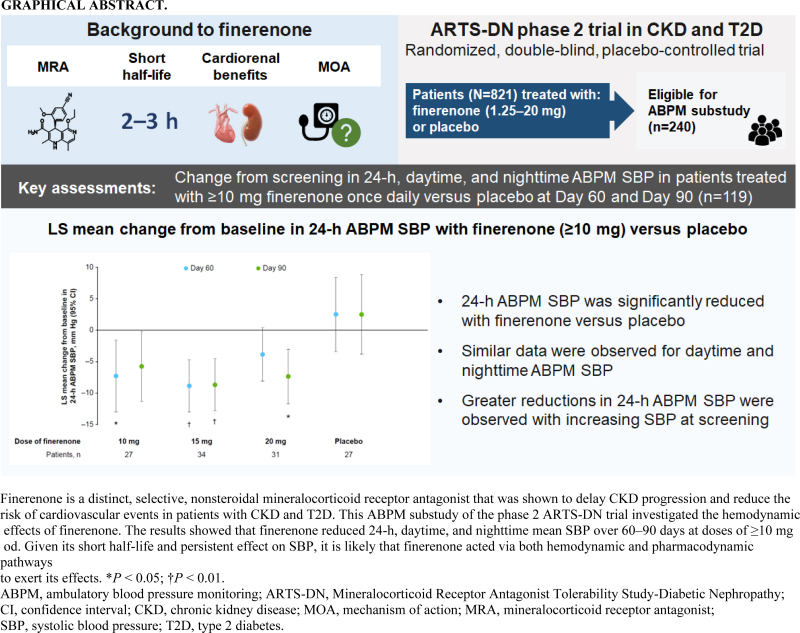

Objective:

Finerenone is a selective nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist with a short half-life. Its effects on cardiorenal outcomes were thought to be mediated primarily via nonhemodynamic pathways, but office blood pressure (BP) measurements were insufficient to fully assess hemodynamic effects. This analysis assessed the effects of finerenone on 24-h ambulatory BP in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes.

Methods:

ARTS-DN (NCT01874431) was a phase 2b trial that randomized 823 patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease, with urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g and estimated glomerular filtration rate of 30–90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 to placebo or finerenone (1.25–20 mg once daily in the morning) administered over 90 days. Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) over 24 h was performed in a subset of 240 patients at screening, Day 60, and Day 90.

Results:

Placebo-adjusted change in 24-h ABPM systolic BP (SBP) at Day 90 was –8.3 mmHg (95% confidence interval [CI], –16.6 to 0.1) for finerenone 10 mg (n = 27), –11.2 mmHg (95% CI, –18.8 to –3.6) for finerenone 15 mg (n = 34), and –9.9 mmHg (95% CI, –17.7 to –2.0) for finerenone 20 mg (n = 31). Mean daytime and night-time SBP recordings were similarly reduced and finerenone did not increase the incidence of SBP dipping. Finerenone produced a persistent reduction in SBP over the entire 24-h interval.

Conclusions:

Finerenone reduced 24-h, daytime, and night-time SBP. Despite a short half-life, changes in BP were persistent over 24 h with once-daily dosing in the morning.

Keywords: albuminuria, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, chronic kidney disease, finerenone, type 2 diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) are at elevated risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression and cardiovascular (CV) disease; adequate control of blood pressure (BP) is essential to address this cardiorenal risk [1]. Although the steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) spironolactone and eplerenone are guideline recommended for the treatment of resistant hypertension, their use in patients with CKD is frequently complicated by hyperkalemia [2]. European guidelines discourage their use in patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and serum potassium level >4.5 mmol/l [3]. Not surprisingly, the use of spironolactone to treat hypertension in patients with CKD was in <5% of the patients in a 2019 international survey [4]. Finerenone is a novel, selective, nonsteroidal MRA, which was shown to delay CKD progression and reduce the risk of CV events in patients with CKD and T2D with only a modest effect on office BP in the pivotal phase 3 Finerenone in Reducing Kidney Failure and Disease Progression in Diabetic Kidney Disease (FIDELIO-DKD) trial [5]. These findings were also confirmed in the recently published phase 3 FInerenone in Reducing Cardiovascular Mortality and Morbidity in Diabetic Kidney Disease (FIGARO-DKD) trial [6]. However, few data exist on the hemodynamic effects of finerenone in patients with CKD and the BP data from FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD were limited to office measurements.

The Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist Tolerability Study-Diabetic Nephropathy (ARTS-DN) trial was a multicenter, dose-finding, phase 2b clinical trial of finerenone in patients with CKD and T2D [7]. The primary aim of ARTS-DN was to investigate effects of finerenone on albuminuria and the trial included ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) in a subset of patients, in whom 24-h ambulatory BP was measured at baseline, 60 days after the start of treatment, and at the last on-treatment visit (Day 90). The number of BP measurements over 24 h improves the assessment of BP and allows a better evaluation of circadian variation and 24-h control than is possible from the available FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD data. Compared with office BP, ABPM has been suggested to be a stronger predictor of clinical outcomes [8,9].

