Abstract

A growing number of research articles have been published on the use of halide perovskite materials for photocatalytic reactions. These articles extend these materials’ great success from solar cells to photocatalytic technologies such as hydrogen production, CO2 reduction, dye degradation, and organic synthesis. In the present review article, we first describe the background theory of photocatalysis, followed by a description on the properties of halide perovskites and their development for photocatalysis. We highlight key intrinsic factors influencing their photocatalytic performance, such as stability, electronic band structure, and sorption properties. We also discuss and shed light on key considerations and challenges for their development in photocatalysis, such as those related to reaction conditions, reactor design, presence of degradable organic species, and characterization, especially for CO2 photocatalytic reduction. This review on halide perovskite photocatalysts will provide a better understanding for their rational design and development and contribute to their scientific and technological adoption in the wide field of photocatalytic solar devices.

Keywords: photocatalysis, photocatalytic CO2 reduction, halide perovskites, sustainable energy, solar fuels, design of photoreactors

1. Introduction

Today, clean energy production is often touted as one of the biggest challenges of the next 20 years. Clean energy is urgently needed to mitigate climate change, that has been exacerbated by the use of fossil fuels to power our industries and urban areas during decades. Indeed, the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties highlighted the need to move from fossil fuels to renewable sources.1,2

Solar energy is a promising and abundant clean energy source, and the technologies to harvest it and store it are rapidly developing. For example, solar energy can be harvested by solar panels and stored in batteries. However, conventional lithium batteries have energy densities of 1 MJ kg–1, in comparison with 55 MJ kg–1 in fuels such as methane.3 Alternatively, solar energy can also be stored in fuels such as hydrogen and hydrocarbons instead of in batteries. To achieve so-called solar fuels, it is necessary to drive reactions which can take up energy (endergonic reactions), so that solar energy can be stored in the bonds created between molecules. An approach to directly produce solar fuels is photocatalysis, that stores the solar energy in fuels involving semiconductors in direct contact with the reactants of the endergonic reactions. The application of photocatalysis to the field of solar energy is inspired by natural photosynthesis, where plants, under sunlight, reduce CO2 and produce glucose. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 is practically the reverse of CO2 combustion, and it has the potential to ensure high solar energy storage capabilities, making the most of properties inherent to carbon fuels. Photocatalysis of water (H2O) and CO2 can result in the following solar fuels and feedstocks: H2, CO, methanol (CH3OH), formic acid (HCOOH), methane (CH4), or C2+ products, or useful combinations thereof, such as syngas (CO + H2).

Concurrently, photocatalysis is also used as means of water purification in environmental applications. With a photocatalyst, light can break down organic dyes and pollutants into harmless CO2 or mineralized carbon such as carbonates. This method holds a comparative advantage against traditional ways of purifying water as it does not generate large volumes of waste material like flocculation, sedimentation, and filtration do. For further reading on photocatalytic water purification, we recommend this review by Chong et al.4 In addition, photocatalysis tends to have low operating costs since the reaction can take place under mild operating conditions of pressure, temperature, and volume, and it leverages the solar energy, with great potential in developing countries.

Regardless of the chosen application, photocatalysts need to have specific characteristics that are further detailed in this article, but as a whole, they need to be good absorbers of the solar spectrum for practical applications and semiconductors to generate separated charges with the potential to drive redox reactions. Metal oxides such as titanium dioxide (TiO2), zinc oxide (ZnO), α-Fe2O3, and WO3 have been studied for photocatalysis since the inception of the field by the seminal paper of Fujishima and Honda.5 The drawback has been that, despite their cost effectiveness and stability, they suffer from poor solar absorption and high recombination of photoinduced charges. Some of the most successful photocatalysts, such as TiO2 and ZnO, and even SrTiO3:Al, recently used in a 100 m2 scale plant,6 can only absorb in the ultraviolet (UV) range. As such, visible light photocatalysts have been much sought after as a means of maximizing use of the solar spectrum.

Following from binary metal oxides, oxide perovskites have also been investigated for their potential use as a photocatalyst. They follow a general cubic structure of ABO3, where O2– is an oxide anion, and A2+ and B4+ are divalent and tetravalent metallic cations. From there, it was a small leap until halide perovskites (HPs) took the spotlight, being materials with the same structure, but O2– is replaced with a halide anion, X– (X= Cl–, Br–, I–), A is a monovalent cation A+, and B is a metal divalent cation B2+, often Pb2+ or Sn2+. HPs have been one of the fastest-growing areas of research after they showed high performances in solar cells, currently reaching a power conversion efficiency above 25%.7 They have been shown to have excellent light absorption capabilities, long charge-carrier diffusion lengths, and high extinction coefficients, which means they can effectively absorb light and transport the photoinduced charge carriers relatively long distances (μm) to reach surface sites for redox reactions.8 They have been shown to be easily tunable, which allows band structure tailoring to fit specific applications. They are relatively cheap, and, when considering the new lead-free halide perovskites, environmentally friendly. However, they are not without their drawbacks, which include low thermal stability, especially when A+ is an organic cation (often CH3NH3+ or CH(NH2)+), low moisture stability, and high toxicity when prepared with Pb2+. For further detailing of this, we refer the reader to Section 4.1 on stability.9 Often, in photocatalytic applications, they must be in contact with water, and research is being done both through the lenses of improving stability or optimizing conditions so that the degradation is minimal. Other characteristics that bring HPs to the forefront of photocatalytic research are their tunable band gap by halide composition or doping.

This work will explain why HPs have risen through the ranks to become one of the photocatalytic materials with the most potential. By examining different synthesis methods and how they affect the structure and properties of HPs, we will draw conclusions on the advantages and disadvantages for specific applications. Further, we will define key factors influencing performance that explain the reasons for the trends observed in the literature, namely stability, band structure, size, morphology, charge separation capability, sorption behavior, and selectivity. Finally, we will delve into the challenges in working and characterizing HPs and important considerations to have when working in photocatalysis, shedding light on promising strategies to achieve an agreed-upon standard of performance.

2. Background: Mechanism and Applications

Photocatalysis is dependent upon the use of a semiconductor. On a given semiconductor material, electrons populate the valence band (VB) below the Fermi level. Energy levels which exist above the Fermi level, generally defined as the conduction band (CB), remain empty at ground state. Upon light excitation, electrons may transition from the VB to the CB. Conductors, such as most metals, have no gap or very small gap between these two bands because VB and CB overlap. Conversely, insulators have a large energy gap between the VB and CB (termed band gap). A semiconductor generally sits somewhere in the middle, in which photons with energy corresponding to UV or visible light are able to supply energy to excite electrons into the CB, leaving electron vacancies in the VB, commonly referred to as holes.

Broadly summarized, the mechanism of photocatalysis can be described with pseudochemical reactions that illustrate the mechanistic sequence of the process. The principle that underpins photocatalysis is that, through the photovoltaic effect, a photon with energy larger than the band gap can be absorbed by a semiconductor (SC) and promote an electron from the VB to the CB (eq 1). This means that light can be used to generate charge carriers and provide energy for reactions. Figure 1a illustrates what happens under illumination. A photon is absorbed by a semiconductor (SC), creating an exciton, an electron–hole pair. These can separate and diffuse to the surface. At surface sites, an excited electron can be used to reduce an oxidant and the positively charged hole can accept an electron from a reductant and oxidize it (eqs 2 and 3). However, charges may end up recombining and not being used productively, producing either excess heat or re-emitting light, as showcased in eqs 4 and 5:

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic showing how the absorption of a photon of energy hv leads to the separate charge carriers being used for photocatalytic reactions. (b) Schematic showing the thermodynamic (the straddling of the reaction potentials) and kinetic requirements (the overpotential needed as a driving force) for photocatalysis upon the absorption of a photon by a heterogeneous photocatalyst.

There are also constraints to this process: for both oxidation and reduction to be thermodynamically feasible on a single photocatalyst, the band gap must straddle the oxidation and the reduction potentials. This means that only photons whose energy is larger than the band gap can be used to catalyze the target reactions. This implies a trade-off, a large band gap allows for flexibility and for a wider range of catalyzed reactions, as well as a large overpotential driving force, which is needed to drive the reaction rate, but it also means that a smaller part of the whole spectrum of light is used. Optimization and tuning of the band gap is commonly undertaken to achieve higher efficiency or production, and HPs are a material in which this can be done relatively easily. (Figure 1b).

Another important step in photocatalysis, as with all heterogeneous catalysis, is mass transport. Photocatalytic reactions are catalyzed on the surface and for that to happen reactants need to adsorb and products need to desorb. Product desorption is important both to prevent catalyzed back reactions and to free up catalytic adsorption sites for new reactants. An optimal heterogeneous catalytic system operates under reaction control (assuming safety conditions are met), so it is important to design reactor systems that allow the reaction to occur under mass transfer control. This is further discussed under reactor and system design (Section 5.2).

