INTRODUCTION

Melanoma is an aggressive form of skin cancer that, when localized, is highly curable with a simple surgical excision. However, as it grows in the span of just a few millimeters, its lethality increases markedly. More so than many other cancers, the management of melanoma is governed by phase III randomized trials in almost every aspect of treatment. Over the last 10 years, not only have there been several landmark surgical trials but also major advances in systemic treatments using targeted and immunologic approaches to metastatic disease. The availability of effective systemic therapies has led to rapid improvements in survival as well as significant alterations in the traditional approaches to managing this disease. This monograph is organized into 6 sections that provide focused updates on the advances in various aspects of melanoma care. These sections incorporate the latest findings and will help with the management of individual patients. In addition, we also aim to integrate all the approaches to melanoma to help providers better understand the evolving complexity of an integrated multidisciplinary care approach to optimize the care of these patients.

MELANOMA EPIDEMIOLOGY AND GENETICS

Incidence and Mortality

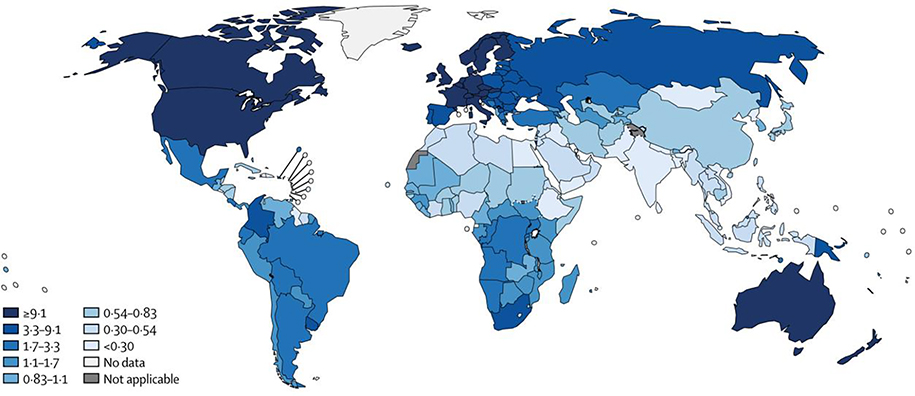

Cutaneous malignant melanoma (CMM) is the fifth most common malignancy in the United States, and it is by far the deadliest cutaneous cancer. The highest-incidence regions worldwide are North America, Australia, and Western Europe (Figure 1).1 Since the mid-1990s, the yearly incidence in the United States has increased by approximately 0.4% per year (Figure 2).2 For most of that period, overall mortality remained the same, with only a slight decline in the last 5 years, from 2.7% to 2.1%. Other nationwide databases in high-incidence areas have demonstrated similar trends,3,4 which are thought to reflect increased surveillance and detection with some recent improvement in mortality for advanced melanoma. Because most patients are diagnosed with curable stage I disease, 5-year overall survival (OS) for melanoma patients is 92%. However, approximately 6,850 Americans will die from melanoma in 2020, reflecting the deadly nature of advanced melanoma2. Despite recent improvements in chemotherapy and immunotherapy, advanced disease remains deadly and carries a 5-year OS of only 19%.5

Figure 1.

Melanoma incidence by country (per 100,000 person-years) (with permission from Schadendorf D, van Akkooi ACJ, Berking C, et al. Melanoma. Lancet. 2018;392(10151):971–984).

Figure 2.

Melanoma incidence and mortality in the United States by sex compared to other cancers 1975 to 2017 (with permission from Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:7–33).

Predisposition

Cumulative research into CMM epidemiology has identified a variety of factors that modify a person’s risk. Risk increases with age, with a notable inflection in incidence rates for both men and women after age 60 years. Men are more likely to be affected overall, an effect that is more pronounced at older ages. By age 65 years, men are 1.55 times more likely to develop melanoma. Perhaps as a result, the average age at diagnosis is lower for women.2, 5

Host Factors

Phenotype

The most prominent phenotypic factors that are associated with development of melanoma are skin pigmentation and presence or absence of melanocytic nevi. Skin pigmentation is largely determined by melanocyte synthesis of eumelanin (ie, dark complexion) or pheomelanin (ie, lighter complexion, blue eyes, and red hair). A pheomelanin-predominant pigmentation phenotype (rather than eumelanin) is associated with increased risk for melanoma. The features of this phenotype and the relative risk (RR) of melanoma are summarized in Table 1.6

Table 1.

Relative risk for melanoma associated with phenotypic factors.

| Relative Risk for Melanoma | |

|---|---|

| Phenotypic Factor | (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

| |

| Family history | RR = 1.74, 1.41–2.14 |

| Fitzpatrick skin type (I vs. IV) | RR = 2.09, 1.67–2.58 |

| High density of freckles | RR = 2.10, 1.80–2.45 |

| Skin color (fair vs. dark) | RR = 2.06, 1.68–2.52 |

| Eye color (blue vs. dark) | RR = 1.47, 1.28–1.69 |

| Hair color (red vs. dark) | RR = 3.64, 2.56–5.37 |

Adapted from Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, et al. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: III. Family history, actinic damage and phenotypic factors. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(14):2040–2059.

Pheomelanin-predominant phenotypes are also associated with sunburn of the skin when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) radiation (UVR), which causes DNA damage. Eumelanin is protective against UVR-mediated sunburn. A personal history of sunburn, a reported tendency to sunburn, and especially a tendency for blistering sunburn are all associated with increased melanoma risk.7, 8 Additionally, estimates of total lifetime UV radiation exposure, especially when intermittent, have been shown to be associated with increased risk.9

Regarding melanocytic nevi, both the number and quality of nevi seem to convey risk.10, 11 There is a steady increase in CMM risk that is proportional to total body nevus count; RR reaches as high as 6.9 for those with more than 100 total nevi.10, 11 The characteristics of cutaneous nevi are also relevant. “Atypical” or “clinically dysplastic” are terms used to refer to large (>5 mm), flat nevi with abnormal clinical features, such as poorly defined borders, variegated color, uneven contour, or erythema. Patients with a single atypical nevus have a 2-fold increase in melanoma risk.12 The presence of at least 10 atypical nevi carries a RR of 12.12 On the other hand, congenital nevi do not seem to predispose to melanoma.12

Medical History

Risk for development of melanoma has also been related to factors in a patient’s personal and medical history. Medical factors, especially prior cutaneous or noncutaneous malignancy, have been described. Also, personal factors such as environmental exposure have been studied in melanoma epidemiology.

History of skin damage predisposes to melanoma. Actinic skin changes are a long-term effect of UVR-mediated DNA damage and are a precursor to skin cancers. Increased risk for melanoma is seen in those with a history of actinic damage alone (RR = 2.02, 95% CI 1.24–3.29), and those with a history of premalignant or malignant nonmelanoma skin lesions (RR = 4.28, 95% CI 2.80–6.55).6

Personal history of noncutaneous cancer has also been shown to be a risk factor. Melanoma is an important cause of second primary malignancy in patients who have recovered from common childhood cancers.13 Significantly, childhood cancer survivors who develop melanoma are more likely to die of their disease than other primary melanoma patients (hazard ratio = 2.57; 95% CI, 1.55–4.27).14 In addition to childhood cancer, adult hematologic malignancies such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)15 or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma16 are associated with subsequent development of melanoma, possibly due to disruption of normal immune function.

Melanoma is an immunogenic cancer, and a variety of immune system impairments have been associated with increased risk. Specifically, the solid organ transplant (SIR = 2.20, 95%CI 2.01–2.39)17, 18 and hematopoietic stem cell transplant (hazard ratio = 5.5, 95% CI, 1.7–17.7)19 populations have been found to be at risk. Solid organ transplant recipients who develop melanoma have an increased mortality risk of approximately 3–4 times other melanoma patients.17, 18 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients were previously shown to be a high-risk population;20 however, this finding has been disputed.21

Genetic Risk

A patient’s genetic risk should also be considered. Familial melanoma is discussed in detail in a subsequent section, but familial cases can often be linked to: (1) a small number of high-penetrance loci (eg, CDKN2A, CDK4); (2) an increasingly large number of low-penetrance loci; (3) a familial cancer syndrome that includes melanoma and other cancers (Cowden syndrome, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, BRCA2); or (4) rare genodermatoses such as xeroderma pigmentosum.22

Environmental Factors

Environmental exposures can modify patients’ risk for melanoma. These factors invariably relate to lifetime UVR exposure. The UV radiation that is responsible for skin damage is primarily from the UVA (315–400 nm) and UVB (280–315 nm) spectra. UVB radiation is absorbed directly by DNA macromolecules, and primarily causes damage via pyridine cyclodimerization, often affecting adjacent thymine residues.23 This damage is repaired by the nucleotide excision repair apparatus. UVA radiation represents approximately 95% of sunlight UV radiation and is the primary source of radiation in tanning beds. UVA also creates thymine dimers, but additionally can cause indirect oxidative damage to DNA.24 The characteristic point mutation from UV damage is T->C.

