Abstract

Extractables or leachables of biomaterials or residues of additives used in the manufacturing process that are potentially released from a medical device may have an adverse effect on a patient. Chemical characterization of leachable chemicals and degradation products in a medical device is an important aspect of its overall biocompatibility assessment process, which helps to ensure that the therapeutical benefits exceed the potential biological risks associated with the use of the device or its components or materials. By evaluating the types and amounts of chemicals that may migrate from a device to a patient during clinical use, potential toxicological risks can be assessed. A semipolar solvent, 40% ethanol in water (v/v), an appropriate surrogate for blood and blood related substances, was used as an extraction medium to mimic the body fluid in contact with a medical device. The extraction was conducted at 37 °C for 24 h for limited exposure medical devices per ISO 10993-12:2021. From gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) and liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis, leachable chemicals of polylactams, linear polyamides, cyclic polytetramethylene ether (PTME), poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol (PTMEG), cyclic and linear poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipate (PTMEGA), cyclic and linear poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipamide (PTMEGAA) were structurally elucidated. The workflow presented in this study was proven to be a successful approach for rapid extractable and leachable profiling and identification with confidence.

Introduction

US Food and Drug administration (FDA) issued guidance of use of International Standard ISO 10993-1, biological evaluation of medical devices—Part 1: Evaluation and testing within a risk management process, to assist industry in preparation of de novo requests for medical devices that have direct or indirect contact with the human body.1,2 The recommendation is to assess the biocompatibility of a medical device within the framework of a risk management process. One of the risk assessments in a medical device is hazardous compounds may be introduced in the final manufactured device, which could cause unexpected toxicities. A chemical analysis of the extractables and leachables of a device in its final finished form can be informative to evaluate the need for additional biocompatibility testing such as chronic toxicity, genotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and reproductivity/developmental toxicity.3 In addition, it can be used to assess the toxicological risk of the chemicals that are exposed from the devices.

ISO 10993-18:2020, chemical characterization of medical device materials, and ISO 10993-12:2021, sample preparation and reference materials, provide a framework for experimental design and control, sample selection and preparation, extraction conditions, chemical characterization considerations, and general analytical methods for extractable and leachable studies.4,5 Leachables are the chemical species which migrate from the components of medical devices under the normal condition of clinical use. A simulated extraction is accomplished by using extraction conditions, such as temperature and duration, that mimic the conditions of clinical use. Water with a proportion of ethanol (volume by volume) was demonstrated to be an appropriate simulating vehicle to extract comparable levels of the target leachables with respect to blood.6 An exaggerated extraction establishes the highest amount of leachable in a single extraction that most likely will be released by the medical device or material during clinical use.5 An exaggerated extraction is performed with elevated temperature, a duration that exceeds the duration of clinical use, and at a surface area/volume ratio that exceeded clinical use exposure. It is recommended that exaggerations be kept as small as needed, minimizing potential artificial effects, such as degradation.

Materials used to manufacture medical devices are very diverse. Different parts of medical devices, depending on physical properties required, are made with different categories of polymers and other components, such as additives and fillers.7,8 Four polymers are the primary materials used in many medical devices: polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), and polystyrene (PS).9 Additional polymers, such as polycarbonate (PC), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), thermoplastic urethane (TPU), thermoplastic elastomers (TPE), and polyamides were developed to improve the performance of devices.9,10 The challenge to study extractable and leachable materials in the medical devices is the diversity of chemicals from different polymers, and the spectra information on chemical components in most of these polymers and their degradation products cannot be found in a commercially available database. Medical device industries need to build their own chemical and its spectra library of polymer materials to meet increased scrutiny of toxicity from regulatory agencies. Advanced analytical techniques need to be applied to elucidate the different classes of chemicals unambiguously to demonstrate the biocompatibility. GC and LC in tandem with high resolution accurate mass spectrometry are widely used in the identification of volatile, semivolatile, and nonvolatile migrants from packaging materials and environment samples10−15 and are part of the recommended workflow by FDA for chemical characterization in medical devices.16

Polyether block amide and polyurethane were widely used in catheter devices. Polyether block amide or PEBA is known under the trade name of PEBAX (Arkema). It is a block copolymer obtained by polycondensation of a carboxylic acid polyamide with a repeating unit of 12 and an alcohol termination poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol (PTMEG) (Chart 1).17,18 In this study, a few classes of leachables in catheter devices, made from Pebax, Nylon-11 and coated with polyvinylpyrrolidone, were investigated using high resolution accurate mass spectrometry in combination of conventional low resolution GC–MS.

Chart 1. Polyether Block Amide Structure (Pebax)a.

a x and y are the repeating units of nylon12 and poly(tetramethylene oxide), respectively. z is the repeating units of PEBA.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Reagents

Analytical grade 200 proof ethanol was obtained from EMD Millipore (Burlington, MA), LC–MS grade methanol, 12-aminododecanolactam, analytical grade dichloromethane, and butylated hydroxy toluene were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis. MO). 12-Aminododecanoic acid was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). Eighteen Ω Milli-Q water was produced in house. Steerable Guide Catheter (SGC) was a commercially available medical device made by Abbott Vascular (Santa Clara, CA). Incubator (model 1545), and acetic acid glacial was obtained from VWR (Township, NJ). N-Evap sample evaporator (model N-EVAP 112) was purchased from Organomation Associates (Berlin, MA).

Sample Preparation

Extractable and leachable materials were extracted from a steerable guide catheter (SGC) device with 40% ethanol in water. The extraction sample was incubated at 37 °C for 24 ± 1 h. Based on the wall thickness of the test article (<0.5 mm), the ratio of 6 cm2/mL of surface area to 40% ethanol in water was used for the extraction, an appropriate surrogate for blood and blood related substances. The extraction sample solution was subjected to solvent exchange to remove the aqueous phase from the extraction samples and to replace it with dichloromethane (DCM) for GC–MS analysis. The 40% ethanol extraction sample solution was used directly for LC–MS analysis.

