Abstract

Background:

Cardiac hypertrophy increases demands on protein-folding, which causes an accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER. These misfolded proteins can be removed via the adaptive retrotranslocation, polyubiquitylation, and a proteasome-mediated degradation process, ER-associated degradation (ERAD), which, as a biological process and rate, has not been studied, in vivo. To investigate a role for ERAD in a pathophysiological model, we examined the function of the functional initiator of ERAD, VCP-interacting membrane protein (VIMP), positing that VIMP would be adaptive in pathological cardiac hypertrophy in mice.

Methods:

We developed a new method involving cardiac myocyte-specific AAV9-mediated expression of the canonical ERAD substrate, TCRa, to measure the rate of ERAD, i.e. ERAD flux, in the heart, in vivo. AAV9 was also used to either knockdown or overexpress VIMP in the heart, then mice were subjected to transverse aortic constriction (TAC) to induce pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy.

Results:

ERAD flux was slowed in both human heart failure and mice after TAC. Surprisingly, while VIMP adaptively contributes to ERAD in model cell lines, in the heart, VIMP knockdown increased ERAD and ameliorated TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Coordinately, VIMP overexpression exacerbated cardiac hypertrophy, which was dependent upon VIMP engaging in ERAD. Mechanistically, we found that the cytosolic protein kinase, SGK1, is a major driver of pathological cardiac hypertrophy in mice subjected to TAC, and that VIMP knockdown decreased the levels of SGK1, which subsequently decreased cardiac pathology. We went on to show that even though it is not an ER protein, and resides outside of the ER, SGK1 is degraded by ERAD in a non-canonical process we call ERAD-Out. Despite never having been in the ER, SGK1 is recognized as an ERAD substrate by the ERAD component, DERLIN1 and, uniquely in cardiac myocytes, VIMP displaces DERLIN1 from initiating ERAD, which decreased SGK1 degradation and promoted cardiac hypertrophy.

Conclusions:

ERAD-Out is a new preferentially favored non-canonical form of ERAD that mediates the degradation of SGK1 in cardiac myocytes and in so doing, is therefore an important determinant of how the heart responds to pathological stimuli, such as pressure overload.

Keywords: ER associated protein degradation, SGK1, VIMP, cardiac hypertrophy

Introduction:

Misfolded proteins that accumulate in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in response to pathophysiological stimuli disrupt protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, and challenge cellular integrity1–3. The ER maintains proteostasis by eliminating misfolded proteins in an evolutionarily conserved process termed ER-associated degradation (ERAD)4–6. Canonical ERAD is thought to comprise the following sequential events, as shown in Figure 1A: (1) substrate recognition, (2) retrotranslocation, (3) ubiquitylation, (4) ER membrane dislocation, and (5) proteasome-mediated degradation6. ERAD can be classified into three functionally distinct pathways based on the nature and location of its substrates, ERAD-L, −M, and −C, depending on whether misfolded domains in ERAD substrates are located in the ER lumen (L), membrane (M) or on the cytosolic face of the ER (C)6, 7. ERAD-L substrates are located inside the ER lumen and their degradation requires both HRD1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, and the Derlin family of proteins that collaboratively support the retrotranslocation of these substrates through the ER membrane. Both ERAD-M and ERAD-C substrates are single or multi-spanning ER membrane proteins that are misfolded in either their transmembrane domains (ERAD-M), or on a cytosolic facing domains (ERAD-C)6, 7. Importantly, the ERAD substrates that have been described to date are proteins that became ER resident after being co-translationally translocated to the ER lumen or the ER membrane and, since there are no proteasomes in the ER, if they misfold they must be retrotranslocated out of the ER to be ubiquitylated and targeted for degradation by cytosolic proteasomes.

Figure 1.

ERAD is impaired in both human and a murine model of heart failure

(A) Schematic diagraming steps in canonical ERAD of misfolded proteins in the ER.

(B and C) Western blots (WB) of LV extracts of human myocardial biopsy samples from failing and non-failing human hearts (B), or mouse hearts after sham or TAC (C) for expression of ubiquitylated proteins (UBQ), high molecular weight (HMW) amyloid oligomers, HRD1, or VIMP.

(D and E) Analysis of myocardial protein aggregation in human (D) and mouse (E) heart failure. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM; n=6 human samples and n=5 mice per group. *p<0.01 as determined by unpaired t test.

(G) Immunohistochemistry of mouse LV sections for protein aggregation (green), tropomyosin (red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue) of Sham or TAC-HF mice.

(G and H) Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) for a panel of ERAD genes in human (G) and mouse (H) heart failure. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM; n=6 human samples and n=5 mice per group. *p<0.01 as determined by unpaired t test.

(I) WB of HA-TCRa in adult mouse ventricular myocytes (AMVM) isolated from sham or TAC-HF mice.

(J) Densitometry analysis of WB in panel I to determine degradation rate of HA-TCRa. Bar graph shows mean ± SEM; n=3 mice per group. *, **, # p<0.01 versus respective control and statistically independent group across all cross-compared data as determined by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

VIMP, also called SelenoproteinS and SelS, is a 189 amino acid trans-ER membrane selenoprotein with a single pass transmembrane domain near the N-terminus and selenocysteine (Sec) near the C-terminus, at residue 1888, 9. VIMP interacts directly with valosin-containing protein (VCP) and HRD1, as well as many other proteins to form a multiprotein complex required for ERAD (Fig. 1A)10, 11. The critical role for VIMP is the recruitment of VCP from the cytosol to the ER, which is required to nucleate the ERAD complex, a function only attributed to a select few ERAD proteins10–12. VCP is a AAA+-type ATPase that acts as a ‘ratchet’ that extracts proteins out of the ER, after which they are ubiquitylated by ER-transmembrane E3 ubiquitin ligases, which leads to their degradation13. Prolines 178 and 183 of VIMP are required for its interaction with VCP and thus its ability to recruit VCP to the ER; accordingly, mutating these two residues to alanine impairs ERAD complex formation and ERAD14. Additionally, VIMP can be mutated so that selenium is not incorporated; while this does not disrupt its ability to recruit the ERAD machinery and form an ERAD complex, it does disrupt its antioxidant activity9.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) accounts for 1 in every 3 deaths in the US15. Many forms of CVD are associated with increased left ventricular (LV) load-induced cardiac hypertrophy, considered pathological, as it reduces cardiac contractility and can lead to heart failure1. Since pathological cardiac hypertrophy can lead to heart failure, it is important to understand this process in order to design better therapies. Cardiac hypertrophy is associated with increased protein synthesis in cardiac myocytes, which must be balanced by coordinate increases in protein degradation processes, including ERAD, in order to maintain cardiac myocyte viability, cardiac contractility, and to avoid heart failure1–3. Despite accumulating evidence that ERAD possesses vital, pro-survival effects in various diseases, including diabetes16, Alzheimer’s disease17, 18, and cardiovascular disease19, ERAD efficiency as a measure of the rate of misfolded protein degradation, has not been examined in animal models of pathology. Here, we examined roles for ERAD in human hearts and mouse models of cardiac pathology, utilizing a novel synthetic tool for monitoring the rate of ERAD flux in the heart, in vivo. We focused on the ERAD component, VIMP, as it has been shown in cultured cell models to be important for ERAD and cell viability; however, VIMP has not been studied in the setting of pathology, in vivo. Our results identify a new class of ERAD, we’ve termed “ERAD-Out” that comprises non-ER proteins that are degraded by ERAD and therefore do not require retrotranslocation, and do not have inherent misfolded domains.

Methods:

Data availability

The authors declare that all data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplemental Material. The data, analytical methods, and study materials will be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedures.

Patient samples

Deidentified heart tissue samples were obtained from the Human Heart Tissue Bank at the University of Pennsylvania. All study procedures were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Hospital Institutional Review Board. Prospective informed consent for research use of heart tissue was obtained from all transplant recipients, and consent was provided by next-of-kin in the case of organ donors.

Laboratory animals

The research reported in this article has been reviewed and approved by the University of Arizona Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Research Council.

