Abstract

The outbreak of COVID-19 has brought many challenges to youth development. During this specific period, adolescents have suffered from numerous behavioral problems, which will lead to more maladaptive consequences. It is necessary to explore several protective factors to prevent or reduce the occurrence of problem behaviors in adolescence. The current study combined school resources and self-control to evaluate the multiple protective effects on adolescents’ problematic behaviors in a two-wave longitudinal study. A sample of 789 Chinese adolescents (Mage = 14.00 years, SD = 2.05, 418 boys) were recruited via the random cluster sampling method to participate in the survey. The results confirmed the assumptions about the multiple protective effects of school resources and self-control on adolescents’ problem behaviors. Specifically, school resources could negatively predict IGD and victimization, and self-control mediated these associations. Moreover, one problematic behavior could also mediate the associations between self-control and another problematic behavior. This is the first study to focus on the multiple protective effects of positive factors on adolescents’ problem behaviors during the post-pandemic period, which has made several contributions to the literature and practice.

Keywords: School resources, Self-control, School bullying, School victimization, Internet gaming disorder, Chinese adolescents, COVID-19

Introduction

Since the first case of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) was detected, mankind has waged a protracted war against the virus. As of 18 May 2022, this war without gunpowder has lasted more than two years, plundering the lives of over six million people and the freedom of survivors (WHO, 2022). Although the outbreak of COVID-19 cannot halt individual growth, it indeed has multifactorial effects on human development, especially for young people. Previous studies have well documented that adolescents suffer from more mental disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety), more physical problems (e.g., neuroinflammation and neuroimmunoendocrine changes), as well as more behavioral problems (e.g., hyperactivity-inattention and emotional problems) during the lockdown period (De Miranda et al., 2020; De Figueiredo et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021a; Christner et al., 2021). In China, about 4.7 ~ 10.3% school-aged children have reported involvement in various behavioral problems during the pandemic (Liu et al., 2021a). Among the various behavioral problems, school bullying (both perpetration and victimization) and internet gaming disorder (IGD) are two common types. Recent studies have revealed that IGD and bullying not only enjoy high prevalence in Chinese adolescents but might persist for several years during adolescence (Li et al., 2019b; Liu et al., 2021b; Yu et al., 2022). If these problem behaviors are not intervened with effectively and immediately, they will lead to more maladaptive consequences such as academic failure, unemployment, and serious mental problems in the process of individual development (Reaves et al., 2018). Therefore, it is of vital importance to investigate protective factors that could assist young people to reduce or avoid involvement in problematic behaviors in the post-pandemic era and future.

Chain reactions in problem behaviors

Prior to the investigation into protective factors, it is necessary to note the developmental features of problematic behaviors. Empirically, individuals may experience more than one kind of problem behavior in the growth process, which implies that more attention should be paid to the interactions among problematic behaviors. The developmental cascade theory proposes that, in the process of individual growth, the development of different systems will affect each other, and the development of different factors in the same aspect will also affect each other, which highlights the spread effects among domains at the same level or across different systems (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010; Gan et al., 2021). As for school bullying and IGD, there might also be spread effects because they share the same behavioral system. Additionally, the problem behavior theory also indicates the interrelations among very diverse problem behaviors (Jessor, 1987; Wachs et al., 2021). Because these issues tend to share similar determinants, they can also be recognized as risk factors for each other. So, in the development of problematic behaviors, once an individual develops a problem behavior, he or she is more likely to engage in more problem behaviors if not timely and effectively intervened. Previous literature has provided consistent evidence to support the association between school bullying and IGD. For instance, Kim et al. (2017) demonstrated that IGD was a significant risk factor for school bullying among teenagers. In Chinese adolescents, previous studies have revealed those who are bullied by peers are more likely to engage in IGD (Liang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022). Moreover, Huang et al. (2021) confirmed the stability and variability of the role in school bullying, which implies that bullying experience and victimization experience could affect each other. Overall, there may be chain reactions between IGD, school bullying, and victimization. This multiple exposure to problem behaviors may have cumulative adverse effects on individual subsequent development. Hence, it is critical to take the chain reactions of problem behaviors into consideration in intervention or prevention research. According to the problem behavior theory, individuals’ problem behaviors are determined by the interactions between environmental system (e.g., school factors), personal system (e.g., traits and capabilities), and behavioral system (e.g., early involvement in problem behaviors) (Jessor, 1987). Based on this theory, the present study aims to investigate several protective factors from school and personal systems to prevent problem behaviors and their potential chain reactions.

School resources as a predictor

At the same time as entering puberty, Chinese students also begin to study in middle school, where they will spend a lot of time. Accordingly, the impact of school on individual growth becomes more direct and profound at this stage. So, it may be a practical and effective approach to explore positive factors in the school subsystem to guide adolescents to reduce or avoid developing problem behaviors. School resources, an emerging concept, refer to a set of positive factors from the school subsystem that promote individual development (Benson et al., 2011). A high level of school resources means that the school provides a caring and encouraging climate, clear rules and harmonious relationships, and adolescents actively participate in learning activities (Benson et al., 2011). According to the developmental assets theory, adolescents who obtain more school resources will develop more flourishing achievements and fewer harmful problems in the future (Scales et al., 2000). In the current issue, adolescents who experience more school resources may develop fewer problematic behaviors. Empirical studies have provided numerous indirect evidence on the association between school resources and problematic behaviors. For instance, a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies suggested that school climate was negatively associated with problem behaviors (Reaves et al., 2018). As for the teacher-student relationship, students who had less conflict and were more intimate with teachers reported less involvement in problematic behaviors (Pakarinen et al., 2018). Moreover, the higher level of school engagement could predict fewer problem behaviors among Chinese adolescents (Hu et al., 2019).

More specifically, school resources may be an effective predictor of IGD, school bullying, and victimization among adolescents. There are two theories that could contribute to the understanding of the complex linkage. First, Bandura (1978) claims in the social learning theory that individual behavioral outcomes are shaped by the environment. Adolescents may learn bullying behaviors through observation of aggressive behaviors at school. However, schools with diverse resources, such as an encouraging atmosphere, clear rules, and harmonious relations, will guide students to use non-violent approaches to cope with conflicts and spare no effects to prevent adolescents from exposure to aggressive behaviors. In this aspect, school resources are potential protectors for adolescents’ bullying behaviors, which has been repeatedly confirmed among Chinese adolescents in previous longitudinal studies. Teng and his colleagues (2020) revealed that students with more positive perceptions of school climate reported lower levels of bullying perpetration over time. As for victimization, Chen et al. (2021) suggested that adolescents who reported more engagement in school would be less exposed to violence in school and cyberspace. Moreover, Nie et al. (2021) demonstrated that perceptions of school climate mitigated the positive association between bullying and victimization.