To obtain further insights into the mechanism of action of finerenone, the objective of this study was to analyze the effect of finerenone on 24-h ABPM and to evaluate its circadian profile, and to compare these to the time course of concurrently obtained office BP in patients with CKD and T2D.

METHODS

Study design and outcomes

ARTS-DN was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase 2b study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01874431) designed to compare the efficacy and safety of finerenone administered at doses of 1.25–20 mg once daily with that of placebo when added to standard of care with a renin–angiotensin system blocker in patients with CKD and T2D. Patients were directed to take the study drug in the morning. Patients with T2D, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) ≥30 mg/g, and eGFR >30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 were included. Patients were required to be receiving treatment with at least the minimum recommended dose of a renin–angiotensin system inhibitor prior to the screening visit and have a serum potassium ≤4.8 mmol/l at screening. Full details and trial results have been published previously [7].

For office BP measurements, 3 BP measurements were taken at 2-min intervals with the patient in a sitting position after resting for ≥10 min, at the run-in and screening visits, and on Days 1, 7, 30, 60, and 90 (or at discontinuation), and at the follow-up visit. The resting period and intervals between measurements were based on published guidance [10–12]. Day 90 BP measurements were taken before administration of the study drug.

Twenty-four–hour ABPM was performed using the Spacelabs Medical Model 90207 Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitor on a subset of patients at selected sites (Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content) at the screening visit, and on Days 60 and 90. Day 60 and 90 ABPM started during the visit and finished 24 h later the following day. Twenty-four–hour profiles were recorded at 15-min intervals from 0600 to 2200 h (daytime) and at 30-min intervals from 2200 to before 0600 h (night-time). During 24-h ABPM, patients refrained from strenuous physical exertion. A nocturnal dip in systolic BP (SBP) was defined as a night-time SBP >10% lower than daytime SBP. Invalid ABPM measurements were excluded from the analysis. A measurement was considered invalid if the percentage of successful readings was below 80% for a visit. The multiple assessments per visit were summarized as averages for 24-h, daytime, and night-time.

In the United States and Europe, finerenone is currently indicated to reduce the risk of sustained eGFR decline, end-stage kidney disease, CV death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and hospitalization for heart failure in adult patients with CKD associated with T2D at doses of 10 or 20 mg once daily. Analyses presented therefore focus on doses 10 mg or more once daily in this trial. Demographics and safety data are presented for patients in the ABPM substudy.

Statistical analyses

All analyses are conducted in patients with ABPM measurements at the screening visit in the safety analysis set, which included all randomized patients who have taken at least one dose of study drug and with data after beginning of treatment. One patient treated with placebo reported a change in 24-h ABPM SBP that was deemed outside of a clinically plausible range and was excluded from all analyses.

Absolute changes from baseline for office BP, 24-h ABPM, and daytime and night-time ABPM averages were analyzed using a mixed model, including treatment group, visit, base value, and treatment∗visit interaction as covariates. Least-squares (LS) mean treatment differences between the finerenone dose groups and placebo are presented including 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Odds ratios and 95% CIs for nocturnal dippers at Day 90 were calculated using a logistic regression model with the baseline status and treatment group as covariates. Missing values for ABPM analyses were imputed with multiple imputation using the baseline value, available Day 60 and Day 90 values, and treatment group. Subgroup analyses to determine the effect of baseline aldosterone, urine sodium, age, sex, eGFR, and UACR were performed by analysis of covariance with factors treatment group and baseline value as covariates. Changes in ambulatory SBP at hourly time intervals are presented as means ± standard error. Comparisons of treatment effects on SBP measured by office BP and 24-h ABPM, and daytime and night-time ABPM were analyzed using joint mixed models with factors treatment group, type of measurement, baseline value, and treatment ∗ type of measurement interaction as covariates, and patient as random factor.

RESULTS

Patients

A total of 821 patients were randomized and treated with either finerenone or placebo in the ARTS-DN study. Of these, 240 patients (2% from Asia, 83% from Europe, 5% from North America, and 10% from other parts of the world) were included in this ABPM substudy. ABPM was performed in 240 patients at screening, 176 patients at Day 60, and 154 patients at Day 90; one patient was excluded from the substudy analysis because of measurements deemed to be outside of a clinically plausible range (Figure 1, Supplemental Digital Content). Of the 239 patients included in the ABPM substudy analysis who were treated with placebo or finerenone doses of 1.25–20 mg, mean office SBP was 138.9 ± 14.0 mmHg and mean office diastolic BP (DBP) was 78.2 ± 9.3 mmHg at baseline. Median UACR was 217 mg/g, and 44.8% (n = 107) of patients had UACR ≥300 mg/g. Baseline characteristics were generally similar between treatment arms, with some variations in median aldosterone and N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide levels (Table 1 and Table S2, Supplemental Digital Content). Use of antihypertensive therapies at baseline was similar between treatment arms, with an overall mean number of 2.7 antihypertensive therapies per patient (Table S3, Supplemental Digital Content).

