Keywords: disuse muscle atrophy, eIF4E, mTORC1, 4E-BP1

Abstract

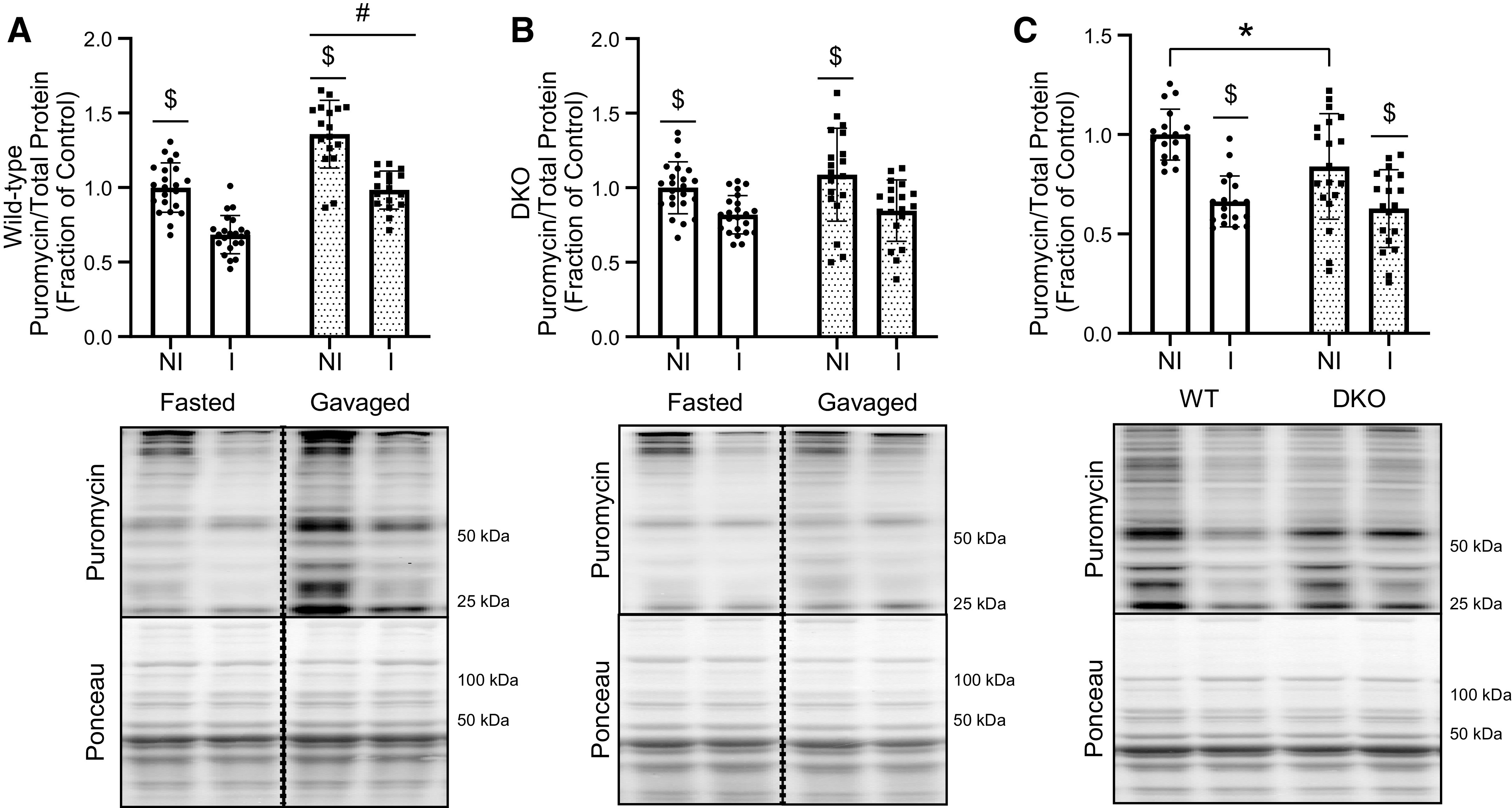

The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that upregulating protein synthesis attenuates the loss of muscle mass in a model of disuse atrophy. The studies compared the effect of unilateral hindlimb immobilization in wild-type (WT) mice and double-knockout (DKO) mice lacking the translational regulators 4E-BP1 and 4E-BP2. Immobilization-induced downregulation of protein synthesis occurred in both groups of mice, but protein synthesis was higher in gastrocnemius muscle from the immobilized hindlimb of fasted DKO compared with WT mice. Surprisingly, although protein synthesis was partially elevated in DKO compared with WT mice, atrophy occurred to the same extent in both groups of animals. This may be partially due to impaired leucine-induced stimulation of protein synthesis in DKO compared with WT mice due to downregulated eukaryotic initiation factor eIF4E expression in muscle of DKO compared with WT mice. Expression of the E3 ubiquitin ligases MAFbx and MuRF-1 mRNAs and total protein ubiquitylation was upregulated in the immobilized compared with the nonimmobilized hindlimb of both WT and DKO mice, with little difference in the magnitude of the upregulation between genotypes. Analysis of newly synthesized proteins revealed downregulation of several glycolytic enzymes in the gastrocnemius of DKO mice compared with WT mice, as well as in the immobilized compared with the nonimmobilized hindlimb. Overall, the results suggest that the elevated rate of protein synthesis during hindlimb immobilization in fasted DKO mice is insufficient to prevent disuse-induced muscle atrophy, probably due to induction of compensatory mechanisms including downregulation of eIF4E expression.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Basal rates of protein synthesis are elevated in skeletal muscle in the immobilized leg of mice lacking the translational repressors, 4E-BP1 and 4E-BP2 (knockout mice), compared with wild-type mice. However, disuse-induced muscle atrophy occurs to the same extent in both wild-type and knockout mice suggesting that compensatory mechanisms are induced that overcome the upregulation of muscle protein synthesis. Proteomic analysis revealed that mRNAs encoding several glycolytic enzymes are differentially translated in wild-type and knockout mice.

INTRODUCTION

Disuse-induced skeletal muscle atrophy is often a comorbidity in patients who suffer from long-term bed rest, limb immobilization, or limb suspension. The atrophy associated with disuse is characterized by loss of muscle mass and strength and is correlated with worsened health outcomes and survival rates in patients (1–6). Notably, significant muscle mass loss occurs within 3 days after immobilization (7), making muscle atrophy an urgent issue to address. Disuse-induced atrophy is the result of an imbalance between the rates of skeletal muscle protein synthesis and muscle protein degradation, which favors protein degradation and results in loss of muscle mass (8). The synthesis/degradation imbalance is caused in part by an insensitivity to nutrients that develops in immobilized muscle, termed anabolic resistance (9). In anabolic resistance, nutrient-stimulated rates of protein synthesis in immobilized skeletal muscle are markedly lower than in nonimmobilized muscle, resulting in a net increase in the ratio of protein degradation to protein synthesis, resulting in muscle atrophy (1–3, 7, 8, 10–12). To find therapeutic targets to treat disuse-induced muscle atrophy, molecular mechanisms behind the protein synthesis/degradation imbalance must be investigated further.

Playing a key role in the development of anabolic resistance is the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) that regulates protein synthesis by phosphorylating three downstream targets, the 70 kDa ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 (p70S6K1) and eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 4E (eIF4E) binding proteins 1 and 2 (4E-BP1 and 4E-BP2, respectively) (13). These downstream targets affect the assembly of the eIF4F complex, which consists of a scaffold protein (eIF4G), an mRNA helicase protein (eIF4A), and a 5′ 7-methyl-guanosine mRNA cap-binding protein eIF4E (14). Assembly of this complex is rate limiting in cap-dependent translation initiation and requires availability of eIF4E (14, 15). When phosphorylated and activated, p70S6K1 phosphorylates multiple downstream targets that participate in translation initiation including ribosomal protein S6 (RPS6), eIF4B, and programmed cell death protein 4 (PDCD4) (16, 17). The two other downstream targets, 4E-BP1 and 4E-BP2, bind to and sequester eIF4E, effectively preventing its association with the eIF4G scaffold (13). Phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and 4E-BP2 by mTORC1 promotes their release from eIF4E, allowing eIF4E to associate with the eIF4G·eIF4A complex to form the eIF4F complex (14).

