Summary

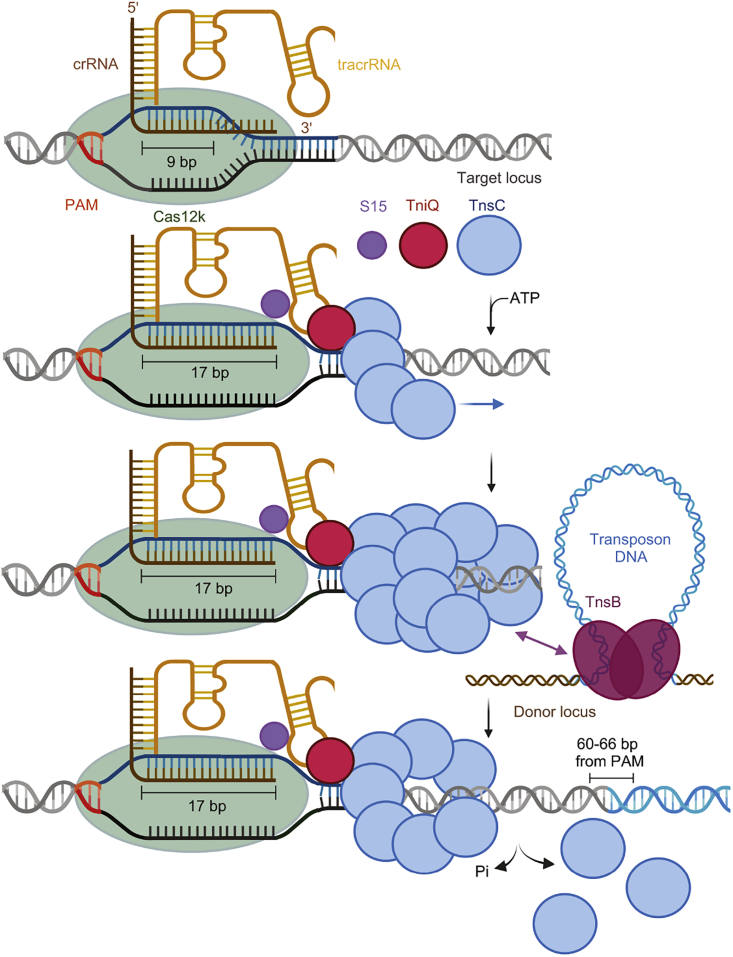

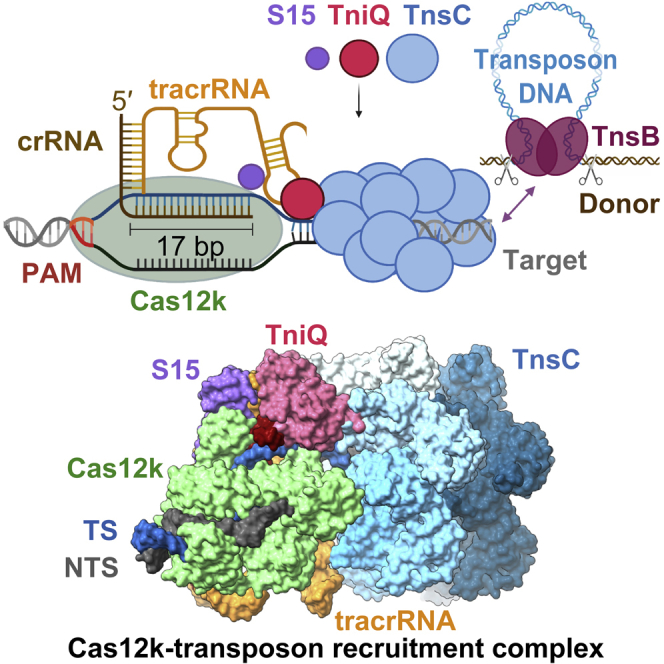

CRISPR-Cas systems have been co-opted by Tn7-like transposable elements to direct RNA-guided transposition. Type V-K CRISPR-associated transposons rely on the concerted activities of the pseudonuclease Cas12k, the AAA+ ATPase TnsC, the Zn-finger protein TniQ, and the transposase TnsB. Here we present a cryo-electron microscopic structure of a target DNA-bound Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex comprised of RNA-guided Cas12k, TniQ, a polymeric TnsC filament and, unexpectedly, the ribosomal protein S15. Complex assembly, mediated by a network of interactions involving the guide RNA, TniQ, and S15, results in R-loop completion. TniQ contacts two TnsC protomers at the Cas12k-proximal filament end, likely nucleating its polymerization. Transposition activity assays corroborate our structural findings, implying that S15 is a bona fide component of the type V crRNA-guided transposon machinery. Altogether, our work uncovers key mechanistic aspects underpinning RNA-mediated assembly of CRISPR-associated transposons to guide their development as programmable tools for site-specific insertion of large DNA payloads.

Keywords: CRISPR, CRISPR-Cas system, transposon, CRISPR-associated transposons, CAST, Cas12k, TnsC, TniQ, TnsB, S15

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Cryo-EM structure of CRISPR RNA-guided Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex

-

•

TniQ interacts with tracrRNA and facilitates R-loop completion

-

•

TniQ connects Cas12k with TnsC ATPase filament end on target DNA

-

•

Ribosomal protein S15 is a bona fide component of type V CRISPR-associated transposons

Cryo-EM structure of a type V CRISPR-associated transposon recruitment complex reveals the mechanism linking the RNA-guided pseudonuclease Cas12k and the transposition machinery, and the involvement of a ribosomal protein in the assembly, providing a framework for the development of novel programmable gene-insertion technologies.

Introduction

The canonical function of prokaryotic CRISPR-Cas systems is to provide adaptive immunity against invading mobile genetic elements, including transposons, plasmids, and phages.1,2 This relies on Cas protein effector complexes that mediate CRISPR RNA (crRNA)-guided recognition of target nucleic acids and their subsequent nucleolytic degradation.3,4 Several Tn7-like transposons have co-opted RNA-guided type I, subtype F (I-F), I-B, and V-K CRISPR-Cas systems to direct transposon DNA insertion into specific target sites.5,6,7,8,9,10,11 The CRISPR-Cas modules of CRISPR-associated transposons (CASTs) are comprised of either a nuclease-deficient multisubunit Cascade complex4 in type I systems8 or a single catalytically inactive Cas12k pseudonuclease in type V-K systems7 and are embedded between the left and right transposon end sequences together with a CRISPR spacer-repeat array and several genes encoding the transposon machinery. The DNA-targeting effectors bind to target sites specified by the crRNA guides, recruiting the transposase to catalyze transposon DNA insertion at a fixed distance downstream of the specific target DNA site. As CAST systems often contain additional defense systems as cargos, these elements have been hypothesized to mediate horizontal gene transfer of host defense systems within bacterial populations by using other transposons and plasmids as shuttle vectors.12 While crRNAs encoded from the CRISPR arrays guide transposon insertion preferentially into other mobile genetic elements, delocalized crRNAs target integration into host chromosomal sites for transposon homing in type V-K systems.10

For type V-K systems, target site recognition is mediated by a CRISPR effector complex comprised of Cas12k programmed with a dual guide RNA structure comprised of crRNA and a trans-activating RNA (tracrRNA)13 or an artificial single-molecule guide RNA (sgRNA) fusion.7,14 In turn, transposition requires three transposon proteins: the AAA+ ATPase TnsC, the transposase TnsB, and the zinc-finger (Zn-finger) protein TniQ.7 Biochemical and structural studies of a type V CAST system from Scytonema hofmanni (ShCAST) revealed that Cas12k-mediated DNA targeting depends on the intricate architecture of the tracrRNA that serves as a scaffold to correctly position Cas12k and the crRNA guide for the recognition of complementary targets.15,16 Upon binding to a 5′-GTN-3′ protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) in the target DNA,7,17 Cas12k initiates guide RNA hybridization to the target strand (TS) DNA, which results in the formation of an incomplete R-loop structure, suggesting that further rearrangements occurring upon recruitment of the downstream transposon machinery are required to elicit further hybridization between the guide RNA and the TS DNA.15,16 In turn, structural and biochemical studies revealed that TnsC assembles ATP-dependent helical filaments on double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), remodeling its duplex geometry.15,18 Based on homology to the prototypical Escherichia coli (E. coli) Tn7 transposon19 and analysis of transposase-mediated integration events,20 the DDE-type TnsB transposase has been postulated to catalyze the 3′-DNA strand breakage and transfer reactions required for a replicative transposition mechanism, resulting in transposon end-nicking and ligation to a target DNA at sites located 60–66 base pairs (bp) downstream of the PAM.7 TnsC is thought to recruit and activate TnsB at the target site.19 Concurrently, TnsB interacts with the TnsC filament to trigger its disassembly by stimulating the ATPase activity of TnsC.15,18,21 This prevents insertion of additional transposon copies into the same site and ensures target immunity, which is a conserved feature of transposons harboring coupled transposase and AAA+ ATPase components.7,8,22,23,24 TnsC forms a hexameric ring when bound to dsDNA in the ADP-bound state, suggesting that this intermediate might bridge between the Cas12k-DNA targeting complex and TnsB upon ATP hydrolysis, thereby providing a molecular ruler mechanism for insertion site definition.18 However, the structural details of a complete CRISPR-transposon assembly remain elusive. The function of TniQ is also presently unclear. In type V-K systems, TniQ directly interacts with one end of the TnsC filament and has been implicated in the regulation of its polymerization.15,18 Conversely, in type I-F3 systems, a TniQ homodimer is an integral component of the DNA targeting complex together with the Cascade.25,26,27

CASTs constitute programmable, targeted DNA-integration machineries that have been repurposed as site-specific, homology-independent DNA-insertion tools to engineer bacterial hosts28,29 and communities.30 However, their application in eukaryotic cells has so far been hindered, in part by limited understanding of their underlying molecular mechanisms. Here, we used cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to visualize the structure of a Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex from ShCAST,7 revealing how guide-RNA-bound Cas12k, TniQ, TnsC and, unexpectedly, the ribosomal protein S15 cooperatively assemble with each other on target DNA. The structure identifies TniQ as a key structural element that bridges Cas12k and TnsC via interactions with the tracrRNA and the PAM-distal end of a complete R-loop structure, priming the nucleation of the TnsC filament in a productive orientation. We further identify the host-encoded protein S15 as a bona fide component of the crRNA-guided transposition machinery that promotes complex assembly and enhances transposition activity by a structural mechanism reminiscent of its function in cellular translation. Altogether, our work elucidates how a CRISPR-Cas effector recruits its cognate transposon factors to initiate RNA-guided transposition and will inform reconstitution of this machinery for programmable site-specific insertion of large DNA payloads in genome-engineering applications.

Results

Reconstitution and structure of Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex

To obtain structural insights into the interaction between Cas12k and the transposon components in type V CASTs, we sought to reconstitute guide-RNA-programmed Cas12k together with TnsC and TniQ on target DNA. To this end, we first bound a sgRNA, comprised of sequences corresponding to the crRNA guide and a tracrRNA, and an internally unpaired target-DNA oligonucleotide duplex to Cas12k immobilized on a solid support and subsequently incubated the resulting complex with TnsC and TniQ in the presence of ATP to trigger TnsC filament assembly. After extensive washing and elution, the sample was vitrified and imaged using cryo-EM for single-particle analysis. By stringent selection of Cas12k particles displaying adjacent filament-like densities as well as subsequent two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) classification, we were able to obtain a reconstruction of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex at an overall resolution of 3.3 Å (Figures 1 and S1; Table S1).

Figure 1.

