Abstract

Amphiphilic aryl radicals generated upon visible light irradiation of arylazo sulfones have been exploited in the development of a solventylation strategy via hydrogen atom transfer (HAT). The present protocol succeeded in the versatile functionalization of various olefins with carbon-centered radicals deriving from acetone, acetonitrile, chloroform, methylene chloride, nitromethane, methyl acetate, and methyl formate under metal- and photocatalyst-free conditions. The direct addition of the aryl radicals onto the olefin substrates was suppressed under high dilution conditions.

Introduction

The development of protocols for the selective manipulation of C(sp3)–H bonds proved over time to be an extremely convenient approach for the late-stage functionalization of molecules, with application spacing from medicinal chemistry to natural product synthesis.1 Among the possible methodologies to engage C–H groups in effective transformations, direct and indirect hydrogen atom transfer (HAT)2 as well as proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET)3 reactions play a prominent role. The feasibility, efficiency, and selectivity of these processes are generally determined by the bond dissociation energies (BDEs) of the involved C–H bonds and their polarity.4 However, despite the impressive variety of HAT-based protocols proposed in the last decade,5 the parasitic abstraction from a molecule of the solvent6 can often hamper their development, especially when dilute conditions are required.

On the other hand, some efforts to exploit such secondary paths for synthetic purposes have been made.7 In this regard, Zhao described the solventylation of acrylamides using acetonitrile and dichloromethane as the media, with boronic acid as the aryl radical precursor and a stoichiometric quantity of manganese(III) acetate as the oxidant.7b Van der Eycken reported a similar approach using ketones, nitromethane, or acetonitrile as media and dicumyl peroxide as the HAT agent precursor and copper(II) chloride as the radical mediator.7c Liu reported the use of saturated hydrocarbons in the presence of copper(I) and dicumyl peroxide at high temperatures.7d We recently reported an effective flow approach to the acetonylation of various alkenes based on the very HAT event from the solvent itself.8 Indeed, the low working concentration (0.01 M of the starting substrate) allows HAT from acetone to an aryl radical (generated through the ruthenium(II)-photoredox catalyst) to occur as the only path,9 turning this commonly unproductive HAT into the key step toward the functionalization of olefin moieties (Scheme 1a).

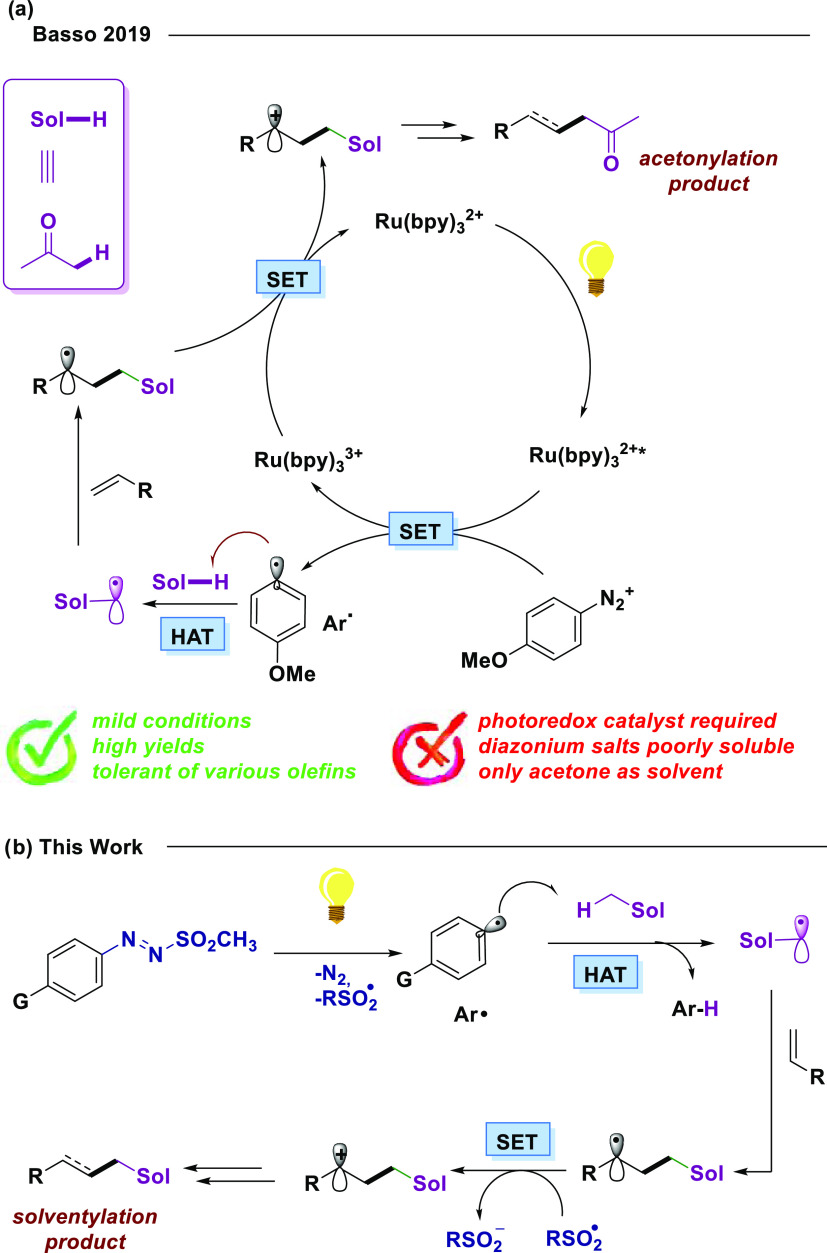

Scheme 1. (a) Functionalization of Olefins Exploiting Aryl Radical-Induced HAT from Acetone Optimized by Our Group.