Perhaps the most extensively studied environmental factor is tanning bed use. Once theorized to be potentially protective against UVR-mediated sun damage by inducing melanin production, it is now known that any exposure to tanning beds carries a measurable RR of melanoma.25 Risk appears to be higher among those with many tanning bed exposures, and those who use them at a younger age.26, 27 Notably, one study found that those with early-onset melanoma (prior to age 40 years) were much more likely to have used tanning beds at a young age.26

Lifetime sun exposure is also an important factor. Those who live in sunnier climates or low latitudes are at increased risk.4, 28 It follows that patients who are exposed to sunlight in their professional or leisure activities would also be at increased risk. This effect has been observed in airline pilots and crew.29

Different patterns in sun exposure may predispose to different molecular pathways for melanoma development. For example, BRAF-mutant cutaneous melanomas are more closely associated with intermittent, intense sun exposure (especially in younger years), and more melanocytic nevi.30 It has been observed that melanoma arising within nevi have the same activating oncogene mutations as adjacent benign nevus cells. Transformation may be the result of acquisition of additional mutations, such as CDKN2A homozygous deletion, resulting in subsequent clonal expansion.31, 32 In contrast, TP53-mutant cutaneous melanoma is more often associated with chronic sun exposure, actinic skin damage, and fewer nevi.33, 34

Melanoma Genetics

Molecular Oncogenesis of Melanoma

Melanoma has a very high mutational burden compared to other cancers, reflecting its status as a disease of DNA damage.35 Mutations detected in melanoma average more than 100 per Mb, the highest among common malignancies. The diverse mutational landscape places emphasis on the distinction between driver and bystander mutations. There are 3 main categories of mutation that drive melanoma molecular oncogenesis: 1) driver mutations in cell growth and survival signaling; 2) disruption of canonical cell cycle regulation mechanisms; and 3) pigmentation genes.

Driver mutations in cell growth and survival signaling.

Gain of function mutations in cell growth signaling proteins are common in melanoma. Most external growth factors signal through receptor tyrosine kinases, activating intracellular pathways such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (Figure 3).36 An activating BRAF mutation, V600E, is present in approximately one half of all melanoma cases.37 Because of its central function in growth signaling, BRAFV600E is an important therapeutic target for melanoma.38 Other key drivers of cell growth in melanoma are NRAS and PTEN (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Melanoma oncogenes that promote constitutive cell growth. Most cellular growth factors activate mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways (green) and AKT signaling (yellow) through receptor tyrosine kinases. Variants in BRAF or NRAS (red) are able to function in the absence of external stimuli to activate MAPK signaling. Through another pathway, PTEN inactivation (red) causes accumulation of PIP3, which mediates recruitment of AKT and its activating kinases. AKT activation strongly promotes cell growth. These growth pathways are overactive in melanoma. RAS, rat sarcoma virus (v-Ras) homologs such as KRAS, NRAS, HRAS; RAF, rat accelerated fibrosarcoma (v-RAF) homologs such as BRAF; MEK, MAPK/Erk kinase 1; Erk, extracellular signal-related kinase 1; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; PIP2/PIP3, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate or 3,4,5-trisphosphate; PDK1, 3-phosphoinositide dependent kinase 1; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; AKT, v-Akt murine thymoma homolog or protein kinase B.

Disruption of canonical cell cycle regulation mechanisms.

Melanoma growth is dependent on escape from typical growth arrest pathways.36 The CDKN2A locus, perhaps the most frequently mutated in melanoma, codes for 2 tumor suppressor genes that regulate cell growth, p16INK4a and p14ARF. The essential anticancer function of these proteins is summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Canonical cell cycle regulatory pathways that are disrupted by CDKN2A mutation. Transition from the G1 phase of the cell cycle to S phase is controlled by retinoblastoma protein (Rb). Phosphorylation of Rb is required for progression. p16INK4a controls this tightly regulated transition by inhibiting Rb phosphorylation. CDKN2A encodes a second tumor suppressor protein on an alternate reading frame, hence the name ARF. p14ARF regulates the function of MDM2 and MDM4, which inhibit p53 and promote its ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Without p14ARF, p53 is unable to function as a critical regulator of cell proliferation and DNA damage repair. Rb, retinoblastoma; CDK4/6, cyclin dependent protein kinases 4 and 6; INK4a, inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase 4; MDM2/4, mouse double minute 2 homolog and mouse double minute 4 homolog.

In summary, the collective function of TP53, MDM2/4, and p14ARF allow the cell to arrest proliferation in the setting of DNA damage. TP53 inactivating mutations are found in only 20% of melanomas; however, most melanomas overexpress MDM2/MDM4, which are downregulators of p53 via ubiquitin-mediated degradation.39 Loss of p53 may be a late event in melanoma biology and may be present in more advanced tumors. As depicted in Figure 4, p16INK4a, Cyclin D, CDK4, and Rb tightly regulate the G1-S cell cycle transition. Dysregulation of this mechanism can lead to unrestricted progression of the cell cycle and is observed in 90% to 100% of melanomas.40, 41

Pigmentation Genes.

MC1R codes for the melanocortin receptor on melanocytes and is a key source of variability in pigmentation between individuals. It is no surprise that MC1R variants are highly associated with melanoma risk.36 Studies have shown that the effect of MC1R extends beyond just pigmentation and photoprotection and may also lead to oncogenesis by non-pigmentation routes.42 Additionally, other genes related to melanocyte differentiation and function have been identified as recurrently mutated in melanoma. For example, MITF, a transcription factor required for melanocyte development, may serve as a “lineage survival oncogene” in melanoma, promoting growth by expressing proteins that are important during cell differentiation.43 Dependence on lineage-specific survival mechanisms has been described in melanoma and may convey sensitivity to certain therapeutics.44 Transcription factors associated with melanocyte differentiation can be used to subcategorize melanoma and suggest that melanoma can be phenotypically dynamic in response to therapy.

Molecular Genetics of Melanoma Subtypes

Acral lentiginous melanoma and mucosal melanoma have a somewhat different genetic signature than other histological variants of cutaneous melanoma.36 Each represents less than 2% of melanoma cases, but they are notable because they are associated with poorer outcomes. In both subtypes, KIT mutations are particularly common, which may provide a clinically actionable target in the future.45 Of note, KIT-mutated tumors usually do not have coexisting BRAF or NRAS mutations. Finally, desmoplastic melanoma is much more likely to harbor an NF1 mutation than other melanoma subtypes.

Modern molecular techniques have also allowed melanoma to be subcategorized by level of differentiation, as detected using expression of transcription factors.44 In response to therapy, some tumors develop a de-differentiated phenotype, resembling their neural crest predecessors. This phenomenon may happen in a stepwise pattern with distinct phenotypic progression. Future research will be directed to understanding the genetic and epigenetic events that mediate benign and malignant melanocyte differentiation.

Uveal melanoma is a rare and deadly melanoma subtype that occurs in the eye. Uveal melanoma is associated with mutations in the Gαq (G protein-coupled receptor) signal transduction pathway. Mutations in the BAP1, SF3B1, and EIF1AX genes are associated with aggressive disease. Interestingly, each locus is associated with a different pattern of aneuploidy in chromosomes 3, 6, and 8 that can convey high risk of aggressive disease. Gene expression profiling (GEP) is commonly used to stratify prognosis in uveal melanoma.46

Familial Melanoma

Approximately 5% to 12% cases of melanoma occur in a familial pattern.47, 48 Almost one half of these cases can be traced to a small number of high-penetrance loci, and 20% to 40% are specifically due to CDKN2A variants. However, 45% of familial cases are linked to low-penetrance variants or do not have an identified cause. Genome-side association studies have begun to elucidate some of the lower-frequency loci.

The CDKN2A locus is responsible for the most famous and well-studied familial melanoma syndrome, familial atypical mole malignant melanoma (FAMMM) syndrome, also known as B-K mole syndrome or dysplastic nevus syndrome (Table 2). However, only 2% of new melanoma diagnoses will harbor a germline CDKN2A variant. Guidelines are available to help clinicians identify high-risk patients who would most benefit from a referral to a genetic counselor. One well-described method, called the “Rule of Twos and Threes” was designed to identify patients with a 10% or higher risk of harboring a CDKN2A germline mutation (Table 3).49 Of note, these rules were developed in the Australian melanoma population and should be adapted by clinicians based on local population risk and on clinical suspicion.

