Abstract

Aims

To investigate the scope of practice of nurse‐led services for people experiencing homelessness, and the influence on access to healthcare.

Design

A scoping review.

Data Sources

On 20 November 2020, the following databases were searched: CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PubMed and Scopus.

Review Methods

Included studies focused on people experiencing homelessness aged 18 years and over, nurse‐led services in any setting and described the nursing scope of practice. Studies were peer‐reviewed primary research, published in English from the year 2000. Three authors performed quality appraisals using the mixed methods assessment tool. Results were synthesized and discussed narratively and reported according to the PRISMA‐ScR 2020 Statement.

Results

Nineteen studies were included from the United States (n = 9), Australia (n = 4), United Kingdom (n = 4) and Canada (n = 2). The total participant sample size was n = 6303. Studies focused on registered nurses (n = 10), nurse practitioners (n = 5) or both (n = 4), in outpatient or community settings. The nursing scope of practice was broad and covered a range of skills, knowledge and attributes. Key skills identified include assessment and procedural skills, client support and health education. Key attributes were a trauma‐informed approach and building trust through communication. Important knowledge included understanding the impact of homelessness, knowledge of available services and the capacity to undertake holistic assessments. Findings suggest that nurse‐led care facilitated access to healthcare through building trust and supporting clients to access services.

Conclusion

Optimized nursing scope of practice can facilitate access to healthcare for people experiencing homelessness. Key factors in enabling this include autonomy in nursing practice, organizational support and education.

Impact

The broad range of skills, knowledge and attributes reported provide a foundation from which to design an educational framework to optimize the nursing scope of practice, thereby increasing access to healthcare for people experiencing homelessness.

Keywords: access to healthcare, health services accessibility, homeless persons, homelessness, nurse‐led, nurses, nursing service, practice patterns, nurses', scope of practice, scoping review

1. INTRODUCTION

Homelessness is a significant public health issue globally (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2020). People experiencing homelessness have poorer health outcomes, and experience higher rates of morbidity and mortality than the general population (Davies & Wood, 2018; Nusselder et al., 2013; Seastres et al., 2020). Ensuring equity in healthcare access can be challenging. As the largest healthcare discipline, nurses are often the first, and sometimes the only, point of contact people experiencing homelessness have with health services (Grech et al., 2021). As such, nurses are well placed to improve access to care for this marginalized population. This scoping review investigates the scope of practice of nurse‐led services for people experiencing homelessness and the influence on access to healthcare.

Scope of practice can be understood as the skills, knowledge and attributes a nurse is educated in, competent to undertake and which are permitted by law in the course of their normal duties (Nursing & Midwifery Board of Australia, 2016). Scope of practice is influenced by the context in which a nurse is practising, and reflects a nurse's level of education and competence. This is the definition which guides nursing practice in Australia, as set out by the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia's standards of practice for registered nurses, nurse practitioners and enrolled nurses (Nursing & Midwifery Board of Australia). Similarly, in the United Kingdom and the United States, the scope of practice is defined as the sum of a clinician's knowledge, skills and experience and the activities they are qualified to perform and carry out in their practice (American Nurses Association; Health & Care Professions Council, Nursing and Midwifery Council).

The term ‘nurse‐led service’ has been defined as a clinical practice where nurses manage their own patient caseload, practise with a high degree of autonomy, make independent care decisions, and have the authority to admit, discharge and make referrals to other healthcare professionals (Hatchett, 2008). In the context of people experiencing homelessness, this may include nurse‐led care in standalone primary health clinics (Dahrouge et al., 2014), clinics located in homeless shelters (Warren et al., 2021), street outreach services (Ungpakorn, 2017) or specialized clinics, such as in substance use or mental health (Baker et al., 2018).

Access to care is essentially the ability or ease with which a client can access the services they need, when they need. For the purpose of this review, the definition used will be that set out by Levesque et al. (2013), which incorporates the following dimensions: approachability, acceptability, availability and accommodation, affordability and appropriateness.

2. BACKGROUND

Homelessness is a growing problem internationally. In 2020, 1.6 billion people worldwide were without access to adequate housing, with global rates of homelessness increasing over the preceding decade (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2020). In the United States in 2020, roughly 580,000 people experienced homeless, with a rise noted since 2016 (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2021). In England, homelessness has increased year on year, peaking at 219,000 by the end of 2019, just before the start of the COVID‐19 pandemic (Crisis UK). In Australia, the 2016 Census estimated 116,427 people were experiencing homelessness, with approximately 7% sleeping rough (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018). This equates to a homelessness rate of 49.8 per 10,000 population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018), with a rise of 10% in the decade to 2016 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2020). People of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin are notably overrepresented, making up 20% of people identified as experiencing homelessness, whilst constituting only 3% of the general Australian population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018).

Homelessness is a complex concept (Mabhala et al., 2017). Currently, there is no universal consensus on how homelessness should be characterized, and various definitions exist worldwide. In the Australian context, homelessness is defined according to Chamberlain and MacKenzie (2008) into three main categories: Primary—people who are unable to access suitable accommodation, including those sleeping rough and people sheltering in improvised dwellings, such as sheds or abandoned buildings. Secondary—people in temporary accommodation who move regularly. This includes emergency or transitional accommodation, couch surfing and boarding house accommodation for 12 weeks or less. Tertiary—concerns people with a boarding house tenancy of 13 weeks or more. A fourth group is described by Flatau et al. (2018) as those housed in institutional settings, such as hospitals, substance rehabilitation centres or prisons.

The circumstances that lead to homelessness are often complicated, with both structural and individual causes. Structural factors include poverty, incarceration (Fazel et al., 2014) and insufficient access to secure employment, affordable housing and income support (Davies & Wood, 2018). Individually, causes include chronic physical and mental health problems, substance use, domestic and family violence, childhood trauma (Fazel et al., 2014) and relationship breakdown (Mabhala et al., 2017).

Of particular concern is the effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic on incidences of homelessness, particularly that stemming from domestic and family violence. During the pandemic, rates of violence have increased (Boxall et al., 2020), as have calls for domestic and family violence services (Carrington et al., 2020). Domestic and family violence is a known risk factor for homelessness in women (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018; Murray, 2011; Pavao et al., 2007), as finding alternative accommodation can be extremely difficult, leaving many women little other option.

People experiencing homelessness are known to have worse health outcomes than the general population, with a life expectancy between 11 (Nusselder et al., 2013; Seastres et al., 2020) and 30 years lower (Davies & Wood, 2018). Homelessness is associated with higher rates of mental illness, substance use disorders, acute and chronic physical illness, traumatic injury and disability (Seastres et al., 2020). Poor health, particularly poor mental health or substance use, can be a significant contributor to entering and persisting in homelessness (Fazel et al., 2014). Whilst experiencing homelessness, health problems of all types can emerge or be exacerbated by risk factors associated with homelessness, such as poor nutrition, exposure to infectious disease (Fazel et al., 2014), violence, accidental injury (Seastres et al., 2020) and increased rates of smoking and substance use (Schanzer et al., 2007).

Despite often having greater health needs than the general population, people experiencing homelessness tend to have reduced access to healthcare. This is influenced by practicalities including itinerancy, lack of access to transport and competing priorities, such as finding a meal (Davies & Wood, 2018). Relationship barriers, predominantly perceived stigma and judgement from health professionals, can make it challenging to attend a hospital or a clinic (Davies & Wood, 2018; Marmot, 2015). Furthermore, people experiencing homelessness are less likely to seek primary health care, resorting instead to episodic care in emergency departments, often at a later stage of ill health (Gaye Moore et al., 2007). Despite their complex health needs, in emergency departments they are more likely to be assessed as a lower clinical priority (Gaye Moore et al., 2007), wait longer to receive care (Ayala et al., 2021), leave before being seen by a clinician and re‐present at a later time (Formosa et al., 2021; Moore et al., 2011). Such ad hoc and fragmented care can result in costly hospital admissions and the development of chronic illness (Baggett et al., 2010; Davies & Wood, 2018; Flatau et al., 2018).

