Abstract

Chlamydia organisms are obligate intracellular bacterial pathogens responsible for a range of human diseases. Persistent infection or reinfection with Chlamydia trachomatis leads to scarring of ocular or genital tissues, and Chlamydia pneumoniae infection is associated with the development of atherosclerosis. We demonstrate that C. trachomatis and C. pneumoniae infection in vitro elicits the externalization of the lipid phosphatidylserine on the surface of human epithelial, endothelial, granulocytic, and monocytic cells. Phosphatidylserine externalization is associated with cellular development, differentiation, and death. Infection-induced phosphatidylserine externalization was immediate, transient, calcium dependent, and infectious dose dependent and was unaffected by a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor. Chlamydia-infected cells accelerated plasma clotting and increased the macrophage phagocytosis of infected cells that was phosphatidylserine dependent. The rapid externalization of phosphatidylserine by infected cells may be an important factor in the pathogenesis of chlamydial infections.

Trachoma-causing strains of Chlamydia trachomatis are endemic in many developing nations and are a leading cause of preventable blindness worldwide (57). In the United States, infection with sexually transmitted strains of C. trachomatis is the most common infectious disease reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state health departments, estimated at 4 million to 5 million new cases annually (11). Approximately 60% of adults worldwide are seropositive to Chlamydia pneumoniae (28), and infection is associated with atherosclerosis and is a risk factor for myocardial infarction (54). Chlamydial disease requires chronic infection or reinfection, implicating the immune system in pathogenesis (27).

Natural infections begin with chlamydiae binding to epithelial cells, although macrophages, endothelial, and smooth muscle cells can be infected (24). Dissemination of chlamydiae from the mucosal portal of entry to distal sites of infection, such as lymph nodes or arteries, is thought to be mediated by macrophages. Bacteria are internalized and replicate within cells in a specialized vacuole termed the inclusion. In vitro, Chlamydia cells induce their uptake (40) and elicit secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines by infected epithelial cells (48).

Phosphatidylserine (PS), a lipid sequestered to the cytofacial plasma membrane (PM) leaflet, is externalized to the outer leaflet when cells enter apoptotic states. Within hours, influenza (22) or Legionella pneumophila (23) infections increase host cell PS exposure, representing an early host response to intracellular parasites. Externalized PS can be detected using annexin V, a cytoplasmic protein that binds PS and other acidic phospholipids in the presence of millimolar concentrations of calcium (62). Two- to 100-fold enhancements in mean annexin V-dependent fluorescence are commonly obtained (2, 7, 8, 38). Externalized PS has roles in physiologic processes, including coagulation, phagocytosis, and complement activation (14, 17, 65). Externalized PS on platelets (70), endothelial cells (7, 10), and monocytes/macrophages (2) serves to accelerate clotting reactions. Procoagulant enzyme complexes form on PS-rich domains, accelerating thrombin activation and fibrin generation (14). PS signals for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages (56) via an uncharacterized receptor, among which CD36 is a candidate (18).

Associated with the early stages of apoptosis, PS externalization can be accompanied by increased PM permeability and caspase activation. The relationship between infection with Chlamydia and apoptosis is apparently developmental stage specific, with induction of proapoptotic (25, 42) and antiapoptotic (19) phenotypes previously described.

We tested whether Chlamydia would generate a PS response by infecting epithelial, endothelial, granulocytic, and monocytic cells. C. trachomatis or C. pneumoniae infection led to every cell type tested rapidly and transiently exposing PS on their PMs without an increase in PM permeability. PS externalization was dose dependent and extracellular calcium dependent but was unaffected by pretreatment of cells with a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor shown to inhibit induced PS exposure (61, 69). Externalized PS was functional as Chlamydia-infected cells accelerated plasma clot formation and were phagocytosed by macrophages in a PS-dependent manner.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Annexin V-biotin was purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, Calif.), and recombinant annexin V, streptavidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (SA-FITC), and SA-phycoerythrin (SA-PE) were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.). Recombinant annexin V-green fluorescent protein (V-GFP) (16) was a kind gift from Joel Ernst, San Francisco General Hospital and University of California—San Francisco, San Francisco, Calif. Percoll was purchased from Pharmacia (Piscataway, N.J.), fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD), and actinomycin D were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, Calif.), and Russell's viper venom (RVV), Sigmacote, cephalin, PS, and phosphatidylcholine (PC) dissolved in chloroform were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.).

Bacteria and cells.

C. trachomatis serovar L2 (434/Bu/L2) and C. pneumoniae strain CWL-029 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). HeLa, THP-1, and L929 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Human coronary artery endothelial (HCAE) cells were purchased from Clonetics (San Diego, Calif.). HCAE cells were maintained in endothelium growth medium-MV per manufacturer's instructions. Neutrophils (>95% pure) were obtained from citrated whole blood by dextran sedimentation, followed by fractionation on a discontinuous Percoll gradient as described previously (55). Monocytes were obtained from buffy coats by adhesion onto glass or plastic in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM), and nonadherent cells were removed after 1 h by gentle washing. Citrated whole human blood was obtained from the Alameda County Chapter of the American Red Cross (Oakland, Calif.). Work involving human samples was approved by the University of California—Berkeley Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Cell culture and infection.

HeLa, THP-1, and L929 cells were grown in IMDM (Gibco, Gaithersburg, Md.) plus 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, Utah) plus 50 μg of vancomycin HCl (Sigma)/ml. Plastic tissue cultureware was used to maintain cells for assays, and glass spinner flasks were used to grow HeLa cells for C. trachomatis serovar biovar LGV propagation. HEp2 cells in six-well plastic tissue culture plates (Costar, Corning, N.Y.) were used for C. pneumoniae propagation. Macrophages were maintained in X-Vivo-10 medium (Biowhittaker, Walkersville, Md.) supplemented with 10% human AB serum (Sigma) and 25 μg of vancomycin/ml. HeLa cells were aspirated and overlaid with 1 ml (per 25 cm2) of IMDM containing 2 inclusion forming units (IFU) of C. trachomatis or C. pneumoniae placed on a rotating shaker, and infection was allowed to proceed for 2 h at room temperature. Inocula were prepared by brief sonication of bacteria in ice-cold unsupplemented endothelial cell basal medium. THP-1 and HCAE cells were overlaid with the inocula and returned to the 37°C incubator. Inocula for HCAE cells were prepared in unsupplemented endothelial cell basal medium (Clonetics). Uninfected cells were mock infected by using unsupplemented medium lacking chlamydiae and subjecting the cells to the same handling procedures as infected cultures.

Fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry.

For fluorescence microscopy, 100,000 HeLa cells were plated overnight in 24-well tissue culture plates (Costar) with 12-mm-diameter glass coverslips. The next day, inocula were prepared in unsupplemented IMDM as was described. Infections were allowed to proceed for 1 to 2 h, and then the inoculum was removed. Wells were washed once with IMDM, aspirated, and then overlaid with annexin V-GFP (0.35 ng/ml) or annexin V-biotin (50 ng/ml) diluted in annexin V binding buffer (AVB; 140 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 2.5 mM CaCl2). After 10 min, the wells were aspirated and washed twice with AVB and then were fixed with ice-cold 2% paraformaldehyde–0.2% glutaraldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min on ice. The wells were washed, covered, and incubated at room temperature for 45 min with a 0.0005% Evans blue (Sigma) solution in PBS. The coverslips were mounted using ProLong antifade (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.), and simultaneous green and red fluorescence images (original magnification, ×400) were taken using an Olympus camera mounted on an Axiophot (Zeiss) fluorescence microscope. For blocking experiments, inocula (0.8 IFU/ml) resuspended in ice-cold AVB were incubated with recombinant annexin V or fatty acid-free BSA (50 ng/ml) for 30 min on ice. After 10-fold dilution with ice-cold AVB, bacteria were pelleted by ultracentrifugation (18,000 × g) at 4°C. Bacteria were resuspended in AVB by sonication, and 0.25 ml was applied to each well. For the PS-positive control wells, cells were pretreated with 1 μM staurosporine for 1 h at room temperature and then were aspirated and washed twice with ice-cold AVB. Either recombinant annexin V or BSA (at 50 ng/ml) in ice-cold AVB was added to the wells and allowed to bind for 30 min on ice. Wells were aspirated and washed twice with AVB, and the monolayers were probed with 0.35 ng of annexin V-GFP/ml, counterstained, and fixed as described above.

