Abstract

Aims

Cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias can be severe presentations in patients with inherited defects of mitochondrial long-chain fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO). The pathophysiological mechanisms that underlie these cardiac abnormalities remain largely unknown. We investigated the molecular adaptations to a FAO deficiency in the heart using the long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD) knockout (KO) mouse model.

Methods and results

We observed enrichment of amino acid metabolic pathways and of ATF4 target genes among the upregulated genes in the LCAD KO heart transcriptome. We also found a prominent activation of the eIF2α/ATF4 axis at the protein level that was independent of the feeding status, in addition to a reduction of cardiac protein synthesis during a short period of food withdrawal. These findings are consistent with an activation of the integrated stress response (ISR) in the LCAD KO mouse heart. Notably, charging of several transfer RNAs (tRNAs), such as tRNAGln was decreased in LCAD KO hearts, reflecting a reduced availability of cardiac amino acids, in particular, glutamine. We replicated the activation of the ISR in the hearts of mice with muscle-specific deletion of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2.

Conclusions

Our results show that perturbations in amino acid metabolism caused by long-chain FAO deficiency impact cardiac metabolic signalling, in particular the ISR. These results may serve as a foundation for investigating the role of the ISR in the cardiac pathology associated with long-chain FAO defects.

Translational Perspective: The heart relies mainly on mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) for its high energy requirements. The heart disease observed in patients with a genetic defect in this pathway highlights the importance of FAO for cardiac health. We show that the consequences of a FAO defect extend beyond cardiac energy homeostasis and include amino acid metabolism and associated signalling pathways such as the integrated stress response.

Keywords: Fatty acid oxidation, LCAD, tRNA, Amino acids, Hypertrophy

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

See the editorial comment for this article ‘The integrated stress response to the rescue of the starved heart’, by Jan Dudek et al ., https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvac141.

Translational perspective.

The heart relies mainly on mitochondrial fatty acid b-oxidation (FAO) for its high energy requirements. The heart disease observed in patients with a genetic defect in this pathway highlights the importance of FAO for cardiac health. We show that the consequences of a FAO defect extend beyond cardiac energy homeostasis and include amino acid metabolism and associated signaling pathways such as the integrated stress response.

1. Introduction

An adult healthy heart is particularly reliant on mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) for its energy needs when compared to other organs.1 A recent comprehensive study reported that fatty acids provide around 85% of the myocardial ATP needed in healthy human subjects.2 Pathological hypertrophic cardiac growth is associated with a reprogramming of heart metabolism, characterized by decreased fatty acid metabolism and increased reliance on glucose metabolism. This cardiac metabolic remodeling has been described in animal models1,3–6 and human patients.2,7–9 The importance of FAO in cardiac health is supported by the observation that patients with an inherited disorder of FAO may develop hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias.10–12 Although altered myocardial fatty acid metabolism has been documented in patients with FAO defects,13,14 the metabolic and transcriptional adaptations that underlie the cardiac pathophysiology remain largely unknown.

Mouse models are useful to investigate the effects of FAO deficiency on cardiac metabolism and function. The long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD) knockout (KO) (Acadl–/–) mouse serves as a good model for human long-chain FAO disorders such as very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (VLCAD) and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2 (CPT2) deficiency. The LCAD KO mouse recapitulates prominent symptoms of VLCAD deficiency including fasting-induced hypoketotic hypoglycemia and cardiac hypertrophy.15–19 Previous studies have revealed a fasting-induced cardiac dysfunction in LCAD KO mice, characterized by an impaired left ventricular performance including an increase in end-systolic volume, and reduced ejection fraction, stroke volume, cardiac output, peak ejection rate, and peak late filling rate.15,20 At the metabolite level, we previously observed systemic changes in amino acid metabolism causing a shortage in the supply of gluconeogenic precursors16 and an unmet anaplerotic need in the heart of fasted LCAD KO mice.20 These changes are characterized by increased cardiac glucose uptake and oxidation, a suppressed glucose-alanine cycle, decreased circulating levels of gluconeogenic amino acids, decreased levels of cardiac TCA cycle intermediates, and impaired protein mobilization.15,16,20 The molecular responses of the FAO-deficient heart to these metabolic challenges are unknown but could shed some light on the mechanisms underlying the associated cardiac pathology.

The integrated stress response (ISR) is a well-conserved pathway that is regulated by phosphorylation of the alpha subunit of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 complex (eIF2α).21,22 Different stressors are sensed by four specialized eIF2α kinases [HRI, PKR, PERK, and general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2)] leading to phosphorylation of S51 on eIF2α.23 Phosphorylated eIF2α blocks the eIF2’s guanine nucleotide exchange factor eIF2B and results in a reduction of protein synthesis. As part of the cellular response specific to amino acid depletion, the ISR promotes the selective translation of a pool of mRNAs that contain short inhibitory upstream open reading frames in their 5′ UTR, including activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4).24 ATF4 target genes encode, among others, amino acid biosynthesis enzymes and amino acid transporters.25,26

Here, we used transcriptome analysis to identify molecular changes in the heart in response to a long-chain FAO deficiency. To identify early and late events, we also characterized the progression of changes in metabolite levels and metabolic signalling during an overnight food withdrawal. We identified activation of the ISR in the FAO-deficient heart that is largely independent of the feeding status.

2. Methods

2.1 Animal experiments

LCAD KO (Acadl–/–) mice17 on a pure C57BL/6 background were maintained on a normal chow diet (PicoLab Rodent Diet 20, LabDiet). The Acadl allele was genotyped using an SNP-based assay27 and wild-type (WT) animals were true littermates. Cardiac and skeletal muscle CPT2-deficient mice (Cpt2M–/–) were generated as previously described.28 Briefly, a loxP flanked specific sequence of the Cpt2M–/– gene was excised by the Cre recombinase under the control of the muscle creatine kinase promoter. Littermates lacking Cre enzyme expression were used as controls. Cpt2M–/– mice and controls were maintained on a custom-made control diet (Envigo TD 94045).29 Mice were housed in pathogen-free rooms with a 12 h light/dark cycle. All animal experiments were approved by the IACUC of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (# IACUC-2014-0100) and the Purdue University IACUC (assurance #A3231-01) and comply with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, 8th edition, 2011). Mice were euthanized by exposure to CO2 except for mice from the time course cohort (Figure 3 and Supplementary material online, Figure S2), which were euthanized using pentobarbital anaesthesia (intraperitoneal 150 mg/kg in 0.9% NaCl) followed by exsanguination for the blood collection. Details on the different mouse cohorts are described in the supplemental methods.

Figure 3.

Metabolic alterations in response to food availability in plasma and heart of WT and LCAD KO mice. (A–H) Effect of food availability on plasma metabolite levels at different time points in WT (n = 6 per time point) and LCAD KO (n = 5–6 per time point) mice. Time point 1: 6 p.m. (random fed), 2: 10 p.m. (4 h after food withdrawal), 3: 2 a.m. (8 h after food withdrawal), 4: 6 a.m. (12 h after food withdrawal), 5: 10 a.m. (4 h of refeeding after 12 h of food withdrawal), 6: 10 a.m. (random fed). (A) C14:1-carnitine, (B) C16-carnitine, (C) carnitine, (D) C2-carnitine, (E) C4OH-carnitine, (F) glucose, (G) alanine, (H) glutamine. (I) Representative immunoblots of ISR markers in WT and LCAD KO hearts at different time points of the food withdrawal time course study (n = 4 per genotype and time point) (J) Band densitometry was quantified relative to α-tub, or the non-phosphorylated form of the protein. Individual values, the mean, and the standard deviation are represented. The result of the two-way ANOVA test is displayed within the graphs. G: ‘Genotype’. T: ‘Time point’. I: ‘Interaction’. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001

2.2 RNA-seq, differential gene expression, pathway enrichment

Details on the RNA-seq methods are described in the supplemental materials. The raw data and the count matrix for all genes have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE176553.