In addition to the significant impact on health, homelessness often carries the cost of increased use of government services, which in Australia amounts to an extra $13,100 per person per year (Parsell et al., 2015). One way to address this disparity is to increase access to mainstream primary and preventative care. As one of the most trusted and prolific healthcare disciplines, nurses are well placed to facilitate access to appropriate and beneficial care for people experiencing homelessness. The purpose of this review is to identify the scope of practice, the specific skills, knowledge and attributes, used in the provision of nurse‐led services to people experiencing homelessness and the influence on access to healthcare.

3. THE REVIEW

3.1. Aims

This review investigates the following:

What is the scope of practice of nurses (registered nurses and nurse practitioners) providing nurse‐led services to people experiencing homelessness?

How does the scope of practice of nurse‐led services influence access to healthcare for people experiencing homelessness?

3.2. Design

A scoping review was conducted, reported here in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta‐analyses‐scoping review extension (PRISMA‐ScR) guidelines (McGowan et al., 2020) (File S1). A study protocol was developed and registered initially as a systematic review on PROSPERO (CRD42021224447), and later amended to a scoping review on account of the breadth of the research questions.

A search strategy and protocol were developed by the authorship team, comprising nursing academics, one dental academic, clinicians, nursing managers and executive directors and a health service manager. Two of the authors had significant experience in providing healthcare to people experiencing homelessness, and two were experienced researchers in homeless health.

3.3. Search methods

The PICO framework was used to develop the eligibility criteria, as shown in Table 1. The intervention of interest was healthcare services that were nurse‐led. Publications were restricted to peer‐reviewed primary research, published in the English language from the year 2000 onwards. There was no restriction on study design. There was no comparison or control included in this review.

TABLE 1.

Eligibility criteria

| PICO framework | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population: | People experiencing homelessness, aged 18 years or more | Written in a language other than English |

| Intervention: | Nurse‐led care (registered nurse or nurse practitioner), in a community or hospital settings |

Services that are not nurse‐led, or do not have a substantial nurse‐led component Focus is on the practice of student nurses |

| Outcome: | Description of the nursing scope of practice | Published prior to the year 2000 |

| Peer‐reviewed primary research | Publication types: commentaries, editorials, discussion papers, reports (including technical reports), case reports/studies, research protocols, book sections/reviews, conference proceedings/papers/abstracts, books, letters to editor, interviews, doctoral theses, news |

A search of five databases was conducted on 30 November 2020, with the assistance of a research librarian. The included databases were CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PubMed and Scopus (File S2). Four preliminary searches were undertaken in all included databases to test the search terms. The initial search strategy included words associated with homelessness, such as ‘vulnerability’. These terms were removed as they proved too nonspecific and returned a considerable number of irrelevant results. The final search strategy included the following terms: homeless OR homelessness AND nurse‐led OR nurse practitioner* OR nursing intervention* OR advanced practice nurs*. The search strategy, as adapted for each database, is available in File S2, Tables S2–S6.

3.4. Search outcome

All search results were exported to EndNote (X9.3.3, Clarivate), and then uploaded to the online screening and data extraction tool, Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation Ltd). Duplicate records were discarded via automation using Covidence. The titles and abstracts were screened against the eligibility criteria by two independent reviewers (LM & JC). Disagreements at this stage were resolved through discussion between the two independent reviewers. The full‐text screening of the remaining papers was undertaken independently by the same two reviewers (LM & JC). Disagreements were resolved by referral to a third reviewer (MP). Once the final sample of included papers was identified, a hand search of the reference lists of these papers was undertaken. Papers that appeared eligible were retrieved and uploaded into Covidence and exposed to the selection process identified above.

3.5. Quality appraisal

The studies were appraised using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 18 (Hong et al., 2018). Two reviewers (LM & JC) independently undertook the quality assessment of the eligible studies and compared the results. A third reviewer (MP) then assessed each study, and disagreements were resolved through discussion between the three reviewers. An overall quality judgement was made for each study and is presented numerically.

3.6. Data abstraction

A data extraction form was developed and piloted by two authors (LM & JC) who independently extracted data from all included papers. The extracted data were compared for consistency, before being confirmed by a third reviewer (MP). Disagreements were resolved through a discussion between the three reviewers.

Data extracted from eligible studies included: author(s), year of publication, country, aim, study design, setting, sample size, participant characteristics, nurse‐led services provided and study results relating to the scope of practice and measures of impact on access to care.

3.7. Synthesis

Guidance for analysis and synthesis of included studies was sought from Popay et al. (2006). Given the range of study designs and methodologies, narrative synthesis was considered most appropriate. Studies were grouped according to study design for quality analysis and data extraction. Extracted data were synthesized and discussed narratively under themes according to the stated research questions: participant characteristics, the scope of practice and barriers and facilitators of access to care.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Study selection

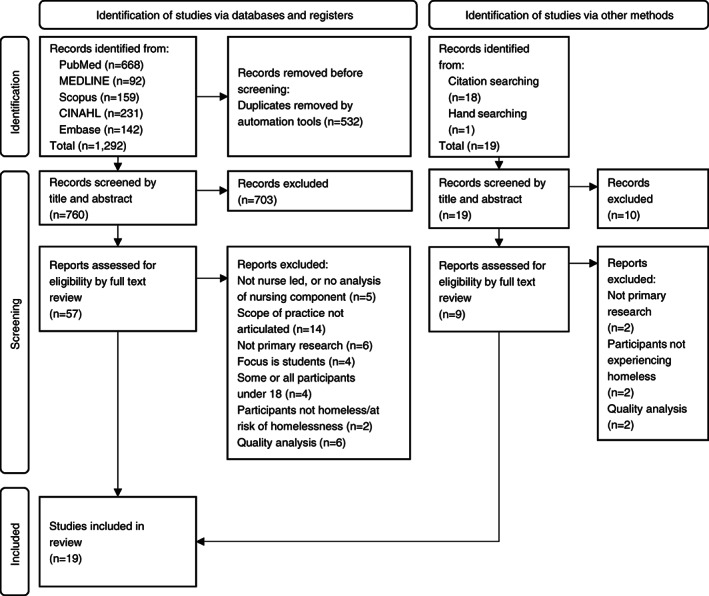

The initial database searches yielded n = 1292 records. Following deduplication and screening at the abstract title and then full text, n = 19 studies were included in the final sample. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of the screening process.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Five excluded studies initially appeared to meet the eligibility criteria and required disagreement resolution between two reviewers (LM & JC). In two studies (Brush & Powers, 2001; Simões‐Figueiredo et al., 2019), the focus was on nursing students, and for two studies (MacDonald, 2005; Perrett & Hams, 2013), the inclusion of participants experiencing homelessness appeared to be incidental rather than the focus. The fifth paper (Berg et al., 2005) did not describe the nursing scope of practice.