Table 2.

Summary of commonly tested genes for familial melanoma.

| Gene Locus | Associated Cancers | Syndromes |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| CDKN2A (NCCN) | CMM, pancreatic cancer, others | FAMMM syndrome |

| TP53 (NCCN) | Osteosarcoma, CMM, breast cancer, many others | Li-Fraumeni syndrome |

| CDK4 (NCCN) | CMM | Familial CMM |

| BAP1 (NCCN) | Uveal melanoma, renal cell cancer, CMM, mesothelioma | |

| MITF (NCCN) | CMM, renal cell cancer | |

| POT1 | CMM, glioma, CLL, colorectal cancer | |

| PTEN | Breast, thyroid, uterine, renal, colorectal cancers. CMM. Hamartomatous disease including tricholemmoma and polyps | Cowden Syndrome |

| RB1 | Retinoblastoma, CMM, others | |

| BRCA2 | Breast and ovarian cancer, CMM, others | Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) |

|

| ||

| Other Notable Genes | ||

|

| ||

| MCRR (NCCN) | Associated with CMM risk | |

| BRCA1 | Breast & ovarian cancer, others. | HBOC |

| Possibly melanoma | ||

| TERT (NCCN) | Mutated in many cancers | |

| CHEK2 | Sarcoma, breast cancer, CMM | |

The 13 gene loci that are most commonly included in familial melanoma testing panels. NCCN is used to denote the 7 gene loci that are suggested by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines. CDKN2A, cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2a; TP53, tumor suppressor p53; CDK4, cyclin-dependent kinase 4; BAP1, BRCA-associated protein 1; MITF, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor; POT1, protection of telomeres protein 1; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; RB1, retinoblastoma; BRCA, familial breast cancer 2; MC1R, melanocortin receptor 1; BRCA1, familial breast cancer 1. TERT, telomerase reverse transcriptase; CHEK2, checkpoint kinase 2; CMM, cutaneous malignant melanoma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Table 3.

Rule of two’s and three’s for familial melanoma.

| • Any patient with three primary melanomas |

| • A patient with one primary melanoma and two 1st or 2nd degree relatives (same side) with a diagnosis of melanoma or pancreatic cancer |

With increasing availability of panel testing, suspicious probands can be tested for a variety of cancer susceptibility syndromes. Some of these feature melanomas as a “subordinate” cancer phenotype. Examples include Cowden syndrome, Lynch syndrome, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, and BRCA 2. More complex guidelines are available to assist the clinician in managing a proband with a dense cancer pedigree.50 Referral to a genetic counselor is recommended if there is suspicion of a familial cancer syndrome.

Modern screening panels for germline melanoma predisposition are usually composed of between 7 and 13 high-risk gene loci. A summary of the most commonly tested loci is presented in Figure 2. Genes that are suggested by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines are: CDKN2A, CDK4, MC1R, MC1R, TERT, MITF, BRCA2, and BAP1 (especially for uveal melanoma).

Screening for familial melanoma patients should be tailored to each patient’s estimated risk. Patient education is essential because self-examination is the most powerful tool for identifying suspicious lesions. Screening examinations are performed at 3- to 12-month intervals. Those with large numbers of nevi are examined more frequently. Adding images to the medical record helps with tracking of nevi in evolution. Of course, appropriate screening for other malignancies should also be performed if the patient is at risk.

Summary

Melanoma is the deadliest cutaneous malignancy and is a common cause of cancer mortality in North America, Australia, and Western Europe. Those with lighter complexion, increased sun exposure, and immunosuppression are at higher risk. Oncogenesis is dependent on DNA damage from UV radiation, and those with impaired DNA damage repair are predisposed to melanoma. Familial melanoma syndromes have been described and can be detected by targeted gene panels.

MELANOMA EVALUATION AND STAGING

Clinical Suspicion for Melanoma

The diagnosis of melanoma begins with clinical suspicion. Often, patients or their clinicians will notice an abnormal skin lesion on examination. Several methods have been developed to rapidly identify pigmented lesions that should be referred to a specialist for additional evaluation or biopsy. The characteristics of each lesion should be measured within the context of a patient’s overall risk. The ABCDE method51 (Figure 5) has been well-described and prospectively validated.52 Additional methods include the Glasgow 7-point checklist,53 and the “Ugly Duckling” method, which emphasizes cutaneous nevi that differ from others on the patient. The advantage of these criteria is that they can be utilized by dermatologists, other clinicians, and laypersons alike, increasing early detection of disease.54, 55 Figure 6 presents a clinical example of an atypical nevus that was later confirmed to contain melanoma.34 Routine screening of average-risk patients is uncommon, but some studies have suggested that it could be cost-effective.56 Screening for familial cases is discussed in the section on genetics. Finally, deep convolutional neural networks have been designed to employ machine learning methods for melanoma diagnosis. These interesting new techniques can parse melanoma from other skin lesions based on high-resolution images alone and may play a role in the future of melanoma surveillance.57

Figure 5.

American Academy of Dermatology ABCDE criteria (with permission from American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force for the ABCDEs of Melanoma, Tsao H, Olazagasti JM, et al. Early detection of melanoma: reviewing the ABCDEs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(4):717–723).

Figure 6.

Melanoma arising within a nevus. Note the characteristics of this lesion, such as variegated color, irregular borders, and distinct appearance compared to neighboring nevi (with permission from Rivers JK. Is there more than one road to melanoma? Lancet 2004;363(9410):728–730).

Evaluation of Suspicious Lesions

Excisional Biopsy

Diagnostic excisional biopsy is the standard of care for suspicious pigmented skin lesions.58 Preferred techniques include deep saucerization encompassing the entirety of the lesion, taking care not to transect the deep margin. Full-thickness excisions and punch biopsies are becoming less common because less invasive methods have been shown to be noninferior.59 Shallow shave biopsies are appropriate if melanoma is considered unlikely. A summary of biopsy techniques is provided in Table 3. Peripheral margins of 1 to 3 mm of clinically uninvolved skin are preferred to facilitate histopathologic interpretation. Pre-biopsy photographs are particularly helpful if more than 1 area is biopsied. Axial orientation of biopsy is less likely to disrupt lymphatic drainage of the area and future lymphoscintigraphy. If lesion size or location precludes excisional biopsy, full-thickness incisional or punch biopsy may be appropriate. Multiple representative biopsies can be considered for large, pigmented lesions.

Some melanoma diagnoses are made from incisional, shave, or punch biopsies with a positive margin. In these cases, repeat biopsy may be considered if there is suspicion that the tumor thickness was not adequately sampled. Rates of upstaging (increasing T-category) with repeat biopsy range from 6% to 14% depending on original biopsy type. Acral lentiginous and desmoplastic melanoma are most likely to be upstaged. The superficial spreading subtype has only a 1.4% risk of upstage.60

If a specimen contains dysplastic melanocytes without melanoma, studies have not shown a benefit to proceeding with surgical excision. In one study, less than 2% of these excisions resulted in a significant change in diagnosis.61 Some clinicians will discuss excision with the patient if there is high-grade dysplasia.

Evaluation of Biopsies

Biopsy specimens are systematically catalogued and evaluated in keeping with American Academy of Dermatology, the College of American Pathologists (CAP), and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC).58, 62–65 An example of a CAP Synoptic Report is included as a supplementary figure (Figure S1). For histopathologic staging, the essential characteristics of the specimen are the Breslow thickness, reported to 0.1 mm, and the presence or absence of ulceration.66 New to the 8th Edition of the AJCC guidelines, the binary measure of mitotic rate greater than or less than 1 mitosis per mm2 is no longer considered for histopathologic staging, but remains an important prognostic factor across all thickness categories. Margin status should always be reported. Microsatellitosis, when present, conveys important prognostic information and must be reported.67, 68 Other histologic features that may provide prognostic value are the presence of vertical growth phase, angiolymphatic invasion, neurotropism/perineural invasion, regression, and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).69–71 Melanoma has several distinct histologic subtypes; the prognostic importance of subtype has been disputed, with some exceptions.72 The lentigo maligna subtype is associated with greater subclinical horizontal spread.73 The desmoplastic subtype is locally aggressive and often has decreased/absent pigmentation. It is associated with increased sensitivity to immunotherapy and decreased risk of lymph node metastasis.74 If desmoplastic histology is described, further description of “pure” or “mixed” desmoplastic characteristics provides additional clinical information. Patients with “pure” desmoplastic tumors have an unusually low risk for regional lymph node metastasis and improved 5-year survival.75

Initial Evaluation

The initial evaluation for a new diagnosis of primary melanoma should include: (1) a detailed history, with review of environmental and genetic risk factors for melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer; (2) physical examination, with attention to local and regional lymph node basins; and (3) a complete skin examination. Abnormal findings should prompt additional investigation as appropriate. For melanoma of unknown primary, an anogenital/pelvic examination and detailed ophthalmologic examination are essential.

