PURPOSE:

The effects of COVID-19 have been understudied in rural areas. This study sought to (1) identify cancer screening barriers and facilitators during the pandemic in rural and urban primary care practices, (2) describe implementation strategies to support cancer screening, and (3) provide recommendations.

METHODS:

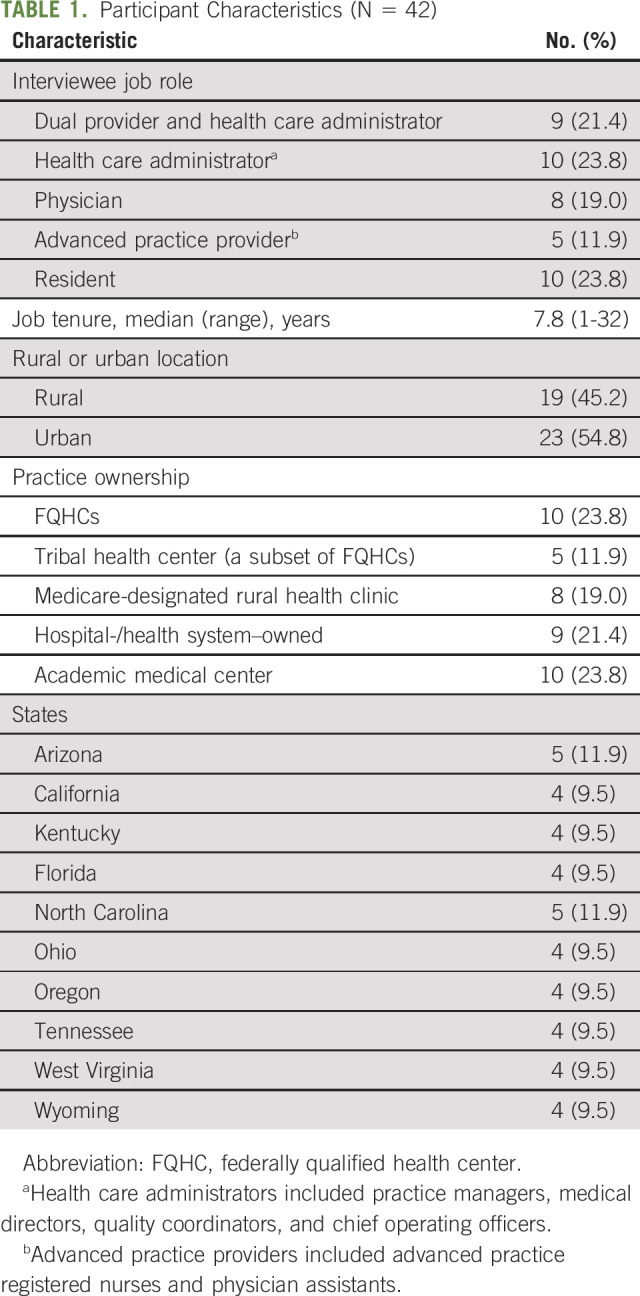

A qualitative study was conducted (N = 42) with primary care staff across 20 sites. Individual interviews were conducted through videoconference from August 2020 to April 2021 and recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using deductive and inductive coding (hybrid approach) in NVivo 12 Plus. Practices included federally qualified health centers, tribal health centers, rural health clinics, hospital/health system–owned clinics, and academic medical centers across 10 states including urban (55%) and rural (45%) sites. Staff included individuals serving in the dual role of health care provider and administrator (21.4%), health care administrator (23.8%), physician (19.0%), advanced practice provider (11.9%), or resident (23.8%). The interviews assessed perceptions about cancer screening barriers and facilitators, implementation strategies, and future recommendations.

RESULTS:

Participants reported multilevel barriers to cancer screening including policy-level (eg, elective procedure delays), organizational (eg, backlogs), and individual (eg, patient cancellation). Several facilitators to screening were noted, such as home-based testing, using telehealth, and strong partnerships with referral sites. Practices used strategies to encourage screening, such as incentivizing patients and providers and expanding outreach. Rural clinics reported challenges with backlogs, staffing, telehealth implementation, and patient outreach.

CONCLUSION:

Primary care staff used innovative strategies during the pandemic to promote cancer screening. Unresolved challenges (eg, backlogs and inability to implement telehealth) disproportionately affected rural clinics.

INTRODUCTION

Individuals in rural areas are more likely to die from preventable cancers, a disparity that has increased over time.1-3 Rural-urban cancer disparities stem from multilevel factors, such as individual risk behavior, health care provider availability, and differences in screening.4-12 Rural residents are less likely to receive screening for breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer.13-17 Rural primary care practices have notable barriers to delivering cancer screening, such as insufficient electronic health record (EHR) capacity for reminder and recall systems and staffing shortages.18,19 New barriers to cancer screening were created by the pandemic, creating a need for research on COVID-19–related effects on cancer screening in rural clinics.