Cryo-EM structure of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex

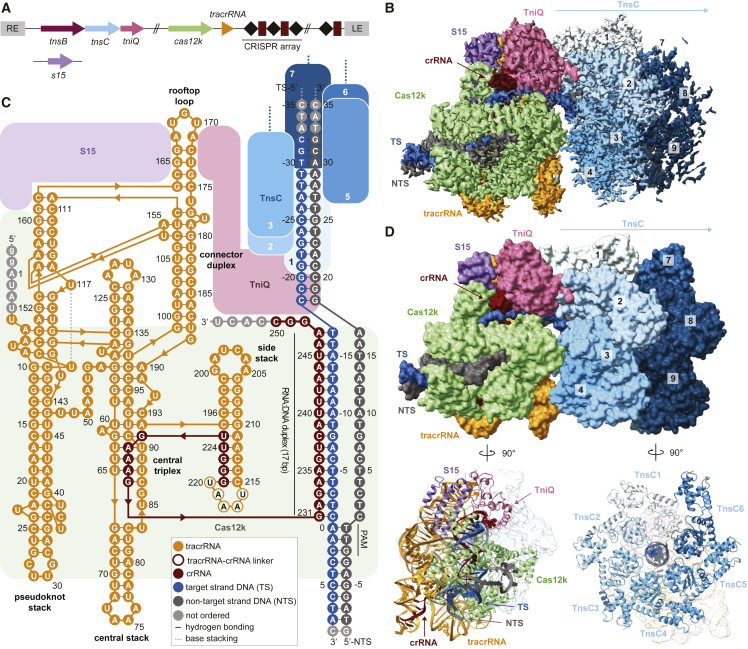

(A) Schematic diagram of the type V-K ShCAST 7 and the S15-encoding gene. LE, RE: left and right transposon ends, respectively. Spacers are represented as squares, repeats as diamonds.

(B) Cryo-EM density map of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex. Density for nine TnsC protomers (TnsC1–TnsC9) is shown.

(C) Schematic diagram of the sgRNA structure and R-loop architecture indicating interactions between nucleic acids and protein components of the complex.

(D) Structural model of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex (surface and cartoon representations). TS, target strand; NTS, non-target strand.

Figure S1.

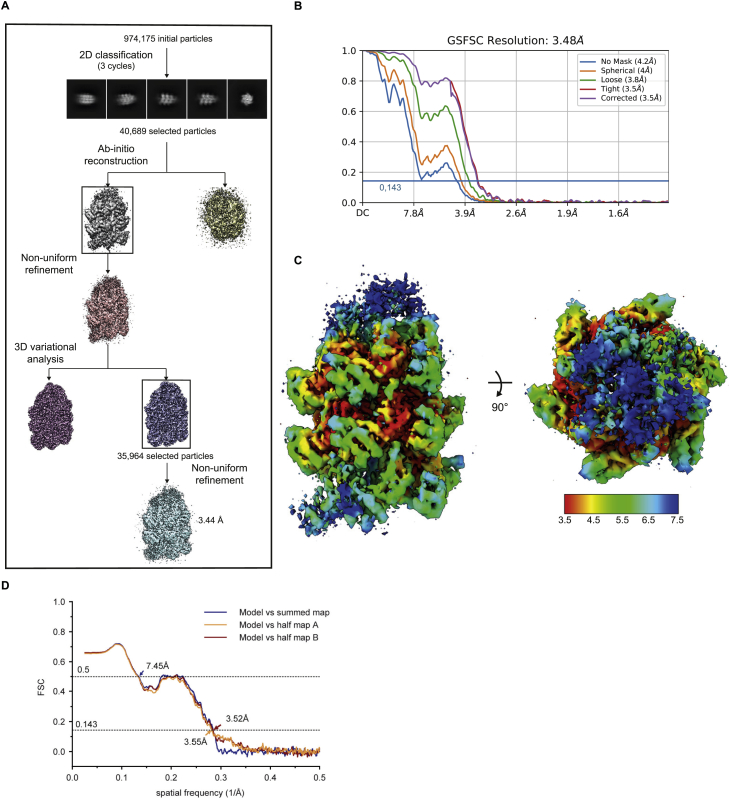

Cryo-EM data processing workflow for the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex, related to Figure 1 and STAR Methods

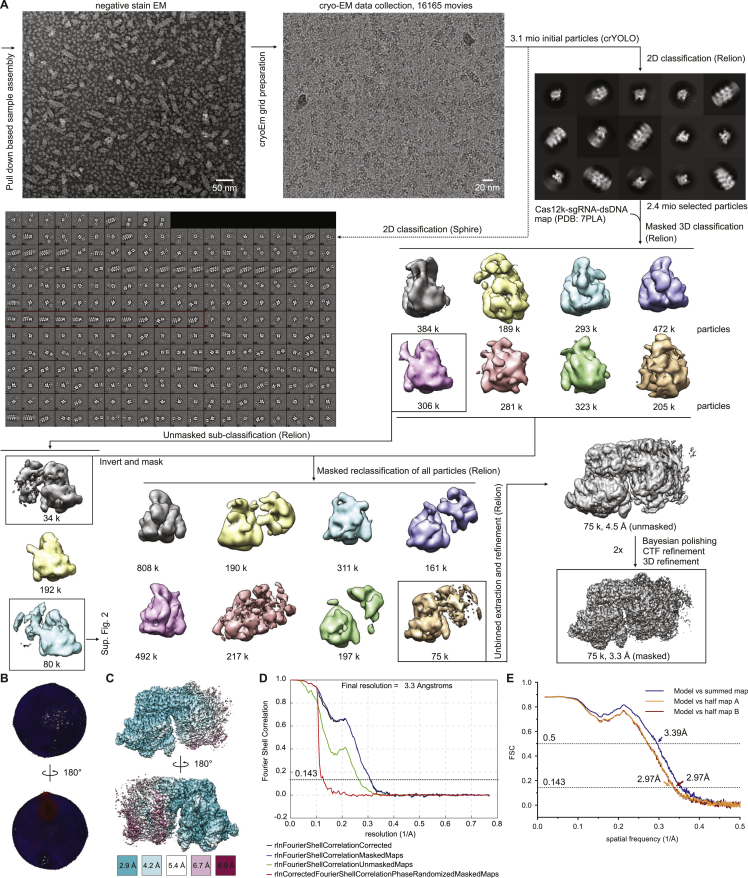

(A) Cryo-EM image processing workflow for the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex. Representative negative-stain EM and cryo-EM micrographs are shown at 98,000x and 130,000x magnifications and with 50 and 20 nm scale bars, respectively. (B) Angular distribution plotted on the density map. (C) Final cryo-EM density map colored according to local resolution. (D) Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) of the reconstruction from two independently refined half-maps. The gold-standard cut-off (FSC = 0.143) is marked with a black dotted line. (E) Validation of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex atomic model.

The resulting atomic model of the complex is comprised of Cas12k and the sgRNA bound to the target site in the DNA together with a single TniQ molecule and an emerging right-handed TnsC filament assembled on the PAM-distal region of the target DNA. Cas12k binds the DNA in a guide-RNA- and PAM-dependent manner, as observed previously in the structure of the Cas12k-sgRNA-target-DNA complex.15,16 TniQ makes direct contacts with the tracrRNA part of the sgRNA and two TnsC protomers, thereby bridging Cas12k and the TnsC filament without directly interacting with Cas12k. The TnsC filament is assembled with the TnsC C-terminal domains pointing away from Cas12k. The reconstruction contains additional proteinaceous density, which we were able to assign to a single copy of the E. coli ribosomal S15 protein that was serendipitously co-purified as a contaminant with TniQ, as verified by mass-spectrometric analysis of the TniQ sample used for cryo-EM analysis (Table S2). Notably, S15 makes extensive contacts with both Cas12k and the tracrRNA part of the sgRNA (Figures 1C and 1D).

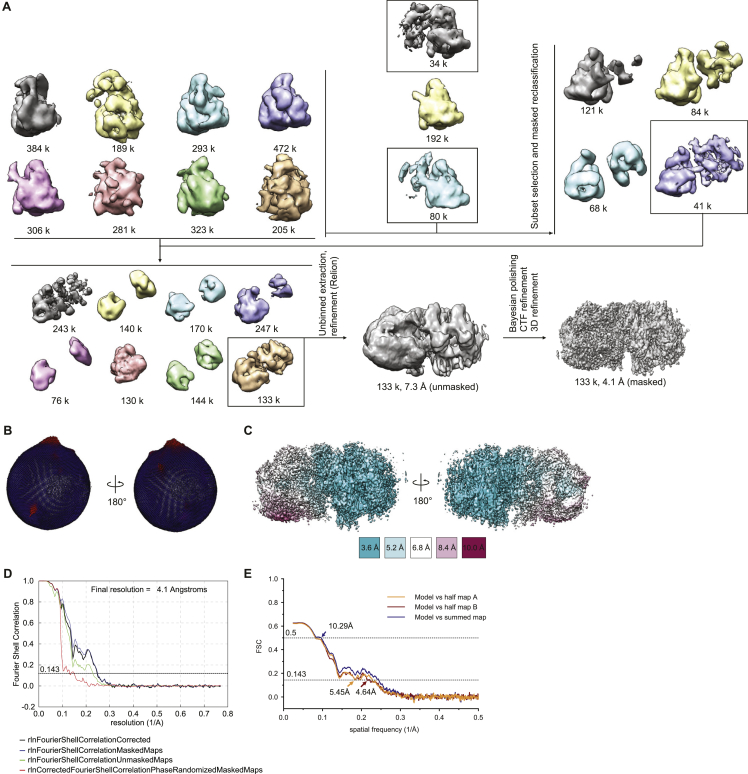

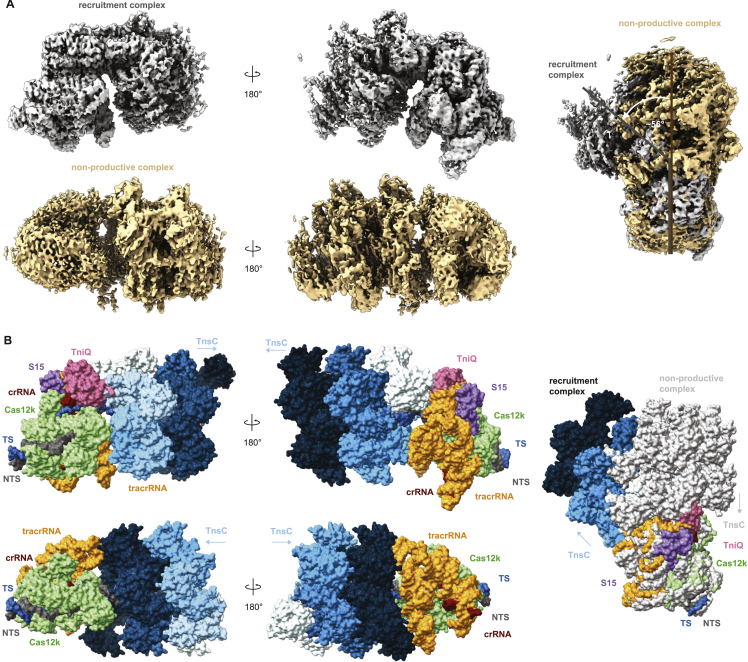

Within the same cryo-EM sample, we were additionally able to identify a separate population of particles comprised of Cas12k bound to DNA together with TnsC oligomers assembled in the reverse orientation, i.e., with TnsC C-terminal domains pointing toward Cas12k, obtaining a reconstruction at a resolution of 4.1 Å (Figure S2; Table S1). Notably, the R-loop in this assembly remained in its incomplete form, and both TniQ and S15 are absent (Figure S3). Furthermore, there are no direct intermolecular contacts between Cas12k-sgRNA and the proximal end of the TnsC filament, suggesting that this molecular assembly represents a non-productive complex in which TnsC spontaneously oligomerized on the target DNA in a Cas12k-independent manner.

Figure S2.

Cryo-EM data processing workflow for the Cas12k-TnsC non-productive complex, related to Figure S3 and STAR Methods

(A) Continued details of the cryo-EM image processing workflow from Figure S1. (B) Angular distribution plotted on the resulting density map. (C) Final electron density map colored according to the local resolution. (D) Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) of the reconstruction from two independently refined half-maps. (E) Validation of the Cas12k-TnsC non-productive complex atomic model.

Figure S3.

Structural comparison of Cas12k-transposon recruitment and Cas12k-TnsC non-productive complexes, related to Figures 1, S1, and S2

(A) Cryo-EM density maps of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex (top) and the Cas12k-TnsC non-productive complex (bottom). Side views and structural superpositions are shown. Proteins are shown in surface representation. The DNA in the transposon recruitment complex is bent by ∼56° relative to the non-productive complex. (B) Atomic models, shown in surface representation, of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex (top) and the Cas12k-TnsC non-productive complex (bottom).

