Abstract

Titanium membranes and meshes are used for the repair of trauma, tumors, and hernia in dentistry and maxillofacial and abdominal surgery. But such membranes demonstrate the limited effectiveness of integration in recipients due to their bioinertness. In this study, we prepared titania oxide (by microarc oxidation) and/or HAp (by electrophoresis deposition) coatings with alginate soaking. We used annealing at 700 °C for 2.5 h for HAp crystallinity increasing with achievement of an acceptable Ca2+ release rate. The feedstock HAp and prepared coatings were characterized by X-ray diffraction, IR spectroscopy, electron and optical confocal microscopy, and thermal analysis, as well as the in vitro study of solubility in saline and in vivo tests with the animal model of subcutaneous implantation (with Wistar rats). Biocompatible compounds were found for all deposited coatings. We noted that the best biological response was detected for the annealed Ca–P/TiO2 bilayer with alginate binding. In this case, the coating crystallinity was ≈40.5–50.0%. The Ca2+ release rate was 2.042 ± 0.058%/mm2 at 168 h after immersion in saline. Thin and mature tissue capsules with minimal inflammation and vascularization were found in histological sections. We did not detect any unwanted responses around the implants, including inflammation infiltration, suppuration, bacterial infections, tissue lyses, and, finally, implant rejection. This information is expected to be useful for understanding the properties of bioactive ceramic coatings and improving the quality of medical care in dentistry and maxillofacial surgery and other applications of titanium membranes in medicine.

1. Introduction

Metallic meshes and membranes are widely used in dentistry, oral and maxillofacial surgery for guided bone regeneration (GBR),1−3 and abdominal surgery for hernia repair.4,5 Such implants are made from biodegradable (such as magnesium6,7) or inert and bioresistant (such as titanium8 and nitinol9) materials. Titanium membranes prepared by piercing thin foils and woven mono- and multifilament meshes can demonstrate a relatively long period of successful application, but postoperative complications such as infection risk and implant failure are possible.10 As found,11 the use of monofilament meshes and membranes with a small specific surface area can be preferred in clinical practice due to low bacterial colonization and infection risk in contrast to multifilament meshes. However, as claimed in ref (5), metallic membranes can cause tissue lysis, rejection, and other negative effects, which interfere with formation of a strong mesh aponeurosis scar tissue (MAST) complex4 or the “bone/implant” interface.12

Therefore, the problem of biocompatibility enhancement for bioinert titanium membranes is under close consideration by the deposition of different organic and nonorganic materials.5,13 At present, there are two leading strategies of biocompatibility enhancement tha involve the use of organic substances (bone morphogenetic proteins,14 pallet-rich fibrin,15 recombinant human bone morphogenetic proteins/absorbable collagen sponges (rh-BMP/ACS), xenograft bones, and other approaches16) or deposition on metallic membranes of nonorganic materials, e.g., calcium phosphates (Ca–P)17,18 or oxide layers.19

In the earlier presented study,20 Ca–P films (with a thickness of few microns) based on hydroxyapatite (HAp) were prepared on titanium meshes by sol–gel deposition procedure. The obtained coatings with thicknesses of ≈4.0–7.9 μm were annealed at 150 °C. Phase and chemical compositions, morphology, mechanical properties, biocorrosion, and in vitro biocompatibility showed the best performance as a cranioplasty implant for HAp-coated titanium meshes. As an alternative approach, at the same time, HAp nanoparticles ranging from 10 to 60 nm were deposited21 by electrophoresis on the titanium meshes with ultrasonic assistance and the next sintering at 1000 °C for 6 h. In accordance with studied in vivo dog models, enhanced healing of bone defects (such as mandibular fractures) was found using histological evaluations, which detected complete bone regeneration after 6 weeks. The technique, called the “molecular precursor method” with annealing,22 allowed preparing a thin HAp coating with a Ca/P ratio of 1.67, which demonstrated with an in vivo rabbit model an increased bone forming rate compared to the noncoated samples (8.33 ± 1.21 vs 3.43 ± 0.45%, respectively) after 12 weeks. Besides, as reported in another study,23 the membranes in the form of perforated Ti foils were covered by a complex technique that included anodization, cyclic precalcification, and heat treatment. Micro CT and histomorphometric analysis demonstrated better bone healing compared to the untreated samples and induced early bone formation. For all discussed studies, the focus has been on the research of membrane integration in bone tissue, wherein data on a response from the surrounding soft tissues were not fully understood. So, we note the need for experimental in vivo studies of the behavior of the membranes with bioactive coatings in soft tissues. Besides, in some cases, Ca–P one-layer coatings, deposited on metal membranes, do not prevent ion release and debris emission from the surface into a host body. Therefore, it is obvious that it is not possible to enhance the mesh integration in a recipient body using only a one-layer coating strategy, and it is necessary to use complex (combination of coatings) technologies. Thus, nowadays, there is interest in the use of multilayer coatings24−27 for stimulation of the required response and prevention of toxic reactions and implant failure.

In the present study, we used the bilayer strategy, which involved the deposition of the Ca–P/TiO2 layers on the membranes, their heat treatment, and soaking in biopolymeric sodium alginate. The titania layer was prepared by microarc oxidation (MAO),28,29 which is a promising process for the deposition of bioceramic oxide coatings on valve metals. This technique has allowed us to prepare the barrier porous TiO2 (anatase) coating, which can potentially reduce inflammation around tissues.30 Moreover, the prepared surface promotes HAp deposition because of the presence of Ti–OH groups stimulating HAp nucleation.19 Ca–P coatings were obtained by a high-performance procedure of electrophoretic deposition (ED), which also allowed the preparation of a thick and porous Ca–P layer with minimal changes in its chemical and phase composition. Heat treatment may change chemical and phase compositions, crystallinity, mean crystalline size, and other parameters,31 which can influence the biological response in the body.32 Soaking in sodium alginate (SA) was used for formation of a single Ca–P/SA composite layer on the surfaces. As well known,33−36 SA is widely used in medicine due to its antibacterial activity, enhanced wound healing, and other properties. Moreover, SA can prevent the mechanical peeling of the coatings in the recipient body.

