Abstract

Racial and ethnic disparities persist in access to the liver transplantation (LT) waiting list; however, there is limited knowledge about underlying system‐level factors that may be responsible for these disparities. Given the complex nature of LT candidate evaluation, a human factors and systems engineering approach may provide insights. We recruited participants from the LT teams (coordinators, advanced practice providers, physicians, social workers, dieticians, pharmacists, leadership) at two major LT centers. From December 2020 to July 2021, we performed ethnographic observations (participant–patient appointments, committee meetings) and semistructured interviews (N = 54 interviews, 49 observation hours). Based on findings from this multicenter, multimethod qualitative study combined with the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety 2.0 (a human factors and systems engineering model for health care), we created a conceptual framework describing how transplant work system characteristics and other external factors may improve equity in the LT evaluation process. Participant perceptions about listing disparities described external factors (e.g., structural racism, ambiguous national guidelines, national quality metrics) that permeate the LT evaluation process. Mechanisms identified included minimal transplant team diversity, implicit bias, and interpersonal racism. A lack of resources was a common theme, such as social workers, transportation assistance, non–English‐language materials, and time (e.g., more time for education for patients with health literacy concerns). Because of the minimal data collection or center feedback about disparities, participants felt uncomfortable with and unadaptable to unwanted outcomes, which perpetuate disparities. We proposed transplant center–level solutions (i.e., including but not limited to training of staff on health equity) to modifiable barriers in the clinical work system that could help patient navigation, reduce disparities, and improve access to care. Our findings call for an urgent need for transplant centers, national societies, and policy makers to focus efforts on improving equity (tailored, patient‐centered resources) using the science of human factors and systems engineering.

Abbreviations

- APP

advanced practice provider

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease 2019

- EHR

electronic health record

- FTE

full‐time equivalent

- HFE

human factors engineering

- LT

liver transplantation

- SDOH

social determinants of health

- SEIPS

Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety

- SIPAT

Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplant

INTRODUCTION

Liver transplantation (LT) is the only cure for advanced liver disease, yet racial and ethnic disparities, known to exist for decades, continue to impede access to care.[ 1 ] To receive an LT, patients proceed through a lengthy, sometimes opaque, process. LT centers assess each patient's appropriateness for transplant, culminating in a decision to list or not to list for LT. If listed, patients are prioritized based on disease severity; some will later be delisted for a variety of reasons, such as death or being too sick to survive transplant. Health disparities exist related to access to the waiting list,[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ] which have negative downstream effects. For example, when waitlist race/ethnicity distributions from 109 US transplant center waiting lists were compared with their donor service area, Black patients were underrepresented on 81% of the waiting lists, and Hispanic or Latino patients were underrepresented on 62%.[ 4 ] Tackling upstream LT listing barriers can improve access to LT downstream. Systematic and plausibly avoidable differences in LT listing adversely affecting socially disadvantaged groups[ 6 ] stem at least in part from social determinants of health (SDOH; e.g., income, employment, education, insurance) and structural racism.[ 7 , 8 ] Structural racism can be defined as the result of laws, rules, and practices sanctioned by the government and institutions and embedded in the economic system and societal norms.[ 9 ] LT evaluation may also be susceptible to structural racism, and these effects may be augmented because of its clinical, logistical, and/or ethical intricacies.

Understanding mechanisms to LT listing disparities has been difficult because of a paucity of data and the complex evaluation process. Most of the transplant community's knowledge about the burden related to health disparities comes from kidney transplantation[ 10 , 11 ] largely because data on patients on hemodialysis are in a national database. Therefore, pretransplant data from LT evaluation are not nationally available. Per hepatology society guidelines,[ 12 , 13 ] a standard workup involves a battery of blood work, imaging, and evaluations with several United Network for Organ Sharing–defined providers: a hepatologist, surgeon, clinical social worker, and dietician. The evaluation can range from a day to months based on the severity of disease, and certain comorbidities may necessitate additional testing. Throughout the evaluation, the patient, caregivers, and care professionals intermittently engage in person and with various technologies (e.g., electronic health record [EHR]) for information communication. Importantly, LT listing involves a transplant committee decision, which is complex because of the following: (1) a nationally regulated multidisciplinary team, (2) ethics of balancing donor organ stewardship with helping those in need of an LT,[ 14 ] and (3) the psychosocially diverse patient population.[ 15 , 16 ]

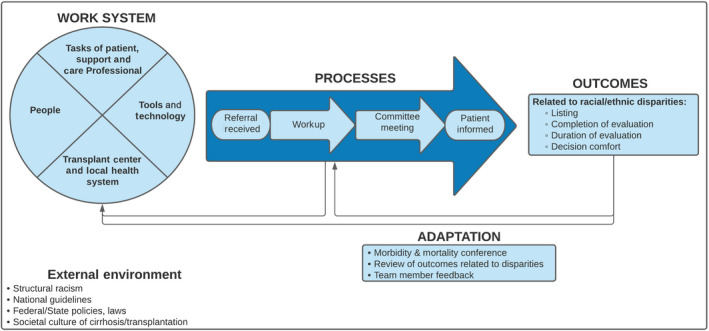

Given the complexities of the multistep and multidisciplinary LT evaluation process and mechanisms of disparities in listing, a systems engineering approach, specifically rooted in human factors engineering (HFE), may be useful. HFE experts systematically examine complex, high‐stake processes, such as the LT evaluation process; identify factors in the complex sociotechnical clinical work systems that affect process performance[ 17 ]; and develop human‐centered solutions to improve processes (i.e., redesigning LT evaluation processes to reduce inequities) and outcomes (e.g., high‐quality and highly equitable care).[ 17 ] For example, training care professionals to understand their biases is critical, but implicit bias education is only one approach with a limited impact[ 18 , 19 ] to addressing the underlying structural problems embedded in the larger work system. The Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model has been used to assess complex work systems and identify underlying problems and develop effective improvement directions in other areas of health care.[ 20 , 21 , 22 ] The main domains of the SEIPS 2.0 model are the following: (1) external environment, (2) work system (people, tasks, tools/technology, internal environment), (3) process, (4) outcomes, and (5) adaptation.[ 23 ] This framework applied to LT evaluation may provide a clarifying and systematic view of pathways leading to disparities in listing.

