Abstract

We examined the effects of human connection to nature on residents’ concerns about justice in conservation policies of Natura 2000. Expansion of Natura 2000 conservation network has resulted in local communities having to consider Natura 2000 in their development plans, and justice concerns have been strong in some communities near Natura 2000 sites. We conceptualized Natura 2000 justice within a framework composed of 3 domains of conservation justice: distribution, recognition, and representation. To examine the effect of nature connection on perceived justice of Natura 2000, we conducted a door‐to‐door survey of rural resident (80.09% response rate) in 3 municipalities of Pomerania in Poland. The effect of connection to nature on perceived distribution of Natura 2000 benefits was positive (b = 0.187, t = 7.057, p < 0.001); perceived communication about Natura 2000 was positive (b = 0.089, t = 2.940 p < 0.01); perception of limitations was positive (b = 0.078, t = 2.416, p < 0.01); perceived recognition was positive (b = 0.117, t = 3.367, p < 0.001); and perceived representation was positive (b = 0.123, t = 5.015, p < 0.001). Our results suggest local residents’ bonds with nature matter and they should be considered when new conservation approaches, such as Natura 2000, are introduced.

Keywords: biodiversity conservation; conservation policy making; justice; Natura 2000; nature connection; rural community; comunidad rural; conexión con la naturaleza; conservación de la biodiversidad; elaboración de políticas de conservación; justicia; Natura 2000; 保护政策制定, 乡村社区, 与自然的联系, 公正, 生物多样性保护, Natura 2000

Abstract

Efectos de la Conexión de los Residentes con la Naturaleza sobre la Percepción de la Política de Justicia de Conservación de Natura 2000 Stzelecka et al.

Resumen

Examinamos los efectos de la conexión humana con la naturaleza sobre los intereses de los residentes en cuanto a la justicia en las políticas de conservación de Natura 2000. Como resultado de la expansión de la red de conservación Natura 2000, las comunidades locales han tenido que considerarla dentro de sus planes de desarrollo y el interés por la justicia se ha fortalecido en algunas comunidades cercanas a los sitios de esta red. Definimos la justicia de Natura 2000 dentro de un marco compuesto por tres dominios de justicia de la conservación: distribución, reconocimiento y representación. Para analizar el efecto de la conexión con la naturaleza sobre la justicia percibida de Natura 2000, realizamos una encuesta a domicilio a los residentes rurales (80.09% de respuesta) de tres municipios de Pomerania en Polonia. El efecto de la conexión con la naturaleza fue positivo para las percepciones de la distribución de los beneficios (b = 0.187, t = 7.057, p < 0.001), la comunicación (b = 0.089, t = 2.940 p < 0.01), las limitaciones (b = 0.078, t = 2.416, p < 0.01), el reconocimiento (b = 0.117, t = 3.367, p < 0.001) y la representación (b = 0.123, t = 5.015, p < 0.001) de Natura 2000. Nuestros resultados sugieren que los lazos de los residentes locales con la naturaleza son importantes y deberían considerarse cuando se introduzcan nuevas estrategias de conservación, como Natura 2000.

与自然的联系对于居民看待Natura 2000保护政策公正性的影响

【摘要】我们研究了人类与自然的联系对于居民看待Natura 2000保护政策公正性的影响。Natura 2000保护网络的扩展导致当地社区不得不在其发展计划中考虑Natura 2000, 这引发了一些Natura 2000位点附近社区的人们对公正性的强烈担忧。我们提出了一个由保护公正性的三个领域(分配、认可和代表)组成的框架, 构建了Natura 2000公正性的概念。为了研究与自然的联系对Natura 2000公正性认知的影响, 我们在波兰波美拉尼亚的3个城市对乡村居民进行了逐户调查(受访率为80.09%)。结果表明, 居民与自然的联系对于其对Natura 2000利益分配的认知有积极影响(b=0.187, t=7.057, p<0.001);对Natura 2000交流情况的认知有积极影响(b=0.089, t=2.940 p<0. 01);对限制(b = 0.078, t = 2.416, p < 0.01)、认可(b = 0.117, t = 3.367, p < 0.001)、代表(b = 0.123, t = 5.015, p < 0.001)的认识都具有积极影响。我们的结果表明, 当地居民与自然的联系很重要, 在引入新的保护方法(如Natura 2000)时, 应考虑这些问题。【翻译:胡怡思;审校:聂永刚】

INTRODUCTION

The Natura 2000 network is a conservation program of the European Union (EU). The network consists of special protection areas and special areas of conservation, respectively, designated under the Birds and Habitats Directives. The former are meant to protect bird species listed in the Birds Directive (Directive 2009/147/EC), and the latter protect other animals, plants, and habitat types designated for protection in the Habitats Directive (Council Directive 92/43/EEC). Although the general principle of Natura 2000 management is not to worsen the condition of species and habitats at the protected sites (Nature Conservation Act 2004), specific conservation actions or restrictions at the sites have to be detailed in local Natura 2000 management plans. These regulations often affect landowners because Natura 2000 covers various land tenders and property regimes.

