Abstract

Background:

Hormonal variation throughout the menstrual cycle influences physiological and psychological symptoms, although not for all women. Individual differences in health anxiety (HA) might help to explain the differences in physiological and psychological symptoms and perceived stress observed across women.

Design:

We examined the moderating role of HA in the relation between menstrual phase and premenstrual symptom severity and perceived stress.

Methods:

A total of 38 women completed visits in both late luteal and follicular phases, with visit order randomized. Menstrual phase was verified using day-count, a luteinizing hormone test, and progesterone assay.

Results:

Linear mixed models revealed that women experienced more premenstrual symptoms during the late luteal phase vs. the follicular phase; however, HA did not moderate this effect. There was a significant HA × menstrual cycle phase interaction for perceived stress. During the late luteal phase, women with higher HA reported greater perceived stress compared to women with lower HA. In the follicular phase, women with higher and lower HA reported similar levels of perceived stress.

Conclusion:

Higher levels of HA may play a role in the experience of perceived stress in specific phases of the menstrual cycle.

Keywords: health anxiety, perceived stress, menstrual cycle, premenstrual symptoms, psychosomatic gynecology

Introduction

Mental and physical health symptoms have been associated with phases of the menstrual cycle where hormones are in flux (Freeman, 2003; Halbreich et al., 2003; Yonkers et al., 2003). The late luteal phase occurs the week preceding menses, and the final few days of this phase are characterized by sharply decreasing levels of progesterone and estradiol due to the atrophy of the corpus luteum (Shikone et al., 1996; Yen, 1999). The late luteal phase has been associated with increases in perceived stress (Montero-Lopez et al., 2018) and physical and psychological distress, including increased irritability, depression and anxiety symptoms, bloating, appetite change, food cravings, sleep disturbances, breast tenderness, swelling, and muscle pain (Perez-Lopez et al., 2009; Yonkers et al., 2008; Ziomkiewicz et al., 2012). Conversely, the mid to late follicular phase (hereafter referred to as the follicular phase), which begins after the end of menses and ends at the onset of ovulation, is characterized by stable levels of progesterone and rising levels of estradiol and luteinizing hormone (LH; Yen, 1999). Relative to the late luteal phase, the follicular phase is typically associated with fewer physical and psychological symptoms (Gonda et al., 2008).

Women vary significantly in the extent to which they experience symptoms during the late luteal phase and in response to normal hormonal shifts across the menstrual cycle (Gehlert et al., 2009). Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a severe form of premenstrual symptoms characterized by a combination of affective, cognitive, and physical symptoms and impairment in functioning (Halbreich et al., 2003). Although about 50–80% of women report heightened levels of physical and psychological discomfort during their late luteal phase, only 3–9% report experiencing severe enough symptoms and impairment to meet DSM criteria for PMDD (Angst et al., 2001; Halbreich et al., 2003; Romans et al., 2012). The extent to which women experience premenstrual symptoms may be influenced by several underlying psychological factors. One potential factor, that has yet to be explored, may be the degree to which a woman experiences anxiety regarding her health (i.e., health anxiety) as this may affect her sensitivity to and perception of changes in premenstrual symptoms.

Health anxiety is characterized by excessive fears or beliefs that one has a serious illness based on the misinterpretation of bodily changes or symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Barsky & Ahern 2004), resulting in a heightened focus on somatic symptoms (Asmundson et al., 2010; Haenen et al., 2000; Starcevic, 2005). Health anxiety is unique from general anxiety and other cognitive vulnerability factors for anxiety such as anxiety sensitivity. Specifically, anxiety sensitivity is the fear of physiological symptoms of anxiety (e.g., increased heart rate) due to the belief that certain bodily sensations indicate harm (McNally, 2002), while health anxiety directly relates to the irrational worry that somatic symptoms mean that one has a severe illness.