To characterize transplant team perceptions and attitudes about potential mechanisms in the LT evaluation process leading to racial and ethnic disparities in listing, we performed a comprehensive multicenter, multimethod (i.e., ethnographic observations, semistructured interviews) qualitative study using an HFE approach. Qualitative methods studies are useful for providing rich, in‐depth knowledge on a nuanced topic.[ 24 ] This study aimed to develop a conceptual framework specific to equity in LT listing through developing an understanding of the work of the transplant team during evaluation and possible mechanisms for inequity in listing. These insights could inform potential transplant center–focused solutions for improving access to the waiting list.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Research design

We conducted a qualitative study with ethnographic observations and semistructured interviews.[ 25 ] Ethnographic observations included (1) clinic appointments and (2) transplant committee meetings. The semistructured interviews assessed care professional descriptions and perceptions of the evaluation process and disparities.[ 25 ]

Setting

We conducted a multicenter study at the two transplant centers from December 2020 through July 2021. We chose the centers for the high transplant volume[ 26 ] and proximity of the two centers serving a diverse population[ 27 ] in Baltimore, Maryland. In 2019, each center had between 79 and 98 adult deceased donor LTs (6%–14% on Medicaid per Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network as of March 4, 2022), 15%–18.5% Black patients on the waiting list, and 3.8%–4% Hispanic or Latino patients on the waiting list.[ 28 ]

Sample population and recruitment

We used purposeful sampling to recruit LT experts via e‐mail: pretransplant/posttransplant coordinators, advanced practice providers (APPs), physicians, social workers, dieticians, pharmacists, and leadership. Inclusion criteria were being an LT team member during the study period. We performed observations consecutively until saturation was achieved in each participant type.[ 29 ]

Data collection methods

Ethnographic observations conducted by nontransplant team members and qualitatively trained investigators (A.T.S., C.N.S., V.S.J.). Direct observers recorded field notes on interactions among people, tasks, tools/technology, and organizational characteristics, particularly for aspects related to equity. We observed decision‐making through information gathering, discussions, different mental model sharing, and sensemaking. Observers created memos based on field notes. Each observation was 30–60 min.

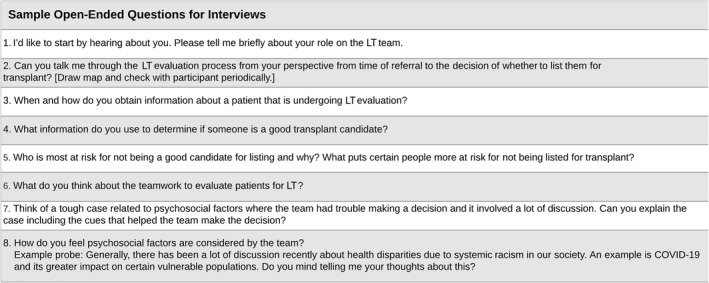

We developed a semistructured interview guide informed by HFE literature,[ 23 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ] including the SEIPS 2.0 model.[ 23 ] The SEIPS 2.0 model domains are the following: (1) external environment, (2) work system, (3) processes, (4) outcomes, and (5) adaptation. The “work system” domain has four components that complete the “processes”: people, tasks, tools and technology, and the internal environment; “work system” characteristics and interactions impact the quality of the “processes” and “outcomes”. The “adaptation” domain has feedback loops between “outcomes,” “processes,” and “work system.” We pilot tested and iteratively refined the interview guide with clinicians, qualitative researchers, social epidemiologists, and human factor engineers to test question interpretation and understanding. Interviews included open‐ended questions related to outlining the evaluation process, individual tasks, team decision making, and mechanisms for racial and ethnic listing disparities (Figure 1). We asked for participant demographics (transplant experience, gender, race, ethnicity). One researcher (A.T.S., physician researcher with training in HFE and health equity) conducted all semistructured interviews. Interviews were 1 h, audio‐ and video‐recorded, transcribed verbatim, and deidentified. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines[ 37 ] were used for this Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board–approved study (no. 00242367). The participants completed oral informed consent.

FIGURE 1.

Semistructured interview questions for care professionals about the LT evaluation process and potential mechanisms for racial and ethnic disparities in listing

Analysis

The research team analyzed the observational field notes and interview transcripts using thematic analysis with both inductive and deductive approaches.[ 38 ] The ethnographic observational memos were used to inform the codebook development and provide context for the interviews. First, investigators (A.T.S., C.N.S.) used inductive coding to descriptively categorize participants' responses to develop themes (e.g., “implicit bias,” “education,” “transportation”). The investigators coded initial interviews together to develop themes with retroactive revisions. When thematic saturation was reached (i.e., no new themes emerged), investigators finalized the inductive analysis–based code structure. Investigators independently coded the interviews using qualitative NVivo software (QSR, Version 10) and reconciled discrepancies in coding through consensus.[ 39 ] Then, using data matrices, investigators categorized the themes and corresponding text into higher order domains based on the SEIPS model (deductive approach).[ 23 ] Investigators determined the categorizations through consensus, and they used the data matrix to create a human factors and systems engineering–based conceptual framework for health equity. The research team (clinicians, health equity researchers, qualitative researchers, and a systems engineer) reviewed the conceptual framework for interpretability with no further changes needed.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Of the 103 transplant team members contacted (response rate: 71.8%, 74/103), 68 were consented for observation and/or semistructured interviews (six unavailable/not interested on follow‐up). We conducted ethnographic observations of (1) clinic appointments (N = 52; 27.5 h) and (2) committee meetings (N = 32; 21.5 h). The 54 semistructured interviews averaged 58.2 min. Participants had a median (IQR) of 8.5 years (IQR 4, 14 years) of LT experience, and 18.5% (n = 10) of participants had leadership/administrative roles (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of participants from two transplant centers who completed semistructured interviews about the LT evaluation process and potential mechanisms for listing disparities (N = 54)

| Characteristic | n (%) or median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Type of participant | |

| Leadership a | 10 (18.5) |

| APP | 4 (7.4) |

| Coordinator b | 13 (24.1) |

| Dietician/financial specialist/pharmacist | 8 (14.8) |

| Physician c | 22 (40.7) |

| Social worker | 6 (11.1) |

| Women | 40 (74.1) |

| Self‐reported race and ethnicity | |

| Non‐Hispanic or Latino White | 39 (72.2) |

| Non‐Hispanic or Latino Black | 7 (13.0) |

| Other d | 8 (14.8) |

| Experience, years | |

| Any transplant experience | 9.5 (5, 14.8) |

| LT experience | 8.5 (4, 14) |

Note: Center 1, N = 33; Center 2, N = 21.

Abbreviations: APP, advanced practice provider; IQR, interquartile range; LT, liver transplantation.

Not mutually exclusive to other types. Leadership includes administrative (e.g., directors) or supervisor (e.g., lead nurse) roles.

Coordinator: pre and posttransplant.

Physician includes hepatologist, surgeon, anesthesiologist, psychiatrist.

Other: Hispanic or Latino, Asian, and multiracial participants were combined because of the small numbers to protect identity.