The effects of COVID-19 are understudied in rural areas.20 Available studies suggest that risk for COVID-19–related hospitalization and mortality is higher in rural areas because of population differences—rural areas have more residents over age 65 years and with chronic conditions.21 Furthermore, rural areas have lower COVID-19 vaccination rates, heightening risk for COVID-19–related morbidity and mortality.22 Initial studies suggest that rural residents were also more likely to miss cancer screening during the pandemic.23,24 A qualitative study reported that rural clinics in Kentucky experienced staff shortages, which negatively affected cancer screening.25 Since that study, there has been limited examination of how cancer screening has been affected in other rural areas of the United States.

To address this gap, this qualitative study has three objectives: (1) identify cancer screening barriers and facilitators during the COVID-19 pandemic in rural and urban primary care clinics, (2) describe implementation strategies to support cancer screening, and (3) provide recommendations for cancer screening. Findings can inform future policies and interventions to ensure that cancer screening delivery remains a priority during the pandemic and that rural-urban disparities are not exacerbated.

METHODS

Participants and Recruitment

We selected the top 25 states with the greatest representation of rural health clinics on the basis of data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.26 We reached out to the state community health associations for permission to present at a meeting and/or send a recruitment e-mail to a statewide listserv. Of the 25 associations contacted, 10 agreed to participate, 13 did not respond, and two cited concerns about lack of time. Among the 10 states that agreed to participate, we used two additional recruitment strategies, including e-mail outreach through residency programs and snowball sampling. We aimed for 4-5 practices per state, and within each practice, we aimed for at least one member of the clinic team (eg, physician) and one health care administrator. Participants received a $50 US dollars gift card.

Interviews

Two qualitative research specialists (B.L.A. and M.N.C.) conducted 30-minute (mean: 31.06; range: 24.31-35.10 minutes), semistructured interviews from August 2020 to April 2021. The interview guide assessed barriers, facilitators, and implementation strategies for cancer screening during COVID-19 and recommendations (Data Supplement, online only). Cancer screening was defined as screening endorsed by the US Preventive Services Taskforce (colorectal, breast, cervical, lung, prostate, and skin). The interviews were conducted via Zoom (San Jose, CA), audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Study participants provided informed consent before the interview. This study was determined to be exempt by Moffitt Cancer Center's Institutional Review Board of record (Advarra, Columbia, MD).

Qualitative Analyses

A hybrid approach to thematic analyses, which combines deductive and inductive coding, was used.27,28 The research team reviewed a subset of transcripts and developed a codebook to define a priori codes on the basis of the interview guide and posteriori codes on the basis of themes from the data (Data Supplement). We used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to organize the themes regarding barriers and facilitators across three domains: (1) factors external to the organization, (2) factors within the organization, and (3) individual characteristics that may affect implementation.29 We used the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change to categorize themes regarding implementation strategies across four domains: (1) education strategies (eg, making stakeholders aware of screening changes), (2) restructure strategies (eg, changing physical structures to support screening changes), (3) plan strategies (eg, building buy-in and relationships necessary to enact changes), and (4) financial strategies (eg, incentivizing screening changes).30 The transcripts were coded by two independent coders using NVivo 12 Plus (Burlington, MA) until a high level of inter-rater reliability (k = .83) was reached.31 The remaining transcripts were divided among the two coders. Additional details regarding coding are provided in the Data Supplement. Within themes, we assessed similarities and differences across rural and urban practices. We followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies checklist to report study findings.32 Illustrative quotations are presented in the tables.

RESULTS

Participants

The sample (N = 42) included individuals serving as both a health care administrator and a provider (21.4%), a health care administrator (23.8%), a physician (19.0%), an advanced practice provider (11.9%), or a resident (23.8%; Table 1). Practices included 45.2% of rural and 54.8% of urban clinics across 10 states. Practice types included federally qualified health centers (23.8%), tribal health centers (a subset of federally qualified health centers; 11.9%), Medicare-designated rural health clinics (19.0%), hospital-/health system–owned clinics (21.4%), and academic medical centers (23.8%). There were 2-3 participants per practice (n = 20 practices).

TABLE 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 42)

Cancer Screening Barriers

External barriers.

