Abstract

Individuals living in areas where Plasmodium falciparum is endemic experience numerous episodes of infection. These episodes may or may not be symptomatic, with the outcome depending on a combination of parasite and host factors, several of which are poorly understood. One factor is believed to be the particular alleles of several parasite proteins to which the host is capable of mounting protective immune responses. We report a study examining antibody responses to MSP2 in 15 semi-immune teenagers and adults living in the Khanh-Hoa area of southern-central Vietnam, where P. falciparum is highly endemic; subjects were serially infected with multiple strains of P. falciparum. The MSP2 alleles infecting these subjects were determined by nucleotide sequencing. A total of 62 MSP2 genes belonging to both dimorphic families were identified, of which 33 contained distinct alleles, with 61% of the alleles being detected once. Clear changes in the repertoire occurred between infections. Most infections contained a mixture of parasites expressing MSP2 alleles from both dimorphic families. Two examples of reinfection with a strain expressing a previously encountered allele were detected. Significant changes in antibody levels to various regions of MSP2 were detected over the course of the experiment. There was no clear relation between the infecting form of MSP2 and the ensuing antibody response. This study highlights the complexity of host-parasite relationship for this important human pathogen.

In areas of endemicity, immunity to Plasmodium falciparum malaria develops slowly and is hardly ever complete. One explanation for this phenomenon is that many different parasite strains, differing in the sequences of key protective antigens, circulate within any given area of endemicity. If immunity to infection is strain specific, then a state of generalized immunity would develop once exposure had occurred to a large enough sample of the many distinct parasite strains circulating in that region (2, 11). Thus, according to this explanation, the extensive degree of polymorphism noted in many surface antigens contributes to immune evasion and aids parasite pathogenesis. This polymorphism would also appear to restrict the effectiveness of subunit vaccines against P. falciparum infection if these variable proteins are included (7, 21). Although there is little direct evidence for this hypothesis from human studies, studies of vaccinated animals consistently demonstrate that immunity to blood stage infection is less effective against parasites expressing variant forms of the protective immunogen (6, 22). Presumably, the extent of such subversion of the immune response would depend on the number of distinct antigenic forms circulating in an area of endemicity. However, there is a paucity of nucleotide sequence information regarding the size of the antigenic repertoire of naturally circulating parasite strains in different areas where malaria is endemic. This issue needs to be addressed to provide information on the distribution of strains, and it has major implications for vaccine design (7, 33). If strain variation is an important component of immune evasion, vaccines incorporating variant proteins might have to include a full reportoire of variant forms in order to provide full protection against infection.

Merozoite surface protein 2 (MSP2), which is encoded by a single-copy gene, is a 45- to 52-kDa integral membrane glycoprotein anchored on the surface of the merozoite by a glycosylphosphatidylinosital (GPI) moiety. MSP2 consists of highly conserved N (43 residues) and C (74 residues) termini flanking a central variable region. This central variable region consists of centrally located repeats, which are flanked by nonrepetitive sequences. MSP2 sequences are assigned to one of two families, FC27 and IC-1/3D7, on the basis of the nonrepetitive sequences (12, 28–30). The central repeats, which vary in number, length, and sequence among isolates, define individual MSP2 alleles. The central repeat region of the FC27 allele family is characterized by variants of a 32-residue motif, occurring in one to four tandem copies, followed by a characteristic 7-mer residue sequence and by one to five tandem copies of a variable 12-mer sequence. The 3D7 allele family is characterized by shorter sequence repeats of 3 to 10 residues with a preponderance of glycine, valine, alanine and serine and also by the presence or absence of short sequence stretches within the C-terminal nonrepetitive variable region (7, 11, 15, 16).

Several lines of evidence implicate MSP2 as a target of host protective immune responses, including its exposed location on the merozoite surface and growth inhibition by a specific monoclonal antibody to MSP2 (8). Mice immunized with conserved regions of P. falciparum MSP2 have been protected against challenge with the rodent parasite Plasmodium chabaudi (26). Antibodies to MSP2 are frequently detected in sera from individuals living in areas of endemicity (21, 32, 34), and the presence of immunoglobulin G3 (IgG3) antibodies to the 3D7 family MSP2 protein was negatively associated with the risk of clinical malaria in the Gambia and in Papua New Guinea (1, 31). Based on these results, human trials of a multisubunit vaccine containing MSP2 have commenced (24).

The degree of antibody reactivity to MSP2 is sequence dependent (21) so that, for example, antibodies that are inhibitory to parasites expressing a particular form of MSP2 do not inhibit parasites expressing a different form (25). Field studies on parasite genomic DNA extracted from infected blood suggest that there is a large repertoire of circulating strains (7, 10, 11, 15). Much of these data come from various PCR methods, such as restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of PCR products and Southern hybridization using MSP2-specific probes, and rely on size differences between repeat regions. Such methods underestimate the true level of diversity, which includes sequence differences due to mutations (11, 17, 18, 20, 30, 36). Nucleotide sequencing provides a more accurate estimate of the antigenic microheterogeneity of MSP2. Several studies have examined MSP2 alleles in field populations by nucleotide sequencing (3, 7, 10, 15, 20). A longitudinal survey of MSP2 genes in the Oksibil region of Irian Jaya reported that, over 29 months, MSP2 genes belonging to both major allelic families were observed at all time points (7). In the case of the FC27 MSP2 family, the majority of individuals were infected by parasites expressing the same form of MSP2. Infections with parasites expressing 3D7 MSP2 family alleles were more heterogeneous. No MSP2 alleles observed at the earlier time point were detectable at the later time point, either for the population as a whole or for individuals who were assayed at both time points. In no subjects was reinfection by a parasite expressing a previously encountered form of MSP2 detected. These results were interpreted as being consistent with the possibility that infection induces a form of strain-specific immune response against the MSP2 antigen, which biases against reinfection by parasites bearing identical forms of MSP2 (7).

No studies have yet combined a detailed examination of MSP2 diversity with an examination of antibody responses in the infected individuals. In this study, we have documented the MSP2 sequence in a group of individuals living in the Khanh-Hoa region of high endemicity of southern-central Vietnam. The study examined a group of 15 teenagers and adults who were identified as parasitemic at the commencement of the study. After drug cure, the subjects were followed until reinfection occurred sometime in the next 1 to 5 months. The MSP2 sequence of all infecting parasites has been determined, and antibody responses were measured at the times of infection and 28 days after the second infection began. This study documents the extreme complexity of multiple infection by parasite strains expressing a polymorphic antigen and the consequent antibody response to this putative protective antigen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasite isolates and genomic DNA extraction.

One-milliliter blood samples were collected with informed consent from individuals living in an area where malaria is highly endemic, the Khanh-Nam Commune of the Khanh Hoa Province of southern-central Vietnam, which is located 60 km inland from the coastal city of Nha Trang, during the period between 27 June 1994 and 17 August 1994. Three species of human malaria are endemic to this area. Surveys taken at the time of this study showed slide positivity rates between 25 and 30%, with approximately 60% of these infections due to P. falciparum, 30% to Plasmodium vivax, and 10% to Plasmodium malaria. Most teenagers and adults in this region are semi-immune, based on the observation that approximately half of the parasitemic episodes were associated with symptoms of malaria, such as fever or headache. All individuals were identified as being infected with P. falciparum by thick smears at the commencement of the study (T0 sample). After radical treatment with quinine sulfate (10 mg/kg of body weight three times a day, days 0 to 3), doxycycline hyclate (100 mg twice a day, days 0 to 10), and primaquine phosphate (30 mg once a day, days 0 to 14), volunteers were monitored by daily symptom questioning and weekly blood smears until reinfection occurred, at which time a blood sample (T1) was taken and volunteers were treated with mefloquine and monitored for resolution of parasitemia and collection of a second blood sample 28 days later (T28). Time to reinfection varied between 2 to 4 months. These volunteers were selected from a larger cohort of 115 individuals because they harbored patent P. falciparum malaria prior to radical cure and then became slide positive for P. falciparum a second time during the period of surveillance. No volunteers had recurrent parasitemia during the 28-day period following radical cure or following mefloquine treatment. In our experience, the intensive regimen used for radical cure has never failed to eliminate all malaria parasites, including hypnozoites; thus, recurrent parasitemias in all cases represented new infections. Subject details are outlined in Table 1. Infected red cells were stored in 8 M guanidine hydrochloride–0.1 M sodium acetate solution as previously described (15). P. falciparum genomic DNA was extracted from these samples by using the method detailed previously (7).

TABLE 1.

Details of subjects, the time to infection, and MSP2 alleles identified in the infected samples

| Subject | Age (yr)a | Sex | Days (T0–T1)b |

MSP2 allele(s) detectedd

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0, FC27 | T0, 3D7 | T1, FC27 | T1, 3D7 | ||||

| A | 34 | M | 102 | VN1 | VN24 | VN6, VN12 | VN26 |

| B | 37 | M | 121 | VN1, VN4 | VN17 | VN10 | VN27 |

| C | 40 | M | 46 | VN1 | Neg | VN11 | VN17, VN27, VN28 |

| D | 38 | M | 108 | Negc | VN18 | VN5 | VN22, VN30 |

| E | 30 | M | 46 | VN1 | Neg | VN9 | VN30 |

| F | 24 | M | 139 | Neg | VN20 | VN1 | VN29 |

| G | 12 | M | 40 | Neg | VN25 | Neg | VN32 |

| H | 17 | M | 135 | VN7 | VN25 | VN6 | VN32 |

| I | 17 | M | 94 | VN5 | Neg | VN3, VN5, VN6 | VN18, VN30 |

| J | 46 | F | 148 | Neg | VN23 | VN7 | VN22 |

| K | 16 | M | 144 | VN6 | VN16, VN24 | Neg | VN14 |

| L | 14 | F | 86 | VN6 | VN22 | Neg | VN33 |

| M | 13 | M | 92 | VN3 | VN15 | VN13 | VN18, VN30 |

| N | 28 | M | 37 | VN8 | VN21, VN25 | VN6 | VN31 |

| O | 14 | M | 84 | Neg | VN19 | VN2 | VN25, VN30, VN32 |

Age in years, at January 1994.

Time period (days) between the infection time points T0 and T1.

Neg, negative. The subject's blood was negative for MSP2 after repeated PCR amplification with family-specific primers.

T0, initial P. falciparum infection (before drug treatment). T1, subsequent P. falciparum infection (after drug cure).

PCR amplification of MSP2 genes and nucleotide sequencing.

All PCR amplifications employed in this study, together with sequences of all primers used, have been described (7). Two forms of nested PCR amplification were carried out: (i) nested conserved PCR amplified near-full-length MSP2 DNA and provided a rough estimate of the number of MSP2 products and (ii) nested family-specific PCR amplifications were used to amplify either the FC27 or 3D7 family alleles alone. Nucleotide sequencing was performed as previously described (7). The nomenclature for all MSP2 alleles in this study consists of the letters VN followed by numbers 1 to 33, allocated by the order of discovery. FC27 alleles were assigned VN1 to VN13, and 3D7 alleles were assigned VN14 to VN33.

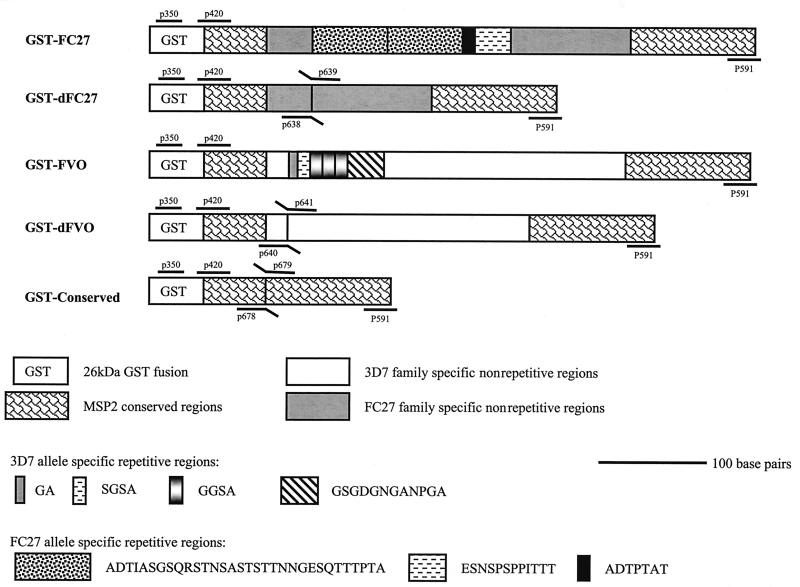

Construction of recombinant MSP2 proteins.

Five recombinant MSP2 proteins were produced in Escherichia coli cells as fusions to glutathione S-transferase (GST) in pGEX vectors (27). Two correspond to near-full-length forms of FC27 and 3D7 allele families with the indicated central repeat regions (Fig. 1). The other three proteins are truncated versions lacking particular sequences. Two proteins contain the nonrepetitive family-specific regions but lack the central repeats (dFC27 and dFVO, respectively), whereas the third contains N-terminal and C-terminal conserved sequences only. Clones were generated by a combination of PCR, splice overlap extension (14), and conventional cloning techniques, using either FC27 or FVO genomic DNA as template. Constructs were sequenced to confirm the frame. Expression of recombinant proteins was performed as described previously (27, 35).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the recombinant MSP2 proteins. GST-FC27 and GST-FVO are GST fusions of two near-full-length MSP2 proteins and represent the 3D7 family and the FC27 family, respectively. The amino acid sequences of the central repeats are indicated. GST-dFC27 and GST-dFVO are two derivative proteins lacking the central allele-specific repeats but containing the conserved and family-specific dimorphic regions. The GST-Conserved construct is a fusion of the conserved N and C termini regions alone. The schematic also shows the location of the primers on the corresponding MSP2 gene sequences of each family, which were used in DNA amplification of each MSP2 construct.

ELISA.

For the detection of MSP2-specific total Ig antibodies, microtiter plates (Immulon-2; Dynex Technologies Inc. Chantilly, Va.) were coated overnight at 4°C with 50 μl of recombinant antigen/well at 1 μg/ml in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) blocked for 1 h at room temperature (RT) with 400 μl of blocking buffer (5% [wt/vol] skim milk powder in PBS, 0.05% Tween 20)/well. Sera were diluted 1:5,000 in blocking buffer and incubated at 4°C overnight. Plates were washed five times with PBS–0.05% Tween 20, and 50 μl of diluted serum was added to duplicate wells and incubated at RT for 2 h. The plates were washed and incubated for 2 h at RT with 50 μl of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated sheep anti-human Ig antibody (Silenus Laboratories, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia)/well diluted 1:2,000 in blocking buffer, followed by washing and addition of 75 μl of substrate solution of 1-mg/ml p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.)/well dissolved in 0.1 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) with 1 mM MgCl2 for 2 h at RT. The absorbance (optical density [OD]) of each well was measured at a wavelength of 405 nm in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate reader (Model 450 Microplate reader; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Each serum sample was tested against GST as a negative control. Specific reactivity was calculated by subtracting the OD value for GST from the value obtained for the fusion protein. For the detection of a specific IgG subclass, isotype-specific ELISA was performed essentially as described above using serum dilutions of 1:200. The subclasses measured were IgG1 (Fab specific) (clone SG-16), IgG2 (clone HP-6014), IgG3 (clone HP-6050), and IgG4 (clone HP-6025), all from Sigma Chemical Co. In light of the affinity differences between isotype-specific monoclonal antibodies, adjustment of the isotype-specific OD values was carried by calibrating the assay by using a reference serum (Human Standard Serum NOR-01; Nordic Immunology). The following derived compensation factors were used to adjust the ELISA values: 1 (IgG1), 0.37 (IgG2), 1.07 (IgG3), and 1.71 (IgG4). Positive sera for total Ig and for each isotype were defined as those yielding OD greater than 0.1, which was above the normal range (mean + 2 standard deviations) for control sera, which were taken from 30 Melbourne, Australia individuals with no history of malaria infection.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences determined were submitted to GenBank under accession no. AF104684 to AF104717.

RESULTS

Fifteen malaria-infected inhabitants of the Khanh-Hoa region of southern-central Vietnam, where malaria is hyper endemic, were selected for study. Parasitemias prior to radical cure ranged from 40 to 19,320/μl in 14 of the individuals, including one mixed infection with P. vivax, and one volunteer was smear positive only for P. vivax, with P. falciparum detected later by PCR. Only two individuals, both with relatively low parasitemias, complained of symptoms consistent with malaria infection, and none had documented fever. A blood sample was taken from each at the commencement of the study (T0), the individuals were radically cured and monitored as described, and another sample was taken when a new parasitemia was detected on weekly blood smears (T1), followed by treatment with mefloquine and a third sample taken 28 days later (T28). Nine of 15 volunteers complained of headache or fever and headache at the time of reinfection, and three were febrile; parasitemias ranged from 40 to 33,840/μl. P. falciparum DNA was extracted from samples T0 and T1 and subjected to PCR amplification with MSP2-specific primers. Details of the subject population and the MSP2 alleles detected for each parasitemic blood sample are provided in Table 1. The subjects ranged in age from 12 to 46 years, with the average age being 25.3 years. The time to reinfection ranged from 37 to 144 days, with an average of 94.5 days (Table 1).

A total of 62 MSP2 genes were identified and sequenced in the 15 pairs of blood samples. Twenty-five MSP2 genes were detected at T0, whereas 37 MSP2 genes were detected at T1. All MSP2 sequences were assigned to either the FC27 or 3D7 allelic family, and no recombinant forms were detected. Of the 62 MSP2 sequences determined, 33 were distinct MSP2 alleles, with 13 belonging to the FC27 family (labelled VN1 to VN13) and 20 belonging to the 3D7 family (labelled VN14 to VN33). Twenty-six infections were caused by parasites expressing FC27 family alleles, and 36 infections were caused by parasites expressing 3D7 family alleles. The pattern of MSP2 infection and reinfection detected in this study was complex and differed from that seen in a previous study in Irian Jaya (7, 15). There was no preponderance of any particular MSP2 genotype of either the FC27 or 3D7 family at either time point (Table 1). The average number of MSP2 alleles detected per subject was 1.8 at T0 and was 2.4 at T1. The most frequently observed alleles were VN1, VN6, VN25, and VN30, being found five, six, four and five times, respectively; however, most sequences were identified at a single time point only.

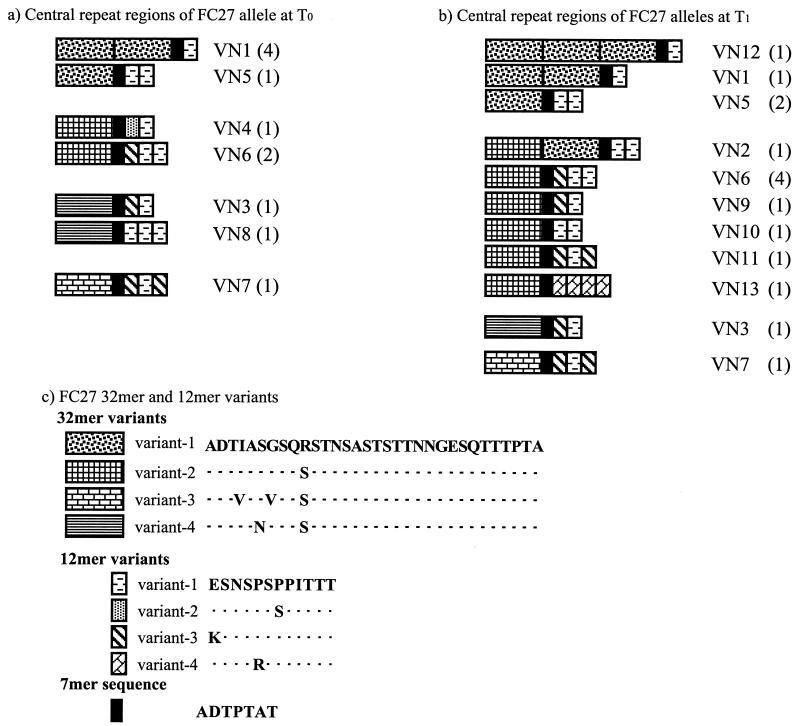

The sequences of the FC27 MSP2 family detected in this study are shown in Fig. 2. Nine of the 13 alleles found are made up of sequences in which a single 32-mer repeat unit is present. In fact, of the 26 infections caused by this group, only 7 were due to alleles with more than one 32-mer. Interestingly, VN5, VN1, and VN12 form an ordered set of 1 to 3 copies of the same 32-mer associated with the same 12-mer. There were four 32-mer variants differing by one to three amino acid substitutions located in the 10 N-terminal residues. The 12-mer pattern of variation is quite complex, with one to three copies of four different variants arranged in many different ways (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the repeat region of FC27 MSP2 alleles at T0 (a) and T1 (b). The allele VN numbers are provided to the right of the representative schematic, and the number of samples at each time point in which each allele was found is shown in parentheses. The alleles are grouped on the basis of their first 32-mer variant sequence. Sequence similarity between repeats is indicated by patterns within boxes (c). The deduced amino acid sequences of the variant-1 32-mer and variant-1 12-mer are provided. Residues of each repeat type that are identical to those of the canonical sequence are indicated by dots.

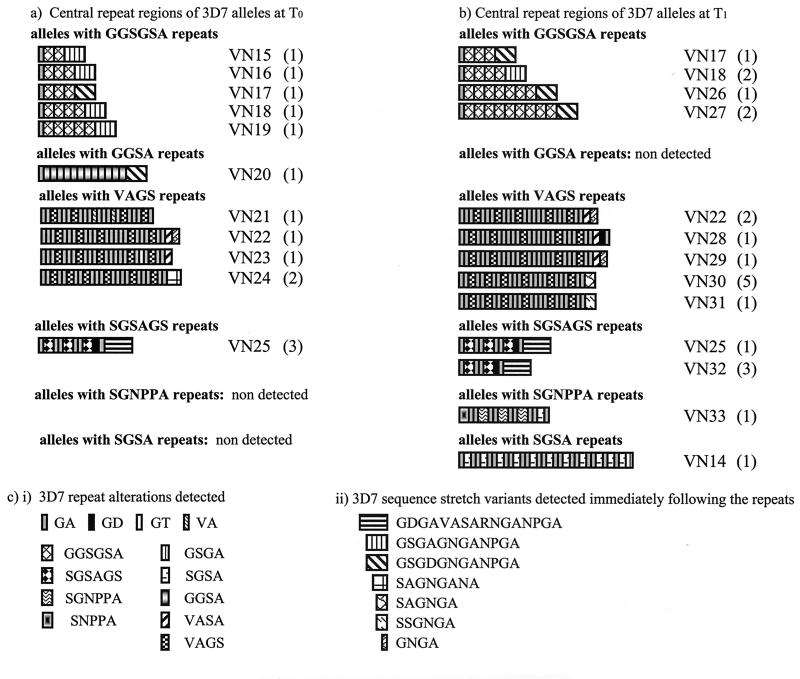

The 3D7 sequences are, if anything, more complex, with six main repeat types associated with a large number of flanking regions (Fig. 3). Each repeat type was organized in a characteristic fashion. In alleles containing GGSGSA and GGSA repeats, these repeat units were arrayed continuously without interruption, whereas 3D7 alleles with other repeat types had one to six tandem GA dimers intervening between successive repeats. 3D7 alleles within each subgroup varied either by repeat copy number, by the number of intervening GA dimers, or by short sequence stretches following the repeats. At both time points, the predominant repeats were GGSGSA and VAGS, with GGSGSA repeats more common at T0 and VAGS repeats more common at T1. The sequence variants located immediately C terminal to the repeats seemed to be partially repeat specific. For example, the 17-mer sequence stretch GDGAVASARNGANPGA was preceded solely by SGSAGS repeats. The two 12-residue sequence stretches GSGAGNGANPGA and GSGDGNGANPGA were found in 3D7 alleles with GGSGSA and GGSA repeats. These two sequences vary by a single replacement of alanine with aspartic acid at the fourth residue (underlined).

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of the central repeat region of 3D7 MSP2 alleles at T0 (a) and T1 (b). The allele VN numbers are provided to the right of the representative schematic, and the number of samples at each time point in which each allele was found is shown in parentheses. The alleles are subgrouped according to the repeat types. Sequence similarity between repeats is indicated by patterns within the boxes. (c) The various 3D7 repeat alterations detected in the study (i), followed by the variant 3D7-specific sequence stretches (ii).

Details of the strains causing reinfection in certain subjects are shown in Table 1. There were two examples of reinfection by identical or near-identical strains at T1. This occurred in subject I, who was infected by VN5 alone at T0 and by five strains at T1, of which one was VN5, and subject J, in whom the T1 strain (VN22) was very similar to the T0 strain (VN23), differing by a single base substitution resulting in an alanine-to-threonine change at the second residue of the central GA dimer. In all other cases, the reinfecting strain differed by multiple mutations, alterations in repeat numbers, or the number of intervening GA dimers.

Anti-MSP2 antibody responses in the infected individuals.

Sera were collected from the 15 individuals at the time of the first infection (T0), the time of the second infection (T1), and 28 days subsequently (T28). The T0 sample from subject C and the T1 sample from subject G were not available for study. Sera were reacted with five recombinant MSP2 proteins to determine reactivity to a number of different regions of the protein (Fig. 1). The proteins included two full-length MSP2 proteins, one representative of the FC27 family (FC27) and one representative of the 3D7 family (FVO). The repeat sequences in these constructs are shown in Fig. 1 and are identical to sequences present in VN1, VN2, VN5, VN12, VN17, VN20, VN26, and VN27, although these MSP2 genes also contain additional sequence elements in their repeat regions. Smaller proteins containing the family-specific nonrepetitive sequences but lacking the central repeats (dFVO and dFC27) and one fusion protein containing the fused amino and carboxyl MSP2 conserved regions were also constructed (Fig. 1). Differences in the pattern of reactivity between the near-full-length constructs and the derivative recombinants can be attributed to antibodies directed exclusively to the repeats.

Table 2 lists the OD405 ELISA values for antibody reactivity to the five recombinant proteins. The number of responders, defined as showing an OD greater than 0.1 at a dilution of 1:5,000, is shown at each time point. Percentages of responders to FC27, FVO, dFC27, dFVO, and conserved recombinant proteins were 79.1, 88.4, 53.5, 86.0, and 7%, respectively (Table 2). IgG-specific subclasses of anti-MSP2 antibodies were determined for positive sera, with the predominant subclass responding to all MSP2 regions being IgG3, followed by IgG1 (data not shown). The levels of IgG2 and IgG4 subclasses responding to all MSP2 regions were extremely low (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

OD405 values for ELISA assays conducted with subject sera to various recombinant MSP2 proteinsa

| Patient | OD405s of sera to recombinant MSP2

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC27

|

FVO

|

dFC27

|

dFVO

|

Conserved

|

|||||||||||

| T0 | T1 | T28 | T0 | T1 | T28 | T0 | T1 | T28 | T0 | T1 | T28 | T0 | T1 | T28 | |

| Negative | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| A | 1.50 | 1.30 | 1.86 | 1.39 | 2.50 | 1.49 | 0.98 | 0.70 | 0.96 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.06 |

| B | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 1.09 | 0.44 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.07 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| C | NA | 0.12 | 0.03 | NA | 0.15 | 0.04 | NA | 0.11 | 0.03 | NA | 0.12 | 0.02 | NA | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| D | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| E | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.09 | 1.76 | 1.33 | 0.13 | 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 1.32 | 1.15 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| F | 0.81 | 1.38 | 0.44 | 0.62 | 2.50 | 1.07 | 0.45 | 0.68 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 2.22 | 0.88 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| G | 0.26 | NA | 0.12 | 1.17 | NA | 0.60 | 0.17 | NA | 0.09 | 1.06 | NA | 0.96 | 0.01 | NA | 0.01 |

| H | 1.44 | 1.04 | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| I | 0.88 | 0.88 | 1.18 | 0.58 | 0.86 | 0.97 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.37 | 0.63 | 0.76 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| J | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| K | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| L | 0.65 | 0.93 | 0.58 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| M | 1.19 | 2.09 | 0.95 | 1.44 | 1.99 | 1.14 | 0.29 | 0.92 | 0.33 | 1.22 | 1.91 | 0.85 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| N | 0.94 | 1.42 | 1.22 | 0.63 | 0.82 | 0.32 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.47 |

| O | 0.54 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.55 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Responders (n) | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

NA, not available. Sera were diluted 1:5,000. Responders were defined as showing an ELISA value greater than that of the background by >0.1.

ELISA values changed with time for many of the subjects, and different patterns of responsiveness were seen. For example, subject E had decreasing ELISA scores for the FVO protein across the three time points. In contrast, subject A showed a marked increase at T1, dropping back to initial values at T28. Replicate determinations were very tightly clustered, varying by less than 0.05. We therefore designated a change in ELISA score of 0.3 as a significant change. For responses to the FC27, FVO, dFC27, and dFVO recombinant proteins, there were 12, 12, 4 and 8 instances of significant changes in ELISA values between successive samples. Thus, a change in ELISA value took place in 32.1% of all possible instances.

The relationship of changes in ELISA value to infecting strains is complicated. In the case of antibodies apparently directed to the repeat regions, subjects A and E were both infected at T0 with a single strain expressing the repeat region found in the FC27 recombinant protein. Neither had a significant change in ELISA value. Yet at T1, when subject E was infected with a strain expressing a 32-mer repeat that differed by three residues, there was a marked decrease in response. In contrast, subject F, who was not infected with an FC27 allele at T0, had a significant increase in ELISA value, which dropped markedly during convalescence to infection with an FC27-like strain (VN1). Subject F was infected at T0 with a strain that bears an FVO-like repeat (GGSA) and responded with a marked elevation in ELISA values both to the full-length protein and to dFVO, showing a boosting of response to both the repeat and nonrepeat regions of MSP2. In contrast, subject A also had a major boost in anti-repeat ELISA values but was infected by a strain that expresses VAGS repeats and had no change in the nonrepetitive family-specific sequences. One puzzling observation was that there were significant changes in ELISA value in subjects without documented infection by that strain family. Examples include subject E at T0 to FVO, subject F at T0 to FC27, and subject L at T1 to FC27.

The two subjects showing evidence of reinfection were subjects I and J. Subject I showed quite high ELISA values for FC27, FVO, and dFVO but not for dFC27. Subject J showed low ELISA values for all five recombinant proteins with a maximum value of 0.15 for the FVO protein. Examination of ELISA values of subjects infected with most strains at T1 (C, I, and O) or infected with the least number of distinct strains (G, K, and L) failed to reveal an obvious relationship between OD values of any of the proteins and the observed infection status. Similarly, there is no relation between antibody response and time to reinfection.

DISCUSSION

This study monitored changes in antibody responses and MSP2 repertoire in individuals living in the Khanh-Hoa region of southern-central Vietnam where malaria is highly endemic. Of the 33 distinct MSP2 alleles, 20 alleles were detected a single time only, suggesting that the genetic diversity of P. falciparum parasites circulating in that area at the time of the study is large. This is similar to results from other areas of endemicity, including Irian Jaya and Papua New Guinea (7, 11, 15). Sequencing studies will provide a higher estimate of MSP2 variability relative to those of studies based on the mobility of the PCR product or on restriction fragment length polymorphisms. For example, VN3, VN4, and VN5 would be indistinguishable in size, as would be VN6, VN7, and VN8. However, distinct differences were noted in this population of strains circulating in Vietnam. These include the high prevalence of FC27 family sequences containing a single 32-mer repeat unit, which compose 73% of the infections in this study compared with 10% in a study in Irian Jaya (7) (P < 0.0001). This could suggest that there are distinct regional pools of circulating strains. Consistent with this is the observation that no sequences in common were found between this study and that in Irian Jaya (7). Thus, from two studies examining infections in a total of 34 subjects, a total of 47 distinct MSP2 sequences have been identified. Finally, the pattern of infections has changed, with a dominant infecting allele of the FC27 family accounting for 90 and 91% of infections in Irian Jaya, compared with 40 and 25% in this study (P < 0.0002).

There was a predominance of 3D7 family alleles detected in this study compared to FC27 family alleles, both in the total number (36 compared to 26) and in the number of distinct sequences (20 compared to 13). Studies from other regions have also observed the predominance of one allelic family over the other. In isolates from the Oksibil area of Irian Jaya and from Colombia, FC27 MSP2 alleles were predominant (7, 15, 30), whereas in Gambian field isolates there was a predominance of 3D7 MSP2 alleles (5).

The complexity of infection varied between 1.8 and 2.4 strains per individual at T0 and T1, respectively. This was greater than observed in Oksibil, Irian Jaya (7), but similar to numbers found in adult residents of Dielmo in Senegal (4). The repertoire of MSP2 alleles in this region is capable of fairly rapid change over time. Only 9 of the 33 sequences were identified at both time points, and VN30, the most abundant allele at T1, was not detected at T0. The exact reasons for this change in repertoire are unknown and may be due to several factors relying on peculiarities of the host, the parasite, the vector, or environmental changes in the region (7).

This study also examined the levels of anti-MSP2 antibodies responding to a number of regions of the protein. Several findings parallel those in previous studies, including a focusing of the antibody response to the nonrepetitive dimorphic family-specific regions and the allele-specific repeats, the predominance of the IgG3 response, and the presence of subjects with very low antibody responses even after many years of exposure to malaria (13, 21, 23, 31, 32, 34).

One possible factor that has been invoked is the action of strain-specific immune responses developed in response to infection. To answer such a question definitively, it would be necessary to assay antibody responses against allele-specific sequences. Such a study would require the construction, purification, and analysis of 37 different proteins for a group of 15 subjects. The development of this large bank of reagents is underway as part of a collaborative effort with other laboratories. As a first approach to such a detailed study, we have used a number of reference proteins which shared repeat sequences with some of alleles found in the subjects. Subjects A, B, C, D, E, F, I, K, and O were infected with parasites containing MSP2 alleles bearing the repeat regions found in the recombinant protein used for antibody estimation. Even with this selected set, it was clear that infection with a particular MSP2 is not invariably associated with boosting of strain-specific responses. There were puzzling changes, such as that in subject F, who had a significant boost to the FC27 32-mer despite the absence of detectable infecting strains of that family. Some unexpected results may have been due to failure to detect infecting parasites, but given the sensitivity of the PCR method, the parasitemia of such strains is likely to be very low. Alternatively, there may have been infections by strains that were not detectable at the time of sampling due to sequestration (9). It is possible to conclude, however, that infection with particular strains does not reliably induce strain-specific antibody. Some subjects showed a decrease in antibody levels, perhaps as a result of absorption by infecting parasites. A clear trend is that antibody to repeat regions is more likely to alter after infection than antibody to nonrepetitive regions, with 24 significant changes occurring in ELISA values to repeats compared to 12 to nonrepeats. The changes between T0 and T1 are fairly evenly distributed between increases and decreases, but between T1 and T28, decreases predominate, perhaps reflective of the short half-life of the IgG3 subclass.

What might be the reasons for why it is hard to discern relationships between infecting strains and resultant antibody responses? We believe this may be partially due to the method of genotyping. The PCR method has the virtue of sensitivity, but it is at the sacrifice of quantitation. There are clear differences in the yield of PCR product, enabling some alleles to be determined by direct sequencing whereas others need to be cloned prior to sequence determination. It seems reasonable to suppose that this reflects the abundance of particular alleles in the subject, but there is no direct evidence that this is so. However, it is likely that subjects may be exposed to some allele-specific sequences at quite small amounts. We believe it would be valuable if sensitive allele-specific detection methods could be developed that give information about strain-specific parasitemias. It seems likely that some modification of the DNA-chip-based methods using specific oligonucleotides based on repeat sequences could be used in this way. The lower limits of sensitivity of such assays are still to be determined however, and we do not know what, if any, level of parasitemia may be below the level of detection of the human immune system.

Two examples of reinfection by strains expressing similar or identical MSP2 proteins occurred. Given the large size of the repertoire, it is probably relatively rare that such an event would occur and it provides little support for the concept of the acquisition of strain-specific immunity. This contrasts with the findings in Irian Jaya (7) and may reflect the different conditions of the studies. In this study, all infections were treated, whereas in Irian Jaya, samples were taken as part of a cross-sectional study and subjects were not treated at the time of sample collection if they were asymptomatic. There is evidence that long-term chemoprophylaxis leads to a diminution of antibody responses to malaria antigens (19), but whether this would occur if infection was already patent is unknown.

This study highlights the extreme complexity of the natural host-parasite relationship. MSP2 is only one of several polymorphic antigens that are the subject of host-protective responses, other proteins of this class being MSP1 and AMA1. A detailed understanding of naturally acquired host-protective immunity will require simultaneous study of each of these antigen systems, together with some of the less polymorphic antigens. A large number of strain-specific reagents as well as improved methods of detection of polymorphic antigen sequences will be required for such studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The field component of this study was conducted as a collaboration between the Institute for Malariology, Parasitology and Entomology (IMPE), Hanoi, Vietnam, and U.S. Naval Medical Research Unit no. 2 (NAMRU-2), Jakarta, Indonesia. We thank Le Dinh Cong, Tran Thi Uyen, Nguyen Dieu Thuong, and Luc Nguyen Tuyen (IMPE) and F. Stephen Wignall and Andrew L. Corwin (NAMRU-2) for assisting with this research. We thank Anne Balloch from the Royal Children Hospital, who kindly supplied the samples of Human Standard Serum. We thank Louis Miller for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the Naval Medical Research and Development Command work units STO F6.1 61110210101.S13.BFX and STO F6.2 622787A.0101.870.EFX.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Yaman F, Genton B, Anders R, Taraika J, Ginny M, Mellor S, Alpers M P. Assessment of role of the humoral response to Plasmodium falciparum MSP2 compared to RESA and SPf66 in protecting Papua New Guinean children from clinical malaria. Parasite Immunol. 1995;17:493–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1995.tb00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anders R F, McColl D J, Coppel R L. Molecular variation in Plasmodium falciparum polymorphic antigens of asexual erythrocytic stages. Acta Trop. 1993;53:239–253. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(93)90032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babiker H A, Ranford-Cartwright L C, Currie D, Charlwood J D, Billingsley P, Teuscher T, Walliker D. Random mating in natural population of malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology. 1994;109:413–421. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000080665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Contamin H, Fandeur T, Rogier C, Bonnefoy S, Konate L, Trape J F, Mercereau-Puijalon O. Different genetic characteristics of Plasmodium falciparum isolates collected during successive clinical malaria episodes in Senegalese children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:632–643. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conway D J, Greenwood B M, McBride J S. Longitudinal study of Plasmodium falciparum polymorphic antigens in a malaria-endemic population. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1122–1127. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1122-1127.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crewther P E, Matthew M L, Flegg R H, Anders R F. Protective immune responses to apical membrane antigen 1 of Plasmodium chabaudi involve recognition of strain-specific epitopes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3310–3317. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3310-3317.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisen D, Billman-Jacobe H, Marshall V F, Fryauff D, Coppel R L. Temporal variation of the merozoite surface protein-2 gene of Plasmodium falciparum. Infect Immun. 1998;66:239–246. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.239-246.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epping R J, Goldstone S D, Ingram L T, Upcroft J A, Ramasamy R, Cooper J A, Bushell G R, Geysen H M. An epitope recognised by inhibitory monoclonal antibodies that react with a 51 kilodalton merozoite surface antigen in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1988;28:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(88)90173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farnert A, Snounou G, Rooth I, Bjorkman A. Daily dynamics of Plasmodium falciparum subpopulations in asymptomatic children in a holoendemic area. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:538–547. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felger I, Marshal V M, Reeder J C, Hunt J A, Mgone C S, Beck H P. Sequence diversity and molecular evolution of the merozoite surface antigen 2 of Plasmodium falciparum. J Mol Evol. 1997;45:154–160. doi: 10.1007/pl00006215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felger I, Tavul L, Kabintik S, Marshall V, Genton B, Alpers M, Beck H P. Plasmodium falciparum: extensive polymorphism in merozoite surface antigen 2 alleles in an area with endemic malaria in Papua New Guinea. Exp Parasitol. 1994;79:106–116. doi: 10.1006/expr.1994.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fenton B, Clark J T, Khan C M, Robinson J V, Walliker D, Ridley R, Scaife J G, McBride J S. Structural and antigenic polymorphism of the 35- to 48-kilodalton merozoite surface antigen (MSA-2) of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:963–974. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.2.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrante A, Rzepczyk C M. Atypical IgG subclass antibody response to Plasmodium falciparum asexual stage antigens. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:145–148. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)89812-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horton R M, Cai Z L, Ho S N, Pease L R. Gene splicing by overlap extension: tailor-made genes using the polymerase chain reaction. BioTechniques. 1990;8:528–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall V M, Anthony R L, Bangs M J, Purnomo, Anders R F, Coppel R L. Allelic variants of the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface antigen 2 (MSA-2) in a geographically restricted area of Irian Jaya. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;63:13–21. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall V M, Coppel R L, Anders R F, Kemp D J. Two novel alleles within subfamilies of the merozoite surface antigen 2 (MSA-2) of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;50:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90255-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall V M, Coppel R L, Martin R K, Oduola A M, Anders R F, Kemp D J. A Plasmodium falciparum MSA-2 gene apparently generated by intragenic recombination between the two allelic families. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;45:349–351. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90104-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mercereau-Puijalon O. Revisiting host/parasite interactions: molecular analysis of parasites collected during longitudinal and cross-sectional surveys in humans. Parasite Immunol. 1996;18:173–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1996.d01-79.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otoo L N, Riley E M, Menon A, Byass P, Greenwood B M. Cellular immune responses to Plasmodium falciparum antigens in children receiving long term anti-malarial chemoprophylaxis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1989;83:778–782. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prescott N, Stowers A W, Cheng Q, Bobogare A, Rzepczyk C M, Saul A. Plasmodium falciparum genetic diversity can be characterised using the polymorphic merozoite surface antigen 2 (MSA-2) gene as a single locus marker. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;63:203–212. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ranford-Cartwright L C, Taylor R R, Asgari-Jirhandeh N, Smith D B, Roberts P E, Robinson V I, Babiker H A, Riley E M, Walliker D, McBride J S. Differential antibody recognition of FC27-like Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein MSP2 antigens which lack 12 amino acid repeats. Parasite Immunol. 1996;18:411–420. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1996.d01-137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Renia L, Ling I T, Marussig M, Miltgen F, Holder A A, Mazier D. Immunization with a recombinant C-terminal fragment of Plasmodium yoelii merozoite surface protein 1 protects mice against homologous but not heterologous P. yoelii sporozoite challenge. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4419–4423. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4419-4423.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rzepczyk C M, Hale K, Woodroffe N, Bobogare A, Csurhes P, Ishii A, Ferrante A. Humoral immune responses of Solomon Islanders to the merozoite surface antigen 2 of Plasmodium falciparum show pronounced skewing towards antibodies of the immunoglobulin G3 subclass. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1098–1100. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.1098-1100.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saul A, Lawrence G, Smillie A, Rzepczyk C M, Reed C, Taylor D, Anderson K, Stowers A, Kemp R, Allworth A, Anders R F, Brown G V, Pye D, Schoofs P, Irving D O, Dyer S L, Woodrow G C, Briggs W R, Reber R, Sturchler D. Human phase I vaccine trials of 3 recombinant asexual stage malaria antigens with Montanide ISA720 adjuvant. Vaccine. 1999;17:3145–3159. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saul A, Lord R, Jones G, Geysen H M, Gale J, Mollard R. Cross-reactivity of antibody against an epitope of the Plasmodium falciparum second merozoite surface antigen. Parasite Immunol. 1989;11:593–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1989.tb00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saul A, Lord R, Jones G L, Spencer L. Protective immunization with invariant peptides of the Plasmodium falciparum antigen MSA2. J Immunol. 1992;148:208–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith D B, Johnson K S. Single-step purification of polypeptides expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with glutathione S-transferase. Gene. 1988;67:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smythe J A, Coppel R L, Day K P, Martin R K, Oduola A M J, Kemp D J, Anders R F. Structural diversity in the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface antigen 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1751–1755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smythe J A, Peterson M G, Coppel R L, Saul A J, Kemp D J, Anders R F. Structural diversity in the 45-kilodalton merozoite surface antigen of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;39:227–234. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90061-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snewin V A, Herrera M, Sanchez G, Scherf A, Langsley G, Herrera S. Polymorphism of the alleles of the merozoite surface antigens MSA1 and MSA2 in Plasmodium falciparum wild isolates from Colombia. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;49:265–275. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90070-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor R R, Allen S J, Greenwood B M, Riley E M. IgG3 antibodies to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 2 (MSP2): increasing prevalence with age and association with clinical immunity to malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:406–413. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor R R, Smith D B, Robinson V J, Mcbride J S, Riley E M. Human antibody response to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 2 is serogroup specific and predominantly of the immunoglobulin G3 subclass. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4382–4388. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4382-4388.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theander T G, Hviid L, Dodoo D, Afari E A, Jensen J B, Rzepczyk C M. Human T-cell recognition of synthetic peptides representing conserved and variant sequences from the merozoite surface protein 2 of Plasmodium falciparum. Immunol Lett. 1997;58:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(96)02685-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas A W, Carr D A, Carter J M, Lyon J A. Sequence comparison of allelic forms of the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface antigen MSA2. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;43:211–220. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90146-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L, Black C G, Marshall V M, Coppel R L. Structural and antigenic properties of merozoite surface protein 4 of Plasmodium falciparum. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2193–2200. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2193-2200.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wooden J, Kyes S, Sibley C H. PCR and strain identification in Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitol Today. 1993;9:303–305. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(93)90131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]