Human factors and systems engineering–based conceptual framework for improving racial and ethnic disparities in LT waiting lists

The resulting conceptual framework describing improvement health equity in LT is given in Figure 2.[ 23 ] Components of the work system for LT evaluation are (1) transplant center and local health system characteristics, (2) people (e.g., patients, support, care professionals), (3) tasks of patient, support, and care professionals, and (4) tools and technology (Table 2). The LT evaluation process starts with receiving the referral, includes the workup and committee meeting, and ends with informing the patient of the decision (Figure 2). Observed and participant‐reported outcomes potentially susceptible to racial and ethnic disparities are listing decision, incomplete evaluation, and delay in evaluation. Some participants also described feeling “uncomfortable” or “struggling with” decisions that could lead to listing disparities. The next sections summarize conceptual framework elements and describe how the process may function differently for minority populations, which can lead to differential outcomes.

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual framework of a systems engineering approach to racial and ethnic disparities in listing for LT guided by qualitative data and from the SEIPS 2.0 model.[ 23 ] Elements were identified from semistructured interviews and ethnographic observations at two transplant centers.

TABLE 2.

Observed and participant‐defined elements of each work system component from a conceptual framework of a systems engineering approach to racial and ethnic disparities in listing for LT

| Work system component | Participant‐defined elements from LT evaluation |

|---|---|

| Transplant center and local health system |

|

| People a |

|

| Tasks of patients, support, and care professionals |

Patient/support:

Care professionals:

|

| Tools and technology |

|

Note: The conceptual framework was guided by the qualitative data and the SEIPS 2.0 model.[ 23 ] Elements were identified through ethnographic observations and semistructured interviews at two urban transplant centers.

Abbreviations: APP, advanced practice provider; EHR, electronic health record; LT, liver transplantation; SEIPS, Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety; SIPAT, Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplant.

In addition to job type as listed, this component also includes their characteristics (e.g., experience, training, beliefs, socioeconomic status, communication skills).

External environment

Two themes emerged from participants linking structural racism from the external environment to additional external environment factors closely related to LT patient evaluation (Figure 2). The first theme was “structural racism propagated through ambiguous listing guidelines.” Many participants explained that the psychosocial criteria in the national transplant society's LT candidacy guidelines are subjective, and vulnerable populations “struggle to meet” them (see “Process: Workup Phase” section) because of “systemic issues ingrained for so long and in every aspect of society” (Table 3). The second theme was “insurance‐related policies and national transplant metrics not aligned with equity.” Participants outlined that structural racism operates through SDOH (e.g., education, employment, geography, citizenship) to transplant center barriers with insurance policies because the patient is not insured or underinsured (e.g., no transportation assistance benefit or limited covered transplant centers). Participants explained differential access to insurance for minority populations is important because they cannot afford post‐LT medications and risk graft rejection. In addition, participants explained that the viability of a transplant program relies on successful national metrics that do not incorporate equity, so being “aggressive patient advocates” for patients with less resources could lead to lower scores on quality metrics.

TABLE 3.

Themes, representative quotations, and observations about potential mechanisms for racial and ethnic disparities in listing for LT organized based on a conceptual framework of a systems engineering approach to improving equity in liver transplant evaluation

| Theme | Representative quotes and observations |

|---|---|

| EXTERNAL ENVIRONMENT | |

| Structural racism propagated through ambiguous listing guidelines |

“It's [structural racism] been ingrained for so long and in every aspect of society it pervades everything. As much as we try and do an objective psychosocial, in quotes [uses hand quotes], assessment of a patient, the psychosocial metrics that we use, persons of color minority groups fall short of those metrics because of generations of racism … We can try and claim to be objective about things like ‘well, we are just looking at what resources they have’ and you cannot argue that that's not important posttransplant. You need resources to succeed posttransplant, so you can try and hide behind the guise that that's just being objective.” (Physician 0601) “Part of the reason that there are disadvantages due to their race is structural racism. … Some aspects of our transplant evaluation are subjective that transplant candidates of different racial backgrounds will struggle to meet and check off those boxes … specifically African American individuals, they struggled to get evaluated and they struggle to get listed.” (Physician 060) “It's all the stuff that underpins how people end up where they are … it is a little bit systemic racism, and it's hard for those people to dig out, and it's hard for them to garner the support. You do not really know the backstory right? They make be coming to eval alone because their significant other is on dialysis, and their child who would have come with them is working, and that's it. That's all the support they have. And their child who's working does not have the kind of job where he or she can say, listen, I need to go to my father's or my mother's eval because they'll get fired. It's a complex thing.” (Physician 0105) |

| Insurance‐related policies and national transplant metrics not aligned with equity |

“Because of education, because of lack of employment, and that will explain why they are not insured. That will set them up for the failure to be listed because they do not have insurance, or at least delay the process of being listed. … If you do not have insurance to have a liver transplant, it requires a lot of resources, liver transplant is almost half a million dollars … it is the structural setup that may predispose some people to have disparity. … Why do we not have universal health care?” (Coordinator 0309) “They [unauthorized immigrants] may be the best people in the world. They may have great jobs, but if they cannot get insurance, and they cannot afford the medication, we cannot transplant them because they will not be able to take care of the organ.” (Physician 0107) “We want physicians that are aggressive patient advocates. Wouldn't want it any other way, could not imagine being emotionally neutral towards a person who has come to you, put their lives in your hands, and said ‘You're my doctor. You'll take care of me.’ So that's fine. But there's another agenda in play for those at the selection committee meeting and that's that our program has to be successful and viable.” (Physician 0902) |

| PROCESS: WORK‐UP PHASE | |

| Transplant center and local health system | |

| Limited social worker resources |

“Psychosocial evaluation support are definitely some of the areas where I think we need more help‐more FTE's. I think our social workers are fantastic. There's just not enough of them. That is probably one of the biggest challenges for our patients. And if we do not have enough resources for them, sometimes we have to question‐are they unsuccessful because we did not have enough resources for them?” (Dietician/Financial/Pharmacist 0407) “They need more meetings, more time with social work. Social worker is just one person and they have to meet with so many people.” (Dietician/Financial/Pharmacist 0106) |

| Limited resources for non–English‐speaking patients |

“Our consents sometimes aren't translated to Spanish, and we have a lot of Spanish‐speaking patients or living donor questionnaire. I do not know of any living donor questionnaire that's in any other language but English. So I do think that even with an interpreter, the barrier definitely does not go away.” (Coordinator 0300) “We have letters that we can send to patients that are in Spanish. We do not have anything in any other language. … A goal of mine is to increase the number of Spanish letters that we have available to us to send to patients at any point of their time before transplant whether it's evaluation, like ‘Hey, we have not heard from you. Here's what you need to do. The orders are in enclosed.’” (Coordinator 0602) |