Suspension cells were prepared for flow cytometric analysis as described previously (58). Adherent cells were prepared for flow cytometric analysis of annexin V binding as described previously (30). After infection and removal of the inoculum, cells were overlaid with IMDM (HeLa, THP-1) or unsupplemented ECV (HCAE) containing 0.3 (HeLa, THP-1, L929) or 1.0 (HCAE) μg of annexin V-biotin/ml for 5 min at room temperature. A 1-ml volume of annexin V-biotin diluted in medium was used for every 106 suspension of cells or every 25 cm2 of tissue flask area. Annexin V-GFP was diluted to 3 μg/ml in AVB immediately before use. The medium was aspirated and the cells were washed twice with AVB. Cells were then overlaid with 1 ml (per 25 cm2) of AVB plus 0.5 μg of SA-FITC or SA-PE/ml and 1 μg of 7-AAD/ml as a cell viability indicator (58). Cell monolayers were scraped with a plastic scraper, filtered through 35-μm-pore-size mesh into a 12- by 75-mm polystyrene tube (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.), and placed on ice, covered, for 30 min. Cells were centrifuged at 400 × g in a 4°C prechilled rotor and washed twice with ice-cold AVB plus 10 μg of actinomycin D/ml. Cells were suspended in ice-cold 2% paraformaldehyde–0.2% glutaraldehyde in calcium- and magnesium-free PBS plus 10 μg of actinomycin D/ml before flow cytometry. Cells stained with annexin V-GFP were fixed in the presence of 5 mM calcium chloride. Neutrophil preparations were stained for expression of the granulocyte marker CD15 by first blocking on ice with normal rabbit serum (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, N.Y.), washing, and then adding mouse anti-human CD15 or an isotype control (3.3 μg/ml; Pharmingen), washing, and staining with rat anti-mouse immunoglobulin heavy chain-FITC (1:500 dilution; Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, Ala.). Gated cells were >95% CD15 positive (data not shown). Cells were evaluated on a Coulter EPICS XL flow cytometer (Hialeah, Fla.).

Liposome preparation.

PS was dissolved in chloroform to 10 mg/ml. The PS-to-PC ratios was 30:70. Lipids were dried under nitrogen, PBS was added, and then lipids were sonicated on ice for a stock concentration of 1.0 mM total lipid. Liposomes were stored on ice and used within 1 h of preparation.

Plasma clotting assay.

The method used for the plasma clotting assay was adapted from that described by Casciola-Rosen et al. (10), but we used 1.25 ng of RVV per reaction mixture instead of 12.5 ng. Platelet-poor plasma was prepared by centrifugation of citrated blood for 10 min at 400 × g and drawing the upper two-thirds for coagulation studies. PPP was stored at −70°C. Clotting was initiated by adding calcium to the reaction mixture prewarmed in a 37°C water bath. Siliconized 13- by 100-mm borosilicon glass tubes were visually examined every 10 s for clot formation. The endpoint of the assay was reached when a firm fibrin clot formed.

Phagocytosis assays.

The method used for the phagocytosis assay was described by Fadok et al. (18). Macrophages were plated as described onto glass coverslips in 24-well plates, and medium was changed every 3 day. On day 5 or 6, UV-sterilized glucan (Sigma) was added to the medium to a final concentration of 25 μg/ml. After two further days of culture, the cells were washed twice in unsupplemented medium before addition of inhibitors or target cells. Liposomes were added to a final concentration of 0.1 mM total lipid, and RGDS peptide was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. Neutrophils were added at the indicated ratios in X-Vivo-10 medium and cocultured at 37°C for 2 h. Wells were washed twice with medium, were washed once with PBS, were fixed, and then were esterase stained and hematoxylin counterstained (Sigma) for counting. Target cells were scored as phagocytosed if 50% or more of a blue target cell fell within a macrophage PM border. The phagocytic index was derived as follows: the percent phagocytosing macrophages were multiplied by the average number of neutrophils ingested (18). Neutrophils were scored as ingested if 50% or more were within a macrophage border. Between 400 and 500 macrophages were counted per sample.

RESULTS

Chlamydial infection induces host cell PS exposure.

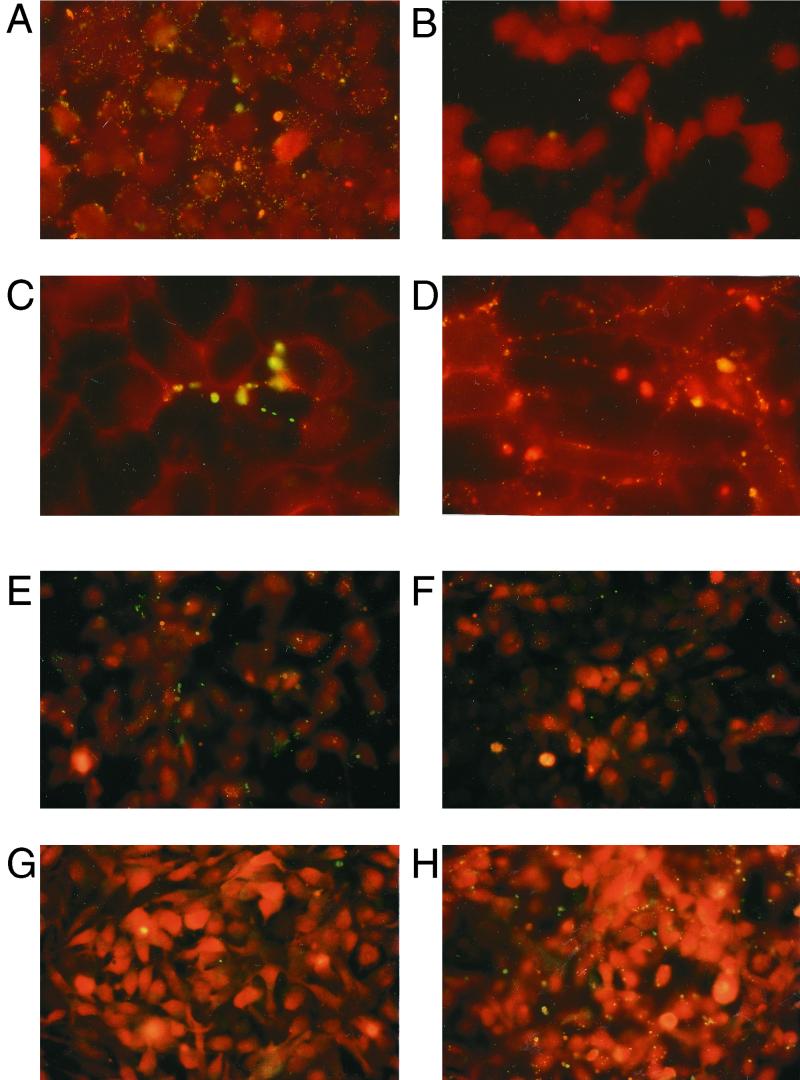

Annexin V was used to detect PS (62) in human cells after infection with C. trachomatis or C. pneumoniae. Infected HeLa cells (Fig. 1A) acquired a bright green punctate staining pattern localized to the PM, while uninfected cells did not stain (Fig. 1B). Cells treated with the kinase inhibitor staurosporine externalized phosphatidylserine (Fig. 1C). The morphology of the annexin V staining patterns of staurosporine-treated and Chlamydia-infected cells (Fig. 1D) appeared to be dissimilar. Staurosporine-treated cells tended to generate stained areas localized to one side of the cell, while infected cells displayed a more even, punctate staining over the entire cell surface.

FIG. 1.

Fluorescence micrographs of HeLa cells binding the PS-specific probe annexin V after acute infection with C. trachomatis or treatment with staurosporine. Infected cells probed with annexin V (A) stained bright green compared to uninfected cells (B). HeLa cells cultured with 1 μM staurosporine (C) or C. trachomatis (D) exposed PS on their plasma membranes. C. trachomatis cells were pretreated with 50 μg of unlabeled recombinant annexin V/ml or BSA and were used to infect HeLa cells. After washing the infected cell monolayers and staining with annexin V-GFP, no significant change in PS externalization (as green fluorescence) is seen between cells infected with C. trachomatis pretreated with annexin V (E) or BSA (F). The concentration of unlabeled annexin V used (E) was adequate to block binding of annexin V-GFP (100 ng/ml), as staurosporine-treated cells subsequently incubated with unlabeled annexin V (G) followed by annexin V-GFP staining showed no green fluorescent staining compared to staurosporine-treated cells incubated with BSA and then stained with annexin V-GFP (H). Cells in panels A through D were probed with annexin V-biotin and SA-FITC; all other cells were probed with annexin V-GFP. Cells were counterstained with Evans blue (background red fluorescence). A 40× objective (A, B, E, F, G, and H) and a 100× objective (C and D) were used to record images.

