Abstract

Background

The prognostic implication of liver fibrosis in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients are scarce. We sought to evaluate whether liver fibrosis scores (LFS) were associated with thrombotic or bleeding events in patients with acute coronary syndrome.

Methods

We included 6386 ACS patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). This study determined liver fibrosis with aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI), aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio (AST/ALT ratio), Forns score, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score (NFS). The primary endpoint was major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), a composite of all-cause mortality (ACM), myocardial infarction (MI), and ischemic stroke (IS).

Results

During the follow-up, 259 (4.06%) MACCE and 190 (2.98%) bleeding events were recorded. As a continuous variable or a categorical variable stratified by the literature-based cutoff, LFS was positively associated with MACCE (p > 0.05) but not with bleeding events. Compared with subjects with low APRI scores, AST/ALT ratio scores, Forns scores, and NFS scores, subjects with high scores had a 1.57- to 3.73-fold increase risk of MACCE after adjustment (all p < 0.05). The positive relationship between LFS and MACCE was consistent in different subgroups.

Conclusions

In ACS patients, increased LFS predicted an elevated risk of thrombotic events but not bleeding. LFS may contribute to thrombotic risk stratification after ACS.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12959-022-00441-8.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome, Liver fibrosis, Thrombotic events, Bleeding events, Risk stratification

Background

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is one of the leading causes of death worldwide [1]. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), one of the most widely used therapeutic strategies for ACS patients, could improve patient outcomes. However, the risk of thrombotic and bleeding events after PCI remains high and may affect prognosis. The thrombotic and bleeding tradeoff is critical for the ACS patients. Therefore, exploring potential factors affecting thrombotic or bleeding events of ACS is meaningful in clinical management.

The global burden of chronic liver diseases is increasing rapidly. It is estimated that 1.5 billion people worldwide suffer from chronic liver diseases, and more than 2 million people die yearly [2]. Chronic injury in patients with chronic liver disease results in abnormal hepatic collagen increase and excessive extracellular matrix deposition in the liver, leading to liver fibrosis [3]. Liver fibrosis might silently exist in up to 9% of the general population [4]. Recent studies revealed that liver fibrosis was associated with coronary calcification and the severity of coronary artery diseases [5–7]. However, the relationship between liver fibrosis and adverse outcomes in ACS patients has been barely investigated.

The gold standard for liver fibrosis diagnosis is liver biopsy, an invasive procedure with a risk of complications [8]. High cost and sample variability also make liver biopsy unsuitable for routine population screening [9]. With the increasing burden of liver fibrosis and the need for simple evaluation tools, the liver fibrosis scores (LFS) calculated from clinical parameters and blood tests for predicting the severity of liver fibrosis were established and considered an alternative evaluation tool [10]. Compared with liver biopsy, LFS is simple, economical, non-invasive, and could be widely used in screening [11]. Commonly used LFS include the aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI), Forns score, aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio (AST/ALT ratio) [12–14], and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score (NFS) [15]. In this study, we aimed to investigate whether LFS (e.g., APRI, AST/ALT ratio, Forns score, NFS) were associated with thrombotic and bleeding events in patients with ACS.

Methods

Study population

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Fuwai Hospital. This study is an observational cohort study. Participants enrolled in this study have signed informed consent forms. From January to December 2013, a total of 10,724 patients who underwent PCI in Fuwai hospital were screened. The eligibility criteria are listed as the following: (1) ACS patients underwent PCI in Fuwai hospital, including patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and patients with unstable angina (UA); (2) patients over 18 years old. The exclusion criteria are (1) patients with incomplete clinical information or incomplete follow-up; (2) patients lacking data on liver function, platelet count, and biochemical tests. Finally, 6386 ACS patients who underwent PCI in Fuwai hospital were enrolled in our study. Baseline demographic data, clinical data, and procedural data were collected prospectively. Before the procedure, patients were administered a loading dose of 300 mg aspirin and a loading dose of 300 mg clopidogrel or a loading dose of 180 mg ticagrelor. After the procedure, patients were administered lifelong aspirin and clopidogrel or ticagrelor for 12 months. Medical equipment use is at the cardiologist’s discretion based on the patient’s condition.

Liver fibrosis scores

This study evaluated APRI, AST/ALT ratio, Forns score, and NFS. These scores were calculated as the following formula:

APRI = AST (IU/L)/AST (the upper limit of normal, ULN) × 100 / platelet count (10^9/L)

AST/ALT ratio = AST (IU/L)/ALT (IU/L)

Forns score = 7.811–3.131 × log (platelet count [10^9/L]) + 0.781 × log (GGT [IU/L]) + 3.467 × log (age [year]) –0.014 × total cholesterol (mg/dL)

NFS = − 1.675 + (0.037 × age [years]) + (0.094 * BMI [Kg/m2]) + (1.13 × diabetes [yes = 1, no = 0]) + (0.99 × AST/ALT ratio) – (0.013 × platelet count [109/L]) – (0.66 × albumin [g/dL])

Based on the cutoff values of previous literature, we divided LFS into low, intermediate, and high scores, indicative of mild, moderate, and advanced liver fibrosis. The cutoff values of APRI were 0.5 and 1.5 [12]. The cutoff values of Forns score were 4.2 and 6.9 [13]. The cutoff values of NFS were − 1.455 and 0.676 [15]. The cutoff values of the AST/ALT ratio were 0.8 and 2 [16, 17].