Natura 2000 has been a frequent subject of localized tensions. A sense of unjust treatment is strong in some communities near Natura 2000 sites (e.g., Apostolopoulou & Pantis, 2009; Blicharska et al., 2016; Grodzinska‐Jurczak & Cent, 2011a; Paloniemi et al., 2015). Strzelecka et al. (Strzelecka, Rechciński, et al., 2021; Strzelecka, Tusznio, et al., 2021) proposed a tripartite model of residents’ justice concerns regarding Natura 2000 to determine sources of perceived injustice related to Natura 2000 conservation policies. The model offers a radical, multifaceted approach to understanding conservation justice concerns. It defines justices and injustices in 3 domains: distribution, recognition, and representation (Fraser, 2008). Distribution justice typically refers to the allocation of environmental costs and how natural resources benefit local populations (Figueroa, 2006). Injustice, in this context, is commonly defined as unfair exposure to costs and benefits due to a new policy (Light & De‐Shalit, 2003). Recognition is about who gets to co‐create environmental policy (Fraser, 2008) and who has the power to vocalize values (Martin et al., 2013). Recognition also requires respect for identity and cultural differences in personal interactions and public discourse (Whyte, 2011). Here, we defined injustice as lack of recognition of human needs and values that occurs when local ways to relate to nature are overlooked or vulnerable local groups are excluded from conservation decision‐making (Figueroa, 2006). Finally, the representation of justice domain focuses on people being represented in political life (Mels, 2016). Injustice in this domain means particular perspectives in conservation policy making are ignored (Strzelecka, Rechciński, et al., 2021).

Conservation areas—such as with Natura 2000—are often situated near resource‐based communities whose livelihoods and well‐being depend on the local environment. Therefore, local support is essential for the area to meet long‐term conservation goals. That is, local perceptions of the conservation measures as fair may be necessary for local stakeholders to support them. However, while ensuring that those affected by conservation programs view them as just appears to be an essential facet of conservation policy making (Kals & Russell, 2001; Martin, 2017), understanding of what makes conservation policy be perceived as just is lacking.

Consequently, a better understanding of social–psychological factors that define residents’ justice concerns regarding conservation policy making is needed to address local conservation tensions and ensure program longevity (De Vreese et al., 2019; Dutcher et al., 2007). Research has consistently shown that an individual's connection to nature (i.e., sense of relationship with the natural world) may also be conducive to a sense of responsibility for nature (i.e., Roszak, 1992) and proenvironmental attitudes (i.e., Gosling & Williams, 2010).

Furthermore, that connection to nature (Baxter & Pelletier, 2019; Cleary et al., 2020) forms an affective, cognitive, and experiential basis for proenvironmental behavior (Mayer & Frantz, 2004; Nisbet, Zelenski, & Murphy, 2009). It is common to claim that a stronger inclusion of self in nature and nature connectedness is required to catalyze nature protection and environmental activism (Richardson et al., 2020). However, a significant research gap remains in addressing whether and how links between nature connectedness and the perception of conservation policy justice can simultaneously benefit the environment, residents, and conservation policy making (Feygina, 2013).

Thus, we explored the relationship between people's connection to nature and their perception of Natura 2000 justice within the distribution, recognition, and representation domains across 3 rural municipalities (Lipnica, Karsin, Choczewo) of the Pomerania region in Poland. We sought to make a 2‐fold contribution to knowledge on conservation policy making. First, we examined the relationship between nature connection and perceptions of Natura 2000 justice. Second, we considered our results in a broader context of human–nature relations to draw implications for conservation policy and practice.

Researchers have long understood that perceptions of justice regarding environmental conflicts may have practical implications (Kals & Russell, 2001) because conservation policies tend to be less effective when community residents disregard rules of nature protection that are perceived to be unfair (Keane et al., 2008). Furthermore, researchers found differences in justice perceptions between different contexts and situations (Mikula, 1980). Clayton et al. (2013) sought to understand what affects people's perceptions of injustice regarding environmental crises. Among other factors, environmental identity (EID) (which Clayton [2003] defines as individuals’ sense of themselves as interdependent with the natural world) was found to correlate with perceived injustice of environmental disaster. Another study of EID showed there are 4 underlying dimensions of EID (EID, enjoying nature, appreciation of nature, and environmentalism) (Olivos & Aragonés, 2011), which complicates interpretation of Clayton et al.’s (2013) results. Moreover, empirical research on the implications of residents’ connection with nature for perceived justice in conservation is still lacking, a problem we sought to address here.

Nature connection

Nature connection refers to the perceived and subjective relation people have with the nonhuman natural world. The strength of one's nature connection rests on a personal understanding of the surrounding environment (Gustafson, 2001) or its provision of other direct cultural services (Wheeler et al., 2015). The individual experience of nature connection tends to be driven by the quality and frequency of nature experiences (Beery & Wolf‐Watz, 2014; Schultz et al., 2004).

Nature connection fosters empathy and willingness to protect the natural environment people prefer (Gosling & Williams, 2010; Kals et al., 1999). People who believe they are part of the natural world will feel more compassionate toward nature. In contrast, a lack of nature connection amounts to alienation from nature (Dutcher et al., 2007). Nature connection may also be conducive to responsibility for nature (Roszak, 1992).

