Abstract

Little attention is paid to disease definition in dermatology and how such definitions come about, yet defining a disease is a fundamental step upon which all subsequent clinical management and prognostic judgements depend. Developing diagnostic criteria is also a critically important step for research purposes so that studies referring to groups of people can be compared in a meaningful way. This short review introduces the concepts of regressive and progressive nosology, and how definitions of a dermatological disease can evolve in a useful way as knowledge about that disease increases. It also highlights the dangers of panchrestons – names that try to explain all yet end up explaining very little. It also considers approaches to disease definition, such as whether a binary yes/no or continuous approach is more appropriate. Conceptual frameworks including essentialistic vs. nominalistic approaches using the biomedical or biopsychosocial perspectives are articulated. The review then illustrates hazards of underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis, and introduces the notion of ‘disease mongering’ – the selling of disease in order to promote the use of medicines. The review concludes with a reaffirmation of the importance of defining dermatological disease, and why any new diagnostic criteria must be shown to increase predictive ability before they are assimilated into clinical practice and research.

This short review introduces the concepts of regressive and progressive nosology, and how definitions of a dermatological disease can evolve in a useful way as knowledge about that disease increases. The review concludes with a reaffirmation of the importance of defining dermatological disease, and why any new diagnostic criteria must be shown to increase predictive ability before they are assimilated into clinical practice and research.

Click here for the corresponding questions to this CME article.

Why write about disease diagnosis?

In a seminal book on psychiatric diagnosis, Kendell 1 highlighted the crucial importance of disease definition as the foundation on which all else rests (Fig. 1). The topic may sound less crucial to a dermatologist working in a visual specialty, but the fundamental importance of disease diagnosis as the starting point for all therapeutic decisions cannot be underestimated. 2 Disease misclassification may appear trivial, e.g. treating someone with keratosis pilaris with 1% hydrocortisone because of a misdiagnosis of mild eczema, but they can also be serious, e.g. treating tinea faciei with topical corticosteroids. Deriving robust diagnostic criteria is also essential for science and health services research so that groups can be compared between centres or countries. 3 Misclassification as a result of imprecise diagnostic criteria may obscure important discoveries about risk factors or treatments, e.g. a clinical trial that includes a ‘rag bag’ of ‘steroid‐responsive dermatoses’ 4 may obscure treatment benefits if some conditions respond well whereas others do not. As well as justifying diagnostic criteria as the starting place for the patient journey, this article asks the reader to think about why and how diseases are named and categorized, and what such names mean for patients.

Figure 1.

The crucial importance of disease definition as the foundation on which all else rests as emphasized by Kendall. 1 [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Regressive and progressive nosology and panchrestons

Nosology deals with the classification of diseases, and can be regressive or progressive. An example of regressive nosology is the imprecise term ‘prostatism’ – a term that does little to increase predictive ability and confers spurious diagnostic authority – instead of using simpler and more honest terms that prompt further investigation, such as ‘lower urinary tract symptoms’. 5 In dermatology, there is no shame in using terms such as ‘scarring hair loss of unknown cause’ in order to prompt further investigation. Some dermatological terms may sound very precise but they may do little to increase predictive ability. Generally speaking, the longer the dermatological name, the less is known about that condition. Names such as lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei reflect the visual features of that condition. There is nothing wrong with such morphological descriptions as long as they prompt further study into risk factors and treatment. Here it worth introducing the concept of a panchreston (Fig. 2), a term that Hardin 6 used for an explanation or theory that can fit all cases, being used in such a variety of ways as to become meaningless. Are there any panchrestons in dermatology? Table 1 provides some provocative suggestions. I am not suggesting that the terms in Table 1 are meaningless; however, in clinical practice, such terms are the start of an explanation about the condition rather than the end.

Figure 2.

Hardin's 6 concept of panchreston: an explanation or theory that can fit all cases, being used in such a variety of ways as to become meaningless. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 1.

