Abstract

Background

Computed tomography (CT)-scan measures of muscle composition may be associated with recovery post hip fracture.

Methods

In an ancillary study to Baltimore Hip Studies Seventh cohort, older adults were evaluated at 2 and 6 months post hip fracture. CT-scan measures of muscle were acquired at 2 months. Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) was measured at 2 and 6 months. Generalized estimating equations were used to model the association of muscle measures and physical function, adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, and time postfracture.

Results

Seventy-one older adults (52% males, age 79.6 ± 7.3 years) were included. At 2-months, males had greater thigh cross-sectional area (CSA, p < .0001) and less low-density muscle (p = .047), and intermuscular adipose tissue (p = .007) than females on the side of the fracture, while females performed better on the SPPB (p = .05). Muscle measures on the fractured side were associated with function at 2 months in both sexes. Participants with the lowest tertile of muscle CSA difference at 2-months, indicating greater symmetry in CSA between limbs, performed better than the other 2 tertiles at 6-months. Males performed worse in functional measures at baseline and did not recover as well as females (p = .02).

Conclusion

CT-scan measures of muscle CSA and fatty infiltration were associated with function at 2-months post hip fracture and with improvement in function by 6 months. Observed sex differences in these associations suggest that rehabilitation strategies may need to be adapted by sex after hip fracture.

Keywords: Computed tomography (CT scan), Physical function, Sex differences

Hip fractures are a significant economic burden to society. In addition to the direct costs related to the treatment of the acute fracture, patients who have suffered a hip fracture may have persistent limitations in mobility and activities of daily living that necessitate increased care (1–3). Recovery of function varies depending on the demands of the task, for example, fewer than 50% of persons are able to get out of a chair or walk independently 1-year postfracture (3,4). Functional recovery may be influenced by age, psychosocial factors, number of comorbidities, and complications postfracture (5). It may also be influenced by muscle strength and other muscle characteristics. We reported that greater dorsiflexion and grip strength and not muscle mass were associated with better recovery of mobility in women post hip fracture but this study did not include a measure of muscle fatty infiltration (6). Radiological measures that show higher levels of fatty infiltration in muscle tissues in healthy older adults are associated with worse function (7). Similar observations have been made in persons with rheumatoid arthritis, where greater thigh muscle fatty infiltration is associated with poorer performance in all functional measures (8). It is therefore possible that the quality of muscle may also play a role in the recovery of mobility post hip fracture (7). Despite the evidence that muscle fatty infiltration plays a role in reduced mobility in other populations, there is limited evidence on muscle composition quality and its relationship to function and recovery of function in persons post hip fracture.

Although previous work has investigated the association of lean muscle mass, as measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), with functional recovery (6,9,10), DXA measurements of lean mass as an estimate of muscle composition are limited. DXA does not allow for the measurement of fatty infiltration in muscle, which is believed to reflect the quality of muscle tissue. Previous work in older adults reported that lower levels of fatty infiltration (ie, better muscle quality) on computed tomography (CT) imaging are associated with better function, independent of muscle mass and muscle strength (7,11). We have previously reported a loss in muscle cross-sectional area (CSA) and a concomitant increase in fat around and within the muscle in the thigh on the side of the fracture when compared to the uninvolved side at 2 months post hip fracture (12). We now report on the association between muscle composition and its relationship to function and functional recovery during the year after fracture.

Historically the prevalence of hip fractures is lower in males (13), and consequently, less is known about their functional recovery. In 2019 the incidence of hip fractures was reported to be 166.2 per 100 000 in males and 189.8 per 100 000 in females (14). Moreover, hip fracture rates among men are projected to increase by 51% from 2010 to 2030, while the number of hip fractures among women is expected to decrease by 3.5% (13). Previous work (7,9) found that measures of muscle mass and area were differently related to function and functional recovery in males and females. In a study of older adults (7), smaller muscle area was related to poorer function in males, whereas in females, muscle area was not associated with lower extremity function until adjusted for total body fat. Furthermore, Di Monaco et al. (9) found that muscle mass was associated with functional recovery in males but not in females post hip fracture. These authors went on to suggest that future work should investigate the role of sex and muscle composition in functional recovery postfracture because the use of DXA-determined muscle measures in their study could not explain these relationships. Whether differences in functional recovery between the sexes are due to differences in muscle composition, including measures of fatty infiltration is not known. As the proportion of males who fracture their hips is expected to increase (1,13), more studies that investigate functional recovery and its association to muscle composition including both males and females are warranted., the purpose of this study was twofold, to examine thigh muscle composition measures and their relationship to function at baseline (2 months posthospital admission) and recovery of function (at 6 months) in older adults post hip fracture and to determine if these relationships differed by sex.

