Abstract

The interaction of Listeria monocytogenes with endothelial cells represents a crucial step in the pathogenesis of listeriosis. Incubation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) with wild-type L. monocytogenes (EGD) provoked immediate strong NO synthesis, attributable to listerial presentation of listeriolysin O (LLO), as the NO release was missed upon employment of a deletion mutant for LLO (EGD hly mutant) and was reproduced by purified LLO. Studies of conditions lacking extracellular Ca2+ suggested LLO-elicited Ca2+ flux as the underlying mechanism. In addition, HUVEC incubation with EGD turned out to be a potent stimulus for sustained (>12-h) upregulation of proinflammatory cytokine generation (interleukin 6 [IL-6], IL-8, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor). Use of deletion mutants for LLO (EGD hly mutant), listerial phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (EGD plcA mutant), broad-spectrum phospholipase C (EGD plcB mutant) and internalin B (EGD inlB mutant), as well as purified LLO, identified LLO as largely responsible for the cytokine response. Endothelial cells responded with diacylglycerole and ceramide generation as well as nuclear translocation of NF-κB to the stimulation with the LLO-producing strains EGD and Listeria innocua. The endothelial PC-phospholipase C inhibitor tricyclodecan-9-yl-xanthogenate as well as two independent inhibitors of NF-κB activation, pyrolidine dithiocarbamate and caffeic acid phenethyl ester, suppressed both the NF-κB translocation and the upregulation of cytokine synthesis. We conclude that L. monocytogenes is a potent stimulus of NO release and sustained upregulation of proinflammatory cytokine synthesis in human endothelial cells, both events being largely attributable to LLO presentation. LLO-induced transmembrane Ca2+ flux as well as a sequence of endothelial phospholipase activation and the appearance of diacylglycerole, ceramide, and NF-κB are suggested as underlying host signaling events. These endothelial responses to L. monocytogenes may well contribute to the pathogenic sequelae in severe listerial infection and sepsis.

Infections of humans with the gram-positive facultative intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes may cause severe diseases such as sepsis or meningitis, mainly in newborns and in elderly and immunocompromised persons (11). L. monocytogenes is capable of replicating in a variety of professional phagocytes. In addition, endothelial cells are assumed to be important target cells for infection with L. monocytogenes, and breaching endothelial barriers is a central event in the pathogenesis of septic organ failure, including meningitis (blood-brain barrier) (9, 28). Besides being passive targets, endothelial cells were suggested to be early and active participants in the inflammatory response during the hematogenous spread of L. monocytogenes (9).

The pathogenicity of L. monocytogenes is dependent on several virulence determinants. The best-characterized factor is listeriolysin O (LLO), a member of the family of sulfhydryl-activated pore-forming cytolysins. Intracellular expression of LLO mediates lysis of bacterium-containing vacuoles and is mandatory for intracellular survival and replication. In addition, extracellular release of LLO was recently noted to be a potent stimulus for endothelial cell activation, including expression of surface adhesion molecules (10, 17, 33) and lipid mediator generation and phosphatidylinositol response (36, 37). As a cooperative agent with LLO, a listerial phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PlcA) has been identified, which enhances LLO-provoked phosphatidylinositol metabolism (37) and E-selection expression (33) in human endothelial cells. PlcA and a broad-spectrum phospholipase C with phosphatidylcholine as the preferred substrate (PlcB) were originally characterized as enzymes additionally employed for the escape of L. monocytogenes from the vacuole and cell-to-cell spread (12, 39) but might well contribute to cell signaling events via generation of diacylglycerole (DAG) (33, 36). In addition, the surface-binding protein internalin B (InlB) was recently noted to be essential for the adhesion of L. monoctogenes to human endothelial cells (28).

Most pertinent inflammatory agents, liberated from activated endothelial cells under conditions of sepsis and severe infection, are the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-8, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), as well as the short-lived radical nitric oxide (NO) (19, 22). NO has in particular been implicated in severe arterial hypotension and perfusion maldistribution as a hallmark of septic shock (18, 19). IL-8 is a potent chemotactic factor for T lymphocytes and neutrophils, whereas GM-CSF attracts both monocytes and neutrophils to the inflammatory focus (31, 48). The multifunctional proinflammatory IL-6, an important cofactor in the activation of lymphocytes, induces T- and B-cell differentiation and T-cell proliferation, thereby processing antibody production in B cells, cytotoxic T-cell differentiation, and acute phase protein synthesis (1, 40). The release of leukocyte-activating cytokines is of major importance, since several studies have demonstrated that polymorphonuclear neutrophils are essential for both early nonspecific resistance and generation of specific T-cell mediated immunity (6, 30, 38).

In the present study of human endothelial cells, we show that L. monocytogenes, in the absence of cell invasion, is a potent stimulus for the immediate release of NO and the sustained liberation of IL-6, IL-8, and GM-CSF. Employing genetically engineered mutants of L. monocytogenes and the avirulent Listeria innocua (INN), as well as purified toxin, we demonstrate a predominant role of the pore-forming LLO in eliciting the liberation of these proinflammatory mediators. Downstream host-signaling events are suggested to include transmembrane Ca2+ shift as well as activation of endogenous phospholipases C with subsequent appearance of DAG and ceramide and nuclear translocation of NF-κB. These studies add further to the understanding of pathogenic mechanisms in listeriosis, in particular the endothelial cell response to listerial virulence factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Medium 199, fetal calf serum (FCS), HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid), Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS), phosphate-buffered saline, trypsin-EDTA solution, brain heart infusion (BHI), and antibiotics were obtained from Gibco (Karlsruhe, Federal Republic of Germany). Collagenase (CLS type II) was purchased from Worthington Biochemical Corp. BCA protein assay and standards, Nonidet P-40, ammonium persulfate, N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine, PDTC (pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate), cytochalasin D, polyacrylamide, A23187, thrombin, and isobutyl methylxanthine were obtained from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Federal Republic of Germany). poly(dI-dC) was from Pharmacia Biotech (Freiburg, Federal Republic of Germany). NO gas was purchased from Schuchardt (Munich, Federal Republic of Germany). Xanthogenate tricyclodecan-9-yl (D609) was kindly provided by M. Kronke (Cologne, Federal Republic of Germany). Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) was obtained from Calbiochem (Bad Soden, Federal Republic of Germany). [γ-32P]ATP (specific activity, 4,500 Ci/mmol), diglyceride kinase, 125I-cGMP assay system, 5′-end labeling kit and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were purchased from Amersham (Dreieich, Federal Republic of Germany). The double-stranded oligonucleotide was obtained from Roth (Karlsruhe, Federal Republic of Germany). The lactate dehydrogenase assay was obtained from Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Federal Republic of Germany. All other biochemicals were obtained from Merck (Munich, Federal Republic of Germany).