Laboratory and Imaging Evaluation

Baseline blood tests are only indicated if there is appropriate clinical suspicion. Routine laboratory studies are not cost-effective. As an example, routine serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is insensitive for metastatic melanoma.75 Routine use of chest radiograph (CXR) is also discouraged.76–79 Regarding advanced imaging techniques, positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) and nodal ultrasound (US) have increased sensitivity for metastasis when compared to physical examination, but the routine use of these imaging modalities in melanoma patients leads to high rates of false positive findings. Therefore, cross-sectional imaging has not been universally adopted as part of the initial evaluation for cutaneous melanoma, and nodal US is not a substitute for sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) or sampling of clinically positive nodes.80–84 Advanced imaging is appropriate for patients with an examination concerning for metastasis.

Cross-sectional imaging has a comparatively higher detection rate of occult distant metastasis in select patients with thick, ulcerated primary melanomas or bulky nodal disease, and may obviate the need for large surgical resection in these patients.37, 85–87 Using these criteria as requisites for advanced imaging may increase the detection rate for occult metastasis to 16%.86 For thick primary lesions with ulceration (at least T3b), some institutions recommend imaging prior to surgical excision.

Increased understanding of the molecular genetics of melanoma has resulted in the development of molecular testing to identify patients who might benefit from targeted therapeutics. Commonly available tests for melanoma include immunohistochemistry (IHC), GEP analysis via next-gen sequencing, and others.

Specific gene targets for molecular testing include BRAF, NRAS, KIT, and IHC for PD-L1. BRAF, a serine/threonine kinase which is central to cell growth signaling, is the most commonly mutated proto-oncogene in melanoma.88 Missense mutation of BRAF at codon V600 is responsible for 80% of activating BRAF mutations and conveys sensitivity to small molecule inhibitors such as vemurafenib and dabrafenib.88 IHC and sequencing tests for BRAFV600 are widely available, and some clinicians choose to include these tests as a part of the initial evaluation for patients who are considered at high risk for recurrence, such as those with category T2 or T3 primary tumors. Mutations in KIT, a receptor tyrosine kinase, are rare in cutaneous melanoma but present in 10% to 15% of mucosal and acral lentiginous melanomas. KIT mutants are detectable with molecular testing and provide a potential drug target for patients with these unusual but deadly melanoma subtypes.45 IHC positivity for PD-L1 greater than 1% is correlated with response to immune checkpoint blockade, but has poor predictive performance in melanoma.89 Thus, many clinicians will choose a trial of checkpoint blockade immunotherapy even in patients with low PD-L1 IHC staining.

GEP tests, for example DecisionDX-Melanoma (Castle Biosciences, Friendswood, Texas), classify melanoma patients as low- or high-risk based on a panel of transcripts detected in the tumor.90 It has been suggested that GEP tests can be used at diagnosis to supplement risk-stratification for early-stage patients with a negative SLNB. Because most new melanoma diagnoses happen at an early stage, and more than one half of deaths occur in patients who initially had a negative SLNB, identification of high-risk patients would be valuable.91 However, GEP tests are limited by low positive predictive value and a lack of strong evidence in large cohorts of patients to support their routine use at this time.92, 93 Currently, GEP tests are not recommended for treatment decisions in average-risk patients with cutaneous melanoma.94 They may be used in patients who are judged to be at high risk for recurrence or in the context of a clinical trial.

Staging

Complete histopathologic staging after wide local excision (WLE) +/− SLNB +/− completion lymph node dissection (CLND) is recommended. The AJCC staging method involves determination of the T, N, and M category of each tumor. The principles of TNM categorization for melanoma are depicted in Tables 4, 5, and 6. Tables 7 and 8 describe the assignment of stage based on TNM category. All recommendations reflect the AJCC 8th edition guidelines on melanoma, published in 2017.63, 64

Table 4.

Definition of N category for American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging.

| Extent of Regional Lymph Node and/or Lymphatic Metastasis |

||

|---|---|---|

| N Category | No. of Tumor-Involved Regional Lymph Nodes | Presence of In-transit, Satellite, and/or Microsatellite Metastases |

|

| ||

| NX | Regional nodes not assessed (ie, SLNB not performed, regional nodes previously removed for another reason); Exception: pathological N category is not required for T1 melanomas, use clinical N information |

No |

|

| ||

| N0 | No regional metastases detected | No |

|

| ||

| N1 | One tumor-involved node or any number of in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases with no tumor-involved nodes | No |

| N1a | One clinically occult (ie, detected by SLNB) | No |

| N1b | One clinically detected | No |

| N1c | No regional lymph node disease | Yes |

|

| ||

| N2 | Two or 3 tumor-involved nodes or any number of in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases with one tumor-involved node | |

| N2a | Two or 3 clinically occult (ie, detected by SLNB) | No |

| N2b | Two or 3, at least 1 of which was clinically detected | No |

| N2c | One clinically occult or clinically detected | Yes |

|

| ||

| N3 | Four or more tumor-involved nodes or any number of in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases with 2 or more tumor-involved nodes, or any number of matted nodes without or with in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases | |

| N3a | Four or more clinically occult (ie, detected by SLNB) | No |

| N3b | Four or more, at least 1 of which was clinically detected, or the presence of any number of matted nodes | No |

| N3c | Two or more clinically occult or clinically detected and/or presence of any number of matted nodes | Yes |

Adapted from Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th ed., Springer International Publishing; 2017:563–585.

SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Table 5.

Definition of T category for American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging.

| T Category | Thickness | Ulceration Status |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| TX: Primary tumor thickness cannot be assessed (eg, diagnosis by curettage) | Not applicable | Not applicable |

|

| ||

| T0: No evidence of primary tumor (eg, unknown primary or completely regressed melanoma) | Not applicable | Not applicable |

|

| ||

| Tis (melanoma in situ) | Not applicable | Not applicable |

|

| ||

| T1 | ≤1.0 mm | Unknown or unspecified |

| T1a | <0.8 mm | Without ulceration |

| T1b | <0.8 mm | With ulceration |

| 0.8–1.0 mm | With or without ulceration | |

|

| ||

| T2 | >1.0–2.0 mm | Unknown or unspecified |

| T2a | >1.0–2.0 mm | Without ulceration |

| T2b | >1.0–2.0 mm | With ulceration |

|

| ||

| T3 | >2.0–4.0 mm | Unknown or unspecified |

| T3a | >2.0–4.0 mm | Without ulceration |

| T3b | >2.0–4.0 mm | With ulceration |

|

| ||

| T4 | >4.0 mm | Unknown |

| T4a | >4.0 mm | Without ulceration |

| T4b | >4.0 mm | With ulceration |

With permission from Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th ed. Springer International Publishing; 2017:563–585.

Table 6.

Definition of M category for the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging.

| M Category | M Criteria |

|

|---|---|---|

| Anatomic Site | LDH Level | |

|

| ||

| M0 | No evidence of distant metastasis | Not applicable |

|

| ||

| M1 | Evidence of distant metastasis | See below |

|

| ||

| M1a | Distant metastasis to skin, soft tissue including muscle, and/or nonregional lymph node | Not recorded or unspecified |

| M1a(0) | Not elevated | |

| M1a(1) | Elevated | |

|

| ||

| M1b | Distant metastasis to lung with or without M1a sites of disease | Not recorded or unspecified |

| M1b(0) | Not elevated | |

| M1b(1) | Elevated | |

|

| ||

| M1c | Distant metastasis to non-CNS visceral sites with or without M1a or M1b sites of disease | Not recorded or unspecified |

| M1c(0) | Not elevated | |

| M1c(1) | Elevated | |

|

| ||

| M1d | Distant metastasis to CNS with or without M1a or M1c sites of disease | Not recorded or unspecified |

| M1d(0) | Not elevated | |

| M1d(1) | Elevated | |

With permission from Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 8th ed. Springer International Publishing; 2017:563–585.

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CNS, central nervous system.

Table 7.

