Abstract

Background

Cognitive–communication difficulties are often associated with dementia and can impact a person's ability to participate in meaningful conversations. This can create challenges to families, reflecting the reality that people living with dementia rarely have just one regular conversation partner, but interact with multiple family members. To date, there is limited evidence of the impact of changes in communication patterns in families. A family systems approach, with foundations in psychology, can be used to explore the impact of communication difficulties on multiple different family members, including the person living with dementia and potential coping strategies used by individuals, together with the family as a whole.

Methods & Procedures

A systematic review of primary qualitative research was conducted to identify and examine research exploring communication and interaction within families living with dementia. Studies were identified through a comprehensive search of major databases and the full‐text articles were subject to a quality appraisal. We conducted a thematic analysis on the literature identified to consider the role of families in supporting communication for people with dementia.

Outcomes & Results

The searches identified 814 possible articles for screening against the eligibility criteria. Nine articles were included in the final review. Three major themes emerged from the analysis of the included studies: (1) ‘identities changing’ reflected how interactions within the family systems impacted on identities; (2) ‘loss’ reflected the grief experienced by families due to changes in communication; and (3) ‘developing communication strategies’ highlighted strategies and approaches that families affected by dementia may use organically to engage in meaningful interactions and maintain connection. Only one study explicitly used a family systems approach to understand how families manage the changes in interaction resulting from dementia.

Conclusions & Implications

The findings may usefully inform the clinical practice of speech and language therapists in terms of communication strategies and coping mechanisms that may be advised to facilitate connection in families living with dementia. Further research using a family systems approach to exploring communication in dementia may help to support the implementation of family‐centred practice as recommended in policy.

What this paper adds

What is already known on the subject

There is increasing recognition of the impact of dementia on whole families and the need for family‐centred interventions to enhance quality of life. However, much of the research to date that explores communication within families affected by dementia examines interaction between dyads, largely overlooking the roles and skills of other familial communication partners. To the authors’ knowledge, there has been no previous review of the literature using a family systems approach, which has the potential to inform clinical practice of those working in dementia care.

What this paper adds to existing knowledge

The review examines and understands what is known about the approaches used by families affected by communication changes resulting from dementia to preserve connection. It collates the evidence from qualitative studies examining approaches and strategies used by individual conversation partners, including people with dementia, as well as the family system as a whole, to facilitate meaningful interactions, and proposes recommendations for clinicians working in this field. Furthermore, we consider the potential benefits of using a family systems approach to understand the context of people living with dementia and how this could enhance communication, personhood and well‐being.

What are the potential or actual clinical implications of this work?

This review highlights practical conversation strategies and interactional approaches that may serve to enhance communication and preserve relationships between people with dementia and their family members. Such techniques have the potential to be advised by Speech and Language Therapists working in dementia care as part of tailored, relationship‐centred care and support that they provide.

Keywords: communication, dementia, family

INTRODUCTION

There is a rich literature base that proposes people with dementia experience a decline in a variety of cognitive–linguistic skills, particularly in relation to word‐finding difficulties, reduced verbal fluency, difficulties with comprehending conversation and changes in social communication (Bourgeois & Hickey, 2009; Kindell et al., 2017). Cognitive–communication difficulties such as these can impact on a person's ability to participate in meaningful conversations and maintain key relationships, often leading to reduced self‐esteem, social isolation and reduced quality of life overall (Volkmer, 2013).

Speech and language therapy (SLT) can be beneficial for people living with dementia, in terms of providing individuals with tailored support to adapt to communication changes they experience and maintain connections with others in a meaningful way (Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT), 2014). Of course, it is not only people with dementia who must adjust to changes in everyday interactions but also their key conversation partners, such as relatives and friends (Brewer, 2005). Egan et al. (2010) proposed that difficulty communicating is often cited by families as the most challenging consequence of dementia.

To our knowledge, the majority of the published literature regarding communication and dementia focuses on how dyads operate (Savundranayagam et al., 2005; Small et al., 2000), with a focus on pathology largely influenced by the biomedical model and researchers exploring links between communication problems and the ‘burden’ placed on the carer (Savundranayagam & Orange, 2011, 2014). With many studies focusing solely on the perspective of a spouse or partner, seen as a single representative of ‘family’, Keady and Harris (2009) emphasize that for a long time the lived experience of dementia has been somewhat ignored. Furthermore, people with dementia have been curiously isolated from their broader family network, including adult children and grandchildren, in both literature and policy. Though not within the scope of this current paper, the valuable role of the wider social network including friends and neighbours in supporting people with dementia to remain socially active has also largely been overlooked (Ward et al., 2018). However, as a result of the paradigmatic shift in recent years towards relationship‐focused interventions (Keady & Nolan, 2003; Watson et al., 2012), there is increasing awareness that a diagnosis of dementia has an impact on an entire family, not just within a dyad, and this is increasingly reflected in updated policy, including the Prime Minister's Challenge on Dementia (Department of Health, 2015), the Dementia Action Plan for Wales (Welsh Government, 2018), in addition to clinical guidelines (National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2018; Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCP), 2020).

Family systems theory (Bowen, 1978), developed originally in the field of social work and psychotherapy (Haefner, 2014), lends itself as a theoretical framework that can support family‐centred practice in dementia; care that involves collaboration with the family and delivery of support focused around the needs of the whole family (Kokorelias et al., 2019). Frequently referred to within early communication development research (McKean et al., 2011; Meyers, 2007; Wright & Benigno, 2019), family systems theory works to understand interactions and behaviour between multiple family members within a family system, as opposed to a dyad, recognizing the family as a complex social system, and emphasizes the interdependence of individuals in the family (Bowen, 1978). Furthermore, family systems theory appreciates that communication patterns, roles and identities can be influenced by all members in the family, and interactions are reciprocal in nature. The approach has the potential to inform the clinical practice of speech and language therapists working with people with acquired communication disorders, as it offers a practical framework with which to understand the perspectives, skills and needs of multiple conversation partners within the family, which can subsequently support the development of tailored interventions to aid communication (Purves & Phinney, 2012).

Frequently used by speech and language therapists, the World Health Organization's (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (WHO, 2001) framework can facilitate an in‐depth, holistic exploration of the facilitators and barriers in relation to a person's communication difficulties. This of course includes the communication environment, and the roles and skills of conversation partners, such as family members. Indeed, within clinical practice, it is well accepted that many people, including people living with dementia, rarely have just one regular conversation partner, but in fact, often have multiple, overlapping communicative responsibilities; and that meaningful conversations are not simply restricted to family members in caregiving roles (Purves & Phinney, 2012). Nevertheless, a preliminary search conducted in October 2020 to identify any existing systematic reviews regarding this topic found that research in this area is limited. Consequently the current literature does not appear to be representative of the complex nature of communication between a person with dementia and multiple family members, often of different generations.

Identification of successful communication strategies or techniques used by the person with dementia or family members to overcome changes in communication, in addition to helpful coping mechanisms, may serve to inform future therapeutic interventions for people with dementia and their conversation partners. Being able to provide evidence‐based therapies, reflecting the lived experience of dementia, as well as perspectives of family members, could have significant benefits in terms of supporting family resilience, maintaining meaningful relationships, preserving personhood and identity, enhancing well‐being and potentially delaying transition into a residential care setting (Kindell et al., 2017; RCSLT, 2014).

Aims

Given the apparent gap in the literature, the objective of this paper is to systematically identify and examine research exploring communication and interaction within families living with dementia. In particular, using the family systems perspective we ask, how do families living with dementia experience changes in communication?