To better understand energetic constraints to the process, one can pinpoint six avenues for energy loss, identified by Stolarczyk et al. as follows:10

-

(1)

Below band gap photons. A loss that stems from the use of semiconductors. The sun emits light as a spectrum, from low energy IR to high energy UV. Photons with energy below the band gap cannot be absorbed, meaning that there is a cutoff below which all solar energy is intrinsically unused. Plasmon-induced hot electron transfer is one way to try to mitigate this loss. It can occur when a metal nanoparticle that has been deposited on a photocatalyst absorbs photons with lower energy than the band gap of the semiconductor is attached to. This can lead to an electron being injected into the CB of said semiconductor.11 Another of these strategies is upconversion–with the aid of mid band gap energy levels, electrons can be excited in a two-step process absorbing two photons with energy lower than the band gap, in a stepwise process. However, while upconversion increases energy utilization, the existence of energy states in the band gap can also be counterproductive as they can trap charges and act as recombination centers.12

-

(2)

Heat loss. Heat loss is the process of energy released as heat. It happens when a semiconductor photocatalyst absorbs an above-band gap photon, and then the corresponding electron is promoted to a level higher than the bottom of the CB: this is called a hot charge carrier. The electron can then collapse to the more stable lowest CB level and release the excess energy as heat.13

-

(3)

Charge recombination. Charge recombination is arguably the single most difficult problem in photocatalysis. Charge carriers are extremely short-lived. They often quickly recombine and release the energy either as heat (nonradiative recombination) or re-emit a photon (radiative recombination). Both types represent major energy losses in photocatalysis, and a lot of work is focused on trying to separate the charges as to avoid recombination.

-

(4)

Overpotential. Overpotentials, here defined as the potential differences between the CB edge and the reduction potential (CB-Ered) and between the VB edge and oxidation potential (VB-Eox), are another form of energy loss. A large overpotential can increase the charge transfer rate, decreasing the effect of charge recombination, but it does so at expense of extra energy loss. This is exacerbated by the need to use a larger band gap semiconductor to increase the overpotential, for the same pair of photocatalytic half-reactions.

-

(5)

Back reactions. In some cases, the products of photocatalysis are also susceptible to back reactions. Reverse reactions are also thermodynamically feasible in most cases, and some back-formation is to be assumed. This is more prevalent in the case of solar fuel production than for organic pollutant degradation.

-

(6)

Product separation and postprocessing. This is another aspect more closely related to solar fuel production. In photocatalytic setups where specific products are needed, there is the postprocessing energetic cost of separating them. In photocatalysis, both the reduction and the oxidation are catalyzed in the same reactor compartment, resulting in a mixed outlet stream, complete with unreacted precursors. This is a lesser concern for oxidative degradation, where in most cases the final products, due to their harmless nature, do not need to be separated from the reaction medium.

The many energy pitfalls in photocatalysis could potentially discourage uptake of it, but the big advantage is that solar energy is renewable, and that any amount that offsets its own energetic cost of production will be a net gain in the overall energy landscape. To understand how photocatalysis can be used in a productive way, and more specifically, how HPs can be used as effective photocatalysts, we must delve into the applications of the field.

It is also important to understand how to assess photocatalytic performance, that is their metrics. If the desired application is pollutant degradation, this is often reported as percentage concentration decrease, as a fraction of the initial concentration of the target compound. For all other photocatalytic applications, which are the main focus of this review, this is often reported as molar production, and then normalized by relevant conditions, such as mass, time or irradiation area. The result is that performance is often quoted in μmol g–1 h–1. It deals with amount of product (often low, so in the μmol range), and it is normalized by the time of the reaction and the mass of catalyst used. Variants of this include the time-normalized production (μmol h–1) and mass-normalized production (μmol g–1), but by far the most standard and uniformly used is the double-normalized value using μmol g–1 h–1. For surface-mounted catalysts, when evenly distributed, μmol m–2 h –1 has sometimes been used.

Another important metric is photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY). A lot of research on HPs has been derived from light-emitting diode (LED) applications, where the goal is for carriers to recombine radiatively to emit light. In these cases, PLQY should be as high as possible. However, in photocatalysis, there are competing effects that do not allow PLQY to be used as an effective metric. On one hand, having crystals of lower quality decreases PLQY and impairs photocatalytic performance; on the other hand, charge separation, in a heterojunction decreases PLQY but improves photocatalytic performance. It is important to understand these in context, and due to the evolution of the field from light emitting applications, especially on the synthesis side, PLQY is still very often quoted as a metric. We are choosing to report it at times, especially when it can be used as a matter of comparison for improved charged separation.

2.1. Hydrogen Production

The first route for photocatalytic hydrogen (H2) production was H2O splitting, which is the decomposition of H2O into H2 and oxygen (O2). However, HPs tend to be extremely unstable in the presence of moisture, so most advances in hydrogen production have been part of the process called acid splitting, consisting of the reactions in eqs 6–9. In 2017, Park et al. showed that methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3) can be kept in acid–base equilibrium in a hydroiodic acid (HI) aqueous solution, and can photoreduce HI into H2 and I3–,14 extending the large interest in HPs from photovoltaics to heterogeneous photocatalysis:

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

Wu et al. further developed this approach by mounting MAPbI3 on reduced graphene oxide (rGO), increasing evolution rate by 67 times and showing no decrease in activity after 200 h of operation.15 This highlights the advantage of complex catalyst architectures, further discussed in Section 4. Other improvements include the use of a mixed-halide perovskite with platinum cocatalyst nanoparticles (NPs) MAPbBr3–xIx/Pt. They describe a band gap funneling which drives the charges to the surface due to a halide gradient. The presence of Pt centers then helps decrease charge recombination, leading to 2605 μmol g–1 h–1 of H2 and no significant reduction of activity over 6 cycles and 30 h of operation.16 The effect of the halide gradient is illustrated in Figure 2 a, causing a narrowing of the band gap. Black phosphorene has also been used with MAPbI3 as an electron transport layer to achieve 3742 μmol g–1 h–1 and excellent stability, as seen in Figure 2 b, where activity is maintained even after 20 cycles and 1 month of storage.17

Figure 2.

(a) Halide gradient was proposed to drive the charges to the surface, leading to high levels of H2 production. Reproduced from ref (16). Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society. (b) Black phosphorene-MAPbI3 catalyst shows high production over 100 h of illumination, with performance maintained after 1 month of storage. Reproduced with permission from ref (17). Copyright 2019, Elsevier.

Recently, some work has been done on photocatalytic H2O splitting using HPs or composites thereof. The H2O splitting reactions are stated in eqs 10–12, with the oxidation and reduction reactions with the photoinduced charges (holes and electrons) and the full reaction represented. This is a much newer subset of this application, as HPs tend to be very unstable in the presence of water, but some researches are trying to find routes to make this possible. Garcia et al. used a MA2CuCl2Br2 catalyst to split H2O in the gas-phase with 100% humidity, achieving 24 h of operation (Figure 3a).18 They also showed that it is also achievable with traditional lead HPs, but with far lower production, at 0.11 μmol g–1 h–1. It appears that the superior stability of MA2CuCl2Br2 was the main driver for it. CsPbI3 and protonated graphitic carbon nitride were combined to split H2O in the liquid phase, reaching 242.5 μmol H2 g–1 h–1, which then increased over 3-fold when Pt was used as a cocatalyst.19 Interestingly, it achieved no loss of production over 4 cycles and 16 h, shown in Figure 3b. Further, some (low) levels of H2 production from water splitting are sometimes observed in experimental setups designed to reduce CO2:

| 10 |

| 11 |

| 12 |

Figure 3.

(a) Production of H2 (black) and O2 (red), showing less than stoichiometric O2 from H2O splitting. The formation of peroxides was ruled out, so the authors could not explain the disparity. No products were observed in the absence of water. Reproduced with permission from ref (18). Under a CC license, 2020, MDPI. (b) Production of H2 over four cycles for a lead halide perovskite, showing remarkable stability. Reproduced with permission from ref (19). Copyright 2021, Elsevier.