Conditions: 4-MeOPhN2BF4 (1 equiv), Ru(bpy)3Cl2 (1 mol %), acetone 0.01 M, 450 nm flow; (b) envisioned photochemical activation of the solvent via arylazo sulfones as aryl radical precursors and subsequent olefin functionalization.

Although conceptually fascinating, robust, and reliable, all of the aforementioned proposals suffer from limited versatility, generally due to the low solubility of the radical precursors or of the catalyst. Furthermore, heavy or transition metal species are often required. For this aim, a general and efficient protocol that could be applied to any solvent under metal-free conditions is highly desirable since it would allow the facile and straightforward incorporation of different functional groups on the same substrate with ease. To achieve this target, the ideal precursor must be labile under visible light and virtually soluble in all organic media. Furthermore, its decomposition should deliver volatile by-products, making the purification step trivial. To circumvent the limitations of the previously published approaches, we found in arylazo sulfones the optimal match to our needs (Scheme 1b). Thanks to the presence of a dyedauxiliary group (N2SO2R),10 these derivatives absorb visible light in the 400–450 nm region (with e ranging 100–200 M–1 cm–1) and efficiently release an aryl/sulfonyl radical pair upon homolytic cleavage of the N–S bond followed by nitrogen loss from the so-obtained aryl diazenyl radical.11 Since their peculiar photoreactivity, such compounds find multifaced applications in synthesis10 as photoacid generators (PAGs)12 and as initiators in free-radical polymerization.13

In view of such premises, we report herein an arylazo sulfone-mediated synthetic platform that allows the visible light solventylation of alkenes by a large variety of organic solvents. Since our former Ru(II)-catalyzed protocol8 required an oxidative step (i.e., the turnover event of the photocatalytic cycle, with the renewal of the catalyst itself), we envisioned that such a step could either take place upon SET to the concomitantly generated sulfur-centered radical (that should be easily reduced to the corresponding sulfinate anion) or by means of an external oxidant.

Results and Discussion

Optimization of Reaction Conditions

In analogy with our previous studies,8 where 4-methoxyphenyl radical proved its optimal abstracting properties, we started our investigations using 1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-(methylsulfonyl)diazene (2a) as a radical precursor and olefin 1a as a radical trap (Scheme 2). When the reaction mixture was irradiated in a batch with a single high-power blue light-emitting diode (LED) in acetone (0.01 M), the desired acetonylation product 3a was found in a moderate 48% yield (entry 1, Table 1). While proving the possibility of performing the acetonylation with azosulfones, the moderate yield and the presence of an unquantified quantity of sulfonyl addition product 4a suggested that the competitive addition of the sulfonyl radical to the alkene moiety occurred. Upon the addition of potassium persulfate as an external oxidant (entry 2), the yield increased consistently, although some by-product 4a was still detected (7.6:1 ratio to the product). Hydrogen peroxide gave very low yields (entry 3), while bis(acetoxyiodo)benzene (BAIB, entry 4) and tert-butylhydroperoxide (TBHP, entry 5) gave product 4a in 57% and 70% yields, respectively, but the complicated chromatographic procedure for the purification that the use of BAIB involves and the poor compatibility of TBHP in media different from acetone make potassium persulfate (whose insoluble unreacted leftovers and by-products can be filtered off easily) the preferred choice. Notably, its low solubility implies a lower concentration of the active oxidant in the solution, but when a phase transfer catalyst was used to improve its solubility, the reaction yield decreased (entry 6). In analogy with our previous findings,8 aryl radicals with EW groups generated from arylazo sulfone 2b resulted in a poorer HAT process (entry 7). We then tried to change the structure of the arylazo compound on the sulfone moiety to reduce the formation of the sulfonylated by-product. Compound 2c, bearing a phenyl group, could deliver more stable, less reactive sulfur-centered radicals. However, this precursor afforded lower yields and lower product/by-product ratios (entry 8). Compound 2d, on the other hand, bearing a tert-butyl group, could deliver a very unstable tert-butyl sulfinyl radical. Unfortunately, alkylation of 1a did not occur in this case, and azo compound 5 (obtained via SO2 extrusion from 2d, entry 9) was isolated, analogously to what was previously described under thermal conditions.14 In the end, the conditions described in entry 2 (K2S2O8 as an oxidant) have been selected for investigating the scope of the reaction.

Scheme 2. Optimization of the Acetonylation Reaction Using Azosulfones.