GC–MSD and GC–QTOF

Samples in DCM were subsequently analyzed using Agilent 6890N/5973B gas chromatograph–mass spectrometry detector (Wilmington, DE) equipped with a liquid sample injection. The gas chromatograph was fitted with an Agilent HP-5MS capillary column (0.25 μm × 30 m, 0.25 μ film thickness) and operated with temperature programming from 45 °C (held for 0.5 min) to 315 °C at 10 °C/min, and held at 315 °C for 5 min using helium as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1 mL/min. The GC injector port was set at 300 °C in a splitless mode for 1 min and then purged at 25 mL/min. The MSD was operated with transfer line, ion source, and quadruple temperatures at 300 °C, 230 °C, and 150 °C, respectively. The sample injection volume is 1 μL. All the GC–MS data were acquired with Masshunter Workstation 10.0.368 (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE) in the m/z range of 33–600 at a rate of 2 scan/sec under electron ionization (EI) mode. Data were acquired directly to OpenLab Enterprise Content Manager (ECM) Data Management system that has built-in technical controls to ensure data control with integrity. GC–MS system performance suitability following predefined acceptable criteria was conducted and passed before samples were analyzed. A sample in DCM was also analyzed in a 7250 QTOF instrument coupled to an 8890 GC (Agilent) under EI modes at 70 and 13 eV, and CI mode using either methane, isobutane, or ammonia as reagent gas. Agilent DB-5MS capillary column (0.25 μm × 30 m, 0.25 μm film thickness) was used with the same GC parameters as used in GC–MSD.

LC–Orbitrap MS

A Vanquish UHPLC system coupled to an Orbitrap Exploris 120 MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) and a heated electrospray ion source (HESI) was used to acquire accurate mass spectra in both positive and negative modes. The HESI source parameters were set with ion spray voltage of 2.8 kV for (−)-ESI (negative ionization mode) and 3.5 kV for (+)-ESI (positive ionization mode); sheath gas flow rate of 40 arbitrary units and auxiliary gas flow rate of 10 arbitrary units; the temperatures of the vaporizer and capillary were both kept at 325 °C. Full mass spectra were obtained from m/z 150–2000 at a resolution of 60,000 with polarity switch. The full scan and data-dependent MS2 (dd-MS2) workflow were acquired at a resolution of 30000 (MS) and 15000 (dd-MS2) with normalized higher energy collision dissociation (HCD). Radio frequency (RF) lens was set at 70%. The HCD NCE (normalized collision energy) was set to 30%, 50%, and 70% for MS/MS acquisition. Data was acquired in profile mode with microscans at 1 and dd-MS2 isolation window (m/z) of 1.5. The system was configured under Foundation 3.1 sp8. The software for the Vanquish system and Orbitrap MS are Thermo Scientific SII 1.6.0.60983 and Orbitrap Exploris 120 Tune 4.0.309.28, respectively. All the data acquisition and analysis were made by Xcalibur 4.5, TraceFinder 5.1, and Compound Discoverer 3.2.0.421 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, California, USA). Samples were separated on an Agilent (Wilmington, DE) Zorbax, RRHD SB-C18 column (2.1 mm i.d. × 100 mm, 1.8 μm particle size) and the mobile phase consists of 0.1% acetic acid in water (mobile phase A) and 0.1% acetic acid in MeOH (mobile phase B). The gradient is from 95% A to 95% B in 0–12 min and hold at 95% B for 6 min for a total of 18 min run with the flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The system was equilibrated with 95% A for 6 min before the next injection. The sample injection volume is 5 μL.

Results and Discussion

The study intends to characterize the possible leachable chemical profile of the catheter device and to support a toxicological risk assessment that materials of construction or manufacturing materials contain chemicals that do not present a potential chemical hazard during clinical use. A steerable guide catheter (SGC) is a delivery device facilitating the percutaneous advancing and installing of a medical device on-site with an implantation procedure typically lasting 1 to 3 h. The test article was extracted with 40% ethanol in water at 37 °C for 24 h to mimic worst-case time duration the device to interact with body fluid for limited contact medical devices.19,20 The main body of the investigated steerable guide catheter is made of Pebax and nylon-11 [NH(CH2)10CO]n with polyvinylpyrrolidone material as the lubricious coating on the outer surface. Polyvinylpyrrolidone, also commonly called polyvidone or povidone, is a water-soluble polymer made from the monomer N-vinylpyrrolidone (C6H9NO)n. Pebax is the trade name of the polyether block amide from Arkema. The specific Pebax used in a catheter is Pebax 55D and Pebax 40D, belonging to the Pebax elastomer family, and consisting of polyamide and polyether backbone blocks (Chart 1).21−24 Both Pebax 55D (5533 SA 01 MED) and 40D (4033 SA 01 MED) are a thermoplastic elastomer made of flexible polyether and rigid polyamide, providing an ideal choice for catheter tubing that requires good flexibility and stiff resistance.25,26

The SGC device leachable sample was first analyzed by GC–MSD and GC–QTOF to determine semivolatile compounds. A typical chromatogram of the SGC in 40% ethanol extract in GC–MSD is presented in Figure 1. The peak at retention time (RT) 10.451 min is the internal standard of methyl nonanoate used in the extraction solvent. The major extractables in SGC are tributyl acetylcitrate at RT 21.818 min, dodecalactam at RT 17.596 min, N-butyl-benzenesulfonamide at RT 17.467 min, undecalactam at RT 16.469 min, and 2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone at RT 18.471 min, respectively, based on a NIST library search. The matching factors for all these major compounds are more than 920. Dodecalactam was confirmed by authentic standard. A NIST library search can quickly identify known compounds included in the NIST library. All the above compounds can be also detected by LC in tandem with orbitrap MS using a Compound Discoverer searching algorithm. N-Butyl-benzenesulfonamide is a plasticizer used in the polymerization of polyamide,27 and tributyl acetylcitrate is a plasticizer used in Pebax medical tubes.28 2,2-Dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone is a photoinitiator,29 likely to be used in the polymerization of N-vinylpyrrolidone.