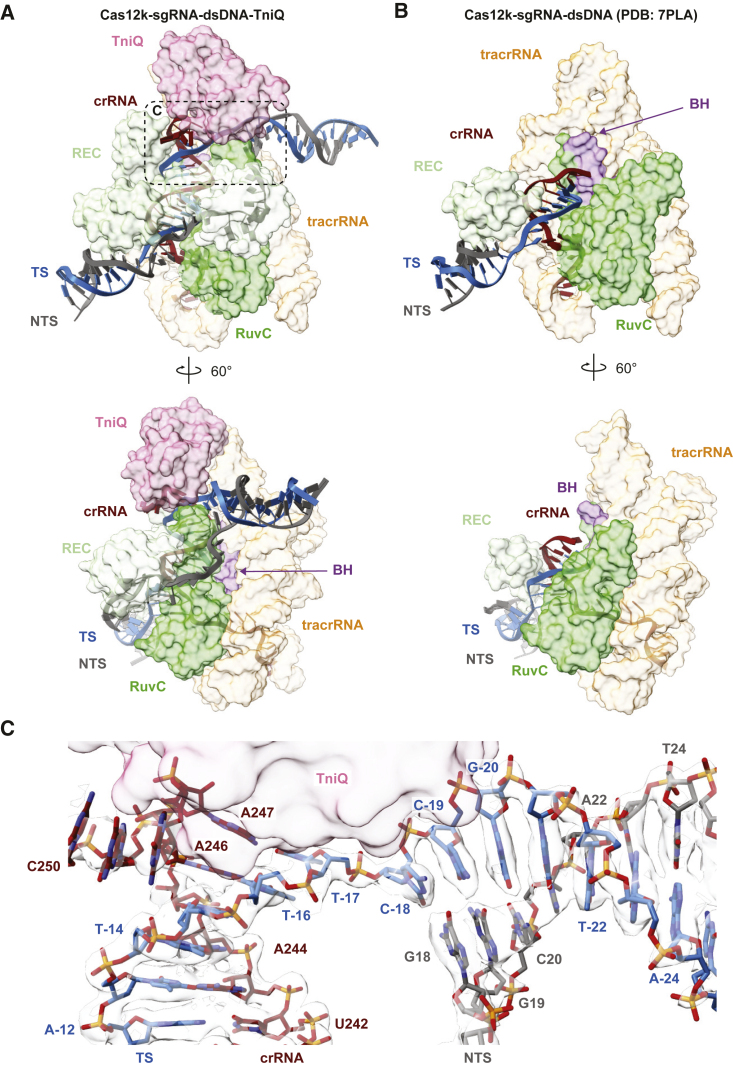

R-loop completion occurs upon TniQ and TnsC binding

Previous structures of the Cas12k-guide-RNA-target-DNA complexes revealed incomplete hybridization of the crRNA sequence and the TS DNA, resulting in a nine-bp heteroduplex.15,16 In the structure of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex, the crRNA and the target DNA form a complete R-loop structure comprising a 17-bp heteroduplex, beyond which the TS and the non-target strand (NTS) rehybridize. crRNA-TS-DNA hybridization beyond the 17th base pair is prevented by TniQ binding to the completed R-loop, leaving seven unpaired nucleotides at the 3′ end of the crRNA spacer sequence. This observation is consistent with previous studies showing that 3′-terminally truncated crRNAs comprised of 17 nucleotide spacer segments supported type V CAST activity in vivo.10 Overall, the DNA adopts a bent conformation, with the PAM-distal DNA exiting Cas12k at a 122° angle relative to the PAM-proximal DNA duplex (Figure 2A). The backbone of the displaced NTS can be completely traced as it wraps around Cas12k, passing through a gap between the recognition (REC) lobe and the RuvC domain (Figure 2A). Completion of the R-loop occurs by TniQ interacting with the PAM-distal end of the sgRNA-TS heteroduplex and is enabled by conformational rearrangements within Cas12k (Figures 2A–2C). The Cas12k bridge helix, which precludes full R-loop formation in the structure of the Cas12k-sgRNA-target-DNA complex,15,16 is repositioned to expose the binding cleft for the PAM-distal part of the sgRNA-TS-DNA heteroduplex (Figures S4A and S4B). This is accompanied by structural ordering of the REC lobe motifs, whereby the REC1 domain (residues 12–239Cas12k) interacts with the unpaired NTS while the REC2 domain (residues 240–278Cas12k) contacts the extended crRNA-TS heteroduplex. Further conformational rearrangements occur in the RuvC domain, where an alpha-helical hairpin (residues 548–590Cas12k) is repositioned to contact the NTS and the tracrRNA scaffold (Figures S4B and S4C).

Figure 2.

R-loop completion upon complex assembly

(A) Detailed views of the R-loop structure in the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex, comprised of the crRNA portion of the single guide RNA (red cartoon backbone), the TS (blue cartoon backbone), and the NTS (dark gray cartoon backbone). Only the REC lobe, the RuvC domain, and the bridging helix (BH) of Cas12k are shown for clarity.

(B) Detailed views of the R-loop structure in the Cas12k-sgRNA-target-DNA complex (PDB: 7PLA15).

(C) Zoomed-in view of the PAM-distal end of the R-loop in the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex. Density corresponding to nucleic acids is shown (contour level of 7.7 σ). TniQ is depicted as surface representation.

See also Figure S4.

Figure S4.

Structural rearrangements in Cas12k and guide RNA upon R-loop completion, related to Figure 2

(A) Structural models of the Cas12k-sgRNA-target DNA complex (PDB: 7PLA,15 top) and the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex bottom), shown in the same orientation. Domain architecture of Cas12k is shown below each model. REC, recognition lobe. WED, wedge domain. PI, PAM interacting domain. BH, bridging helix. TS, target DNA strand; NTS, non-target DNA strand. (B) Structural superpositions of the RuvC and BH domains in the Cas12k-sgRNA-target DNA and Cas12k-transposon recruitment complexes. (C) Structural superposition of the tracrRNA part of the sgRNA in the Cas12k-sgRNA-target DNA (gray) and the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex (orange).

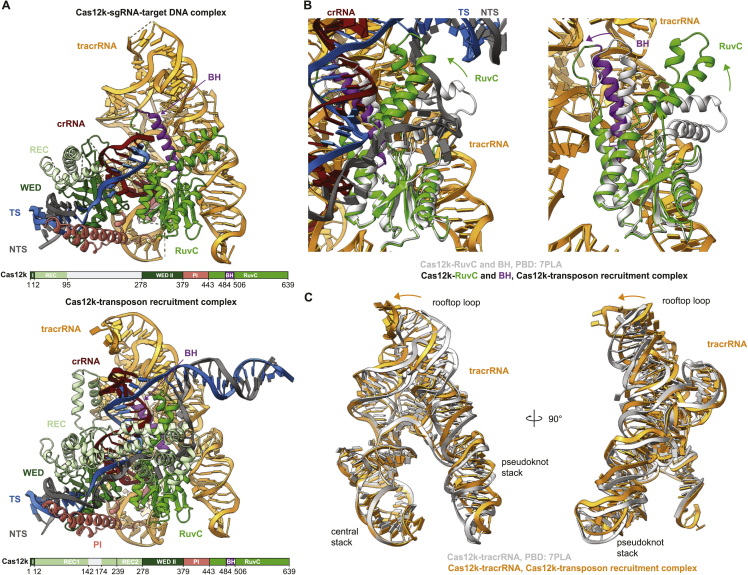

TniQ recognizes tracrRNA and R-loop

In the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex, TniQ is confined by the tracrRNA rooftop loop (nucleotides 167–171tracrRNA) and the PAM-distal end of the crRNA-TS-DNA heteroduplex on one side and the TnsC filament on the other (Figure 3A). The rooftop loop, which is structurally disordered in the Cas12k-sgRNA-target-DNA complex,15,16 now assumes a well-defined pentaloop conformation whose shape is read out by hydrogen bonding contacts with side chains of Gln93TniQ, Arg98TniQ, Lys128TniQ, Lys132TniQ, and Gln137TniQ in addition to a π-π stacking interaction between rG169tracrRNA and Trp120TniQ (Figure 3B). To validate the observed interactions, we tested the effect of TniQ and tracrRNA mutations on the transposition activity of ShCAST in vivo using quantitative droplet-digital PCR analysis. Mutations of a subset of interacting residues in TniQ substantially reduced transposition activity. In turn, substitution of the rooftop pentaloop with a 5′-GAAA-3′ tetraloop or adenine substitution of U168tracrRNA led to complete loss of transposition, while individual substitutions of other pentaloop nucleotides substantially reduced transposition activity (Figure 3C). TniQ further interacts with the PAM-distal end of the R-loop. Here, the terminal base pair of the crRNA-TS heteroduplex is contacted by Asn59TniQ at the minor groove edge and capped by an π-π stacking interaction with His57TniQ, which is in turn hydrogen bonded to His94TniQ (Figure 3D). Mutations of TniQ residues directly interacting with the crRNA-TS-DNA duplex substantially reduced transposition activity in vivo (Figure 3E). Together with our structural observations, these results confirm the critical role of the tracrRNA rooftop loop as a TniQ interaction site as well as its significance for TniQ-mediated TnsC recruitment to support transposition activity of type V CASTs. Furthermore, the observed interactions of TniQ with the PAM-distal end of the guide RNA-TS-DNA heteroduplex suggest that R-loop completion is facilitated by TniQ recruitment (Figures 2C and 3D).

Figure 3.

TniQ recognizes tracrRNA and completed R-loop

(A) Overview of TniQ in the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex, depicting interfaces with the tracrRNA (orange) and the RNA:DNA heteroduplex formed by the crRNA (red) and the TS (blue). NTS is colored in dark gray. The N and C termini of TniQ are indicated.

(B) Close-up view of key tracrRNA-interacting residues of TniQ.

(C) Site-specific transposition activity in E. coli of ShCAST systems containing structure-based mutations in the tracrRNA or the tracrRNA-interacting interface in TniQ, as determined by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent replicates).

(D) Detailed view of R-loop recognition by TniQ.

(E) Site-specific transposition activity in E. coli of ShCAST systems containing structure-based mutations in the R-loop recognition interface of TniQ. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent replicates).

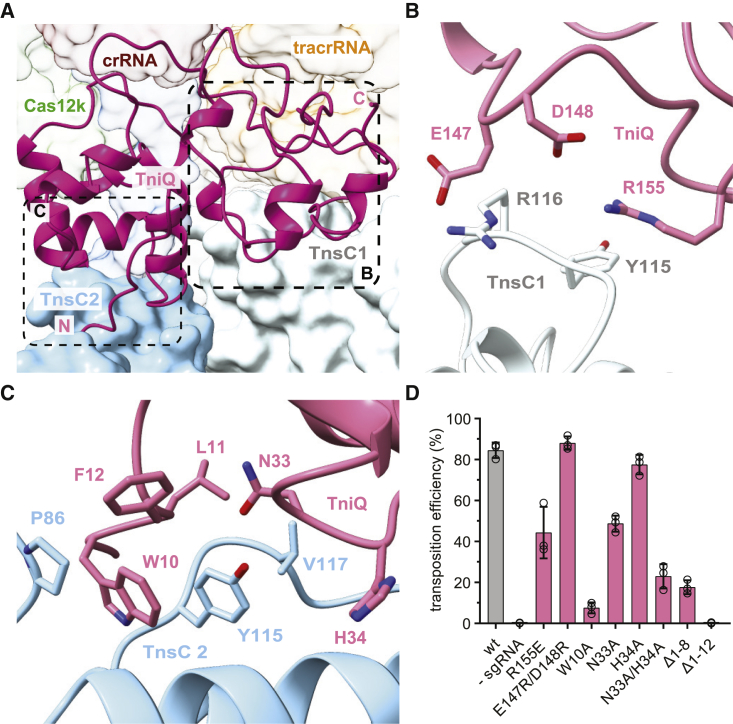

TniQ bridges tracrRNA and TnsC filament

Positioned by interactions with the tracrRNA rooftop loop and the R-loop, the single TniQ molecule in the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex straddles two TnsC protomers at the Cas12k-proximal end of the TnsC filament (Figure 4A). The C-terminal Zn-finger domain (ZnF2) of TniQ contacts the terminal TnsC protomer (TnsC1), mostly via electrostatic interactions (Figure 4B). In turn, the N-terminal helix-turn-helix (HTH) domain of TniQ interacts extensively with the next TnsC protomer (TnsC2) in the filament. Notably, the N-terminal tail of TniQ inserts into a cleft in the α/β AAA+ domain of TnsC2, with the aromatic side chain of Trp10TniQ sandwiched by hydrophobic interactions with Tyr115TnsC2 and Pro86TnsC2 (Figure 4C). Glutamate substitution of TnsC1-interacting residue Arg155TniQ reduced in vivo transposition by ∼50%, suggesting that the interaction of TniQ with TnsC1 contributes to transposon recruitment. In contrast, N-terminal truncation of TniQ to remove residues 1–12 resulted in complete loss of transposition, while alanine substitution of Trp10TniQ resulted in >90% reduction (Figure 4D). Together, these results validate the critical role of the TniQ N-terminal tail for the interaction with the TnsC filament and suggest its involvement in filament nucleation.

