Abstract

Objective

To understand the experiences and perceptions of people implementing maternal and/or perinatal death surveillance and response in low- and middle-income countries, and the mechanisms by which this process can achieve its intended outcomes.

Methods

In June 2022, we systematically searched seven databases for qualitative studies of stakeholders implementing maternal and/or perinatal death surveillance and response in low- and middle-income countries. Two reviewers independently screened articles and assessed their quality. We used thematic synthesis to derive descriptive themes and a realist approach to understand the context–mechanism–outcome configurations.

Findings

Fifty-nine studies met the inclusion criteria. Good outcomes (improved quality of care or reduced mortality) were underpinned by a functional action cycle. Mechanisms for effective death surveillance and response included learning, vigilance and implementation of recommendations which motivated further engagement. The key context to enable effective death surveillance and response was a blame-free learning environment with good leadership. Inadequate outcomes (lack of improvement in care and mortality and discontinuation of death surveillance and response) resulted from a vicious cycle of under-reporting, inaccurate data, and inadequate review and recommendations, which led to demotivation and disengagement. Some harmful outcomes were reported, such as inappropriate referrals and worsened staff shortages, which resulted from a fear of negative consequences, including blame, disciplinary action or litigation.

Conclusion

Conditions needed for effective maternal and/or perinatal death surveillance and response include: separation of the process from litigation and disciplinary procedures; comprehensive guidelines and training; adequate resources to implement recommendations; and supportive supervision to enable safe learning.

Résumé

Objectif

Comprendre les expériences et perceptions des individus chargés de mettre en œuvre la surveillance des décès maternels et périnatals et la riposte dans les pays à revenu faible et intermédiaire, ainsi que les mécanismes utilisés pour que ce processus atteigne ses objectifs.

Méthodes

En juin 2022, nous avons analysé systématiquement sept bases de données à la recherche d'études qualitatives sur les intervenants responsables du processus de surveillance des décès maternels et périnatals et de la riposte dans les pays à revenu faible et intermédiaire. Deux réviseurs ont passé séparément les articles en revue afin d'évaluer leur qualité. Nous avons ensuite utilisé une synthèse thématique pour extraire des thèmes descriptifs et une approche réaliste permettant d'identifier les configurations contexte–mécanisme–résultat.

Résultats

Nous avons inclus 59 études correspondant aux critères d'inclusion. Les résultats positifs (amélioration de la qualité des soins ou diminution de la mortalité) reposaient sur un cycle fonctionnel d'actions. Parmi les mécanismes favorisant la surveillance et la riposte contre les décès figuraient une expérience instructive, la vigilance et l'application de recommandations, ce qui motivait les acteurs à participer. Un environnement éducatif dépourvu de culpabilisation et bien dirigé offrait un contexte optimal pour garantir l'efficacité de la surveillance et de la riposte. Au contraire, les résultats insatisfaisants (absence d'amélioration des soins et de la mortalité, interruption du processus de surveillance et de riposte contre les décès) étaient liés à un cercle vicieux fait de sous-déclaration des décès, de renseignements inexacts, mais aussi d'analyses et de recommandations inadéquates, entraînant une démotivation et un manque d'engagement. Certains résultats néfastes ont également été rapportés, tels que des références inappropriées et une aggravation du manque de personnel, suscités par la crainte de conséquences négatives (blâmes, sanctions disciplinaires ou litiges).

Conclusion

Plusieurs conditions sont requises pour assurer une surveillance et une riposte efficaces contre les décès maternels et/ou périnatals: séparer ce processus des procédures disciplinaires et des litiges; proposer un ensemble de formations et de lignes directrices; fournir les ressources nécessaires à la mise en œuvre des recommandations; et enfin, opter pour une supervision constructive, propice à un environnement éducatif sans danger.

Resumen

Objetivo

Comprender las experiencias y percepciones de las personas que implementan la vigilancia y la respuesta a la mortalidad materna o perinatal en los países de ingresos bajos y medios, y los mecanismos por los que este proceso puede alcanzar los resultados previstos.

Métodos

En junio de 2022, se realizaron búsquedas sistemáticas en siete bases de datos para encontrar estudios cualitativos de las partes interesadas que implementan la vigilancia y la respuesta a la mortalidad materna o perinatal en países de ingresos bajos y medios. Dos revisores analizaron de forma independiente los artículos y evaluaron su calidad. Se utilizó la síntesis temática para derivar temas descriptivos y un enfoque realista para comprender las configuraciones de contexto, mecanismo y resultado.

Resultados

Cincuenta y nueve estudios cumplieron los criterios de inclusión. Los resultados satisfactorios (mejora de la calidad de la atención o reducción de la mortalidad) se sustentaron en un ciclo de acción funcional. Los mecanismos para una vigilancia y respuesta eficaces a la mortalidad incluyeron el aprendizaje, la vigilancia y la aplicación de recomendaciones que motivaron un mayor compromiso. El contexto clave para hacer posible una vigilancia y respuesta eficaz a la mortalidad fue un entorno de aprendizaje libre de culpa con un buen liderazgo. Los resultados insuficientes (falta de mejora en la atención y la mortalidad e interrupción de la vigilancia y la respuesta a la mortalidad) fueron el resultado de un círculo vicioso de falta de notificación, datos inexactos y revisión y recomendaciones inadecuadas, que condujeron a la desmotivación y la falta de compromiso. Se notificaron algunos desenlaces perjudiciales, como las derivaciones incorrectas y una mayor falta de personal, que se debieron al miedo a las consecuencias negativas, como la culpa, las medidas disciplinarias o los litigios.

Conclusión

Entre los requisitos necesarios para que la vigilancia y la respuesta a la mortalidad materna o perinatal sean eficaces se encuentran los siguientes: separación del proceso de los litigios y los procedimientos disciplinarios; directrices y formación exhaustivas; recursos adecuados para aplicar las recomendaciones; y una supervisión de apoyo que permita el aprendizaje seguro.

ملخص

الغرض فهم تجارب وتصورات الأشخاص الذين يقومون بمراقبة وفيات الأمهات و/أو وفيات الفترة المحيطة بالولادة، والاستجابة لها في الدول ذات الدخل المنخفض والدخل المتوسط، والآليات التي يمكن لهذه العملية من خلالها تحقيق النتائج المرجوة.

الطريقة في يونيو/حزيران 2022، قمنا بالبحث بشكل منهجي في سبع قواعد بيانات للدراسات النوعية لأصحاب المصلحة الذين يقومون بتنفيذ مراقبة وفيات الأمهات و/أو وفيات الفترة المحيطة بالولادة، والاستجابة لها في الدول ذات الدخل المنخفض والدخل المتوسط. قام اثنان من المراجعين بشكل مستقل بفحص المقالات وتقييم جودتها. وقد استخدمنا التجميع الموضوعي لاشتقاق موضوعات وصفية، وأسلوب واقعي لفهم أوضاع السياق والآلية والنتائج.

النتائج استوفت تسع وخمسون دراسة معايير الاشتمال. كانت النتائج الجيدة (تحسين جودة الرعاية أو انخفاض معدل الوفيات) مدعومة بدورة عمل وظيفية. تضمنت آليات المراقبة الفعالة للوفيات والاستجابة لها، كل من التعلم واليقظة وتنفيذ التوصيات، وهو ما شجّع على مزيد من المشاركة. كان السياق الرئيسي لتمكين المراقبة الفعالة للوفيات والاستجابة لها هو بيئة تعليمية خالية من اللوم مع قيادة جيدة. نتجت النتائج غير الكافية (عدم وجود تحسن في الرعاية، والوفيات، وتوقّف مراقبة الوفيات والاستجابة لها) عن حلقة مفرغة من نقص الإبلاغ، والبيانات غير الدقيقة، والمراجعة والتوصيات غير الكافية، وهو ما أدى إلى تثبيط الهمة والانسحاب. تم الإبلاغ عن بعض النتائج الضارة، مثل الإحالات غير الملائمة، وحالات النقص المتدهور في الموظفين، والذي نتج عن الخوف من التبعات السلبية، بما في ذلك اللوم، أو الإجراءات التأديبية، أو التقاضي.

الاستنتاج تشمل الشروط المطلوبة للمراقبة الفعالة لوفيات الأمهات و/أو وفيات الفترة المحيطة بالولادة والاستجابة لها ما يلي: فصل العملية عن الإجراءات القضائية والتأديبية؛ الإرشادات الشاملة والتدريب؛ والموارد الكافية لتنفيذ التوصيات؛ والإشراف الداعم لتمكين التعلم الآمن.