Whether the cell-associated PS we detected on infected cells was passively or actively acquired was determined. Chlamydiae were purified from infected host cells, and it was possible that the PS we detected originated from the prior host and not the newly infected cell itself. If PS was being passively transferred from the inoculum, then preincubating the inoculum with excess unlabeled annexin V should have reduced annexin V-GFP binding and fluorescent cell staining after infection. Pretreating infectious chlamydial elementary bodies (EB) with unlabeled annexin V did not affect annexin V-GFP staining (Fig. 1E), as BSA-treated EB (Fig. 1F) induced similar staining after infection. Unlabeled annexin V was competent to bind PS, as it blocked annexin V-GFP binding to staurosporine-treated cells (Fig. 1G). We concluded that the host cell, not the inoculum, contained the PS detected by annexin V. This prompted us to investigate the contribution of the host cell towards PS externalization during infection.

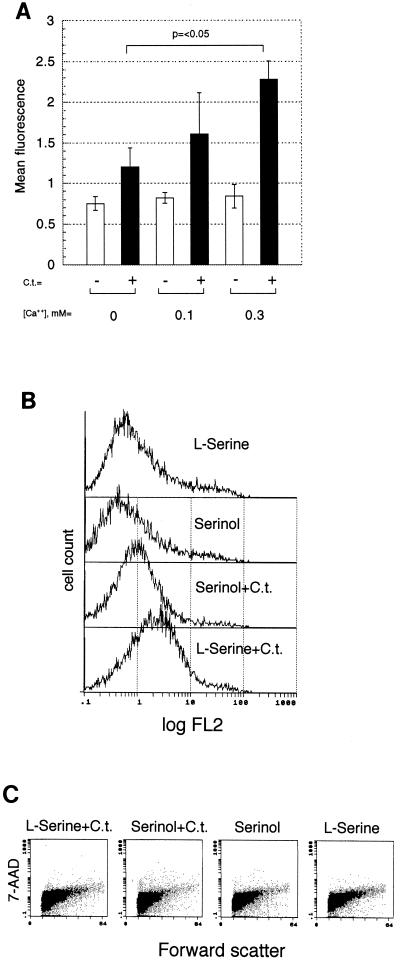

PS externalization as well as bidirectional movement of phospholipids across the PM bilayer is proportional to the calcium flux across the PM (8). If the infected host cell provides the PS bound by annexin V, then cells cultured in varied concentrations of calcium and infected with Chlamydia should externalize different amounts of PS. Cells cultured with increasing amounts of calcium, followed by infection with C. trachomatis, externalized more PS (Fig. 2A), with a twofold difference (P < 0.05) between cells cultured with 0 and 0.3 mM calcium. Binding of C. trachomatis biovar LGV was modestly decreased by omitting calcium (zero to 20% reduction; 37, 59); therefore, its absence was unlikely to affect PS induction by decreasing bacterial binding.

FIG. 2.

Detection of PS during Chlamydia infection under conditions that influence cellular PS transport and metabolism. (A) Effect of extracellular calcium concentrations upon PS externalization in uninfected HeLa cells (−) and in HeLa cells infected with 1 IFU of Chlamydia/cell (+) and stained with annexin V-GFP. (B) PS response of HeLa cells pretreated with the PS synthesis inhibitor serinol upon infection with Chlamydia. Shown are flow cytometric histograms of HeLa cells cultured with the PS synthesis inhibitor serinol and infected with 0.5 IFU of C. trachomatis/cell (Serinol+C.t.), infected cells cultured with l-serine (l-Serine+C.t.), and uninfected cells cultured in serinol or l-serine. Cells were stained with annexin V-biotin and SA-PE. (C) Flow cytometric dot plots of data of forward light scatter versus 7-AAD uptake of cells (B) demonstrate no significant changes in cell size or viability induced by culturing HeLa cells for 4 days with 2 mM serinol or l-serine or by acute infection with 2 IFU of C. trachomatis per cell.

The infected host's contribution to PS exposure was further assessed using serinol, a serine analog, to inhibit the synthesis of PS (44). Serinol-treated cells should externalize less PS after chlamydial infection if the host cell is the PS source. Serinol-treated cells externalized 2.5-fold less PS than l-serine-treated cells after infection (Fig. 2B). Using the membrane impermeant fluorescent dye 7-AAD as a probe during flow cytometry to distinguish between live and dead cells (30, 58), no adverse effects of the serinol treatment upon cell cultures were noted (Fig. 2C). These data (Fig. 1 and 2) demonstrate that host cells externalize PS upon infection with Chlamydia.

Chlamydial binding is required for induction of host cell PS externalization.

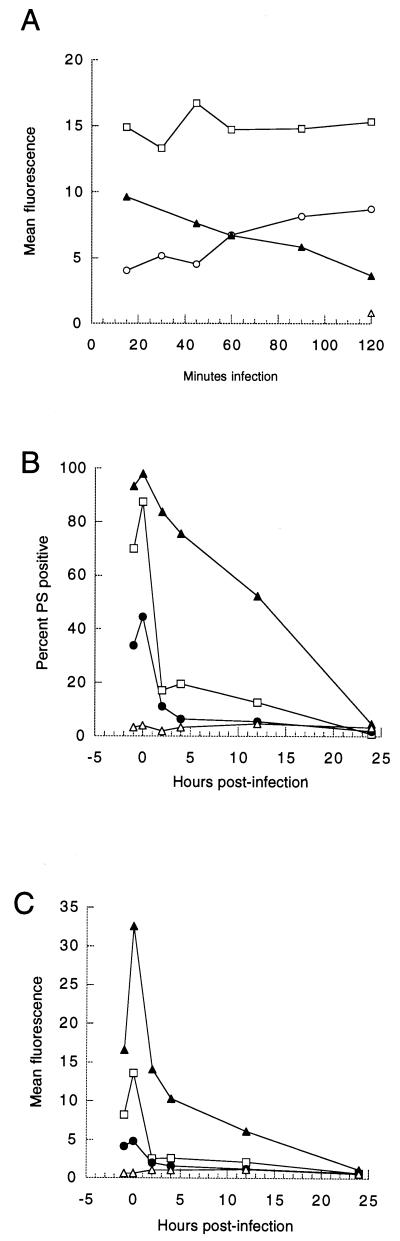

Inhibiting chlamydial protein synthesis with chloramphenicol did not affect peak fluorescence values or kinetics of PS exposure over a 48-h assay period (Fig. 3A). A second peak of PS exposure was sometimes noted in other chloramphenicol-treated cocultures (data not shown). Mild heating of EB abolishes their ability to infect and reduces their ability to bind host cells (40). Heated EB provoked less HeLa cell PS externalization (Fig. 3B). Pellets and supernatants from the high-speed centrifugation of heated EB were tested to induce PS exposure, and all activity was restricted to the pellet fraction (data not shown). It has been shown previously that excess heparin blocks chlamydial binding and entry, with the analog chondroitin sulfate having no effect (68). If Chlamydia binding triggered host PS exposure, then added heparin should have blocked PS externalization. Heparin treatment abolished Chlamydia-induced PS exposure (Fig. 3C). This suggests that chlamydial binding, not a soluble component, is minimally required to elicit host cell PS exposure.

FIG. 3.

Kinetics of host PS exposure by treatments affecting chlamydial protein synthesis and adhesion. (A) Effect of chloramphenicol upon infected host cell PS exposure. HeLa cells treated with chloramphenicol (50 μg/ml) before, during, and after pulse inoculation with 2 IFU of C. trachomatis per cell (squares) were compared to infected cells without chloramphenicol (triangles) and uninfected cells with (circles) and without (crosses) chloramphenicol over a 48-h period. Data are representative of three experiments. Data are from 10,000 gated events gathered by flow cytometry per time point. (B) PS externalization in HeLa cells infected with heat-treated bacteria (60°C, 10 min; squares), untreated bacteria (triangles), or buffer alone (circles). Data from 10,000 events per time point were gathered by flow cytom- etry at −1, 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h postinfection. (C) Effect of pretreating host cells with heparin upon Chlamydia-induced PS externalization. Flow cytometric histograms of C. trachomatis-infected HeLa cells pretreated with 0.5 mg of heparin/ml (Heparin+C.t.) or with 0.5 mg of chondroitin sulfate/ml (Chondroitin+C.t.) and uninfected treated cells are shown. Data represent 20,000 events gathered by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with annexin V-biotin and SA-FITC.