Health anxiety is also associated with high levels of psychological stress, including invasive and distressing thoughts (Olatunji et al., 2009; Sunderland et al., 2013). Therefore, it is possible that women higher in health anxiety may also be more likely to perceive their life as more stressful during the late luteal phase when they may experience an increase in physical symptoms. Perceived stress is the feelings or thoughts an individual has about how much stress they are under during a given period. It includes how over-whelming life events are and how they impact an individual’s well-being (Phillips, 2013). Perceived stress has been identified as a predictor for worsening premenstrual symptoms in prospective studies (Gollenberg et al., 2010; Lee & Im, 2016). Additionally, previous work has demonstrated an increase in the stress response to psychological stressors during the premenstrual phase (Kumari & Corr, 1998). Given the association between health anxiety and increased sensitivity to bodily changes and perceived stress (Asmundson et al., 2010; Haenen et al., 2000; Starcevic, 2005), it is possible that health anxiety differentially influences perceived stress and physiological and psychological experiences throughout the menstrual cycle. Specifically, women who are hypervigilant to physiological symptoms related to normal hormonal fluctuations might be more aware of them and thus, experience them at greater severity.

The present study sought to examine the moderating role of health anxiety on: (1) premenstrual symptoms and (2) perceived stress across two menstrual cycle phases (i.e., the late luteal and follicular phases). We hypothesized that women with relatively higher health anxiety would experience more severe premenstrual symptoms and higher levels of perceived stress in the late luteal phase as compared to themselves in the follicular phase, and as compared to women with relatively lower health anxiety in either menstrual cycle phase.

Materials and Method

Subjects

The current study was a part of a larger investigation, which assessed panic response across the menstrual cycle (Nillni et al., 2012). Normally menstruating women, with an average cycle length of 25–35 days that did not regularly vary in length from month to month by > 7 days, were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included: (1) use of hormonal birth control methods (i.e. birth control pill, patch, injection, or vaginal ring); (2) postmenopausal status or experiencing perimenopausal symptoms (i.e., hot flashes); (3) currently pregnant or trying to become pregnant; (4) current DSM-IV diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, alcohol or substance dependence, or psychosis; (5) current or past DSM-IV diagnosis of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia; (6) active and serious suicidal intent; (7) medical conditions that were contradictions to the biological challenge in the parent study (i.e. cardiovascular or seizure disorder, asthma); and (8) current use of anxiety medication (i.e. beta blockers, benzodiazepines).

A total of 38 women, who attended study sessions in both the follicular (Days 6 to 12) and late luteal (within 5 days prior to menses) menstrual cycle phases and whose cycle phases were confirmed, were included in the current analyses. Participants varied in age from 18 to 47 years (M = 26.24, SD = 9.42). A total of 2 (5.3%) identified as Hispanic, 33 (86.8%) as Caucasian, 2 (5.3%) as American Indian, 2 (5.3%) as Asian, and 1 (2.6%) as African American. A total of 27 (71.7%) reported a single marital status. Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. Informed consent was performed and obtained from all participants before enrolling in the study.

Table 1.

Population Characteristics of Total Sample and by Group (N = 38)

| Characteristic | Total Sample (N = 38) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age M (SD) | 26.2 | 9.4 |

| Race n (%) | ||

| American Indian | 2 | 5.3 |

| Asian | 2 | 5.3 |

| African American | 1 | 2.6 |

| White | 33 | 86.8 |

| Ethnicity n (%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 36 | 94.7 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 | 5.3 |

| Education n (%) | ||

| High School Degree | 1 | 2.6 |

| Some College | 21 | 55.3 |

| Associate’s Degree | 1 | 2.6 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 11 | 28.9 |

| Graduate Degree | 3 | 7.9 |

| Other | 1 | 2.6 |

| Marital Status n (%) | ||

| Single | 27 | 71.1 |

| Married | 9 | 23.7 |

| Living Together | 1 | 2.6 |

| Divorced | 1 | 2.6 |

| Current Axis I Diagnosis n (%) | 4 | 10.5 |

Note. Current Axis I diagnosis assessed via Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV-NP (First et al., 2002).

Measures

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-non-patient version (SCID-IV-NP; First et al., 1994) is a structured clinical interview that was used to assess for current and lifetime Axis I diagnoses and acute suicidal ideation. A doctoral student with extensive training in DSM-IV criteria administered the interview at the baseline study visit. The interviews were recorded, and 10% of the eligible interviews were coded for diagnostic reliability by a clinical psychology doctoral student. There were no disagreements between raters.

The Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP) is a 14-item daily self-report questionnaire (Endicott et al., 2006) that measures severity of 11 psychological and physical symptoms (i.e., felt angry, irritable) and 3 impairment symptoms, across the menstrual cycle. It is rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all to 6 = Extreme). The DRSP is a reliable and valid measure of premenstrual symptoms (Endicott et al., 2006). Participants completed this questionnaire daily for the duration of the time they were enrolled in the study (≥ one month) to assess menstrual symptom severity. All scores were summed and averaged across both phases to create separate follicular and late luteal symptom severity scores.

The Short Health Anxiety Inventory (HAI-Short Version) is an 18-item self-report questionnaire that measures health anxiety independent of current health status (Salkovskis et al., 2002). The questionnaire assesses worry about health (e.g., I spend most of my time worrying about my health), awareness of bodily sensations and changes (e.g., If I have a bodily sensation or change I must know what it means), and feared consequences of having a serious illness (e.g., A serious illness would ruin every aspect of my life) on a 0–3 scale. The HAI-Short Version was completed during the screening interview and the total score was summed with higher scores indicating greater health anxiety. Scores on the HAI can range from 0–54, with clinical samples typically reporting a mean level of 23 and non-clinical samples reporting a mean level of 12 (Alberts et al., 2013). Reliability of the HAI scale in the current sample was good (α = .86).

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) is a 14-item self-report questionnaire that measures perception of nonspecific stress (e.g., I have felt nervous and stressed very often) and the experienced levels of stress. Participants are asked to rate on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never to 4 = very often) how often they have felt each symptom. The PSS has been shown to be a reliable and valid assessment of perceived stress (Cohen et al., 1983). Participants completed the PSS in both the follicular and late luteal menstrual phases. Scores were summed with higher scores suggesting greater levels of perceived stress. Scores on the PSS can range from 0–56, with clinical samples typically reporting a mean level of 38 and non-clinical samples reporting a mean level of 24 (Lavoie & Douglas, 2012). Reliability of the PSS scale in the current sample was good in both the late follicular (α = .86) and late luteal cycle phases (α = .89).

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Negative Affect Scale (N-PANAS) is a 10-item self-report questionnaire that measures negative affectivity (Watson et al., 1988). The N-PANAS has demonstrated sound psychometric properties (Crawford & Henry, 2004; Watson et al., 1988). The PANAS is composed of 10 emotion items that reflect positive (e.g. attentive, interested, alert) and 10 items that reflect negative affect (e.g. distressed, hostile, irritable), which are rated on a five-point Likert scale (1= slightly or not at all to 5 = very much). The N-PANAS was used to control for negative affectivity in the current sample. Reliability of the N-PANAS in the current sample was excellent (α = .91).

Procedure

Participants were recruited via flyers, craigslist, recruitment letters to OBGYN offices, and announcements posted in the greater Burlington, Vermont area. Advertisements called for menstruating women over the age of 18 to participate in a study examining the experience of anxiety among women. Interested participants first completed a screening visit consisting of a diagnostic interview (SCID-IV-NP) and medical questionnaire to assess for eligibility. Eligible participants were asked to complete a battery of self-report questionnaires, including the HAI-Short Version. In addition, participants were instructed to complete the DRSP daily at home starting on the first day of menstruation for at least one full menstrual cycle, and to detect their LH surge using an at-home test. Participants were scheduled for two follow-up visits in the laboratory. The first follow-up visit was randomized to occur either during their late luteal or follicular phase, and the second occurred during the other phase, respectively. The late luteal phase (premenstrual) visit was scheduled 12–14 days following detection of the LH surge, and the follicular phase visit was scheduled between days 6–12 of their menstrual cycle. Determination of menstrual cycle phase was assessed using self-report and detection of the LH surge, and further verified by salivary assay of progesterone. Women whose visits were not verified to have occurred in the prescribed menstrual cycle days (i.e., between Days 6 and 12 for follicular and within 5 days prior to menses for the late luteal) were not included in analyses. More visits were unverified for the late luteal phase vs. the follicular phase, resulting in an uneven number of included women who completed each phase first [i.e., 11/38 (29%) completed the late luteal phase first and 27/38 (71%) completed the follicular phase first]. During these visits, participants completed a battery of assessments, including the PSS, and underwent a laboratory CO2 challenge (Nillni et al., 2012). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the University of Vermont Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

Given our interest in within-subject menstrual cycle phase differences, only participants who completed the assessment in both menstrual cycle phases were included. DRSP data were missing from one participant at both time points. All other data were complete. Data analyses were conducted in SPSS v. 25.

