Abstract

Objective:

Nonadherence to medications can lead to adverse health outcomes. Alcohol consumption has been shown to be associated with nonadherence to antiretroviral medications, but this relationship has not been examined at different drinking levels or with other chronic disease medications. We conducted a narrative synthesis of the association of alcohol consumption with nonadherence to medications for four chronic diseases.

Method:

We searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science for relevant studies published through 2009. To be included in this analysis, studies had to be quantitative; have a sample size of 50 or greater; and examine the effect of alcohol consumption on medication adherence for diabetes, hypertension, depression, or HIV/AIDS. Study characteristics and results were abstracted according to pre-specified criteria, and study quality was assessed. Study heterogeneity prevented a systematic synthesis.

Results:

Sixty eligible studies addressed medication adherence for HIV in 47 (78%), diabetes in 6 (10%), hypertension in 2 (3%), both diabetes and hypertension in 1 (2%), depression in 2 (3%), and all medications in 2 (3%). Mean number of subjects was 245 (range: 57–61,511). Effect sizes for the association of alcohol use with nonadherence varied (0.76–4.76). Six of the seven highest quality studies reported significant effect sizes (p < .05), ranging from 1.43 to 3.6. Most (67%) studies reporting multivariate analyses, but only half of non-HIV medicine studies, reported significant associations.

Conclusions:

Most studies reported negative effects of alcohol consumption on adherence, but evidence among non-HIV studies was less consistent. These data suggest the relevance of addressing alcohol use in improving antiretroviral adherence and a need for further rigorous study in non-HIV chronic diseases.

Patients with chronic diseases commonly miss doses of their medications (Cantrell et al., 2011; DiMatteo, 2004). Poor medication adherence often leads to substantial unfavorable health outcomes (Kripalani et al., 2007; Osterberg and Blaschke, 2005). Recognizing common mutable factors that influence medication adherence, such as patient behaviors, has important clinical implications. Nationally, alcohol consumption is highly prevalent; in 2009, 52% of adults reported regular use (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009) and 15% reported heavy episodic drinking (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). The exact mechanisms by which alcohol consumption could affect adherence are not fully known but may include forgetting to take doses because of intoxication and purposely skipping doses to avoid interactions of medications with alcohol (Cook et al., 2001; Kalichman et al., 2009). However, clinicians often do not detect, treat (McGlynn et al., 2003; Turner, 2009), or even consider problem drinking when helping their patients adhere to medication regimens (Hendershot et al., 2009).

In a meta-analysis of the association of alcohol consumption with adherence to antiretroviral therapy, alcohol users were 55% less likely to adhere to HIV medication regimens than abstainers or persons who drank relatively less (Hendershot et al., 2009). Another review found evidence to support the negative impact of alcohol use disorders on adherence to HIV therapy and HIV treatment outcomes (Azar et al., 2010). However, neither review examined the effects of different levels of alcohol consumption on HIV medication adherence, nor did they examine this relationship among populations taking medications for other chronic diseases. The near-perfect adherence required by HIV medication regimens as well as the higher prevalence of problem drinking among HIV-infected patients make it difficult to generalize from these findings to adherence to medications for other diseases, where medications are more forgiving and hence requirements for adherence are less strict.

In this systematic narrative review, we extend the evaluation of the effect of alcohol consumption on medication adherence beyond a focus on HIV to consider whether similar effects appear among persons taking medications for diabetes, hypertension, and depression. We focused on these four diseases because they represent common chronic conditions with the largest body of literature examining the relationship between alcohol use and medication adherence. We also examined studies in the HIV literature to determine whether different levels of alcohol consumption may demonstrate a dose-response association with medication adherence. Finally, we sought to determine whether higher quality studies conducted across diseases supported an association of alcohol consumption with medication adherence.

Method

Search strategy

To identify eligible peer-reviewed publications, we searched four databases (Medline, PsycINFO, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science) for articles published through 2009 containing specific subject headings and text words (shown in Table 1 for Medline) with the assistance of a medical librarian. Publications were restricted to journal articles, clinical trials, meta-analyses, multicenter studies, and reviews. We reviewed bibliographies of each study included for full text review to identify additional articles.

Table 1.

Specific concepts, medical subject heading (MeSH) terms, and text words in Medline, used to identify articles on alcohol and adherence

| Concept | MeSH terms | Text words |

| Alcohol consumption | Ethanol, alcohol drinking, alcoholism | Alcohol, alcohol drinking, alcoholism |

| Medication adherence | Patient compliance | Patient compliance, adherence, nonadherence |

| Diabetes | Diabetes mellitus | Diabetes |

| Depression | Depressive disorder, depression | Antidepressant |

| Hypertension | Hypertension | Hypertension |

| HIV/AIDS | AIDS | HIV |

Inclusion criteria

Three reviewers developed inclusion criteria and guidelines for data coding and abstraction. Eligible studies met four criteria: the reports (a) were quantitative research studies; (b) had sample sizes of 50 or more adults; (c) addressed adherence to medications for diabetes, hypertension, depression, and/or HIV/AIDS; and (d) examined the association of alcohol consumption with medication adherence in either primary or secondary analyses. We excluded studies in acute care settings to focus on long-term medication adherence.

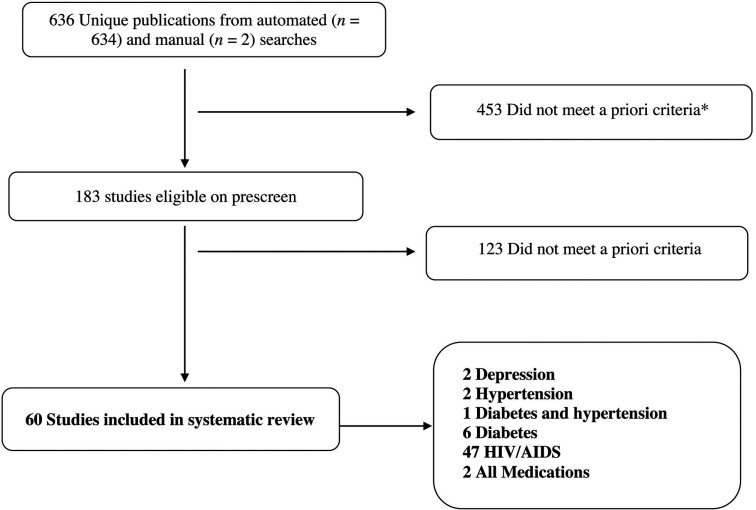

One reviewer examined all abstracts identified by the initial database search to evaluate eligibility. When inclusion criteria could not be assessed from the abstract, the full article was reviewed by one of four reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by group discussion. Overall, we identified 60 eligible articles for the review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Identified studies of alcohol consumption and adherence to medication for four chronic diseases. *A priori inclusion criteria included (a) quantitative research study; (b) sample size of 50 or more adults; (c) addressed adherence to medications for diabetes, hypertension, depression, or HIV/AIDS; and (d) examined the association of alcohol consumption with medication adherence in either primary or secondary analyses. We excluded studies in acute care settings including emergency room or inpatient hospital.