Figure 1.

Typical chromatogram of SGC in 40% ethanol extract in GC–MSD.

With a combination of additional GC-QTOF in positive chemical ionization (PCI) and LC–MS–Orbitrap analyses, several classes of Pebax 55D, Pebax 40D, and Nylon-11 related chemicals have been identified and structurally elucidated. The data analysis took the advantage of accurate mass and isotope ratio measurement of the high-resolution mass spectrometry instrument, and various advanced database search and in silico fragmentation matching to MS2 spectra. The identified Pebax and nylon-11 related chemical classes are summarized in Chart 2 and discussed in the following sections.

Chart 2. Chemical Structures Identified in Catheter Devicea.

a A: polylactam; B: polyamide with a terminal amine and carboxylic acid group; C: cyclic polytetramethylene ether; D: poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol; E: cyclic poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipate; F: linear poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipate with a terminal hydroxyl and carboxylic acid group; G: cyclic poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipamide; H: linear poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipamide with a terminal hydroxyl and carboxylic acid group.

Identification of Polylactam and Other Polyamide Compounds

NIST library and other available databases cannot provide correct identification for all other components in the chromatogram because most of the polymers and their degradation products are not included in these libraries. The identification of unknown leachables is based on the accurate mass, isotope ratio, and fragmentation pattern in GC–MS and LC–MS spectra.

The component spectrum at RT 17.814 min (Figure S2) in GC–MSD has a similar pattern to the spectrum at RT 17.570 min (Figure S1) except there are two mass units less for the most of ions than dodecalactam, suggesting this compound has one double bond in the structure. The compound at RT 17.814 min was then named to be dodecelactam. The double bond position cannot be determined by GC–MS data alone. The RTs of peaks at 30.018 min (Figure S3) and 32.194 min (Figure S4) can be identified to be dimers of undecalactam and dodecalactam based on their spectra. The GC-QTOF results were able to further confirm their identification based on the M+ ions in 70 EV EI at m/z 366.3247 and m/z 394.3564, and [M + H]+ ions at m/z 367.3319 and m/z 395.3633 in positive chemical ionization (PCI) using isobutane as reagent gas, respectively.

From LC–MS data obtained with Orbitrap Exploris 120, these four lactams in the extract were confirmed and additional polylactams were identified. The difference between the measured mass from Orbitrap mass spectra and theoretical masses of targeted compounds is less than 3 ppm. In combination of accurate mass and isotope ratio in high resolution full scan spectrum, it allows to significantly limit the number of empirical molecular formula of the targeted peak. The proposed polylactam structures [NH(CH2)nCO]x, where x = 1–3 and n = 10, 11, and 13 are listed in Table 1 and Chart 2A.

Table 1. Polylactams Identified in LC–MS Positive Ionization Modes.

| RT (Minute) | Chemical Name | Measured mass (M+H)+/(M+Na)+ | Molecular Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8.74 | undecalactam | 184.1697/206.1516 | C11H21NO |

| 9.55 | dodecalactam | 198.1853/220.1673 | C12H23NO |

| 9.73 | dodecelactam | 196.1697/218.1516 | C12H21NO |

| 10.42 | tetradecalactam | 226.2168/248.1987 | C14H27NO |

| 10.53 | undecalactam dimer | 367.3325/389.3144 | (C11H21NO)2 |

| 11.07 | dodecalactam dimer | 395.3633/417.3455 | (C12H23NO)2 |

| 11.82 | undecalactam trimer | 550.4948/572.4766 | (C11H21NO)3 |

| 12.44 | dodecalactam trimer | 592.5419/614.5234 | (C12H23NO)3 |

MS2 spectra of m/z 367.3318 (Figure S5) and m/z 550.4937 (Figure S6) in positive ionization mode showed the fragmentation pattern of proposed undecalactam dimer and undecalactam trimer, respectively. The proposed structures are further confirmed by comparison of the fragment ion pattern of these two compounds using the fragment ion searching (FISh) scoring node in the Compound Discoverer software. The FISh scoring node compares fragment ions in the MS2 spectra against theoretical fragments of putative structures by in silico fragmentation prediction. The FISh scoring node in Figure 2 provided structural information on the 26-fragment ion match to the suggested structure, with a FISh coverage of 65%, further confirming the elucidation of the undecalactam trimer.

Figure 2.

FISh coverage of undecalactam trimer.

In the LC–MS analysis with negative ionization mode, the undecalactam dimer and undecalactam trimer showed m/z at 425.3380 (C24H45O4N2) and 608.5002 (C35H66O5N2), respectively. These two compounds tend to form acetic adducts when mobile phases were acidified with acetic acid. Similarly, the dodecalactam dimer and dodecalactam trimer also form acetic adducts in the negative mode.

The linear polyamides with an amine and a carboxylic acid group in each terminal, H[NH(CH2)nCO]xOH, where x = 1−2 and n = 10−11, were also identified based on fragmentation patterns and accurate masses in both positive and negative ionization modes (Chart 2B). The retention times and accurate mass of this group of compounds in both positive and negative ionization modes were listed in Table 2. 12-Aminododecanoic acid was further confirmed by an authentic standard.