Some potential examples of reflexive nosology that are possibly bordering on panchreston status.

| What the patient's concern is: | What you as a dermatologist diagnoses their condition as: | What the patient then asks: | And your reply: |

|---|---|---|---|

| My daughter's big toenails have not been growing straight since birth | That's what we dermatologists call ‘congenital malalignment of the great toenails’ | What's that, then, doctor? | Well, it means that your daughter's big toenails have not grown straight since birth |

| I've got these red rings on my skin | Ah, you have got an annular erythema | Can you explain to me what that means? | There are red rings on your skin |

| All my nails have become rough | You have 20‐nail dystrophy | Ooh, that sounds nasty; what's that? | All 20 of your nails have become rough |

| I have got this brown streak in my nail | You have longitudinal melanonychia | That sounds serious; what does it mean? | You have a brown streak in your nail |

| I have noticed these prominent blood vessels present since birth on one side of my chest | Fascinating; that's what we call unilateral naevoid telangiectasia | What's that, then? | Prominent blood vessels present since birth on one side of the body |

| My child has this new rash around one of his armpits | I have just asked Professor Williams, and he says it is asymmetrical periflexural exanthem of childhood | I am sure he is very clever, but what does it all mean, though? | Your child has a rash around one of his armpits |

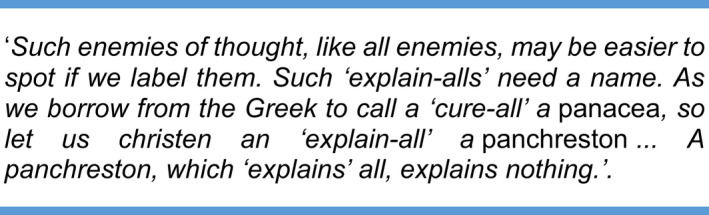

Progressive nosology refers to how disease classification moves forward as new discoveries are made 7 (Fig. 3). Over 100 years ago, pemphigus referred to several bullous disorders, including pemphigoid, which have since been separated due to the discovery of different risk factors, histopathology, immunohistopathology and cellular biology. 8

Figure 3.

The naming and classification of disease can progress as learning moves from good descriptions to disease causation. EAC, erythema annulare centrifugum; XLRI, X‐linked recessive ichthyosis. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Names matter

Terms such as ‘neurotic’ excoriations might best be avoided as they invite judgements on the affected people 9 (Table 2). Even morphological terms such as nodules or erythema have become imprecise due to sloppy and inappropriate usage. 10 , 11 The word ‘carcinoma’ used for low‐risk basal cell carcinoma might also be challenged as this term usually implies to a patient a very serious disease that can kill, whereas such occurrences are exceedingly rare.

Table 2.

Names matter: some dermatological names invite judgements a on an individual, which may not always be appropriate.

| Juvenile melanoma |

| Trichotillomania |

| Acne excoriée des jeunes filles |

| Neurotic excoriations |

| Dermatitis neglecta |

The terms in bold font invite judgements.

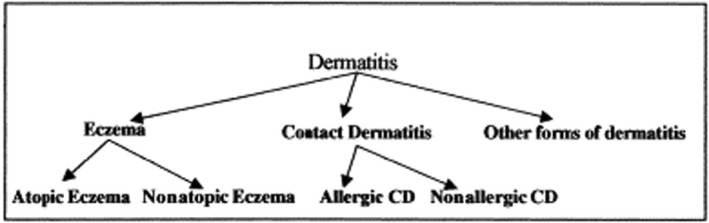

Some names such as ‘atopic dermatitis’ (AD) create an air of spurious precision. ‘Atopic’ means specific IgE antibodies to common environmental allergens but many people with the classic AD phenotype are not atopic, especially in the community and in developing countries. 12 Figure 4 shows a more logical classification of eczema suggested by the World Allergy Organization. 13 It could even be argued that dividing the eczema phenotype into atopic and nonatopic types has done little to increase predictive ability in terms of prognosis or treatment 14 compared with the predictive information that fillagrin gene mutations provide. 15 This is a warning against the premature splitting of diseases into subtypes based on possible epiphenomena.

Figure 4.