The effects of knocking out 4E-BP1 and its isoform 4E-BP2 have been studied in a variety of different contexts with the hypothesis that increased rates of eIF4F complex assembly results in higher rates of translation. In support of this hypothesis, in the liver of mice in which the genes encoding both 4E-BP1 and 4E-BP2 have been disrupted (4E-BP1/2 DKO), eIF4E is constitutively associated with eIF4G, and the eIF4E·eIF4G complex is insensitive to changes in mTORC1 signaling, e.g., in response to refeeding a fasted animal (16). The eIF4E·eIF4G complex is also insensitive to changes in mTORC1 signaling in 4E-BP1/2 DKO mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Moreover, in serum-deprived DKO MEFs, protein synthesis is elevated compared with serum-deprived wild-type cells (16). The increase in protein synthesis also occurs in skeletal muscle in vivo, as 4E-BP1/2 DKO mice have been shown to be resistant to age-induced sarcopenia (18). However, whether deficiency in 4E-BP1/2 attenuates the acute effects of disuse in the development of skeletal muscle atrophy is unexplored. The present study tests the hypothesis that loss of 4E-BP1/2 prevents immobilization-induced reduction in eIF4E association with eIF4G, thereby promoting muscle protein synthesis and atrophy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Protocol

All mice used in the experiments were housed in temperature-controlled conditions on a 12-h light/dark schedule. WT mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories and underwent at least a 1-wk acclimation period to the facility before experimental procedures commenced. Breeding protocols and experimental procedures were all approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Penn State University College of Medicine following National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines. Mice used in the experiments were either male or female global 4E-BP1/2 DKO mice (kindly provided by Dr. Nahum Sonenburg, McGill University) or complementary age and sex-matched WT mice from Charles River Laboratories. Both DKO and WT mice were of the C57Bl/6N background and were 8–9 wk of age when the experiment began. This study used both male and female mice. Though some research into different atrophic responses to disease states has shown that females tend to experience more muscle atrophy in response to disuse than males, mTORC1 signaling has not been shown to differ between sexes under a variety of stimuli (19). Regardless, all comparisons presented in the results were analyzed for sex differences and none were observed, leading us to combine the two groups. Each mouse was provided food and water ad libitum until onset of each experiment.

Experimental Design

Methodology for unilateral hindlimb immobilization followed the established protocol laid out by Lang et al. (20). Briefly, mice were anesthetized using 2%–3% isoflurane in O2. Each mouse had one hindlimb shaved of hair using clippers before it was wrapped in surgical tape until it reached the inner diameter of a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube. A small amount of superglue was applied to the outside of the surgical tape before a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube was slid over the tape to hold the hindlimb in the plantarflexed position. The lid of each tube was removed, and the bottom tip was cut off before application to allow for adequate ventilation. The contralateral limb remained nonimmobilized and served as a control. Previous research has shown that the nonimmobilized hindlimb does not experience hypertrophy (20). After the procedure, each mouse was individually housed for 3 or 7 days and provided food and water ad libitum. In addition, food was left at the bottom of the cage in case the immobilization affected the ability to reach food overhead. Mice were then fasted for 4–5 h, anesthetized with isoflurane as described earlier, and the hindlimb muscles (gastrocnemius, plantaris, and soleus) were excised and weighed. Though the absolute mass of the muscles was different between male and female mice, these differences disappeared when muscle weights were made relative to total body weight. This has also been shown previously by Steiner et al. (21). In a separate experiment, mice were fasted for 4–5 h before receiving an oral gavage of leucine dissolved in distilled water (0.27 g/kg body wt). This amount was determined to be sufficient to induce an increase in protein synthesis in wild-type mice (data not shown) while avoiding a potential maximal anabolic response that could mask differences between the genotypes (22). Hindlimb muscles were excised 45 min postgavage. Body composition analysis was performed on 12 mice of each genotype using a Bruker Minispec LF110 (Billerica, MA) to measure total lean and fat mass before immobilization.

Protein Synthesis

In vivo protein synthesis was measured using the SUnSET method (23, 24). Briefly, after 3 days of unilateral hindlimb immobilization, WT and DKO mice were fasted for 4–5 h before receiving an intraperitoneal injection of 0.04 µmol puromycin/g body weight (A.G. Scientific, Inc. #P-1033) dissolved in sterile saline. After 27 min, the mice were anesthetized and the hindlimb muscles were excised at the 30 min mark, processed for Western blotting, and probed for puromycin (23, 24). In the case of leucine-gavaged mice, injections of puromycin were given 15 min postgavage and tissue was collected 30 min later. Puromycin incorporation was made relative to total protein as assessed by Ponceau S staining of the membrane.

Western Blotting

After hindlimb muscles were collected, half of each muscle was homogenized with plastic pestles in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen Cat. No. 15596026) for mRNA analysis while the other half was homogenized in 1.5-mL tubes with ice-cold homogenization buffer [20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 2 mM EGTA, 50 mM NaF, 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 2 mM benzamidine, and 30 µL/mL protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich Cat. No. P8340)]. Homogenized samples were then centrifuged at 13,400 g for 10 min at 4°C before protein quantification using Bradford assays. Samples were standardized for protein and then mixed with 4X SDS buffer and β-mercaptoethanol (BME) for a final concentration of 1X SDS and 10% BME and then boiled at 100°C for 5 min. Protein samples were separated using SDS-PAGE on 10% Criterion TGX precast gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and then transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore Cat. No. IPVH00010). After staining for total protein using Ponceau S (Sigma-Aldrich Cat. No. P3504), each membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk dissolved in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich Cat. No. P1379) (TBST). Membranes were then probed for either total p70S6K1 (Bethyl Cat. No. A300-510A, 1:10,000), total 4E-BP1 (Bethyl Cat. No. A300-510A, 1:10,000), phospho-p70S6K1 (T389) (Cell Signaling Cat. No. 9234, 1:1,000), phospho-4E-BP1 (S65) (Cell Signaling Cat. No. 9451, 1:1,000), total eIF4E (Cell Signaling Cat. No. 9742, 1:1,000), total MAFbx (ECM Biosciences Cat. No. AM3141, 1:1,000), total AKT (Cell Signaling Cat. No. 9272, 1:1,000), phospho-AKT (S473) (Cell Signaling Cat. No. 4060, 1:1,000), total RPS6 (Cell Signaling Cat. No. 2217, 1:1,000), phospho-RPS6 (S240/244) (Cell Signaling Cat. No. 2215, 1:1,000), K-48 linked ubiquitin (Cell Signaling Cat. No. 8081, 1:1,000), or total ubiquitin (Stressgen Cat. No. SPA-203, 1:1,000) overnight at 4°C. The puromycin antibody was made in-house, but is also distributed by Kerafast, Inc. (Cat. No. Eq. 0001, 1:1,000). The following day after washing with TBST, membranes were incubated with anti-rabbit (Bethyl Cat. No. A120-101P, 1:10,000 or Cell Signaling Cat. No. 7074, 1:3,000) or anti-mouse (Bethyl Cat. No. A90-116P, 1:10,000) horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody in 5% milk at room temperature. After incubation, blots were washed again with TBST and covered in Clarity Western ECL Blotting Substrate (Bio-Rad Cat. No. 1705060) before imaging for chemiluminescence on a FluorChem M imaging system (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA). To account for differential transfer efficiency and variance in exposure time, all gels within each experiment contained a standardized sample run in duplicate, to which all other samples within the same gel were normalized. Blots were quantified using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD) (25).

eIF4E Immunoprecipitation

To immunoprecipitate eIF4E and associated proteins, goat anti-mouse IgG beads (Qiagen Cat. No. 310007) were washed with low-salt buffer (LSB) (20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 0.1% BME) and then blocked with 1% milk in LSB at 4°C for 1 h. After this period, beads were washed and resuspended in LSB before being incubated with 10 µg of mouse anti-eIF4E antibody (made in-house and distributed by KeraFast Cat. No. EQ-0003) per 250 µL of beads for 2 h. During this time, gastrocnemius muscles were collected and processed in ice-cold homogenization buffer as described above under Western Blotting. Protein concentration was assessed by Bradford assay, and 1 mg of protein from the homogenate was added to 250 µL of beads and brought up to a standard volume before mixing for 2 h at 4°C. Beads were then washed twice in ice-cold LSB, followed by a wash in high salt buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 0.04% BME). Beads were then resuspended in 2X SDS buffer with 10% BME before being boiled for 5 min at 100°C and frozen at −80°C until Western blots were performed.