Agents that damage cell structures (e.g., ethanol) or bind receptors of the Fas-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family elicit PS exposure (66). A final concentration of 100 μM carboxybenzyl-valine-alanine-aspartic acid-fluoromethylketone (z-VAD-fmk), a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor, almost completely suppresses PS externalization in leukocytes treated with etoposide or anti-Fas antibody (61, 69). A final concentration of 100 μM z-VAD-fmk modestly lowered PS externalization in THP-1 cells inoculated with C. trachomatis compared to that in ethanol-treated cells (Table 1). Similarly, pretreatment of HeLa cells with 100 μM z-VAD-fmk or aspartic acid-glutamine-valanine-aspartic acid-chloromethylketone (DEVD-cho; 15 μM) failed to prevent C. trachomatis-mediated PS externalization (data not shown). Thus, the mechanism of Chlamydia-induced PS exposure differs significantly from the ones used in response to Fas-TNF receptor ligation or DNA damaging agents in that it does not require caspase activation, although the presence of extracellular calcium does maximize PS externalization.

TABLE 1.

Effect of a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor on C. trachomatis-induced PS externalization

| PS agonist | Mean fluorescencea

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | z-VAD-fmkb | % Decreasec | |

| None | 2.25 | 2.22 | 1.3 |

| 5% Ethanold | 3.01 | 1.92 | 36.2 |

| C. trachomatis | 5.10 | 4.59 | 10 |

Mean fluorescence data of 50,000 gated events gathered by flow cytometry.

THP-1 cells were pretreated with 100 μM z-VAD-fmk or dimethyl sulfoxide (medium) for 1 h at 37°C before addition of the PS agonist.

Percent decrease = [(medium fluorescence) − (z-VAD-fmk fluorescence)]/(medium fluorescence) × 100.

Cells were incubated with 5% ethanol or 1 IFU of C. trachomatis/ml for 1 h at 37°C in the presence or absence of z-VAD-fmk. Uninfected cells were cultured in unsupplemented IMDM.

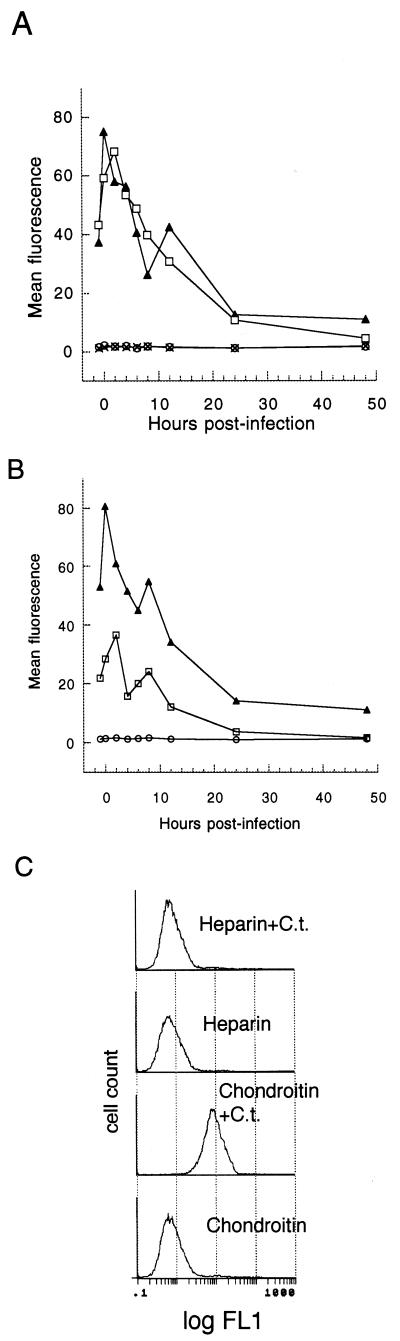

Dose response and kinetics of PS exposure by Chlamydia-infected HeLa cells.

Both the amplitude and rate of PS externalization were influenced by the inoculum dose. In Fig. 4A, cells continuously infected with 2 IFU of Chlamydia/cell increasingly externalized more PS over the assay. Cells infected with 12.5 IFU/cell displayed a steady level of PS exposure throughout the infection period. Interestingly, cells treated with the highest dose, 50 IFU/cell, began to lose detectable PS 30 min after inoculum addition; after 2 h of continuous infection, PS was near or at baseline uninfected-cell levels (n = 3 experiments). The mechanism behind cellular PS loss is not known; this may be a consequence of the cell reinternalizing PS-rich PM as the assay was conducted at 23 to 25°C, which permits attachment and EB endocytosis (40). Alternatively, PS loss may occur via the shedding of cell membranes that are enriched in the supernatants of cells treated with chemical inducers of apoptosis (3).

FIG. 4.

Kinetic dose-response relationship between infectious bacterial titer and PS exposure in HeLa cells infected with C. trachomatis. (A) Annexin V-dependent fluorescence of HeLa cells undergoing continuous short-term infection with 2 (circles), 12.5 (squares), 50 (closed triangles), or zero (open triangle) IFU of C. trachomatis per cell over a 2-h period. Doses of 50 IFU or more per cell over the 2-h period led to a decline in annexin V binding in three of three assays. (B and C) Relationship between subsaturating doses of infectious C. trachomatis and PS exposure by bacterium-pulsed HeLa cells. The percentage of HeLa cells binding annexin V (B) and mean fluorescence data (C) are shown. Data representing doses of 2 (closed triangles), 0.67 (squares), and 0.22 (circles) IFU per cell and buffer control (open triangles) are shown. Cells were processed for flow cytometry and mean fluorescence data are shown. Cells were stained with annexin V-GFP (A) or with annexin V-biotin and SA-FITC (B and C).

A concentration of 2 IFU per cell triggered PS exposure while being subsaturating with respect to the host cell's ability to externalize PS. Therefore, this dose level or less was used in the majority of experiments. Using the suspension cell variant HeLa S3 to facilitate rapid cell processing, annexin V binding occurred 5 min after C. trachomatis inoculation (data not shown). We achieved maximal PS externalization in HeLa cells by using an inoculum of 12.5 IFU of C. trachomatis per cell (Fig. 4A) and routinely obtained 60 to 100% PS-positive cells using 2 IFUs/cell. In comparison, Listeria monocytogenes infections require significantly larger amounts of bacteria (multiplicity of infection, 10 to 50) to elicit the same percentage of cells that externalize PS (23). Both infectious and noninfectious Chlamydia cells comprise the particles in an inocula, with 10 to 40% in a typical preparation estimated as being infectious. We do not know the contributions infectious and noninfectious particles make towards PS externalization as we have not demonstrated a requirement for chlamydial infectivity per se with PS externalization.

The inoculum size influenced PS disappearance rates. Downward titration of bacteria resulted in lower PS exposure by fewer cells (Fig. 4B and C). Externalized PS had a half-life of 12 h at 2 IFU per HeLa cell; 0.67 and 0.22 IFU per cell yielded a half-life of 1.5 h (as percent PS-positive cells; Fig. 4B). Cells inoculated with 2 IFU/cell showed significant annexin V binding after inoculum withdrawal (at 0 h postinfection) and beyond, while inocula of 0.67 and 0.22 IFU/cell resulted in virtually total and immediate PS disappearance after withdrawal, measured either as percent PS-positive cells or mean fluorescence. The large differences in half-lives may reflect saturation of a host component(s) responsible for lipid metabolism after inoculation with Chlamydia.

Twenty-four hours postinfection, light refraction (side scatter) of infected HeLa cells increased as measured by flow cytometry (data not shown), due to chlamydial organisms growing within the cells. Using 7-AAD, infected cells demonstrated no significant increases in PM permeability immediately or 24 h postinfection (data not shown). A second peak of PS exposure appeared in other kinetic determinations (four of four experiments), appearing between 6 and 12 h postinfection. The mechanism underlying the second peak is unknown; it may represent a response to a preformed chlamydial product(s), as both untreated and chloramphenicol-treated bacteria (incapable of metabolic activity) elicit the second PS peak.