Table 1. Results for the Optimization of the Acetonylation Conditions Using Azosulfones.

| entry | conditionsa | yield (3a)b | yield by-productb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2a | 48% | n.d. |

| 2 | 2a, K2S2O8 (2 equiv) | 76% | 10% (4a) |

| 3 | 2a, H2O2 120 volume (2 equiv) | 20% | n.d. |

| 4 | 2a, BAIB (2 equiv) | 57% | 7% (4a) |

| 5 | 2a, TBHP (2 equiv) | 70% | 15% (4a) |

| 6 | 2a, K2S2O8 (2 equiv), PTCc (10 mol %) | 54% | n.d. |

| 7 | 2b, K2S2O8 (2 equiv) | 30% | 8% (4a) |

| 8 | 2c, K2S2O8 (2 equiv) | 57% | 28% (4b) |

| 9 | 2d, K2S2O8 (2 equiv) | n.d. | 30% (5) |

All reactions were performed in acetone (0.01 M both in 1a and 2) and irradiated for 24 h at 450 nm.

Yields are referred to isolated products after column chromatography.

PTC: phase transfer catalyst (tetrabutylammonium bromide).

Scope and Applications

We then moved to investigate the scope of our protocol. To our delight, as summarized in Scheme 3 (top), the solvent scope resulted to be much broader than that of the existing methods. Acetone, acetonitrile, chloroform, dichloromethane, and nitromethane delivered the corresponding products in satisfactory yields. Also, 2-bromopropane and methyl acetate worked in the transformation, albeit in lower yields. Satisfyingly, methyl formate delivered the corresponding acyl radical in place of the a-oxy radical. When oxygen-containing solvents (namely, THF, Et2O, MTBE, methanol, and trimethyl orthoformate) were employed, no products from the trapping of the corresponding a-oxy radicals were observed. Similarly, DMF, formamide, and toluene did not deliver any product. These unexpected results could be explained by considering the presence of the external oxidant that might oxidize to the corresponding cations, the α-oxy and α-amido radicals generated upon HAT from the aforementioned solvents. This rationale would also explain why methyl formate delivered appreciably only the acyl radical and not the α-oxy one.

Scheme 3. Investigation of the Solvent Scope using Acrylamide 1a under Optimized Conditions (Top).

Solventylation reactions with acrylamides 1b–1d and olefin 1e (bottom). Yields are referred to isolated products after column chromatography. Yields in brackets are referred to by-products 4a–4e.

Having screened the solvent tolerability, we moved to probe the tolerance of our methodology to several olefin substrates. Acrylamides 1b–1d proved to be well responsive to our methodology, undergoing the solventylation process with ease and affording the desired products in good to highly satisfactory yields in almost all cases (Scheme 3, bottom), with the only exception of 3m, where the presence of an EW aromatic group seems to hamper the process by probably disfavoring the oxidation step.

Indeed, olefin 1d, which bears a donating group in the same position, was converted to compounds 3n–3r in higher yields. As expected, the corresponding sulfonyl-containing side products 4c–4e were found as well in all cases, although generally in low yields. Interestingly, most compounds were already known in the literature, but their synthesis is reported through different processes under different conditions, thus requiring several approaches despite the common central scaffold. By contrast, our versatile methodology allows us to easily afford such products without changing any experimental parameter but the reaction solvent, gathering all of the possible functionalization strategies for such substrates in a single protocol. Among other olefins, ethyl 2-vinylbenzoate 1e gave the desired acetonylation product 3s in a moderate yield using BAIB as the oxidant in place of potassium persulfate (Scheme 3, bottom).