Data extraction

Eligible studies were independently coded for methods of measuring alcohol use and medication adherence and descriptive characteristics of the analytic sample, including sample size, chronic disease, proportion of women, study setting, and other unique characteristics. Data on the prevalence of alcohol consumption and poor adherence were extracted as well as findings regarding the association of alcohol consumption with adherence. Coding consistency was 95% based on three reviewers’ assessments of the same 10% random sample of identified articles.

Classification of alcohol and adherence measures

Reviewers categorized the definition of alcohol consumption within each article, influenced by guidelines set forth by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), as heavy episodic drinking (defined as 5 or more drinks for men and 4 or more drinks for women within 2 hours), problem drinking (15 or more drinks per week or 5 or more drinks per day for men and 8 or more drinks per week or 4 or more drinks per day for women), or moderate drinking (up to 2 drinks per day for men and up to 1 drink per day for women) (NIAAA, 2005). When the amount or pattern of alcohol consumed was not specified, it was considered any use. Some studies reported specific quantities of alcohol consumption using either continuous or ordinal measures, and others reported scale scores; these we classified as continuous or ordinal as appropriate based on the definitions in the study. Measures were also classified according to the recall period used for alcohol use measurement.

The method that was used to measure medication adherence was considered objective if medication event monitoring system (MEMS) caps, pill counts, or pharmacy records were used or subjective if only self-report or provider report was used. Measures were also classified based on the period for which adherence was assessed.

Quality of evidence

Most evidence came from nonexperimental studies; therefore, we assessed methodological quality using appraisal criteria adapted from the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale as recommended by the Cochrane Non-Randomized Studies Methods Working Group (Reeves et al., 2008; Wells et al., 1999). We included six quality indices and assigned 1 or 2 points (maximum of 10 points possible) for each of the following: (a) representativeness of study sample (1 point), (b) alcohol consumption measured by a validated instrument (2 points), (c) medication adherence measured by a validated self-report instrument (1 point) or objective measures (2 points), (d) longitudinal study design and follow-up rate (2 points), (e) use of imputation or dummy variables to address missing data (1 point), and (f) adjustment for potential confounders (2 points). To develop consistency in rating quality, we compared our ratings for 15 (25%) studies and resolved differences. For reporting purposes, we defined the highest quality studies as those in the top 40th percentile (scoring at least 6 of 10 points).

Analysis

All unadjusted associations and, when available, effect sizes with confidence limits were examined among all studies and among those studies assigned the highest quality rating, conducting a dose-response analysis, and examining each chronic disease type. When necessary, we calculated the reciprocal of the odds ratios (OR) to reflect the association of alcohol with poorer rather than better adherence. We examined associations separately for studies conducting adjusted analyses. Because of the heterogeneity of study samples, measures, and analyses in this review, these results could not be pooled statistically.

Results

Study designs and quality

Of 60 eligible studies, most (75%) were conducted in the United States; international settings included Switzerland, France, Italy, Hungary, China, Brazil, and Ethiopia. The mean sample size was 245 and ranged from 57 to 61,511. Thirteen (22%) studies had more than 1,000 study subjects. Study settings included specialty (e.g., HIV; n = 29) and primary (n = 5) clinics, community-based practices (n = 14), multiple healthcare settings (n = 6), Veterans Affairs facilities (n = 6), substance use treatment centers (n = 3), a large health plan (n = 2), and a public health referral center (n = 1). The primary research question addressed the association of alcohol consumption with medication adherence in 21 (35%) studies, and 17 (28%) examined the association longitudinally.

Measures of adherence and alcohol consumption

Medication adherence.

Measures of medication adherence (Table 2) varied widely; 10 studies (17%) used at least one objective measure, and 16 (27%) used the self-reported Adherence Questionnaire developed by the AIDS Clinical Trial Group (Chesney et al., 2000). Most studies (n = 37) defined adherence as the proportion of prescribed pills or doses taken over a specified timeframe; more than half (n = 21) compared 100% adherence with other levels. Most studies (n = 38) assessed adherence over a 1-month timeframe, whereas a small subset (n = 11) examined a continuous measure.

Table 2.

Self-report and objective measures of alcohol use and medication adherence

| Variable | n (% of reported measures) |

| Studies reporting alcohol measure | 18(100) |

| AUDIT and AUDIT-C (Saunders et al., 1993) | 6(33) |

| Addiction Severity Index (McLellan et al., 1980) | 4(22) |

| Timeline Followback (Sobell and Sobell, 1992) | 3(17) |

| DrInC (Miller et al., 1995) | 1(6) |

| CAGE (Mayfield et al., 1974) | 1(6) |

| DSM-IV (Millon et al., 1996) | 1(6) |

| Alcohol Use Self-Report (Cox et al., 1996) | 1(6) |

| Lifetime Drinking History (Skinner, 1979) | 1(6) |

| Client Diagnostic Questionnaire (Aidala et al., 2004) | 1(6) |

| Studies reporting self-report or objective adherence measure | 36(100) |

| Objective measures | 10(28) |

| Pharmacy records | 4(11) |

| MEMS | 7(19) |

| Composite of MEMS, pill count, and self-report | 1(3) |

| Self-report measures | 26(72) |

| ACTG (Chesney et al., 2000) | 16(44) |

| Timeline Followback modified for adherence (Braithwaite et al., 2005) | 4(11) |

| Swiss HIV Cohort Study (Conen et al., 2009) | 1(3) |

| Adaptation of HCSUS and RAND measures (Friedman et al., 2009) | 1(3) |

| Antiretroviral General Adherence Scale (McDonnell Holstad et al., 2006) | 1(3) |

| Diabetes Self-Care Questionnaire (Johnson et al., 2000) | 1(3) |

| Hill-Bone Adherence to High Blood Pressure Therapy Medication Subscale (Kim et al., 2003) | 1(3) |

| Self-Care Inventory (Lerman et al., 2004) | 1(3) |

Notes: AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; AUDIT-C = AUDIT–consumption questions; DrInC = drinker inventory of consequences; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; MEMS = medication event monitoring system; ACTG = AIDS Clinical Trials Group; HCSUS = HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study.