Table 2. Linear Polyamide with an Amine and a Carboxylic Acid in Each Terminal Identified with LC–MS Analysis in Both Positive and Negative Ionization Modes.

| RT (Minute) | Chemical Name | Measured Mass (M+H)+ | Measured Mass (M-H)− | Molecular Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.63 | 11-aminoundecanoic acid | 202.1802 | 200.1655 | C11H23O2N |

| 7.52 | 12-aminododecanoic acid | 216.1958 | 214.1812 | C12H25O2N |

| 9.44 | dimer of 11-aminoundecanoic acid | 385.3431 | 383.3277 | C22H44O3N2 |

| 10.15 | dimer of 12-aminododecanoic acid | 413.3742 | 411.3590 | C24H48O3N2 |

Identification of Cyclic Polytetramethylene Ethers and Poly(Tetramethylene Ether) Glycols

The spectra of peaks at RTs 20.334 min, 24.251 min, 27.534 min, and 31.434 min in the GC-MSD chromatogram displayed the same spectrum as shown in Figure S7. The fragment ion with the highest mass is at m/z 143.1. The extraction sample was further analyzed using GC-QTOF in the EI mode at 70 EV and 13 EV. However, there is no significant improvement at 13 EV to obtain the molecular ion of the peak. The sample was then analyzed with GC-QTOF in PCI mode using methane, isobutane, and ammonia as reagent gases, respectively. The RTs of these four peaks analyzed in GC-QTOF were at 19.519 min, 23.524 min, 26.870 and 30.805 min, eluted slightly earlier than those from GC–MSD due to different column used. Using the peak eluted at 30.805 min as an example, the selection of PCI reagent gases (Figure 3) has significant impact on compound molecular ion generation. The protonated molecular ion using methane as reagent gas in PCI mode is not very stable. Using isobutane as the reagent gas, the protonated molecular ion is shown with a relative low intensity. When ammonia was used as the reagent gas, the dominant molecular ion mass of [M + H]+ and [M+NH4]+ was observed at m/z 505.4117 and m/z 522.4385, respectively. The molecular formula of this compound can be proposed as C28H56O7 based on accurate mass of GC-TOF data. Furthermore, the fragment ions of this compound at m/z 433.3540, 361.2955, 289.2378, 217.1798, and 145.1224 showed the sequential loss of each C4H8O (m/z 72) moiety in the ion series of 505.4117→ 433.3540 → 361.2955 → 289.2378 → 217.1798 → 145.1224. Based on the fragmentation pattern in ammonia and isobutane assisted PCI spectra and accurate mass of [M + H]+, the compound at 31.434 min (GC–MSD) or 30.805 min (GC-QTOF) is identified to be (C4H8O)7 (35-crown-7). The IUPAC name is 1,6,11,16,21,26,31-heptaoxacyclopentatriacontane, a type of cyclic polyether with a 4-carbon repeat unit ether. Similarly, the components at RTs 20.334 min, 24.251 min, and 27.534 min are identified to be (C4H8O)4 (20-crown-4), (C4H8O)5 (25-crown-5) and (C4H8O)6 (30-crown-6) in the GC–MSD chromatogram (Chart 2C), respectively.

Figure 3.

PCI spectra of peak at 30. 805 min in GC-QTOF using methane, isobutane, and ammonia as reagent gases.

From the LC–MS data obtained with Orbitrap Exploris 120, these compounds were also confirmed, and additional cyclic polytetramethylene ethers were identified. The cyclic polytetramethylene ethers (OC4H8)y, where y is 4 to 16, identified in the extraction samples, are listed in Table 3. All cyclic polytetramethylene ethers showed only two dominant product ions at m/z 73 and m/z 55 in MS2 spectra under current HCD conditions.

Table 3. List of Cyclic Polytetramethylene Ether, (OC4H8)y, Identified.

| RT (Minute) | Name | Measured Mass (M+H)+/(M+Na)+ | Repeating Unit (y) | Molecular Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10.40 | 20-crown-4 | 289.2375/311.2194 | 4 | C16H32O4 |

| 11.32 | 25-crown-5 | 361.2951/383.2770 | 5 | C20H40O5 |

| 12.05 | 30-crown-6 | 433.3528/455.3347 | 6 | C24H48O6 |

| 12.57 | 35-crown-7 | 505.4102/527.3921 | 7 | C28H56O7 |

| 12.99 | 40-crown-8 | 577.4680/599.4498 | 8 | C32H64O8 |

| 13.36 | 45-crown-9 | 649.5256/671.5074 | 9 | C36H72O9 |

| 13.78 | 50-crown-10 | 721.5828/743.5644 | 10 | C40H80O10 |

| 14.24 | 55-crown-11 | 793.6408/815.6223 | 11 | C44H88O11 |

| 14.78 | 60-crwon-12 | 865.6981/887.6795 | 12 | C48H96O12 |

| 15.41 | 65-crown-13 | 937.7549/959.7369 | 13 | C52H104O13 |

| 16.14 | 70-crown-14 | 1009.8129/1031.7948 | 14 | C56H112O14 |

| 17.04 | 75-crown-15 | 1081.8700/1103.8522 | 15 | C60H120O15 |

| 17.99 | 80-crown-16 | 1153.9290/1175.9104 | 16 | C64H128O16 |

From the LC–MS sample analysis, linear poly(tetramethylene ether) glycols (PTMEG), HO(C4H8O)yH, where y = 4 to 20, were also identified (Chart 2D). The retention times and accurate mass of protonated and sodium adduct ions are listed in Table 4. The MS2 spectra fragmentation patterns of this group of chemicals are the same as that of cyclic polytetramethylene ether with two dominant product ions at m/z 73 and m/z 55 in the current HCD condition. Linear poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol is a commercially available starting raw material to produce polyurethane and Pebax.

