (2014). Cultures for mental health care of young people: an Australian blueprint for reform. Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 559–568. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00082-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, & Spitzer RL (2015). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5—Research Version (SCID-5 for DSM-5, Research Version; SCID-5-RV). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, Phillips LJ, Kelly D, Dell'Olio M, Francey SM, Cosgrave EM, Killackey E, Stanford C, Godfrey K, & Buckby J (2005). Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry, 39(11-12), 964–971. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01714.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall JE, & Gorham DR (1962). The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports, 10, 799–812. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura J, Lukoff D, Nuechterlein K, Liberman RP, Green M, & Shaner A (1993). Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Expanded version 4.0: Scales anchor points and administration manual. Int J Meth Psychiatr Res, 13, 221–244. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC (1982). Negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Definition and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 39(7), 784–788. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290070020005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery S, & Asberg M (1979). A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry, 134, 382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO ASSIST Working Group. (2002). The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction, 97(9), 1183–1194. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Gaag M, Schutz C, Ten Napel A, Landa Y, Delespaul P, Bak M, Tschacher W, & de Hert M (2013). Development of the Davos assessment of cognitive biases scale (DACOBS). Schizophr Res, 144(1-3), 63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, & Zule W (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl, 27(2), 169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman HH, Skodol AE, & Lave TR (1992). Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry, 149(9), 1148–1156. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Hamann J, Etschel E, & Engel R (2005). Clinical implications of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale scores. Br J Psychiatry, 187, 366–371. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.4.366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Nelson B, Markulev C, Yuen HP, Schafer MR, Mossaheb N, Schlogelhofer M, Smesny S, Hickie IB, Berger GE, Chen EY, de Haan L, Nieman DH, Nordentoft M, Riecher-Rossler A, Verma S, Thompson A, Yung AR, & Amminger GP (2017). Effect of omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Young People at Ultrahigh Risk for Psychotic Disorders: The NEURAPRO Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(1), 19–27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh MJ, McGorry PD, Yuen HP, Hickie IB, Thompson A, de Haan L, Mossaheb N, Smesny S, Lin A, Markulev C, Schloegelhofer M, Wood SJ, Nieman D, Hartmann JA, Nordentoft M, Schafer M, Amminger GP, Yung A, & Nelson B (2018). The Ultra-High-Risk for psychosis groups: Evidence to maintain the status quo. Schizophr Res, 195, 543–548. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LJ, Nelson B, Yuen HP, Francey SM, Simmons M, Stanford C, Ross M, Kelly D, Baker K, Conus P, Amminger P, Trumpler F, Yun Y, Lim M, McNab C, Yung AR, & McGorry PD (2009). Randomized controlled trial of interventions for young people at ultra-high risk of psychosis: study design and baseline characteristics. Aust N Z J Psychiatry, 43(9), 818–829. doi: 10.1080/00048670903107625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Marshall C, & French P (2012). Cognitive behavioral therapy in prodromal psychosis. Curr Pharm Des, 18(4), 558–565. doi: 10.2174/138161212799316082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Nelson B, Amminger GP, Bechdolf A, Francey SM, Berger G, Riecher-Rossler A, Klosterkotter J, Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Nordentoft M, Hickie I, McGuire P, Berk M, Chen EY, Keshavan MS, & Yung AR (2009). Intervention in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a review and future directions. J Clin Psychiatry, 70(9), 1206–1212. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08r04472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S, Bechdolf A, Addington J, Riecher-Rossler A, Schultze-Lutter F, Keshavan M, Wood S, Ruhrmann S, Seidman LJ, Valmaggia L, Cannon T, Velthorst E, De Haan L, Cornblatt B, Bonoldi I, Birchwood M, McGlashan T, Carpenter W, McGorry P, Klosterkotter J, McGuire P, & Yung A (2013). The psychosis high-risk state: a comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(1), 107–120. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polari A, Yuen HP, Amminger P, Berger G, Chen E, deHaan L, Hartmann J, Markulev C, McGorry P, Nieman D, Nordentoft M, Riecher-Rossler A, Smesny S, Stratford J, Verma S, Yung A, Lavoie S, & Nelson B (2020). Prediction of clinical outcomes beyond psychosis in the ultra-high risk for psychosis population. Early Interv Psychiatry. doi: 10.1111/eip.13002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICE. (2014). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management [CG187]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178. [PubMed]

- NICE. (2016). Psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people: recognition and management [CG155]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg155. [PubMed]

- Hazan H, Spelman T, Amminger GP, Hickie I, McGorry PD, Phillips LJ, Purcell R, Wood SJ, Yung AR, & Nelson B (2020). The prognostic significance of attenuated psychotic symptoms in help-seeking youth. Schizophr Res, 215, 277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher I, Keeley H, Corcoran P, Lynch F, Fitzpatrick C, Devlin N, Molloy C, Roddy S, Clarke MC, Harley M, Arseneault L, Wasserman C, Carli V, Sarchiapone M, Hoven C, Wasserman D, & Cannon M (2012). Clinicopathological significance of psychotic experiences in non-psychotic young people: evidence from four population-based studies. Br J Psychiatry, 201(1), 26–32. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.101543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]