RNA Extraction and qPCR

Gastrocnemius muscle was homogenized using plastic pestles and frozen in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen Cat. No. 15596026) until RNA was extracted using the manufacturer’s protocol. After quantification using a NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 1 µg of RNA was used to produce cDNA with a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystem Cat. No. 4374966) following the manufacturer’s protocol. qPCR was then performed in triplicate using SYBR Green master mix and primers for β-actin (Forward 5′- ACGGCCAGGTCATCACTATTG-3′, Reverse 5′- TGGAAAAGAGCCTCAGGGC-3′), MAFbx (Forward 5′- AACCGGGAGGCCAGCTAAAGAACA-3′, Reverse 5′- TGGGCCTACAGAACAGACAGTGC-3′), and MuRF-1 (Forward 5′- GAGAACCTGGAGAAGCAGCT-3′, Reverse 5′- CCGCGGTTGGTCCAGTAG-3′). mRNA expression was normalized to β-actin mRNA levels, which exhibited no difference between genotypes and conditions, using the 2–ΔΔCt method (26). All figures were standardized to the control mean of WT nonimmobilized muscle.

Bioorthogonal Noncanonical Amino Acid Tagging and Proteomics

Newly synthesized proteins were identified by bioorthogonal noncanonical amino acid tagging (BONCAT) analysis (27). In this study, three age- and sex-matched WT and DKO mice (1 female, 2 males for each genotype) were hindlimb immobilized for 3 days as described above. After a 4-h fasting period on the morning of the fourth day, each mouse received an oral gavage of leucine in distilled water (0.27 g/kg body wt), followed by an intraperitoneal injection of the methionine mimetic azidohomoalanine (AHA) (Click Chemistry Tools, 1066-25) dissolved in sterile saline (0.1 mg AHA/g body wt) (28). Four hours later, the hindlimb muscles were collected and homogenized in homogenization buffer before being frozen at −80°C. After verification of AHA-containing proteins in the homogenates by fluorescent tagging of AHA and visualization on a gel, muscle homogenates were combined with washed alkyne agarose beads (Click Chemistry Tools, 1032-2) and 2X copper catalyst solution [final concentration 10 mM Tris-hydroxypropyltriazolylmethylamine (THPTA), 2 mM copper (II) sulfate, and 20 mM sodium ascorbate] before rotating end-over-end for 20 h following the manufacturer’s protocol (Click Chemistry Tools). The agarose gel beads were subsequently collected in the Penn State Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Core (RRID:SCR 017831) by centrifugation, washed in deionized water, and reconstituted in triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) buffer [0.5 M triethylamine, 40 mM chlorocetamide, 2% sodium deoxycholate, 10 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), pH 8.0] before incubation for 10 min at 80°C. After three washes in TEAB, protein was digested with Trypsin-LysC overnight and then cleaned up using SDB-RPS pipette tips. The final protein concentration was standardized to 0.2 µg/µL using a NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). A Nanoelute LC delivered the gradient described below at 500 nL/min. The separation column used was a Pepsep 15 cm, ID 75 μm, 1.9 μm, 120 Å. The column buffers used were buffer A (0.1% formic acid in H2O) and buffer B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). A 30-min total cycle peptide separation gradient was used, consisting of a linear gradient for 17.22 min following sample injection (0% B to 30% B) followed by an isocratic stage for 3.63 min at 95% B, followed by an isocratic stage of column re-equilibration for 9.15 min at 0% B. The column was heated to 50°C. Each sample was injected in a Bruker Daltonics timsTOF Flex mass spectrometer (Billerica, MA), which was used for the analyses. A timsPASEF method was used: the tims accumulation time was fixed to 100 ms while the tims separation duration was set to 100 ms. The range of mobility values was 0.85–1.3 1/K0 and the covered m/z range was 100–1,700 m/z. Mass spectrometry spectra were obtained by the Penn State College of Medicine Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Core and searched against a constructed protein sequence database using the Byonic algorithm (Protein Metrics). The database searched was the NCBI RefSeq database for Mouse (77,631 protein sequences) plus a database containing the protein sequences for 536 common laboratory contaminants (compiled by the Penn State College of Medicine Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility) for a total of 78,167 forward protein sequences, plus a decoy database containing the reversed sequences of those 78,167 forward protein sequences. False positive “hits” from that reversed database were used to calculate the false discovery rate.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY) and figures were generated using GraphPad Prism 9.0.2 (La Jolla, CA). Data are shown as mean ± SD and outliers more than 2 standard deviations from the mean were omitted. Repeated-measures two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the differences between hindlimbs (immobilized and nonimmobilized) between WT and DKO mice, with Bonferroni post hoc multiple comparisons performed when a significant interaction was detected. Total body weight and body composition analysis were compared using Student’s t test. Peptides confidently identified by mass spectrometry were further analyzed for quantitative differences using Scaffold 5.12 (Proteome Software, Portland, OR) to perform Fisher’s exact tests of the spectral counts of each protein. The statistical testing threshold for significance was set at P < 0.05, with the Benjamini–Hochberg multiple testing correction, and then applied for each mass spectrometry comparison. Thresholds for trending data were set at (0.05 < P < 0.10).

RESULTS

Effects of Loss of 4E-BP1/2 on Body Composition and Disuse-Induced Muscle Atrophy

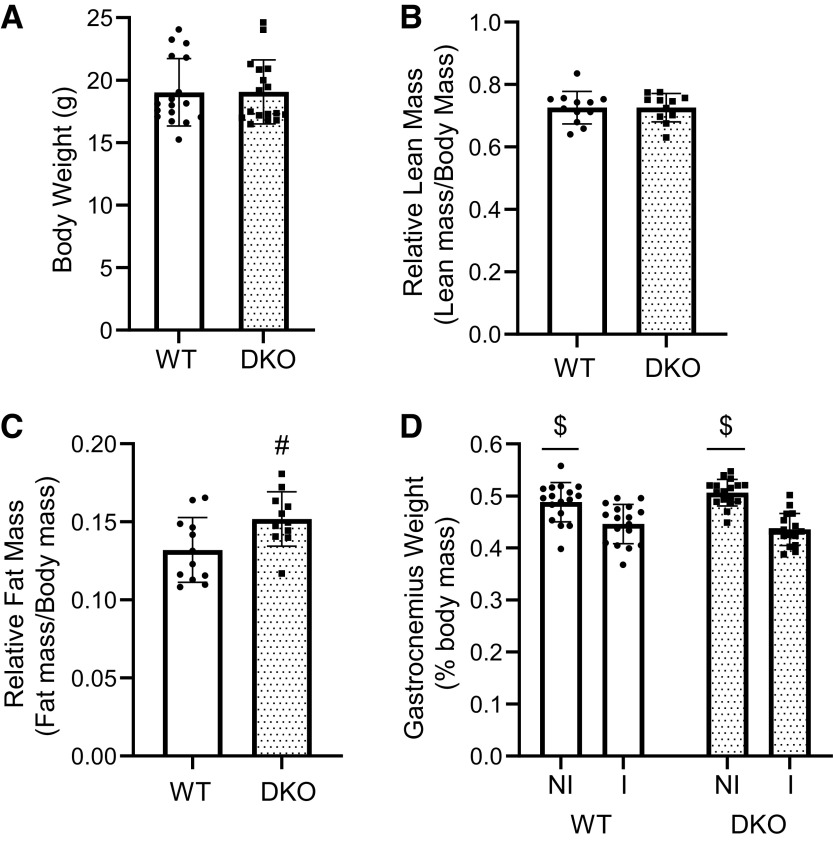

Before proceeding with hindlimb immobilization studies, the physical characteristics of WT and DKO mice were assessed. There was no significant difference in body weight between the genotypes (Fig. 1A). Body composition was assessed on 12 mice of each genotype (6 males, 6 females) using a Bruker MiniSpec LF110 (Billerica, MA) in the Penn State College of Medicine Metabolic Phenotyping Core Facility, RRID:SCR_022565. Whereas initial comparisons of raw lean mass and fat mass showed significant differences between male and female mice of both genotypes, these differences disappeared after they were made relative to body weight. Moreover, there was no significant difference between WT and DKO mice in relative lean mass (Fig. 1B). However, relative fat mass in DKO mice was significantly greater than relative fat mass in WT (Fig. 1C). Having determined that lean mass was unaffected by elimination of 4E-BP1/2, WT and DKO mice underwent 3 days of hindlimb immobilization (20). Unexpectedly, both DKO and WT mice demonstrated similar levels of gastrocnemius muscle atrophy in the immobilized limb (Fig. 1D) as well as plantaris and soleus muscle atrophy (Supplemental Fig. S1, A and B, all Supplemental material is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21187603.v1). Notably, in both DKO and WT mice, soleus muscle atrophy after 3 days was the most pronounced, followed by gastrocnemius, and then plantaris.