Alcohol consumption.

All studies measured alcohol consumption by self-report, and one also used a breath alcohol analyzer to assess truthfulness (Samet et al., 2004). As shown in Table 2, the most commonly used validated measures were the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and AUDIT–consumption questions (AUDIT-C) (n = 6) (Saunders et al., 1993). Most studies examined a 1-month timeframe to assess alcohol consumption (n = 17), although timeframes ranged from 2 weeks to lifetime use. Categorization of alcohol use patterns ranged from any use to dependence. Ten studies examined a continuous indicator of alcohol consumption.

Association between alcohol consumption and adherence for all studies

A statistically significant negative association between alcohol use and medication adherence was reported by 36 (60%) of all 60 studies and by 33 (67%) of the 49 studies conducting multivariate analyses (Table 3). The reported effect sizes ranged from ORs of 0.76 to 4.76 for all 60 studies, from 1.07 to 4.76 for those 36 studies that found a significant association, and from 0.76 to 3.35 of those that found a null association. A descriptive table listing characteristics of all studies is available from the authors on request.

Table 3.

Overall and multivariate significant findings by disease

| Overall |

Multivariate |

|||||

| Variable | Total studies, n | Studies with significant associations, n (%) | Reported effect sizes (OR) | Total studies, n | Studies with significant associations, n (%) | Reported effect sizes (aOR) |

| All studies | 60 | 36 (60) | 0.76–4.76 | 49 | 33 (67) | 0.76–4.76 |

| HIV | 47 | 31 (62) | 0.76–4.76 | 38 | 27 (71) | 0.76–4.76 |

| Diabetes | 7 | 3 (43) | 2.50 | 4 | 2 (50) | 2.50 |

| Hypertension | 3 | 1 (33) | N-R | 3 | 1 (33) | N-R |

| Depression | 2 | 1 (50) | 2.04 | 1 | 1 (100) | 2.04 |

| All medications | 2 | 2 (100) | 1.5, 4.1 | 2 | 2 (100) | 1.5, 4.1 |

Notes: OR = odds ratio; aOR = adjusted odds ratio; N-R = not reported.

High-quality studies

Of the seven studies assigned the highest quality ratings (Applebaum et al., 2009; Bryson et al., 2008; Golin et al., 2002; Howard et al., 2002; Kilbourne et al., 2005; Peretti-Watel et al., 2006; Samet et al., 2004), six (86%) reported a statistically significant negative association between alcohol consumption and adherence. Five of the seven high-quality studies assessed adherence only to HIV medications, all of which reported significant effects. Peretti-Watel et al. (2006) examined heavy episodic drinking (more than five drinks in a row at least twice a month during the past year) and found a significant relationship between poor adherence and heavy episodic drinking (“binges”) that occurred two or more times per month versus less often (OR = 1.43, 95% CI [1.02, 2.01] (Peretti-Watel et al., 2006). Samet et al. (2004) similarly found that those engaged in “at-risk” drinking (>14 drinks per week or >4 per day for men; >7 drinks per week or >3 per day for women) were less likely to report 100% adherence than those who abstained from alcohol in the past 30 days (OR = 3.6, CI [2.1, 6.2]) (Samet et al., 2004). Three HIV studies did not report effect sizes but found significant associations for alcohol dependence versus no dependence (definition and timeframe not reported) (Applebaum et al., 2009); any versus no alcohol use in the past 30 days (Golin et al., 2002); and use more than 1 day per week in the past 6 months versus less (Howard et al., 2002).

In one study of 30-day adherence to diabetes medication that conducted adjusted analyses, the odds of nonadherence were higher for heavy episodic drinkers (having six or more drinks on one occasion) versus those not engaging in this type of drinking behavior (OR 2.5, CI [0.83, 5.00]) but did not achieve statistical significance (Kilbourne et al., 2005). Another study of adherence to both antihypertensive and diabetes medications in the past 90 days and 1 year reported significant negative associations of mild, moderate, and severe alcohol misuse (defined by AUDIT-C scores of 4–5, 6–7, and 8–12, respectively) versus abstainers (AUDIT-C score of 0) only for antihypertensive adherence but not for diabetes medication adherence (no effect sizes reported) (Bryson et al., 2008).

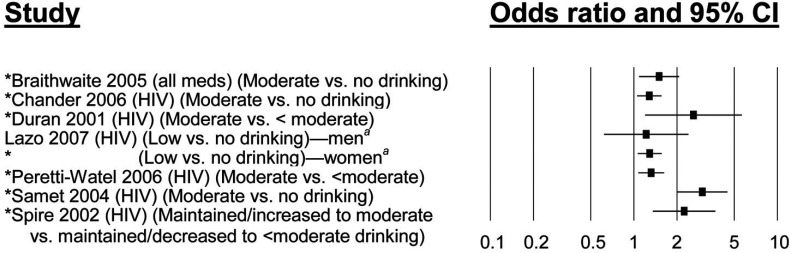

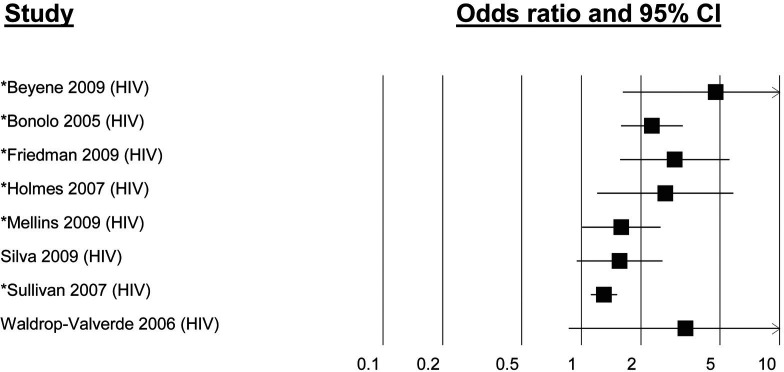

Relationship between alcohol intake and poor adherence by level of alcohol consumption