The earlier published experimental studies of the biocompatibility of membranes with bioactive coatings have been carried out with in vitro24,25 or a number of in vivo studies. There were experiments with animal models of a critical size defect in the rat cranium23 and defects in the lateral aspect of the rabbit mandible22 and in the inferior border of the dog mandible21 among in vivo studies. We also note that the mentioned papers (with in vivo results) were focused on the histological analysis of novel bone formation at the interface. At the same time, there is a data gap in healing processes in surrounding soft tissues. Obtaining such data is important for the problem of bone regeneration. Moreover, practical applications of metal membranes (not only monofilament meshes) with bioactive phosphate and/or oxide coatings can be used for hernia repair and other problems of abdominal surgery in the future. In this case, in our opinion, experimental studies of biological responses in soft tissues are very important for experimental and clinical medicine. This is why we used an in vivo animal model of subcutaneous implantation in the present work, which can help us to clarify the features of the biological response such as the rate of Ca–P biodegradation, vascularization, parameters of connective tissue capsules, and the presence of inflammation and bacterial infections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Titanium Membranes and HAp Particles

Commercial (Endocarbon, Ltd., Perm, Russia) titanium membranes (see Figure 1, Ti Grade 1) with a pore size of 0.5 mm, a thickness of 0.1 mm, and a specific weight (a membrane mass per its surface area) of ≈1.9·10–2 g/cm2 were used as implant models. Commercial nonstoichiometric HAp (99%) in the form of sphere-like nanoparticles (with a maximal size of 60 nm) was provided by Biteka, Ltd. (Odintsovo, Russia).

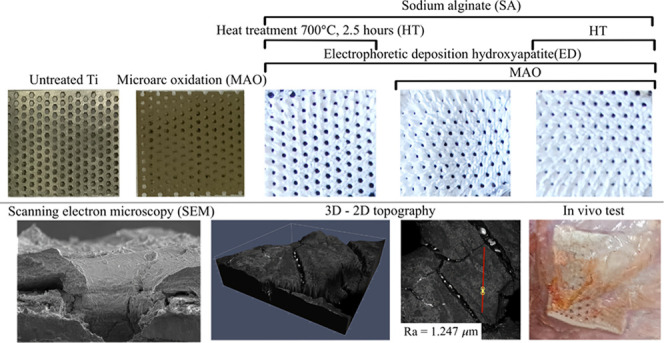

Figure 1.

Untreated titanium membrane and one-layer (MAO and ED + HT + SA) and two-layer (MAO + ED + SA and MAO + ED + HT + SA) coatings.

2.2. Deposition Techniques

The membranes were cut into square samples of ≈1 cm2. The MAO procedure was carried out in a phosphate-based electrolyte containing 1 g/L TiO2, 10 g/L Na3PO4·12H2O, 0.8 g/L Al(OH)3, and 1.5 g/L NaOH at an operating voltage of ≈380 VAC for ≈5 min. After MAO, the coated samples underwent ultrasonic treatment (35 kHz, 100 W) for 20 min. The electrolyte for electrophoresis based on isopropyl alcohol (99.7%) contained ≈20 g/L HAp. Electrophoretic deposition occurred at a DC voltage of 300 V and a current density of ≈16–25 μA/cm2 for ≈1 min. A part of the samples was annealed at 700 °C for 2.5 h. Finally, a part of coated membranes was soaked in 1% sodium alginate with subsequent drying at an ambient temperature. Uncovered membranes and membranes with one-layer TiO2 and HAp prepared by the MAO of electrophoretic deposition were also studied (see Table 1). There were 20 samples of each type.

Table 1. Prepared Samples.

| implant | MAO | electrophoretic deposition | heat treatment | sodium alginate | total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | titanium membrane | – | – | – | – | untreated |

| 2 | + | – | – | – | MAO | |

| 3 | – | + | + | + | ED + HT + SA | |

| 4 | + | + | – | + | MAO + ED + SA | |

| 5 | + | + | + | MAO + ED + HT + SA |

2.3. Coating Characterization

The study of the thermal properties of feedstock HAp particles is important for the estimation of the heat treatment temperature range as well as clarification of their chemical compound. Simultaneous thermal analyses, including differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and thermogravimetry (TGA), were carried out with a Netzsch STA 449F5 within a temperature range of 32–1000 °C (a heat rate of 15 K/min) in an inert nitrogen atmosphere. The initial analyzed mass was ≈7.2099 mg.

The phase composition of the coatings was studied by X-ray diffraction (a DRON-3M diffractometer; Cu Kα radiation, an angular range 2θ of 20–60°, and an angular step size of 0.02°). An interpretation of the obtained X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra was fulfilled with the open-access Crystallography Open Database.37 The recorded spectra allowed us to estimate some parameters of the coatings. The crystallinity of the coating Cr was calculated as follows:38

| 1 |

The crystalline size x002 was calculated with the following Scherrer equation:39

| 2 |

where β002 is the FWHM of the d002 peak and θ002 is its Bragg angle.

The chemical composition was studied by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, a Nicolet-380 spectrometer, a wavelength range of ≈650–4000 cm–1, a step of 2 cm–1). The interpretation of the recorded IR spectra was fulfilled with the published data.40 The morphology of the coatings was visualized by a Quattro scanning electron microscope (SEM, Thermo Fisher Scientific; an energy 5–10 kV, a magnification of ×400–3500). The surface topography and its roughness were measured by a Carl Zeiss AxioImager Z2m microscope equipped with an LSM700 confocal system.

2.4. Calcium Release Test

The calcium release rate was estimated by measuring the concentration of calcium ions in saline. Samples were immersed in 1 mL of solution and kept in an IKA KS 3000 shaker incubator (IKA Werke GmbH & Co., KG, Germany) at 37 °C and a speed of 120 rpm for 7 days. When taking an aliquot, it was replaced with a fresh solution. The concentration of calcium ions in the solution was determined by the colorimetric method with a PE5400UF spectrophotometer (Ekros, Russia) at a wavelength of 570 nm during the formation of a colored complex of calcium ions with the complex of o-cresolphthalein in an alkaline medium using the control (a physiological solution) and calibration (the calcium chloride concentration in the saline was 0.0025 mmol/mL) samples. A calcium concentration (mg) in 1 mL of saline was calculated as follows:

| 3 |

where Esample is the optical density of the sample and Ecalibration_sample is the optical density of the calibration sample.

To determine the initial amount of calcium, the samples with the remaining coating were poured in 1 N hydrochloric acid until the coating was completely dissolved and then neutralized with 1 N NaOH to pH 7. The calcium concentration was measured by the colorimetric method according to the method described above. The initial calcium concentration was calculated as follows:

| 4 |

Here, C1 is the amount of dissolved calcium, mg, and C2 is the amount of calcium in the coating, mg. The percentage ratios of the released in saline and initial (in coating) concentrations of the Ca2+ ions were calculated with eqs 3 and 4 per 1 mm2 of the sample.