4.2. Study characteristics

The final analysis included 19 studies from the United States (n = 9), Australia (n = 4), the United Kingdom (n = 4) and Canada (n = 2), shown in Table 2. Twelve studies used a quantitative design, four a qualitative design and three used a mixed methods design. The studies used a combination of semi‐structured and open‐ended interviews, surveys, reviews of clinical notes and client information systems and tracking of outcomes including health, behaviour change and treatment completion outcomes. Ten studies focused on registered nurses, five on nurse practitioners and four on both registered nurses and nurse practitioners. All the studies were undertaken in outpatient or community settings. The total participant sample size was 6303 and ranged from n = 2 to n = 2707.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author(s) | Study aim | Design and Setting, participants | Nurse‐led services | Scope (skills, knowledge, attributes) | Access to care a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative studies | |||||

| Dorney‐Smith (2011), South London, United Kingdom | Describe an intermediate care pilot project in a homeless hostel; examine health outcomes and secondary care usage data; perform an economic evaluation | Descriptive quantitative, Jan‐Dec 2009, (n = 34) homeless hostel residents. 65% male, average age 39 years, average time homeless 8.5 years. Health outcome measures: EQ‐5D standardized instrument, SF‐12v2 health survey, SOCRATES scoring form and nurse dependency score | 6–12 weeks of complex case management and intensive support for clients at high risk of death or disability. Delivered in hostel setting, nurse onsite 9 am‐5 pm weekdays. 6–10 patient caseload. In compliment to established onsite health services | Physical health nursing; blood collection; mental health monitoring; alcohol reduction strategies; relapse prevention support; engagement, relationship and trust building; ad hoc counselling; emotional support; care planning in partnership with the client; client motivation and empowerment; interdisciplinary collaboration; referral to social and other health services; accompaniment and assertive advocacy at appointments | During the intervention period monthly averages of: hospital admissions ↓ 77%; emergency department presentations ↓ 52%; emergency department presentations by ambulance ↓ 67%. Hospital ‘did not attend’ rate ↓ 22%. 198 appointments made for clients. Significant impact on EQ‐5D, SF‐12 health survey and nurse dependency score. Universally positive client responses, particularly escort and advocate at out‐patient appointments |

| Dorney‐Smith (2007), London, United Kingdom | Assess the effect of a community matron model aimed at improving health outcomes and reducing health service use amongst residents of a homeless hostel | Quantitative before and after study in a homeless hostel. 13‐week case management with the clinical review. Acute care service use was tracked, health and quality of life were measured using EQ‐5D. n = 6 residents of the hostel. | Case management involving health screening and monitoring, care coordination, and support | Assistance with GP registration; health screening and health promotion; minor illness and minor assessment; provision of medications via Patient Group Directive or nurse prescribing rights; wound care; vaccination; referral to mental health, drug and alcohol, and specialist services, venepuncture and pathology collection; chronic disease management; sexual health and blood‐borne virus screening; smoking cessation support; emergency contraception | n = 2 achieved reduced acute care service usage; n = 1 requesting detoxification; n = 1 ceased alcohol consumption completely and moved to residential care for adults with disability; n = 1 moved to more appropriate accommodation; n = 2 showed improved EQ‐5D score. All participants stated to make key achievement due to the programme |

| Hooke et al. (2001), Sydney Australia | Describe services provided by nurse practitioners at a primary health clinic serving marginalized groups; assess clinical appropriateness and concordance with ‘best practice’ | Descriptive cross‐sectional, (n = 613) nurse practitioner‐led consultations, Sep 1994—Apr 1995. Patients; 77.3% female, 1.3% transgender, 54.3% aged 20–29 years, 46.3% injecting drug users | Primary health, sexual health, family planning, infectious disease service, counselling/psychosocial support, drug and alcohol service, harm minimization and street outreach | Venepuncture; pathology collection; pap smear; sexually transmitted disease screening; contraception; gynaecological conditions; alcohol and drug assessment; Hepatitis A and B vaccination; treat and manage constipation, diarrhoea, proctitis, nausea, sore eyes, skin complaints, urinary tract infections; wound care; breast and testicular exam | Over 95% of care (clinical assessment, management plan, outcomes review) provided by nurse practitioners was clinically appropriate. Expanded nurse practitioner scope of practice reduced the need for medical officer consultation time and medical officer caseload demand, leading to increased overall clinic capacity. Free, anonymous service on a drop‐in basis |

| Muirhead et al. (2011), Chattanooga, United States of America | Examine reasons for use of foot care services amongst adults experiencing homelessness |

Quantitative survey, convenience sample (n = 100) adults experiencing homelessness recruited at a community kitchen. 30% female, 76% rough sleeping, remainder in unstable housing. 80% unemployed, 9% never employed |

Nurse practitioner, student nurse and podiatrist, weekly foot care service after lunch at a community kitchen serving meals to adults experiencing homelessness | Health history; foot examination; foot health promotion; foot hygiene and nail care | 49% were unaware of foot service, 16% had used the foot service and of those 88.2% were satisfied. 62% were too embarrassed of their feet to use the service. 25% used the emergency department for foot‐related problems. Clinic present at the community kitchen, convenient time, no cost, no appointment needed, showers and towels for self‐care provided |

| Murphy et al. (2015), United States of America | Improve the cardiovascular health of women experiencing homelessness and African American older adults using 2 health assessment and health promotion tools; provide a model for translating evidence into practice | Quantitative, pre‐ and post‐intervention health screening, (n = 18) adults with cardiovascular risk, n = 10 were women experiencing homelessness. Recruited from two facilities: urban senior centre and residential facility for women experiencing homelessness and substance use issues | Heart Healthy Programme: nurse practitioner led monthly service for 6 months using American Heart Association My Life Check and Life's Simple 7 tools, to improve cardiovascular health |

Pre‐programme screening with My Life Check: vitals, blood pathology, smoking status, diet, physical activity, health literacy assessment. Coaching and motivational interviewing; education on the Life's Simple 7 guide for a lifestyle change and goal setting. Education on self‐monitoring tools, for diet, activity, weight monitoring and blood glucose |

In women experiencing homelessness: slight increase in risk, though a slight decrease in blood pressure, blood glucose and smoking rates. The programme felt safe and comfortable, and convenient to access. Women experiencing homelessness did group coaching sessions, which added social support. Written communication tailored to the education level of participants |

| Nyamathi, Branson, et al., 2012, Santa Monica, California, US | Assess the impact of a nurse‐led health promotion intervention, and an artist‐led art program on decreasing the use of drugs and alcohol amongst young adults experiencing homelessness | Randomized pilot study, (n = 154) young adults experiencing homelessness (18–25 years), recruited from a drop‐in centre in Santa Monica. 70% male, mean age 21.2 years, 58% white | Nurse‐led health promotion programme focused on Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) and hepatitis, delivered through three 45‐min sessions | Group education sessions on hepatitis B and C and HIV infection, transmission and prevention; hepatitis vaccination; training in self‐management and communication skills, overcoming barriers to completion of vaccine series, reducing drug use behaviour, developing relationships, activities and social networks | Reduction in use of marijuana, alcohol, and binge drinking in both groups. Reduction in methamphetamine, cocaine and hallucinogen use in the nurse‐led group at 6 months. Familiar space for participants. Sessions were culturally relevant, interactive, opportunities to ask questions and share experiences |

| Nyamathi et al. (2009), Skid Row Los Angeles, US | Evaluate the effectiveness of nurse‐case‐managed intervention, compared with two standard programmes, on completion of a 6‐month hepatitis A and B vaccine series in adults experiencing homelessness | Randomized, prospective, quasi‐experimental, (n = 865) sheltered adults experiencing homelessness. Recruited from 12 homeless shelters, 4 residential drug treatment sites and outdoor locations. 77% male, 69% African American, mean age 42 years |

Nurse‐led hepatitis health promotion programme and case management. Participants received different levels of intensity of nursing input in terms of case management, support and education |