Second, the general strain theory highlights that individuals may adopt maladaptive behaviors to alleviate negative emotions caused by environmental stress (Agnew, 1992). From this perspective, students in schools with tense atmospheres and discordant relationships will feel unhappy, unsupported, and anxious, and then they will develop maladaptive behaviors such as IGD to alleviate these negative feelings. On the contrary, if schools provide a comfortable environment and abundant resources, students may positively involve themselves in academic activities and achieve more. To a certain degree, schools providing more positive resources might play an important role in the prevention of IGD among students. Previous studies have indicated that adolescents who experience more school engagement, positive perceptions of school climate, and support from teachers and classmates are less likely to develop IGD (Yu et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2017; Zou et al., 2022). Furthermore, Xiang and his colleagues (2022a) revealed that developmental assets, including school resources, could negatively predict IGD half a year later in Chinese adolescents. Taken together, adolescents who experience more school resources may develop fewer problematic behaviors, including IGD, bullying, and victimization.

Self-control as a mediator

In addition to the effects of environmental factors, personal factors also influence human behavior (Bandura, 1978). As an essential personal capability, self-control is conceptulized as an individual’s ability to regulate thoughts, emotions, and behaviors to adapt to social norms, personal standards, and be in service of goals (Tangney et al., 2004). It is well documented that a high level of self-control ability not only contributes to multiple positive outcomes, including good adjustment, academic and work achievement, and interpersonal success, but also prevents negative outcomes such as mental and behavioral problems (Tangney et al., 2004; Li et al., 2015, 2021a; Sun et al., 2022). Moreover, self-control also plays a protective role in individual development during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, compared to those with low self-control, individuals with high self-control adhered more to the stay-at-home, social distancing, and mask-wearing guidelines in the COVID-19 outbreak (Tu et al., 2021; Xu & Cheng, 2021). Overall, self-control is an ability that plays a protective role in human development during ordinary times or emergencies. Accordingly, the present study chooses self-control as a personal factor to examine its effects on the associations between school resources, adolescents’ IGD, bullying, and victimization.

The school subsystem has profound effects on youth development, and the school environment is a critical context for individuals to nurture self-control ability (Li et al., 2021b). First, teachers set examples for students to observe how to control or regulate their behaviors and emotions, teach them specific knowledge and methods to cultivate and improve self-control, and supervise students to behave properly. Second, schools provide various disciplines and rules for students to correct misbehaviors on time and behave properly. Third, schools also provide a platform for students to put their self-control knowledge and approaches into practice and learn how to control their behaviors in order to build harmonious relationships with teachers and classmates. Fourth, schools could guide individuals to establish correct values through rewards and punishments, thereby forming internal monitoring standards of behaviors, which is also beneficial to self-control ability. Overall, one of the most important goals of the school is to guide individuals to develop self-discipline (Bear, 2010). Empirically, numerous facets in the school subsystem may play an effective role in cultivating self-control ability. A multilevel meta-analysis revealed that school discipline had a positive relationship with self-control ability from preschoolers to high school students (Li et al., 2021b). Moreover, longitudinal studies also indicated that school climate and teacher-student relations were significantly associated with self-control ability among adolescents (Li et al., 2021c; Dou et al., 2022).

As reviewed above, school resources significantly shape the developmental process of self-control ability, while this capacity could assist individuals to deal with the developmental challenges in various periods, such as the problematic behaviors during adolescence. The associations between self-control ability and problem behaviors may be further understood through the self-control theory (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990). According to the self-control theory, low self-control is a major reason for the vast majority of problematic behaviors (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990). People with low self-control are often unable to effectively control their impulses, resulting in adverse consequences, whereas those with high self-control ability can monitor and correct their behaviors at all times, largely avoiding the occurrence of problem behaviors. Furthermore, a growing number of studies have provided empirical evidence supporting the effects of self-control ability on adolescents’ problematic behaviors. In a longitudinal study, Jeong et al. (2020) suggested that Korean adolescents with low self-control would report greater severity of IGD features. In Chinese adolescents, Xiang et al. (2022b) also revealed a longitudinally negative association between self-control and IGD. For individuals with low self-control, compulsive and excessive use behaviors will easily occur in the process of playing online games, which will eventually lead them to IGD. With regard to school bullying, Cho and Lee (2021) demonstrated that low self-control is a significant predictor of both the initial levels and change in bullying behaviors among Korean youth. Similarly, Fenny (2021) also confirmed the negative association among Nigerian middle school students. As for victimization, a meta-analysis revealed that self-control is a consistent predictor of victimization (Pratt et al., 2014). Recently, Li et al. (2019a) also reported that self-control ability is related to reduced victimization among Polish adolescents. Considering the comprehensive relationships between school resources, self-control, and problematic behaviors, it is reasonable to assume that students who experience more school resources will develop a high level of self-control, thereby preventing them from involvement in IGD, bullying, and victimization.

Current study

Although scholars have obtained lots of achievements in understanding adolescents’ problematic behaviors, there are several research gaps in existing literature. First, previous studies have repeatedly investigated the cascading effects on various aspects of youth development. Zhang et al. (2020) revealed the chain reactions between neuroticism, depression, and cyberbullying. Similarly, Gan et al. (2021) also confirmed the cascading effects among parenting styles, depression, and IGD in Chinese adolescents. However, it is not difficult to find that these cascading effects are evaluated across various aspects, while the chain reactions at the different levels of one facet are neglected by previous research. As mentioned, IGD, bullying and victimization could coexist and affect each other. So, it is necessary to assess the interactions between these three types of problem behaviors. Second, prior research has detected numerous risk factors in order to prevent adolescents from developing problem behaviors by avoiding or reducing these risks. Existing studies have ignored the fact that young people indeed have positive traits to protect themselves, and the environment also provides many positive factors promoting individual growth (Scales et al., 2000). Moreover, little attention has been paid to the cumulative effects of diverse positive factors. To address these knowledge gaps, the present study, based on the problem behavior theory (Jessor, 1987), aims to evaluate the protective roles of school resources and self-control ability in adolescents’ problematic behaviors in the post-pandemic era. Considering the theoretical and empirical evidence on the associations between school resources, self-control, and problematic behaviors, the present study hypothesizes that (Fig. 1):

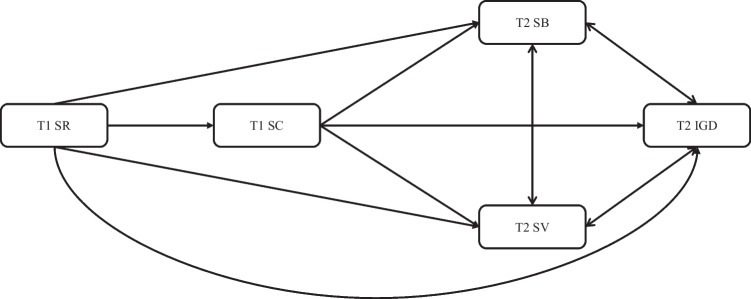

Fig. 1.