摘要

目的

旨在了解中低收入国家实施孕产妇和/或围产期死亡监测和响应的经验和相关人员的看法,以及该流程实现预期结果的机制。

方法

在 2022 年 6 月,我们系统地搜索了七个定性研究数据中关于在中低收入国家实施孕产妇和/或围产期死亡监测和响应的利益相关者的数据。两名评审员对论文进行了独立筛选并评估了论文质量。我们将各个主题进行整合以获得描述性的主题,并使用实际可行的方法来了解情境-机制-结果的结构关系。

结果

59 项研究符合纳入标准。周期性地采取功能性行动带来了积极结果(提高护理质量或降低死亡率)。有效的死亡监测和响应机制包括学习、保持警觉并执行可促进更多人员参与的建议。实现有效死亡监测和响应的关键条件是打造免于受责的学习环境和优秀的领导力。不充分的结果(不能改善护理质量和降低死亡率以及持续实施死亡监测和响应)源自漏报、数据不准确、审查和建议不足造成的恶性循环,这导致了消极怠工和工作疏离感。论文中报告了一些有害结果,如不适当的转诊和人员短缺加剧,这是由于担心承担负面后果(如指责、纪律处分或诉讼)所造成的。

结论

有效实施孕产妇和/或围产期死亡监测和响应所需的条件包括:将该过程与诉讼和纪律程序独立开来;开展全面指导和培训;拥有足够资源以执行建议;以及提供确保安全学习的支持性监督。

Резюме

Цель

Понять опыт и восприятие людей, осуществляющих эпиднадзор за материнской и (или) перинатальной смертностью и ответные меры в странах с низким и средним уровнем дохода, а также механизмы, благодаря которым этот процесс может привести к намеченным результатам.

Методы

В июне 2022 года в семи базах данных был проведен систематический поиск качественных исследований заинтересованных сторон, осуществляющих эпиднадзор за материнской и (или) перинатальной смертностью и ответные меры в странах с низким и средним уровнем дохода. Два рецензента, независимо друг от друга, отбирали статьи и оценивали их качество. Для выявления описательных тем использовался тематический синтез и реалистичный подход для понимания структуры контекста-механизма-результата.

Результаты

Критериям включения соответствовали пятьдесят девять исследований. Благоприятные исходы (улучшение качества ухода или снижение смертности) подкреплялись функциональным циклом действий. В число механизмов эффективного эпиднадзора за смертностью и ответных мер входили обучение, внимательность и выполнение рекомендаций, которые мотивируют к дальнейшему участию. Ключевым контекстом для обеспечения эффективного эпиднадзора за смертностью и ответных мер являлась свободная от обвинений образовательная среда с хорошим руководством. Неудовлетворительные исходы (отсутствие улучшения ухода и снижения смертности, прекращение эпиднадзора за смертностью и ответных мер) стали результатом замкнутого круга занижения отчетных показателей, неточных данных, ненадлежащего анализа и рекомендаций, что привело к снижению мотивации и отстраненности. Сообщалось о некоторых неблагоприятных исходах, таких как ненадлежащие направления к врачам и усугубление нехватки персонала, что было вызвано страхом перед негативными последствиями, включая обвинения, дисциплинарные меры или судебные разбирательства.

Вывод

В число необходимых условий для эффективного эпиднадзора за материнской и (или) перинатальной смертностью и ответных мер входят: отделение процесса от судебных разбирательств и дисциплинарных процедур; комплексные руководства и обучение; достаточные ресурсы для выполнения рекомендаций; поддерживающий надзор для обеспечения безопасного обучения.

Introduction

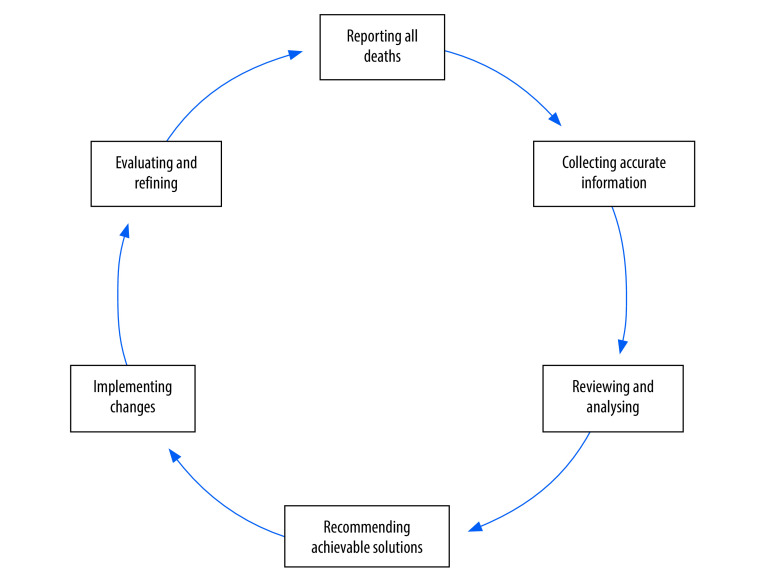

Many low- and middle-income countries are still far from attaining the sustainable development goals to reduce maternal and child mortality; one of the main obstacles is poor quality of health care.1 In 2004, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that all countries implement maternal death reviews,2 and in 2013 recommended all countries implement maternal death surveillance and response,3 to which perinatal deaths were added in 2016.4 Guidance on maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response was published in 2021.5 The existing programme theory, describing how the mortality audit cycle should function, is shown in Fig. 1 and Box 1.2–5

Fig. 1.

Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response cycle

Box 1. Programme theory for maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response.

Identifying and reporting

All maternal and perinatal deaths should be reported to produce valid statistics on mortality.

Collecting information

A truthful and complete account of the patient’s symptoms, treatment-seeking and management before their death should be obtained from verbal and/or social autopsy interviews, medical records and reports from health workers.

Reviewing and analysing information

The committee reviewing the account should reliably identify the cause of death and avoidable factors.

Recommending solutions

The committee should make effective recommendations to avoid recurrence of the same scenario.

Implementing changes

The recommendations made by the committee should be implemented.

Evaluating and refining

The implementation of the entire audit cycle should be monitored and, if necessary, changes should be made to achieve the desired goal of reducing maternal and perinatal mortality.

In a survey of low- and middle-income countries, 85% (88/103) had a national policy to review all maternal deaths.6 Most low- and middle-income countries that succeeded in reducing maternal and child mortality used some form of death reporting system to monitor progress, but only a minority used the full maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response cycle.7

Implementation of maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response in low- and middle-income countries is challenging because resources are more constrained than in high-income settings, but the opportunities to achieve a significant impact are greater. Maternal death reviews can reduce maternal mortality by up to 35% (odds ratio; OR: 0.65; 95% confidence interval, CI: 0.55–0.77) and perinatal death reviews have been associated with a 30% reduction in perinatal mortality (OR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.62–0.79).8–10 However, these data from health facility studies represent a best-case scenario. When scaling up to the national level, the outcomes are more heterogeneous. For example, among 35 facilities that have been part of the South African Perinatal Problem Identification Programme for at least 5 years, perinatal mortality declined in four facilities, increased in five, and did not change in the remaining 26 facilities.11,12

The reasons for this heterogeneity in effectiveness are unclear. Several scoping reviews describe different maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response processes in sub-Saharan Africa and low- and middle-income countries, some with contradictory interpretations.13–15 While one review suggested that the most important mechanisms for accountability were disciplinary action, legal redress and social reprisals,13 another review reported that fear of blame and punitive approaches undermined the process.14 These reviews highlight the need for more research on death surveillance and review processes, the context in which they are conducted,14 and the subjective experiences of individuals implementing maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response in different settings.15 None of the previous reviews systematically analysed qualitative studies or took a realist approach to understanding why maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response systems achieve positive or negative outcomes in different contexts.

Therefore, in this systematic review, we aimed to understand the experiences of people implementing maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response in low- and middle-income countries. We sought to understand the mechanisms by which this process achieves (or fails to achieve) its intended outcomes, and the contexts that trigger these mechanisms.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of qualitative studies. The protocol was registered on PROSPERO (PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021271527).

Literature search

We searched seven databases from their inception to June 2022: CINAHL, MEDLINE®, Embase®, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, Global Index Medicus, Web of Science and Google Scholar. We used a pre-planned strategy including terms for maternal or perinatal death reviews from a Cochrane review10 and a search filter for qualitative studies (see strategy in first data repository).16

Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria: studies using qualitative data collection and analysis methods, including participants who were involved in implementation of any part of the maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response process in low- and middle-income countries – including verbal and/or social autopsy when these involved investigation of maternal or perinatal deaths. We had no language restrictions. The reviewers then assessed the full text of the selected studies. We resolved disagreements by discussion with a third reviewer.

Critical appraisal

One of the reviewers evaluated the quality of the included full-text articles using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool for qualitative studies.17 The second reviewer independently evaluated a randomly selected 10% of the included articles; we found no significant disagreements.

Data extraction and analysis

We imported studies into NVivo, version 12 (QSR International Inc., Burlington, MA, United States of America). We used a thematic synthesis approach:18 two authors developed a preliminary coding frame based on a sample of studies and refined this further by discussion. Higher-order categories of codes were deductive (barriers and enablers) but lower-order categories were developed inductively and iteratively from the data in the texts. We coded subsequent studies line by line, focusing on the results and discussion sections, and created new codes when considered necessary. We used the codes to develop descriptive themes. To develop higher-order analytical themes, we used a realist approach.19 We recoded the included articles specifically looking for contexts, mechanisms, outcomes and context–mechanism–outcome configurations.19,20 We used these configurations to construct flow diagrams showing causal links and to refine the programme theory for maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response.