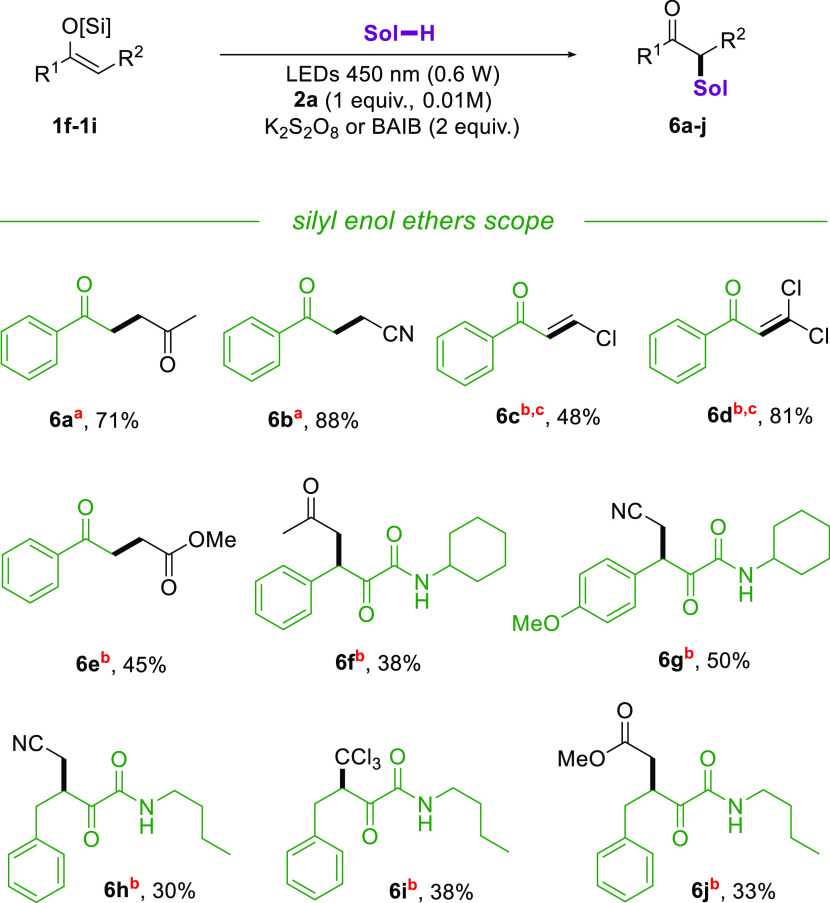

We then moved to investigate the tolerance of electron-rich olefins such as silyl enolethers 1f–1i in our protocol (Scheme 4). To our delight, products 6a and 6b were isolated in high yields. However, the reaction initially failed in delivering the desired products with other solvents, affording the deprotected ketone precursor instead. This is probably due to the slightly acidic conditions developed in the reaction environment12 when the substrate is not consumed at a sufficiently high rate. Switching the oxidant from potassium persulfate to BAIB allowed to isolate the desired products in moderate to good yields, the acetate ion slowly released being useful as a buffering agent to avoid the decomposition of the substrate. Molecules 6c and 6d were isolated by following the base-induced dehydrochlorination of the corresponding solventylation products on the crude reaction mixture. Silyl enolethers 1g–1i afforded the expected solventylation products 6f–6j in lower yields, a result in line with our previous study showing their scarce reactivity both in polar and radical transformations.15 Interestingly, no side products derived from the incorporation of the sulfinyl radical were isolated this time.

Scheme 4. Solventylation Reaction with Silyl Enolethers 1f–1i.

Yields are referred to isolated products after column chromatography. K2S2O8 (2 equiv) used as an oxidant.

BAIB (2 equiv) used as an oxidant.

Obtained after elimination with Et3N (2 equiv).

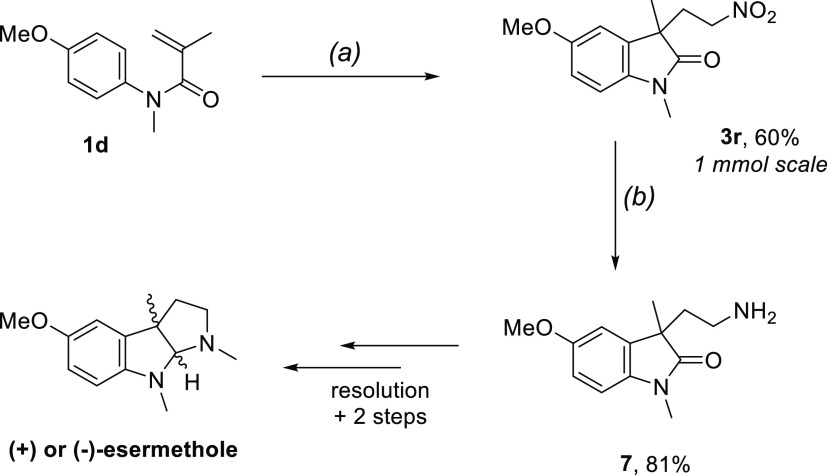

We finally applied the solventylation protocol to the synthesis of a key intermediate toward the total synthesis of the natural product esermethole, a precursor to physostigmine16 (Scheme 5). We first performed the synthesis of molecule 3r on a 1 mmol scale by running several batches in parallel. The desired solventylation product was then reduced to amine 7, which can be further elaborated to both enantiomers of esermethole through a chiral resolution and two additional synthetic steps.17

Scheme 5. Use of the Solventylation Protocol for the Preparation of an Advanced Intermediate in the Synthesis of Esermethole.

Conditions: (a) 2a (1 equiv, 0.01 M), K2S2O8 (2 equiv), MeNO2, HP LEDs 450 nm (0.6 W), overnight (b) Fe (5 equiv), HCl 6 M:MeOH 1:1 (0.33 M), 110 °C, 3 h.

Mechanistic Insights

Having an efficient protocol in our hands, we decided to get more information about the possible mechanism and the kinetics of our transformation. We selected the reaction reported in Scheme 2 under optimized conditions for our investigation. First, we selectively removed some elements in selected control experiments. No consumption of the starting materials was observed when the reaction was left overnight under stirring in the dark, proving both the necessity of light for the process to occur and the stability of the reagents without irradiation. Also, to rule out the possibility of a photoinitiated thermal radical pathway, we performed the model reaction under light/dark cycles, proving that the consumption of the starting materials and the formation of the product only occur under continuous irradiation (see the Supporting Information). When the reaction was performed using only 0.25 equiv of 2a with respect to radical trap 1a, product 3a was isolated in 24% yield, with 8% of by-product 4a. The arylazo sulfone seems to be necessary for stoichiometric amounts, and the two processes leading to the formation of 3a and 4a seem to be independent of each other. We then evaluated the effect of concentration on the outcome of the process. Performing the model reaction illustrated in Scheme 2 at increasingly higher concentrations (0.02, 0.05, and 0.1 M) led to a steady decrease in the product yield (66, 45, and 33%, respectively). When the reaction was performed at 0.1 M concentration, compound 8 (Scheme 6), incorporating the aryl ring, was also formed in 7% yield. Replacing acetone with 0.1 M acetonitrile led to a mixture of products 3b, 4a, and 8 in 42, 43, and 13% yields, respectively (Scheme 6). These findings proved once again the strong dependence of the efficiency of our protocol on the reaction concentration, suggesting that dilution plays a fundamental role in making HAT efficient and the overall process selective for the desired solventylation product.