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients in ARTS-DN ABPM substudy

| Placebo (n = 27) | 10 mg finerenone (n = 27) | 15 mg finerenone (n = 34) | 20 mg finerenone (n = 31) | Totala (N = 239) | |

| Mean age (SD), years | 60.8 (8.4) | 62.1 (7.7) | 63.8 (8.7) | 66.1 (11.3) | 63.4 (9.4) |

| Male, n (%) | 20 (74.1) | 19 (70.4) | 26 (76.5) | 20 (64.5) | 183 (76.6) |

| Mean office SBP, mmHg (SD) | 138.6 (13.1) | 143.2 (12.4) | 135.8 (14.0) | 138.5 (12.2) | 138.9 (14.0) |

| Mean ABPM SBP (24 h), mmHg (SD) | 142.6 (14.7) | 145.6 (15.5) | 137.1 (12.7) | 136.3 (12.3) | 139.5 (14.2) |

| Mean office DBP, mmHg (SD) | 77.5 (10.2) | 79.9 (9.6) | 76.4 (10.3) | 79.4 (7.8) | 78.2 (9.3) |

| Mean ABPM DBP (24-h), mmHg (SD) | 79.1 (8.7) | 80.8 (11.8) | 76.7 (9.4) | 75.7 (9.5) | 77.7 (9.1) |

| Median UACR (range), mg/g | 217 (43 to 1707) | 293 (34 to 3917) | 121 (28 to 2496) | 220 (4 to 1560) | 217 (4 to 4948) |

| Mean serum potassium (SD), mmol/l | 4.3 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.4) | 4.2 (0.5) | 4.3 (0.5) | 4.3 (0.4) |

| Mean eGFR, (SD), ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 69.4 (21.8) | 67.9 (18.8) | 64.3 (22.8) | 67.2 (21.2) | 68.2 (21.1) |

| Mean HbA1c, (SD), % | 7.6 (1.5) | 7.9 (1.4) | 7.3 (1.2) | 7.5 (1.1) | 7.5 (1.3) |

| UACR ≥300 mg/g at screening, n (%) | 12 (44.4) | 12 (44.4) | 15 (44.1) | 13 (41.9) | 107 (44.8) |

| Median aldosterone level (range), pg/ml | 65.0 (3.8 to 238.5) | 44.2 (2.8 to 205.4) | 32.6 (1.0 to 199.9) | 51.0 (7.2 to 242.9) | 45.4 (1.0 to 283.0) |

| Median NT-proBNP level (range), pg/ml | 106.0 (10.2 to 1110.2) | 96.6 (10.2 to 611.9) | 85.4 (10.2 to 765.3) | 95.8 (10.2 to 1195.0) | 93.2 (10.2 to 8212.3) |

Data are at baseline unless specified otherwise. 120 patients in the study were treated with <10-mg dose of finerenone. ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; ARTS-DN, Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist Tolerability Study-Diabetic Nephropathy; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation; UACR, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

All doses of finerenone plus placebo.

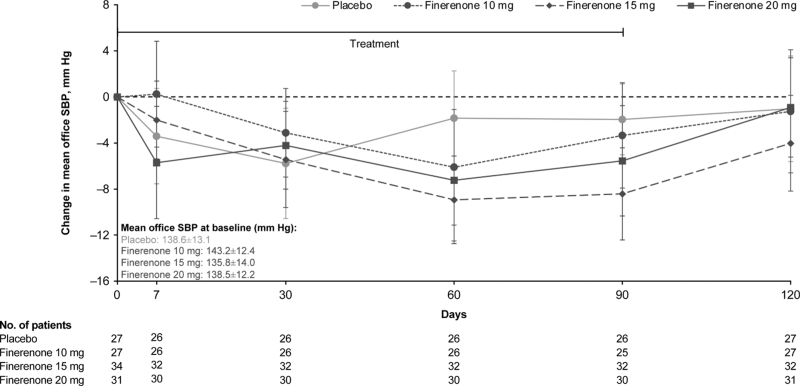

Change in office SBP with finerenone

Analysis on patients treated with placebo and finerenone (10–20 mg) showed inconsistent and variable placebo-adjusted changes in office SBP from baseline to Day 60 and Day 90: –4.3 mmHg (95% CI, –10.6 to 2.1) and –1.4 mmHg (95% CI, –6.8 to 4.0), respectively, for finerenone 10 mg; –7.1 mmHg (95% CI, –12.6 to –1.6) and –6.5 mmHg (95% CI, –11.4 to –1.5), respectively, for finerenone 15 mg; and –5.4 mmHg (95% CI, –12.0 to 1.1) and –3.6 mmHg (95% CI, –9.2 to 2.0), respectively for finerenone 20 mg (Fig. 1). Smaller differences in office SBP were observed relative to placebo at the follow-up visit, 4 weeks after cessation of treatment: –0.2 mmHg (95% CI, –7.1 to 6.7), –3.0 mmHg (95% CI, –9.0 to 3.1), and 0.1 mmHg (95% CI, –6.0 to 6.3) for 10 mg, 15 mg, and 20 mg finerenone, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Time course of change in office SBP. Change in office SBP from baseline to Day 120 with finerenone compared with placebo. Mixed model analysis with factors treatment group, time, baseline value, and treatment ∗ time interaction as covariates. Data are expressed as LS mean change from baseline ± 95% CI. CI, confidence interval; LS, least-squares; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