A robust nature connection may nurture a positive perception of justice of a new conservation policy in a local community when that policy supports how community residents connect with nature. In contrast, when a policy contradicts traditional ways community residents connect with nature, their nature bond may catalyze perceptions of injustice regarding a new conservation policy.

Conservation policy justice

Perceptions of justice are context and location specific (Clayton et al., 2018; Strzelecka, Rechciński, et al., 2021; Strzelecka, Tusznio, et al., 2021); thus, particular justice concerns are not relevant in all communities (Strzelecka, Tusznio, et al., 2021). From this perspective, perceptions of justice regarding new conservation policies depend on the value people place on nature and EID (Clayton et al., 2013; Figueroa, 2006). We considered the different justice concerns—distribution, recognition, and representation—people have regarding Natura 2000 and how residents’ nature connection links to these concerns.

Residents are concerned about the unevenly distributed economic costs of Natura 2000 (Grodzińska‐Jurczak & Cent, 2011; Boltromiuk, 2012) because Natura 2000 sites can limit economic activity (e.g., Dubel et al., 2013). Private landowners, for instance, see Natura 2000 as a constraint to managing their property (Grodzińska‐Jurczak & Cent, 2011a; Kamal et al., 2013). Poor communication with local communities about Natura 2000 before and in the early stages of the policy making has been problematic. Limited access, a lack of reliable information, and miscommunication produced mistrust toward Natura 2000 (Cent et al., 2013).

The character of local reactions to the perceived distribution of Natura 2000 benefits, limitations, and communication will likely depend on whether residents believe Natura 2000 will change their relationship with nature and how desirable that change is. Therefore, we tested the following hypotheses: connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of the distribution of benefits from Natura 2000 (H1); connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of communication about Natura 2000 (H2); and connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of limitations of economic activity due to Natura 2000 (H3).

Recognition concerns refer to accounting for residents’ practices in nature and values of it in policy making. When a new conservation endeavor, such as Natura 2000, is perceived as nurturing how residents relate to nature, nature connection can strengthen residents’ positive response to the policy. However, the designation of Natura 2000 sites and top‐down implementation provoked local tensions, especially when these decisions coincided with piecemeal information about Natura 2000. Marginalizing local communities in the site‐designation process undermined the democratic virtue of citizen involvement in nature conservation and left many communities misconstructing Natura 2000 impacts on local livelihoods (Strzelecka et al., 2021). Thus, we tested the hypothesis that connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of recognition within Natura 2000 policy making (H4).

Local political spaces constitute the prime modes of representation (Fraser, 2008; Mels, 2016), where residents voice their concerns and share experiences. It is due to poor representation of local communities in Natura 2000 policy making (both sites designation and creating principles of Natura 2000 management plans) that Natura 2000 solutions failed to incorporate diverse perspectives (Apostolopoulou & Pantis, 2009; Bołtromiuk, 2012; Grodzińska‐Jurczak & Cent, 2011a; Strzelecka, Rechciński, et al., 2021).

Nature connection may affect residents’ concerns about community representation in conservation policy making, particularly if it affects how the local community relates to nature. For instance, residents with stronger nature connections may demand a stronger representation in making conservation policies potentially affecting how they interact with nature. Hence, they are likely to be more concerned about their perspective being represented in the outcome of policy decision‐making. Thus, we tested the hypothesis that connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of representation within Natura 2000 policy making (H5).

METHODS

Measurement scales

We adapted the perceived environmental justice scale, a validated multidimensional instrument to assess resident justice concerns within distribution, recognition, and representation domains of Natura 2000 (Strzelecka, Tusznio, et al., 2021). The connectedness to nature scale concerns the relationship between one's self‐image and nature (Mayer & Frantz, 2004). It is one of the most widely applied scales to study how individuals understand their connection to nature. The scale has been internationally tested for construct validity (e.g., Navarro et al., 2017; Perrin & Benassi, 2009; Restall & Conrad, 2015). All items included in the measurements were assessed based on a 5‐point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Site‐selection criteria

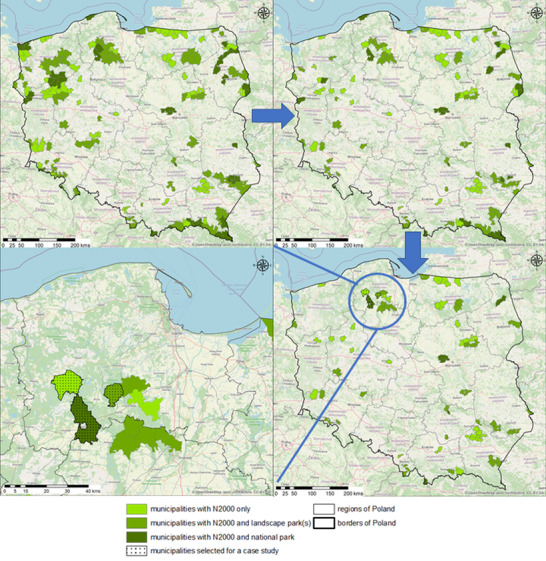

To be selected, a municipality had to be rural and have >50% Natura 2000 coverage, >5000 residents, and different nature conservation regimes. The municipalities had to adjoin each other so they would have similar natural assets and socioeconomic conditions. Three rural municipalities in the Pomerania region of Poland met these criteria (Figure 1): Lipnica (only Natura 2000), Karsin (Natura 2000 and a landscape park), and Chojnice (Natura 2000 and a national park).