First descriptive statistics were conducted to examine levels of health anxiety, premenstrual symptoms, and perceived stress within our sample and across menstrual cycle phases. Next, a series of linear mixed models (LMM) were conducted to examine the effect of health anxiety (continuous, between-subjects factor), the main effect of menstrual cycle phase (categorical, within-subjects factor), and the interactive effects of health anxiety and menstrual cycle phase on: (1) severity of premenstrual symptoms (DRSP scores) and (2) perceived stress (PSS scores). Use of LMM was selected over traditional analysis of variance (ANOVA) models, as LMM allowed us to consider health anxiety as a continuous moderator of the association between menstrual cycle phase and DRSP/PSS scores. Models were initially run with the late luteal phase as the reference group (0 = follicular, 1 = late luteal). The phase variable was then recoded and models were rerun with the follicular phase as the reference group (0 = late luteal, 1 = follicular). Across models, the health anxiety effect indicated the association between health anxiety scores and the scores on the outcome variable at the reference menstrual cycle phase. The phase effect indicated the slope from the reference to the other menstrual cycle phase when health anxiety scores were held constant at 0, and the health anxiety x phase interaction indicated the change in slope as health anxiety increased. Finally, where significant interaction effects emerged, additional models were run including negative affect (i.e., measured with the N-PANAS) as a fixed effect covariate to examine whether controlling for negative affect impacted findings.

Results

Levels of health anxiety in this sample (mean = 10.39) were consistent with health anxiety scores in other non-clinical samples (i.e., 12.0; Alberts et al., 2013). Levels of perceived stress in this sample (late luteal PSS mean = 22.29 and follicular PSS mean = 22.45) were consistent with PSS scores in other non-clinical female samples (i.e., 23.18; Cohen et al., 1983). Finally, clinically significant PMS (i.e., defined as having at least 1 symptom on the DRSP rated as ≥ 5 in the late luteal phase and having a mean DRSP score greater in the late luteal phase as compared to the follicular phase) was 29.0%, which is consistent with other studies that have used this definition to identify clinically significant PMS in non-clinical sample (30%; Borenstein et al., 2007).