Bacterial strains.

Table 1 gives an overview of the Listeria strains used in the present study. Recombinant strains of L. monocytogenes and L. innocua were obtained as previously described (5). The apathogenic L. innocua was used as host for the selective expression of the LLO gene (hly). To induce high levels of either protein from the respective recombinant strain, the hly gene was cloned onto a plasmid also harboring the prfA regulator. Bacteria were grown in BHI broth at 37°C, and erythromycin (5 μg/ml) was used wherever appropriate. The hemolysin assay was performed as described previously (21), except that human erythrocytes were used at a final concentration of 0.5%.

TABLE 1.

Listeria strains used in the present study

| Strain | Serotype | Relevant genotype | Hemolytic phenotypea | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. monocytogenes | ||||

| EGD | 1/2a | Wild type | + | EGD |

| EGDdhly1 | 1/2a | hly1 | − | EGD hly mutant |

| EGDdplcA | 1/2a | plcA | + | EGD plcA mutant |

| EGDdplcB | 1/2a | plcB | + | EGD plcB mutant |

| EGDInlB | 1/2a | inlB | + | EGD inlB mutant |

| L. innocua | ||||

| 11288pERL3 | 6a | Wild type | − | INN |

| 11288pERL3 | 6a | prfA hly | ++ | INN+ |

Hemolytic phenotypes observed on sheep blood agar plates were scored as follows: ++, strongly hemolytic; +, weakly hemolytic; −, nonhemolytic.

Purification of LLO.

LLO was purified from L. innocua strain ATCC 11288 harboring the plasmid INN3prfAhly (INN+), which produces 512-fold-more LLO than the L. monocytogenes wild-type (EGD) strain (7). Briefly, supernatant fluids from exponentially growing bacteria were concentrated 20-fold by using a Millipore filtration apparatus. The supernatant was first batch absorbed with Q-Sepharose, and the nonabsorbed fraction was recovered by centrifugation. This fraction was then loaded onto a Mono S HR5/5 column and eluted with a linear gradient of 50 to 500 mM NaCl with 40 mM phophate buffer, pH 5.0. LLO eluted as a sharp peak at 200 to 260 mM NaCl. Following dialysis against phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2, LLO was stored at −70°C. Purified LLO migrated as a 58-kDa band in sodium dodecyl sulfate-Coomassie-stained gels and was judged to be >95% pure.

Preparation of endothelial cells.

Endothelial cells were obtained from human umbilical veins according to the method described by Jaffe et al (16). Briefly, cells obtained from collagenase digestion were washed, pooled, centrifuged for 10 min at 210 × g, and resuspended in fresh culture medium with 20% FCS and antibiotics (penicillin, 100 U/ml; streptomycin, 100 μg/ml; and amphotericin B, 2 μg/ml). Before splitting, cells were grown for 2 to 3 days on T25 culture flasks coated with gelatin. Cells were harvested after trypsin digestion, seeded into multiwells coated with gelatin, and grown in an atmosphere of 95% O2 and 5% CO2 until reaching confluence within 3 to 5 days. The culture medium was exchanged every day, and homogeneity of the cultures was verified by morphological criteria and cell counting (approximately 300 cells per mm2).

Determination of NO by bioassay.

Guanosine 3′,5-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP) responses of RFL-6 rat fetal lung fibroblasts were employed to estimate the activity of liberated NO according to the method of Ishii et al. (15). Briefly, RFL-6 cells grown to confluence in 12-well tissue culture plates were washed and incubated with aliquots from supernatants obtained from stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC). Incubation was performed in the presence of the nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor isobutyl-methylxanthine over a period of 5 min. The cell reaction was terminated by aspiration of the medium and addition of 1 ml of ice-cold 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0). Samples were immediately frozen and stored at −70°C until radioimmunoassay for cGMP was performed. To minimize spontaneous NO decay, all experiments were performed in the presence of 100 U of superoxide dismutase per ml.

Cytokine immunoassays.

IL-8, IL-6, and GM-CSF were analyzed by using ELISAs. The detection limit of these ELISAs ranged up to <30 pg/ml.

Preparation of nuclear protein extracts.

At indicated time points following incubation, cells were washed in HBSS, scraped off, and collected by centrifugation (5 min at 300 × g). Pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of buffer A (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 10 mM KCL, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.5 mM phenyl methyl sulfonyl fluoride, as described in reference 32. After the suspension was incubated for 15 min on ice, Nonidet P-40 was added to give a final concentration of 0.5%, and the cells were vortexed for 3 min at 4°C. The cells were centrifuged (45 s at 18,000 × g), and nuclear pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of buffer C (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.4 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA) and vortexed for 30 min at 4°C. After centrifugation (5 min, at 18,000 × g) the supernatants, designated nuclear extracts, were frozen in aliquots at −80°C.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

After protein determination by BCA assay, 6 μg of nuclear protein was mixed with the labeled probe in a 20-μl volume containing 1 μg of poly (dI-dC), 2 μl of 5× binding buffer (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.8], 25 mM MgCl-2, 250 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50% glycerol, 25 mM dithiothreitol) as described in reference 32. The probes (2 μl total) used were double-stranded oligonucleotides with the sequence 5′-TGCACAGAGGGGACTTTCCGAGAGG-3′ containing the kB site from the mouse k light-chain enhancer. After 10 min at 20°C, the oligonucleotide-protein complexes were separated on native 6% polyacrylamide gels in low-ionic-strength buffer (0.25× Tris-borate-EDTA) at 200 V for 1 h at room temperature. After electrophoresis was performed, the gels were fixed, vacuum dried, and exposed to a phosphorus-imaging plate (BAS-MP 2040S). In competition studies, unlabeled oligonucleotides were included in the reaction mixtures in a 1- to 50-fold molar excess.

DAG and ceramide assay.