Figure 4.

TniQ contacts TnsC filament end

(A) Overview of the interactions between TniQ (cartoon representation) and two TnsC protomers (TnsC1 and TnsC2, surface representation) at the Cas12k-proximal filament end. The N and C termini of TniQ are indicated.

(B) Close-up view of key interactions between TniQ and TnsC1.

(C) Close-up view of key interactions between TniQ and TnsC2.

(D) Site-specific transposition activity in E. coli of ShCAST systems containing mutations in the TnsC-binding interface of TniQ, as determined by ddPCR analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent replicates).

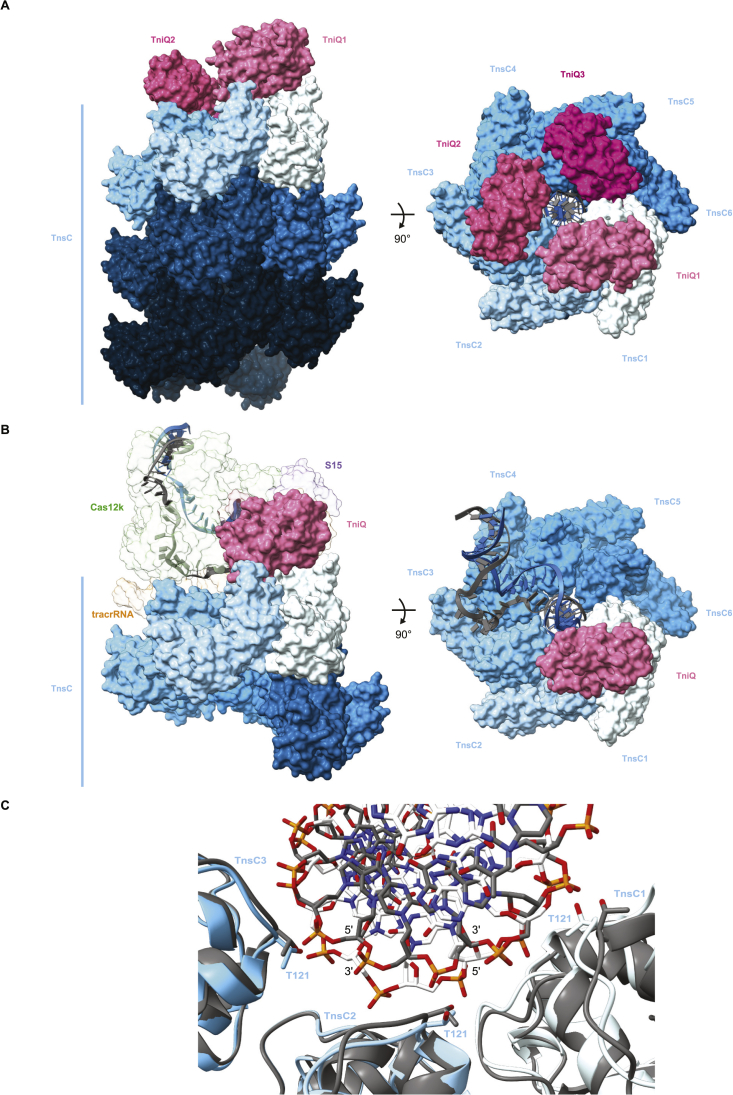

Previous studies have shown that in the absence of Cas12k and guide RNA, TniQ caps TnsC filaments assembled on dsDNA,18 thereby restricting TnsC polymerization in vitro.15,18 We extended these findings by docking a previously determined crystal structure of TniQ15 into a 3.5-Å-resolution cryo-EM reconstruction of a TniQ-capped TnsC filament obtained by single-particle analysis (Figure S5; Table S1). Altogether, three copies of TniQ assemble at the end of the TnsC filament, each bridging a TnsC dimer within the terminal hexameric helical turn of the filament (Figure S6A). Overall, the interactions between TnsC dimers and TniQ are highly similar with those observed in the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex (Figures S6A and S6B). However, the binding of Cas12k-gRNA to a TnsC filament fully capped by TniQ would not be compatible due to steric clashes with two of the three TniQ copies (Figure S6B).

Figure S5.

Cryo-EM analysis of TniQ-capped TnsC filament, related to Figures 5 and S6 and STAR Methods

(A) Cryo-EM image processing workflow for the TniQ-capped TnsC filament complex. (B) Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) of TnsC-DNA-TniQ reconstruction from two independently refined half-maps. The gold-standard cut-off (FSC = 0.143) is marked with a blue line. (C) Final electron density map colored according to the local resolution. (D) Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) of the reconstruction from two independently refined half-maps.

Figure S6.

Structural comparisons of TniQ-capped TnsC filament and Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex, related to Figures 5 and S5 and Table S1

(A) Side and top views of the TniQ-capped TnsC filament. Proteins are shown in surface representation. (B) Side and top views of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex, with TniQ shown in the same orientation as TniQ1 in (A). In the top view, Cas12k, S15 and tracrRNA are omitted to visualize the contacts between TniQ and TnsC. (C) Structural overlay of three consecutive TnsC protomers (TnsC1-TnsC3) in the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex (colored protomers, white DNA) and in the TniQ-capped TnsC filament (gray protomers and DNA) and the associated DNA (shown in stick representation).

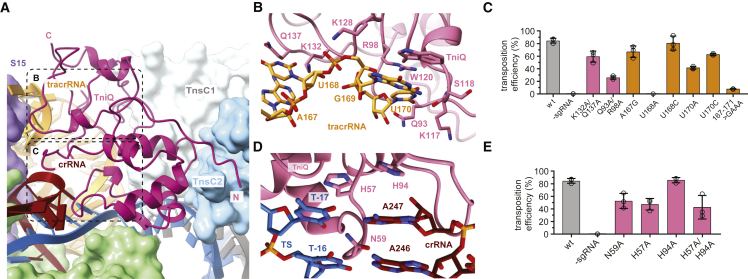

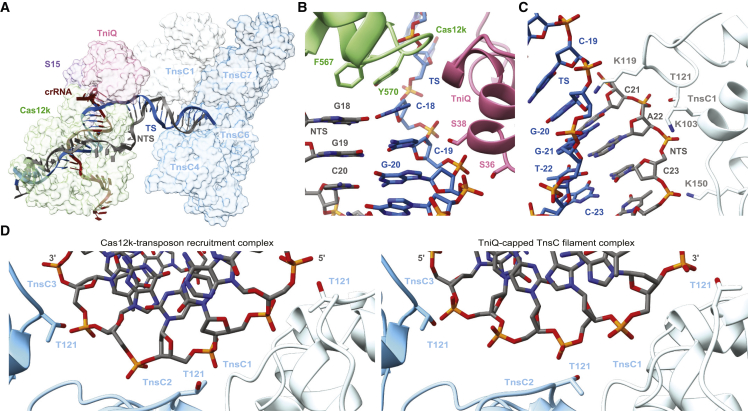

TnsC assembles at distal end of TniQ-bound R-loop

At the PAM-distal end of the R-loop within the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex, the TS bends away from the crRNA-TS heteroduplex and exits through a narrow channel formed by the Cas12k RuvC domain and TniQ to immediately rehybridize with the NTS (Figures 2C and 5A). The first bp of the reformed TS-NTS duplex (position 18) stacks against the aromatic side chains of Tyr570Cas12k and Phe567Cas12k, while TS nucleotides at positions 19 and 20 make backbone interactions with TniQ by hydrogen bonding with Ser36TniQ and Ser38TniQ (Figure 5B). This positions the TS-NTS duplex for entry into the TnsC helical filament. The terminal TnsC protomer (TnsC1) interacts with NTS nucleotides at positions 22 and 23 via Thr121TnsC1, Lys103TnsC1, and Lys150TnsC1 (Figure 5C). The next TnsC protomer (TnsC2) interacts with the minor groove of the duplex, contacting both TS and NTS, while TnsC3 and subsequent protomers interact mostly with the NTS. Overall, the interactions of the TnsC filament with the DNA involve the same residues (Thr121TnsC, Lys103TnsC, and Lys150TnsC) as previously observed in the structures of dsDNA-bound TnsC filaments and validated by mutational analysis in vivo.15,18 Similarly, the PAM-distal DNA duplex is distorted from the canonical B-form geometry to match the helical symmetry of the TnsC filament. Crucially, the TnsC filament in the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex tracks the DNA strand with the opposed polarity, i.e., the NTS, as compared with the TnsC-only filament (Figures 5D and S6C).

Figure 5.

TnsC assembly on PAM-distal end of R-loop DNA

(A) Overview of guide-target R-loop structure within the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex. TS (blue) and NTS (dark gray) are shown in cartoon format. Only the crRNA portion of the single-guide RNA (red) is shown. Proteins are shown in surface representation. Residues 132–254 of Cas12k and the TnsC2 and TnsC3 protomers are omitted from view for clarity.

(B) Zoomed-in view of target DNA-binding residues of TniQ.

(C) Zoomed-in view of the DNA-binding residues in the TnsC1 protomer.

(D) Comparison of DNA binding modes of consecutive TnsC protomers (TnsC1–TnsC3) in the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex (left) and in the TniQ-capped TnsC filament (right).

See also Figure S5.