2.5. Implantation and In Vivo Biocompatibility Testing

The study of the biological response at the “membrane/soft tissue” interface was carried out with a Wistar rat model (subcutaneous implantation into the adipose tissue of male rats with a mass of ≈250–300 g). The total number of animals was 6. The surgical inventions (see Figure 2) were fulfilled under intramuscular anesthesia with Zoletil (7 mg/kg) and Xylazine (13 mg/kg). The procedure was performed under aseptic conditions. Before the treatment, the surgical field was shaved and sanitized with an antiseptic. An animal was placed on the stomach. An incision was made along the spine. In the hypodermis, five caverns were formed by pushing the tissues apart. The membranes were implanted in these caverns. The implantation period was 30 days. All surgical procedures and keeping animals were performed with the ethical rules for experiments with animals, including the European FELASA Directive 2010/63/EU.

Figure 2.

Implantation details: scheme of implantation (A), surgical caverns after implantation (B), and sample surfaces after autopsy (C).

The morphological study of connective tissue capsules was done as follows: Tissue specimens were fixed in neutral buffered formalin (10%), dehydrated, and paraffin-embedded. Sections (with a thickness of 4 μm) were prepared and stained by hematoxylin–eosin. They were studied with a Leica DM 4000 B LED microscope with a Leica DFC 7000 T camera under brightfield and phase-contrast visualization modes. The maturity of scar tissues around the membranes was evaluated with their thickness and the relative area of blood vessels. High maturity corresponds to minimal inflammation in the low-thickness tissues with a small amount of vessels. The relative areas were measured over three section photographs at a magnification of ×200 and calculated with ImageJ open software taking into consideration the photograph scale. The six experimental dots were obtained for each group. So, the data were presented below on a graph for the average values per animal per implant. The relative area in the field of view was calculated to be a scar tissue area of 105 μm2.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The normality of distributions was checked with the Shapiro–Wilk test. We used the one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s comparison test. The significance level was p ≤ 0.05. The procedure was carried out with Origin Pro 2021 software. The results were presented in terms of mean ± standard error.

3. Results

3.1. Coating Characterization

The obtained DSC-TGA curves are shown in Figure 3. A strong endothermic peak at ≈110 °C indicates the removal of absorbed water from the ultrafine HAp particles. Due to the evaporation of absorbed water, the mass loss is ≈2%. A strong DSC maximum at ≈780 °C can be explained by the rearrangement of [CO3]2– and [HPO4]2– ions. Such processes led to the formation of [PO4]3– groups and gaseous H2O and CO2.31 The total mass loss was ≈9.73%. These chemical transformations at ≈400 °C may be accompanied by partial crystallization of HAp nanoparticles.41 Thus, a temperature of 700 °C was chosen for the annealing of the prepared Ca–P coatings because of the absence of unwanted chemical processes at these conditions.31

Figure 3.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA).

The recorded XRD spectra are presented in Figure 4A. The spectra of the uncovered oxide coatings include the reflexes of crystalline hexagonal titanium (COD ID No. 9016190), tetragonal anatase (COD ID No. 9015929), and rutile (COD ID No. 9015662). In the case of the Ca–P films, their spectra are shown after subtracting the TiO2 and Ti spectra for simplification of the coating quantification. It was found that all major peaks of hexagonal HAp (COD ID No. 9003552) were detected for all samples. No other crystalline phosphates were detected that can be the products of HAp decomposition under deposition and heat post-treatment. A halo within a 2θ range of ≈27–38° testified to the presence of amorphous phosphates in all studied coatings. As found, the XRD spectra of feedstock HAp were similar to those of the deposited unannealed coatings, while the heat treatment was influenced by their parameters. This led to a decreasing of the amorphous halo intensity and amplification of the d300 reflex for the annealed samples. The crystallinity of feedstock HAp and the as-deposited coating, estimated with eq 1, was Cr ≈ 29.9–35.8%. After annealing, the Cr values (see eq 2) increased up to Cr ≈ 40.5–50.0%. The crystalline size depended a little on the heat treatment within XRD accuracy and was x002 ≈ 16.5–22.5 nm for all studied samples. Small recorded differences in the β002 values evidenced this.

Figure 4.

(A) XRD spectra of feedstock HAp (1), TiO2 coating (2), one-layer Ca–P coating after heat treatment (3), and Ca–P/TiO2 bilayers without (4) and after heat treatment (5). (B) FTIR spectra of feedstock HAp (1), Ca–P coating after heat treatment (3), and Ca–P/TiO2 bilayers without (4) and after heat treatment (5).

The obtained FTIR spectra (see Figure 4B) allowed us to clarify the features of physical and chemical transitions in the coatings. Moreover, the main chemical bonds were also detected. As found, the feedstock spectrum included all typical bands of nonstoichiometric apatites.42 The peak at ≈3570 cm–1 corresponded to the symmetric [OH]− stretching vibrations. The presence of the broad-band halo at ≈3500–3000 cm–1 was due to water absorption. The weak absorption at ≈1994 cm–1 was explained by harmonic overtones or combination bands. The presence of the bending modes associated with HAp water was demonstrated by the peak at ≈1630 cm–1. The carbonate [CO3]2– ion caused absorption at ≈1456–1412, ≈1101, and ≈874 cm–1. The bands at ≈1016 and 960 cm–1 evidenced the presence of the [HPO4]2– group. The detection of a strong broad-band peak at ≈1087–1032 cm–1 was caused by the triple degenerate asymmetric stretching mode of the [P–O] bond. For the as-deposited coatings with alginate treatment, all characteristic peaks of HAp were recorded. In this case, the absorption at ≈1456 and ≈1360 cm–1 showed the stretching, bending, and rocking modes due to isopropyl alcohol presence.43 The peaks corresponding to the sodium alginate biopolymer were also found: C–H stretching at ≈2929 cm–1, O–C–O stretching at ≈1612–1412 cm–1, and C–O stretching at ≈1088 cm–144 After annealing, a strong decrease of absorption by alcohol was detected. Moreover, the reduction of the peaks of the [HPO4]2– and [CO3]2– groups was also found.