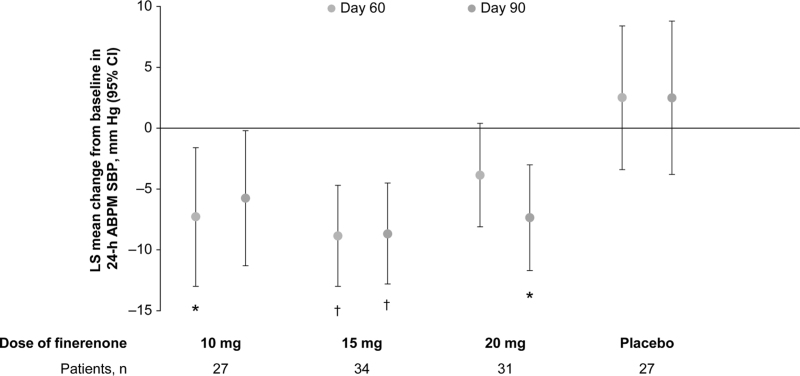

Change in 24-h, daytime, and night-time ambulatory BP monitoring with finerenone

Of the 240 patients who had baseline ABPM and were treated with placebo or finerenone doses of 1.25–20 mg, 154 (64%) had adequate ABPM following treatment. Therefore, we used multiple imputation to account for missing data as the primary method of analysis. One patient treated with placebo was excluded from analyses because of a change in ABPM that was deemed outside of a clinically plausible range, so a total of 153 patients were monitored during the study.

Finerenone reduced the LS mean change from baseline in 24-h ABPM SBP with significant changes observed with 10 mg at Day 60 (–7.3 mmHg; 95% CI, –13.0 to –1.6), 15 mg at Day 60 (–8.9 mmHg; 95% CI, –13.0 to –4.7), 15 mg at Day 90 (–8.7 mmHg, 95% CI, –12.8 to –4.5), and 20 mg at Day 90 (–7.4; 95% CI, –11.7 to –3.0) compared with placebo (2.5 mmHg; 95% CI, –3.4 to 8.4 for Day 60 and 95% CI, –3.8 to 8.8 for Day 90) (Fig. 2). Placebo-adjusted changes in 24-h ABPM SBP were –9.8 mmHg (95% CI, –18.0 to –1.6) and –8.3 mmHg (95% CI, –16.6 to 0.1) for finerenone 10 mg, –11.4 mmHg (95% CI, –18.5 to –4.3) and –11.2 mmHg (95% CI, –18.8 to –3.6) for finerenone 15 mg, and –6.4 mmHg (95% CI, –13.6 to 0.9) and –9.9 mmHg (95% CI, –17.7 to –2.0) for finerenone 20 mg at Day 60 and Day 90, respectively, with LS mean change from baseline of 2.5 mmHg for placebo at both Day 60 and Day 90 (Table 2 and Table S4, Supplemental Digital Content). Similar placebo-adjusted changes were observed in daytime ABPM SBP and night-time ABPM SBP at Day 60 and Day 90 (Table 2 and Table S4, Supplemental Digital Content) as well as in the corresponding observed case analysis (Table S5, Supplemental Digital Content).

FIGURE 2.

LS mean change from baseline in 24-h ABPM SBP at Day 60 and Day 90 using multiple imputation. Reduction in SBP was observed for 24-h ABPM with finerenone ≥10 mg relative to baseline. Mixed model analysis with factors treatment group, time, baseline value, and treatment ∗ time interaction as covariates. LS mean change from baseline with 95% CI. Missing data at Day 60 and Day 90 are imputed with multiple imputation for ABPM analyses. ∗P < 0.05; †P < 0.01. ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; CI, confidence interval; LS, least-squares; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

TABLE 2.

ABPM SBP at baseline, Day 60, and Day 90 with multiple imputation

| 24-h ABPM | Daytime ABPM | Night-time ABPM | |||||

| Group | Phase | Adjusted change (95% CI) | Treatment effect (95% CI) | Adjusted change (95% CI) | Treatment effect (95% CI) | Adjusted change (95% CI) | Treatment effect (95% CI) |

| Placebo (n = 27) | Baseline, mean SBP, mmHg (SD) | 142.6 (14.7) | 145.1 (14.9) | 133.0 (17.2) | |||

| Day 60 | 2.5 (–3.4 to 8.4) | Ref | 2.1 (–3.8 to 7.9) | Ref | 3.9 (–3.2 to 11.1) | Ref | |

| Day 90 | 2.5 (–3.8 to 8.8) | Ref | 2.7 (–3.5 to 8.9) | Ref | 1.6 (–6.6 to 9.8) | Ref | |

| Finerenone 10 mg (n = 27)a | Baseline, mean SBP, mmHg (SD) | 145.7 (15.5) | 147.5 (16.1) | 137.0 (14.6) | |||

| Day 60 | –7.3 (–13.0 to –1.6) | –9.8 (–18.0 to –1.6) | –7.5 (–13.4 to –1.6) | –9.6 (–17.8 to –1.3) | –5.9 (–11.5 to –0.2) | –9.8 (–18.8 to –0.8) | |