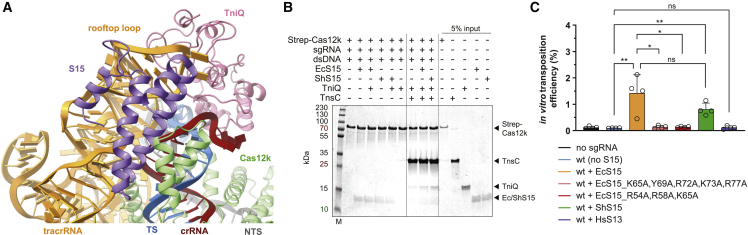

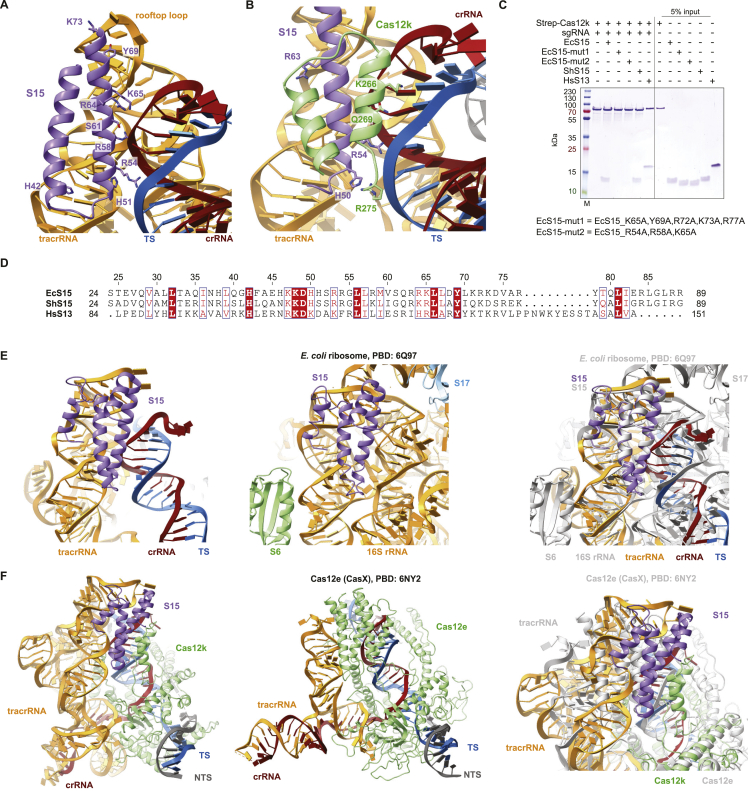

Ribosomal S15 protein supports Cas12k-transposon complex assembly

The E. coli ribosomal protein S15 (EcS15) captured in the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex is wedged between the Cas12k REC2 domain and the tracrRNA connector duplex and contacts the ribose-phosphate backbone of the crRNA in the PAM-distal part of the crRNA-TS-DNA heteroduplex (Figures 6A and S7A–S7D). As within the small ribosomal subunit, EcS15 adopts a four-helix bundle fold and interacts with the tracrRNA and the heteroduplex in a manner that mimics its interactions with 16S rRNA (Figure S7E). The combined fold of EcS15 and the Cas12k REC2 domain is highly similar to the helical fold of the REC2 (Helical II) domain in the distantly related Cas12e (CasX) nuclease31 (Figure S7F). EcS15 makes extensive shape-complementary interactions with the tracrRNA rooftop loop via electrostatic interactions mediated by Arg72EcS15, Lys73EcS15, and Arg77EcS15 and π-π stacking between Tyr69EcS15 and rA171tracrRNA, suggesting that it stabilizes the tracrRNA rooftop loop in a conformation that supports TniQ recruitment. We verified that recombinantly produced EcS15 and S. hofmanni S15 (ShS15) proteins bound the Cas12k-sgRNA binary complex in a pull-down experiment (Figure S7C). Notably, EcS15 and ShS15 proteins share 45% sequence identity, and the residues involved in contacting the tracrRNA and Cas12k are nearly invariant between the orthologs (Figure S7D). This suggests that a host-encoded 30S ribosomal S15 protein might act as a bona fide component of the transposon recruitment complex in type V CAST systems to promote the interactions of Cas12k-bound tracrRNA with TniQ and thus enable TnsC recruitment. To test this hypothesis, we carried out pull-down experiments to observe the co-precipitation of TniQ and TnsC with immobilized StrepII-tagged Cas12k-sgRNA-target-DNA complex in the presence of purified EcS15 or ShS15 proteins (Figure 6B). For these experiments, TniQ was re-purified according to a stringent protocol that eliminated EcS15 contamination (Table S2). Both EcS15 and ShS15 were efficiently co-precipitated by the Cas12k-sgRNA-DNA complex. TniQ co-precipitation was markedly enhanced in the presence of EcS15 or ShS15 and TnsC, suggesting that S15 proteins facilitate the cooperative assembly of TniQ with TnsC and Cas12k-sgRNA on target DNA. To further test the effect of EcS15 and ShS15 proteins on Cas12k-dependent transposition, we performed in vitro transposition assays using donor and target plasmids, in vitro transcribed sgRNA, and purified recombinant proteins (Cas12k, TniQ, TnsC, TnsB, and S15), monitoring on-target transposition efficiency by droplet-digital PCR analysis. In the absence of S15 proteins, only very low levels of sgRNA-dependent transposition could be detected. Transposition efficiency was significantly enhanced by the addition of EcS15 or ShS15 (Figure 6C). EcS15 proteins containing structure-based mutations of guide RNA-interacting EcS15 residues that resulted in the loss of binding to the Cas12k-sgRNA complex (Figure S7C) failed to enhance transposition activity in vitro (Figure 6C). These results indicate that S15 specifically promotes transposition by facilitating the assembly of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex, suggesting that it may function as an integral part of the type V CAST machinery. The 40S ribosomal protein S13 (RPS13) is the eukaryotic ortholog of the bacterial S15 protein32 (Figure S7D). We thus tested whether human RPS13 (HsRPS13) was able to promote RNA-guided transposition similarly to S15. Although HsRPS13 co-precipitated with sgRNA-bound Cas12k (Figure S7C), it was unable to support RNA-guided transposition of ShCAST above background levels in vitro (Figure 6C), indicating that it cannot functionally substitute for bacterial S15 in the context of type V CAST systems.

Figure 6.

S15 promotes Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex assembly and transposition activity

(A) Zoomed-in view of S15 binding in the Cas12k-recruitment complex.

(B) Co-precipitation of TnsC and TniQ in presence or absence of S. hofmanni S15 (ShS15) or E. coli S15 (EcS15) by immobilized Cas12k-sgRNA-target DNA complex.

(C) In vitro transposition activity of purified ShCAST components in the absence or presence of EcS15 (wild-type or mutant), ShS15, and Homo sapiens RPS13 (HsS13) proteins, as determined by ddPCR analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4 independent replicates). Statistical analysis was conducted using unpaired two-tailed t-tests. P-values: ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ns, not significant.

See also Figure S7.

Figure S7.

Interactions and conservation of the ribosomal protein S15, related to Figure 6

(A) Zoomed-in view of E. coli S15 interactions with the tracrRNA and crRNA:TS-DNA duplex in the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex. (B) Zoomed-in view of S15 contacts with the Cas12k REC2 domain. (C) Co-precipitation of E. coli S15 (EcS15) wild-type and mutant, S. hofmanni S15 (ShS15) and Homo sapiens RPS13 (HsS13) proteins by immobilized Cas12k-sgRNA complex. (D) Sequence alignment of the ribosomal proteins EcS15, ShS15 and HsS13. (E) Zoomed-in views of EcS15 interactions with tracrRNA in the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex (left), 16S rRNA in the E. coli ribosome (middle; PDB: 6Q9764), and a superposition of both focused on S15 (right). (F) Structural models of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex (left), Cas12e-sgRNA-target DNA complex (middle; PDB: 6NY231), and their superposition focused on S15 (right).

Discussion

The molecular function of CASTs relies on the concerted activities of the RNA-guided CRISPR-Cas effector and transposase modules. In type V CASTs, this is thought to involve interactions of the transposon regulator AAA+ ATPase TnsC with the RNA-guided pseudonuclease Cas12k at the target site, but the mechanistic details have remained elusive thus far. Our structural analysis of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex shows that the tracrRNA component of the Cas12k guide RNA and TniQ play key roles in the process by bridging RNA-bound Cas12k and the ATP-dependent TnsC filament assembled on the target DNA. Our findings provide evidence that the formation of a complete R-loop structure within Cas12k occurs upon TniQ and TnsC recruitment and thus serves as a structural checkpoint for transposon recruitment complex assembly. This is likely to have mechanistic parallels in type I CAST systems, as previous structural analysis of the type I-F Cascade-TniQ complex showed that the complex forms an incomplete R-loop upon target DNA binding, suggesting that R-loop completion is dependent on the presence of further transposon components, possibly TnsC.25,26,27

TniQ alone does not form a stable complex with the ternary Cas12k-sgRNA-dsDNA complex but was previously shown to cap TnsC filaments and restrict their polymerization on free linear dsDNA in vitro.15,18 Based on these observations, we previously proposed a mechanistic model whereby the TnsC filament is nucleated by Cas12k, while TniQ caps the filament at the Cas12k-distal end, thereby restricting its polymerization to the vicinity of Cas12k.15 An alternative model posited that TnsC polymerization initiates randomly on DNA and is selectively stabilized by interactions with target-site-bound Cas12k and TniQ.18 Remarkably, the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex structure reveals that a single TniQ molecule bridges the tracrRNA and two TnsC protomers at the Cas12k-proximal end of the TnsC filament. Based on these findings and their functional validation, we thus propose a revised “direct nucleation” model in which TniQ neither caps the Cas12k-distal end of the TnsC filament nor acts in conjunction with Cas12k to stabilize filaments randomly nucleated on DNA (Figure 7). Instead, the cooperative assembly of Cas12k, guide RNA, S15, and TniQ, enabled by full hybridization of a 17-bp crRNA-TS heteroduplex and R-loop completion, generates a TnsC interaction site to directly nucleate filament formation starting from the PAM-distal end of Cas12k. Importantly, the polarity of the tracked DNA strand in the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex is the opposite of that observed in standalone TnsC filaments assembled on free double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). Based on structural observations of head-to-head filament collisions, TnsC was previously proposed to polymerize in a head-to-tail manner in the 5′-3′ direction of the tracked DNA strand.18 Although our model implies the opposite directionality of TnsC polymerization, the TnsC protomers nevertheless track the NTS DNA in the 5′-3′ direction. The opposite directionality of TnsC polymerization is further supported by the direct observation of the Cas12k-TnsC non-productive complex, in which the TnsC filament likely spontaneously polymerized at the free (i.e., Cas12k-distal) DNA end until sterically hindered by the DNA-bound Cas12k-sgRNA complex. Notably, the R-loop in the non-productive complex remains incomplete, and both TniQ and S15 are absent. Thus, a parsimonious interpretation of our structural and functional data points to localized TnsC filament nucleation at the target site defined by crRNA-guided Cas12k, although we cannot presently rule out an alternative mechanism based on randomly initiated TnsC polymerization followed by specific capture and stabilization by DNA-bound Cas12k-TniQ.

Figure 7.

Mechanism of RNA-guided assembly in type V CASTs

Mechanistic model for the recruitment of the transposition machinery by the RNA-guided Cas12k complex in type V-K CASTs. Cas12k in association with a crRNA-tracrRNA dual guide RNA initially binds target DNA to form a partial R-loop structure. Full R-loop formation occurs upon recruitment of S15, TniQ, and TnsC. TniQ recognizes specific regions of the tracrRNA and primes polymerization of a TnsC filament by bridging the first two TnsC protomers. The ribosomal protein S15 facilitates productive complex assembly by interacting with tracrRNA and Cas12k. The resulting TnsC filament provides a recruitment platform for TnsB, which triggers TnsC depolymerization to expose the insertion site and catalyzes transposon DNA insertion.