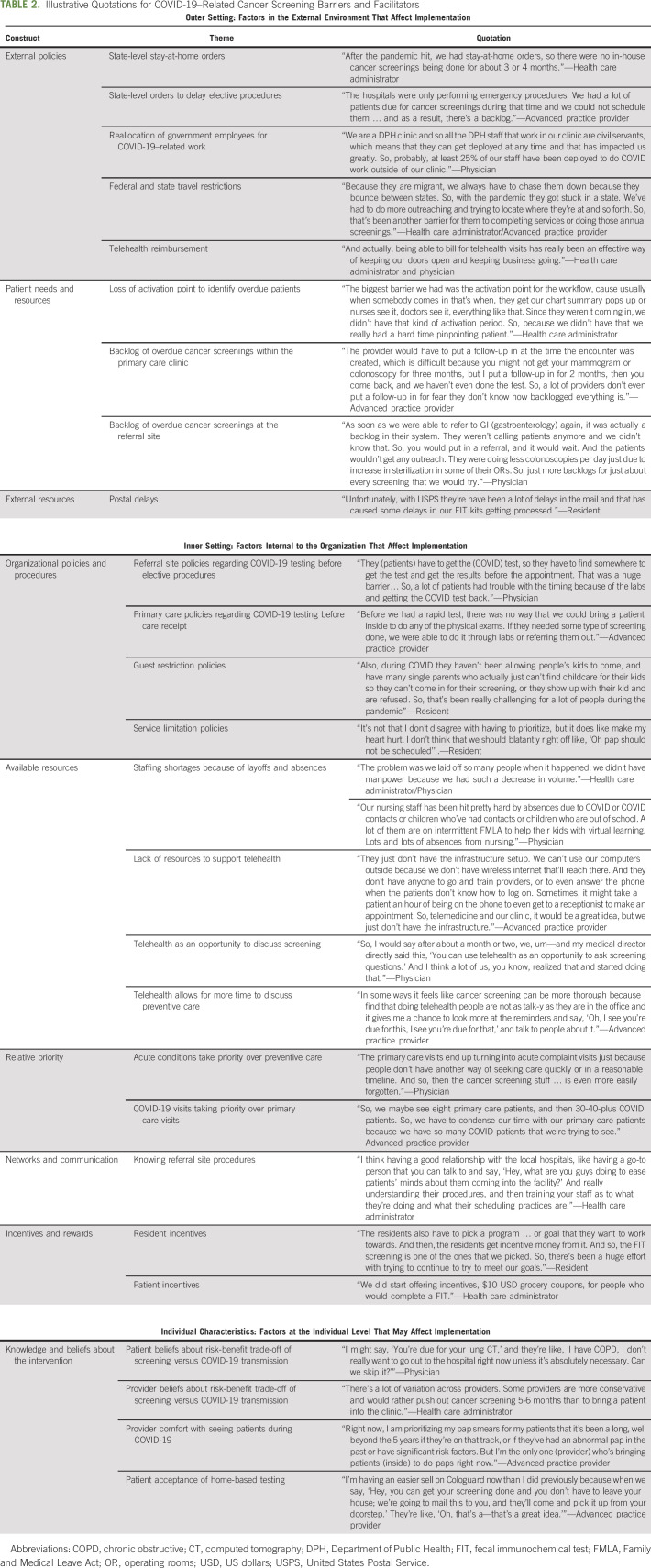

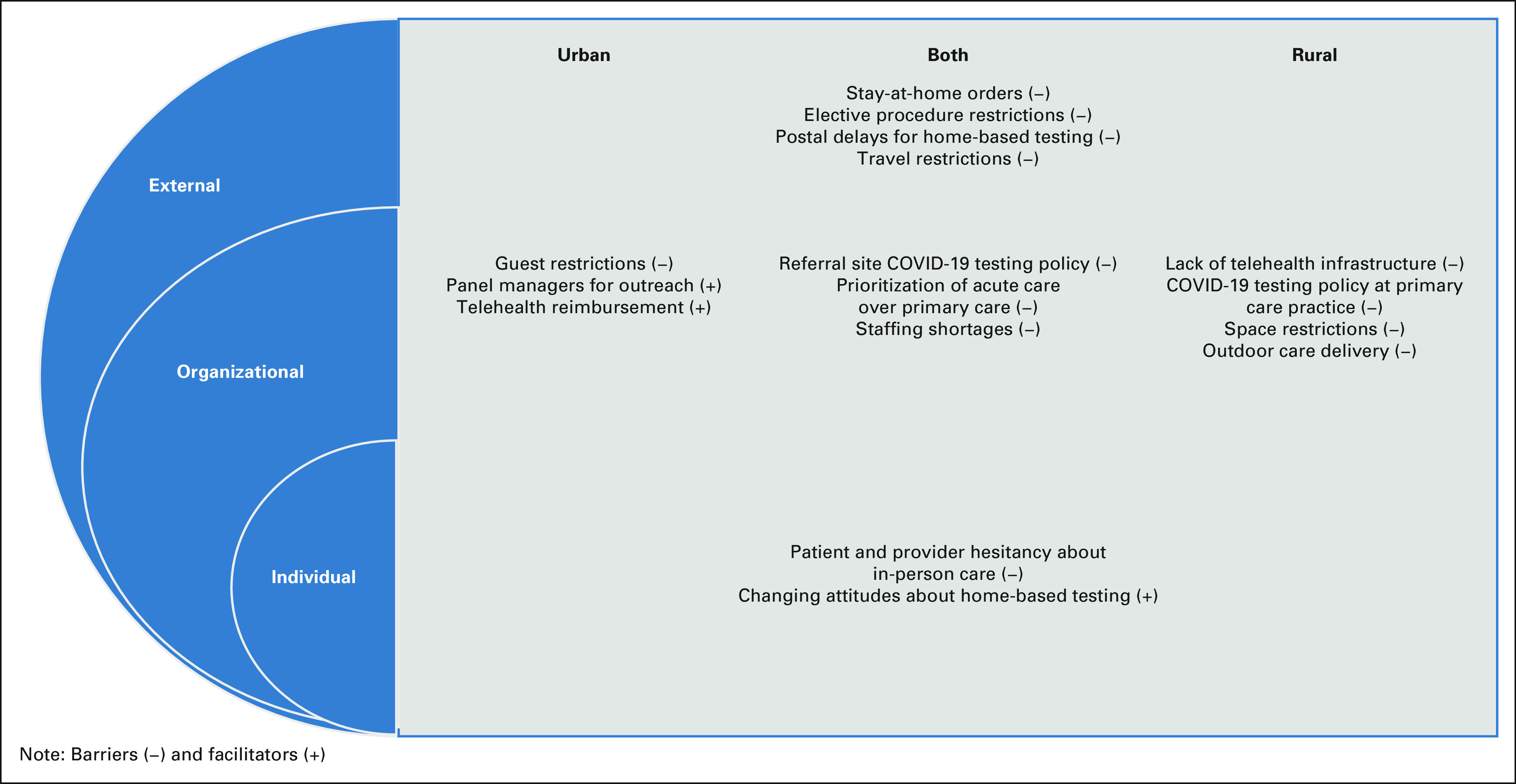

Participants described external-level, organizational-level, and individual-level barriers that affected cancer screening during the pandemic (Table 2). External factors, such as stay-at-home orders, caused cancer screening to be suspended. Most clinics (30 of 42) resumed services within 1-3 months; the remaining clinics (12 of 42) delayed screening for 4-8 months. Rural clinics were more likely to delay cancer screening for a longer period because of limited personal protective equipment (PPE). Federal and state travel restrictions negatively affected cancer screening among migrant populations. State-level delays in elective procedures caused certain services (eg, colonoscopy) to be suspended. All clinics reported that elective procedures were resumed within 1-3 months. Some participants (22 of 42) noted external barriers to home-based testing, such as postal service mail delays and lack of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for human papillomavirus (HPV) self-sampling. Barriers to home-based testing were similar across rural and urban sites (Fig 1).

TABLE 2.

Illustrative Quotations for COVID-19–Related Cancer Screening Barriers and Facilitators

FIG 1.

Rural and urban cancer screening barriers and facilitators during the pandemic.

Organizational barriers.

Organizational policies and available resources were cited as barriers to cancer screening (Table 2). A third of participants (14 of 42) indicated that referral sites (eg, gastroenterologists) required COVID-19 testing before elective procedures could be performed. This led to appointment cancellations for two reasons: (1) the patient did not want to receive the test or (2) or the test results were not available in time for the procedure—a problem in rural and urban areas. A few rural practices (n = 4) also required COVID-19 testing before patients could receive care. The practices cited lack of PPE as the motivating factor. Some urban clinics (10 of 42) instituted guest restriction policies that prevented patients from bringing children to visits, resulting in appointment cancellations. A few (3 of 42) participants described how some patients would arrive with children for a screening visit and be refused service.

COVID-19 affected resources, such as staffing, and created competing priorities (eg, prioritizing acute care over screening). All participants described staff shortages because of layoffs, having staff reassigned to work on COVID-19, and COVID-19–related absences. Some participants (12 of 42) described how resource constraints (eg, lack of staff) made it difficult to implement telehealth. Lack of telehealth made it difficult