Abstract

With international health challenges, there are opportunities for collaboration between nations on health issues, including developing and sharing resources for teaching and learning. This article outlines collaboration across Scotland and England to develop a core resource for eLearning on health literacy. It describes the development of the resource with case studies of the implementation in Scotland and England, demonstrating the balance between shared development and tailored implementation. The eLearning was developed to increase awareness of NHS workforce and community partners, supplemented by training for NHS librarians and public health specialists to enable them to provide more tailored training on health literacy techniques.

Keywords: eLearning, Great Britain (GB), Health literacy, libraries, hospital, National Health Service (NHS), public health

BACKGROUND

Challenges facing health libraries and societies rarely stop at country borders. One such challenge is health literacy, or the ability to access, assess and use health information. Supporting people to develop and use health literacy skills and techniques is a global challenge (Nutbeam & Kickbusch, 2000).

The health literacy levels cited in the UK are based on work by Rowlands et al. (2015). This seminal study indicates that 43% of adults aged 16–65 struggle to understand and use written health information where the content consists of words. When numbers are added, 61% of adults aged 16–65 struggle to understand and use the health information (Rowlands et al., 2015). In practice, most health information contains both words and numbers, such as the number of tablets to be taken and the number of times a day to take them. At points of shock or anxiety, such as diagnosis, health literacy levels can go down (McKenna et al., 2017). As a result, anyone can struggle with health literacy at points of key interaction with health services.

If members of the public are to be able to have informed discussions about their health, then health and care practitioners need to be aware of health literacy and techniques they can use, so that they can select resources and hold conversations in ways that allow for differing health literacy levels.

The strategic leads for NHS knowledge and library services in Scotland and England respectively are NHS Education for Scotland and Health Education England. Health Education England's role in the education and training of the health and care workforce also includes education for the wider public health workforce. In 2018, staff across the two organisations agreed to collaborate on the development of a health literacy eLearning package that could be used in both nations and implemented through blended learning approaches adapted to needs of the health workforces in Scotland and England. The eLearning was intended as a core tool to spread awareness amongst the NHS workforce and community organisations, to be supplemented by more specific training on techniques for NHS librarians and public health staff to enable them to cascade more tailored training.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE eLEARNING PACKAGE

Collaborating across Scotland and England on eLearning provided opportunities for sharing knowledge and maximising the cost‐effectiveness of developing an eLearning product. The teams agreed that they wanted to build on the five core elements of the action plan for health literacy in Scotland, Making it easier (Scottish Government, 2017). This policy is consistent with good practice shared in England.

The five core elements of Making it easier are techniques to support health literacy. To put these techniques into context, the team produced an opening section to increase awareness of health literacy and the impact of low health literacy before developing short sections on each of the techniques:

Teach back – the person sharing information takes responsibility for ensuring that information is understood, by asking the person with whom they are communicating to share back what they have understood in their own words. The communicator may ask how the person receiving information would talk about what they have just heard. For example, how would they explain the health information to a family member. This establishes what it is that has been understood and whether the communicator needs to explain the information differently.

Chunk and check – information is shared in short sections. The teach back approach is often used alongside chunk and check to find out what has been understood and whether the information needs to be shared differently.

Use of simple language – healthcare conversations are often filled with jargon, so this is an encouragement to use simpler language. Where a medical term needs to be included, this should be explained.

Use of images – images can be helpful to support understanding, but have to be used with care, as images can be understood in different ways.

Routine offer of help – a routine offer of help avoids staff making assumptions about who needs help. With anxiety or the shock of diagnosis, someone who may appear to be highly confident and health literate may be in need of help.

As a collaboration across Scotland and England, the team working on the eLearning brought together health libraries leads in the two nations and public health specialists in England. This multidisciplinary collaboration ensured that the eLearning programme met the needs of the breadth of practitioners across public health as well as being a resource to be shared by health librarians working with colleagues both in healthcare and library staff in other sectors.