Host cell PS exposure induced by Chlamydia infection is transient and reinducible.

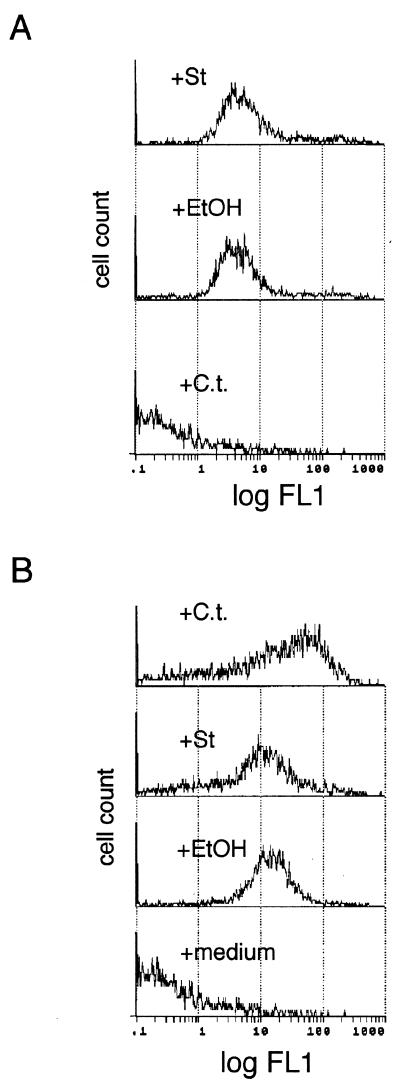

PS exposure depended on the continuous presence of Chlamydia since inoculum removal led to PS disappearance (Fig. 3A and 4B). The transient nature of Chlamydia-mediated PS exposure appeared to be a novel finding, and we tested whether staurosporine- and ethanol-induced PS exposure was also transient. Twenty-four hours after stimulus withdrawal, staurosporine- and ethanol-treated cells still externalized PS while Chlamydia-infected cells were negative (Fig. 5A). We next examined whether loss of externalized PS by infected cells was reversible. Infected cells treated with either C. trachomatis, ethanol, or staurosporine all reexternalized PS (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that host cell entry and/or binding by Chlamydia is necessary to induce PS exposure, and the host PS response to subsequent agonists is not blunted by a concurrent infection with Chlamydia.

FIG. 5.

The transient, reinducible nature of Chlamydia-induced PS externalization. (A) Flow cytometric histograms of C. trachomatis-infected cells (+C.t.), staurosporine-treated cells (+St), or ethanol-treated cells (+EtOH) stained for PS 24 h after agonist withdrawal. Data represent 3,500 events. (B) Reinduction of PS exposure in infected cells. Twenty-four hours postinfection, HeLa cells were pulsed with either 2 IFU of C. trachomatis/cell (+C.t.), 1 μM staurosporine (+St), 5% ethanol (+EtOH), or medium for 2 h and then PS exposure was measured. Cells were stained with annexin V-biotin and SA-FITC.

C. pneumoniae infection induces PS exposure in arterial endothelial cells and in epithelial cells.

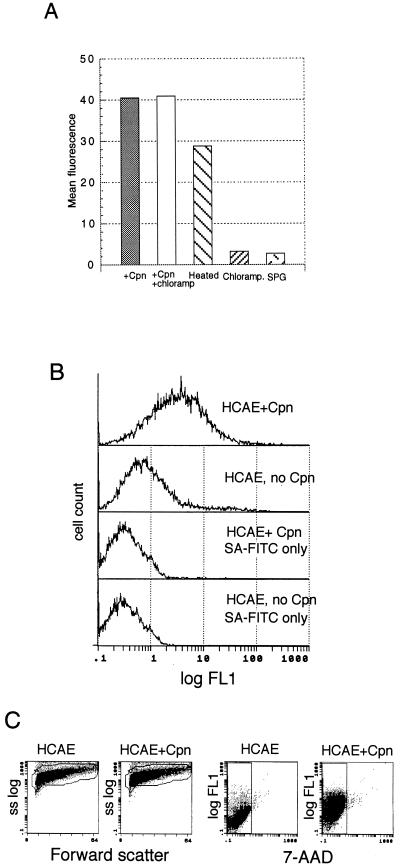

C. pneumoniae accesses vascular cells; therefore, the bacterium encounters epithelial cells at least once during infection. We tested whether C. pneumoniae elicits PS exposure in HeLa epithelial cells. Cells externalized PS in response to C. pneumoniae (Fig. 6A), and paralleling the above results with C. trachomatis, chloramphenicol left PS exposure unaffected, but mildly heating the inoculum lowered mean fluorescence (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Induction of PS exposure by infectious C. pneumoniae. (A) Mean flow cytometric data of HeLa epithelial cells infected with C. pneumoniae. HeLa cells were inoculated with the following: infectious C. pneumoniae at 1 IFU per cell (+Cpn), C. pneumoniae and 50 μg of chloramphenicol/ml (+Cpn+chloramp), C. pneumoniae cells that were heated at 60°C for 10 min (Heated), 50 μg of chloramphenicol/ml (Chloramp), or a volume of sucrose buffer equal to that used for the infectious inoculum in medium (SPG). (B) Flow cytometric histograms of HCAE cells infected with C. pneumoniae and stained for PS. HCAE cells were pulsed with bacteria and then stained with annexin V and second-step reagent (HCAE+Cpn) or with second-step reagent alone (HCAE + Cpn, SA-FITC only); uninfected cells were stained with both reagents (HCAE, no Cpn) or with second-step reagent alone (“HCAE, no Cpn SA-FITC only”). (C) Flow cytometric dot plots of forward light scatter versus side scatter (ss log) and annexin V-biotin and SA-FITC staining versus 7-AAD uptake of HCAE cells from panel B. Infected HCAE cells (HCAE+Cpn) did not demonstrate significant changes in cell size and granularity (Forward Scatter) or PM permeability (7-AAD fluorescence) compared to uninfected controls. Data represent 6,000 gated events.

Externalized PS accelerates coagulation and generates end products, such as thrombin, that contribute to the development of atherosclerotic disease (31). Viable C. pneumoniae cells have been recovered from atherosclerotic plaques (36, 47), and antibodies to C. pneumoniae are associated with acute myocardial infarctions (54). We tested whether C. pneumoniae cells elicit PS externalization in HCAE cells, and infected HCAE cells (Fig. 6B) did externalize PS.

Human monocytes and neutrophils externalize PS in response to inoculation with Chlamydia.

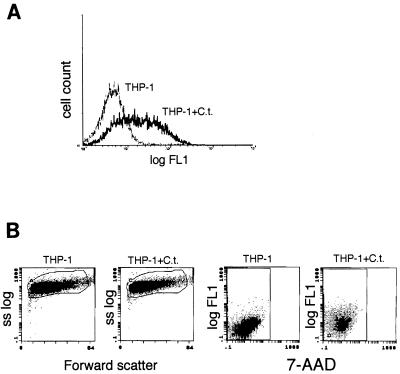

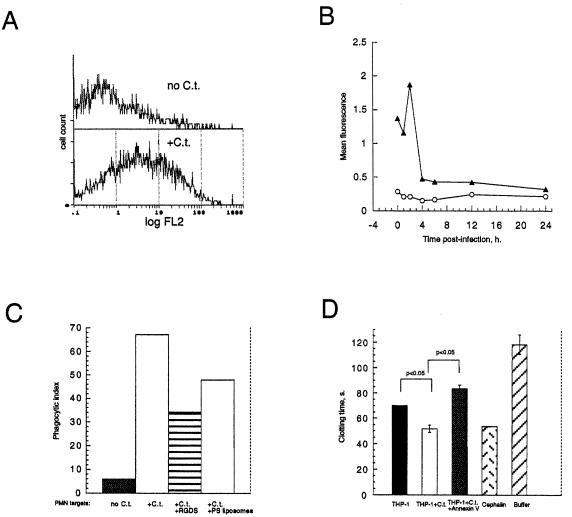

Intense inflammation accompanies acute Chlamydia infections, with neutrophils and monocytes accumulating at the infection site (35). Since infected epithelial and endothelial cells externalize PS, we tested whether this would occur in macrophages and neutrophils, as both cell types come into contact with the bacteria. Infected THP-1 promonocytes (Fig. 7A) externalized PS, as did infected neutrophils (Fig. 8A). PS externalization kinetics of inoculated neutrophils (Fig. 8B) revealed a pattern similar to that of HeLa cells (Fig. 3A and 4C), but no second PS peak was seen.