Results

Studies included

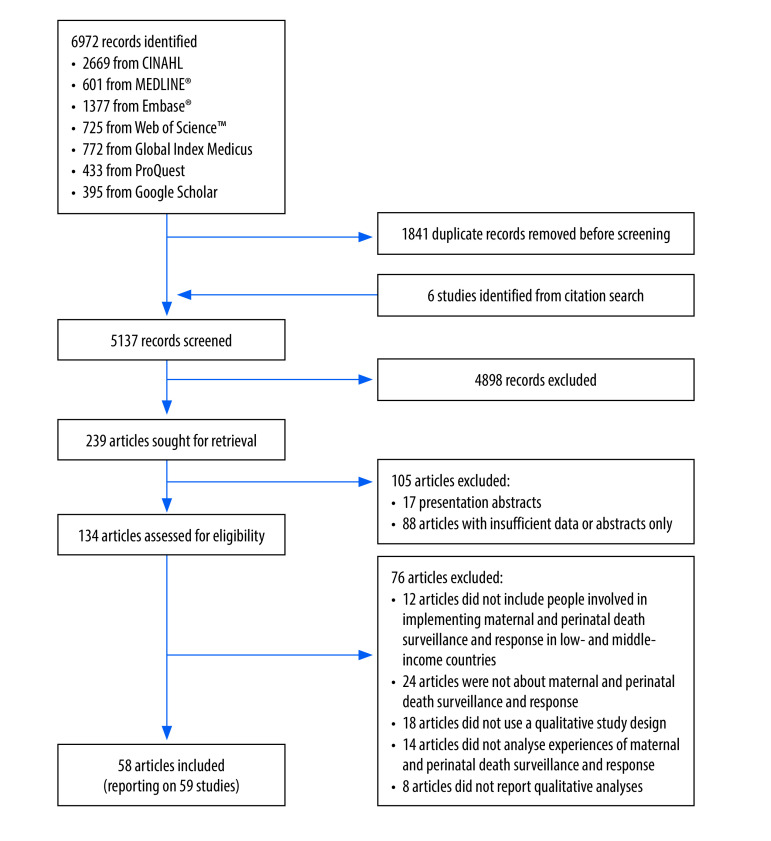

The initial searches yielded a total of 5137 articles after removal of duplicates. After screening, we finally included 58 publications, reporting on 59 different studies (Fig. 2).21–78 These studies included over 1891 participants from 30 low- and middle-income countries, ranging from community members to health workers and national-level stakeholders involved in implementation of maternal death reviews or maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of the selection of studies in the systematic review on maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response

Most studies (34/59) focused on maternal deaths (25 on maternal death reviews and nine on maternal death surveillance and response), 19 included both maternal and perinatal deaths, and six studies considered only perinatal or neonatal deaths (Table 1; available at: https://www.who.int/publications/journals/bulletin/). The overall effectiveness of the process was perceived as good (improved quality of care or reduced mortality) in 16 studies, inadequate in 21 studies and mixed in five studies; the perceived effectiveness was not reported in 17 studies. All studies were of sufficient quality (see details in the first data repository),16 although most did not adequately consider the relationship between the researcher and the participants.

Table 1. Studies on maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response included in the review.

| Study | Country, context | Type of death | Type of review | Perceived effectiveness of process | Study design | Data collection method | No. and type of participants | Type of analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbakar, 202121 | Sudan, national | Maternal | Maternal death surveillance and response | Inadequate | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | 54 maternal death surveillance and response staff, doctors and midwives | Thematic analysis |

| Abebe, et al., 201722 | Ethiopia, national | Maternal | Maternal death surveillance and response | Successful | Qualitative | Individual and group interviews | 69 frontline staff responsible for implementation of maternal death surveillance and response | Thematic content analysis |

| Aborigo et al., 201323 | Ghana, community | All | Verbal autopsy | Not specified | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | 36 bereaved families, field staff, physicians and local leaders | Thematic analysis |

| Afayo, 201824 | Uganda, health facility | Maternal | Maternal death surveillance and response | Inadequate | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews | 11 hospital staff and maternal death surveillance and response committee members | Thematic content analysis |

| Agaro et al., 201625 | Uganda, district health facility | Maternal and perinatal | Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response | Inadequate | Mixed methods | Semi-structured interviews | 76: 66 health workers and 10 key informants | Thematic content analysis |

| Armstrong et al., 201426 | United Republic of Tanzania, multiple levels | Maternal and perinatal | Maternal and perinatal death review | Inadequate | Qualitative | Document review and interviews | 37: 20 hospital staff, 12 district or regional coordinators, 5 national experts | Adapted thematic analysis |

| Ayele et al., 201927 | Ethiopia, health facility and community | Maternal and perinatal | Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response | Inadequate | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews and focus group discussions | 25 women group leaders in 3 focus groups; 11 health managers in in-depth interviews | Thematic content analysis |

| Bakker et al., 201128 | Malawi, health facility (rural and district) | Maternal | Maternal death review | Successful | Qualitative | In-depth interviews, focus group discussions and observation | 25 health workers | Not specified |

| Balogun & Musoke, 201429 | Sudan, national | Maternal | Maternal death review | Inadequate | Qualitative | In-depth interviews and focus group discussions | Medical and health stakeholders at the national, state and facility level in 12 in-depth interviews and 18 focus group discussions | Qualitative content analysis |

| Bandali et al., 201930 | Kenya, hospital and health centre | Maternal and perinatal | Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response | Successful | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews and focus group discussions | 5 health records information officers (interviews); maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response committee members (4 discussion groups) | Thematic analysis |

| Belizán et al., 201131 | South Africa, health facility | Perinatal | Perinatal Problem Identification Programme | Not specified | Qualitative | Focus group and workshop | 48 clinicians and coordinators in the Perinatal Problem Identification Programme in 4 focus group discussions | Framework analysis using stages-of-change model |

| Boyi Hounsou et al., 202261 | Benin, health district | Maternal | Maternal death review | Inadequate | Mixed methods | Online group discussions | 34 district medical officers in two online group discussions | Inductive thematic analysis |

| Biswas et al., 201433 | Bangladesh, community | Maternal, perinatal and neonatal | Maternal and perinatal death review | Successful | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews and focus group discussions | Health workers and community volunteers in 4 focus group discussions and 4 in-depth interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Biswas et al., 201534 | Bangladesh, health facility | Maternal, perinatal and neonatal | Maternal and perinatal death review | Successful | Qualitative | In-depth interviews, focus group discussions and document review | 46 health workers implementing facility death review: 35 in in-depth interviews; 11 in focus group discussions | Thematic analysis |

| Biswas et al., 201532 | Bangladesh, community | Maternal, perinatal and neonatal | Verbal autopsy | Successful | Qualitative | In-depth interviews, focus group discussions and participant observation | Health-care providers: 3 focus group discussions, 6 in-depth interviews, 6 participant observations | Thematic analysis |

| Biswas et al., 201635 | Bangladesh, community | Maternal, perinatal and neonatal | Social autopsy | Successful | Qualitative | In-depth interviews, focus group discussions, observation and document review | Health inspectors in 9 focus group discussions; 18 health workers and 12 community members in in-depth interviews | Content and thematic analysis |

| Bvumbwe, 201962 | Malawi, health facility | Maternal | Maternal death review | Inadequate | Qualitative | In-depth interviews and focus group discussions | 42 maternal death review committee members and 32 midwives: 4 focus group discussions with midwives; 4 focus group discussions with committee members; and 3 in-depth interviews with health zone technical officers | Thematic analysis |

| Cahyanti et al., 202136 | Indonesia, district health facility | Maternal | Maternal death review | Inadequate | Qualitative | Focus group discussions | 29 district audit committee members in 4 focus group discussions | Thematic analysis |

| Chirwa et al., 202263 | Malawi, district hospital | Maternal | Maternal death review | Inadequate | Qualitative | In-depth interviews and focus group discussions | 40 nurse midwives | Thematic content analysis |

| Combs Thorsen et al., 201437 | Malawi, urban health facility | Maternal | Maternal death review | Not specified | Mixed methods | Observation of participants of death review process | Observed data collection from bereaved family, health workers and medical records | Content analysis |

| Compaoré et al., 202264 | Ghana, health facility | Maternal | Maternal death review | Inadequate | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews | Health workers and managers | Not specified |

| Compaoré et al., 202265 | Liberia, county, health facility and community | Maternal and perinatal | Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response | Inadequate | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews | County-level health personnel, health facility staff, community health workers | Not specified |

| Congo et al., 201738, 202266,67 | Burkina Faso, regional and district hospital | Maternal | Maternal death review | Inadequate | Qualitative | In-depth interviews and document review | 73 health workers in maternity, pharmacy and laboratory units, and staff in administration and management | Framework analysis |

| Dartey & Ganga-Limando, 201478 | Ghana, district hospital, regional referral hospital and teaching hospital | Maternal | Maternal death review | Successful | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | 20 midwives involved in maternal death reviews | Thematic content analysis |

| Dartey, 2016 39 | Ghana, health centre, district hospital, regional referral hospital and teaching hospital | Maternal | Maternal death review | Successful | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews and focus group discussions | 39 midwives involved in maternal death review: 18 in-depth interviews and 8 focus group discussions | Thematic content analysis |

| de Kok et al., 201740 | Nigeria, health facility | Maternal | Maternal death review | Not specified | Qualitative | Observation of review meetings | Audit review team | Conversation and discourse analysis |

| Diallo et al., 202268 | Burkina Faso, district hospital | Maternal | Maternal death review | Inadequate | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | 9 midwives | Inductive thematic analysis |

| Dortonne et al., 200941 | Senegal and Mali, hospitals | Maternal | Maternal death review | Successful | Mixed methods | Questionnaires, checklist, interviews and document analyses | 39: 23 maternal death audit committee members and 16 national-level leaders | Not specified |