Statistics

For studies involving TAC, cohort sizes were based on a predictive power analysis to achieve 80% power at the 5% error rate using G*Power 3.1.9.3. Cell culture experiments were performed with at least three cultures for each treatment. Shapiro-Wilk tests were performed to examine data normality. Two-group comparisons were performed using Student’s unpaired t test, and all multiple group comparisons were performed using a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test post-hoc analysis. All analyses were performed using Prism 7.0e. mRNA and protein expression levels were normalized to either glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) or β-Actin levels. Where appropriate, a linear transformation was performed to set the result of control group (usually Con Sham or Vehicle) to 1, by dividing each group with the average obtained for their control group. Data are represented as mean with all error bars indicating ± SEM. *, **, ***, # p<0.01 versus respective control and independent group as detailed in the respective figure legend.

Results:

ERAD is Impaired in Heart Failure

To begin to understand how ERAD is affected in heart failure (HF), we examined ERAD expression in failing left ventricular myocardium (LV) from heart transplant recipients who, at the time of transplant, were in severe late-stage heart failure with a LV ejection fraction <20% and non-failing LV from brain-dead organ donors. For a comparison, we also subjected mice to sham or a pressure-overload surgical model of heart failure, transverse aortic constriction (TAC-HF), and assayed mouse hearts that met the same ejection fraction criteria upon sacrifice. Ubiquitylated proteins and preamyloid oligomers (PAOs) increased in pathological human and mouse hearts (Figure 1B–F), denoting impaired ubiquitin proteasome-mediated degradation, as well as increased PAO formation in the diseased hearts. The ERAD proteins, HRD1 and VIMP (Figure 1B and 1C), as well as transcripts for SelenoS, Syvn1, Derl1, and Sel1l were all decreased in both human and mouse HF samples (Figure 1G and 1H), implying a pathologic suppression of ERAD during HF. Furthermore, a recent transcriptome analysis of LV biopsy samples of heart failure patients (Hahn et al., 2020)20 showed that protein processing in the ER, and ER stress, were among the most dysregulated processes, coordinate with our findings here.

We previously developed a method for measuring ERAD in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVM), where we express 1XHA-TCRa, a subunit of the T-cell receptor that is made in the ER of T-cells19. When expressed in cells that do not express the other TCR subunits, TCRa misfolds and is degraded by canonical ERAD requiring retrotranslocation of TCRa into the cytosol. Thus, determining the degradation rate of TCRa in cardiac myocytes treated with cycloheximide (CHX) to arrest translation, is a measure of the rate of ERAD. However, this assay had never been used before in vivo and there are no reports of methods for measuring the rate of ERAD in any organ, in vivo. Accordingly, we adapted this technology to measure the rate of ERAD in cardiac myocytes from mice treated in various ways using adeno-associated virus (AAV9) encoding HA-TCRa under the control of the MLC2v promoter, which restricts expression to cardiac myocytes21. Mice treated with AAV9–3XHA-TCRa were subjected to TAC-HF, then adult mouse ventricular myocytes (AMVM) were prepared and the rate of HA-TCRa degradation was assessed via western blot (Figure 1I). Consistent with the decreased expression of ERAD components in failing hearts, the rate of ERAD was significantly reduced in heart failure, as evidenced by the significantly slower rate of degradation of HA-TCRa (Figure 1J).

VIMP Mediates Pathologic Cardiac Hypertrophy Via Engaging in ERAD

To examine roles for ERAD in the heart we knocked down VIMP in mouse hearts, positing that it would impair ERAD and promote cardiac pathology in our mouse model of HF. Accordingly, mice were treated with AAV9-Control or AAV9-shVimp, the latter of which encodes a small harpin targeting endogenous VIMP, which effectively knocked down VIMP in mouse hearts (Fig. 2B and S1A). Mice were then subjected to sham or TAC surgery (Figure 2A). While longitudinal echocardiography of mice treated with AAV9-Control demonstrated the expected progressive cardiac hypertrophy (Figure S1B; green) and decreased function (Figure S1B; black), we were surprised to find that VIMP knockdown resulted in a nearly complete protection from these effects (Figure S2C). Echocardiography and mitral flow pulse-wave Doppler, as measured by M-mode and Doppler still images (Figure 2C and 2D), demonstrated that VIMP knockdown resulted in the maintenance of systolic (Figure 2E) and diastolic (Figure 2F) cardiac performance after TAC, despite high-frequency Doppler measurements between the innominate and left carotid arteries demonstrating identical pressure-overload in all mice. Moreover, while Control mice subjected to TAC exhibited increased heart and lung weights, indicating cardiac hypertrophy and pulmonary congestion, respectively, VIMP knockdown abrogated these effects (Figure 2G and 2H). Histological analysis demonstrated at the cellular level that VIMP knockdown also blunted TAC-mediated cardiac myocyte hypertrophy (Figure S1D) and decreased interstitial and perivascular fibrosis (Figure S1E).

Figure 2.

VIMP mediates pathological cardiac hypertrophy

(A and I) Experimental schematic of cardiac function analysis by longitudinal echocardiography at different times after TAC.

(B and J) WB for VIMP in mouse hearts 6 weeks after sham or TAC.

(C and D) Representative still images from M-mode echocardiography (C) and mitral valve pulse-wave (PW) Doppler (D) in mouse hearts 6 weeks after sham or TAC. Green arrows mark early (E) and late (A) waves forms of LV filling rates.

(E and K) Systolic function as measured by echocardiography to determine fractional shortening in mouse hearts 6 weeks after sham or TAC.

(F and L) Diastolic function as determined by PW Doppler to analyze E and A waves.

(G, H, M, N) Gravimetric measurement ratios of heart weight to tibia length, HW/TL (G and M), and wet lung weight to tibia length, LuW/TL (H and N). (E-H and K-N) Bar graph shows mean ± SEM; n=5–9 mice per group. * and # p<0.01 versus respective sham and statistically independent group across all cross-compared data as determined by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

We also examined VIMP gain-of-function by treating mice with AAV9-Control, AAV9-FLAG-Vimp, or AAV9-FLAG-Vimp−ERAD, the latter of which features mutations of prolines 178 and 183 to alanine, rendering it incapable of recruiting VCP to engage in ERAD14. These mice were subjected to sham or TAC surgeries and monitored for 6 weeks with longitudinal echocardiography (Figure 2I). We verified that FLAG-Vimp and FLAG-Vimp−ERAD were expressed at levels similar to that of endogenous VIMP (Figure 2J). In contrast to VIMP knockdown, overexpression of VIMP resulted in a more rapid and severe decrease in cardiac function (Figure 2K, L) that was accompanied by exacerbated cardiac hypertrophy (Figure 2M), and pulmonary congestion (Figure 2N). However, this was not observed with overexpression of Vimp−ERAD, confirming that the unanticipated deleterious effects of VIMP on cardiac structure and function required ERAD (Figure 2K–N).

At the molecular level, in AAV9-Control animals, TAC increased the transcript levels of cardiac pathology-associated genes, such as Nppa, Nppb, Myh7, Col1a1, and Pstn and reduced levels of Atp2a2, a marker of HF20. Notably, these responses were significantly attenuated in shVimp mouse hearts (Figure S1F) but were exaggerated in FLAG-Vimp mouse hearts (Figure S1G), consistent with the effects of VIMP knockdown and overexpression on cardiac structure and function. mTORC1 is a master regulator of protein synthesis in response to growth conditions and sustained mTORC1 signaling is a hallmark of pathological cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling22–24. Here, mTORC1 activity was increased in Control animals after TAC, as measured by increased phosphorylation of mTORC1 downstream targets, S6K (p70 ribosomal S6 kinase; Thr389), and eukaryotic translational initiation factor 4E-BP1 (4E-binding protein 1; Thr37/46); however, mTORC1 activation was significantly blunted in shVimp mouse hearts (Figure S1H), and enhanced in FLAG-Vimp mouse hearts (Figure S1I), indicating that VIMP contributes to TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy at least in part by increasing mTORC1 signaling. Importantly, FLAG-Vimp−ERAD mice were protected from all of these pathological cardiac remodeling and molecular signaling phenotypes (Figure 2K–2N; S1G and S1I), indicating that it is by engaging in ERAD that VIMP promotes cardiac pathology in response to TAC.