FIG. 7.

PS exposure and viability of THP-1 promonocytes infected with C. trachomatis. (A) Flow cytometric histograms of THP-1 cells stained for PS externalization that were either infected with C. trachomatis (THP-1+C.t.) or uninfected (THP-1). Data represent 10,000 events. (B) Flow cytometric dot plots of forward scatter versus side scatter (ss log) and annexin V-biotin plus SA-FITC versus 7-AAD staining of THP-1 cells from panel A demonstrate that cell size and granularity (forward scatter) and PM permeability (7-AAD fluorescence) of C. trachomatis-infected cells (THP-1+C.t.) do not change compared to those of uninfected THP-1 cells.

FIG. 8.

(A) PS exposure in human neutrophils inoculated with C. trachomatis. Shown are flow cytometric histograms of uninfected neutrophils (no C.t.) and neutrophils inoculated with C. trachomatis (+C.t.). Data represent 5,000 gated events. (B) Kinetic assay of PS exposure by neutrophils that were either inoculated with C. trachomatis (triangles) or left uninfected (circles). PS was detected by flow cytometry of annexin-V biotin and SA-PE-stained neutrophils (A and B). (C) Macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of C. trachomatis-inoculated neutrophils can be inhibited by PS liposomes. Neutrophils (at a ratio of five neutrophils to one HMDM) that were inoculated (+C.t.) or mock infected (no C.t.) were added to wells containing RGDS peptide or 0.1 mM liposomes. RGDS peptides and PS liposomes were added 30 min prior to neutrophil addition and remained during the coculture period. As described in Materials and Methods, 400 to 500 macrophages per sample were counted. (D) Chlamydia-infected cells are procoagulant, and acquired procoagulant activity is dependent upon exposed PS. THP-1 cells inoculated with C. trachomatis (THP-1+C.t.) significantly accelerated clotting over uninfected THP-1 cells (THP-1). Addition of the PS-binding protein annexin V abrogated enhanced coagulant activity in infected cells (THP-1+C.t.+Annexin V). The molar ratio of annexin V to calcium was 1:4,000, making it unlikely that annexin V exerted its anticoagulant effect by sequestering calcium. Assay range response was indicated by reactions run with cephalin as a positive clotting control or with added buffer only. Data are mean clotting times ± standard deviation of triplicates. Data are representative of three experiments.

Externalized PS on Chlamydia-infected neutrophils enhances their phagocytosis by HMDMs.

Since neutrophils are among the first leukocytes to encounter Chlamydia cells during acute infection (35) and since neutrophils externalize PS when inoculated (Fig. 7A), we tested whether PS on neutrophils would augment their uptake by human monocyte-derived macrophages (HMDMs). Infected neutrophils (Fig. 8C) were phagocytosed by glucan-stimulated HMDMs. PS-dependent phagocytosis is upregulated in HMDMs by including β-glucan, a glucose polymer, in the culture medium (18). Glucan-stimulated HMDMs recognized Chlamydia-inoculated neutrophils through a PS-dependent mechanism, as PS liposomes (Fig. 8C) reduced phagocytosis.

PS on Chlamydia-infected cells accelerates plasma clotting.

Activated monocytes/macrophages express tissue factor (TF) enzyme, which is involved in initiating coagulation (50), and we tested whether PS on C. trachomatis-inoculated THP-1 cells would accelerate clot formation in a plasma-clotting assay. Infected THP-1 cells accelerated clotting in platelet-poor plasma, and recombinant annexin V abolished enhancing activity (Fig. 8D). The clotting activity present in uninfected THP-1 cells was likely due to basal TF expression (41).

DISCUSSION

Eukaryotic cells externalize PS while undergoing death, differentiation (67), and infection by influenza virus (21) and L. pneumophila (23). Here, we show that infection of human cells with the obligate intracellular bacterium Chlamydia elicits PS exposure. While induction of maximal PS externalization requires extracellular calcium, Chlamydia-induced PS exposure differs significantly from those induced by chemical agents or antibodies to the Fas-TNF receptor family. First, Chlamydia cells immediately induced PS exposure (<5 min), whereas staurosporine or ethanol required 1 to 2 h to elicit PS. Second, Chlamydia-induced PS exposure was transient; other inducers initiated a sustained PS exposure after stimulus withdrawal. Third, Chlamydia-induced PS exposure was unaffected by a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor which represses PS exposure mediated by Fas-TNF receptor ligation or DNA-damaging agents. These findings demonstrate the unique nature of PS exposure elicited by Chlamydia.

Our results differ from those observed in monocytes/macrophages infected with the intracellular bacterium L. pneumophila (23), as PM permeability increased at the same time of annexin V binding, a finding consistent with necrosis rather than apoptosis. PS access may have occurred via membrane injury due to the high L. pneumophila infectious titers employed (>20 IFU of L. pneumophila/cell versus 2 IFU of Chlamydia/cell) and may not represent a specific response to infection. Influenza-infected epithelial cells externalize PS 9 to 12 h postinfection; however, significant PM permeability was also observed (22). CD47 ligation on activated T cells results in rapid (∼30 min) PS externalization (45); again, an increase in PM permeability was seen. Clearly, Chlamydia-mediated PS externalization differs from that induced by other agents; this may reflect activation of a different host signaling pathway(s).

Our results imply that chlamydial binding is required to induce host cell PS exposure. Chlamydia-mediated PS externalization is contact dependent (heparin inhibitable), is localized to the outer PM leaflet, and is induced in four human cell types as well as the mouse connective tissue-derived line L929 (data not shown).

The rapid onset and disappearance of PS after inoculum withdrawal (Fig. 4B and C) may reflect endocytosis-related changes in the lipid composition of the PM, as Chlamydia cells are ingested within 5 min after cell contact (43). Increased cyclic GMP and calcium influx increase the efficiency of chlamydial entry (40), and tyrosine phosphorylation of host proteins occurs 15 min after infection (6, 20). Rapid PS externalization upon contact suggests that Chlamydia cells initiate host cell signaling during invasion.

PS exposure is an early marker of apoptosis (38) and is associated with the proinflammatory triggering of the alternative pathway of complement activation (39, 65). We did not address whether these two processes occurred in Chlamydia-infected cells. Induction of pro- or antiapoptotic phenotypes in host cells by Chlamydia remains unclear. Chlamydia-induced apoptosis has been reported (25, 42); however, another study reported induction of an antiapoptotic phenotype (19). PS exposure is associated with apoptosis, but we did not find a link between caspase activation and Chlamydia-mediated PS exposure. As Chlamydia-triggered PS exposure occurs rapidly after inoculum addition, it may be that caspase activation is not required or is bypassed. Our findings agree with those of Ojcius et al. (42), in which the appearance of apoptosis markers in Chlamydia-infected cells were not attenuated by caspase inhibitors. Although we cannot rule out the involvement of caspase(s) in PS exposure elicited by Chlamydia, it appears that their contribution to this process is minor.

Neutrophils kill C. trachomatis cells (49, 67) and have a role in preventing their dissemination (4). Macrophages fed PS-expressing apoptotic neutrophils or opsonized zymosan release soluble Fas ligand, which is capable of killing neutrophils, monocytes, eosinophils, and lymphocytes (9). We demonstrated that Chlamydia-infected neutrophils are phagocytosed by macrophages in a PS-dependent manner. Our results agree with those of Fadok et al. (18), in which uptake of PS-positive apoptotic neutrophils by glucan-stimulated HMDMs was strongly inhibited by PS liposomes, but not RGDS peptide. That RGDS reduced uptake in our experiments may reflect the fact that fewer of our macrophages switched exclusively to PS-specific receptors. The rapid (<2 h) PS-mediated HMDM phagocytosis of neutrophils we have seen may represent an exploitation of host homeostatic mechanisms by Chlamydia, in which the bacterium rids itself of a noxious opponent(s), but whether phagocytosis of infected neutrophils benefits or harms the host during a natural infection is unknown.