Figure 1.

Body composition and postimmobilization muscle atrophy in mice. A: body weight of WT and DKO mice (n = 17/genotype). B and C: relative lean and fat mass [n = 12 (WT), n = 11 (DKO), #P = 0.0220]. D: relative gastrocnemius mass after 3 days of unilateral hindlimb immobilization (n = 17/genotype, $P < 0.0001). DKO, double-knockout; I, immobilized limb; NI, nonimmobilized limb; WT, wild type. n, Number of animals.

Effects of Loss of 4E-BP1/2 on eIF4E·eIF4G Association, mTORC1 Signaling, and Protein Synthesis

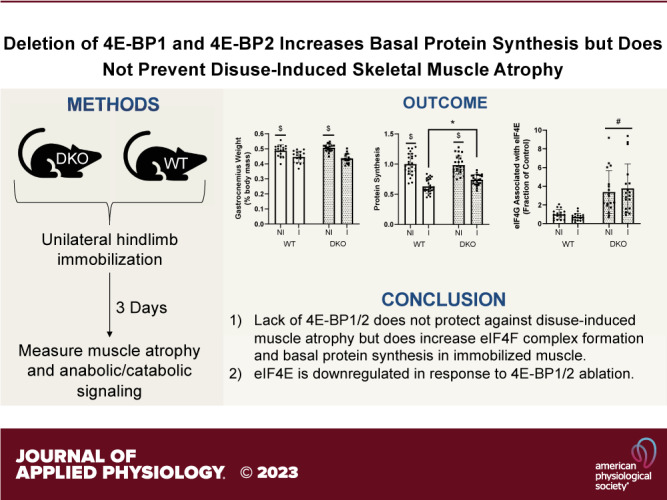

Immediately after weighing, 4E-BP1 and eIF4G association with eIF4E was assessed in gastrocnemius muscles from both the immobilized and nonimmobilized hindlimbs. As expected, the amount of eIF4G in the eIF4E immunoprecipitates was greater in muscle from DKO mice than in muscle from their WT counterparts (Fig. 2A), with no difference between muscle in the immobilized and nonimmobilized hindlimbs. 4E-BP1 was only detected in WT mice, and the association of 4E-BP1 with eIF4E was greater in the muscle of the immobilized than in the muscle of the nonimmobilized hindlimb (Fig. 2B). To assess immobilization-induced alterations in mTORC1 signaling, muscle lysates were probed for phosphorylation of p70S6K1 as well as phosphorylation of one of its downstream targets, RPS6. Although phosphorylation of both proteins was lower in the immobilized than in the nonimmobilized hindlimb, neither protein showed significantly different phosphorylation between the two genotypes (Fig. 2, C and D). Protein synthesis, as assessed by the incorporation of puromycin into nascent peptide chains, was significantly lower in muscle from the immobilized than in muscle from the nonimmobilized limbs of both WT and DKO mice. Notably, two-way ANOVA revealed a significant interaction (P = 0.0022), and post hoc comparisons showed that protein synthesis was significantly higher in the gastrocnemius muscle in immobilized hindlimbs of the DKO mice when compared with WT immobilized hindlimbs (Fig. 2E), suggesting greater protein synthesis in muscle in the immobilized hindlimb of DKO mice.

Figure 2.

Impact of hindlimb immobilization on mTORC1 signaling and protein synthesis in the gastrocnemius of fasted mice. A: eIF4G abundance in eIF4E immunoprecipitates from gastrocnemius muscle of WT and DKO mice [n = 17 (WT), n = 18 (DKO), #P < 0.0001]. B: 4E-BP1 abundance in eIF4E immunoprecipitates from gastrocnemius muscle (n = 17/genotype, #P < 0.0001, $P = 0.0092). C and D: phosphorylation of p70S6K1 and its downstream target RPS6 (n = 11/genotype, $P < 0.0001). E: protein synthesis as measured by puromycin incorporation [n = 26 (WT), n = 25 (DKO), $P < 0.0001, interaction P = 0.0022, *P = 0.0124]. Molecular weight markers are indicated at the right of each blot. Values are expressed as a fraction of the control (WT nonimmobilized hindlimb). DKO, double-knockout; I, immobilized limb; mTORC1, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1; NI, nonimmobilized limb; WT, wild type. n, Number of animals.

Effects of Loss of 4E-BP1/2 on Markers of Muscle Atrophy

To assess degradative markers of disuse-induced muscle atrophy, the abundance of MAFbx and MuRF-1 (both muscle-specific E3 ubiquitin ligases) mRNA was measured. Both mRNAs exhibited a significant increase in expression in the muscle from the immobilized compared with nonimmobilized hindlimb, regardless of genotype (Fig. 3, A and B). However, in the case of MAFbx mRNA, a significant interaction (P = 0.0249) was detected and subsequent post hoc comparisons revealed nearly a threefold increase in MAFbx mRNA expression (P = 0.0037) in the DKO immobilized hindlimb compared with its WT counterpart (Fig. 3A). Conversely, there was no significant difference in MAFbx protein levels between genotypes, though a significant immobilization effect was present (Fig. 3C). In addition to E3 ligase expression, total protein ubiquitylation was assessed and demonstrated a significant increase in muscle from the immobilized compared with nonimmobilized hindlimb, although no significant genotype differences were observed (Fig. 3D). To further investigate the proteosome-ubiquitin degradative pathway, K-48 linked ubiquitylation was assessed and showed a significant increase in muscle in the immobilized hindlimbs of both genotypes, but, similar to total ubiquitylation, no genotypic differences were observed (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Biomarkers of muscle atrophy in the gastrocnemius of fasted mice. A: MAFbx mRNA expression in gastrocnemius muscle of WT and DKO mice after 3 days of hindlimb immobilization (n = 9/genotype, $P < 0.0001, #P = 0.0229, *P = 0.0037). B: MuRF-1 mRNA expression in muscle after 3 days of hindlimb immobilization (n = 9/genotype, $P < 0.0001). C: MAFbx protein expression in muscle after 3 days of hindlimb immobilization (n = 11/genotype, $P < 0.0001). D: total ubiquitylated proteins after 3 days hindlimb immobilization [n = 21 (WT), n = 20 (DKO), $P < 0.0001). E: K-48 linked ubiquitylated proteins after 3 days of hindlimb immobilization [n = 17 (WT), n = 18 (DKO), $P < 0.0001]. Molecular weight markers are indicated at the right of each blot. Values are expressed as a fraction of the control (WT nonimmobilized hindlimb). DKO, double-knockout; I, immobilized limb; NI, nonimmobilized limb; WT, wild type. n = Number of animals.