The eLearning was funded by the public health team at Health Education England, with inputs on the content from all participants. The team worked both by email and, pre‐pandemic, met in Manchester with the development agency. The aim from the outset was to keep the resource sufficiently succinct that busy health professionals would complete it, so no more than 35 min, and provide a tool that people could come back to for a refresher on techniques. The closing case study was set in a public library, to encourage use of health literacy techniques in community settings. To support application of learning, users of the tool generated a personalised action plan to apply the techniques they had learned and discuss the implications with colleagues (Health Education England, 2020; NHS Education for Scotland, 2020).

Whilst the 35‐min eLearning provides a good insight into techniques, it was designed to be supplemented by training to equip NHS librarians and public health staff to cascade more specific training. In both nations, use of the health literacy eLearning formed part of a blended learning approach.

SCOTLAND CASE STUDY

In Scotland, the eLearning module is hosted on Turas Learn, Scotland's national learning management system, therefore it is available to all health and social care staff (NHS Education for Scotland, 2020). As a content owner, NHS Education for Scotland can view a report of use and any comments left by learners.

Examples of comments left by learners are:

It's an eye opener, very detailed, will recommend it

I wasn't very sure what the course would actually be about, but I feel I have come away with communication skills that will help in other areas not just heath literacy

It is very simple to follow and identify small changes I can make to help others

Lovely practical and helpful resource. The new scroll down format was different. Enjoyed the videos and pictures.

The Knowledge Services Team in NHS Education for Scotland promote webinars on Turas Learn on the same page as the eLearning module. In general, a prerequisite for attending a webinar is the completion of the module. This provides learners with a blended approach to further explore how they can use the learning in practice.

The webinars last for 1 h and are delivered using Microsoft Teams. The aim is to encourage participants to share experiences or ideas of implementing the learning in their practice. At the start of the pandemic these webinars were promoted to support remote consultations. This was popular with over 253 people attending webinars in 2020–2021 and 220 attendees in 2021–2022.

Each webinar begins with a review of the tools and techniques and provides additional information on the impact of poor health literacy and therefore why it is important. The section on using plain English and avoiding jargon prompts discussions on letters and information leaflets sent to patients. Many participants leave the webinar pledging to review the letters they send out to patients.

The health literacy webinars are tailored to the audience and promoted in a variety of ways: as part of annual curriculum for professions, including pharmacists and General Practice Nurses; for team‐based learning, including dieticians; and general multidisciplinary sessions.

The Knowledge Services Team at NHS Education for Scotland ensures that the webinars are interactive, using quizzes, polls and ‘Chat, Hold, Send’ technique to encourage everyone to input their ideas.

The team shared materials with Health Improvement teams and others with responsibility for health literacy in the Scottish Health Boards to spread the learning more widely. The NHS Scotland librarians received training to deliver health literacy skills in the past and many provide in person sessions locally in their Health Boards.

Social care staff in Scotland are encouraged to complete Open Badges hosted on the Scottish Social Services Council website. The Open Badges are a digital record of achievements and skills. Learners must submit a reflection or result of an activity following the completion of the learning. The team in NHS Education for Scotland developed two badges to promote health literacy: level 1 covers awareness of the ‘Teachback’ tool; and level 2 is awarded on completion of the eLearning module. Through previous in‐person workshops, the team had already established interest in the use of health literacy tools and techniques to support communication in care settings and the Open Badges made learning available to a wider audience. Seventy badges were awarded in 2020–2021 and 32 in 2021–2022.

In Scotland, library and knowledge services use the ‘Knowledge into Action’ cycle as a framework promote their services and health literacy is a key component of the ‘Share’ activity (Davies et al., 2017). This integrates health literacy into ongoing activity. The comparison between activity in Scotland and England is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Number of learners using and completing the health literacy eLearning programme in Scotland and England