2.3 Metabolite analysis

Plasma acylcarnitines and amino acids were measured and analyzed by liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry on an Agilent 6460 Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer by the Mount Sinai Biochemical Genetic Testing Lab (now Sema4), as previously described.30–32

2.4 Transfer RNA charging

Charging of transfer RNA (tRNA) was measured essentially as described.33 A detailed protocol is presented in supplemental methods.

2.5 2H labelling of protein-bound alanine to determine fractional protein synthesis

2H enrichment of protein-bound alanine was determined on its methyl-8 derivative, as previously described.34–37

2.6 Statistics

Differences were evaluated using a two-sided unpaired Student t test, a non-parametric Mann-Whitney test, or a two-way analysis of variance, as indicated in figure legends. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001. GraphPad Prism 9 was used to compute statistical values.

3. Results

3.1 Transcriptional activation of amino acid metabolic pathways and ATF4 target genes in the heart of LCAD KO mice

To gain more insight into transcriptional adaptations of the heart to long-chain FAO deficiency, we performed RNA-sequencing analysis of WT and LCAD KO mouse heart samples collected after overnight food withdrawal and determined differentially expressed genes (DEGs). With an adjusted p value cutoff of 0.05 and a fold-change cutoff of 1.5, we obtained 2334 DEGs (1032 up and 1302 down) demonstrating a large impact of FAO deficiency on the mouse heart (see Supplementary material online, Table S1A). Pathway enrichment analysis of the DEGs revealed up-regulation of genes involved in ‘rRNA metabolic process’, ‘carboxylic acid metabolic process, and ‘Hypertrophy Model’ (adj P < 0.05), among other pathways (Figure 1A and Supplementary material online, Table S1B). In line with our previous work,16,20 genes belonging to ‘cellular amino acid metabolic process’ and ‘amino acid metabolism’ pathways were also up-regulated in the DEGs (adj P < 0.05) (Figure 1A and Supplementary material online, Table S1B). A close inspection of the up-regulated genes belonging to these pathways revealed many cytosolic aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (Aars, Cars, Eprs, Gars, Iars, Lars, Mars1, Nars, Sars, Tars, and Yars), most genes involved in serine and glycine biosynthesis (Mthfd1, Phgdh, Psat1, and Shmt1), most genes involved in proline biosynthesis (Aldh18a1, Prodh, and Pycr1) as well as genes involved in asparagine, cysteine, glutamine, glutathione and polyamine biosynthesis (Asns, Cth, Gclc, Gclm, Glul, Odc1, and Srm). We identified other enriched pathways that contain both up-regulated and down-regulated genes, such as ‘phosphorylation’ and ‘skeletal muscle cell differentiation’, as well as pathways that were enriched in down-regulated genes, such as ‘Response to interferon-beta’ (Figure 1A and Supplementary material online, Table S1B). In summary, we uncovered a transcriptional signature in LCAD KO hearts characterized by a striking up-regulation of genes involved in tRNA aminoacylation and amino acid biosynthesis.

Figure 1.

Pathway enrichment and transcription factor binding motif enrichment analysis of LCAD KO heart transcriptomic data. (A) Pathway enrichment analysis of the DEGs between hearts from WT and LCAD KO mice according to GO (BP), KEGG, Wiki, and Reactome databases. Genes that were either up- or down-regulated (logFC >0.58, adjP < 0.05) were queried as two separated gene clusters. Network node annotations are the pathway terms found significantly enriched at adj P < 0.05, with a size of the node reflecting term significance, with the bigger nodes the more significant ones. The node colour shows the proportion of genes from each cluster that are associated with the term. Grey nodes indicate genes associated to a term are from both the up- and down clusters and thus common to both gene lists. Nodes coloured shades of orange or blue indicate genes that associate to a term (at least >60%) are more specific to either the up- or down-regulated geneset, respectively. Edges represent the ClueGO kappa score, which defines term-term interrelations based on shared genes between the terms. Terms are grouped at default kappa > 0.4) with edge thickness reflecting a greater kappa value. The full results are in table S1B. (B) iRegulon transcription factor analysis was performed on the up-regulated DEGs using their putative regulatory regions 10 kb centred around the transcription start site. The top-ranked enriched motif had a significant normalized enrichment score (NES) of 7.221 and its sequence is shown in the figure. The transcription factor associated with the motif was ATF4. Fifty-two ATF4-target genes were found on the up-regulated geneset, a subset of those (red nodes) genes are shown according to the biological pathways they were found associated with in panel A. Full results are in Table S1C.

We next focused on transcriptional regulators that could explain the observed changes in gene expression and performed cis-regulatory sequence analysis. We found that the LCAD KO heart transcriptional signature was enriched for genes containing binding motifs that mapped to the transcription factor ATF4 (Figure 1B and Supplementary material online, Table S1C). ATF4 is a key mediator of the ISR, a well-conserved homeostatic response that reprograms translation in response to nutrient stress.21,23,38,39 Asparagine synthetase (Asns), the most upregulated gene in LCAD KO hearts, is a canonical ATF4 target gene.40 We found 51 additional ATF4 target genes in the up-regulated geneset (Figure 1B and Supplementary material online, Table S1C). These results suggest that ATF4 is a key mediator of the transcriptional signature of hearts from LCAD KO mice after food withdrawal.

3.2 Activation of the integrated stress response in the heart of LCAD KO mice

Next, we studied the ISR at the protein level using immunoblot in heart samples from LCAD KO mice isolated after overnight food withdrawal. When compared to controls, LCAD KO mice had increased cardiac protein levels of phosphorylated eIF2α (S51), ATF4, and ASNS (Figure 2A), which is consistent with activation of the ISR. We also found a decreased Thr37/46 phosphorylation of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) in LCAD KO hearts compared with WT hearts, which appears to be mainly mediated by an increase in total 4E-BP1 (Figure 2A). 4E-BP1 inhibits protein translation by preventing eIF4E to bind cap structures on mRNAs.41 4E-BP1 (Eif4ebp1) is also an ATF4 target gene26 and, consistently, its expression was up-regulated in LCAD KO hearts (see Supplementary material online, Table S1A). We also found that the expression of the autophagy markers p62 and LC3B-II was increased in LCAD KO hearts compared with WT hearts (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1A). The cardiac increase of LC3B-II protein was validated in an independent set of WT and LCAD KO samples (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1B). Thus, LCAD deficiency leads to nutrient stress and, as a consequence, activation of the ISR via the eIF2α/ATF4 axis.

Figure 2.

Activation of the integrated stress response in the heart of LCAD KO mice. (A) Immunoblot of ISR markers p-eIF2α (S51), eIF2α, ATF4, ASNS, P-4E-BP1 (T37/46), 4E-BP1. Protein levels were quantified relative to α-tubulin (α-tub), or their non-phosphorylated form (as indicated on the x-axis label). (B) Protein synthesis rate (FSR: fractional synthesis rate, in %) was determined in the hearts of WT (n = 4) and LCAD KO (n = 7) mice after the injection of 2H2O and 8 h of food withdrawal, by measuring the 2H-labelling of protein-bound alanine. ND: not detected. Individual values, the mean and the standard deviation are graphed. Statistical significance was tested using an unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

We measured protein synthesis rates in WT and LCAD KO hearts by the 2H2O method. WT hearts showed detectable protein synthesis during 8 h of food withdrawal starting at the onset of the active period (dark cycle). In contrast, protein synthesis was not detectable in any of the LCAD KO heart samples (Figure 2B). No differences in protein synthesis were detected during the light cycle (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1C). Thus decreased nutrient availability can lead to a pronounced reduction in protein synthesis in the heart.