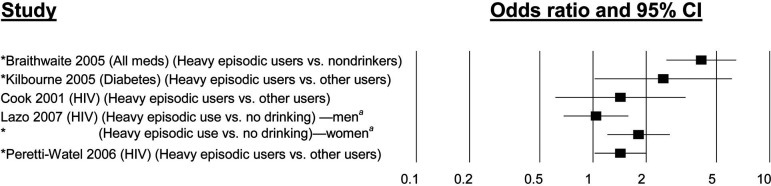

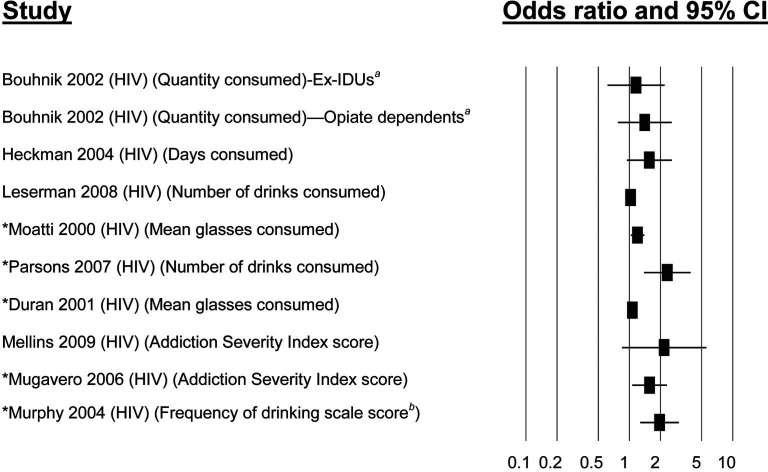

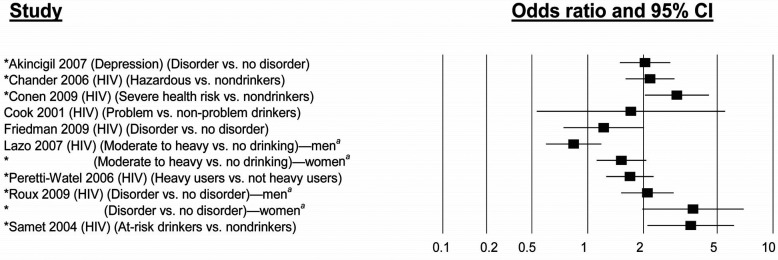

Multivariate effect sizes by level of alcohol consumption are shown in Figures 2a–2e for those articles that reported effect sizes. The relationship between heavy episodic drinking and medication adherence was examined in five studies using multivariate analyses (Figure 2a), four of which found a significant relationship with ORs ranging from 1.43 to 4.1. Problem alcohol use was examined in nine multivariate analyses (Figure 2b), seven of which had significant findings; ORs ranged from 1.52 (CI [1.11, 2.07]) to 3.7 (CI [2.0, 7.1]). All seven multivariate studies of moderate drinking found a significant relationship with medication adherence, with ORs ranging from 1.29 (CI [1.06, 1.57]) to 3.0 (CI [2.0, 4.5]) (Figure 2c). Studies using measures of any alcohol use had less consistent findings: six of eight studies of any alcohol use (OR = 1.3, CI [1.1, 1.5], to OR = 4.76, CI [1.62, 14.08]) (Figure 2d) had significant findings. Even less consistent were the nine studies measuring alcohol consumption as a continuous or count variable, of which five (OR = 1.07, CI [1.03, 1.11], to OR = 2.33, CI [1.35, 3.85]) (Figure 2e) had significant findings.

Figure 2A.

Association of heavy episodic drinking with medication nonadherence. aData only available by subgroup and not for entire study sample. CI = confidence interval. *p < .05.

Figure 2E.

Alcohol use measured as continuous, count, or ordinal variable and association with medication nonadherence. aData only available by subgroup and not for entire study sample; bfrequency of drinking scale scores: 1 = 0 times in past 3 months, 2 = ≤1/month, 3 = ≥1/month but <1/week, 4 = ≥1/week but <1/day, 5 = every day. CI = confidence interval; ex-IDUs = patients with a history of injection drug use but no use during the study period. *p < .05.

Figure 2B.

Association of problem alcohol use with medication nonadherence. aData only available by subgroup and not for entire study sample. CI = confidence interval. *p < .05.

Figure 2C.

Association of moderate alcohol use with medication nonadherence. Unless otherwise specified, moderate drinking is defined as drinking at levels less than hazardous drinking defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. aData only available by subgroup and not for entire study sample. CI = confidence interval. *p < .05.

Figure 2D.

Association of any alcohol use with medication nonadherence. All analyses compared any alcohol consumption with no alcohol consumption. CI = confidence interval. *p < .05.

Relationship between alcohol intake and poor adherence by disease type

Adherence to HIV medications.

Of 47 studies addressing adherence to HIV medications (Applebaum et al., 2009; Arnsten et al., 2002; Berg et al., 2004; Beyene et al., 2009; Bonolo et al., 2005; Bouhnik et al., 2002; Campos et al., 2010; Chander et al., 2006; Chesney et al., 2000; Cohn et al., 2008; Cook et al., 2001; de Jong et al., 2005; Duran et al., 2001a, 2001b; Friedman et al., 2009; Golin et al., 2002; Halkitis et al., 2003, 2005; Heckman et al., 2004; Holmes et al., 2007; Howard et al., 2002; Ingersoll, 2004; Johnson et al., 2003; Lazo et al., 2007; Leserman et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2006; Martini et al., 2004; McDonnell Holstad et al., 2006; Mellins et al., 2009; Moatti et al., 2000; Mugavero et al., 2006; Murphy et al., 2004; Parsons et al., 2007; Peretti-Watel et al., 2006; Protopopescu et al., 2009; Rothlind et al., 2005; Roux et al., 2009; Safren et al., 2001; Samet et al., 2004; Silva et al., 2009; Spire et al., 2002; Sullivan et al., 2007; Theall et al., 2007; Waldrop-Valverde and Valverde, 2005; Waldrop-Valverde et al., 2006; Wang and Wu, 2007), 38 conducted multivariate analyses and, of these, 27 (71%) reported statistically significant associations of poor adherence with alcohol consumption (range in reported effect sizes: 0.76–4.76). Among studies of specific patterns of alcohol use, significantly poorer adherence (ORs) was reported by 9 of 12 studies of problem drinking (1.22–3.70); 2 of 3 studies of heavy episodic drinking (1.43–1.8), of which one found an effect only in women; 8 of 11 studies of moderate alcohol consumption (1.28–3.0); 8 of 14 studies of any alcohol consumption (1.3–4.76); and 6 of 11 studies using continuous or ordinal measures of alcohol consumption (1.03–2.33).

Adherence to diabetes medications.