Venepuncture; blood‐borne virus serology, post‐test counselling; blood‐borne virus education on infection, transmission, diagnosis and prevention; hepatitis vaccination; coaching on self‐esteem, communication, coping strategies, reduction of risky substance use and sexual practices, addressing barriers to completing vaccine course; needs assessment; referrals | 97% verbalized intent to complete vaccine series. Nurse‐case‐managed clients had significantly improved completion rates. Education and client tracking are important for enhancing adherence. Carried out at the site of recruitment, areas accessible and known to participants. Blood‐borne virus screening allowed for medical referral |

| Nyamathi, Marlow, et al. (2012), Skid Row, Los Angeles, United States of America | Determine predictors of vaccine course completion in adults experiencing homelessness with a history of incarceration, who had participated in a study of the impact of nurse case management on hepatitis A and B vaccine course completion | Retrospective analysis, subgroup of participants from a larger study, (n = 297) adult males experiencing homelessness discharged from prison. Recruited from 12 homeless shelters, 4 residential drug treatment sites and outdoor locations. 70% aged >40 years, 70% African American | Nurse‐led hepatitis health promotion programme and case management. Participants received different levels of intensity of nursing input in terms of case management, support, and education | Venepuncture; blood‐borne virus serology, post‐test counselling; blood‐borne virus education on infection, transmission, diagnosis and prevention; hepatitis A and B vaccination; Coaching on self‐esteem, communication, coping skills/strategies, reduction of risky substance use and sexual practices, addressing barriers to completing vaccine course; needs assessment; referrals | Nurse‐led intervention is not a predictor of course completion in this subgroup. Participants are more likely to complete the vaccine series: older, homeless >1 year. Participants less likely to complete: had attended a self‐help programme, and reported binge drinking |

| Nyamathi et al. (2006), Skid Row, Los Angeles, United States of America | Compare the effectiveness of a nurse‐case‐managed intervention programme vs. standard care on completion of 6‐month latent tuberculosis (TB) infection treatment programme; compare the impact on TB knowledge | Prospective, two‐group, site‐randomized. (n = 520) adults experiencing homelessness were recruited from emergency homeless shelters and residential recovery shelters in Skid Row, LA from 1998 to 2003 | Nurse‐led TB health promotion programme and case management. Participants received different levels of intensity of nursing input in terms of case management, support, and education | Promote coping and communication skills, feelings of self‐worth and readiness for change; education on TB and HIV risk reduction, problem‐solving, behaviour change and social relationship building; culturally competent communication; facilitate access to community resources; accompany to medical and social service appointments | 62% intervention group completed treatment vs 39% control group. Intervention group: greater improvement in TB knowledge vs control (3.8 vs 2 point increase in 13‐item instrument). Failure to complete treatment is associated with lifetime injecting drug use, daily substance use and recent hospitalization |

| Nyamathi et al. (2008), Skid Row, Los Angeles, United States of America | Compare the effectiveness of a nurse‐case‐managed intervention programme vs. standard care on completion of latent TB infection treatment in subsamples of people experiencing homelessness, with characteristics identified as risks for non‐adherence, such as daily drug use | Retrospective subgroup analysis. (n = 520) adults experiencing homelessness were recruited from emergency homeless shelters and residential recovery shelters in Skid Row, LA from 1998 to 2003 |

Nurse‐led TB health promotion programme and case management. Participants received different levels of intensity of nursing input in terms of case management, support, and education |

Promote coping and communication skills, feelings of self‐worth and readiness for change; education on TB and HIV risk reduction, problem‐solving, behaviour change and social relationship building; culturally competent communication; facilitate access to community resources; accompany to medical and social service appointments | In the intervention group, women, those in fair to poor health and experiencing emotional distress or depression: approximately 30% higher treatment completion vs control. Results adjusted for cofounders showed intervention to be effective for African Americans, daily drug and alcohol users, and men |

| Savage et al. (2008), Southwest Ohio, US | Assess the impact of care from a nurse‐led clinic on specific health outcomes in adults experiencing homelessness | Pilot study, pre (n = 69) and post (n = 43). Adults experiencing homelessness, recruited from a nurse‐led clinic in a homeless shelter, Sep 2003‐Apr 2005. 95‐item structured health survey, SF‐12v1, AUDIT. Ages 22–67 years, 94% male, 1 month‐10 years homeless | Nurse‐led primary health clinic, 2 evenings a week, in a church‐based homeless shelter | Nursing assessment; health education; nursing interventions; referral for treatment; basic wound care; foot care; symptom management; health needs addressed immediately, or clients referred to primary care clinics | Significant improvement in access to, and perceived availability and quality of care. Significant improvement in mental health, vitality and substance use variables. Slight improvement in social functioning. Clinic in a familiar setting. Cooperative approach between nurse and client. No appointment or payment is needed. Actively encouraging clients to seek care early |

| Segan et al. (2015), Melbourne, Australia | Examine the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of a smoking cessation programme for people experiencing homelessness | Quantitative before and after study in a homeless persons' programme in Melbourne. 12‐ week, smoking cessation programme with pharmacotherapy and support. Tobacco use and mental health outcomes assessed. N = 49 clients, 63% male, mean age 48 yrs | Smoking cessation treatment as per Quit Victoria training. Holistic approach encompassing behavioural, mental health and social factors | Assessment of smoking behaviour, pharmacotherapy use and mood; appropriate provision of cognitive behavioural therapy strategies with the dual goal of reducing stress. Fill and dispense prescriptions. Carbon monoxide monitoring | Pharmacotherapy: 69% used any, 39% used for 5–12 weeks. 61% used Quitline. 53% attended 2–6 GP appointments. 33% attempted quitting by 6 months. 29% reduced smoking >50% at 6 months. Self‐reported increase in physical and mental health. Programme administered in a familiar, supportive environment by trusted nurses. No cost to the client |

| Qualitative studies | |||||

|

Paradis‐Gagné and Pariseau‐Legault (2020), Quebec and Ontario, Canada |

Gain a better understanding of how nurses experience their practice with people experiencing homelessness, specifically looking at social disaffiliation and stigma | Critical ethnography, semi‐structured interviews, (n = 12) outreach nurses providing primary care to people experiencing homelessness. 92% female, 25% nurse practitioner or student nurse practitioner | Nurse‐led primary care and addiction programmes are delivered in homeless shelters, clinics, community organizations and street outreach | Knowledge of psychosocial and medical issues; adapt clothing, self‐presentation and vocabulary; rapport and trust building based on empathy; cultural understanding and sensitivity; personalized, non‐judgemental approach; trauma‐informed approach; situational and environmental awareness; understanding of prejudice and stigma; advocacy to address stigma in healthcare settings; inter‐organizational knowledge and partnerships; inter‐disciplinary working relationships. | Nurses worked with community groups and peer helpers to develop trust and relationships with clients, address attitudinal and bureaucratic barriers to access. Care is carried out where clients already are. No health card is required. Actively helping clients navigate the health system. Nurses as the link between disaffiliated clients and mainstream services. |

| Paradis‐Gagné et al. (2020), Quebec and Ontario, Canada | Explore the structure and distinguishing characteristics of outreach nursing for people experiencing homelessness | Critical ethnography, semi‐structured interviews, (n = 12) outreach nurses providing primary care to people experiencing homelessness. 92% female, 25% nurse practitioner or nurse practitioner students | Nurse‐led primary care is delivered in homeless shelters, low threshold access clinics, community organizations, and street outreach | Knowledge of psychosocial and medical issues; expanded care coordination, accompaniment and referral to services; coaching approach to care; flexibility, adaptability, resourcefulness and patience; tolerance of uncertainty; adapt clothing, self‐presentation and vocabulary; person‐centred, non‐judgemental, open, respectful communication; trauma‐informed approach; advocacy against stigma; recognizing client's strengths; relationship building with the client, other health professionals and organizations | Horizontal decision making between professionals and with clients increased approachability of the service. Nurses have an advocacy role that built trust and broke down stigma. Building relationships, re‐affiliating people with mainstream services. Nurses provide continuity of care and overcome organizational barriers as the client navigates the system |

| Poulton et al. (2006), Northern Ireland | Explore the effectiveness of a community nurse practitioner working with clients experiencing homelessness; look at the effectiveness of the role using a “public health framework.” | Qualitative, in‐depth case study, (n = 1) community nurse practitioner working with people experiencing homelessness in the inner city area. Semi‐structured interviews (n = 2) with a nurse practitioner and line manager | Nurse‐led outreach service with care coordination to people experiencing homelessness. Included visits to hostels | Communication; holistic assessment; non‐stigmatized approach; establishment of trust; care coordination; referrals; develop public health initiatives based on health policy directives; promote client health care needs; advocacy; health needs assessment; lead and coordinate disease health promotion programmes (diabetes, dental, ophthalmic); promote access and equity; develop patient group directives for immunisations and prescription medicines; medication prescribing; wound care; vaccine administration. | Facilitate registration with a general practitioner and dentist. Care coordination between other health services helps with continuity of care. Care done as outreach or in hostels, less need for the client to seek care. Consistency of contact and trust building facilitates access. Actively increasing awareness of services available and accessible to clients. Addressing stigma to reduce exclusion from care in mainstream services. Hostel clinics have routine screening programmes for early pathology detection |