Segregation of macrophages and dendritic cells into “classically” and “alternatively” activated phenotypes (26) is hypothesized to explain how these antigen-presenting cells (APCs) generate proinflammatory (“classical”) or anti-inflammatory (“alternative”) responses and modify immune outcomes. APCs acquire alternative activation phenotypes when they ingest PS-exposing apoptotic cells (17, 51, 64). Alternatively activated APCs secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines, enhance endocytic and antigen presentation capacities, up-regulate receptors for innate immunity, and reduce production of nitric oxide and reactive oxygens (26). Delayed proinflammatory cytokine release may affect chlamydial pathogenesis, as resident macrophages may ingest PS-expressing cells acutely infected with Chlamydia. As interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-8, and TNF-α are secreted by epithelial cells 24 h postinfection (48) and Chlamydia cells are rapidly internalized (≤5 min after contact; 43), there is little chance of proinflammatory macrophage activation by exogenous cytokines or free bacteria. After ingesting PS-expressing cells, which may be enhanced by PS-mediated C3bi deposition on target cells (39), macrophages express antiinflammatory cytokines (17, 64), release soluble Fas ligand (9), and are poor stimulators of T and B cells (64), all hallmarks of alternative activation status.

Procoagulant states are induced in monocytes and endothelial cells after stimulation with lipopolysaccharide, TNF-α, or IL-1 (14, 50, 53, 70) and, in this report, with Chlamydia-infected THP-1 promonocytes. Thrombin formation, a central event in coagulation and inflammation, catalyzes fibrin generation and binds thrombin receptors, activating transcription in vascular cells, including monocytes (12) and endothelial cells (1, 60). Fibrin deposition, associated with wound repair, inflammation, and coagulation (13), attracts platelets, neutrophils, and leukocytes (34) and may initiate vascular plaques (5, 52). Thus, cellular PS exposure following chlamydial infection may modulate the inflammatory, tissue remodeling, and immune responses of the host.

Chlamydia-infected mesothelial and endothelial cells upregulated TF, PAI-1 (22, 63), and platelet adhesion (22) activities several hours postinfection. Our data, with which we show that infected epithelial and aortic endothelial cells immediately externalize PS, may provide a molecular understanding of the results reported by Fryer et al. (21) and van Westreenen et al. (63), in which C. trachomatis-infected cells acquired factor Xa-generating activity. We showed that bacterial metabolism was not a prerequisite, as chloramphenicol-treated Chlamydia cells induced PS exposure. Induction of TF, PAI-1, and PS suggests that Chlamydia-inoculated endothelium can initiate and sustain coagulation reactions. Platelets (32), monocytes (33), neutrophils (34), and T cells (46), elements commonly found in atherosclerotic plaques, adhere to thrombin-treated endothelial cells. PS exposure, leading to macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of and procoagulant activity by infected cells, may be important in the genesis of chlamydial dissemination and systemic diseases, including atherosclerosis caused by Chlamydia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Joel D. Ernst for the generous gift of recombinant annexin V-GFP and his insightful discussions.