Of seven studies of adherence to diabetes medications, just one reported significant findings in multivariate analysis, with significantly poorer adherence among those consuming 2–2.9 drinks per day versus abstaining (Ahmed et al., 2006). In two unadjusted studies, heavy drinkers were significantly less adherent than light drinkers and abstainers (Cox et al., 1996), whereas persons who drink any alcohol were less adherent to insulin than abstainers, but no effect was observed for oral agents (Johnson et al., 2000). In three studies performing adjusted analyses and one unadjusted study, none of the measures of alcohol use were associated with diabetes medication adherence (Bryson et al., 2008; Hankó et al., 2007; Kilbourne et al., 2005; Lerman et al., 2004).

Adherence to antihypertensive medications.

All three studies of adherence to antihypertensive medication performed multivariate analyses but did not report effect sizes. (Bryson et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2002). One reported a significant association between poor adherence and alcohol misuse (categorized as mild, moderate, or severe misuse) versus no use (Bryson et al., 2008).

Adherence to antidepressant medications.

Two studies examined adherence to antidepressant medications, and one reported a significant adjusted association with alcohol use disorder (OR = 2.04, CI [1.42, 2.77]) (Akincigil et al., 2007). The second study reported no association but conducted only an unadjusted analysis of a lifetime history of an alcohol disorder versus all others (Baca-Garcia et al., 2009).

Adherence to all medications.

Two studies conducted by the same research group reported statistically significant adjusted associations of alcohol consumption with poor adherence to all types of medications taken by more than 2,700 (HIV-negative and matched HIV-positive) subjects in the multisite Veterans Aging Cohort Study (Braithwaite et al., 2005, 2008). In one study, heavy episodic drinkers (those who consumed ≥5 drinks within 1 day during the past 30 days) were over four times more likely to be poorly adherent (OR = 4.1, CI [2.6, 5.6]) versus abstainers, whereas drinkers not engaging in heavy episodic use were somewhat more likely to be poorly adherent than abstainers (OR = 1.5, CI [1.1, 2.1]) (Braithwaite et al., 2005). Although the association between heavy episodic drinking and adherence was slightly stronger among HIV-infected individuals than HIV-negative people, the effect size was large in both groups (OR = 4.3 vs. 3.3, respectively) (Braithwaite et al., 2005). In the second study, adherence was significantly poorer on days when individuals drank: 6 or more versus 0.5 or fewer drinks, more than his or her average amount, to impairment, or hazardously (effect sizes not reported) (Braithwaite et al., 2008).

Dose-response studies

Three studies examined and demonstrated a temporal dose-response relationship of alcohol consumption with medication adherence (Braithwaite et al., 2005, 2008; Bryson et al., 2008). Braithwaite et al. used Timeline Followback methods to assess whether alcohol consumption on a particular day was associated with poor adherence to prescribed medications on the same day (Braithwaite et al., 2005). Missing doses of any medication on surveyed days showed a significant trend (p < .001) in which abstainers missed 2.4% of doses whereas drinkers not engaging in heavy episodic use missed 3.5% on drinking days, 3.1% on postdrinking days, and 2.1% on nondrinking days. Heavy episodic drinkers (defined previously) missed doses on 11.0% of drinking days, 7.0% of postdrinking days, and 4.1% of nondrinking days (p < .001 for trend). In the same cohort (Braithwaite et al., 2008), consideration of an individual’s threshold for cognitive impairment from alcohol consumption improved prediction of poor adherence.

Bryson et al. (2008) investigated a dose-response relationship of alcohol intake and poor adherence using pharmacy refill data for more than 13,000 patients taking antihypertensive and/or diabetes medication. The AUDIT-C score was linearly associated with poorer adherence to antihypertensive drugs but not with adherence to diabetes medications.

Discussion

Optimizing patients’ adherence to medications has great public health importance. Previous studies have reported that patients with chronic diseases often do not adhere to prescribed medications, leading to poor health outcomes (Kripalani et al., 2007; Osterberg and Blaschke, 2005). In one meta-analysis, only 60% of patients with chronic diseases took all their prescribed doses (Cantrell et al., 2011; DiMatteo, 2004). Because alcohol consumption is quite common, its potential negative effects on medication adherence may significantly compromise chronic disease management and outcomes. Most of the research on this topic has been conducted in HIV-infected patients, but it is quite plausible that patterns observed for HIV medication adherence are similar to those for adherence to medications used for much more common diseases.

Our synthesis of HIV medication adherence research shows a relatively consistent negative association of alcohol consumption with medication adherence as reported in other systematic reviews of this topic (Azar et al., 2010; Hendershot et al., 2009). However, our study is the first to conduct an assessment of study quality, which finds that the most rigorously conducted studies show a significant inverse relationship of greater alcohol use with HIV medication adherence. This effect was stronger for greater levels of alcohol consumption but also appeared to exist for any use. Only two studies conducted by the same group evaluated the alcohol-adherence relationship in both HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected veterans (Braithwaite et al., 2005, 2008). This research showed a stronger dose-response relationship for HIV-infected patients, but heavy episodic drinking showed a strong negative association in both HIV-infected and HIV-negative subjects.

The studies of the association of alcohol consumption with adherence to medications for non-HIV-related chronic conditions generally suffered from poorer quality. Of the eight studies examining exclusively non-HIV medications that conducted adjusted analyses, only four reported a significant association. The largest number of non-HIV studies examined adherence to medications for diabetes. Of seven studies identified as being high quality in our review, six found a significant association between alcohol and adherence but only two examined adherence to non-HIV medications. One high-quality study of adherence to diabetes medications reported a significant association with heavy episodic drinking, but neither study examining antihypertensives showed significant findings.

The stronger association of alcohol use with medication adherence among HIV-positive patients could be attributed to the relative complexity of HIV medication regimens. Increased regimen complexity has been demonstrated to negatively affect adherence to medications for chronic diseases, particularly HIV/AIDS, diabetes, and hypertension (with insufficient literature conducted on this relationship in the area of hypertension) (Ingersoll and Cohen, 2008). Although currently many HIV regimens consist of only one daily dose, they have decreased in complexity relatively recently; in 2007, participants in HIV medication trials took more medications on average than those in other chronic disease medication trials (Gossec et al., 2007). It is possible that alcohol use may have a more detrimental effect on adherence to more complex regimens such as those for HIV.

Additionally, the stronger association between alcohol use and HIV medication adherence could be attributed to characteristics of the different patient populations. Heavy alcohol consumption is more prevalent among HIV-infected patients than the general population (Galvan et al., 2002); further, HIV-infected patients are generally younger than most patients with diabetes and hypertension, and the prevalence of heavy alcohol consumption decreases with older age (Eigenbrodt et al., 2001). It is also possible that the same level of alcohol use may lead to greater cognitive impairment among HIV-infected persons (Rothlind et al., 2005). Furthermore, not all studies adjust for mood disorders such as depression, another possible mechanism by which alcohol consumption could negatively affect adherence, especially in persons with HIV infection (Grenard et al., 2011).