| People | |

| Patient with low socioeconomic status |

“So then there's a financial obligation that what happens when you are off of work for 6 to 8 weeks at least after transplant, maybe even longer depending on how you are doing. So that's an obstacle right there. They may not be able to afford to do that … especially if they are the breadwinner of the family. … They might not have any health insurance because of the type of work that they do.” (Social Worker 0205) “Socioeconomic disparities that cluster around people who are not White that impact their ability to access resources and attend to the issues that surround transplantation in the operative and postoperative period, which lead to significant obstacles and make the transplant unsuccessful. So, it may be that there are difficulties for these populations in coming to clinic frequently or having the understanding of aggressively seeking care when it might be more challenging to do so or to understand the reasons to do so.” (Social Worker 070) |

| Patient with low health literacy |

“I do feel as though we should be more understanding that they may just need more of an assistance, more help to even have the information. If you do not have that knowledge or you do not come from a background where that knowledge is available to you, it's all going to be a learning stepping‐stone.” (Dietician/Financial/Pharmacist 0106) “We're sort of giving them the tools and saying you need to go figure it out on your own and then come back if you still need a transplant.” (Advanced Practice Provider 0208) |

| Barriers attributed to where patient lives or transportation access |

“Can they afford gas and transportation to get to Baltimore. … We transplant people as far as Garrett County. You know it's a hardship. A lot of them are elderly or older folks, so they do not have the extra funds to drive the two and a half hours here and pay to park or spend the night. So that's a big hardship on them as well.” (Coordinator 0402) “They [minority populations] deal with different problems and definitely all related to socioeconomical disparities and exposure to those risk factors in their community. For example, if they were drinking, it's not uncommon to see that other family and close friends are doing that too and kind of more difficult to find the support that is not going to be doing that.” (Physician 0408) “A barrier is transportation and making it to appointments … but we do not have resources to assist with that.” (Social Worker 0103) |

| Support system/caregiver(s) with low socioeconomic status |

“Who they identify as primary support I get their name and number and see if the primary support is working full time and if they are able to take leave. … A lot of people in the city, they do not have that [support]. The parents are barely surviving parents … so they are not going to be a part of their transplant process.” (Social Worker 0103) “The husband has never been in the hospital to visit with her. Always working, working, working behind the wheel in his truck. I understand. He wants to keep the insurance up and running. And if he does not work full time, they might just take that insurance away from him.” (Physician 0405) |

| Support system/caregiver(s) with low health literacy |

“Some patients are encephalopathic … having a person like a caregiver, a designated person who is health literate for them when they cannot be for themselves.” (Coordinator 0605) “If a family member or support person is asked, ‘Are you willing? Are you going to be available to help them as they recuperate with getting to the labs, getting to clinic?’ They're going to say yes because they do not want to feel like they are hindering a person's life if they say no. … They may think that's something they can do, but when they are actually faced with the reality of everything it involves, it may be too much for them.” (Coordinator 01000) |

| Unreliable transportation from support system/caregiver(s) |

“I've had patients who I need them to get a cath, and they are like ‘Well I do not have anybody to take me because everyone I know works.’ So they would need that person to take off work to drive them there.” (Coordinator 0300) “A lot of folks do not drive or do not have a car and so if they do not have that reliable caretaker who can actually bring them places and bring them to lab work and bring them to physical therapy and things like that. It's not just somebody in the home to help them with their medications and their meals. It's somebody who can actually get through the process successfully.” (Advanced Practice Provider 0502) |

| Tasks of patient, caregiver(s), and providers | |

| Variable patient engagement in the complex process |

“They [patients] are overwhelmed, and there's so many appointments. Because after you have your evaluation, then you are getting all this medical testing done, all this blood work done. You're just trying to tick those things off your list.” (Social Worker 0204) “One of the things I also talk to them in clinic about is I do not want them coming in here thinking that they are in the center, and there's a circle of people around them, and that's their team, and they just have to do whatever the people around them told them to do. I told them that they need to view themselves as part of a circle, and they are an equal team member. So, I have responsibility to them. They have a responsibility to me, and to the hepatologist, and to whoever else is part of the team.” (Coordinator 0506) [In our observations, conversations with and about patients from minority populations involved SDOH related to difficulties demonstrating patient engagement.] |

| Barriers to building trust in the patient–provider relationship |

“There needs to be a little bit more diversity … if I was a patient, I would not think that they would know how to relate to what I'm going through, or what I've been through, to really look at me as a person first.” (Dietician/Financial/Pharmacist 0509) “You also have a patient population coming in who can be slightly apprehensive of the process and used to sometimes being jerked around. And so it makes for some distrust in the system and just trying to get through that can be very challenging.” (Physician 0607) |

| Adaptability required by providers during assessments and education of patients |

“Our role as coordinators and social workers is: Let me educate you on why this is important.” (Coordinator 0506) “As I'm interviewing a patient, it's important for me to understand their insight into their disease, and whether or not they have continued to drink, despite being told they had alcoholic liver disease, or despite developing decompensated cirrhosis. So sort of having a timeline of how things have gone. At least having some clue allows me to sort of gauge the patient.” (Physician 0307) [Observations demonstrated that patients from minority populations, because of SDOH, may need more time to describe their insight or understand educational information, but providers were not always able to adapt their communication or delivery.] |

| Tools and technology | |

| Reliance on information propagated through EHR |

“There's documentation in the chart for the past year or so that patient has been told multiple times that she needs to stop drinking.” (Physician 0405) [We observed these descriptions were not always accurate.] “Other people gathered and their interpretation of the information that they gathered. Same outside of our system, information that's been put into [EHR] by other providers, maybe looking at the patient through a different lens.” (Social Worker 0204) |

| Limited access to technology inhibits communication |

“We do have the iPad translators here, which worked really well to help translate what we are saying and medical terminology to their language. However, sometimes the iPads aren't always in the patient's room … so you do have the resources, it's just sometimes I've seen it's limited.” (Dietician/Financial/Pharmacist 0303) “Unless someone comes with a cell phone and availability to reach us, then it's going to be very challenging.” (Physician 0503) |

| PROCESS: COMMITTEE MEETING PHASE | |

| People | |

| Limited transplant team diversity |

“We all advocate for people who remind us of ourselves, and there's just not a lot of African American faces in the transplant community.” (Physician 0607) “The representation at the table for the decisions is made by a group that is not only white men, so that is a step. … It is beneficial to our team to have multiple voices at the table of different perspectives.” (Physician 0902) |

| Nonstandardized use of social worker in psychosocial assessment |

“A lot of times some of the physicians give a lot of the psychosocial stuff or maybe that should just be left to the social worker who did the full psychosocial evaluation before it kind of gets little pieces of it sprinkled here and there—before the social worker kind of gives their input” (Coordinator 0304) “I think it's pretty good because usually the social workers present their objective assessment of the patients, leave out all those sort of subjective minor details. So things that matter the most to getting listed for liver transplant are, whether there's social support, whether there's a post‐op care plan, whether if—especially in like substance use disorder cases—whether they have remained sober, whether they have enrolled in treatment programs and those are all sort of yes or no questions that can be answered.” (Physician 050) [We observed that the social worker's psychosocial evaluation was sometimes less influential on the final decision when another provider knew the patient for a longer time.] |