We next assessed whether the activation of the ISR in heart of the LCAD KO mouse was a tissue-specific phenomenon. For this, we evaluated if the ISR was activated in the liver and soleus muscle, which are two other tissues with prominent metabolic changes in the LCAD KO mouse. In the liver of LCAD KO mice, protein synthesis was increased (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1D) and the ISR was not activated (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1E). Moreover, ASNS protein levels were not changed in the soleus muscle of LCAD KO mice suggesting no activation of the ISR (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1F). Thus, our data suggest that the activation of the ISR in the LCAD KO mouse heart may be a tissue-specific response.

3.3 Metabolic alterations in response to food availability in LCAD KO mice

Overnight food withdrawal leads to significant changes in mouse metabolism and pronounced differences between WT and LCAD KO mice. In order to identify early and late changes in response to food withdrawal in the LCAD KO mouse model, we collected plasma and heart samples from WT and LCAD KO mice every 4 h during a 12 h food withdrawal period. Food was withdrawn just before the dark phase at 6 p.m. and a random fed sample was collected (time point 1). During food withdrawal, samples were collected at 10 p.m., 2 a.m., and 6 a.m. (time points 2, 3, and 4). At 6 a.m. mice were refed for 4 h with sample collection at 10 a.m. (time point 5). Additionally, we collected samples from animals that were randomly fed and sacrificed at 10 a.m. (time point 6) (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2A). Analysis of plasma metabolites (see Supplementary material online, Table S2A and S2B) showed that many of the established differences in circulating metabolites between fasted LCAD KO and WT mice were already evident 4 h after food withdrawal including a peak in C14:1-carnitine accumulation (Figure 3A), a pronounced C16-carnitine accumulation (Figure 3B), free carnitine and acetylcarnitine (C2-carnitine) deficiency (Figure 3C and D), hypoketosis (Figure 3E, assessed by C4OH-carnitine levels42), and hypoglycemia (Figure 3F). Some of the differences between LCAD KO and WT animals became more pronounced with time (acetylcarnitine deficiency), whereas others stabilized (hypoglycemia) (Figure 3D, 3F). A period of 4 h of refeeding normalized blood glucose (Figure 3F), but free carnitine and acetylcarnitine concentration remained low (Figure 3C and D). Accumulation of long-chain acylcarnitines in plasma was evident at every time point during fasting but decreased sharply upon refeeding (Figure 3A and B, and Supplementary material online, Table S2A).

Fasting led to a reduction in the plasma level of gluconeogenic amino acids such as alanine and glutamine, which was most pronounced after 8 h of fasting but also present 4 h after food withdrawal (Figure 3G and H). Reduced levels of alanine and glutamine were also noted in the fed state (time point 6) (Figure 3G and H). A similar profile was found for other amino acids such as glutamate and aspartate (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2A and Table S2B). Plasma levels of proline, serine, and glycine increased considerably after refeeding in LCAD KO mice (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2A). In contrast, the contribution of branched-chain amino acids to the total pool of amino acids increased 4 h after food withdrawal, remained elevated during the period of food withdrawal, and returned to basal levels after refeeding (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2A). Together, these data show that the metabolic phenotype of LCAD KO mice is characterized by hypoketotic hypoglycemia, increased levels of C14:1-carnitine, secondary carnitine deficiency, and changes in amino acid metabolism, which is present early after food withdrawal.

The same samples were used to study early and late events in metabolic signalling in the heart of LCAD KO mice. We found that the levels of phospho-eIF2α (S51), ATF4, and ASNS, indicative of activation of the ISR, were increased at all tested time points in LCAD KO hearts compared with WT hearts, including fed samples (Figure 3I and J). ATF4 protein levels reached their peak after refeeding (Figure 3I and J). Phosphorylated 4E-BP1 (T37/46) progressively decreased with time in WT and LCAD KO hearts and increased after refeeding in both genotypes (Figure 3I and J), in line with mTORC1 activation after refeeding.26,43 LC3B-II was increased in LCAD KO hearts at time points 1 to 4, then decreased upon refeeding (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2B), consistent with an inhibition of autophagy after feeding. Levels of p62 were increased in the heart of refed LCAD KO mice. However, no difference was observed after the food was withdrawn (time points 2, 3, and 4) (Figure S2B). These results indicate that the activity of the ISR is higher in LCAD KO hearts when compared to WT hearts irrespective of the feeding status of the mice.

3.4 Accumulation of uncharged tRNAs in the LCAD KO mouse heart

Four different kinases (GCN2, PERK, HRI, and PKR) sense different types of nutrient stress and converge on eIF2α phosphorylation to initiate the ISR.23 We did not find any signs of PERK (encoded by Eif2ak3) activation, an eIF2α kinase that senses protein folding alterations in the endoplasmic reticulum.25,44 Protein levels of ATF6, phosphorylated PERK (Thr980), or the ER chaperone BiP, which is also referred to as GRP78 or HSPA5, did not change in LCAD KO hearts compared with WT hearts (see Supplementary material online, Figure S3A). Moreover, we did not find any change in XBP1 splicing events45 in LCAD KO hearts compared with WT hearts (see Supplementary material online, Figure S3B). Hence, we found no evidence that ER stress acts as the activator of the ISR in LCAD KO hearts.

We have reported here and in previous studies changes in amino acid metabolism in the LCAD KO mouse.16,20,30 Given the decreased levels of free amino acids in plasma and tissues including the heart, we hypothesized that the most likely mediator of eIF2α phosphorylation in LCAD KO hearts is the GCN2 kinase because this kinase is known to be activated by reduced amino acid availability.33,46–50 GCN2 is autophosphorylated in the presence of tRNAs that are not bound to their cognate amino acid (i.e. uncharged tRNAs).48,51 Uncharged tRNAs may accumulate as a consequence of decreased tRNA aminoacylation due to reduced availability of free amino acids.33 We were, however, unable to detect phosphorylated GCN2 in any of the mouse heart samples. Although the anti-pGCN2 (T899) antibody (Abcam, ab75836; not shown) is validated and highly referenced, it has not been demonstrated to work in mouse heart extracts. Thus, the role of GCN2 kinase in the activation of the ISR in LCAD KO hearts remains speculative.