| Dumont et al., 200942 | Senegal, health facility | Maternal | Maternal death review | Successful | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews, focus group discussions, participant observation and document reviews | Health workers (maternal health) in 3 focus group discussions and 9 in-depth interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Gao et al., 200943 | China, health facility, community | Maternal | Maternal death surveillance and response | Inadequate | Mixed methods | Interviews, field observations and review of reports and audits | 18: 12 hospital leaders, 6 maternal and child health workers | Not specified |

| Hartsell, 201045 | United Republic of Tanzania, all levels (national, regional, district and health facility) including private and public facilities | Maternal | Maternal death review | Not specified | Descriptive qualitative case study | In-depth interviews, observation and document reviews | 15 health workers involved in data management of maternal deaths and deliveries | Not specified |

| Hofman et al., 201446 | Nigeria, hospital | Maternal | Maternal death review | Not specified | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews | Members of the maternal death review committee of 11 hospitals (number not specified) | Thematic framework |

| Jati et al., 201969 | Indonesia, urban health facilities and local government in Semarang | Perinatal | Perinatal death surveillance and response | Not specified | Qualitative | Focus group discussions | 20 local government officials and representatives of health facilities | |

| Jepkosgei et al., 202247 | Kenya, hospital | Neonatal | Neonatal death review | Not specified | Exploratory qualitative study | In-depth interviews, non-participant observation of morbidity and mortality meetings | Nurses and doctors: 17 in-depth interviews and 12 morbidity and mortality meetings | Thematic content analysis |

| Karimi et al., 201848 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), national, institutional (teaching universities) and health facility | Maternal | Maternal death surveillance and response | Successful | Qualitative | Review of documents and key informant interviews | 15: 3 health ministry deputies, 10 medical university staff, 2 staff in obstetrics units of specialized hospitals | Thematic |

| Khader et al., 202070 | Jordan, health facility | Perinatal | Perinatal death audits | Not specified | Qualitative | Focus group discussions | Paediatricians, obstetricians, nurses, midwives in 16 focus group discussions | Thematic content analysis |

| Kinney et al., 202049 | Nigeria, United Republic of Tanzania, Zimbabwe, health facility | Maternal and perinatal | Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response | Mixed | Mixed methods | Interviews and observation | 41: 4 national stakeholders and 37 regional and district government health officials supporting maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response | Thematic content analysis |

| Kongnyuy et al., 200850 | Malawi, health facility | Maternal | Maternal death review | Successful | Mixed methods | Focus group discussions | 60: maternal and neonatal health workers implementing the facility maternal death review and quality improvement team members | SWOT analysis |

| Kouanda et al., 202271 | Burundi, hospital | Maternal and perinatal | Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response | Mixed | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | 26 officials of the health ministry, hospital officers, officers of health regions and districts, and obstetricians and gynaecologists and midwives | Thematic analysis |

| Kouanda et al., 202272 | Chad, hospital (national, and district) | Maternal | Maternal death surveillance and response | Inadequate | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | 25 officials at the central level, staff of technical and financial partners (WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF) and obstetricians and gynaecologists | Thematic analysis |

| Melberg et al., 201951 and 202073 | Ethiopia, public health facility | Maternal | Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response | Inadequate | Qualitative | In-depth interviews and observation | 46: 11 primary caregivers who had experienced perinatal deaths, 5 men who had lost their partner to a maternal death, 4 health extension workers, 7 health workers in general and referral hospitals, 13 health workers in health centres, 6 health administrators responsible for implementation of maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response | Thematic content analysis |

| Muffler et al., 200752 | Morocco, health facility | Maternal | Maternal death review | Not specified | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews | 56 implementers in the audit process | Systematic content analysis |

| Mukinda et al., 202174 | South Africa, health district and subdistrict | Maternal and perinatal | Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response | Mixed | Descriptive qualitative case study | In-depth interviews and observation | 45 frontline health managers and providers involved with maternal, perinatal, neonatal and child death surveillance and response | Thematic analysis |

| Muvuka, 201953 | Democratic Republic of the Congo, hospital and health facility | Maternal | Maternal death surveillance and response | Mixed | Qualitative | In-depth interviews, document review and observation of one maternal death review session | 15 maternal death surveillance and response focal persons and members of maternal death review teams | Inductive thematic analysis |

| Nyamtema et al., 201054 | United Republic of Tanzania, hospital and health facility | Maternal and perinatal | Maternal and perinatal death review | Inadequate | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews and semi-structured questionnaire | 59: 29 health managers and 30 health-care providers | Qualitative content analysis |

| Owolabi et al., 201455 | Malawi, health facility | Maternal | Maternal death review | Not specified | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews | 8 individuals involved in implementing maternal death review | Thematic analysis |

| Patel et al., 200756 | India, community | Neonatal | Community neonatal death audits | Not specified | Qualitative | In-depth interviews and focus group discussions | Community members and family of the deceased in 3 in-depth interviews and 6 focus group discussions. Also included field staff from a subsequent study | Deductive thematic analysis |

| Richard, 200975 | Burkina Faso, urban district hospital | Maternal and perinatal | Maternal and perinatal death review | Not specified | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews | 35 members of staff from maternity and surgical departments | Thematic analysis |

| Russell, 202276 | International, international expert consultation meeting | Maternal and perinatal | Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response | Not specified | Qualitative | In-depth interviews and group interviews | 55 health workers with experience in maternal and/or newborn health in humanitarian settings, and/or programmatic or research experience in maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response | Thematic analysis |

| Said et al., 202157 | United Republic of Tanzania, health facility | Maternal | Maternal death surveillance and response | Inadequate | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | 60 involved in maternal death surveillance and response activities: 30 health providers in focus group discussions; 30 health managers in in-depth interviews | Inductive thematic analysis |

| Tayebwa et al., 202058 | Rwanda, health facility | Maternal and perinatal | Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response | Not specified | Mixed methods | Desk reviews,in-depth interviews and observations | 23: type not stated | Not specified |

| Upadhyaya et al., 201259 | India, district and peripheral health facility, community and/or village | Infant | Infant death review | Successful | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews and review of documents | 38 health-care providers involved in programme activities | Content analysis |

| van Hamersveld et al., 201244 | United Republic of Tanzania, district hospital | Maternal and perinatal | Maternal and perinatal death review | Inadequate | Qualitative | Participant observation and in-depth interviews | 23 health workers and managers | Inductive thematic analysis |

| WHO 201460 | India, all levels (national, regional, facility and community) | Maternal | Maternal death review | Successful | Mixed methods | Review of documents and reports, interviews and observations | Stakeholders at national, state and district levels | Not specified |

| Indonesia, all levels (national, regional, facility and community) | Maternal | Maternal death review | Mixed | Mixed methods | Review of documents and reports, and interviews | Informants from the health ministry, district health office, hospitals and health centres | Not specified | |

| Sri Lanka, national | Maternal | Maternal death review | Successful | Mixed methods | Stakeholder workshop and in-depth interviews | 20 former secretaries of health, former directors of the Family Health Bureau, provincial administrators, clinicians, representatives of professional colleges, national programme managers and representatives from international NGOs | Not specified | |

| Nepal, national | Maternal | Maternal death review | Not specified | Mixed methods | Document review, in-depth interviews and stakeholder workshop | 27: 16 doctors, 4 staff nurses, 5 medical recorders and 2 programme managers from 10 hospitals | Not specified | |

| Myanmar, national | Maternal | Maternal death review | Not specified | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews | 10–12 participants from 10 townships including township medical officer, obstetricians, township health nurse, station medical officers, focal persons of a rural health centre, and midwives | Not specified | |

| Yameogo et al., 202277 | Burkina Faso, health district (urban and rural) | Maternal | Maternal death surveillance and response | Inadequate | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | 23: 3 technical and financial partners, 2 central level managers, 2 regional health directors, 4 district management team members, 8 health-care providers and 4 community health workers | Thematic analysis |

NGO: nongovernmental organization; SWOT: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats; UNFPA: United Nations Population Fund; UNICEF: United Nations Children’s Fund; WHO: World Health Organization.