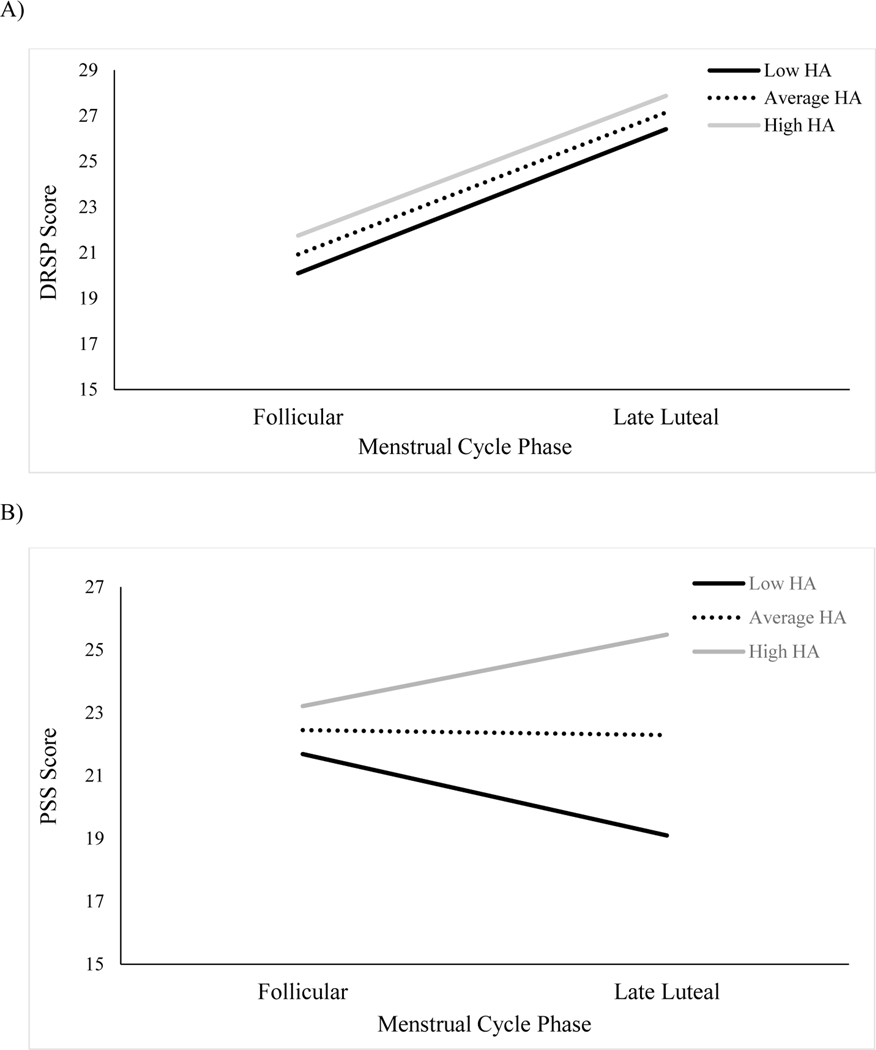

Our first hypothesis was that health anxiety would moderate the change in DRSP scores across the follicular and late luteal menstrual cycle phases. Results of the model using the late luteal phase as the reference group are presented in Table 2. During the late luteal phase, there was no significant association between health anxiety and premenstrual symptoms (R2 = .004). When the model was examined using the follicular phase as the reference group, results similarly revealed that health anxiety was not significantly associated with premenstrual symptoms during the follicular phase, B = .15, SE = .27, t (52.95) = .56, p = .58, 95% CI [−.39, .68], R2 = .02. Across models, a significant menstrual cycle phase effect emerged. In the absence of health anxiety (i.e., health anxiety held constant at 0), participants’ symptoms were significantly higher during the late luteal phase (M = 25.77, SE = 3.15) as compared to the follicular phase (M = 19.38, SE = 3.15; Mdiff = 6.40, 95% CIdiff [.45, 12.34]; see Figure 1a). The interaction between health anxiety and menstrual cycle phase was not significant, indicating that the difference in symptoms between the late luteal and follicular phases did not change as a function of participants’ health anxiety.

Table 2.

Linear Mixed Model Estimates of Fixed Effects

| DRSP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| B | SE | df | t | p | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 25.77 | 3.15 | 52.95 | 8.18 | < .001 | 19.45, 32.09 |

| HAI | .13 | .27 | 52.95 | .49 | .62 | −.40, .67 |

| Phase | −6.40 | 2.93 | 35 | −2.18 | .04 | −12.34, −.45 |

| HAI x Phase | .02 | .25 | 35 | .07 | .95 | −.49, .52 |

|

| ||||||

| PSS | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| B | SE | df | t | p | 95% CI | |

|

| ||||||

| Intercept | 16.29 | 2.61 | 54.56 | 6.25 | < .001 | 11.07, 21.51 |

| HAI | .58 | .22 | 54.56 | 2.6 | .01 | .13, 1.02 |

| Phase | 4.72 | 2.43 | 36 | 1.94 | .06 | −.20, 9.65 |

| HAI x Phase | −.44 | .21 | 36 | −2.12 | .04 | −.86, −.02 |

Note. DRSP = Daily Record of Severity of Problems; HAI = Health Anxiety Inventory; PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; phase = follicular (0) vs. late luteal (1).

Figure 1.

Interaction between Health Anxiety (HA) and Menstrual Cycle Phase for A) Premenstrual Symptoms and B) Perceived Stress

Note. DRSP = Daily Record of Severity of Problems; PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; HA assessed using the Health Anxiety Inventory; Low HA = 4.86; Average HA = 10.39; High HA = 15.93.