The World Allergy Organization Nomenclature Committee's proposal for classifying dermatitis. 13

Conceptual frameworks for defining disease

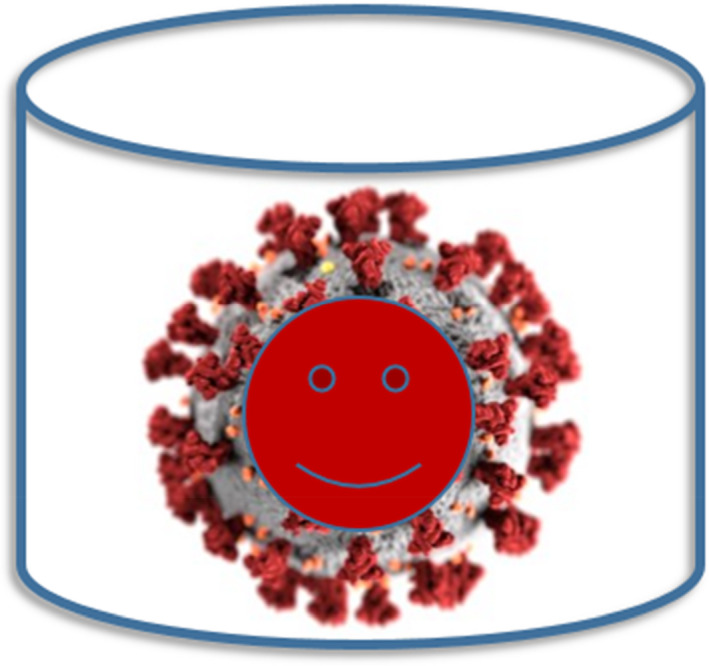

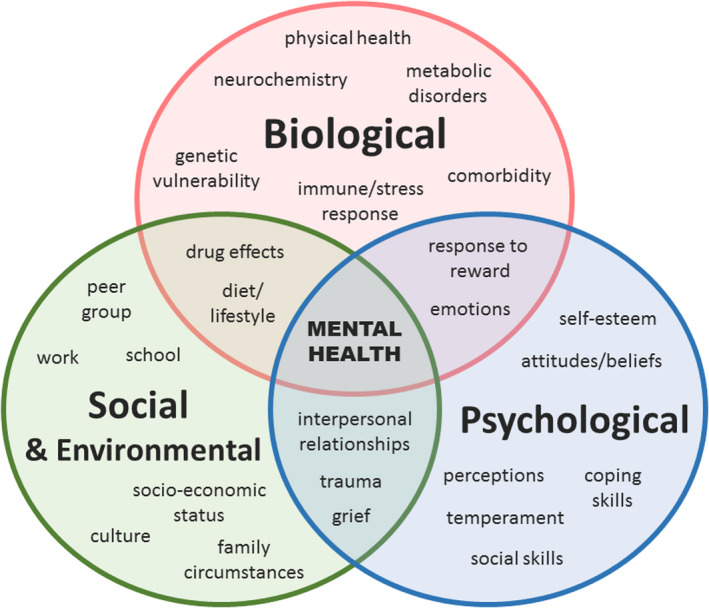

It is important to question whether skin diseases are a continuous or categorical phenomenon. In 1960, Oldham et al. 16 suggested that essential hypertension, a major cause of death, is a graded characteristic that shades insensibly into normality, and yet many physicians still have difficulties in viewing diseases as quantitative or multidimensional processes. Diseases have no real existence outside the individual patient. Even viruses such as SARS‐CoV‐2, which can be ‘captured’ like some demon (Fig. 5), produce a wide range of clinical manifestations from asymptomatic infection through to a serious cough or death. 17 Common skin diseases such as AD also do not conform to an essentialistic disease model (i.e. the disease is an entity in itself, which ‘attacks’ patients), 18 but a syndrome of related clinical features arising in response to endogenous and exogenous factors. 19 In 1977, Engel challenged the prevailing biomedical model of disease underpinned by molecular biology in which disease is defined as deviations from the norm, by pointing out that it leaves no room for incorporating the social, psychological and behavioural dimensions of illness, i.e. the biopsychosocial model of disease 20 (Fig. 6). Some people with moderate acne are not troubled by it, whereas others with minimal acne are profoundly upset. Social norms such as removal of unwanted hair are also important contextual factors for defining ‘dis‐ease’. Such a ‘nominalistic’ or person/society‐based approach is appropriate in clinic because all patients are different; however, some sort of binary disease definition is usually needed for scientific studies so that groups can be compared. 7 Such binary definitions such as ‘atopic dermatitis yes/no’ using diagnostic criteria are acceptable, provided their validity (sensitivity and specificity) are known and their limitations acknowledged. 21

Figure 5.

Even infectious diseases such as SARS‐CoV‐2 cannot be considered as essentialistic entities that can be captured like a demon in a bottle. Diseases have no existence without a host, and manifestations range from asymptomatic carriage to death. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 6.