METHODS

Study design

In order to answer the research question, a systematic review of qualitative research investigating communication in families living with dementia was deemed most appropriate. Systematic reviews of qualitative literature combine evidence from multiple studies to generate comprehensive data that can be explored for patterns, differences and similarities and extend what is known about a research topic (Downe et al., 2019; Munn et al., 2018).

Qualitative research aims to explore thoughts, feelings and beliefs of people surrounding particular phenomena, and values idiosyncratic experiences, giving voice to the participants involved. Qualitative methods can provide a richer, more holistic understanding of a concept than numerical data arising from quantitative investigations. Furthermore, there is increasing appreciation of qualitative evidence in the field of healthcare research as it facilitates greater understanding of the complexity of living with and managing health conditions (Bowling, 2002; Bradshaw et al., 2017).

The methodology used in this review follows some of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) approach to conducting a qualitative systematic review in terms of developing the inclusion criteria, searching, screening and appraising the quality of the evidence (Lockwood et al., 2020). However, this review is exploring how families living with dementia experience changes in communication, rather than generating ‘guidance for action’ (Lockwood et al., 2020). Consequently, a thematic synthesis is used to identify the important topics emerging across the included studies that address the aim of this review.

Search strategy

The electronic databases PSYCINFO, Medline, Web of Science and CINAHL were searched for peer‐reviewed published research. In the development of the research question, the PEO (population, exposure, outcomes) framework was used (Khan et al., 2003), as outlined in Table 1. Terms that best represented ‘communication in families living with dementia from a family system perspective’ were used. Further analysis of terms used across titles and abstracts retrieved informed a secondary search, and the final terms used are detailed in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Search strategy using the PEO framework

| Population (and their problem) | Exposure | Outcomes or themes |

|---|---|---|

| People with dementia | Communication changes resulting from dementia | Views/experiences/strategies of the person with dementia |

| Family members of people with dementia | Views/experiences/strategies of the family members of the person with dementia |

Note: The PEO framework serves to define the key concepts in order to formulate a qualitative research.

TABLE 2.

Search term development

| Question subcomponents | Family | People with dementia | Communication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Search terms | Family | Dementia | Communication |

| Family members | Alzheimer's | interaction | |

| Family unit | Vascular dementia | conversation | |

| Family relations | |||

| Family network | Frontotemporal dementia | Interpersonal communication | |

| Family system | |||

| Semantic dementia | Verbal communication | ||

| Family carer | |||

| Family caregivers | Lewy body dementia | Non‐verbal communication | |

| Carer* | |||

| Caregiver* | |||

| Adult‐children | Primary progressive aphasia | Discourse | |

| Children | |||

| Grandchildren | |||

| Young onset dementia | |||

| Early onset dementia |

Note: The following terms were searched across the four databases: famil* OR ‘family members’ OR ‘family unit’ OR ‘family system’ OR ‘family network’ OR ‘family relations’ OR (‘family carers’) OR carer* OR caregiver* OR (‘family caregiver’ OR ‘family caregivers’) OR ‘adult‐children’ OR children OR grandparent* OR grandchild*) AND if(dementia OR alzheimer* OR ‘vascular dementia’ OR ‘lewy body dementia’ OR ‘frontotemporal dementia’ OR ‘semantic dementia’ OR ‘primary progressive aphasia’ OR ‘young onset dementia’ OR ‘early onset dementia’) AND if (communicat* OR interaction OR conversation OR ‘interpersonal communication’ OR ‘verbal communication’ OR ‘non‐verbal communication’ OR discourse. The search was conducted in December 2020.

Table 3 outlines the inclusion and exclusion criteria used for the purpose of this review, and is described in further detail below.

TABLE 3.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Peer‐reviewed studies, using qualitative methods (including mixed‐methods studies if they included a qualitative element) | Studies not published in English |

| Studies investigating communication in dementia using a family system approach (describing communication between a person with dementia and at least 2 or more family members) | Grey literature |

| Adult with a diagnosis of dementia of any subtype or age | Studies focusing on other progressive neurological conditions or mental conditions other than dementia (e.g., Parkinson's disease, Schizophrenia, depression) |

| Studies published between 2009 and 2020 | Studies focusing on communication between people with dementia, family members and health professionals |

| Studies focused on the delivery of a communication therapy or intervention, development of a framework, guideline or policy | |

| Studies exploring a family system with dementia in relation to a general concept, e.g., coping with diagnosis, and does not describe communication difficulties |

Inclusion criteria

Due to the nature of the research topic and area of investigation, it was decided that peer‐reviewed journal articles using a qualitative design would be included. Mixed‐methods studies were also included if a qualitative element was incorporated. It was agreed that papers that explicitly consider or investigate communication using a family systems approach, seeking to understand communication from the perspective of each individual family member, would be included as well as articles that discussed or observed communication between the person living with dementia and at least two other family members, that is, not within a dyad. The timeframe for inclusion of the papers was 2009–20 to ensure that papers were recent and reflective of current thinking post‐introduction of various dementia strategies and guidelines published in the UK in 2009 (Department of Health, 2009; NICE, 2018).

Studies working with people with dementia of any subtype were included, in addition to any age of onset, with the hope of capturing research regarding rarer dementias in addition to more common aetiologies.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded from this review at title/abstract screening if they were not published in English, in order to mitigate financial and time implications of translation. Grey literature, that which is not controlled by commercial or academic publishers including policy documents, theses, technical reports and blogs (Adams et al., 2016), together with opinions pieces, were also not considered within this review, to ensure that only high quality, peer‐reviewed studies were included and analysed. Studies focusing on progressive neurological conditions or mental health conditions other than dementia (such as Parkinson's disease, depression, frailty) were also excluded. Articles focusing on communication between people with dementia, a family member and health professionals were also excluded, as they did not examine communication within the internal family system. Further papers were excluded if the study focused on delivery of a communication therapy/training programme, development of a guideline, policy or framework, or used solely quantitative methods. At the stage of full‐text review, final studies were excluded if communication was explored solely within a dyad rather than amongst multiple family members, or if the family system and its roles were investigated generally, such as in response to the diagnosis, and did not examine communication.

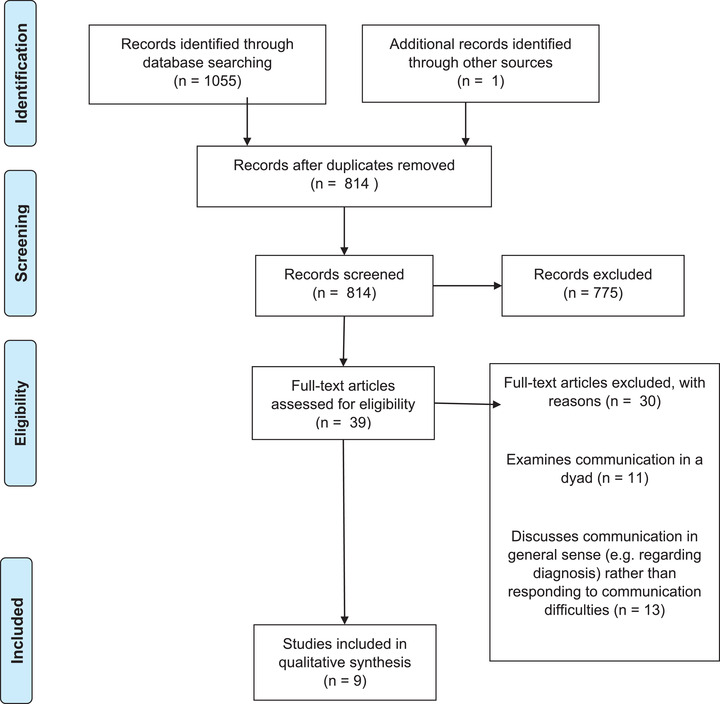

Figure 1 describes the selection process of studies included and excluded for the purpose of this review.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of the search strategy [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Selection process

Studies were collated using RefWorks software and duplicates were removed. Screening of articles was conducted by the lead author and a sample of excluded studies were discussed and checked by all three authors to aid interrater reliability of the selected papers, discussion was carried out between the three authors, with regards to any papers where it was unclear if the inclusion criteria was met.