Table 4. List of Poly(tetramethylene ether) Glycols, HO(C4H8O)yH, Identified.

| RT (Minute) | Measured Mass (M+H)+/(M+Na)+ | Repeating Unit (y) | Molecular Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8.48 | 307.2481/329.2300 | 4 | C16H34O5 |

| 9.51 | 379.3060/401.2879 | 5 | C20H42O6 |

| 10.31 | 451.3633/473.3451 | 6 | C24H50O7 |

| 10.92 | 523.4209/545.4028 | 7 | C28H58O8 |

| 11.40 | 595.4786/617.4604 | 8 | C32H66O9 |

| 11.82 | 667.5358/689.5178 | 9 | C36H74O10 |

| 12.19 | 739.5936/761.5752 | 10 | C40H82O11 |

| 12.52 | 811.6505/833.6321 | 11 | C44H90O12 |

| 12.79 | 883.7081/905.6896 | 12 | C48H98O13 |

| 13.02 | 955.7656/977.7471 | 13 | C52H106O14 |

| 13.25 | 1027.8242/1049.8063 | 14 | C56H114O15 |

| 13.49 | 1099.8816/1121.8628 | 15 | C60H122O16 |

| 13.74 | 1171.9395/1193.9210 | 16 | C64H130O17 |

| 14.03 | 1243.9979/1265.9788 | 17 | C68H138O18 |

| 14.39 | 1316.0544/1338.0364 | 18 | C72H146O19 |

| 14.83 | 1388.1071/1410.0944 | 19 | C76H154O20 |

| 15.29 | 1460.1650/1482.1517 | 20 | C80H162O21 |

Identification of Cyclic and Linear Poly(tetramethylene ether) Glycol Adipate

The EI spectra of peaks at RTs 20.035 min, 23.961 min, 27.296 min, and 31.087 min in GC–MSD chromatogram are very similar to cyclic polytetramethylene ether. The main differences among the spectra are the intensity of m/z at 129.1, and a few high mass ions with low intensity. The typical mass spectrum of this group of compounds is shown in Figure S8 using a peak at RT 31.087 min as an example. The chromatogram in GC-QTOF analysis showed this peak at RT 30.414 min.

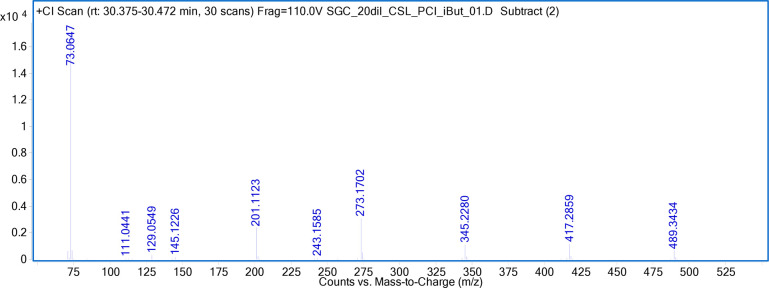

Based on the accurate mass measurement of (M+H)+ at m/z 489.3434 in the GC-QTOF using isobutane as the reagent gas (Figure 4), the molecular formula of this compound is proposed to be C26H48O8. The fragmentation pattern in PCI spectrum showed the loss of one C4H8O moiety for each ion from the next higher mass in the ion series of 489.3434 → 417.2859 → 345.2280 → 273.1702 → 201.1123 → 129.0549, with a total of five C4H8O moieties. The molecular formula of fragment at m/z 129.0549 is (C6H8O3+H)+, which contains two unsaturated bonds, suggesting two carbonyl groups and one C4H8O unit. Based on the structure of Pebax, this moiety of C6H8O3 can be determined to be the chain extender, CO–C4H8–CO–O, of Pebax. Therefore, the structure of this peak is elucidated to be CO–C4H8–CO–O–(C4H8O)5. The peak at 31.087 min is identified to be 1,6,11,16,21,26-hexaoxacyclodotriacontane-27,32-dione. Similarly, the peaks at RTs 20.035 min, 23.961 min, and 27.296 min are identified to 1,6,11-trioxacycloheptadecane-12,17-dione, 1,6,11,16-tetraoxacyclodoeicosane-17,22-dione, and 1,6,11,16,21-pentaoxacycloheptaeicosane-22,27-dione, respectively. These compounds belongs to cyclic poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipate family (Chart 2E).

Figure 4.

PCI spectrum (isobutane as reagent gas) of the peak at RT 30.414 min in GC-QTOF.

The MS2 fragmentation spectrum of m/z 489. 3418 in LC-Orbitrap MS is showed in Figure 5. The fragment ion searching (FISh) evaluation showed that 12 major fragment ions of m/z 489. 3418 in the spectrum match to the fragment ions generated by in silico fragmentation of putative structures with a coverage score of 75%, further confirmed the elucidated structure of 1,6,11,16,21,26-hexaoxacyclodotriacontane-27,32-dione. The (M+H)+ ion at m/z 489.3418 (C26H48O8+H)+ observed in LC-MS analysis was in agreement with (M+H)+ at m/z 489.3434 in PCI mode deciphered in GC-QTOF analysis.

Figure 5.

MS2 spectrum of m/z 489.3418 acquired in orbitrap MS and FISh coverage of 1,6,11,16,21,26-hexaoxacyclodotriacontane-27,32-dione

From the data obtained in the LC–Orbitrap MS analysis, a series of cyclic poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipates, CO–C4H8–CO–O–(C4H8O)y, where y equals 3 to 18 are identified and listed in Table 5 and Chart 2E.

Table 5. Cyclic Poly(tetramethylene ether) Glycol Adipate, CO–C4H8–CO–O–(C4H8O)y, Identified in LC–MS Positive Mode.

| RT (Minute) | Measured Mass (M+H)+/(M+Na)+ | Repeating Unit (y) | Molecular Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10.21 | 345.2279/367.2094 | 3 | C18H32O6 |

| 11.08 | 417.2855/439.2670 | 4 | C22H40O7 |

| 11.73 | 489.3427/511.3246 | 5 | C26H48O8 |

| 12.31 | 561.4005/583.3823 | 6 | C30H56O9 |

| 12.70 | 633.4577/655.4396 | 7 | C34H64O10 |

| 13.05 | 705.5425/727.4974 | 8 | C38H72O11 |

| 13.36 | 777.5724/799.5538 | 9 | C42H80O12 |

| 13.71 | 849.6302/871.6117 | 10 | C46H88O13 |

| 14.13 | 921.6879/943.6691 | 11 | C50H96O14 |

| 14.63 | 993.7461/1015.7274 | 12 | C54H104O15 |

| 15.19 | 1065.8042/1087.7858 | 13 | C58H112O16 |

| 15.90 | 1137.8596/1159.8434 | 14 | C62H120O17 |

| 16.61 | 1209.9158/1231.9009 | 15 | C66H128O18 |

In both LC–MS positive and negative ionization modes analyses, linear poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipates with a hydroxyl and a carboxylic group in each terminal, HOCO–C4H8–CO–O–(C4H8O)yH, where y equals 3 to 16 were also identified (Chart 2F). The retention times and the measured accurate masses of this group of compounds are listed in Table 6. The fragmentation pattern of the linear poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipate in the MS2 spectrum is identical to that of its cyclic counterpart, and the only difference is it is 18 mass unit (H2O) higher than its counterpart in the (M+H)+ ion (Figure S9).