for some clinics to have a touchpoint with the patient to deliver cancer screening reminders since patients were not coming into the clinic. Rural clinics had more difficulty with telehealth implementation because of lack of infrastructure (eg, lack of Wi-Fi throughout the facility). Some participants (19 of 42) described how the increase in COVID-19–related visits decreased provider availability for primary care visits, causing care delays. This was more common among rural clinics. Some rural clinics (7 of 42) described having insufficient clinic space and PPE, making it necessary to deliver health care outdoors for 4-6 months. This led these clinics to use home-based testing for colorectal cancer (CRC) and to delay other services (eg, cervical cancer screening) that could not be performed outdoors.

Individual barriers.

All participants described how patients were hesitant to visit a health care facility during COVID-19, especially referral sites (eg, radiology) that may be in a hospital setting. Some participants (20 of 42) described how patients at risk for COVID-19 (eg, patients with diabetes and older adults) were more likely to be hesitant about accessing health care during COVID-19. Some participants (18 of 42) felt that providers were fearful of COVID-19 transmission—either that a patient would get COVID-19 or that the provider would get COVID-19—and delayed cancer screening, and other nonacute visits for as long as possible. Individual-level barriers did not vary across rural and urban sites.

Cancer Screening Facilitators

Participants identified factors that facilitated cancer screening during COVID-19 (Table 2). Many participants (30 of 42) felt that telehealth gave providers an opportunity to discuss cancer screening at a time when in-person visits had ceased. Some participants (16 of 42) felt that telehealth visits were more efficient compared with in-person visits, making it easier to discuss cancer screening. Several participants (17 of 42) discussed how reimbursement for phone visits was particularly valuable for engaging patients with limited internet access or digital literacy. Viewing telehealth as a facilitator for cancer screening was more common among urban clinics. Urban clinics that had panel managers (n = 19) described how these staff members were a critical component for maintaining outreach for overdue cancer screening during the pandemic. About half of participants (20 of 42) felt that home-based testing was valuable for maintaining cancer screening during COVID-19 and that patients were more willing to use home-based testing, such as the fecal immunochemical test, because of COVID-19. Views about home-based testing did not differ across urban and rural sites.