Overall, the transposon recruitment mechanism of type V CASTs is thus likely to be analogous to that of type I CASTs in that they both rely on TniQ-dependent assembly of TnsC. However, in type I systems TniQ is an integral component of the Cascade complex.25,26,33 In type V, TniQ does not form a stable complex on its own with target-DNA-bound Cas12k-sgRNA and is instead recruited cooperatively together with TnsC (and S15, as discussed below) (Figure 6B).15 It is nevertheless possible that TniQ may also interact with TnsC in a Cas12k-independent manner or with other biological R-loop structures, which might lead to off-target transposon recruitment and thus explain why type V CRISPR-transposon systems appear to be less specific than type I systems and more prone to off-target transposon insertion. 7,20 Altogether, the structure of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex establishes a paradigm for CRISPR-transposon systems and other Tn7-like transposons that rely on the interaction between a sequence-specific DNA binding protein and an oligomeric AAA+ ATPase for site-specific transposon insertion. 34,35,36,

In view of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex structure, the previously characterized distance between the Cas12k target site and the transposon insertion site (60–66 bp downstream of the PAM for ShCAST) implies that formation of four complete helical turns of the TnsC filament is likely required for initial TnsB recruitment. As TnsC assembles into hexameric rings on dsDNA in the presence of ADP,18 it was previously suggested that upon TnsB recruitment, TnsB-mediated disassembly of the TnsC filament would result in a hexameric TnsC ring remaining bound to the Cas12k-TniQ R-loop complex, the physical footprint of which would define the insertion site.18 However, modeling the structure of this assembly by superposing an ADP-bound TnsC hexamer onto the Cas12k-TnsC transposon recruitment complex suggests that the insertion site would be located approximately 28–34 bp from the edge of the TnsC hexameric ring. The discrepancy might in part be due to the large physical footprint of the TnsB-transposon complex, as suggested by recent structural studies of the E. coli Tn7 TnsB37 and the type V CRISPR-associated ShTnsB21 bound to transposon-end DNA sequences. A recently reported structural analysis of the ShCAST transposon integration holocomplex reveals that TnsB recruitment results in a two-turn ATP-bound TnsC filament instead of a hexameric ADP-bound TnsC ring, providing a mechanistic rationale for insertion site definition.38

Finally, our structural and functional data indicate that the bacterial 30S ribosomal protein S15 is an integral component of the type V CRISPR-transposon system, as it allosterically stimulates the assembly of TniQ and TnsC in the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex, thereby enhancing RNA-guided transposition in vitro (Figure 6). Although ribosomal proteins are known to participate in several functions outside their canonical roles in ribosome assembly and function both in bacteria39 and in eukaryotes,40 the involvement of ribosomal components or other host-encoded “housekeeping” factors in the targeting activity of a CRISPR effector complex is, to the best of our knowledge, unprecedented. Of note, ribosomal proteins have been functionally implicated in the canonical E. coli Tn7 transposon machinery, where the ribosomal protein L29 was found to interact with the TnsD protein-attachment site (attTn7) DNA complex and stimulate Tn7 transposition by a yet uncharacterized mechanism.41 However, the interaction between L29 and the TnsD-attTn7 complex is likely mediated by protein-protein and/or protein-DNA interactions, in contrast to the specific intermolecular contacts established by S15 with the R-loop and the distinct tracrRNA structure of type V CASTs. The involvement of S15 is thus likely a unique and specific feature of type V CRISPR-associated transposons and is not conserved in type I systems due to the lack of a tracrRNA. Last but not least, our work indicates that the human 40S ribosomal protein RPS13, the ortholog of bacterial S15, is unable to enhance RNA-guided transposition in vitro. These findings have important implications for the genome engineering application of CASTs. As type V CAST systems have not yet been demonstrated to support RNA-guided transposition in eukaryotic cells, it is conceivable that this is in part because our description of this systems has hitherto been incomplete. Our data hint that co-delivery of the S15 protein might be necessary for the reconstitution of robust RNA-guided transposition to enable technological exploitation of type V CASTs. In sum, this work sheds light on a fundamental step in the biological mechanism of CAST systems and lays the mechanistic foundation for their development as next-generation genome engineering technologies.

Limitations of the study

In this study, we provide structural snapshots of a Cas12k-transposon assembly comprised of the RNA-guided pseudonuclease Cas12k, the transposon proteins TnsC and TniQ, and the ribosomal protein S15 and propose a cooperative binding mode to target DNA and promote transposon insertion. However, the precise order of events underlying protein recruitment as well as the dynamics of TnsC filament assembly remains elusive and will require further biochemical and biophysical analysis to be fully understood. Our biochemical data and bacteria-based experiments suggest a functional role for S15 as a bona fide component of the type V CAST machinery, but the underlying mechanistic details remain to be determined. Notably, whether and to what extent the addition of S15 would support efficient reconstitution of RNA-guided transposition in heterologous hosts, including human cells, awaits experimental testing.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| dGTP solution | Roth | Cat#K037.1 |

| dCTP solution | Roth | Cat#K038.1 |

| dATP solution | Roth | Cat#K035.1 |

| dTTP solution | Roth | Cat#K036.1 |

| NAD | Roth | Cat#AE11.1 |

| T5 exonuclease | New England Biolabs | Cat#M0663S |

| Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | New England Biolabs | Cat#M0530L |

| Taq DNA Ligase | New England Biolabs | Cat#M0208L |

| T4 DNA Ligase | New England Biolabs | Cat#M0202S |

| 10x T4 DNA Ligase Reaction Buffer | New England Biolabs | Cat#B0202S |

| BamHI | New England Biolabs | Cat#R0136L |

| EcoRI-HF® | New England Biolabs | Cat#R3101 |

| Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside | AG Scientific | Cat#I-1312 |

| Carbenicillin disodium salt | Roth | Cat#6344.3 |

| Ampicillin sodium salt | Roth | Cat#K029.2 |

| Kanamycin sulfate | Roth | Cat#T832.4 |

| Chloramphenicol | Roth | Cat#3886.3 |

| Imidazole | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#56750 |

| Pepstatin A | Roth | Cat#2936.1 |

| AEBSF hydrochloride | Roth | Cat#2931.1 |

| Glycerol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#7000851 |

| Triton X-100 | Roth | Cat#3051.3 |

| BSA | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A2153 |

| Magnesium Acetate Tetrahydrate | Honeywell Fluka | Cat#15642270 |

| ddPCR Supermix for Probes (No dUTP) | Bio-Rad | Cat#1863024 |

| Droplet Generation Oil for Probes | Bio-Rad | Cat#1863005 |

| TEV protease | Martin Jinek Lab | N/A |

| Proteinase K | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#EO0491 |

| Trypsin Platinum, Mass Spectrometry Grade | Promega | Cat#VA9000 |

| Trichloroacetic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#T6399 |

| Calcium chloride | Roth | Cat#CN93.1 |

| Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C4706 |

| 2-Chloroacetamide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C0267 |

| TRIS hydrochloride | Roth | Cat#9090.3 |

| Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane | Biosolve | Cat#200923 |

| HEPES | Roth | Cat#HN78.1 |

| Magnesium chloride | Honeywell Fluka | Cat#63064 |

| Sodium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 71380 |

| Potassium chloride | Roth | Cat#6781.2 |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) 8,000 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#81268 |

| 1,4-Dithiothreitol | Roth | Cat#6908.4 |

| EDTA | Roth | Cat#8040.3 |

| D-(+)-Maltose monohydrate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#63418 |

| TWEEN 20 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#93773 |

| ATP | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#K054.3 |

| D-Desthiobiotin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#D1411 |

| 5 mL Ni-NTA Superflow Cartridges | Qiagen | Cat#30761 |

| 5 mL HiTrap Heparin HP | Cytiva | Cat#17-0407-03 |

| 5 mL MBPTrap HP | Cytiva | Cat#28-9187-80 |

| HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg | Cytiva | Cat#28989335 |

| Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL | Cytiva | Cat#GE28-9909-44 |

| HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg | Cytiva | Cat#GE28-9893-33 |

| Strep-Tactin Superflow resin | iba | Cat#2-1206-025 |

| ACQUITY UPLC M-Class Symmetry C18 Trap Column | Waters | Cat#186007496 |

| ACQUITY UPLC M-Class HSS T3 Column | Waters | Cat#186007474 |

| Amicon Ultra-15, PLTK Ultracel-PL Membran, 30 kDa | Merck Millipore | Cat#UFC903096 |

| Amicon Ultra-15, PLGC Ultracel-PL Membran, 10 kDa | Merck Millipore | Cat#UFC901096 |

| Amicon Ultra-0.5 Centrifugal Filter Unit | Merck Millipore | Cat#UFC500324 |

| Any kD Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Protein Gels | Bio-Rad | Cat#4569036 |

| Uranyl formate | Lucerna Chem | Cat#22450 |

| CF300-CU-50 | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat#CF300-Cu-50 |

| Quantifoil R 1.2/1.3, UT, 200 Mesh, Copper | Quantifoil Micro Tools | Cat#Q250CR1.3-2nm |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#K0503 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Atomic coordinates and maps of the Cas12k-sgRNA-target DNA | Querques, Schmitz et al., 202115 | PDB: 7PLA EMDB: EMD-13486 |

| Atomic coordinates and maps of the DNA- and AMPPNP- bound TnsC filament | Querques, Schmitz et al., 202115 | PDB:7PLH EMDB: EMD-13489 |

| Atomic coordinates and structure factors of the TniQ protein | Querques, Schmitz et al., 202115 | PDB:7OXD |

| Atomic coordinates and maps of the Cas12k-sgRNA-dsDNA-S15-TniQ-TnsC transposon recruitment complex | This paper | PDB: 8BD5 EMDB: EMD-15975 |

| Atomic coordinates and maps of the Cas12k-sgRNA-dsDNA-TnsC non-productive complex | This paper | PDB: 8BD6 EMDB: EMD-15976 |

| Atomic coordinates and maps of the TniQ-capped TnsC filament complex | This paper | PDB: 8BD4 EMDB: EMD-15974 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| E. coli BL21 Rosetta 2 (DE3) | Novagen | Cat#71400-3 |

| E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#C601003 |

| One Shot PIR1 Chemically Competent E. coli | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#C101010 |

| Mach1 T1 Phage-Resistant | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#C862003 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers, gBlocks and other oligonucleotides | This paper | See Table S3 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Scytonema hofmanni Cas12k (WP_029636312.1) | Querques, Schmitz et al., 202115 | See Table S3 |

| Scytonema hofmanni TnsC (WP_029636336.1) | Querques, Schmitz et al., 202115 | See Table S3 |

| Scytonema hofmanni TniQ (WP_029636334.1) | Querques, Schmitz et al., 202115 | See Table S3 |

| Scytonema hofmanni TnsB (WP_084763316.1) | Querques, Schmitz et al., 202115 | See Table S3 |

| Scytonema hofmanni S15 (WP_029633173.1) | This study | See Table S3 |

| Escherichia coli S15 (AP009048.1) | This study | See Table S3 |

| Homo sapiens RPS13 (P62277) | This study | See Table S3 |

| pET His6 TEV LIC cloning vector (1B) | Scott Gradia | Addgene #29653 |

| pET StrepII TEV LIC cloning vector (1R) | Scott Gradia | Addgene #29664 |

| pET His6 Sumo TEV LIC cloning vector (1S) | Scott Gradia | Addgene #29659 |

| pET His6 MBP Asn10 TEV LIC cloning vector (1C) | Scott Gradia | Addgene #29654 |

| pHelper_ShCAST_sgRNA | Strecker et al., 20197 | Addgene #127921 |

| pDonor_ShCAST_kanR | Strecker et al., 20197 | Addgene #127924 |

| pTarget_CAST | Strecker et al., 20197 | Addgene #127926 |

| pHelper-PSP1 | Querques, Schmitz et al., 2021 | See Table S3 |

| pUC19 plasmid | Martin Jinek Lab | Addgene #50005 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| EPU 2.9.0.1519REL | ThermoFisher Scientific | https://www.thermofisher.com/ch/en/home/electron-microscopy/products/software-em-3d-vis/epu-software.html#features |

| RELION 3.1.2 | Scheres, 201242 | https://relion.readthedocs.io/en/release-3.1/ |

| SPHIRE version 1.3 | Moriya et al., 201743 | https://sphire.mpg.de/wiki/doku.php |

| cryoSPARC 3.2.0 | Punjani et al., 201744 | https://cryosparc.com/ |

| MotionCor2 1.4.0 | Zheng et al., 201745 | https://emcore.ucsf.edu/ucsf-software |

| Gctf 1.06 | Zhang, 201646 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/research/locally-developed-software/zhang-software/ |

| crYOLO version 1.7.6 | Wagner et al., 201947 | https://cryolo.readthedocs.io/en/stable/ |

| Phenix 1.19.1–4122 | Adams et al., 201048 Afonine et al., 201849 Liebschner et al., 201950 |

http://www.phenix-online.org/ |

| UCSF Chimera 1.14 | Pettersen et al., 200451 | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/ |

| UCSF ChimeraX 1.2 | Pettersen et al., 202152 | https://www.rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimerax/ |

| GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1 | GraphPad Prism 9 for Windows, Version 9.3.1 | https://www.graphpad.com |

| MolProbity 4.5.1 | Chen et al., 2010; 53 Prisant et al., 202054 | http://molprobity.biochem.duke.edu |

| DALI | Holm, 202255 | http://ekhidna2.biocenter.helsinki.fi/dali/ |

| LibG | Brown et al., 201556 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/groups/murshudov/content/em_fitting/em_fitting.html |

| COOT 0.9.2-preEL in CCP-EM 1.5.0 | Emsley et al., 201057 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| QuantaSoft software 1.7.4.0917 | Bio-Rad | Cat#1864011 |

| Laboratory information management system (LIMS) | Turker et al., 201158 | ThermoFisher Scientific |

| MaxQuant 1.6.2.3 | Cox and Mann, 200859 | https://www.maxquant.org/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Martin Jinek (jinek@bioc.uzh.ch).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

Bacteria strains

For recombinant protein expression, E.coli bacteria were grown starting from a single colony in Luria Bertani medium (LB) at 37°C until OD600 reached 0.6, and further grown at 18°C with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) supplementation. For in vivo transposition assays, E. coli strains were plated on LB-agar plates supplemented with appropriate antibiotics and incubated at 37°C for 16 h.