Quality appraisal

In order to assess the quality of the chosen papers within the review, a two‐step process was used. Initially, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (2015) qualitative checklist was used as a framework to evaluate each paper. Although it has previously been suggested that the CASP may only facilitate appraisal at a superficial level in comparison with other checklists available (Hannes et al., 2010), it can allow relatively rapid comparison and appraisal of several studies in terms of their methodologies, data analysis, ethical issues and impact of the research. Furthermore, due to the quick application of this tool, it is a critical appraisal checklist most favoured by health and social care clinicians, and so the author was already familiar with using the CASP in evaluating evidence relevant to clinical practice.

Second, the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research (2015) was also used to explore in more detail the use of appropriate theoretical frameworks and philosophical perspective underpinning the articles retrieved.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from the selected papers by the first author and a table was created to record the relevant data from each of the chosen studies. First, the study aims, geographical location, participant demographics, methodology, epistemology and any relevant theoretical frameworks, and the key findings from the study, were extracted from each article. Table 4 presents the characteristics of included studies and considerations regarding quality appraisal. Second, primary findings from each study, along with direct quotes from participants and researchers’ conclusions were extracted. Table 5 presents the primary findings of each study included in the review. Tables 4 and 5 are both included within supplementary information.

TABLE 4.

Summary of characteristics of included papers and quality appraisal

| No. | Author(s) and title | Country | Focus | Participants | Methods | Considerations regarding quality of the research (CASP) | Score (1–3, where 1 = high quality and 3 = lowest quality) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hyden and Samuelsson (2019) ‘So they are not alive?: Dementia, reality disjunctions and conversational strategies’ | Sweden | Explored the collaboration of people with dementia and their family members in conversation in relation to managing ‘reality disjunctions’ | 1 female with Alzheimer's disease, her daughter and daughter‐in‐law | Qualitative methodology | Appropriate underpinning framework discussed in introduction | 2 |

| Part of a larger ethnographic study | Methods appropriate for research aim | ||||||

| Case study | Direct quotes used in qualify themes reported | ||||||

| Video recordings taken from a series of interactions of a lady with Alzheimer's disease, her daughter and daughter‐in‐law | Discusses findings that contradict previous research findings | ||||||

| Conversation analysis | Not clear how themes were extracted from the transcripts | ||||||

| Acknowledges limited data within present study and also existing field, meaning that conclusions should be interpreted with caution | |||||||

| Appears to address a gap in the literature related to the collaborative effort of people with dementia and family members in carrying out ‘facework’ | |||||||

| 2 | Jones (2015) ‘A family living with Alzheimer's disease: The communicative challenges’ | UK | Examined the role of communication deterioration in dementia in the role of family relationships | 1 female with Alzheimer's disease, her daughter and son‐in‐law | Case study | One researcher involved in the data collection and analysis therefore, involvement of other researchers may be needed to increase credibility—no discussion regarding triangulation or respondent validation | 2 |

| Conversation analysis of telephone calls between the female with dementia to her daughter and son‐in‐law over a 2‐year period | Detailed description from author of conversation analysis process and why it was an appropriate method for this study. | ||||||

| Sample of the interactions were used to explain findings | |||||||

| 3 | Kindell, Sage, Wilkinson, and Keady (2014) ‘Living with semantic dementia: A case study of a family's experience’ | UK | Explored the experiences of wife and son caring for a husband/father living with semantic dementia | 1 male with semantic dementia, his wife and son | Case study | Data triangulation discussed | 1 |

| Narrative inquiry | Methods explained in detail to enable replication of the study | ||||||

| Thematic narrative analysis of interview data | Data analysis/coding described step by step | ||||||

| 4 | Miller‐Ott (2018) ‘Just a Heads Up, My Father Has Alzheimer's’: Changes in communication and Identity of adult children of parents with Alzheimer's disease | USA | Explored how adult children perceived changes in communication with and about their parent with dementia, through the lens of identity | 12 adult children of people living with dementia (6 males and 6 females) | Semi‐structured interviews | Clear theoretical framework underpinning the study—‘identity work’ | 1 |

| Thematic analysis | Disadvantages of convenience and snowball sampling | ||||||

| Data triangulation discussed—themes identified were discussed with 2 other researchers | |||||||

| Member‐checking also discussed—results discussed with 3 randomly selected participants to verify analysis | |||||||

| Very limited previous research in this area to reinforce findings, but makes suggestions for future research | |||||||

| 5 | Miron et al. (2019) ‘Young Adults’ concerns and coping strategies and related to their interactions with their grandparents and great‐grandparents with dementia’ | USA | Explored coping strategies of young adults when interacting with their grandparent with dementia | 14 college students with a grandparent or great‐grandparent living with dementia (12 women, 2 men) | Phenomenology | Clear theoretical framework underpinning investigation | 1 |

| Focus groups and questionnaires | Example list of topic questions for interviews provided | ||||||

| Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) used to analyse data | Quotes from the data used to support findings, but also analysed contradictory findings and linked to literature | ||||||

| Multiple analysts were used, in addition to respondent validation—fourth specialist dementia researcher, families of people with dementia and care workers to validate findings | |||||||

| Data saturation discussed | |||||||

| Author did not discuss how ethically participants were supported if they became emotional during data collection—further information is required regarding protection from psychological harm | |||||||

| 6 | Purves and Phinney (2012) ‘Family voices: A family systems approach to understanding communication in dementia’ | Canada | Explores the impact of communication impairment resulting from dementia on a family unit | Two families: | Ethnography | Interview guide provided and conceptual framework that influenced interview questions | 1 |

| A lady with Alzheimer's disease, her husband and 3 adult children | Semi‐structured interviews with family members of people living with dementia and person with dementia | In‐depth description of data analysis process | |||||

| A lady with primary progressive aphasia, and her 4 adult children | Conversation analysis of people living with dementia and their families | Triangulation of data across the different research approaches completed | |||||

| Member‐checking discussed. Follow‐up interviews were conducted to ensure that participants’ views were interpreted correctly | |||||||

| 7 | Schaber et al. (2016) ‘Understanding family interaction patterns in families with Alzheimer's disease’ | USA | Explores changes in family interaction patterns when 1 family member had Alzheimer's disease | 15 participants, from different families, with a family member living with Alzheimer's disease (2 wives, 10 daughters, 2 daughters‐in‐law, and 1 niece) | Modified analytic induction | Clear and appropriate theoretical framework used to underpin the research | 2 |

| Convenience sampling used | |||||||

| Interview protocol and questions provided | |||||||

| Data saturation discussed | |||||||

| Discusses reduction of bias, interresearcher reliability and researcher dyads to analyse data | |||||||

| No consideration/ mention of ethical considerations | |||||||

| Contradictory data discussed | |||||||

| Discusses implication for practice of occupational therapists in family‐centred interventions | |||||||

| 8 | Tipping and Whiteside (2015) ‘Language reversion among people with dementia from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds: The family experience’ | Australia | Explores the experiences of family members who have a relative experiencing language reversion as a result of dementia | 7 participants from different families (6 females and 1 male) | Phenomenology | Interview questions used not reported | 2 |