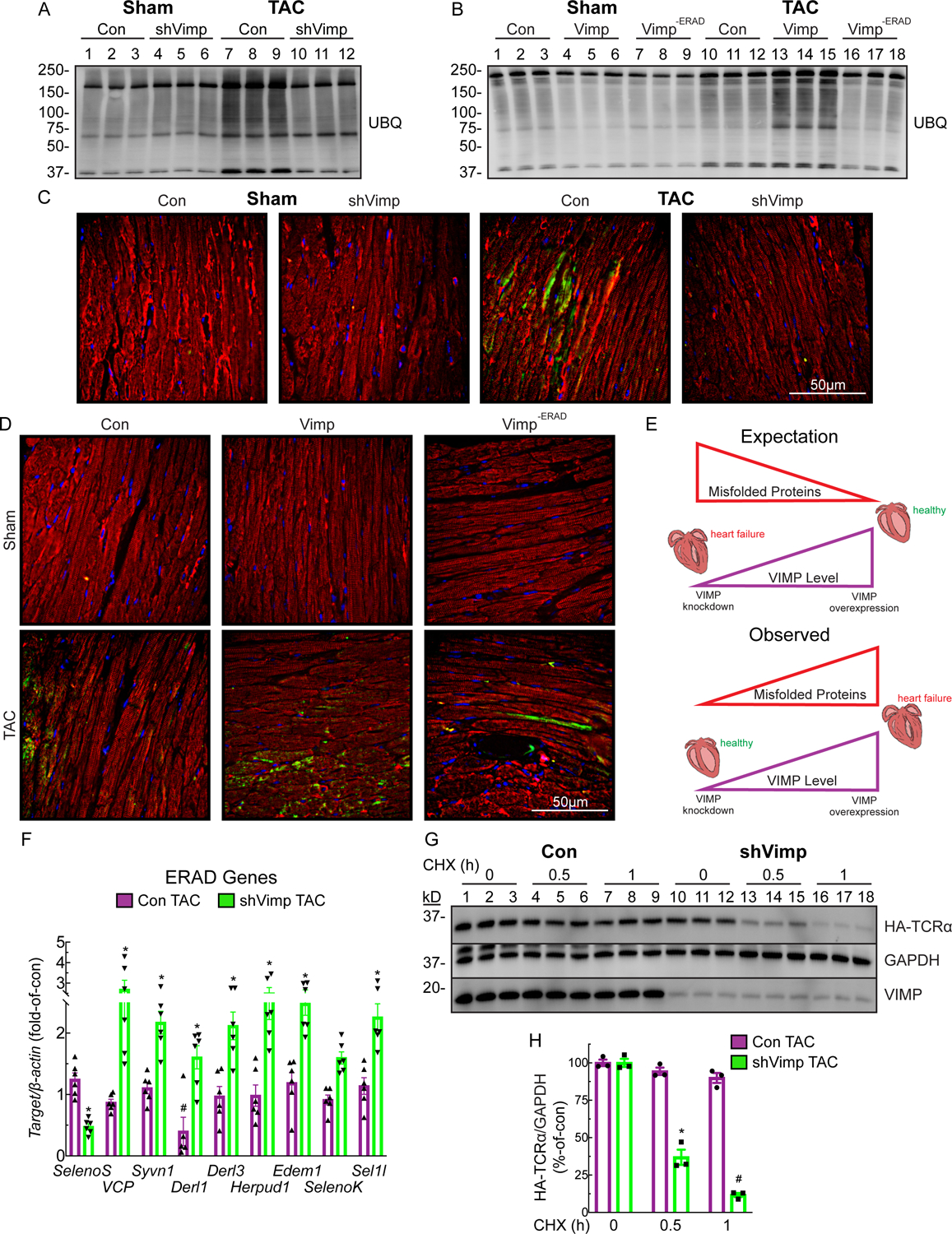

Compared to Control LV extracts from shVimp mouse hearts had a decreased accumulation of ubiquitylated proteins after TAC, while FLAG-Vimp mouse hearts had increased accumulation of ubiquitylated proteins (Figure 3A and 3B), indicating that VIMP knockdown promoted degradation of misfolded proteins, while VIMP overexpression decreased it. Immunohistochemistry of LV sections from mouse hearts confirmed a diminutive aggregation of PAOs in shVimp mice and a robust increased aggregation of PAOs in FLAG-Vimp mice (Figure 3C and 3D). Of note, this accumulation of ubiquitylated proteins and PAOs were not observed in FLAG-Vimp−ERAD mouse hearts (Figure 3B and 3D), correlating with the cardiac functional effects observed in response to TAC. Thus, despite our expectation that VIMP overexpression would abrogate misfolded protein accumulation and reduce cardiac hypertrophy, we found that VIMP overexpression actually promoted misfolded protein accumulation and cardiac hypertrophy (Figure 3E). Most intriguing was our finding that the ability of VIMP to increase pathology was dependent upon its engagement in ERAD, a process that we thought would decrease pathology. Accordingly, to better understand these unexpected results, we dove deeper into the mechanism of VIMP function in the heart.

Figure 3.

VIMP exacerbates misfolded protein aggregation in the hypertrophic heart

(A and B) WB for UBQ proteins in mouse hearts 6 weeks after sham or TAC.

(C and D) Immunohistochemistry of LV sections for protein aggregation (green), tropomyosin (red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue) in mouse hearts 6 weeks after sham or TAC.

(E) Schematic detailing the expected vs the observed findings linking increased Vimp levels to increased cardiac hypertrophy and accumulated misfolded proteins.

(F) qPCR for a panel of ERAD genes in Con or shVimp mice 6 weeks after TAC relative to respective sham. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM; n=6 mice per group. *p<0.01 as determined by unpaired t test.

(G) WB of HA-TCRa in AMVM isolated from Con or shVimp mice 6 weeks after TAC.

(H) Densitometry analysis of WB in panel G to determine degradation rate of HA-TCRa. Bar graph shows mean ± SEM; n=3 mice per group. * and # p<0.01 versus respective control and statistically independent group across all cross-compared data as determined by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

VIMP Knockdown Unexpectedly Enhances ERAD in the Heart

Interestingly, while a panel of ERAD genes were only moderately affected in Control mice subjected to TAC, VIMP knockdown promoted a significant induction of a majority of these genes (Figure 3F), suggesting that enhanced ERAD might mediate the protective effects of VIMP knockdown. To address this, we assessed ERAD in AMVM from Control or shVimp mouse hearts after sham or TAC surgeries (Figure 3G). While, as expected, HA-TCRa degradation was blunted by TAC in Control AMVM, surprisingly, VIMP knockdown rescued this effect and enhanced the rate of ERAD (Figure 3H). These results implicate a new and unexpected role for VIMP as a regulator of ERAD in ways that moderate cardiac pathology.

VIMP Impedes “ERAD-Out” Selectively in the Cardiac Myocyte

To gain further insight into the unexpected effects of VIMP on ERAD in the heart, we investigated whether VIMP affects cardiac hypertrophy via selectively regulating a particular ERAD pathway (i.e. ERAD-M or ERAD-L). To this end, we ectopically expressed an ERAD-M substrate, i.e. HA-TCRa, or the ERAD-L substrate, i.e. the misfolded genetic variant-null Hong Kong alpha1-antitrypsin (ma1AT)25, both of which have been used as model ERAD substrates. As we observed in AMVM, knocking down VIMP in NRVM significantly increased the degradation rates of both substrates (Figure 4A and 4B; Figure S2A and S2B). Interestingly, overexpressing VIMP but not VIMP−ERAD also increased the degradation rates of both substrates (Figure 4C and 4D; Figure S2C–F). Thus, unexpectedly, VIMP knockdown and overexpression increased ERAD-M and −L, indicating a possible redundant role for VIMP in canonical ERAD in cardiac myocytes.

Figure 4.

VIMP selectively impedes degradation of the “ERAD-Out” substrate, SGK1, in cardiac myocytes

(A and C) WB of ERAD-M substrate, HA-TCRa, that was infected via adenovirus in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVM) and transfected with siCon or siVimp (A), or infected with AdV-Con or AdV-Vimp (C) and treated with phenylephrine (PE) for 48 hours.