Method

Sample

The sample for this study derived from a prospective cohort (Baltimore Hip Studies Seventh cohort [BHS-7]), that was designed to include equal numbers of male and female participants to assess sex differences across various outcomes post hip fracture (15). Participants were recruited from 8 hospitals in the Baltimore metropolitan area within 15 days of admission and were assessed at baseline (within 22 days of admission), 2, 6, and 12 months postadmission.

An ancillary study to BHS-7 conducted CT scans of the thigh muscles at 2 months postadmission. Two hundred sixty-nine (269) older adults post hip fracture (135 males; 134 females) enrolled in the parent study and who participated in the 2-month follow-up visit were invited to participate in the CT Ancillary Study with 40 participants ineligible (20 male/20 female) due to: impairment that would interfere with the participant being left alone during the CT scan (n = 12), inability to lie supine (n = 7), and other reasons (n = 21). Of the 229 (85%) eligible participants, 143 (including 13 proxies) refused to participate, and 6 participants were unable to be contacted for consent. A total of 42 males and 38 females consented to participate in the ancillary study; 2 participants failed to get the first CT-scan measurement at 2 months postadmission, and an additional 5 participants were subsequently withdrawn from this ancillary study due to an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-requested postprocedure audit of the parent study (3 participants were found to be ineligible and 2 had informed consent irregularities). Thus, the final possible analytic sample was 73 (38 males, 35 females). Of these, 1 male and 1 female were missing CT data at 2 months, such that the final sample included 37 males and 34 females who had both thigh muscle composition and functional performance data at 2 months and 66 (35 males, 31 females) who had 2- and 6-month functional performance measure data. CT data from 6 and 12 months are not included due to limited sample size. Both the BHS-7 and the CT Ancillary Study were approved by the IRB at the University of Maryland Baltimore, as well as by each of the study hospitals’ respective IRBs.

Patient Characteristics at Baseline

In addition to sex, several other patient characteristics were assessed at baseline for the parent study, including age, marital status, education, fracture site, and surgical procedure. Comorbidity was assessed with the Charlson Comorbidity Index (16), and cognitive status was assessed with the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS) (17). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from knee height and weight, and physical activity was measured with the Yale Physical Activity Scale (18).

Muscle Composition Measures

CT of the midthigh muscles

Axial CT scans (Philips Brilliance 64 CT scanner, Phillips Electronics N.V. Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at the midthigh were obtained with the patient in the supine position, arms above the head, toes directed toward the top of the gantry, and legs extended flat on the table. An anterior–posterior scout scan of the entire femur was used to localize the midthigh position. The femoral length was measured in cranial-caudal dimension, and the scan position was determined as the midpoint of the distance between the medial edge of the greater trochanter and the intercondyloid fossa. A single, 10-mm-thick axial image was acquired at the femoral midpoint on both sides. The scanning parameters were 120 kVp and 200–250 mA. Images were transferred (TCP/IP protocols) to a SUN workstation (SPARCstation II, Sun Microsystems, Mountain View, CA) for review. This article only includes the CT measures taken at the 2-month time point, which was the baseline CT measure. All images were analyzed by one person using SliceOmatic software version 3 (Tomovision, Montréal, Canada). This method has been found to be both reliable and valid (19,20).

(1) Muscle CSA included all muscles in the thigh and was calculated by multiplying the number of pixels of nonbone, nonadipose tissue within the fascial plane by the pixel area.

(2) Subcutaneous adipose tissue was distinguished from the intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT) by manually drawing a line along the deep fascial plane surrounding the thigh muscles. Muscle and adipose tissue areas were identified based on a bimodal image histogram resulting from the distribution of CT numbers in muscle and adipose tissue. The peaks were readily separable, and the area of fat in the image was determined by the area under the fat peak of the histogram. Muscles were well-outlined by adipose tissue. In instances where separations were not clear, fat-muscle borders were outlined manually with internal controls in place to assure that no bone density pixels were included with muscle area. Greater IMAT CSA means there is more fat around the muscle tissue.

(3) Muscle attenuation was calculated by averaging CT number (pixel intensity) values of the regions outlined on the images. CT numbers are defined on a Hounsfield Unit (HU) scale where 0 equals HU of water and −1 000 equals HU of air. Higher levels of HU are associated with lower levels of fat infiltration in the muscle tissue. Normal-density muscle (NDM) and low-density muscle (LDM) are defined by their HU of measurement, namely 0–29 HU represents LDM, and 30–100 HU represents NDM. Further details of the CT analysis are included in Goodpaster et al. (19). All images were analyzed in accordance with these methods by a member of the Goodpaster lab.