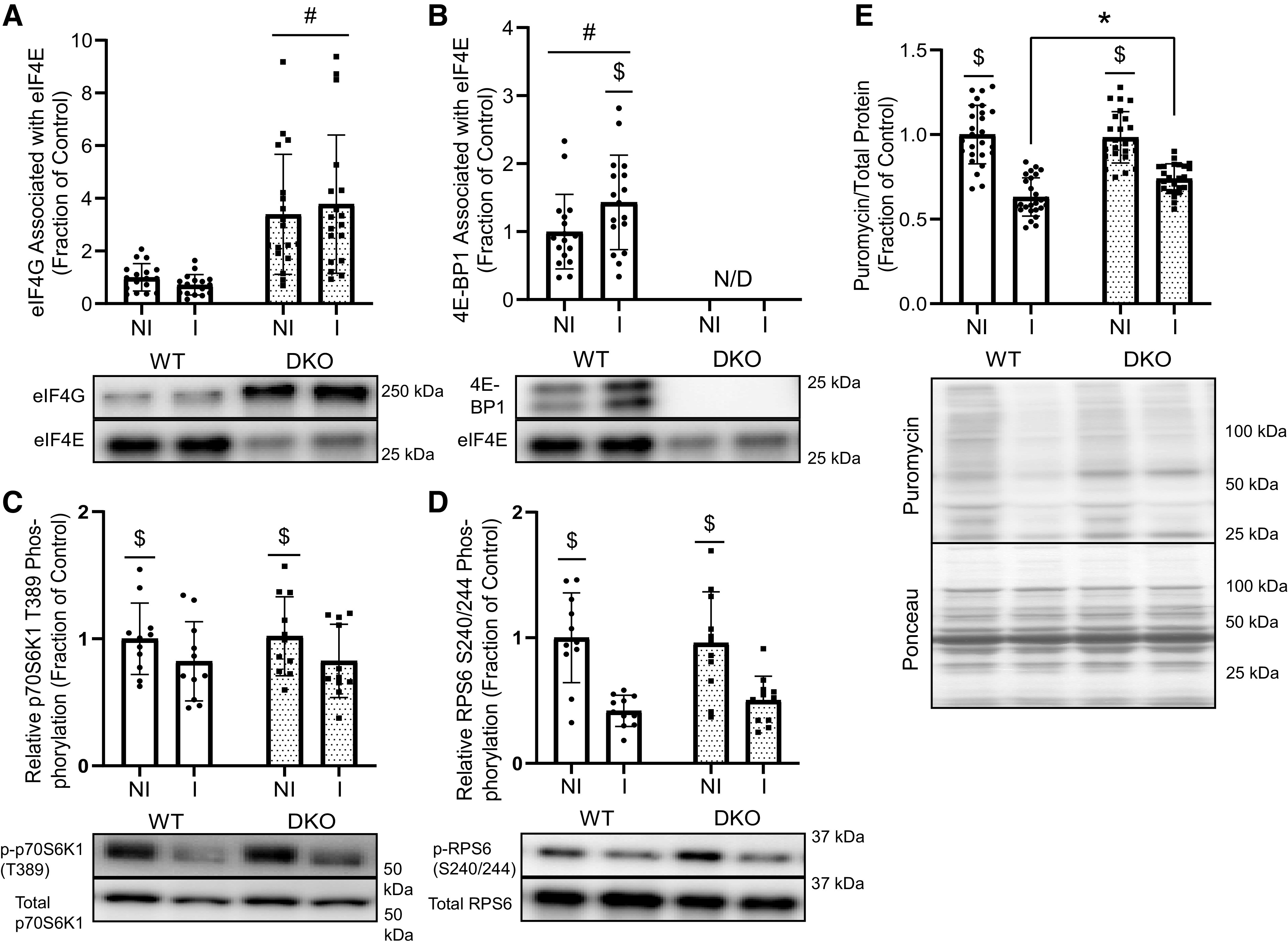

Effects of Loss of 4E-BP1/2 and Leucine Gavage on Protein Synthesis

To assess whether 4E-BP1/2 deficiency had any effect on nutrient-induced upregulation of protein synthesis, an oral dose of leucine, a potent activator of mTORC1 (29, 30), was administered to fasted mice and protein synthesis was assessed by puromycin incorporation. As expected, protein synthesis was lower in the muscle from the immobilized than in muscle from the nonimmobilized hindlimb in both WT and DKO mice (Fig. 4, A and B, respectively). Interestingly, protein synthesis was upregulated by leucine administration in WT, but not DKO mice. Reanalysis of the samples to allow for direct comparison of muscle from WT and DKO mice revealed a significant interaction (P = 0.0055) that protein synthesis was significantly lower in muscle from the nonimmobilized hindlimb of DKO mice compared with WT mice after leucine gavage (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Responses to oral leucine administration in WT and DKO muscles. A: protein synthesis in response to leucine gavage as measured by puromycin incorporation in gastrocnemius muscles of WT mice. Dotted line denotes nonconsecutive lanes from the same Western blot [n = 22 (fasted), n = 19 (leucine-gavage), $P < 0.0001, genotype effect #P < 0.0001] B: protein synthesis in response to leucine gavage as measured by puromycin incorporation in gastrocnemius muscles of DKO mice. Dotted line denotes nonconsecutive lanes from the same Western blot [n = 23 (fasted), n = 19 (leucine-gavage), $P < 0.0001]. C: WT and DKO muscle protein synthesis as measured by puromycin incorporation after leucine gavage [n = 18 (WT), n = 19 (DKO), $P < 0.0001, *P = 0.0242]. Molecular weight markers are indicated at the right of each blot. Values are expressed as a fraction of the control (WT nonimmobilized hindlimb). DKO, double-knockout; I, immobilized limb; NI, nonimmobilized limb; WT, wild type. n, Number of animals.

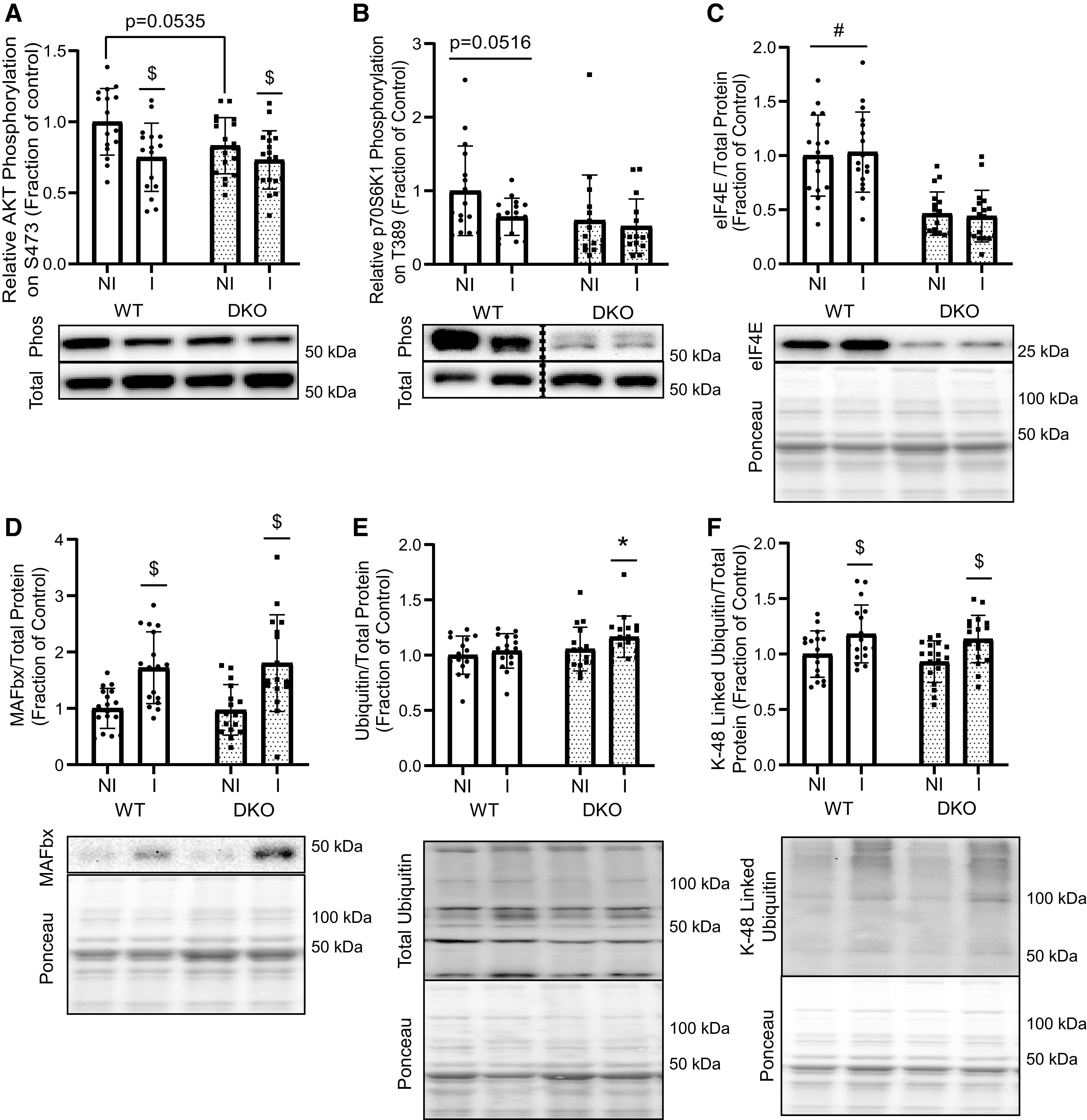

Effects of Loss of 4E-BP1/2 and Leucine Gavage on mTORC1 Signaling and Markers of Muscle Atrophy