Our findings also suggest that lower levels of alcohol use may influence adherence by a different mechanism than that of heavier use, such as heavy episodic or problem drinking. For example, in the national Nurses’ Health Study, consumption of one alcoholic beverage daily did not impair cognition and may have even improved it (Stampfer et al., 2005). People who drink may be more likely to simply forget to take medications or may worry about drug interactions. Alternatively, measurement bias could result in an overestimate of the association of lower levels of alcohol use as a result of the well-known tendency of individuals to underestimate their alcohol use (Klatsky el al., 2006). Studies examining “any drinking” versus all others have distorted results by including heavy drinkers with persons who drink very little. Further, the reference group may include former heavy drinkers with true abstainers.

This study reinforces the need for more rigorous research on the association of alcohol use with medication adherence among people who are not infected with HIV. Particularly, the near-perfect level of adherence required for HIV medications may mean that the negative effects of alcohol use are more evident for that condition than for others. Further research of adherence to medications for diabetes, hypertension, and depression needs to use validated alcohol measures that assess multiple categories of alcohol consumption (e.g., alcohol dependence as well as heavy episodic drinking, hazardous drinking, and any drinking, such as the AUDIT), as well as objectively measured adherence levels. Where possible, studies should control for potential confounders such as mental illness and conduct dose-response analyses.

Despite the limitations of the current literature, this review draws attention to a potentially important gap in the evidence about alcohol on medication adherence. The potential public health implications of poor adherence to chronic disease medications support the need for more rigorous studies to evaluate this association.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jessica Hopkins, Zulfiya Chariyeva, Chaunetta Jones, and Ross Oglesbee for their assistance in editing and formatting; Meheret Mamo and Robert Michael for their assistance in full text review; and Candi Wines for her assistance with the tables and figures. We also thank Michael Pignone and Dan Jonas for consultation on systematic review methodology.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (CFAR; a National Institutes of Health–funded program [P30 AI50410]) and the Program of Research into Integrating Substance Use into Mainstream Healthcare funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The authors do not have any conflict of interest with the research presented in this article.

References

- Ahmed AT, Karter AJ, Liu J Alcohol consumption is inversely associated with adherence to diabetes self-care behaviours. Diabetic Medicine . 2006;23:795–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aidala A, Havens J, Mellins CA, Dodds S, Whetten K, Martin D, Ko P Development and validation of the Client Diagnostic Questionnaire (CDQ): A mental health screening tool for use in HIV/ AIDS service settings. Psychology, Health & Medicine . 2004;9:362–380. [Google Scholar]