(4) Fractured side % IMAT, NDM and LDM were calculated using the following formulas ([IMAT/CSA]×100), ([NDM/CSA]×100), and ([LDM/CSA]×100).

(5) CSA difference (CSA Diff) was calculated as the differences in CSA between the fractured and nonfractured limbs.

Functional Measures

Functional measures including Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) was conducted at both the 2 and 6 month time points. The SPPB assessed timed physical activities of balance, gait, and strength (21). This study includes gait speed, chair rise time (a proxy of lower extremity strength), and the overall SPPB score. Balance, although collected, was not included on its own in the analyses because our primary interest were tasks of mobility (gait speed) and strength (chair rise time). Higher scores in gait speed and SPPB score are better while lower scores in the chair rise time indicate faster performance. If a participant could not do one chair rise in 60 seconds as per the SPPB protocol, the test was scored as 61 seconds (21).

Analyses

Independent sample t test and χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, were used to assess for between sex differences in the demographic data, functional measures, and muscle composition measures. Pearson correlations were used to assess relationships among muscle composition measures and function. Thigh muscle composition measures of CSA, muscle attenuation, and IMAT were divided into tertile groups. A one-way ANOVA was used to test for differences in muscle composition tertile and performance in functional measures. Where the one-way ANOVA that was used to test for differences in muscle composition tertile and performance in functional measures was significant, post hoc testing was used to determine where the differences lay between pairs of tertiles. Generalized estimating equations (GEEs) were used to model the longitudinal association of muscle composition and physical function, modeling muscle composition continuously. Additional variables included in the models were time (2 and 6 months postadmission), sex, age, and BMI. Age and BMI were added as possible confounders of muscle quality and functional performance (7,8,22). GEEs account for intrapatient correlation, tolerate missing data points, and are applicable to a variety of dependent variables (ie, continuous measures, binary outcomes, and counts) (23). The uninvolved side was included in the model as a covariate except where the model includes the CSA difference variable. Because it is difficult to visualize a continuous by continuous relationship over time graphically, the relationship between continuous muscle composition values (CSA, IMAT CSA, muscle attenuation, and CSA difference) and physical function outcomes from model estimates were plotted for tertile median values. Model 1 included time, Model 2 included sex and time, and Model 3 included sex, time, age, and BMI. The estimates come from models with continuous muscle composition variables but were plotted by tertile for simplicity.

Results

Participants were mostly White, and a greater percentage of males were married than females (p < .001). Both the site of the fracture and surgical intervention were similar between males and females in this sample, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Sex

| Males (N = 37, 52.1%) | Females (N = 34, 47.9%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | n | % | n | % | p Value |

| Race | .20† | ||||

| Black | 4 | 10.8 | 1 | 2.9 | |

| White | 32 | 86.5 | 33 | 97.1 | |

| Other | 1 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Marital status | <.0002** | ||||

| Married | 26 | 70.3 | 8 | 23.5 | |

| Not married | 11 | 29.7 | 26 | 76.5 | |

| Fracture site | .99 | ||||

| Intertrochanteric | 19 | 51.4 | 16 | 47.1 | |

| Other‡ | 18 | 48.6 | 18 | 52.9 | |

| Surgery type | .99† | ||||

| Internal fixation | 21 | 56.8 | 17 | 50.0 | |

| Arthroplasty | 15 | 40.5 | 17 | 50.0 | |

| Other | 1 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age (years) | 79.0 | 7.6 | 80.3 | 7.0 | .47 |

| Education (years) | 13.5 | 3.6 | 12.7 | 3.3 | .31 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.0 | .42 |

| 3MS score | 89.9 | 9.9 | 89.1 | 14.8 | .79 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.5 | 3.5 | 27.4 | 5.2 | .09 |

| Prefracture Yale Activity Measure (kilocalories/week) | 3 141.0 | 2 554.0 | 4 035.0 | 2 819.0 | .18 |

| Two month Yale Activity Measure (kilocalories/week) | 1 722.0 | 2 249.0 | 2 350.0 | 2 519.0 | .30 |

| Thigh muscle CSA (cm2) | 85.31 | 18.9 | 61.77 | 12.7 | <.0001** |

| IMAT CSA (cm2) | 16.16 | 6.6 | 17.30 | 9.7 | .57 |

| Thigh muscle attenuation (HU) | 37.09 | 4.3 | 34.16 | 4.3 | .005** |

| % IMAT | 19.4 | 8.0 | 30.4 | 22.0 | .007** |

| % NDM | 56.0 | 10.6 | 48.1 | 12.1 | .005** |

| % LDM | 45.6 | 11.0 | 51.7 | 14.2 | .05* |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 0.42 | 0.3 | 0.39 | 0.2 | .65 |