FIGURE 1.

The process of evaluating the study area in Poland to survey connectedness to nature's relation to perceptions of Natura 2000 justice (arrows, steps in the process)

Participants and procedure

The team of trained surveyers conducted door‐to‐door survey in July and August of 2018 to residents of 12 (of 18) towns and villages in Lipnica, 11 (of 13) towns and villages in Karsin, and 14 (of 37) towns and villages in Chojnice. The survey questions are available in Appendix S1. Survey distribution was based on a census‐guided systematic random sampling scheme (Strzelecka, Rechciński, et al., 2021). The sampling scheme enabled gathering a representative sample of residents, increased response rates, and included groups that may be left out with other sampling methods (Lipnica: 531 distributed, 402 returned; Karsin: 669 distributed, 413 returned; Chojnice: 734 distributed, 534 returned).

Out of 1549 returned questionnaires (80.09% response rate), several were discarded after initial data screening due to missing values >5%, leaving 1312 usable questionnaires for further analysis. The mean replacement algorithm was used as a placeholder for missing values <5%. However, this technique did not affect the total mean of each item (Hair et al., 2010). The sample included responses from 778 (59.3%) women and 531 (40.5%) men, and 21 respondents did not supply sex, 205 (15.4%) respondents were <25 years old, 297 (22.3%) were 26–36, 272 (20.5%) were 36–45, 255 (19.2%) were 46–55, and the rest were over 56 (22.6%).

We used partial least squares structural equation modeling to validate the measurement model and test the hypotheses (Hair et al., 2017). We performed a partial least squares multigroup analysis (PLS‐MGA) to investigate the differences between municipalities in residents’ relationship between connectedness to nature and Natura 2000 justice. We used analysis of variance (ANOVA) to find the differences among municipalities in each of the constructs separately.

RESULTS

Preliminary results

The normal distribution of the data was in the acceptable range of ±3 for skewness and kurtosis. The outer model loadings met the recommended cutoff value of 0.70 (Table 1). The composite reliability range was 0.8–0.9, which provided evidence of internal consistency reliability. All Cronbach's alphas of the variables met the threshold of 0.7. Also, ρ A achieved the cutoff level of 0.7 (Table 1). Multicollinearity (variance inflation factor <3) was reflected in the variance (Table 1). Average variance extracted (AVE) indicated the constructs explained >50% of the variance of their related items (AVE > 0.50), which provided evidence of convergent validity of the measurement model. Results of the discriminant validity assessment based on Fornell and Larcker's (1981) criteria are presented in Table 2. The Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio of correlations was within the acceptable cutoff level of <0.90.

TABLE 1.

Items’ loading, construct reliability and validity, and descriptive statistics in survey of Karsin, Lipnica, and Chojnice about Natura 2000 (N2000)

| Construct and item | Loading | VIF | AVE | CR | α | ρ A | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefit | 0.681 | 0.895 | 0.848 | 0.879 | ||||

| Decisions about N2000 benefit everyone. | 0.860 | 1.894 | 2.981 | 1.261 | ||||

| Benefits from N2000 are distributed equally among residents of this region. | 0.796 | 2.067 | 2.669 | 1.154 | ||||

| Benefits from N2000 are distributed according to residents' needs. | 0.817 | 2.208 | 2.726 | 1.120 | ||||

| The N2000 program will, on average, leave residents better off. | 0.826 | 1.742 | 3.017 | 1.204 | ||||

| Communication | 0.662 | 0.854 | 0.758 | 0.883 | ||||

| Residents are well informed about N2000. | 0.729 | 1.451 | 2.253 | 1.221 | ||||

| It is easy to access information about N2000. | 0.800 | 1.586 | 2.917 | 1.255 | ||||

| Problems related to N2000 are adequately managed. | 0.902 | 1.571 | 2.851 | 1.036 | ||||

| Limitation | 0.718 | 0.884 | 0.811 | 0.903 | ||||

| Residents' economic activities are restricted because of N2000. | 0.900 | 1.760 | 3.256 | 1.229 | ||||

| Infrastructure development is impeded because of N2000. | 0.859 | 2.097 | 3.251 | 1.255 | ||||

| Opportunities for the economic development of this region are limited because of N2000. | 0.778 | 1.670 | 3.098 | 1.178 | ||||

| Recognition | 0.570 | 0.930 | 0.923 | 1.078 | ||||

| The way N2000 is managed corresponds with my perspective. | 0.812 | 1.774 | 2.621 | 1.096 | ||||

| My concerns about N2000 have been recognized in N2000 decision‐making in this municipality. | 0.715 | 2.267 | 2.476 | 1.093 | ||||

| My views, as a resident, are considered in managing N2000 sites. | 0.771 | 2.536 | 2.460 | 1.116 | ||||

| My economic needs are recognized through N2000 regulations. | 0.735 | 2.269 | 2.452 | 1.086 | ||||