Follow-up and endpoints

The patients were followed up after the procedure through telephone or outpatient clinics by professional staff for 30 days, 6 months, and every year after that. Major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), composed of all-cause death, myocardial infarction (MI), and ischemic stroke, were primary endpoint. The secondary endpoints were the components of MACCE separately, major bleeding, target vessel revascularization (TVR), and stent thrombosis. The definition of endpoints is according to the academic research consortium (ARC) and bleeding academic research consortium (BARC). All-cause death is caused by any causes. Cardiac death is caused by MI, congestive heart failure, malignant arrhythmia, or other direct cardiac causes. MI is defined according to the universal definition of myocardial infarction (UDMI). Ischemic stroke refers to the neurological dysfunction caused by ischemia of brain tissue and cells. Major bleeding refers to grade 2–5, based on the BARC definition [18].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables as count and percentage. Continuous variables were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA), and categorical variables were compared by the chi-square test. Unadjusted outcomes rates were estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis and compared with the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to assess the association between LFS and clinical outcomes and recorded as hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CIs). Variables with p < 0.1 in univariable Cox regression analysis (Supplementary Table 1) and clinically relevant variables were used as adjusted variables. Variables included in the adjustment were shown in the following: age, sex, BMI, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, previous PCI, previous cerebrovascular disease, left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF less than 50%), lesion number, and high-sensitive C reactive protein levels. Analytic components of LFS were not adjusted in the multivariable analysis. Restricted cubic splines were used to evaluate the correlation between continuous LFS and outcomes. Patients were divided into subgroups according to age (< 60 and ≥ 60), sex (male and female), BMI (< 28 and ≥ 28), smoking (yes or no), diabetes mellitus (yes or no), hypertension (yes or no), hyperlipidemia (yes or no) and STEMI (yes or no). We examined the consistency of the association between LFS and outcomes in different subgroups. Statistical analysis was performed using R 4.0.3 software. Two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

6386 ACS patients who underwent PCI were enrolled in this study. The average age was 58.6 years old, and 4847(75.9%) were men. The baseline characteristics are presented according to the presence of liver fibrosis staged by APRI (cutoff 0.5 and 1.5) in Table 1. Compared to individuals with low fibrosis scores, those with intermediate and high fibrosis scores had a higher prevalence of male sex, STEMI, NSTEMI, left ventricular dysfunction (all p < 0.05). Moreover, compared with patients with low fibrosis scores, patients with intermediate and high fibrosis scores had significantly higher AST, ALT, total bilirubin, blood glucose and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (all p < 0.05). The baseline characteristics of the study population by dividing into MACCE groups or non-MACCE groups were shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to the liver fibrosis status staged by APRI

| Liver fibrosis | Low | Intermediate | High | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age | 58.7 (10.3) | 57.6 (10.6) | 58.1 (10.7) | 0.028 |

| Male | 4235 (75.1) | 542 (82.6) | 70 (76.9) | < 0.001 |

| BMI | 25.9 (3.3) | 25.7 (3.2) | 26.1 (2.6) | 0.29 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1700 (30.1) | 176 (26.8) | 22 (24.2) | 0.108 |

| Hypertension | 3680 (65.3) | 390 (59.5) | 55 (60.4) | 0.009 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3800 (67.4) | 409 (62.3) | 56 (61.5) | 0.019 |

| Smoking | 3267 (57.9) | 407 (62.0) | 52 (57.1) | 0.127 |

| Prior PCI | 1310 (23.2) | 161 (24.5) | 30 (33.0) | 0.076 |

| Prior CABG | 225 (4.0) | 24 (3.7) | 4 (4.4) | 0.898 |

| Prior MI | 772 (13.7) | 84 (12.8) | 9 (9.9) | 0.485 |

| Prior cerebrovascular disease | 635 (11.3) | 74 (11.3) | 10 (11.0) | 0.997 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 154 (2.7) | 18 (2.7) | 2 (2.2) | 0.953 |

| STEMI | 1139 (20.2) | 277 (42.2) | 58 (63.7) | < 0.001 |

| NSTEMI | 357 (6.3) | 84 (12.8) | 8 (8.8) | < 0.001 |

| UA | 4143 (73.5) | 295 (45.0) | 25 (27.5) | < 0.001 |

| Left ventricular dysfunction | 269 (4.8) | 51 (7.8) | 19 (20.9) | < 0.001 |

| Renal insufficiency | 2 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.032 |

| Procedural characteristics | ||||

| Chronic total occlusion | 396 (7.0) | 24 (3.7) | 2 (2.2) | 0.001 |

| Left main artery disease | 333 (5.9) | 37 (5.6) | 5 (5.5) | 0.952 |

| Moderate to severe calcification | 850 (15.1) | 99 (15.1) | 14 (15.4) | 0.997 |

| Lesion number | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.7) | 0.656 |

| Lesion length | 28.1 (18.8) | 28.4 (17.2) | 26.7 (17.1) | 0.72 |

| Minimum lesion diameter | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.3) | < 0.001 |

| Drug-eluting stent | 5399 (95.7) | 618 (94.2) | 81 (89.0) | 0.002 |

| Laboratory tests | ||||

| AST, IU/L | 20.0 (7.4) | 56.1 (25.0) | 216.9 (167.1) | < 0.001 |

| ALT, IU/L | 28.5 (19.3) | 71.9 (55.6) | 134.2 (142.8) | < 0.001 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 42.6 (4.2) | 41.9 (4.7) | 40.7 (4.2) | < 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin, μmol/L | 14.4 (5.4) | 15.7 (6.9) | 19.4 (10.5) | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.8 (0.8) | 0.499 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.2 (1.1) | 4.2 (1.0) | 4.5 (0.8) | 0.043 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.7 (0.8) | 0.075 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.3) | 0.04 |

| Blood glucose, mmol/L | 6.3 (2.3) | 6.8 (3.0) | 8.2 (4.5) | < 0.001 |

| High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, mg/L | 3.4 (3.9) | 5.3 (5.0) | 8.7 (5.8) | < 0.001 |

Variables are shown as mean (SD) or n (%). BMI, body mass index; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; MI, myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction UA, unstable angina; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Clinical outcomes according to liver fibrosis scores

The median follow-up time was 2.4 years. During the follow-up, 259 (4.06%) subjects had MACCE. 93 (1.46%) subjects had all-cause mortality, 50 (0.78%) subjects had cardiac death. 90 (1.41%) subjects had MI. 104 (1.63%) subjects had ischemic stroke. 190 (2.98%) subjects had major bleeding. 332 (5.2%) subjects had TVR. 66 (1.03%) subjects had stent thrombosis.

