Abstract

Background

Preliminary in vitro and in vivo studies have supported the efficacy of the peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐γ (PPARγ) modulator N‐acetyl‐GED‐0507‐34‐LEVO (NAC‐GED) for the treatment of acne‐inducing sebocyte differentiation, improving sebum composition and controlling the inflammatory process.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of NAC‐GED (5% and 2%) in patients with moderate‐to‐severe facial acne vulgaris.

Methods

This double‐blind phase II randomized controlled clinical trial was conducted at 36 sites in Germany, Italy and Poland. Patients aged 12–30 years with facial acne, an Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score of 3–4, and an inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion count of 20–100 were randomized to topical application of the study drug (2% or 5%) or placebo (vehicle), once daily for 12 weeks. The co‐primary efficacy endpoints were percentage change from baseline in total lesion count (TLC) and IGA success at week 12; the safety endpoints were adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs. This study was registered with EudraCT (2018‐003307‐19).

Results

Between Q1 in 2019 and Q1 in 2020 450 patients [n = 418 (92·9%) IGA 3; n = 32 (7·1%) IGA 4] were randomly assigned to NAC‐GED 5% (n = 150), NAC‐GED 2% (n = 150) or vehicle (n = 150). The percentage change in TLC reduction was statistically significantly higher in both the NAC‐GED 5% [–57·1%, 95% confidence interval (CI) –60·8 to –53·4; P < 0·001] and NAC‐GED 2% (–44·7%, 95% CI –49·1 to –40·1; P < 0·001) groups compared with vehicle (–33·9%, 95% CI –37·6 to –30·2). A higher proportion of patients treated with NAC‐GED 5% experienced IGA success (45%, 95% CI 38–53) vs. the vehicle group (24%, 95% CI 18–31; P < 0·001). The IGA success rate was 33% in the NAC‐GED 2% group (P = not significant vs. vehicle). The percentage of patients who had one or more AEs was 19%, 16% and 19% in the NAC‐GED 5%, NAC‐GED 2% and vehicle groups, respectively.

Conclusions

The topical application of NAC‐GED 5% reduced TLC, increased the IGA success rate and was safe for use in patients with acne vulgaris. Thus, NAC‐GED, a new PPARγ modulator, showed an effective clinical response.

What is already known about this topic?

Acne vulgaris, one of the most common dermatological diseases, affects more than 85% of adolescents.

There is a medical need for innovative and safe treatment of acne vulgaris.

The peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐γ (PPARγ) is involved in lipid metabolism and specifically in cell differentiation, sebum production and the inflammatory reaction.

What does this study add?

N‐acetyl‐GED‐0507‐34‐LEVO (NAC‐GED 5%), a PPARγ modulator, significantly improves acne manifestations in patients with moderate‐to‐severe acne and is safe and well tolerated.

The results suggest that the PPARγ receptor is a novel therapeutic target for acne.

The results provide a basis for a large phase III trial to assess the effectiveness and safety profile of NAC‐GED in combating a disease that afflicts 80–90% of adolescents.

The topical application of NAC‐GED 5% reduced TLC, increased the IGA success rate and was safe for patients with acne vulgaris #10;‐ NAC‐GED, a new PPAR gamma; modulator, showed an effective clinical response.

Linked Comment: C. Dessinioti. Br J Dermatol 2022; 187:455–456.

Plain language summary available online

Acne vulgaris, the most frequent disorder of the pilosebaceous unit, 1 , 2 affects more than 85% of the adolescent and young adult population, and 650 million people worldwide. 3 The disease produces a substantial psychological and social burden due to frequent relapses and persistence in adulthood. 4 , 5

Mild‐to‐moderate acne is treated with topical agents, including antibiotics, benzoyl peroxide and retinoids. In unresponsive patients or more severe forms of acne oral agents are added, such as antibiotics or isotretinoin. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 These agents act on specific parts of the acne pathogenesis pathway. However, by combining them, different pathways can be targeted at once, increasing the probability and severity of side‐effects. 8 , 9

Within the last 10 years, limited progress has been made in identifying novel therapeutic acne agents. Only the steroidal antiandrogen clascoterone and the retinoid trifarotene have recently been approved for topical treatment. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 Thus, there is an unmet clinical need for novel, effective substances with an enhanced mechanism of action that target acne pathogenesis pathways simultaneously with reduced side‐effects.