Cells and cell supernatant were extracted according to the method of Bligh and Dyer (4). The chloroform phase was removed and kept at −20°C to minimize acyl group migration, and both lipid mediators were quantified within 24 h by enzymatic conversion to [32P]phosphatidic acid and 32P-labeled ceramide as previously described (29). Briefly, an aliquot of the chloroform phase was evaporated under nitrogen, and the lipid film was solubilized in 20 μl of 7.5% octyl-β-d-glucoside, 5 mM cardiolipin, and 1 mM diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid by water bath sonication. The resulting micelles were then reacted with Escherichia coli sn-1,2-diacylglycerole kinase in the presence of 5 mM [γ-32P]ATP. After subsequent neutral lipid extraction, an aliquot of the lipid phase was subjected to thin-layer chromatography on a Silica Gel 60 F254 plate and developed with chloroform-methanol-acetic acid (65:15:5, vol/vol/vol). Identification of DAG and its separation from labeled ceramide phosphate were ascertained by autoradiography prior to liquid scintillation counting of the DAG spot. Samples of sn-1,2-diolein were carried out by the same procedure and spotted onto each plate as controls. Thereby, DAG and ceramide recovery and conversion were ascertained to range consistently above 85%. The amounts of sn-1,2-DAG and ceramide present in the original samples were calculated from the respective counts of phosphatidic acid and labeled ceramide phosphate and the specific activity of the ATP batch employed.

HUVEC-bacteria cocultures.

After overnight culture in BHI broth, 2 ml of the bacterial suspension was added to 10 ml of fresh BHI (in the presence of 5 μg of erythromycin per ml) and incubated at 37°C until it reached an optical density of 0.45 (photometrically assessed at 600 nm). Then, bacteria were spun at 3,000 × g and resuspended in 4 ml of HBSS (pH 7.4, in the absence of erythromycin). For experiments measuring endothelial NF-κB, culture plates with an area of 75 cm2 per well were used, and according to preceding pilot experiments, 200 μl of the bacterial suspension was admixed to the 9.8 ml of HBSS buffer (pH 7.4, in the absence of erythromycin). For experiments measuring endothelial NO, DAG, and ceramide (extraction of cells and cell supernatant), culture plates with an area of 9.6 cm2 per well were used, and 20 μl of the bacterial suspension was admixed to the 980 μl of HBSS buffer (pH 7.4, in the absence of erythromycin). Thus, approximately 2 × 105 bacteria were obtained in a 1-ml assay volume. The ratio of bacteria to endothelial cells was approximately 1:1. After various time periods, reactions were stopped by admixing either chloroform-methanol (1:2, vol/vol) (DAG and ceramide) or 70% ethanol (NO). For experiments measuring cytokines, culture plates with an area of 4 cm2 per well were employed, and 10 μl of the bacterial suspension was admixed to a final volume of 1 ml in medium containing 1% FCS. After incubation for 30 min, the medium was replaced by fresh medium containing gentamycin (50μg/ml). After treatment at indicated time periods, supernatant was removed and aliquots of each sample were collected and analyzed by ELISA. For experiments with D609 (5 μg/ml), 150 μmol of PDTC, or 30 μg of CAPE per ml, the endothelial cells were preincubated for 1.0 h.

Control experiments.

Microscopic examination of the endothelium-bacteria cocultures did not reveal any listerial uptake by HUVEC within 30 min of incubation for all strains investigated. Lactic dehydrogenase release, as one indicator of cellular damage from the endothelial cells, was <2% of total enzyme activity in the absence of bacteria (control), 3.0% ± 3% for EGD, and 3.6% ± 5% for INN+ (30-min incubation periods; n = 4 each), as compared to the total release by the pore-forming agent mellitin (100 μg/ml).

Statistics.

For statistical comparison, one-way analysis of variance was performed. A level of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Impact of L. monocytogenes on inflammatory mediator release from HUVEC. (i) NO.