| In‐depth interviews | Discusses researcher reflexivity through use of debriefing | ||||||

| Purposive sampling method | Describes interpretation checking of findings | ||||||

| Sample included family members both in caring roles and not in caring roles | Acknowledges small sample size | ||||||

| Thematic analysis in style of Braun and Clarke (2006) | Limited discussion of contradictory findings | ||||||

| Discusses implications of the research findings for policy and care settings, and need for further research in this area | |||||||

| 9 | Walmsley and McCormack (2014) ‘The dance of communication: Retaining family membership despite severe non‐speech dementia’ | Australia | Explored communication within a family with a relative with severe dementia and non‐verbal communication | 4 family groups with a relative with severe dementia with limited verbal communication: | Phenomenology | Epistemology and methods deemed appropriate to meet research aims | 1 |

| A man and his wife | Thematic analysis | Explicit description of steps taken to conduct thematic analysis | |||||

| A lady, and her son, daughter‐in‐law and great‐granddaughter | Reflexivity and bias discussed and efforts made to mitigate this | ||||||

| A lady, her husband and their friend | Interpretation of findings were discussed and interpreted by multiple researchers | ||||||

| A lady, her daughter and great‐granddaughter |

TABLE 5.

Data extraction table

| No. | Author(s) | Title | Primary findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hyden and Samuelsson (2019) | So they are not alive?: Dementia, reality disjunctions and conversational strategies | People with dementia and their relatives regularly engage in ‘facework’—not pursuing argumentative discussions to preserve relationships |

| ‘Reality disjunctive contributions’ happen often in conversation with people with dementia—occur as a result of hearing problems, working memory problems and narratives generated by people with dementia | |||

| Family members and the person with dementia all used ‘politeness strategies’—person with dementia was aware of their relatives as more linguistically competent and so agreed with their comments—demonstrates people with dementia as active participants in conversation | |||

| Family members focused on the benefit of interacting together rather than questioning the social status of the person with dementia | |||

| 2 | Jones (2015) | A family living with Alzheimer's disease: The communicative challenges | Communication challenges that arise between people with dementia and their family members occur as a result of both cognitive–linguistic deficits and interactional attempts by family members |

| Family members may develop strategies in an attempt to support the person with dementia but may subsequently generate more ‘trouble’ or communication breakdown | |||

| People with dementia also use strategies to convey communicative competence during interactions with family members, despite their cognitive deficits | |||

| Understanding communication difficulties as co‐constructed suggests that family members can take an active role in co‐managing interactions with their family member with dementia, in order to improve their communication together and maintain their relationships | |||

| 3 | Kindell et al. (2014) | Living with semantic dementia: A case study of a family's experience | Four distinct and recurring themes: |

| Living with routines—family had adjusted to the communicative routines of the person, as well as wider practical routines in everyday life | |||

| Policing and protecting—family members tend to monitor the behaviour of the person with dementia in terms of reducing risks, as well as monitoring the person's communication towards people outside of the family, which brought tension within the family | |||

| Making connections—family members frequently attempted to engage their relative with dementia socially, by initiating conversations regarding the person's favourite topics and became more aware of the person's use of non‐verbal communication to communicate a message | |||

| Being adaptive and flexible—family expressed having to adapt to the person's repeatedly changing personality, and the subsequent impacts on their interactions together | |||

| 4 | Miller‐Ott (2020) | ‘Just a Heads Up, My Father Has Alzheimer's’: Changes in communication and identity of adult children of parents with Alzheimer's disease | Communicating with a ‘same but different’ parent |

| Adult children reported communicating in multiple roles, e.g., having be both parent and child to their parent with dementia, but also having to teach their own child how to communicate with grandparent with dementia | |||

| Participants reported having to correct or ‘reprimand’ their parent's communication and/behaviour | |||

| Adult children adopted a role as ‘gatekeeper’ for their parent's private information | |||

| 5 | Miron et al. (2019) | Young adults’ concerns and coping strategies and related to their interactions with their grandparents and great‐grandparents with dementia | Grandchildren of people with dementia used coping strategies during interactions with their grandparent that were driven by two motives: maintaining solidarity (wanting to maintain the interaction with their relative and maintain the other's personhood) and dealing with conflict (managing their concerns about their own lack of skills and knowledge when communicating with their relative) |

| Grandchildren reported concerns about not being able to maintain a connection with the grandparent with dementia, due to problems with knowing what to say, how to interact with a person whose identity is continually changing, and concerns about another family member being in the interaction with them | |||

| Grandchildren use problem‐solving strategies such as planning conversation topics in advance, using other members of the family as ‘interaction buffers’, seeking family support, and reminding their grandparent of self in an attempt to maintain connection with their grandparent | |||

| 6 | Purves and Phinney (2012) | Family voices: A family systems approach to understanding communication in dementia | Using a family system approach to investigating communication can be helpful in fully understanding the impact of communication impairment on the family |

| Family members were consistent in their descriptions of the change in communication in the person with dementia, but their responses to the person's communication changes were remarkably individual | |||

| Families reported a loss of complex conversations that they used to have with their relative with dementia, which also contributed to a sense of loss of their previous relationship | |||

| Family members developed new strategies to enhance communication, as well as drawing on long‐standing family patterns of communication to meet their own conversational needs, and needs of the family as a whole | |||

| A person with dementia may be aware of the impact of their communication difficulties on other members of the family | |||

| Managing conversational challenges was not associated with caregiving, but within all of the relationships within the family. All family members acknowledged that supporting the communication of the person with dementia was a shared responsibility across all family members of the family network | |||

| 7 | Schaber et al. (2016) | Understanding family interaction patterns in families with Alzheimer's disease | Families reorganize and restructure post‐diagnosis |

| Family roles are ‘re‐assigned’ | |||

| Families try to maintain shared rituals in terms of past activities and communication rituals | |||

| Ways of demonstrating affection towards the person with dementia change—more non‐verbal methods | |||

| Emotions demonstrated in family interactions intensify with Alzheimer's disease | |||

| Families altered their own style of communication to meet their family member's need for intimacy and connection | |||

| 8 | Tipping and Whiteside (2015) | Language reversion among people with dementia from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds: The family experience | Situational factors, such as reminiscence and frustration can result in language reversion |

| Language reversion can result in further communication problems for families of people living with memory problems | |||

| The Person Experiencing Language Reversion (PELR) may become frustrated as others cannot understand what they are saying. | |||

| Family members feel the person experiencing language reversion may be embarrassed | |||

| Family members work as a ‘gatekeeper’ for interactions with those outside the family—translating and interpreting the person's language and behaviour to help others understand | |||

| Family members experience a sense of grief and loss following language reversion due to changes in roles, relationships and being able to communicate with their family members like before | |||

| Conflict and family separation could occur as a result of language reversion and dementia—some family members are unsure how to react to the actions and communication of the person with dementia | |||

| Family members develop and use coping strategies such as living in the moment, using different non‐verbal means, and reminders to prompt the person to speak in the common language | |||

| 9 | Walmsley and McCormack (2014) | The dance of communication: Retaining family membership despite severe non‐speech dementia | Families with dementia engage in ‘the dance of communication’—positive and negative actions to communicate. Families engage in both ‘in‐step’ and ‘out of‐step’ communication, depending on presumptions of awareness of the person with dementia, timing of responses, perceived interpretation of the person with dementia's attempt to communicate, and pre‐existing relational patterns |

| ‘In‐step’ interactions demonstrated harmony and reciprocity in communication | |||

| ‘Out of step’ interactions demonstrated disharmony, syncopation and vulnerability in communication | |||

| Strategies to maintain communication included touch, shared stories about previous roles and interests, and reminiscence | |||

| People with dementia retained awareness of their family interaction at levels exceeding their expected awareness according to the CDR (clinical dementia rating) scale—and demonstrated retained ability of emotional and relational life |