| Day 90 | –5.8 (–11.3 to –0.2) | –8.3 (–16.6 to 0.1) | –5.6 (–11.5 to 0.2) | –8.3 (–16.7 to 0.2) | –6.7 (–13.1 to –0.3) | –8.3 (–18.5 to 2.0) | |

| Finerenone 15 mg (n = 34) | Baseline, mean SBP, mmHg (SD) | 137.1 (12.7) | 138.8 (12.5) | 130.6 (16.2) | |||

| Day 60 | –8.9 (–13.0 to –4.7) | –11.4 (–18.5 to –4.3) | –9.0 (–13.4 to –4.6) | –11.1 (–18.3 to –3.8) | –7.7 (–12.1 to –3.3) | –11.6 (–19.9 to –3.2) | |

| Day 90 | –8.7 (–12.8 to –4.5) | –11.2 (–18.8 to –3.6) | –8.4 (–12.5 to –4.2) | –11.0 (–18.5 to –3.5) | –9.8 (–15.3 to –4.4) | –11.4 (–21.2 to –1.7) | |

| Finerenone 20 mg (n = 31) | Baseline, mean SBP, mmHg (SD) | 136.3 (12.3) | 137.6 (12.2) | 131.1 (16.1) | |||

| Day 60 | –3.9 (–8.1 to 0.4) | –6.4 (–13.6 to 0.9) | –3.1 (–7.8 to 1.5) | –5.2 (–12.6 to 2.3) | –6.2 (–10.2 to –2.1) | –10.1 (–18.4 to –1.7) | |

| Day 90 | –7.4 (–11.7 to –3.0) | –9.9 (–17.7 to –2.0) | –6.8 (–11.4 to –2.2) | –9.5 (–17.4 to –1.6) | –9.1 (–13.7 to –4.5) | –10.7 (–20.0 to –1.3) | |

Mixed model analysis with factors treatment group, time, baseline value, and treatment × time interaction as covariates. Adjusted changes are expressed as LS mean change from baseline with 95% CI and treatment effect is expressed as LS mean difference from placebo with 95% CI. Missing data at Day 60 and Day 90 were imputed with multiple imputation.

ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; CI, confidence interval; LS, least-squares; Ref, reference; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

n = 26 for night-time.

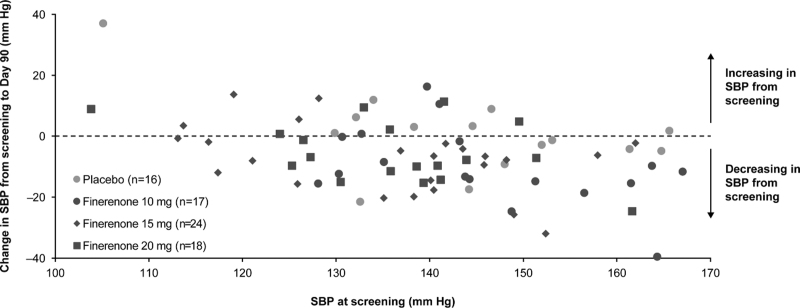

Comparison of office SBP and 24-h ABPM SBP by treatment group showed no statistically significant differences in changes between office and ABPM SBP (Table S6, Supplemental Digital Content). Greater reductions in 24-h ABPM SBP were observed with increasing SBP at screening (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Scatterplot of average 24-h SBP by ABPM at screening and change from screening to Day 90. Individual patient data from 24-h ABPM measurements at screening and Day 90. One patient who was treated with placebo was excluded from the analysis because of a change in ABPM that was deemed outside of a clinically plausible range (SBP of 121.3 mmHg at screening and an increase in SBP of 72.2 mmHg at Day 90). ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Changes in ABPM DBP are presented in Figure 2, Supplemental Digital Content and Table S7, Supplemental Digital Content and change in office and ABPM DBP without multiple imputation is presented in Table S8, Supplemental Digital Content.

Subgroup analyses according to baseline aldosterone, urine sodium, age, sex, eGFR, and UACR suggested no significant differences according to baseline characteristics (P-interaction > 0.05; Figure 3, Supplemental Digital Content).

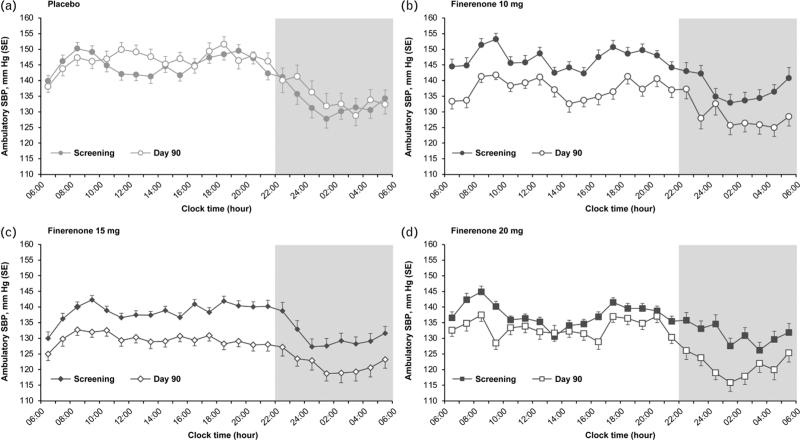

Ambulatory BP monitoring time course over 24 h

Mean SBP at hourly intervals demonstrated a similar pattern in SBP across treatment groups at screening, with lower nocturnal than daytime SBP (Fig. 4). The magnitude of the reduction in SBP with finerenone at Day 90 was persistent across all time points, with the mean Day 90 ambulatory SBP curve generally below that of the mean screening values. Comparison of the LS means difference between daytime and night-time ABPM measurements found no significant differences in the effect of placebo or finerenone between day and night (Table S9, Supplemental Digital Content).