2.2. CO2 Reduction

Carbon valorization has been one of the main focuses of photocatalytic research, trying to convert CO2 to higher value chemicals, either CH4 for fuel use, or to chemical feedstocks such as CO or CH3OH. The CO2 reduction with photoinduced electrons needs to be balanced with an oxidation reaction with the photoinduced holes. In order to do this as cheaply as possible, the reductant is often water, which can also act as proton source for hydrocarbon formation. Some reports have used hole sacrificial agents, also called hole scavengers, to focus their research on the CO2 reduction. Hole sacrificial agents, such as triethanolamine, are substances that easily oxidize with the photoinduced holes, improving the lifetime of the photoinduced electrons for the reduction to take place. However, for the development of carbon valorization, it is key that the cost of the reductant does not compromise the economic profit of the process. Some of the most important reactions for CO2 reduction, as well as the water oxidation reaction which balances the process, are stated in eqs 13–22.20 All potentials are stated against the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) at pH 7:

| 13 |

| 14 |

| 15 |

| 16 |

| 17 |

| 18 |

| 19 |

| 20 |

| 21 |

| 22 |

When considering what CO2 reactions are possible, it is necessary to consider the limitations inherent to this process. First, for reaction on a single semiconductor photocatalyst, the band gap must straddle the oxidation and reduction potentials so both photoinduced electrons and holes are used. Larger overpotentials will drive kinetic rates and could change selectivity. Second, charge carriers are short-lived. This means that reactions which use large numbers of excited electrons are very difficult to achieve (for this reason, it is very rare to see direct reduction to C2 products). This pushes selectivity toward reactions with a lower number of electrons taking part. In several reactions, these two effects counteract each other and determining the balance is essential to explain behaviors observed in experiments. It has been shown that when charge transport layers are added to more effectively separate the charges, this shifts selectivity toward different products (higher number of electrons and higher potential).21 Another aspect to consider is the desorption of products, different products may have different desorption energies, leading to a slower freeing of catalytic sites, which can slow down the reaction rates overall.22

HPs have advantages such as a tunable band gap to straddle the CO2 reduction and H2O oxidation on the same photocatalyst. Still, currently, most state-of-the-art research focuses on complex catalyst architectures, which will be addressed later in this article. Nevertheless, Hou et al. have optimized CsPbBr3 quantum dot (QD) sizes for CO2 reduction and found that 8.5 nm size leads to lower charge recombination, reaching 20.9 μmol g–1 h–1.23 Other approaches have been taken to develop photocatalysts, Xu et al. have supported CsPbBr3 on graphene oxide (GO) to reduce CO2, using it as a charge transport layer, permitting better charge separation and achieving 23.7 μmol g–1 h–1. Using GO also moved the selectivity slightly from CO to CH4 as a product (35% to 33% on an electron basis). The advantage of GO is illustrated in Figure 4a, where electrons are drawn out of the photocatalyst.24 The authors claim that GO separates the photoinduced charges because it draws electrons from the perovskite crystal CB edge. Kumar et al. have also shown that the addition of Cu NPs to a transport layer like reduced GO (rGO) can further increase production and selectivity, with a CsPbBr3-rGO-Cu catalyst reaching 90% selectivity toward CH421 (Figure 4b)

Figure 4.

(a) Illustration of CsPbBr3 QDs deposited on high surface area graphene oxide, with a diagram showing the energy step the electrons take as they migrate to GO. Reproduced from ref (24). Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. (b) Photocatalytic production of CsPbBr3 nanosheets, and production with the addition of transport layers and metal cocatalyst. The selectivity shifts from CO to CH4. Reproduced from ref (21). Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society.

2.3. Organic Degradation

Organic degradation is a common use of photocatalytic materials, especially as part of a water purification process, and titania, with its good activity and high stability, tends to be a common choice. HPs, on the other hand, find less use due to their instability in water. The reactions that describe the organic degradation process mostly involve radical formation and subsequent reactions with the organic at hand. The most important reactions are given in eqs 23–25, where the superoxide and hydroxyl radicals do most of the decomposition:

| 23 |

| 24 |

| 25 |

HPs themselves were used first for photocatalytic degradation in 2017 by Gao et al. for decomposition of methyl orange, through the photocatalytic formation of hydroxyl and superoxide radicals.25 They showed that CsPbCl3 outperformed TiO2 and ZnO for the decomposition of methyl orange in water. A tin halide perovskite, CsSnBr3 has been used to degrade crystal violet dye in water, again through the formation of superoxide and hydroxyl radicals, reaching a final degradation figure of 73.1%, with no significant decrease in performance after 5 cycles (Figure 5a).26 Through a different mechanism, CsPbBr3 was used to directly oxidize 2-mercaptobenzothiazole (MBT) in hexane (Figure 5b), with adsorption of the reactant directly on the catalyst under a reaction mechanism represented in eq 26, showing HPs also have the potential to oxidize organic compounds directly.27 Though the materials described in this paragraph are quite different, this further emphasizes how versatile HPs have become over the past decade of research, both in their use and their nature:

| 26 |

Figure 5.

(a) Recyclability of CsSnBr3 for the degradation of crystal violet. Reproduced with permission from ref (26). Copyright 2018, John Wiley and Sons. (b) Scheme showing the direct oxidation of MBT, which does not rely on standard water-derived radicals, as the reaction is conducted in hexane. Reproduced from ref (27). Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society.

A silver–bismuth double perovskite, Cs2AgBiBr6, has been used to successfully degrade four different dyes, methyl orange, methyl red, and rhodamines B and 110, showing potential for a wide range of applications. It also dispenses with Pb, which could hinder the uptake of HPs for dye degradation in applications related to human consumption, such as water purification.28

2.4. Synthesis and Polymerization

One of the most interesting new emerging applications of HPs is its use in direct synthesis and polymerization reactions. If solar energy can be harnessed to directly facilitate the formation of C–C, C–O, and C–N bonds, it could significantly decrease the carbon footprint of the chemical industry.

Zhu et al. have shown that CsPbBr3 can catalyze the α-alkylation of aldehydes, promoting the formation of the C–C sp3 bond.29 Further, they demonstrated that this could be achieved under different experimental conditions, with different solvents. They also found that by tuning reactive conditions, they could alter selectivity for α-alkylation, sp3 C-coupling or even reductive dehalogenation, laying the groundwork for further organic synthesis. The mechanism for this was studied by Wang et al., who found that the reaction occurs through two intermediate ·C radicals which can then couple to form C–C bonds.30 Another approach has been to use the photogenerated charges instead of standard reductants or oxidizers, which is best exemplified by the work of Huang et al., who successfully oxidized benzylic alcohols into aldehydes on a TiO2/FAPbBr3 catalyst, achieving conversions of 63%.31 Further, CsPbI3 has been used to catalyze directly the polymerization of 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene into its polymerized form, PEDOT, illustrated in Figure 6. Chen et al. have used this polymerization to directly encapsulate perovskite QDs, leading to increased stability, which shows the potential of using the photocatalytic ability of HPs as a key part of their design and preparation.32

Figure 6.

Direct polymerization of 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene through oxidation, leading to encapsulation of CsPbI3 QDs with increased stability. Reproduced from ref (32). Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society.

The previous examples illustrate the diverse range of applications of HPs; however, the focus of this review will be primarily on photocatalytic CO2 reduction and H2 evolution. This is because in the area of dye degradation, a mature field already, HPs are outshone by more established and stable photocatalysts which can treat water without decomposing or adding extra risk with Pb2+. Organic synthesis is relatively new, and too broad in its application to generalize and benchmark operational conditions and figures of merit. We have as an aim to establish benchmarks for the field as well as to highlight strategies for the development of the most efficient photocatalytic systems, which is best explored through the study of solar fuel production, namely photocatalytic CO2 reduction and H2 evolution.

3. Halide Perovskite (HP) Photocatalysts and Developments

HPs have been well-known for at least a century but only in the 1990s they started to attract the interest of the scientific community. At the beginning of the 21st century, due to impressive optical and electronic properties, HPs were first researched for light-emitting devices and transistors.33,34 Then, in 2012, they started to be researched as sensitizing dyes and light absorption layers in solar cells, showing an outstanding potential to achieve solar-to-electricity conversion efficiencies above 15% with HP layers as thin as 330 nm.8,33,35,36 HPs showed performance comparable to the best III–V thin-film solar cells due to superior absorption cross section as well as small effective electron and hole masses due to strong s-p antibonding coupling.36 These superior optoelectronic properties were the catalyst to launching the extensive research of HPs. Further exploration of HPs revealed several other outstanding properties and qualities such as tunable band gap, shallow defect states, and cost-effective synthesis, making them excellent candidates for electronic and optoelectronic devices, such as solar cells, light-emitting diodes, gas sensors, photodetectors, and lasers. Recently, HPs have also been investigated for photocatalysis. In 2016, Park et al.14 demonstrated for the first time solar-driven H2 evolution on HPs. They developed a strategy for photocatalytic HI splitting using MAPbI3. This work prompted widespread research and application of HPs in photocatalysis.