Analysis and synthesis

In order to identify and systematically analyse themes within from the research, thematic analysis in the style of Braun and Clarke (2006) was conducted by the first author. This involved the author becoming familiar with the data presented in the selected papers, reading through each paper and making notes regarding initial impressions from the data. A summary table of key findings of each paper was created. Next, initial coding based on recurring concepts was applied, using open coding, and codes were modified as the analysis developed. Patterns derived from the data that were helpful in answering the research question were then identified and reviewed with the two other researchers, and final themes and sub‐themes recognized. Themes were then reviewed again against codes to ensure that the data was truly supportive of the themes identified and the ‘essence’ of each theme identified (Braun & Clarke, 2006). A diagram was created to visually represent the main themes and subthemes derived from the data following discussion with the research team. These themes are analysed and presented below in the context of the existing literature.

RESULTS

Summary of the included studies

The initial database search yielded 1055 papers (Figure 1). One further paper that met the inclusion criteria was identified through manual search. A total of 242 studies were excluded due to duplication, and a further 775 papers were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria at review of titles and abstracts. The remaining 39 articles were then assessed for full‐text eligibility. A final nine papers were included for the purpose of this review.

The studies included five case studies (Hyden & Samuelsson, 2019; Jones, 2015; Kindell et al., 2014; Purves & Phinney, 2012); a qualitative analysis consisting of focus groups (Miron et al., 2019); three qualitative studies consisting of in‐depth and semi‐structured interviews (Miller‐Ott, 2018; Schaber et al., 2016; Tipping & Whiteside, 2015); and a phenomenological study using thematic analysis to analyse communication in video recordings (Walmsley & McCormack, 2014). Further detail regarding the aims, methodologies and quality appraisal of each study can be found in Table 4.

The studies can be seen to be divided into three categories: those that are exploring experience of communication in the family system using interviews and focus groups; those that are observing communication and analysing interactions and studies that used both approaches.

The CASP Qualitative Checklist was used to scaffold reflections regarding the quality of the selected papers. All nine papers included clearly stated their research aims, and used appropriate qualitative methodologies in order to address their research aims. The JBI checklist supported more in‐depth consideration of the theoretical frameworks underpinning each study. Of note, no studies were excluded from the review on the basis of their methodological quality, following the critical appraisal process.

Many of the papers describe their study designs, methodologies and data analysis in detail, improving confirmability of the research (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). With regards to credibility of the research, data triangulation and saturation are discussed in several the papers included (Kindell et al., 2014; Miller‐Ott, 2018; Miron et al., 2019; Purves & Phinney, 2012; Schaber et al., 2016), in addition to reflexivity and potential for bias (Kindell et al., 2014; Schaber et al., 2016) and relevant theoretical frameworks underpinning the research (Hyden & Samuelsson, 2019; Miller‐Ott, 2018; Miron et al., 2019; Purves & Phinney, 2012; Schaber et al., 2016; Walmsley & McCormack, 2014).

Findings from the qualitative synthesis

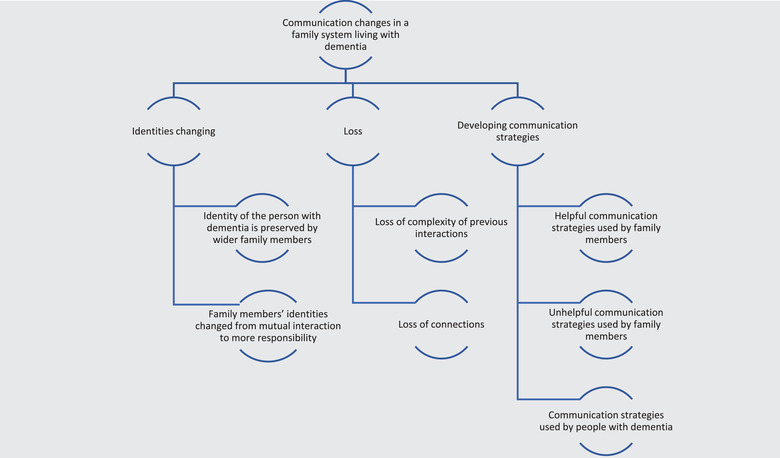

Three major themes were derived as a result of the analysis of the included studies. First, the theme ‘Identities changing’ echoed the transitions of roles within the family, as a result of dementia. ‘Identities changing’ consisted of two subthemes: ‘Identity of the person with dementia is preserved by wider family members’ and ‘Family members’ identities changed from mutual interaction to more responsibility’. The next major theme was ‘Loss’, which revealed the interactional and linguistic loss experienced by the family system with dementia. ‘Loss’ was therefore divided into two subthemes: ‘Loss of complexity of previous interactions’ and ‘Loss of connections’. The final major theme was ‘Developing communication strategies’, which signalled the way that family members, including the person with dementia, may adapt to communication changes and use techniques to manage communication difficulties. ‘Developing communication strategies’ consisted of three subthemes: ‘Helpful communication strategies used by family members’, ‘Unhelpful communication strategies used by family members’ and ‘Communication strategies used by people with dementia’. A visual representation of the overarching themes and subthemes are presented in Figure 2 and are discussed below.

FIGURE 2.

Representation of the overarching themes and subthemes derived from the qualitative analysis [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Identities changing

Maintenance of close family relationships is well‐accepted within the literature as important for the well‐being and identity of people with dementia (LaFontaine & Oyebode, 2014; Robertson, 2014). Several of the papers referred to the way in which identities and positions within the family system changed, in line with changes to their interactions (Jones, 2015; Kindell et al., 2014; Purves & Phinney, 2012; Schaber et al., 2016; Tipping & Whiteside, 2015).

Identity of the person with dementia is preserved by wider family members

Previous research has described how people living with dementia often maintain their physical identity, but progressively lose their personal identity, as a result of their deteriorating cognition and communication (Karner & Bobbitt‐Zeher, 2005).

Several papers in the review discuss the way families work to preserve the identity of the person with dementia through their joint communication. Kindell et al. (2014) discuss the way that families use collaborative storytelling to retain personhood. The authors note that families engage in ‘narrative scaffolding’, initiating favourite and shared topics between the person with dementia and family members, and remembering events from the past together, in order to maintain personal identity and connection with each other. At times this can present as an embodied activity, meaningful when people with dementia use non‐verbal communication to mitigate difficulties with verbal fluency and naming (Hyden, 2014). Likewise, Miron et al. (2019) found that grandchildren introduce reminiscence with their relative with dementia, with the intention of preserving their sense of self and personhood. They found adolescents encouraged their grandparent with dementia to recount their past, and tell their story, which helped them to retain a psychological connection with their relative, upholding what the authors characterize as ‘intergenerational solidarity’. Instigating reminiscence and using family narratives in this manner has been suggested to be fundamental in protecting the positioning of the person with dementia within the family system and its history (Hyden, 2011; Walmsley & McCormack, 2014; Werner et al., 2005).