Our second hypothesis was that health anxiety would moderate the change in PSS scores across the follicular and late luteal menstrual cycle phases. Results of the model using the late luteal phase as the reference group are also presented in Table 2. During the late luteal phase, participants health anxiety was significantly positively associated with perceived stress (R2 = .16). Importantly, our second model revealed that health anxiety was not significantly associated with perceived stress during the follicular phase, B = .14, SE = .22, t (54.56) = .62, p = .54, 95% CI [−.31, .58] , R2 = .01. Across models, the effect of menstrual cycle phase was marginally significant. With health anxiety held constant at 0, participants’ perceived stress levels were marginally higher during the follicular (M = 21.02, SE = 2.61) as compared to the late luteal (M = 16.29, SE = 2.61; Mdiff = 4.72, 95% CIdiff [−.21, 9.65]) phase. As hypothesized, there was a significant interaction between health anxiety and menstrual cycle phase on PSS scores, indicating that the direction of the slope changed as participants’ health anxiety increased. As seen in Figure 1b, women with low (−1 SD from the mean) health anxiety endorsed somewhat greater perceived stress during the follicular phase than the late luteal phase (Mdiff = 2.59, 95% CIdiff [−.67, 5.85]). However, women with average levels of health anxiety endorsed similar levels of perceived stress across menstrual cycle phases (Mdiff = .16, 95% CIdiff [−2.14, 2.45]) and women with high levels of health anxiety endorsed high (+1 SD from the mean) health anxiety endorsed somewhat greater perceived stress during the late luteal phase than the follicular phase (Mdiff = 2.27, 95% CIdiff [−.99, 5.54]). Sensitivity analyses controlling for negative affect revealed that the interaction between health anxiety and menstrual cycle phase remained significant, B = −.44, SE = .21, t (36) = −2.12, p = .04, 95% CI [−.86, .02].

Discussion

The present investigation examined health anxiety as a moderator of menstrual cycle-related changes in symptoms and perceived stress. Women who experience greater health anxiety may be at an increased risk for experiencing premenstrual symptoms, including physiological and psychological symptoms related to changes in hormones across the menstrual cycle. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that women who reported greater levels of health anxiety experienced higher levels of perceived stress during the late luteal phase, when progesterone and estradiol were declining, as compared to women with lower levels of health anxiety.

Study results suggest that the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle may be a phase in which women with high health anxiety are particularly vulnerable to experience greater perceived stress. Given that women with greater health anxiety are hypervigilant to changes in their body (Asmundson et al., 2010; Haenen et al., 2000; Starcevic, 2005), they may be more vulnerable to experience stress during the late luteal phase due to increased awareness of changes in bodily sensations that occur during this menstrual cycle phase. Therefore, the late luteal phase may provide a cyclical opportunity to maintain problematic levels of health anxiety.

We did not observe differences between women who were higher vs. lower in health anxiety on premenstrual symptoms in either the late luteal or follicular phase. Consistent with previous research, we found that, after controlling for health anxiety, women in this study reported more severe premenstrual symptoms during their late luteal phase as compared to their follicular phase (Perez-Lopez et al., 2009; Yonkers et al., 2008; Ziomkiewicz et al., 2012; Gonda et al., 2008). This suggests that while symptom severity changes between the late luteal and follicular phases, health anxiety does not appear to play a role in increasing premenstrual symptoms.

Given the interaction between health anxiety and perceived stress, it is possible that interventions to improve health anxiety, such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and exposure therapy, may subsequently diminish fluctuations in perceived stress across the menstrual cycle (McManus et al., 2012). Alternatively, pharmacological interventions such as hormonal oral contraceptives, which have been prescribed for women with more severe premenstrual symptoms (Yonkers et al., 2005), may potentially reduce the risk for women higher on health anxiety to experience increased perceived stress during the premenstrual phase. However, this potential benefit for some women should be viewed with caution, given contradictory evidence regarding the effects of oral contraceptives on fluctuation in mood across the menstrual cycle (Oinonen & Mazmanian, 2002; Joffe et al., 2003). Finally, simple psychoeducation about normal menstrual cycle-related changes in physiological and psychological symptoms and increased awareness may diminish the perception of increased stress during the late luteal phase for at-risk women.