Factors involved in acne development include alterations in the hormonal microenvironment, follicular hyperkeratinization, inflammation, dysfunction of the immune response, interactions with the host microbiome and sebaceous gland activity, as well as sebum composition. 6 Alterations in sebum composition affect acne manifestation more than increased sebum secretion. 14 Both innate and adaptive immunity are involved, particularly T helper 17 cells. 6

Recent research has focused on the hormonal control of sebum production and composition. 15 , 16 During puberty, hormones such as androgens, insulin and insulin‐like growth factor increase sebaceous gland volume. They activate the transcription factor sterol response element‐binding protein 1 (SREBP1) through the phosphatidylinositide 3‐kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway, inducing sebogenesis. 15 , 16

Sebum production is also controlled by the peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐γ (PPARγ). PPARγ belongs to a family of nuclear receptors expressed in various cell types that function as transcription factors to regulate cellular differentiation, development and metabolism. 6 , 11 , 16 In sebocytes, PPARγ expression strictly correlates with cell differentiation. 17 It was recently discovered that undifferentiated sebocytes, when compared with differentiated sebocytes, are more susceptible to insulin levels comparable to normal serum insulin. Insulin stimulates the activation of desaturase enzymes, with the production of acne‐compatible sebum and the generation of inflammatory mediators. 18 In an in vitro model, treatment with the novel selective PPARγ modulator (S)‐3‐(4‐acetamidophenyl)‐2‐methoxypropanoic acid [N‐acetyl‐GED0507‐levo (NAC‐GED)] 19 , 20 promoted sebocyte differentiation, reduced insulin‐induced lipogenesis and inflammation, and improved sebum composition. Simultaneously, the ratio of sapienic acid/palmitic acid and lipoperoxide production decreased, as did the production of inflammatory mediators. 21 , 22

In this phase IIb double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study, we evaluated the tolerability and efficacy of topical NAC‐GED 2% and 5% in patients with moderate‐to‐severe acne vulgaris.

Patients and methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a double‐blind phase II randomized controlled clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of NAC‐GED (2% and 5%) in patients with moderate‐to‐severe acne vulgaris vs. placebo (vehicle). The study was conducted in Germany, Italy and Poland, at 16 university hospitals and 20 private dermatological clinics (EudraCT: 2018‐ 003307‐19).

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees before trial initiation. PPM Services, Switzerland, sponsored the trial and provided the study medication but did not influence the authorship of this manuscript. The study complied with good clinical practice (GCP), in agreement with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in keeping with local regulations. The personal information of the study participants was documented in the personal file or electronically saved, and data protection was ensured according to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (2016/679). Trial activities were monitored according to the International Conference on Harmonisation’s GCP guidelines for protocol adherence, quality of data, drug accountability, protection of patients’ safety and rights, compliance with regulatory requirements and adequacy of the facilities. All patients or legal guardians provided written informed consent to participate.

Patients aged 12–30 years with facial acne vulgaris, an Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score of 3–4, and an inflammatory (papules and pustules) and noninflammatory (closed and open comedones) lesion count of 20–100 each and with ≤ 1 nodule were included in this study. Patients with the following conditions were excluded: spontaneously improving or rapidly deteriorating acne within the last 3 months; a history of acne unresponsive to topical and/or oral treatments; acne forms other than facial acne vulgaris; other active skin or systemic diseases; and pregnant or nursing women. Patients on systemic treatments or receiving phototherapy, and bearded participants were excluded (a full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in Appendix S2; see Supporting Information).

The dose selection rationale was based on results from a previous phase IIa proof‐of‐concept clinical study (EudraCT: 2017‐003796‐58) and a previous phase Ib study (EudraCT: 2017‐003796‐58).

Randomization and masking

Eligible patients were randomly assigned (1 : 1 : 1) to receive one of three treatments (vehicle gel; NAC‐GED 5% gel; or NAC‐GED 2% gel) for once‐daily face application for 12 weeks, according to the randomization list stratified by site (Figure 1). The tube weight, gel appearance, texture and odour of all three formulations were identical.

Figure 1.

Trial profile. GCP, good clinical practice; IGA, Investigator Global Assessment; NAC‐GED, N‐acetyl‐GED‐0507‐34‐LEVO; PP, per‐protocol.

Each site received whole blocks of individual treatment kits. Randomization numbers and kit numbers were generated and assigned to the patients on study day 1 using a central Interactive Web Response System. Patients, sponsor site personnel and study personnel were blinded to the treatment.