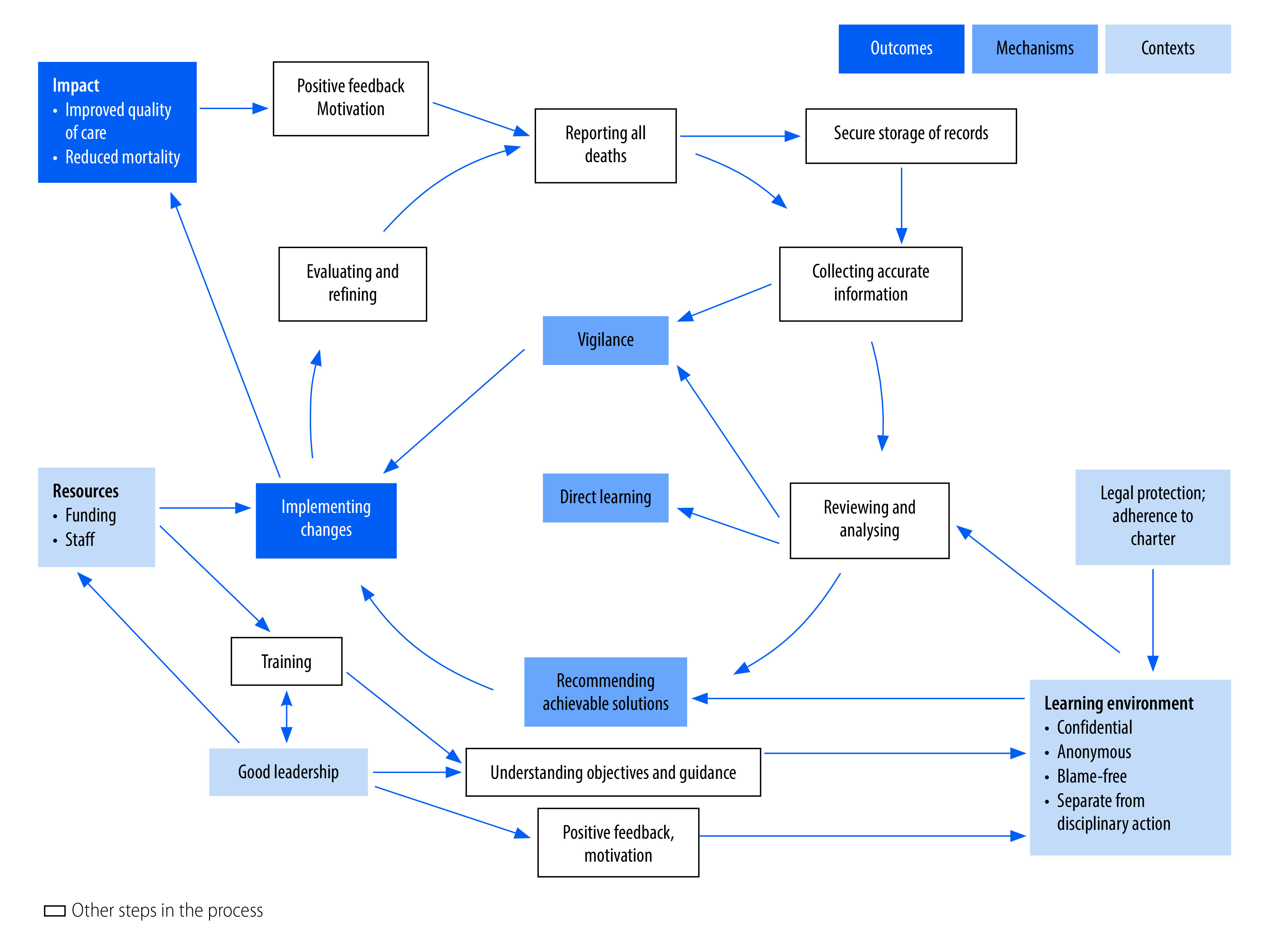

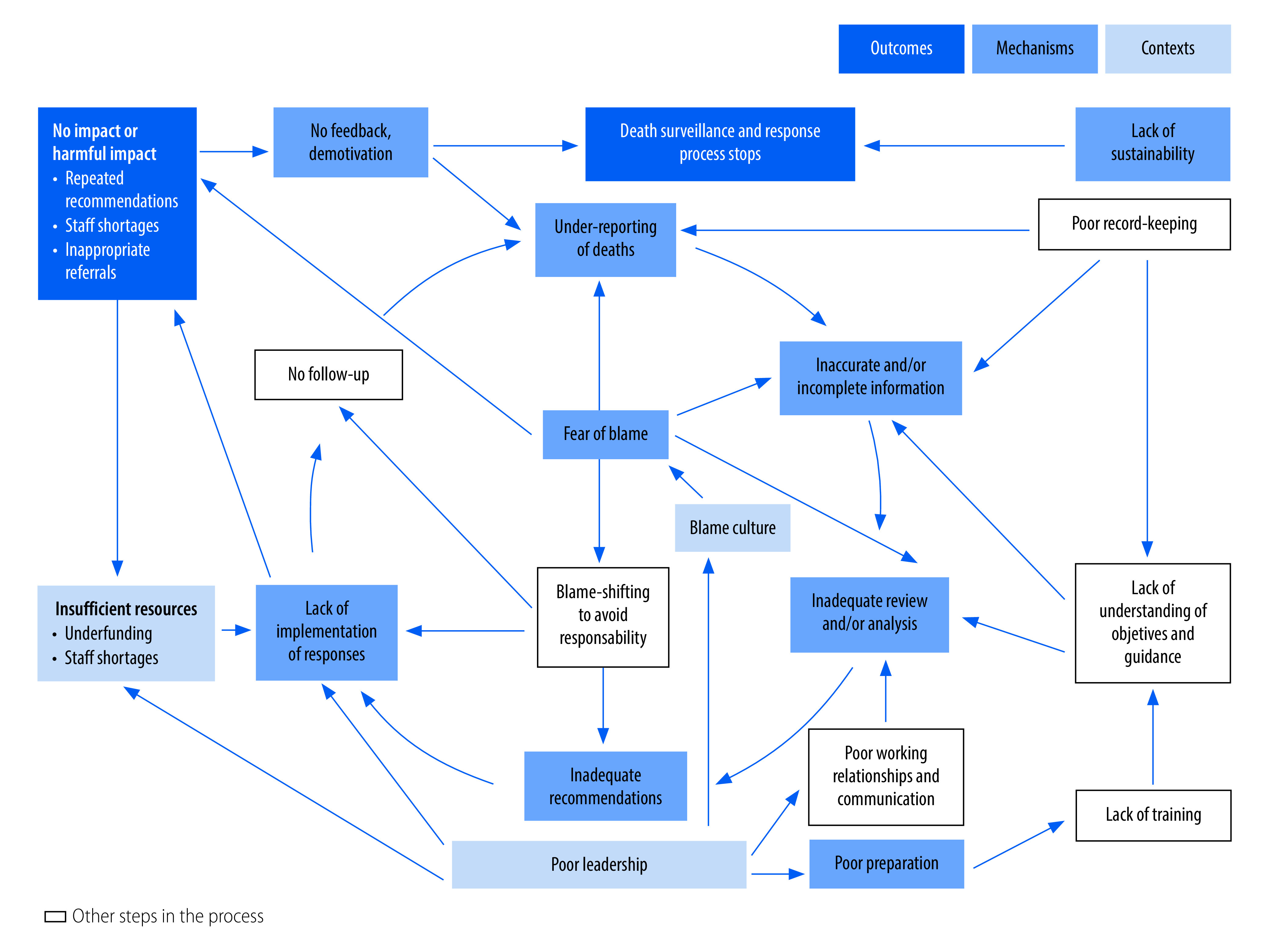

Two overarching programme theories emerged from our review of the studies: (i) a refined version of the classic action cycle, which explains how functional maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response systems reduce maternal and perinatal mortality (Fig. 3 and Table 2; full table in the second data repository);79 and (ii) the vicious cycle, which explains how dysfunctional systems can fail to achieve their intended objectives, or worse, lead to unintended harmful outcomes (Fig. 4 and Table 3; full table in the second data repository).79

Fig. 3.

Action cycle of a functional maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response process

Table 2. Mechanisms and contexts underlying functional maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response systems.

| Key mechanisms driving good outcomes | Key contexts that enable these mechanisms to operate | Examples, study and countrya |

|---|---|---|

| Preparing for implementation | Supportive national policy | Biswas et al., Bangladesh33 |

| Clear guidelines | Biswas et al., Bangladesh35 | |

| Comprehensive training of all stakeholders | Agaro et al., Uganda25 Bandali et al., Kenya30 |

|

| Good, committed and supportive leadership and drivers at all levels | Belizán et al., South Africa31 Dortonne et al., Senegal and Mali41 |

|

| Blame-free learning environment | Jepkosgei et al., Kenya47 | |

| Implementing comprehensive death reporting | Clear responsibilities | Biswas et al., Bangladesh34 |

| Clear lines of communication | Said et al., United Republic of Tanzania57 | |

| Collecting accurate information | Clear, accurate documentation | Biswas et al., Bangladesh34 |

| Secure storage of records | Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 | |

| User-friendly forms | WHO, Nepal60 | |

| Appropriate timing to interview families | Aborigo et al., Ghana23 | |

| Appropriate person to interview families | Biswas et al., Bangladesh33 Dumont et al., Senegal42 |

|

| Validation of data | Aborigo et al., Ghana23 Biswas et al., Bangladesh32 |

|

| Learning through participation in reflective review and analysis | Inclusive multidisciplinary review committee with key stakeholders, working as a team | Bandali et al., Kenya30 Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 |

| Clear communication about meetings | Congo et al., Burkina Faso38 | |

| Meetings embedded into routine work responsibilities | Belizán et al., South Africa31 Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 |

|

| Good attendance at review meetings | Bakker et al., Malawi28 | |

| Refreshments for staff at meetings | Jepkosgei et al., Kenya47 | |

| Skilled chairing to ensure the discussion is confidential, anonymous, blame-free (but with accountability), participatory, focused and time-efficient, and a useful learning experience for all involved | Armstrong et al., United Republic of Tanzania26 de Kok et al., Nigeria40 Jepkosgei et al., Kenya47 |

|

| Structured discussion | Jepkosgei et al., Kenya47 | |

| Evaluation of care against accepted standards | Cahyanti et al., Indonesia36 Kongnyuy et al., Malawi50 |

|

| Recommending achievable solutions | Focus on achievable goals | Bandali et al., Kenya30 |