| Seiler and Moss (2012), Northeast and Southeast Wisconsin | Gain insight into the unique experiences of nurse practitioners who provide health care to the homeless. | Qualitative phenomenology, open‐ended interviews, (n = 9) nurse practitioners providing clinic‐based care to people experiencing homelessness. 89% female, 11% African American | Nurse‐led primary health service in clinics serving people experiencing homelessness | Value and believe in justice and equity; respectful, empathy‐based communication and listening skills; personality traits, such as patience, creativity, resourcefulness, sincerity; self‐reflection, recognizing one's own biases and assumptions; trauma‐informed approach; tailored health education; client empowerment; relationship building | Increased understanding of client's lives improves the effectiveness of care. Outreach facilitates access for socially isolated clients. Establishing trust, establishing a relationship of reciprocity, can help re‐affiliate clients with mainstream services. Actively assist clients to navigate the healthcare system improves access to appropriate care and reduces exclusion |

| Mixed methods studies | |||||

| Goeman et al. (2019), Melbourne Australia | Implement, refine and evaluate an assertive Community Health Nurse model of support for people experiencing, or at risk of, homelessness that aims to improve access to health and social care services. | Mixed methods. Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (n = 15), focus group (n = 8), key stakeholders in specialist homeless services and members of the Community Health Nurse project team. Quantitative: review of clinical case notes and client information system, (n = 39) Community Health Nurse clients. Setting: Community Health Nurse clinic and outreach service located in southern metro Melbourne. | Holistic primary healthcare; clinic‐based care and assertive outreach to people experiencing homelessness. | Inter‐service and interdisciplinary collaboration; service innovation; client empowerment; advocacy; social equity and rights approach; emotional support; health education; wound care; assessment skills – substance use, mental and physical health; needs assessment and referral (clinical, social, emotional, financial); organize and accompany to appointments, organize transport; client monitoring and follow up; autonomy; flexibility; reliability; accountability; trust building; empathy, understanding of context and impact of homelessness | Clients willing to engage with services after an average of 7 Community Health Nurse visits; 18 clients independently accessed services after 9 weeks; services accessed were general practitioner (87% of those who needed it), psychiatrist (77%), psychologist (47%), housing (85%), optometry, community mental health, welfare (Centrelink), legal aid. Stakeholders reported collaboration with the Community Health Nurse allowed all providers to improve their service delivery and increased client service access |

| McGregor et al. (2018), North London, United Kingdom | Assess the impact of sexual health clinics on contraceptive uptake, sexual health screening, and residents' and staff knowledge and attitudes towards sexual health | Mixed methods. Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (n = 22; 14 patients, 8 staff). Quantitative: survey (n = 70 patients), routine service data (n = 161 patients, 367 consults). Recruited from 3 homeless hostels, May 2012–May 2013. 54% female, aged 19–76 years (mean = 38) | Nurse‐led specialist reproductive sexual health care, weekly clinics in the hostels from 12.30–3.00 pm. Clinics supported by health promotion specialists who increased sexual health awareness | Sexually transmitted disease screening and treatment; contraception counselling and provision, including implants and injections; cervical cytology; blood‐borne virus testing, including HIV and hepatitis; vaccination; pregnancy testing; health promotion and education | 59 instances of sexually transmitted infections were diagnosed, including 3 cases of syphilis; 107 HIV screening tests performed (nil positive); 96 hepatitis screening tests (5 positives); 28 females received contraception counselling; 5 pregnancy tests performed (1 positive). Qualitative data identified barriers related to service access. Nil need to register with a general practitioner, services in place of residence (familiar to clients), nil appointment needed |

| Roche et al. (2018), Sydney, Australia | Explore the primary health needs and service use of men experiencing homelessness, including the men's views of the impact of care provided and approaches to facilitate more effective care | Descriptive mixed methods. Quantitative: clinical case data (n = 2707) for 7‐year period. Qualitative: cross‐sectional survey (n = 40), men experiencing homelessness attending a primary health clinic in a homeless hostel in Sydney. Aged 27–79 years, 72.5% single, 10% of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin, 26% sleeping rough | Nurse‐led primary health clinic located in a homeless hostel, addressing mental and physical health complaints. Open seven days/week | General medical and mental health assessment and care; medication administration, facilitate and dispense prescriptions; wound care; treatment of eye, ear and skin conditions; case management for complex needs; referrals to other health professionals and specialist services; making appointments and accompanying clients to them | 90% attended clinic >20 times in 12 months. Referrals made: emergency department, general practitioner, mental health services, dentists, medical specialists, alcohol and drug services. Participant views: 82% ‐ service helps them avoid emergency department; 95% ‐ clinic eased access to other services; 52% ‐ clinic facilitated access to care. Tailored to education and health literacy levels. Active encouragement to seek care earlier. Addressing fears of seeking care and lack of knowledge. Help clients feel supported and listened to, builds trust. Safe and familiar setting |

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; TB tuberculosis.

Access to care measured by the approachability, acceptability, affordability, appropriateness, availability of the nurse‐led services.

4.3. Risk of bias in studies

The methodological quality of the included studies is summarized in Table 3. Of the randomized studies, each had insufficient detail about allocation concealment and one lacked detail on randomization and programme adherence (Nyamathi, Branson, et al., 2012). The two non‐randomized quantitative studies (Dorney‐Smith, 2011; Murphy et al., 2015) had incomplete outcomes data. In three of the quantitative descriptive studies (Muirhead et al., 2011; Nyamathi et al., 2008; Savage et al., 2008), it was not possible to assess how representative the samples were. Of the mixed methods studies, it was difficult to judge whether the quantitative sample was representative (Goeman et al., 2019). McGregor et al. (2018) reported a low response rate.

TABLE 3.

MMAT quality assessment ratings of all included studies, table adapted from Li et al. (2020)

| Qualitative | 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | 1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | MMAT criteria satisfied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paradis‐Gagné and Pariseau‐Legault (2020) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100% |

| Paradis‐Gagné et al. (2020) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100% |

| Poulton et al. (2006) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100% |

| Seiler and Moss (2012) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100% |

| Quantitative randomized controlled trials | 2.1. Is randomization appropriately performed? | 2.2. Are the groups comparable at baseline? | 2.3. Are there complete outcome data? | 2.4. Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? | 2.5 Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? | MMAT criteria satisfied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nyamathi, Branson, et al., 2012 | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | 40% |

| Nyamathi et al. (2009) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | 80% |

| Nyamathi et al. (2006) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | 80% |

| Quantitative non‐randomized | 3.1. Are the participants representative of the target population? | 3.2. Are measurements appropriate about both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? | 3.3. Are there complete outcome data? | 3.4. Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? | 3.5. During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? | MMAT criteria satisfied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dorney‐Smith (2011) | Yes | Cannot tell | No | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | 20% |

| Dorney‐Smith (2007) | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 60% |

| Murphy et al. (2015) | Yes | Yes | No | Cannot tell | Yes | 60% |

| Segan et al. (2015) | Yes | Cannot tell | No | No | Yes | 40% |

| Quantitative descriptive | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? | 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? | 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? | 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | MMAT criteria satisfied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hooke et al. (2001) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100% |

| Muirhead et al. (2011) | Yes | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | No | 20% |

| Nyamathi, Marlow, et al. (2012) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | 80% |

| Nyamathi et al. (2008) | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | 60% |

| Savage et al. (2008) | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | 60% |

| Mixed methods | 5.1. Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? | 5.2. Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | 5.3. Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | 5.4. Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | 5.5. Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? | MMAT criteria satisfied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goeman et al. (2019) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 80% |

| McGregor et al. (2018) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 80% |

| Roche et al. (2018) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 80% |

4.4. Results of syntheses

The results of the included papers were synthesized narratively in relation to the participant characteristics, and findings related to the scope of practice of nurse‐led services, and the influence of nurse‐led services on access to care. Findings associated with influence on access to care were identified primarily in the qualitative and mixed methods studies, all of which met 80% or more of the MMAT criteria, with the exception of two studies (Dorney‐Smith, 2011; Muirhead et al., 2011). The inclusion of these two studies did not impact the overall synthesis as neither paper contained unique findings related to influence on access, instead, all findings were consistent with those contained in the more methodologically sound papers.