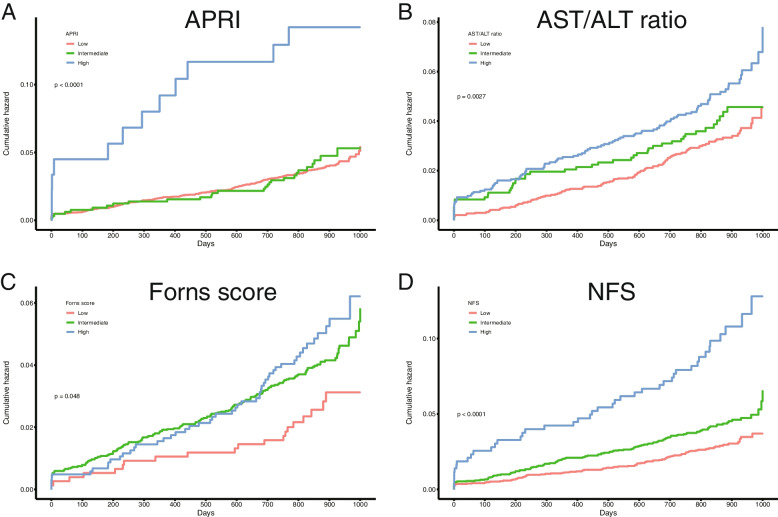

As shown in Fig. 1 and Table 2, increasing LFS was associated with progressively higher rates of MACCE. The incidence of MACCE increased from low LFS (2.6 to 3.9%) to high LFS (4.9 to 13.2%). Considering MACCE separately, mortality, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and stent thrombosis had a positive relationship with fibrosis scores. All LFS was not associated with bleeding events and TVR (all p > 0.05) (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

The Kaplan-Meier analysis for MACCE according to liver fibrosis scores. APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; AST/ALT ratio, aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio; NFS, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes according to liver fibrosis status

| Liver fibrosis staged by LFS | MACCE | All-cause death | Cardiac death | Myocardial infarction | Ischemic stroke | Major bleeding | TVR | Stent thrombosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APRI | ||||||||

| Low (N = 5639) | 219 (3.9) | 77 (1.4) | 37 (0.7) | 72 (1.3) | 89 (1.6) | 169 (3.0) | 289 (5.1) | 53 (0.9) |

| Intermediate (N = 656) | 28 (4.3) | 10 (1.5) | 7 (1.1) | 14 (2.1) | 11 (1.7) | 18 (2.7) | 38 (5.8) | 8 (1.2) |

| High (n = 91) | 12 (13.2) | 6 (6.6) | 6 (6.6) | 4 (4.4) | 4 (4.4) | 3 (3.3) | 5 (5.5) | 5 (5.5) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.108 | 0.922 | 0.76 | < 0.001 |

| AST/ALT ratio | ||||||||

| Low (N = 3352) | 112 (3.3) | 31 (0.9) | 18 (0.5) | 37 (1.1) | 54 (1.6) | 94 (2.8) | 182 (5.4) | 30 (0.9) |

| Intermediate (N = 2666) | 116 (4.4) | 48 (1.8) | 23 (0.9) | 41 (1.5) | 43 (1.6) | 87 (3.3) | 123 (4.6) | 27 (1.0) |

| High (N = 368) | 31 (8.4) | 14 (3.8) | 9 (2.4) | 12 (3.3) | 7 (1.9) | 9 (2.4) | 27 (7.3) | 9 (2.4) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.913 | 0.481 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Forns score | ||||||||

| Low (N = 763) | 20 (2.6) | 5 (0.7) | 2 (0.3) | 8 (1.0) | 8 (1.0) | 17 (2.2) | 44 (5.8) | 5 (0.7) |

| Intermediate (N = 4582) | 188 (4.1) | 58 (1.3) | 32 (0.7) | 66 (1.4) | 83 (1.8) | 135 (2.9) | 242 (5.3) | 45 (1.0) |

| High (N = 1041) | 51 (4.9) | 30 (2.9) | 16 (1.5) | 16 (1.5) | 13 (1.2) | 38 (3.7) | 46 (4.4) | 16 (1.5) |

| p value | 0.051 | < 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.648 | 0.174 | 0.209 | 0.397 | 0.152 |

| NFS | ||||||||

| Low (N = 3109) | 92 (3.0) | 33 (1.1) | 17 (0.5) | 33 (1.1) | 37 (1.2) | 86 (2.8) | 157 (5.0) | 24 (0.8) |

| Intermediate (N = 2842) | 124 (4.4) | 41 (1.4) | 20 (0.7) | 43 (1.5) | 53 (1.9) | 89 (3.1) | 150 (5.3) | 28 (1.0) |

| High (N = 435) | 43 (9.9) | 19 (4.4) | 13 (3.0) | 14 (3.2) | 14 (3.2) | 15 (3.4) | 25 (5.7) | 14 (3.2) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.592 | 0.802 | < 0.001 |