- Akincigil A, Bowblis JR, Levin C, Walkup JT, Jan S, Crystal S Adherence to antidepressant treatment among privately insured patients diagnosed with depression. Medical Care . 2007;45:363–369. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254574.23418.f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum AJ, Richardson MA, Brady SM, Brief DJ, Keane TM Gender and other psychosocial factors as predictors of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in adults with comorbid HIV/AIDS, psychiatric and substance-related disorder. AIDS and Behavior . 2009;13:60–65. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Grant RW, Gourevitch MN, Farzadegan H, Howard AA, Schoenbaum EE Impact of active drug use on antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users. Journal of General Internal Medicine . 2002;17:377–381. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, Altice FL A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug and Alcohol Dependence . 2010;112:178–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca-Garcia E, Sher L, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Burke AK, Sullivan GM, Grunebaum MF, Oquendo MA Treatment of depressed bipolar patients with alcohol use disorders: Plenty of room for improvement. Journal of Affective Disorders . 2009;115:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KM, Demas PA, Howard AA, Schoenbaum EE, Gourevitch MN, Arnsten JH Gender differences in factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Journal of General Internal Medicine . 2004;19:1111–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyene KA, Gedif T, Gebre-Mariam T, Engidawork E Highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence and its determinants in selected hospitals from south and central Ethiopia. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety . 2009;18:1007–1015. doi: 10.1002/pds.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonolo P, de F, César CC, Acúrcio FA, Ceccato M, das GB, de Pádua CAM, Álvares J, Guimarães MDC Non-adherence among patients initiating antiretroviral therapy: A challenge for health professionals in Brazil. AIDS, 19, Supplement . 2005;4:S5–S13. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000191484.84661.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhnik A-D, Chesney M, Carrieri P, Gallais H, Moreau J, Moatti J-P MANIF 2000 Study Group. Nonadherence among HIV-infected injecting drug users: The impact of social instability. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes . 2002;31:S149–S153. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200212153-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite RS, Conigliaro J, McGinnis KA, Maisto SA, Bryant K, Justice AC Adjusting alcohol quantity for mean consumption and intoxication threshold improves prediction of nonadherence in HIV patients and HIV-negative controls. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research . 2008;32:1645–1651. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite RS, McGinnis KA, Conigliaro J, Maisto SA, Crystal S, Day N, Justice AC A temporal and dose-response association between alcohol consumption and medication adherence among veterans in care. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research . 2005;29:1190–1197. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171937.87731.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson CL, Au DH, Sun H, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA Alcohol screening scores and medication nonadherence. Annals of Internal Medicine . 2008;149:795–804. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-11-200812020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos LN, Guimarães MDC, Remien RH Anxiety and depression symptoms as risk factors for non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Brazil. AIDS and Behavior . 2010;14:289–299. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9435-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell CR, Priest JL, Cook CL, Fincham J, Burch SP Adherence to treatment guidelines and therapeutic regimens: A US claims-based benchmark of a commercial population. Population Health Management . 2011;14:33–41. doi: 10.1089/pop.2010.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hyattsville, MD: 2009. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2008. Vital and Health Statistics, Series 10, Number 242 (DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 2010–1570) Author. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_242.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC health disparities and inequalities report—United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60, Supplement . 2011:1–114. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/other/su6001.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chander G, Lau B, Moore RD Hazardous alcohol use: A risk factor for non-adherence and lack of suppression in HIV infection. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes . 2006;43:411–417. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243121.44659.a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, Wu AW & the Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG). Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: The AACTG adherence instruments. AIDS Care: Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV . 2000;12:255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn SE, Umbleja T, Mrus J, Bardeguez AD, Andersen JW, Chesney MA Prior illicit drug use and missed prenatal vitamins predict nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in pregnancy: Adherence analysis A5084. AIDS Patient Care and STDs . 2008;22:29–40. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conen A, Fehr J, Glass TR, Furrer H, Weber R, Vernazza P, Battegay M & the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Self-reported alcohol consumption and its association with adherence and outcome of antiretroviral therapy in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Antiviral Therapy . 2009;14:349–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RL, Sereika SM, Hunt SC, Woodward WC, Erlen JA, Conigliaro J Problem drinking and medication adherence among persons with HIV infection. Journal of General Internal Medicine . 2001;16:83–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Blount JP, Crowe PA, Singh SP Diabetic patients’ alcohol use and quality of life: Relationships with prescribed treatment compliance among older males. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research . 1996;20:327–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong BC, Prentiss D, McFarland W, Machekano R, Israelski DM Marijuana use and its association with adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons with moderate to severe nausea. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes . 2005;38:43–46. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200501010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo MR Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: A quantitative review of 50 years of research. Medical Care . 2004;42:200–209. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran S, Savès M, Spire B, Cailleton V, Sobel A, Carrieri P, Leport C & the APROCO Study Group. Failure to maintain long-term adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: the role of lipodystrophy. AIDS . 2001a;15:2441–2444. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200112070-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran S, Spire B, Raffi F, Walter V, Bouhour D, Journot V, Moatti J-P Self-reported symptoms after initiation of a protease inhibitor in HIV-infected patients and their impact on adherence to HAART. HIV Clinical Trials . 2001b;2:38–45. doi: 10.1310/R8M7-EQ0M-CNPW-39FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigenbrodt ML, Mosley TH, Hutchinson RG, Watson RL, Chambless LE, Szklo M Alcohol consumption with age: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, 1987–1995. American Journal of Epidemiology . 2001;153:1102–1111. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.11.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Stall R, Kidder DP, Henny KD, Courtenay-Quirk C, Holtgrave DR Associations between substance use, sexual risk taking and HIV treatment adherence among homeless people living with HIV. AIDS Care: Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV . 2009;21:692–700. doi: 10.1080/09540120802513709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan FH, Bing EG, Fleishman JA, London AS, Caetano R, Burnam MA, Shapiro M The prevalence of alcohol consumption and heavy drinking among people with HIV in the United States: Results from the HIV cost and services utilization study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol . 2002;63:179–186. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golin CE, Liu H, Hays RD, Miller LG, Beck CK, Ickovics J, Wenger NS A prospective study of predictors of adherence to combination antiretroviral medication. Journal of General Internal Medicine . 2002;17:756–765. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossec L, Tubach F, Dougados M, Ravaud P Reporting of adherence to medication in recent randomized controlled trials of 6 chronic diseases: A systematic literature review. American Journal of the Medical Sciences . 2007;334:248–254. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318068dde8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenard JL, Munjas BA, Adams JL, Suttorp M, Maglione M, McGlynn EA, Gellad WF Depression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic diseases in the United States: A meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine . 2011;26:1175–1182. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1704-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Kutnick AH, Slater S The social realities of adherence to protease inhibitor regimens: Substance use, health care and psychological states. Journal of Health Psychology . 2005;10:545–558. doi: 10.1177/1359105305053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Parsons JT, Wolitski RJ, Remien RH Characteristics of HIV antiretroviral treatments, access and adherence in an ethnically diverse sample of men who have sex with men. AIDS Care . 2003;15:89–102. doi: 10.1080/095401221000039798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankó B, Kázmér M, Kumli P, Hrágyel Z, Samu A, Vincze Z, Zelkó R Self-reported medication and lifestyle adherence in Hungarian patients with Type 2 diabetes. Pharmacy World & Science . 2007;29:58–66. doi: 10.1007/s11096-006-9070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman BD, Catz SL, Heckman TG, Miller JG, Kalichman SC Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in rural persons living with HIV disease in the United States. AIDS Care . 2004;16:219–230. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001641066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, Pantalone DW, Simoni JM Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes . 2009;52:180–202. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b18b6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WC, Bilker WB, Wang H, Chapman J, Gross R HIV/AIDS-specific quality of life and adherence to antiretroviral therapy over time. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes . 2007;46:323–327. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815724fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard AA, Arnsten JH, Lo Y, Vlahov D, Rich JD, Schuman P Schoenbaum, E. E., & the HER Study Group. A prospective study of adherence and viral load in a large multi-center cohort of HIV-infected women. AIDS . 2002;16:2175–2182. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211080-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll K The impact of psychiatric symptoms, drug use, and medication regimen on non-adherence to HIV treatment. AIDS Care . 2004;16:199–211. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001641048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll KS, Cohen J The impact of medication regimen factors on adherence to chronic treatment: A review of literature. Journal of Behavioral Medicine . 2008;31:213–224. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9147-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KH, Bazargan M, Bing EG Alcohol consumption and compliance among inner-city minority patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Archives of Family Medicine . 2000;9:964–970. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MO, Catz SL, Remien RH, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Morin SF, Charlebois E Chesney, M. A., & the NIMH Healthy Living Project Team. Theory-guided, empirically supported avenues for intervention on HIV medication nonadherence: findings from the Healthy Living Project. AIDS Patient Care and STDs . 2003;17:645–656. doi: 10.1089/108729103771928708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, White D, Swetsze C, Pope H, Kalichman MO, Eaton L Prevalence and clinical implications of interactive toxicity beliefs regarding mixing alcohol and antiretroviral therapies among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care and STDs . 2009;23:449–454. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne AM, Reynolds CF, Good CB, Sereika SM, Justice AC, Fine MJ How does depression influence diabetes medication adherence in older patients? American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry . 2005;13:202–210. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.3.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MT, Han HR, Hill MN, Rose L, Roary M Depression, substance use, adherence behaviors, and blood pressure in urban hypertensive black men. Annals of Behavioral Medicine . 2003;26:24–31. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatsky AL, Gunderson EP, Kipp H, Udaltsova N, Friedman GD Higher prevalence of systemic hypertension among moderate alcohol drinkers: An exploration of the role of underreporting. Journal of Studies on Alcohol . 2006;67:421–428. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kripalani S, Yao X, Haynes RB Interventions to enhance medication adherence in chronic medical conditions: A systematic review. Archives of Internal Medicine . 2007;167:540–550. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazo M, Gange SJ, Wilson TE, Anastos K, Ostrow DG, Witt MD, Jacobson LP Patterns and predictors of changes in adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: Longitudinal study of men and women. Clinical Infectious Diseases . 2007;45:1377–1385. doi: 10.1086/522762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman I, Lozano L, Villa AR, Hernández-Jiménez S, Weinger K, Caballero AE, Rull JA Psychosocial factors associated with poor diabetes self-care management in a specialized center in Mexico City. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy . 2004;58:566–570. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J, Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Fordiani JM, Balbin E Stressful life events and adherence in HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs . 2008;22:403–411. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Longshore D, Williams JK, Rivkin I, Loeb T, Warda US, Wyatt G Substance abuse and medication adherence among HIV-positive women with histories of child sexual abuse. AIDS and Behavior . 2006;10:279–286. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9041-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini M, Recchia E, Nasta P, Castanotto D, Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, Agnoletto V Illicit drug use: Can it predict adherence to antiretroviral therapy? European Journal of Epidemiology . 2004;19:585–587. doi: 10.1023/b:ejep.0000032353.03967.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P The CAGE questionnaire: Validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. American Journal of Psychiatry . 1974;131:1121–1123. doi: 10.1176/ajp.131.10.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell Holstad MK, Pace JC, De AK, Ura DR Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care . 2006;17:4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, Kerr EA The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine . 2003;348:2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O’Brien CP An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: The Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease . 1980;168:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Havens JF, McDonnell C, Lichtenstein C, Uldall K, Chesney M, Bell C Adherence to antiretroviral medications and medical care in HIV-infected adults diagnosed with mental and substance abuse disorders. AIDS Care Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV . 2009;21:168–177. doi: 10.1080/09540120802001705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. The drinker inventory of consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse: Test manual (Project MATCH Monograph Series . Vol. 4. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1995. NIH Publication No 95-3911. [Google Scholar]