These studies were supported by NIH grants AI40250 and AI2943.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anrather D, Millan M T, Palmetshofer A, Robson S C, Geczy C, Ritchie A J, Bach F H, Ewenstein B M. Thrombin activates nuclear factor kB and potentiates endothelial cell activation by TNF. J Immunol. 1997;159:5620–5628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aupeix K, Toti F, Satta N, Bischoff P, Freyssinet J M. Oxysterols induce membrane procoagulant activity in monocytic THP-1 cells. Biochem J. 1996;314:1027–1033. doi: 10.1042/bj3141027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aupeix K, Hugel B, Martin T, Bischoff P, Lill H, Pasquali J-L, Freyssinet J-M. The significance of shed membrane particles during programmed cell death in vitro, and in vivo, in HIV-1 infection. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:1546–1554. doi: 10.1172/JCI119317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barteneva N, Theodor I, Peterson E M, de la Maza L M. Role of neutrophils in controlling early stages of a Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4830–4833. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4830-4833.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bini A, Kudryk B J. Fibrinogen in human atherosclerosis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1995;748:461–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb17342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birkelund S, Johnsen H, Christiansen G. Chlamydia trachomatis serovar L2 induces protein tyrosine phosphorylation during uptake by HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4900–4908. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4900-4908.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bombeli T, Karsan A, Tait J F, Harlan J M. Apoptotic vascular endothelial cells become procoagulant. Blood. 1997;89:2429–2442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bratton D L, Fadok V A, Richter D A, Kailey J M, Guthrie L A, Henson P M. Appearance of phosphatidylserine on apoptotic cells requires calcium-mediated nonspecific flip-flop and is enhanced by the loss of the aminophospholipid translocase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26159–26165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown S B, Savill J. Phagocytosis triggers macrophage release of Fas ligand and induces apoptosis of bystander leukocytes. J Immunol. 1999;162:480–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casciola-Rosen L, Rosen A, Petri M, Schlissel M. Surface blebs on apoptotic cells are sites of enhanced procoagulant activity: implications for coagulation events and antigenic spread in systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1624–1629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control. Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections—United States, 1995. JAMA. 1997;277:952–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colotta F, Sciacca F L, Sironi M, Luini W, Rabiet M J, Mantovani A. Expression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 by monocytes and endothelial cells exposed to thrombin. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:975–985. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cotran R, Kumar V, Robbins S L. Inflammation and repair. In: Cotran R, Kumar V, Robbins S L, editors. Robbins pathologic basis of disease. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: W. B. Saunders; 1989. p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dachary-Prigent J, Toti F, Satta N, Pasquet J M, Uzan A, Freyssinet J M. Physiopathological significance of catalytic phospholipids in the generation of thrombin. Semin Thromb Hemostasis. 1996;22:157–164. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-999004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz C, Schroit A J. Role of translocases in the generation of phosphatidylserine asymmetry. J Membr Biol. 1996;151:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s002329900051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ernst J D, Yang L, Rosales J L, Broaddus V C. Preparation and characterization of an endogenously fluorescent annexin for detection of apoptotic cells. Anal Biochem. 1998;260:18–23. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fadok V A, Bratton D L, Konowal A, Freed P W, Wescott J Y, Henson P M. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGFβ, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:890–898. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fadok V A, Warner M L, Bratton D L, Henson P M. CD36 is required for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by human macrophages that use either a phosphatidylserine receptor or the vitronectin receptor (alpha V beta3) J Immunol. 1998;161:6250–6257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan T, Lu H, Hu H, Shi L, McClarty G A, Nance D M, Greenberg A H, Zhong G. Inhibition of apoptosis in Chlamydia-infected cells: blockade of mitochondrial cytochrome c release and caspase activation. J Exp Med. 1998;187:487–496. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fawaz F S, van Ooij C, Homola E, Mutka E, S C, Engel J N. Infection with Chlamydia trachomatis alters the tyrosine phosphorylation and/or localization of several host cell proteins including cortactin. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5301–5308. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5301-5308.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fryer R H, Schowbe E P, Woods M L, Rodgers G M. Chlamydia species infect human vascular endothelial cells and induce procoagulant activity. J Investig Med. 1997;45:168–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujimoto I, Takizawa T, Ohba Y, Nakanishi Y. Co-expression of Fas and Fas-ligand on the surface of influenza virus-infected cells. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:426–431. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao L-Y, Kwaik Y A. Apoptosis in macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells during early stages of infection by Legionella pneumophilia and its role in cytopathogenicity. Infect Immun. 1999;67:862–870. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.862-870.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaydos C A, Summersgill J T, Sahney N N, Ramirez J A, Quinn T C. Replication of Chlamydia pneumoniae in vitro in human macrophages, endothelial cells, and aortic smooth muscle cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1614–1620. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1614-1620.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibellini D, Panaya R, Rumpianesi F. Induction of apoptosis by Chlamydia psittaci and Chlamydia trachomatis infection in tissue culture cells. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1998;288:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(98)80095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goerdt S, Orfanos C E. Other functions, other genes: alternative activation of antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 1999;10:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grayston J T, Wang S. New knowledge of chlamydiae and the diseases they cause. J Infect Dis. 1975;132:87–105. doi: 10.1093/infdis/132.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grayston J T. Chlamydiae pneumoniae, strain TWAR pneumoniae. Annu Rev Med. 1992;43:317–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.43.020192.001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haslett C. Granulocyte apoptosis and inflammatory disease. Br Med Bull. 1997;53:669–683. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holmes K, Fowlkes B J, Schmid I, Giorgi J V. Staining of nonviable cells with 7-aminoactinomycin for dead-cell discrimination. In: Coligan J E, Kruisbeek A M, Margulies D H, Shevach E M, Strober W, editors. Current protocols in immunology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1991. pp. 5.3.1–5.3.23. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holvoet P, Collen D. Thrombosis and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1997;8:320–328. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199710000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Itoh Y, Tomita M, Tanahashi N, Takeda H, Yokoyama M, Fukuuchi Y. Platelet adhesion to aortic endothelial cells in vitro after thrombin treatment: observation with video-enhanced contrast microscopy. Thromb Res. 1998;91:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(98)00054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplanski G, Marin V, Fabrigoule M, Boulay V, Benoliel A M, Bongrand P, Kaplanski S, Farnarier C. Thrombin-activated human endothelial cells support monocyte adhesion in vitro following expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1; CD54) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1; CD106) Blood. 1998;92:1259–1267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirchhofer D, Sakariassen K S, Clozel M, Tschopp T B, Hadvary P, Nemerson Y, Baumgartner H R. Relationship between tissue factor expression and deposition of fibrin, platelets, and leukocytes on cultured endothelial cells under venous flow condions. Blood. 1993;81:2050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuo C-C. Host response. In: Barron A L, editor. Microbiology of chlamydiae. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press Inc.; 1988. pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maass M, Bartels C, Engel P M, Mamat U, Sievers H H. Endovascular presence of viable Chlamydia pneumoniae is a common phenomenon in coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:827–832. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Majeed M, Gustafsson M, Kihlstrom E, Stendhal O. Roles of Ca2+ and F-actin in intracellular aggregation of Chlamydia trachomatis in eucaryotic cells. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1406–1414. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1406-1414.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin S J, Reutelingsperger C P, McGahon A J, Rader J A, van Schie R C, LaFace D M, Green D R. Early redistribution of plasma membrane phosphatidylserine is a general feature of apoptosis regardless of the initiating stimulus: inhibition by overexpression of BCL-2 and Abl. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1545–1556. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mevorach D, Mascarenhas J O, Gershov D, Elkon K B. Complement-dependent clearance of apoptotic cells by human macrophages. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2313–2320. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moulder J W. Interaction of Chlamydia and host cells in vitro. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:143–190. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.1.143-190.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oeth P, Yao J, Fan S T, Mackman N. Retinoic acid inhibits lipopolysaccharide induction of tissue factor gene expression in human monocytes. Blood. 1998;91:2857–2865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ojcius D M, Souque P, Perfettini J L, Dautry-Varsat A. Apoptosis of epithelial cells and macrophages due to infection with the obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia psittaci. J Immunol. 1998;161:4220–4226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patton D L, Cummings P K, Sweeny C, Kuo Y T, Kuo C-C. In vivo uptake of Chlamydia trachomatis by Fallopian tube epithelial cells is rapid. In: Stephens R S, Byrne G I, Christiansen G, Clarke I N, Grayston J T, Rank R G, Ridgeway G L, Saikku P, Schachter J, Stamm W E, editors. Chlamydial infections. Proceedings of the Ninth International Symposium on Human Chlamydial Infection. San Francisco, Calif: International Chlamydia Symposium; 1998. pp. 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pelassy C, Mary D, Aussel C. Effects of the serine analogues isoserine and serinol on interleukin-2 synthesis and phospholipid metabolism in a human T cell line Jurkat. J Lipid Mediat. 1991;3:79–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pettersen R D, Hestdal K, Olafsen M K, Lie S O, Lindberg F P. CD47 signals T cell death. J Immunol. 1999;162:7031–7040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qu J, Conroy L A, Walker J H, Wooding F B, Lucy J A. Phosphatidylserine-mediated adhesion of T-cells to endothelial cells. Biochem J. 1996;317:343–346. doi: 10.1042/bj3170343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramirez J A Chlamydia pneumoniae/Atherosclerosis Study Group. Isolation of Chlamydia pneumoniae from the coronary artery of a patient with coronary atherosclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 1997;125:979–982. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-12-199612150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rasmussen S J, Eckmann L, Quayle A J, Shen L, Zhang Y X, Anderson D J, Fierer J, Stephens R S, Kagnoff M F. Secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by epithelial cells in response to Chlamydia infection suggests a central role for epithelial cells in chlamydial pathogenesis. J Clin Investig. 1997;1:77–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI119136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Register K B, Morgan P A, Wyrick P B. Interaction between Chlamydia spp. and human polymorphonuclear leukocytes in vitro. Infect Immun. 1986;52:664–670. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.3.664-670.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robinson R A, Worfolk L, Tracy P B. Endotoxin enhances the expression of monocyte prothrombinase activity. Blood. 1992;79:406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ronchetti A, Rovere P, Iezzi G, Galati G, Heltai S, Protti M P, Manfredi A A, Rugarli C, Bellone M. Immunogenicity of apoptotic cells in vivo: role of antigen load, antigen-presenting cells, and cytokine. J Immunol. 1999;163:130–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ross R. Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruf W, Edgington T S. Structural biology of tissue factor, the initiator of thrombogenesis in vivo. FASEB J. 1994;8:385–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saikku P, Leinonen M, Mattila K, Ekman M R, Nieminen M S, Makela P H, Huttunen J K, Valtonen V. Serological evidence of an association of a novel Chlamydia, TWAR, with chronic heart disease and acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1988;ii:983–986. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90741-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Savill J S, Wyllie A H, Henson J E, Walport M J, Henson P M, Haslett C. Macrophage phagocytosis of aging neutrophils in inflammation. J Clin Investig. 1989;83:865–875. doi: 10.1172/JCI113970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Savill J S. Recognition and phagocytosis of cells undergoing apoptosis. Br Med Bull. 1997;53:491–508. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schachter J. Chlamydial infections. West J Med. 1990;153:523–534. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schmid I, Krall W J, Uittenbogaart C H, Braun J, Giorgi J V. Dead cell discrimination with 7-aminoactinomycin D in combination with dual color immunofluorescence in single laser flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1992;13:204–208. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990130216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sneddon J M, Wenman W M. The effect of ions on the adhesion and internalization of Chlamydia trachomatis by HeLa cells. Can J Microbiol. 1985;31:371–374. doi: 10.1139/m85-071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sugama Y, Tiruppathi C, Offakidevi K, Andersen T T, Fenton II J W, Malik A B. Thrombin-induced expression of endothelial P-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1: a mechanism for stabilizing neutrophil adhesion. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:935–944. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vanags D M, Porn-Ares M I, Coppola S, Burgess D H, Orrenius S. Protease involvement in fodrin cleavage and phosphatidylserine exposure in apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31075–31085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Engeland M, Nieland L J, Ramaekers F C, Schutte B, Reutelingsperger C P. Annexin V-affinity assay: a review of an apoptosis detection system based on phosphatidylserine exposure. Cytometry. 1998;31:1–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19980101)31:1<1::aid-cyto1>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Westreenen M, Pronk A, Diepersloot R J, de Groot P G, Leguit P. Chlamydia trachomatis infection of human mesothelial cells alters proinflammatory, procoagulant, and fibrinolytic responses. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2352–2355. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2352-2355.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Voll R E, Herrman M, Roth E, Stach C, Kalder J R, Girkontaite I. Immunosuppressive effects of apoptotic cells. Nature. 1997;390:350. doi: 10.1038/37022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang R H, Phillips G, Jr, Medof M E, Mold C. Activation of the alternative complement pathway by exposure of phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylserine on erythrocytes from sickle cell disease patients. J Clin Investig. 1993;92:1326–1335. doi: 10.1172/JCI116706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wyllie A H. Apoptosis: an overview. Br Med Bull. 1997;53:451–465. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yong E C, Klebanoff S J, Kuo C-C. Toxic effect of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes on Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1982;37:422–426. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.2.422-426.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang J P, Stephens R S. Mechanism of C. trachomatis attachment to eukaryotic host cells. Cell. 1992;69:861–869. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90296-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhuang J, Ren Y, Snowden R T, Zhu H, Gogvadze V, Savill J S, Cohen G M. Dissociation of phagocyte recognition of cells undergoing apoptosis from other features of the apoptotic program. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15628–15632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zwaal R F A, Schroit A J. Pathophysiological implications of membrane phospholipid asymmetry in blood cells. Blood. 1997;88:1121–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]