| Involvement of the people who will need to implement the solutions | Bandali et al., Kenya30 Biswas et al., Bangladesh35 Kinney et al., Zimbabwe49 |

|

| Clear assignment of responsibility for each recommendation | Belizán et al., South Africa31 van Hamersveld et al., United Republic of Tanzania44 |

|

| Documentation of the recommendations and dissemination to all relevant stakeholders | Bandali et al., Kenya30 Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 |

|

| Implementing changes | Changes that can be incorporated within existing budget and workplan; sufficient resources to implement them | Abebe et al., Ethiopia22 Agaro et al., Uganda25 |

| Direct learning from the review | Biswas et al., Bangladesh35 Said et al., United Republic of Tanzania57 |

|

| Emotional impact of the review | Dartey, Ghana39 Richard et al., Burkina Faso75 |

|

| Vigilance because of the review process | van Hamersveld et al., United Republic of Tanzania44 Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 |

|

| Communities motivated to raise funds | Hofman & Mohammed, Nigeria46 WHO, Myanmar60 |

|

| Recommendations transmitted and implemented at national level | Abbakar, Sudan21 | |

| Follow-up of implementation | Armstrong et al., United Republic of Tanzania26 Bandali et al., Kenya30 Mukinda et al., South Africa74 |

|

| Evaluating and refining | Positive feedback | Bandali et al., Kenya30 Muffler et al., Morocco52 WHO, South-East Asia60 |

| Supervision and mentoring, external champions and facilitators | Belizán et al., South Africa31 Bandali et al., Kenya30 Dortonne et al., Mali and Senegal41 |

WHO: World Health Organization.

a See second data repository for full table with quotations and comments.79

Fig. 4.

Vicious cycle of a dysfunctional maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response process

Table 3. Contexts and mechanisms underlying dysfunctional maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response systems.

| Key mechanisms driving poor outcomes | Key contexts that enable mechanisms to operate | Examples, study and countrya |

|---|---|---|

| Fear of blame (at all levels) | Political pressure to reduce maternal deaths | Melberg et al., Ethiopia51 |

| Punitive environment | Abbakar, Sudan21 Abebe et al., Ethiopia22 Combs Thorsen et al., Malawi37 Melberg et al., Ethiopia73 |

|

| Increasing litigation against health workers | Gao et al., China43 Melberg et al., Ethiopia73 |

|

| Blame culture: maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response process is not separated from litigation and disciplinary process | Cahyanti et al., Indonesia36

Karimi et al., Iran (Islamic Republic of)48 Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 |

|

| Inadequate preparation | Guidelines insufficient or non-existent | Abebe et al., Ethiopia22 Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 |

| Staff unaware of guidelines | Cahyanti et al., Indonesia36 Said et al., United Republic of Tanzania57 |

|

| Lack of training | Abebe et al., Ethiopia22 Congo et al., Burkina Faso38 Said et al., United Republic of Tanzania57 |

|

| Poor leadership: no support for staff | Afayo, Uganda24 Muffler et al., Morocco52 |

|

| Vertical process, not integrated | Balogun & Musoke, Sudan29 Hartsell, United Republic of Tanzania45 |

|

| Under-reporting of deaths | Fear of blame | Abbakar, Sudan21 Melberg et al., Ethiopia51 Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 |

| Political pressure | Khader et al., Jordan70, Melberg et al., Ethiopia51 | |

| Social stigma and cultural beliefs | Biswas et al., Bangladesh33 Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 |

|

| No mandatory reporting for out-of-hospital deaths | Dumont et al., Senegal42 Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 |

|

| Inaccurate or incomplete information | Fear of blame: concealing or falsifying information | Agaro et al., Uganda25 Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 Said et al., United Republic of Tanzania57 |

| Staff lack of understanding of purpose | Kinney et al., Nigeria49 | |

| Poor record-keeping | Dumont et al., Senegal42 Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 |

|

| Resource shortages: insufficient time to collect data | Hartsell, United Republic of Tanzania45 | |

| Data collection forms too long and/or complex and/or unavailable | WHO, Myanmar60 | |

| Inadequate review | Inaccurate and/or insufficient information impeding review process | Gao et al., China43 Owolabi et al., Malawi55 |

| Key stakeholders not involved or invited | Abbakar, Sudan21 Dumont et al., Senegal42 Gao et al., China43 Jepkosgei et al., Kenya47 |

|

| Non-attendance of review committee members because of staff shortages, workload, competing priorities, poor communication or demotivation | Afayo, Uganda24 Kinney et al., United Republic of Tanzania49 Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 Congo et al., Burkina Faso67 ,van Hamersveld et al., United Republic of Tanzania44 |

|

| Lack of incentives to participate | Afayo, Uganda24 Agaro et al., Uganda25 |

|

| Ineffective participation of members because of demotivation and/or hierarchy | Armstrong et al., United Republic of Tanzania26 Cahyanti et al., Indonesia36 de Kok et al., Nigeria40 Richard et al., Burkina Faso75 |

|

| Lack of confidentiality | Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 Congo et al., Burkina Faso67 |

|

| Fear of blame | Jepkosgei et al., Kenya47 Muffler et al., Morocco52 |

|

| Blame-shifting and/or avoiding responsibility | Jepkosgei et al., Kenya47 Melberg et al., Ethiopia51 |

|

| Inadequate recommendations | Poor chairing | Jepkosgei et al., Kenya47 |

| Lack of focus during meetings | de Kok et al., Nigeria40 Hartsell, United Republic of Tanzania45 WHO, Indonesia60 |

|

| Blame-shifting and/or avoiding responsibility | Armstrong et al., United Republic of Tanzania26 Cahyanti et al., Indonesia36 Gao et al., China43 |

|

| Inadequate implementation | Recommendations not actionable | Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 |

| Key stakeholders (responsible for implementation) absent from meetings | Nyamtema et al., United Republic of Tanzania54 WHO, India60 |

|

| Unclear responsibility and/or accountability | Armstrong et al., United Republic of Tanzania26 | |

| Avoidance of responsibility | Balogun & Musoke, Sudan29 Cahyanti et al., Indonesia36 |

|

| Insufficient resources to allow implementation | Agaro et al., Uganda25 Cahyanti et al., Indonesia36 Karimi et al., Iran (Islamic Republic of)48 |

|

| Lack of feedback and/or dissemination of recommendations | Kouanda et al., Chad72 | |

| Lack of follow-up; no feedback or incentive to implement | Jepkosgei et al., Kenya47 | |

| Demotivation, disengagement, discontinuation | Demotivation of participants because of lack of implementation or positive feedback | Agaro et al., Uganda25 Muffler et al., Morocco52 Nyamtema et al., United Republic of Tanzania54 |

| Lack of supportive supervision | Agaro et al., Uganda25 Muvuka, Democratic Republic of the Congo53 |

|

| Unintended harmful consequences | Exacerbation of staff shortages | Bakker et al., Malawi28 Kinney et al., United Republic of Tanzania49 |

| Defensive practice, inappropriate referrals | Melberg et al., Ethiopia51 | |

| Unsustainable process | Over-dependence on foreign aid | Congo et al., Burkina Faso38 Hofman & Mohammed, Nigeria46 Said et al., United Republic of Tanzania57 Kouanda et al., Chad72 |

| Frequent staff turnover and lack of handover and training | Abebe et al., Ethiopia22 Hofman & Mohammed, Nigeria46 |

|

| Over-dependence on one person | Abbakar, Sudan21 van Hamersveld et al., United Republic of Tanzania44 |

WHO: World Health Organization.

a See second data repository for full table with quotations and comments.79

Action cycle

Outcomes

Successful outcomes of maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response included implementation of positive changes, especially at the facility level, such as improvements in quality of care, behavioural changes and targeted actions to address specific issues. Two studies41,50 were linked to quantitative studies8,80 demonstrating reductions in mortality.

Mechanisms

Three key mechanisms led to implementation of positive change.

Implementation of recommendations

Formulation and implementation of effective recommendations are commonly assumed to be the only mechanism of action for maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response.4 They are underpinned by a relatively complicated chain of events (Fig. 3 and Table 2). Most examples of effective responses were targeted actions implemented in individual facilities.25 Although WHO guidelines recommend that aggregated data be analysed at district and national levels to identify, recommend and implement higher-level solutions,6 documented examples of these actions were rare.21

Learning from case discussions

Learning from mistakes was a powerful behaviour-change mechanism mentioned by several respondents and was facilitated by a learning environment in the facility47 and community-based review meetings.35 Behaviour change was also motivated by the emotional experience of hearing the stories about the maternal and perinatal deaths and how these cases had been (mis)managed.39,62,75

Increased vigilance

This learning, and the review process itself, were reported to make health workers more vigilant in their daily practice, because they knew that if a patient died, their actions and records would be reviewed.44,53,75

Contexts

Underpinning these mechanisms is a learning environment (Fig. 3), where people feel safe to honestly report deaths, disclose accurate information and openly discuss the cases, including any mistakes in their management.47,53,56,74 Learning environments assure confidentiality, anonymity and separation from blame or any disciplinary process. Although several respondents recommended legal protection at the national level to prevent data from maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response being used in litigation, only South Africa had enacted this protection which “has been ratified by relevant judicial bodies.”81

In the absence of such legal protection, the next best context was an audit charter; members of the maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response committee were required to sign this charter to indicate their commitment to the principles of good conduct of clinical audit, including confidentiality, before participating in any session.38,75 Good leadership and chairing of meetings at the facility level also create a safe space for open discussion (Fig. 3 and Table 2).40 Adequate resources enable implementation of the process and of recommendations.