| Residents' knowledge of local nature has been used to designate N2000 sites. | 0.718 | 1.897 | 2.651 | 1.167 | ||||

| As a resident of this municipality, I am an equal partner in the implementation of N2000. | 0.741 | 1.848 | 2.261 | 1.170 | ||||

| Potential differences of interests have been promptly acknowledged in managing N2000 sites. | 0.722 | 1.921 | 2.624 | 1.039 | ||||

| Residents have been recognized as an equal partner in managing N2000. | 0.773 | 2.518 | 2.489 | 1.130 | ||||

| Residents' interests are taken into consideration in managing N2000. | 0.789 | 2.541 | 2.599 | 1.122 | ||||

| My voice counts in decision‐making for N2000. | 0.765 | 2.294 | 2.264 | 1.143 | ||||

| Representation | 0.615 | 0.889 | 0.849 | 0.887 | ||||

| Natura 2000 empowers residents. | 0.816 | 1.866 | 2.652 | 1.115 | ||||

| Natura 2000 decision‐making procedures are fair. | 0.818 | 2.207 | 2.766 | 1.049 | ||||

| Natura 2000 procedures enable me to engage in the decision‐making process. | 0.719 | 1.903 | 2.399 | 1.074 | ||||

| Natura 2000 procedures are clear to me. | 0.723 | 1.613 | 2.576 | 1.109 | ||||

| Natura 2000 procedures ensure that decisions are made based on facts. | 0.838 | 1.938 | 2.792 | 1.078 | ||||

| Connectedness to nature | 0.589 | 0.920 | 0.901 | 0.908 | ||||

| I feel that all inhabitants of Earth, human and nonhuman, share a common life force. | 0.809 | 2.345 | 3.660 | 1.151 | ||||

| I often feel a sense of oneness with the natural world around me. | 0.741 | 2.254 | 4.028 | 1.031 | ||||

| I think of the natural world as a community to which I belong. | 0.806 | 2.581 | 4.121 | 0.965 | ||||

| I recognize and appreciate the intelligence of other living organisms. | 0.758 | 1.931 | 4.256 | 0.916 | ||||

| When I think of my life, I imagine myself as part of a larger cyclical process of living. | 0.705 | 1.588 | 3.568 | 1.096 | ||||

| I often feel a kinship with animals and plants. | 0.748 | 2.038 | 3.960 | 1.064 | ||||

| I feel as though I belong to Earth as equally as it belongs to me. | 0.770 | 2.299 | 4.011 | 1.031 | ||||

| I often feel part of the web of life. | 0.797 | 2.313 | 3.866 | 1.018 |

Abbreviations: AVE, average variance extracted; CR, composite reliability; VIF, variance inflation factor; α, Cronbach's alpha; ρ A, Dijkstra and Henseler's rho.

TABLE 2.

Discriminant validity of benefits, communication, connectedness to nature (CtN), limitation, recognition, and representation based on Fornell–Larcker criteria

| Benefits | Communication | CtN | Limitation | Recognition | Representation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits | 0.825 | |||||

| Communication | 0.432 | 0.814 | ||||

| CtN | 0.182 | 0.081 | 0.767 | |||

| Limitation | −0.125 | 0.047 | 0.073 | 0.847 | ||

| Recognition | 0.580 | 0.533 | 0.103 | −0.035 | 0.755 | |

| Representation | 0.565 | 0.489 | 0.115 | −0.096 | 0.680 | 0.785 |

Note: Numbers not on the diagonal are the latent correlations, and numbers on the diagonal are the square roots of the average variance extracted.

Hypothesis testing

Stone–Geisser's values were >0 (Hair et al., 2017). The R 2 of endogenous variables was relatively small (benefit, 0.033; limitation, 0.005; communication, 0.007; recognition, 0.011; representation, 0.013).

The path from connectedness to nature to benefits was positive and statistically significant (b = 0.187, t = 7.057, p < 0.001), supporting H1 (Table 3). The path from connectedness to nature to communication was also positive and significant (b = 0.089, t = 2.940 p < 0.01); therefore, H2 was supported. Connectedness to nature and limitation was positive and statistically significant (b = 0.078, t = 2.416, p < 0.01), providing support for H3. Connectedness to nature was positively and statistically related to recognition (b = 0.117, t = 3.367, p < 0.001); therefore, H4 was supported. Finally, the path from connectedness to nature to representation was statistically significant (b = 0.123, t = 5.015, p < 0.001), which supported H5 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Results of path analysis relative to tested hypotheses of connectedness to nature related to perceptions of Natura 2000 justice

| Hypothesis | Path coefficient | SD | t | p | CI* | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of the distribution of benefits from Natura 2000 | 0.187 | 0.026 | 7.057 | 0.000 | 0.135 | 0.237 | supported |

| Connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of communication about Natura 2000 | 0.089 | 0.028 | 2.940 | 0.003 | 0.037 | 0.141 | supported |

| Connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of limitations of economic activity due to Natura 2000 | 0.078 | 0.030 | 2.416 | 0.016 | 0.027 | 0.133 | supported |

| Connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of recognition within Natura 2000 policy making | 0.117 | 0.031 | 3.367 | 0.001 | 0.085 | 0.161 | supported |

| Connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of representation within Natura 2000 policy making | 0.123 | 0.023 | 5.015 | 0.000 | 0.078 | 0.170 | supported |

First number in the pair is 2.5% CI and the second number is the 95% CI.