The conceptual model of the relationship between school resources and problematic behaviors. Note: SR = School resources; SC = Self-control; SB = School bullying; SV = School victimization; IGD = Internet gaming disorder; T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2

Hypothesis 1: School resources will positively predict self-control ability concurrently and longitudinally.

Hypothesis 2: School resources will negatively predict problematic behaviors concurrently and longitudinally.

Hypothesis 3: Self-control ability will mediate the relationship between school resources and problematic behaviors.

Hypothesis 4: One problematic behavior will mediate the relationship between school resources and other problematic behaviors.

Hypothesis 5: Self-control ability and one problematic behavior will sequentially mediate the relationship between school resources and other problematic behaviors.

Method

Participants and procedure

Using the random cluster sampling method, participants were recruited from one public middle school and one public high school in Hubei province, Central China. A sample of 789 students (Mage = 14.00 years, SD = 2.05, 418 boys) participated in the first data collection (T1: September, 2021) and completed self-reported questionnaires. 51 dropped out of the follow-up data collection (T2: January, 2022) for various reasons, such as absence. The final sample consisted of 738 adolescents and 70.05% of them were middle school students. Among the current sample, 50.65% were the only children in their families, and 95.44% were from families at or above the average economic level in the local cities. Moreover, Chi-square test and t-test reported that there were insignificant differences in gender (χ 2 (1) = 0.748, p = 0.387), T1 school resources (t (787) = -0.853, p = 0.394), T1 school bullying (t (52) = 1.261, p = 0.213), T1 school victimization (t (52) = 1.687, p = 0.098), and T1 IGD (t (53) = 1.833, p = 0.072) between the final sample and the lost sample, which indicated that the current findings would not be biased due to attrition.

Data was collected in the post-pandemic era. The Research Ethics Committee of the College of Education and Sports Sciences at Yangtze University provided ethical approval for the present study. Before the first formal survey, written consent was obtained from the school leaders, parents, and adolescents through the explanation of detailed information about the study. Well-trained researchers with negative test results for COVID-19 performed the survey within 50 min during school hours. Honest responses were encouraged by informing the anonymity of the survey. Participants did not receive any kind of gift for their participation. The procedures of the two surveys were the same.

Measures

School resources

The School Assets Subscale (SAS) from the Chinese version of the Developmental Assets Profile was adopted to assess adolescents’ school resources (Scales, 2011). The SAS includes 10 items, and one example item is “I have a school that cares about kids and encourages them”. Response options range from “1 = not at all or rarely” to “4 = extremely or almost always” on a four-point Likert scale. A higher total score indicates more quantity and higher quality of school resources. In previous empirical studies, this subscale suggested good reliability and validity in Chinese adolescents (Chang et al., 2020). In this study, the Cronbach’s α of this scale were 0.869 at T1 and 0.909 at T2.

Self-control

The Chinese version of the Brief Self-Control Scale (BSCS) was employed to measure adolescents’ self-control ability (Tangney et al., 2004; Unger et al., 2016). It consists of 13 items and rates on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = not like me at all” to “5 = very much like me”. One sample item is “Sometimes I can’t stop myself from doing something, even if I know it is wrong”. A higher total score suggests a higher level of self-control ability. This scale had high internal consistency in the Chinese adolescent sample (Gu, 2020). In this study, its Cronbach’s α were 0.752 at T1 and 0.788 at T2.

School bullying and victimization

The Chinese version of the School Bullying and Victimization Scale (SBVS) was adopted to evaluate adolescents’ school bullying and victimization in the past six months (Deng et al., 2018). This scale composes two subscales, each of which includes six items. It rates on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = never” to “5 = several times a week”. One example is “Others call me bad nicknames, scold me, make fun of me and ridicule me”. A higher total score on a subscale reflects a higher level of school bullying or victimization. This measure showed good reliability and validity among Chinese adolescents (Deng et al., 2018). In this study, the Cronbach’s α of the Bullying Subscale were 0.705 at T1 and 0.628 at T2, and the Cronbach’s α of the Victimization Subscale were 0.763 at T1 and 0.624 at T2. The Cronbach’s α of the total SBVS were 0.791 at T1 and 0.676 at T2.

Internet gaming disorder

The Chinese version of the Internet Gaming Disorder Questionnaire was used to measure adolescents’ IGD (Zhang et al., 2017). This scale has 11 items and responses on a three-point Likert scale (“1 = never” to “3 = often”). One example is “Would you skip homework to have more time to play online games”. A higher total score represents a higher level of IGD. This scale demonstrated good reliability and validity in a Chinese adolescent sample (Zhang et al., 2017). In this study, the Cronbach’s α were 0.811 at T1 and 0.827 at T2.

Demographic covariates

Several demographic factors were assessed at T1 in this study, including adolescent age, gender (1 = boys, 2 = girls), grade, only-child family (1 = yes, 2 = no), and family economic level (1 = above the average level, 2 = at the average level, 3 = below the average level).

Analytic plan

SPSS 26.0 and the PROCESS macro were employed to analyze the data. First, the Harman’s single-factor test was performed to evaluate the common method bias. Second, descriptive analysis and Pearson correlational analysis were performed to describe the basic associations among the main variables. Third, hierarchical regression analyses were used to assess the concurrent and longitudinal predictive effects among the main variables. Fourth, the PROCESS macro (model 81) was adopted to test the longitudinal mediating effects in the relationship between school resources, self-control and problem behaviors. Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with 2,000 re-samplings to examine the multiple mediating effects.

Results

Common method bias

Given that the data in the current study was collected by self-reported questionnaires, Harmen’s single factor test was adopted to test the common method bias. At T1, there were eight factors with characteristic root values greater than one, and the first factor only explained 16.71% of the variance. At T2, there were nine factors with characteristic root values greater than one, and the first factor only explained 18.50% of the variance. Overall, the common method bias appeared no threat in the current results.

Descriptive and correlational analyses

Table 1 displays the descriptive and correlational results of the main variables. School resources were positively associated with self-control ability at both waves in medium effect sizes (rs > 0, ps < 0.01). Adolescents who experienced more school resources reported better self-control ability. School resources were negatively related to school bullying and victimization at T2 and IGD at both waves in small-to-medium effect sizes (rs < 0, ps < 0.05). Adolescents obtained more school resources showed less engagement in three problem behaviors. Self-control ability was also negatively correlated to three problem behaviors in small-to-medium effect sizes (rs < 0, ps < 0.01). Adolescents who developed a greater self-control ability tended to engage less in problem behaviors. These three problem behaviors were significantly and positively associated with each other (rs > 0, ps < 0.05). Moreover, adolescent gender and grade were significantly related to self-control ability and three problem behaviors, so they were included as control variables in the following analyses.