The SEM images of the prepared chipped samples are presented in Figure 5A at low, medium, and high magnifications. The cross section images of the TiO2 coating on membranes (without alginate treatment) showed that its thickness was ≈13–20 μm. The deposited oxide films had a complex surface (see Figure 5A(a–c)). In the case of the annealed bilayer HAp/TiO2 coating (see Figure 5A(j)), the thickness of the Ca–P layer was about ≈150–200 μm. A lot of extended and deep fractures were detected. The upper layer was composed of feedstock nanoparticles with alginate binding. Generally, the deposited bilayers coated the membranes quite evenly. For the annealed one-layer Ca–P coatings, partial exfoliation of HAp was found (see Figure 5A(d,e)). The coatings also had a friable structure (see Figure 5A(c,f,l)) with micron size external cavities (≈1–10 μm) on their surfaces, which were formed during deposition. No influence of the heat treatment on the upper surface, which was presented by deposited HAp nanoparticles soaked in alginate, was detected. We found that the presence of the intermediated oxide layer led to the reduction of cracking and upper Ca–P film exfoliation; but even so, local avulsions between TiO2 and HAp took place. Mostly, the coating had a more dense structure, but individual fractures and voids were visualized.

Figure 5.

(A) SEM images of the samples at low (a, d, g, j), medium (b, e, h, k), and high (c, f, i, l) magnifications. (B) 3D and 2D topographies of the prepared samples (m–q).

3D topography profiles of the deposited coatings are presented in Figure 5B. No unwanted inclusions were detected in the coatings. The average roughness Ra was estimated along the yellow line (see Figure 5B) with a length of ≈30–60 μm. The surface fractures filled with jelled sodium alginate were visualized for the Ca–P coatings deposited by electrophoresis (see Figure 5B(p,o,q)). For these cases, the measured Ra values were ≈1.247–1.830 μm. The deposited titania coating had close roughness (up to Ra ≈ 1.338 μm). The surface porosity was saved mostly. In the case of the untreated membranes, the roughness was Ra ≈ 0.864 μm.

3.2. Calcium Release Dynamics

The temporal resorption dynamics of the bioactive ceramic coatings on titanium membranes was studied by the measurement of Ca2+ ion release kinetics into physiological solution (see Figure 6). As detected for all coatings, the amount of Ca2+ ions released into the physiological solution was slightly more than 2%/mm2 after 168 h. The statistical significance was estimated over time groups for all studied implants with the Ca–P layer.

Figure 6.

Calcium release dynamics from deposited coatings: ED + HT + SA (green), MAO + ED + SA (blue), and MAO + ED + HT + SA (red). Statistically significant results are indicated by an asterisk (n = 8 per implant group; p* ≤ 0.05).

We discovered that statistically significant results for Ca2+ release rates were found for ED + HT + SA (0.893 ± 0.010%/mm2) and MAO + ED + SA (1.095 ± 0.032%/mm2) at 1 h and for all prepared coatings, namely, ED + HT + SA (1.890 ± 0.022%/mm2), MAO + ED + SA (1.631 ± 0.042%/mm2), and MAO+ED+HT+SA (1.364 ± 0.025%/mm2) at 72 h after immersion in saline. So, this in general proved the influence of heat treatment and the presence of the intermediate oxide layer on the efficiency of resorption dynamics. At a late stage (168 h after immersion), similar trends persisted. The maximum Ca2+ release rate (2.182 ± 0.031%/mm2) was recorded for ED + HT + SA coatings without an intermediate oxide layer. In the case of the presence of the titania layer (MAO+ED+SA coating), the rate value was 2.124 ± 0.022%/mm2. The minimum release rate was up to 2.042 ± 0.058%/mm2 for MAO + ED + HT + SA coatings. However, the accepted statistical significance was not achieved for this time group.

3.3. Histological Analyses

The implant photographs in surrounding soft tissues are presented in Figure 2 after harvesting. No signs of bacterial infections and suppuration were discovered for all samples. As found for untreated control membranes, immature and relatively thin tissue capsules were formed, and poor vascularization and inflammatory infiltration were found. Fibrosis and moderate vascularization were observed in surrounding adipose tissues. Deposition of coatings changed the pictures of processes in tissues. In the case of MAO, relatively thin connective tissue capsules with moderate vascularization were formed. As discovered for ED + HT + SA coatings, immature loose connective capsules with an irregular thickness were discovered. Significant peeling and clumping of the Ca–P layer were found. In the case of MAO + ED + SA, we found immature connective tissue capsules of a loose structure with moderate vascularization and coating clumping. Meanwhile, there is not any visible sign of sufficient coating crumbling, and very thin and mature connective tissue capsules were formed with minimal vascularization for MAO + ED + HT + SA systems. The presented data were confirmed by histology and histomorphometry.

Images of the slide preparations are presented in Figure 7. Here, lymphocytes and macrophages are indicated by blue arrows, and giant cells are indicated by green arrows. Sharp symbols were used for the demonstration of individual fragments of nonresorbable HAp. All areas of detected objects were calculated per 105 μm2 of the capsule area. Immature and relatively thin connective tissue capsules (157.1 ± 5.1 μm) were formed and consisted of loosely arranged collagen fibers and numerous fibroblasts between them for untreated membranes (see Figure 7a). Poor vascularization and inflammatory infiltration (lymphocytes and macrophages) were noted. Fibrosis and moderate vascularization were found in surrounding adipose tissue. The deposited coatings influenced the biological response in rats.

Figure 7.

Section photographs for the studied samples with an indication of lymphocytes and macrophages (blue arrows), giant cells (green arrows), and nonresorbable HAp (sharps): untreated membranes (a), MAO (b), ED + HT + SA (c), MAO + ED + SA (d), and MAO + ED + HT + SA (e).

In the case of a one-layer titania coating prepared by MAO (see Figure 7b), relatively thin connective tissue capsules (171.2 ± 8.2 μm) were formed with varying degrees of maturity and moderate vascularization and inflammatory infiltration. Collagen fibers were mainly located loosely, which was typical for less mature connective tissue. Collagen fibers were arranged quite tightly in separate small areas. Fibrosis and marked vascularization were noted in the surrounding subcutaneous adipose tissue.

As shown for all samples with annealed Ca–P one-layer coatings (case ED + HT + SA, see Figure 7c), immature and thick loose connective tissue capsules (372.9 ± 12.4 μm) were formed with moderate vascularization and pronounced inflammatory infiltration (7.1 times higher than control values). The tissue capsule contained a significant amount of resorbing HAp particles (with a relative area of 29580.8 ± 3131.0). The HAp granules were stained basophilically and looked like finely grained and vacuolated amorphous deposits. Each of the granules was surrounded by thin connective tissue microcapsules consisting of multinucleated giant cells, macrophages, fibroblasts, and circularly arranged collagen fibers. HAp granules were replaced by connective tissue, as they were dissolved. No significant morphological changes were found in the surrounding tissues (adipose tissue, muscles, fascia), and inflammatory infiltration was weak. Only pronounced vascularization of adipose tissue was noted.