(B and D) Densitometry analysis of WB in panel A (B) or panel C (D) to determine degradation rate of HA-TCRa. Bar graph shows mean ± SEM; n=3 NRVM cultures repeated from at least two independent NRVM isolations per group. *, **, ***, # p<0.01 versus respective control and statistically independent group across all cross-compared data as determined by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

(E and F) qPCR for prohypertrophic markers Nppa and Nppb in NRVM transfected with siCon or siVimp (A), or infected with AdV-Con or AdV-Vimp (C) and treated with PE for 48 hours. Bar graph shows mean ± SEM; n=3 NRVM cultures repeated from at least two independent NRVM isolations per group. * and # p<0.01 versus respective vehicle and statistically independent group across all cross-compared data as determined by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

(G and I) WB of “ERAD-Out” substrate, FLAG-SGK1, that was infected via adenovirus in NRVM and transfected with siCon or siVimp (G), or infected with AdV-Con or AdV-Vimp (I) and treated with PE for 48 hours.

(H and J) Densitometry analysis of WB in panel G (H) or panel I (J) to determine degradation rate of FLAG-SGK1. Bar graph shows mean ± SEM; n=3 NRVM cultures repeated from at least two independent NRVM isolations per group. *, **, ***, # p<0.01 versus respective control and statistically independent group across all cross-compared data as determined by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

(K) Schematic detailing the proposed mechanism whereby increased VIMP levels are discordant with canonical ERAD substrate, TCRa, but increase the level of the “ERAD-Out” substrate, SGK1, which correlates with increased cardiac hypertrophy.

To explore whether cardiac myocyte hypertrophy is affected by VIMP knockdown and overexpression the same way ERAD is affected, NRVM were treated with the a1-adrenergic receptor agonist, phenylephrine (PE), which mimics TAC-induced pressure overload22. As observed in mouse hearts subjected to TAC, knocking down VIMP attenuated induction of the cardiac myocyte hypertrophy as measured by cell size (Figure S2G) and Nppa and Nppb in NRVM (Figure 4E), while overexpressing VIMP exacerbated cardiac myocyte hypertrophy (Figure S2H and 4F). In parallel, PE-mediated increases in protein ubiquitylation were decreased by VIMP knockdown (Figure S3A) and increased by overexpressing VIMP but not VIMP−ERAD (Figure S3B and S3C). Thus, paradoxically, while VIMP knockdown and overexpression both increased degradation of canonical ERAD substrates in cardiac myocytes, they had opposing effects on cardiac hypertrophy, which mechanistically dissociates canonical ERAD from cardiac hypertrophy. Nonetheless, the effects of VIMP on cardiac hypertrophy still require ERAD, suggesting a non-canonical role for ERAD. Accordingly, we searched for a possible non-canonical ERAD substrate that might be involved in cardiac hypertrophy.

Recently, cardiac-specific activation of serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 (SGK1) has been shown to increase cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction26, 27. Furthermore, in renal epithelial cells SGK1 exhibits a short half-life and is degraded in a ubiquitin proteasome system-dependent manner28–31. While it has not been studied as a putative ERAD target, we hypothesized that it is by inhibiting the non-canonical ERAD-mediated degradation of SGK1 that VIMP promotes cardiac hypertrophy. To test this, we examined the effects of VIMP knockdown and overexpression on the degradation rate of FLAG-SGK1. The rapid degradation of FLAG-SGK1 was significantly enhanced by VIMP knockdown (Figure 4G and 4H) and slowed by overexpression of VIMP but not VIMP−ERAD (Figure 4I and 4J; Figure S3D and S3E), indicating that VIMP impedes the degradation of SGK1 in an ERAD-dependent manner. Thus, SGK1 represents a newly defined type of ERAD substrate that has never resided within the ER and therefore does not require retrotranslocation to be degraded by ERAD; here, we call this process ERAD-Out, where non-canonical ERAD-Out substrates are distinguished from the canonical ERAD-L, −M, or −C substrates, the latter of which could be referred to as ERAD-In. Thus, while both VIMP knockdown and overexpression enhanced degradation of canonical ERAD-In substrates (Figure 4K, Step 1), only VIMP knockdown increased degradation of the ERAD-Out substrate, SGK1 (Figure 4K, Step 2), consistent with the observed effect of VIMP knockdown on pathological hypertrophy (Figure 4K, Step 3).

SGK1 is a Pro-Hypertrophic “ERAD-Out” Substrate

In response to growth factors, SGK1 phosphorylates downstream targets such as NDRG134, NEDD4–235, and mTOR36 and promotes cardiac hypertrophy and lethal ventricular arrythmias26, 27. Intriguingly, in renal epithelial cells, it has been shown that SGK1 localizes to the cytosolic face of the ER via a six residue “GMVAIL” ER targeting sequence; this localization of SGK1 to the ER is required for the ubiquitylation of SGK1 on six lysine residues, and subsequent degradation by proteasomes30 (Figure S4A). We tested whether SGK1 ubiquitylation and degradation functions this way in cardiac myocytes by expressing either FLAG-SGK1, or a form of FLAG-SGK1 lacking the ER targeting sequence, i.e. FLAG-SGK1GMVAIL. Immunocytofluorescence demonstrated that, while FLAG-SGK1 was perinuclear, characteristic of ER associated proteins, FLAG-SGK1GMVAIL was diffusely localized and expressed at higher levels (Figure S4B). Moreover, FLAG-SGK1GMVAIL was resistant to degradation, even when VIMP was knocked down (Figure S4C). Consistent with the higher levels of FLAG-SGK1GMVAIL, it promoted greater PE-mediated induction of Nppa and Nppb, indicating a more robust effect on cardiac myocyte hypertrophy (Figure S4D). Lastly, immunoprecipitation (IP) of either FLAG-SGK1 or FLAG-SGK1GMVAIL from NRVMs was performed to examine functional interactions with HRD1 as related to ERAD-mediated degradation of SGK1 (Figure S4E). While FLAG-SGK1 readily interacted with HRD1, and was ubiquitylated, these effects were significantly attenuated with FLAG-SGK1GMVAIL (Figure S4F and S4G). To quantitatively assess interactions, we have normalized the HRD1 that has co-immunoprecipitated with FLAG-SGK1 to both the FLAG-SGK1 IP input, as well as the total cell extract expression of HRD1 (Figure S4F). Thus, by not being able to associate with the ER and the ER-localized E3 ubiquitin ligase, HRD1, SGK1GMVAIL has a significantly longer half-life and more potent effects as a pro-hypertrophic kinase in cardiac myocytes.

We posited that during a healthy state, SGK1 is recognized in cardiac myocytes as an ERAD-Out substrate and is therefore efficiently degraded. However, during pressure overload, since ERAD is pathologically impaired (Figure 1I), we posited further that SGK1 is diverted away from the ER, therefore, not degraded as quickly, thus exacerbating cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure (Figure 5A). To test this, we examined SGK1 expression and downstream signaling in the human ischemic HF samples and observed elevated expression of SGK1 and its co-chaperone, GILZ, as well as increased phosphorylation of its known targets NDRG1, NEDD4–2, GSK3β, and FOXO3A (Figure 5B). Similar findings were observed in TAC mouse hearts, where VIMP knockdown decreased TAC-mediated increases in SGK1, and over expression of VIMP but not VIMP−ERAD increased SGK1 levels (Figure 5C; Figure S4H). These results indicate that it is by decreasing the levels of SGK1 in an ERAD-dependent manner that VIMP knockdown moderates cardiac hypertrophy. Consistent with this was our finding that FLAG-SGK1 degradation was enhanced by TAC when VIMP was knocked down (Figure 5D, E). Thus, VIMP knockdown increases SGK1 degradation in ways that are consistent with the moderating effects of VIMP knockdown on cardiac hypertrophy.

Figure 5.

SGK1 is elevated in heart failure and VIMP knockdown enhances its degradation in an ERAD-dependent manner

(A) Schematic detailing the hypothesis that when SGK1 is not degraded at the ER, it leads to pathologic cardiac hypertrophy.

(B and C) WB of LV extracts of healthy or heart failure human myocardial biopsy samples (B) or mouse hearts after sham or TAC (C) for SGK1 and its (or SGK1) phosphorylation targets.