Assignment of stage based on T, N, and M category: clinical stage group.

| When T is… | And N is… | And M is… | Then the clinical stage group is… |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Tis | N0 | M0 | 0 |

| T1a | N0 | M0 | IA |

| T1b | N0 | M0 | IB |

| T2a | N0 | M0 | IB |

| T2b | N0 | M0 | IIA |

| T3a | N0 | M0 | IIA |

| T3b | N0 | M0 | IIB |

| T4a | N0 | M0 | IIC |

| ANY T, TIS | ≥N1 | M0 | III |

| ANY T | ANY N | M1 | IV |

With permission from Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 8th ed. Springer International Publishing; 2017:563–585.

Table 8.

Assignment of stage based on T, N, and M category: pathological group.

| When T is… | And N is… | And M is… | Then the pathological stage group is… |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Tis | N0b | M0 | 0 |

| T1a | N0 | M0 | IA |

| T1b | N0 | M0 | IA |

| T2a | N0 | M0 | IB |

| T2b | N0 | M0 | IIA |

| T3a | N0 | M0 | IIA |

| T3b | N0 | M0 | IIB |

| T4a | N0 | M0 | IIB |

| T4b | N0 | M0 | IIC |

| T0 | N1b, n1c | M0 | IIIB |

| T0 | N2b, N2c, N3b or N3c | M0 | IIIC |

| T1a/b-T2a | N1a or N2a | M0 | IIIA |

| T1a/b-T2a | N1b/c or N2b | M0 | IIIB |

| T2b/T3a | N1a-N2b | M0 | IIIB |

| T1a-T3a | N2c or N3a/b/c | M0 | IIIC |

| T3b/T4a | Any N >N1 | M0 | IIIC |

| T4b | N1a-N2c | M0 | IIIC |

| T4b | N3a/b/c | M0 | IIID |

| Any T, Tis | Any N | M1 | IV |

With permission from Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 8th ed. Springer International Publishing; 2017:563–585.

Summary of AJCC Staging

Stages IA through IIC are principally determined by the T category of the primary lesion (ie, Breslow thickness and ulceration). Mitotic rate is no longer a criterion for T category but has prognostic value across all tumor thicknesses. T1 lesions (traditional “thin melanoma”) are up to 1 mm thick. T2 refers to 1 to 2 mm thickness, T3 to 2 to 4 mm thickness, and T4 to “thick melanoma” of Breslow thickness greater than 4 mm. T categories are modified with “a” or “b” to reflect the presence or absence of ulceration. Any nodal disease places the patient in stage III.

Stages IIIA-IIID refer to node-positive disease of any T category. N1 refers to one positive node, N2 to 2 or 3 nodes, and N3 to 4 or more nodes with detectable melanoma. The NXa & NXb designation denotes nodal disease that is clinically occult (“a” designation) or clinically evident (“b” designation). NXc denotes micro/macrosatellites or in-transit metastasis in addition to tumor-involved lymph nodes. Stage III is divided into 4 subcategories based on differential outcomes (Table 9). As usual, stage IV is reserved for distant metastasis. M categories all result in stage IV designation but are subdivided based on the anatomic location of the metastasis. M1a refers to skin/soft tissue and nonregional lymph nodes, M1b refers to lung metastasis, M1c refers to non-central nervous system (CNS) visceral metastasis, and finally M1d refers to CNS metastasis. Each M category is subdivided based on presence/absence of elevated serum LDH, which is an independent adverse predictor of survival across all M categories. LDH is also a useful indicator of disease response and recurrence in select patients.

Table 9.

Description of stage III subgroups.

|

With permission from Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al, ed. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 8th Ed. Springer International Publishing; 2017:563–585.

Stage-Specific Survival and Treatment Applications

Stage I melanoma has an excellent prognosis, with 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS) of 99% and 97% for stages IA and IB. Stage II is subdivided to IIA, IIB, and IIC, which have disease-specific 5-year survival of 94%, 87%, and 82%, respectively. Stage IIIA survival is 93%, which is higher than stages IIB and IIC. Patient reclassification with the 8th edition of the AJCC Guidelines resulted in an increase in survival for both of these groups, possibly due to the Will Rogers phenomenon95 (ie, when more accurate staging causes “stage migration” of a subset of patients, the average survival of both stages is increased). Stage IV survival is not subdivided, but new M category designations were designed to facilitate future research into the heterogeneity of metastatic melanoma.

Stage-specific disease management is a topic of current investigation. Although resection remains the standard for curable disease, there has been increasing interest in neoadjuvant therapy for patients presenting with stage III melanoma.96 Additional research is needed, but neoadjuvant therapy will be a central question in the future of melanoma management. Adjuvant therapies such as BRAF/MEK inhibitors (for BRAF-positive tumors) and immune checkpoint blockade are currently approved for stage IIIB/C/D patients and resected stage IV patients. Some stage IIIA patients are also eligible. These treatment modalities are also being studied in stage IIB/C disease, considering the poor 5-year survival in these patients.97 Intratumoral therapies are also an area of active research.98

CURRENT CONSIDERATIONS IN THE MANAGEMENT OF EARLY-STAGE MELANOMA

Early stage melanoma includes stage 0, I, and II melanomas as defined by the AJCC 8th edition staging system.99 These are essentially melanomas of any T classification with a negative lymphatic basin and no systemic metastasis. Early stage melanoma has a generally favorable prognosis, with 10-year survival ranging from 98% for stage IA disease to 75% for stage IIC disease.100 The mainstay of treatment is surgery, which includes resection of the primary tumor with adequate margins, and an evaluation of the tumor’s lymphatic basin using SLNB. The necessity and extent of each of these surgical procedures is guided by the histopathological evaluation of a biopsy taken from these lesions. Here, we review the current considerations and debates regarding each of these elements of treatment, from the biopsy itself, to the mode of excision and its necessary margins, as well as the indications and implications of a SLNB. We also briefly discuss novel molecular techniques and their potential role in these decisions.

Technique of Biopsy

The Breslow thickness of a melanoma has been shown to be the strongest predictor of prognosis.101, 102 Since the AJCC staging manual’s 6th edition, when the anatomical Clark level was abandoned, Breslow thickness has become the dominant variable, together with ulceration, defining the T classification.103 As a result, an accurate assessment of melanoma thickness is central to deciding on the clinical and surgical management of patients. Current NCCN guidelines, as well as the American Academy of Dermatology guidelines, recommend an excisional biopsy or at least a full thickness incisional biopsy (punch biopsy) to accurately assess Breslow thickness. They discourage the use of shave biopsy, as it can limit the assessment of depth, but allow its consideration in cases where the index of suspicion is low or for the assessment of lentigo maligna.104, 105

Shave biopsies have been proven to understage the Breslow thickness more than any other biopsy technique. Zager and colleagues59 show that residual tumor can be found upon final excision in up to 22% of cases. This residual tumor, left behind during shave biopsy, will cause an upgrading of the T classification upon final excision in 3% to 12.5% of cases. But interestingly enough, studies have shown that this upgrading rarely influences surgical recommendations and it does not seem to affect tumor recurrence or DSS.59, 106–108 Consequently, there have been calls for a change in biopsy recommendations.59 These calls have been fortified by data showing that almost two thirds (62.6%) of lesions diagnosed as melanoma are biopsied by dermatologists; and although the preferred mode of sampling for surgeons is an excisional biopsy and that of primary care physicians is a punch biopsy, dermatologists, as shown by both retrospective analyses and surveys, categorically prefer shave biopsies, rendering shave biopsy the leading means of melanoma diagnosis.106, 109 This understanding has led many, including NCCN panelists, to comment that “any diagnosis is better than none even if microstaging may not be complete,” vindicating the use of shave biopsy in the diagnosis of melanoma.105 Further discussion of the evaluation of malignant melanoma, including indications for systemic evaluation, can be found elsewhere in this monograph.

Excision of the Primary Tumor

WLE of the primary tumor has been the standard of care in melanoma surgery since the beginning of the 20th century. The aim of excision is removal of the tumor in its entirety with sufficiently clear microscopic margins to ensure the best chances for cure and local, regional, and systemic control. The historically accepted surgical margins, advocated by Handley110 in 1907, were 5 cm. These generous excision margins often led to the need for skin grafts and complex reconstruction, considerable wound complications, and eventual long-term morbidity. Led by the motivation to preserve function as well as aesthetics, and avoid the disfiguring nature of these procedures, a series of trials were published in the 1980s challenging this 5 cm paradigm.110, 111 The major randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that influence current margin recommendations are presented in Table 10. They can be generally divided into trials addressing excision margins in melanomas with a Breslow thickness of up to 2 mm and those which addressed thicker melanomas. Most of these trials exclude melanomas of the hands, feet, head, and neck, and the anogenital areas, as wider excisions in these anatomical locations are more morbid and less practiced.

Table 10.