4.4.1. Participant characteristics

In two Australian studies, adults of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin comprised 8% (Goeman et al., 2019) and 10% (Roche et al., 2018) of the sample. Education levels varied, with high school completion rates ranging from 35% (Roche et al., 2018) to 74% (Nyamathi et al., 2009). Unemployment rates ranged from 80% (Muirhead et al., 2011) to 100% (Roche et al., 2018). Two studies reported the proportion of participants sleeping rough to be 26% (Roche et al., 2018) and 33% (Goeman et al., 2019). Other social determinants reported were: 60% of participants with a history of incarceration, 29% with experience in foster care as a child (Nyamathi, Branson, et al., 2012), 51% on government assistance (Nyamathi, Marlow, et al., 2012) and 83% in an American‐based study with no health insurance coverage (Savage et al., 2008).

Rates of mental ill health ranged from 61% (Dorney‐Smith, 2011) to 90% (Goeman et al., 2019; Roche et al., 2018). Substance use ranged from 44% (Goeman et al., 2019) up to 93% (Dorney‐Smith, 2011) of participants. Rates of physical ill health ranged from 56% (Dorney‐Smith, 2011) to 64% (Goeman et al., 2019), with common conditions including: blood‐borne viruses, liver and kidney disease, skin and foot problems, respiratory disease, brain injury and seizures (Roche et al., 2018), cardiovascular disease, diabetes (Muirhead et al., 2011) and severe infections (Dorney‐Smith, 2011). Comorbidity was common, with 87.5% of participants in one study reporting more than one health issue (Roche et al., 2018), and in another, the average number of clinical conditions per client was 10.5 (Dorney‐Smith, 2011). Smoking was the most commonly reported health risk behaviour, with rates between 70% (Muirhead et al., 2011) and 90% (McGregor et al., 2018; Nyamathi, Branson, et al., 2012; Roche et al., 2018; Savage et al., 2008). Daily illicit drug use ranged from 26% (Nyamathi et al., 2006) to 54% (Roche et al., 2018), and daily use of alcohol from 14% (Nyamathi, Marlow, et al., 2012) to 20% (Roche et al., 2018).

4.4.2. Scope of practice

Nurses' scope of practice identified in the included studies was broad and findings relating to skills, knowledge and attributes are reported here. Contexts about the physical settings and purpose of the nurse‐led services were various. For example, a foot care clinic is delivered in a community kitchen (Muirhead et al., 2011), primary healthcare and sexual healthcare services are provided in both a clinic setting and through street outreach (Hooke et al., 2001). This heterogeneity meant that it was not possible to evaluate the influence of context on the scope of practice and draw any firm conclusions.

The specific clinical skills commonly reported included physical and mental health assessments, pathology collection, wound care, and vaccination. Several studies reported nurses' skills in case management in relation to providing patient support, care planning, care coordination, referrals to other healthcare professionals and services and accompanying patients to appointments. Other skills identified were health promotion and health education.

Nurses' knowledge important in delivering services to people experiencing homelessness incorporated an understanding of both medical and psychosocial problems, in particular an understanding of the context and impact of homelessness, as well as knowledge of the interagency support available. Further, it was reported as important for nurses to have the requisite knowledge to undertake a range of health and social assessments, and the capacity to recognize a range of health conditions, particularly chronic conditions.

Several attributes were identified as important for nurses to possess and embody in facilitating a therapeutic relationship with people experiencing homelessness and increasing access to healthcare. Studies indicated the importance of a trauma‐informed approach in terms of acknowledging the trauma experienced by people experiencing homelessness and the impact on well‐being (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Skills, knowledge and attributes identified

| Skills | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Clinical Assessment skills2,3,4,6,7,10,13,15,17,18,19 General physical health nursing1,10 Venepuncture1,2,4,6,7,19 Pathology collection, such as blood, swabs, urine1,2,4,6,7,19 Symptom management, including constipation, diarrhoea, proctitis, nausea, sore eyes, skin problems, urinary tract infections, ear problems2,10,17 Wound care2,10,13,15,17,19 Foot hygiene and nail care3,10 Vaccination2,5,6,7,13,16,19 Medication prescribing13,19 Facilitate access to prescriptions and medication administration17,18 Mental health monitoring and care1,17 Pap smear2 Cervical cytology16 Sexually transmitted disease screening2,16,19 Blood‐borne virus screening16,19 and post‐test counselling6,7 Contraception provision and counselling2,16,19 Management of gynaecological problems2 |

Pregnancy testing16 Chronic disease management19 Support , planning and management Alcohol and other drug use reduction strategies1 Counselling and emotional support1,15 Case management17,19 Care planning and coordination1,12,13,15,17,19 Referrals to other healthcare professionals and services1,6,7,10,12,13,15,17,19 Accompany clients to appointments1,8,9,12,15,17 Coaching approach to care,4,12 including self‐management, coping, communication and social skills, reducing risk behaviour, self‐esteem, problem solving5,6,7,8,9 Motivational interviewing (exploring the person's motivations for their behaviour, empowering them to change in a way that's acceptable to them)4 Facilitate access to community resources8,9 Client monitoring and follow up15 |

Health promotion and education General health education10,15,16 Tailored health education14 Education on blood‐borne viruses, TB and HIV5,6,7,8,9 Lifestyle change4,18 Smoking cessation support18,19 Self‐monitoring tools, such as for diet, weight and activity levels4 Promotion of foot care practices3 Promotion of health behaviours with clients13,16,19 Promote access and equity, promote the health needs of clients with other professionals and services13 Lead and coordinate disease health promotion programmes, such as for diabetes, dental and ophthalmic health13 Policy and service level change Service innovation15 Develop patient group directives for vaccinations and prescription medications (the nurse can administer without the involvement of a prescriber)13 Develop public health initiatives based on current health policy directives13 |

| Knowledge | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Knowledge of both medical and psychosocial problems11,12 Understanding of the context and impact of homelessness on the individual15 Inter‐organizational knowledge11 Knowledge to undertake the following assessments:

|

|

Knowledge or ability to recognize the following conditions:2,10,17

|

| Attributes | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Interdisciplinary collaboration1,11,12,15 Inter‐organizational collaboration11,12,15 Engagement, relationship and trust building with clients1,11,12,13,14,15 Personalized, client‐centred approach11,12 Listening skills14 Communication,13 including empathy based14 and culturally competent8,9 communication Shared decision making with the client1 Recognizing the client's strengths12 Trauma‐informed approach11,12,14 |

Understanding of stigma and prejudice11 Client motivation and empowerment1,14,15 Advocacy against stigma, including advocacy when accompanying clients to appointments1,11,12,13,15 Cultural understanding and sensitivity11 Situational and environmental awareness11 Adapt clothing, vocabulary and self presentation to the Outreach or street environment11,12 Self‐reflection to recognize one's own biases and assumptions14 |

Belief in justice and equity14 Attitude and personality traits:

|

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; TB, tuberculosis.