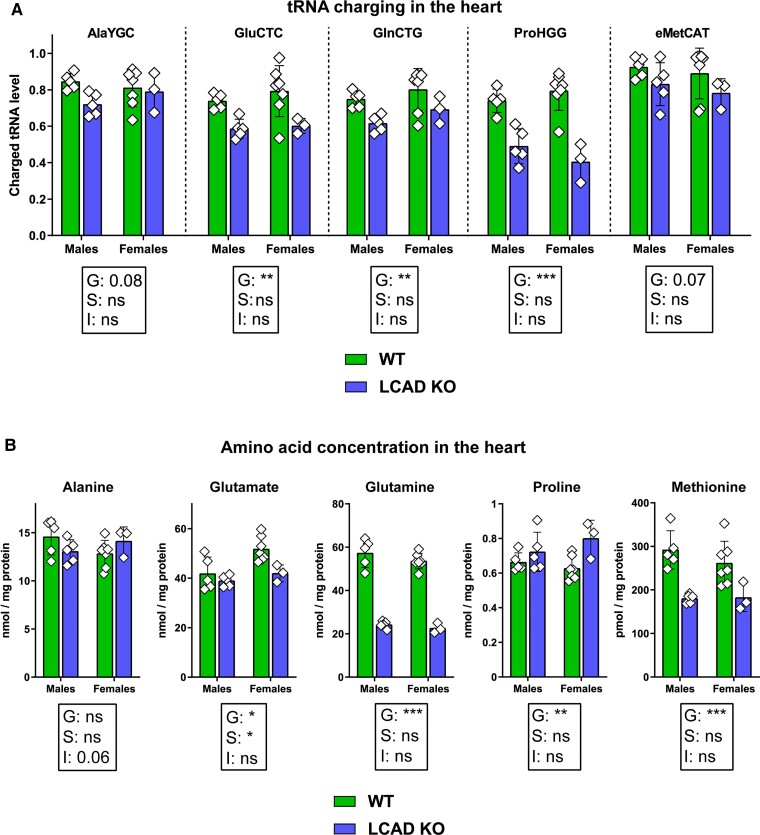

In order to assess the potential activators of GCN2 instead, we measured tRNA charging in heart samples from WT and LCAD KO hearts after a short period (4 h) of food withdrawal.33 We found a significant reduction in the charging of tRNAGlu, tRNAGln, tRNAPro, tRNAArg, tRNALeu, and tRNAVal in LCAD KO hearts when compared to WT hearts (Figure 4A and Supplementary material online, Figure S4A). We measured amino acid concentrations in the same heart samples and found decreased levels of several amino acids including glutamate, glutamine, methionine, histidine, and citrulline in LCAD KO hearts when compared to WT hearts (Figure 4B and Supplementary material online, Figure S4B, and Table S3). The decreased levels of glutamate, glutamine, and methionine paralleled the decrease in charging of their cognate tRNA (Figure 4A and 4B). The concentration of several other amino acids such as proline, glycine, and lysine increased in LCAD KO hearts (Figure 4B and Supplementary material online, Figure S4B, and Table S3). Remarkably, tRNAPro was decreased in these samples (Figure 4A). These results show that, after a short period of food withdrawal, a defect in long-chain FAO leads to the uncharging of several tRNAs in the heart, which may be due to reduced amino acid availability.

Figure 4.

tRNA charging and amino acid concentrations in mouse heart after a short period of food withdrawal. (A) tRNA charging of the following isodecoder groups was measured in mouse hearts using specific primers: AlaYGC, GluCTC, GlnCTG, ProHGG, and eMetCAT. The last three letters denote an anticodon or a group of anticodons targeted. Y: C or T; H: A, C or T. (B) Amino acid concentrations (in pmol/mg protein or nmol/mg protein) were measured in mouse hearts. N = 3-7 biological replicates per genotype (WT and LCAD KO) and sex (males and females). Individual values, the mean, and the standard deviation are represented. The result of the two-way ANOVA test is displayed within the graphs. G: ‘Genotype’. S: ‘Sex’. I: ‘Interaction’. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001

3.5 Activation of the ISR in CPT2-deficient mouse hearts

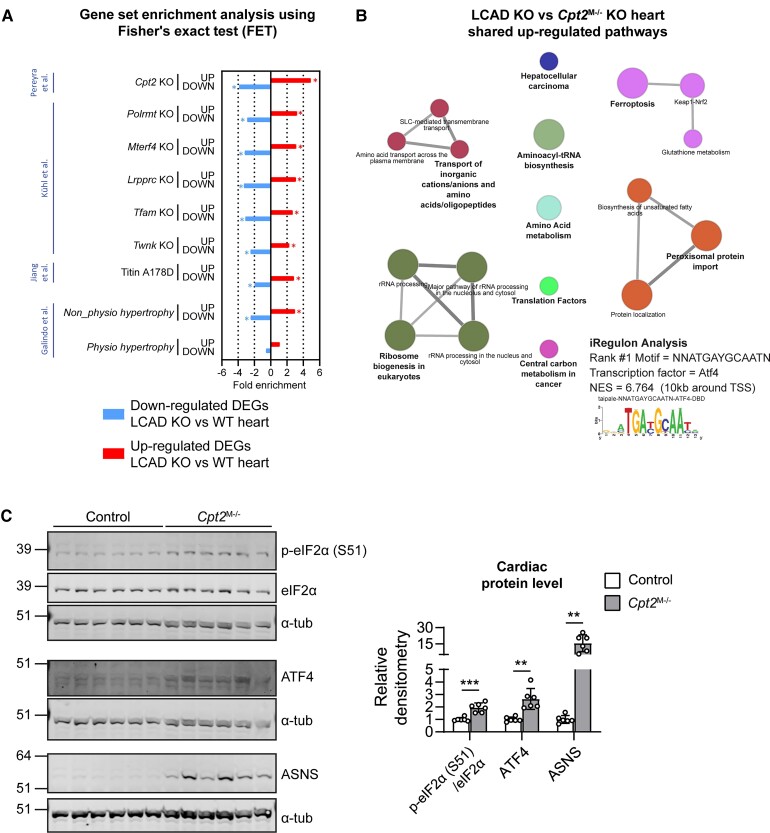

We next investigated if the activation of the ISR could be observed in other models of cardiac hypertrophy. We collected the following cardiac transcriptional signatures; a cardiac and skeletal muscle-specific CPT2 KO (Cpt2M–/–) mouse,28 five KO mouse models with dysfunction of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS),52 mice carrying the titin p.A178D missense variant,53 and, finally, mouse models of physiological (exercise) and pathological (isoproterenol-induced) cardiac hypertrophy.54 We compared these to the transcriptional signature of LCAD KO hearts (see Supplementary material online, Table S4A). The highest and most significant overlap was between the up- and down-regulated DEGs from the two models with a defect in long-chain FAO, i.e. the LCAD and CPT2 KO mouse models (Figure 5A, Supplementary material online, Figure S5A, Table S4A). Of note, the Cpt2M–/– mouse model displays more severe and progressive cardiomyopathy when compared to the LCAD KO mouse model.15,28 Importantly, the intersection of upregulated genes from the hearts of these two FAO-deficient models was enriched for key terms such as ‘Amino-tRNA biosynthesis’, ‘Amino acid metabolism’, and ‘Amino acid transport across the plasma membrane’ (Figure 5B and Supplementary material online, Table S4B) and for genes containing binding motifs that mapped to the transcription factor ATF4 (Figure 5B and Supplementary material online, Table S4C). These results suggest that activation of ATF4 and disturbances in amino acid metabolism are common adaptations of the long-chain FAO deficient heart.

Figure 5.