The results of PLS‐MGA (Table 4) showed there were no differences across the municipalities in residents’ relationship between connectedness to nature and Natura 2000 justice. Further, the ANOVA (Appendix S2) showed that although no difference existed in the interpretations of nature connectedness in the local context, residents perceived most of the justice domains (i.e., benefit, communication, recognition, and representation) differently in the 3 study areas.

TABLE 4.

Results of multigroup analysis across different municipalities in a survey of connectedness to nature related to perceptions of Natura 2000 justice

| Path coefficient difference* | p * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 3 | 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 3 |

|

Connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of the distribution of benefits from Natura 2000. |

0.005 | –0.016 | –0.021 | 0.933 | 0.804 | 0.736 |

|

Connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of communication about Natura 2000. |

–0.130 | 0.022 | 0.152 | 0.202 | 0.780 | 0.059 |

|

Connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of limitations of economic activity due to Natura 2000. |

–0.067 | –0.010 | 0.057 | 0.634 | 0.942 | 0.510 |

| Connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of recognition within Natura 2000 policy making. | –0.049 | –0.136 | –0.087 | 0.593 | 0.683 | 0.746 |

|

Connection to nature predicts residents’ perceptions of representation within Natura 2000 policy making. |

–0.017 | –0.019 | –0.002 | 0.637 | 0.803 | 0.813 |

Codes: 1, Karsin Municipality; 2, Lipnica Municipality; 3, Chojnice Municipality.

DISCUSSION

Whether or not local communities support a new conservation policy depends on how just the policy making is in their interpretations (Clayton, 2018; Kals & Russel, 2001). Our approach enabled us to address how factors, such as residents’ nature connection, may affect locally expressed concerns regarding conservation policy justice. The results illustrated that perceptions of justice regarding conservation policy making (distribution, recognition, representation) are likely to depend on resident nature connectedness. Thus, the theoretical contribution of this research lies in that it extends the tripartite justice perspective to include nature connection as a predictor of perceived justice and injustice regarding conservation policy making. These findings align with a broader literature indicating that how people relate to nature affects their perception of nature conservation efforts as well as environmental behaviors (e.g., Gosling & Williams, 2010; Kals et al., 1999; Kals & Russel, 2001; Perkins, 2010).

The positive link between nature connection and a sense of Natura 2000 limitations may seem surprising. However, because we asked how respondents agree with statements expressing perceived limitation on local economic development, it is plausible that those who felt a greater connection with nature perceived greater economic limitations from Natura 2000. We did not examine how important the economic development of rural municipalities is for people living there. Thus, although robust nature connection may contribute to a more advanced understanding of potential economic limitations due to Natura 2000, our results did not indicate that the limitations to economic development due to the policy are problematic for the residents. It might be that a stronger nature connection generates greater interest in learning about a new conservation policy, increasing awareness of its potential economic effect on the rural area. Future research can explore the link between the perceived importance of the area's economic development and perceptions of Natura 2000.

We built on the argument that a sense of conservation justice is needed for an environmental policy to be well received by rural residents near protected areas. Although prior research suggests that interpretations of justice in conservation policy making depend on the local context in which they are carried out, we found no differences in the local context when investigating the relationship between connection to nature and policy justice domains. However, further analysis (Appendix S2) showed that although no difference existed in the interpretations of nature connectedness in the local context, residents perceived most of the justice domains (i.e., benefit, communication, recognition, and representation) differently in the 3 study areas. This may be because Natura 2000 overlaps with a different form of nature protection in 2 out of 3 studied municipalities (Figure 1). Thus, residents in those municipalities may have different interpretations of justice concerns due to other forms of nature protection that may influence local perceptions of Natura 2000 policy making. Future studies in culturally and environmentally different locations could help determine whether the patterns we found in the 3 study areas are generalizable. There is also a need to better understand how demographics affect the relationship between connection to nature and justice concerns regarding conservation policies. Finally, future research should consider how environmental policies can further contribute to people's relationship with nature in aspects other than their concern for policy justice. Strengthening this connection may simultaneously contribute to human well‐being and ecological sustainability (Riechers et al., 2021) and produce more just and environmentally effective solutions.

An important policy implication of our results is that in places with a strong link between residents and nature, conservation policy needs to incorporate local environmental values and local cultures. Our research is especially timely in the context of the new Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 being devised for the EU; existing Natura 2000 areas will be enlarged and there will be strict protection in areas of very high biodiversity and climate value. Residents’ bonds with nature must be better understood before a Natura 2000 is expanded. One way to consider a resident connection to nature is to engage them in various forms of nature stewardship. For example, rather than a top‐down public consultation, organizing local teams to codesign Natura 2000 management plans may be beneficial. Such place‐based policy‐making approaches become most useful for local communities located near Natura 2000 areas because the connection to nature among the community residents tends to be higher (Restall et al., 2021).