Procedures

On day 1, patients applied the first dose to the whole of their face, under investigator supervision; thereafter, doses were applied once daily (evening) at home. Follow‐up site visits were conducted at weeks 3, 6, 12 and 14, and telephone visits at week 9, during which compliance and history of adverse events (AEs) were examined. Any other acne treatment was excluded. The patients were instructed to clean their faces with a gentle, noncomedogenic cleanser and were advised not to overuse skin‐covering cosmetics and sunscreen. Acne severity was assessed at every visit using the 4‐point IGA score according to the Food and Drug Administration’s Acne Guidance 2006/2014 (0 = clear, 1 = almost clear, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = severe) based on live assessments by the clinical investigator. Moreover, for each patient, the principal investigator performed additional photographic evaluations. Two blinded dermatologists, internationally recognized as acne experts, verified the IGA scoring using photographic evidence, guaranteeing consistency across trial sites and providing a quality‐control measure. Inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions on the face were counted and recorded at each site visit. Total lesion count (TLC) was calculated as the sum of inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions on the face.

Outcomes

The co‐primary endpoints, assessed in the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) population, were the percentage change from baseline in TLC and the proportion of patients with an IGA score of ‘clear’ (score 0) or ‘almost clear’ (score 1) with at least a two‐score reduction, from baseline at week 12. The percentage changes in inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion count from baseline were secondary endpoints. The safety endpoint was the occurrence of AEs and severe AEs (SAEs) in each group. Topical symptoms and signs were closely monitored.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was computed based on the IGA success rate to reach a power of 90%, fixing the type I error α at 0·05. Assuming a NAC‐GED 5% treatment group IGA success rate of 38% and a vehicle group IGA success rate of 20% [odds ratio (OR) 0·408], the Fisher’s exact test for two proportions required a sample size of 142 participants in each group (a total sample size of 426). A total of 450 patients were enrolled in the study based on an approximation of 5–6% patient attrition. The ITT set included all randomized subjects, the per‐protocol (PP) set all patients who completed the study without major protocol deviations and the safety set all patients who received at least one treatment dose.

Continuous variables were described as mean, range and median, and categorical variables as a percentage. Hypothesis testing on the primary outcomes (for NAC‐GED 5%) was conducted consecutively (i.e. the change in IGA scores was only assessed if the change in the TLC achieved a significant difference between the vehicle and treatment arm). Analysis of efficacy was conducted on the ITT (primary) and PP sets. ancova and logistic regression were used to compare the vehicle and treatment groups. The baseline observation carried forward imputation methodology was used to impute missing values for the TLC and IGA. Following these imputation rules, patients with missing values for TLC and/or IGA at week 12 were considered as if the treatment was not effective. Additional statistical analyses controlled for possible effects of body mass index (BMI) and participating centres, and further sensitivity analysis was conducted to increase results robustness (Appendix S3; see Supporting Information). All statistical processing was performed using SAS version 9·4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

A total of 450 patients [IGA 3: n = 418 (93%); IGA 4: n = 32 (7%)], 186 from university hospitals and 264 from private dermatological clinics, were enrolled from March 2019 to May 2020 and randomly assigned to the NAC‐GED 5% (n = 150), NAC‐GED 2% (n = 150) and vehicle groups (n = 150). All patients received at least one study treatment and were therefore included in the ITT and safety sets. The clinical characteristics of the three groups are provided in Table 1. Mean (SD) patient age in the ITT set was 18·5 (4·0) years, with 58·4% aged ≤18 years; 61·6% were female. The PP set at baseline showed similar demographics. Most patients completed the study [n = 400; 88·9% (Table S1; see Supporting Information)].

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at baseline in the intention‐to‐treat set

| Characteristic | NAC‐GED 5% (n = 150) | NAC‐GED 2% (n = 150) | Vehicle (n = 150) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (range) | 18·5 (12–28) | 18·8 (12–30) | 18·1 (12–28) |