Table 6. Linear Poly(tetramethylene ether) Glycol Adipates, HOCO–C4H8–CO–O–(C4H8O)yH.

| RT (Minute) | Measured Mass (M+H)+/(M+Na)+ | Measured Mass (M-H)− | Repeating Unit (y) | Molecular Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8.93 | 363.2383/385.2202 | 361.2231 | 3 | C18H34O7 |

| 9.79 | 435.2956/457.2776 | 433.2804 | 4 | C22H42O8 |

| 10.46 | 507.3533/529.3353 | 505.3380 | 5 | C26H50O9 |

| 11.00 | 579.4108/601.3928 | 577.3953 | 6 | C30H58O10 |

| 11.45 | 651.4681/673.4499 | 649.4525 | 7 | C34H66O11 |

| 11.84 | 723.5256/745.5076 | 721.5107 | 8 | C38H74O12 |

| 12.20 | 795.5820/817.5646 | 793.5678 | 9 | C42H82O13 |

| 12.48 | 867.6395/889.6219 | 865.6249 | 10 | C46H90O14 |

| 12.74 | 939.6998/961.6796 | 937.6829 | 11 | C50H98O15 |

| 12.95 | 1011.7563/1033.7375 | 1009.7398 | 12 | C54H106O16 |

| 13.17 | 1083.8239/1105.7957 | 1081.7977 | 13 | C58H114O17 |

| 13.40 | 1155.8739/1177.8518 | 1153.8551 | 14 | C62H122O18 |

| 13.62 | 1227.9263/1249.9116 | 1225.9130 | 15 | C66H130O19 |

| 13.89 | 1299.9838/1321.9686 | 1297.9690 | 16 | C70H138O20 |

Figure S9 showed the evaluation of the MS2 fragmentation spectrum of m/z 435.2945 using the FISh scoring node in Compound Discoverer software with the proposed chemical structure of this compound. The FISh search showed 12 major fragment ions in the spectrum match to the fragmentation pattern of the proposed structure, C22H42O8, while only two ions in the spectrum are not found in the predicted fragments in the FISh analysis. The result further confirmed the proposed structure with FISh coverage scores of 86%.

Identification of Cyclic and Linear Poly(tetramethylene ether) Glycol Adipamide

In both LC–MS positive and negative ionization mode analyses, linear poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipamides with a hydroxyl and a carboxylic group as its terminus, HO[OC–(C11H22)NH]x–COC4H8COO(C4H8O)yH, where x is 1 or 2, and y is 0 and 3 to 13, are identified (Chart 2H). The retention times and the accurate masses observed in both positive and negative ionization analyses of this group of compounds are listed in Table 7. Since only polyamide with a chain length of 12 being identified in this class of chemicals, the results suggest this group of leachables is the degradation product from Pebax 55D and Pebax 40D.

Table 7. Identified Linear Poly(tetramethylene ether) Glycol Adipamide, HO[OC–(C11H22)NH]x–COC4H8COO(C4H8O)yH.

| RT (Minute) | Measured Mass (M+H)+/(M+Na)+ | Measured Mass (M-H)− | Repeating Unit (x) | Repeating Unit (y) | Molecular Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9.74 | 344.2434/366.2253 | 342.2281 | 1 | 0 | C18H33O5N |

| 11.31 | 560.4141/582.3983 | 558.4006 | 1 | 3 | C30H57O8N |

| 11.48 | 541.4216/563.4034 | 539.4063 | 2 | 0 | C30H56O6N2 |

| 11.71 | 632.4741/654.4561 | 630.4579 | 1 | 4 | C34H65O9N |

| 11.79 | 704.5313/726.5131 | 702.5153 | 1 | 5 | C38H73O10N |

| 12.10 | 776.5887/798.5704 | 774.5732 | 1 | 6 | C42H81O11N |

| 12.24 | 829.6510/851.6331 | 827.6363 | 2 | 4 | C46H88O10N2 |

| 12.40 | 848.6464/870.6277 | 846.6308 | 1 | 7 | C46H89O12N |

| 12.64 | 920.7037/942.6854 | 918.6882 | 1 | 8 | C50H97O13N |

| 12.67 | 901.7084/923.6900 | 899.6933 | 2 | 5 | C50H96O11N2 |

| 12.84 | 992.7634/1014.7430 | 990.7465 | 1 | 9 | C54H105O14N |

| 12.85 | 973.7669/995.7487 | 971.7510 | 2 | 6 | C54H104O12N2 |

| 13.02 | 1064.8217/1086.8018 | 1062.8036 | 1 | 10 | C58H113O15N |

| 13.16 | 1045.8253/1067.8066 | 1043.8087 | 2 | 7 | C58H112O13N2 |

| 13.17 | 1136.8857/1158.8585 | 1134.8600 | 1 | 11 | C62H121O16N |

| 13.34 | 1117.8813/1139.8633 | 1115.8667 | 2 | 8 | C62H120O14N2 |

| 13.65 | 1208.9282/1230.9171 | 1206.9163 | 1 | 12 | C66H129O17N |

| 13.91 | 1280.9896/1302.9745 | 1278.9749 | 1 | 13 | C70H137O18N |

The FISh scoring node in Compound Discoverer software matches fragment ions in MS2 spectra to in silico fragment ions of the proposed structures of (M+H)+ ions at m/z 344.2423 (Figure S10) and m/z 560.4151 (Figure S11), with a coverage score of 82% and 74%, respectively, further confirming the proposed structures.