Activation of the ISR in CPT2-deficient hearts. (A) Results of the enrichment analysis using the Fisher’s exact test with genes either up- or down-regulated in LCAD KO hearts and 9 transcriptional signatures of mouse models with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Values represent the fold enrichment and significance is indicated as * (adj P < 0.001). The complete results are in Table S4A. (B) Pathway enrichment analysis of the shared up-regulated DEGs between hearts from WT and LCAD KO mice, and hearts from WT and Cpt2M–/– mice,28 according to KEGG, Wiki, and Reactome databases. Genes that were up-regulated (adjP < 0.05) from the full output of Pereyra et al. were queried to compare them with the LCAD KO heart transcriptional signature. A full table of results is in Table S4B. Network node annotations are the pathway terms found significantly enriched at adj P < 0.05, with a size of node reflecting term significance, with the bigger nodes the more significant ones. Edges represent the ClueGO kappa score, which defines term-term interrelations based on shared genes between the terms. Terms are grouped at default kappa >0.4, with edge thickness reflecting a greater kappa value. iRegulon transcription factor analysis was performed on the shared up-regulated DEGs using their putative regulatory regions 10 kb centred around the transcription start site. The top-ranked enriched motif had a significant normalized enrichment score (NES) of 6.764 and its sequence is shown in the figure. The transcription factor associated with the motif was ATF4. The full results are in Table S4C. (C) Immunoblots of the ISR markers phosphorylated eIF2α (p-eIF2α) at S51, ATF4, and ASNS in the hearts of control and CPT2-deficient (Cpt2M–/–) mice (n = 6) are shown. Band densitometry was quantified relative to α-tub, or the non-phosphorylated form of the protein, as indicated. Individual values, the average, and the standard deviation are graphed. The result of the unpaired t test with Welch’s correction is displayed within the graphs. ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

Of the other cardiac transcriptional signatures, the most significant overlap was with the metabolic cardiomyopathies, i.e. the mouse models with OXPHOS dysfunction. There was also some overlap between the up- and down-regulated DEGs of LCAD KO hearts and those from the titin and the pathological hypertrophy models (Figure 5A and Supplementary material online, Table S4A). Specifically, the intersection of the upregulated genes in the metabolic cardiomyopathy models all contained Asns and was enriched for genes containing binding motifs that mapped to the transcription factor ATF4 (see Supplementary material online, Table S4D). This indicates that activation of the ISR may be a commonality in cardiac hypertrophy caused by metabolic derangements.

We then explored whether the activation of the ISR was also present at the protein level in the CPT2-deficient hearts. We observed increased levels of phosphorylated eIF2α (S51), ATF4, and ASNS in Cpt2M–/– hearts (Figure 5C), similar to what we observed in the LCAD KO hearts. Together, these results indicate that the cardiac activation of the ISR is a conserved mechanism in long-chain FAO defects.

To provide additional evidence that the activation of the ISR in LCAD KO hearts may be driven by changes in amino acid levels, we compared the transcriptional signature of LCAD KO hearts to a signature of the adult brain of Tie2Cre; Slc7a5fl/fl mice.55 These mice have a deletion of the amino acid transporter Slc7a5 from the endothelial cells of the blood–brain barrier leading to an atypical brain amino acid profile. There was a significant overlap between the upregulated genes of both models with the intersection containing Atf4, Asns, and several aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and other genes involved in amino acid metabolism (see Supplementary material online, Table S4A). These data further support the notion that changes in amino acid levels may play an important role in the activation of the ISR in LCAD KO hearts.

4. Discussion

In this study, we assessed the effects of nutrient availability and a long-chain FAO defect on mRNA expression and metabolic signalling in the heart. We demonstrate that the nutrient stress caused by LCAD deficiency activates the ISR and impacts on cardiac protein synthesis and amino acid metabolism. We furthermore show that this defect in long-chain FAO can lead to uncharging of several tRNAs, which is likely mediated by a reduction in the intracellular free amino acid levels reported in LCAD KO hearts and reproduced in this study.16,30 The observation that the activation of the ISR leads to a compensatory transcriptional upregulation of the tRNA aminoacylation pathway in the LCAD KO and the CPT2 KO hearts further supports these findings. We suggest that tRNA uncharging may represent an adaptive or possible pathophysiological mechanism in the FAO deficient heart. This is not only the first report on tRNA charging in the mouse heart, this is also the first time that uncharging of tRNAs is demonstrated in a disease model.

Activation of the ISR attenuates global mRNA translation to conserve amino acids and energy.23 Thus the observed activation of the ISR in LCAD KO hearts may represent one adaptive response to overcome the nutritional stress imposed by the long-chain FAO defect. Importantly, the activation of the ISR was largely independent of feeding status, which may be explained by the fact that the heart typically relies on FAO for the majority of its ATP production. Therefore our findings may be relevant for patients with long-chain FAO defects who typically avoid fasting and are under dietary management to prevent a metabolic crisis.

Our RNA-seq analysis showed that the ATF4 transcription factor binding motif is enriched in the DEGs of LCAD KO hearts. ISR and ATF4 activation is a common finding in mitochondrial dysfunction caused by different mitochondrial stressors, such as cardiac-specific mitochondrial tRNA synthetase deficiency,56 mtDNA gene expression defects,52,57 electron transport chain inhibition,58 and mitochondrial translation inhibition, mitochondrial membrane potential disruption, and mitochondrial protein import inhibition,39 but has not been studied in models of FAO deficiency. Our pathway enrichment analysis using the shared up-regulated genes from the LCAD KO heart and muscle-specific CPT2-deficient mice28 indicated induction of amino acid metabolism pathways and activation of the transcription factor ATF4, which we subsequently validated at the protein level. This suggests that long-chain FAO defects impact on cardiac amino acid metabolism and activate the ISR. We speculate that the transcriptional and metabolic adaptations identified in the LCAD KO hearts are largely tissue-specific. This is based on the comparison with the CPT2 KO mouse model, but also the OXPHOS-deficient mouse models,52 which are all heart and skeletal muscle-specific. Moreover, the activation of the ISR is also observed in the fed state, in which systemic consequences of an FAO defect are generally absent, and was not present in the liver or soleus muscle, which are other tissues with prominent metabolic changes in the LCAD KO mice. This aspect deserves further investigation, but cardiac-specific LCAD KO mice are not available yet.

eIF2α can be phosphorylated by PERK, GCN2, PKR, and HRI kinases, which are activated by unfolded proteins in the ER,21,44 amino acid deficiency,21,25,46–48,50 viral infection and haeme deficiency,23 respectively. Activation of the ISR after a short period of food withdrawal (only 4 h) was associated with decreased availability of many amino acids and the uncharging of certain tRNAs in LCAD KO hearts. Activation of the ISR in LCAD KO hearts was also accompanied by a reduction in protein synthesis. Previously, decreased amino acid availability was demonstrated to reduce the charging of tRNAGlnin vitro.33 Impaired amino acid transport at the blood-brain barrier leads to an atypical brain amino acid profile and activation of the ISR. Notably, the DEGs of LCAD KO hearts overlapped significantly with the DEGs in the brain of this mouse model.55 Thus, amino acid limitation-associated uncharging of tRNAs, and in particular tRNAGln, may cause the induction of the ISR in LCAD KO hearts via GCN2 kinase activation. Other studies have confirmed the role of GCN2 kinase in modulating homeostatic responses in the heart.59,60 As we could not unequivocally prove that GCN2 is activated in LCAD KO hearts due to poor performance of the tested antibodies in heart samples, we cannot completely exclude a contribution of other eIF2α kinases to the ISR activation in this model. These include HRI and PKR, which have been recently linked to the sensing of mitochondrial-derived stress.61–64 Genetic experiments with mouse models deficient for each of these kinases or pharmacological modulation of eIF2α phosphorylation should help to determine the mechanism of eIF2α activation in long-chain FAO deficiency and whether this ISR activation is a protective or a maladaptive response of the FAO-deficient heart.