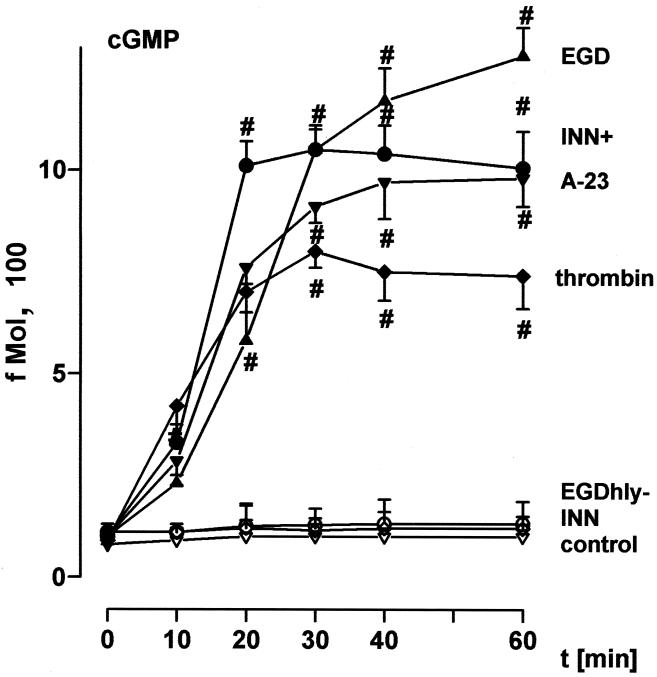

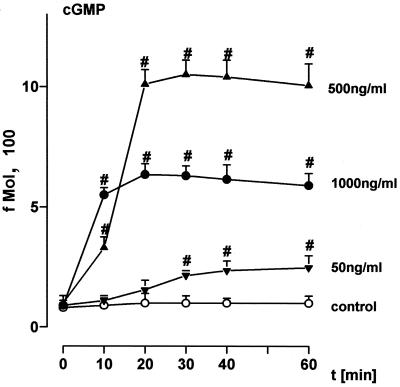

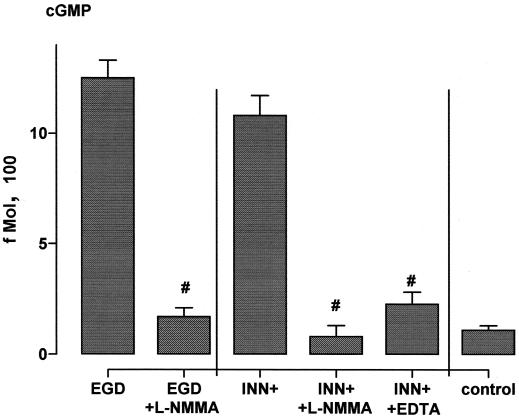

Incubation of HUVEC with EGD caused rapid-onset liberation of substantial quantities of the short-lived vasodilatory agent NO, as assessed by induction of cGMP synthesis (Fig. 1), exceeding that in response to optimum concentrations of the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 and to receptor occupancy by ligands such as thrombin. In contrast, the deletion mutant defective in the pore-forming listeriolysin O (EGD hly mutant) as well as the nonpathogenic L. innocua strain (INN) were entirely ineffective. The NO response was reproduced by an L. innocua strain (INN+) which had been engineered to produce high levels of listeriolysin as well as by purified listeriolysin (LLO) in a dose-dependent manner, with 500 ng of LLO per ml displaying the highest efficacy (Fig. 1 and 2). Pretreatment of HUVEC with 10 μM NG-momo-methyl-l-arginine citrate (l-NMMA), an NO antagonist, reduced the NO release in response to EGD and INN+ to <15% (Fig. 3). HUVEC stimulation with 1 μg of LLO per ml in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (in the presence of EDTA) suppressed the NO synthesis to ≈20% compared to the controls in the presence of Ca2+.

FIG. 1.

Time course of NO formation in response to various bacterial strains. HUVEC were incubated with EGD, the EGD hly mutant, INN+, or INN (2 × 105 bacteria each). For comparison, stimulation was performed with thrombin (0.1 U/ml) or A23187 (1 μM); controls were sham incubated. NO release into the supernatant was quantified as fibroblast cGMP content as given in Materials and Methods. Bacterial strains added directly to fibroblasts did not induce cGMP activity. #, significantly different from INN. Means ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) of five independent experiments are given.

FIG. 2.

Impact of LLO on endothelial NO formation. EC were incubated with different concentrations of LLO for various time points. Controls were sham incubated. NO release into the supernatant was quantified as fibroblast cGMP content as given in Materials and Methods. LLO added directly to fibroblasts did not induce cGMP activity. #, significantly different from control. Means ± SEM of four independent experiments are given.

FIG. 3.

Impact of l-NMMA and EDTA on endothelial NO formation. HUVEC were incubated with EGD or INN+ in the presence and absence of l-NMMA (10 μM) for 45 min; EDTA (500 μM, in the absence of extracellular Ca++) was additionally employed in the case of INN+ NO release into the supernatant was quantified as fibroblast cGMP content as given in Materials and Methods. #, significantly different from EGD and INN+, respectively. Means ± SEM of four independent experiments are given.

(ii) IL-8, IL-6, and GM-CSF.

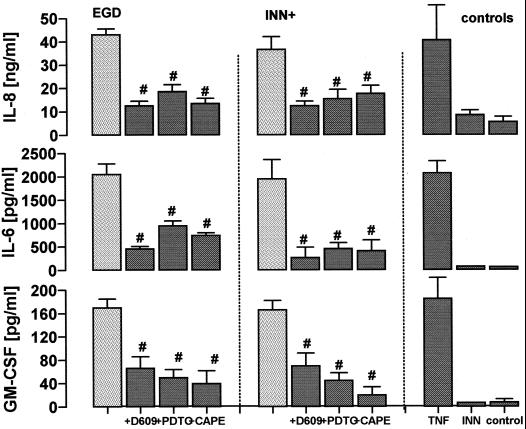

Coincubation of HUVEC with EGD and listeriolysin producing INN+ caused a highly significant accumulation of IL-8, IL-6, and GM-CSF within 24 h (Fig. 4). These responses were reproduced by purified LLO in a dose-dependent manner (Table 2). Total amounts of the respective mediators did, however, show great differences, ranging from ≈50 ng/ml (IL-8), ≈2,200 pg/ml (Il-6), to ≈170 pg/ml (GM-CSF) within 24 h. This inflammatory mediator release, provoked by a EGD/EC ratio of 20:1, was in the same range as the response provoked by optimum quantities of tumor necrosis factor (TNF).

FIG. 4.

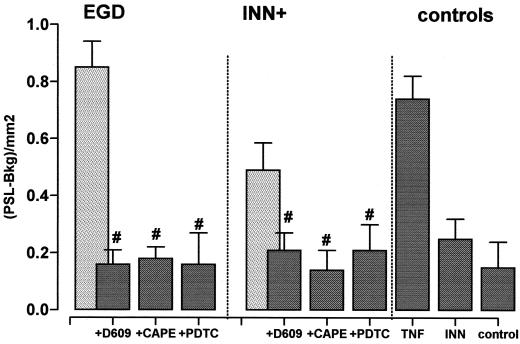

Influence of 5 μg of D609 per ml, 150 μM PDTC, and 30 μg of CAPE per ml on endothelial cytokine release. HUVEC were pretreated with the respective inhibitors for 30 min and exposed to EGD or INN+ (IL-6 and IL-8, t = 12 h; GM-CSF, t = 24 h). TNF (10 ng/ml) stimulation was performed for comparison; controls were sham incubated. Release of IL-8, IL-6, and GM-CSF into the supernatant was quantified by ELISA. #, significantly different from EGD or INN+ stimulation in the absence of inhibition. Means ± SEM of four independent experiments each are given.

TABLE 2.

Impact of LLO and various bacterial strains on endothelial cytokine release and nuclear presence of NF-κBa

| Strain or mutation | IL-8 (ng/ml) | IL-6 (pg/ml) | GM-CSF (pg/ml) | NF-κB (PSL-Bkg/mm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGD | 43 ± 3 | 2,100 ± 225 | 175 ± 17 | 0.85 ± 0.09 |

| EGD hly | 16 ± 3∗ | 493 ± 98∗ | 43 ± 13∗ | 0.36 ± 0.09∗ |

| EGD plcB | 40 ± 2.5 | 1,950 ± 150 | 171 ± 11 | 0.61 ± 0.06∗ |

| EGD plcA | 42 ± 4 | 2,150 ± 265 | 185 ± 20 | 0.64 ± 0.11∗ |

| EGD nlB | 29 ± 5 | 2,250 ± 185 | 180 ± 15 | 0.45 ± 0.12∗ |

| Control | 3 ± 1 | 105 ± 51 | 11 ± 8 | |

| LLO (50ng/ml) | 7 ± 3 | 490 ± 75# | 47 ± 8# | |

| LLO (500ng/ml) | 34 ± 4# | 1,650 ± 124# | 121 ± 18# | |

| LLO (5μg/ml) | 29 ± 6 | 1,522 ± 243 | 135 ± 24 |

HUVEC were incubated with different concentrations of LLO, EGD, or EGDhly, EGDplcB, EGDplcA, or EGD inlB mutants. IL-8, IL-6, and GM-CSF release into the supernatant was quantified by ELISA (incubation period = 12 h). Preparation of nuclear protein extracts and EMSAs were carried out as given described in Materials and Methods (incubation period = 2 h). #, significantly different from control; ∗, significantly different from EGD. Means ± SEM of four independent experiments each are given.