| Chair Rise time (s) | 55.1 | 19.0 | 49.5 | 17.0 | .01** |

| SPPB score | 3.41 | 2.9 | 4.55 | 2.5 | .05* |

Notes: Baseline CT measures were obtained at the 2 month testing session. Data presented is from the fractured side only. BMI = body mass index; CSA = cross-sectional area; HU = Hounsfield units; IMAT = intermuscular adipose tissue; LDM = low-density muscle; NDM = normal-density muscle (high density or lean muscle); SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery; 3MS = Modified Mini-Mental State Examination.

†Fisher’s Exact Test used here.

‡Includes femoral neck, subcapital, and unclassified hip fractures.

*p ≤ .05;

**p ≤ .01.

Males and females were similar in age, level of education, and Charlson Comorbidity Index. On the 3MS assessment, a score above 78 (on the 100-point scale) is considered normal (17), and males and females scored similarly and well above 78. Males had greater thigh CSA (p < .001), higher muscle attenuation (p = .005), and smaller percentages of LDM (p = .047), and IMAT (p = .007) on the fractured side than females at 2 months postadmission, see Table 1.

Correlations

Combining data on males and females at 2 months, there was a negative correlation between muscle attenuation and IMAT CSA on the fractured side (r = −0.44, p < .01). There were weak but significant correlations between faster gait speed and greater muscle CSA (r = 0.29, p = .03), lesser %IMAT (r = −0.28, p = .04), lesser %LDM (r = −0.36, p = .01), and greater %NDM (r = 0.29, p = .03). There were also moderate but nonsignificant trends between faster chair rise time (r = −0.20, p = .13), higher SPPB score (r = 0.23, p = .08), and greater muscle CSA. Finally, there was a trend between greater muscle attenuation and faster gait speed (r = 0.23, p = .08).

Association Between Muscle Composition and Functional Measures at 2 Months Based on Longitudinal Regression Models