As found for most of the samples with the bilayer (Ca–P/TiO2) coating without the heat treatment (case MAO + ED + SA, see Figure 7d), immature connective tissue capsules with a medium thickness (236.6 ± 8.7 μm) and a relatively loose structure, moderate vascularization, and poor inflammatory infiltration were formed. We found capsules with resorbable HAP particles for all samples, but a resorption efficiency was different. No significant morphological changes were found in the surrounding tissues.

In the case of the annealed bilayer (Ca–P/TiO2) coating (case MAO + ED + HT + SA, see Figure 7e), very thin and mature connective tissue capsules (32.3 ± 1.3 μm), consisting of tightly packed collagen fibers and a few fibroblasts between them (1.9 times less than that in control and other cases), were found. Poor vascularization and inflammatory infiltration were detected. At the same time, a few HAp particles in the composition of capsules were rarely visualized without significant morphological changes in the surrounding tissues.

Figure 8 presents the distribution of relative (per 105 μm2 of the capsule area) vessel areas per animal per implant group compared to the untreated membranes. In the case of untreated Ti membranes, the relative area was 355.47 ± 81.03. The statistically significant values were found for MAO (3395.12 ± 509.65), ED + HT + SA (3162.62 ± 552.28), and MAO + ED + SA (2464.80 ± 551.61) coatings. So, the tissues around MAO were distinguished by extremely pronounced vascularization. The deposition of Ca–P and titania layers decreased the rate of vessel growth. MAO + ED + HT + SA had a relative vessel area of 2101.38 ± 307.77, but the required significance level with a comparison with the untreated membranes was not achieved. The histological images with indicated vessels are presented in the Supporting Information section.

Figure 8.

Relative vessel area in tissues around implants. Statistically significant results are indicated by an asterisk (n = 6 per implant group; p* ≤ 0.05).

4. Discussion

First, we must discuss the difference between gums/gingival and subcutaneous tissues to justify the applicability of our model. Gums/gingival tissue has a two-layer structure. The outer keratinized layer performs protective functions, and the inner connective layer serves for wound repair. The total thickness is 1.89–3.71 mm.45 On the other hand, subcutaneous adipose tissues are characterized by a greater thickness (up to 10 mm46) and perform a number of functions such as thermoregulation, secretion of mediators, inflammatory cytokines, lipogenesis, and other processes.47 As found earlier,48 wound healing is different in gums/gingival and subcutaneous tissues due to differences in mesenchymal stromal cells and their activity. Biological causes are associated with high values of cell proliferation and migration rates for gums/gingival epithelium in comparison with adipose tissue. Besides, the trend of the adipose matrix to contraction leads to the formation of scars for deep wounds around implants. Second, notwithstanding the above, we assume that our studies are relevant and provide novel data on the integration of titanium membranes with bioactive coatings in the host. The design of preclinical testing involving subcutaneous implantation of a material in small laboratory animals is a common practice in studies of biological safety or reactions.49 Unlike implantation under the small size oral mucosa of rodents, subcutaneous implantation allows us to study much larger fragments of the test material. This will more reliably demonstrate the negative properties of the material, if any. In addition, when implanted into the oral cavity, the diet of a laboratory animal is disturbed, which can lead to the distortion of the results. The risks for the formation of bedsores or tissue rupture are disproportionately less for subcutaneous implantation, since the tissue mobility is higher. Testing a material with implantation in the oral cavern and integration in bones is reasonable only at the last stages of preclinical studies when studying a full-size device on large laboratory animals (such as pigs). Besides, implantation in adipose tissue can be relevant for the tasks of abdominal surgery.

Obtaining complex data on the integration of the implants in the adipose tissue of the rats has allowed us to highlight some relations between the coating properties, their preparation procedure, and the biological response in the recipients. First, no toxic components were registered in the coating by such techniques as XRD and FTIR (see Figure 4). The MAO technique allows us to deposit the coatings based on such titania phases as anatase and rutile, which are typical for such processing types.50 As reported earlier,31 some procedures of Ca–P deposition with sufficient heat loads in initial HAp (e.g., powder plasma spraying51) can stimulate a few unwanted phase transformations that take place above 1570 °C. In our case, electrophoretic deposition was not accompanied by significant heating of the forming coating and hence phase and chemical transitions. We note that our approach suppressed CaTiO3 formation due to the presence of the TiO2 layer. As found,52 CaTiO3 films are formed at plasma spray, and they can stimulate slight inflammation but without severe responses. Figure 3 shows that the heat post-treatment (at 700 °C) could lead to only the removal of absorbed water from HAp and activation of the irreversible transformation of the [HPO4]2– and [CO3]2– ions into the [PO4]3– ion and gaseous CO2 and H2O. Data on FTIR spectra also evidenced the decrease of the [HPO4]2– group content after annealing. Such heat processes could shift the Ca/P ratio to the values typical for stoichiometric HAp.53 Moreover, DSC/TGA analysis and XRD showed that the heat treatment also increased the crystallinity (from ≈29.9 to 35.8% up to ≈40.5 to 50.0%) without a significant change in the crystallite size. The presence of jelled sodium alginate was also confirmed by FTIR.

Second, deposition procedures promoted surface development and increased the roughness from 0.864 μm (for the original membranes) to 1.338 μm (titania coatings) and ≈1.247 to 1.830 μm (for Ca-P coatings). We found two types of pores: large pores (with a size of 0.5 mm) perforating the membranes and tiny cavities (≈1 to 10 μm) on Ca–P or titania layers. The first ones were not fully covered and clogged after treatment (see Figure 1), but their longitude size somewhat decreased for the cases of Ca–P coatings. MAO treatment did not change this significantly. The cavities were formed during coating deposition. Mostly, the surface characteristics (such as roughness, porosity, and other parameters) were the same as for coatings deposited by MAO and electrophoresis and reported earlier.28,54

For other reported techniques of HAp/TiO2 bilayers preparation,26,27 a conclusion about their biocompatibility was made with in vitro tests (estimation of bone-like HAp nucleation and study of mitochondrial activity). In these experiments, Ti discs, sheets, and cylinders (not membranes) were used as substrates. The indicated procedures were based on MOCVD/the spray pyrolysis process26 or titania electrodeposition/HAp electrophoresis deposition27 and demonstrated enhanced bioactivity due to the decreased ion release and improved electrochemical properties. These studies also demonstrated the important role of heat post-treatment in preparing the coatings with adequate crystallinity. It was shown that low crystallinity could stimulate the dissolution of Ca–P coatings.32 In this study, the solubility of MAO + ED + HT + SA coatings was a little lower than those of MAO + ED + SA and ED + HT + SA coatings (see Figure 7). We associate this with the heat treatment after deposition, which increased crystallinity and led to precrystallization: the amount of highly resorbable calcium phosphate phases (e.g., calcium-deficient, carbonate-substituted hydroxyapatite) decreased. It was evidenced by the decrease of the intensity of the [CO3]2– and [HPO4]2– groups on IR spectra and data on DSC/TGA analysis of the feedstock powder.