Randomized controlled trials investigating thin resection margins for invasive melanoma.

| Group | Number of patients | Melanoma thickness | Excision margins | Follow up | Survival | Recurrence | Excluded | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veronesi et al., NEJM, 1988120 Veronesi et al., Arch Surg, 1991119 |

WHO melanoma program trial 10 | 612 | ≤2 mm | 1 vs 3 cm | 90 months | 8-year DFS 81.6% vs 84.4% 8-year OS 89.6% vs 90.3% |

14% vs 13% Local 1.3% vs 0% Lymphatic 6.9% vs 7.8% Distant 5.6% vs 4.6% |

Facial, fingers, toes | No local recurrence when thickness <1 mm |

| Ringborg et al., Cancer, 1996113 Cohn-Cedermark et al., Cancer, 2000112 |

1st Swedish melanoma group trial | 989 | 0.8–2 mm | 2 vs 5 cm | 11 years | 10-year DFS 81% v. 83% 10-OS 79% vs 76% |

21% vs 19% Local 0.6% vs 1% Lymphatic 15% vs 12% Distant 15% vs 14% |

Head & neck, hands, feet, vulva | |

| Khayat et al., Cancer, 2003114 | French cooperative group trial | 337 | <2.1 mm | 2 vs 5 cm | 16 years | 10-year DFS 85% vs 83% 10-year OS 87% vs. 86% |

Median time to recurrence 43 vs. 37.6 months 13.6% vs 20% recurrence Local 0.6% vs 2.4%, Lymphatic 8.1% vs 6.7% Distant 2.5% vs 6.1% |

Toe, nail, finger, acral-lentiginous | LND not performed |

| Balch et al., Ann Surg, 1993116 Balch et al., Ann Surg Oncol, 2001115 |

Intergroup melanoma surgical trial | 468 | 1–4 mm | 2 vs 4 cm | 72 months | 5-year OS 79.5% vs 83.7% 10-year OS 70% vs 77% |

Local 2.1% vs 2.6% Distant 10.9% vs 8.5% |

Primary closure in 89% vs 54% (p<.001) | |

| Gillgren et al., Lancet, 2011365 Utjés et al., Lancet, 2019366 |

2nd Swedish melanoma group trial (Scandinavian Baltic trial) | 936 | >2 mm | 2 vs 4 cm | 19.6 years | Melanoma specific mortality 41% vs 43.5% Overall mortality 65% vs 67% |

41.7% vs 42.5% Local 4.3% vs 1.9 Regional 4.1% vs 3.2% Lymphatic 21.5% vs 24.2% Distal 8.2% vs 11.5% |

hands, feet, head & neck, anogenital region | 9% underwent SLNB |

| Thomas et al., NEJM, 2004118 Hayes et al., Lancet Oncol, 2016117 |

UK Melanoma Study Group, the British Association of Plastic Surgeons and the Scottish Cancer Therapy Network | 900 | >2 mm | 1 vs 3 cm | 8.8 years | Melanoma specific mortality 42.8% vs 36.9% (p=0.041). Overall mortality 55.8% vs 53.9% (p=0.14) |

Local 3.3% vs 2.9% Locoregional 37% vs 31.8% (p=0.05) Distal 8.4% vs 6.7% |

General anesthesia in 32.1% vs 66.4% of patients |

DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; WHO, World Health Organization; LND, lymph node dissection; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Questioning the 5 cm margin, the Swedish Melanoma Group trial and the French Cooperative Group trial compared a 2 cm excision to a 5 cm excision in melanomas of up to 2 mm thickness. The Swedish study, including 769 patients, published its first findings in 1996, demonstrating a regional lymph node recurrence rate of 12.1% versus 8.3%, favoring the wider 5 cm excision. Nevertheless, both groups were comparable in overall recurrence rates (20.4% versus 20.5%); but more importantly, it showed a comparable 5-year OS of 86.4% and 88.7%, that was preserved upon long-term follow-up, with a 10-year OS of 79% and 76%, for a 2 cm versus 5 cm margin, respectively.112, 113 The French Cooperative Group trial, performing a second randomization of its 337 patients, assigning them to receive adjuvant isoprinosine or no adjuvant therapy, demonstrated similar findings. After a follow-up period of 19 years, the authors reported a recurrence rate of 13.6% versus 20% and a mortality rate of 19.8% versus 17.5% for 2 cm and 5 cm margins, respectively.114 These findings helped to establish a 2 cm margin as adequate for melanomas of up to 2 mm thickness.

This 2 cm margin was further investigated and shown to be adequate in melanomas of greater than 2 mm thickness. The Intergroup Melanoma Surgical Trial, led by Charles Balch, dealt with intermediate thickness melanomas of 1 to 4 mm, and randomized 486 patients to either a 2 cm or 4 cm excision margin. It showed comparable results, in terms of recurrence rates and 5- and 10-year OS, between the 2 groups; and although a narrow resection margin did not confer a negative prognostic effect, the authors demonstrated that both tumor thickness (RR=1.74, p=0.0008) and ulceration (RR=2.21, p=0.0095) conferred a statistically significant negative effect on survival. Moreover, they were able to demonstrate the negative effect a wider excision had on patient outcomes, in terms of a longer hospital stay (7.0 ± 5.1 versus 5.2 ± 4.5 days) and the ability to perform primary closure of the surgical site (54% versus 89%).115, 116

Noticing that the mean thickness of melanomas in the Intergroup trial was 1.96 mm, 2 groups investigated the feasibility of narrow margins in melanomas greater than 2 mm thickness. The 2nd Swedish Melanoma Group trial randomized 936 patients to a 2 cm versus 4 cm excision margin. With a follow-up of more than 19 years, they were able to show comparable recurrence rates (41.7% vs 42.5%), melanoma specific mortality (41% vs 43.5%), and overall mortality rates (55.8% vs 53.9%) between the 2 groups. The United Kingdom Melanoma Study group, together with the British Association of Plastic Surgery and the Scottish Cancer Therapy Network challenged the 2 cm margin, randomizing 900 patients with melanomas of more than 2 mm thickness to a 1 cm excision margin versus a 3 cm margin. They demonstrated similar overall mortality rates of 55.8% versus 53.9% between the 2 groups. Nevertheless, patients undergoing a narrow excision with 1 cm margins exhibited a higher locoregional recurrence rate (37% vs 31.8%, p=0.05) and worse melanoma specific survival (MSS, 42.8% vs 36.9%, 0=0.041).117, 118 These findings helped to establish the recommended margins for T3 and T4 melanomas as 2 cm.

As for thinner melanomas (≤2 mm), the World Health Organization (WHO) trial, led by Veronesi and Cascinelli, showed a narrow 1 cm excision margin to be equivalent to a wide 3 cm excision margin, in terms of 8-year OS (89.6% vs 90.3%). Disease-free survival (DFS), as well as recurrence rates, were likewise comparable between the 2 groups, with a recurrence rate of 14% and 13%, respectively. The authors were also able to show superior results in terms of DFS and OS in patients with 0.1 to 1 mm melanomas compared to those with 1.1 to 2 mm lesions, and that no patient with a melanoma less than 1 mm thickness recurred locally after excision with a 1 cm margin.119, 120 These results, in conjunction with findings showing that a margin narrower than 1 cm in these thin (≤1 mm) melanomas confers higher recurrence rates,121 established a margin of 1 cm as the recommended margin for up to 1 mm thick melanomas. These left melanomas of a 1 to 2 mm thickness in a controversial gray zone, with an ambiguous recommended margin of 1 to 2 cm. The MelmarT trial, an international multicenter RCT aims to answer this question, and is randomizing patients with melanomas of more than 1 mm thickness into 1 cm versus 2 cm resection margins.122 It is estimated to be completed in 2026 and will provide further guidance.

There are no similar RCTs for melanoma in situ, with the recommended excision margins being 0.5 to 1 cm.58, 105 Most authorities recognize a 0.5 mm margin as adequate for most melanoma in situ cases, but others advocate a wider excision. 58, 105, 123–125 One prospective database analysis showed, using Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), that a 6 mm excision margin confers a 86% clear margin rate, while a 9 mm margin allows for a 98.9% margin rate.124 Several other studies show similar results for both melanoma in situ and lentigo maligna, advocating margins up to 1.2 cm for head and neck tumors. Agreement does exist regarding the need for a wider margin than 0.5 cm for lentigo maligna, a subtype of melanoma that has a tendency for subclinical peripheral tumor extension.126 Table 11 summarizes the current recommendations for margins in primary cutaneous melanoma.

Table 11.

Recommended surgical margins for primary cutaneous melanoma.

Surgical margins are considered as measured during surgery from the edge of the lesion or post-excisional biopsy site.