LFS, liver fibrosis scores; MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; TVR, target vessel reconstruction; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; AST/ALT ratio, aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio; NFS, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score

Association between liver fibrosis scores and MACCE

As displayed in Table 3, in unadjusted Cox regression analysis, subjects with high APRI scores exhibited an increased risk of MACCE compared to groups with low APRI scores (HR 3.69, 95%CI 2.06–6.6, p < 0.001). The MACCE risk increased in subjects with intermediate or high AST/ALT ratio (HR 1.31, 95%CI 1.01–1.69, p = 0.044; HR 2.59, 95%CI 1.74–3.85, p < 0.001), Forns score (HR 1.59, 95%CI 1.01–2.53, p = 0.047; HR 1.91, 95%CI 1.14–3.2, p = 0.015) and NFS (HR 1.48, 95%CI 1.13–1.94, p = 0.004; HR 3.43, 95%CI 2.39–4.92, p < 0.001) compared to the subjects with low scores. After adjustment for known predictors for MACCE (Table 4), the MACCE risk still increased in patients with a high APRI (HR 3.73, 95%CI 2.03–6.87, p < 0.001), high NFS (HR 2.73, 95%CI 1.86–4, p < 0.001), high AST/ALT ratio (HR 1.57, 95%CI 1.02–2.43, p = 0.042) and high Forns score (HR 1.77, 95%CI 1.05–3, p = 0.032).

Table 3.

Unadjusted Cox regression for clinical outcomes according to liver fibrosis status

| Liver fibrosis staged by LFS | MACCE | All-cause death | Cardiac death | Myocardial infarction | Ischemic stroke | Major bleeding | TVR | Stent thrombosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APRI | ||||||||

| Low (N = 5639) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Intermediate (N = 656) | 1.1 (0.74–1.63) | 1.12 (0.58–2.16) | 1.62 (0.72–3.63) | 1.67 (0.94–2.96) | 1.06 (0.57–1.98) | 0.91 (0.56–1.49) | 1.13 (0.81–1.59) | 1.29 (0.61–2.72) |

| p value | 0.638 | 0.743 | 0.242 | 0.079 | 0.855 | 0.717 | 0.471 | 0.498 |

| High (n = 91) | 3.69 (2.06–6.6) | 5.14 (2.24–11.8) | 10.59 (4.47–25.09) | 3.65 (1.33–9.99) | 3.05 (1.12–8.3) | 1.16 (0.37–3.65) | 1.13 (0.47–2.74) | 6.24 (2.49–15.61) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.012 | 0.029 | 0.794 | 0.784 | < 0.001 |

| AST/ALT ratio | ||||||||

| Low (N = 3352) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Intermediate (N = 2666) | 1.31 (1.01–1.69) | 1.94 (1.24–3.05) | 1.61 (0.87–2.98) | 1.4 (0.9–2.18) | 1 (0.67–1.49) | 1.17 (0.88–1.57) | 0.85 (0.68–1.07) | 1.13 (0.67–1.9) |

| p value | 0.044 | 0.004 | 0.132 | 0.141 | 0.995 | 0.288 | 0.161 | 0.641 |

| High (N = 368) | 2.59 (1.74–3.85) | 4.15 (2.21–7.8) | 4.59 (2.06–10.21) | 2.99 (1.56–5.74) | 1.2 (0.55–2.64) | 0.89 (0.45–1.75) | 1.39 (0.93–2.08) | 2.75 (1.31–5.8) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.647 | 0.726 | 0.11 | 0.008 |

| Forns score | ||||||||

| Low (N = 763) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Intermediate (N = 4582) | 1.59 (1.01–2.53) | 1.95 (0.78–4.87) | 2.69 (0.64–11.21) | 1.39 (0.67–2.9) | 1.76 (0.85–3.64) | 1.34 (0.81–2.22) | 0.92 (0.67–1.27) | 1.52 (0.6–3.82) |

| p value | 0.047 | 0.151 | 0.175 | 0.377 | 0.126 | 0.257 | 0.628 | 0.376 |

| High (N = 1041) | 1.91 (1.14–3.2) | 4.46 (1.73–11.5) | 5.94 (1.37–25.83) | 1.49 (0.64–3.47) | 1.22 (0.51–2.95) | 1.68 (0.95–2.97) | 0.77 (0.51–1.16) | 2.39 (0.87–6.51) |

| p value | 0.015 | 0.002 | 0.018 | 0.36 | 0.655 | 0.077 | 0.214 | 0.09 |

| NFS | ||||||||

| Low (N = 3109) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Intermediate (N = 2842) | 1.48 (1.13–1.94) | 1.36 (0.86–2.15) | 1.29 (0.67–2.46) | 1.43 (0.91–2.25) | 1.58 (1.04–2.4) | 1.14 (0.84–1.53) | 1.05 (0.84–1.31) | 1.28 (0.74–2.21) |

| p value | 0.004 | 0.192 | 0.445 | 0.124 | 0.034 | 0.401 | 0.688 | 0.377 |

| High (N = 435) | 3.43 (2.39–4.92) | 4.14 (2.35–7.28) | 5.5 (2.67–11.32) | 3.06 (1.64–5.72) | 2.75 (1.49–5.08) | 1.27 (0.73–2.2) | 1.16 (0.76–1.77) | 4.2 (2.17–8.12) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.392 | 0.495 | < 0.001 |

LFS, liver fibrosis scores; MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; TVR, target vessel reconstruction; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; AST/ALT ratio, aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio; NFS, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score

Table 4.