(D and E) WB of FLAG-SGK1 in AMVM isolated from sham or TAC mice (D), or AAV9-Con or AAV9-shVimp mice 6 weeks after TAC. n=3 mice per group.

(F) WB of NRVM treated with siControl or siVimp, infected without or with AdV-FLAG-SGK1. Cell extracts were subjected to FLAG immunoprecipitation (IP) followed by SDS-PAGE and UBQ, HRD1, or FLAG WB. Note that HRD1 was also detected as a higher molecular weight complex with FLAG-SGK1 after FLAG IP (arrow).

(G) Densitometry quantifications of WB in panel F to analyze the UBQ or HRD1 interaction with SGK1 after FLAG IP.

(H) WB of NRVM treated with siControl or siVimp, infected without or with AdV-FLAG-SGK1, and treated with bortezomib (BZ) for 4 hours. Cell extracts were subjected to FLAG IP followed by SDS-PAGE and UBQ, HRD1, or FLAG WB.

(I and J) Densitometry quantifications of WB in panel H to analyze the UBQ (I) or HRD1 (J) interaction with SGK1 after FLAG IP.

Because VIMP’s canonical role in ERAD is to recruit VCP to the cytosolic face of the ER to interact with the HRD137, we assessed whether HRD1 and VCP were required for the enhanced degradation of SGK1 upon VIMP knockdown. As expected, VIMP knockdown accelerated SGK1 degradation in NRVM, but this effect was reversed upon HRD1 or VCP knockdown, implicating a requirement for both HRD1 and VCP for the rapid degradation of SGK1 upon VIMP knockdown (Figure S5A and S5C). In support of this, while VIMP knockdown blunted PE-mediated cardiac hypertrophy and induction of Nppa and Nppb, HRD1 or VCP knockdown ameliorated this effect (Figure S5B and S5D). We next examined whether the effect of VIMP knockdown on SGK1 degradation was associated with a change in the ability of SGK1 to interact with and be ubiquitylated by HRD1. Accordingly, NRVM were infected with AdV-FLAG-SGK1 with or without VIMP knockdown and were then subjected to IP followed by western blots. HRD1 co-immunoprecipitated with FLAG-SGK1, migrating at both its expected molecular weight and as a macromolecular complex with a molecular mass approximating HRD1 and SGK1 together (Figure 5F). However, VIMP knockdown significantly decreased the amount of the FLAG-SGK1/HRD1 complex, and decreased FLAG-SGK1 ubiquitylation which are consistent with enhanced SGK1 degradation upon VIMP knockdown (Figure 5F and 5G). To determine whether the decreased steady-state FLAG-SGK1/HRD1 complex observed upon VIMP knockdown was due to proteasome-mediated degradation of FLAG-SGK1, we used the proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib (BZ). While VIMP knockdown, again, attenuated the steady-state interaction between FLAG-SGK1 and HRD1, as well as total ubiquitylation of SGK1 (Figure 5H, Lanes 3 & 4 vs. Lanes 7 & 8), the FLAG-SGK1 and HRD1 interaction, and ubiquitylation state were significantly greater upon VIMP knockdown in the presence of BZ (Figure 5H–J). These findings imply that knocking down VIMP enhances the HRD1-dependent ubiquitylation and proteasome-mediated degradation of SGK1.

SGK1 is the Mechanistic Link Between VIMP and Cardiac Hypertrophy

We then explored how removing VIMP, a functional initiator of the ERAD complex, enhances ERAD-mediated degradation of the ERAD-Out substrate, SGK1. Accordingly, we assessed the effects of ectopic expression of SGK1 in cardiac myocytes, in vivo, using new recombinant AAV9 encoding either FLAG-SGK1, or a kinase-dead form of SGK1, where lysine 127 has been mutated to methionine rendering it incapable of PI3K-mediated activation26, AAV9-FLAG-SGK1KD (Figure S6A). In shVimp mouse hearts, AAV9-FLAG-SGK1, but not AAV9-FLAG-SGK1KD, effectively promoted cardiac dysfunction (Figure S6B), and hypertrophy (Figure S6C), accumulation of ubiquitylated protein aggregates and downstream SGK1 signaling (Figure S6D). In siVimp-treated NRVM, AdV-SGK1 significantly restored downstream SGK1 signaling and mTORC1 activation (Figure S6E), as well as cardiac myocyte hypertrophy in response to PE (Figure S6F). Finally, treatment with the chemical inhibitor of endogenous SGK1, EMD63868338, significantly attenuated the SGK1 signaling, mTORC1 activation (Figure S6G) and cardiac hypertrophy (Figure S6H) observed in AdV-Vimp treated NRVM. These findings confirmed that VIMP enhances cardiac myocyte growth in an SGK1-dependent manner, and that VIMP knockdown decreases cardiac myocyte growth by enhancing SGK1 degradation.

VIMP Inhibits DERLIN1 From Initiating “ERAD-Out”

Thus far, despite exerting pathological pro-hypertrophic effects in the heart dependent upon it engaging in ERAD in a HRD1 and VCP-dependent manner, VIMP appears not to be required for efficient ERAD of either canonical ERAD-In or non-canonical ERAD-Out substrates in cardiac myocytes. To test this, we examined whether VIMP was required for the interaction between HRD1 and VCP. Interestingly, VIMP knockdown did not affect the interaction between HRD1 and VCP (Figure S7A and S7B), indicating that VIMP is not required for efficient ERAD complex formation in cardiac myocytes, leading us to search for a protein other than VIMP that is required to recruit VCP to the ERAD complex.

VCP interacting proteins that participate in ERAD typically have unique VCP-interacting domains13, 39, and, given that only a select number of ERAD proteins have been shown to interact with, and recruit VCP to the ER (i.e. VIMP, AMFR, UBXD2, UBXD8, and DERLIN1), we examined whether one of them was able to compensate for the increased rate of ERAD and antihypertrophic effects in the absence of VIMP in NRVM. Efficient knockdown of Amfr was demonstrated by western blot (Figure S7C) and Ubxd2 or Ubxd8 via qRT-PCR (Figure S7F and S7H). Co-knockdown of VIMP and either Amfr (Figure S7C), Ubxd2 (Figure S7E), or Ubxd8 (Figure S7G) did not affect SGK1 degradation, or the antihypertrophic effect of VIMP knockdown (Figure S7D and S7I). Accordingly, we focused on DERLIN1.

DERLIN1 interacts with VCP via an SHP motif on its cytosolic-facing carboxy terminus40. Despite being well documented in model cell lines to functionally interact with VIMP to recruit VCP to the ER and enhance ERAD, in cardiac myocytes, knockdown of both VIMP and DERLIN1 effectively reversed siVimp-mediated increases in degradation of both the ERAD-Out substrate, SGK1 (Figure 6A), and the ERAD-In substrate, TCRa (Figure 6B). Furthermore, DERLIN1 knockdown also reversed the antihypertrophic effects of siVimp in NRVM (Figure 6C). This implies that in the absence of VIMP, DERLIN1 is capable of initiating ERAD complex formation and preferentially enhancing ERAD-Out substrate degradation. To address this, we assessed the role of DERLIN1 in the interaction between FLAG-SGK1 and HRD1, as well as the ubiquitylation of SGK1 in NRVM. While VIMP knockdown, again, decreased the interaction between FLAG-SGK1 and HRD1, as well as the total amount of ubiquitin bound to FLAG-SGK1, simultaneous VIMP and DERLIN1 knockdown restored these interactions to Control levels, implying an impaired proteasome-mediated degradation of SGK1 in the absence of DERLIN1 (Figure 6D and 6E). Mechanistically, we hypothesized that VIMP competes with DERLIN1 for binding to VCP. To test this, Cos7 cells were transfected with HA-VCP and increasing plasmid concentrations of FLAG-Vimp. We found that FLAG-Vimp disrupted the DERLIN1-VCP interaction in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6F and 6G). We carried out additional experiments to explore the DERLIN1-VCP interaction further. It has been previously demonstrated that most VCP-interacting proteins bind to the VCP N-Domain, comprising residues 1–187, which is commonly referred to as the co-factor binding domain13. To determine whether VIMP and DERLIN1 competed for binding to the same N-Domain region of VCP, we engineered serial N-terminal truncations of VCP (Figure 6H VCP-mut 1, 2 and 3) and examined how these truncations affected VIMP and DERLIN1 binding to VCP in Cos7 cells. Both VIMP and DERLIN1 bound to VCP and VCP-mut1, however, their interaction was nearly completely abolished with VCP-mut2 and VCP-mut3 (Figures 6I, J and K), implicating the region spanning residues 107–187 in the N-Domain of VCP as being required for binding of both VIMP and DERLIN1 to VCP.