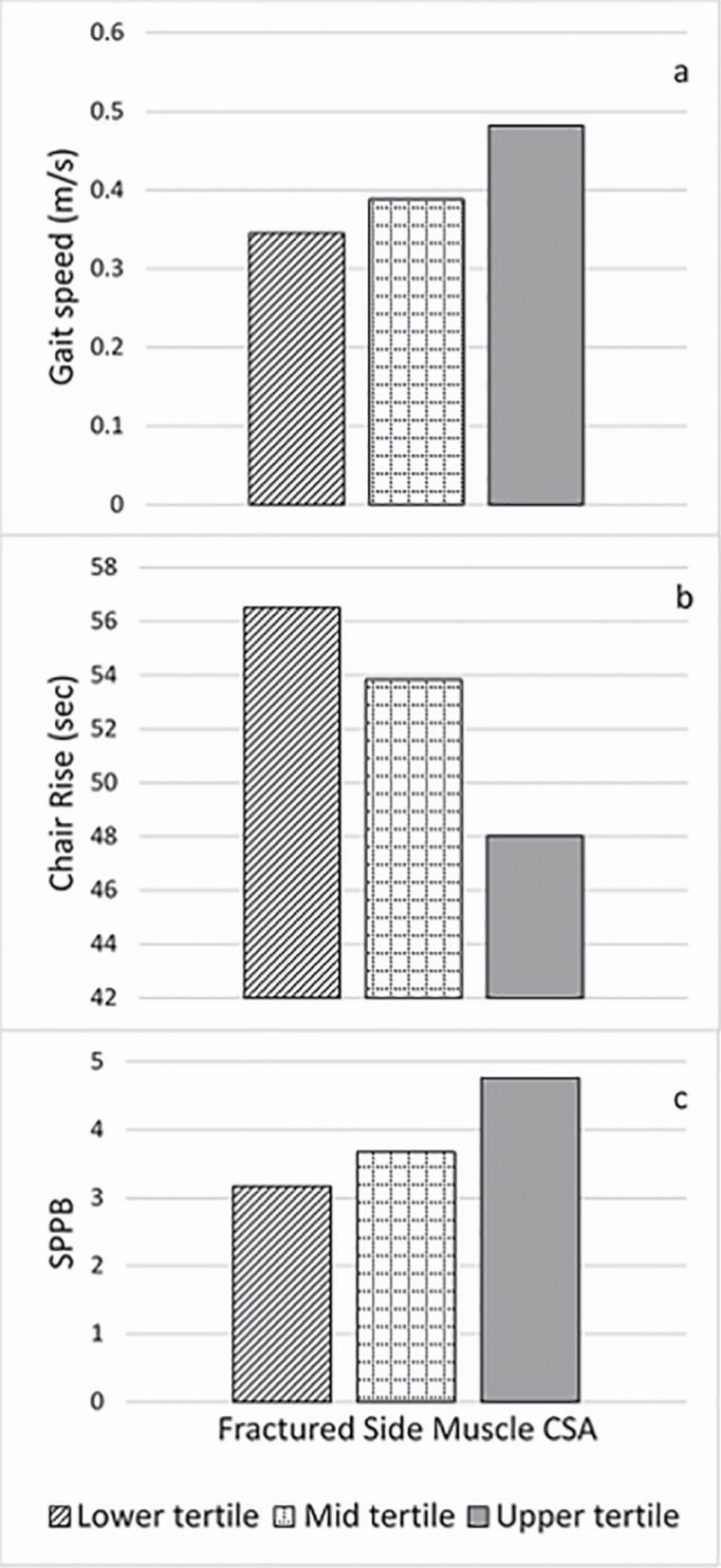

Results of the thigh muscle composition measures of CSA, muscle attenuation, and IMAT CSA and their association to the functional measures were depicted in figures by tertile groups (ie, lower, mid, and upper). There was a significant association between fractured side CSA and 2-month gait speed (p < .01), chair rise time (p < .001), and SPPB score (p < .01) after adjusting for sex and muscle CSA difference (Figure 1A, B, and C); such that having greater fractured side muscle CSA conferred better performance, see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. When BMI was added in Model 3, muscle CSA remained independently associated with all functional measures. Furthermore, having a lower BMI conferred better gait speed (p ≤ .01), chair rise time (p ≤ .05), and SPPB (p ≤ .01). The addition of age in the model did not explain the effect of fractured side CSA on function, see Supplementary Table 3.

Figure 1.

GEE Model 2 of fractured side muscle cross-sectional area (CSA) at 2 months depicted in tertiles for the 3 functional measures (A) gait speed, p ≤ .005; (B) chair rise time, p ≤ .001; and (C) SPPB score, p = .008. p values are for GEE model run with continuous muscle CSA and functional measures data. GEE = generalized estimating equations; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery.

We also observed an association between fractured side muscle attenuation and gait speed (Models 1 and 2, p < .05 for both). Post hoc testing revealed significant differences between each tertile of fractured side attenuation such that the greater the muscle attenuation (eg, the less fatty infiltration in the muscle), the faster the gait speed (Figure 2A). Chair rise time was not associated with muscle attenuation (Model 2, p = .36). There was some evidence of an association between fractured side muscle attenuation and SPPB score (Model 2, Figure 2B, p = .070) such that those with less fatty infiltration in the muscle, had a higher SPPB score. However, when age was added to the model, the effect of muscle attenuation on gait speed and SPPB became nonsignificant. Age and muscle attenuation were collinear with older age being associated with less muscle attenuation and slower gait speed. The addition of BMI in the model did not explain the effect of muscle attenuation on function. Fractured side IMAT CSA was not associated with differences in gait speed, chair rise time, or SPPB score, see Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Figure 2.

GEE Model 2 between fractured side muscle attenuation (MA) at 2 months depicted in tertiles for the functional measures (A) gait speed, p ≤ .05. Post hoc testing; *p = .03 between tertile 1 (lower) and 2 (mid), **p = .03 between tertile 1 and 3 (upper), and +p = .03 between tertile 2 and 3 and (B) SPPB Score. GEE = generalized estimating equations; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery.

Longitudinal Analyses: Muscle Composition at 2 Months and Recovery in Function From 2 to 6 Months

Based on Model 1, there was an association of gait speed by muscle CSA difference (Figure 3A, p ≤ .05), in that those with the least side-to-side CSA difference between the limbs (ie, meaning both limbs had similar CSA), performed better in gait speed at 2 months and maintained this at 6 months. Whereas in those with the greatest muscle CSA limb difference (ie, those in the highest tertile of CSA limb difference), the model-based estimates of average gait speed at 2 months were similar to the other tertiles but declined by 6 months, from 0.42 m/s to 0.36 m/s, a change which exceeds both the minimal detectable change and minimally important difference (24,25). This pattern persisted for the SPPB score. In those with the least muscle CSA limb difference (lowest tertile) the model-based estimate of the average score at 2 months was 3.77 and improved to 5.05 at 6 months, a change of 1.29 which exceeds the minimal significant change estimate (26). Those with the greatest side-to-side difference did not improve from 2 to 6 months. (Models 1 and 2, Figure 3B, p < .01). The association between muscle CSA and gait speed over time occurred in Model 3 with the adjustment for BMI and age. Lower BMI and greater fractured side CSA at 2 months were associated with better gait speed and chair rise time at 6 months. The association between the smallest side-to-side CSA difference and better SPPB score at 6 months persisted after the addition of BMI in the model. Age was not associated with muscle CSA and change in function, see Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Figure 3.