With ever‐changing human–nature relationships (Barragan‐Jason et al., 2022), international conservation policy schemes must increasingly work with local communities to tailor policy instruments and solutions to their needs and expectations while meeting conservation goals. Past research shows no single solution to improve perceptions of conservation policies, and many participatory programs fail to engage locals or mitigate conflicts. Considering extended, 3‐dimensional environmental justice and its interplay with peoples’ relationship with nature provides valuable insights for the inclusive design of conservation policy making.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

Appendix S2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was financed through National Science Centre, Poland (Narodowe Centrum Nauki) under POLONEZ 2016/23/P/HS6/04017 and received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska‐Curie grant agreement number 665778.

Strzelecka, M. , Tusznio, J. , Akhshik, A. , Rechcinski, M. , & Grodzinska‐Jurczak, M. (2022). Effects of connection to nature on residents’ perceptions of conservation policy justice of Natura 2000. Conservation Biology, 36, e13944. 10.1111/cobi.13944

Article Impact statement: Rural residents’ concerns about the justice of international biodiversity conservation programs depend on how they connect to nature.

REFERENCES

- Apostolopoulou, E. , & Pantis, J. D. (2009). Conceptual gaps in the national strategy for the implementation of the European Natura 2000 conservation policy in Greece. Biological Conservation, 142(1), 221–237. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, D. E. , & Pelletier, L. G. (2019). Is nature relatedness a basic human psychological need? A critical examination of the extant literature. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 60(1), 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Barragan‐Jason, G. , de Mazancourt, C. , Parmesan, C. , Singer, M. C. , & Loreau, M. (2022). Human–nature connectedness as a pathway to sustainability: A global meta‐analysis. Conservation Letters, 15, e12852. 10.1111/conl.12852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beery, T. H. , & Wolf‐Watz, D. (2014). Nature to place: Rethinking the environmental connectedness perspective. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 40, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Blicharska, M. , Orlikowski, E. H. , Roberge, J.‐M. , & Grodzinska‐Jurczak, M. (2016). Contribution of social science to large‐scale biodiversity conservation: a review of research about the Natura 2000 network. Biological Conservation, 199, 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Boltromiuk, A. (2012). Natura 2000 ‐ The opportunities and dilemmas of the rural development within the European ecological network. Problems of Sustainable Development, 7(1), 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, D. E. , & Pelletier, L. G. (2019). Is nature relatedness a basic human psychological need? A critical examination of the extant literature. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 60(1), 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cent, J. , Mertens, C. , & Niedziałkowski, K. (2013). Roles and impacts of non‐governmental organizations in Natura 2000 implementation in Hungary and Poland Environ. Conserv., 40(2), 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S. (2003). Environmental identity: A conceptual and an operational definition. In Clayton S., & Opotow S. (Eds.), Identity and the natural environment (pp. 45–65). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S. , Koehn, A. , & Grover, E. (2013). Making Sense of the Senseless: Identity, Justice, and the Framing of Environmental Crises. Social Justice Research, 26, 301–319. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S. (2018). The role of perceived justice, political ideology, and individual or collective framing in support for environmental policies. Social Justice Research, 31, 219–237. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, A. , Fielding, K. S. , Murray, Z. , & Roiko, A. (2020). Predictors of Nature Connection Among Urban Residents: Assessing the Role of Childhood and Adult Nature Experiences. Environment and Behavior, 52(6), 579–610. [Google Scholar]

- De Vreese, R. , Van Herzele, A. , Dendoncker, N. , Fontaine, C. M. , & Leys, M. (2019). Are ‘stakeholders’ social representations of nature and landscape compatible with the ecosystem service concept? Ecosystem Services, 37, 100911. [Google Scholar]

- Dubel, A. , Jamontt‐Skotis, M. , Krolikowska, K. , Dubel, K. , & Czapski, M. (2013). Metody rozwiązywania konfliktów ekologicznych na obszarach Natura 2000. Stowarzyszenie Centrum Rozwiązań Systemowych. [Google Scholar]

- Dutcher, D. D. , Finley, J. C. , Luloff, A. E. , & Buttolph Johnson, J. (2007). Connectivity with nature as a measure of environmental values. Environmental Behavior, 39, 474–493. [Google Scholar]

- Feygina, I. (2013). Social justice and the human–environment relationship: Common systemic, ideological, and psychological roots and processes. Social Justice Research, 26(3), 363–381. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa, R. (2006). Evaluating environmental justice claims. In Bauer, J. (Ed.). Forging environmentalism: Justice, livelihood, and contested environments (pp. 360–376). M.E. Sharpe. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C. , & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. (2008). Scales of Justice. Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World ( Cambridge, G.‐B. , Malden, E.‐U. ) Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling, E. , & Williams, K. J. H. (2010). Connectedness to nature, place attachment and conservation behaviour: Testing connectedness theory among farmers. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(3), 298–304. [Google Scholar]