Based on accurate mass, isotope ratio, and fragmentation pattern obtained with LC–Orbitrap MS positive ionization analysis, another group of chemicals, cyclic poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipamide, OC–(C11H22)NH–COC4H8COO(C4H8O)y, where y equals 3 to13, is identified (Chart 2G). The retention times and accurate masses of this group of compounds are listed in Table 8. The fragmentation patterns of cyclic poly(tetramethylene ether glycol) adipamides in their MS2 spectra were identical to that of their linear counterparts, except their (M+H)+ ion is 18 mass unit (H2O) less than their corresponding compounds with a linear structure.

Table 8. Identified Cyclic Poly(tetramethylene ether) Glycol Adipamide, OC–(C11H22)NH–COC4H8COO(C4H8O)y.

| RT (Minute) | Measured Mass (M+H)+/(M+Na)+ | Repeating Unit (y) | Molecular Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12.24 | 542.4056/564.3875 | 3 | C30H55O7N |

| 12.64 | 614.4630/636.4449 | 4 | C34H63O8N |

| 12.93 | 686.5203/708.5022 | 5 | C38H71O9N |

| 13.25 | 758.5783/780.5601 | 6 | C42H79O10N |

| 13.54 | 830.6357/852.6173 | 7 | C46H87O11N |

| 13.87 | 902.6932/924.6749 | 8 | C50H95O12N |

| 14.29 | 974.7504/996.7325 | 9 | C54H103O13N |

| 14.72 | 1046.8085/1068.7908 | 10 | C58H111O14N |

| 15.32 | 1118.8658/1140.8477 | 11 | C62H119O15N |

| 15.99 | 1190.9246/1212.9059 | 12 | C66H127O16N |

| 16.73 | 1262.9844/1284.9640 | 13 | C70H135O17N |

Conclusions

The study investigated leachable chemical composition of catheter devices based on Pebax and nylon-11 polymer materials. The process of chemical analysis provided in this study can be a useful workflow to characterize extractable and leachable materials in medical devices. Polylactams, polyamides, polytetramethylene ethers, poly(tetramethylene ether) glycols, poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipates, poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipamides were identified as leachable chemicals in 40% ethanol extract of the catheter device. The structures of these compounds are illustrated in Chart 2. Monomer, dimer, and trimer of undecalactam, 11-aminoundecanoic acid, and dimer of 11-aminoundecanoic acid are leachables derived from nylon-11 based on the chain length of this group of compounds. Monomer, dimer, and trimer of dodecalactam, 12-aminododecanoic acid and dimer of 12-aminododecanoic acid are derived from Pebax 40D and Pebax 55D material in the device. Polytetramethylene ether, poly(tetramethylene ether) glycols, poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipates, poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol adipamides are leachables from Pebax material. This is the first time that a comprehensive list of identified extractable and leachable chemicals in catheter devices manufactured with Pebax and nylon-11 was established with reference spectra using GC–MS and LC–MS analyses. The leachable and extractable materials derived from polyvinylpyrrolidone are not identified in the catheter device based on both GC–MS and LC–MS data.

The structural library of these compounds can be established in the compound database to facilitate future chemical characterization studies of medical devices constructed with similar material. In addition, the structural information on leachable chemicals derived from Pebax material and nylon-11 will enable a better toxicological assessment of the relevant medical device and will determine if additional biocompatibility testing is needed.

The LC–MS workflow using accurate mass, isotope ratio, MS2 spectra from the HRAM-MS and FISh searching scoring algorithm presented herein is a powerful approach for the chemical characterization of medical devices manufactured with different polymer classes. Prior knowledge of materials used in the medical devices and empirical molecular formula provided a hint to establish the expected compound list. The FISh Scoring analysis matches fragment ions acquired in MS2 spectra to the theoretical fragment ions of expected compounds generated through an in silico algorithm. The higher FISh coverage score suggests a good match between the identified compound and the chemical structure of the expected compound. This workflow proves to be a successful approach to establish with confidence the leachable chemical profile in the medical devices studied. NIST library search of GC–MS EI spectra enables a quick identification of all known compounds in the database. Due to limited polymer related structures in the NIST library, the establishment of a user library in GC–MS is essential to identify rapidly and unambiguously semivolatile extractable and leachable materials in polymers. As demonstrated in this study, the technique using PCI in GC-QTOF to generate the accurate mass of the molecular ion and its fragmentation pattern proves to be a useful approach to identify and structurally characterize semivolatile leachables. The GC–MS spectra of identified compounds using this workflow can also be added to the user library, providing reference spectra for rapid extractable and leachable screening. In combination of information acquired in GC–MS and LC–MS analyses, the extractables and leachables in the medical devices are characterized with confidence.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Dr. Matthew Curtis from Agilent Technology for providing GC-QTOF data and insight discussion.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c06473.