Adjusted Cox regression for clinical outcomes according to liver fibrosis status

| Liver fibrosis staged by LFS | MACCE | All-cause death | Cardiac death | Myocardial infarction | Ischemic stroke | Major bleeding | TVR | Stent thrombosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APRI | ||||||||

| Low (N = 5639) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Intermediate (N = 656) | 1.14 (0.76–1.7) | 0.97 (0.5–1.9) | 1.43 (0.63–3.27) | 1.91 (1.07–3.43) | 1.15 (0.61–2.16) | 0.99 (0.61–1.62) | 1.13 (0.80–1.59) | 1.35 (0.63–2.87) |

| p value | 0.524 | 0.931 | 0.394 | 0.029 | 0.676 | 0.977 | 0.495 | 0.438 |

| High (n = 91) | 3.73 (2.03–6.87) | 4.03 (1.66–9.78) | 8.87 (3.32–23.72) | 5.05 (1.76–14.5) | 3.32 (1.17–9.43) | 1.4 (0.44–4.45) | 1.08 (0.44–2.66) | 8.87 (3.29–23.94) |

| p value | < 0.001 | 0.002 | < 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.024 | 0.572 | 0.862 | < 0.001 |

| AST/ALT ratio | ||||||||

| Low (N = 3352) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Intermediate (N = 2666) | 0.92 (0.7–1.22) | 1.13 (0.71–1.82) | 0.92 (0.48–1.75) | 1.14 (0.71–1.82) | 0.69 (0.45–1.05) | 0.89 (0.65–1.21) | 0.87 (0.68–1.1) | 0.99 (0.58–1.72) |

| p value | 0.57 | 0.605 | 0.788 | 0.581 | 0.085 | 0.458 | 0.243 | 0.985 |

| High (N = 368) | 1.57 (1.02–2.43) | 1.56 (0.77–3.13) | 1.54 (0.62–3.8) | 2.64 (1.29–5.41) | 0.7 (0.3–1.62) | 0.67 (0.33–1.37) | 1.39 (0.90–2.14) | 2.46 (1.06–5.67) |

| p value | 0.042 | 0.214 | 0.352 | 0.008 | 0.408 | 0.276 | 0.141 | 0.035 |

| Forns score | ||||||||

| Low (N = 763) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Intermediate (N = 4582) | 1.55 (0.98–2.47) | 2.1 (0.84–5.27) | 2.89 (0.69–12.16) | 1.26 (0.6–2.64) | 1.62 (0.78–3.36) | 1.26 (0.76–2.09) | 0.91 (0.66–1.26) | 1.36 (0.54–3.45) |

| p value | 0.063 | 0.112 | 0.147 | 0.542 | 0.196 | 0.377 | 0.573 | 0.518 |

| High (N = 1041) | 1.77 (1.05–3) | 4.46 (1.71–11.62) | 5.59 (1.26–24.75) | 1.32 (0.56–3.13) | 1.08 (0.44–2.62) | 1.57 (0.88–2.8) | 0.74 (0.49–1.13) | 1.88 (0.68–5.22) |

| p value | 0.032 | 0.002 | 0.023 | 0.53 | 0.871 | 0.128 | 0.166 | 0.226 |

| NFS | ||||||||

| Low (N = 3109) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Intermediate (N = 2842) | 1.31 (1–1.72) | 1.2 (0.76–1.92) | 1.05 (0.55–2.03) | 1.24 (0.78–1.96) | 1.35 (0.88–2.07) | 1.06 (0.78–1.43) | 1.01 (0.81–1.27) | 1.12 (0.65–1.96) |

| p value | 0.052 | 0.434 | 0.875 | 0.364 | 0.168 | 0.702 | 0.928 | 0.679 |

| High (N = 435) | 2.73 (1.86–4) | 2.77 (1.51–5.07) | 3.49 (1.61–7.57) | 2.77 (1.44–5.31) | 2.12 (1.12–4.04) | 1.24 (0.7–2.17) | 1.08 (0.70–1.67) | 4.08 (2.05–8.15) |

| p value | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.022 | 0.462 | 0.719 | < 0.001 |

LFS, liver fibrosis scores; MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; TVR, target vessel reconstruction; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; AST/ALT ratio, aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio; NFS, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score

To simply compare the outcomes between patients with liver cirrhosis and without, the whole population was divided into two groups with or without liver cirrhosis based on APRI (APRI cutoff at 1.5). We found that liver cirrhosis is associated with an increased risk of MACCE, all-cause death, cardiac death, MI, ischemic stroke, and stent thrombosis but not TVR and major bleeding (Table 5).

Table 5.

Unadjusted and adjusted Cox regression for clinical outcomes according to liver cirrhosis evaluated by APRI

| Non-cirrhosis | Cirrhosis | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted risk | |||

| MACCE | 1(reference) | 3.65 (2.05–6.52) | < 0.001 |

| All-cause death | 1(reference) | 5.08 (2.22–11.62) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac death | 1(reference) | 9.95 (4.24–23.34) | < 0.001 |

| MI | 1(reference) | 3.41 (1.25–9.30) | 0.017 |

| Ischemic stroke | 1(reference) | 3.03 (1.11–8.23) | 0.030 |

| TVR | 1(reference) | 1.12 (0.46–2.70) | 0.81 |

| Major bleeding | 1(reference) | 1.18 (0.38–3.68) | 0.782 |

| Stent thrombosis | 1(reference) | 6.06 (2.43–15.07) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted risk | |||

| MACCE | 1(reference) | 3.65 (1.99–6.69) | < 0.001 |

| All-cause death | 1(reference) | 4.05 (1.68–9.75) | 0.002 |

| Cardiac death | 1(reference) | 8.19 (3.11–21.53) | < 0.001 |

| MI | 1(reference) | 4.45 (1.55–12.73) | 0.005 |

| Ischemic stroke | 1(reference) | 3.24 (1.15–9.17) | 0.026 |

| TVR | 1(reference) | 1.06 (0.43–2.60) | 0.90 |

| Major bleeding | 1(reference) | 1.40 (0.44–4.45) | 0.57 |

| Stent thrombosis | 1(reference) | 8.39 (3.14–22.47) | < 0.001 |

MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular event; MI, myocardial infarction; TVR, target vessel reconstruction. Values are hazard ratio (95% confidence interval)