ENGLAND CASE STUDY

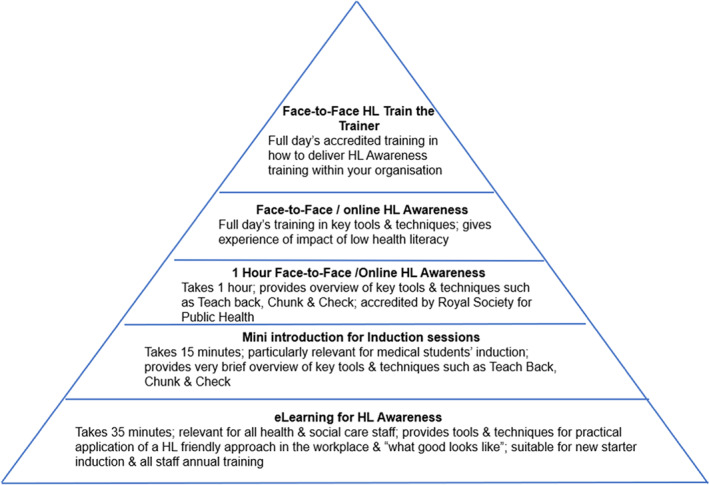

At Health Education England, the public health team and the national NHS knowledge and libraries services team worked together to develop a set of interventions to cascade health literacy training, focussing respectively on the public health workforce and on NHS staff and the public. The health literacy eLearning was integrated into the wider range of training materials, from ‘train‐the‐trainer’ to 1‐h and 15‐min sessions. The 1‐h session was accredited by the Royal Society for Public Health (See Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Health literacy training tools for spread and adoption in England, Ruth Carlyle and Sally James, September 2019 [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The activity with NHS libraries was in two parts: cascading health literacy awareness and skills through NHS library staff to the NHS workforce; and working through partnerships with public libraries and community information providers to build the skills and confidence of members of the public. This formed part of the wider strategic framework for developing and raising the profile of NHS knowledge and library services (Lacey Bryant et al., 2018) and increasing the role of NHS libraries in patient and public information (Carlyle et al., 2022). NHS librarians trained the NHS workforce in their organisations, in some instances developing health literacy champions in clinical teams (Naughton et al., 2021). In 2020–2021, nine trainers were trained to cascade training, with 18 trainers trained in 2021–2022. Over 800 people were trained by these trainers during 2021–2022. With the COVID‐19 pandemic, content from trustworthy sources was collated alongside health literacy training to meet immediate health information needs alongside developing health literacy skills for the longer term (Carlyle & Robertson, 2021). This collated content was promoted to public libraries alongside health literacy resources.

Health literacy for members of the public was developed by the national NHS knowledge and libraries services team through a National Health and Digital Literacy Partnership with the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals, Libraries Connected (the strategic body for public libraries) and Arts Council England (Carlyle, 2022). This included the cascade of health literacy training to prison librarians, as residents in prisons have particularly acute health information and health literacy needs (Robertson & Naughton, 2022). Alongside the training, the partnership is funding a series of local pilots to test mechanisms to increase the health literacy of the public.

NHS knowledge and library services providing training to the NHS workforce and to colleagues in community information settings share learning through an online community of practice.

For the public health workforce, largely based in local authorities, a model for scale and spread of Health Literacy Awareness Training and the Health Literate Organisation Programme was developed across the public health system, with bespoke sessions to raise awareness and understanding, and build knowledge and competency. Four sessions on Health Literacy Awareness were delivered, with 333 public health practitioners in attendance, followed by five Health Literate Organisation programme sessions with 182 practitioners in attendance. The programme guided people through the component parts of being a health literate organisation, with attendees ranging from public health practitioners in local authorities, to prison healthcare staff, hospital trusts and care home staff.

Networking across the wider health and care system is facilitated through a dedicated growing on‐line community of practice (knowledge hub) to discuss and share resources, reflections and learning (over 100 members to date). The aim is to put health literacy into the heart of both NHS and non‐NHS organisations – people, processes, policies – with the emphasis on including service users in how they are communicated with and to. Building the workforce capability and competency in knowing what health literacy is, why it is important and what they can do to improve it is vital for addressing health inequalities; from creating written material that is understandable and helps people act in support of their health, to communicating orally so that people can understand and act on the information shared.

LEARNING AND CONCLUSIONS

When developing the module, the team spent a lot of time planning and refining the concepts, working closely with the instructional designers. The positive feedback from learners demonstrates that this time was well spent. It was useful to build into the contract that individual assets would be provided as separate items for reuse in other settings, these were an animation, a video and images for promotional materials.