Figure 6.

VIMP displaces DERLIN1 from recruiting VCP to allow for “ERAD-Out” substrate degradation

(A and B) WB of FLAG-SGK1 (A) or HA-TCRa (B) in NRVM transfected with siCon, siVimp, or both siVimp and siDerlin1 and treated with PE for 48 hours.

(C) qPCR for pro-hypertrophic markers Nppa and Nppb in NRVM transfected with siCon, siVimp, or both siVimp and siDerlin1 and treated with PE for 48 hours. Bar graph shows mean ± SEM; n=3 NRVM cultures repeated from at least two independent NRVM isolations per group. *p<0.01 as determined by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

(D) WB of NRVM treated with siCon, siVimp, or both siVimp and siDerlin1 and infected without or with AdV-FLAG-SGK1. Cell extracts were subjected to FLAG IP followed by SDS-PAGE and UBQ, HRD1, or FLAG WB.

(E) Densitometry quantifications of WB in panel D to analyze the UBQ or HRD1 interaction with SGK1 after FLAG IP.

(F) WB of Cos7 cells transfected with HA-VCP and either low-dose (LD; 6ng) or high-dose (HD; 100ng) of FLAG-Vimp plasmid. Cell extracts were subjected to HA IP followed by SDS-PAGE and DERLIN1, HA, or VIMP WB.

(G) Densitometry quantifications of WB in panel F to analyze the Derlin1 interaction with VCP after HA IP.

(H) Schematic detailing VCP mutants (mut) with serial truncations in its reported co-factor binding N domain.

(I and J) WB of Cos7 cells transfected with HA-VCP truncations and either FLAG-Vimp (I) or Flag-Derlin1 (J). Cell extracts were subjected to FLAG IP followed by SDS-PAGE and HA, VIMP, or DERLIN1 WB.

(K) Densitometry quantifications of WB in panels I and J to analyze the interaction between VIMP or DERLIN1 with serial VCP truncation mutants.

VIMP Regulates ERAD in Cardiac Myocytes Differently than in Non-myocytes

Finally, since VIMP has been well characterized as an obligate ERAD component in dividing cell lines, we explored whether it was critical for ERAD-In and ERAD-Out in immortalized (HEK293 cells) and dividing primary cells (cardiac fibroblasts). In accordance with VIMP’s previously demonstrated role12, 14, VIMP knockdown significantly impaired ERAD-In degradation of HA-TCRα (Figure S8A and S8B). Further, we isolated cardiac fibroblasts from the same hearts from which we isolated cardiac myocytes and performed comparative side-by-side studies. As demonstrated by western blot and densitometry, unlike cardiac myocytes, VIMP knockdown significantly slowed FLAG-SGK1 degradation in cardiac non-myocytes (Figure S8C and S8D), indicating a unique functional role specific to cardiac myocytes for VIMP as a regulator of ERAD and cellular hypertrophy. To understand the different functions of VIMP in cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts isolated from the same hearts, we assayed the relative mRNA levels of Vimp and Derlin1 via qRT-PCR, finding that, while Vimp was more highly expressed in cardiac fibroblasts, Derlin1 was more highly expressed in cardiac myocytes (Figure S8E). It’s of further relevance to note that while all ERAD components were decreased in late-stage severe human and mouse heart failure with a left ventricular ejection fraction <20% (Figure 1), only Derlin1 was significantly decreased earlier in the disease progression in samples with an ejection fraction of ~35% (Figure 3F). Thus, DERLIN1 downregulation appears to be uniquely causally linked to cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. In summation, these findings suggest that in cardiac myocytes, DERLIN1 is a preferential functional initiator of ERAD, and VIMP exerts pro-hypertrophic effects by displacing DERLIN1 from VCP, which inhibits ERAD-mediated degradation of SGK1.

Discussion:

In response to pressure overload and pathological stimuli, cardiac myocytes hypertrophy to maintain adequate output1. This growth requires increases in protein synthesis, which increases the protein-folding burden; if protein synthesis and folding are unbalanced, cardiac myocyte death and eventual heart failure can result1–3. Previously, we’ve demonstrated that loss-of-function of the trans-ER membrane E3 ubiquitin ligase, HRD1, exacerbates pathological cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload, presumably because of its role in ERAD19. Thus, here we posited that a well described functional initiator of ERAD, VIMP, would be an appropriate target to focus on to interrogate functional roles for ERAD as a complex in the myocardium. We anticipated that VIMP loss-of-function, much like HRD1 loss-of-function, would exacerbate pathological cardiac hypertrophy; however, we were surprised to discover that VIMP loss-of-function had the opposite effect, where it protected against cardiac hypertrophy and increased degradation of proteotoxic misfolded protein aggregates. Subsequently, we observed a vexing result, finding paradoxically that both VIMP loss- and gain-of-function increased degradation rates of canonical ERAD substrates, while VIMP loss- and gain-of-function had opposing effects on cardiac hypertrophy. Thus, we concluded that canonical ERAD must not always be directly related to alleviating pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

Since canonical ERAD did not appear to align with the effects of VIMP on cardiac hypertrophy, we searched for non-canonical effects of ERAD that might be regulated differently than canonical ERAD, focusing on a potential non-canonical ERAD substrate, SGK1. In renal epithelial cells, SGK1, a cytosolic kinase, has been described to localize to the ER where it is ubiquitylated by HRD1, and then degraded via the ubiquitin proteasome system28–31. Moreover, SGK1 has been shown to be involved in mTOR-mediated growth of several non-cardiac cell types, such as cancer cells36, 41. Additionally, the Rosenzweig group had previously reported that hyperactive SGK1 can promote pathological cardiac hypertrophy and lethal ventricular arrythmias26, 27. Here, we defined how SGK1 is uniquely regulated by VIMP, such that VIMP inhibits SGK1 degradation, which leads to heart failure. We believe that this is a landmark finding, as SGK1 represents an entirely new class of ERAD that is defined by substrates not requiring retrotranslocation across the ER membrane. We propose that in cardiac myocytes DERLIN1 acts as the functional initiator of this newly defined ERAD-Out and recognizes said substrates via its cytosolic-facing DBR motif while, subsequently, recruiting VCP to the ER surface via its separate SHP motif to regulate SGK1 degradation and ameliorate cardiac hypertrophy (Figure S8F). While, to the best of our knowledge, SGK1 is the first ERAD-Out substrate to be described, there is precedent for the existence of other ERAD-Out substrates, as the DBR motif of DERLIN1 was first described to bind to a mutant form of SOD1 frequently found in familial ALS42. Furthermore, other intriguing targets have been reported to target to the ER, including p5343 and mTOR22, 44, although their roles at the ER surface have yet to be defined. Given our observation that ERAD-Out-mediated degradation of SGK1 occurs in various cell types, characterizing the substrates regulated by ERAD-Out could have important therapeutic implications.

Finally, it is possible that VIMP could be acting to promote other related ER-quality control mechanisms, namely ER-phagy. ER-phagy is thought to be a highly orchestrated process that is regulated by specific ER receptors unique to the type of ER network (i.e., ER sheets vs ER tubuli)46. This is especially intriguing in cardiac myocytes, given the presence of both ER and SR. As it relates to ERAD, a form of micro-er-phagy has been described in yeast whereby select proteins as opposed to whole ER fragments are degraded utilizing these same ER-phagy receptors, which implicate ER-phagy as a preferred adaptive degradation mechanism if ERAD is impaired47. While greatly understudied in the heart, studies of VIMP’s potential role in ER-phagy could potentially explain how both VIMP knockdown and overexpression can elicit the same effect of enhancing canonical ERAD substrate degradation.