Association of muscle CSA difference with time-dependent change from 2 to 6 months (Model 1) depicted by tertiles in (A) gait speed, p = .06 (B) and SPPB score, p ≤ .01. p values are for GEE models run with continuous muscle composition and functional measures data. CSA = cross-sectional area; GEE = generalized estimating equations; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery.

The chair rise time trajectory of change from 2 to 6 months are different depending on the amount of IMAT CSA (Models 1 and 2, p ≤ .05). Those with greater IMAT CSA improved in chair rise time from 2 to 6 months (56.1–45.6 seconds). The association between IMAT CSA and chair rise time over time persisted in Model 3 with the addition of age. Younger age and less IMAT CSA on the fractured side at 2 months were associated with better chair rise time at 6 months.

Differences Between the Sexes at 2 Months and Recovery in Function From 2 to 6 Months

Given that the sample had equal numbers of males and females, and little is known about recovery of function in males, we next compared recovery of function between sexes. There was no difference in gait speed between sexes at baseline, but there was a difference in chair rise time and SPPB score, see Table 1. Based on results of Model 2, females were faster at performing the chair rise test at baseline (Figure 4A, p = .01) and scored higher on the SPPB (Figure 4B, p = .05). The trajectory in recovery in chair rise time differed between sexes (Figure 4C, p = .02). Not only were females faster in chair rise time at 2 months (50 seconds for females and 55 seconds for males) but at 6 months they remained faster, while the males were slower in this measure by an average of 3 seconds at 6 months (39 seconds for females vs 58 seconds for males). With adjustment for BMI (Model 3), the interaction between sex and fractured side CSA for gait speed became significant. Lower BMI (p ≤ .01) and greater fractured side CSA (p ≤ .01) were associated with faster gait speed in females (p ≤ .01) at 2 months. The differences between sexes at baseline in chair rise time and SPPB and trajectory of recovery of chair rise time persisted in Model 3, independent of BMI. Age was not associated with any between sex differences, see Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Figure 4.

GEE Model 2 including sex and (A) chair rise time, *p ≤ .01; (B) SPPB score, #p ≤ .05; and (C) association of sex with time-dependent change from 2 to 6 months in chair rise time, p = .02. GEE = generalized estimating equations; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery.

Discussion

Findings in this study indicate that CT-scan-based measures of muscle composition were associated both with functional performance at 2-months post hip fracture and with improvement in functional performance by 6 months’ postfracture. More specifically, the greater the muscle CSA and less fatty infiltration in the muscle, the better the performance in gait speed, chair rise time, and the SPPB at both 2- and 6-months postfracture. Furthermore, those with the smallest side-to-side difference in muscle CSA, suggesting less atrophy on the fractured side, performed better in the functional measures that were assessed in this study. In our investigation of sex differences in recovery, males performed more poorly in physical function measures at baseline and did not recover as well as females.

Our finding of a relationship between greater muscle CSA and better functional performance is similar to what has been published elsewhere in persons post hip fracture (27) and in older adults (7,22). While we found an association of greater muscle attenuation (lesser degree of fatty infiltration within the muscle tissue) with faster gait speed, this association did not persist once age was added to the model. Age and muscle attenuation were collinear, with older individuals having more fatty infiltration and this was associated with slower gait speed. However, others have found an independent association of muscle attenuation and gait speed in older adults (7,22) and in persons with rheumatoid arthritis (8). In a longitudinal study, muscle quality declined (more fatty infiltration) over time (11). Our sample was on average much older (range 65–96, mean of 79 years old) than any of these study samples (7,11,22). It is possible that age contributes to the discrepancy in results between studies. We and others (8,22), found no association between IMAT CSA and functional measures. Although recovery of function from 2 to 6 months appeared to be better in those with greater IMAT CSA, those with a greater percentage of IMAT on the fractured side still had functional deficits.