3.1. Structure and Properties

Since 2016, a variety of HP materials have been produced that could find application in photocatalysis. All HP materials share a common crystalline structure ABX3 where A is a monovalent cation, B is a divalent cation and X is a halide ion (Figure 7a). Applying diverse synthesis strategies, a range of modified HP structures can be obtained. As a start, by engineering the A site, organic–inorganic perovskites can be produced, where A is an organic cation such as methylammonium (MA+, CH3NH3+) or formamidinium (FA+, (NH2)2CH+). For example, MAPbBr3 QDs with a size of 6 nm were prepared by hot injection of methylammonium bromide (MABr) and PbBr2 solutions into a preheated octadecene solution of oleic acid and octyl ammonium bromide.37 The obtained products had a blue shift of ∼16 nm in comparison with the bulk materials due to quantum size effects and a photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of ∼20% as well as long stability for more than 3 months (dispersed in toluene). Moreover, the optical absorption properties and the photoluminescence (PL) properties of MAPbBr3 QDs can be tuned by varying the halide content, as it modifies the band gap energy.38

Figure 7.

(a) Crystalline structure of ABX3 halide perovskites. Reproduced with permission from ref (43). Copyright 2017, Springer Nature. (b) Schematic representation of the different dimensionalities of HPs, from 0D to 3D ones. Reproduced with permission from ref (44). Copyright 2020, John Wiley and Sons.

All-inorganic HP materials can be produced, where A is an inorganic cation such as cesium (Cs+) or rubidium (Rb+). Pioneering work on the preparation of all-inorganic HPs QDs was published by the Kovalenko group (discussed in more detail in Section 3.2.1).39 All-inorganic HPs are usually significantly more stable than organic–inorganic HPs with regards to temperature. Moreover, their optical properties can still be tuned by varying their halide content. Lead-free HPs, as its name suggests, avoid the use of toxic lead cations (Pb2+) and employ alternative cations such as tin (Sn2+), bismuth (Bi2+) or germanium (Ge2+) or cation pairs like silver (Ag+) and bismuth (Bi+) forming double HPs. The most studied examples of lead-free HPs are CsSnCl3 and FASnI3 for single HPs and Cs2AgBiX6 for double HPs.28,40−42 The substitution of Pb can result in nontoxic HPs but may lead to low stability and/or poor optoelectronic properties.

HPs can be obtained in various dimensionalities, such as 0D, 1D, 2D and 3D as a result of either different levels of corner sharing between MX6 octahedral anions or different crystal shapes. For example, 0D HPs show separated metal halide octahedral anions or metal halide clusters and 3D HPs show multiple corner-sharing MX6 octahedra (Figure 7b). Various low-dimensional HPs including 0D nanostructures (nanocrystals, quantum dots, and nanoparticles), 1D nanostructures (nanotubes, nanowires and nanorods) and 2D nanostructures (nanosheets and thin-films) have been reported in literature. Such a dimensionality change from 3D to low-dimensional structures leads to different optical and electronic properties such as band gap, density of states (DOS), and luminescence. A well-known example is CH3NH3PbBr3 NPs, where the change from bulk 3D crystals to 0D quantum dots results in a blue shift of the maximum of light absorption from 546 to 527 nm, due to particle-size quantum confinement.37

Due to their superior physical, chemical and optoelectronic properties such as tunable band gap, long charge-transport diffusion, high light absorption coefficients, and good defect tolerance, HPs have been considered promising candidates for photocatalytic applications.45,46 At the moment, HPs have been utilized in several photocatalytic applications such as CO2 reduction, H2O splitting, dye degradation, and organic synthesis.18,32,47 The universal features of HPs are determined by many parameters such as size, dimensionality (0D, 1D, 2D, and 3D), and chemical composition. The morphology, optical and electronic properties of HPs can easily be finely adjusted by controlling the reaction conditions such as choice of precursors, concentration, reaction temperature, and time, as we will discuss in the following section.

3.2. Preparation Methods and Photocatalytic Properties

The preparation of HPs is mainly carried out using bottom-up approaches, following either solution, gas phase or mechanochemical methods. The most studied solution-based methods are the hot-injection and ligand-assisted reprecipitation. For gas-phase methods, the main approach is chemical vapor deposition (CVD). Mechanochemical synthesis is a novel approach for HP preparation, where high-energy ball milling directly transfers kinetic energy through grinding balls to precursors which facilitates chemical reaction.

3.2.1. Bottom-up Methods

Solution-based methods have been a preferred method for the fabrication of well-defined colloidal HP nanocrystals (NCs) in a controllable way. This approach can be used to produce high-quality and well-defined morphologies, such as 0D QDs, 1D nanowires, or 2D nanosheets.48 Since the publication of the hot-injection method by the Kovalenko group, this is one of the most applied methods for synthesis of all-inorganic HP QDs.39 For example, in a two-step approach, monodispersed colloidal CsPbX3 NCs (4–15 nm) were synthesized. First, a cesium oleate solution was obtained by decarbonization and drying of Cs2CO3 with oleic acid in 1-octadecene at 150 °C. This was followed by injection of PbX2 solution in 1-octadecene with oleic acid and oleylamine at 140–200 °C. Upon injection, HP QDs were formed immediately, and the reaction mixture was cooled down after 5 s (Figure 8a–e).

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of (a) the hot-injection and (f) ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) methods. Reproduced with permission from ref (54). Copyright 2021, John Wiley and Sons. Colloidal perovskite CsPbX3 NCs (X = Cl, Br, I) show size- and composition-tunable bandgap energies in the entire visible spectral region with narrow and bright emission: (b) optical images of colloidal solutions in toluene under UV irradiation (λ = 365 nm); (c) PL spectra upon excitation of λexc = 400 or 350 nm for CsPbCl3; (d) optical absorption and PL spectra; (e) time-resolved PL decays for all samples in (c) except CsPbCl3. Reproduced fromref (39). Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society; (g) optical images of MAPbX3 QDs under ambient light and UV lamp (λ = 365 nm); (h) PL emission spectra of MAPbX3 QDs; (i) CIE color coordinates corresponding to the MAPbX3 QDs (1–9, black circle), pc-WLED devices (blue lines), and NTSC standard (bright area); (j, k) schematic diagram and EL spectra of pc-WLED devices using green emissive MAPbBr3 QDs and red emissive rare earth phosphor KSF. Reproduced from ref (38). Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society.

Metal halide salts are often used as a source of both cations and anions which offers limitations to control stoichiometry. To overcome this issue, Liu et al. designed the “three-precursor” hot-injection approach for the synthesis of CsPbX3 (X = Cl, Br, or I) NCs.49 The novelty was that instead of conventional PbX2 (X = Cl, Br, or I) salts, separate NH4X (X = Cl, Br, or I) and PbO were utilized as halide and lead sources, respectively. Guo et al. went further and elaborated a new strategy to enhance CO2 photocatalytic reduction, by modifying the halide ratio in the CsPb(BrxCl1–x)3 structure.50 CsPb(BrxCl1–x)3 were prepared by hot injection with different Cl/Br molar ratios. The photocatalytic activity results of the CsPb(BrxCl1–x)3 (where x = 1, 0.7, 0.5, 0.3, 0) revealed that CO and CH4 production yields are notably influenced by the Cl/Br molar ratios in the structure. It was experimentally demonstrated that the photocatalytic activity of CsPb(Br0.5Cl0.5)3 was the highest, and the total amount of generated products in a 9 h experiment was 875 μmol g–1 with a high selectivity of 99% for CO and CH4.

Although the desired ion stoichiometry can be achieved using the “three precursors” method, their reactivity under these reaction conditions and method is low. To overcome this, a novel hot-injection method was developed by Creutz et al. They injected trimethylsilyl halides into a solution of metal acetate precursors (i.e., silver acetate, cesium acetate, and bismuth acetate) at 140 °C. The solution was then dissolved in 1-octadecene, oleic acid and oleyamine, which triggered immediate nucleation and growth of NCs.51 Wang et al. demonstrated that organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite methylammonium lead bromide (MAPbBr3) NCs can also be stabilized in aqueous HBr solution photocatalytically producing H2 under visible light. Moreover, they combined MAPbBr3 NCs with Pt/Ta2O5 and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrenesulfonate NPs, which improved photocatalytic activity. The produced heterostructure demonstrated a 52-fold increase of H2 evolution compared with pristine MAPbBr3.52

In addition to the hot-injection method, ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) technique is often used. The basic principle of this method is the dissolution of selected ions in a solvent until an equilibrium concentration is reached, followed by transfer of the solution to a nonequilibrium supersaturation state. The process is called ligand-assisted reprecipitation method if it involves stabilization ligands. This method proved its effectiveness by Zhang et al. in 2015 in the synthesis of organic–inorganic perovskite NCs. They prepared a precursor solution by dissolving PbBr2 and MABr salts in alkyl amines, carboxylic acids, and dimethylformamide. This solution was then dropped into toluene under vigorous stirring resulting in the formation of colloidal MAPbBr3 NCs, which had a PLQY around 70% at room temperature (Figure 8 f-k).38 Moreover, Dai et al. combined traditional ligand-assisted reprecipitation synthesis with spray pyrolysis method to produce cubic-shaped MAPbBr3 NCs with narrow size distribution around 14 nm.53 Specifically, MABr, PbBr2, oleic acid, octylamine, and dimethylformamide were sprayed into toluene, providing a large contact surface area between two solutions and homogeneous mixing, which led to the formation of well-defined cubic-shaped MAPbBr3 NCs.