Scheme 6. Outcome of the Solventylation Reaction of 1a with Acetonitrile under Concentrated (0.1 M) Conditions.

Yields are referred to isolated products after column chromatography.

Afterward, we moved our attention to the HAT event. To understand better its role in our process, we evaluated the kinetic isotope effect (KIE) of the process. First, we performed the reaction in hexadeuteroacetone isolating 3a-d5 in 55% yield. Having a reference sample of the deuterated product in our hands, we then carried out the model reaction in a 1:1 mixture of acetone/acetone-d6 and isolated the product mixture, which, finding upon gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis, had a 3a to 3a-d5 product ratio of 12:1. These findings indicate the occurrence of a primary KIE in our transformation, hinting at the HAT event as the rate-determining step of the process. We finally measured the quantum yield of the model reaction by means of NMR analyses of the reaction mixture at a given irradiation time (see the Supporting Information for additional details).18 The quantum yield value for the consumption of 2a (Φ–1) was 0.0031, lower than the one reported by Fagnoni (0.02) for the visible-light-driven generation of sulfinic acids in acetonitrile using the same compound.12 The quantum yield for the acetonylation process Φsolv was found to be 0.0009, as expected, taking into account the complexity of the reaction pathway and the low quantum yield of the photoactive precursor.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we reported herein an unprecedented approach to functionalize olefins directly from the reaction solvent, employing a source of aryl radicals and exploiting the effect of high dilution. The methodology has proven to be robust with a wide variety of olefin substrates and an acceptable number of solvents, thus allowing for the introduction of keto, nitrile, nitro, ester, and halogenated functionalities on alkenes. The need for an external oxidant, the formation in some instances of sulfonyl by-products, and the failure with various oxygenated solvents are drawbacks that we will aim to eliminate in the future, possibly with the aid of kinetic and computational studies.

Experimental Section

General Information

NMR spectra were recorded either at 300 MHz (1H) and 75 MHz (13C) on a Varian Mercury 300 or at 400 MHz (1H) and 100 MHz (13C) on a Jeol JNM-ECZ400R. The chemical shifts (δ) are expressed in parts per million relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard (0.00 ppm). Coupling constants are reported in hertz. NMR acquisitions were performed at 300 K, and CDCl3 was used as a solvent unless otherwise stated. High-resolution MS (HRMS) analyses were carried out on a Synapt G2 QToF mass spectrometer. MS signals were acquired from 50 to 1200 m/z in the ESI positive ionization mode. GC–MS analyses were carried out on Shimadzu GC–MS-QP2010 SE with an AOC-20i Plus auto-injector mounting an Avantor Hichrom HI-5 MS column (internal diameter 0.25 mm, film thickness 0.25 mm, length 30 m). Samples were prepared upon dilution 1:100 in Et2O of a mother solution of an estimated 1000 ppm concentration. Run parameters: Vinj = 6 mL, Tinj = 250 °C, Tramp = 3 min@120 °C, then 10 °C/min up to 300 °C, then 4 min@300 °C, total run time 25 min, He carrier gas, column flow 1 mL/min, split ratio 1:10, MS acquisition (TIC, m/z range 35–250) from 3 to 25 min. Reactions were monitored by TLC. TLC analyses were carried out on silica gel plates (thickness = 0.25 mm), viewed at UV (λ = 254 nm), and developed with the Hanessian stain (dipping into a solution of (NH4)4MoO4·4H2O (21 g) and Ce(SO4)2·4H2O (1 g) in H2SO4 (31 mL) and H2O (469 mL) and warming). Column chromatographies were performed with the “flash” methodology using 220–400 mesh silica. Solvents employed as eluents and for all other routinary operations, as well as anhydrous solvents and all reagents used, were purchased from commercial suppliers and employed without any further purification.

Starting materials were synthesized according to literature procedures, and analytical data were in accordance with the literature (see the Supporting Information for details).

General Procedure for the Solventylation Reaction

The desired olefin (0.08 mmol, 1 equiv), the oxidant (0.16 mmol, 2 equiv), and the arylazo sulfone (0.08 mmol, 1 equiv) were loaded to a crimp top vial along with a magnetic stir bar and sealed. The vial was purged of air through 5 vacuum/argon cycles, and then the desired solvent (8 mL, 0.01 M, previously degassed by argon sparging for at least 20 min) was added. The solution was then placed in the photochemical reactor and irradiated overnight (16–20 h), generally discoloring from bright yellow to mildly beige or to a colorless solution. Any residual solids, if visible, were filtered off over a celite pad, and then the crude mixture was purified upon flash chromatography.