Impact of DAG and NF-κB on cytokine release in HUVEC exposed to L. monocytogenes.

HUVEC, preincubated with the NF-κB inhibitors PDTC and CAPE, failed to liberate substantial amounts of IL-8, IL-6, and GM-CSF in response to both EGD and INN+. A corresponding inhibitory capacity was noted for the PC-PLC inhibitor D609 (Fig. 4).

The EGD-evoked responses were obviously independent of both listerial phospholipases C and internalin B, as the deletion mutants defective in the respective agents were as effective as wild-type EGD (Table 2). In contrast, the LLO-negative EGD hly strain failed to liberate substantial amounts of these mediators.

Mechanisms of L. monocytogenes-induced NF-κB activation in HUVEC.

Coincubation of HUVEC with wild-type EGD provoked a marked nuclear shift of NF-κB (Fig. 5), comparable to that observed for TNF. Correspondingly, treatment with INN+ caused a more prominent shift of NF-κB than INN; however, INN+ did not fully reproduce the response to EGD (≈65%).

FIG. 5.

Influence of D609 (5 μg/ml), 150 μM PDTC, and CAPE (30 μg/ml) on nuclear shift of NF-κB in response to EGD and INN+. HUVEC were pretreated with the respective inhibitors for 30 min and exposed to EGD or INN+ (t = 120 min). The preparation of nuclear protein extracts and EMSAs were carried out as given in Materials and Methods. Data are given as photostimulated-luminescence minus background (PSL-Bkg). TNF (10 ng/ml) stimulation was performed for comparison. Control values for D609, PDTC, and CAPE were 0.05 ± 0.08, 0.23 ± 0.11, and 0.21 ± 0.12, respectively. #, significantly different from EGD and INN+, respectively. Means ± SEM of five independent experiments each are given.

Preincubation of endothelial cells with the NF-κB inhibitors PDTC and CAPE markedly reduced the nuclear shift of NF-κB in response to both EGD and INN+. Accordingly, HUVEC preincubated with D609, an inhibitor of endothelial phosphatidylcholine-phospholipase C, failed to liberate substantial amounts of NF-κB in response to both strains.

To probe the role of DAG generated in response to listerial phospholipases C in the EGD-induced activation of NF-κB, we employed the EGD deletion mutants EGD plcA and EGD plcB. Incubation of HUVEC with both strains elicited about 80% of the EGD-evoked NF-κB response (Table 2).

By using deletion mutants lacking inlB or hly, the EGD-evoked response was reduced to ≈50 and ≈40%, respectively (Table 2).

Effect of L. monocytogenes on DAG and ceramide generation in HUVEC.

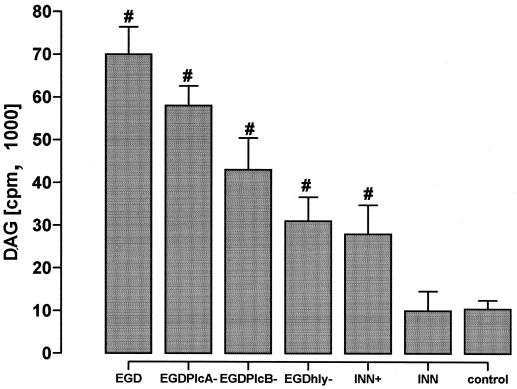

Incubation of HUVEC with wild-type L. monocytogenes induced a marked increase in DAG secretion within 30 min (Fig. 6). Corresponding to the listeria-evoked NF-κB response, maximum DAG generation required the presence of both PlcA, PlcB, and LLO. The LLO-producing recombinant INN+ reproduced the EGD-evoked response to only a minor extent. In parallel to DAG, wild-type EGD increased HUVEC ceramide generation by 12.9% ± 2% above that of controls.

FIG. 6.

Effect of various listerial strains on DAG generation. HUVEC were incubated with EGD, or the EGD plcA, EGD plcB, or EGD hly mutant, or INN+, or INN for 30 min. DAG formation is expressed as incorporation of labeled ATP. #, significantly different from INN. Means ± SEM of five independent experiments each are given.

DISCUSSION

The present study, performed with human endothelium, corroborates previous data (17) in showing that pore-forming L. monocytogenes LLO provokes marked upregulation of NF-κB activation and related proinflammatory cytokine (IL-8) synthesis; moreover, it adds NO, IL-6, and GM-CSF to the list of listeria-evoked vasoactive and inflammatory compounds. Transmembrane Ca2+ flux provoked by LLO may underlie the NO response, and a sequence of DAG generation (mostly via endogenous and not listerial phospholipase C activities), ceramide appearance, and related NF-κB activation is suggested to be operative in inducing cytokine upregulation. Cumulative evidence suggests that the LLO-evoked mediator generation does not need the genes required for the expression of PlcA, PlcB, or InlB.

The activation of HUVEC occurred without listerial uptake by the endothelial cells. First, in all studies with wild-type L. monocytogenes addressing prolonged effects on endothelial cells, gentamycin was admixed to the medium after 30 min for bacterial killing. It is known from previous studies (28) and was presently ascertained by random microscopic controls that a 30-min incubation time is insufficient for invasion of human endothelial cells by wild-type EGD. Second, the L. innocua strain engineered to produce LLO (INN+), which is incapable of invading endothelial and epithelial cells, as well as exogenously administered purified LLO, reproduced NO and cytokine synthesis as well as DAG and NF-κB signaling events. Third, the EGD hly mutant, which is fully competent for cell invasion but defective for LLO synthesis, did not induce any substantial NO liberation and cytokine generation. Fourth, additional studies performed with wild-type L. monocytogenes in the presence of 150 ng of cytochalasin D per ml, a microfilament disrupter which blocks listerial internalization without interfering with the binding of the bacteria to the endothelial cells (10), demonstrated unrestricted endothelial NO and cytokine formation as well as nuclear translocation of NF-κB (data not shown). And fifth, the EGD inlB mutant, which is fully competent for LLO synthesis but defective for invasion of HUVEC (28), did not induce any substantial cytokine release.