For large or poorly defined melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type, a surgical margin or more than 0.5 cm can be considered.

Consider histologic margin assessment prior to reconstruction and closure (Adapted from the Cutaneous Melanoma NCCN Guidelines, Version 4.2020).105

Surgical Technique

Modern surgical techniques and excision margins usually allow for primary wound closure. More complex reconstructive techniques, such as skin grafting or tissue flaps, may be required for larger defects or those in challenging areas such as the face, scalp, or neck. In these cases, it is recommended to use grafts from the contralateral side in order to minimize the risk of local recurrence due to microscopic in-transit disease.111 It is recommended that excision is carried down to the depth of the underlying muscular fascia, but not necessarily including the fascia.58 No randomized trials have addressed the question of depth of resection or whether excision to the deep adipose layer is adequate.

The use of MMS in melanoma surgery, commonly complemented by melanoma antigen recognized by T-cells 1 (MART-1) immunostaining, is advocated by some authorities as an alternative for WLE, mostly in the dermatological literature. It is advocated not only for melanoma in situ and lentigo maligna, but also for invasive melanoma of up to 1 mm thickness. Several retrospective studies show MMS to be equivalent to WLE in terms of OS, MSS, and local recurrence in these patients, with some studies claiming superiority in terms of survival, especially in head and neck melanomas.127–130 It has also been shown that MMS is used more frequently than WLE in the face as well as in the scalp and neck areas, and several authors advocate its use in these areas where tissue conservation is critical.130, 131

Lymph Node Evaluation

The subject of immediate elective dissection of regional lymph nodes (ELND), in clinically node-negative melanoma patients, was an issue of controversy throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Although most authorities agreed that dissection was not necessary for patients with thin tumors with low-risk features, the definitions of thin and low-risk were debated. A prospective clinical trial conducted by the WHO, comparing ELND with follow-up and lymphatic dissection upon clinically detectable nodal involvement failed to show a difference in survival between the 2 groups, deeming observation a viable option in node-negative patients. This study also showed that only 20% of patients had lymphatic involvement, with lymph node involvement being directly related to melanoma thickness. This finding stressed that 80% of patients were unnecessarily exposed to the potential morbidity of lymphatic dissection, most notably lymphedema, with no benefit to their survival.132–134 Nevertheless, a survival advantage of 11% was found with ELND in the subgroup of patients with intermediate Breslow thickness lesions who had lymphatic involvement, either discovered upon ELND or diagnosed clinically during observation.134, 135

The need to identify this subset of patients with occult lymphatic disease led to the implementation of SLNB into the management of stage I and II melanoma. The technique, introduced by Morton and colleagues135 in 1992, incorporated preoperative planar lymphoscintigraphy with technetium-labeled dextran in ambiguously located tumors, such as the trunk, to designate the target lymphatic draining basin. Intraoperatively, blue dye was injected into the area of the tumor and the lymphatic channels were followed using meticulous dissection in the expected lymphatic basin until the sentinel lymph nodes were identified and excised. Later, the use of 99mTc-labeled albumin for intraoperative radiolymphoscintigraphy was added to the technique, enabling dual tracer identification of sentinel nodes. Morton was able to show the accuracy of the technique, with a false negative rate of 1%, establishing SLNB as a central part of the management of stage I and II melanoma. The technique was incorporated into the AJCC staging system in 2001.103, 135

The first Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-1) investigated the potential contribution of SLNB to the detection of occult lymph node metastases in patients with intermediate thickness melanoma (1.2 to 3.5 mm). This multicenter trial randomized patients to undergo WLE with SLNB or WLE with observation. In the SLNB arm, if the biopsy was positive, the patient underwent CLND. In the observation arm, if the patient developed clinically evident nodal disease, they then also returned to the operating room for CLND. The 5-year DFS rate was higher in the SLNB group (78.3% vs 73.1%, respectively, p=0.009), with similar 5-year MSS rates (87.1% vs 86.6%, respectively), findings that persisted in the final analysis. Nevertheless, much like the WHO trial, within the subgroup of patients with nodal metastases, patients who underwent SLNB with CLND had improved 5-year survival compared to those who had lymph node dissection (LND) upon clinical recurrence (72.3% vs 52.4%, respectively, p=0.004). In addition, SLNB was shown to be an important staging modality, as patients with nodal metastases upon SLNB were restaged as stage III and had significantly worse survival compared to those with a negative SLNB (72.3% vs 90.2%, respectively, p<0.001).136 Thick (>3.5 mm, in this study) melanomas were also evaluated, demonstrating similar 10-year DFS (50.7% vs 40.5%, in the SLNB+CLND vs. observation, p=0.03). Again, patients with positive SLNB had worse 10-year MSS compared to negative SLNB (62.1 vs 85.1%, p<0.001), further reinforcing the role of SLNB for staging purposes.137

These findings led international clinical and surgical oncology societies to recommend the use of SLNB in intermediate thickness melanomas, as well as in thick melanomas.138–141 The utility of SLNB in thin melanomas (≤1 mm) remains controversial. Although the incidence of nodal involvement in this group is low (approximately 5%), the majority (70%) of melanomas diagnosed in the United States are thin. As a result, a considerable number of melanoma deaths occur in patients who originally were diagnosed with thin melanoma. Subgroup analysis has demonstrated that the main predictor of SLNB positivity in thin melanoma is tumor thickness. Among patients with a tumor thickness of less than 0.75 mm, the rate of SLNB positivity is 2.7%, whereas for those with a thickness of 0.75 to 1 mm, it is 6.2%.142 Other risk factors do not predict sentinel node positivity as reliably. Among these risk factors are ulceration, mitotic rate, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), Clark level, tumor vertical growth phase, TILs, tumor regression, age, and others. The recommendation of most professional societies is to consider SLNB in melanomas 0.8 to 1 mm thick and those less than 0.8 mm thick with high-risk features, including ulceration, high mitotic rate and LVI, especially in younger patients.58, 105, 140, 141 Table 12 describes the recommendations for SLNB.

Table 12.

Recommendations for sentinel lymph node biopsy.

| Breslow thickness + other characteristics | NCCN recommendation* | ASCO + SSO recommendations** | % positive SLN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage IA (T1a): <0.8 with no ulceration | Not recommended, unless uncertain about adequacy of biopsy staging | Not recommded | <5% |

| Stage IB (T1b): <0.8 with ulceration or 0.8–1 mm with no ulceration T1a with adverse features (high mitotic index≥2/mm2 [in setting or young age], LVI, or a combination) |

Discuss with patient and consider SLNB | Discuss with patient and consider (does not include T1a tumors with adverse features) | 5–10% |

| Stage IB (T2a) or II: >1 mm | Offer SLNB (unless non-mitogenic or older patients, with a lower probability of positive SLNB) | Recommended for T2 and T3 tumors For T4 tumors, may be recommended |

>10% |

SLN, sentinel lymph node; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; SSO Society of Surgical Oncology.

If patient is unfit or unwilling to act based on SLNB findings, reasonable to forgo SLNB.

Adapted from the Cutaneous Melanoma NCCN Guidelines, Version 4.2020.105

Adapted from the ASCO and SSO clinical practice guideline update.140

Completion Lymph Node Dissection in Patients with a Positive Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy

With the implementation of SLNB in the management of stage I and II melanoma, 5% to 40% of patients will consequently be upgraded to stage III disease. MSLT-I demonstrated that these patients benefited from a SLNB complemented by CLND more than they did from observation. However, within the MSLT-I cohort, 88% of patients who had a single positive sentinel lymph node had no additional positive nodes upon CLND.49

In light of these findings, 2 major randomized trials set out to understand the value of CLND after a positive SLNB. First was the German Dermatologic Cooperative Oncology Group DeCOG-SLT trial, which was ended early due to low accrual and low event rate. It randomized 483 patients with at least 1 mm thick melanomas and a positive SLNB to undergo CLND or observation. Its results, published in 2016, showed a similar 3-year distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) between the 2 groups (77.0% in the observation group and 74.9% in the CLND group, p=0.87). Three-year OS and recurrence-free survival (RFS) were likewise similar. Furthermore, although the observation group had no serious adverse events, 14% of the CLND group suffered from grade 3 or 4 events. Therefore, the authors concluded that CLND can be omitted in these patients; but as 66% of the cohort had only up to 1 mm micrometastases in the sentinel lymph node, the authors limited their recommendations to such patients.143

The second such trial was the MSLT-II trial, which also randomized patients with a positive SLNB (including micrometastatic disease identified with molecular techniques) to CLND or observation with serial nodal US. Intention-to-treat analysis results were similar to those of the DeCOG-SLT trial, with comparable 3-year MSS of 86% in both groups. The authors noted that CLND conferred a favorable DFS, related to an improved rate of disease control in the regional nodes, but lymphedema rates were considerably higher in the CLND arm (24.1% vs 6.3%). The authors concluded that although CLND improves regional control and provides additional staging information, it comes at the cost of an increased lymphedema rate, and confers no benefit in MSS. Therefore, observation with serial nodal US in SLNB-positive patients is a safe option for patients who can reliably undergo such surveillance. One caveat to these findings is that CLND identified additional positive nodes in 11.5% of patients, a finding that was a strong predictor of recurrence. This subset of patients derives benefit from CLND.144 The results of these 2 trials led to the overwhelming acceptance by both the NCCN and American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)/Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO) of observation as an acceptable treatment option for low-risk patients with a positive SLNB.105, 141 Patients potentially excluded from these recommendations are those with what can be considered as high-risk features, such as extracapsular extension of their lymph node metastases, significant tumor burden in the sentinel lymph node exceeding 10 mm, microsatellitosis of the primary tumor, more than 3 involved nodes, more than 2 involved nodal basins, and patients on immunosuppression.