FIGURE 4.

Change in SBP over 24 h recorded by ABPM. Change in SBP as recording by ABPM in patients treated with placebo (n = 16) (a), finerenone 10 mg (n = 17) (b), finerenone 15 mg (n = 24) (c), and finerenone 20 mg (n = 18) (d). Mean SBP at hourly intervals demonstrated a similar pattern in SBP across treatment groups at screening, with lower nocturnal than daytime SBP. Reduction in SBP with finerenone at Day 90 was persistent across all time points and was generally below that of the mean screening values. ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SE, standard error.

Although fewer patients in the placebo group experienced a Day 90 nocturnal dip in SBP than at screening (26.7% and 40.7%, respectively), we found no evidence of an increase in nocturnal dipping in SBP in patients treated with finerenone. Compared with placebo, the odds ratios for nocturnal dipping with finerenone versus placebo were as follows: 1.65 (95% CI, 0.36–7.52), 1.69 (95% CI, 0.43–6.72), and 2.88 (95% CI, 0.73–11.40) for finerenone 10, 15, and 20 mg, respectively.

Safety

Incidence of any treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) was similar across the finerenone dose groups included in the ABPM analysis (Table S10, Supplemental Digital Content). Incidence of treatment-emergent hyperkalemia was low, occurring in one patient in the finerenone 5 mg group and one patient in the finerenone 15 mg group. Serious AEs occurred in 3.3% of patients receiving finerenone.

DISCUSSION

In the ARTS-DN study, we demonstrated that finerenone administration had a modest and inconsistent effect in reducing office BP from baseline. In contrast, 24-h ABPM SBP was significantly reduced from baseline with finerenone. Compared with placebo, finerenone also reduced daytime and night-time SBP similarly. Although the study was limited by a small sample size, there was no evidence of increased dipping with finerenone.

It is well recognized that renal epithelial MRs modulate salt and volume handling and BP regulation by the kidney. MRs may also modulate BP through effects on endothelial and vascular function. Reductions in BP load on the vasculature can protect against target organ damage in patients with CKD associated with T2D. Therefore, the impact of MRAs including finerenone on pathways regulating BP load on the vasculature should be considered. Reductions in SBP from baseline to Day 90 recorded by ABPM were persistent across 24 h. This is noteworthy because finerenone has a short plasma half-life of approximately 2–3 h, has no active metabolites, and was administered once daily in the morning. This would suggest that the reduction in BP over 24 h, including night-time, observed in this study over 3 months, was not because of pharmacokinetic effects of finerenone.

Although various studies suggest that the end organ protection may be largely independent of the effect of finerenone on office BP, the current findings raise the possibility that substantial reductions in 24-h BP may be contributing to the target organ protection observed with the drug. The relative importance of various mechanistic pathways involved in the hemodynamic effects of finerenone remain to be clarified. Multiple mechanisms have been proposed to modulate cardiac output and vascular resistance responses to nonsteroidal and steroidal MRAs including effects on sodium homeostasis by the kidney, neural function, immune function, and endothelial function [13].

At the investigated doses, the BP effects of finerenone observed with 24-h ABPM were clinically significant. However, the office BP changes were less and recapitulated in another trial. In the ARTS phase 2a study conducted in patients with chronic heart failure and moderate CKD with or without T2D, at a dose of 10 mg once daily, finerenone led to a 4.2 mmHg reduction in office SBP at 4 weeks (versus a 3.1 mmHg reduction with placebo) compared with a 10.1 mmHg reduction in office SBP with spironolactone (mean daily dose 37 mg) [14]. In a meta-analysis of data from trials reporting the effects of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2is) on ambulatory BP, a smaller effect was observed with SGLT-2i treatment than observed here with finerenone, with a mean difference in 24-h SBP on ABPM from baseline to 4–12 weeks of –3.6 mmHg [15]. Although our sample size is limited, and 95% CIs wide, our data suggest that compared with SGLT-2is, the effect of finerenone on ambulatory BP might be much greater. The effects of finerenone on 24-h SBP also provide an explanation for the greater incidence of hypotension seen with finerenone (4.3% finerenone, 2.7% placebo) [16] and fewer AEs of hypertension (6.4% finerenone, 9.0% placebo) in the pooled phase 3 studies [17].