HUVEC-EGD coincubation resulted in pronounced NO synthesis, plateauing after 20 to 30 min, the kinetics of which corresponded to that in A23187- or thrombin-stimulated endothelial cells, with even higher efficacy for maximum NO liberation than these standard stimuli. This response is largely attributable to listerial LLO liberation, as the isogenic in-frame deletion mutant for LLO (EGD hly mutant) was entirely ineffective, whereas the avirulent L. innocua strain (INN+), engineered to produce LLO as a sole virulence factor and purified LLO reproduced the NO release response. Strict dependency on extracellular Ca2+ was noted. This finding is reminiscent of previous studies of the pore-forming agent staphylococcal alpha-toxin, which was found to be operative by an extra-intracellular Ca2+ shift (presumably via the hydrophilic channels within the toxin-created transmembrane pore), thereby eliciting Ca2+-dependent intracellular events (13, 34, 35, 41–44, 47). Interestingly, and again in line with previous studies of alpha-toxin-elicited cellular responses, the optimum concentration of LLO ranged below the highest concentration employed, indicating that substantial pore-formation, but not overt cell lysis, in still-viable cells represents the precondition for maximum NO provocation by LLO. It is conceivable that an extra-intracellular Ca2+ shift will result in an activation of the constitutive Ca2+-calmodulin dependent endothelial NO synthase, as similarly assumed for stimulation with the calcium ionophore A234187. As anticipated, NO liberation was virtually blocked in the presence of the NO synthesis inhibitor l-NMMA.

In addition to NO, sustained and dose-dependent liberation of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and GM-CSF was noted in HUVEC-EGD cocultures, with time course and extent of the cytokine response corresponding well to that in endothelial cells exposed to the potent standard stimulus TNF. Again, LLO was identified as the listerial virulence factor largely responsible for the upregulation of cytokine synthesis. First, the deletion mutant EGD hly was markedly less effective than EGD, although not fully ineffective, in eliciting the cytokine response. Second, cytokine synthesis was reproduced by INN+, engineered to liberate LLO as a sole virulence factor, but not by INN. Third, the response was reproduced by purified LLO. And fourth, the isogenic in-frame deletion mutants for PlcA, PlcB, and InlB were not hampered in their facility to provoke maximum IL-6, IL-8, and GM-CSF release. The strict LLO dependency of the endothelial cytokine response to listerial challenge contrasts with the finding in many macrophages or macrophage-like cell lines that the L. monocytogenes-elicited upregulation of cytokines is independent of virulence factors, as it is similarly forwarded by the avirulent mutants lacking prfA or hly and even by L. innocua, thus suggesting triggering by bacterial wall component(s) common to all Listeria spp. (20). It is, however, reminiscent of studies in mice spleen cells including NK cells, in which the induction of proinflammatory cytokine gene expression was largely ascribed to listerial LLO production (26).

The signaling events underlying the prolonged cytokine upregulation in the endothelial cells in contact with L. monocytogenes are apparently more complex than those suggested for LLO-elicited early NO generation. The current data favor a sequence of (endogenous) phospholipase C-dependent DAG formation, ceramide appearance, and nuclear translocation of NF-κB for transcriptional activation of the cytokine genes. DAG has been suggested to activate the acidic sphingomyelinase with liberation of ceramide (3, 32). Ceramide-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB is well established for many cell types, presumably proceeding via a ceramide-activated protein kinase or I-κB kinase, leading to the degradation of the NF-κB inhibitor I-κB (2). Inducibility of the genes encoding for the cytokines IL-8, IL-6, and GM-CSF requires NF-κB binding to positive regulatory domains in the respective promoter regions (23, 24). The hypothesis that a sequence of Plc-elicited DAG generation, ceramide appearance, and related NF-κB activation is operative in inducing cytokine upregulation in the L. monocytogenes-exposed endothelial cells is supported by the following findings in the current study. (i) Wild-type L. monocytogenes and INN+ provoked DAG accumulation, which significantly surpassed that in the INN controls. The coappearance of DAG and inositol phosphates, arising from phosphatidylinositol (PI)Plc activity, was previously reported for human endothelial cells in response to listerial challenge (37). (ii) Marked ceramide appearance was noted in the experiments with HUVEC-EGD coincubation. The time course of endothelial accumulation of this second messenger in response to L. monocytogenes was recently analyzed in more detail, demonstrating a progressive increase in ceramide levels over a 6-h observation period (33). (iii) Strong NF-κB activation was observed in the endothelial cells coincubated with wild-type L. monocytogenes, corresponding to that in response to potent standard stimuli TNF. The nuclear translocation of NF-κB was partly reproduced by INN+, but not INN. These data are well in line with previous studies of endothelial cells responding to listerial challenge, in which the nuclear shift of NF-κB was directly demonstrated by fluorescence microscopy (8) and in which the impact of NF-κB activation on gene transcription was monitored by a reporter gene assay (33). (iv) NF-κB activation in response to wild-type L. monocytogenes and the upregulation of all cytokines investigated was strongly reduced by D609, an agent inhibiting PC-Plc activity (15). Inhibitory capacity of D609 was similarly demonstrated for INN+-provoked NF-κB activation, indicating that this pharmacological approach targeted endothelial phospholipase C, as INN+ does not possess any listerial Plc. (v) All cytokine liberation, both in response to EGD and INN+, was largely suppressed by two inhibitors of NF-κB activation, PDTC and CAPE, which directly interfere with the phosphorylation and translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus (24, 25).