Method details

Plasmid DNA constructs

The DNA sequences of S. hofmanni (Sh)Cas12k (WP_029636312.1), TnsC (WP_029636336.1), TniQ (WP_029636334.1), TnsB (WP_084763316.1), S15 (WP_029633173.1), E. coli (Ec)S15 (AP009048.1) and the Homo sapiens (Hs)RPS13 (P62277) proteins were codon optimized for heterologous expression in E. coli and synthesized by GeneArt (ThermoFisher Scientific) or IDT. The ShCas12k gene was inserted into the 1B (Addgene #29653) and 1R (Addgene #29664) plasmids using ligation-independent cloning (LIC),60 resulting in constructs carrying an N-terminal hexahistidine tag followed by a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site and an N-terminal hexahistidine-StrepII tag followed by a TEV cleavage site, respectively. The ShTnsC gene was inserted into the 1S (Addgene #29659) plasmid to produce a construct carrying an N-terminal hexahistidine and hexahistidine-SUMO tag followed by a TEV cleavage site and the ShTniQ gene was cloned into the 1C (Addgene #29654) vector generating a construct carrying a hexahistidine-maltose binding protein (6xHis-MBP) tag followed by a TEV cleavage site. The EcS15, mutant EcS15, ShS15 and HsRPS13 genes were inserted into the 1C vector. Point mutations were introduced by Gibson assembly61 or LIC cloning using gBlock gene fragments (IDT) as substrates or PCR templates, respectively. The pDonor (Addgene #127921), pHelper (Addgene #127924), and pTarget (Addgene #127926) plasmids7 used in droplet digital PCR experiments were sourced from Addgene. The PSP1-targeting spacer was cloned into pHelper by Gibson assembly, yielding pHelper-PSP1. Mutations in the sgRNA or in the sequence of the ShCas12k and ShTnsC genes were introduced into the pHelper plasmid by Gibson assembly. Plasmids were cloned and propagated in Mach I cells (ThermoFisher Scientific) with the exception of pHelper, which was grown in One Shot PIR1 cells (ThermoFisher Scientific). Plasmids were purified using the GeneJET plasmid miniprep kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) and verified by Sanger sequencing. All sequences of synthetic genes, primers, gBlocks and oligonucleotides used for cloning are provided in Table S3.

Protein expression and purification

For expression of ShCas12k constructs, hexahistidine-Strep II-tagged and hexahistidine-tagged ShCas12k proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) cells (ThermoFisher Scientific). Cell cultures were grown at 37°C shaking at 100 rpm until reaching an OD600 of 0.6 and protein expression was induced with 0.4 mM IPTG and continued for 16 h at 18 °C. Harvested cells were resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 1 μg mL−1 Pepstatin, 200 μg mL−1 AEBSF and lysed in a Maximator Cell homogenizer at 2,000 bar and 4°C. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 40,000 x g for 30 min at 4°C and applied to two 5 mL Ni-NTA cartridges (Qiagen) connected in tandem. The column was washed with 100 mL of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole before elution with 50 mL of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole. Elution fractions were pooled and dialyzed overnight against 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 250 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT in the presence of tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease. Dialyzed proteins were loaded onto a 5 mL HiTrap Heparin HP column (Cytiva) and eluted with a linear gradient of 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 1 M KCl. Elution fractions were pooled, concentrated using 30,000 molecular weight cut-off centrifugal filters (Merck Millipore) and further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 (16/600) column (Cytiva) in 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 250 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT yielding pure, monodisperse proteins. Purified proteins were concentrated to 10-15 mg mL−1, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further usage.

Expression of wild-type ShTnsC and ShTniQ was performed in E. coli BL21 Rosetta2 (DE3) cells (Novagen). Cells were grown in LB medium until reaching an OD600 of 0.6 and expression was induced by addition of 0.4 mM IPTG. Proteins were expressed at 18 °C for 16 h. For ShTnsC, the cells were harvested and resuspended in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 10 mM imidazole supplemented with 1 μg mL−1 Pepstatin and 200 μg mL−1 AEBSF. The cell suspension was lysed by ultrasonication and the lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 40,000 x g for 40 min. Cleared lysate was applied to a 5 mL Ni-NTA cartridge. The column was washed in two steps with lysis buffer supplemented with 25 and 100 mM imidazole, and bound proteins were eluted with 25 mL of same buffer supplemented with 500 mM imidazole pH 7.5. Eluted proteins were dialyzed overnight against 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT in the presence of TEV protease. The protein was further purified using a 5 mL HiTrap HP Heparin column and eluted with a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 700 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 1 mM DTT. The eluted fraction was concentrated and further purified by size exclusion chromatography using an Superdex 200 increase (10/300 GL) column (Cytiva) in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, yielding pure, monodisperse proteins. Purified ShTnsC was concentrated to 1-2 mg mL−1 using 30,000 kDa molecular weight cut-off centrifugal filters (Merck Millipore) and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

For ShTnsB, cells were harvested and resuspended in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 5 mM imidazole supplemented with 1 μg mL−1 Pepstatin and 200 μg mL−1 AEBSF and lysed by ultrasonication. Lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 40,000 x g for 40 min. The lysate was applied to a 5 mL Ni-NTA cartridge and the column was washed with lysis buffer supplemented with 25 mM imidazole. The protein was eluted with 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 200 mM imidazole. Eluted proteins were dialyzed overnight against 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT in the presence of TEV protease and subsequently purified using a 5 mL HiTrap HP Heparin column (Cytiva), eluting with a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 400 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT. The eluted fraction was concentrated and further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 (16/600) column (Cytiva) in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 400 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT. Purified ShTnsB was concentrated to 7 mg mL−1 using 30,000 kDa molecular weight cut-off centrifugal filters (Merck Millipore), and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

For ShTniQ, cells were harvested and resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 5 mM imidazole supplemented with 1 μg mL−1 Pepstatin and 200 μg mL−1 AEBSF and lysed by ultrasonication. The cleared lysate was applied to a 5 mL Ni-NTA cartridge and the column was washed in two steps with lysis buffer supplemented with 25 mM imidazole. The protein was eluted with lysis buffer supplemented with 300 mM imidazole. Eluted protein was dialyzed overnight against 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT in the presence of TEV protease. Dialyzed protein was passed through a 5 mL MBPTrap column (Cytiva). The flow-through fraction was concentrated and further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 (16/600) column in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT. Purified ShTniQ was concentrated to 10 mg mL−1 using 10,000 kDa molecular weight cut-off centrifugal filters (Merck Millipore) and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. To produce recombinant ShTniQ protein free of the E. coli S15 contaminant for pull-down experiments and in vitro transposition assays, the protocol above (Protocol 1) was adjusted using the following procedure (Protocol 2). Cells were harvested and resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 5 mM imidazole supplemented with 1 μg mL−1 Pepstatin and 200 μg mL−1AEBSF and lysed by ultrasonication. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 40,000 x g for 30 min at 4°C and applied to two 5 mL Ni-NTA cartridges connected in tandem. The column was washed with 150 mL of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol before elution with 50 mL of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol into two 5 mL MBPTrap cartridges connected in tandem before removal of the Ni-NTA cartridges. The MBPTrap column was washed with 50 mL of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol before elution with 50 mL of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol, 10 mM maltose. Elution fractions were pooled and dialyzed overnight against 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT in the presence of tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease. Dialyzed proteins were loaded onto two 5 mL HiTrap Heparin HP columns connected in tandem, and eluted with a linear gradient of 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 1 M KCl. Elution fractions were pooled, concentrated using 3,000 molecular weight cut-off centrifugal filters (Merck Millipore) and further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 75 (16/600) column in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT yielding pure, monodisperse proteins. Purified proteins were concentrated to 1.5–5.0 mg mL−1, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further usage. Absence of the E. coli S15 in the purified ShTniQ produced using the revised protocol was confirmed by mass spectrometry as described below (see also Table S2).

For expression of EcS15, mutant EcS15, ShS15 and HsRPS13, hexahistidine-MBP-tagged proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 Rosetta2 (DE3) cells (Novagen). Cell cultures were grown at 37°C shaking at 100 rpm until reaching an OD600 of 0.6 and protein expression was induced with 0.4 mM IPTG and continued for 16 h at 18 °C. Harvested cells were resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 1 μg mL−1 Pepstatin, 200 μg mL−1 AEBSF and lysed by ultrasonication at 4°C. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 40,000 x g for 30 min at 4°C and applied to two 5 mL Ni-NTA cartridges connected in tandem. The column was washed with 100 mL of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole before elution with 50 mL of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole. Elution fractions were pooled and diluted with 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl to yield a final salt concentration of 150 mM (EcS15, ShS15 and HsRPS13) or 100 mM (mutant EcS15 proteins). Diluted proteins were loaded onto a 5 mL HiTrap Heparin HP column and eluted with a linear gradient of 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 1 M KCl. Elution fractions were pooled and digested by tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease overnight at 4°C in presence of a final concentration of 1 mM DTT. The protein pool was diluted again with 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl to yield a final salt concentration of 150 mM (EcS15, ShS15 and HsRPS13) or 100 mM (mutant EcS15 proteins), loaded onto a 5 mL HiTrap Heparin HP column and eluted with a linear gradient of 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 1 M KCl. Elution fractions for protein of interest were pooled, concentrated using 3,000 molecular weight cut-off centrifugal filters (Merck Millipore) and further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 75 (16/600) column in 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 250 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT (EcS15, mutant EcS15 and ShS15) or in 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 500 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT (HsRPS13) yielding pure, monodisperse proteins. Purified proteins were concentrated to 2-5 mg mL−1, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further usage.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Samples resulting from purification of TniQ following the Protocol 1 were treated as follows prior to digestion. Proteins were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA; Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 5% and washed twice with ice-cold acetone. The protein pellet was resuspended in 45 μL of digestion buffer (10 mM Tris, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 8.2). Samples resulting from purification of TniQ following the Protocol 2 were directly diluted in digestion buffer (10 mM Tris, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 8.2) and reduced with 2 mM TCEP (tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) and alkylated with 15 mM chloroacetamide at 30°C for 30 min. Digestion was performed for all samples using the same procedure: 500 ng of Sequencing Grade Trypsin (Promega) were added for digestion carried out in a microwave instrument (Discover System, CEM) for 30 min at 5 W and 60°C. The samples were dried to completeness and re-solubilized in 20 μL of MS sample buffer (3% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid).

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed on an Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) equipped with a Digital PicoView source (New Objective) and coupled to an M-Class UPLC (Waters). Solvent composition at the two channels was 0.1% formic acid for channel A and 0.1% formic acid, 99.9% acetonitrile for channel B. For each sample, 80 ng of peptides were loaded on a commercial ACQUITY UPLC M-Class Symmetry C18 Trap Column (100 Å, 5 μm, 180 μm × 20 mm, Waters) connected to a ACQUITY UPLC M-Class HSS T3 Column (100 Å, 1.8 μm, 75 μm × 250 mm, Waters). The peptides were eluted at a flow rate of 300 nL min−1. After a 3 min initial hold at 5% B, a gradient from 5 to 35% B in 60 min and 35 to 40% B in additional 5 min was applied. The column was cleaned after the run by increasing to 95% B and holding 95% B for 10 min prior to re-establishing loading condition.