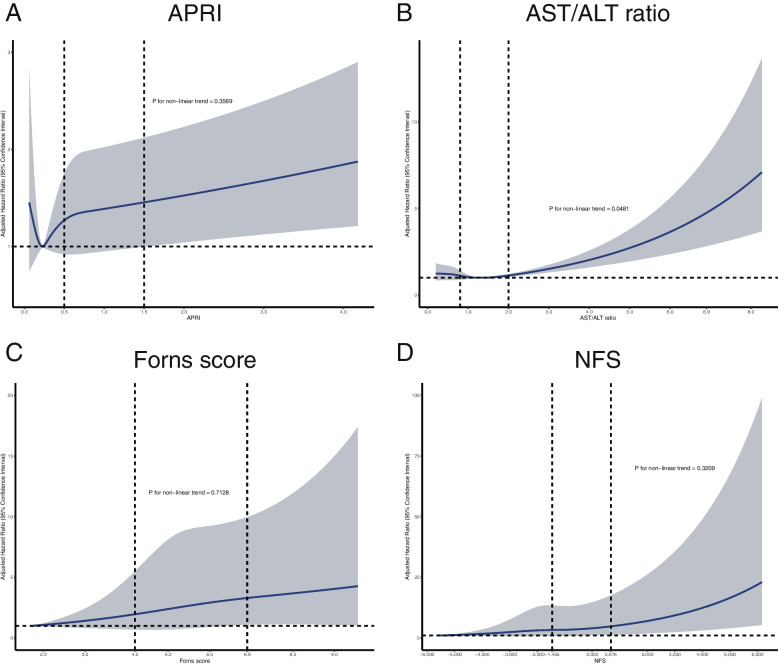

As shown in Fig. 2, further adjusted restricted cubic spline analysis showed that as continuous variables, APRI, AST/ALT ratio, Forns score, and NFS were independently associated with increased MACCE risk. AST/ALT ratio had a non-linear positive relationship with MACCE risk, while APRI, NFS, and Forns score had a linear positive relationship with the MACCE risk.

Fig. 2.

Restricted cubic spline analysis for MACCE according to liver fibrosis scores. APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; AST/ALT ratio, aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio; NFS, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1–4, patients were divided into subgroups according to age (< 60 and ≥ 60), sex (male and female), BMI (< 28 and ≥ 28), smoking (yes or no), diabetes mellitus (yes or no), hypertension (yes or no), hyperlipidemia (yes or no) and STEMI (yes or no). Consistently, patients with intermediate and high APRI, AST/ALT ratio, Forns score, and NFS tended to have an elevated risk of MACCE compared to those with a low score. This positive correlation was consistent in different subgroups.

Association between liver fibrosis scores and secondary outcomes

Before and after adjustment, the risk of major bleeding did not significantly increase in groups with intermediate or high LFS (Table 3 and Table 4). Considering MACCE separately, elevated MACCE risks in the high APRI and NFS groups were mainly driven by increased mortality, MI, ischemic stroke and stent thrombosis (all p < 0.05). Elevated MACCE risks in the high Forns score group were primarily driven by increased mortality (p < 0.05). Elevated MACCE risks in the high AST/ALT ratio group were mainly driven by increased MI, and stent thrombosis (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Previous studies demonstrated that LFS was associated with cardiovascular events [19–21]. Investigating the association of noninvasive fibrosis scores with thrombotic and bleeding events in acute coronary syndrome may open a new mind to thrombotic and bleeding tradeoffs in ACS management. Our study firstly evaluated the prognostic implication of APRI, AST/ALT ratio, Forns score, and NFS on the thrombotic and bleeding events of ACS patients who underwent PCI. We found that increased APRI, NFS, AST/ALT ratio, and Forns scores were associated with an elevated risk of thrombotic events but had no significant association with major bleeding. Compared to the patients with a low LFS, patients with a high LFS exhibited an increased risk of MACCE by 1.57- to 3.73-fold. Subgroup analysis showed that this positive correlation was consistent in different ages, sex, BMI, smoking status, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and STEMI subgroups.

Liver fibrosis severity indicates liver health status. Since the liver plays a critical role in lipid and glucose metabolism, and liver disease shares common risk factors with cardiovascular diseases, such as hypertension, insulin resistance, and systemic inflammation [22–25], it is reasonable to explore the relationship between liver fibrosis and cardiovascular diseases. As an alternative tool for liver biopsy, noninvasive LFS could evaluate liver fibrosis accurately and have good prognostic values for adverse outcomes. Elevated APRI and NFS were associated with an increased risk of mortality and hepatic complications in the NAFLD population [26]. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that increased APRI, Forns score, and NFS, were associated with increased risks of all-cause death, cardiac death, and liver-specific death in the U.S. population [27, 28]. NFS was associated with the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes mellitus [29]. These studies demonstrated that LFS was associated with hepatic and non-hepatic events in patients with and without liver diseases. Recent studies started exploring the relationship between LFS and cardiovascular disease. APRI and Forns scores were reported to be associated with mortality in intracerebral hemorrhage patients and ischemic stroke patients, respectively [30, 31]. Besides, APRI, Forns score, and NFS predicted all-cause mortality and cardiac death risks in coronary heart disease patients [28]. APRI was related to coronary calcification and severity in patients with coronary heart disease [5, 32]. Elevated AST/ALT ratio and NFS were associated with the increased risk of cardiovascular events in patients with the stable coronary disease after PCI [7]. This study is the first one exploring the relationship between LFS and thrombotic/bleeding events in ACS patients.