Selected GC–MS and LC–MS spectra and FISh coverage of MS2 spectra analyzed in Compound Discoverer software (PDF)

This work was funded by Abbott Vascular Inc., Santa Clara, CA 95054–2807.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- US FDA Use of International Standard ISO 10993-1, Biological evaluation of medical devices - Part 1: Evaluation and testing within a risk management process; US FDA, No. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ISO ISO 10993-1:2018 Biological evaluation of medical devices - Part 1: Evaluation and testing within a risk management process; International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ISO ISO/TS 21726:2019 - Biological evaluation of medical devices - Application of the threshold of toxicological concern (TTC) for assessing biocompatibility of medical device constituents; International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ISO ISO 10993–12:2021 Biological evaluation of medical devices - Part 12: Sample preparation and reference materials; International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ISO ISO 10993–18:2020 Biological evaluation of medical devices - Part 18: Chemical characterization of medical device materials within a risk management process; International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jenke D.; Liu N.; Hua Y.; Swanson S.; Bogseth R. A means of establishing and justifying binary ethanol/water mixtures as simulating vehicles in extractables studies. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 2015, 69, 366–382. 10.5731/pdajpst.2015.01046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahladakis J. N.; Velis C. A.; Weber R.; Lacovidou E.; Purnell P. An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: Migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling. J. Haz. Mater. 2018, 344, 177–199. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadros-Rodríguez L.; Lazúen-Muros M.; Ruiz-Samblás C.; Navas-Iglesias N. Leachables from plastic materials in contact with drugs. State of the art and review of current analytical approaches. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 583, 119332. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czuba L.Application of plastics in medical devices and equipment. In handbook of polymer applications in medicine and medical devices; Modjarrad K., Ebnesajjad S.,, Ed.; Elsevier Inc., 2014; pp 9–19. 10.1016/B978-0-323-22805-3.00002-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenke D. Safety risk categorization of organic extractables associated with polymers used in packaging, delivery and manufacturing systems for parenteral drug products. Pharm. Res. 2015, 32, 1105–1127. 10.1007/s11095-014-1523-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenz F.; Linke S.; Simat T. J. Linear and cyclic oligomers in PET, glycol-modified PET and Tritan used for food contact materials. Food Addit. Contam. 2021, 38, 160–179. 10.1080/19440049.2020.1828626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Bueno M. J.; Gómez Ramos M. J.; Bauer A.; Fernández-Alba A. R. An overview of non-targeted screening strategies based on high resolution accurate mass spectrometry for the identification of migrants coming from plastic food packaging materials. TrAC-Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 110, 191–203. 10.1016/j.trac.2018.10.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carrero-Carralero C.; Escobar-Arnanz J.; Ros M.; Jiménez-Falcao S.; Sanz M. L.; Ramos L. An untargeted evaluation of the volatile and semi-volatile compounds migrating into food simulants from polypropylene food containers by comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Talanta 2019, 195, 800–806. 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisler S.; Christensen J. H. Non-target screening for the identification of migrating compounds from reusable plastic bottles into drinking water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 429, 128331. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsugawa H.; Cajka T.; Kind T.; Ma Y.; Higgins B.; Ikeda K.; Kanazawa M.; VanderGheynst J.; Fiehn O.; Arita M. MS-DIAL: data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 523–526. 10.1038/nmeth.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman E. M.; Oktem B.; Isayeva I. S.; Liu J.; Wickramasekara S.; Chandrasekar V.; Nahan K.; Shin H. Y.; Zheng J. Chemical Characterization and Non-targeted Analysis of Medical Device Extracts: A review of current approaches, gaps, and emerging practices. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 939–963. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.1c01119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eustache R.-P.Poly(ether-b-amide) thermoplastic elastomers: structure, properties and applications. In Handbook of Condensation Thermoplastic Elastomers; Fakirov S., Ed.; Wiley-VCH, 2005; pp 263–281. 10.1002/3527606610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Wang Z.; Zhu P.; Liu X.; Wang L.; Dong X.; Wang D. Microphase separation/crosslinking competition-based ternary microstructure evolution of poly(ether-b-amide). RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 6934–6942. 10.1039/D0RA10627E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haishima Y.; Hayashi Y.; Yagami T.; Nakamura A. Elution of bisphenol-A from hemodialyzers consisting of polycarbonate and polysulfone resins. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001, 58, 209–215. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani H.; Nakamura A. Formation of 4,4′-methylenedianiline in polyurethane potting materials by either γ-ray or autoclave sterilization. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1991, 25, 1275–1286. 10.1002/jbm.820251008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes D. W.; Chandrasekar V.; Woolford S. E.; Ludwig K. B. Predicting the effects of composition, molecular size and shape, plasticization, and swelling on the diffusion of aromatic additives in block copolymers. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 6137–6148. 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b00690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth J. P.; Xu J.; Wilkes G. L. Solid state structure–property behavior of semicrystalline poly(ether-block-amide) PEBAX® thermoplastic elastomers. Polymer 2003, 44, 743–756. 10.1016/S0032-3861(02)00798-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed H. A.; Assem Y.; Said R.; El-Masry A. M. Synthesis of polyesteramides: poly(ethylene adipate amide) and poly(ethylene succinate amide) and their application as corrosion inhibitors in paint formulations. J. of Coat. Technol. Res. 2018, 15, 967–981. 10.1007/s11998-017-0027-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biemond G. J. E.; Feijen J.; Gaymans R. J. Poly(ether amide) segmented block copolymers with adipic acid based tetraamide segments. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 105, 951–963. 10.1002/app.26202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pebax Elastomers; Arkema Inc., 2018, https://www.polyonedistribution.com/sites/default/files/files/featured/Pebax-Elastomers-Brochureoptimized%20%281%29.pdf.

- Pebax MED Polyether Block Amide; Foster Polymer Distribution, 2013, https://www.fosterpolymers.com/polymers/pebax.php.

- Chemical Information Review Document for N-Butylbenzenesulfonamide; US Dept Health and Human Services, 2010, https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/htdocs/chem_background/exsumpdf/n_butylbenzensulfonamide_508.pdf.

- Kim H.; Choi M. S.; Ji Y. S.; Kim I. S.; Kim G. B.; bae I. Y.; Gye M. C.; Yoo H. H. Pharmacokinetic Properties of Acetyl Tributyl Citrate, a Pharmaceutical Excipient. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 177. 10.3390/pharmaceutics10040177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucci V.; Vallo C. Efficiency of 2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone for the photopolymerization of methacrylate monomers in thick sections. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 123, 418–425. 10.1002/app.34473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.