| ≤ 18 | 87 (58·0) | 85 (56·7) | 91 (60·7) |

| > 18 | 63 (42·0) | 65 (43·3) | 59 (39·3) |

| Male | 62 (41·3) | 54 (36·0) | 57 (38·0) |

| Mean (SD) BMI (kg m–2) | 22·56 (4·62) | 21·66 (3·32) | 21·44 (3·13) |

| Inflammatory lesion count | |||

| Mean (range) | 34·2 (20–99) | 34·7 (20–95) | 33 (20–108) |

| Median | 29 | 29·5 | 28 |

| Noninflammatory lesion count | |||

| Mean (range) | 46·1 (20–100) | 45·8 (20–100) | 48·2 (20–108) |

| Median | 41·5 | 41 | 41·5 |

| TLC | |||

| Mean (range) | 80·3 (40–179) | 80·5 (40–165) | 81·2 (40–179) |

| Median | 77·5 | 75 | 74 |

| Mean (range) IGA score | 3·1 (3–4) | 3·1 (3–4) | 3·1 (3–4) |

| IGA 3 | 140 (93·3) | 141 (94·0) | 137 (91·3) |

| IGA 4 | 10 (6·7) | 9 (6·0) | 13 (8·7) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise stated. BMI, body mass index; IGA, Investigator Global Assessment; NAC‐GED, N‐acetyl‐GED‐0507‐34‐LEVO; TLC, total lesion count.

After 12 weeks of treatment, there was a significant percentage change in TLC from baseline in both the NAC‐GED 5% [–57·1%, 95% confidence interval (CI) –60·8 to –53·4] and NAC‐GED 2% (–44·7%, 95% CI –49·1 to –40·1) groups compared with the vehicle (–33·9%, 95% CI –37·6 to –30·2) in the ITT (P < 0·001 and P = 0·001, respectively) and PP sets (P < 0·001 for both sets; Table 2). In the ITT population, the proportions of patients with IGA success were 45%, 33% and 24% in the NAC‐GED 5%, NAC‐GED 2% and vehicle groups, respectively. Statistically significant reductions were reached only for the 5% group (OR 2·63, 95% CI 1·60–4·30; P < 0·001). The PP set had similar results, with a statistically significant effect of NAC‐GED 2% vs. vehicle [OR 1·91, 95% CI 1·07–3·39; P = 0·001 (Table 2)].

Table 2.

Primary outcomes after 12 weeks of treatment

| ITT set | PP set | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | NAC‐GED 5% (n = 150) | NAC‐GED 2% (n = 150) | Vehicle (n = 150) | NAC‐GED 5% (n = 129) | NAC‐GED 2% (n = 137) | Vehicle (n = 135) |

| Percentage TLC change (95% CI) | –57.1a,b (–60·8 to –53·4) | –44·7c (–49·1 to –40·1) | –33·9 (–37·6 to –30·2) | –61.6a,b (–65·4 to –58·1) | –43.7c (–48·4 to –39·0) | –31·9 (–35·3 to –28·2) |

| Percentage IGA successd (95% CI) | 45a,b (38–53) | 33 (26–41) | 24 (18–31) | 51a,b (43–60) | 29e (22–37) | 18 (12–25) |

| OR (95% CI) | 2·63 (1·60–4·30) | 1·58 (0·95–2·63) | 4·85 (2·77–8·48) | 1·91 (1·07–3·39) | ||

CI, confidence interval; IGA, Investigator Global Assessment; ITT, intention to treat; NAC‐GED, N‐acetyl‐GED‐0507‐34‐LEVO; OR, odds ratio; PP, per protocol; TLC, total lesion count. aCompared with vehicle; bcompared with NAC‐GED 2%; c P = 0·001; dcleared or almost cleared with at least a two‐score reduction from baseline at week 12; e P < 0·05.