3-(2-Bromo-2-methylpropyl)-1,3-dimethylindolin-2-one 3h

Colorless oil. Rf = 0.60 (EtOAc/PE 1:3). Yield 17%. 1H NMR δ 7.34–7.23 (m, 2H), 7.06 (tt, J = 7.7, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 3.22 (s, 3H), 2.95 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 2.65 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 1.54 (s, 3H), 1.37 (s, 3H), 1.33 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR δ 179.8, 142.9, 132.3, 128.1, 124.4, 122.2, 108.3, 65.4, 53.6, 48.0, 35.4, 35.0, 27.7, 26.4. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C14H18BrNO+, 296.0645; found, 296.0637.

1-Benzyl-3-methyl-3-((methylsulfonyl)methyl)indolin-2-one 4c

Colorless oil. Rf = 0.21 (EtOAc/PE 1:1). Yield 9–41%. 1H NMR δ 7.38–7.31 (m, 5H), 7.30–7.25 (m, 1H), 7.22 (td, J = 7.8, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (td, J = 7.6, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 6.77 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 5.05 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 4.89 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 3.78 (d, J = 13.9 Hz, 1H), 3.62 (d, J = 14.7 Hz, 1H), 2.66 (s, 3H), 1.52 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR δ 178.0, 142.6, 135.7, 130.3, 129.1, 129.0, 127.8, 127.4, 123.7, 122.9, 110.1, 60.7, 45.9, 44.4, 43.5, 26.2. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C18H20NO3S+, 330.1158; found, 330.1152.

5-Methoxy-1,3-dimethyl-3-((methylsulfonyl)methyl)indolin-2-one 4d

Colorless oil. Rf = 0.04 (EtOAc/PE 2:3). Yield 10–35%. 1H NMR δ 6.98 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 3.69 (d, J = 14.7 Hz, 1H), 3.54 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 3.24 (s, 3H), 2.68 (s, 3H), 1.46 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR δ 176.9, 156.2, 136.9, 131.7, 113.2, 111.0, 109.3, 60.8, 56.0, 46.3, 43.5, 26.8, 25.2. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C13H18NO4S+, 289.0951; found, 289.0953.

5-Acetyl-1,3-dimethyl-3-((methylsulfonyl)methyl)indolin-2-one 4e

Colorless oil. Rf = 0.14 (EtOAc/PE 2:3). Yield 8%. 1H NMR δ 8.02–7.98 (m, 2H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (d, J = 14.7 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (d, J = 14.7 Hz, 1H), 3.31 (s, 3H), 2.69 (s, 3H), 2.61 (s, 3H), 1.48 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR δ 196.8, 178.3, 147.9, 132.7, 131.7, 130.8, 123.4, 108.4, 60.7, 45.6, 43.6, 27.0, 26.6, 25.2. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C14H18NO4S+, 296.0951; found, 296.0947.

4-Cyano-N-cyclohexyl-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-oxobutanamide 6g

Yellow foam. Rf = 0.36 (EtOAc/PE 1:3). Yield 50%. 1H NMR δ 7.18 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 5.06 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.63 (tdt, J = 10.5, 7.6, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 2.91 (dd, J = 16.9, 7.5 Hz, 1H), 2.79 (dd, J = 16.8, 7.7 Hz, 1H), 1.95–1.86 (m, 1H), 1.78–1.64 (m, 3H), 1.41–1.05 (m, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR δ 194.7, 160.0, 157.9, 129.9, 125.5, 117.8, 115.0, 55.4, 48.8, 46.9, 32.7, 32.6, 25.4, 24.8, 20.3. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C18H22N2O3+, 315.1703; found, 315.1710.

3-Benzyl-N-butyl-4-cyano-2-oxobutanamide 6h

Amorphous solid. Rf = 0.65 (EtOAc/PE 1:1). Yield 30%. 1H NMR δ 7.34–7.22 (m, 3H), 7.20–7.17 (m, 2H), 6.94 (br s, 1H), 4.06 (dtd, J = 8.8, 6.2, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 3.35–3.24 (m, 3H), 2.80 (dd, J = 13.9, 8.8 Hz, 1H), 2.50 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 1.60–1.49 (m, 2H), 1.36 (hex, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 0.94 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR δ 197.6, 159.0, 136.6, 129.2, 129.1, 127.5, 117.7, 43.9, 39.4, 36.1, 31.3, 20.1, 17.2, 13.8. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C16H21N2O2+, 273.1598; found, 273.1600.

3-Benzyl-N-butyl-4,4,4-trichloro-2-oxobutanamide 6i

Amorphous solid. Rf = 0.32 (EtOAc/PE 1:6). Yield 38%. 1H NMR: δ 7.34–7.22 (m, 5H), 6.88 (s, 1H), 5.57 (dd, J = 7.9, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 3.43 (dd, J = 14.2, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 3.32 (q, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 3.15 (dd, J = 14.2, 7.9 Hz, 1H), 1.56 – 1.50 (m, 2H), 1.36 (hex, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 0.94 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR: δ 197.6, 159.0, 136.6, 129.2, 129.1, 127.5, 117.7, 43.9, 39.4, 36.1, 31.3, 20.1, 17.2, 13.8 (−CCl3 carbon is missing). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C15H19Cl3NO2+, 350.0476; found, 350.0469.