| Tasks of care providers | |

| Subjectivity and inconsistency in decision making |

“Sometimes they are [surgeon] just like ‘Oh yeah we could do the surgery, but what do you think medically and socially?’ And I do think sometimes things get emotional and non‐objective and kind of get lost, and you can see that the biggest variation is in social approval.” (Physician 0803) “Social work will say ‘Not a good candidate.’ But then you get back to the surgeons, and they'll be like, ‘Oh, but this lady has two small children at home. We need to save her for her children.’ And I do not know if that's what we should be basing our decisions off.” (Dietician/Financial/Pharmacist 0801) “If you are conveying information that's very subjective about a patient you have to be careful about the way you say it to not kind of skew people's thinking about the patient.” (Coordinator 0304) |

| Implicit bias and personally mediated racism |

“It's complicated and the reasons why these disparities exist and access for minority populations or populations that are Latinx or African American community to transplant are complicated is definitely on the one hand probably racism or stereotyping that occurs by providers and judgments based on skin color or population classification that occurs.” (Social Worker 070) “African American patient compared to a Caucasian patient—I do sort of observe a pattern in which there's more of a barrier to overcome. They almost have to work harder to prove to the whole team that they are going to be able to take on this responsibility and that they have the appropriate support in order to do that. I feel like we are maybe less strict in our evaluation for certain groups, for people that seem like they have it together.” (Physician 0802) “We can do a little bit better before saying that some people are just not a good candidate, or they are just not going to follow up, or they are just going to go back to using whatever they were using before.…I do want to be my patient's advocate regardless of their race or color or gender.” (Physician 050) “We have a very unforgiving system for people without privilege and people with privilege have second, third, fourth, fifth chances. People without privilege, you do not even sometimes get a chance. That's my definition of privilege, people that get endless second chances.” (Physician 0105) |

| ADAPTATION | |

| Limited review or awareness of transplant center outcomes related to equity |

“I do not really see that [listing disparities]. I feel like we are very fair at who we list and transplant. It's really about their medical and social aspects. There's a lot of Caucasian people that also have a lot of psychosocial issues, so we, I think, treat them very equally.” (Coordinator 080) “I do not think it affects it at all. I do not even know what the patient looks like. We do not ask what their race is.” (Dietician/Financial/Pharmacist 0808) |

| Limited team member feedback |

“I think that the teamwork can be sort of a semidysfunctional family. We've known each other for years … so we are very okay to speak up our minds.” (Physician 0503) “I would not say that it's [feedback] in any structured way. I would say that if somebody had feedback to give, it would be that person being brave enough to say it. And I would not even know who to direct that to, at what forum to express that. The selection meeting is not a comfortable place to do that.” (Coordinator 0602) |

| Unclear transplant center role/ability to address disparities |

“There's a different, there's a definite kind of weeding out process I feel that happens even before transplant [team] gets involved.” (Physician 0100) “It's [listing disparity] so multifactor. Every answer is going to be too naïve. It's so systemic. Just trying to solve it as a very center‐based level is not even enough. It's also center dependent and what is your goal as a transplant center … to help everybody … it would be a nice thought, but I'm not sure we have everything in place to actually do it.” (Physician 040) “I do not know the answer, but I think that we need to do better … and see where patients get lost in this process and how we can make it smoother, make it more objective.” (Physician 060) |

Note: The conceptual framework was guided by the qualitative data and from the SEIPS 2.0 model.[ 23 ] Themes were identified through semistructured interviews and ethnographic observations (noted in italics and in brackets) at two urban transplant centers.

Abbreviations: EHR, electronic health record; FTE, full time equivalent; LT, liver transplantation; SDOH, social determinants of health; SEIPS, Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety.

Process: Workup phase

Transplant center and local health system in the workup phase

With respect to the workup phase of the LT evaluation process, participants identified two themes related to how the transplant center and local health system component of the work system may lead to inequitable outcomes: limited social worker resources and limited resources for non–English‐speaking patients. Many participants described how more social workers and resources would allow for necessary time and assistance with certain patients, such as those with transportation barriers (Table 3). In addition, participants outlined the importance of non–English‐speaking patients having readily available consent forms, letters, and questionnaires.

People in the workup phase

Participants identified the following three workup‐related themes regarding people in the work system that, through SDOH, play a role in racial and ethnic listing disparities: (1) patients with low socioeconomic status, (2) patients with low health literacy, and (3) barriers attributed to where the patient lives or transportation access. Participants explained how the effects of structural racism, such as differences in income and access to jobs and education, impact their access to resources for transplantation (Table 3). Participants described how education was linked to health literacy, and health literacy was critical to understanding how to complete the workup and use the tools given to them by the providers. Also, because of the importance of place and high volume of follow‐up visits, participants found that a patient's neighborhood/community and transportation access were barriers (e.g., neighborhood safety and access to car or gas/parking money). Paralleling these patient themes, participants also explained the effects of these SDOH for caregivers (Table 3). Specifically, participants recognized that minority populations have support systems that are “barely surviving” and may be unable to provide financial support or to demonstrate social support (e.g., leave work to be at the patient's appointments/hospital bedside). Participants explained that patients with encephalopathy or frailty benefit from having a caregiver with good health literacy and no transportation/geographic barriers, but some may be limited because of the SDOH as described previously.

Tasks of patient, caregiver(s), and care professionals in the workup phase

Participants described the following three themes in the workup phase related to tasks that may be on the pathway to listing disparities: (1) variable patient engagement in the complex process, (2) barriers to building trust in the patient–provider relationship, (3) adaptability required by providers during assessments and education of patients. First, participants reflected on patients/families feeling overwhelmed by the many tasks expected of them (Table 2). To overcome this task burden, some participants emphasized the importance of patient engagement. In our observations, conversations with and about patients from minority populations involved SDOH related to difficulties demonstrating patient engagement (Table 3). Second, participants described a lack of diversity in providers may lead to patients feeling the providers cannot relate to them. Participants noted that provider diversity is especially important for those where there is “some distrust in the system” because of personal interactions or historical events related to race and the health system. Lastly, participants described how providers gather information from patients to “understand their insight into their disease” and educate about transplant. Observations demonstrated that patients from minority populations, because of SDOH, may need more time to describe their insight or understand educational information, but providers were not always able to adapt their communication or delivery.

Tools and technology in the workup phase

The two themes related to the work system component tools and technology in the workup phase were reliance on information propagated through the EHR and limited access to technology inhibits communication. From participant interviews and observations, the transplant team uses EHR documentation by other providers (including outside records) and that information may include inaccuracies, inconsistencies, or implicit biases (Table 3). In addition, participants explained limited access to technology, such as virtual interpreters and cell phones, are barriers for equitable evaluation.