We note that the decrease in charging of tRNAGln was less pronounced than the decrease in cardiac glutamine levels. Since the expression of Qars was unchanged in LCAD KO hearts, we suggest that this may be explained by a relatively high affinity of the glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase for glutamine. In tissues such as the liver, skeletal muscle, and heart, glutamine is the most abundant amino acid and its concentration is high. Cardiac glutamine concentrations can be estimated at ∼3.6 mmol/L (based on16). Although unknown for human glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase, the orthologues from Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have Km values that are at least 14-fold lower than the cardiac glutamine concentration consistent with a relatively high affinity for glutamine.65–67

The activation of the ISR in the heart of LCAD KO mice appears largely independent of the feeding status, which may suggest that it plays a role in the development of the observed cardiac hypertrophy. LCAD KO mice display non-progressive cardiac hypertrophy,15 but cardiac dysfunction only arises upon food withdrawal.15,20 Indeed, some of the characteristic features of the ISR are associated with an adaptive response that may explain cardiac hypertrophy in LCAD KO mice. For example, during the ISR there is a redirection of glucose metabolic flux towards serine biosynthesis, which provides precursors for one-carbon metabolism, phospholipids, and glutathione synthesis, as a protective mechanism for managing mitochondrial bioenergetic stress.57,68–70 In a recent metabolite profiling of hearts of overnight fasted LCAD KO mice, we found increased levels of asparagine, serine, glycine, pyrimidine nucleotides, and phospholipids30 consistent with the ATF4-mediated induction of the serine biosynthetic genes Psat1 (phosphoserine aminotransferase) and Phgdh (phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase), and Asns. Here, we studied amino acid metabolism after a shorter period of food withdrawal, which is likely more translatable to human FAO disorders, and describe similarly profound changes in amino acid metabolism in LCAD KO hearts, including increased levels of proline, glycine, and lysine, and decreased levels of glutamine and glutamate. Based on the recent discovery of a biosynthetic arm downstream of ATF4 activation,26 we speculate that the activation of the ISR and ATF4 in LCAD KO hearts may contribute to cardiac hypertrophy. Further investigations manipulating these metabolic adaptations in LCAD KO hearts are required to understand their contribution to cardiac hypertrophy and, ultimately, to nutrient stress-induced cardiac dysfunction in FAO defects.

In conclusion, we describe the progression of metabolic alterations in plasma and heart of LCAD KO mice during overnight fasting, showing that many of the metabolic changes start soon after food withdrawal. In particular, there is sustained activation of the ISR in LCAD KO hearts. We also report the uncharging of certain tRNAs in the heart of LCAD KO mice after 4 h of food withdrawal. Collectively, these findings exemplify how defects in FAO remodel cardiac metabolism impacting glucose and amino acid metabolism. The results obtained here provide a basis for future investigations to assess the impact of modulation of the ISR on cardiac function in FAO deficiencies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Tetyana Dodatko for excellent technical assistance. We acknowledge the help of the shared resource facilities at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (Colony Management, Genomics Core, and the Comparative Pathology Laboratory).

Contributor Information

Pablo Ranea-Robles, Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 1425 Madison Avenue, Box 1498, New York, NY 10029, USA.

Natalya N Pavlova, Cancer Biology & Genetics Program, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY 10065, USA.

Aaron Bender, Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 1425 Madison Avenue, Box 1498, New York, NY 10029, USA.

Andrea S Pereyra, Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University, Department of Physiology, and East Carolina Diabetes and Obesity Institute, Greenville, NC 27858, USA.

Jessica M Ellis, Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University, Department of Physiology, and East Carolina Diabetes and Obesity Institute, Greenville, NC 27858, USA.

Brandon Stauffer, Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 1425 Madison Avenue, Box 1498, New York, NY 10029, USA; Mount Sinai Genomics, Inc, Stamford, CT 06902, USA.

Chunli Yu, Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 1425 Madison Avenue, Box 1498, New York, NY 10029, USA; Mount Sinai Genomics, Inc, Stamford, CT 06902, USA.

Craig B Thompson, Cancer Biology & Genetics Program, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY 10065, USA.

Carmen Argmann, Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 1425 Madison Avenue, Box 1498, New York, NY 10029, USA.

Michelle Puchowicz, Department of Nutrition, School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA; Department of Pediatrics, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN 38163, USA.

Sander M Houten, Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 1425 Madison Avenue, Box 1498, New York, NY 10029, USA.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Authors’ contributions

P.R.R., N.N.P., A.B., A.S.P., J.M.E., B.S., C.Y., C.B.T., C.A., M.P., and S.M.H.: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; P.R.R. and S.M.H.: drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; J.M.E., C.Y., M.P., C.B.T., and S.M.H.: final approval of the version to be published; S.M.H.: agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 DK113172. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus Series GSE176553 and the Supplementary material online.