Methyl 3-benzyl-5-(butylamino)-4,5-dioxopentanoate 6j

Amorphous solid. Rf = 0.53 (EtOAc/PE 1:5). Yield 33%. 1H NMR: δ 7.31–7.25 (m, 2H), 7.25–7.15 (m, 3H), 6.92 (br s, 1H), 4.20–4.11 (m, 1H), 3.59 (s, 3H), 3.32 (tdd, J = 7.1, 6.1, 2.5 Hz, 2H), 3.15 (dd, J = 13.5, 5.1 Hz, 1H), 2.77 (dd, J = 17.0, 10.0 Hz, 1H), 2.60–2.47 (m, 2H), 1.59–1.50 (m, 2H), 1.43–1.31 (m, 2H), 0.94 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR: δ 200.0, 172.4, 159.7, 138.0, 129.3, 128.7, 126.9, 52.0, 42.9, 39.3, 36.9, 34.6, 31.4, 20.1, 13.8. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C17H24NO4+, 306.1700; found, 306.1696.

3-(2-Aminoethyl)-5-methoxy-1,3-dimethylindolin-2-one 7

Product 3r (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv) was weighted in a sealable vial and dissolved under stirring in a methanol (0.3 mL) and HCl (6 M, 0.3 mL) mixture. The first portion of iron dust (3 equiv) was added, the vial was sealed, and the reaction vessel was brought to 110 °C for 2 h, monitoring the disappearance of the starting material via TLC (PE:EtOAc 3:1) and adding additional iron dust until complete consumption of 3r occurred (2 equiv of iron dust for a total of 3 h were needed). The reaction mixture was then brought to r.t. and filtered over a celite pad with methanol; then, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude was dissolved in water (2 mL), moved to a separatory funnel, and basified with 25% NH3 (pH = 11) before extraction with chloroform (3 × 5 mL). The combined organic layers were washed once with brine (10 mL) and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The crude was eventually purified upon flash chromatography to give the desired product as a colorless oil. Rf = 0.15 (3% MeOH in DCM + 1% Et3N). Yield 81%. 1H NMR: δ 6.85–6.66 (m, 3H), 5.00 (br s, 2H), 3.78 (s, 3H), 3.16 (s, 3H), 2.67–2.48 (m, 2H), 2.18 (ddd, J = 13.4, 9.8, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 2.07 (ddd, J = 13.4, 10.1, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 1.35 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR: δ 179.9, 156.5, 136.3, 134.4, 112.5, 110.2, 108.8, 55.9, 47.5, 37.3, 36.6, 26.5, 24.0. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C13H19N2O2+, 234.1441; found, 235.1448.

1,3-Dimethyl-3-(3-oxobutyl-2,2,4,4,4-pentadeutero)indolin-2-one 3a-d5

White solid. Rf = 0.28 (EtOAc/PE 3:1). Yield 55%. 1H NMR: δ 7.32–7.28 (m, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.11–7.04 (m, 1H), 6.86 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.23 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 3H), 2.20–2.02 (m, 2H), 1.38 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR: δ 208.04 (d, J = 7.0 Hz), 180.2, 143.2, 133.4, 128.1, 122.7, 122.8, 108.1, 47.4, 38.7–37.8 (m), 31.7, 30.0–28.7 (m), 26.3, 23.7. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C14H12D5NO2+, 237.1646; found, 237.1640. GC–MS tr = 12.53 min: 44 (6.59), 46, (18.25), 77 (8.37), 91 (5.11), 117 (12.83), 130 (14.23), 131 (5.64), 132 (15.88), 145 (6.72), 160 (100.00), 161 (32.80), 162 (56.41), 163 (6.88), 173 (5.03), 174 (5.21), 235 (19.49), 236 (M, 38.59), 237 (5.76).

Acknowledgments

A.B. would like to acknowledge Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo—Bando Trapezio for financial support (grant ID ROL 67533). The University of Genova is kindly acknowledged for the contribution to the acquisition of an NMR instrument (D.R. 3404 19/7/2018).

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online supplementary material.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c07172.