- Millon T, Davis RD, Millon CM. Disorders of personality: DSM-IV and beyond . New York, NY: Wiley; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Moatti JP, Carrieri MP, Spire B, Gastaut JA, Cassuto JP, Moreau J & the Manif 2000 study group. Adherence to HAART in French HIV-infected injecting drug users: The contribution of buprenorphine drug maintenance treatment. AIDS . 14:151–155. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200001280-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugavero M, Ostermann J, Whetten K, Leserman J, Swartz M, Stangl D, Thielman N Barriers to antiretroviral adherence: The importance of depression, abuse, and other traumatic events. AIDS Patient Care and STDs . 2006;20:418–428. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Marelich WD, Hoffman D, Steers WN Predictors of antiretroviral adherence. AIDS Care . 2004;16:471–484. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001683402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician s guide . Washington, DC: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T Adherence to medication. The New England Journal of Medicine . 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves BC, Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Wells GA. on behalf of the Cochrane Non-Randomised Studies Methods Group. In: , Higgins JPT, Green S, editor. Chapter 13: Including non-randomized studies . 2008. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.0.1 [updated September 2008]. The Cochrane Collaboration. Retrieved from http://hiv.cochrane.org/sites/hiv.cochrane.org/files/uploads/Ch13_NRS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Rosof E, Mustanski B Patient-related factors predicting HIV medication adherence among men and women with alcohol problems. Journal of Health Psychology . 2007;12:357–370. doi: 10.1177/1359105307074298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretti-Watel P, Spire B, Lert F, Obadia Y Drug use patterns and adherence to treatment among HIV-positive patients: Evidence from a large sample of French outpatients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence . 2006;82:S71–S79. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(06)80012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protopopescu C, Raffi F, Roux P, Reynes J, Dellamonica P, Spire B, Carrieri M-P & on behalf of the ANRS CO8 (APROCO-CO-PILOTE) Study Group. Factors associated with non-adherence to long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy: A 10 year follow-up analysis with correction for the bias induced by missing data. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy . 2009;64:599–606. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothlind JC, Greenfield TM, Bruce AV, Meyerhoff DJ, Flenniken DL, Lindgren JA, Weiner MW Heavy alcohol consumption in individuals with HIV infection: Effects on neuropsychological performance. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society . 2005;11:70–83. doi: 10.1017/S1355617705050095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux P, Carrieri MP, Michel L, Fugon L, Marcellin F, Obadia Y, Spire B Effect of anxiety symptoms on adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected women. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry . 2009;70:1328–1329. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08l04885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL, Salomon E, Johnson W, Mayer K, Boswell S Two strategies to increase adherence to HIV antiretroviral medication: Life-Steps and medication monitoring. Behaviour Research andTherapy . 2001;39:1151–1162. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet JH, Horton NJ, Meli S, Freedberg KA, Palepu A Alcohol consumption and antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected persons with alcohol problems. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research . 2004;28:572–577. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000122103.74491.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor T, de la Fuente JR, Grant M Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction . 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva MCF, Ximenes RAA, Filho DBM, Arraes LWMS, Mendes M, Melo ACS, Fernandes PRM Risk-factors for non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo . 2009;51:135–139. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652009000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. Lifetime drinking history: Administration and scoring guidelines. Toronto. Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: , Litten RZ, Allen J, editor. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods . Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Spire B, Duran S, Souville M, Leport C, Raffi F, Moatti JP APROCO cohort study group. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapies (HAART) in HIV-infected patients: From a predictive to a dynamic approach. Social Science & Medicine . 2002;54:1481–1496. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stampfer MJ, Kang JH, Chen J, Cherry R, Grodstein F Effects of moderate alcohol consumption on cognitive function in women. The New England Journal of Medicine . 2005;352:245–253. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, Campsmith ML, Nakamura GV, Begley EB, Schulden J, Nakashima AK Patient and regimen characteristics associated with self-reported nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy. PLoS ONE . 2007;2(6):e552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000552. Retrieved from http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0000552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theall KP, Clark RA, Powell A, Smith H, Kissinger P Alcohol consumption, ART usage and high-risk sex among women infected with HIV. AIDS and Behavior . 2007;11:205–215. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BJ Gaps in addressing problem drinking: Overcoming primary care and alcohol treatment deficiencies. Current Psychiatry Reports . 2009;11:345–352. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop-Valverde D, Ownby RL, Wilkie FL, Mack A, Kumar M, Metsch L Neurocognitive aspects of medication adherence in HIV-positive injecting drug users. AIDS and Behavior . 2006;10:287–297. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop-Valverde D, Valverde E Homelessness and psychological distress as contributors to antiretroviral nonadherence in HIV-positive injecting drug users. AIDS Patient Care and STDs . 2005;19:326–334. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Bohn RL, Knight E, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Avorn J Noncompliance with antihypertensive medications: the impact of depressive symptoms and psychosocial factors. Journal of General Internal Medicine . 2002;17:504–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.00406.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wu Z Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV/AIDS patients in rural China. AIDS . 2007;21(Supplement 8):S149–S155. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304711.87164.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa. Ontario: Ottawa Health Research Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]