The histological analysis of the sections showed that the coating type, annealing, and resulting changes significantly influenced histological images in tissues surrounding the implants. In the case of bioinert untreated membranes, the response was weak, which was expressed in the formation of immature thin capsules with poor vascularization. At the same time, fibrosis and moderate vascularization of the surrounding adipose tissue were observed. Deposition of coatings changed the response feature. MAO coatings earlier demonstrated in vivo enhanced integration in bone tissue28 due to porous and rough surface topography, promoting the nucleation of HAp.55 Soft tissue integration for disc implants with sol–gel-obtained TiO2 coatings was studied with the rat in vivo model.56 The connective tissue capsules around them in the early stages of implantation (after 2 days of implantation) were found. As in our experiments, relatively thin and mostly immature connective tissue capsules with a little amount of fibers were formed. The authors also noted a poor response for uncovered commercial pure Ti implants. We detected fibrosis and pronounced vascularization for the surrounding adipose tissue, and, as a result, a large vessel area of 3395.12 ± 509.65 was observed in the capsule. As noted,57,58 Ca–P materials can stimulate not only implant integration in bones but also soft tissue repair (skin regeneration, periodontal tissue healing) due to the affinity between HAp and collagen, providing collagen formation without unwanted effects. In our case of the annealed one-layer HAp coating, maximal Ca2+ release (2.182 ± 0.031%/mm2) was detected, and a lot of resorbed HAp particles were visualized in the section photographs. The shedding of the coating was caused by the absence of an intermediate oxide layer that could enhance Ca–P adhesion to the membrane. Immature loose capsules of uneven thickness with moderate vascularization and pronounced lymphocyte and macrophage infiltration were formed around the implants. At the same time, the vessel area was also large (3162.62 ± 552.28) due to pronounced vascularization in the surrounding tissues.

In the case of the bilayer coatings, the response features and vessel area changed significantly. For the unannealed bilayers, the Ca2+ release rate was 2.124 ± 0.022%/mm2. As found with histological studies, rather thin and mostly immature loose connective tissue capsules with moderate vascularization and poor lymphocyte and macrophage infiltration were formed around the implants. We found moderate vascularization (2464.80 ± 551.61), and the capsules with a few resorbable HAp fragments were noted. No significant morphological changes were detected in the surrounding tissues.

In our opinion, the best route for the sample preparation was MAO + ED + HT + SA, for which the Ca2+ realize rate was 2.042 ± 0.058%/mm2. For such coatings, very thin and mature dense connective tissue capsules with minimal inflammatory infiltration were visualized. HAp fragments in the composition of capsules were rarely detected. No significant morphological changes were found in the surrounding tissues. Sufficiently moderate vascularization took place at the level of 2101.38 ± 307.77.

5. Conclusions

Titanium membranes and meshes are widely used in dentistry and maxillofacial and abdominal surgery, but there is a risk of their rejection. We presented a strategy involving the use of bioactive HAp and/or titania coatings on membranes, which can stimulate implant integration in recipient soft tissues and neutralize unwanted biological reactions, including pronounced inflammation infiltration, infections, and rejection. As found, the best treatment procedure was MAO followed by electrophoretic deposition with annealing and soaking in sodium alginate. In this case, the heat treatment increased the coating crystallinity from 29.9–35.8% up to 40.5–50.0% and stimulated a rearrangement in feedstock nonstoichiometric HAp with the removal of CO2 and H2O from the substitute ions. This led to a solubility rate up to 2.042 ± 0.058%/mm2 at 168 h after implantation. In this case, the thinnest mature capsules with a relative vessel area of 2101.38 ± 307.77 and poor vascularization and inflammation infiltration were formed without unwanted changes in the tissues. Despite the lack of data on integration in bone tissue, the obtained data will be useful for understanding the processes in soft tissues around the implants and for quantitative and qualitative assessment of the biological safety of the deposited coatings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank N.B.S. for histological observations in I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University and are grateful to L.L.B.-A., Smolencev D.V. for a consultation on Micro CT analyses in Priorov National Medical Research Center of Traumatology and Orthopedics, to P.A.T. for a consultation on TGA and DSC, coating preparation, and statistical analysis, and to E.V.V. for the microscopic studies of the coatings. This study was partly supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project 20-79-10190).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c05718.