Photochemical equipment; synthetic procedures; reaction monitoring during dark/light cycles; determination of the quantum yield; characterization of compounds; and copies of GC–MS and NMR spectra (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- See for review:; a Guillemard L.; Kaplaneris N.; Ackermann L.; Johansson M. J. Late-stage C–H functionalization offers new opportunities in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 522–545. 10.1038/s41570-021-00300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Börgel J.; Ritter T. Late-stage functionalization. Chem 2020, 6, 1877–1887. 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Baudoin O. Multiple catalytic C–H Bond Functionalization for Natural Product Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 17798–17809. 10.1002/anie.202001224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See for review:; a Capaldo L.; Quadri L.; Ravelli D. Photocatalytic hydrogen atom transfer: the philosopher’s stone for late-stage functionalization?. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 3376–3396. 10.1039/D0CS00493F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Cannalire R.; Pelliccia S.; Sancineto L.; Novellino E.; Tron G. C.; Giustiniano M. Visible light photocatalysis in the late-stage functionalization of pharmaceutically relevant compounds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 766–897. 10.1039/D0CS00493F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray P. R. D.; Cox J. H.; Chiappini D. N.; Roos C. B.; McLoughlin E. A.; Hejna B. G.; Nguyen S. T.; Ripberger H. H.; Ganley J. M.; Tsui E.; Shin N. Y.; Koronkiewicz B.; Qiu G.; Knowles R. R. Photochemical and Electrochemical Applications of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2017–2291. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldo L.; Ravelli D.; Fagnoni M. Direct Photocatalyzed Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT) for Aliphatic C–H Bonds Elaboration. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1875–1924. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespi S.; Fagnoni M. Generation of Alkyl Radicals: From the Tyranny of Tin to the Photon Democracy. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 9790–9833. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S.; Cheung K. P. S.; Gevorgyan V. C–H functionalization reactions enabled by hydrogen atom transfer to carbon-centered radicals. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 12974–12993. 10.1039/D0SC04881J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See for instance; a Yu Y.; Zhuang S.; Liu P.; Sun P. Cyanomethylation and Cyclization of Aryl Alkynoates with Acetonitrile under Transition-Metal-Free Conditions: Synthesis of 3-Cyanomethylated Coumarins. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 11489–11495. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li X.; Xu J.; Gao Y.; Fang H.; Tang G.; Zhao Y. Cascade Arylalkylation of Activated Alkenes: Synthesis of Chloro- and Cyano-Containing Oxindoles. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 2621–2626. 10.1021/jo502777b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhao Y.; Sharma N.; Sharma U. K.; Li Z.; Song G.; Van der Eycken E. V. Microwave-Assisted Copper-Catalyzed Oxidative Cyclization of Acrylamides with Non-Activated Ketones. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 5878–5882. 10.1002/chem.201504776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Li Z.; Zhang Y.; Zhang L.; Liu Z.-Q. Free-Radical Cascade Alkylarylation of Alkenes with Simple Alkanes: Highly Efficient Access to Oxindoles via Selective (sp3)C–H and (sp2)C–H Bond Functionalization. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 382–385. 10.1021/ol4032478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Tian Y.; Liu Z.-Q. Metal-free radical cascade dichloromethylation of activated alkenes using CH2Cl2: highly selective activation of the C–H bond. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 64855–64859. 10.1039/C4RA12032A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Lu M.-Z.; Loh T.-P. Iron-Catalyzed Cascade Carbochloromethylation of Activated Alkenes: Highly Efficient Access to Chloro-Containing Oxindoles. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 4698–4701. 10.1021/ol502411c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anselmo M.; Basso A.; Protti S.; Ravelli D. Photoredox-Catalyzed Generation of Acetonyl Radical in Flow: Theoretical Investigation and Synthetic Applications. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 2493–2500. 10.1021/acscatal.8b03875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The different outcome of the same reaction at higher concentrations was reported here:; Anselmo M.; Moni L.; Ismail H.; Comoretto D.; Riva R.; Basso A. Photocatalyzed synthesis of isochromanones and isobenzofuranones under batch and flow conditions. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 1456–1462. 10.3762/bjoc.13.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu D.; Lian C.; Mao J.; Fagnoni M.; Protti S. Dyedauxiliary Groups, an Emerging Approach in Organic Chemistry. The Case of Arylazo Sulfones. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 12813–12822. 10.1021/acs.joc.0c01895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdulla H. O.; Scaringi S.; Amin A. A.; Mella M.; Protti S.; Fagnoni M. Aryldiazenyl Radicals from Arylazo Sulfones: Visible Light-Driven Diazenylation of Enol Silyl Ethers. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 2150–2154. 10.1002/adsc.201901424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Terlizzi L.; Martinelli A.; Merli D.; Protti S.; Fagnoni M.. Arylazo Sulfones as Nonionic Visible-Light Photoacid Generators J. Org. Chem. 2022, 10.1021/acs.joc.2c01248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitti A.; Batteaux F.; Martinelli A.; Protti S.; Fagnoni M.; Pasini D. Blue light driven free-radical polymerization using arylazo sulfones as initiators. Polym. Chem. 2021, 12, 5747–5751. 10.1039/D1PY00928A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M.; Gotoh M.; Yoshida M. Radical Switch Reaction. A Novel Reaction between Two Free Radicals in a Solvent Cage. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1987, 60, 295–299. 10.1246/bcsj.60.295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibba F.; Capurro P.; Garbarino S.; Anselmo M.; Moni L.; Basso A. Photoinduced Multicomponent Synthesis of α-Silyloxy Acrylamides, an Unexplored Class of Silyl Enol Ethers. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1098–1101. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano S.; Ogasawara K.. The Alkaloids; Brossi A., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, 1989; Vol. 36, p 225. [Google Scholar]

- Pallavicini M.; Valoti E.; Villa L.; Lianza F. Synthesis of (−)- and (+)-esermethole via chemical resolution of 1,3-dimethyl-3-(2-aminoethyl)-5-methoxyoxindole. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1994, 5, 111–116. 10.1016/S0957-4166(00)80490-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capurro P.; Lambruschini C.; Lova P.; Moni L.; Basso A. Into the Blue: Ketene Multicomponent Reactions under Visible Light. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 5845–5851. 10.1021/acs.joc.1c00278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online supplementary material.