Human diseases and health can be thought of as an intersection between biomedical factors (such as genetics or an immune response to an external insult or infection) and how the individual perceives and deals with the episode in relation to the societal factors in which that person lives. Taken from the Open University 27 (Creative Commons License). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Hazards of underdiagnosis, misdiagnosis and overdiagnosis

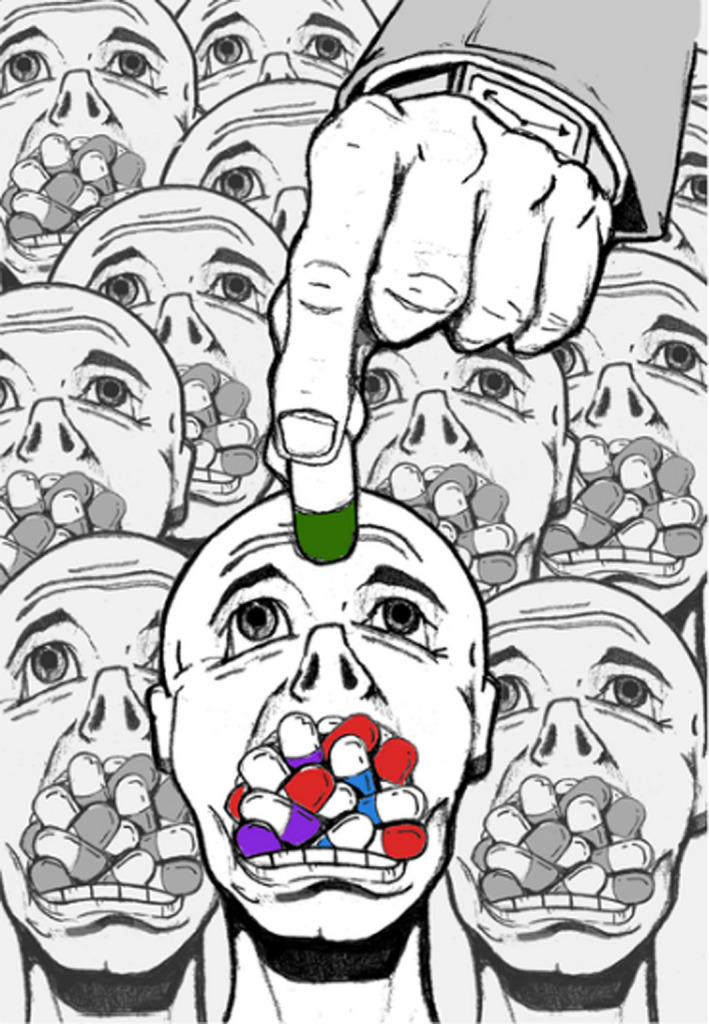

The adverse consequences of misdiagnosing skin diseases are usually well appreciated (Table 3). Less discussed is the concept of overdiagnosis and overmedicalization (Fig. 7), e.g. conducting multiple tests that throw up borderline results, triggering more tests. 22 Screening the ‘worried well’ with whole‐body scans or prophylactic removal of large numbers of harmless moles are other examples. Disease mongering is a particular branch of overmedicalization that Moynihan et al. defines as ‘the selling of sickness that widens the boundaries of illness and grows the markets for those who sell and deliver treatments’, citing conditions such as premenstrual dysphoric disorder to help sell a rebranded version of fluoxetine. 23 Does such disease mongering exist in the world of dermatology? Possible examples include changing the name of solar keratoses to carcinoma in situ – an accurate histological description but one that elevates disease status to one that is perhaps more likely to attract reimbursement. 24 Is the new status of erythrotelangiectatic rosacea related to the availability of brimonidine gel? To what extent is the quest for comorbidities for diseases such as AD, lichen planus and rosacea 25 , 26 driven partly by industry in order to justify a bigger market for new and expensive treatments? Possibly none of these are true, but awareness of disease mongering is important.

Table 3.