Typical histological images with indicated vessels around implants (Figure S1) (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors: methodology (A.S.S. and P.A.T.), coating preparation (A.S.S., P.A.T., and V.R.V.), coating characterization and analysis (P.A.T, V.R.V., and E.V.V.), surgical procedure (Y.S.L. and L.L.B.-A.), histological study (N.B.S.), statistical analysis (P.A.T.), project administration (A.V.S), and writing and editing (all authors). All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project 20-79-10190).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aprile P.; Letourneur D.; Simon-Yarza T. Membranes for Guided Bone Regeneration: A Road from Bench to Bedside. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2020, 9, 2000707 10.1002/adhm.202000707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriou R.; Mataliotakis G. I.; Calori G. M.; Giannoudis P. V. The role of barrier membranes for guided bone regeneration and restoration of large bone defects: Current experimental and clinical evidence. BMC Med. 2012, 10, 81 10.1186/1741-7015-10-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledano-Osorio M.; Manzano-Moreno F. J.; Ruiz C.; Toledano M.; Osorio R. Testing active membranes for bone regeneration: A review.. J. Dent. 2021, 105, 103580 10.1016/j.jdent.2021.103580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See C. W.; Kim T.; Zhu D. Hernia Mesh and Hernia Repair: A Review. Eng. Regener. 2020, 1, 19–33. 10.1016/j.engreg.2020.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baylón K.; Rodríguez-Camarillo P.; Elías-Zúñiga A.; Díaz-Elizondo J. A.; Gilkerson R.; Lozano K. Past, present and future of surgical meshes: A review. Membranes 2017, 7, 47 10.3390/membranes7030047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.; Jang Y.-S.; Lee M.-H. Enhancement of Bone Regeneration on Calcium-Phosphate-Coated Magnesium Mesh: Using the Rat Calvarial Model. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 652334 10.3389/fbioe.2021.652334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.; Jang Y.-S.; Kim Y.-K.; Kim S.-Y.; Ko S.-O.; Lee M.-H. Surface modification of pure magnesium mesh for guided bone regeneration: In vivo evaluation of rat calvarial defect. Materials 2019, 12, 2684 10.3390/ma12172684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakhmatia Y. D.; Ayukawa Y.; Furuhashi A.; Koyano K. Current barrier membranes: Titanium mesh and other membranes for guided bone regeneration in dental applications. J. Prosthodontics Res. 2013, 57, 3–14. 10.1016/j.jpor.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etminanfar M. R.; Khalil-Allafi J.; Montaseri A.; Vatankhah-Barenji R. Endothelialization and the bioactivity of Ca-P coatings of different Ca/P stoichiometry electrodeposited on the Nitinol superelastic alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2016, 62, 28–35. 10.1016/j.msec.2016.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Her S.; Kang T.; Fien M. J. Titanium mesh as an alternative to a membrane for ridge augmentation. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 70, 803–810. 10.1016/j.joms.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters J. C.; Fitzgerald M. P.; Barber M. D. The use of synthetic mesh in female pelvic reconstructive surgery. BJU Int. 2006, 98, 70–76. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X.; Fraulob M.; Haïat G. Biomechanical behaviours of the bone-implant interface: A review. J. R. Soc., Interface 2019, 16, 20190259 10.1098/rsif.2019.0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon S.-M.; Sufaru I.-G.; Teslaru S.; Ghiciuc C. M.; Stafie C. S. Finding the Perfect Membrane: Current Knowledge on Barrier Membranes in Regenerative Procedures: A Descriptive Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1042 10.3390/app12031042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herford A. S.; Lowe I.; Jung P. Titanium mesh grafting combined with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 for alveolar reconstruction. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. North Am. 2019, 31, 309–315. 10.1016/j.coms.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanaati S.; Al-Maawi S.; Conrad T.; Lorenz J.; Rössler R.; Sader R. Biomaterial-based bone regeneration and soft tissue management of the individualized 3D-titanium mesh: An alternative concept to autologous transplantation and flap mobilization. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 47, 1633–1644. 10.1016/j.jcms.2019.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y.; Li S.; Zhang T.; Wang C.; Cai X. Titanium mesh for bone augmentation in oral implantology: current application and progress. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 12, 37 10.1038/s41368-020-00107-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorozhkin S. V. Calcium orthophosphate deposits: Preparation, properties and biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2015, 55, 272–326. 10.1016/j.msec.2015.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorozhkin S. V. Synthetic amorphous calcium phosphates (ACPs): Preparation, structure, properties, and biomedical applications. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 7748–7798. 10.1039/d1bm01239h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.-M.; Hayakawa S.; Tsuru K.; Osaka A. Low-temperature preparation of anatase and rutile layers on titanium substrates and their ability to induce in vitro apatite deposition. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2004, 87, 1635–1642. 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2004.01635.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naderi A.; Zhang B.; Belgodere J. A.; Sunder K.; Palardy G. Improved Biocompatible, Flexible Mesh Composites for Implant Applications via Hydroxyapatite Coating with Potential for 3-Dimensional Extracellular Matrix Network and Bone Regeneration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 26824–26840. 10.1021/acsami.1c09034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzat A. M.; Khalil A.A.F.; El-Dibany R. M.; Khalil N. M. The use of titanium mesh coated with hydroxyapatite in mandibular fracture (Experimental study). Alexandria Dent. J. 2017, 42, 92–97. 10.21608/adjalexu.2017.57864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno D.; Sato M.; Hayakama T. Guided Bone Regeneration using Hydroxyapatite-Coated Titanium Fiber Web in Rabbit Mandible: Use of Molecular Precursor Method. J. Hard Tissue Biol. 2013, 22, 329–336. 10.2485/jhtb.22.329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y.-S.; Moon S.-H.; Thi Nguen T.-D.; et al. In vivo bone regeneration by differently designed titanium membrane with or without surface treatment: a study in rat calvarial defects. J. Tissue Eng. 2019, 10, 204173141983146 10.1177/2041731419831466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P.; Li Y.; Kwok T.; Yang T.; Liu C.; Li W.; Zhang X. A bi-layered membrane with micro-nano bioactive glass for guided bone regeneration. Colloids Surf., B 2021, 205, 111886 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.111886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos V. I.; Merlini C.; Aragones Á.; Cesca K.; Fredel M. C. In vitro evaluation of bilayer membranes of PLGA/hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate for guided bone regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2020, 112, 110849 10.1016/j.msec.2020.110849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visentin F.; El Habra N.; Fabrizio M.; Brianese N.; Gerbasi R.; Nodari L.; Zin V.; Galenda A. TiO2-HA bi-layer coatings for improving the bioactivity and service-life of Ti dental implants. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 378, 125049 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2019.125049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rath P. C.; Besra L.; Singh B. P.; Bhattacharjee S. Titania/hydroxyapatite bi-layer coating on Ti metal by electrophoretic deposition: Characterization and corrosion studies. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, 3209–3216. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2011.12.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Xu H.; Zhao B.; Jiang S. Accelerated and enhanced osteointegration of MAO-treated implants: histological and histomorphometric evaluation in a rabbit model. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 10, 11 10.1038/s41368-018-0008-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsygankov P. A.; Skryabin A. S.; Krikorov A. A.; Chelmodeev R. I.; Vesnin V. R.; Parada-Becerra F. F. Formation of a combined bioceramics layer on titanium implants. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2019, 1386, 012011 10.1088/1742-6596/1386/1/012011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H.; Yang Y.; Yu L.; Liu K.; Fei Y.; Guo Ch.; Zhou Y.; Hu J.; Shi L.; Ji H. Inhibition of Inflammatory Response and Promotion of Osteogenic Activity of Zinc-Doped Micro-Arc Titanium Oxide Coatings. ACS Omega. 2022, 7, 14920–14932. 10.1021/acsomega.2c00579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demnati I.; Grossin D.; Combes C.; Rey C. Plasma-Sprayed apatite Coatings: Review of physical-chemical characteristics and their biological consequences. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 2014, 34, 1–7. 10.5405/jmbe.1459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W.; Tao S.; Liu X.; Zheng X.; Ding C. In vivo evaluation of plasma sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings having different crystallinity. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 415–421. 10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00545-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salimi E. Development of bioactive sodium alginate/sulfonated polyether ether ketone/hydroxyapatite nanocomposites: Synthesis and in-vitro studies. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 267, 118236 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Liu Ch.; Sun J.; Lv Sh. Bioactive edible sodium alginate films incorporated with tannic acid as antimicrobial and antioxidative food packing. Foods 2022, 11, 3044 10.3390/foods11193044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Łabowska M. B.; Cierluk K.; Jankowska A. M.; Kulbacka J.; Detyna J.; Michalak I. A Review on the Adaption of Alginate-Gelatin Hydrogels for 3D Cultures and Bioprinting. Materials 2021, 14, 858 10.3390/ma14040858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aderibigbe B. A.; Buyana B. Alginate in Wound Dressings. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 42 10.3390/pharmaceutics10020042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- https://www.crystallography.net/cod (accessed October 30, 2022).