We previously reported in a smaller subset of this same cohort that muscle CSA and muscle attenuation were less, while IMAT CSA was greater at 2 months postfracture on the fractured side when compared to the nonfractured side (12). Two studies suggest that these types of changes to muscle after fracture (28) or disuse (29) may be the result of favoring the nonfractured side due to increased pain and inflammation as a result of the trauma and/or subsequent surgery on the fractured side. In our data, we found that those with the least side-to-side difference in CSA (suggesting less atrophy on the fractured side), performed best on our functional measures. Greater between limb symmetry in CSA might suggest this group did not favor their nonfractured side as much, likely benefitting functional recovery.

Our results show clinically meaningful improvements in or maintenance of function from 2 to 6 months in persons post hip fracture for several CT-based measures of muscle. Those with the least side-to-side muscle CSA difference between the limbs (meaning there was greater limb symmetry) maintained gait speed and improved in the SPPB score by 1.29 points at 6 months. The minimal significant change estimate for SPPB was 0.3–0.8 points in older adults aged 70–89 whose scores were under 10, which is similar to the population in this study (26). The improvement in chair rise time by 10 seconds exceeds the minimal detectable change of 2.5 seconds determined in older females for the upper IMAT CSA tertile group only (30).

Even though males in this study had larger thigh muscles with less fatty infiltration, females started out better in functional measures at 2 months and had better recovery at 6 months. The males in this study survived to participate at 2 and 6 months postfracture, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index was not different between males and females, suggesting that the males were probably “elite.” Despite the differences in muscle composition and similarity in health status, females in our study improved in chair rise time from 2 to 6 months by 11 seconds, whereas males performed chair rise time on average 3 seconds slower. The changes in chair rise time from 2 to 6 months for both sexes exceeded the minimal detectable change of 2.5 seconds (30). Regardless of the differences in muscle composition between the sexes, females tend to improve in function more than males post hip fracture. Di Monaco et al. (9) reported that there is a relationship between muscle mass and Barthel Index in males but not in females at 2 months postfracture and after inpatient rehabilitation suggesting the importance of muscle characteristics to functional recovery may be different between the sexes. Our results also may suggest that different interventions may be needed in males that fracture their hip.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study include that males were oversampled to allow for meaningful comparison between the sexes. The detailed CT-scan measures of muscle composition, including measurement of fat within and around the muscle has seldom been reported in this population. Our measures of function were performance-based and not self-report so that there was no recall or response bias on the part of the participant.

Some limitations of the study are worth noting. Although the study aim was to obtain 2-, 6-, and 12-month CT and function data, due to insufficient numbers of persons with both CT scan and function data at 6 and 12 months, we were underpowered for 6- and 12-month comparisons. Our sample was mostly White which limits the generalizability of our findings to other races. There was possible selection bias in that participants were more active prefracture and had faster gait speed and SPPB score at 2 months than those that did not participate. There may be a survival bias for male participants who are known to have higher morbidity and mortality than females who fracture their hips. Although there were no differences in fracture site or surgery type between males and females, we did not measure fracture severity and therefore do not know if males had worse fractures that might explain their poorer function and recovery. And finally, we were not able to control for physical activity level or therapy of the participants that occurred between time of fracture and time of measurement.

Clinical Relevance

Rehabilitation of persons post hip fracture needs to address both atrophy and fatty infiltration. Males do not recover from 2- to 6- months as well as females after fracture in this sample despite having larger and leaner muscles. Different rehabilitation strategies may be needed for males to optimize recovery of function.

Conclusion

CT-scan-based measures of muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration were associated with functional performance at 2-months post hip fracture and with improvement in functional performance by 6-months’ postfracture. Rehabilitation strategies for both sexes should address both the atrophy and the fatty infiltration (%NDM, %LDM) as both were associated with functional disability in our study. Observed sex differences in these associations suggest that rehabilitation strategies may need to be adapted by sex after hip fracture.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Laurence S. Magder, PhD, Justine Golden, MS, and Erik Barr, MS for their contributions to this article.

Contributor Information

Marty Eastlack, Department of Physical Therapy, Arcadia University, Glenside, Pennsylvania, USA.

Ram R Miller, Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Gregory E Hicks, STAR Health Sciences Complex Campus, University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware, USA.