Note: References: 1Dorney‐Smith (2011); 2Hooke et al. (2001); 3Muirhead et al. (2011); 4Murphy et al. (2015); 5Nyamathi, Branson, et al. (2012); 6Nyamathi et al. (2009); 7Nyamathi, Marlow, et al. (2012); 8Nyamathi et al. (2006); 9Nyamathi et al. (2008); 10Savage et al. (2008); 11Paradis‐Gagné and Pariseau‐Legault (2020); 12Paradis‐Gagné et al. (2020); 13Poulton et al. (2006); 14Seiler and Moss (2012); 15Goeman et al. (2019); 16McGregor et al. (2018); 17Roche et al. (2018); 18Segan et al. (2015); 19Dorney‐Smith (2007).

4.4.3. Influence on access to care

Findings were themed into barriers and facilitators in regard to their influence on access to healthcare.

Barriers

Barriers relating to the healthcare system included: a complex, fragmented system which is difficult to navigate (Goeman et al., 2019; Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020), rigid appointment or access times (McGregor et al., 2018; Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020) and administration barriers (availability), such as needing a healthcare card (affordability) or a fixed address (Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020; Paradis‐Gagné & Pariseau‐Legault, 2020). It was reported that limitations on the scope can be experienced by services when funding is tied to specific activities (Goeman et al., 2019), and by nurses when practising under restrictive protocols (Poulton et al., 2006), resulting in service gaps (availability).

A lack of awareness about homelessness amongst healthcare professionals acted as a barrier to the appropriateness of service provision (Goeman et al., 2019; Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020; Paradis‐Gagné & Pariseau‐Legault, 2020; Poulton et al., 2006). Stigmatizing and prejudiced attitudes amongst healthcare professionals (approachability) were reported to be a further barrier (McGregor et al., 2018; Paradis‐Gagné & Pariseau‐Legault, 2020; Poulton et al., 2006), one which can ultimately result in exclusion from care (Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020). Wariness and distrust (approachability, acceptability, appropriateness) of mainstream services can discourage clients from seeking care (Dorney‐Smith, 2011; Goeman et al., 2019; McGregor et al., 2018; Poulton et al., 2006), with three studies reporting that this stemmed from negative previous experiences (Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020; Paradis‐Gagné & Pariseau‐Legault, 2020; Seiler & Moss, 2012).

On the part of the client, they may lack physical or geographical access to services (McGregor et al., 2018), or sufficient knowledge about health (availability) (McGregor et al., 2018). Competing priorities may take precedence over seeking healthcare, such as finding a bed for the night or a meal (Muirhead et al., 2011; Seiler & Moss, 2012), or substance use (McGregor et al., 2018). Further impacting a client's ability to access care can be a lack of access to resources (Goeman et al., 2019; Seiler & Moss, 2012), or reduced cognitive capacity due to mental illness, substance use or cognitive impairment (Seiler & Moss, 2012).

4.4.4. Facilitators

A range of factors was reported to act as facilitators for achieving increased access. With regard to the client‐nurse relationship, this included: using a trauma‐informed approach (Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020; Paradis‐Gagné & Pariseau‐Legault, 2020; Seiler & Moss, 2012) to build trust (Goeman et al., 2019; Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020; Paradis‐Gagné & Pariseau‐Legault, 2020; Poulton et al., 2006; Roche et al., 2018; Seiler & Moss, 2012), being consistent (Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020; Paradis‐Gagné & Pariseau‐Legault, 2020; Poulton et al., 2006; Roche et al., 2018), taking time to engage with the client (Dorney‐Smith, 2011; Goeman et al., 2019; Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020; Seiler & Moss, 2012) and building an understanding of the client's history and needs (Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020;Poulton et al., 2006; Seiler & Moss, 2012) (appropriateness, acceptability, approachability). Also reported as important were the self‐presentation, communication style, attitude of the nurse (Poulton et al., 2006; Seiler & Moss, 2012) and the ability to adapt self‐presentation, in terms of what nurses wore and their general demeanour, to the street or outreach environment (Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020; Paradis‐Gagné & Pariseau‐Legault, 2020) (approachability).

In terms of nursing clinical practice, facilitators noted were: the ability to be adaptable to overcome organizational barriers and affiliate people with mainstream services (Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020) (availability); autonomous decision making to promote access to care (Goeman et al., 2019; Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020; Poulton et al., 2006); flexible in their practice to respond appropriately to circumstances as they arose in the delivery of unscheduled care (Goeman et al., 2019; Poulton et al., 2006), and a scope of practice that is broad, holistic and inclusive of non‐health issues, such as knowledge and skills related to social and housing issues (Goeman et al., 2019; Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020; Poulton et al., 2006; Seiler & Moss, 2012) (availability). Client support was highlighted as important, such as: helping the client navigate a complicated healthcare system (Goeman et al., 2019; Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020), promoting knowledge of health (McGregor et al., 2018; Seiler & Moss, 2012) and service availability (Muirhead et al., 2011; Poulton et al., 2006) and promoting client autonomy (Goeman et al., 2019; Seiler & Moss, 2012). In addition, both clients and nurses highlighted the value of accompanying clients to appointments (Dorney‐Smith, 2011; Goeman et al., 2019; Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020), advocating against stigma (Dorney‐Smith, 2011; Goeman et al., 2019; Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020; Poulton et al., 2006) and educating other healthcare professionals about the impacts and barriers stemming from homelessness (Goeman et al., 2019; Poulton et al., 2006) (approachability, appropriateness, acceptability).

Other facilitators were: nurses having knowledge of the support services available to the client (Goeman et al., 2019), building professional relationships, fostering trust (Goeman et al., 2019; Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020) and collaboration with other healthcare professionals and services (Goeman et al., 2019; McGregor et al., 2018; Paradis‐Gagné et al., 2020; Poulton et al., 2006).

5. DISCUSSION

This paper reports a scoping review of the scope of practice of nurse‐led services and the influence on access to care for people experiencing homelessness. Findings suggest that a broad range of skills are required of nurses to improve access to care for this marginalized population. The skills, knowledge and attributes ranged from the complex, such as practising with a level of autonomy and complex case management, to the simple, such as accompanying people to appointments. The most influential aspects of the scope of practice in terms of facilitating access to care appeared to be the attributes of the nurse. Embodying the attribute of respect, engendering trust and adopting a trauma‐informed approach appeared to be critical in engaging people experiencing homelessness. Once a therapeutic relationship was established, the skills and knowledge of the nurses' scope of practice appeared to be vital to optimizing access to healthcare.

The skills, knowledge and attributes identified in the included studies provide an understanding of what might be important to include in an educational framework to support nurses providing healthcare to people experiencing homelessness. In designing an organizational framework to support optimizing the nursing scope of practice, findings suggest it is important that funding of nursing roles allows for flexibility in the model of care adopted and reduces the restrictive nature of protocols. Improving the awareness of all healthcare professionals of the needs of people experiencing homelessness was also identified as important.

There is one prior systematic review of interventional studies relating to nurse‐led care for people experiencing homelessness (Weber, 2019). Review findings suggested nurse‐led services were effective in engaging people experiencing homelessness in health‐seeking behaviours. The review highlighted that despite the potential of nurse‐led services to improve the quality of life of people experiencing homelessness, there is a limited quantity of literature focused on nurse‐led practice with homeless populations. The present review adds to the research literature by building an understanding of the specific characteristics of the nursing scope of practice that facilitate access to care, with the hope that these findings can be used to support nurses in optimizing their scope of practice when caring for people experiencing homelessness.

5.1. Implications for education, policy and clinical practice

The development of an education programme to optimize the scope of practice of nurses providing healthcare to people experiencing homelessness is timely on three counts. First, in 2019, the Australian Government funded an ‘Independent Review of Nursing Education – Educating the Nurse of the Future’ (Schwartz, 2019). The process of the Independent Review involved four underpinning literature reviews and a national consultation of nurses and midwives in Australia. Findings of the review suggest there is too great a focus on acute care, rather than chronic disease prevention, in pre‐registration nursing programmes, and an absence of primary healthcare in Master of Nurse Practitioner programmes (Schwartz, 2019). A key recommendation of the review stated that nursing education at all levels must reflect national health priorities, particularly prepared to provide mental health and primary health care.