References

- 1. Allard MF, Schonekess BO, Henning SL, English DR, Lopaschuk GD. Contribution of oxidative metabolism and glycolysis to ATP production in hypertrophied hearts. Am J Physiol 1994;267:H742–H750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murashige D, Jang C, Neinast M, Edwards JJ, Cowan A, Hyman MC, Rabinowitz JD, Frankel DS, Arany Z. Comprehensive quantification of fuel use by the failing and nonfailing human heart. Science 2020;370:364–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aubert G, Martin OJ, Horton JL, Lai L, Vega RB, Leone TC, Koves T, Gardell SJ, Krüger M, Hoppel CL, Lewandowski ED, Crawford PA, Muoio DM, Kelly DP. The failing heart relies on ketone bodies as a fuel. Circulation 2016;133:698–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Osorio JC, Stanley WC, Linke A, Castellari M, Diep QN, Panchal AR, Hintze TH, Lopaschuk GD, Recchia FA. Impaired myocardial fatty acid oxidation and reduced protein expression of retinoid X receptor-α in pacing-induced heart failure. Circulation 2002;106:606–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ritterhoff J, Young S, Villet O, Shao D, Neto FC, Bettcher LF, Hsu YWA, Kolwicz SC, Raftery D, Tian R. Metabolic remodeling promotes cardiac hypertrophy by directing glucose to aspartate biosynthesis. Circ Res 2020:182–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Doenst T, Pytel G, Schrepper A, Amorim P, Färber G, Shingu Y, Mohr FW, Schwarzer M. Decreased rates of substrate oxidation ex vivo predict the onset of heart failure and contractile dysfunction in rats with pressure overload. Cardiovasc Res 2010;86:461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bedi KC, Snyder NW, Brandimarto J, Aziz M, Mesaros C, Worth AJ, Wang LL, Javaheri A, Blair IA, Margulies KB, Rame JE. Evidence for intramyocardial disruption of lipid metabolism and increased myocardial ketone utilization in advanced human heart failure. Circulation 2016;133:706–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dávila-Román VG, Vedala G, Herrero P, De Las Fuentes L, Rogers JG, Kelly DP, Gropler RJ. Altered myocardial fatty acid and glucose metabolism in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sack MN, Rader TA, Park S, Bastin J, McCune SA, Kelly DP. Fatty acid oxidation enzyme gene expression is downregulated in the failing heart. Circulation 1996;94:2837–2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Knottnerus SJG, Bleeker JC, Ferdinandusse S, Houtkooper RH, Langeveld M, Nederveen AJ, Strijkers GJ, Visser G, Wanders RJA, Wijburg FA, Boekholdt SM, Bakermans AJ. Subclinical effects of long-chain fatty acid β-oxidation deficiency on the adult heart: a case-control magnetic resonance study. J Inherit Metab Dis 2020;43:969–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bonnet D, Martin D, De Lonlay P, Villain E, Jouvet P, Rabier D, Brivet M, Saudubray JM. Arrhythmias and conduction defects as presenting symptoms of fatty acid oxidation disorders in children. Circulation 1999;100:2248–2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kelly DP, Strauss AW. Inherited Cardiomyopathies. N Engl J Med 1994;330:913–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kelly DP, Mendelsohn NJ, Sobel BE, Bergmann SR. Detection and assessment by positron emission tomography of a genetically determined defect in myocardial fatty acid utilization (long-chain acyl-coa dehydrogenase deficiency). Am J Cardiol 1993;71:738–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bergmann SR, Herrero P, Sciacca R, Hartman JJ, Rubin PJ, Hickey KT, Epstein S, Kelly DP. Characterization of altered myocardial fatty acid metabolism in patients with inherited cardiomyopathy. J Inherit Metab Dis 2001;24:657–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bakermans AJ, Geraedts TR, Van Weeghel M, Denis S, João Ferraz M, Aerts JMFG, Aten J, Nicolay K, Houten SM, Prompers JJ. Fasting-induced myocardial lipid accumulation in long-chain acyl-coa dehydrogenase knockout mice is accompanied by impaired left ventricular function. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4:558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Houten SM, Herrema H, te Brinke H, Denis S, Ruiter JPN, van Dijk TH, Argmann CA, Ottenhoff R, Müller M, Groen AK, Kuipers F, Reijngoud DJ, Wanders RJA. Impaired amino acid metabolism contributes to fasting-induced hypoglycemia in fatty acid oxidation defects. Hum Mol Genet 2013;22:5249–5261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kurtz DM, Rinaldo P, Rhead WJ, Tian L, Millington DS, Vockley J, Hamm DA, Brix AE, Lindsey JR, Pinkert CA, O’Brien WE, Wood PA. Targeted disruption of mouse long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase gene reveals crucial roles for fatty acid oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:15592–15597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chegary M, Brinke HT, Ruiter JPN, Wijburg FA, Stoll MSK, Minkler PE, van Weeghel M, Schulz H, Hoppel CL, Wanders RJA, Houten SM. Mitochondrial long chain fatty acid β-oxidation in man and mouse. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009;1791:806–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cox KB, Liu J, Tian L, Barnes S, Yang Q, Wood PA. Cardiac hypertrophy in mice with long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase or very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Lab Investig 2009;89:1348–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bakermans AJ, Dodd MS, Nicolay K, Prompers JJ, Tyler DJ, Houten SM. Myocardial energy shortage and unmet anaplerotic needs in the fasted long-chain acyl-Co A dehydrogenase knockout mouse. Cardiovasc Res 2013;100:441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harding HP, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Wek R, Schapira M, Ron D. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell 2000;6:1099–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pakos-Zebrucka K, Koryga I, Mnich K, Ljujic M, Samali A, Gorman AM. The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep 2016;17:1374–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Costa-Mattioli M, Walter P. The integrated stress response: from mechanism to disease. Science 2020;368:eaat5314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vattem KM, Wek RC. Reinitiation involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:11269–11274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harding HP, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Novoa I, Lu PD, Calfon M, Sadri N, Yun C, Popko B, Paules R, Stojdl DF, Bell JC, Hettmann T, Leiden JM, Ron D. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell 2003;11:619–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Torrence ME, Macarthur MR, Hosios AM, Valvezan AJ, Asara JM, Mitchell JR, Manning BD. The mtorc1-mediated activation of atf4 promotes protein and glutathione synthesis downstream of growth signals. Elife 2021;10:e63326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Luther RJ, Almodovar AJO, Fullerton R, Wood PA. Acadl-SNP based genotyping assay for long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficient mice. Mol Genet Metab 2012;106:62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pereyra AS, Hasek LY, Harris KL, Berman AG, Damen FW, Goergen CJ, Ellis JM. Loss of cardiac carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2 results in rapamycin-resistant, acetylation-independent hypertrophy. J Biol Chem 2017;292:18443–18456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pereyra AS, Harris KL, Soepriatna AH, Waterbury QA, Bharathi SS, Zhang Y, Fisher-Wellman KH, Goergen CJ, Goetzman ES, Ellis JM. Octanoate is differentially metabolized in liver and muscle and fails to rescue cardiomyopathy in CPT2 deficiency. J Lipid Res 2021;62:100069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ranea-Robles P, Yu C, van Vlies N, Vaz FM, Houten SM. Slc22a5 haploinsufficiency does not aggravate the phenotype of the long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase KO mouse. J Inherit Metab Dis 2020;43:486–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leandro J, Violante S, Argmann CA, Hagen J, Dodatko T, Bender A, Zhang W, Williams EG, Bachmann AM, Auwerx J, Yu C, Houten SM. Mild inborn errors of metabolism in commonly used inbred mouse strains. Mol Genet Metab 2019;126:388–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Le A, Ng A, Kwan T, Cusmano-Ozog K, Cowan TM. A rapid, sensitive method for quantitative analysis of underivatized amino acids by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci 2014;944:166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pavlova NN, King B, Josselsohn RH, Violante S, Macera VL, Vardhana SA, Cross JR, Thompson CB. Translation in amino-acid-poor environments is limited by tRNAGln charging. Elife 2020;9:e62307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yuan CL, Sharma N, Gilge DA, Stanley WC, Li Y, Hatzoglou M, Previs SF. Preserved protein synthesis in the heart in response to acute fasting and chronic food restriction despite reductions in liver and skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol - Endocrinol Metab 2008;295:E216–E222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bederman IR, Dufner DA, Alexander JC, Previs SF. Novel application of the ‘doubly labeled’ water method: measuring CO2 production and the tissue-specific dynamics of lipid and protein in vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2006;290:E1048–E1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gasier HG, Fluckey JD, Previs SF. The application of 2H2O to measure skeletal muscle protein synthesis. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2010;7:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bederman IR, Lai N, Shuster J, Henderson L, Ewart S, Cabrera ME. Chronic hindlimb suspension unloading markedly decreases turnover rates of skeletal and cardiac muscle proteins and adipose tissue triglycerides. J Appl Physiol 2015;119:16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lu PD, Harding HP, Ron D. Translation reinitiation at alternative open reading frames regulates gene expression in an integrated stress response. J Cell Biol 2004;167:27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Quirós PM, Prado MA, Zamboni N, D’Amico D, Williams RW, Finley D, Gygi SP, Auwerx J. Multi-omics analysis identifies ATF4 as a key regulator of the mitochondrial stress response in mammals. J Cell Biol 2017;216:2027–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Siu F, Bain PJ, Leblanc-Chaffin R, Chen H, Kilberg MS. ATF4 is a mediator of the nutrient-sensing response pathway that activates the human asparagine synthetase gene. J Biol Chem 2002;277:24120–24127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shu XE, Swanda R V, Qian SB. Nutrient control of mRNA translation. Annu Rev Nutr 2020;40:51–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Soeters MR, Serlie MJ, Sauerwein HP, Duran M, Ruiter JP, Kulik W, Ackermans MT, Minkler PE, Hoppel CL, Wanders RJA, Houten SM. Characterization of D-3-hydroxybutyrylcarnitine (ketocarnitine): an identified ketosis-induced metabolite. Metabolism 2012;61:966–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ben-Sahra I, Hoxhaj G, Ricoult SJH, Asara JM, Manning BD. mTORC1 induces purine synthesis through control of the mitochondrial tetrahydrofolate cycle. Science 2016;351:728–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic- reticulum-resident kinase. Nature 1999;397:271–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell 2001;107:881–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Berlanga JJ, Santoyo J, De Haro C. Characterization of a mammalian homolog of the GCN2 eukaryotic initiation factor 2α kinase. Eur J Biochem 1999;265:754–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang P, McGrath BC, Reinert J, Olsen DS, Lei L, Gill S, Wek SA, Vattem KM, Wek RC, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS, Cavener DR. The GCN2 eIF2α kinase is required for adaptation to amino acid deprivation in mice. Mol Cell Biol 2002;22:6681–6688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wek SA, Zhu S, Wek RC. The histidyl-tRNA synthetase-related sequence in the eIF-2 alpha protein kinase GCN2 interacts with tRNA and is required for activation in response to starvation for different amino acids. Mol Cell Biol 1995;15:4497–4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Inglis AJ, Masson GR, Shao S, Perisic O, McLaughlin SH, Hegde RS, Williams RL. Activation of GCN2 by the ribosomal P-stalk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:4946–4954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ishimura R, Nagy G, Dotu I, Chuang JH, Ackerman SL. Activation of GCN2 kinase by ribosome stalling links translation elongation with translation initiation. Elife 2016;5:e14295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dong J, Qiu H, Garcia-Barrio M, Anderson J, Hinnebusch AG. Uncharged tRNA activates GCN2 by displacing the protein kinase moiety from a bipartite tRNA-binding domain. Mol Cell 2000;6:269–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kühl I, Miranda M, Atanassov I, Kuznetsova I, Hinze Y, Mourier A, Filipovska A, Larsson N-G. Transcriptomic and proteomic landscape of mitochondrial dysfunction reveals secondary coenzyme Q deficiency in mammals. Elife 2017;6:e30952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jiang H, Hooper C, Kelly M, Steeples V, Simon JN, Beglov J, Azad AJ, Leinhos L, Bennett P, Ehler E, Kalisch-Smith JI, Sparrow DB, Fischer R, Heilig R, Isackson H, Ehsan M, Patone G, Huebner N, Davies B, Watkins H, Gehmlich K. Functional analysis of a gene-edited mouse model to gain insights into the disease mechanisms of a titin missense variant. Basic Res Cardiol 2021;116:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Galindo CL, Skinner MA, Errami M, Olson LD, Watson DA, Li J, McCormick JF, McIver LJ, Kumar NM, Pham TQ, Garner HR. Transcriptional profile of isoproterenol-induced cardiomyopathy and comparison to exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy and human cardiac failure. BMC Physiol 2009;9:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tărlungeanu DC, Deliu E, Dotter CP, Kara M, Janiesch PC, Scalise M, Galluccio M, Tesulov M, Morelli E, Sonmez FM, Bilguvar K, Ohgaki R, Kanai Y, Johansen A, Esharif S, Ben-Omran T, Topcu M, Schlessinger A, Indiveri C, Duncan KE, Caglayan AO, Gunel M, Gleeson JG, Novarino G. Impaired amino acid transport at the blood brain barrier is a cause of autism spectrum disorder. Cell 2016;167:1481–1494.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dogan SA, Pujol C, Maiti P, Kukat A, Wang S, Hermans S, Senft K, Wibom R, Rugarli EI, Trifunovic A. Tissue-specific loss of DARS2 activates stress responses independently of respiratory chain deficiency in the heart. Cell Metab 2014;19:458–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Forsström S, Jackson CB, Carroll CJ, Kuronen M, Pirinen E, Pradhan S, Marmyleva A, Auranen M, Kleine IM, Khan NA, Roivainen A, Marjamäki P, Liljenbäck H, Wang L, Battersby BJ, Richter U, Velagapudi V, Nikkanen J, Euro L, Suomalainen A. Fibroblast growth factor 21 drives dynamics of local and systemic stress responses in mitochondrial myopathy with mtDNA deletions. Cell Metab 2019;30:1040–1054.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mick E, Titov DV, Skinner OS, Sharma R, Jourdain AA, Mootha VK. Distinct mitochondrial defects trigger the integrated stress response depending on the metabolic state of the cell. Elife 2020;9:e49178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Feng W, Lei T, Wang Y, Feng R, Yuan J, Shen X, Wu Y, Gao J, Ding W, Lu Z. GCN2 deficiency ameliorates cardiac dysfunction in diabetic mice by reducing lipotoxicity and oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 2019;130:128–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lu Z, Xu X, Fassett J, Kwak D, Liu X, Hu X, Wang H, Guo H, Xu D, Yan S, Mcfalls EO, Lu F, Bache RJ, Chen Y. Loss of the eukaryotic initiation factor 2α kinase general control nonderepressible 2 protects mice from pressure overload-induced congestive heart failure without affecting ventricular hypertrophy. Hypertension 2014;63:128–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Guo X, Aviles G, Liu Y, Tian R, Unger BA, Lin YHT, Wiita AP, Xu K, Correia MA, Kampmann M. Mitochondrial stress is relayed to the cytosol by an OMA1–DELE1–HRI pathway. Nature 2020;579:427–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fessler E, Eckl EM, Schmitt S, Mancilla IA, Meyer-Bender MF, Hanf M, Philippou-Massier J, Krebs S, Zischka H, Jae LT. A pathway coordinated by DELE1 relays mitochondrial stress to the cytosol. Nature 2020;579:433–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Condon KJ, Orozco JM, Adelmann CH, Spinelli JB, van der Helm PW, Roberts JM, Kunchok T, Sabatini DM. Genome-wide CRISPR screens reveal multitiered mechanisms through which mTORC1 senses mitochondrial dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021;118: e2022120118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kim Y, Park J, Kim S, Kim MA, Kang MG, Kwak C, Kang M, Kim B, Rhee HW, Kim VN. PKR senses nuclear and mitochondrial signals by interacting with endogenous double-stranded RNAs. Mol Cell 2018;71:1051–1063.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ludmerer SW, Wright DJ, Schimmel P. Purification of glutamine tRNA synthetase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. A monomeric aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase with a large and dispensable NH2- terminal domain. J Biol Chem 1993;268:5519–5523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kern D, Potier S, Lapointe J, Boulanger Y. The glutaminyl-transfer RNA synthetase of Escherichia coli. Purification, structure and function relationship. Biochim Biophys Acta 1980;607:65–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hoben P, Söll D. Glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase of Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol 1985;113:55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bao XR, Ong S-E, Goldberger O, Peng J, Sharma R, Thompson DA, Vafai SB, Cox AG, Marutani E, Ichinose F, Goessling W, Regev A, Carr SA, Clish CB, Mootha VK. Mitochondrial dysfunction remodels one-carbon metabolism in human cells. Elife 2016;5:e10575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nikkanen J, Forsström S, Euro L, Paetau I, Kohnz RA, Wang L, Chilov D, Viinamäki J, Roivainen A, Marjamäki P, Liljenbäck H, Ahola S, Buzkova J, Terzioglu M, Khan NA, Pirnes-Karhu S, Paetau A, Lönnqvist T, Sajantila A, Isohanni P, Tyynismaa H, Nomura DK, Battersby BJ, Velagapudi V, Carroll CJ, Suomalainen A. Mitochondrial DNA replication defects disturb cellular dNTP pools and remodel one-carbon metabolism. Cell Metab 2016;23:635–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Gibb AA, Hill BG. Metabolic coordination of physiological and pathological cardiac remodeling. Circ. Res 2018;123:107–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus Series GSE176553 and the Supplementary material online.