Table 1.

The means, standard deviations and correlations among the variables

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | — | — | — | ||||||||||

| 2. Grade | 2.737 | 2.084 | -0.155** | — | |||||||||

| 3. T1 SR | 34.263 | 4.824 | 0.065 | -0.223** | — | ||||||||

| 4. T2 SR | 33.977 | 5.502 | -0.027 | -0.176** | 0.557** | — | |||||||

| 5. T1 SC | 42.453 | 7.379 | -0.012 | -0.315** | 0.393** | 0.307** | — | ||||||

| 6. T2 SC | 42.262 | 7.730 | -0.080* | -0.237** | 0.319** | 0.399** | 0.524** | — | |||||

| 7. T1 SB | 6.539 | 1.465 | -0.146** | 0.032 | -0.053 | -0.036 | -0.177** | -0.043 | — | ||||

| 8. T2 SB | 6.470 | 1.128 | -0.158** | 0.037 | -0.128** | -0.167** | -0.169** | -0.198** | 0.283** | — | |||

| 9. T1 SV | 7.072 | 2.438 | -0.015 | -0.144** | -0.032 | -0.016 | -0.049 | -0.014 | 0.423** | 0.159** | — | ||

| 10. T2 SV | 6.912 | 1.851 | -0.012 | -0.183** | -0.078* | -0.150** | 0.024 | -0.122** | 0.081* | 0.292** | 0.335** | — | |

| 11. T1 IGD | 1.211 | 1.435 | -0.283** | 0.125** | -0.347** | -0.229** | -0.383** | -0.285** | 0.236** | 0.190** | 0.154** | 0.113** | — |

| 12. T2 IGD | 1.121 | 1.457 | -0.212** | 0.086* | -0.233** | -0.247** | -0.280** | -0.404** | 0.137** | 0.329** | 0.104** | 0.182** | 0.465** |

Note. Gender: 1 = girl, 2 = boy; SR = School resources; SC = Self-control; SB = School bullying; SV = School victimization; IGD = Internet gaming disorder; T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Test of the concurrent and longitudinal predictive effects

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, school resources could predict self-control (β > 0, ps < 0.001), school victimization (β < 0, ps < 0.05) and IGD (β < 0, ps < 0.05) concurrently and longitudinally, supporting the first and second hypothesis. Adolescents who obtained more school resources tended to develop a higher level of self-control ability and less involvement in school victimization and IGD. Self-control ability had predictive effects on school bullying (β < 0, ps < 0.01) and IGD (β < 0, ps < 0.001) at the same time and five months later. A good self-control ability could significantly prevent adolescents from developing these two problematic behaviors. School bullying and victimization could concurrently predict each other in small-to-medium effect sizes (β > 0, ps < 0.001). Furthermore, school victimization at T1 predicted bullying at T2. IGD and school bullying concurrently predicted each other in small effect sizes (β > 0, ps < 0.01). IGD and school victimization at T1 could also predict each other (β > 0, ps < 0.05). Adolescents involved in one problem behavior might also develop other more problem behaviors.

Table 2.

Cross-sectional regression analyses

| Outcome | Predictor | T1 | T2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R² | ΔR² | F | β | t | R² | ΔR² | F | β | t | ||

| SC | Gender | 0.214 | 0.111 | 66.742*** | -0.073 | -2.205* | 0.197 | 0.127 | 60.210*** | -0.099 | -2.964** |

| Grade | -0.250 | -7.379*** | -0.189 | -5.549*** | |||||||

| SR | 0.342 | 10.186*** | 0.363 | 10.785*** | |||||||

| SB | Gender | 0.234 | 0.213 | 37.258*** | -0.109 | -3.145** | 0.182 | 0.157 | 27.190*** | -0.112 | -3.145** |

| Grade | 0.033 | 0.944 | 0.021 | 0.575 | |||||||

| SR | 0.065 | 1.780 | -0.051 | -1.366 | |||||||

| SC | -0.130 | -3.383** | -0.063 | -1.551 | |||||||

| SV | 0.405 | 12.181*** | 0.239 | 6.799*** | |||||||

| IGD | 0.111 | 2.904** | 0.222 | 5.767*** | |||||||

| SV | Gender | 0.212 | 0.190 | 32.839*** | 0.047 | 1.342 | 0.151 | 0.116 | 21.627*** | -0.001 | -0.024 |

| Grade | -0.162 | -4.570*** | -0.230 | -6.411*** | |||||||

| SR | -0.026 | -0.710 | -0.110 | -2.918** | |||||||

| SC | 0.017 | 0.438 | -0.055 | -1.339 | |||||||

| SB | 0.417 | 12.181*** | 0.249 | 6.799*** | |||||||

| IGD | 0.087 | 2.226* | 0.070 | 1.750 | |||||||

| IGD | Gender | 0.293 | 0.206 | 50.521*** | -0.264 | -8.241*** | 0.280 | 0.232 | 47.309*** | -0.217 | -6.666*** |

| Grade | -0.050 | -1.474 | -0.042 | -1.244 | |||||||

| SR | -0.217 | -6.366*** | -0.077 | -2.226* | |||||||

| SC | -0.295 | -8.263*** | -0.354 | -9.934*** | |||||||

| SB | 0.103 | 2.904** | 0.196 | 5.767*** | |||||||

| SV | 0.078 | 2.226* | 0.059 | 1.750 | |||||||

Note. Gender: 1 = girl, 2 = boy; SR = School resources; SC = Self-control; SB = School bullying; SV = School victimization; IGD = Internet gaming disorder; T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Table 3.