To summarize, hot injection and LARP techniques are key methods for the preparation of perovskite NCs and QDs. The hot-injection method usually requires the absence of air and moisture and need to be conducted at elevated temperatures (up to 200 °C) allowing a more precise control of NC morphology compared to the LARP method. On the other hand, LARP is performed at lower temperatures and does not require specific equipment and processing conditions. However, due to the presence of polar solvents, stability of the as-prepared NCs is relatively low.

In addition to solution-based methods, HPs can be synthesized by gas-phase methods such as CVD. This method offers numerous benefits such as uniformity, scaling, and control of thickness. In 2014, Ha et al. synthesized the first organic–inorganic lead HP nanoplatelets by CVD.55 First, PbX (X = halide) plates were synthesized on top of muscovite mica by van der Waals epitaxial growth. Then, by thermally intercalating methylammonium halides, PbX was converted to MAPbX3 HPs. The size of the obtained MAPbX3 was in the range 5–30 μm with an electron diffusion length exceeding 200 nm. Moreover, Zhang et al. prepared CsPbBr3 and CsPbBrxCl3-x hemispheres with smooth surface and regular geometry on a silicon substrate by CVD. It was observed that surface morphology changed with the Cl/Br ratio. With increasing Cl content, the surface of CsPbX3 hemispheres became rougher due to vacancy defects. The HPs with hemispherical geometry provided an ideal platform for lasing and polarization development.56

A new milestone appeared in 2018 when the Kovalenko group prepared HPs by wet ball milling. As starting materials, they first prepared and used CsPbBr3 or FAPbBr3. Moreover, they showed that CsBr or FABr and PbBr2 precursors can be utilized for perovskite formation via wet ball milling. A zirconia bowl with 23 zirconia balls was loaded with HP bulk crystals or a mixture of powder precursors and mesitylene as a solvent and oleylammonium halide as a ligand. The obtained products were analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealing HP QDs with narrow size distribution and bright green luminescence under UV light.57

Recent findings by our (the Eslava) group shed light on the importance of choosing the right ball-milling parameters to control the resulting HP morphologies. Kumar et al. prepared CsPbBr3 of different morphologies such as nanorods, nanospheres and nanosheets, by simply choosing different milling times, zirconia ball sizes, and Cs precursors in a planetary ball mill. For example, using CsOAc as a Cs precursor resulted in nanorods of different aspect ratio depending on the milling time and ball size, but CsBr resulted in nanosheets. All these morphologies showed orthorhombic CsPbBr3 phase and photoluminescence emission at 530 nm upon 365 nm excitation.21 Kumar et al. also demonstrated the mechanochemical synthesis of double-perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 nanosheets in a planetary ball mill using as precursors all the bromide cations.58 Both CsPbBr3 and Cs2AgBiBr6 nanosheets were tested for photocatalytic conversion of CO2 and H2O vapors under 1 sun of simulated sunlight, producing a mixture of CO, CH4, H2, and O2, showing a higher selectivity for CO production (reaching 1.5–2.3 μmol CO g–1 h–1).

Furthermore, the Biswas group demonstrated mechanochemical synthesis of halide perovskites with different dimensionalities: 3D CsPbBr3, 2D CsPb2Br5, 0D Cs4PbBr6, 3D CsPbCl3, 2D CsPb2Cl5, 0D Cs4PbCl6, 3D CsPbI3, and 3D RbPbI3.59 They showed the importance on the choice of precursors for desired stoichiometric ratios and the possibilities on postsynthetic structural transformations to different dimensionalities. This group also demonstrated mechanochemical synthesis of Pb-free Ruddlesden–Popper-type layered Rb2CuCl2Br2 perovskite using a few drops of dimethylformamide solvent as a liquid assistant, achieving a band gap around 1.88 eV and a band-edge PL emission at 1.97 eV at room temperature.60 In another work, they demonstrated the mechanochemical synthesis of novel Pb-free layered RbSn2Br5. By tuning the halide ratio, the 3.20 eV band gap of RbSn2Br5 changed to 2.68 eV (RbSn2Br4I) and 3.36 eV (RbSn2Br3Cl2). The layered RbSn2Br5 showed thermal stability up to 205 °C while maintaining crystalline stability at ambient conditions for 30 days. The optical properties and charge-carrier recombination dynamics were further studied. It was confirmed that recombination at 298 and 77 K takes place through the band-edge and shallow states with average lifetimes in the range of few nanoseconds.61

3.2.2. Halide Perovskites-Based Composites

Pristine HPs are highly sensitive to moisture, light, and temperature owing to their low formation energy. Their instability limits their wider utilization in photocatalysis. Therefore, one of the strategies employed to overcome these drawbacks and further improve optical and charge-separation properties is the preparation of HP-based heterostructures. Raja et al. demonstrated the preparation of HP-based nanocomposites by embedding CsPbBr3 nanocubes, nanoplates, and nanowires in hydrophobic macroscale polymeric matrices such as polystyrene. HPs were prepared by the conventional hot-injection method and further blended with the polystyrene in toluene. After mixing and sonicating, the solution was spin-coated onto coverslips. It was stated that because of the high viscosity it was challenging to obtain uniform thin-film morphology. The PLQY of the HPs based nanocomposite remained stable during 4 months of immersion in water. Moreover, the photostability of the as-prepared nanocomposite was improved upon encapsulation, achieving 1010 absorbed photons per QD at 105 W cm–2 excitation flux.62

Schuenemann et al. prepared a CsPbBr3/TiO2 nanocomposite by a low-temperature wet impregnation method. TiO2 (P25) was thoroughly mixed with a dimethyl sulfoxide solution containing CsPbBr3 precursors. The resultant substance was dried for 4 h at 60 °C to evaporate the dimethyl sulfoxide and crystallize CsPbBr3. The prepared nanocomposite demonstrated enhanced visible-light selective photocatalytic oxidation of benzylalcohol toward benzaldehyde as well as good morphological stability and crystal structure.63 Chen et al. demonstrated a novel strategy for improving the photocatalytic reduction of CO2 by immobilizing Ni metal complex Ni(tpy) on the surface of CsPbBr3 by electrostatic interaction. CsPbBr3 was prepared by the traditional hot-injection method, followed by substitution of surface organic ligands for PF6–. The Ni metal complex further electrostatically interacted with PF6– on the HP surface, producing a stable hybrid structure CsPbBr3–Ni(tpy). The Ni metal complex immobilization on CsPbBr3 was reported to be critical for highly efficient CO2 reduction, because it was assigned to work as an electron sink, rapidly accepting photoexcited electrons from the CB of CsPbBr3. The photocatalytic reduction of CO2 by CsPbBr3–Ni(tpy) exhibited 1724 μmol g–1 of CO/CH4, which was almost 26 times higher than that of pristine CsPbBr3.64

Mechanochemical synthesis approaches have also been developed for HP composites. Kumar el al. demonstrated the successful preparation of composites of CsPbBr3 nanosheets and Cu-loaded reduced graphene oxide (Cu-rGO) following a solvent-assisted mechanochemical synthesis in a planetary ball mill that ensured proper mixing of reactants in the presence of large rGO flakes (1–100 μm).21 TEM characterization demonstrated the growth of HP on Cu-rGO, moreover showing templating effects and intimate contact between phases. The same approach was also demonstrated for double-perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 composites with Cu-rGO.58 TEM characterization also demonstrated intimate contact between phases and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy presented features assigned to Ag–O and Bi–O bonding between the HP and rGO. The formation of HP composites with Cu-rGO drastically boosted the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 and H2O vapors under 1 sun of simulated sunlight. For example, CsPbBr3–Cu-rGO composites achieved 12.7(±0.95) μmol CH4 g–1 h–1, 0.46(±0.11) μmol CO g–1 h–1, and 0.27(±0.02) μmol H2 g–1 h–1. Importantly, the presence of Cu-rGO enhanced the hydrophobic character of the HP-based composite and ensured charge separation. These effects boosted the reusability of the composite for photocatalytic reactions, so 90% of their photocatalytic production rate was retained over three consecutive cycles.