The mass spectrometer was operated in data-dependent mode (DDA), funnel RF level at 60%, and heated capillary temperature at 275 °C. Full-scan MS spectra (350–1500 m/z) were acquired at a resolution of 120′000 for sample from Protocol 2 and of 70′000 for sample from Protocol 1 at 200 m/z after accumulation to a target value of 3′000′000, followed by HCD (higher-energy collision dissociation) fragmentation on the twelve most intense signals per cycle. Ions were isolated with a 1.2 m/z isolation window and fragmented by higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) using a normalized collision energy of 28% for sample from Protocol 2 and of 25% for sample from Protocol 1. HCD spectra were acquired at a resolution of 30′000 and a maximum injection time of 50 ms for sample from Protocol 2 and at a resolution of 35′000 and a maximum injection time of 120 ms for sample from Protocol 1. The automatic gain control (AGC) was set to 100′000 ions. Charge state screening was enabled and singly and unassigned charge states were rejected. Precursor masses previously selected for MS/MS measurement were excluded from further selection for 30 s, and the exclusion window tolerance was set at 10 ppm. The samples were acquired using internal lock mass calibration on m/z 371.1010 and 445.1200. The mass spectrometry proteomics data were handled using the local laboratory information management system (LIMS).58

The acquired raw MS data were processed by MaxQuant (version 1.6.2.3), followed by protein identification using the integrated Andromeda search engine.59 Spectra were searched against a Uniprot E. coli proteome database (UP000000625, taxonomy 83,333, version from 2021 to 07–12), concatenated to its reversed decoyed fasta database and the sequences of the proteins of interest. Acetyl (Protein N-term) oxidation (M) and deamidation (NQ) were set as variable modification. Enzyme specificity was set to trypsin/P allowing a minimal peptide length of 7 amino acids and a maximum of two missed-cleavages. MaxQuant Orbitrap default search settings were used. The maximum false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 0.01 for peptides and 0.05 for proteins. Peptide identifications were accepted if they achieved a false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 0.1% by the Scaffold Local FDR algorithm. Protein identifications were accepted if they achieved an FDR of less than 1.0% and contained at least 2 identified peptides. Data are provided in Table S2.

sgRNA preparation

DNA sequence encoding the T7 RNA polymerase promoter upstream of the ShCas12k-sgRNA was sourced as a gBlock (IDT), cloned into a pUC19 plasmid using restriction digest with BamHI and EcoRI, and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The sequence encoding the T7 RNA polymerase promoter and sgRNA was amplified by PCR and purified by ethanol precipitation for use as template for in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase as described previously.62 The transcribed RNA was gel purified, precipitated with 70% (v/v) ethanol, dried and dissolved in nuclease-free water.

Cryo-EM sample preparation and data collection: Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex and Cas12k-TnsC non-productive complex

The sample for cryo-EM analysis was produced by stepwise assembly on Strep-Tactin matrix as follows. First, sgRNA was mixed with hexahistidine-StrepII-tagged ShCas12k (Strep-Cas12k) in assembly buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 250 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT) and incubated 20 min at 37°C to allow formation of a binary Strep-Cas12k-sgRNA complex. Next, a target dsDNA duplex (Table S3) was added to the reaction in a Strep-Cas12k:sgRNA:dsDNA molar ratio of 1:1.2:2 and incubated for 20 min at 37°C, yielding an assembled Strep-Cas12k-sgRNA-target DNA complex. The final 30 μL reaction contained 20 μg (at a concentration of 8.4 μM, 0.7 mg mL−1) Strep-Cas12k, 10.1 μM sgRNA, and 16.9 μM DNA in assembly buffer. The resulting sample was then mixed with 25 μL Strep-Tactin beads (iba) equilibrated in pull-down wash buffer 1 (20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 250 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.05% Tween 20) and incubated 30 min at 4°C on a rotating wheel. The beads were washed three times with pull-down wash buffer 1 to remove excess nucleic acids. The beads were resuspended in 250 μL of pull-down wash buffer 1 before ShTniQ (purified following Protocol 1 and thus containing co-purifying E. coli S15) and ShTnsC were added in 30-fold and 10-fold molar excess, respectively. ATP was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. The sample was incubated for 30 min at 37°C, then washed three times with pull-down wash buffer 2 (20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 250 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, 0.05% Tween 20) and eluted with pull-down elution buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 250 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, 5 mM desthiobiotin). The eluted sample was analyzed by SDS-PAGE using Any kDa gradient polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad) stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue and by denaturing PAGE on a 10% polyacrylamide- 7 M urea gel upon proteinase K digestion for 15 min at 37°C prior to preparation of cryo-EM grids. Of note, recombinantly produced S15 was not added to the sample subjected to structural analysis. S15 was identified as a component of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex after structure determination and model building and was confirmed to have co-purified as contaminant with TniQ using mass spectrometry as described above (see also Table S2). Prior to structural analysis by cryo-EM, complex homogeneity was assessed by negative stain electron microscopy. For preparation of negative-stain EM grids, samples (4 μL) were applied to glow-discharged continuous carbon film supported copper grids (CF300-CU-50 grids, Electron Microscopy Sciences). After 1 min incubation, the grids were washed once with 4 μL of 2% (w/v) uranyl formate and stained in a 4 μL drop of 2% uranyl formate during a total of 1 min prior blotting. Negatively-stained specimens were imaged using a FEI Tecnai G2 Spirit transmission electron microscope operated at an acceleration voltage of 120 kV. Data were acquired at the nominal magnification indicated in figure legends.

For preparation of cryo-EM grids, 2.5 μL of sample was applied to glow-discharged 200-mesh copper 2 nm C R1.2/1.3 cryo-EM grids (Quantifoil Micro Tools), blotted 3 s at 75% humidity, 4°C, plunge frozen in liquid ethane (using a Vitrobot Mark IV plunger, FEI) and stored in liquid nitrogen. Cryo-EM data collection was performed on a FEI Titan Krios G3i microscope (University of Zurich, Switzerland) operated at 300 kV equipped with a Gatan K3 direct electron detector in super-resolution counting mode. A total of 16,165 movies were recorded at a calibrated magnification of 130,000× resulting in super-resolution pixel size of 0.325 Å. Each movie comprised 36 subframes with a total dose of 67.68 e− Å−2. Data acquisition was performed with EPU Automated Data Acquisition Software for Single Particle Analysis (ThermoFisher Scientific) with three shots per hole at −1.0 μm to −2.4 μm defocus (0.2 μm steps).

Data processing and model building: Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex and Cas12k-TnsC non-productive complex

Images were processed using RELION42 and SPHIRE43 software packages. All movies were motion-corrected and dose-weighted with MotionCor245 (in RELION). Aligned, non-dose-weighted micrographs were then used to estimate the contrast transfer function (CTF) with Gctf.46 Motion corrected movies were linked to SPHIRE and corresponding image shift information converted to enable drift assessment in SPHIRE (0-60 Å overall drift selected). Single particles were picked with crYOLO47 (gmodel_phosnet_202005_N63_c17.h5) on JANNI-denoised micrographs (gmodel_janni_20190703.h5). Particle coordinates (3.1 million) were linked back to RELION, extracted with a box size of 480 pix (binned 4-fold) and 2D classified. All particle representing classes were selected for a 3D classification using a loosely masked volume of the Cas12k-sgRNA-dsDNA complex (PDB: 7PLA, EMDB: EMD-1348615) as reference to force orientational alignment on the Cas12k-sgRNA part. A 3D class showing features expanding the input density was subclassified without a mask to allow for identification of sub-populations. Sub-populations with new features were used as input (masked 3D classification) to identify all corresponding particles. Classes were inspected visually before unbinning, re-extraction and 3D refinement (RELION) in real scale. Two rounds (one round for the non-productive complex) of Bayesian particle polishing (RELION) and CTF refinement (RELION) prior to final refinements (RELION) resulted in a reconstruction of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex from 75 k particles at an overall resolution of 3.3 Å and for the Cas12k-TnsC non-productive complex from 133 k particles at an overall resolution of 4.1 Å. The local resolution was calculated based on the resulting maps using the local resolution functionality (RELION) and plotted on the maps using UCSF Chimera.51 The structural models were built in Coot.57

To generate the structural model of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex, the structures of the Cas12k-sgRNA-target DNA (PDB: 7PLA15) and TniQ-capped TnsC filament complex (described below) were docked in the new density and used as starting model. Model building revealed a well resolved proteinaceous density located between the tracrRNA and Cas12k corresponding to an unidentified component. An initial poly-alanine structural model complemented with specific amino acids in regions of well-defined side chain density was built de novo. Subjecting this model to a DALI55 search identified the prokaryotic ribosomal S15 protein as the closest match. The presence of E. coli S15 protein in the cryo-EM sample was subsequently confirmed by mass spectrometry (see also Table S2). The complete model of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex was refined in Coot using restraints for the nucleic acids calculated with the LibG56 script (base pair, stacking plane and sugar pucker restraints) in ccp4 and finally refined using Phenix.48,49,50 Real space refinement was performed with the global minimization and atomic displacement parameter (ADP) refinement options selected. Secondary structure restraints, side chain rotamer restraints, and Ramachandran restraints were used. Key refinement statistics are listed in Table S1. The final atomic model includes Cas12k residues 1-142 and 174-636, sgRNA nucleotides 5-250, 41 nucleotides of each TS and NTS DNA, TniQ residues 9–167, S15 residues 3-87, seven TnsC molecules (each with residues 17-276), two zinc and seven magnesium cations and seven ATP molecules.

To generate the structural model of the Cas12k-TnsC non-productive complex, the structures of the Cas12k-transposon recruitment complex (sgRNA and parts of Cas12k), the Cas12k-sgRNA-target DNA complex (RuvC domain, PDB: 7PLA15) and TnsC filament complex (TnsC-filament, PDB: 7PLH15 were docked into the density as rigid bodies and used as starting model. Movements of the Cas12k REC domain were fitted using rigid body refinement and simulated annealing in Phenix48,49,50; the final model was refined using rigid body refinement in Phenix.48,49,50 Secondary structure restraints, side chain rotamer restraints, and Ramachandran restraints were used. Key refinement statistics are listed in Table S1. The final atomic model includes Cas12k residues 1-142, 174-242 and 277-636, sgRNA nucleotides 5-168, 170-240, 41 nucleotides of each TS and NTS DNA, nine TnsC molecules (each with residues 17-276), nine magnesium cations and nine ATP molecules.

The quality of the atomic models, including basic protein and DNA geometry, Ramachandran plots, clash analysis and model cross-validation, was assessed with MolProbity53,54 and the validation tools in Phenix. Structural superposition was performed in Coot using the secondary structure matching63 (SSM) function. Figure preparation for maps and models and calculation of map contour levels was performed using UCSF ChimeraX52

cryo-EM sample preparation and data collection: TniQ-capped TnsC filament complex

For the reconstitution of TnsC filaments bound to TniQ, wild-type TnsC protein was diluted to a final concentration of 15 μM in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT and 1 mM ATP and mixed at a ratio of 1:25 (TnsC:DNA) with a double-stranded 69-bp duplex DNA oligonucleotide (Table S3) and at a 1:2 ratio (TnsC:TniQ) with TniQ in a 22.4 μL reaction volume. For preparation of cryo-EM grids, 3.0 μL of sample was applied to glow-discharged 200-mesh copper 2 nm C R1.2/1.3 cryo-EM grids (Quantifoil Micro Tools), blotted 1 s at 100% humidity, 4°C, plunge frozen in liquid ethane (using a Vitrobot Mark IV plunger, FEI) and stored in liquid nitrogen. Cryo-EM data collection was performed on a FEI Titan Krios G3i microscope (University of Zurich, Switzerland) operated at 300 kV equipped with a Gatan K3 direct electron detector in super-resolution counting mode. A total of 10,436 movies were recorded at a calibrated magnification of 130,000× resulting in super-resolution pixel size of 0.325 Å. Each movie comprised 36 subframes with a total dose of 66.036 e− Å−2. Data acquisition was performed with EPU Automated Data Acquisition Software for Single Particle Analysis (ThermoFisher Scientific) with three shots per hole at −1.0 μm to −2.4 μm defocus (0.2 μm steps).

Data processing and model building: TniQ-capped TnsC filament complex