Notwithstanding these data strongly supporting a sequence of Plc-dependent DAG formation, ceramide appearance, and subsequent nuclear translocation of NF-κB, several aspects of the endothelial cytokine response to listerial challenge are currently not fully settled. First, the role of the listerial phospholipases C, PlcA and PlcB, is uncertain. In preceding studies of HUVEC, these phospholipases were noted to synergize with LLO in eliciting phosphoinositide metabolism and DAG formation (37), as well as ceramide appearance and NF-κB activation (33). This notion is supported by the current finding that the isogenic deletion mutants EGD plcA and EGD plcB were somewhat less effective than EGD in eliciting DAG formation and NF-κB activation, although they were fully active in provoking cytokine upregulation. It is open for speculation whether compartmentalization of listerial or endothelial Plc-elicited phospholipid cleavage with impact on downstream signaling events underlies this finding or whether a saturation phenomenon is involved (with maximum possible cytokine upregulation already achieved by activation of the endogenous signal transduction pathway). Second, the link between LLO membrane attack and the activation of endothelial PC-Plc (as suggested by the efficacy of D609) and PI-Plc (as suggested by the previously demonstrated appearance of inositol phosphates [9]) has not yet been elucidated. As the activity of PC-Plc is critically dependent on Ca2+ (27), the LLO-dependent transmembrane Ca2+ flux might again be operative, as discussed for NO synthesis, not excluding additional signal transduction steps between LLO membrane incorporation and activation of endothelial phospholipase(s) C. And third, the putative link between DAG and ceramide generation (via sphingomyelinases) and the detailed mechanisms of downstream NF-κB activation remain to be elucidated in further experimental studies.

Focusing on the sequence of listerial LLO, endothelial Plc activation, and NF-κB translocation for cytokine upregulation does not exclude the contribution of additional signaling mechanisms. Internalin B was recently shown to be required for the process of listerial adhesion and entry into HUVEC (28), and the currently noted reduction of NF-κB activation upon use of the InlB-defective mutant might suggest a role of this adhesive molecule in establishing close EGD-HUVEC contact with impact on the efficacy of listerial LLO release. Moreover, a putative role of the PI-3-kinase pathway, noted to be of major importance in epithelial cells exposed to listerial challenge (14), has not yet been addressed for endothelial cells. Furthermore, the Raf–MEK–mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway, known to be activated in several tissue culture cell lines in response to L. monocytogenes infection (45), might additionally contribute to the upregulation of endothelial cytokine synthesis. It is of interest, and well in line with the presently described role of LLO, that studies of cultured HeLa cells identified extracellularly released listeriolysin as the bacterial factor responsible for mitogen-activated protein kinase activation, related to the pore-forming capacity of this agent (46).