Finerenone is a highly potent and selective competitive antagonist of the MR [18]. Its selectivity versus other steroid hormone receptors is at least 500-fold (for comparison: eplerenone: 20–30-fold, spironolactone: only 3-fold versus the androgen receptor [18]). Finerenone binds to human MR with high affinity (Kd value of 1.52 nmol/l; for comparison, the Kd of aldosterone is 0.5 nmol/l), while the finerenone-MR complex has a half-life of 50 min [19]. Like finerenone, the steroidal MRA eplerenone also has a relative short plasma half-life of only 2.9 h (in healthy human volunteers). Although once-daily eplerenone is effective in lowering BP, Weinberger et al.[20] demonstrated that the BP-lowering efficacy of eplerenone in patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension is more pronounced when given twice daily. However, despite its short half-life, eplerenone administered once daily provides mortality reduction in patients with heart failure [21,22]. Our study demonstrates that once-daily administration of finerenone effectively reduced 24-h ambulatory BP, suggesting that the transcriptional effects of the drug, rather than its short half-life, might be more important in modulating this effect [23].

Our study has several limitations. The ABPM substudy had a small sample size, and differences in baseline variables might affect results as patients were from selected sites and not a randomized comparison. There were many patients who did not have follow-up ABPM measurements. Although we used multiple imputation to account for the uncertainty induced by missing data, these adjustments cannot guarantee whether similar results would be obtained if fewer data were missing. Also, because ABPM was not conducted after washout of the study medication, we cannot be certain if the effects on BP would persist after removal of the study drug. ARTS-DN was a short-term phase 2b study and therefore the long-term effects of finerenone, including the effect on kidney and CV outcomes, could not be observed. An analysis of the phase 3 FIDELIO-DKD study will allow further investigation into longer-term effects of finerenone on BP and clinical outcomes.

In conclusion, the ARTS-DN ABPM substudy has shown that finerenone reduced 24-h, daytime, and night-time SBP compared with placebo. Despite a short half-life, changes in BP were persistent over 24 h with once-daily dosing in the morning, suggesting that finerenone has hemodynamic effects in patients with CKD and T2D that are unlikely to be attributable to its pharmacokinetic properties. These hemodynamic effects provide a biological basis for greater incidence of hypotension, a lower incidence of hypertension, and an early separation in curves of the time to first CV events seen with finerenone.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are indebted to the patients who have participated in this trial, the ARTS-DN study investigators, the study centers who supported the trial, and the study teams.

Sources of funding: The ARTS-DN trial was conducted and funded by Bayer AG. The funder participated in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and approval of the manuscript. Analyses were conducted by the sponsor, and all authors had access to and participated in the interpretation of the data. Medical writing assistance was provided by Kate Weatherall, PhD, of Chameleon Communications International, and was funded by Bayer AG.

Conflicts of interest

L.M.R. has received consultancy fees from Bayer. R.A. reports personal fees and nonfinancial support from Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc., during the conduct of the study; he also reports personal fees and nonfinancial support from Akebia Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Relypsa/Vifor Pharma; he has received personal fees from Diamedica and Reata Pharmaceuticals; he is a member of data safety monitoring committees for Chinook and Vertex; a member of steering committees of randomized trials for Akebia Therapeutics, Bayer, Janssen, and Relypsa Inc.; a member of adjudication committees for Bayer; he has served as associate editor of the American Journal of Nephrology and Nephrology Dialysis and Transplantation and has been an author for UpToDate; and he has received research grants from the U.S. Veterans Administration and the National Institutes of Health. H.H. reports personal fees from Bayer AG, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Alexion Pharma, AstraZeneca, and Vifor Pharma, personal fees from Boehringer AG. G.R.H. does not have any disclosures to declare. S.D.A. has received research support from Abbott Vascular and Vifor Pharma, and personal fees from Abbott Vascular, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, BRAHMS, Cardiac Dimensions, Impulse Dynamics, Novartis, Servier, and Vifor Pharma. G.F. reports lectures fees and/or that he is a committee member of trials and registries sponsored by Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, Novartis, Servier, and Vifor Pharma. He is a senior consulting editor for JACC Heart Failure, and he has received research support from the European Union. BP reports consultant fees for Ardelyx, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Brainstorm Medical, Cereno Scientific, G3 Pharmaceuticals, KBP Biosciences, PhaseBio, Sanofi/Lexicon, Sarfez Pharmaceutical Inc., scPharmaceuticals, SQ Innovation, Tricida, and Vifor Pharma/Relypsa Inc.; he has stock options for Ardelyx, Brainstorm Medical, Cereno Scientific, G3 Pharmaceuticals, KBP Biosciences, Sarfez Pharmaceutical Inc., scPharmaceuticals, SQ Innovation, Tricida, and Vifor Pharma/Relypsa Inc.; he also holds a patent for site-specific delivery of eplerenone to the myocardium (US patent #9931412) and a provisional patent for histone-acetylation-modulating agents for the treatment and prevention of organ injury (provisional patent US 63/045,784). PR reports personal fees from Bayer, during the conduct of the study; he has received research support and personal fees from AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk, and personal fees from Astellas Pharma Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead, Merck, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Mundipharma, Sanofi, and Vifor Pharma. All fees are given to Steno Diabetes Center Copenhagen. RES has received grants, consultancy fees, and honoraria from Bayer. M.L. is an external employee of Bayer AG. A.J. and C.N. are full-time employees of Bayer AG, Division Pharmaceuticals, Germany. P.K. is a co-inventor of finerenone (patents EP2132206B1, US8436180B2) and a full-time employee of Bayer AG. G.L.B. reports research funding, paid to the University of Chicago Medicine, from Bayer, during the conduct of the study; he also reports research funding, paid to the University of Chicago Medicine, from Novo Nordisk and Vascular Dynamics; he acted as a consultant and received personal fees from for Alnylam Merck, and Relypsa, Inc.; he is an editor of American Journal of Nephrology, Nephrology, and Hypertension, and section editor of UpToDate; and he is an associate editor of Diabetes Care and Hypertension Research.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; AE, adverse event; ARTS-DN, Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist Tolerability Study-Diabetic Nephropathy trial; BP, blood pressure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CV, cardiovascular; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FIDELIO-DKD, Finerenone in Reducing Kidney Failure and Disease Progression in Diabetic Kidney Disease; FIGARO-DKD, Finerenone in Reducing Cardiovascular Mortality and Morbidity in Diabetic Kidney Disease; LS, least-squares; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SGLT-2i, sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor; T2D, type 2 diabetes; UACR, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio

Supplemental digital content is available for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension 2018; 71:1269–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal R, Rossignol P, Romero A, Garza D, Mayo MR, Warren S, et al. Patiromer versus placebo to enable spironolactone use in patients with resistant hypertension and chronic kidney disease (AMBER): a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019; 394:1540–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2018; 39:3021–3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Pinho NA, Levin A, Fukagawa M, Hoy WE, Pecoits-Filho R, Reichel H, et al. Considerable international variation exists in blood pressure control and antihypertensive prescription patterns in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2019; 96:983–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Pitt B, Ruilope LM, Rossing P, et al. Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:2219–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitt B, Filippatos G, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Bakris GL, Rossing P, et al. Cardiovascular events with finerenone in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:2252–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Chan JC, Cooper ME, Gansevoort RT, Haller H, et al. Effect of finerenone on albuminuria in patients with diabetic nephropathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 314:884–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fagard RH, Celis H, Thijs L, Staessen JA, Clement DL, De Buyzere ML, et al. Daytime and nighttime blood pressure as predictors of death and cause-specific cardiovascular events in hypertension. Hypertension 2008; 51:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang WY, Melgarejo JD, Thijs L, Zhang ZY, Boggia J, Wei FF, et al. Association of office and ambulatory blood pressure with mortality and cardiovascular outcomes. JAMA 2019; 322:409–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation 2005; 111:697–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, et al. 2007 ESH-ESC practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: ESH-ESC Task Force on the Management of Arterial Hypertension. J Hypertens 2007; 25:1751–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment Of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal R, Kolkhof P, Bakris G, Bauersachs J, Haller H, Wada T, et al. Steroidal and nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in cardiorenal medicine. Eur Heart J 2021; 42:152–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pitt B, Kober L, Ponikowski P, Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, Krum H, et al. Safety and tolerability of the novel nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist BAY 94-8862 in patients with chronic heart failure and mild or moderate chronic kidney disease: a randomized, double-blind trial. Eur Heart J 2013; 34:2453–2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georgianos PI, Agarwal R. Ambulatory blood pressure reduction with SGLT-2 inhibitors: dose–response meta-analysis and comparative evaluation with low-dose hydrochlorothiazide. Diabetes Care 2019; 42:693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossing P, Anker SD, Filippatos G, Pitt B, Ruilope L, Birkenfeld AL, et al. Finerenone in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes by sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor treatment: the FIDELITY analysis. Diabetes Care 2022; 45:2991–2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal R, Filippatos G, Pitt B, Anker SD, Rossing P, Joseph A, et al. Cardiovascular and kidney outcomes with finerenone in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: the FIDELITY pooled analysis. Eur Heart J 2022; 43:474–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitt B, Filippatos G, Gheorghiade M, Kober L, Krum H, Ponikowski P, et al. Rationale and design of ARTS: a randomized, double-blind study of BAY 94-8862 in patients with chronic heart failure and mild or moderate chronic kidney disease. Eur J Heart Fail 2012; 14:668–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amazit L, Le Billan F, Kolkhof P, Lamribet K, Viengchareun S, Fay MR, et al. Finerenone impedes aldosterone-dependent nuclear import of the mineralocorticoid receptor and prevents genomic recruitment of steroid receptor coactivator-1. J Biol Chem 2015; 290:21876–21889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weinberger MH, Roniker B, Krause SL, Weiss RJ. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in mild-to-moderate hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2002; 15:709–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, Neaton J, Martinez F, Roniker B, et al. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:1309–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, van Veldhuisen DJ, Swedberg K, Shi H, et al. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolkhof P, Jaisser F, Kim SY, Filippatos G, Nowack C, Pitt B. Steroidal and novel nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in heart failure and cardiorenal diseases: comparison at bench and bedside. Handb Exp Pharmacolo 2017; 243:271–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.