Longitudinal regression analyses

| Outcome | Predictor | R² | ΔR² | F | β | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2 SC | Gender | 0.147 | 0.077 | 42.153*** | -0.129 | -3.725*** |

| Grade | -0.194 | -5.484*** | ||||

| T1 SR | 0.284 | 8.121*** | ||||

| T2 SB | Gender | 0.083 | 0.058 | 11.031*** | -0.140 | -3.686*** |

| Grade | -0.024 | -0.610 | ||||

| T1 SR | -0.046 | -1.147 | ||||

| T1 SC | -0.127 | -3.020** | ||||

| T1 SV | 0.136 | 3.725*** | ||||

| T1 IGD | 0.068 | 1.617 | ||||

| T2 SV | Gender | 0.064 | 0.029 | 8.369*** | 0.004 | 0.112 |

| Grade | -0.204 | -5.283*** | ||||

| T1 SR | -0.104 | -2.571* | ||||

| T1 SC | 0.054 | 1.251 | ||||

| T1 SB | 0.066 | 1.780 | ||||

| T1 IGD | 0.109 | 2.570* | ||||

| T2 IGD | Gender | 0.148 | 0.100 | 21.191*** | -0.207 | -5.890*** |

| Grade | -0.042 | -1.119 | ||||

| T1 SR | -0.132 | -3.532*** | ||||

| T1 SC | -0.235 | -5.993*** | ||||

| T1 SB | 0.032 | 0.823 | ||||

| T1 SV | 0.066 | 1.718 |

Note. Gender: 1 = girl, 2 = boy; SR = School resources; SC = Self-control; SB = School bullying; SV = School victimization; IGD = Internet gaming disorder; T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Test of the longitudinal mediating effects

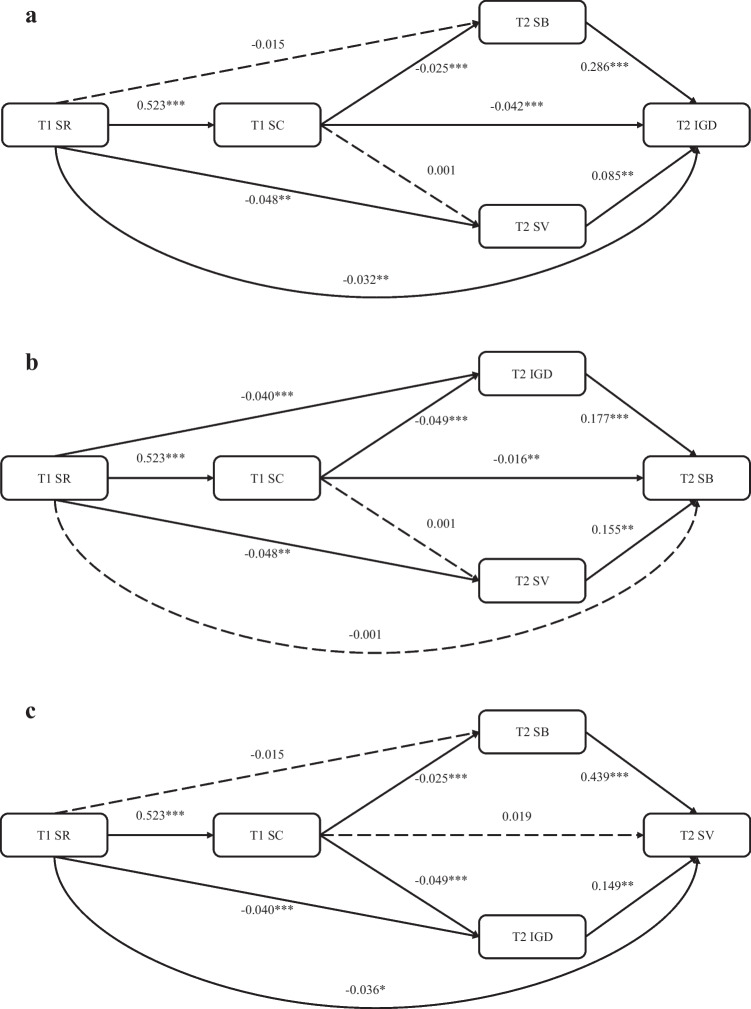

Three longitudinal mediating models were constructed in the PROCESS macro (model 81) to examine the multiple mediating effects in the current study (Fig. 2). Table 4 reports the summary of the multiple longitudinal mediating effects. Self-control ability at T1 significantly mediated the relationships between T1 school resources and T2 problematic behaviors, which supports the third hypothesis. School victimization at T2 could mediate the relationships between school resources at T1, IGD at T2 (β = -0.004, 95%CI: -0.008, -0.001) and school bullying at T2 (β = -0.008, 95%CI: -0.014, -0.003). T2 IGD could mediate the relationships between school resources at T1, school bullying at T2 (β = -0.007, 95%CI: -0.014, -0.002) and school victimization at T2 (β = -0.006, 95%CI: -0.013, -0.001). These findings jointly supported the fourth hypothesis. Moreover, T1 self-control and T2 school bullying had sequential mediating effects on the relationships between T1 school resources, T2 school victimization (β = -0.006, 95%CI: -0.009, -0.003) and T2 IGD (β = -0.004, 95%CI: -0.007, -0.002). T1 self-control and T2 IGD played chain mediating roles in the associations between T1 school resources, T2 school victimization (β = -0.004, 95%CI: -0.008, -0.001) and T2 school bullying (β = -0.005, 95%CI: -0.008, -0.002). These findings supported the fifth hypothesis. Overall, these three problem behaviors might coexist in youth development, but fortunately, school resources could prevent or reduce them directly or indirectly via developing a higher level of self-control ability.

Fig. 2.

a, b, c The relationship between school resources and problematic behaviors. Note: SR = School resources; SC = Self-control; SB = School bullying; SV = School victimization; IGD = Internet gaming disorder; T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2. Gender and grade are covariates; Dashed line indicates a non-significant coefficient. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Table 4.

Summary of the indirect effects

| Pathway | Effect | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| SR → IGD | |||

| T1 SR → T1SC → T2 IGD | -0.022 | 0.005 | [-0.032, -0.013] |

| T1 SR → T2 SB → T2 IGD | -0.004 | 0.003 | [-0.011, 0.0004] |

| T1 SR → T2 SV → T2 IGD | -0.004 | 0.002 | [-0.008, -0.001] |

| T1 SR → T1 SC → T2 SB → T2 IGD | -0.004 | 0.001 | [-0.007, -0.002] |

| T1 SR → T1 SC → T2 SV → T2 IGD | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | [-0.001, 0.001] |

| SR → SB | |||

| T1 SR → T1SC → T2 SB | -0.009 | 0.003 | [-0.014, -0.004] |

| T1 SR → T2 IGD → T2 SB | -0.007 | 0.003 | [-0.014, -0.002] |

| T1 SR → T2 SV → T2 SB | -0.008 | 0.003 | [-0.014, -0.003] |

| T1 SR → T1 SC → T2 IGD → T2 SB | -0.005 | 0.002 | [-0.008, -0.002] |

| T1 SR → T1 SC → T2 SV → T2 SB | 0.0001 | 0.001 | [-0.002, 0.002] |

| SR → SV | |||

| T1 SR → T1SC → T2 SV | 0.010 | 0.005 | [0.001, 0.019] |

| T1 SR → T2 IGD → T2 SV | -0.006 | 0.003 | [-0.013, -0.001] |

| T1 SR → T2 SB → T2 SV | -0.007 | 0.004 | [-0.016, 0.001] |

| T1 SR → T1 SC → T2 IGD → T2 SV | -0.004 | 0.002 | [-0.008, -0.001] |

| T1 SR → T1 SC → T2 SB → T2 SV | -0.006 | 0.002 | [-0.009, -0.003] |

Note. SR = School resources; SC = Self-control; SB = School bullying; SV = School victimization; IGD = Internet gaming disorder; T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2.