We conclude that the ability of L. monocytogenes to provoke strong proinflammatory mediator generation in human endothelial cells does not depend on listerial cell invasion but is centrally linked to the presentation of listeriolysin as predominant virulence factor. Early NO synthesis may be triggered via LLO-dependent transmembrane Ca2+ flux. The sustained upregulation of proinflammatory cytokine (IL-6, IL-8, and GM-CSF) synthesis is suggested to proceed via activation of endothelial phospholipase(s) C, DAG generation, ceramide appearance, and related nuclear translocation of NF-κB. Such endothelial mediator generation in response to L. monocytogenes adhesion with extracellular LLO presentation may well contribute to systemic inflammatory responses and vasoregulatory abnormalities under conditions of severe listerial infection and sepsis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, grant 547.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akira S, Hirano T, Taga T, Kishimoto T. Biology of multifunctional cytokines: IL 6 and related molecules (IL 1 and TNF) FASEB J. 1990;4:2860–2867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baeuerle P A, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballou L R, Laulederkind S J, Rosloniec E F, Raghow R. Ceramide signalling and the immune response. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;130:273–287. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(96)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bligh E G, Dyer W J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:753–757. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakraborty T, Leimeister-Wächter M, Domann E, Hartl M, Goebel W, Nichterlein T, Notermens S. Coordinate regulation of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes requires the product of the prfA gene. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:568–574. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.568-574.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conlan J W, North R J. Neutrophils are essential for early anti-Listeria defense in the liver, but not in the spleen or peritoneal cavity, as revealed by a granulocyte-depleting monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1994;179:259–268. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darji A, Chakraborty T, Niebuhr K, Tsonis N, Wehland J, Weiss S. Hyperexpression of listeriolysin in the nonpathogenic species Listeria innocua and high yield purification. J Biotechnol. 1995;43:205–212. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(95)00138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drevets D A. Listeria monocytogenes infection of cultured endothelial cells stimulates neutrophil adhesion and adhesion molecule expression. J Immunol. 1997;158:5305–5313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drevets D A, Sawyer R T, Potter T A, Campbell P A. Listeria monocytogenes infects human endothelial cells by two distinct mechanisms. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4268–4276. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4268-4276.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drevets D A. Listeria monocytogenes virulence factors that stimulate endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:232–238. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.232-238.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gellin B G, Broome C V. Listeriosis. JAMA. 1989;261:1313–1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldfine H, Johnston N C, Knob C. Nonspecific phospholipase C of Listeria monocytogenes: activity on phospholipids in Triton X-100-mixed micelles and in biological membranes. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4298–4306. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.14.4298-4306.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimminger F, Rose F, Sibelius U, Meinhardt M, Potzsch B, Spriestersbach R, Bhakdi S, Suttorp N, Seeger W. Human endothelial cell activation and mediator release in response to the bacterial exotoxins Escherichia coli hemolysin and staphylococcal alpha-toxin. J Immunol. 1997;159:1909–1916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ireton K, Payrastre B, Chap H, Ogawa W, Sakaue H, Kasuga M, Cossart P. A role for phosphoinositide 3-kinase in bacterial invasion. Science. 1996;274:780–782. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishii K, Sheng H, Warner T D, Förstermann U, Murad F. A simple and sensitive bioassay method for detection of EDRF with RFL-6 rat lung fibroblasts. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:H598–H603. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.2.H598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaffe E A, Nachman R L, Becker C G, Minick C R. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. J Clin Investig. 1973;52:2745–2756. doi: 10.1172/JCI107470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kayal S, Lilienbaum A, Poyart C, Memet S, Israel A, Berche P. Listeriolysin O-dependent activation of endothelial cells during infection with Listeria monocytogenes: activation of NF-κB and upregulation of adhesion molecules and chemokines. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1709–1722. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kilbourn R G, Gross S S, Jubran A, Adams J, Griffith Q W, Levi R, Lodato R F. N-methyl-l-argine inhibits tumor necrosis factor-induced hypotension: implication for the involvement of nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3629–3632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhl S J, Rosen H. Nitric oxide and septic shock. From bench to bedside. West J Med. 1998;168:176–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuhn M, Goebel W. Host cell signalling during Listeria monocytogenes infection. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:11–15. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leimeister-Wächter M, Chakraborty T. Detection of listeriolysin, the thiol-dependent hemolysin in Listeria monocytogenes, Listeria ivanovii, and Listeria seeligeri. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2350–2357. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.8.2350-2357.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayers I, Johnson D. The nonspecific inflammatory response to injury. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45:871–879. doi: 10.1007/BF03012222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukaida N, Mahe Y, Matsushima K. Cooperative interaction of nuclear factor-kappa B- and cis-regulatory enhancer binding protein-like factor binding elements in activating the interleukin-8 gene by pro-inflammatory cytokines. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:21128–21133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munoz C, Salcedo D P, del Carmen Castellanos M, Alfranca A, Aragones J, Vara A, Redondo J M, de Landazuri M O. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate inhibits the production of interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by human endothelial cells in response to inflammatory mediators: modulation of NF-kappa B and AP-1 transcription factors activity. Blood. 1996;88:3482–3490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Natarajan K, Singh S, Burke T R, Grunberger D, Aggawal B B. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester is a potent and specific inhibitor of activation of NF kappa B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9090–9095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishibori T, Xiong H, Kawamura I, Arakawa M, Mitsuyama M. Induction of cytokine gene expression by listeriolysin O and roles of macrophages and NK cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3188–3195. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3188-3195.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nord E P. Signalling pathways activated by endothelin stimulation of renal cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1996;23:331–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb02833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parida S K, Domann E, Rohde M, Muller S, Darji A, Hain T, Wehland J, Chakraborty T. Internalin B is essential for adhesion and mediates the invasion of Listeria monocytogenes into human endothelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:81–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Preiss J, Loomis C R, Bishop W R, Stein R, Niedel J E, Bell R M. Quantitative measurement of sn-1,2-diacylglycerols present in platelets, hepatocytes, and ras- and sis-transformed normal rat kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:8597–8600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rakhmilevich A L. Neutrophils are essential for resolution of primary and secondary infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:827–831. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.6.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schall T J, Bacon K B. Chemokines, leukocyte trafficking, and inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:865–873. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schütze S, Potthoff K, Machleidt T, Berkovic D, Wiegmann K, Krönke M. TNF activates NF-kappa B by phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C-induced “acidic” sphingomyelin breakdown. Cell. 1992;71:765–776. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90553-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwarzer N, Nöst R, Seibold J, Parida S K, Fuhrmann O, Krüll M, Schmidt R, Newton R, Hippenstiel S, Dohmann E, Chakraborty T, Suttorp N. Two distinct phospholipases C of Listeria monocytogenes induce ceramide generation, nuclear factor B activation, and E-selectin expression in human endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:3010–3018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seeger W, Bauer M, Bhakdi S. Staphylococcal alpha-toxin elicits hypertension in isolated rabbit lungs: evidence for thromboxane formation and the role of extracellular calcium. J Clin Investig. 1984;74:849–858. doi: 10.1172/JCI111502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seeger W, Birkemeyer R G, Ermert L, Suttorp N, Bhakdi S, Duncker H R. Staphylococcal alpha-toxin-induced vascular leakage in isolated perfused rabbit lungs. Lab Investig. 1990;63:341–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sibelius U, Rose F, Chakraborty T, Darji A, Wehland J, Weiss S, Seeger W, Grimminger F. Listeriolysin is a potent inductor of the phosphatidylinositol response and lipid mediator generation in human endothelial cells Infect. Immun. 1996;64:674–676. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.674-676.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sibelius U, Chakraborty T, Krogel B, Wolf J, Rose F, Schmidt R, Wehland J, Seeger W, Grimminger F. The listerial exotoxins listeriolysin and phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C synergize to elicit endothelial cell phosphoinositide metabolism. J Immunol. 1996;157:4055–4060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sibelius U, Schulz E C, Rose F, Hattar K, Jacobs T, Weiss S, Chakraborty T, Seeger W, Grimminger F. Role of Listeria monocytogenes exotoxins listeriolysin and phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C in activation of human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1125–1130. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1125-1130.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith G A, Marquis H, Jones S, Johnston N C, Portnoy D A, Goldfine H. The two distinct phospholipases C of Listeria monocytogenes have overlapping roles in escape from a vacuole and cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4231–4237. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4231-4237.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Splawski J B, McAnally L M, Lipsky P E. IL-2 dependence of the promotion of human B cell differentiation by IL-6 (BSF-2) J Immunol. 1990;144:562–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suttorp N, Habben E. Effect of staphylococcal alpha-toxin on intracellular Ca2+ in polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2228–2234. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.9.2228-2234.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suttorp N, Fuhrmann M, Tannert-Otto S, Grimminger F, Bhakdi S. Pore-forming bacterial toxins potently induce release of nitric oxide in porcine endothelial cells. J Exp Med. 1993;178:337–341. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suttorp N, Seeger W, Dewein E, Bhakdi S, Roka L. Staphylococcal alpha-toxin induced PGI2 production in endothelial cells: role of calcium. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:C127–C134. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1985.248.1.C127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suttorp N, Seeger W, Zucker-Raimann J, Roka L, Bhakdi S. Mechanisms of leukotriene generation in polymorphonuclear leukocytes by staphylococcal alpha-toxin. Infect Immun. 1987;55:104–110. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.104-110.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang P, Rosenshine I, Finlay B B. Listeria monocytogenes, an invasive bacterium, stimulates MAP kinase upon attachment to epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:455–464. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.4.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tang P, Rosenshine I, Cossart P, Finlay B B. Listeriolysin O activates mitogen-activated protein kinase in eucaryotic cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2359–2361. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2359-2361.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valeva A, Palmer M, Bhakdi S. Staphylococcal alpha-toxin: formation of the heptameric pore is partially cooperative and proceeds through multiple intermediate stages. Biochemistry. 1997;43:13298–13304. doi: 10.1021/bi971075r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J M, Chen Z G, Colella S, Bonilla M A, Welte K, Bordignon C, Mantovani A. Chemotactic activity of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 1988;72:1456–1460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]