Conversely, other adolescents in the same study emphasized the difficulty of communicating with their grandparent whose identity seemed to be ever‐changing, and this created a reluctance to interact. Purves and Phinney's (2012) findings reinforced this concept, that family members had to find a balance between carefully trying to preserve the identity of the person with dementia as a family member, avoiding conflict, whilst also being realistic about their fluctuating conversational competence. Miller‐Ott (2018) labelled this as ‘identity‐work’, protecting the personhood of the relative with dementia when difficulties in their communication present a risk to their previous identity. Equally, Kindell et al. (2014) suggested that families understand the importance of flexibility when interacting with their relative with dementia, so as to preserve the person's family identity. In their case study of a family affected by semantic dementia, the wife and son of a gentleman with semantic dementia described how changes in his personality had altered his interaction style, making him increasingly extroverted, and interested in strikingly different conversations topics than before. Kindell et al. (2014) proposed that his family had come to accept these changes, though challenging, in order to safeguard his role as a husband and father, though this was very different from before.

The notion of ‘same but different’ was also echoed in the study of Jones (2015), consisting of analysis of telephone conversations between ‘May’, a lady with dementia, and her family (daughter and son‐in‐law), which proposed that often there is ‘malalignment’ between the person with dementia's knowledge about their life, and their family's knowledge, secondary to deterioration in episodic memory. This concept is explored when May requests to go home, but is in fact already at her home. Forgetting important information about her identity, for example, where she lives, causes both her and her family anxiety and distress, which leads to further communication breakdown, as her daughter is unsure how to respond to her, in the context of her fluctuating identity. This idea is also reflected in the work by Schaber et al. (2016), in semi‐structured interviews with family members, as adult children expressed difficulty in supporting their parent with dementia when forgetting important autobiographical information, in addition to fluctuations in their identity, meaning that some days family members felt their relative with dementia was more ‘recognizable’, whilst on other days, their previous identity was less clear.

Family members’ identities changed from mutual interaction to more responsibility

In semi‐structured interviews with adult children of people with Alzheimer's disease, Miller‐Ott (2018) emphasized that participants experienced changes in their own identity, in particular to their traditional parent–child dynamic, to some extent, due to the communication difficulties they experienced within the family. Woolsey (2013) proposed that as the condition progresses, adult children often adopt more of a ‘parent’ role in caring for their parent living with dementia. Miller‐Ott (2018) suggested that adult children assume a new responsibility as a ‘gatekeeper communicator’ of their parent's private information, for example, determining when it is necessary to disclose their diagnosis to strangers, as a way to explain their relative's communication or behaviour, for example, if they were to say something inappropriate or potentially offensive to a stranger. Findings of Kindell et al. (2014), from the case study of the family living with semantic dementia, substantiate this notion, and illustrate how the wife and son felt obliged to undertake a parental role and monitor his communication and interactions with others. Changes in the gentleman's communication meant that he had become increasingly disinhibited and irritable around other people and his wife felt a duty to ‘police’ her husband's communication, to prevent him causing offence to others.

Adult children often adopt the identity of the family representative, explaining their relative's communication to others, including other relatives and those external to the family, and ‘coaching’ others on how best to communicate with the person with dementia (Miller‐Ott, 2018). Interviews with grandchildren of people with dementia also mirrored this concept (Miron et al., 2019; Schaber et al., 2016, Tipping & Whiteside, 2015; Walmsley & McCormack, 2014). Several participants discussed how older family members worked as ‘interaction buffers’ (Miron et al., 2019, p. 1033), ensuring the person with dementia was comfortable during the conversation, as well as providing topics to maintain the interaction, and supporting other relatives, such as younger generations, to take part in the conversation with their relative with dementia. These conclusions imply that it is not only the person with dementia who undergoes fluctuations in their identity, as a consequence of communication problems, but that family members also adopt new identities in order to encourage, engage and protect their relative with dementia during interactions.

Loss

Previous research focused around loss in family members affected by dementia has revealed the complexity of grieving for changes in relationships, particularly as a result of loss of familiarity and connection (Betts Adams et al., 2008). Many papers in this review highlighted the grief experienced by family members for losing idiosyncrasies of their communication with their family member before they developed dementia (Miller‐Ott, 2018; Purves & Phinney, 2012; Schaber et al., 2016; Tipping & Whiteside, 2015).

Loss of complexity of previous interactions

A number of the papers in this review detailed the ‘absence’ experienced by family members in relation to the habitual communication patterns that they used to experience with their family member with dementia (Miller‐Ott, 2018; Purves & Phinney, 2012). In the Miller‐Ott (2018) study, participants suggest a conflicting theme of ‘presence vs absence’, as their parent with Alzheimer's disease is still physically present in their lives, but psychologically, they experience a loss of their parent figure they communicated with prior to the onset of dementia.

Findings of Purves and Phinney (2012) reinforced this, as adult children expressed a sense of ‘missing’ their relative with dementia and the complexities and rituals of interactions that were characteristic of their past relationship. Even though the person with dementia was still present, they expressed a sense of loss in terms of the closeness of their prior relationship. Purves and Phinney (2012), along with Schaber et al. (2016) and Tipping and Whiteside (2015) highlighted the increased effort that was required from some family members to engage in interactions, which created a feeling of comparison and longing for the ease of family interactions in the past. These findings complement the previous work of LaFontaine and Oyebode (2014) who, through their systematic review, identified how families affected by dementia can feel detached, ‘living together but apart, in two different worlds’.

Loss of connections

This discord of ‘same but different’ causes further uncertainty in how to communicate with their relative and preserve their connection as it was before. Tipping and Whiteside (2015) interviewed family members of people with dementia experiencing language reversion, defined as the increased use of and ease of access to a person's first language in comparison with their second language, and a concept of loss was also conveyed in their narratives. However, this was particularly different from the loss that was reported by families whose relative with dementia was monolingual, in that relatives of bilingual or multilingual people with dementia were concerned that they may lose their connection with their relative with dementia altogether, if the person continued to increasingly use their first language which was not understood by the rest of the family. They expressed a sense of grief, of not being able to reliably identify a ‘way in’ to connect with their relative and articulated the regret they felt for not learning the first language of their relative with dementia at an earlier point in life. They did however, alike those interviewed by Miller‐Ott (2018), report changes in their parents’ ability to interact, noting a particular decline in the complexity of information transmitted, such as their relative no longer being able to verbally express complex emotions, and tending to revert back to simple, more concrete, conversation topics.

Developing strategies to maintain communication

Previous research has suggested that families may respond to communication breakdowns with their relative with dementia by adopting new conversation strategies (Watson et al., 2012). Some approaches identified by Watson et al. (2012) appeared to facilitate interaction, whilst others further inhibited successful communication; findings that were also mirrored in this current review (Hyden & Samuelsson, 2019; Kindell et al., 2014; Miller‐Ott, 2018; Miron et al., 2019; Purves & Phinney, 2012; Schaber et al., 2016; Tipping & Whiteside, 2015; Walmsley & McCormack, 2014). However, several studies within this review also highlighted the ways in which people with dementia develop communication strategies to manage communication breakdown within their family system, taking an active role to maintain connection (Hyden & Samuelsson, 2019; Jones, 2015; Kindell et al., 2014; Walmsley & McCormack, 2014).

Helpful communication strategies used by family

Four key strategies used by family members that were identified as helpful in facilitating communication were (1) scaffolding comprehension (Hyden & Samuelsson, 2019; Miller‐Ott; 2018); (2) initiating on behalf of the person with dementia (Kindell et al., 2014; Purves & Phinney, 2012); (3) using non‐verbal communication to compensate for word‐finding difficulties (Kindell et al., 2014; Schaber et al., 2016; Tipping & Whiteside, 2015; Walmsley & McCormack, 2014); and (4) communicating through activities (Hyden, 2014; Miron et al., 2019; Walmsley & McCormack, 2014).