Discussion

The outbreak of COVID-19 has brought many challenges to youth development. During this specific period, adolescents have suffered from more and more behavioral problems (Christner et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021a). If not intervened with effectively and immediately, adolescents involved in problematic behaviors will develop more maladaptive consequences in the process of growth (Reaves et al., 2018). Therefore, it is of vital importance to figure out the protective factors to prevent or reduce the occurrence of problem behaviors in adolescence during the post-pandemic era. Under the guidance of the problem behavior theory (Jessor, 1987), the current study combined school resources and self-control to evaluate their joint protective effects on adolescents’ problematic behaviors in a longitudinal study. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to focus on the multiple protective effects or positive factors on problem behaviors in adolescence during the post-pandemic period. Generally, the results confirmed the hypothesized model of the multiple protective roles of school resources and self-control on adolescents’ problem behaviors.

In line with the first and second hypotheses, school resources positively predicted self-control ability and negatively predicted victimization and IGD, concurrently and longitudinally. Adolescents who experienced more school resources tended to develop higher self-control and less engagement in school victimization and IGD. These findings expand previous indirect evidence on the association between school factors, self-control and problem behaviors (Chen et al., 2021; Nie et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021c; Dou et al., 2022; Zou et al., 2022). Moreover, these results also provide empirical support for the social learning theory and the general strain theory (Bandura, 1978; Agnew, 1992), which explain the influence of the environment on individual development. Another important contribution of these findings is to the developmental assets theory (Scales et al., 2000), which claims that adolescents who obtain more school resources will develop more flourishing achievements and fewer problems in the future. As an important subsystem, school has profound impacts on adolescents’ personality traits (self-control) and behavior (victimization and IGD).

Dovetail with previous studies (Jeong et al., 2020; Fenny, 2021; Cho & Lee, 2021; Xiang et al., 2022b), self-control ability had predictive effects on school bullying and IGD at the same time and five months later. A good self-control ability could significantly prevent adolescents from developing these two problematic behaviors. Furthermore, self-control could mediate the relationship between school resources and problem behaviors (IGD, bullying, and victimization). Adolescents who experienced more school resources might develop high self-control, which could prevent them from engaging in problem behaviors. These findings support the self-control theory that lack of self-control is the main cause of behavioral problems (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990). Overall, self-control also plays a protective role in youth development during the post-pandemic period.

With regard to the interactions between problematic behaviors, the fourth hypothesis was also revealed. School bullying and victimization could predict each other concurrently in small-to-medium effect sizes, school victimization could predict bullying over time. IGD and school bullying concurrently predicted each other in small effect sizes. IGD and school victimization could also predict each other. Additionally, victimization could mediate the relationships between school resources, IGD, and bullying. Similarly, IGD mediated the relationships between school resources, bullying, and victimization. That is, once adolescents develop a problem behavior, they are more likely to engage in more problem behaviors if not timely and effectively intervened with (Jessor, 1987). These findings support several previous studies on the associations among problem behaviors (Kim et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022). To a certain degree, these results also provide empirical support for the developmental cascade theory, which highlights that the development of different factors in the same aspect will affect each other (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010).

More importantly, the results confirmed the serial mediation effects. Self-control and school bullying had sequential mediating effects on the relations between school resources, victimization, and IGD. Self-control and IGD played chain mediating roles in the associations between school resources, school victimization, and school bullying. Adolescents who experienced more school resources would develop high self-control, and this could prevent them from engaging in one problematic behavior, which in turn reduces the risk of developing other problem behaviors. These results again support the theories and previous research mentioned above (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990; Masten & Cicchetti, 2010; Xiang et al., 2022b; Li et al., 2022). Moreover, these serial mediating effects also provide empirical support for the problem behavior theory, which claims that problem behaviors are determined by the interactions between the environmental system, personal system, and behavioral system (Jessor, 1987). Overall, it is necessary to jointly intervene in problem behaviors among adolescents.

Contributions and limitations

Theoretically, the current study has made several contributions to the related field. Initially, this study illustrates the importance of positive factors from individuals and schools in youth development during the recovery period of a public emergency. In combination with the previous evidence during the COVID-19 outbreak (Shek et al., 2021; Xiang et al., 2022a), the current findings confirm the joint protective effects of positive factors on adolescent development during ordinary periods and emergencies. It encourages scholars to pay more attention to positive factors when researching developmental problems. Besides, the present study suggests the developmental cascading effects in the process of development. In a cross-level perspective, it reveals that the school environment will shape the development of self-control ability while this personal trait has significant effects on behavioral problems. From different aspects of the same level, the current finding confirms the chain reactions in different types of problem behaviors. This once again reminds scholars to focus on the mutual influence of various problems when exploring the causes and consequences, as individual development is a dynamic process that involves items affecting each other.

Additionally, the current study also provides some implications for related prevention and intervention programs. First, inferred from the current findings from school resources to developmental outcomes, schools may take on more responsibilities in promoting positive youth development. Specifically, schools have to create a free, equal, and harmonious environment and atmosphere for students and provide appropriate rules to monitor students’ performance at school. Teachers have to build good relationships with students, encouraging and supporting them when needed. In addition, schools need to actively engage with families to help young people deal with developmental problems. Second, apart from these external resources, schools should also guide and assist students to develop internal qualities and abilities, such as self-control capacity, through teaching activities or special programs. When a public emergency happens, such as the outbreak of COVID-19, it is often impossible for individuals to obtain external resources in time, but internal attributes function more effectively to protect individuals. Developmental psychologists have developed numerous programs to enhance individuals’ positive attributes. For instance, Shek and his team conducted the “Tin Ka Ping P.A.T.H.S. Project” based on school activity in mainland China and significantly enhanced adolescents’ positive attributes (Zhu & Shek, 2020). Third, practitioners concerned with youth developmental issues are encouraged to conduct combined intervention programs to reduce or prevent adolescents’ problem behaviors, which is challenging to implement but may be more effective.

