Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) changed healthcare across the world. With this change came an increase in healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and a concerning concurrent proliferation of MDR organisms (MDROs). In this narrative review, we describe the impact of COVID-19 on HAIs and MDROs, describe potential causes of these changes, and discuss future directions to combat the observed rise in rates of HAIs and MDRO infections.

Introduction

According to the US CDC, 1 in 31 hospitalized patients develops at least one healthcare-associated infection (HAI) each day.1 HAIs of particular concern include central-line associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), ventilator-associated pneumonias (VAPs) and surgical site infections (SSIs).2 HAIs cause significant morbidity and mortality for patients, and they also directly impact hospitals’ financial health as pay for performance metrics. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has changed healthcare delivery as a whole, and infection prevention in particular, in a myriad of ways. Early in the pandemic, many hospitals suffered a shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) and had to halt or revise standard infection prevention duties to conserve scarce human and equipment resources and to focus on safely caring for patients with this novel pathogen. However, COVID-19 also ushered in changes that had the potential to reduce HAI rates, including heightened awareness of the risk of pathogen transmission, emphasis on hand hygiene, and universal masking. Later in the pandemic, burnout and staffing instability adversely impacted the ability to deliver consistent, reliable care, reversing a decade of reduction in the rates of HAIs. In this narrative review we will describe the impact of COVID-19 on the frequency of HAIs globally, with a focus on MDR organisms (MDROs). We will outline potential causes of these trends and describe potential future initiatives to reduce the occurrence of MDRO HAIs.

Methods

In collaboration with a library informationist, we queried PubMed for articles describing HAIs during the COVID-19 pandemic. A comprehensive literature review was completed for articles investigating MDROs in relation to COVID-19, which yielded 217 results, all of which were reviewed for inclusion. Please see the Supplementary data at JAC-AMR Online for the full search term. We also reviewed references from included manuscripts to identify other relevant studies.

Results

Global trends

Healthcare-associated infections

HAIs have increased with COVID-19 worldwide.3–12 This change was most notable for CLABSIs, which increased in Europe11,13,14 and the USA in 2020 and 2021,7–10,15–17 with a particularly concerning rise in candidaemia.18–22 In the USA, this rise reversed almost 5 years of reduction in rates of CLABSI.23 The rise in HAIs appeared to be proportional to the number of COVID-19 cases.15,16 Germany, where only 5% of the country was infected with COVID-19 in early 2020, did not see an increase in HAIs during the first months of the pandemic.24 In contrast, countries such as the USA, where an estimated 13% of the population had COVID-19 in early 2020, noted a concurrent rise in HAIs.24 Similarly, a retrospective study of CLABSIs in the USA found that in hospitals where >10% of admitted patients had COVID-19 there were significantly higher rates of CLABSIs compared with hospitals where COVID-19 accounted for <5% of admissions.25 VAPs increased across Europe26–28 and North8,9,17 and Latin America.6 Conversely, in the USA CAUTIs increased only slightly in 2020 and 20211,17 while Clostridioides difficile infections decreased8,17,29 and SSIs remained stable.17

MDROs in HAIs

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic there has been an increase in many MDROs including carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB), antifungal-resistant Candida, ESBL-producing Enterobacterales and VRE.30 Conversely, the overall rates of some infections including carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE), MDR Pseudomonas and MRSA remained stable. However, the rates of most hospital-onset infections increased in both 2020 and 2021.17 The CDC reported a 78% increase in hospital-onset CRAB, 35% increase in hospital-onset CRE, 32% increase in hospital-onset ESBL-producing Enterobacterales, 13% increase in hospital-onset MRSA and a 14% increase in hospital-onset VRE.30 This same trend was reflected around the world: endotracheal aspirates obtained from patients in a Turkish ICU showed an increase in MDROs after March 2020 as compared with the year prior,31 a national referral hospital in Indonesia noted an increase in MDRO bloodstream infections from 130.1 cases per 100 000 patient-days in 2019 to 165.5 cases per 100 000 patient-days in 2020 (incidence rate ratio 1.016 per month, P value <0.001),32 an ICU in Rome saw a statistically significant association between COVID-19 diagnosis and drug-resistant A. baumannii bloodstream infections33 and France noted an increase in resistance to third-generation cephalosporins among Klebsiella, Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections in 2020 compared with 2019.34

MDRO outbreaks

There have been increased reports of outbreaks of HAIs due to MDROs. Although rates of MRSA increased in many locations8 and Gram-positive outbreaks were reported in Europe,35–37 the majority of COVID-19-associated MDRO outbreaks consisted of Gram-negative organisms. MDR Gram-negative outbreaks (of both infections and colonization) were reported in Mexico,38 Spain,39 France,40 the USA41 and Iran.42 The majority of outbreaks occurred in ICUs. Ghanizadeh et al.42 found distinct genetic clusters of Klebsiella pneumoniae in tracheal secretions of 70 patients with COVID-19 infections requiring mechanical ventilation in an Iranian ICU, suggestive of many smaller outbreaks within their ward. In a French ICU dedicated to caring for patients with COVID-19, they noted an outbreak of CTX-M-producing K. pneumoniae, including 16 infections between March and June 2020. This same ICU also noted an increase in rates of CRE compared with pre-pandemic levels.40 Some outbreaks were hospitalwide: during the initial months of the pandemic, a Peruvian hospital experienced an outbreak of NDM-producing K. pneumoniae among COVID-19 patients, a pathogen the hospital had never previously identified.43 Similarly, a New York City medical centre identified five patients with COVID-19 who developed secondary infections including bloodstream infections and VAPs from NDM-producing Enterobacter cloacae between March and April 2020, representing a previously unseen cluster of infections.41

CRAB outbreaks were frequently reported. A cluster of 34 CRAB cases were identified between February and July 2020 at a single acute care hospital in New Jersey during a surge of COVID-19 admissions and resolved after returning to usual infection prevention practices.44 Similar outbreaks and increases in infections were noted in other US,45 Swiss46 and Brazilian ICUs,47–49 including a Brazilian outbreak mostly driven by International Clone 2, an unusual cause of CRAB in Latin America.49 Eckardt et al.45 described a cluster of six CRAB cases (five infections) in their COVID-19-dedicated ICU in Florida in late 2020 where no prior CRAB had been detected. Thoma et al.46 described two CRAB outbreaks in their Swiss medical and surgical ICUs in late 2020, detected in both clinical and screening isolates. Using WGS, they identified the index patients for both outbreaks, both of whom had been transferred from the Balkans. Although transfers from this region were common prior to 2020, CRAB outbreaks were not, suggesting that factors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic directly contributed to the spread of this MDRO. Outbreaks were noted in both non-ICU and ICU patients with COVID-19 in Italy and Israel.33,50 The outbreak described in an Israeli hospital, where CRAB is endemic, occurred despite extensive terminal cleaning measures and was postulated to be due to persistent environmental contamination.50

Multiple reports of Candida auris outbreaks emerged, including in a COVID-19 unit in Florida,51 as well as in Mexico,52 Italy53,54 and Lebanon55 (the first described in this country) and in an ICU in India.56 These outbreaks were identified from both clinical and screening isolates, and they occurred in patients with and without COVID-19, and in both ICUs and hospital wards. A rise in the rate of fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis was noted in Europe.22,57 Outbreaks of this organism were also described in two connected hospitals in Brazil,58 likely resulting from a shared, contaminated CT scanner. Outbreaks were reported in Spain,59 and in Turkey, where the acceleration of an on-going resistant C. parapsilosis outbreak, present since 2015, was confirmed using WGS.60

Factors underlying trends in HAIs and MDROs

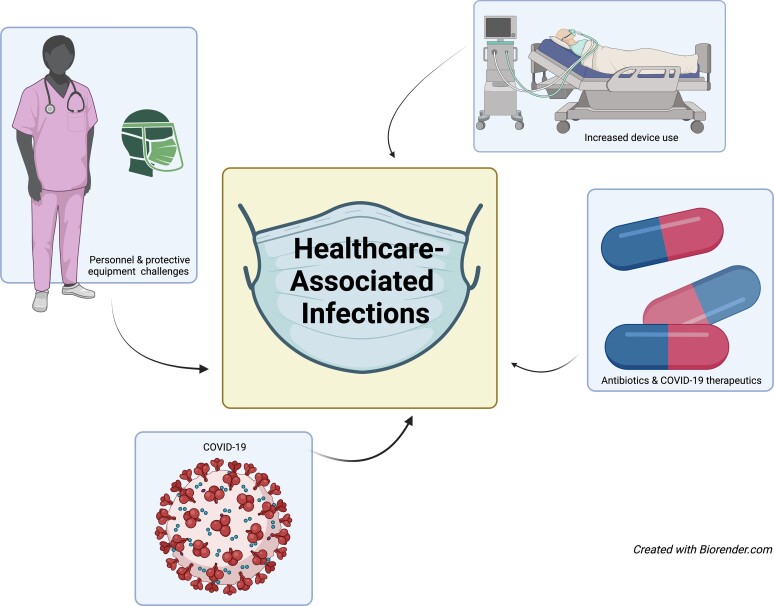

Factors contributing to the rise in HAIs and MDROs are varied but interrelated and include human factors such as staffing instability, delayed care and increased device use. Similarly, COVID-19 infection itself, therapeutics used to treat patients with COVID-19, along with increased and often inappropriate antibiotic use likely also contributed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Factors contributing to HAIs are interconnected. COVID-19 sickened staff and caused burnout, reducing the number available to care for ill patients. Increased critically ill patients altered nurse-to-patient ratios, stretching personnel thinly. Critically ill patients required COVID-19-directed therapeutics that predisposed patients to infections. PPE was meant to protect staff and reduce infections but scarcity led to suboptimal utilization and disease transmission.

COVID-19 as a risk factor

COVID-19 causes intense multisystem inflammation responsible for most of the morbidity and mortality associated with infection. Local immune dysregulation likely contributes to the observed increase in HAIs in those infected with COVID-19. COVID-19 pneumonia is thought to increase the risk of VAPs via associated atelectasis, microemboli, pulmonary infarction and lymphopenia.61 COVID-19 has also been associated with a decrease in pulmonary microbiome diversity, making the lung more susceptible to opportunistic, hospital-acquired pathogens.62 While many centres reported surges in HAIs and MDROs, an Italian surgical, non-COVID ICU noted a decrease in HAIs during the pandemic compared with years prior, with a specific decrease in MDR pathogens, suggesting that the COVID-19 infection itself may be a risk factor for in-hospital acquisition of infection.63

Human factors and equipment as a risk factor

As repetitive waves of COVID-19 infections pummelled communities, ill patients inundated hospitals. This influx of patients led to multiple shortages in equipment and staff and strained the resilience of healthcare personnel (HCP).64 Staff shortages due to burnout or illness led to higher patient-to-nurse ratios, along with increases in the absolute number of patients cared for in a given unit or facility, more frequent staff turnover, and reassigning of staff to unfamiliar units or positions.6,40,46,47,49 HCP described confusion regarding the most up-to-date guidance regarding PPE, lack of interest in infection prevention, increase in workload, and decreased time to care for patients due to staff shortages.15,65 Initially, PPE was scarce and efforts to preserve the limited supply while protecting HCP resulted in decreased patient contact as well as reuse and extended wear of available PPE.39,41,45,59,66 This focus on keeping HCP safe increased the risk of patient-to-patient MDRO transmission due to reuse of gowns and even gloves between patients on the same unit,67 as exemplified by an outbreak of hepatitis E between hospitalized patients in the UK.68 Use of indwelling devices including urinary catheters, central lines and ventilators increased, providing more opportunities for device-related infections.69,70 IV infusion pumps were kept outside of patient rooms to conserve PPE and minimize the number and duration of interactions between patients and HCP.45,71 Interventions proven to reduce HAIs such as adherence to central line and ventilator maintenance bundles were missed due to fewer or shorter interactions between patient and HCP, and competing priorities given the critical illness of these patients.15,41 Patient proning, thought to improve mortality in patients with COVID-19 and acute respiratory distress syndrome, made central line care challenging.72 In the USA, patient length of stay increased in 2020, providing more time for pathogen acquisition.1,73,74 Furthermore, infection prevention teams shifted their focus from reduction of HAIs to helping HCP safely care for patients with COVID-19.41

COVID-19 therapeutics as a risk factor

COVID-19 therapeutics increase the risk of HAIs.41 Dexamethasone was shown early in the pandemic to decrease mortality in patients who required oxygen therapy.75 Unfortunately, dexamethasone also has been shown to lower HLA-DR expression and CD4 cell circulation in COVID-19 patients,76 predisposing them to fungal and bacterial infections.73 Corticosteroid use was associated with increased bloodstream infections and increased the odds of death (OR 8.8, 95% CI 3.5%–22.1%) in an Italian ICU.33 Similarly, in a case series of hospitalized patients in Brazil, the authors noted that all 11 patients who developed candidaemia did so after receiving steroids and that this infection occurred at a rate 10 times higher than patients without COVID-19 during the same time period.77 Patients with COVID-19 who were treated with dexamethasone were more likely to be diagnosed with a VAP in a propensity-matched ICU cohort in Italy (HR 1.81, 95% CI 1.31–2.50)78 and France (adjusted HR of 1.29, 95% CI 1.05–1.58),79 and had an increased risk of MDRO infection in South Korea (adjusted OR 6.09, 95% CI 1.02–36.49).80

Tocilizumab, an anti-IL-6 medication, and baricitinib, a JAK kinase inhibitor, are used in patients with rapidly progressing COVID-19.81,82 Despite the clinical improvement these drugs can provide, they also increase the risk of bacterial infection, including HAIs. Patients with COVID-19 prospectively studied in an Italian ICU diagnosed with an additional coinfection were more likely to have received tocilizumab or baricitinib (OR 5.09, 95% CI 2.2–11.8).83 A similar result was noted in multiple retrospective observational cohorts in the USA.73,84,85 Tocilizumab was associated with an increased risk of Candida bloodstream infections, as described in a case–control study involving two Indian ICUs between August 2020 and January 2021 (adjusted OR 11.952, 95% CI 1.431–99.808).86 These findings are not surprising given both drugs’ effects on the immune system, and their previously described association with infection when used for rheumatological diseases.87–91

Antibiotic use and MDROs

High rates of antibiotic utilization in patients with COVID-19 contributed to an increase in HAIs caused by MDROs. Diagnostic uncertainty, limited evidence-based treatment options, severity of illness and initial concern for bacterial coinfection all drove increased antibiotic use.92 A cross-sectional survey of Scottish hospitals noted that over 60% of patients admitted for COVID-19 received antibiotics on any given day.93 A review of 126 COVID-19 patients requiring mechanical ventilation in three Seattle-area hospitals found that 97% received antibiotics, although only 55% were diagnosed with a VAP and 20% with a bloodstream infection.94 Early reports from China noted the majority of admitted patients received antibiotics,95,96 and a subsequent international meta-analysis found that 72% of patients admitted for COVID-19 globally received antibiotics.97 Furthermore, authors of a retrospective cohort of hospitals in South Carolina noted that when compared with the same months in 2019, hospitals that admitted patients with COVID-19 saw increased antibiotic usage between March and June 2020 (mean difference of 34.9 days of therapy/1000 days, 95% CI 4.3–65.6, P value 0.03). Most of the increased usage was in broad-spectrum antibiotics (defined as antipseudomonal penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems and aminoglycosides) with a 16.4% increase in agents used for hospital-acquired pathogens. Hospitals that did not admit patients with COVID-19 saw no change in their antibiotic utilization during these time periods.98 Increased antibiotic use during COVID-19 has also been described in Portugal,99 the Netherlands,100 elsewhere in the USA41,101–103 and Singapore,104 often with a specific increase in broad-spectrum antibiotics.105 This increase persisted despite a paucity of data regarding antibiotic efficacy106 and multiple studies showing that less than 7% of patients with COVID-19 had a concomitant bacterial infection upon admission.100,107–110

With increased antibiotic use and a shift in infection prevention practices to focus on COVID-19, came an increase in MDROs. A single-centre case–control study conducted in Spain between March and May 2020 found higher rates of CRE in patients admitted for COVID-19 compared with those admitted for other reasons (1.1% versus 0.5%, P value 0.005) with statistically significant higher rates of antibiotic usage (100% of patients with COVID compared with 75% of those without, P value 0.004), specifically increased ceftriaxone and carbapenem use.69 A hospital in Rome noted higher rates of MDROs in COVID-19 units than non-COVID-19 units (29% versus 19%, P value <0.05), which they attributed to broader use of antibiotics in the COVID-19 units.111 In a retrospective cohort of patients admitted for COVID-19 to a single hospital in New York between March and April 2020, they noted that 100% of the patients who developed a superinfection with an MDRO had received antibiotics in the prior 30 days compared with only 65% of those with an infection that was not caused by an MDRO.112 Those with an infection caused by an MDRO received antibiotics for a median of 12 days, compared with a median of 8 days for those with an infection caused by a susceptible organism.112 This hospital also noted a shift in their antibiogram between 2018 and 2020 with a greater than 10% decline in susceptibility of K. pneumoniae isolates to many β-lactams including cefepime, meropenem and piperacillin/tazobactam.112 Although antibiotic prescribing patterns have hopefully improved for patients with COVID-19, the sequelae of antibiotic overuse and increase in MDROs continue to plague the global healthcare system.

Limitations

Although we have presented many studies reporting increased rates of HAIs, MDROs or MDRO outbreaks during the COVID-19 pandemic, some of these reports did not provide pre-pandemic data. The pandemic has likely led to heightened surveillance of MDROs and many of the healthcare systems in these studies may not have had robust tracking systems in place prior to COVID-19, and thus direct comparisons may be limited. The authors of many reports frequently postulate reasons for a rise in HAIs and MDROs, but few studies provide data behind their assertions. Still, the explanations offered are consistent, founded on known epidemiological and biological risk factors, and many authors describe successfully ending outbreaks by intervening in their proposed causal pathways. Furthermore, in the USA the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (the nationally funded and largest healthcare payer in the country) allowed participating facilities to ease their reporting of HAIs, a metric previously required for reimbursable quality evaluations.113 Thus, rates of HAI reporting declined in 2020 and reports from this time may not wholly describe national trends in the USA. This exemption ended in the second quarter of 2020, and reporting rates for 2021 have returned to pre-pandemic levels.17

Future directions

Infection prevention practices and antibiotic prescribing have stabilized since the beginning of the pandemic, with a renewed focus on combatting HAIs and MDROs. Hand hygiene was prioritized with the onset of COVID-19, which will hopefully persist as the pandemic’s urgency subsides.114 Enzymatic detergents and isopropyl alcohol, shown to decrease contamination from COVID-19, are also effective against some Gram-negative bacteria,115 and drug-resistant outbreaks have prompted the development of novel disinfecting agents and protocols to eradicate C. auris as well as other MDROs.116,117 Outbreaks of highly resistant organisms prompted usage of WGS to identify clusters and potential pathways of transmission.54,60 This approach is becoming more commonplace in infection prevention investigations as the availability of WGS increases and associated costs decrease, which may lead to faster, more accurate identification of MDRO outbreaks.118,119 Similarly, the rapid diagnostics employed for COVID-19 are comparable to many rapid diagnostics available to identify bacterial resistance. This similarity may encourage hospital authorities to invest in broader deployment of point-of-care resistance tests in clinical microbiology laboratories.114 COVID-19 has ushered in the acceptance of telehealth and opportunities for remote antibiotic stewardship and infection prevention consults in long-term care facilities and smaller community hospitals that were disproportionately affected by a rise in HAIs during COVID-19.12 There has also been renewed focus on antimicrobial stewardship itself, specifically with regard to patients with COVID-19.30,92 Lastly, novel antibiotics continue to be developed to treat the most drug-resistant bacteria.120

Nevertheless, challenges remain. Hospital staff shortages, which developed during the pandemic due to high turnover, early retirement, burnout and reliance on contract staffing, continue to plague hospitals across the world. The CDC recently recommended that masking requirements could be eased at some healthcare facilities, adding complexity and confusion within many communities.121 Conditions that encourage the appropriate use of PPE and decrease opportunities for infection must be hardwired through quality improvement projects and human factors research to control the rise of HAIs.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has permanently changed healthcare and at least temporarily increased the rates of HAIs and MDRO cases throughout the world. However, with this comes increased recognition of the importance of infection prevention and attention on antimicrobial stewardship. As the world becomes more accustomed to COVID-19, healthcare systems must refocus on preventing HAIs and MDRO infections.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Lucy S Witt, Division of Infection Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Jessica R Howard-Anderson, Division of Infection Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA; Emory Antibiotic Resistance Group, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Jesse T Jacob, Division of Infection Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA; Emory Antibiotic Resistance Group, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Lindsey B Gottlieb, Division of Infection Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA; Emory Antibiotic Resistance Group, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Funding

This manuscript was completed as part of our routine work.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Supplementary data

PubMed search term available as Supplementary data at JAC-AMR Online.

References

- 1. CDC . HAI Data. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/data/index.html.

- 2. CDC . Types of Healthcare-Associated Infections. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/infectiontypes.html.

- 3. Ghali H, Ben Cheikh A, Bhiri S et al. Trends of healthcare-associated infections in a Tuinisian university hospital and impact of COVID-19 pandemic. Inquiry 2021; 58: 469580211067930. 10.1177/00469580211067930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen C, Zhu P, Zhang Y et al. Effect of the ‘normalized epidemic prevention and control requirements’ on hospital-acquired and community-acquired infections in China. BMC Infect Dis 2021; 21: 1178. 10.1186/s12879-021-06886-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bonazzetti C, Morena V, Giacomelli A et al. Unexpectedly high frequency of enterococcal bloodstream infections in coronavirus disease 2019 patients admitted to an Italian ICU: an observational study. Crit Care Med 2021; 49: e31–40. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ochoa-Hein E, González-Lara MF, Chávez-Ríos AR et al. Surge in ventilator-associated pneumonias and bloodstream infections in an academic referral center converted to treat COVID-19 patients. Rev Invest Clin 2021; 73: 210–5. 10.24875/RIC.21000130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patel PR, Weiner-Lastinger LM, Dudeck MA et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on central-line-associated bloodstream infections during the early months of 2020, National Healthcare Safety Network. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022; 43: 790–3. 10.1017/ice.2021.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lastinger LM, Alvarez CR, Kofman A et al. Continued increases in the incidence of healthcare-associated infection (HAI) during the second year of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022; 1–5. 10.1017/ice.2022.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Evans ME, Simbartl LA, Kralovic SM et al. Healthcare-associated infections in veterans affairs acute and long-term healthcare facilities during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022; 1–24. 10.1017/ice.2022.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baker MA, Sands KE, Huang SS et al. The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on healthcare-associated infections. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 74: 1748–54. 10.1093/cid/ciab688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhu NJ, Rawson TM, Mookerjee S et al. Changing patterns of bloodstream infections in the community and acute care across 2 coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic waves: a retrospective analysis using data linkage. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 75: e1082–e91. 10.1093/cid/ciab869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Advani SD, Sickbert-Bennett E, Moehring R et al. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare-associated infections in community hospitals: need for expanding the infectious disease workforce. Clin Infect Dis 2022; ciac684. 10.1093/cid/ciac684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pérez-Granda MJ, Carrillo CS, Rabadán PM et al. Increase in the frequency of catheter-related bloodstream infections during the COVID-19 pandemic: a plea for control. J Hosp Infect 2022; 119: 149–54. 10.1016/j.jhin.2021.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cataldo MA, Tetaj N, Selleri M et al. Incidence of bacterial and fungal bloodstream infections in COVID-19 patients in intensive care: an alarming “collateral effect”. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2020; 23: 290–1. 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. LeRose J, Sandhu A, Polistico J et al. The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) response on central-line–associated bloodstream infections and blood culture contamination rates at a tertiary-care center in the Greater Detroit area. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2021; 42: 997–1000. 10.1017/ice.2020.1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ben-Aderet MA, Madhusudhan MS, Haroun P et al. Characterizing the relationship between coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and central-line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) and assessing the impact of a nursing-focused CLABSI reduction intervention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022; 1–8. 10.1017/ice.2022.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. CDC. 2021 National and State Healthcare-Associated Infections Progress Report. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/data/portal/progress-report.html? ACSTrackingID=USCDC_425-DM93827&ACSTrackingLabel=New%202021%20National%20and%20State%20Healthcare-Associated%20Infections%20Progress%20Report&deliveryName=USCDC_425-DM93827.

- 18. Nucci M, Barreiros G, Guimarães LF et al. Increased incidence of candidemia in a tertiary care hospital with the COVID-19 pandemic. Mycoses 2021; 64: 152–6. 10.1111/myc.13225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Macauley P, Epelbaum O. Epidemiology and mycology of candidaemia in non-oncological medical intensive care unit patients in a tertiary center in the United States: overall analysis and comparison between non-COVID-19 and COVID-19 cases. Mycoses 2021; 64: 634–40. 10.1111/myc.13258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mastrangelo A, Germinario BN, Ferrante M et al. Candidemia in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients: incidence and characteristics in a prospective cohort compared with historical non-COVID-19 controls. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73: e2838–9. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Al-Hatmi AMS, Mohsin J, Al-Huraizi A et al. COVID-19 associated invasive candidiasis. J Infect 2021; 82: e45–6. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ramos-Martínez A, Pintos-Pascual I, Guinea J et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the clinical profile of candidemia and the incidence of fungemia due to fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis. J Fungi (Basel) 2022; 8: 451. 10.3390/jof8050451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. CDC . Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections. 2022. https://arpsp.cdc.gov/profile/nhsn/clabsi.

- 24. Geffers C, Schwab F, Behnke M et al. No increase of device associated infections in German intensive care units during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2022; 11: 67. 10.1186/s13756-022-01108-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fakih MG, Bufalino A, Sturm L et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, central-line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI), and catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI): the urgent need to refocus on hardwiring prevention efforts. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022; 43: 26–31. 10.1017/ice.2021.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maes M, Higginson E, Pereira-Dias J et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Crit Care 2021; 25: 25. 10.1186/s13054-021-03460-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blonz G, Kouatchet A, Chudeau N et al. Epidemiology and microbiology of ventilator-associated pneumonia in COVID-19 patients: a multicenter retrospective study in 188 patients in an un-inundated French region. Crit Care 2021; 25: 72. 10.1186/s13054-021-03493-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rouzé A, Martin-Loeches I, Povoa P et al. Relationship between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the incidence of ventilator-associated lower respiratory tract infections: a European multicenter cohort study. Intensive Care Med 2021; 47: 188–98. 10.1007/s00134-020-06323-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Birlutiu V, Dobritoiu ES, Lupu CD et al. Our experience with 80 cases of SARS-CoV-2-Clostridioides difficile co-infection: an observational study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022; 101: e29823. 10.1097/MD.0000000000029823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. CDC . COVID-19: U.S. Impact on Antimicrobial Resistance. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/covid19-impact-report-508.pdf.

- 31. Bahçe YG, Acer Ö, Özüdoğru O. Evaluation of bacterial agents isolated from endotracheal aspirate cultures of Covid-19 general intensive care patients and their antibiotic resistance profiles compared to pre-pandemic conditions. Microb Pathog 2022; 164: 105409. 10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sinto R, Lie KC, Setiati S et al. Blood culture utilization and epidemiology of antimicrobial-resistant bloodstream infections before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Indonesian national referral hospital. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2022; 11: 73. 10.1186/s13756-022-01114-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Russo A, Gavaruzzi F, Ceccarelli G et al. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections in COVID-19 patients hospitalized in intensive care unit. Infection 2022; 50: 83–92. 10.1007/s15010-021-01643-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Amarsy R, Trystram D, Cambau E et al. Surging bloodstream infections and antimicrobial resistance during the first wave of COVID-19: a study in a large multihospital institution in the Paris region. Int J Infect Dis 2022; 114: 90–6. 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.10.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kampmeier S, Tönnies H, Correa-Martinez CL et al. A nosocomial cluster of vancomycin resistant enterococci among COVID-19 patients in an intensive care unit. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2020; 9: 154. 10.1186/s13756-020-00820-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jalali Y, Sturdik I, Jalali M et al. First report of nosocomial outbreak of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium infection among COVID-19 patients hospitalized in a non-intensive care unit ward in Slovakia. Bratisl Med J 2022; 123: 543–9. 10.4149/BLL_2022_086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Möllers M, von Wahlde M-K, Schuler F et al. Outbreak of MRSA in a gynecology/obstetrics department during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cautionary tale. Microorganisms 2022; 10: 689. 10.3390/microorganisms10040689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fernández-García OA, González-Lara MF, Villanueva-Reza M et al. Outbreak of NDM-1-producing Escherichia coli in a coronavirus disease 2019 intensive care unit in a Mexican tertiary care center. Microbiol Spectr 2022; 10: e0201521. 10.1128/spectrum.02015-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. García-Meniño I, Forcelledo L, Rosete Y et al. Spread of OXA-48-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae among COVID-19-infected patients: the storm after the storm. J Infect Public Health 2021; 14: 50–2. 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Emeraud C, Figueiredo S, Bonnin RA et al. Outbreak of CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST394 in a French intensive care unit dedicated to COVID-19. Pathogens 2021; 10: 1426. 10.3390/pathogens10111426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nori P, Szymczak W, Puius Y et al. Emerging co-pathogens: New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase producing Enterobacterales infections in New York city COVID-19 patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020; 56: 106179. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ghanizadeh A, Najafizade M, Rashki S et al. Genetic diversity, antimicrobial resistance pattern, and biofilm formation in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Biomed Res Int 2021; 2021: 2347872. 10.1155/2021/2347872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Arteaga-Livias K, Pinzas-Acosta K, Perez-Abad L et al. A multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae outbreak in a Peruvian hospital: another threat from the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022; 43: 267–8. 10.1017/ice.2020.1401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Perez S, Innes GK, Walters MS et al. Increase in hospital-acquired carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection and colonization in an acute care hospital during a surge in COVID-19 admissions—New Jersey, February–July 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69: 1827–31. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6948e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Eckardt P, Canavan K, Guran R et al. Containment of a carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii complex outbreak in a COVID-19 intensive care unit. Am J Infect Control 2022; 50: 477–81. 10.1016/j.ajic.2022.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Thoma R, Seneghini M, Seiffert SN et al. The challenge of preventing and containing outbreaks of multidrug-resistant organisms and Candida auris during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: report of a carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii outbreak and a systematic review of the literature. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2022; 11: 12. 10.1186/s13756-022-01052-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shinohara DR, Dos Santos Saalfeld SM, Martinez HV et al. Outbreak of endemic carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-specific intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022; 43: 815–7. 10.1017/ice.2021.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. de Carvalho Hessel Dias V, Tuon F, de Jesus Capelo P et al. Trend analysis of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria and antimicrobial consumption in the post-COVID-19 era: an extra challenge for healthcare institutions. J Hosp Infect 2022; 120: 43–7. 10.1016/j.jhin.2021.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Camargo CH, Yamada AY, Nagamori FO et al. Clonal spread of ArmA- and OXA-23-coproducing Acinetobacter baumannii international clone 2 in Brazil during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Microbiol 2022; 71: 001509. 10.1099/jmm.0.001509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gottesman T, Fedorowsky R, Yerushalmi R et al. An outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a COVID-19 dedicated hospital. Infect Prev Pract 2021; 3: 100113. 10.1016/j.infpip.2021.100113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Prestel C, Anderson E, Forsberg K et al. Candida auris outbreak in a COVID-19 specialty care unit—Florida, July–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70: 56–7. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7002e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Villanueva-Lozano H, de J Treviño-Rangel R, González GM et al. Outbreak of Candida auris infection in a COVID-19 hospital in Mexico. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021; 27: 813–6. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Magnasco L, Mikulska M, Giacobbe DR et al. Spread of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negatives and Candida auris during the COVID-19 pandemic in critically ill patients: one step back in antimicrobial stewardship? Microorganisms 2021; 9: E95. 10.3390/microorganisms9010095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Di Pilato V, Codda G, Ball L et al. Molecular epidemiological investigation of a nosocomial cluster of C. auris: evidence of recent emergence in Italy and ease of transmission during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Fungi (Basel) 2021; 7: 140. 10.3390/jof7020140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Allaw F, Kara Zahreddine N, Ibrahim A et al. First Candida auris outbreak during a COVID-19 pandemic in a tertiary-care center in Lebanon. Pathogens 2021; 10: 157. 10.3390/pathogens10020157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chowdhary A, Tarai B, Singh A et al. Multidrug-resistant Candida auris infections in critically ill coronavirus disease patients, India, April–July 2020. Emerg Infect Dis 2020; 26: 2694–6. 10.3201/eid2611.203504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Routsi C, Meletiadis J, Charitidou E et al. Epidemiology of candidemia and fluconazole resistance in an ICU before and during the COVID-19 pandemic era. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022; 11: 771. 10.3390/antibiotics11060771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thomaz DY, Del Negro GMB, Ribeiro LB et al. A Brazilian inter-hospital candidemia outbreak caused by fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis in the COVID-19 era. J Fungi (Basel) 2022; 8: 100. 10.3390/jof8020100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Puig-Asensio M, Jiménez E, Aguilar M et al. An azole-resistant C. parapsilosis outbreak in a Spanish hospital: an emerging challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2021; 10: 13–4. 10.1186/s13756-021-00974-z33446266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Arastehfar A, Ünal N, Hoşbul T et al. Candidemia among coronavirus disease 2019 patients in Turkey admitted to intensive care units: a retrospective multicenter study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9: ofac078. 10.1093/ofid/ofac078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wicky PH, Niedermann MS, Timsit JF. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in the era of COVID-19 pandemic: how common and what is the impact? Crit Care 2021; 25: 153. 10.1186/s13054-021-03571-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. De Pascale G, De Maio F, Carelli S et al. Staphylococcus aureus ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with COVID-19: clinical features and potential inference with lung dysbiosis. Crit Care 2021; 25: 197. 10.1186/s13054-021-03623-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gaspari R, Spinazzola G, Teofili L et al. Protective effect of SARS-CoV-2 preventive measures against ESKAPE and Escherichia coli infections. Eur J Clin Invest 2021; 51: e13687. 10.1111/eci.13687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fleisher LA, Schreiber M, Cardo D et al. Health care safety during the pandemic and beyond—building a system that ensures resilience. N Engl J Med 2022; 386: 609–11. 10.1056/NEJMp2118285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hoernke K, Djellouli N, Andrews L et al. Frontline healthcare workers’ experiences with personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: a rapid qualitative appraisal. BMJ Open 2021; 11: e046199. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. CDC . Optimizing Supply of PPE and Other Equipment During Shortages. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/general-optimization-strategies.html.

- 67. Miltgen G, Garrigos T, Cholley P et al. Nosocomial cluster of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter cloacae in an intensive care unit dedicated COVID-19. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2021; 10: 151. 10.1186/s13756-021-01022-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lampejo T, Curtis C, Ijaz S et al. Nosocomial transmission of hepatitis E virus and development of chronic infection: the wider impact of COVID-19. J Clin Virol 2022; 148: 105083. 10.1016/j.jcv.2022.105083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pintado V, Ruiz-Garbajosa P, Escudero-Sanchez R et al. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales infections in COVID-19 patients. Infect Dis (Lond) 2022; 54: 36–45. 10.1080/23744235.2021.1963471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. CDC . COVID-19 Impact on HAIs. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/data/portal/covid-impact-hai.html.

- 71. Shah AG, Taduran C, Friedman S et al. Relocating IV pumps for critically ill isolated coronavirus disease 2019 patients from bedside to outside the patient room. Crit Care Explor 2020; 2: e0168. 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Langer T, Brioni M, Guzzardella A et al. Prone position in intubated, mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19: a multi-centric study of more than 1000 patients. Critical Care 2021; 25: 128. 10.1186/s13054-021-03552-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kubin CJ, McConville TH, Dietz D et al. Characterization of bacterial and fungal infections in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 and factors associated with health care-associated infections. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021; 8: ofab201. 10.1093/ofid/ofab201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Weiner-Lastinger LM, Pattabiraman V, Konnor RY et al. The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on healthcare-associated infections in 2020: a summary of data reported to the national healthcare safety network. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022; 43: 12–25. 10.1017/ice.2021.362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 693–704. 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cour M, Simon M, Argaud L et al. Effects of dexamethasone on immune dysfunction and ventilator-associated pneumonia in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome: an observational study. J Intensive Care 2021; 9: 64. 10.1186/s40560-021-00580-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Riche CVW, Cassol R, Pasqualotto AC. Is the frequency of candidemia increasing in COVID-19 patients receiving corticosteroids? J Fungi (Basel) 2020; 6: 286. 10.3390/jof6040286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Scaravilli V, Guzzardella A, Madotto F et al. Impact of dexamethasone on the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients: a propensity-matched cohort study. Crit Care 2022; 26: 176. 10.1186/s13054-022-04049-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lamouche-Wilquin P, Souchard J, Pere M et al. Early steroids and ventilator-associated pneumonia in COVID-19-related ARDS. Crit Care 2022; 26: 233. 10.1186/s13054-022-04097-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Son H-J, Kim T, Lee E et al. Risk factors for isolation of multi-drug resistant organisms in coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia: a multicenter study. Am J Infect Control 2021; 49: 1256–61. 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Food and Drug Administration . Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Drug for Treatment of COVID-19. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-drug-treatment-covid-19.

- 82. Rubin R. Baricitinib is first approved COVID-19 immunomodulatory treatment. J Am Med Assoc 2022; 327: 2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Falcone M, Tiseo G, Giordano C et al. Predictors of hospital-acquired bacterial and fungal superinfections in COVID-19: a prospective observational study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021; 76: 1078–84. 10.1093/jac/dkaa530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kimmig LM, Wu D, Gold M et al. IL-6 inhibition in critically ill COVID-19 patients is associated with increased secondary infections. Front Med 2020; 7: 583897. 10.3389/fmed.2020.583897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kumar G, Adams A, Hererra M et al. Predictors and outcomes of healthcare-associated infections in COVID-19 patients. Int J Infect Dis 2021; 104: 287–92. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Rajni E, Singh A, Tarai B et al. A high frequency of Candida auris blood stream infections in coronavirus disease 2019 patients admitted to intensive care units, Northwestern India: a case control study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021; 8: ofab452. 10.1093/ofid/ofab452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Lang VR, Englbrecht M, Rech J et al. Risk of infections in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tocilizumab. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012; 51: 852–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Winthrop KL, Harigai M, Genovese MC et al. Infections in baricitinib clinical trials for patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2020; 79: 1290–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Giacobbe DR, Battaglini D, Ball L et al. Bloodstream infections in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Eur J Clin Invest 2020; 50: e13319. 10.1111/eci.13319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. FDA . Fact Sheet for Healthcare Providers: Emergency Use Authorization of Baricitinib. https://www.fda.gov/media/143823/download.

- 91. Genentech Inc . Highlights of Prescribing Information—Actemra (Tocilizumab). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/125276s092lbl.pdf.

- 92. Barlam TF, Al Mohajer M, Al-Tawfiq JA et al. SHEA statement on antibiotic stewardship in hospitals during public health emergencies. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022; 43: 1541–52. 10.1017/ice.2022.194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Seaton RA, Gibbons CL, Cooper L et al. Survey of antibiotic and antifungal prescribing in patients with suspected and confirmed COVID-19 in Scottish hospitals. J Infect 2020; 81: 952–60. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.09.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Risa E, Roach D, Budak JZ et al. Characterization of secondary bacterial infections and antibiotic use in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Intensive Care Med 2021; 36: 1167–75. 10.1177/08850666211021745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wang J, Foxman B, Pirani A et al. Application of combined genomic and transfer analyses to identify factors mediating regional spread of antibiotic-resistant bacterial lineages. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71: e642–e9. 10.1093/cid/ciaa364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1708–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Langford BJ, So M, Raybardhan S et al. Bacterial co-infection and secondary infection in patients with COVID-19: a living rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020; 26: 1622–9. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Winders HR, Bailey P, Kohn J et al. Change in antimicrobial use during COVID-19 pandemic in South Carolina hospitals: a multicenter observational cohort study. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2021; 58: 106453. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2021.106453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Castro-Lopes A, Correia S, Leal C et al. Increase of antimicrobial consumption in a tertiary care hospital during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021; 10: 778. 10.3390/antibiotics10070778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Karami Z, Knoop BT, Dofferhoff ASM et al. Few bacterial co-infections but frequent empiric antibiotic use in the early phase of hospitalized patients with COVID-19: results from a multicentre retrospective cohort study in The Netherlands. Infect Dis (Lond) 2021; 53: 102–10. 10.1080/23744235.2020.1839672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Buehrle DJ, Shively NR, Wagener MM et al. Sustained reductions in overall and unnecessary antibiotic prescribing at primary care clinics in a veterans affairs healthcare system following a multifaceted stewardship intervention. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71: e316–22. 10.1093/cid/ciz1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Nestler MJ, Godbout E, Lee K et al. Impact of COVID-19 on pneumonia-focused antibiotic use at an academic medical center. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2021; 42: 915–6. 10.1017/ice.2020.362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Dieringer TD, Furukawa D, Graber CJ et al. Inpatient antibiotic utilization in the veterans’ health administration during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2021; 42: 751–3. 10.1017/ice.2020.1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Liew Y, Lee WHL, Tan L et al. Antimicrobial stewardship programme: a vital resource for hospitals during the global outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020; 56: 106145. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Andrews A, Budd EL, Hendrick A et al. Surveillance of antibacterial usage during the COVID-19 pandemic in England, 2020. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021; 10: 841. 10.3390/antibiotics10070841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Rawson TM, Moore LSP, Zhu N et al. Bacterial and fungal coinfection in individuals with coronavirus: a rapid review to support COVID-19 antimicrobial prescribing. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71: 2459–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Hughes S, Troise O, Donaldson H et al. Bacterial and fungal coinfection among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study in a UK secondary-care setting. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020; 26: 1395–9. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Vaughn VM, Gandhi TN, Petty LA et al. Empiric antibacterial therapy and community-onset bacterial coinfection in patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a multi-hospital cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72: e533–41. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Garcia-Vidal C, Sanjuan G, Moreno-García E et al. Incidence of co-infections and superinfections in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021; 27: 83–8. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Lansbury L, Lim B, Baskaran V et al. Co-infections in people with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 2020; 81: 266–75. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Bentivegna E, Luciani M, Arcari L et al. Reduction of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial infections during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 2. 10.3390/ijerph18031003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Nori P, Cowman K, Chen V et al. Bacterial and fungal coinfections in COVID-19 patients hospitalized during the New York city pandemic surge. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2021; 42: 84–8. 10.1017/ice.2020.368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Department of Health and Human Services . Exceptions and Extensions for Quality Reporting Requirements for Acute Care Hospitals, PPS-exempt Cancer Hospitals, Inpatient Psychiatric Facilities, Skilled Nursing Facilities, Home Health Agencies, Hospices, Inpatient Rehabilitation Facilities, Long-Term Care Hospitals, Ambulatory Surgical Centers, Renal Dialysis Facilities, and MIPS Eligible Clinicians Affected by COVID-19. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/guidance-memo-exceptions-and-extensions-quality-reporting-and-value-based-purchasing-programs.pdf.

- 114. Choudhury S, Medina-Lara A, Smith R. Antimicrobial resistance and the COVID-19 pandemic. Bull World Health Organ 2022; 100: 295–295A. 10.2471/BLT.21.287752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Cureño-Díaz MA, Durán-Manuel EM, Cruz-Cruz C et al. Impact of the modification of a cleaning and disinfection method of mechanical ventilators of COVID-19 patients and ventilator-associated pneumonia: one year of experience. Am J Infect Control 2021; 49: 1474–80. 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Bandara HMHN, Samaranayake LP. Emerging strategies for environmental decontamination of the nosocomial fungal pathogen Candida auris. J Med Microbiol 2022; 71: 1–10. 10.1099/jmm.0.001548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Soffritti I, D’Accolti M, Cason C et al. Introduction of probiotic-based sanitation in the emergency ward of a children’s hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Drug Resist 2022; 15: 1399–410. 10.2147/IDR.S356740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Shelenkov A, Mikhaylova Y, Petrova L et al. Genomic characterization of clinical Acinetobacter baumannii isolates obtained from COVID-19 patients in Russia. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022; 11: 346. 10.3390/antibiotics11030346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Yadav A, Singh A, Wang Y et al. Colonisation and transmission dynamics of Candida auris among chronic respiratory diseases patients hospitalised in a chest hospital, Delhi, India: a comparative analysis of whole genome sequencing and microsatellite typing. J Fungi (Basel) 2021; 7: 81. 10.3390/jof7020081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Cusack R, Garduno A, Elkholy K et al. Novel investigational treatments for ventilator-associated pneumonia and critically ill patients in the intensive care unit. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2022; 31: 173–92. 10.1080/13543784.2022.2030312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. CDC . Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Healthcare Personnel during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.