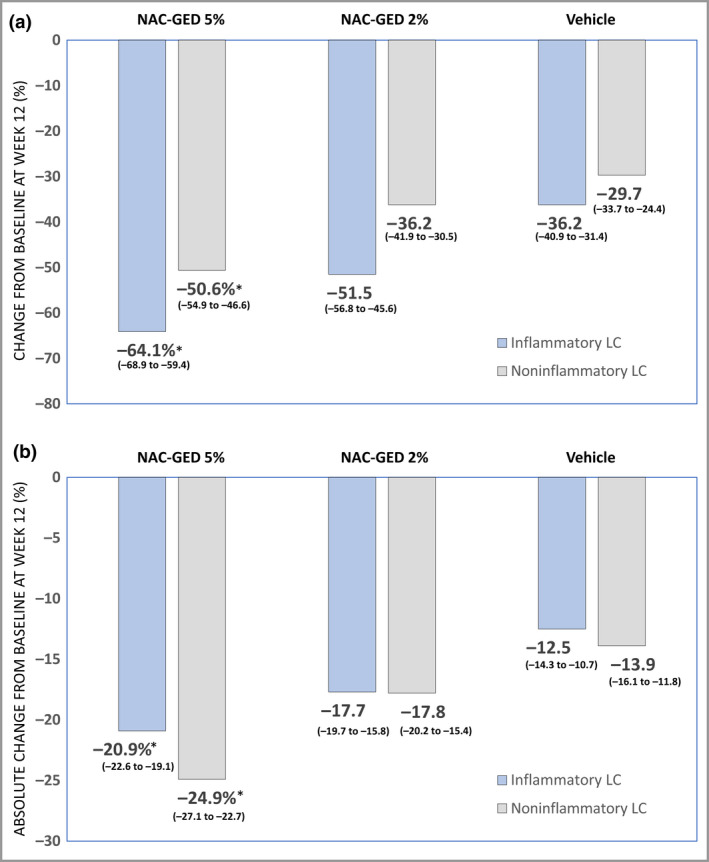

Compared with the vehicle group in the ITT set (Figure 2a), NAC‐GED 5% had statistically significant reductions in the percentage change from baseline in noninflammatory lesions [– 50·6% (95% CI –54·9 to –46·6) vs. –29·7 (95% CI –33·7 to –25·4); P < 0·001] and inflammatory lesions [–64·1% (95% CI –68·9 to –59·4) vs. –36·2% (95% CI –40·9 to –31·4); P < 0·001]. A similar statistical difference was observed for the absolute change from baseline of inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion count (Figure 2b). Moreover, we observed a statistically significant reduction in absolute TLC from baseline in the NAC‐GED 5% (–45·7, 95% CI –49·1 to –42·3) and NAC‐GED 2% (–35·6, 95% CI –39·3 to –32·0) compared with vehicle [–26·6, 95% CI –30·2 to –22·9 (both P < 0·001, respectively)] in the ITT set. Similar results were observed in the PP set (Table S2; see Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Changes in lesion count after 12 weeks of treatment (intention‐to‐treat set). Data represent the (a) percentage change and (b) absolute change in inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts (LCs) following treatment with N‐acetyl‐GED‐0507‐34‐LEVO (NAC‐GED) 5%, NAC‐GED 2% or vehicle. Data are presented as mean and 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was determined compared with vehicle using ancova (*P < 0·001). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

A stratified analysis showed that patients aged > 18 years had a higher reduction in percentage change in the TLC in both the NAC‐GED groups than the vehicle group. For detailed results see Table S3 (see Supporting Information). The results of the absolute change of TLC, stratified by sex and by an IGA score of 3 and 4 at baseline, are provided in Tables S4 and S5 (see Supporting Information).

Finally, further statistical analyses controlling for BMI and study centre effects are explained in Appendix S3.

The safety profile of the three treatment groups was similar both in terms of frequency and severity of AEs (Table S6; see Supporting Information). The percentage of patients with more than one AE was 19% in the NAC‐GED 5% and vehicle groups and 16% in the NAC‐GED 2% group. The most common AE was a cold, followed by headache, sore throat and herpes simplex labialis. In total, five SAEs were reported in four patients, unlikely related to treatment (one in the NAC‐GED 2% group and four in the vehicle group). Moreover, descriptive statistics on local tolerability suggested a similar occurrence of topical signs and symptoms across groups (Table 3). The overall application site irritation results showed that NAC‐GED was as well tolerated as placebo (Table S7; see Supporting Information).

Table 3.

Local tolerability of the therapy

| NAC‐GED 5% (n = 150) | NAC‐GED 2% (n = 150) | Vehicle (n = 150) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erythema | |||