There are several limitations in the current study that warrant further discussion. First, our study sample was a relatively clinically healthy group of women. For example, there was a low prevalence of current past month (10.5%) psychopathology in the sample and the mean health anxiety score of women was 10.39 (SD = 5.54). As a comparison, clinical samples typically score higher on health anxiety using this measure (M = 22.94; Alberts et al., 2013). Second, our study sample was primarily Caucasian, college-educated women, which may reduce the generalizability of our findings. Therefore, these data require replication with larger, more diverse, and clinical populations. As symptom scores were collected over one menstrual cycle, future studies would benefit from including data collected over multiple menstrual cycles. Finally, participants only completed LH testing when scheduling their late luteal cycle phase visit. Therefore, for women randomized to complete their visit in the late luteal phase first, they did not have LH testing done during the cycle in which they completed their follicular phase visit. In these circumstances, it is possible that this cycle was anovulatory.

In summary, the current investigation highlights health anxiety as a potentially relevant moderator of menstrual cycle-related fluctuations in perceived stress, such that women with higher levels of health anxiety report more perceived stress during the late luteal phase as compared to the follicular phase and as compared to women with lower levels of health anxiety. Normal cyclical changes across the menstrual cycle may cause fluctuations in physical sensations and experiences, which may be misinterpreted and, thus, increase perceived stress among women higher in health anxiety.

Funding

This research was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health grant 1R36MH0861708 awarded to Yael Nillni