To further investigate potential causes of the differential responses to the leucine gavage, Western blots were used to assess phosphorylation of AKT and p70S6K1, markers upstream and downstream of mTORC1, respectively. Phosphorylation of AKT on S473 was lower in muscle from the immobilized hindlimb compared with the nonimmobilized hindlimb in both WT and DKO mice after leucine gavage (Fig. 5A). Statistical analysis showed a significant interaction (P = 0.0461), and subsequent post hoc testing revealed a trending increase in AKT activation in muscle from the WT nonimmobilized hindlimbs compared with the DKO nonimmobilized hindlimbs (Fig. 5A). In addition, phosphorylation of p70S6K1 on T389 showed a trending increase in WT mice compared to with DKO mice independent of immobilization (Fig. 5B). The abundance of eIF4E was significantly lower in muscle from DKO mice than in in muscle from WT mice, independent of immobilization (Fig. 5C) and this effect was also observed in fasted mice (Supplemental Fig. S2A). However, eIF4G abundance was unaffected by immobilization or 4E-BP1/2 knockout (Supplemental Fig. S2B). As was observed in fasted mice, MAFbx protein expression was upregulated in response to immobilization with no difference between genotypes following leucine gavage (Fig. 5D). However, a significant interaction (P = 0.0201) was detected, and subsequent post hoc comparisons revealed a significant immobilization effect in total ubiquitylated protein levels in muscle from DKO but not WT mice, with a slight (10%), but statistically significant increase in the abundance of ubiquitylated proteins in the immobilized hindlimb (Fig. 5E). Upon assessing specifically K-48-linked ubiquitin chains, a significant immobilization, but not genotype, effect was observed (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5.

Anabolic and catabolic signaling in muscle after oral leucine administration. A: relative AKT (S473) phosphorylation in gastrocnemius muscle after leucine gavage [n = 16 (WT), n = 19 (DKO), $P < 0.0001]. B: relative p70S6K1 (T389) phosphorylation in muscle after leucine gavage. Dotted line denotes nonconsecutive lanes from the same Western blot (n = 16/genotype, immobilization effect P = 0.0640). C: relative eIF4E expression in muscle after leucine gavage [n = 17 (WT), n = 18 (DKO), genotype effect #P < 0.0001). D: abundance of MAFbx protein after leucine gavage [n = 17 (WT), n = 16 (DKO), $P < 0.0001]. E: total ubiquitylated protein in muscle after leucine gavage [n = 16 (WT), n = 17 (DKO), *P < 0.0001]. F: K-48 linked ubiquitylated protein in muscle after leucine gavage [n = 17 (WT), n = 18 (DKO), $P < 0.0001]. Molecular weight markers are indicated at the right of each blot. Values are expressed as a fraction of the control (WT nonimmobilized hindlimb). DKO, double-knockout; I, immobilized limb; NI, nonimmobilized limb; WT, wild type. n, Number of animals.

Acute Effects of Loss of 4E-BP1/2 and Leucine Gavage on the Pattern of mRNA Translation

To assess potential differences in the pattern of mRNA translation in WT and DKO mice after hindlimb immobilization and leucine gavage, mice were administered AHA and newly synthesized AHA-tagged proteins were isolated and subjected to mass spectrometry analysis. Ingenuity pathway analysis (Qiagen) of confidently identified newly synthesized proteins revealed a significant downregulation in the synthesis of glycolysis enzymes such as phosphofructokinase, aldolase, phosphoglycerate mutase, and pyruvate kinase both in muscle from the immobilized hindlimb of DKO mice compared with WT mice and in muscle from the nonimmobilized hindlimb of DKO mice compared with WT (Supplemental Table S1, A and B). Moreover, within a genotype, phosphofructokinase and aldolase were downregulated in muscle from the immobilized hindlimb compared with the nonimmobilized hindlimb (Supplemental Table S1, C and D). In addition, a significant downregulation in translation of the eIF4E mRNA was detected in the immobilized muscle of DKO compared with WT as well, consistent with the difference in eIF4E protein abundance observed in DKO compared with WT mice. There was also a significant upregulation in the translation of gluconeogenic enzyme mRNAs such as fructose-bisphosphatase and phosphopyruvate hydratase as well as a significant increase in glycogen synthase in muscle from the immobilized hindlimb of DKO mice compared with WT (Supplemental Table S1B).

DISCUSSION

Unilateral hindlimb immobilization is a well-established model for studying disuse-induced muscle atrophy, with the free hindlimb acting as a control (7, 11, 12, 20). Initial experiments in this study measured muscle atrophy and signaling after hindlimb immobilization for both 3-day and 7-day time points because this appeared to be within the window of the highest rates of muscle atrophy (31). However, although the effect of immobilization on gastrocnemius muscle weight was greater after 7 days of immobilization than after 3 days of immobilization (compare Supplemental Fig. S3A to Fig. 1D), no difference in eIF4E association with either eIF4G or 4E-BP1 was detected between the two time points (compare Supplemental Fig. S3, B and C, to Fig. 2, A and B, respectively). Interestingly, while relative phosphorylation of RPS6 in muscle lysates taken after 3 days of immobilization showed a significant immobilization effect, the 7-day immobilization lysates showed no significant effect for either genotype or immobilization (compare Supplemental Fig. S3D to Fig. 2D), suggesting that the atrophic effect of immobilization on mTORC1 signaling may have waned. Moreover, immobilization-induced upregulation of MAFbx protein expression was observed at both time points (compare Supplemental Fig. S3E to Fig. 3C). Consequently, all subsequent experiments used a 3-day immobilization period.

Based on previous studies showing that deficiency of 4E-BP1/2 is associated with elevated basal rates of protein synthesis (16, 18), we expected immobilization-induced muscle atrophy to be attenuated in DKO mice compared with WT mice due to an increase in protein synthesis. Indeed, after 3 days of hindlimb immobilization, basal (fasted) rates of protein synthesis in the muscle of the immobilized hindlimb of DKO mice were 17% higher than in the muscle of the immobilized hindlimb of WT mice. This increase in basal protein synthesis is in contrast with a previous study showing that the magnitude of the sepsis-induced decrease in muscle protein synthesis was similar in DKO and WT mice (21). The basis for the inability of 4E-BP1/4E-BP2 deletion to partially prevent the decrease in protein synthesis during sepsis whereas it partially rescues protein synthesis during hindlimb immobilization is unknown, although it should be noted that the mice used in the previous study were on a BALB/c background instead of a C57Bl/6N background.

Although basal rates of protein synthesis were higher in the gastrocnemius of DKO mice than in the gastrocnemius of WT mice during hindlimb immobilization, no difference between genotypes was observed in the nonimmobilized hindlimb. This result is consistent with a previous report from our group (21), but inconsistent with a report from another group showing that protein synthesis was higher in ex vivo muscle preparations from DKO mice than in ex vivo muscle preparations from WT mice after incubation in medium lacking amino acids or insulin (18). The basis for the discrepancy is unknown but could be due to differences in the age of the mice (8–9 wk in the current study vs. 24 mo old in the study by Le Bacquer et al.), their genetic background (C57Bl/6N in the current study vs. BALB/c in the study by Le Bacquer et al.), and/or the muscle examined (gastrocnemius in the current study vs. tibialis anterior in the study by Le Bacquer et al.) (18).