| Baseline | |||

| 0 | 134 (89·3) | 130 (86·7) | 128 (85·3) |

| 1 | 13 (8·7) | 20 (13·3) | 13 (8·7) |

| 2 | 3 (2·0) | – | 9 (6·0) |

| 3 | – | – | – |

| Week 12 | |||

| 0 | 128 (85·3) | 128 (85·3) | 123 (82·0) |

| 1 | 9 (6·0) | 7 (4·7) | 9 (6·0) |

| 2 | 1 (0·7) | 1 (0·7) | – |

| 3 | – | – | – |

| Exfoliation | |||

| Baseline | |||

| 0 | 145 (96·7) | 145 (96·7) | 142 (94·7) |

| 1 | 5 (3·3) | 5 (3·3) | 7 (4·7) |

| 2 | – | – | 1 (0·7) |

| 3 | – | – | – |

| Week 12 | |||

| 0 | 125 (83·3) | 129 (86·0) | 123 (82·0) |

| 1 | 13 (8·7) | 6 (4·0) | 9 (6·0) |

| 2 | – | 1 (0·7) | – |

| 3 | – | – | – |

| Dryness | |||

| Baseline | |||

| 0 | 139 (92·7) | 143 (95·3) | 137 (91·3) |

| 1 | 11 (7·3) | 7 (4·7) | 13 (8·7) |

| 2 | – | – | – |

| 3 | – | – | – |

| Week 12 | |||

| 0 | 122 (81·3) | 122 (81·3) | 119 (79·3) |

| 1 | 14 (9·3) | 13 (8·7) | 13 (8·7) |

| 2 | 2 (1·3) | 1 (0·7) | – |

| 3 | – | – | – |

| Stinging | |||

| Baseline | |||

| 0 | 149 (99·3) | 144 (96·0) | 142 (94·7) |

| 1 | 1 (0·7) | 6 (4·0) | 7 (4·7) |

| 2 | – | – | 1 (0·7) |

| 3 | – | – | – |

| Week 12 | |||

| 0 | 135 (90·0) | 132 (88·0) | 126 (84·0) |

| 1 | 3 (2·0) | 4 (2·7) | 6 (4·0) |

| 2 | – | – | – |

| 3 | – | – | – |

| Burning | |||

| Baseline | |||

| 0 | 149 (99·3) | 144 (96·0) | 144 (96·0) |

| 1 | 1 (0·7) | 6 (4·0) | 6 (4·0) |

| 2 | – | – | – |

| 3 | – | – | – |

| Week 12 | |||

| 0 | 137 (91·3) | 130 (86·7) | 130 (86·7) |

| 1 | 1 (0·7) | 6 (4·0) | 2 (1·3) |

| 2 | – | – | – |

| 3 | – | – | – |

| Itching | |||

| Baseline | |||

| 0 | 136 (90·7) | 136 (90·7) | 134 (89·3) |

| 1 | 14 (9·3) | 11 (7·3) | 15 (10·0) |

| 2 | – | 3 (2·0) | 1 (0·7) |

| 3 | – | – | – |

| Week 12 | |||

| 0 | 132 (88·0) | 129 (86·0) | 126 (84·0) |

| 1 | 6 (4·0) | 6 (4·0) | 5 (3·3) |

| 2 | – | 1 (0·7) | 1 (0·7) |

| 3 | – | – | – |

At baseline, there were 150 patients in each group. At week 12, there were 138 patients in the NAC‐GED 5% group, 136 in the NAC‐GED 2% group 132 in the vehicle group. Tolerability score: 0 = severe, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe. NAC‐GED, N‐acetyl‐GED‐0507‐34‐LEVO.

Discussion

In this randomized double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial, topical application of NAC‐GED 5% for 12 weeks reduced the TLC, improved the IGA score and was well‐tolerated in patients with facial acne vulgaris. Neither the age nor the sex of patients substantially affected response to treatment. There was a dose‐dependent effect, and NAC‐GED 5% was more effective than NAC‐GED 2%. Only the 5% gel reached both co‐primary endpoints.

NAC‐GED is a novel PPARγ modulator able to up‐ or downmodulate some of the target genes. 23 Treatment of keratinocytes and sebocytes with NAC‐GED in vitro significantly inhibited the inflammatory process and altered the expression of differentiation markers induced by different stimuli, including Toll‐like receptor activators. 21 , 22 Moreover, NAC‐GED produced differentiation of SZ95 sebocytes, modifying their sensitivity to insulin stimulation and restoring the production of ‘normal’ sebum. 19 , 23

Overall, both NAC‐GED doses were well tolerated. AEs and SAEs did not differ significantly between the vehicle and NAC‐GED groups.

This study has some limitations. The trial was limited to 12 weeks, which may not be sufficient to detect significant acne improvement, and relapses after discontinuation were not monitored. Therefore, longer‐term data on safety and efficacy are needed. In addition, we were unable to account for factors that may contribute to acne development and severity, such as a patient’s dietary habits and glycaemic load, and acne involvement in other areas. However, we considered that patients did not change their habits during the 3‐month trial and that the randomization reduced the relevance of dietary habits. Moreover, BMI did not appear to have confounding effects on either co‐primary endpoint. Patients with a known history of acne unresponsiveness to topical and/or oral treatment were excluded, requiring longer‐term data on the efficacy and safety of NAC‐GED for this subgroup. Patient‐reported outcome measures, as suggested by the ACORN group, 7 , 24 were not used. Instead, data on patient‐evaluated tolerability of the applied treatments (overall application site irritation) were collected instead, reflecting overall patient satisfaction. Finally, this study included patients with moderate (93%) and severe (7%) acne vulgaris who are usually eligible for topical treatment, corresponding to the patient population required by regulatory authorities for the approval of topical acne medication.