Ann Gruber-Baldini, Division of Gerontology, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine , Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Denise L Orwig, Division of Gerontology, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine , Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Jay Magaziner, Division of Gerontology, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine , Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Alice S Ryan, Division of Gerontology and Palliative Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R37 AG09901 MERIT Award, R01 AG029315 and T32 AG00262) and by a Senior Research Career Scientist Award (ASR) from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Rehabilitation R&D (Rehab R&D) Service, P30-AG028747.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(3):465–475. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Magaziner J, Simonsick EM, Kashner TM, Hebel JR, Kenzora JE. Predictors of functional recovery one year following hospital discharge for hip fracture: a prospective study. J Gerontol. 1990;45(3):M101–M107. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.3.m101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Magaziner J, Hawkes W, Hebel JR, et al. Recovery from hip fracture in eight areas of function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(9):M498–M507. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.9.M498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Keene GS, Parker MJ, Pryor GA. Mortality and morbidity after hip fractures. Br Med J. 1993;307(6914):1248–1250. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6914.1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hawkes WG, Wehren L, Orwig D, Hebel JR, Magaziner J. Gender differences in functioning after hip fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(5):495–499. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.5.495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Visser M, Harris TB, Fox KM, et al. Change in muscle mass and muscle strength after a hip fracture: relationship to mobility recovery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(8):M434–M440. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.8.M434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Visser M, Kritchevsky SB, Goodpaster BH, et al. Leg muscle mass and composition in relation to lower extremity performance in men and women aged 70 to 79: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(5):897–904. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50217.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khoja SS, Moore CG, Goodpaster BH, Delitto A, Piva SR. Skeletal muscle fat and its association with physical function in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2018;70(3):333–342. doi: 10.1002/acr.23278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Di Monaco M, Vallero F, Di Monaco R, Tappero R, Cavanna A. Muscle mass and functional recovery in men with hip fracture. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(10):818–825. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318151fec7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Di Monaco M, Castiglioni C. Weakness and low lean mass in women with hip fracture: prevalence according to the FNIH criteria and association with the short-term functional recovery. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2017;40(2):80–85. doi: 10.1519/jpt.0000000000000075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goodpaster BH, Park SW, Harris TB, et al. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(10):1059–1064. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.10.1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miller RR, Eastlack M, Hicks GE, et al. Asymmetry in CT scan measures of thigh muscle 2 months after hip fracture: the Baltimore Hip Studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(6):753–756. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stevens JA, Rudd R. The impact of decreasing U.S. hip fracture rates on future hip fracture estimates. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(10):2725–2728. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2375-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Collaborators GF. Global, regional, and national burden of bone fractures in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2:e580–e592. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00172-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Orwig D, Hochberg MC, Gruber-Baldini AL, et al. Examining differences in recovery outcomes between male and female hip fracture patients: design and baseline results of a prospective cohort study from the Baltimore Hip Studies. J Frailty Aging. 2018;7(3):162–169. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2018.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48(8):314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dipietro L, Caspersen CJ, Ostfeld AM, Nadel ER. A survey for assessing physical activity among older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25(5):628–642. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199305000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goodpaster BH, Kelley DE, Thaete FL, He J, Ross R. Skeletal muscle attenuation determined by computed tomography is associated with skeletal muscle lipid content. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89(1):104–110. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.1.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goodpaster BH, Thaete FL, Kelley DE. Composition of skeletal muscle evaluated with computed tomography. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;904(1):18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06416.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.M85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reinders I, Murphy RA, Koster A, et al. Muscle quality and muscle fat infiltration in relation to incident mobility disability and gait speed decline: the age, gene/environment susceptibility-Reykjavik study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(8):1030–1036. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. doi: 10.1093/biomet/73.1.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Palombaro KM, Craik RL, Mangione KK, Tomlinson JD. Determining meaningful changes in gait speed after hip fracture. Physical Therapy. 2006;86(6):809–816. doi: 10.1093/ptj/86.6.809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alley DE, Hicks GE, Shardell M, et al. Meaningful improvement in gait speed in hip fracture recovery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(9):1650–1657. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03560.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kwon S, Perera S, Pahor M, et al. What is a meaningful change in physical performance? Findings from a clinical trial in older adults (the LIFE-P study). J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13(6):538–544. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0104-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Briggs RA, Houck JR, Drummond MJ, Fritz JM, Lastayo PC, Marcus RL. Muscle quality improves with extended high-intensity resistance training after hip fracture. J Frailty Aging. 2018;7(1):51–56. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2017.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mikkola T, Sipilä S, Portegijs E, et al. Impaired geometric properties of tibia in older women with hip fracture history. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(8):1083–1090. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0352-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taaffe DR, Henwood TR, Nalls MA, Walker DG, Lang TF, Harris TB. Alterations in muscle attenuation following detraining and retraining in resistance-trained older adults. Gerontology. 2009;55(2):217–223. doi: 10.1159/000182084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goldberg A, Chavis M, Watkins J, Wilson T. The five-times-sit-to-stand test: validity, reliability and detectable change in older females. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24(4):339–344. doi: 10.1007/BF03325265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.