Despite these contributions to literature and practice, this study also has several limitations, pointing directions for future research. At first, the current study only recruited an adolescent sample from Central China, which limited the generalization of the current findings to young people from other cultures. Future studies may adopt a cross-cultural design to recruit diverse samples to obtain more general results. As for the data collection method, the self-reported questionnaires cannot avoid the unreal but socially expected responses. Future research is encouraged to use more objective approaches to collect data, such as other-reported questionnaires or experimental data. Another important limitation is the study design. The current study conducted a two-wave longitudinal design with a five-month time span, which is too short to examine the stability of the current findings. Scholars may adopt a longer follow-up study to obtain more stable results. Moreover, this study has attempted to reveal the interactions among different problem behaviors, but the current analytical approach may limit the examination of the chain effects among several problem behaviors due to the restriction of PROCESS Macro. Future research is encouraged to evaluate this developmental phenomenon through more advanced methods such as structural equation model techniques. Furthermore, the present study only chose school resources as environmental factors to investigate their positive effects on problematic behaviors. Actually, there are a large number of positive factors from family, school, community, and the whole society that could promote positive youth development and avoid negative outcomes. Scholars may pay more attention to other subsystems to explore more positive factors. And the comparative study of the protective factors and risk factors on adolescents’ problematic behaviors may also provide more critical guidance for practice. Last but also important, the current study only focused on the challenges that adolescents have faced during this pandemic. But recent research has also suggested that adolescents obtain positive experiences in this specific period, such as discovering oneself and connecting with family (Fioretti et al., 2020). Future studies may take a more integrative perspective to compare individuals’ positive and negative changes during this pandemic, which may provide more advice to promote adolescents’ psychological recovery in the post-pandemic era.

Conclusion

In summary, the results confirmed the assumptions about the multiple protective effects of school resources and self-control on adolescents’ problem behaviors. Specifically, school resources could negatively predict IGD and victimization, and self-control mediated these associations. Moreover, one problematic behavior could also mediate the associations between self-control and another problematic behavior. These findings contribute to the previous literature and several theories. Practically, these findings also provide some implications for practitioners to prevent or intervene in adolescents’ problem behaviors during the post-pandemic period.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Youth project of the Ministry of Education in 2020 in the 13th Five-Year Plan of National Education Science: The heterogeneous developmental trajectory of Internet gaming disorder in adolescents: the combined action of parenting environment and genetic polymorphism (grant number: EBA200391) to Xiong Gan. We thank the students for their participation and the reviewers for their constructive suggestions.

Author contribution

Concept and design: X. Gan; Data collection: K. N. Qin, X. Jin and P. Y. Wang; Statistical analysis: G. X. Xiang and H. Li; Drafting of the manuscript: G. X. Xiang; Critical revision of the manuscript: G. X. Xiang and H. Li.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have expressed agreement with the order of authorship and contents of the manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interests that might be interpreted as influencing the research.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Guo-Xing Xiang, Email: 945324088@qq.com.

Xiong Gan, Email: 307180052@qq.com.

References

- Agnew R, White HR. An empirical test of general strain theory. Criminology. 1992;30(4):475–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1992.tb01113.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory of aggression. Journal of Communication. 1978;28(3):12–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1978.tb01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear, G. G. (2010). School discipline and self-discipline: a practical guide to promoting prosocial student behavior. Guilford Press.

- Benson PL, Scales PC, Syvertsen AK. The contribution of the developmental assets framework to positive youth development theory and practice. Advances in Child Development and Behavior. 2011;41:197–230. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386492-5.00008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S, Guo M, Wang J, Wang L, Zhang W. The influence of school assets on the development of well-being during early adolescence: longitudinal mediating effecr of intentional self-regulation. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2020;52(7):874–885. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2020.00874. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JK, Wu C, Wang LC. Longitudinal associations between school engagement and bullying victimization in school and cyberspace in Hong Kong: latent variables and an autoregressive cross-lagged panel study. School Mental Health. 2021;13(3):462–472. doi: 10.1007/s12310-021-09439-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S., & Lee, J. R. (2021). Impacts of low self-control and delinquent peer associations on bullying growth trajectories among korean youth: a latent growth mixture modeling approach. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(7–8), NP4139-NP4169. 10.1177/0886260518786495 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Christner N, Essler S, Hazzam A, Paulus M. Children’s psychological well-being and problem behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: an online study during the lockdown period in Germany. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0253473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Figueiredo, C. S., Sandre, P. C., Portugal, L. C. L., Mázala-de-Oliveira, T., da Silva Chagas, L., Raony, Í, … Bomfim, P. O. S. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: biological, environmental, and social factors. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry,106, 110171. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- De Miranda DM, da Silva Athanasio B, Oliveira ACS, Simoes-e-Silva AC. How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2020;51:101845. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Wang L, Xu J, Li J. The relationships between inter-parental conflict, parent-adolescent conflict and bullying behaviors in juniro high school students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2018;26(1):118–122. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.01.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dou K, Wang LX, Cheng DL, Li YY, Zhang MC. Longitudinal association between poor parental supervision and risk-taking behavior: the role of self‐control and school climate. Journal of Adolescence. 2022;94(4):525–537. doi: 10.1002/jad.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenny, O. A. (2021). Low self-control and school bullying: testing the GTC in nigerian sample of middle school students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0886260521991286. 10.1177/0886260521991286 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fioretti C, Palladino BE, Nocentini A, Menesini E. Positive and negative experiences of living in COVID-19 pandemic: analysis of italian adolescents’ narratives. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11:599531. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.599531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan X, Li H, Li M, Yu C, Jin X, Zhu C, Liu Y. Parenting styles, depressive symptoms, and problematic online game use in adolescents: a developmental cascades model. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021;9:710667. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.710667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Available online at: Stanford University Press.

- Gu M. A longitudinal study of daily hassles, internet expectancy, self-control, and problematic internet use in chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;152:109571. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.109571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Bao Z, Nie T, Liu Y, Zhu J. The association between corporal punishment and problem behaviors among chinese adolescents: the indirect role of self-control and school engagement. Child Indicators Research. 2019;12(4):1465–1479. doi: 10.1007/s12187-018-9592-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J., Huebner, E. S., & Tian, L. (2021). Stability and changes in traditional and cyberbullying perpetration and victimization in childhood: the predictive role of depressive symptoms. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 08862605211028004. 10.1177/08862605211028004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H., Yim, H. W., Lee, S. Y., Lee, H. K., Potenza, M. N., Jo, S. J., & Kim, G. (2020). Low self-control and aggression exert serial mediation between inattention/hyperactivity problems and severity of internet gaming disorder features longitudinally among adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions,9(2), 401–409. 10.1556/2006.2020.00039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jessor R. Problem- behavior theory, psychosocial development, and adolescent problem drinking. British Journal of Addiction. 1987;82(4):331–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Lee JS, Oh S. A path model of school violence perpetration: introducing online game addiction as a new risk factor. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2017;32(21):3205–3225. doi: 10.1177/0886260515597435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JB, Leung ITY, Li Z. The pathways from self-control at school to performance at work among novice kindergarten teachers: the mediation of work engagement and work stress. Children and Youth Services Review. 2021;121:105881. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li JB, Bi SS, Willems YE, Finkenauer C. The association between school discipline and self-control from preschoolers to high school students: a three-level meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research. 2021;91(1):73–111. doi: 10.3102/0034654320979160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C., Song, Y., Wang, Q., & Zhang, B. (2021c). How does self-control affect academic achievement of adolescents? The dual perspectives of teacher-student relationship and mastery approach goals. Youth & Society, 0044118X211030949. 10.1177/0044118X211030949