Some examples of misdiagnosis of skin conditions and the possible ensuing consequences.

| Skin condition | Misdiagnosed as | Consequences of misdiagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| Scabies | Atopic dermatitis | Perpetuation of itch, sleep loss and spread to other family members |

| Erythropoietic protoporphyria | Normal skin | Child labelled as ‘playing up’ when they scream on exposure to sunlight |

| Tinea capitis | Seborrhoeic dermatitis | Chronic carriage, spread to other family members, kerion, scarring |

| Acrodermatitis enteropathica | Irritant contact dermatitis | Failure to thrive in the absence of sufficient zinc |

| Fabry disease (angiokeratoma corporis diffusum) | Normal angiomas | Missing out on enzyme replacement therapy with agalsidase α or β |

| Purpura from meningococcal septicaemia | Reactive viral rash | Severe complications or death |

| A small, rapidly growing nodular melanoma on the leg of an elderly woman | Benign mole | Spread via the lymphatic and blood systems, leading to advanced metastatic disease and premature death |

Figure 7.

Overmedicalization can result in as much harm as undertreatment. Taken from Moynihan and Henry, 2006 (illustration: Anthony Flores). 28 [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Conclusion

This article challenges the reader to reflect on concepts of dermatological disease definition. The purpose of defining disease is to increase predictive ability such as response to treatment or disease progression. Whenever a new name for a disease appears or a split is proposed, it is important to consider whether such a change is useful to patients or for researchers conducting studies of groups. Disease diagnosis is fundamental to all clinical work and research, and is a journey based on progressive discovery.

Learning points.

-

•

Disease definition is a foundation on which all clinical practice and research rests.

-

•

Progressive nosology refers to the way in which dermatological conditions become reclassified as biomedical discoveries are made.

-

•

Names of conditions such as ‘acne excoriée des jeunes filles’ should be dropped as they invite judgements that may not be appropriate.

-

•

Some skin conditions such as atopic eczema or solar damage may not fit neatly into a yes/no diagnosis but instead are part of a continuum.

-

•

Skin diseases are not external entities that ‘attack’ patients but are the result of an interaction between biological, psychological and social factors in individuals.

-

•

Disease mongering is the selling of disease in order to grow markets.

Conflict of interest

HCW led the development of the UK refinement of the Hanifin and Rajka diagnostic criteria for atopic eczema.

Funding

None.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval and informed consent not applicable.

Data availability

Not applicable.

CPD questions

Learning objective

To gain up‐to‐date knowledge on the importance and conceptual frameworks of dermatological disease definitions.

Question 1

Why is disease definition important in research?

(a) It means that the standard deviation of disease can be calculated.

(b) It allows a wide range of patients to be included in a study.

(c) It allows studies on groups of people to be compared in a meaningful way.

(d) It measures the prognosis of disease.

(e) It allows a blinded assessment of outcome measures in a trial.

Question 2

Which of the following statements about progressive nosology is correct?

(a) The term prostatism is a good example of progressive nosology.

(b) Progressive nosology refers to the way in which the classification of disease can change as new understanding of mechanisms, risk factors and causes emerge.

(c) Progressive nosology means that the cause of the disease is known.

(d) Progressive nosology is something that Professor Williams has just made up.

(e) Progressive nosology refers to naming diseases as ‘unknown’ rather than labelling the disease.

Question 3

Which of the following statements about panchreston is correct?

(a) Panchreston refers to a name that tries to explain all yet ends up explaining very little.

(b) Panchreston is a town in Jamaica.

(c) Panchreston is a crusty desquamative skin eruption affecting most of the body.

(d) Panchreston is the same as a panacea.

(e) Panchreston is a synonym for the biopsychosocial model of human disease.

Question 4

Which of the following statements about essentialistic disease definitions is correct?

(a) Essentialistic disease definitions refer to the way in which diseases interact with psychological and social aspects of a patient's life.

(b) Essentialistic disease definitions are just the essential criteria needed to make a diagnosis.

(c) Essentialistic disease definitions are absolutely essential in clinical practice.

(d) Essentialistic disease definitions refer to the concept of disease as an entity in itself, which ‘attacks’ patients.

(e) Essentialistic disease definitions are also known as nominalistic disease definitions.

Question 5

Which of the following statements about disease mongering is correct?

(a) Disease mongering is direct advertising of a drug.

(b) Disease mongering is a type of disease that affects dogs.

(c) Disease mongering is the selling of disease in order to promote career opportunities.

(d) Disease mongering is the selling of disease in order to promote the use of medicines.

(e) Disease mongering is the selling of drugs in general.