Process: Committee meeting phase

People in the committee meeting phase

Participants identified the two themes of limited transplant team diversity and nonstandardized use of social worker in psychosocial assessment as potential mechanisms for racially/ethnically based differentials in listing. Participants described how a homogeneous transplant team lacks “multiple voices at the table of different perspectives,” which could lead to inequitable listing decisions (Table 3). In addition, although many participants expressed the social worker opinion is “probably the most prized, and most valued, because they're the professional expert on the matter,” some explained other team members' opinions (e.g., surgeon, hepatologist) are sometimes prioritized. Congruent with this, we observed that the social worker's psychosocial evaluation was sometimes less influential on the final decision when another provider knew the patient for a longer time.

Tasks of providers in the committee meeting phase

The two themes about tasks in the committee meeting phase that may result in listing disparities were subjectivity and inconsistency in decision making and implicit bias and personally mediated racism in decision making. Participants reflected that sometimes emotionally based discussions related to the patient's likeability or “who's advocating for the patient” can lead to deviation from objective and consistent decision making (Table 3). We observed tangential discussions and side comments (e.g., “He's a good guy”) reflecting this subjectivity. The closely related theme “implicit bias and personally mediated racism in decision making” stemmed from participants noting that care professionals may not know their own implicit biases, which may impact committee meeting discussions. Participants outlined biases that may lead to personally mediated racism (defined as differential actions toward others based on race/ethnicity), [40 ] where the transplant team may raise concerns about substance abuse or follow‐up in minority patients and not be as supportive toward their candidacy. Some described LT evaluation as an “unforgiving system,” and minority populations sometimes may “work harder to prove to the whole team” that they meet the psychosocial requirements.

Adaptation

The three themes about adaptation related to listing disparities were (1) limited review or awareness of transplant center outcomes related to equity, (2) limited team member feedback, and (3) unclear transplant center role/ability to address disparities. Because most participants identified morbidity and mortality conference as the only form of review of outcomes without any infrastructure for systematic reporting, there was a range of participant awareness about disparities in listing; some saw issues, whereas others did not. One participant stated, “I don't think it affects it [listing] at all. I don't even know what the patient looks like. We don't ask what their race is” (Table 3). Another opportunity for adaptation in the process that participants described was team member feedback. We observed instances in committee meeting where team members spoke up about someone's potentially biased statements. However, participants also described a hierarchy and lack of structured feedback that may inhibit constructive criticism. Finally, although some participants felt that the transplant center's role in addressing listing inequities was unclear because of overshadowing preexisting issues (e.g., referral patterns, structural racism), others felt it was the transplant centers duty to “do better … and see where patients get lost in this process.” Table 4 summarizes the themes across the conceptual framework.

TABLE 4.

Summary table of themes about potential mechanisms for racial and ethnic inequities in liver transplant evaluation organized based on a conceptual framework of a systems engineering approach to improving equity in liver transplant evaluation

| External environment |

|

| Process |

|

Transplant center and local health system

People

Tasks of patient, support, and care professionals

Tools and technology

|

| Adaptation |

|

Note: The conceptual framework was guided by the qualitative data and from the SEIPS 2.0 model.[ 23 ] Themes were identified through semistructured interviews and ethnographic observations at two urban transplant centers.

Abbreviations: C, committee meeting phase of process; EHR, electronic health record; LT, liver transplantation; SEIPS, Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety; W, workup phase of process.

DISCUSSION

Study conclusions

In this multicenter qualitative study, transplant team perceptions and investigator observations uncovered mechanisms that may generate racial and ethnic disparities in LT listing. Transplant team members perceived decisions about listing were influenced by external factors (e.g., structural racism, ambiguous guidelines, national quality metrics) that permeate the LT evaluation process (workup and committee meeting phases) through various components of the work system, such as the transplant center/local health system, people (patients, caregivers, providers), tasks, and tools. Additional mechanisms included implicit bias or interpersonal racism at the time of decisions and structural barriers related to limited transplant center resources or lack of diversity in the transplant team. Furthermore, because the data related to inequitable outcomes were not specifically collected or reported back to the team, adaptation to address unwanted outcomes was limited, perpetuating disparities.

Although Volk et al. described decision making behind LT listing qualitatively,[ 15 ] we have expanded on this to provide a human factors and systems engineering framework that also considers health equity and provides guidance for how to improve redesign clinical work systems to improve LT evaluation and outcomes. By developing interventions that target the transplant center and modifiable patient‐level barriers along the LT evaluation process, we can redesign work systems and processes to reduce disparities and improve care (Table 5). This systems engineering–based perspective to shift from patient‐level barriers (e.g., inadequate health literacy of patient) to work systems–level understandings and solutions aligns with prior literature in transplant populations.[ 41 , 42 , 43 ] For example, labeling a patient with the risk factor of being a non–English‐speaking patient puts the burden on the patient to overcome inequities. A system solution may be consistently having translated patient education materials. Our findings demonstrate the importance of solutions from an interdisciplinary design with input from care professionals, patients, human factor engineers, and health equity experts. Furthermore, our findings described that transplant centers balance national quality metrics (waitlist survival, access to transplant, and posttransplant survival) with their desire to help patients with a higher risk profile from psychosocial barriers.[ 26 ] Transplant center–level solutions in Table 5 could be incentivized through expanding quality metrics about equity. Because tackling every solution at once would be onerous, they should be prioritized by each transplant center based on their patients and institutional environment. After presenting these findings to the transplant teams, both of the participating sites have already initiated interventions, such as translating consents and creating culturally sensitive and multilingual patient education videos. The goal of health equity involves a customizable approach to tools and programs based on needs.

TABLE 5.

Modifiable barriers in liver transplant evaluation at the patient and transplant‐center levels and potential transplant center solutions that may mitigate racial and ethnic disparities in listing

| Modifiable barrier | Potential transplant center solution |

|---|---|

| Transplant center–level barriers | |

| Limited review or awareness of transplant center outcomes related to equity |

|

| Unclear transplant center role/ability to address disparities |

|

| Subjectivity and inconsistency in decision making |

|

| Implicit bias and personally mediated racism |

|

| Limited social worker resources (patient‐level barrier examples: no transportation, local psychologist) |

|

| Limited resources for non–English‐speaking patients (patient‐level barrier example: non–English‐speaking patients) |