Hyden and Samuelsson (2019) identified in their case study that the daughter and daughter‐in‐law of a lady with dementia would repeat their utterances and emphasize key words, such as names, with stress, when there was a misunderstanding in conversation, in addition using nouns in place of pronouns. These techniques appeared to support comprehension, mitigating the impact of hearing and working memory problems and allowed the conversation to continue. Family members also used clarifying questions with their relative with dementia to confirm understanding when their message was unclear, similar to those identified in previous work by Kindell et al. (2017).

Kindell et al. (2014) also recognized some of the strategies that family members found helpful to reduce the possibility of conversation breakdown, such as introducing conversations, in addition to using more comments rather than asking questions, to overcome difficulties with initiation. These techniques were also described in the findings of Purves and Phinney (2012). Purves and Phinney also described that family members recognized the importance of breaks in talking at times, and noted that when other more competent talkers within the conversation allowed more natural silence, this created more opportunities for her mother with dementia to spontaneously initiate interaction.

Several of the authors found that relatives became more receptive to their family members’ non‐verbal communication, when verbal communication was more challenging due to their dementia (Kindell et al., 2014; Schaber et al., 2016; Tipping & Whiteside, 2015; Walmsley & McCormack, 2014). Family members who viewed paralinguistic features of communication of the person with dementia, such as eye gaze, facial expression and vocalizations, as intentional, had more ‘in‐step communication’; meaning that the interaction flowed in a timely manner (Walmsley & McCormack, 2014). This appeared to result in interactions that were more reciprocal in nature, and more engaging and positive communication overall. Schaber et al. (2016) also noted that family members, including grandchildren, expressed love and intimacy using increasing non‐verbal approaches, such as hugging, kissing and holding the person, whilst using simple language to express their feelings, which helped to maintain connection, despite communication barriers.

Lastly, Miron et al. (2019) and Walmsley and McCormack (2014) identified how grandchildren introduced and used technology, such as electronic photo albums, to stimulate conversation with their grandparent with dementia. The grandchildren also reported they preferred engaging in activities together such as looking at photographs, baking, games or crafts to take the emphasis away from talking and facilitate opportunities for more spontaneous, natural communication. Hyden (2014) too found that collaboration of family members during meaningful activities can enhance communication with the relative living with dementia, through working in partnership to problem‐solve and complete a task, whilst sharing the ‘load’ of the conversation. These findings reiterate the way in which family members of people affected by dementia pursue new approaches to manage communicative challenges with their relative (Purves & Phinney, 2012).

Unhelpful communication strategies used by family

In contrast, several authors also suggest that family members unintentionally used strategies that are unhelpful, and can contribute to frustration, anxiety and reduced self‐esteem for the person with dementia.

Purves and Phinney (2012) found that some family members engaged in unusual conversation behaviours with negative effects, even though the intention was to encourage the person with dementia to communicate. An example identified was asking ‘test questions’, questions to which the answer is already known to the listener, to engage the person with dementia in conversation. However, asking ‘test questions’ often leads to conversation breakdown and the person with dementia disengaging when they are unable to recall the answer. Purves and Phinney also noted that some family members tend to overcompensate for their relative's difficulties, by directing the conversation towards topics that they know the person with dementia prefers, or by talking for them, which at times resulted in further frustration for the person with dementia. Miller‐Ott (2018) also found that adult children of people living with dementia frequently found themselves correcting their parent in conversation when they recalled information incorrectly. This too was reported by Tipping and Whiteside (2015), who identified that adult children repeatedly corrected their parent if they spoke in the language developed from birth that was potentially more accessible and comfortable for the person with dementia and not the shared language of the family, the concept described by Tipping and Whiteside as ‘language reversion’, although one participant did recognize that this strategy was no longer effective for her father with dementia, as it seemed to exacerbate frustration for both her and her father, causing their conversation to breakdown. Shakespeare (1998) would argue that this reiterates the notion that the communication difficulties that people with dementia experience are not solely due to cognitive deficits, but are as a result of collaborative communication difficulties, influenced by the behaviour and skills of conversation partners too.

Likewise, Miron et al. (2019) recorded similar conclusions in that despite their best intentions, grandchildren sometimes had a negative effect on their grandparent with dementia during interactions together, as a consequence of communication strategies they used. This was thought to be attributable to their concentration on their grandparent ‘getting things right’, as opposed to their grandparent's engagement and participation in the interaction in the moment, as they felt it a reflection on their own interactional competence if their grandparent was unable to recall information accurately or retrieve a word (Wicklund, 2008).

Prolonging an interaction for too long or expecting too much of the person with dementia in terms of their linguistic and cognitive abilities were also identified as unhelpful communication behaviours in this review (Purves & Phinney, 2012; Walmsley & McCormack, 2014). Some family members explicitly expressed a sense of frustration when the person with dementia appeared unable to use speech, for example, when becoming tired, and their verbal responses reduced, which in this case was interpreted by the family as a lack of interest. Unfortunately, some relatives implied that they no longer sought opportunities to engage with their family members with dementia, due to their word‐finding difficulties and perceived lack of motivation to communicate together. Family members highlighted that they were aware that the person with dementia was at risk of becoming socially isolated, secondary to their communication difficulties, but expressed that engaging them in interactions lead to annoyance that was potentially as harmful for their well‐being. These themes reinforce the need for communication training for families in knowing how to recognize and manage communication breakdown and promote successful participation in interactions with their relative with dementia.

Strategies used by people with dementia to maintain communication

Although there was limited information within this review from the perspective of the person with dementia, a few papers (Hyden & Samuelsson, 2019; Jones, 2015; Kindell et al., 2014; Walmsley & McCormack, 2014) did propose that people with dementia also develop their own coping strategies to maintain and demonstrate communicative competence during interactions with family. Jones (2015) highlighted how the lady with dementia in her case study would convey a sense of competence in answering her daughter's questions without in fact knowing the answer, as a technique to disguise her difficulties with recalling information correctly. Jones advises that people with dementia are often able to use their retained social awareness, for example, in turn‐taking and noticing social cues, and so they may be able to infer what an appropriate response could be to a relative's question.

Similarly, Hyden and Samuelsson (2019) observed that people with dementia developed face‐saving strategies, to avoid confrontation with family members, in order to maintain their relationships within their family system. The person with dementia in this particular study was noted to accept her daughter's repair, for example, when she recalled an event incorrectly, and did not argue her reality instead. The authors also noted that when the lady with dementia was unable to find a word, she would insert a similar word instead, either in terms of phonology or semantics, in an attempt to get the message across. Likewise, Walmsley and McCormack (2014) proposed that even in advanced stages of dementia, individuals use non‐verbal communication such as facial expression, body movements and touch to convey a message. The found that people with dementia appeared to have retained awareness of their family members, and communicated their relational connectedness through smiling, use of eyebrows and eye contact. These studies suggest that people with dementia not only maintain a level of conversational competence despite cognitive impairment, but that they are active participants in the interaction, and previous literature into the social proficiency of people with dementia would validate this theory (Hamilton, 1994; Muller & Wilson, 2008). Conversely, findings of Purves and Phinney (2012) would dispute this, as participants in one family expressed that their mother with dementia had little insight into the communication difficulties within their family system, suggesting that she continued to attempt to communicate, unaware of her impairments or the frustration of family members in trying to support her.