In our study, compared to the low score group, individuals with high APRI, AST/SLT ratio, Forns score, and NFS had a higher risk of MACCE. Additionally, APRI and NFS showed better performance predicting secondary outcomes than other scores, suggesting LFS could predict the risk of adverse outcomes in ACS patients undergoing PCI, which is consistent with previous studies. Besides, previous researches mainly focus on the predictive value of APRI or NFS on cardiovascular diseases. In our study, we comprehensively investigated four LFS, including APRI, AST/ALT ratio, Forns score, and NFS, to evaluate and compare their predictive values for thrombotic and bleeding events. And we found that LFS could predict thrombotic events in ACS patients but not bleeding events. Procoagulant imbalance is common in people with chronic liver disease, even those with mildly elevated liver fibrosis scores [33]. Inflammatory status, elevated thrombophilic factors, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative injury in liver fibrosis or cirrhosis lead to hypercoagulable and thrombotic state [34, 35], increasing ischemic events risk. Besides, hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, stress, and obesity, which are prevalent in ACS patients, may also exacerbate the hypercoagulable state [36]. This may be why liver fibrosis is associated with thrombotic events in our study but not bleeding. The ischemic and bleeding trade-off for ACS patients after PCI is vital. Our study suggested liver fibrosis staged by LFS was associated with ischemic events in ACS patients, and LFS might be a helpful tool for identifying patients with a high risk of ischemic events after PCI.

Limitation

There are some limitations existing in our study. First, this study is an observational cohort study, which cannot identify a direct causal relationship because of the inherent limitations of such studies. Second, all patients received pre-loading of ticagrelor and or clopidogrel as recommended by the guidelines, which could influence the bleeding events in these populations. But we believed the treatment would not negate the bleeding characteristic of patients with high bleeding risk, which might require further study. Third, this study lacks liver biopsy or imaging techniques such as ultrasound elastography to confirm the severity of liver fibrosis. Recent studies suggested that the combination of imaging techniques and liver fibrosis scores could better diagnose liver fibrosis. And at the basis of this study, future research could seek to combine imaging techniques and LFS. Fourth, clopidogrel could cause thrombocytopenia, but this is a small probability event during PCI, according to previous reports. Fifth, since liver fibrosis scores could properly evaluate fibrosis in a different population, the present study focused on the extent of overall liver fibrosis. Additional information about the study population’s chronic liver disease status (e.g., viral hepatitis, NAFLD) was not collected, which might require further research.

Conclusions

This study found that elevate LFS was associated with an increased risk of MACCE, morality, MI, and stent thrombosis in patients with ACS, but not bleeding events and TVR. LFS may contribute to thrombotic risk stratification among ACS patients and help clinical decision making.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Fig. 1. Subgroup analysis for APRI. APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Fig. 2. Subgroup analysis for AST/ALT ratio. AST/ALT ratio, aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio

Additional file 3: Supplementary Fig. 3. Subgroup analysis for Forns score

Additional file 4: Supplementary Fig. 4. Subgroup analysis for NFS. NFS, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score

Additional file 5: Supplementary Table 1. Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis of MACCE. Supplementary Table 2. Baseline characteristics according to the absence and presence of MACCE

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleague in the department of cardiology at Fuwai hospital.

Abbreviations

- LFS

liver fibrosis scores

- APRI

aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index

- AST/ALT ratio

aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio

- NFS

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score

- ACS

acute coronary syndrome

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- MI

myocardial infarction

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- MACCE

major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events.

Authors’ contributions

Y.L and J. S contributed to the conception and design, and data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to collection and assembly of data, and manuscript writing. Y. T contributed to administrative support and provision of study materials. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFC2004705), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81825003, 91957123, 82270376), the Beijing Nova Program (Z201100006820002) from Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission, CSC Special Fund for Clinical Research (CSCF2021A04), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2022-I2M-C&T-B-119, 2021-I2M-5-003).