In summary, VIMP negatively regulates ERAD-Out-mediated degradation of the pro-hypertrophic kinase, SGK1, via competing with DERLIN1 as a functional initiator of ERAD. Despite demonstrating the global occurrence of ERAD-Out in proliferative cells, such as cardiac fibroblasts, cardiac myocytes have uniquely developed the ability to utilize ERAD-Out instead of canonical ERAD-In to preserve cellular integrity, proteostasis, and mitigate pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Accordingly, further studies of ERAD-Out in the heart should provide important new information that could be used to develop new and potentially more efficacious therapeutics for CVD and heart failure.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective:

What Is New?

This is the first study to demonstrate that ER associated (protein) degradation (ERAD) is responsible for degrading and thus, regulating the levels of a cytosolic, non-ER protein.

The results reported here describe a new mechanism mediating the pathological growth of the heart such that in the healthy heart, SGK1 levels are low due to ERAD-mediated degradation, while in the setting of pathology, ERAD-mediated degradation of SGK1 is disrupted, allowing the pro-growth kinase to accumulate and contribute to pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

ERAD-mediated degradation of SGK1 is a previously unstudied molecular pathway that contributes to pathological cardiac hypertrophy in mouse models.

We found that a variety of proteins that constitute the ERAD machinery were decreased in both mouse and human heart failure samples, while SGK1 was increased, supporting the possibility that SGK1 is a contributor to the disease phenotype.

These studies could lead to the development of new therapeutic approaches for managing pathological cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure that target the ERAD to restore efficient SGK1 degradation.

Acknowledgements-

We acknowledge Ms. Bernadine Sadauskas and Ms. Tina Allen for excellent administrative support of the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix Translational Cardiovascular Research Center.

Sources of Funding-

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health to EAB (HL140850; 1F31HL140850) and CCG (HL135893; HL141463; HL149931), the American Heart Association to EAB (17PRE33670796), the University of Arizona Research Innovation and Impact, the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson Sarver Heart Center, and the University of Arizona Bio5 Institute to EAB, and the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix Translational Cardiovascular Research Center to CCG.

Non-standard Abbreviations:

- AAV9

adeno-associated virus serovar 9

- AMFR

autocrine motility factor receptor (AMFR) ubiquitin E3-ligase

- AMVM

adult mouse ventricular myocyte

- Atp2a2

ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 (SERCA2)

- BZ

bortezomib

- CHX

cycloheximide

- Col1a1

collagen type I alpha 1 chain

- DERLIN1

degradation in endoplasmic reticulum protein 1

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

endoplasmic reticulum associated degradation

- ERAD-C

endoplasmic reticulum associated degradation-cytosol

- ERAD-L

endoplasmic reticulum associated degradation-lumen

- ERAD-M

endoplasmic reticulum associated degradation-membrane

- FLAG

FLAG epitope

- FOXO3A

forkhead box O3

- GSK3β

glycogen synthase 3-beta

- HA

hemagglutinin

- Hrd1

HMGCoA reductase 1

- LV

left ventricle

- ma1AT

variant-null Hong Kong alpha1-antitrypsin

- mTORC1

mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1

- Myh7

myosin heavy chain 7

- NDRG1

N-myc Downstream-Regulated Gene 1

- NEDD4–2

neural precursor cell-expressed developmentally downregulated gene 4

- NRVM

neonatal rat ventricular myocyte

- PAO

preamyloid oligomers

- PE

phenylephrine

- Pstn

periostin

- Sel1l

suppressor/enhancer of lin-12-like (Sel1L)

- SelenoS, SelS

Selenoprotein S

- SGK1

serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1

- SGK1KD

serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 kinase dead

- SOD1

superoxide dismutase 1

- TAC

transaortic constriction

- TCRa

T-cell receptor subunit alpha

- UBXD2

UBX domain-containing protein 4

- UBXD8

UBX domain-containing protein 4

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- VCP

valosin containing protein

- VIMP

VCP-interacting membrane protein

- VIMP−ERAD

VCP-interacting membrane protein ERAD inactive

Footnotes

Disclosures - None

References:

- 1.Frey N, Katus HA, Olson EN, Hill JA. Hypertrophy of the heart: a new therapeutic target? Circulation. 2004. Apr 6;109(13):1580–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrieta A, Blackwood EA, Glembotski CC. ER Protein Quality Control and the Unfolded Protein Response in the Heart. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2018;414:193–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackwood EA, Bilal AS, Stauffer WT, Arrieta A, Glembotski CC. Designing Novel Therapies to Mend Broken Hearts: ATF6 and Cardiac Proteostasis. Cells. 2020. Mar 3;9(3):602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011. Nov 25;334(6059):1081–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brodsky JL. Cleaning up: ER-associated degradation to the rescue. Cell. 2012. Dec 7;151(6):1163–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vembar SS, Brodsky JL. One step at a time: endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008. Dec;9(12):944–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brodsky JL, Wojcikiewicz RJ. Substrate-specific mediators of ER associated degradation (ERAD). Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009. Aug;21(4):516–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shchedrina VA, Zhang Y, Labunskyy VM, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Structure-function relations, physiological roles, and evolution of mammalian ER-resident selenoproteins. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010. Apr 1;12(7):839–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Rozovsky S. Contribution of selenocysteine to the peroxidase activity of selenoprotein S. Biochemistry. 2013. Aug 20;52(33):5514–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shchedrina VA, Everley RA, Zhang Y, Gygi SP, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Selenoprotein K binds multiprotein complexes and is involved in the regulation of endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2011. Dec 16;286(50):42937–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turanov AA, Shchedrina VA, Everley RA, Lobanov AV, Yim SH, Marino SM, Gygi SP, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Selenoprotein S is involved in maintenance and transport of multiprotein complexes. Biochem J. 2014. Sep 15;462(3):555–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leto DE, Morgens DW, Zhang L, Walczak CP, Elias JE, Bassik MC, Kopito RR. Genome-wide CRISPR Analysis Identifies Substrate-Specific Conjugation Modules in ER-Associated Degradation. Mol Cell. 2019. Jan 17;73(2):377–389.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchberger A, Schindelin H, Hänzelmann P. Control of p97 function by cofactor binding. FEBS Lett. 2015. Sep 14;589(19 Pt A):2578–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JH, Kwon JH, Jeon YH, Ko KY, Lee SR, Kim IY. Pro178 and Pro183 of selenoprotein S are essential residues for interaction with p97(VCP) during endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. J Biol Chem. 2014. May 16;289(20):13758–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Lutsey PL, Mackey JS, Matchar DB, Matsushita K, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, O’Flaherty M, Palaniappan LP, Pandey A, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Ritchey MD, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018. Mar 20;137(12):e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu Y, Gao Y, Zhang M, Deng KY, Singh R, Tian Q, Gong Y, Pan Z, Liu Q, Boisclair YR, Long Q. Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated Degradation (ERAD) Has a Critical Role in Supporting Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion in Pancreatic β-Cells. Diabetes. 2019. Apr;68(4):733–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu B, Jiang L, Huang T, Zhao Y, Liu T, Zhong Y, Li X, Campos A, Pomeroy K, Masliah E, Zhang D, Xu H. ER-associated degradation regulates Alzheimer’s amyloid pathology and memory function by modulating γ-secretase activity. Nat Commun. 2017. Nov 13;8(1):1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hetz C, Saxena S. ER stress and the unfolded protein response in neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017. Aug;13(8):477–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doroudgar S, Völkers M, Thuerauf DJ, Khan M, Mohsin S, Respress JL, Wang W, Gude N, Müller OJ, Wehrens XH, Sussman MA, Glembotski CC. Hrd1 and ER-Associated Protein Degradation, ERAD, are Critical Elements of the Adaptive ER Stress Response in Cardiac Myocytes. Circ Res. 2015. Aug 28;117(6):536–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hahn VS, Knutsdottir H, Luo X, Bedi K, Margulies KB, Haldar SM, Stolina M, Yin J, Khakoo AY, Vaishnav J, Bader JS, Kass DA, Sharma K. Myocardial Gene Expression Signatures in Human Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation. 2021. Jan 12;143(2):120–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bilal AS, Blackwood EA, Thuerauf DJ, Glembotski CC. Optimizing Adeno-Associated Virus Serotype 9 for Studies of Cardiac Chamber-Specific Gene Regulation. Circulation. 2021. May 18;143(20):2025–2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blackwood EA, Hofmann C, Santo Domingo M, Bilal AS, Sarakki A, Stauffer W, Arrieta A, Thuerauf DJ, Kolkhorst FW, Müller OJ, Jakobi T, Dieterich C, Katus HA, Doroudgar S, Glembotski CC. ATF6 Regulates Cardiac Hypertrophy by Transcriptional Induction of the mTORC1 Activator, Rheb. Circ Res. 2019. Jan 4;124(1):79–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sciarretta S, Volpe M, Sadoshima J. Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in cardiac physiology and disease. Circ Res. 2014. Jan 31;114(3):549–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabatini DM. Twenty-five years of mTOR: Uncovering the link from nutrients to growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017. Nov 7;114(45):11818–11825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong Y, Shen H, Wang Y, Yang Y, Yang P, Fang S. Identification of ERAD components essential for dislocation of the null Hong Kong variant of α−1-antitrypsin (NHK). Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015. Mar 6;458(2):424–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aoyama T, Matsui T, Novikov M, Park J, Hemmings B, Rosenzweig A. Serum and glucocorticoid-responsive kinase-1 regulates cardiomyocyte survival and hypertrophic response. Circulation. 2005. Apr 5;111(13):1652–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das S, Aiba T, Rosenberg M, Hessler K, Xiao C, Quintero PA, Ottaviano FG, Knight AC, Graham EL, Boström P, Morissette MR, del Monte F, Begley MJ, Cantley LC, Ellinor PT, Tomaselli GF, Rosenzweig A. Pathological role of serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 in adverse ventricular remodeling. Circulation. 2012. Oct 30;126(18):2208–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arteaga MF, Wang L, Ravid T, Hochstrasser M, Canessa CM. An amphipathic helix targets serum and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1 to the endoplasmic reticulum-associated ubiquitin-conjugation machinery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006. Jul 25;103(30):11178–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brickley DR, Mikosz CA, Hagan CR, Conzen SD. Ubiquitin modification of serum and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase-1 (SGK-1). J Biol Chem. 2002. Nov 8;277(45):43064–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bogusz AM, Brickley DR, Pew T, Conzen SD. A novel N-terminal hydrophobic motif mediates constitutive degradation of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase-1 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. FEBS J. 2006. Jul;273(13):2913–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soundararajan R, Wang J, Melters D, Pearce D. Glucocorticoid-induced Leucine zipper 1 stimulates the epithelial sodium channel by regulating serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1 stability and subcellular localization. J Biol Chem. 2010. Dec 17;285(51):39905–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webster MK, Goya L, Ge Y, Maiyar AC, Firestone GL. Characterization of sgk, a novel member of the serine/threonine protein kinase gene family which is transcriptionally induced by glucocorticoids and serum. Mol Cell Biol. 1993. Apr;13(4):2031–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lang F, Artunc F, Vallon V. The physiological impact of the serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009. Sep;18(5):439–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray JT, Campbell DG, Morrice N, Auld GC, Shpiro N, Marquez R, Peggie M, Bain J, Bloomberg GB, Grahammer F, Lang F, Wulff P, Kuhl D, Cohen P. Exploitation of KESTREL to identify NDRG family members as physiological substrates for SGK1 and GSK3. Biochem J. 2004. Dec 15;384(Pt 3):477–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Debonneville C, Flores SY, Kamynina E, Plant PJ, Tauxe C, Thomas MA, Münster C, Chraïbi A, Pratt JH, Horisberger JD, Pearce D, Loffing J, Staub O. Phosphorylation of Nedd4-2 by Sgk1 regulates epithelial Na(+) channel cell surface expression. EMBO J. 2001. Dec 17;20(24):7052–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lister K, Autelitano DJ, Jenkins A, Hannan RD, Sheppard KE. Cross talk between corticosteroids and alpha-adrenergic signalling augments cardiomyocyte hypertrophy: a possible role for SGK1. Cardiovasc Res. 2006. Jun 1;70(3):555–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ye Y, Shibata Y, Yun C, Ron D, Rapoport TA. A membrane protein complex mediates retrotranslocation from the ER lumen into the cytosol. Nature. 2004. Jun 24;429(6994):841–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ackermann TF, Boini KM, Beier N, Scholz W, Fuchss T, Lang F. EMD638683, a novel SGK inhibitor with antihypertensive potency. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;28(1):137–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van den Boom J, Meyer H. VCP/p97-Mediated Unfolding as a Principle in Protein Homeostasis and Signaling. Mol Cell. 2018. Jan 18;69(2):182–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenblatt EJ, Olzmann JA, Kopito RR. Derlin-1 is a rhomboid pseudoprotease required for the dislocation of mutant α−1 antitrypsin from the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011. Sep 11;18(10):1147–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruhn MA, Pearson RB, Hannan RD, & Sheppard KE (2010). Second AKT: the rise of SGK in cancer signalling. Growth factors (Chur, Switzerland), 28(6), 394–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishitoh H, Kadowaki H, Nagai A, Maruyama T, Yokota T, Fukutomi H, Noguchi T, Matsuzawa A, Takeda K, Ichijo H. ALS-linked mutant SOD1 induces ER stress- and ASK1-dependent motor neuron death by targeting Derlin-1. Genes Dev. 2008. Jun 1;22(11):1451–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamasaki S, Yagishita N, Sasaki T, Nakazawa M, Kato Y, Yamadera T, Bae E, Toriyama S, Ikeda R, Zhang L, Fujitani K, Yoo E, Tsuchimochi K, Ohta T, Araya N, Fujita H, Aratani S, Eguchi K, Komiya S, Maruyama I, Higashi N, Sato M, Senoo H, Ochi T, Yokoyama S, Amano T, Kim J, Gay S, Fukamizu A, Nishioka K, Tanaka K, Nakajima T. Cytoplasmic destruction of p53 by the endoplasmic reticulum-resident ubiquitin ligase ‘Synoviolin’. EMBO J. 2007. Jan 10;26(1):113–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schewe DM, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. ATF6alpha-Rheb-mTOR signaling promotes survival of dormant tumor cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008. Jul 29;105(30):10519–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu R, Yang G, Cao Z, Shen K, Zheng L, Xiao J, You L, & Zhang T (2020). The prospect of serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 (SGK1) in cancer therapy: a rising star. Therapeutic advances in medical oncology, 12, 1758835920940946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He L, Qian X, Cui Y. Advances in ER-Phagy and Its Diseases Relevance. Cells. 2021. Sep 6;10(9):2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schäfer JA, Schessner JP, Bircham PW, Tsuji T, Funaya C, Pajonk O, Schaeff K, Ruffini G, Papagiannidis D, Knop M, Fujimoto T, & Schuck S (2020). ESCRT machinery mediates selective microautophagy of endoplasmic reticulum in yeast. The EMBO journal, 39(2), e102586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bedi KC Jr, Snyder NW, Brandimarto J, Aziz M, Mesaros C, Worth AJ, Wang LL, Javaheri A, Blair IA, Margulies KB, Rame JE. Evidence for Intramyocardial Disruption of Lipid Metabolism and Increased Myocardial Ketone Utilization in Advanced Human Heart Failure. Circulation. 2016. Feb 23;133(8):706–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin JK, Blackwood EA, Azizi K, Thuerauf DJ, Fahem AG, Hofmann C, Kaufman RJ, Doroudgar S, Glembotski CC. ATF6 Decreases Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Damage and Links ER Stress and Oxidative Stress Signaling Pathways in the Heart. Circ Res. 2017;120:862–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blackwood EA, Bilal AS, Azizi K, Sarakki A, Glembotski CC. Simultaneous Isolation and Culture of Atrial Myocytes, Ventricular Myocytes, and Non-Myocytes from an Adult Mouse Heart. J Vis Exp. 2020. Jun 14;(160): 10.3791/61224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glembotski CC, Thuerauf DJ, Huang C, Vekich JA, Gottlieb RA, Doroudgar S. Mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor protects the heart from ischemic damage and is selectively secreted upon sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium depletion. J Biol Chem. 2012. Jul 27;287(31):25893–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplemental Material. The data, analytical methods, and study materials will be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedures.