Abstract

Anti-CD4 antibodies, which cause CD4+ T-cell depletion, have been shown to increase susceptibility to infections in mice. Thus, development of anti-CD4 antibodies for clinical use raises potential concerns about suppression of host defense mechanisms against pathogens and tumors. The anti-human CD4 antibody keliximab, which binds only human and chimpanzee CD4, has been evaluated in host defense models using murine CD4 knockout-human CD4 transgenic (HuCD4/Tg) mice. In these mice, depletion of CD4+ T cells by keliximab was associated with inhibition of anti-Pneumocystis carinii and anti-Candida albicans antibody responses and rendered HuCD4/Tg mice susceptible to P. carinii, a CD4-dependent pathogen, but did not compromise host defense against C. albicans infection. Treatment of HuCD4/Tg mice with corticosteroids impaired host immune responses and decreased survival for both infections. Resistance to experimental B16 melanoma metastases was not affected by treatment with keliximab, in contrast to an increase in tumor colonization caused by anti-T cell Thy1.2 and anti-asialo GM-1 antibodies. These data suggest an immunomodulatory rather than an overt immunosuppressive activity of keliximab. This was further demonstrated by the differential effect of keliximab on type 1 and type 2 cytokine expression in splenocytes stimulated ex vivo. Keliximab caused an initial up-regulation of interleukin-2 (IL-2) and gamma interferon, followed by transient down-regulation of IL-4 and IL-10. Taken together, the effects of keliximab in HuCD4/Tg mice suggest that in addition to depleting circulating CD4+ T lymphocytes, keliximab has the capability of modulating the function of the remaining cells without causing general immunosuppression. Therefore, keliximab therapy may be beneficial in controlling certain autoimmune diseases.

Immunity against different microorganisms involves specialized types of host responses which recognize, control, and eliminate infectious agents. The majority of microbial antigens are endocytosed by antigen-presenting cells (APC), including macrophages, dendritic cells, and B lymphocytes, to be processed and presented to T lymphocytes. T lymphocytes recognize antigens expressed on the surface of target cells in association with either class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules or class II MHC molecules, leading to the stimulation of CD8+ class I MHC-restricted cytotoxic T cells or CD4+ class II MHC-restricted T-helper cells, respectively. Activation of CD4+ T cells is regulated by the CD4 surface molecule by participating in the T-cell receptor (TCR)-MHC II antigen recognition process (6, 9). Activated CD4+ T-helper (Th) cells provide help to B lymphocytes for the production of antibodies against microbial antigens, which is controlled by multiple cytokines that regulate cellular interactions and promote effector cell activities. T-cell responses belong to either the Th1 type, dominated by the production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and associated with cell-mediated immunity, or the Th2 type, distinguished by the production of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and associated with humoral immunity (38). Many other cytokines are involved in the polarization of the immune response; mainly, tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-2, and IL-12 are related to the Th1 type, while IL-5 and IL-10 are linked with the Th2 phenotype. The characterization of the type of immune response provides a basis for understanding how T cells contribute to resistance or susceptibility to different infections.

CD4+ T cells are also involved in the pathogenesis of multiple autoimmune diseases, which occur when tolerance to self antigens breaks down, by fostering and aggravating inflammatory conditions. Thus, antibodies against CD4 that block activation of CD4+ T cells have been evaluated in animal models of autoimmune diseases and shown to inhibit disease onset and/or progression (37, 39, 51). In addition to studies in animal models, anti-human CD4 antibodies have been used experimentally in human clinical trials for the treatment of autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (19, 26, 27, 32). One such antibody is keliximab (IDEC CE9.1/SB-210396), a Primatized chimeric (macaque variable and human constant regions, IgG1 lambda) monoclonal anti-CD4 antibody expressed in CHO cells (1). It is specific for human and chimpanzee CD4 and for CD4 in transgenic mice which express human CD4 (murine CD4 knockout, human CD4 knockin [HuCD4/Tg]) (29). Treatment of HuCD4/Tg mice with keliximab in the epicutaneous sensitization model caused inhibition of contact sensitivity, indicating an effective interaction between human CD4 and keliximab in an in vivo system (41).

Cells expressing human CD4 in HuCD4/Tg mice reside in T-cell regions of all lymphoid organs and also on dendritic and Langerhans cells and macrophages. The distribution of other murine T lymphocytes (CD3+, CD8+) and B lymphocytes (CD45R+) was not affected during the generation of these mice (29). The biologic activity of human CD4 in HuCD4/Tg mice has been characterized in terms of immune function and host defense. Peripheral CD4+ T cells in HuCD4/Tg mice have a similar memory-to-naïve ratio to that of BALB/c CD4+ T cells, indicating normal in vivo T-cell maturation. Furthermore, TCR-CD4-mediated signaling in HuCD4/Tg and BALB/c CD4+ T cells is similar, demonstrating that the appropriate murine tyrosine kinase signaling molecules can associate with the human CD4 transgene product (our unpublished results). HuCD4/Tg mice manifest normal T-cell-dependent humoral and cellular immune responses, including a healthy host defense against Candida albicans and Pneumocystis carinii infections. HuCD4/Tg mice have survived for 18 to 24 months in our facilities with no unexpected pathologic developments. Taken together, results from in vivo and in vitro assessments indicate that insertion of the human CD4 transgene into murine T cells following the disruption of murine CD4 restores overall immune competency and CD4-dependent interactions in these mice. Therefore, HuCD4/Tg mice provided a suitable model for preclinical safety evaluation of anti-human CD4 monoclonal antibodies (MAbs).

Because of concerns about possible consequences of chronic abrogation of CD4+ T-cell function or antibody-mediated depletion of CD4+ T cells, including susceptibility to opportunistic infections, the potential for keliximab to interfere with host defense mechanisms was addressed in this work using the following three different models: chronic infection with P. carinii, acute infection with C. albicans, and B16 melanoma experimental metastasis in HuCD4/Tg mice. These models have been chosen based on previous reports showing that depletion of CD4+ T cells with anti-CD4 MAbs compromised control of P. carinii (20) and C. albicans (45) infections and abrogated IFN-γ-induced control of melanoma metastases (36) in mice. To focus on a role of keliximab in immune response modulation, the kinetics of induction of Th1 and Th2 cytokines by splenocytes from keliximab-treated HuCD4/Tg mice were characterized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Male and female HuCD4/Tg mice (provided by Killeen [29] and bred at Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass.) were approximately 4 to 6 months of age. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and reviewed by the SmithKline Beecham animal care and use committee.

P. carinii infection model.

For a chronic model of infection with P. carinii, female HuCD4/Tg mice (10 per group) were cohoused with P. carinii-infected CB-17 SCID mice. Beginning on day 1, each group of mice was housed in a large rodent cage together with two female P. carinii-infected CB-17 SCID mice (Trudeau Institute Breeding Facility) for the duration of the study. The SCID mice used came from heavily infected stock and typically contained 107 to 108 P. carinii cells in their lungs. If either of the SCID mice died during the course of the study they were replaced with infected SCID mice from the same stock. HuCD4/Tg mice exposed to P. carinii-infected SCID mice were treated for 6 weeks. At the termination of treatment, blood from the vena cava was collected into either heparinized tubes for lymphocyte subset analysis by flow cytometry or tubes without anticoagulant for serum separation. The lungs were removed and homogenized for quantification of P. carinii organisms. The number of P. carinii nuclei in lungs was determined microscopically on cytospin-prepared slides of lung homogenates stained with Diff-Quik as described previously (20). Briefly, P. carinii nuclei were counted in 50 microscopic fields or until a count of 150 P. carinii nuclei was reached, and the count was converted to total P. carinii nuclei per lung. The values are reported as log10 units. The value 4.06 (log10) represents the minimal detectable number of P. carinii in 50 counted fields. Antibody responses to P. carinii antigens in mouse sera were determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Crude antigen was prepared from P. carinii isolated from the lungs of infected SCID mice as described previously (20).

C. albicans infection model.

For the C. albicans infection model, male and female HuCD4/Tg mice were infected with C. albicans intravenously (i.v.) into a tail vein to assess survival, intramuscularly (i.m.) into a calf muscle to evaluate clearance of local infection, or subcutaneously (s.c.) into the flank to assess the humoral response. C. albicans strain B311 (serotype A: ATCC 32354) was used as described previously (36). Briefly, organisms grown as a suspension in Sabouraud dextrose broth (22 h at 26 ± 1°C) were aliquoted and frozen at −70°C. For injection, the yeast cells were grown overnight, washed, and quantified by hemacytometer in the presence of 0.02% methylene blue. The cell suspension was adjusted to achieve approximately 1 × 106 to 2 × 106 viable C. albicans cells per inoculation. The number of viable yeast cells in the inoculum was verified by quantifying the number of CFU on yeast extract-protease-dextrose agar plates incubated overnight at 37°C. Typically, 10 mice per group were infected with C. albicans by i.v. injections and observed daily until day 15 for the survival model. Mice that were moribund were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. These mice were counted as if they had died the next day. Percent survival and median time survival for each group were calculated. For the localized infection model, mice (six per group) received i.m. injections into calf muscles and were sacrificed 6 days later. The calf muscles were removed to determine the number of C. albicans CFU by quantitative culture, as described previously (24). Briefly, the muscle tissues from each animal were homogenized, diluted with buffered saline, and plated onto 24-well tissue culture plates containing yeast extract-protease-dextrose agar. The plates were shaken to mix the C. albicans suspensions with agar, allowed to solidify, and then incubated at 37°C overnight. CFU for each tissue sample were counted under a dissecting microscope in quadruplicates. For the humoral immunity model, mice (six per group) received four weekly s.c. injections of live C. albicans and were sacrificed 1 week after the last immunization. Serum samples were tested for anti-C. albicans immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies by ELISA, as described previously (24). Briefly, 1.5 × 105 C. albicans cells per well were grown on 96-well round-bottomed plates. Culturing C. albicans in this manner induces germ tube formation and adherence to the well (15). Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and stored at 4°C overnight. C. albicans-coated plates received samples of serially diluted mouse serum, followed by goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase and enzyme substrate. A chromogenic reaction was stopped by adding 6 M NaOH, and samples were transferred into new 96-well flat-bottomed plates to read the optical densities (ODs).

B16 melanoma metastasis model.

For the melanoma metastasis model, male HuCD4/Tg mice received i.v. injections of B16 melanoma cells into the tail vein. The murine B16 melanoma cell line used in these experiments was derived from B16F10 cells (12) obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). To ensure metastatic vigor, a lung colony that grew out from a HuCD4/Tg mouse injected with B16F10 cells was used to create a new primary culture. This primary culture was expanded in vitro, and a new line (B16F11) was established and banked. Tumor cells from subconfluent cultures in the exponential-growth phase were harvested with 0.04% trypsin–0.5 mM EDTA and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline. Typically, 10 mice received 0.5 × 106 to 1 × 106 melanoma cells per inoculation and were sacrificed 21 days later. The tracheas with attached lungs were removed and fixed in neutral buffered formalin. Tumor foci were counted using a dissecting microscope.

Study design for drug treatments.

For the different models studied, HuCD4/Tg mice were dosed with different drug regimens, in a range of 5 to 250 mg/kg of body weight, based on a rationale for the model application and feasibility of dosing in the short-and long-term evaluations. Agents known to have impact on host resistance were included as positive controls.

For the P. carinii infection model, HuCD4/Tg mice received weekly i.v. doses of 0, 25, or 250 mg of keliximab/kg/day (SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, King of Prussia, Pa.) or twice a week s.c. doses of 80 mg of cortisone acetate/kg/day (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) for 6 weeks.

For the C. albicans survival and local infection models, HuCD4/Tg mice received three daily intraperitoneal (i.p.) doses of keliximab at 0, 1, or 100 mg/kg/day or five daily i.p. doses of dexamethasone (Sigma) at 50 mg/kg/day prior to i.v. or i.m. challenge, respectively, with C. albican. For the C. albicans immunization model, the initial three or five doses of keliximab or dexamethasone, respectively, were followed by a once-a-week dose of keliximab or three daily doses of dexamethasone per week prior to subsequent weekly boosts with C. albicans.

For the B16 melanoma metastasis model, HuCD4/Tg mice received four weekly i.v. doses of keliximab at 0, 25, or 250 mg/kg/day starting 1 day prior to challenge with B16 tumor cells. In addition, mice were treated with a single i.v. dose of Thy1.2 antibody (clone 30H12; ATCC, Rockville, Md.) at 0.5 mg/mouse or two i.p. doses (on day −1 and day 2) of rabbit AAGM-1 (Wako BioProducts, Richmond, Va.) serum at a 1/10 dilution, starting 1 day prior to challenge with B16 cells.

Lymphocyte subset analysis.

Peripheral blood samples from HuCD4/Tg mice were analyzed for cell subset phenotypes. Three-color flow cytometry analysis was performed using the following fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies: anti-murine CD3-phycoerythrin (PE) (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.), anti-human CD4 (OKT4-fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]; Ortho-Mune Monoclonal Antibody, Raritan, N.J.), anti-murine CD8-biotin (clone 53-6.7), and Streptavidin-Cy-Chrome (Pharmingen). For characterization of the coating of cell surface CD4 by keliximab, cells were stained with a panel of antibodies containing OKT4A (Leu3a; Ortho-Mune) (CD3-CyC–OKT4-PE–OKT4A-FITC), which binds to the same epitope as keliximab. The percentage of T-cell coating was derived from the absolute cell counts (OKT4 and OKT4A) using the following equation:

|

For the melanoma studies, an additional two antibody panels were used to monitor natural killer (NK) cells as follows: DX5 (anti-murine pan-NK)-PE (Pharmingen), CD2-FITC (Pharmingen), and CD3-CyC (Pharmingen) comprised panel 1, and CD2-PE, OKT4-FITC, and CD8-TC (all from Pharmingen) comprised panel 2. Prior to staining, 10 μl of diluted mouse serum was added to the aliquot of blood to block nonspecific binding of antibodies to Fc receptors. After staining, red blood cells were lysed and washed, and samples were fixed. The stained cells were stored at 4°C until analyzed within 24 h on the FACScalibur cytofluorometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.). Analysis of the lymphocyte population was accomplished by establishing forward and side scatter settings to exclude other cell populations. Lymphocyte phenotypes were analyzed using CellQuest software.

Cytokine induction in unchallenged HuCD4/Tg mice.

Two groups of HuCD4/Tg mice received a single i.v. dose of 5 or 100 mg of keliximab/kg on day 1 and were sacrificed on days 2, 9, and 29 or on days 3, 7, and 14, respectively, to obtain spleen tissues. Cytokine gene transcription and protein synthesis in splenocytes were induced with an anti-CD3 MAb (Pharmingen). Splenocytes were plated in 24-well dishes at 5 × 106 cells/well and stimulated with soluble anti-CD3 MAb (1 μg/ml) overnight in 5% CO2 at 37°C. For cytokine protein secretion, supernatants were collected at 24 (IL-2) or 48 h (IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-10) and stored at −20°C until tested by ELISA kits (Biosource International, Palo Alto, Calif.).

Cytokine gene expression was assessed using fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based real-time reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR (TaqMan) (18, 23). Total RNA was extracted from stimulated splenocytes using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio) and quantitated using RiboGreen (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.), and the integrity was confirmed on formaldehyde agarose gels. One microgram of total RNA was treated with 1 U of RQ1 DNase (Promega, Madison, Wis.) in 1× TaqMan RT buffer (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) for 15 min at 37°C followed by heat inactivation of the RQ1 DNase at 75°C for 5 min. RNA was converted to cDNA with 125 U of MultiScribe RT (PE Applied Biosystems), 2.5 μM random hexamers, 40 U of RNasin, 500 μM concentrations (each) of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP), and 5.5 mM MgCl2 in 100 μl of 1× TaqMan RT buffer and was incubated at 25°C for 10 min followed by 48°C for 30 min and 95°C for 5 min. A cDNA sample equivalent to 10 ng of total RNA (1 μl of the cDNA reaction) was used per reaction in FRET-based real-time RT-PCR. Each amplification reaction contained 1× TaqMan Universal master mix (1.25 U of AmpliTaq Gold; 200 μM concentrations each of dATP, dCTP, and dGTP; 400 μM dUTP; 3.5 mM MgCl2; 0.5 U of AmpErase UNG; ROX passive reference; and optimized buffer) (PE Applied Biosystems), 200 nM concentrations each of forward and reverse primers, and 100 nM oligonucleotide probe (sequences are listed in Table 1) in a 50-μl final volume. Each reaction also contained 20 and 100 nM 18S rRNA specific primers and oligonucleotide probe, respectively, as an endogenous reference. The 18S rRNA probe was labeled with a different reporter dye, 5′-VIC (λmax = 550 nm), and the 3′-TAMRA quencher dye. The charge-coupled device camera could then distinguish contributions from VIC and 6-FAM signals in the multiplexed reaction where both the target gene and the endogenous reference gene were amplified in the same reaction well. Each reaction was done in duplicate. Two-step PCR was performed on the ABI 7700 (PE Applied Biosystems) thermal cycler for 40 cycles (denature at 95°C for 15 s and anneal and extend at 58°C for 60 s), with an initial 2-min, 50°C step for optimal AmpErase UNG activity and a 95°C, 10-min step to activate AmpliTaq Gold and inactivate AmpErase UNG. For quantitation of mRNA, a threshold of the change in fluorescence intensity (ΔRn) was set at least 10 standard deviations above the mean of the background fluorescence. The cycle at which ΔRn crosses the threshold is referred to as the threshold cycle (Ct), and the Ct value is dependent on the starting copy number of the template. Relative changes in mRNA expression levels between control and treated groups can be determined by calculating the differences in Ct values. For FRET-based RT-PCR, a Ct value was reported for both FAM (cytokine) and VIC (endogenous reference, 18S rRNA), which were simultaneously amplified in each well. The cytokine expression levels were normalized against the endogenous reference for each well by subtracting the Ct of the endogenous reference from the respective cytokine gene Ct. Because there is an inverse exponential correlation between Ct and template starting copy number (as the Ct value decreases by one, the calculated starting copy number of the template doubles), expression levels can be calculated by the conversion factor of 2−ΔCt.

TABLE 1.

Cytokine primers and probes (P) used for FRET-based RT-PCR

| Primer or probe | Sequence |

|---|---|

| IL-2-5′ | 5′CTGGAGCAGCTGTTGATGGA |

| IL-2-3′ | 5′CTTTCAATTCTGTGGCCTGCTT |

| IL-2-P | 6FAM-TGAAACTCCCCAGGATCTCACCTTC-TAMRA |

| IFN-γ-5′ | 5′AAGTGGCATAGATGTGGAAGAAAAG |

| IFN-γ-3′ | 5′TGCAGGATTTTCATGTCACCAT |

| IFN-γ-P | 6FAM-CTTTTGCCAGTTCCTCCAGATATCCAAGAAGA-TAMRA |

| IL-10-5′ | 5′CATTTGAATTCCCTGGGTGAGA |

| IL-10-3′ | 5′GCTCCACTGCCTTGCTCTTATT |

| IL-10-P | 6FAM-CGCTGTCATCGATTTCTCCCCTGTG-TAMRA |

| IL-4-5′ | 5′AGAGAGATCATCGGCATTTTGAA |

| IL-4-3′ | 5′TTCGTTGCTGTGAGGACGTTT |

| IL-4-P | 6FAM-CACAGGAGAAGGGACGCATGCAC-TAMRA |

| 18S rRNA-5′ | 5′CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA |

| 18S rRNA-5′ | 5′TCCTGTATTGTTATTTTTCGTCACTACCT |

| 18S rRNA-P | VIC-CGCGCAAATTACCCACTCCCGA-TAMRA |

Function of purified CD4+ T cells in HuCD4/Tg mice. (i) CD4+ T-cell enrichment.

Spleens from HuCD4/Tg mice were dispersed into single-cell suspensions in ice-cold Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with penicillin (50 U/ml), streptomycin (50 μg/ml), l-glutamine (2 mM), HEPES (10 mM), β-mercaptoethanol (50 μM), sodium pyruvate (1 mM), and 10% fetal calf serum (DMEM-10) and were passed through a 100-μm-pore-size nylon mesh strainer. Non-CD4+ cells were depleted by coating cells with anti-CD8 (3.155; ATCC), anti-CD24 (J11d; ATCC), and anti-H-2d (MK-D6; ATCC) antibodies and treating them with rabbit H-2 complement (1:10; Pel-Freez, Brown Deer, Wis.) at 37°C for 60 min. Viable CD4+ T cells were collected at the interface of a Lympholyte M cushion (Cedarlane Laboratories, Hornby, Ontario, Canada) and resuspended at 106/ml in DMEM-10.

(ii) Preparation of T-cell-depleted APC.

Spleens from CBA/J mice were teased into single-cell suspensions in ice-cold DMEM-10 and passed through 100-μm-pore-size nylon mesh filters. Red blood cells were lysed by resuspension in 5 ml of ice-cold Gey's hemolytic buffer per spleen for 5 min. T cells were depleted by coating with anti-Thy1.2 antibody (30H12; ATCC) and treating with rabbit H-2 complement (1:10) at 37°C for 60 min. T-cell-depleted splenocytes were washed and resuspended at 107/ml in DMEM-10.

(iii) Proliferation to alloantigen.

CD4+ T cells (5 × 104) enriched from spleens of HuCD4/Tg mice were stimulated with T-cell-depleted splenocytes (5 × 105) from CBA/J mice in round-bottomed 96-well plates in a final volume of 200 μl of DMEM-10 and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C for 72 h in triplicate. Cultures were pulsed with [3H]thymidine (1 μCi/well) for the last 8 h.

Statistical analysis.

Survival data, expressed as group medians, were analyzed using the nonparametric Wilcoxon test. The other parameters were statistically analyzed for group differences using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test, one-way analysis of variance with all pairwise multiple comparison procedures (Tukey's Test), or the Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance test. The paired t test was used to make comparisons between vehicle- and drug-treated groups when applicable. Values of P that were <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Kinetics of CD4+ T-cell depletion and recovery in HuCD4/Tg mice treated with keliximab.

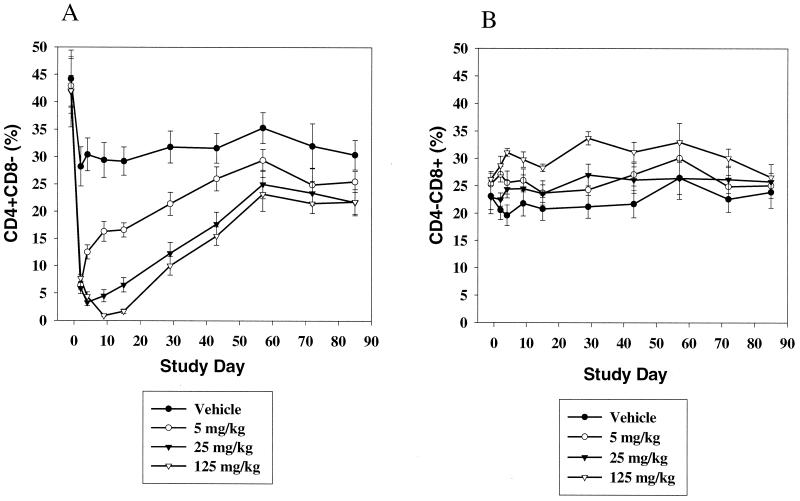

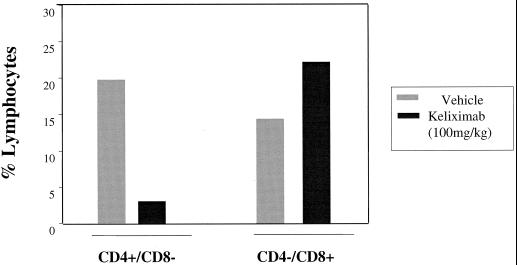

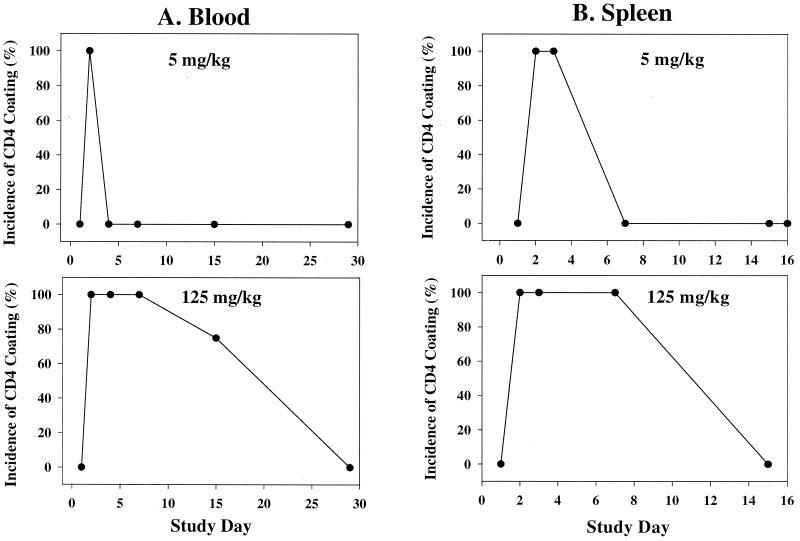

Analysis of lymphocyte subsets in peripheral blood over an extended time course (about 3 months) in HuCD4/Tg mice following a single injection of keliximab showed the kinetics of CD4+ T-cell loss and recovery (Fig. 1A). Keliximab administered at 5 mg/kg caused a reduction in % CD4+ T cells on day 2 postdosing (70%) and a recovery to concurrent control levels by day 43. Peak reduction in CD4+ T cells in response to a 25- or 125-mg/kg dose of keliximab was observed on day 4 (89%) or 9 (97%), respectively, and complete recovery to baseline did not occur by day 85 posttreatment. Interestingly, the reduction in percent CD4+ cells was not accompanied by the expected proportional increase in percent CD8+ lymphocytes (Fig. 1B). This observation was confirmed by converting percentages to absolute counts of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes, in which CD4+ T cells were depleted and CD8+ T cells were not affected (data not shown). Overall, keliximab caused CD4+ T-cell reduction in a dose- and time-dependent manner. While the effects of 5- and 25-mg/kg doses on CD4+ T cells were very distinct in their kinetic profiles, the effects of 25- and 125-mg/kg doses of keliximab did not differ dramatically. A group of HuCD4/Tg mice treated with keliximab (5 or 100 mg/kg i.v. or 5 mg/mouse i.p.) was also evaluated for lymphocyte subsets in the spleen. A dose of 100 mg of keliximab per kg caused a 75% reduction in spleen CD4+ T cells on day 7 postdosing (Fig. 2), which is similar to the degree of CD4+ T-cell reduction in peripheral blood in response to 125 mg of keliximab per kg at the comparable time point (Fig. 1). Keliximab administration was also associated with coating of cell surface CD4 in both blood and spleen tissues. As shown in Fig. 3, the coating of the CD4 was evident in all animals receiving active treatment, and the duration of saturated (100%) coating increased with the increase in dose of keliximab. The coating persisted for at least 2 and 7 days in all animals following a single dose of 5 and 125 mg/kg, respectively. These data indicate that the effects of keliximab on CD4+ lymphocytes in blood and spleen compartments are comparable.

FIG. 1.

Effect of keliximab (5, 25, and 125 mg/kg) on peripheral blood CD4+ (A) and CD8+ (B) T cells. HuCD4/Tg mice (five per group) received a single i.v. injection of keliximab on day 1, and blood samples were analyzed by flow cytometry at the indicated time point. Data represent means ± standard errors of the means for each group.

FIG. 2.

Effect of keliximab (100 mg/kg) on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in spleen tissue. HuCD4/Tg mice (three per group) received a single i.v. injection of keliximab on day 1, and splenocyte samples were collected on day 7. Pooled samples from control and keliximab groups were analyzed by flow cytometry.

FIG. 3.

Incidence and time course of CD4 occupancy on the surface of CD4+ T cells (coating) by keliximab in blood (A) and spleen tissue (B). Coating of CD4, determined by the absence of OKT4A staining of lymphocytes, was present in 100% of HuCD4/Tg mice (five per group) on days 2 to 3 and 2 to 7 postdosing with 5- and 125-mg/kg doses, respectively. Spleen data for the high dose represent mice that received keliximab at 5 mg/mouse (approximately 150 mg/kg) i.p.

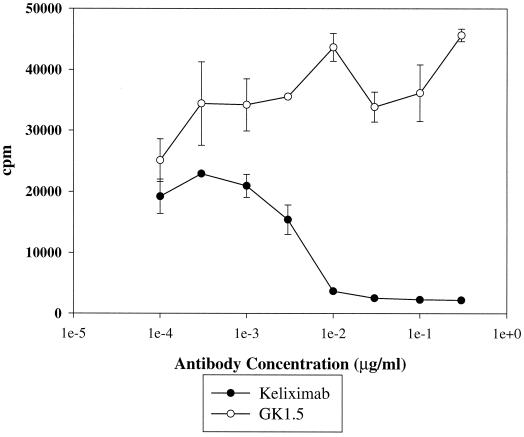

Inhibition of activation of HuCD4/Tg CD4+ T cells by keliximab.

To demonstrate a specific activity for keliximab, its effects on purified CD4+ T cells from spleens of HuCD4/Tg mice were evaluated in a mixed lymphocyte reaction. As demonstrated in Fig. 4, keliximab, but not a control anti-murine CD4 antibody (GK1.5), inhibited proliferation of HuCD4/Tg CD4+ T cells stimulated with APC from allogenic mice with 50% inhibitory concentrations of 5 ng/ml. In this system keliximab bound only human CD4 expressed on HuCD4/Tg T cells and did not recognize any antigen on the T-cell-depleted splenocytes from CBA/J mice. These results show not only specificity but also a great efficiency in blocking T-cell activation by keliximab in vitro. Since in vivo exposure to keliximab in HuCD4/Tg mice has been well characterized and the high plasma concentration has been demonstrated (10 μg/ml to 100 ng/ml for at least 4 days after a single dose of 5 mg/kg) (48), it is expected that keliximab would also be very efficient in blocking T-cell activation in vivo.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of proliferation of HuCD4/Tg CD4+ T cells in response to alloantigen by keliximab. CD4+ T cells were purified from spleens of HuCD4/Tg mice and cultured with T-cell-depleted splenocytes of CBA/J mice in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations of keliximab or a control anti-murine CD4 antibody, GK1.5. Proliferation was determined by incorporation of [3H]thymidine. Means ± standard deviations (SDs) for each antibody concentration are presented. Data are representative of three experiments.

Based on these data, doses of 5, 25, and 250 mg/kg in an intermittent (once a week) dosing regimen, which mimicked the dosing schedules planned for the clinical studies (54), were used in HuCD4/Tg mice to address the impact of the treatment with keliximab on host defense. Due to anaphylactic reactions observed in a high percentage of mice receiving weekly doses of keliximab at 5 mg/kg but not at ≥25 mg/kg, repeated doses of 5 mg/kg could not be evaluated in such studies.

Effect of keliximab on P. carinii infection.

As shown in Table 2, after cohousing for 43 days with P. carinii-infected SCID mice, HuCD4/Tg mice treated with keliximab at 25 or 250 mg/kg/day and HuCD4/Tg mice treated with cortisone acetate had a more than 100-fold increase in the numbers of P. carinii in their lungs (106.39 to 106.95) compared to the vehicle control group, in which the P. carinii count was at the limit of detection (104.06). Keliximab- or cortisone acetate-treated mice also had significantly lower OD values for P. carinii-specific IgG in serum than did controls, indicating a suppression of the humoral response. Despite similar effects of keliximab and cortisone acetate in terms of an increase of P. carinii burden in the lung and a decrease in specific antibody production, there was an important difference between mice treated with these two compounds. Cortisone-treated mice developed P. carinii pneumonia (PCP), and 60% of them died during the sixth week of the study, while none of the keliximab-treated mice had signs of PCP, and there was no mortality in mice treated with keliximab at doses as high as 250 mg/kg. All mice that received keliximab or cortisone acetate had significantly lower (P < 0.05) percentages of CD4+ T lymphocytes (2 to 4% of total lymphocytes) than did the control group (15% of total lymphocytes). Although not statistically significant, there was a noticeable dose-dependent decrease in the mean percentages of CD3+ CD4+ cells between the 25-mg/kg (3.11 ± 1.85%) and 250-mg/kg (1.62 ± 0.93%) doses of keliximab. Thus, in this CD4+ cell-dependent infection, a severe and sustained depletion of CD4+ T cells induced by six weekly doses of keliximab increased susceptibility to P. carinii in HuCD4/Tg mice but did not affect the survival of mice over the course of this study.

TABLE 2.

Effects of drug treatment on host defense against P. carinii in HuCD4/Tg mice

| Treatment | No. of P. carinii cells in lungs (log10 [mean ± SD]) | P. carinii-specific IgG level in serum (OD at 1/100 [mean ± SD]) | % CD3+ CD4+ lymphocytesa (mean ± SD) | % CD3+ CD8+ lymphocytesa (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 4.06 ± 0.00 | 0.84 ± 0.38 | 14.66 ± 5.29 | 5.57 ± 4.01 |

| Keliximab (25 mg/kg) | 6.95 ± 0.11*c | 0.01 ± 0.02* | 3.11 ± 1.85* | 4.68 ± 3.39 |

| Keliximab (250 mg/kg) | 6.79 ± 0.27* | 0.01 ± 0.04* | 1.62 ± 0.93* | 7.61 ± 2.18 |

| Cortisone acetateb | 6.39 ± 0.23* | 0.07 ± 0.06* | 4.19 ± 1.66* | 5.53 ± 3.94 |

Peripheral blood samples were collected at the termination of the study.

Data from four mice only, since six mice died (days 34, 36, 38, and 41) during the course of the study.

*, statistically significant decrease in comparison to control (P < 0.05).

Effect of keliximab on C. albicans infection.

HuCD4/Tg mice were treated with three daily doses of 1 or 100 mg/kg to achieve cumulative doses of 3 and 300 mg/kg, respectively, prior to challenge with C. albicans. As shown in Table 3, the general immune function of the host defense, measured as the survival rate during systemic infection, was not affected by the treatment with keliximab at either a low or a high dose. In contrast, treatment of HuCD4/Tg mice with dexamethasone caused a significant (P < 0.05) decrease in median survival time. Similarly, in a nonlethal model of local infection, C. albicans CFU counts on day 6 in the infected muscle were not affected by the treatment with keliximab, while dexamethasone caused up to a 1.5-fold increase in C. albicans colonization of the muscle (data not shown). Increased CFU in the muscle is a reflection of inhibition of the clearance of C. albicans from the site of infection. A lack of suppression of the pathogen clearance rate, which is influenced by T-cell infiltration, indicates that treatment with keliximab did not potentiate infection with C. albicans. Keliximab at the high but not the low dose caused a reduction in the anti-C. albicans antibody response, while dexamethasone totally suppressed humoral immunity to C. albicans (Table 3). Based on these data, the partial inhibition of antibody production by keliximab did not impact the other effector functions involved in host defense against primary infection with C. albicans in CD4+ cell-deficient mice.

TABLE 3.

Effects of drug treatment on host defense against C. albicans in HuCD4/Tg mice

| Treatment | Survival time (days after challenge [median]) | C. albicans-specific IgG level in serum (OD at 1/20 [mean ± SD]) |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 5.0 | 0.53 ± 0.18 |

| Keliximab (1 mg/kg) | 6.0 | 0.56 ± 0.20 |

| Keliximab (100 mg/kg) | 5.0 | 0.21 ± 0.14 |

| Dexamethasone | 1.0a | 0.07 ± 0.02a |

Statistically significant decrease in comparison to control (P < 0.05).

Effect of keliximab on B16 melanoma metastasis.

Treatment of HuCD4/Tg mice with keliximab administered as four weekly doses (prior to challenge and through 3 weeks postchallenge) at 25 or 250 mg/kg did not affect B16 melanoma metastasis to lungs (Table 4). As expected, treatment with two doses (on days −1 and 2) of rabbit AAGM-1 (1/10) serum resulted in increased numbers of pulmonary metastatic foci in this model. Since keliximab and AAGM-1 target different cell populations (CD4+ T cells and NK cells, respectively) involved in controlling tumor metastasis, another anti-T-cell antibody, Thy1.2, was used for comparison. Administration of a single dose of Thy1.2 (0.5 mg/mouse, approximately equivalent to 20 mg/kg) prior to challenge with B16 tumor cells resulted in a significant (P < 0.05) increase of metastases in lungs (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Effects of drug treatment on B16 melanoma tumor metastases in HuCD4/Tg mice

| Treatment | No. of foci in lungsa [median (range)] |

|---|---|

| Vehicleb | 19 (9–27) |

| Keliximab (25 mg/kg) | 16 (8–30) |

| Keliximab (250 mg/kg) | 19 (10–34) |

| AAGM-1 | 57 (37–90)c |

| Thy1.2 | 113 (101–130)c |

Mice received i.v. injections of 0.5 × 106 to 1 × 106 B16F11 cells on day 1 and were sacrificed on day 21.

Results represent two combined experiments.

Statistically significant decrease in comparison to control (P < 0.05).

All the agents affected lymphocyte populations in peripheral blood. As shown in Table 5, AAGM-1 decreased the total lymphocyte count, including CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, by 50%, and NK cells, by >70%. Treatment with Thy1.2 was associated with over 90% depletion of both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. Keliximab caused a dose-dependent, selective depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes with no effect on CD8+ cells. Results of lymphocyte subset analysis in relationship to the drug effects on B16 melanoma metastasis in HuCD4/Tg mice indicated that selective depletion of CD4+ T cells did not compromise mechanisms involved in controlling melanoma tumor spread. In contrast, concomitant depletion of NK cells, CD4+ cells, and CD8+ cells by AAGM-1 or severe depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes by Thy1.2 significantly impaired host resistance to B16 melanoma.

TABLE 5.

Effects of drug treatment on blood lymphocyte subsets in HuCD4/Tg mice challenged with B16F11 melanoma tumor cells

| Treatment | Absolute lymphocytesa (cells/μl [mean ± SD]) | CD2+ CD3+ DX5+ (NK) cells

|

CD2+ CD4+ CD8− cells

|

CD2+ CD4− CD8+ cells

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (Cells/μl) | (%) | (Cells/μl) | (%) | (Cells/μl) | ||

| Vehicle | 8,227 ± 733 | 6.4 | 527 | 27.7 | 2,279 | 23.0 | 1,892 |

| Keliximab (25 mg/kg) | 6,606 ± 771 | NDb | ND | 5.9 | 390 | 27.1 | 1,790 |

| Keliximab (250 mg/kg) | 6,357 ± 352 | ND | ND | 0.9 | 57 | 29.8 | 1,894 |

| AAGM-1 | 3,806 ± 393 | 4.0 | 152 | 32.1 | 1,228 | 22.9 | 872 |

| Thy1.2 | 4,183 ± 237 | 8.0 | 335 | 1.3 | 54 | 1.4 | 59 |

Analysis was performed within 48 h after tumor cell injection.

ND, not done.

In summary, keliximab administered at up to a 250- to 300-mg/kg dose, despite causing a marked depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes, was not suppressive in host defense models if the mechanisms were not solely dependent on CD4+ T-cell-mediated responses (i.e., anti-P. carinii immunity). Since the generation of adoptive immunity to infectious agents is a complex process in which cytokines provide signals to direct immune responses, we investigated keliximab further by characterizing its effects on Th1 and Th2 cytokine production.

Effect of keliximab on Th1- and Th2-type cytokines.

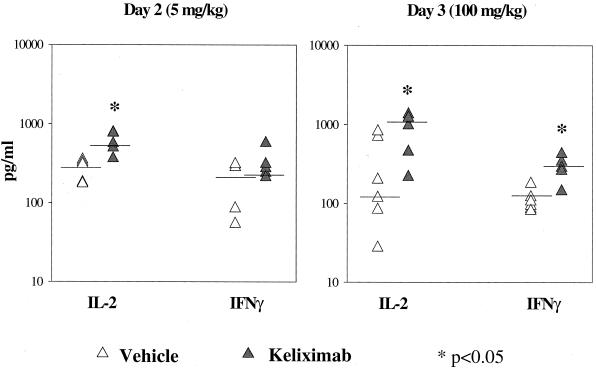

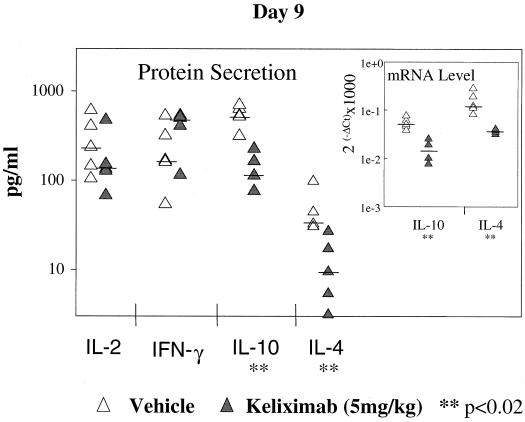

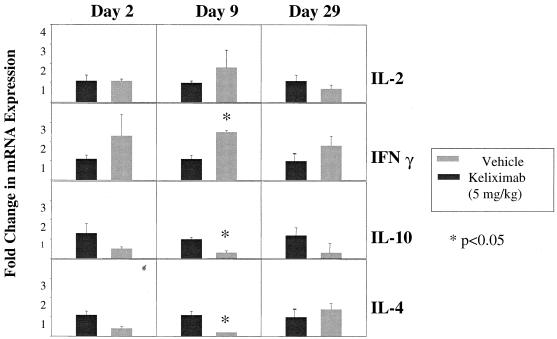

In this part of the study, a monoclonal anti-mouse CD3 antibody which provides a strong TCR signal for T-cell activation was used to induce cytokine expression in isolated splenocytes from keliximab-treated HuCD4/Tg mice. Keliximab was administered as a single i.v. injection of 5 or 100 mg/kg. Ex vivo expression of cytokines involved in type 1 (IFN-γ and IL-2) and type 2 (IL-4 and IL-10) immune responses was evaluated. While IFN-γ and IL-4 are associated with the differential switch of T-helper cells to the Th1 and Th2 phenotype, respectively, production of IL-2 and IL-10 may be less restricted. Keliximab at both a low and a high dose caused an increase in IL-2 protein production (P < 0.05) in splenocytes collected on days 2 and 3 posttreatment, respectively (Fig. 5). Splenocytes obtained from mice treated with the 100-mg/kg dose showed a particularly strong up-regulation of type 1 cytokines in response to anti-CD3 MAb, as the median values of protein levels were approximately 10-fold higher for IL-2 and 3-fold higher for IFN-γ than the respective median values for control mice (Fig. 5). This up-regulation was transient, since on days 7 and 14 posttreatment the production of IL-2 and IFN-γ in splenocytes from keliximab- and vehicle-treated mice was similar (data not shown). The initial increase in the production of type 1 cytokines in keliximab-treated mice was followed by a change in the production of type 2 cytokines. As shown in Fig. 6, splenocytes stimulated on day 9 posttreatment (5 mg/kg) showed no effect on IL-2 and IFN-γ but showed a statistically significant decrease in expression of IL-4 and IL-10. Cytokine production in in vitro-stimulated splenocytes on day 29 postdosing with keliximab was no longer different from the controls. In addition to cytokine analysis at the protein level in supernatants, cellular fractions of the anti-CD3 MAb-stimulated splenocytes from mice treated with 5 mg of keliximab per kg were also evaluated for cytokines at the gene expression level. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the mean fold change in mRNA expression corroborated the cytokine secretion profile of HuCD4/Tg mice treated with keliximab. Overall, during the course of this study we found that in the presence of CD4 coating by keliximab, effector cells in splenocytes with the reduced number of CD4+ T cells had the increased capacity to synthesize Th1-like cytokines in response to the activation through TCR, which then resulted in transient suppression of a Th2-like response. The subsequent changes in type 1 and type 2 cytokine production suggest a feedback reaction to keliximab-mediated effects on CD4+ T cells.

FIG. 5.

Up-regulation of Th1-like cytokines. HuCD4/Tg mice (five per group) received either 5 or 100 mg of keliximab per kg on day 1 and were sacrificed on day 2 or day 3, respectively. Splenocytes were activated in vitro with soluble anti-CD3 MAb (1 μg/ml), and the supernatants were tested for cytokines by ELISA. Individual and median values for each cytokine (IL-2 and IFN-γ) and statistical comparisons between control and keliximab-treated mice are presented.

FIG. 6.

Down-regulation of Th2-like cytokines. HuCD4/Tg mice (five per group) that received 5 mg of keliximab per kg on day 1 were sacrificed on day 9. Anti-CD3 MAb-activated splenocytes were tested for cytokine proteins by ELISA and for mRNA expression by FRET-based real-time RT-PCR (graph insert). Individual and median values for each cytokine and statistical comparisons between control and keliximab-treated mice are presented.

FIG. 7.

Kinetics of cytokine expression at mRNA level. HuCD4/Tg mice received 5 mg of keliximab per kg on day 1 and were sacrificed on days 2, 9, and 29 (five per group per time point). Splenocytes from individual mice were evaluated. Total RNA from anti-CD3 MAb-activated splenocytes was extracted and analyzed for mRNA expression by FRET-based real-time RT-PCR. Fold change in mRNA expression was calculated by dividing the mRNA levels in individual samples of keliximab-treated mice by the mRNA levels of vehicle-treated mice. The group mean values of fold change for each cytokine are presented.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this work was to understand the events that influence host responses to infections and tumors during induction of CD4+ T-cell depletion by treatment with keliximab, designed as a therapeutic agent for autoimmune diseases. Based on three models of host defense evaluated in the same host, HuCD4/Tg mice, keliximab did not cause a broad immunosuppression. Only in a model of chronic infection with P. carinii did HuCD4/Tg mice treated with keliximab become susceptible to primary infection; however, this treatment did not cause lethality, in contrast to cortisone acetate-mediated effects. While previous work has shown that anti-CD4 antibodies increase susceptibility to P. carinii (20, 49), more recent studies have demonstrated that a heavy burden of P. carinii did not lead to lethality in mice unless pulmonary inflammation and sequential PCP were developed (53). Our study has not been designed to evaluate symptoms of PCP, but nevertheless no apparent signs of the disease were observed during the treatment with high doses of keliximab that caused severe CD4+ depletion. Hence, CD4+ deficiency per se might not be as hazardous in P. carinii infection as has been previously described. Also, it has been demonstrated that a host with previously acquired immunity to P. carinii (carrying anti-P. carinii antibodies) maintains resistance to subsequent P. carinii infection despite depletion of CD4+ T cells (21). Regarding treatment with keliximab, it is tempting to speculate that a mild CD4+ depletion induced by lower, more clinically relevant doses (up to 5 mg/kg) would not cause increased susceptibility to P. carinii even in the primary infection. Nonetheless, due to the immunogenicity of the compound, the lower doses of keliximab could not be evaluated in this model.

Immunogenicity and anaphylaxis of keliximab, a human and cynomolgus monkey chimeric protein wholly foreign to mice, in HuCD4/Tg mice are not surprising. However, understanding of the inverse dose response of keliximab antigenicity requires insight into its pharmacological activity. High doses of keliximab can suppress antibody responses to itself and other highly antigenic proteins such as ovalbumin, even when immunization is done with a strong adjuvant such as complete Freund's adjuvant, which is consistent with other reports (28). At low doses, when CD4-mediated functions are only partially affected, the balance between the immunogenic potential of human anti-CD4 antibodies in the mouse and its capacity to block the humoral response is shifted towards immunogenicity. At the fully pharmacologically active doses used in our studies, keliximab-induced suppression of the production of antibodies against P. carinii and C. albicans in HuCD4/Tg mice is expected and consistent with numerous papers reporting the ability of anti-CD4 antibodies to inhibit humoral immune responses to various antigens (7, 10, 18, 25).

Our results with C. albicans infection further support immunomodulatory effects of keliximab. In this model, phagocytic cells play a dominant role in the early host response (3, 40); however, antigen-driven specific immune responses determine the ultimate outcome (4, 34, 50), and a role of CD4+ T cells in systemic C. albicans infection has been established by several investigators (5, 8). In this study, despite a significant reduction of peripheral CD4+ T cells and a decreased anti-C. albicans antibody response, keliximab did not affect either survival time in response to systemic challenge or clearance of localized infection with C. albicans. Our data are supported by Fidel et al. (14), who reported that anti-CD4 antibody had little effect on host defense against vaginal Candida infections. In contrast, findings by Romani et al. (45) indicate that GK1.5-induced CD4+ depletion resulted in the development of fatal candidiasis by the attenuated yeast vaccine, and these effects were attributed to down-regulation of IL-2 and IFN-γ. Immunoregulation associated with production of Th1 and Th2 cytokines may be an important factor in host defense against C. albicans infection. Based on the reported in vivo association of Th1 immune responses with the acquired resistance to candidiasis (44) and our ex vivo work demonstrating Th1-type cytokine up-regulation in response to stimulation with anti-CD3 antibody, it is conceivable that the maintenance of a normal response to C. albicans seen in our study is attributed to this immunomodulatory feature of keliximab. The observed increase in IFN-γ in ex vivo stimulated splenocytes from mice treated with keliximab might be a result of selective emigration of Th1 cells from lymph nodes to the spleen, induced via modulation of chemokine receptors which are differentially expressed on Th1 and Th2 cells (2). In our study, induction of IFN-γ in the spleens of keliximab-treated mice was associated with subsequent suppression of IL-4, indicating polarization of the immune response. This polarization toward the Th1 response could be beneficial during C. albicans infection.

Administration of GK1.5 (rat anti-mouse CD4 MAb) in BALB/c mice conferred protection against an otherwise lethal inoculation of Leishmania major (11, 30, 31, 46). Protection was associated with enhanced IFN-γ production approaching levels similar to those detected in resistant C57BL/6 mice. In contrast, in vivo treatment of naïve DBA/2 mice with GK1.5 resulted in the preferential elimination of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells with concomitant promotion of Th2 responses, as evidenced by increased anti-sheep red blood cell antibody production and IL-4 cytokine expression (14). Most likely, differences in the age and strain of mice are factors contributing to the opposing results. It has been reported that age strongly influences how the CD4 compartment recovers from acute CD4 T-cell depletion; for instance, older mice exhibit delayed recovery as well as functional impairment of Th2 responses (16). It is also well established that different strains of mice have dissimilar susceptibilities to infectious agents associated with differential expression of CD4 lymphokines (23). Thus, strain and age differences between mice used by different investigators may be a reason for different propensities toward Th1- and Th2-like responses after treatment with keliximab and GK1.5, respectively. Alternatively, keliximab has a very different pattern of immunoregulation than anti-murine CD4 GK1.5.

In humans, treatment with the anti-CD4 MAb cM-T412 was associated with an increase in the Th1-to-Th2 ratio, as IFN-γ-producing cells remained stable and IL-4-producing T-helper cell numbers were reduced (43). This supports our data suggesting that keliximab therapy may be beneficial, as a temporary increase in the Th1-to-Th2 cytokine ratio may result in enhanced host defense.

Finally, in our B16 melanoma tumor model, the absence of an effect of keliximab and the detrimental effect of Thy1.2 on host resistance are consistent with previous work, which has shown that depletion of both CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes increases the rate of spontaneous metastases (35, 47) and that CD8+ lymphocytes play the major role in T-cell-mediated antitumor immune responses (33). This finding, however, does not rule out a role for CD4+ lymphocytes in tumor defense, as evidence for both suppression (52) and augmentation (42) of antitumor activities upon depletion of CD4+ cells with anti-CD4 antibodies has been reported. It is well established that in addition to NK cell killing, IFN-γ plays an important role in the clearance of tumor burden and the immune response to various tumors, including melanoma (36). Thus, an enhanced ability to produce IFN-γ following treatment with keliximab may be beneficial to the host challenged with tumor cells.