Vicious cycle

In contrast, many studies reported elements of a vicious cycle resulting in dysfunctional death surveillance and response (Fig. 4 and Table 3).

Outcomes

The commonest negative outcome was simply the lack of any change.49,77 In some cases, the maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response process stopped.72 Two studies reported on the maternal and perinatal death review process in the same urban district hospital in Burkina Faso in 2004–200575 and 2015–2016.77 Although this was one of the pioneer hospitals, in the second study an informant from the district level reported, “I know the team is there, but I don’t believe that this committee ever has a session.”77

More worryingly, a few studies reported harmful outcomes. First, staff shortages could be worsened as staff became afraid to work on the labour ward,28,62 some took several weeks off work after an upsetting review73 and junior doctors were deterred from choosing obstetrics as a career.73 Second, some staff practised defensive medicine such as inappropriate referral of unstable patients at high risk of death.51,73 Third, an extreme example given was refusal of admission to referral facilities of women who seemed likely to die, possibly to avoid damaging mortality statistics.76 Fourth, serious repercussions were reported for a woman who had complained that a midwife had treated her harshly; the midwife recognized herself in the audit session and complained to the woman’s parents.75

Mechanisms

Fear of blame (and of negative consequences such as disciplinary action or litigation) was the most pervasive mechanism. This fear inhibited learning and participation, and led to disengagement from the maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response process at all stages, which resulted in under-reporting, inaccurate data, inadequate participation in reviews, inadequate formulation of solutions and avoidance of responsibility. Fear of blame usually resulted from insufficient confidentiality or anonymity, and the death review process not being separated from disciplinary procedures.76 Telling participants that the process was blame-free was insufficient to allay fears when senior managers were present who would also be in charge of disciplinary procedures53,76 or when litigation against health workers was increasing.73

Inadequate preparation enabled the blame culture to persist as staff were unsure how to implement maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response.22 Many references were made to: inadequate or unavailable guidance; lack of training; poor leadership; charters not being signed;38 and maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response being structured as a separate vertical programme rather than being integrated with other public health systems.29,45

Under-reporting of deaths was often due to fear of blame or other negative consequences, such as reduced funding,21,53,73,76 but also resulted from social stigma,33 cultural beliefs, non-mandatory reporting53 and political pressure.51,72,73

Inaccurate and/or incomplete information undermines the review process. Although poor record-keeping was common,42,53 several reports noted deliberate falsification of records25,57,70,73 or misclassification of deaths70,76 to avoid blame or reputational damage. Sometimes staff did not collect the information because they simply did not have time45 or the correct forms,60 or did not understand the purpose of maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response.49

Inadequate review was the inevitable consequence of inaccurate information: “it is essentially garbage in, garbage out.”55 Reviews could also fail if: the committee did not include all necessary stakeholders; some key stakeholders did not attend; stakeholders attended but felt unable to participate because of disengagement or hierarchical relationships; or stakeholders feared blame or attempted to shift blame to others.26,36,40

Inadequate recommendations result from inadequate review. Poor chairing, lack of focus in review meetings and blame-shifting26,36,43 also impaired the formulation of effective recommendations.40 Sometimes meetings focused on accurately determining the cause of death at the expense of formulating effective recommendations.45

Non-implementation of recommendations was inevitable if they were unachievable. Furthermore, implementation rarely happened if: responsibility for implementation was unclear;44 the individuals responsible for implementation were not involved in the review;21,38,54,60 recommendations were not fed back to those responsible for implementation;30,44 implementers avoided taking responsibility;40,43 or no mechanism was in place to follow up on implementation.76,77 Insufficient resources also prevented implementation.25,36,48,72

Demotivation and disengagement resulted from non-implementation and the perception that the process was not achieving its intended aim.25,52,54 The lack of any incentives was also demotivating.24,25,76

Lack of sustainability resulted from over-dependence on foreign aid,38,46,72 or on a small number of staff.21 If no team or mechanism existed for training new staff, the process would stop when key staff were absent or left, which was common given high staff turnover in many settings.

Contexts

Three key contexts triggered the mechanisms leading to dysfunctional maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response. First, a blame culture heightens fear of blame, which was widely reported in health workers and families being questioned about a death. This problem was exacerbated in countries under an authoritarian system, where confidentiality was not guaranteed75 and the maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response process was not separated from litigation or disciplinary procedures,51 where families had no avenues for complaining apart from litigation,73 and where health workers could be detained by the police after maternal or child deaths.22,73,82 Paradoxically, high-level political commitment to reducing maternal mortality sometimes resulted in pressure on health workers not to report deaths.51,72,73

Second, insufficient resources prevented: adequate preparation for maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response; adequate data collection; convening of review meetings; and implementation of recommendations.60,63 Staff shortages meant that key stakeholders could not leave clinical duties to complete investigations or attend meetings34,44,50,53 and also that anonymity was not possible in review meetings.67 In some cases, sufficient forms were not available.60 Staff were often expected to attend meetings during lunch breaks or after work, but were reluctant to do so if no refreshments or financial compensation were provided.25 Lack of any budget for maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response also made it difficult to implement many recommendations;44 for example buying new equipment or holding community meetings.

Third, poor leadership at facility, district or national levels perpetuated unfavourable environments and behaviour, including: the blame culture,63 a general lack of commitment to maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response,54,72 under-resourcing, frequent staff turnover, poor preparation for maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response, insufficient communication, poor chairing of surveillance and response meetings,52 non-implementation and follow-up of recommendations, and general demotivation.42

Discussion

We found 59 qualitative studies investigating implementation of maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response in low- and middle-income countries. To achieve a functional action cycle with positive outcomes, such as reduced mortality and improved quality of care, a blame-free learning environment needs to be nurtured, clearly separated from litigation and disciplinary processes. Although WHO guidelines state that a mortality audit “is not a solution in itself,”4 several studies found that a learning environment enables not only the formulation of achievable recommendations, but also direct learning from the process and a healthy vigilance regarding quality of care. Good outcomes motivate staff to remain engaged, making the process sustainable.

In stark contrast, maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response often became a dysfunctional vicious cycle in the context of a blame culture, poor leadership and insufficient resources. Fear of blame inhibits all steps of the surveillance and response cycle. This fear not only inhibits intended outcomes but can also provoke harmful outcomes such as falsification of information, worsened staff shortages, inappropriate referrals or even the refusal to accept referrals, with the intention of avoiding responsibility. Our findings contradict the conclusions of the 2016 study that reported disciplinary action, legal redress and social reprisals were the most important mechanisms for accountability:13 we found that disciplinary action, litigation and social reprisals were likely to result in disengagement, lack of learning and negative outcomes.

While the literature search was comprehensive and the realist approach provided a useful framework for understanding causal pathways, the maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response process is cyclical rather than linear and a particular issue could be a context, a mechanism or an outcome at different points in the cycle. While other study types may also contain useful information, we only included qualitative studies because we were interested in the subjective experiences of those participating in maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response. However, social desirability bias is likely to be an important weakness of any research in contexts where freedom of speech is limited and a fear of blame exists, both of which may prevent participants from being completely open and honest about their experiences.51 Nevertheless, our review included several articles giving candid accounts of dysfunctional maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response processes in several settings. As the bias is likely to favour positive accounts, the reality could be worse than has been reported.

Most studies did not adequately consider the relationship between researchers and interviewees, and it is likely that this relationship influenced reported perceptions of the success, or failure, of the maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response process. Furthermore, implementation of maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response may have both positive and negative aspects in a single country or study.

Our results have implications for policy and practice. First, it is imperative to ensure that necessary preparations have been made before attempting to implement a maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response process. The essential conditions to ensure an effective process are good leadership, willingness and ability to provide a safe, blame-free learning environment and sufficient resources to support the surveillance and response process and implementation of its recommendations. In the context of a blame culture (including litigation and disciplinary procedures), poor leadership and insufficient resources, the process could do more harm than good. Turning a vicious cycle into an action cycle can be more difficult than starting the whole process from scratch, because fear of blame can persist for a long time.53

Second, direct learning from review meetings has been ignored as an important mechanism by many implementers. Thus, participatory review meetings on site and involving as many relevant staff as possible are likely to be more effective at promoting positive behaviour change than remote committee meetings with only a small number of participants.

Third, to evaluate maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response, it is important to assess not only the level of implementation of recommendations, but also whether participants are learning from the process, changing their own practice and seeing positive changes. Monitoring for possible adverse events of the process is also important, such as inappropriate referrals or worsening staff shortages. Monitoring and evaluation focusing on death reporting and cause of death classification may detract from the response component to improve outcomes.

Fourth, an adaptable toolbox of strategies to improve implementation of maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response would be valuable, based on experiences identified through this review as well as behaviour-change theory.

Our findings revealed priorities for future research. First, an intervention to improve implementation of maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response could be co-created with teams already conducting this process in low-income contexts, based on their experience and findings from this review. Scarce resources should not be a barrier to implementation, as several examples of effective review processes in low- and middle-income countries exist.8–10 A behavioural science approach should be taken to planning and optimizing the intervention, for example using the person-based approach,83 with members of death review committees in different settings. Of particular importance would be to evaluate whether such an intervention can shift a vicious cycle into a positive action cycle.