The discussions with the instructional designers led to the successful integration of interactions to actively engage learners. It is important to help learners relate any learning to their practice.

At the end of each section of the module, learners are encouraged to complete an action log. This can be downloaded for future reference. To make it quick to complete, some actions are suggested but the learner can add their own.

The final activity in the module is a video filmed in a public library. The action is paused at various points and asks the learner to input a decision on a health literacy technique, again helping to reinforce the learning.

At the start, learners are asked to record their confidence related to health literacy and this is revisited at the end to note improvement.

Setting the video in a public library served two purposes: first, it is neutral of any health or care setting; and second, it has provided Health Education England and NHS Education for Scotland with a video to use with public and school librarians to understand how they can use the tools in their role to support communication. This has been used successfully as part of a course delivered in Scotland.

In both Scotland and England, the eLearning was placed on recognised platforms. This meant that it could be integrated into learning records. Providing eLearning in isolation, however, would not have ensured its use and would not have met the learning needs of local public health and library staff who wanted to cascade health literacy tools and techniques within their organisations or more widely. It was therefore essential to ensure that the health literacy eLearning was integrated into wider learning and development offers.

As the next stage, NHS Education for Scotland and Health Education England will review feedback to date and consult on changes needed to update the health literacy eLearning.

Carlyle, R. , Thain, A. , & James, S. (2022). Development and spread of health literacy eLearning: A partnership across Scotland and England. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 39(3), 299–303. 10.1111/hir.12450

REFERENCES

- Carlyle, R. (2022). Health and digital literacy: Addressing inequalities. Information Professional, April‐May, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Carlyle, R. , Goswami, L. , & Robertson, S. (2022). Increasing participation by National Health Service knowledge and library services staff in patient and public information: The role of knowledge for healthcare 2014‐2019. Health Libraries and Information Journal, 39(1), 36–45. 10.1111/hir.12388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlyle, R. , & Robertson, S. (2021). Balancing long‐term health literacy skills development with immediate action to facilitate use of reliable health information on COVID‐19 in England. Journal of European Association of Health Information and Libraries, 17(4), 12–16. 10.32384/jeahil17493 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S. , Herbert, P. , Wales, A. , Ritchie, K. , Wilson, S. , Dobie, L. , & Thain, A. (2017). Knowledge into action – supporting the implementation of evidence into practice in Scotland. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 34(1), 74–85. 10.1111/hir.12159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Education England . (2020). Health literacy eLearning. https://www.e-lfh.org.uk/programmes/healthliteracy/

- Lacey Bryant, S. , Bingham, H. , Carlyle, R. , Day, A. , Ferguson, L. , & Stewart, D. (2018). Forward view: Advancing health library and knowledge services in England. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 35(1), 70–77. 10.1111/hir.12206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, V. B. , Sixsmith, J. , & Barry, M. M. (2017). The relevance of context in understanding health literacy skills: Findings from a qualitative study. Health Expectations, 20(5), 1049–1060. 10.1111/hex.12547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton, J. , Booth, K. , Elliott, P. , Evans, M. , Simoes, M. , & Wilson, S. (2021). Health literacy: The role of NHS library and knowledge services. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 38(2), 150–154. 10.1111/hir.12371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS Education for Scotland . (2020). Health literacy eLearning. https://learn.nes.nhs.scot/26672/health-literacy

- Nutbeam, D. , & Kickbusch, I. (2000). Advancing health literacy: A global challenge for the 21st century. Health Promotion International, 15(3), 183–184. 10.1093/heapro/15.3.183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, S. , & Naughton, J. (2022). Your health: How health librarians improve your health literacy skills. Inside Time, May, 36. https://insidetime.org/your-health-how-librarians-improve-your-health-literacy-skills/ [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands, G. , Protheroe, J. , Winkley, J. , Richardson, M. , Seed, P. T. , & Rudd, R. (2015). A mismatch between population health literacy and the complexity of health information: An observational study. British Journal of General Practice, 65, 296–297. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X685285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Government . (2017). Making it easier: A national health literacy plan for Scotland, 2017‐2025. https://www.gov.scot/publications/making‐easier‐health‐literacy‐action‐plan‐scotland‐2017‐2025/