We found that both NAC‐GED 5% and NAC‐GED 2% are safe, and that NAC‐GED 5% is effective in treating patients with moderate‐to‐severe facial acne vulgaris, confirming that PPARγ is a novel therapeutic target for acne. Both concentrations reduce TLC and exhibit IGA success. However, only NAC‐GED 5% gel achieved both the co‐primary efficacy endpoints, demonstrating that NAC‐GED 5% gel is the first in a class of novel PPARγ modulators that proved to be successful for the treatment of acne vulgaris. The results obtained will guide future phase III clinical trials.

Author contributions

Mauro Michele Picardo: Conceptualization (equal); investigation (equal); writing – original draft (equal). Carla Cardinali: Investigation (equal). Michelangelo La Placa: Investigation (equal). Anita Lewartowska‐Biatek: Investigation (equal). Giuseppi Micali: Investigation (equal). Roberta Montisci: Project administration (equal). Luca Morbelli: Data curation (supporting). Andrea Nova: Data curation (lead); validation (lead). Aurora Parodi: Investigation (equal). Adam Reich: Investigation (equal). Michael Sebastian: Investigation (equal). Katarzyna Turek‐Urasinska: Investigation (equal). Oliver Weirich: Investigation (equal). Jacek Zdybski: Investigation (equal). Viviana Lora: Investigation (equal). Christos C. Zouboulis: Conceptualization (equal); investigation (equal); writing – original draft (equal).

Funding sources

This work was supported by PPM Services SA, Swiss affiliate of NograPharma Ltd, Dublin, Ireland.

Conflicts of interest

M.P. was the designated scientific expert for the study; C.C.Z. was the designated clinical expert. The laboratories managed by M.P. received a research grant and C.C.Z. received fees for consultation from PPM Services SA. L.M., R.M. and A.N. are employees of the clinical research organizations (funded by PPM Services SA) in charge of the management, monitoring, data management and data analysis of the study.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

Ethics Committee at Regional Chamber of Physicians in Rzeszów, approved 14 February 2019 (Poland); Central Ethic Committee IRCCS Lazio, Sezione IFO, Fondazione Bietti, approved 15 March 2019 (Italy); Regional Authority for Consumer Protection Saxony‐Anhalt‐Ethic Committee of the Federal State Saxony‐Anhalt, P.O. Box 1802, 06815 Dessau‐Roßlau, approved 12 July 2019 (Germany). In accordance with § 42 para.1 of the medicines law (Arzneimittelgesetz AMG), in the version published on 12 December 2005 (BGBI. I I S. 3394), amended by article 2 of the law dated 19 October 2012 (BGBI. I S. 2192), a favourable opinion was granted for the abovementioned clinical evaluation of a drug in humans by the ethics committee of the Federal State Saxony‐Anhalt.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 The GEDACNE study group.

Appendix S2 Complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Appendix S3 Statistical analyses.

Table S1 Study discontinuation.

Table S2 Absolute change from baseline to week 12 in total lesion count.

Table S3 Primary outcomes in patients stratified by age.

Table S4 Primary outcomes in patients stratified by sex.

Table S5 Primary outcomes in patients stratified by Investigator Global Assessment scores of 3 and 4 at baseline.

Table S6 Adverse and serious adverse events in the safety set.

Table S7 Patient‐reported outcome measure: overall application site irritation – end of 12‐week treatment period.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all study investigators (GEDACNE Study Group; see Appendix S1) and personnel for their involvement and contribution to the study. Furthermore, the authors thank Katja Martin (MEDTEXTPERT, funded by PPM Services S.A., Switzerland) for the medical writing and editorial assistance, and Simona di Paola (VALOS SRL, Italy) for the statistical review.

The GEDACNE Study Group is provided in Appendix S1.