3.2.3. Halide Double Perovskites and Halide Perovskite Derivatives

As mentioned in Section 3.2.2, HPs are known for their sensitivity to light, moisture, and temperature. In addition to that, the vast majority of HPs studied in literature contain Pb in the B-site. Pb2+ is considered a source of toxicity and an environmental hazard.65−67 Recently, scientists have developed new approaches to tackle the aforementioned challenges. These approaches include, but are not limited to, the reduction of crystal defects introduced during synthesis, structural doping, and the use of efficient charge transport layers to reduce charge recombination.68,69 Even though these methods lead to better stability, the challenges related to the presence of Pb in the structure are not solved. Attempts to replace the divalent Pb cation with Sn2+ or Ge2+ have been conducted. However, the 5s orbitals of these candidates can further decrease the material stability.70

Recently, the idea of synthesizing halide double perovskites has been explored as a green alternative to lead-based perovskites. The process entails designing materials where two Pb atoms are replaced either with one monovalent and one trivalent cation (A2B+B3+X6) or with one tetravalent cation (A2B4+□X6) and a vacancy (□). This method further broadens the list of potential cations to replace lead. For example, Cs2AgBiBr6 nanocrystals have demonstrated remarkable stability at 100, during prolonged illumination, and in humid conditions. Its stability, suitable band structure, good light absorption properties, and long carrier recombination lifetime allowed its use as a photocatalyst for CO2 reduction reactions.58,71 Computationally, researchers have also identified structures like Cs2NaBiCl6, Cs2AgInCl6, (MA)2AgBiBr6, and Cs2AgBiCl6 as potential photocatalysts.72−74

In addition to double perovskites, researchers have identified other possible lower dimensional halide perovskite derivatives. An example would be of the form A3X9 as demonstrated in Figure 9. Different atomic combinations have already been synthesized and tested including Cs3Sb2I9, Cs3Bi2I9, MA3Bi2I9, and Rb3Sb2I9. For example, Cs3Bi2I9 has shown good light absorption in the visible range with a bandgap of 1.9–2.2 eV depending on the synthesis route. It was also found to have good thermal stability up to 425 as well as light stability to around 120 days.75,76 Bhosale et al. performed a comparative study between three bismuth iodide perovskites having Cs, Rb, and MA in the A-site. The group synthesized the three perovskites using an ultrasonication method and deduced that Cs3Bi2I9 showed a significantly higher yield of CO than its counterparts due to superior charge transfer.77

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of a perovskite crystal (1–1–3) and its derivatives after replacing two divalent B-site cations with (2–1–6) a tetravalent cation, (3–2–9) a trivalent cation, and (2–1–1–6) a tri- and monovalent cation. The string of digits above the structures refers to the vacancy order of the ions, respectively. Reproduced from ref (78). Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society.

4. Key Factors Influencing the Performance

Several material-related factors highly influence the photocatalytic performance of HP photocatalysts such as stability, band structure, morphology, size, charge separation, adsorption capacity, and selectivity. In this section, we will have a closer look at each of those and highlight its role in the photocatalytic process.

4.1. Stability

Stability has an essential role in liquid and gas-phase photocatalysis involving HPs. Although all-inorganic HPs have higher thermal stability than organometallic structures, their utilization is still a challenge due to their highly polar ionic structure. Polar solvents such as water are harmful to HPs, and in order to maintain stability and enhance photocatalytic performance, several approaches have been developed. One of the most promising methods to enhance the stability of HPs is encapsulation, which, in addition to stability, can improve photocatalytic performance. Encapsulation of HP structures was first demonstrated with polymer materials, providing hydrophobic protection. The most common polymers which were used for the protection of HPs are polystyrene and poly(methyl methacrylate).79−81

In 2016, Wang et al. engineered a monolithic superhydrophobic polystyrene fiber membrane with CsPbBr3 QDs by a one-step electrospinning process. The as-prepared composite structure exhibited high quantum yields (∼91%) and kept nearly 80% fluorescence after 365 nm UV-light (1 mW cm–2) illumination for 60 h.82 Further, Ma et al. embedded CsPbBr3 in polystyrene and poly(methyl methacrylate) by an effluent-free microfluidic spinning technique, producing 1D–2D microreactors which continuously synthesized embedded composite material. The CsPbBr3/ polystyrene and poly(methyl methacrylate) nanocomposite demonstrated tunable emission between 450 and 625 nm and great PL stability against water vapors and UV radiation.83

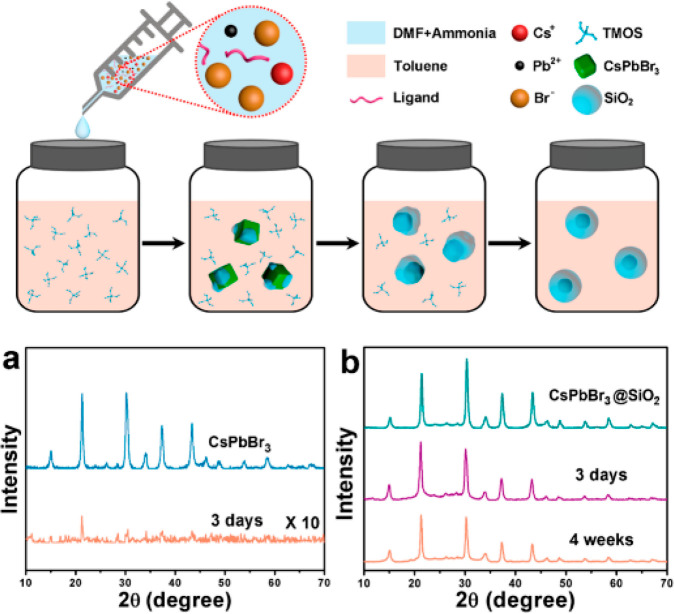

The coverage of HP surfaces with various oxides (semiconductors and insulators) has also been studied. Zhong et al. prepared one-pot monodisperse CsPbBr3@SiO2 core–shell NPs. The generation of SiO2 oligomers led to the growth of a SiO2 shell around CsPbBr3 in the presence of ammonia and tetramethyl orthosilicate (Figure 10). Various parameters such as reaction temperature, precursor species, pH value as well as CsPbBr3 and SiO2 concentrations determined the successful core–shell formation. As a result, CsPbBr3@SiO2 demonstrated higher long-term stability against water vapors and ultrasonication in comparison with pristine CsPbBr3 NCs. (Figure 10a,b)84 Impregnation of CsPbBr3 in TiO2 is considered extremely promising since TiO2 itself can facilitate photocatalytic activity by proper band alignment. Xu and co-workers coated CsPbBr3 NCs with amorphous TiO2. The TiO2 shell around HPs was able to suppress the intrinsic radiative recombination, providing facilitated transport of photoexcited electron–hole pairs as well as enhanced photocatalytic activity due to improved CO2 adsorption. A combination of the above-mentioned effects boosted photocatalytic activity up to 6.5 times and stability was extended up to 30 h.85

Figure 10.

Proposed formation of CsPbBr3@SiO2 core–shell NPs, and XRD pattern highlighting stability of (a) CsPbBr3 NCs and (b) CsPbBr3@SiO2 core–shell NPs. Reproduced from ref (84). Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society.

Carbon-based materials have been found to be beneficial for enhancing the stability of HPs. Ou et al. demonstrated the preparation of CsPbBr3 QDs on NHx-rich porous g-C3N4 nanosheets by a self-assembly method that forms the composite via N–Br interaction. The formation of N–Br bonds led to enhanced charge separation, longer lifetime of photoexcited electron–hole pairs, and provided an alternative way for surface passivation reasonably improving stability. The CsPbBr3 QDs/g-C3N4 nanocomposite exhibited enhanced photocatalytic activity toward reduction of CO2 to CO, which was 15 times higher than the activity of pure CsPbBr3 QDs. Moreover, the nanocomposite was endowed with outstanding stability in acetonitrile/water and ethyl acetate/water systems.86

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) have been similarly employed to improve and maintain the stability of HPs. Wu and co-workers managed to enhance the stability of MAPbI3 QDs by coating them with Fe-based MOF PCN-221[Fex(x = 0–1)] following a sequential deposition route. The close contact between QDs and the Fe catalytic sites in the MOF enabled the swift transfer of photoexcited electrons, improving the photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Namely, the photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO and CH4 was 38 times higher than that of PCN-221(Fe0.2) alone, using H2O vapor as the electron source. Moreover, the stability was significantly improved—no detected changes in crystalline properties for over 80 h.87

In addition, HPs become unstable upon heating and/or UV irradiation. A reported approach to mitigate these issues is the preparation of HP-based nanocomposites with more thermally stable materials and/or photostable materials. Gao and co-workers produced CsPbBr3 QDs assembled into silicon oxide via a one-pot nonpolar solvent synthesis method at a nanoscale-particle level. CsPbBr3@SiO2 nanocomposites exhibited superior photostability for up to 168 h of UV irradiation as well as higher stability against moisture for up to 8 days, while maintaining a high PLQY of 87%.88 The relatively low formation energy was assigned to be responsible for the internal defect formation. Therefore, doping with divalent metal cations with a smaller radius than Pb may result in contraction of the M–X bond length and higher formation energy and hence stability. Zou et al. demonstrated doping of Mn2+ ions in CsPbX3 (X= Cl, Br, and I) QD lattices. The prepared QDs were thermally stable up to 200 °C temperature under ambient air conditions and maintained the PL intensity for three cycles.89

It is important to emphasize that a lot of the developed strategies to increase the stability of HPs, including some of the ones here detailed, such as encapsulation in insulating SiO2, work well in the field of light-emitting diode devices, where the goal is radiative recombination upon illumination. In photocatalysis, the charges need to be extracted and some of these approaches would severely hinder the charge extraction.