In summary, in light of conflicting reports on the effects of CD4+ cell depletion in different models of host defense, we feel that a strength of this work lies in using the same mouse type (strain and age) in a broad range of models, which address both CD4-dependent mechanisms (P. carinii) and a combination of CD4-dependent and -independent mechanisms (C. albicans and B16 melanoma) of host defense. Furthermore, the anti-human CD4 antibody keliximab was evaluated in vivo in HuCD4/Tg mice challenged with a massive inoculum of a microbe or tumor cells as well as a slow and natural exposure to a microbial pathogen. Based on this work in the antigen-challenged host and previously published work on pharmacological potential (41), keliximab-induced CD4+ cell reduction may present a more favorable safety profile than conventional broad-spectrum immunosuppressive therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We gratefully acknowledge and thank Caroline Gennell for purification and preparation of the Thy1.2 monoclonal antibody for this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson D, Chambers K, Hanna N, Leonard J, Reff M, Newman R, Baldoni J, Dunleavy D, Reddy M, Sweet R, Truneh A. A Primatized MAb to human CD4 causes receptor modulation, without marked reduction in CD4+ T cells in chimpanzees: in vitro and in vivo characterization of a MAb (IDEC-CE9.1) to human CD4. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;84:73–84. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Annunziato F, Cosmi L, Galli G. Assessment of chemokine receptor expression by human Th1 and Th2 cells in vitro and in vivo. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:691–699. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.5.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashman R B, Papadimitriou J M. Susceptibility of beige mutant mice to candidiasis may be linked to a defect in granulocyte production by bone marrow stem cells. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2140–2146. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.2140-2146.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashman R B, Papadimitriou J M. Strain dependence of antibody-mediated protection in murine systemic candidiasis. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:511–513. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.2.511-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashman R B, Papadimitriou J M. Production and function of cytokines in natural and acquired immunity to Candida albicans infection. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:646–672. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.646-672.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cammarota G, Scheirle A, Takacs B, Doran D M, Knorr R, Bannwarth W, Guardiola J, Sinigaglia F. Identification of a CD4 binding site on the beta 2 domain of HLA-DR molecules. Nature. 1992;356:799–801. doi: 10.1038/356799a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carteron N L, Wofsy D, Seaman W E. Induction of immune tolerance during administration of monoclonal antibody to L3T4 does not depend on depletion of L3T4+ cells. J Immunol. 1988;140:713–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cenci E, Romani L, Vecchiarelli A, Puccetti P, Bistoni F. Role of L3T4+ lymphocytes in protective immunity to systemic Candida albicans infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3581–3587. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3581-3587.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doyle C, Strominger J L. Interaction between CD4 and class II MHC molecules mediates cell adhesion. Nature. 1987;330:256–259. doi: 10.1038/330256a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott B E, Ekblom P, Pross H, Niemann A, Rubin K. Anti-beta 1 integrin IgG inhibits pulmonary macrometastasis and the size of micrometastases from a murine mammary carcinoma. Cell Adhes Commun. 1994;1:319–332. doi: 10.3109/15419069409097263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elosevic M, Finbloom S, Van Der Meide P H, Slayter M V, Nacy C A. Administration of monoclonal anti-IFN-γ antibodies in vivo abrogates natural resistance of C3H/HeN mice to infection with Leishmania major. J Immunol. 1989;143:266–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elvin P, Evans C W. Cell adhesion and experimental metastasis: a study using the B16 malignant melanoma model system. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1984;20:107–114. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(84)90041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fidel P L, Jr, Lynch M E, Sobel J D. Circulating CD4 and CD8 T cells have little impact on host defense against experimental vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2403–2408. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2403-2408.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Field E H, Rouse T M, Fleming A L, Jamali I, Cowdery J S. IFN-γ and IL-4 pattern lymphokine secretion in mice partially depleted of CD4+ T cells by anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 1992;149:1131–1137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filler S G, Der L C, Mayer C L, Christenson P D, Edwards J E J. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for quantifying adherence of Candida to human vascular endothelium. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:561–566. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleming A L, Field E H, Tolaymat N, Cowdery J A. Age influences recovery of systemic and mucosal immune responses following acute depletion of CD4 T cells. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;69:285–291. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson U E M, Heid C A, Williams P M. A novel method for real time quantitative RT-PCR. Genome Res. 1996;6:995–1001. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.10.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill H S, Watson D L, Brandon M R. In vivo inhibition by a monoclonal antibody to CD4+ T cells of humoral and cellular immunity in sheep. Immunology. 1992;77:38–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hahn H J, Kuttler B, Laube F, Emmrich F. Anti-CD4 therapy in recent-onset NIDDM. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1993;9:323–328. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610090413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harmsen A G, Stankiewicz M. Requirement for CD4+ cells in resistance to Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in mice. J Exp Med. 1990;172:937–945. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harmsen A G, Chen W, Gigliotti F. Active immunity to Pneumocystis carinii reinfection in T-cell-depleted mice. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2391–2395. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2391-2395.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heid C A, Stevens J, Livak K J, Williams P M. Real time quantitative PCR. Genome Res. 1996;6:986–994. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinzel F P, Sadick M D, Holady B J, Coffman R L, Locksley R M. Reciprocal expression of interferon-γ or interleukin-4 during the resolution or progression of murine leishmaniasis. Evidence for expansion of distinct helper T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 1989;159:59–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herzyk D J, Ruggieri E V, Cunningham L, Polsky E, Herold C, Klinkner A M, Badger A, Kerns W D, Bugelski P J. Single-organism model of host defense against infection: a novel immunotoxicologic approach to evaluate immunomodulatory drugs. Toxicol Pathol. 1997;25:351–362. doi: 10.1177/019262339702500403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirsch R, Chatenoud L, Gress R E, Bach J F, Sachs D H, Bluestone J A. Suppression of the humoral response to anti-CD3 mAB by pretreatment with anti-CD4 mAB. Transplant Proc. 1989;21:1015–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horneff G, Burmester G R, Emmrich F, Kalden J R. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with an anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:129–140. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isaacs J D, Watts R A, Hazleman B L, Hale G, Keogan M T, Cobbold S P, Waldmann H. Humanized monoclonal antibody therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1992;340:748–752. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92294-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin F S, Youle R J, Johnson V G, Shiloach J, Fass R, Longo D L, Bridges S H. Suppression of the immune response to immunotoxins with anti-CD4 monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol. 1991;146:1806–1811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Killeen N, Sawada S, Littman D R. Regulated expression of human CD4 rescues helper T cell development in mice lacking expression of endogenous CD4. EMBO J. 1993;12:1547–1553. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liew F Y, Hale C, Howard J G. Immunologic regulation of experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. V. Characterization of effector and specific suppressor T cells. J Immunol. 1982;128:1917–1922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liew F Y. Specific suppression of responses to Leishmania tropica by a clonal T cell line. Nature. 1983;305:630–632. doi: 10.1038/305630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindsey J W, Hodgkinson S, Mehta R, Siegel R C, Mitchell D J, Lim M, Piercy C, Tram T, Dorfman L, Enzmann D, et al. Phase 1 clinical trial of chimeric monoclonal anti-CD4 antibody in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1994;5:32–39. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.3_part_1.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lode H N, Xiang R, Becker J C, Gillies S D, Reisfeld R A. Immunocytokines: a promising approach to cancer immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;80:277–292. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyon F L, Hector R F, Domer J E. Innate and acquired immune responses against Candida albicans in congenic B10.D2 mice with deficiency of C5 complement component. J Med Vet Mycol. 1980;24:359–367. doi: 10.1080/02681218680000551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma D, Niederkorn J Y. Efficacy of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in the treatment of hepatic metastases arising from transgenic intraocular tumors in mice. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:1067–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Markovic S N, Murasko D M. Role of natural killer and T-cells in interferon induced inhibition of spontaneous metastasis of B16F10L murine melanoma. Cancer Res. 1991;51:1124–1128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mauri C, Chu C-Q, Woodrow D, Mori L, Londei M. Treatment of a newly established transgenic model of chronic arthritis with nondepleting anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 1997;159:5032–5041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosmann T R, Coffman R L. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Neill J K, Baker D, Davison A N, Allen S J, Butter C, Waldman H, Turk J L. Control of immune-mediated diseases of the central nervous system with monoclonal (CD4-specific) antibodies. J Neuroimmunol. 1993;45:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(93)90157-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papadimitriou J M, Ashman R B. The pathogenesis of acute systemic candidiasis in a susceptible inbred mouse strain. J Pathol. 1986;150:256–265. doi: 10.1002/path.1711500405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Podolin P L, Webb E F, Reddy M, Truneh A, Griswold D E. Inhibition of contact sensitivity in human CD4+ transgenic mice by human CD4-specific monoclonal antibodies: CD4+ T-cell depletion is not required. Immunology. 2000;99:287–295. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00946.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rakhmilevich A L, North R J. Elimination of CD4+ T cells in mice bearing an advanced sarcoma augments the anti-tumor action of interleukin-2. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1994;38:107–112. doi: 10.1007/BF01526205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rep M H, Van Oosten B W, Roos M T, Ader H J, Polman C H. Treatment with depleting CD4 monoclonal antibody results in a preferential loss of circulating naive T cells but does not affect IFN-gamma secreting TH1 cells in humans. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:2225–2231. doi: 10.1172/JCI119396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romani L, Mocci S, Bietta C, Lanfaloni L, Puccetti P, Bistoni F. Th1 and Th2 cytokine secretion patterns in murine candidiasis: association of Th1 responses with acquired resistance. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4647–4654. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4647-4654.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romani L, Mencacci A, Cenci E, Mosci P, Vitellozzi G, Grohmann U, Puccetti P, Bistoni F. Course of primary candidiasis in T cell-depleted mice infected with attenuated variant cells. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:1384–1392. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.6.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sadick M D, Heinzel F P, Shigekabe V M, Fisher W L, Locksley R M. Cellular and humoral immunity to Leishmania major in genetically susceptible mice after in vivo depletion of L3T4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1987;139:1303–1309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schild H J, Kyewski B, Von Hoegen P, Schirrmacher V. CD4+ helper T cells are required for resistance to a highly metastatic murine tumor. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:1863–1866. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830171231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharma A, Davis C B, Tobia L A, Kwok D, Tucci M G, Gore E R, Herzyk D J, Hart T K. Comparative pharmacodynamics of keliximab and clenoliximab in transgenic mice bearing human CD4. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shellito J, Suzara V V, Blumenfeld W, Beck J M, Steger H J, Ermak T H. A new model of Pneumocystis carinii infection in mice selectively depleted of helper T lymphocytes. J Clin Investig. 1990;85:1686–1693. doi: 10.1172/JCI114621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steinshamn S, Waage A. Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 in Candida albicans infection in normal and granulocytopenic mice. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4003–4008. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4003-4008.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waldor M K, Sriram S, Hardy R, Herzenberg L A, Herzenberg L A, Lanier L, Lim M, Steinman L. Reversal of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis with monoclonal antibody to a T-cell subset marker. Science. 1985;227:415–417. doi: 10.1126/science.3155574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weber S M, Shi F, Heise C, Warner T, Mahvi. M. D. Interleukin-12 gene transfer results in CD8-dependent regression of murine CT26 liver tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:186–194. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wright T W, Gigliotti F, Finkelstein J N, McBride J T, An C L, Harmsen A G. Immune-mediated inflammation directly impairs pulmonary function, contributing to the pathogenesis of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. J Clin Investig. 1999;104:1307–1317. doi: 10.1172/JCI6688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yocum D E, Solinger A M, Tesser J, Gluck O, Cornett M, O'Sullivan F, Nordensson K, Dallaire B, Shen C D, Lipani J. Clinical and immunologic effects of a PRIMATIZED anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody in active rheumatoid arthritis: results of a phase I, single dose escalating trial. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:1257–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]