Plain language summary available online

References

- 1. Lynn D, Umari T, Dellavalle R, Dunnick C. The epidemiology of acne vulgaris in late adolescence. Adolesc Health Med Ther 2016; 7:13–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ghodsi SZ, Orawa H, Zouboulis CC. Prevalence, severity, and severity risk factors of acne in high school pupils: a community‐based study. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129:2136–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380:2163–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dreno B, Bordet C, Seite S, Taieb C; ‘Registre Acné’ Dermatologists. Acne relapses: impact on quality of life and productivity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33:937–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Altunay IK, Özkur E, Dalgard FJ et al. Psychosocial aspects of adult acne: data from 13 European countries. Acta Derm Venereol 2020; 100:adv00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moradi‐Tuchayi S, Makrantonaki E, Ganceviciene R et al. Acne vulgaris. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015; 1:15029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thiboutot DM, Dréno B, Abanmi A et al. Practical management of acne for clinicians: an international consensus from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78:S1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aslam I, Fleischer A, Feldman S. Emerging drugs for the treatment of acne. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2015; 20:91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Conforti C, Chello C, Giuffrida R et al. An overview of treatment options for mild‐to‐moderate acne based on American Academy of Dermatology, European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, and Italian Society of Dermatology and Venereology guidelines. Dermatol Ther 2020; 33:e13548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Draelos ZD, Carter E, Maloney JM et al. Two randomized studies demonstrate the efficacy and safety of dapsone gel, 5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56:439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alkhodaidi ST, Al Hawsawi KA, Alkhudaidi IT et al. Efficacy and safety of topical clascoterone cream for treatment of acne vulgaris: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized placebo‐controlled trials. Dermatol Ther 2021; 34:e14609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eichenfield LF, Sugarman JL, Guenin E et al. Novel tretinoin 0.05% lotion for the once‐daily treatment of moderate‐to‐severe acne vulgaris in a preadolescent population. Pediatr Dermatol 2019; 36:193–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harper JC, Roberts WE, Zeichner JA et al. Novel tretinoin 0.05% lotion for the once‐daily treatment of moderate‐to‐severe acne vulgaris: assessment of safety and tolerability in subgroups. J Dermatolog Treat 2020; 31:160–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Camera E, Ludovici M, Tortorella S et al. Use of lipidomics to investigate sebum dysfunction in juvenile acne. J Lipid Res 2016; 57:1051–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shi Q, Tan L, Chen Z et al. Comparative efficacy of pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions for acne vulgaris: a network meta‐analysis. Front Pharmacol 2020; 11:592075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zouboulis CC, Baron JM, Böhm M et al. Frontiers in sebaceous gland biology and pathology. Exp Dermatol 2008; 17:542–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Briganti S, Flori E, Mastrofrancesco A, Ottaviani M. Acne as an altered dermato‐endocrine response problem. Exp Dermatol 2020; 29:833–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dozsa A, Mihaly J, Dezso B et al. Decreased peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma level and signalling in sebaceous glands of patients with acne vulgaris. Clin Exp Dermatol 2016; 41:547–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Downie MM, Sanders DA, Maier LM et al. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor and farnesoid X receptor ligands differentially regulate sebaceous differentiation in human sebaceous gland organ cultures in vitro . Br J Dermatol 2004; 151:766–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mastrofrancesco A, Ottaviani M, Cardinali G et al. Pharmacological PPARγ modulation regulates sebogenesis and inflammation in SZ95 human sebocytes. Biochem Pharmacol 2017; 138:96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ottaviani M, Flori E, Mastrofrancesco A et al. Sebocyte differentiation as a new target for acne therapy: an in vivo experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:1803–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Slanec Higgins L, DePaoli AM. Selective peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) modulation as a strategy for safer therapeutic PPARγ activation. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 91:267S–72S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pirat C, Farce A, Lebègue N et al. Targeting peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptors (PPARs): development of modulators. J Med Chem 2012; 55:4027−61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Layton AM, Eady EA, Thiboutot DM et al. Identifying what to measure in acne clinical trials: first steps towards development of a core outcome set. J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137:1784–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 The GEDACNE study group.

Appendix S2 Complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Appendix S3 Statistical analyses.

Table S1 Study discontinuation.

Table S2 Absolute change from baseline to week 12 in total lesion count.

Table S3 Primary outcomes in patients stratified by age.

Table S4 Primary outcomes in patients stratified by sex.

Table S5 Primary outcomes in patients stratified by Investigator Global Assessment scores of 3 and 4 at baseline.

Table S6 Adverse and serious adverse events in the safety set.

Table S7 Patient‐reported outcome measure: overall application site irritation – end of 12‐week treatment period.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.