4.2. Electronic Band Structure

HPs are well-known for having a widely tunable band gap. The band gap energies of HPs range from UV to near-infrared wavelengths. Such broad band gap energy range is determined by various parameters including the halide composition, crystal size, and crystalline phase. The electronic band structure is an important feature when designing heterostructures, since adequate band alignment facilitates the separation of photoexcited electrons and holes and further promotes photocatalytic activity. HPs can be prepared in different dimensions such as 0D NCs or QDs, 1D nanowires, and 2D nanosheets. Smaller crystal dimensions can increase the band gap energy due to quantum confinement effects.

The nature of the band gap in HP materials was recently studied by first principle calculations. Yuan et al. analyzed various electronic structures of ABX3 perovskites where A = CH3NH3, Cs; B = Sn, Pb; X = Cl, Br, I by density functional theory (DFT) using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange–correlation functional and the Heyd–Scuseria–Ernzerhof (HSE) hybrid functional. They confirmed that the valence band maximum (VBM) results from antibonding hybridization of B s and X p states and the conduction band minimum (CBM) from π antibonding of B p and X p states. It was further found that the contribution of the A site toward VBM or CBM is insignificant, but it affects the lattice constants that impacts band gap width. The CBM gradually decreases upon halide exchange according to the Cl → Br → I scheme, whereas the VBM depends on the atomic orbital energy of X p site and bond length of B–X. The robust antibonding in Bs–Xp state is considered as more delocalized than the X p alone, which results in smaller hole effective mass and larger hole mobility.90

The electronic structure of the semiconductor is determined by two important physical parameters: binding energy of the exciton (R*) and reduced effective mass (μ). Galkowski and co-workers explored electronic properties of methylammonium and formamidinium lead trihalide perovskite, namely MAPbI3, MAPbBr3, FAPbI3 and FAPbBr3 by means of magneto-optical absorption spectroscopy. They demonstrated that R* and μ parameters can be directly determined at low temperatures (2 K) by measuring excitonic states in the magnetic field and Landau levels of the free carrier states. The results of the work emphasized the efficiency of magneto-optical absorption spectroscopy toward determination of R* and μ parameters at low temperature. In addition, a relationship between R*, μ and material band gap was observed.91

The same method was used to determine R* and μ parameters in all-inorganic HPs. Baranowski and co-workers applied magneto-optical absorption spectroscopy to CsPbCl3 to identify them. A CsPbCl3 perovskite film was grown on a muscovite mica substrate using a CVD method. Applying low-temperature transmission spectroscopy in pulsed magnetic fields up to 68 T resulted in direct observation of R* and μ parameters. The observed values were in good agreement with experimental and calculated DFT values.92

Li et al. have observed enhanced multiple exciton generation efficiencies in intermediate-confined FAPbI3 NCs. They demonstrated higher multiple exciton generation efficiencies (up to 75%) and low- multiple exciton generation threshold energies to 2.25 eV by dimensional tuning of FAPbI3 NCs. It was calculated that band gap energies increased from 1.5 eV in the bulk to 1.7 eV for NCs with an edge length of ∼8 nm.93 Vashishtha et al. prepared thallium-based HPs Tl3PbX5 (X= Cl, Br, I). Varying colloidal methods, spheroidal NCs and nanowires were produced. It was shown that their band gap can be tuned by halide substitution and creating nanocomposites that strongly absorb in the range between 250 and 450 nm. Moreover, Tl3PbBr5 NCs exhibited a quantum confinement effect upon size tuning.94 Dou et al. developed a solution-phase growth strategy of large-size, square-shape (C4H9NH3)2PbBr4 single-crystalline nanosheets. These nanosheets revealed intriguing features such as structural relaxation and vivid PL compared to the bulk material. The band gap energies ranged from 2.97 eV for the bulk material to 3.01 eV for the nanosheets, indicating lattice expansion. Furthermore, by altering nanosheet thickness and composition, natural color tuning was achieved.95

Both compositional and dimensional engineering are promising approaches to modify the band gap energies of HPs. Tuning the halide (X) composition and developing mixed-halide perovskites is an accessible approach to obtain HPs of different band gap energies. For example, Akkerman et al. established a halide-reverse strategy for the synthesis of CsPbBr3 NCs along with anion exchange reactions. Preparing CsPbBr3 NCs by hot-injection method, they achieved NCs with a band gap of 2.43 eV. Upon halide substitution (Br to Cl), CsPbCl3 NCs exhibited a gradually increased band gap up to 3.03 eV. Further halide replacement to I resulted in the decreased band gap to 1.88 eV. The anion exchange process is considered a versatile technique for gaining novel structural and optical properties of CsPbX3 NCs (X = Cl, Br, I).96

The halide migration-induced phase segregation is another efficient way to modify the band gap of HPs. In 2018, Zhou et al. demonstrated a two-step CVD preparation method of mixed-halide FAPb(BrxI1–x)3 NPs. First, FAPbI3 NPs were prepared, and then they were treated with FABr vapors. Upon FABr vapor treatment, Br– replaced I– from the Br-rich site on top to the I-rich site at the bottom. Once the substitutional process was completed, a specific gradient band gap structure appeared, ranging from 2.29 eV for FAPbBr3 to 1.56 eV for FAPbI3 (Figure 11). It was revealed that in such a gradient band gap structure, photogenerated carriers were shuttled to the low band gap edge by energy funneling effects.97

Figure 11.

Specific gradient bandgap structure in FAPbX3. PL spectra under continuous illumination of materials with different thicknesses (a) 58 nm, (b) 239 nm, and (d) 1.3 μm (λexc = 405 nm). PL intensity of the two peaks of the medium thickness NP (c) as a function of the illumination time and (e) a schematic diagram of the gradient energy band structures. Reproduced with permission from ref (97). Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH.

The band gap energies of HPs also strongly depend on the present phase. Usually, thermal effects are responsible for phase transitions, resulting in the reconstruction of the crystals to another space group (not always a HP phase). Studying the effects of the temperature on band gap energies and emission decay dynamics of MAPbI3, MAPbBr3, and FAPbBr3 using time-resolved PL spectroscopy, Dar and co-workers observed an extraordinary PL behavior. Two distinct emission peaks appeared in MAPbI3 and MAPbBr3 under low temperature (less than 100 K) while FAPbBr3 showed a single emission peak. A deeper analysis revealed an unusual blueshift of the band gap with increasing temperature from 15 to 150 K. The blueshift originated upon stabilization of the VB maximum and by the coexistence of MA-ordered and MA-disordered orthorhombic domains. The FAPbBr3 possessed only a single emission feature due to a low difference between ordered and disordered FA orthorhombic domains [∼10 to 20 meV in FAPbBr3 versus ∼80 to 90 meV in MA perovskites].98

4.3. Size and Morphology

Morphological and structural properties have a strong influence on the photocatalytic activity of HPs. HPs can be prepared as nanocrystals, nanoparticles, nanofibers, nanoplates, thin-films, and periodic structures (periodical lines, hierarchical structures, and patterned single crystals). 0D HPs possess high quantum yield, narrow-band emission, and defect-tolerant band gap and, thus, they have great potential for optoelectronic and photocatalytic applications. The existing preparation methods allow rapid fabrication of sophisticated 0D HPs with a large area in a cost-effective way.23,99,100 Moreover, 0D HPs can be coupled with other nanoscale materials leading to enhanced photocatalytic performances. Pioneering work on the preparation of 0D HPs was performed by Schmidt et al.37 MAPbBr3 QDs with an average size of 6 nm were fabricated using an ammonium bromide with organic ligand chains. It was shown that the stability of the as-prepared materials is maintained for more than three months. Further, as previously discussed, Kovalenko and co-workers also prepared all-inorganic CsPbBr3 QDs by hot-injection method. The morphology and size of QDs were tuned between 4 and 15 nm varying the reaction conditions such as reaction temperature and choice of halide precursors. The sizes and composition of CsPbBr3 QD strongly affected the PL properties of QDs.39