- Khor K. A.; Cheang P. Plasma sprayed hydroxyapatite(HA) coatings produced with flame spheroidised powders. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 1997, 63, 271–276. 10.1016/S0924-0136(96)02634-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Gasga J.; Martínez-Piñeiro E. L.; Rodríguez-Álvarez G.; Tiznado-Orozco G. E.; García-García R.; Brès E. F. XRD and FTIR crystallinity indices in sound human tooth enamel and synthetic hydroxyapatite. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2013, 33, 4568–4574. 10.1016/j.msec.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsopoulos S. Synthesis and characterization of hydroxyapatite crystals: A review study on the analytical methods. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2002, 62, 600–612. 10.1002/jbm.10280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneha M.; Sundaram N. M. Preparation and characterization of an iron oxide-hydroxyapatite nanocomposite for potential bone cancer therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 99–106. 10.2147/IJN.S79985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combes C.; Cazalbou S.; Rey C. Apatite biominerals. Minerals 2016, 6, 34 10.3390/min6020034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahravan A.; Desai T.; Matsoukas T. Controlled manipulation of wetting characteristics of nanoparticles with dry-based plasma polymerization method. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 251603 10.1063/1.4772544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helmiyati; Aprilliza M. Characterization and properties of sodium alginate from brown algae used as an ecofriendly superabsorbent. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 188, 012019 10.1088/1757-899X/188/1/012019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolte R.; Kolte A.; Mahajan A. Assessment of gingival thickness with regards to age, gender and arch location. J. Indian. Soc. Periodontol. 2014, 18, 478–481. 10.4103/0972-124X.138699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Störchle P.; Müller W.; Sengeis M.; Lackner S.; Holasek S.; Fürhaper-Rieger A. Measurement of mean subcutaneous fat thickness: eight standardised ultrasound sites compared to 216 randomly selected sites. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16268 10.1038/s41598-018-34213-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard A. J.; White U.; Elks C. M.; Stephens J. M.. Adipose Tissue: Physiology to Metabolic Dysfunction. In Endotext, Internet; Feingold K. R.; Anawalt B.; Boyce A.; Feingold K. R.; Chrousos G.; Herder W.W.d.; Dhatariya K.; Dungan K.; Gross- man A.; Hershman J. M.; Hofland J., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth (MA), 2000. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555602/ (Updated April 4, 2020) (accessed October 30, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Boink M. A.; van den Broek L. J.; Roffel S.; Nazmi K.; Bolscher J. G.; Gefen A.; Veerman E. C.; Gibbs S. Different wound healing properties of dermis, adipose, and gingiva mesenchymal stromal cells. Wound Repair Regener. 2016, 24, 100–109. 10.1111/wrr.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal B.; Fernandez F. B.; Babu S. S.; Harikrishnan V. S.; Varma H.; John A. Adipogenesis on biphasic calcium phosphate using rat adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells: in vitro and in vivo. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 2012, 100, 1427–1437. 10.1002/jbm.a.34082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G.-W.; Chen J.-S.; Tseng W.; Lu F.-H. Formation of anatase TiO2 coatings by plasma electrolytic oxidation for photocatalytic applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 357, 28–35. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2018.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tejero-Martin D.; Rezvani; Rad M.; McDonald A.; Hussain T. Beyond Traditional Coatings: A Review on Thermal-Sprayed Functional and Smart Coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2019, 28, 598–644. 10.1007/s11666-019-00857-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsu N.; Sato K.; Yanagawa A.; Saito K.; Imai Y.; Kohgo T.; Yokoyama A.; Asami K.; Hanawa T. CaTiO3 coating on titanium for biomaterial application - Optimum thickness and tissue response. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 2017, 82, 304–315. 10.1002/jbm.a.31136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skryabin A. S.; Tsygankov P. A.; Vesnin V. R.; Parshin B. A.; Zaitsev V. V.; Lukina Y. S. Physicochemical Properties and Osseointegration of Titanium Implants with Bioactive Calcium Phosphate Coatings Produced by Detonation Spraying. Inorg. Mater. 2022, 58, 71–77. 10.1134/S0020168522010113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan L.; Durgalakshmi D.; Geetha M.; Sankara Narayanan T.S.N.; Asokamani R. Electrophoretic deposition of nanocomposite (HAp+TiO2) on titanium alloy for biomedical applications. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, 3435–3443. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2011.12.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A.-M.; Lenin P.; Zeng R.-Ch.; Bobby Kannan M. Advances in hydroxyapatite coatings on biodegradable magnesium and its alloys. J. Magnesium Alloys 2022, 10, 1154–1170. 10.1016/j.jma.2022.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Areva S.; Paldan H.; Peltola T.; Närhi T.; Jokinen M.; Lindén M. Use of sol-gel-derived titania coating for direct soft tissue attachment. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 2004, 70A, 169–178. 10.1002/jbm.a.20120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni E.; Iaquinta M. R.; Lanzillotti C.; Mazziotta C.; Maritati M.; Montesi M.; Sprio S.; Tampieri A.; Tognon M.; Martini F. Bioactive Materials for Soft Tissue Repair. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 613787 10.3389/fbioe.2021.613787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson A.; Andersson M.; Wigren S.; Pivodic A.; Flynn M.; Nannmark U. Soft Tissue Integration of Hydroxyapatite-Coated Abutments for Bone Conduction Implants. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2015, 17, e730–e735. 10.1111/cid.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.