As expected, based on their known function in regulating eIF4E association with eIF4G, we observed a marked increase in eIF4G binding to eIF4E in DKO mice independent of limb immobilization, even in the fasted state. As previously shown (7, 11, 12, 20), mTORC1 signaling is downregulated in skeletal muscle in response to immobilization, and the response in DKO mice was no different from WT mice in this regard. Although a previous study has shown an increase in activation of mTORC1 and p70S6K1 in response to 3 days of limb immobilization (32), the disparity between the studies may be explained by both differing mouse backgrounds (FVB/N vs. C57Bl/6N) as well as differing methodologies of immobilization. Given these results, it was surprising to observe that the DKO mice still experienced the same levels of disuse-induced muscle atrophy as the WT mice, in contrast to what has been observed in the preservation of muscle mass in 4E-BP1/2 DKO mice with sarcopenia (18). A possible explanation for this apparent discrepancy is that protein degradation is disproportionally upregulated in muscle of DKO compared with WT mice. In this regard, previous studies using mice on a BALB/c rather than a C57Bl/6N background showed that 4E-BP1/2 deficiency was associated with an increase in the abundance of both MAFbx and MuRF-1 mRNA expression, supporting the idea that lack of 4E-BP1/2 somehow leads to increased E3 ubiquitin ligase gene transcription (33). Consistent with the previous report, in the present study, MAFbx mRNA expression was approximately threefold higher in the muscle of the immobilized hindlimb of fasted DKO mice compared with WT mice. However, MAFbx protein expression was unchanged, and indicators of muscle atrophy by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway such as MuRF-1 mRNA, total ubiquitylated proteins, and K-48-linked ubiquitylation in fasted muscle did not reveal any difference between genotypes. After leucine administration, ubiquitylated protein abundance was significantly higher in the immobilized hindlimb of DKO mice compared with the nonimmobilized limb, which was a difference that was not observed in WT mice. However, K-48-linked ubiquitin exhibited significant increases in immobilized muscle of both genotypes, implying that WT mice may experience a shift in relative abundance of differently linked polyubiquitin chains in response to immobilization. Further investigation into this change in ubiquitin linkage in WT mice as well as the time course of the leucine effect on DKO mice may be merited. The basis for the lack of correlation between MAFbx mRNA and protein abundance is unknown but may be due to a difference in temporal relationship between mRNA and protein expression that was not captured at the time of muscle tissue collection, though this time course has yet to be explored (34). Nevertheless, future studies investigating potential differences in rates of protein degradation in muscle of DKO compared with WT mice are warranted.

To gain a deeper understanding of the roles of 4E-BP1/2 in disuse-induced muscle atrophy and anabolic resistance, mTORC1 signaling and protein synthesis rates were assessed in DKO and WT mice after an anabolic stimulus, i.e., an oral gavage of leucine (29, 30). In response to the oral administration of leucine, there was a trend toward an increased AKT/mTORC1 response in the WT mice compared with the DKO mice as assessed by both p70S6K1 and AKT phosphorylation, consistent with the development of anabolic resistance in response to immobilization. Protein synthesis rates were significantly lower in nonimmobilized muscle of DKO mice after leucine gavage compared with nonimmobilized muscle of WT mice. This was unexpected, as a previous study showed insulin-stimulated protein synthesis was higher in ex vivo muscle preparations from DKO mice compared with WT (18). The basis for the difference in the current study compared with the previous study is unknown, though no difference in eIF4E expression was reported in the latter study. Because eIF4E is thought to be the least abundant translation initiation factor and rate-limiting for mRNA translation (13–15), it is tempting to speculate that the lower abundance of eIF4E in the muscle of DKO mice on the C57Bl/6N background used in the present study may have limited the magnitude of leucine-stimulated protein synthesis. Still, the reduction in nutrient-induced protein synthesis in muscle of DKO mice likely contributes to the development of muscle atrophy during limb immobilization.

In addition to studying the effects of leucine administration on global rates of protein synthesis in immobilized skeletal muscle in 4E-BP1/2 DKO mice, azidohomoalanine (AHA) was used to label newly synthesized proteins so that they could be isolated and identified. Ingenuity pathway analysis of the data suggests a significant downregulation in the expression of important enzymes in glycolysis such as phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1), aldolase, phosphoglycerate mutase, and pyruvate kinase that occurs in both an immobilization and genotype-specific manner in mice administered leucine by oral gavage. Whether the observed changes in mRNA translation result in downregulation of glycolysis is unknown, and this needs to be addressed in future studies. It is notable though that leucine administration previously has been shown to cause downregulation of glycolysis in C2C12 myotubes in an mTORC1-independent manner (35). Unfortunately, the mechanism involved in the effect of leucine on glycolysis was not expanded on in that study. The observed immobilization-induced decrease in glycolytic enzyme expression may be partially due to the increase in MuRF-1 mRNA detected in immobilized muscles, as MuRF-1 has been shown to interact with and downregulate a number of glycolytic enzymes and also regulates creatine kinase to alter energy availability (36, 37). Although additional experiments are still needed to investigate the extent of the downregulation of glycolytic enzyme expression specific to DKO mice, it is noteworthy that the downregulation of eIF4E mRNA translation observed in the proteomic analysis is associated with a significant downregulation of eIF4E protein expression in the muscle of DKO mice compared with WT mice. Further investigation into exactly how, or if, these observed translational changes affect glucose metabolism is needed.

Overall, the results of the present study show that protein synthesis in a fasted state is higher in the immobilized muscle of DKO mice compared with immobilized muscle WT mice, but that protein synthesis after leucine gavage is lower. We speculate that the lower eIF4E abundance in muscles of DKO mice compared with WT mice may be a “ceiling” that limits how much protein synthesis can be increased by anabolic stimuli, and that such limitation partly explains the finding that muscle atrophy occurs to a similar extent in both DKO and WT mice. In addition, in contrast to our original hypothesis, basal, i.e., fasted rates of protein synthesis were not elevated in muscle from the nonimmobilized hindlimb of DKO mice compared with WT mice and the basis for this finding should be explored in future studies. The results of the present study also suggest that expression of several enzymes that play important roles in glycolysis may be suppressed in the muscle of DKO mice compared with WT mice as well as in response to hindlimb immobilization. These data act to paint a larger picture of the global effects of loss of 4E-BP1/2 on both skeletal muscle atrophy and the protein balance within cells as well as points at potentially even further effects on glucose metabolism.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and Supplemental Table S1: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21187603.v1.

GRANTS

The studies presented here were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health DK015658 (to S.R. Kimball), DK126312 (to P.A. Roberson), EY029702 (to M.D. Dennis). The Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Core (RRID:SCR_017831) and Metabolic Phenotyping Core (RRID:SCR_022565) services and instruments used in this project were funded, in part, by the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine via the Office of the Vice Dean of Research and Graduate Students and the Pennsylvania Department of Health using Tobacco Settlement Funds (CURE).

DISCLAIMERS

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the University or College of Medicine. The Pennsylvania Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