1D HPs have one microscopic and two nanoscopic dimensions. Furthermore, due to the intrinsic high aspect ratio, 1D HPs are endowed with a two-dimensional quantum confinement effect. The fabrication of 1D HPs and 0D HPs are alike, where different parameters such as temperature, time, mixing speed, and precursor concentration determine the growth of the nanostructures. Aharon et al. explored a low-temperature synthesis of HP nanorods. The HP nanorods demonstrated a narrow size distribution and a strong PL emission. It was shown that the shape and size of the nanorods were not affected by the halide ratios and the average dimensions were measured to be 2.25 ± 0.3 nm in width and 11.36 ± 2.4 nm in length. Moreover, the band gap energies were simply adjusted by halide composition ranging from 1.9 eV for iodide to 2.26 eV for bromide.101 The preparation of all-inorganic HPs nanowires was demonstrated by Zhang and co-workers through fabricating CsPbX3 (X = Br, I) nanowires using a catalyst-free, solution-phase synthetic method. The uniform growth of single-crystalline, orthorhombic CsPbX3 nanowires of approximately 12 nm in width and 5 μm in length was observed after 40–90 min of reaction (Figure 12). Further, analysis of optical properties showed that CsPbBr3 and CsPbI3 nanowires have PL and temperature-dependent PL. Additionally, CsPbI3 nanowires exhibited a self-trapping effect.48

Figure 12.

Sketch represents dependence between reaction time vs concentration of different morphological modifications and shape evolution of CsPbBr3 nanostructures during various reaction times (a, b) 10 min, (c) 30 min, (d) 40 min, (e) 90 min, and (f) 180 min. Scale bar is 100 nm. Reproduced from ref (48). Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society.

Climbing up, 2D HPs have one nanoscopic and two microscopic dimensions. Upon precise tailoring of thickness and dimensions of these materials, unique properties such as superb light absorption and emission, optical transparency, and high specific surface area can be achieved. The fabrication of 2D HP materials can be achieved using relatively simple techniques such as spin coating and drop-casting. Levchuk and co-workers prepared quantum size confined MAPbX3 (X = Br and I) 2D nanoplates by LARP. This approach made it possible to tune the thickness of the nanoplates by varying the ratios of oleylamine and oleic acid ligands. A quantum confinement effect was observed, making band gap tuning more efficient.102 It was possible to achieve remarkable PLQYs of 90% for MAPbBr3 and 50% for MAPbI3 nanoplates. There are several other examples of all-inorganic 2D HPs. For example, the successful fabrication of a few-unit-cell-thick 2D CsPbBr3 nanoplates via a room-temperature ligand-mediated method was reported by Sun et al. They demonstrated the preparation of CsPbBr3 QDs, nanorods, nanocubes, and nanoplates by the reprecipitation approach, varying organic acid and amine ligand concentrations. The as-prepared 2D CsPbBr3 nanoplates had a typical length of around 100 nm and thickness of about 5.2 ± 1.3 nm. It was concluded that the PL decay lifetimes depend on the size, shape, and composition of the HP nanostructures.103

Preparation of HP-based 3D periodic structures improves interaction with the light, benefiting from the intrinsic properties of HPs as well as from the features of periodic structures. It is possible to improve the properties of HPs and expand their use in photocatalytic, optical and electronic applications by creating hierarchical and periodic structures. Jeong and co-workers focused on micropatterning of HP films. They upgraded solvent-assisted gel printing methods with high-boiling temperature solvents. A variety of MAPbBr3 and MAPbI3 micropatterns (parallel lines, hexagons, and circular arrays) with controlled crystallinity and intrinsic photoelectric properties were fabricated. Moreover, micropatterns produced by the solvent-assisted gel printing method kept almost the same absorption and PL properties as usual HP thin films.104

Another HP 3D periodic structures are photonic crystals, which are interesting examples of structures with sophisticated morphologies and unique properties. By definition, a photonic crystal is a hierarchically porous ordered structure with areas of high and low refractive indices. Such structures hold great potential in electronic, optical and photocatalytic utilizations due to the slow-light effect which enhances the light absorption of the material.105,106 The fabrication of HP-based photonic crystals was first reported by the Tüysüz group. MAPbX3 (X = Cl, Br) based photonic crystal thin films with controllable porosity and thicknesses between 2 and 6 μm were successfully prepared. The group used the colloidal template method which entails assembling polystyrene opal templates, infiltrating methylammonium liquid precursor, and removing polystyrene spheres using toluene. Varying the size of the PS spheres, the position of the photonic stop band can be easily tuned through the visible spectrum as well as band gap energies by adjusting halide ratio.107

4.4. Charge Separation

Upon interaction of HPs with light, photoexcited charge carriers are generated. For efficient exciton formation, the energy of the incoming irradiation should be greater than or equal to the band gap energy of the HP. Photoexcited e– and h+ can further migrate to the surface and drive electrochemical and catalytic reactions producing useful chemicals. A large portion of the photoexcited carriers undergoes recombination either on the surface of the catalyst or in the bulk through radiative (photo) and/or nonradiative (thermal) processes. HPs are considered a superb photocatalyst due to their good optical and transport properties such as large carrier diffusion lengths, long lifetimes, low trap densities, high charge carrier mobility, and low recombination rate.108,109 The path length that photoexcited e– and h+ travel from generation to recombination is considered the carrier diffusion length. A long electron–hole diffusion length usually requires several conditions such as a long carrier lifetime, high carrier mobility, and low recombination rates, which all depend on material properties such as the exciton binding energy.

Zhang and co-workers observed extra-long electron–hole diffusion lengths in MAPbI3-xClx of 380 μm under 1 sun illumination in crystals with varying amounts of chlorine. The group further deduced that there were two prevailing factors for electron–hole recombination and transfer: first, an increase in the density of trap-states, and, second, a reduction of the VB level by incorporation of chlorine ions.110 Improvement of the carrier diffusion length was also demonstrated by Zhumekenov et al. They reported a remarkable enhancement in electron–hole transport in FAPbX3 single crystals. FAPbBr3 displayed a 5-fold longer carrier lifetime and 10-fold lower dark carrier concentration than those of MAPbBr3 single crystals. The carrier diffusion lengths were found to be longer than 6.6 μm for FAPbI3 and 19.0 μm for FAPbBr3 single crystals.111

Yang et al. studied the surface recombination in MAPbBr3 single crystals using broadband transient reflectance spectroscopy. They found that electron–hole dynamics depend on the surface recombination and carrier diffusion from the surface into the bulk. Moreover, the surface recombination velocity was estimated to be 3.4 ± 0.1 × 10–3 cm s–1. The obtained value was 2–3 orders of magnitude lower than that of many unpassivated semiconductors used in solar cell applications.112 Savenije and co-workers investigated the temperature dependence of the carrier generation, mobility, and recombination in MAPbI3 by microwave photoconductance and PL techniques. The temperature-dependent yield of highly mobile electron–hole pairs was 6.2 cm2 V–1 s–1 at about 32 meV and was obtained maintaining the temperature at 300 K in the tetragonal crystal phase. Moreover, reducing the temperature to 160 K led to a reduction in phonon scattering by Σμ = 16 cm2 V–1 s–1 (Σμ is the sum of the electron and hole mobility) and an increase in charge carrier mobilities following a T–1.6 dependence. It is interesting to note that while Σμ was increasing, γ was decreasing by a factor of 6. This observation led to the conclusion that the electron–hole recombination in MAPbI3 was temperature-activated (Figure 13).113

Figure 13.

Normalized intensity photoconductance traces vs. time. Charge carrier dynamics obtained using various excitation intensities at (a) 165 K, (b) 240 K, and (c) 300 K, and (d) PL of MAPbI3 on Al2O3 vs temperature (circles) detected by integrating over the emission band on optical excitation at 514 nm. The dashed line represents an exponential fit to the data points yielding binding energy of 32 ± 5 meV. The solid line shows the yield of charges on assuming that thermal ionization is the only nonradiative decay channel. Reproduced from ref (113). Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society.

Kanemitsu et al. investigated intensity-dependent photocarrier recombination and relaxation processes in MAPbI3 thin films using time-resolved PL and transient absorption methods. The PL intensity right after excitation displayed double-fold dependence on the excitation intensity implying that radiative recombination of photoexcited carriers is the primary process for PL and the exciton model was not as accurate at room temperature.114