Second, the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia are undertaking a consultation about the introduction of a registered nurse endorsement for scheduled medicines partnership prescribing (Nursing & Midwifery Board of Australia, 2018). Such an initiative would substantially enhance the capacity of registered nurses to improve access to medications for people experiencing homelessness, particularly in circumstances where they could continue medications in the management of chronic illness or initiate medications for minor illnesses. In the United Kingdom, health professional roles have extended to include non‐medical prescribing in their scope of practice. Evidence shows this has been successful in increasing timely access to needed medications and treatments and allowing for more efficient management of minor and chronic illnesses, thereby reducing the risk of deterioration and the need for acute care (Royal College of Nursing Policy and International Department, 2014). Particularly relevant to the Australian context, nurse prescribing in the United Kingdom has allowed for increased autonomy and independence for nurses working in low‐resource or geographically isolated areas, where a general practice surgery or hospital may be some distance away (Royal College of Nursing Policy and International Department, 2014).

Third, as previously mentioned, rising rates of homelessness are a worldwide problem (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2020), even prior to the onset of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Though we do not fully understand the impact of COVID‐19 on homelessness and access to healthcare, early evidence suggests that the health and social risks already experienced by marginalized groups are further exacerbated by the pandemic (Flook et al., 2020). Therefore, it is likely that nurses practising in any context will encounter people experiencing or at risk of homelessness and having skills, knowledge and attributes to provide healthcare to this population is important. In the next stage of this project, these scoping review findings will be used to develop a national survey to explore the scope of practice that nurses perceive will facilitate access to healthcare for those experiencing homelessness.

5.2. Limitations

This scoping review has some limitations. Using articles and databases in the English language meant the relevant non‐English studies could not be identified. The search was limited to peer‐reviewed publications and the grey literature was not searched. Limiting eligible results to participants 18 years and older meant excluding potentially important studies because they focused on women and children (D'Amico & Nelson, 2008; Hatton et al., 2001). The descriptive nature of this review means that no firm conclusions can be drawn about the association between the scope of practice and access to care, nor between their influence on the quality of care.

6. CONCLUSION

The scope of practice required of nurses providing healthcare to people experiencing homelessness is broad. To improve access to care, findings suggest that a broad range of skills are required, with a focus on physical and mental health assessment and disease identification. Personal attributes and the approach to care are particularly important to engender trust and trauma‐informed therapeutic relationship. As one of the largest healthcare disciplines, nurses are well placed to facilitate access to healthcare for people experiencing homelessness. The findings of this review will be fundamental to the design of an educational and organizational framework to optimize the scope of practice of nurses providing healthcare to people experiencing homelessness.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors played a substantial role in the conception and design of the review, revising it critically for important intellectual content and giving final approval of the version to be published. All authors have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. LM, JC and MP have additionally made substantial contributions to the acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and LM and JC have been involved in drafting and revising the manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by a research grant from the St Vincent's Health Australia, Inclusive Health Fund. The funder did not play a role in any part of the review process or the decision to submit the article for publication. There was no external funding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REVIEW REGISTRATION

This review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021224447), and can be accessed at www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42021224447.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jan.15387.

Supporting information

File S1

File S2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Julie Williams, Research Services Librarian at the Walter McGrath Library at St Vincent's Hospital Sydney, Australia, helped in developing and refining the search strategy for this systematic review. Dr Oyebola Fasugba, Senior Research Officer with the Nursing Research Institute, St Vincent's Health Network Sydney, St Vincent's Hospital Melbourne and the Australian Catholic University, provided advice on the methodological approach to the review process. Open access publishing facilitated by Queensland University of Technology, as part of the Wiley ‐ Queensland University of Technology agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

McWilliams, L. , Paisi, M. , Middleton, S. , Shawe, J. , Thornton, A. , Larkin, M. , Taylor, J. , & Currie, J. (2022). Scoping review: Scope of practice of nurse‐led services and access to care for people experiencing homelessness. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78(11), 3587–3606. 10.1111/jan.15387

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Australian Bureau of Statistics . (2018). Census of Population and Housing: Estimating Homelessness. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/housing/census‐population‐and‐housing‐estimating‐homelessness/2016

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . (2018). _Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia, 2018. Retrieved from Canberra: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/domestic‐violence/family‐domestic‐sexual‐violence‐in‐australia‐2018

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . (2020). Homelessness and homelessness services. Retrieved from Canberra: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias‐welfare/homelessness‐and‐homelessness‐services

- Ayala, A. , Tegtmeyer, K. , Atassi, G. , & Powell, E. (2021). The effect of homelessness on patient wait times in the emergency department. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 60, 661–668. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggett, T. P. , O'Connell, J. J. , Singer, D. E. , & Rigotti, N. A. (2010). The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: A national study. American Journal of Public Health, 100(7), 1326–1333. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J. , Travers, J. L. , Buschman, P. , & Merrill, J. A. (2018). An efficient nurse practitioner–led community‐based service model for delivering coordinated care to persons with serious mental illness at risk for homelessness. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 24(2), 101–108. 10.1177/1078390317704044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J. , Nyamathi, A. , Christiani, A. , Morisky, D. , & Leake, B. (2005). Predictors of screening results for depressive symptoms among homeless adults in Los Angeles with latent tuberculosis. Research in Nursing & Health, 28(3), 220–229. 10.1002/nur.20074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxall, H. , Morgan, A. , & Brown, R. (2020). The prevalence of domestic violence among women during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Australasian Policing, 12(3), 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Brush, B. L. , & Powers, E. M. (2001). Health and service utilization patterns among homeless men in transition: Exploring the need for on‐site, shelter‐based nursing care. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 15(2), 143‐154; discussion 155‐159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, K. , Morley, C. , Warren, S. , Harris, B. , Vitis, L. , Ball, M. , Clarke, J. , & Ryan, V. (2020). Impact of COVID on domestic and family violence services and clients: QUT Centre for justice research report.

- Chamberlain, C. , & MacKenzie, D. (2008). Counting the homeless 2006. Retrieved from https://apo.org.au/node/4672

- Dahrouge, S. , Muldoon, L. , Ward, N. , Hogg, W. , Russell, G. , & Taylor‐Sussex, R. (2014). Roles of nurse practitioners and family physicians in community health centres. Canadian Family Physician, 60(11), 1020–1027. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico, J. B. , & Nelson, J. (2008). Nursing care management at a shelter‐based clinic: An innovative model of care. Professional Case Management, 13(1), 26–36. 10.1097/01.Pcama.0000306021.64011.02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, A. , & Wood, L. (2018). Homeless health care: Meeting the challenges of providing primary care. The Medical Journal of Australia, 209, 230–234. 10.5694/mja17.01264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorney‐Smith, S. (2007). Piloting the community matron model with alcoholic homeless clients. British Journal of Community Nursing, 12(12), 546–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorney‐Smith, S. (2011). Nurse‐led homeless intermediate care: An economic evaluation. British Journal of Nursing, 20(18), 1193–1197. 10.12968/bjon.2011.20.18.1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, S. , Geddes, J. R. , & Kushel, M. (2014). The health of homeless people in high‐income countries: Descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet (London, England), 384(9953), 1529–1540. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatau, P. , Tyson, K. , Callis, Z. , Seivwright, A. , Box, E. , Rouhani, L. , Ng, S. W. , Lester, N. , & Firth, D. (2018). The state of homelessness in Australia's cities: A health and social cost too high. Retrieved from https://www.csi.edu.au/media/STATE_OF_HOMELESSNESS_REPORT_FINAL.pdf

- Flook, M. , Grohmann, S. , & Stagg, H. R. (2020). Hard to reach: COVID‐19 responses and the complexities of homelessness. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8(12), 1160–1161. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30446-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]