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Alberts NM, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Jones SL, & Sharpe D. (2013). The Short Health Anxiety Inventory: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(1), 68–78. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Angst J, Sellaro R, Stolar M, Merikangas KR, & Endicott J. (2001). The epidemiology of perimenstrual psychological symptoms. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 104(2), 110–116. 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00412.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmundson GJG, Abramowitz JS, Richter AA, & Whedon M. (2010). Health Anxiety: Current Perspectives and Future Directions. Current Psychiatry Reports, 12(4), 306–312. 10.1007/s11920-010-0123-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsky AJ, & Ahern DK (2004). Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Hypochondriasis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA, 291(12), 1464–1470. 10.1001/jama.291.12.1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein JE, Dean BB, Leifke E, Korner P, & Yonkers KA Differences in Symptom Scores and Health Outcomes in Premenstrual Syndrome. Journal of Women’s Health, 16(8), 1139–1144. 10.1089/jwh.2006.0230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, & Mermelstein R. (1983). A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JR, & Henry J,D The positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(3), 245–265. 10.1348/0144665031752934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Nee J, & Harrison W. (2006). Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP): reliability and validity. Archives Women’s Mental Health, 9(1), 41–49. 10.1007/s00737-005-0103-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibon M, & Williams JBW (1994). Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders: Patient edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0). New York: Biometrics Research Department. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman EW (2003). Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: definitions and diagnosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 28(3), 25–37. 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00099-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlert S, Song IH, Chang CH, & Hartlage SA (2009). The prevalence of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in a randomly selected group of urban and rural women. Psychological Medicine, 39(1), 129–136. 10.1017/S003329170800322X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollenberg AL, Hediger ML, Mumford SL, Whitcomb BW, Hovey KM, Wactawski-Wende J, & Schisterman EF (2010). Perceived Stress and Severity of Perimenstrual Symptoms: The BioCycle Study. Journal of Women’s Health, 19(5), 959–967. 10.1089/jwh.2009.1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonda X, Telek T, Juhász G, Lazary J, Vargha A, & Bagdy G. (2008). Patterns of mood changes throughout the reproductive cycle in healthy women without premenstrual dysphoric disorders. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 32(8), 1782–1788. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenen MA, de Jong PJ, Schmidt AJM, Stevens S, & Visser L. (2000). Hypochondriacs’ estimation of negative outcomes: domain-specificity and responsiveness to reassuring and alarming information. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(8), 819–833. 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00128-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbreich U, Borenstein J, Pearlstein T, & Kahn LS (2003). The prevalence, impairment, impact, and burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMS/PMDD). Psychoneuroendocrinology, 28(3), 1–23. 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00098-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe H, Cohen LS, & Harlow BL (2003). Impact of oral contraceptive pill use on premenstrual mood: predictors of improvement and deterioration. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 189(6), 1523–30. 10.1016/S0002-9378(03)00927-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karademas EC, Christopoulou S, Dimostheni A, & Pavlu F. (2008). Health anxiety and cognitive interference: Evidence from the application of a modified Stroop task in two studies. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(5), 1138–1150. 10.1016/j.paid.2007.11.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, & Corr PJ (1998). Trait anxiety, stress and the menstrual cycle: effects on raven’s standard progressive matrices test. Personality and Individual Differences, 5(24), 615–623. 10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00233-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie AAJ, & Douglas SK (2012). The Perceived Stress Scale: Evaluating Configural, Metric, and Scalar Invariance across Mental Health Status and Gender. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 34(1), 48–57. 10.1007/s10862-011-9266-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, & Im EO (2016). Stress and Premenstrual Symptoms in Reproductive-Aged Women. Health Care for Women International, 37(6), 646–670. 10.1080/07399332.2015.1049352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus F, Surawy C, Muse K, Vazquez-Montes M, & Williams JMG (2012). A randomized clinical trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus unrestricted services for health anxiety (hypochondriasis). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(5), 817–828. 10.1037/a0028782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ (2002). Anxiety sensitivity and panic disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 52(10), 928–946. 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01475-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero-López E, Santos-Ruiz A, García-Ruíz C, Rodríguez-Blázquez M, Rogers HL, & Peralta-Ramírez MI (2018). The relationship between the menstrual cycle and cortisol secretion: Daily and stress-invoked cortisol patterns. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 131, 67–72. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2018.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nillni YI, Rohan KJ, & Zvolensky MJ (2012). The role of menstrual cycle phase and anxiety sensitivity in catastrophic misinterpretation of physical symptoms during a CO2 challenge. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 15(6), 413–422. 10.1007/s00737-012-0302-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oinonen KA, & Mazmanian D. (2002). To what extent do oral contraceptives influence mood and affect? Journal of Affective Disorders, 70(3), 229–240. 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00356-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Deacon BJ, & Abramowitz JS (2009). Is hypochondriasis an anxiety disorder? The British Journal of Psychiatry, 194(6), 481–482. 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.061085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Lopez FR, Chedraui P, Perez-Roncero G, Lopez-Baena MT, & Cuadros-Lopez JL (2009). Premenstrual Syndrome and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: Symptoms and Cluster Influences. The Open Psychiatry Journal, 3(1), 39–49. 10.2174/1874354400903010039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romans S, Clarkson R, Einstein G, Petrovic M, & Stewart D. (2012). Mood and the Menstrual Cycle: A Review of Prospective Data Studies. Gender Medicine, 9(5), 361–384. 10.1016/j.genm.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA, Warwick HMC, & Clark DM (2002). The Health Anxiety Inventory: development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychological Medicine, 32(5), 843–853. 10.1017/s0033291702005822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikone T, Yamoto M, Kokawa K, Yamashita K, Nishimori K, & Nakano R. (1996). Apoptosis of human corpora lutea during cyclic luteal regression and early pregnancy. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 81(6), 2376–2380. 10.1210/jcem.81.6.8964880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starcevic V. (2005). Fear of Death in Hypochondriasis: Bodily Threat and Its Treatment Implications. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 35(3), 227–237. 10.1007/s10879-005-4317-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sunderland M, Newby JM, & Andrews G. (2013). Health anxiety in Australia: prevalence, comorbidity, disability and service use. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(1), 56–61. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.103960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Tellegen A. (1988) Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen SSC (1999). The human menstrual cycle : Neuroendocrine regulation. In Yen SSC, Jaffe RB, & Barbieri RL (Eds.), Reproductive endocrinology: Physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical management (pp. 191–217). Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company. [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Brown C, Pearlstein TB, Foegh M, Sampson-Landers C, & Rapkin A. (2005). Efficacy of a New Low-Dose Oral Contraceptive With Drospirenone in Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 106(3), 492–501. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000175834.77215.2e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, O’Brien PS, & Eriksson E. (2008). Premenstrual syndrome. Lancet, 371(9619), 1200–1210. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60527-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Pearlstein T, & Rosenheck RA (2003). Premenstrual disorders: bridging research and clinical reality. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 6(4), 287–292. 10.1007/s00737-003-0026-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziomkiewicz A, Pawlowski B, Ellison PT, Lipson SF, Thune I, & Jasienska G. (2012). Higher luteal progesterone is associated with low levels of premenstrual aggressive behavior and fatigue. Biological Psychology, 91(3), 376–382. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]