- Grodzińska‐Jurczak, M. , & Cent, J. (2011a). Expansion of nature conservation areas: Problems with Natura 2000 implementation in Poland? Environmental Management, 47, 11–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodzińska‐Jurczak, M. , & Cent, J. (2011b). Can public participation increase nature conservation effectiveness? Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 24(3), 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson, P. E. R. (2001). Meanings of place: Everyday experience and theoretical conceptualizations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(1), 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. , Black, W. C. , Babin, B. J. , & Anderson, R. E. (2017). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F. , Black, W. C. , Babin, B. J. , & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed., Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Cent, J. , Mertens, C. , & Niedziałkowski, K. (2013). Roles and impacts of non‐governmental organizations in Natura 2000 implementation in Hungary and Poland Environ. Conserv., 40(2), 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kals, E. , & Russell, Y. (2001). Individual conceptions of justice and their potential for explaining proenvironmental decision making. Social Justice Research, 14(4), 367–385. [Google Scholar]

- Kals, E. , Schumacher, D. , & Montada, L. (1999). Emotional affinity toward nature as a motivational basis to protect nature. Environment and Behavior, 31(2), 178–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, S. , Grodzińska‐Jurczak, M. , , & Brown, G. (2013). Conservation on private land: A review of global strategies with a proposed classification system. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 58(4), 576–597. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, A. , Jones, J. P. G. , Edwards‐Jones, G. , & Milner‐Gulland, E. J. (2008). The sleeping policeman: Understanding issues of enforcement and compliance in conservation. Animal Conservation, 11, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Light, A. , & De‐Shalit, A. (Eds.). (2003). Moral and political reasoning in environmental practice. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A. , McGuire, S. , & Sullivan, S. (2013). Global environmental justice and biodiversity conservation. The Geographical Journal, 179, 122–131. 10.1111/geoj.12018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A. (2017). Just conservation: Biodiversity, wellbeing and sustainability. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, F. S. , & Frantz, C. M. (2004). The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals' feeling in community with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(4), 503–515. [Google Scholar]

- Mels, T. (2016). The trouble with representation: Landscape and environmental justice. Landscape Research, 41(4), 417–424. [Google Scholar]

- Mikula, G. (1980). Justice and social interaction: Experimental and theoretical contributions from psychological research. Springer‐Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, O. , Olivos, P. , & Fleury‐Bahi, G. (2017). “Connectedness to nature scale”: Validity and reliability in the French context. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2180. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet, E. K. , Zelenski, J. M. , & Murphy, S. A. (2009). The Nature Relatedness Scale: Linking Individuals’ Connection With Nature to Environmental Concern and Behavior. Environment and Behavior, 41(5), 715–740. [Google Scholar]

- Olivos, P. , & Aragonés, J.‐I. (2011). Psychometric properties of the Environmental Identity Scale (EID). PsyEcology, 2(1), 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Paloniemi, R. , Apostolopoulou, E. , Cent, J. D. , Bormpoudakis, A. S. , Grodzińska‐Jurczak, M. , Tzanopoulos, J. , Koivulehto, M. , Pietrzyk‐Kaszyńska, A. , & Pantis, J. D. (2015). Public participation and environmental justice in biodiversity governance in Finland, Greece, Poland and the UK. Environmental Policy and Governance, 25, 330–342. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, J. L. , & Benassi, V. A. (2009). The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of emotional connection to nature? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29, 434–440. [Google Scholar]

- Restall, B. , Conrad, E. , & Cop, C. (2021). Connectedness to nature: Mapping the role of protected areas. Journal of Environmental Management, 293, 112771. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restall, B. , & Conrad, E. (2015). A literature review of connectedness to nature and its potential for environmental management. Journal of Environmental Management, 159, 264–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, M. , Passmore, H. A. , Barbett, L. , Lumber, R. , Thomas, R. , & Hunt, A. (2020). The green care code: How nature connectedness and simple activities help explain pro‐nature conservation behaviours. People and Nature, 2(3), 821–839. [Google Scholar]

- Riechers, M. , Balázsi, Á. , García‐Llorente, M. , & Loos, J. (2021). Human‐nature connectedness as leverage point. Ecosystems and People, 17(1), 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Roszak, T. (1992). The voice of the earth: An exploration of ecopsychology. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P. W. , Shriver, C. , Tabanico, J. J. , & Khazian, A. M. (2004). Implicit connections with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(1), 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecka, M. , Rechciński, M. , Tusznio, J. , Akhshik, A. , & Grodzińska‐Jurczak, M. (2021). Environmental justice in Natura 2000 conservation conflicts: The case for resident empowerment. Land Use Policy, 107, 105494. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecka, M. , Tusznio, J. , Rechcinski, R. , Bockowski, M. , & Grodzinska‐Jurczak, M. (2021). Resident perceptions of distribution, recognition and representation justice domains of environmental policy‐making: The case of European ecological network Natura 2000 in Poland. Society & Natural Resources, 34(2), 248–268. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, B. W. L. , R, S. L. H. , White, M. P. , Alcock, I. , Osborne, N. J. , Husk, K. , Sabel, C. E. , & Depledge, M. H. (2015). Beyond greenspace: An ecological study of population general health and indicators of natural environment type and quality. International Journal of Health Geography, 14, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, K. (2011). Recognition dimension of environmental justice in Indian country. Environmental Justice, 4(4), 199–205. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Appendix S2