- Li H, Gan X, Xiang GX, Zhou T, Wang P, Jin X, Zhu C. Peer victimization and problematic online game use among chinese adolescents: the dual mediating effect of deviant peer affiliation and school connectedness. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022;13:823762–823762. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.823762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JB, Delvecchio E, Lis A, Nie YG, Di Riso D. Parental attachment, self-control, and depressive symptoms in chinese and italian adolescents: test of a mediation model. Journal of Adolescence. 2015;43:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JB, Liberska H, Salcuni S, Delvecchio E. Aggressive perpetration and victimization among polish male and female adolescents: the role of attachment to parents and self-control. Crime & Delinquency. 2019;65(3):401–421. doi: 10.1177/0011128718787472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Sidibe AM, Shen X, Hesketh T. Incidence, risk factors and psychosomatic symptoms for traditional bullying and cyberbullying in chinese adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review. 2019;107:104511. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Q, Yu C, Xing Q, Liu Q, Chen P. The influence of parental knowledge and basic psychological needs satisfaction on peer victimization and internet gaming disorder among chinese adolescents: a mediated moderation model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(5):2397. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q., Zhou, Y., Xie, X., Xue, Q., Zhu, K., Wan, Z., … Song, R. (2021a). The prevalence of behavioral problems among school-aged children in home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Journal of Affective Disorders,279, 412–416. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y., Gong, R., Yu, Y., Xu, C., Yu, X., Chang, R., … Cai, Y. (2021b). Longitudinal predictors for incidence of internet gaming disorder among adolescents: the roles of time spent on gaming and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence,92, 1–9. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ma N, Zhang W, Yu CF, Zhu JJ, Jiang YP, Wu T. Perceived school climate and internet gaming disorder in junior school students: a moderated mediation model. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017;25(1):65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Cicchetti D. Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(3):491–495. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Q., Yang, C., Stomski, M., Zhao, Z., Teng, Z., & Guo, C. (2021). Longitudinal link between bullying victimization and bullying perpetration: a multilevel moderation analysis of perceived school climate. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0886260521997940. 10.1177/0886260521997940 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pakarinen E, Silinskas G, Hamre BK, Metsäpelto RL, Lerkkanen MK, Poikkeus AM, Nurmi JE. Cross-lagged associations between problem behaviors and teacher-student relationships in early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2018;38(8):1100–1141. doi: 10.1177/0272431617714328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt TC, Turanovic JJ, Fox KA, Wright KA. Self-control and victimization: a meta‐analysis. Criminology. 2014;52(1):87–116. doi: 10.1111/1745-9125.12030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reaves S, McMahon SD, Duffy SN, Ruiz L. The test of time: a meta-analytic review of the relation between school climate and problem behavior. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2018;39:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scales PC. Youth developmental assets in global perspective: results from international adaptations of the developmental assets profile. Child Indicators Research. 2011;4(4):619–645. doi: 10.1007/s12187-011-9112-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scales PC, Benson PL, Leffert N, Blyth DA. Contribution of developmental assets to the prediction of thriving among adolescents. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4(1):27–46. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0401_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shek DT, Zhao L, Dou D, Zhu X, Xiao C. The impact of positive youth development attributes on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among chinese adolescents under COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2021;68(4):676–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Li JB, Oktaufik MPM, Vazsonyi AT. Parental attachment and externalizing behaviors among chinese adolescents: the mediating role of self-control. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2022;31(4):923–933. doi: 10.1007/s10826-021-02071-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality. 2004;72(2):271–324. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng Z, Bear GG, Yang C, Nie Q, Guo C. Moral disengagement and bullying perpetration: a longitudinal study of the moderating effect of school climate. School Psychology. 2020;35(1):99. doi: 10.1037/spq0000348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu KC, Chen SS, Mesler RM. Trait self-construal, inclusion of others in the self and self-control predict stay-at-home adherence during COVID-19. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;175:110687. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger A, Bi C, Xiao YY, Ybarra O. The revising of the tangney self-control scale for chinese students. PsyCh Journal. 2016;5(2):101–116. doi: 10.1002/pchj.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachs S, Mazzone A, Milosevic T, Wright MF, Blaya C, Gámez-Guadix M, Norman JOH. Online correlates of cyberhate involvement among young people from ten european countries: an application of the routine activity and problem behaviour theory. Computers in Human Behavior. 2021;123:106872. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2022). Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19–18 May 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022, from https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---18-may-2022

- Xiang, G. X., Gan, X., Jin, X., & Zhang, Y. H. (2022a). The more developmental assets, the less internet gaming disorder? Testing the cumulative effect and longitudinal mechanism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychology, 1–12. 10.1007/s12144-022-03790-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xiang, G. X., Gan, X., Jin, X., Zhang, Y. H., & Zhu, C. S. (2022b). Developmental assets, self-control and internet gaming disorder in adolescence: Testing a moderated mediation model in a longitudinal study. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 808264. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.808264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xu P, Cheng J. Individual differences in social distancing and mask-wearing in the pandemic of COVID-19: the role of need for cognition, self-control and risk attitude. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;175:110706. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C, Li X, Zhang W. Predicting adolescent problematic online game use from teacher autonomy support, basic psychological needs satisfaction, and school engagement: a 2-year longitudinal study. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking. 2015;18(4):228–233. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y., Peng, L., Mo, P. K., Yang, X., Cai, Y., Ma, L., … Lau, J. T. (2022). Association between relationship adaptation and internet gaming disorder among first-year secondary school students in China: mediation effects via social support and loneliness. Addictive Behaviors,125, 107166. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107166 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang D, Huebner ES, Tian L. Longitudinal associations among neuroticism, depression, and cyberbullying in early adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior. 2020;112:106475. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yu C, Zhang W. Psychosocial and social factors of adolescnet’s internet gaming disorder. China Journal of Health Psychology. 2017;25(7):1058–1061. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2017.07.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Shek DT. Impact of a positive youth development program on junior high school students in mainland China: a pioneer study. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020;114:105022. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H, Deng Y, Wang H, Yu C, Zhang W. Perceptions of school climate and internet gaming addiction among chinese adolescents: the mediating effect of deviant peer affiliation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(6):3604. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.