Cancer Screening Implementation Strategies

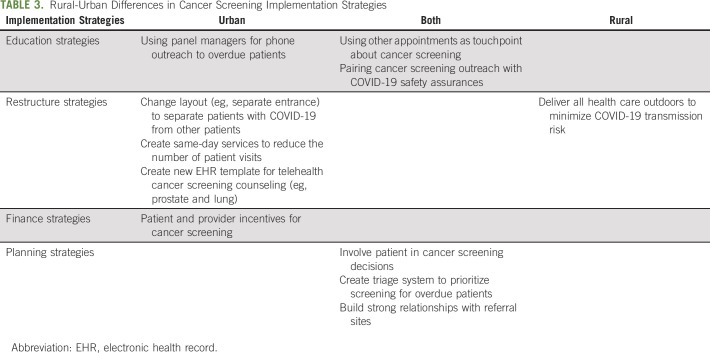

Educational strategies.

Participants implemented educational strategies to increase cancer screening during COVID-19 (Data Supplement). Many participants (22 of 42) used other appointment types (eg, COVID-19 prescreening calls) as a touch point to remind patients about cancer screening. Some individuals (n = 18) described implementing more proactive outreach strategies, such as calling patients with overdue cancer screening, rather than relying on mailing strategies given patient hesitancy for accessing health care during the pandemic. Participants described the importance of pairing cancer screening outreach with education around COVID-19 safety precautions. Adding additional outreach was more common among urban clinics. Most rural clinics (16 of 19) cited wanting to do more outreach but not having sufficient staffing (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Rural-Urban Differences in Cancer Screening Implementation Strategies

Restructuring strategies.

Urban practices restructured their clinics' layout and workflow for cancer screening because of COVID-19. Some urban clinics (12 of 42) created separate entrances for healthy patients scheduled for routine procedures (eg, allowing patients to enter a side door). Some urban clinics (8 of 42) created same-day services for cancer screening (eg, mammogram) to minimize patient visits to the health care system. Urban clinics developed new EHR templates to deliver as much of a cancer screening visit virtually as possible (eg, shared decision making for prostate cancer screening), with only the laboratory visit occurring in person. Restructuring strategies were not used by rural clinics.

Financial strategies.

Health care systems developed financial incentives to support cancer screening during COVID-19. Some (11 of 42) clinics used patient-level incentives (e.g., gift card) to increase uptake, whereas other clinics (9 of 42) incentivized staff (e.g., resident incentive program) to increase cancer screening uptake. Incentives were not used in rural clinics.

Planning strategies.

Clinics used planning strategies, such as involving patients in decision making, developing tailored approaches for high-risk patients, and building partnerships. About half of participants (21 of 42) described the importance of involving patients in cancer screening decision making during COVID-19 and discussing factors, such as individual-level risk for COVID-19 and cancer and the clinics' strategies for minimizing COVID-19 transmission. Some individuals (10 of 42) developed systems to identify high-risk patients who were overdue for screening (eg, prior abnormal pap test results) and prioritize outreach to those patients. Some sites (15 of 42) described that a triage system was needed for prioritizing patients for screening, but clinics lacked information to develop a triage system (eg, smoking status in the EHR). Nearly all participants (37 of 42) described building strong relationships with referral sites to learn about how COVID-19 was being handled (eg, precautions and scheduling) and then training primary care staff on those procedures so they could disseminate that information to patients. Strategies were similar across rural and urban clinics.

Recommendations

Participants provided five recommendations: (1) increased provider and patient education, (2) public health campaigns, (3) expanded home-based testing, (4) addressing social determinants of health, and (5) developing same-day and comprehensive cancer clinics (Data Supplement). Most individuals (31 of 42) recommended strengthening patient education to highlight the importance of cancer screening and provide assurance that the health care system is taking every precaution to reduce COVID-19 transmission risk. Some participants (19 of 42) recommended provider education about the importance of cancer screening during COVID-19. Several participants (16 of 42) felt that public health campaigns were needed to stress the importance of cancer screening during COVID-19. Most participants (35 of 42) recommended expanding home-based testing and speeding up FDA approval for HPV self-sampling. Some participants (13 of 42) recommended restructuring the clinic to allow patients to come in for cancer screening while limiting interaction with sick patients (eg, same-day clinics, weekend/evening clinics, and comprehensive screening clinics). Finally, most participants (31 of 42) highlighted the need for addressing the social determinants of health that continue to affect cancer screening. The most cited determinants were childcare, transportation, digital literacy, lack of internet access, and inadequate health care coverage. Most barriers stemmed from financial barriers (eg, inability to pay for childcare). One exception was digital literacy, which was mentioned to be a barrier for some older patients. These barriers were similar across urban and rural sites. Furthermore, we did not observe differences in recommendations across rural and urban clinics.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to assess rural and urban primary care practices' experiences with cancer screening during the pandemic. Multilevel barriers affected cancer screening, such as state and organizational policies, available resources, and patient and provider beliefs about COVID-19. Rural clinics might have experienced more barriers to screening because of staff shortages, limited telehealth capability, and lack of PPE. There were also factors that facilitated cancer screening during the pandemic, such as increased patient acceptability of home-based testing and using telehealth as an opportunity to promote screening. Practices used innovative strategies to deliver screening during COVID-19, such as restructuring the clinic layout and using financial incentives. Participants also offered important suggestions for optimizing cancer screening during the pandemic, such as expanding home-based testing.