G.N.K. and S.R.K. conceived and designed research; G.N.K., P.A.R., A.L.T., and A.E.S. performed experiments; G.N.K., P.A.R., B.A.S., A.E.S., and S.R.K. analyzed data; G.N.K., P.A.R., B.A.S., and S.R.K. interpreted results of experiments; G.N.K. prepared figures; G.N.K. drafted manuscript; G.N.K., P.A.R., A.L.T., B.A.S., A.E.S., L.S.J., M.D.D., and S.R.K. edited and revised manuscript; G.N.K., P.A.R., A.L.T., B.A.S., A.E.S., L.S.J., M.D.D., and S.R.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Nahum Sonenberg for providing the 4E-BP1/2 DKO mice. We also thank Abigale Whitsell for help with tissue processing in addition to Dr. David Waning, Dr. Brian Hain, Dr. Siddharth Sunilkumar, Shaunaci Stevens, Ashley Vancleave, Christopher McCurry, and Esma Yerlikaya for their input and advice.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dirks ML, Wall BT, van de Valk B, Holloway TM, Holloway GP, Chabowski A, Goossens GH, van Loon LJC. One week of bed rest leads to substantial muscle atrophy and induces whole-body insulin resistance in the absence of skeletal muscle lipid accumulation. Diabetes 65: 2862–2875, 2016. doi: 10.2337/db15-1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Drummond MJ, Dickinson JM, Fry CS, Walker DK, Gundermann DM, Reidy PT, Timmerman KL, Markofski MM, Paddon-Jones D, Rasmussen BB, Volpi E, Bed VE. Bed rest impairs skeletal muscle amino acid transporter expression, mTORC1 signaling, and protein synthesis in response to essential amino acids in older adults. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 302: E1113–E1122, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00603.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glover EI, Phillips SM, Oates BR, Tang JE, Tarnopolsky MA, Selby A, Smith K, Rennie MJ. Immobilization induces anabolic resistance in human myofibrillar protein synthesis with low and high dose amino acid infusion. J Physiol 586: 6049–6061, 2008. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.160333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wall BT, Dirks ML, Snijders T, van Dijk J-W, Fritsch M, Verdijk LB, van Loon LJC. Short-term muscle disuse lowers myofibrillar protein synthesis rates and induces anabolic resistance to protein ingestion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 310: E137–E147, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00227.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jaitovich A, Khan MMHS, Itty R, Chieng HC, Dumas CL, Nadendla P, Fantauzzi JP, Yucel RM, Feustel PJ, Judson MA. ICU admission muscle and fat mass, survival, and disability at discharge: a prospective cohort study. Chest 155: 322–330, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moisey LL, Mourtzakis M, Cotton BA, Premji T, Heyland DK, Wade CE, Bulger E, Kozar RA; Nutritional and Rehabilitation Investigators Consortium (NUTRIC). Skeletal muscle predicts ventilator-free days, ICU-free days, and mortality in elderly ICU patients. Crit Care 17: R206, 2013. doi: 10.1186/cc12901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roberson PA, Shimkus KL, Welles JE, Xu D, Whitsell AL, Kimball EM, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR. A time course for markers of protein synthesis and degradation with hindlimb unloading and the accompanying anabolic resistance to refeeding. J Appl Physiol (1985) 129: 36–46, 2020. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00155.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Phillips SM, Glover EI, Rennie MJ. Alterations of protein turnover underlying disuse atrophy in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985) 107: 645–654, 2009. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00452.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cuthbertson D, Smith K, Babraj J, Leese G, Waddell T, Atherton P, Wackerhage H, Taylor PM, Rennie MJ. Anabolic signaling deficits underlie amino acid resistance of wasting, aging muscle. FASEB J 19: 1–22, 2005. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2640fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miokovic T, Armbrecht G, Felsenberg D, Belavý DL. Heterogeneous atrophy occurs within individual lower limb muscles during 60 days of bed rest. J Appl Physiol (1985) 113: 1545–1559, 2012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00611.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shimkus KL, Jefferson LS, Gordon BS, Kimball SR. Repressors of mTORC1 act to blunt the anabolic response to feeding in the soleus muscle of a cast-immobilized mouse hindlimb. Physiol Rep 6: e13891, 2018. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kelleher AR, Kimball SR, Dennis MD, Schilder RJ, Jefferson LS. The mTORC1 signaling repressors REDD1/2 are rapidly induced and activation of p70S6K1 by leucine is defective in skeletal muscle of an immobilized rat hindlimb. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 304: E229–E236, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00409.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Richter JD, Sonenberg N. Regulation of cap-dependent translation by eIF4E inhibitory proteins. Nature 433: 477–480, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nature03205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N. eIF4 initiation factors: effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu Rev Biochem 68: 913–963, 1999. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gautsch TA, Anthony JC, Kimball SR, Paul GL, Layman DK, Jefferson LS. Availability of eIF4E regulates skeletal muscle protein synthesis during recovery from exercise. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 274: C406–C414, 1998. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.2.c406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dennis MD, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR. Role of p70S6K1-mediated phosphorylation of eIF4B and PDCD4 proteins in the regulation of protein synthesis. J Biol Chem 287: 42890–42899, 2012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.404822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Showkat M, Beigh MA, Andrabi KI. mTOR signaling in protein translation regulation: implications in cancer genesis and therapeutic interventions. Mol Biol Int 2014: 686984, 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/686984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Le Bacquer O, Combe K, Patrac V, Ingram B, Combaret L, Dardevet D, Montaurier C, Salles J, Giraudet C, Guillet C, Sonenberg N, Boirie Y, Walrand S. 4E-BP1 and 4E-BP2 double knockout mice are protected from aging-associated sarcopenia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 10: 696–709, 2019. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rosa-Caldwell ME, Greene NP. Muscle metabolism and atrophy: let’s talk about sex. Biol Sex Differ 10: 43, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s13293-019-0257-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lang SM, Kazi AA, Hong-Brown L, Lang CH. Delayed recovery of skeletal muscle mass following hindlimb immobilization in mTOR heterozygous mice. PLoS One 7: e38910, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Steiner JL, Pruznak AM, Deiter G, Navaratnarajah M, Kutzler L, Kimball SR, Lang CH. Disruption of genes encoding eIF4E binding proteins-1 and -2 does not alter basal or sepsis-induced changes in skeletal muscle protein synthesis in male or female mice. PLoS One 9: e99582, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yoshizawa F, Mochizuki S, Sugahara K. Differential dose response of mTOR signaling to oral administration of leucine in skeletal muscle and liver of rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 77: 839–842, 2013. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schmidt EK, Clavarino G, Ceppi M, Pierre P. SUnSET, a nonradioactive method to monitor protein synthesis. Nat Methods 6: 275–277, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goodman CA, Mabrey DM, Frey JW, Miu MH, Schmidt EK, Pierre P, Hornberger TA. Novel insights into the regulation of skeletal muscle protein synthesis as revealed by a new nonradioactive in vivo technique. FASEB J 25: 1028–1039, 2011. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-168799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roberson PA, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR. Convergence of signaling pathways in mediating actions of leucine and IGF-1 on mTORC1 in L6 myoblasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 323: C804–C812, 2022. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00183.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aviner R, Geiger T, Elroy-Stein O. PUNCH-P for global translatome profiling: methodology, insights and comparison to other techniques. Translation (Austin) 1: e27516, 2013. doi: 10.4161/trla.27516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Calve S, Witten AJ, Ocken AR, Kinzer-Ursem TL. Incorporation of non-canonical amino acids into the developing murine proteome. Sci Rep 6: 32377, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep32377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Anthony JC, Yoshizawa F, Anthony TG, Vary TC, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR. Leucine stimulates translation initiation in skeletal muscle of postabsorptive rats via a rapamycin-sensitive pathway. J Nutr 130: 2413–2419, 2000. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.10.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Crozier SJ, Kimball SR, Emmert SW, Anthony JC, Jefferson LS. Oral leucine administration stimulates protein synthesis in rat skeletal muscle. J Nutr 135: 376–382, 2005. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.3.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bodine SC. Disuse-induced muscle wasting. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45: 2200–2208, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. You J-S, Anderson GB, Dooley MS, Hornberger TA. The role of mTOR signaling in the regulation of protein synthesis and muscle mass during immobilization in mice. Dis Model Mech 8: 1059–1069, 2015. doi: 10.1242/dmm.019414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Le Bacquer O, Combe K, Montaurier C, Salles J, Giraudet C, Patrac V, Domingues-Faria C, Guillet C, Louche K, Boirie Y, Sonenberg N, Moro C, Walrand S. Muscle metabolic alterations induced by genetic ablation of 4E-BP1 and 4E-BP2 in response to diet-induced obesity. Mol Nutr Food Res 61: 1700128, 2017. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201700128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bodine SC, Baehr LM. Skeletal muscle atrophy and the E3 ubiquitin ligases MuRF1 and MAFbx/atrogin-1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 307: E469–E484, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00204.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Suzuki R, Sato Y, Obeng KA, Suzuki D, Komiya Y, Adachi S-I, Yoshizawa F, Sato Y. Energy metabolism profile of the effects of amino acid treatment on skeletal muscle cells: leucine inhibits glycolysis of myotubes. Nutrition 77: 110794, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2020.110794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Koyama S, Hata S, Witt CC, Ono Y, Lerche S, Ojima K, Chiba T, Doi N, Kitamura F, Tanaka K, Abe K, Witt SH, Rybin V, Gasch A, Franz T, Labeit S, Sorimachi H. Muscle RING-finger protein-1 (MuRF1) as a connector of muscle energy metabolism and protein synthesis. J Mol Biol 376: 1224–1236, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hirner S, Krohne C, Schuster A, Hoffmann S, Witt S, Erber R, Sticht C, Gasch A, Labeit S, Labeit D. MuRF1-dependent regulation of systemic carbohydrate metabolism as revealed from transgenic mouse studies. J Mol Biol 379: 666–677, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and Supplemental Table S1: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21187603.v1.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.