|

| Patient‐level barriers | |

| Patients with low health literacy |

|

| Barriers attributed to where patient lives or transportation access |

|

| Support system/caregiver(s) with low socioeconomic status or health literacy |

|

Participants identified a controversy among transplant team perspectives regarding the role or ability of the transplant center to alleviate inequities in LT listing. One side argued that mechanisms to barriers in access to the waiting list seem insurmountable (e.g., structural racism) or are outside their control (e.g., prereferral), which is similar to literature about delayed diagnosis/treatment and inequitable referral patterns.[ 1 , 44 , 45 ] Although it is true that transplant centers themselves may be ill equipped to directly change society at large, transplant centers can design health care delivery to help patients respond and navigate the SDOH‐related barriers. Our framework builds on the current practice of individual‐focused implicit bias training[ 46 ] and incorporates a systems approach at various transplant center and process points. By using the SEIPS model from HFE to assess mechanisms for disparities, we leveraged inherent aspects from the social–ecological model[ 47 , 48 ]; this is a common model used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health to understand health equity.[ 49 , 50 ] The SEIPS model incorporates the various levels from the social–ecological model (e.g., patient, family, health system, society) as parts of the work system and external environment. In addition, the underpinnings of the SEIPS model lies within the sociotechnical systems theory,[ 51 , 52 , 53 ] hence this model guides us about understanding and improving the interactions between the social aspects (e.g., people) and the technical aspects (e.g., tools/technology, task design, internal organizational characteristics) in a work system (e.g., transplant center); furthermore, it situates characteristics of these social and technical components in a process with outcomes and feedback loops. Thus, we were able to organize participant perceptions in our LT‐specific SEIPS conceptual framework and identify feasible strategies for the transplant center to play an active role in prioritizing and confronting inequities.

Our findings demonstrated that participants perceive that the ambiguity of the psychosocial‐related contraindications to LT in the current transplant society guidelines[ 12 ] is a potential mechanism for racial and ethnic disparities in listing. These contraindications are (1) ongoing alcohol or illicit substance abuse, (2) persistent noncompliance, and (3) lack of adequate social support. Currently, the literature is controversial about the timing and related outcomes of “ongoing” substance use.[ 54 ] In addition, evidence of causality is sparse, and practice is variable in the definition of “persistent” noncompliance and “adequate” social support.[ 55 , 56 ] As seen in our findings, social support that is nontraditional (e.g., not a spouse/parent) or working to afford medical bills may not be viewed by the team as adequate, and compliance may be questioned. One potential intervention may be transplant teams internally agreeing on precise, standardized assessments for these ambiguous contraindications. Applying these similarly across all populations may improve equitable access to the waiting list.

Study limitations

Although qualitative studies have limited generalizability, this study has good transferability, a core criteria for rigorous qualitative work.[ 57 ] Prior work has demonstrated similarity in LT evaluation and decision making between multiple centers,[ 15 ] so our large‐size, high response rate, and multicenter component should allow for transplant centers/providers to relate to at least some of the mechanisms and solutions for listing disparities. Importantly, this study was only with transplant team care professionals, not patients, so these findings may not match patient‐reported experiences. Although the literature evaluating Black patients undergoing kidney transplant evaluation demonstrated some similar findings, such as patients having medical mistrust, wanting transplant center support, and valuing education about the process, patient interviews added insights about the importance of care professional attitudes and an understanding of certain provider roles.[ 58 , 59 ] Qualitative research including LT patient experience during evaluation is needed. Although some participants may be biased in their recollection of events, our parallel ethnographic observations allowed us to see inconsistencies between what was described and the actuality. The juxtaposition of these methods homed in on a single step of the LT process, evaluation, and provided a rich understanding of the nuances and perspectives in all aspects of the process.[ 25 ] Without having such an in‐depth understanding, solutions developed in complex sociotechnical work systems, such as a transplant center, may have unintended negative consequences.[ 60 ]

CONCLUSION

In summary, the mechanisms for racial and ethnic disparities in LT listing are rooted in both external factors as well as the internal process composed of complex tasks undertaken by patients, caregivers, care professionals, and the transplant center. Our multimethod qualitative study identified barriers at the patient level (e.g., health literacy, transportation, and social support limitations) and transplant center level (e.g., transplant team diversity, resources for non–English‐speaking patients) that can be prioritized by transplant centers to tackle disparities. We have demonstrated the use of a human factors and systems engineering approach to tease apart problematic aspects of a process from an equity perspective. Other fields with complex work systems for diagnostic/treatment decisions (e.g., oncology tumor board) may find this applicable. This work is a call for transplant centers, national societies, and policy makers to shift from a lens of equality (same resources for all) to equity (tailored, patient‐centered resources) for our diverse population of LT patients using a human factors and systems engineering approach.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Scott Levin owns stock in Stocastic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate Haneefa Saleem's assistance in the early qualitative research guidance. This work was supported by Grant K23DK115908 (Jacqueline Garonzik‐Wang) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Grant K24AI144954 (Dorry L. Segev) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Grant K01HL145320 (John W. Jackson) from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, Grant K01HS024600 (Tanjala S. Purnell) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. This work was also supported by the Stetler Foundation (Alexandra T. Strauss). The funders had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the article or the decision to submit for publication. This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration Contract HHSH250‐2019‐00001C. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government.

Strauss AT, Sidoti CN, Purnell TS, Sung HC, Jackson JW, Levin S, et al. Multicenter study of racial and ethnic inequities in liver transplantation evaluation: Understanding mechanisms and identifying solutions. Liver Transpl. 2022;28:1841–1856. 10.1002/lt.26532