Similar to prepandemic studies, our study found that telehealth implementation was more challenging for rural clinics.33-35 Rural clinics were more likely than urban clinics to describe barriers such as lack of staff support, clinic internet access issues (eg, limited Wi-Fi availability), provider comfort with technology, and patient digital literacy and internet access. As a result, many rural clinics were unable to leverage telehealth as an opportunity to promote cancer screening. During the pandemic, many policy measures were implemented (eg, increased funding)36 or proposed (eg, improved broadband infrastructure) to expand rural telehealth.37 Additional policy initiatives may be needed to support rural telehealth implementation, such as technical assistance programs for program start-up. Telehealth has been used successfully to promote cancer screening, such as delivering shared decision making for lung cancer screening or promoting CRC screening for high-risk patients.38-40 Additional studies are needed to test and disseminate telehealth approaches to screening, particularly in rural clinics.

Our findings suggest that home-based testing was used by urban and rural clinics and recommended as a strategy for expanding cancer screening. Previous studies have demonstrated that home-based testing for CRC can be particularly effective for reducing rural screening disparities.41,42 Similar to our work, other studies have noted challenges with home-based testing, such as adequate patient instruction and tailoring outreach to patient preferences.43,44 Rural clinics cited challenges with patient outreach for cancer screening because of limited staffing, suggesting that less time-intensive strategies are needed to deliver home-based testing. Studies have tested technology-based outreach strategies, such as text messaging, artificial intelligence, and patient portals, which might aid in supporting outreach for home-based testing models—particularly for understaffed clinics.45-48 Study participants also recommended FDA approval of HPV self-testing and cited growing patient demand for home-based testing as a key reason.

Across all clinics, social determinants of health, such as lack of childcare, persisted as barriers to cancer screening. Some participants identified policies that have been helpful for addressing social determinants of health, such as reimbursement of phone visits.49 Similar to previous studies, participants mentioned that phone visits are more accessible among populations affected by the digital divide (eg, individual with a limited income) than video visits.50-52 Participants suggested strategies to increase the convenience of screening as a way to overcome social determinants of health (eg, evening or weekend clinics, same-day clinics, and comprehensive screening clinics), which have demonstrated promise.53 Policies are also needed to close cancer screening coverage gaps (eg, full Medicare coverage for diagnostic colonoscopies).54,55 Providers will also play a key role in addressing screening gaps by communicating the importance of screening during the pandemic.

Our study has a few limitations. First, we interviewed staff after the first wave of the pandemic had passed to ensure that staff would have time to participate. As a result, our results may under-represent some of the barriers encountered early on during the pandemic. Second, we selected a subsample of 10 states on the basis of the concentration of rural clinics, and therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to other states. Third, our interview guide was based upon the consolidated framework for implementation research,29 which assesses multilevel barriers and facilitators to implementation (breadth of barriers). As such, our interview guide did not go into depth about certain barriers to cancer screening (eg, health beliefs). Additional research is needed to explore barriers in greater depth (eg, health care avoidance because of COVID-19–related fears). In addition, we did not have any a priori hypotheses about how clinician characteristics (eg, sex) would affect cancer screening experiences and did not collect this information. Future studies might consider whether primary care providers' experiences with cancer screening vary on the basis of demographics.

In conclusion, in response to COVID-19, primary care practices developed innovative ways to maintain screening during the pandemic. Our findings suggest that strategies, such as leveraging telehealth and home-based testing for screening, should be expanded in the future. Furthermore, our study suggests that the pandemic might have disproportionately affected cancer screening in rural areas. Additional strategies are needed to ensure that cancer screening remains a priority during the pandemic and that rural-urban disparities are not exacerbated.