Second, more research is needed to understand how to achieve the optimal balance between a blame-free anonymous process, while maintaining accountability.47 Although WHO has suggested high-level strategies to minimize the blame culture,5,84 challenges exist because a completely blame-free, anonymous process may also remove accountability and responsibility for implementing actions,73 while a focus on accountability may instil fear of blame.73 Completely removing blame from the maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response process is almost impossible, because negligence will be uncovered and will need to be tackled.57 Although disciplinary procedures should be kept separate from maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response, in practice this separation may be impossible to achieve in district hospitals and communities where the head of the maternity unit is probably responsible for both disciplinary procedures and the surveillance and response process. A certain level of accountability and vigilance is one of the key mechanisms for a maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response system to achieve its objectives. A sensitive, inclusive death review process could provide a way to address concerns of bereaved families and sensitively inform them about their loss; this approach is important to explore, as it could reduce conflict and unjustified blame of individual health workers.70,73

In conclusion, maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response can be an effective behaviour-change quality-improvement intervention even in low- and middle-income settings with limited resources, provided the process is conducted in a largely blame-free learning environment, supported by good leadership and sufficient resources.

Funding:

MW’s salary is partly funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR 302412).

Competing interests:

MW is a member of the WHO technical working group on maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response. Other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Joseph NT, Danaei G, García-Saisó S, Salomon JA. Mortality due to low-quality health systems in the universal health coverage era: a systematic analysis of amenable deaths in 137 countries. Lancet. 2018. Nov 17;392(10160):2203–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31668-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyond the numbers: reviewing maternal deaths and complications to make pregnancy safer. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42984 [cited 2022 Aug 9].

- 3.Maternal death surveillance and response: technical guidance. Information for action to prevent maternal death. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Available from:http://https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/87340 [cited 2022 Aug 9].

- 4.Making every baby count: audit and review of stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/249523 [cited 2022 Aug 9].

- 5.Maternal and perinatal death and surveillance and response: materials to support implementation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/348487 [cited 2022 Aug 9].

- 6.Time to respond: a report on the global implementation of maternal death surveillance and response. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/249524 [cited 2022 Aug 9].

- 7.Ahmed SM, Rawal LB, Chowdhury SA, Murray J, Arscott-Mills S, Jack S, et al. Cross-country analysis of strategies for achieving progress towards global goals for women’s and children’s health. Bull World Health Organ. 2016. May 1;94(5):351–61. 10.2471/BLT.15.168450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dumont A, Fournier P, Abrahamowicz M, Traoré M, Haddad S, Fraser WD; QUARITE research group. Quality of care, risk management, and technology in obstetrics to reduce hospital-based maternal mortality in Senegal and Mali (QUARITE): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2013. Jul 13;382(9887):146–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60593-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pattinson R, Kerber K, Waiswa P, Day LT, Mussell F, Asiruddin SK, et al. Perinatal mortality audit: counting, accountability, and overcoming challenges in scaling up in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009. Oct;107 Suppl 1:S113–21, S121–2. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willcox ML, Price J, Scott S, Nicholson BD, Stuart B, Roberts NW, et al. Death audits and reviews for reducing maternal, perinatal and child mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020. Mar 25;3(3):CD012982. 10.1002/14651858.CD012982.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pattinson R, editor. Saving babies 2008–2009: seventh report on perinatal care in South Africa. Pretoria: Tshepesa Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pattinson R, editor. Saving babies 2010–2011: eighth report on perinatal care in South Africa. Pretoria: Tshepesa Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin Hilber A, Blake C, Bohle LF, Bandali S, Agbon E, Hulton L. Strengthening accountability for improved maternal and newborn health: a mapping of studies in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016. Dec;135(3):345–57. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lusambili A, Jepkosgei J, Nzinga J, English M. What do we know about maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity audits in sub-Saharan Africa? A scoping literature review. Int J Hum Rights Healthc. 2019;12(3):192–207. 10.1108/IJHRH-07-2018-0052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinney MV, Walugembe DR, Wanduru P, Waiswa P, George A. Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review of implementation factors. Health Policy Plan. 2021. Jun 25;36(6):955–73. 10.1093/heapol/czab011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willcox ML, Okello IA, Maidwell-Smith A, Tura AK, van den Akkerd T, Knighte M. Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Supplementary material [data repository]. London: figshare; 2022. 10.6084/m9.figshare.21360267 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.CASP qualitative checklists [internet]. Oxford: Critical Appraisal Skills Programme; 2018. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/http://[cited 2022 May 31].

- 18.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008. Jul 10;8(1):45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review – a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005. Jul;10(1) Suppl 1:21–34. 10.1258/1355819054308530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pawson R. Evidence-based policy: the promise of “realist synthesis”. Evaluation. 2002;8(3):340–58. 10.1177/135638902401462448 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbakar NAO. Maternal death surveillance and response in Sudan: an evidence-based, context-specific optimisation to improve maternal care. Oxford: University of Oxford; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abebe B, Busza J, Hadush A, Usmael A, Zeleke AB, Sita S, et al. ‘We identify, discuss, act and promise to prevent similar deaths’: a qualitative study of Ethiopia’s maternal death surveillance and response system. BMJ Glob Health. 2017. Mar 14;2(2):e000199. 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aborigo RA, Allotey P, Tindana P, Azongo D, Debpuur C. Cultural imperatives and the ethics of verbal autopsies in rural Ghana. Glob Health Action. 2013. Sep 19;6(1):18570. 10.3402/gha.v6i0.18570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Afayo V. Maternal death surveillance and response: barriers and facilitators. Arua regional referral hospital. Kampala: Makerere University; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agaro C, Beyeza-Kashesya J, Waiswa P, Sekandi JN, Tusiime S, Anguzu R, et al. The conduct of maternal and perinatal death reviews in Oyam District, Uganda: a descriptive cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2016. Jul 14;16(1):38. 10.1186/s12905-016-0315-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armstrong CE, Lange IL, Magoma M, Ferla C, Filippi V, Ronsmans C. Strengths and weaknesses in the implementation of maternal and perinatal death reviews in Tanzania: perceptions, processes and practice. Trop Med Int Health. 2014. Sep;19(9):1087–95. 10.1111/tmi.12353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayele B, Gebretnsae H, Hadgu T, Negash D, G/silassie F, Alemu T, et al. Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response in Ethiopia: achievements, challenges and prospects. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223540. 10.1371/journal.pone.0223540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakker W, van den Akker T, Mwagomba B, Khukulu R, van Elteren M, van Roosmalen J. Health workers’ perceptions of obstetric critical incident audit in Thyolo District, Malawi. Trop Med Int Health. 2011. Oct;16(10):1243–50. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02832.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balogun HA, Musoke SB. The barriers of maternal death review implementation in Sudan – a qualitative assessment. Solna: Karolinska Institutet; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandali S, Thomas C, Wamalwa P, Mahendra S, Kaimenyi P, Warfa O, et al. Strengthening the “P” in Maternal and Perinatal Death Surveillance and Response in Bungoma county, Kenya: implications for scale-up. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019. Aug 30;19(1):611. 10.1186/s12913-019-4431-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belizán M, Bergh A-M, Cilliers C, Pattinson RC, Voce A; Synergy Group. Stages of change: a qualitative study on the implementation of a perinatal audit programme in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011. Sep 30;11(1):243. 10.1186/1472-6963-11-243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biswas A, Fazlur R, Abdul H, Eriksson C, Dalal K. Experiences of community verbal autopsy in maternal and newborn health of Bangladesh. Healthmed. 2015;9(8):329–38. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biswas A, Rahman F, Eriksson C, Dalal K. Community notification of maternal, neonatal deaths and still births in Maternal and Neonatal Death Review (MNDR) system: experiences in Bangladesh. Health. 2014;6(16):2218–26. 10.4236/health.2014.616257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biswas A, Rahman F, Eriksson C, Halim A, Dalal K. Facility death review of maternal and neonatal deaths in Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2015. Nov 5;10(11):e0141902. 10.1371/journal.pone.0141902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biswas A, Rahman F, Eriksson C, Halim A, Dalal K. Social autopsy of maternal, neonatal deaths and stillbirths in rural Bangladesh: qualitative exploration of its effect and community acceptance. BMJ Open. 2016. Aug 23;6(8):e010490. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cahyanti RD, Widyawati W, Hakimi M. “Sharp downward, blunt upward”: district maternal death audits’ challenges to formulate evidence-based recommendations in Indonesia – a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021. Oct 27;21(1):730. 10.1186/s12884-021-04212-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Combs Thorsen V, Sundby J, Meguid T, Malata A. Easier said than done!: methodological challenges with conducting maternal death review research in Malawi. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014. Feb 21;14(1):29. 10.1186/1471-2288-14-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Congo B, Sanon D, Millogo T, Ouedraogo CM, Yaméogo WME, Meda ZC, et al. Inadequate programming, insufficient communication and non-compliance with the basic principles of maternal death audits in health districts in Burkina Faso: a qualitative study. Reprod Health. 2017. Sep 29;14(1):121. 10.1186/s12978-017-0379-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dartey AF. Development of an employee assistance programme (EAP) for midwives dealing with maternal death cases. The Ashanti Region, Ghana [dissertation]. Cape Town: University of the Western Cape; 2016. [Google Scholar]