This emphasizes the heterogeneous nature of people affected by dementia, and the significance of understanding people as individuals, with unique lived experiences of the diagnosis (Cohen‐Mansfield & Jiska, 2000). Additionally, it is useful to consider that little information was given within many of the studies with regards to severity of the dementia for the participant or their relative with dementia, and so this may also account for differences in functioning, awareness and use of strategies.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this review was to explore how family systems living with dementia respond to and manage changes in communication, resulting from dementia. Family systems theory can offer a practical framework with which to understand the wider social context of the person with dementia, and perspectives, skills and needs of conversation partners in the family, in recognition that the communication and behaviour of a person with dementia can influence and be influenced by multiple family members (Bowen, 1978). This approach has the potential to support family‐centred practice, in planning and delivering interventions to support communication that are tailored to the needs of the person with dementia and individuals in their family, as well as the family as a whole system (Kokorelias et al., 2019).

In total, nine papers were included in this review, all having used qualitative approaches to understand communication amongst multiple family members. However, only one study (Purves & Phinney, 2012) explicitly used a family system approach, examining communication as a case study within two particular family systems, and overtly discussed the individual roles of each family member in terms of influencing or responding to communication, in addition to the collaborative efforts of the family system. The remaining studies had discussed communication between the person with dementia and at least two other family members, as opposed to within a dyad, but appeared to neglect the roles of individual family relationships in influencing communication, or made conclusions regarding interactions across multiple families, potentially diluting the complexity and intricacies of each family system. Findings from this review would suggest that applying a family systems approach to the investigation and analysis of communication in dementia is a relatively understudied area.

Although there appears to be limited research that uses a family systems approach to understanding family communication changes in dementia, this literature review has started to make links with regards to how a family, including different generations, may work together to maintain interactions. For example, having a ‘representative’ for the family, family members who work as a ‘mediator’, translating the communication of the person with dementia for others to understand and making use of an ‘interaction buffer’ as the more competent communicator. Given the importance of identifying facilitators and barriers to the communication of the person with dementia, in line with the WHO's ICF (WHO, 2001) framework, increased understanding of communication roles and skills within a wider family system may provide a more comprehensive appreciation of the ways in which a person with dementia interacts with key familial conversation partners. Importantly, application of this approach may support speech and language therapists to identify interventions that maximize the quality of family interactions together, acknowledging the impact of dementia on whole families as increasingly outlined in policy and strategy (NICE, 2018; Welsh Government, 2018).

Strengths and limitations

With regards to the strengths of this review, this work was carried out with the support and involvement of people living with dementia and their families within the University research steering group and also a support group for people with rarer dementias, particularly in relation to sense‐checking developing themes following analysis of the papers. For many years, it has been assumed that people with dementia lack insight into their condition and cannot provide informed consent required to engage in the research process (Dewing, 2002; Hellström et al., 2007). However, in the context of increased patient and public involvement (PPI) in both research and in healthcare settings, researchers are increasingly aware of the need to include people with dementia as active participants and co‐producers of research if we are to more accurately understand the needs of people with dementia and thus develop more effective interventions to improve quality of life (Allen et al., 2017; Bartlett & O'Connor, 2010). As other key stakeholders, consultation with speech and language therapists working in dementia care was also carried out to determine the usefulness of this research and potential applicability to clinical practice.

Although it can be argued that qualitative research can be particularly susceptible to bias (Galdas, 2017), efforts were made throughout the process of conducting the review to reduce potential bias in regard to the selection and interpretation of the data. Authors independently reviewed selected papers and engaged in critical discussion as a method of internal quality control. This served to increase interpretative rigour, by challenging authors’ assumptions and enhancing understanding regarding the data to ensure reflexivity.

In relation to the limitations of this work, the small number of papers included could be viewed as a limitation of the paper. Only nine papers met the inclusion criteria, due to the paucity of literature addressing the research question, which could potentially have an impact on the transferability of the data (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). However, as qualitative research is focused around detailed understanding of a concept as opposed to extent and generalization (Boddy, 2016), a small sample size may be considered appropriate within this context.

In terms of limitations within the data itself, it is pertinent to highlight that there was very little inclusion of people with dementia as active members of their family systems within each paper. Only four of the nine papers described people with dementia as engaging in reciprocal communication with their family members. Many of the studies included in this review sought opinions and experiences of family members, and a number of the studies observed the communication of people with dementia with their relatives and analysed their interactions. However, only one study (Purves & Phinney, 2012) directly explored the experiences of people with dementia in terms of communicating with their family.

Reduced recruitment of participants from minority groups could also be viewed as a limitation of this review. To the author's knowledge, there was no known inclusion of people with dementia and their families from LGBTQ+ community. It has been suggested that people within the LGBTQ+ community may not live within ‘traditional’ family systems, but a ‘family of choice’, comprising of partners and close friends (Concannon, 2009). Therefore, findings from this review may not necessarily be truly representative of the ways in which LGBTQ+ families with dementia experience and manage changes in communication. Similarly, the studies reviewed mostly recruited relatives of people living with late‐onset Alzheimer's disease. Given what is known about the more significant language difficulties in younger‐onset and frontotemporal dementias, this review may less accurately describe communication family systems affected by rarer dementias, as opposed those with more typical amnestic presentations.

Implications for clinical practice

Although only preliminary results, findings from this review represent the first step in revealing potential coping strategies and techniques that may be used within family systems when adapting to communication changes in dementia. Specific communication strategies thought to increase success of communication transactions were identified in this review, such as emphasizing key words with stress to aid understanding, using proper nouns in place of pronouns to aid working memory, and encouraging gesture to mitigate the impact of word‐finding difficulties. Practical techniques such as these are frequently advised by speech and language therapists in clinical practice to reduce the likelihood of communication breakdown, although the evidence base has previously lacked detail with regards to carers’ and families’ perceptions of efficacy of such strategies (Alsawy et al., 2017). Approaches such as collaborative storytelling, demonstrating intergenerational solidarity through reminiscence, instigating favourite conversation topics and modelling of positive communication from more confident conversation partners in the family system also appear to have positive effects on maintaining meaningful interactions together and strengthening familial relationships. Acceptance of non‐verbal communication by family members, such as facial expression, gesture and eye contact, as intentional attempts to interact also appeared to have a positive impact on enabling the family member with dementia to engage in a reciprocal interaction. These findings are significant for speech and language therapists working in this field, and may contribute to evidence‐based compensatory strategies and family‐centred approaches to interaction that may be advised to families to maximize communication with their relative with dementia. Findings from this review also reinforce the need for training of conversation partners of people with dementia, as recommended within the RCSLT's Position Paper for Dementia (RCSLT, 2014) to ensure that families feel skilled in meeting the communication needs of their family member with dementia and enabling the person to participate in interactions that are meaningful and reciprocal.

Future research directions

This review highlights an apparent gap in the literature in terms of examining communication in dementia from a family systems perspective. Furthermore, there is a clear need to include people with dementia as active conversation partners, within their own family system, within the field of communication research. There also appears to be a relative absence in the current literature towards the role of younger family members in maintaining communication with their family member with dementia. Given what is known about the value of intergenerational relationships, particularly for people with dementia in terms of well‐being and cognition (Gerritzen et a., 2019), future empirical investigations should address the current gap in knowledge regarding communication and intergenerational practice in dementia (Armstrong & McKechnie, 2009). In particular, future research should seek to examine the unique responsibilities of younger people, such as grandchildren, within an intergenerational family system, and how their roles work alongside that of parents and people with dementia to preserve family interactions. Furthermore, further research in this area may explore efficacy of communication techniques such as those discussed above, in terms of facilitating familial connections and maintaining relationships.

CONCLUSIONS