Availability of data and materials

The data are not publicly available because of institutional review board restrictions.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted following the amended Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of Fuwai Hospital approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yupeng Liu and Jingjing Song contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Neumann F-J, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, Alfonso F, Banning AP, Benedetto U, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87–165. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moon AM, Singal AG, Tapper EB. Contemporary epidemiology of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2650–2666. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karsdal MA, Manon-Jensen T, Genovese F, Kristensen JH, Nielsen MJ, Sand JMB, et al. Novel insights into the function and dynamics of extracellular matrix in liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;308:G807–G830. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00447.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caballería L, Pera G, Arteaga I, Rodríguez L, Alumà A, Morillas RM, et al. High prevalence of liver fibrosis among European adults with unknown liver disease: a population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:1138–1145.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishiba H, Sumida Y, Kataoka S, Kuroda M, Akabame S, Tomiyasu K, et al. Association of coronary artery calcification with liver fibrosis in Japanese patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol Res. 2016;46:1107–1117. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.You SC, Kim KJ, Kim SU, Kim BK, Park JY, Kim DY, et al. Hepatic fibrosis assessed using transient elastography independently associated with coronary artery calcification: liver stiffness and coronary calcification. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1536–1542. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin J-L, Zhang H-W, Cao Y-X, Liu H-H, Hua Q, Li Y-F, et al. Liver fibrosis scores and coronary atherosclerosis: novel findings in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Hepatol Int. 2021;15:413–423. doi: 10.1007/s12072-021-10167-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bravo AA, Sheth SG, Chopra S. Liver Biopsy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:495–500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ratziu V, Charlotte F, Heurtier A, Gombert S, Giral P, Bruckert E, et al. Sampling variability of liver biopsy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1898–1906. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagström H, Talbäck M, Andreasson A, Walldius G, Hammar N. Ability of noninvasive scoring systems to identify individuals in the population at risk for severe liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:200–214. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naveau S, Gaudé G, Asnacios A, Agostini H, Abella A, Barri-Ova N, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic values of noninvasive biomarkers of fibrosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:97–105. doi: 10.1002/hep.22576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wai C. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–526. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forns X, Ampurdanès S, Llovet JM, Aponte J, Quintó L, Martínez-Bauer E, et al. Identification of chronic hepatitis C patients without hepatic fibrosis by a simple predictive model: identification of chronic hepatitis C patients without hepatic fibrosis by a simple predictive model. Hepatology. 2002;36:986–992. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheth SG, Flamm SL, Gordon FD, Chopra S. AST/ALT ratio predicts cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:44–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.044_c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, George J, Farrell GC, et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology. 2007;45:846–854. doi: 10.1002/hep.21496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McPherson S, Stewart SF, Henderson E, Burt AD, Day CP. Simple non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can reliably exclude advanced fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2010;59:1265–1269. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.216077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.AST/ALT Ratio [Internet]. Standard of Care. Available from: https://standardofcare.com/ast-alt-ratio/

- 18.Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the bleeding academic research consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamaki N, Kurosaki M, Takahashi Y, Itakura Y, Inada K, Kirino S, et al. Liver fibrosis and fatty liver as independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:2960–2966. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S, Adams LA, Bjornsson ES, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, et al. Liver fibrosis, but no other histologic features, is associated with long-term outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:389–397.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekstedt M, Hagström H, Nasr P, Fredrikson M, Stål P, Kechagias S, et al. Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease-specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow-up. Hepatology. 2015;61:1547–1554. doi: 10.1002/hep.27368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siddiqui MS, Fuchs M, Idowu MO, Luketic VA, Boyett S, Sargeant C, et al. Severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and progression to cirrhosis are associated with atherogenic lipoprotein profile. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1000–1008.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villanova N, Moscatiello S, Ramilli S, Bugianesi E, Magalotti D, Vanni E, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular risk profile in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;42:473–480. doi: 10.1002/hep.20781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Møller S, Bernardi M. Interactions of the heart and the liver. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2804–2811. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lonardo A, Nascimbeni F, Mantovani A, Targher G. Hypertension, diabetes, atherosclerosis and NASH: cause or consequence? J Hepatol. 2018;68:335–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henson JB, Simon TG, Kaplan A, Osganian S, Masia R, Corey KE. Advanced fibrosis is associated with incident cardiovascular disease in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:728–736. doi: 10.1111/apt.15660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim D, Kim WR, Kim HJ, Therneau TM. Association between noninvasive fibrosis markers and mortality among adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States. Hepatology. 2013;57:1357–1365. doi: 10.1002/hep.26156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unalp-Arida A, Ruhl CE. Liver fibrosis scores predict liver disease mortality in the United States population: Unalp-Arida and Ruhl. Hepatology. 2017;66:84–95. doi: 10.1002/hep.29113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chun HS, Lee JS, Lee HW, Kim BK, Park JY, Kim DY, et al. Association between the severity of liver fibrosis and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:1703–1713. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parikh NS, Kamel H, Navi BB, Iadecola C, Merkler AE, Jesudian A, et al. Liver fibrosis indices and outcomes after primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2020;51:830–837. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.028161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fandler-Höfler S, Stauber RE, Kneihsl M, Wünsch G, Haidegger M, Poltrum B, et al. Non-invasive markers of liver fibrosis and outcome in large vessel occlusion stroke. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2021, 2022 Jan; http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/17562864211037239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Chang Y, Ryu S, Sung K-C, Cho YK, Sung E, Kim H-N, et al. Alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and associations with coronary artery calcification: evidence from the Kangbuk Samsung health study. Gut. 2019;68:1667–1675. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sigon G, D’Ambrosio R, Clerici M, Pisano G, Chantarangkul V, Sollazzi R, et al. Procoagulant imbalance influences cardiovascular and liver damage in chronic hepatitis C independently of steatosis. Liver Int. 2019;39:2309–2316. doi: 10.1111/liv.14213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tripodi A, Fracanzani AL, Primignani M, Chantarangkul V, Clerici M, Mannucci PM, et al. Procoagulant imbalance in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014;61:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Northup PG, Argo CK, Shah N, Caldwell SH. Hypercoagulation and thrombophilia in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: mechanisms, human evidence, therapeutic implications, and preventive implications. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32:39–48. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1306425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Northup PG, Sundaram V, Fallon MB, Reddy KR, Balogun RA, Sanyal AJ, et al. Hypercoagulation and thrombophilia in liver disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:2–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Fig. 1. Subgroup analysis for APRI. APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Fig. 2. Subgroup analysis for AST/ALT ratio. AST/ALT ratio, aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio

Additional file 3: Supplementary Fig. 3. Subgroup analysis for Forns score

Additional file 4: Supplementary Fig. 4. Subgroup analysis for NFS. NFS, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score

Additional file 5: Supplementary Table 1. Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis of MACCE. Supplementary Table 2. Baseline characteristics according to the absence and presence of MACCE

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available because of institutional review board restrictions.