Instructions for answering questions

This learning activity is freely available online at http://www.wileyhealthlearning.com/ced

Users are encouraged to

Read the article in print or online, paying particular attention to the learning points and any author conflict of interest disclosures.

Reflect on the article.

Register or login online at http://www.wileyhealthlearning.com/ced and answer the CPD questions.

Complete the required evaluation component of the activity.

Once the test is passed, you will receive a certificate and the learning activity can be added to your RCP CPD diary as a self‐certified entry.

This activity will be available for CPD credit for 2 years following its publication date. At that time, it will be reviewed and potentially updated and extended for an additional period.

Acknowledgement

I thank Dr Esther Burden‐Teh for helpful comments on this review.

References

- 1. Kendall RE. The Role of Diagnosis in Psychiatry. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burton JL. The logic of dermatological diagnosis. Dowling oration 1980. Clin Exp Dermatol 1981; 6: 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Williams HC, Burney PGJ, Hay RJ et al. The UK Working Party's Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis I: derivation of a minimum set of discriminators for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 1994; 131: 383–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fattah AA, El‐Shiemy S, Faris R, Tadros SS. A comparative clinical evaluation of a new topical steroid 'halcinonide' and hydrocortisone in steroid‐responsive dermatoses. J Int Med Res 1976; 4: 228–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abrams P. New words for old: lower urinary tract symptoms for "prostatism". Br Med J 1994; 308: 929–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hardin G. Meaninglessness of the word protoplasm. Scientific Monthly 1956; 82: 112–20. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Williams HC. What is atopic dermatitis and how should it be defined in epidemiological studies?In: Atopic Dermatitis (Williams HC, ed). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000; 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pye RJ. Bullous eruptions. In: Textbook of Dermatology, 4th edn (Rook AJ, Wilkinson DS, Ebling FJG, eds). Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1986; 1638. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jenkins Z, Zavier H, Phillipou A, Castle D. Should skin picking disorder be considered a diagnostic category? A systematic review of the evidence. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2019; 53: 866–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cox NH. Size matters? Yes, but the terminology doesn't. Br J Dermatol 2003; 148: 1278–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Finlay AY, Griffiths TW, Belmo S, Chowdhury MMU. Why we should abandon the misused descriptor 'erythema'. Br J Dermatol 2021; 185: 1240–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Flohr C, Johansson SGO, Wahlgren CF, Williams HC. How “atopic” is atopic dermatitis? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 114: 150–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johansson SG, Bieber T, Dahl R et al. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113: 832–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Williams H, Flohr C. How epidemiology has challenged 3 prevailing concepts about atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 118: 209–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Drislane C, Irvine AD. The role of filaggrin in atopic dermatitis and allergic disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2020; 124: 36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oldham PD, Pickering G, Fraser Roberts JA, Sowry GSC. The nature of essential hypertension. Lancet 1960; 1: 1085–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Ann Intern Med 2021; 174: 286–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scadding JG. Essentialism and nominalism in medicine: logic of diagnosis in disease terminology. Lancet 1996; 348: 594–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Williams HC. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 2314–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977; 196: 129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Williams HC. Defining atopic dermatitis – where do we go from here? Arch Dermatol 1999; 135: 583–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Worley L. Choosing wisely: the antidote to overmedicalisation. Lancet Respir Med 2017; 5: 177–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moynihan R, Doran E, Henry D. Disease mongering is now part of the global health debate. PLoS Med 2008; 5: e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marks R. Who benefits from calling a solar keratosis a squamous cell carcinoma? Br J Dermatol 2006; 155: 23–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Williams HC. A commentary on: Association of lichen planus with cardiovascular disease: a combined analysis of the UK Biobank and All of Us Study PracticeUpdate website. Available at: https://www.practiceupdate.com/content/association‐of‐lichen‐planus‐with‐cardiovascular‐disease/124766/48/4. Accessed 9 January 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26. Qureshi A, Friedman A. Comorbidities in dermatology: what's real and what's not. Dermatol Clin 2019; 37: 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Open University Open Learn . Exploring the relationship between anxiety and depression 2: the biopsychosocial model of mental health: revisited. Available at: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/science‐maths‐technology/exploring‐the‐relationship‐between‐anxiety‐and‐depression/content‐section‐2 (accessed 7 June 2022).

- 28. Moynihan R, Henry D. The fight against disease mongering: generating knowledge for action. PLoS Med 2006; 3: e191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.