Adjuvant Therapy

Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment in early-stage cutaneous melanoma. However, patients with stage IIA through IIC disease are noted to have a 10-year MSS of 88% to 75%. In comparison, stage IIIA melanoma has a 10-year MSS of 88%, and stage IIIB a 77% MSS.64 With the tremendous effect that the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors and BRAF-directed therapy has had on the treatment paradigms and outcomes of metastatic melanoma and stage III disease, the role of these novel agents in the adjuvant setting for stage II melanoma is being investigated.145–148 Several RCTs are currently investigating this question. The largest is KEYNOTE-716 (Safety and Efficacy of Pembrolizumab Compared to Placebo in Resected High-Risk Stage II Melanoma), an international, randomized, phase III trial testing the efficacy of 1 year of pembrolizumab in stage IIB and IIC patients.97, 149

Gene Expression Profiling in Melanoma

In recent years, several commercial GEP tests have become available. Much like the genomic assays for breast cancer, they aim to differentiate low clinical risk patients into low and high genomic risk patients, helping to more accurately discern these patients’ actual risk of recurrence and using that information to guide treatment and surveillance recommendations. The 2 available GEP tests are the 31-gene expression profile DecisionDx-Melanoma™ (Castle Biosciences; TX, USA), which is the most commonly available assay in the United States, and the 8-gene expression profile MelaGenix (NelaCare; Koln, Germany). There are several other GEPs which are still in clinical development.

The DecisionDx-Melanoma uses 28 signature genes and 3 control genes to classify tumors into low-risk (class 1) or high-risk (class 2) for recurrence, with a sub-classification into A and B subgroups.150 Several studies have demonstrated the association between a class 2(B) score and worse RFS and DMFS, compared to a class 1(A) score.151–154 This association has been shown to be statistically significant and independent of the traditional clinical variables of Breslow thickness, ulceration, mitotic rate, and SLNB status. One trial has gone further and shown an association between DecisionDx score and SLNB-positivity, showing 55 to 64 and ≥65-year-old patients with a class 1A score to have 4.9% and 1.6% rate of SLNB-positivity, respectively, and class 2B patients to have 30.8% and 11.9% SLNB-positivity, respectively. These findings point to the potential of GEPs to affect treatment decisions, identifying patients in which SLNB might be avoided or recommended.155

In spite of these early findings, the NCCN and the American Academy of Dermatology discourage the use of any GEP outside of a clinical trial.58, 105 Nevertheless, an estimated of 5% to 10% of cutaneous melanomas are already being subjected to GEP testing.150 One survey shows that more than 20% of “pigmented-lesion experts” are using one of the GEPs, with 63% indicating that their management of patients is affected by the results.156 Questioning this premature use of GEPs, a meta-analysis conducted by Marchetti and colleagues157 points to the limited ability of both DecisionDx-Melanoma and MelaGenix to predict recurrence in localized, stage I and II melanoma. It demonstrates that the GEPs were able to accurately classify patients with recurrence in 76% to 82% of stage II and only 29% to 32% of stage I cases.157 Another criticism regards the clinical application of some of these recent findings regarding DecisionDx, emphasizing the low sensitivity and positive predictive value of the test for T1 disease, resulting in only 1% of T1 patients potentially benefiting from the test, while 13% will be falsely identified as either low- or high-risk.92 Many authorities further question the clinical implication of GEP results, even for accurately identified high-risk patients, pointing to the limitation of diagnostic imaging in detecting pre-symptomatic recurrence, the unproven benefit of treating an asymptomatic recurrence, and the lack of evidence regarding benefit of adjuvant systemic treatment in these patients.

Nevertheless, with time and further research, these assays have the potential to help identify the 2% of T1a patients who will relapse and die of their disease, as well as the 5% of patients with a negative SLNB who will experience a recurrence. They might eventually assist in management decisions regarding these patients, allowing for escalation or de-escalation of treatment according the GEP score, guiding wider or narrower margins for excision, deciding upon the necessity of SLNB, as well as informing decisions concerning adjuvant systemic treatments and patient surveillance.

In summary, there have been great advances in the surgical treatment of early-stage melanoma in recent decades. There has been considerable de-escalation both in the extent of surgery for the primary tumor, with the narrowing of recommended resection margins, as well as in the extent of surgery of the lymphatic basin, with the introduction of SLNB and the selective omission of CLND from a subset of lymph node positive patients. Recommendations continue to evolve as further subsets of patients are identified whose risk for recurrence calls for more or less aggressive surgical and/or systemic therapy. Promising adjuncts to this process include the emerging GEP tests, as well as tumor molecular testing. By characterizing tumors on the molecular level, we might be able to better identify patients who will benefit from further escalation or de-escalation of treatment, as well as to assign targeted therapies to selected patients.

TREATMENT OF REGIONALLY ADVANCED MELANOMA

The hallmark of stage III melanoma is nodal involvement. Previously divided into 3 groups, the 8th edition of the AJCC staging for melanoma now classifies stage III melanoma into 4 subsets (IIIA, IIIB, IIIC, and IIID) based on histopathologic factors: the nodal involvement (number of nodes and microscopic versus macroscopic disease) and tumor characteristics (depth and the presence of ulceration).99 Stage III disease represents a heterogeneous group of patients with regional microscopic or macroscopic nodal disease with or without in-transit or satellite metastasis. As a result of this marked heterogeneity of disease, the outcomes also encompass a wide range of DSS, from 88% 10-year DSS in stage IIIA to 24% for stage IIID disease.64 Stage III subcategorization introduced by the AJCC 8th edition now allows for more accurate evaluation of outcomes and prognosis for patients with stage III disease. Appropriate risk stratification is essential, because patients with macroscopic nodal disease had very poor outcomes prior to the introduction of modern systemic therapy. For example, these patients previously had a greater than 70% chance of recurrence or death at 5 years, and a 9% 5-year OS rate.101, 115, 158

Stage IIIA encompasses non-ulcerated tumors less than 2 mm thick or ulcerated tumors less than 1 mm thick, with microscopic nodal disease in 3 or fewer lymph nodes. Stage IIIB disease includes non-ulcerated tumors less than 4 mm thick, ulcerated tumors less than 2 mm thick with nodal disease in 3 or fewer lymph nodes with at least 1 clinically palpable node, or satellite or in-transit tumors. Stage IIIC disease is comprised of non-ulcerated tumors less than 4 mm thick or ulcerated tumors less than 4 mm thick with either: in-transit disease plus microscopic nodal disease, microscopic nodal disease in 4 or more nodes, 2 or more palpable lymph nodes, or clumped lymph nodes. Stage IIID disease involves ulcerated tumors greater than 4 mm thick with lymph node involvement in more than 3 nodes, clumped lymph nodes, palpable lymphatic disease in 2 or more nodes, or nodal disease plus in-transit disease.

Therapeutic Lymph Node Dissection

The 8th edition of the AJCC staging breaks down lymph nodes into microscopic and macroscopic (ie, occult versus clinically detectible). This distinction is important since the management of the 2 entities is diverging. Although it was previously believed that CLND improved survival and outcomes for all node positive patients, more recent studies have shown that in the setting of microscopic disease there is no survival benefit to CLND.143, 144 However, those patients with high-risk features such as primary tumor microsatellitosis, extracapsular extension, greater than 2 lymph node basins involved, and greater than 3 involved nodes, potentially should be considered for CLND to help with locoregional disease control.141 In summary, CLND may be used selectively based on risk stratification in patients with micrometastatic disease.