Carley Geiss

Employment: HCA Healthcare (I)

Susan Vadaparampil

Speakers' Bureau: GlaxoSmithKline (I), Bristol Myers Squibb/Medarex (I)

Usha Menon

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Abcodia

Research Funding: Abcodia (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent No.: EP10178345.4 for Breast Cancer Diagnostics

Uncompensated Relationships: ILOF (Inst), Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Inst), RNA Guardian (Inst), Micronoma (Inst)

Amir Alishahi

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Surgalign Holdings Inc, Cortexyme Inc

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

Supported by the University of South Florida Anna Valentine-Charles Oehler Foundation and the Participant Research, Interventions, and Measurements Core Facility at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, an NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Karim Hanna, Usha Menon, Kea Turner

Administrative support: Amir Alishahi Tabriz, Kea Turner

Collection and assembly of data: Karim Hanna, Melody N. Chavez, Amir Alishahi Tabriz, Kea Turner

Data analysis and interpretation: Karim Hanna, Brandy L. Arredondo, Melody N. Chavez, Carley Geiss, Emma Hume, Laura Szalacha, Shannon M. Christy, Susan Vadaparampil, Jessica Islam, Young-Rock Hong, Jennifer Kue

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Cancer Screening Among Rural and Urban Clinics During COVID-19: A Multistate Qualitative Study

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Carley Geiss

Employment: HCA Healthcare (I)

Susan Vadaparampil

Speakers' Bureau: GlaxoSmithKline (I), Bristol Myers Squibb/Medarex (I)

Usha Menon

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Abcodia

Research Funding: Abcodia (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent No.: EP10178345.4 for Breast Cancer Diagnostics

Uncompensated Relationships: ILOF (Inst), Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Inst), RNA Guardian (Inst), Micronoma (Inst)

Amir Alishahi

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Surgalign Holdings Inc, Cortexyme Inc