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are not publicly available because of privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nephew LD, Serper M. Racial, gender, and socioeconomic disparities in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2021;25:900–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kemmer N, Alsina A, Neff GW. Social determinants of orthotopic liver transplantation candidacy: role of patient‐related factors. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:3769–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mathur AK, Ashby VB, Fuller DS, Zhang M, Merion RM, Leichtman A, et al. Variation in access to the liver transplant waiting list in the United States. Transplantation. 2014;98:94–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Warren C, Carpenter AM, Neal D, Andreoni K, Sarosi G, Zarrinpar A. Racial disparity in liver transplantation listing. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;232:526–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jesse MT, Abouljoud M, Goldstein ED, Rebhan N, Ho CX, Macaulay T, et al. Racial disparities in patient selection for liver transplantation: an ongoing challenge. Clin Transplant. 2019;33:e13714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braveman PA, Kumanyika S, Fielding J, LaVeist T, Borrell LN, Manderscheid R, et al. Health disparities and health equity: the issue is justice. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(Suppl 1):S149–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dougherty GB, Golden SH, Gross AL, Colantuoni E, Dean LT. Measuring structural racism and its association with BMI. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59:530–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Purnell TS, Simpson DC, Callender CO, Boulware LE. Dismantling structural racism as a root cause of racial disparities in COVID‐19 and transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:2327–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works–racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:768–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Purnell TS, Bae S, Luo X, Johnson M, Crews DC, Cooper LA, et al. National trends in the association of race and ethnicity with predialysis nephrology care in the United States from 2005 to 2015. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2015003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rodríguez PS, Szempruch KR, Strassle PD, Gerber DA, Desai CS. Potential to mitigate disparities in access to kidney transplant in the hispanic/latino population with a specialized clinic: single center study representing single state data. Transplant Proc. 2021;53:1798–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, Brown R Jr, Fallon M. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology. 2014;59:1144–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu . EASL clinical practice guidelines: liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2016;64:433–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Solga SF, Serper M, Young RA, Forde KA. Transplantation for alcoholic hepatitis: are we achieving justice and utility? Hepatology. 2019;69:1798–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Volk ML, Biggins SW, Huang MA, Argo CK, Fontana RJ, Anspach RR. Decision making in liver transplant selection committees: a multicenter study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:503–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Volk ML, Lok ASF, Ubel PA, Vijan S. Beyond utilitarianism: a method for analyzing competing ethical principles in a decision analysis of liver transplantation. Med Decis Making. 2008;28:763–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carayon P. The balance theory and the work system model … twenty years later. Int J Hum Comput Interact. 2009;25:313–27. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pritlove C, Juando‐Prats C, Ala‐Leppilampi K, Parsons JA. The good, the bad, and the ugly of implicit bias. Lancet. 2019;393:502–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bezrukova K, Spell CS, Perry JL, Jehn KA. A meta‐analytical integration of over 40 years of research on diversity training evaluation. Psychol Bull. 2016;142:1227–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holdsworth LM, Kling SMR, Smith M, Safaeinili N, Shieh L, Vilendrer S, et al. Predicting and responding to clinical deterioration in hospitalized patients by using artificial intelligence: protocol for a mixed methods, stepped wedge study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021;10:e27532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Danesh MK, Garosi E, Mazloumi A, Najafi S. Identifying factors influencing cardiac care nurses' work ability within the framework of the SEIPS model. Work. 2020;66:569–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Engineering . Building a better delivery system: a new engineering/health care partnership. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holden RJ, Carayon P, Gurses AP, Hoonakker P, Hundt AS, Ozok AA, et al. SEIPS 2.0: a human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics. 2013;56:1669–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mack N, Woodsong C, Macqueen K, Guest G, Namey E. Qualitative research methods: a data collector's filed guide. Research Triangle Park, NC: Family Health International; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bernard RH. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. New York, Rowman Altamira; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Find and compare transplant programs. Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). [cited 2020 Oct 28]. Available from: https://www.srtr.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 27. United States Census Bureau . QuickFacts: United States; 2020. [cited 2021 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US [Google Scholar]

- 28. Transplant Centers . [cited 2021 Sep 19]. Available from: https://www.srtr.org/transplant‐centers/?organ=liver&recipientType=adult&query=

- 29. Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hutchins E. Distributed cognition. International Encyclopedia of the Social; 2000. Available from: https://arl.human.cornell.edu/linked%20docs/Hutchins_Distributed_Cognition.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gurses AP, Xiao Y, Gorman P, Hazlehurst B, Bochicchio G, Vaidya V, et al. A distributed cognition approach to understanding information transfer in mission critical domains. Proc Hum Fact Ergon Soc Annu Meet. 2006;50:924–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lipshitz R, Klein G, Orasanu J, Salas E. Taking stock of naturalistic decision making. J Behav Decis Mak. 2001;14:331–52. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cooke NJ, Gorman JC, Winner JL. Team cognition. Handb Appl Cognit. 2007;2:239–68. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Salas E, Cooke NJ, Rosen MA. On teams, teamwork, and team performance: discoveries and developments. Hum Factors. 2008;50:540–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Klein G. Expert intuition and naturalistic decision making. Handbook of intuition research. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Salomon G. No distribution without individuals' cognition: a dynamic interactional view. In: Salomon G, Perkins D, editors. Distributed cognitions: Psychological and educational considerations. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1993. p. 111–38. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Miles MB, Michael HA. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, Olson K, Spiers J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2002;1:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener's tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1212–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dore‐Stites D, Lopez MJ, Magee JC, Bucuvalas J, Campbell K, Shieck V, et al. Health literacy and its association with adherence in pediatric liver transplant recipients and their parents. Pediatr Transplant. 2020;24:e13726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Maroney K, Curtis LM, Opsasnick L, Smith KD, Eifler MR, Moore A, et al. eHealth literacy and web‐based patient portal usage among kidney and liver transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2021;35:e14184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cooper LA, Beach MC, Johnson RL, Inui TS. Delving below the surface. Understanding how race and ethnicity influence relationships in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 1):S21–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kanwal F, Hernaez R, Liu Y, Taylor TJ, Rana A, Kramer JR, et al. Factors associated with access to and receipt of liver transplantation in veterans with end‐stage liver disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:949–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nguyen GC, Thuluvath PJ. Racial disparity in liver disease: biological, cultural, or socioeconomic factors. Hepatology. 2008;47:1058–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ricks TN, Abbyad C, Polinard E. Undoing racism and mitigating bias among healthcare professionals: lessons learned during a systematic review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;3:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kilanowski JF. Breadth of the socio‐ecological model. J Agromedicine. 2017;22:295–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:668–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. The social‐ecological model: a framework for prevention. 2021. [cited 2021 Dec 31]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social‐ecologicalmodel.html

- 50. Alvidrez J, Castille D, Laude‐Sharp M, Rosario A, Tabor D. The national institute on minority health and health disparities research framework. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(Suppl 1):S16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Carayon P. Human factors of complex sociotechnical systems. Appl Ergon. 2006;37:525–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pasmore W, Francis C, Haldeman J, Shani A. Sociotechnical systems: a North American reflection on empirical studies of the seventies. Hum Relat. 1982;35:1179–204. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Trist EL, Bamforth KW. Some social and psychological consequences of the longwall method of coal‐getting. Hum Relat. 1951;4:3–38. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Herrick‐Reynolds KM, Punchhi G, Greenberg RS, Strauss AT, Boyarsky BJ, Weeks‐Groh SR, et al. Evaluation of early vs standard liver transplant for alcohol‐associated liver disease. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:1026–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bhogal N, Dhaliwal A, Lyden E, Rochling F, Olivera‐Martinez M. Impact of psychosocial comorbidities on clinical outcomes after liver transplantation: stratification of a high‐risk population. World J Hepatol. 2019;11:638–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ladin K, Marotta SA, Butt Z, Gordon EJ, Daniels N, Lavelle TA, et al. A mixed‐methods approach to understanding variation in social support requirements and implications for access to transplantation in the United States. Prog Transplant. 2019;29:344–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358:483–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Crenesse‐Cozien N, Dolph B, Said M, Feeley TH, Kayler LK. Kidney transplant evaluation: inferences from qualitative interviews with African American patients and their providers. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6:917–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nonterah CW, Gardiner HM. Pre‐transplant evaluation completion for Black/African American renal patients: two theoretical frameworks. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103:988–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, Abaluck B, Localio AR, Kimmel SE, et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA. 2005;293:1197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available because of privacy or ethical restrictions.