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blake KD, Moss JL, Gaysynsky A, et al. : Making the case for investment in rural cancer control: An analysis of rural cancer incidence, mortality, and funding trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 26:992-997, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia MC, Faul M, Massetti G, et al. : Reducing potentially excess deaths from the five leading causes of death in the rural United States. MMWR Surveill Summ 66:1-7, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moy E, Garcia MC, Bastian B, et al. : Leading causes of death in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan areas—United States, 1999-2014. MMWR Surveill Summ 66:1-8, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yabroff KR, Han X, Zhao J, et al. : Rural cancer disparities in the United States: A multilevel framework to improve access to care and patient outcomes. JCO Oncol Pract 16:409-413, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henley SJ, Jemal A: Rural cancer control: Bridging the chasm in geographic health inequity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 27:1248-1251, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sauer AG, Siegel RL, Jemal A, et al. : Updated review of prevalence of major risk factors and use of screening tests for cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 26:1192-1208, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts ME, Doogan NJ, Kurti AN, et al. : Rural tobacco use across the United States: How rural and urban areas differ, broken down by census regions and divisions. Health Place 39:153-159, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaufman BG, Thomas SR, Randolph RK, et al. : The rising rate of rural hospital closures. J Rural Health 32:35-43, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Celaya MO, Rees JR, Gibson JJ, et al. : Travel distance and season of diagnosis affect treatment choices for women with early-stage breast cancer in a predominantly rural population (United States). Cancer Causes Control 17:851-856, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Punglia RS, Weeks JC, Neville BA, et al. : Effect of distance to radiation treatment facility on use of radiation therapy after mastectomy in elderly women. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 66:56-63, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes AG, Watanabe-Galloway S, Schnell P, et al. : Rural-urban differences in colorectal cancer screening barriers in Nebraska. J Community Health 40:1065-1074, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Germack HD, Kandrack R, Martsolf GR: When rural hospitals close, the physician workforce goes. Health Aff (Millwood) 38:2086-2094, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole AM, Jackson JE, Doescher M: Urban-rural disparities in colorectal cancer screening: Cross-sectional analysis of 1998-2005 data from the Centers for Disease Control's Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Study. Cancer Med 1:350-356, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horner-Johnson W, Dobbertin K, Iezzoni LI: Disparities in receipt of breast and cervical cancer screening for rural women age 18 to 64 with disabilities. Womens Health Issues 25:246-253, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran L, Tran P: US urban-rural disparities in breast cancer-screening practices at the national, regional, and state level, 2012-2016. Cancer Causes Control 30:1045-1055, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rohatgi KW, Marx CM, Lewis-Thames MW, et al. : Urban-rural disparities in access to low-dose computed tomography lung cancer screening in Missouri and Illinois. Prev Chronic Dis 17:E140, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obertová Z, Hodgson F, Scott-Jones J, et al. : Rural-urban differences in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening and its outcomes in New Zealand. J Rural Health 32:56-62, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenwasser LA, McCall-Hosenfeld JS, Weisman CS, et al. : Barriers to colorectal cancer screening among women in rural central Pennsylvania: Primary care physicians' perspective. Rural Remote Health 13:2504, 2013 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zoellner J, Porter K, Thatcher E, et al. : A multilevel approach to understand the context and potential solutions for low colorectal cancer (CRC) screening rates in rural appalachia clinics. J Rural Health 37:585–601, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters DJ: Community susceptibility and resiliency to COVID-19 across the rural-urban continuum in the United States. J Rural Health 36:446-456, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaufman BG, Whitaker R, Pink G, et al. : Half of rural residents at high risk of serious illness due to COVID-19, creating stress on rural hospitals. J Rural Health 36:584-590, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Souch JM, Cossman JS: A commentary on rural-urban disparities in COVID-19 testing rates per 100,000 and risk factors. J Rural Health 37:188-190, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amram O, Robison J, Amiri S, et al. : Socioeconomic and racial inequities in breast cancer screening during the COVID-19 pandemic in Washington state. JAMA Netw Open 4:e2110946, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeGroff A, Miller J, Sharma K, et al. : COVID-19 impact on screening test volume through the National Breast and Cervical Cancer early detection program, January-June 2020, in the United States. Prev Med 151:106559, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kruse-Diehr AJ, Dignan M, Cromo M, et al. : Building cancer prevention and control research capacity in rural appalachian Kentucky primary care clinics during COVID-19: Development and adaptation of a multilevel colorectal cancer screening project. J Cancer Educ 10.1007/s13187-021-01972-w [epub ahead of print on February 18, 2021] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.State Health Facts, Number of Medicare Certified Rural Health Clinics. Washington DC, KFF, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton AB, Finley EP: Qualitative methods in implementation research: An introduction. Psychiatry Res 280:112516, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E: Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 5:80-92, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. : Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 4:50, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, et al. : A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev 69:123-157, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hallgren KA: Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: An overview and tutorial. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol 8:23-34, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J: Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19:349-357, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin CC, Dievler A, Robbins C, et al. : Telehealth in health centers: Key adoption factors, barriers, and opportunities. Health Aff (Millwood) 37:1967-1974, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morenz AM, Wescott S, Mostaghimi A, et al. : Evaluation of barriers to telehealth programs and dermatological care for American Indian individuals in rural communities. JAMA Dermatol 155:899-905, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cortelyou-Ward K, Atkins DN, Noblin A, et al. : Navigating the digital divide: Barriers to telehealth in rural areas. J Health Care Poor Underserved 31:1546-1556, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stephenson J: Federal plan proposes improving rural health care through telehealth. JAMA Health Forum 1:e201186, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitehouse.gov : Updated Fact Sheet: Bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Washington, DC, The White House, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petraglia AF, Olazagasti JM, Strong A, et al. : Establishing satellite lung cancer screening sites with telehealth to address disparities between high-risk smokers and American College of Radiology-approved centers of designation. J Thorac Imaging 36:2-5, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kinney AY, Boonyasiriwat W, Walters ST, et al. : Telehealth personalized cancer risk communication to motivate colonoscopy in relatives of patients with colorectal cancer: The family CARE randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 32:654-662, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alishahi Tabriz A, Neslund-Dudas C, Turner K, et al. : How health-care organizations implement shared decision-making when it is required for reimbursement: The case of lung cancer screening. Chest 159:413-425, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Charlton ME, Mengeling MA, Halfdanarson TR, et al. : Evaluation of a home-based colorectal cancer screening intervention in a rural state. J Rural Health 30:322-332, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crosby RA, Stradtman L, Collins T, et al. : Community-based colorectal cancer screening in a rural population: Who returns fecal immunochemical test (FIT) kits? J Rural Health 33:371-374, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jaklevic MC: Pandemic spotlights in-home colon cancer screening tests. JAMA 10.1001/jama.2020.22466 [epub ahead of print on December 23, 2020] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balzora S, Issaka RB, Anyane-Yeboa A, et al. : Impact of COVID-19 on colorectal cancer disparities and the way forward. Gastrointest Endosc 92:946-950, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirst Y, Skrobanski H, Kerrison RS, et al. : Text-message reminders in colorectal cancer screening (TRICCS): A randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer 116:1408-1414, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muller CJ, Robinson RF, Smith JJ, et al. : Text message reminders increased colorectal cancer screening in a randomized trial with Alaska Native and American Indian people. Cancer 123:1382-1389, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hahn EE, Baecker A, Shen E, et al. : A patient portal-based commitment device to improve adherence with screening for colorectal cancer: A retrospective observational study. J Gen Intern Med 36:952-960, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zalake M, Tavasolli F, Griffin L, et al. : Internet-based tailored virtual human health intervention to promote colorectal cancer screening: Design guidelines from two user studies. Intell Virtual Agents 15:147-162, 2021 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.CMS : Medicare Telemedicine Health Care Provider Fact Sheet. Baltimore, MD, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodriguez JA, Clark CR, Bates DW: Digital health equity as a necessity in the 21st century cures act era. JAMA 323:2381-2382, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodriguez JA, Betancourt JR, Sequist TD, et al. : Differences in the use of telephone and video telemedicine visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Manag Care 27:21-26, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nguyen OT, Watson AK, Motwani K, et al. : Patient-level factors associated with utilization of telemedicine services from a free clinic during COVID-19. Telemed J E Health 28:526-534, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khalil S, Hatch L, Price CR, et al. : Addressing breast cancer screening disparities among uninsured and insured patients: A student-run free clinic initiative. J Community Health 45:501-505, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.ACS : Insurance Coverage for Colonoscopies. Atlanta, GA, American Cancer Society, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 55.ALS : State Lung Cancer Screening Toolkit. Tampa, FL, American Lung Society, 2021 [Google Scholar]