Abstract

Metastatic disease to the breast is rare. Melanoma and lymphoma are the most common primary tumors metastasizing to the breast, and breast metastasis from a primary lung neoplasm is uncommon. It can be difficult to distinguish metastatic disease from primary breast cancer clinically. Immunohistochemistry, combined with further diagnostic imaging, play important roles in identifying the primary origin of the malignancy. An accurate diagnosis is imperative for therapeutic planning, and further workup should be considered for unusual cytological patterns. In this report, three cases of pulmonary metastasis to the breast with atypical clinical presentations are presented and discussed.

Keywords: Breast metastasis, Extra-mammary neoplasm, Lung cancer

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in United States with a total incidence of cancer at any site estimated at 442.4 per 100,000 people in 2017.1 Of all sites, breast cancer has the highest reported incidence in females at 30% and is second to lung cancer (25%) as the most common cause of cancer-related deaths in females at 14%.2 Approximately one in eight U.S. women will develop invasive breast cancer over their lifetime. The lifetime risk of breast cancer in U.S. men is about 1 in 883.3

While approximately 6% to 10% of breast cancer is metastatic at presentation,4 metastatic disease to the breast from extra-mammary sites is rare and accounts for 0.5% to 3% of all cancers in the breast. The most common primary sources of metastatic disease to the breast are malignant melanoma, lymphoma, and leukemia.5 In contrast, breast metastases from primary lung cancer is very rare at <0.5%.6 Approximately, 25% of patients with metastatic disease to the breast present with a breast mass as the initial presentation.5 While there are some reports of metastatic disease to the breast being small, superficially located, poorly defined, and irregular without calcification on mammography and ultrasonography,7 these features are not specific to secondary malignancies of the breast, and thus can be confused with primary breast neoplasm.

An accurate diagnosis is imperative for therapeutic planning due to the disparate workup, management, and outcomes of primary compared to secondary breast malignancies. Immunohistochemistry and diagnostic imaging are essential tools for identifying the primary origin of malignancy, and further workup can be helpful in identifying unusual cytological patterns indicative of alternative primary. In this report, three cases of atypical pulmonary metastasis to the breast are presented with particular emphasis on the abnormalities identified during routine imaging and immunohistochemical analysis.

Case 1: The Atypical Location

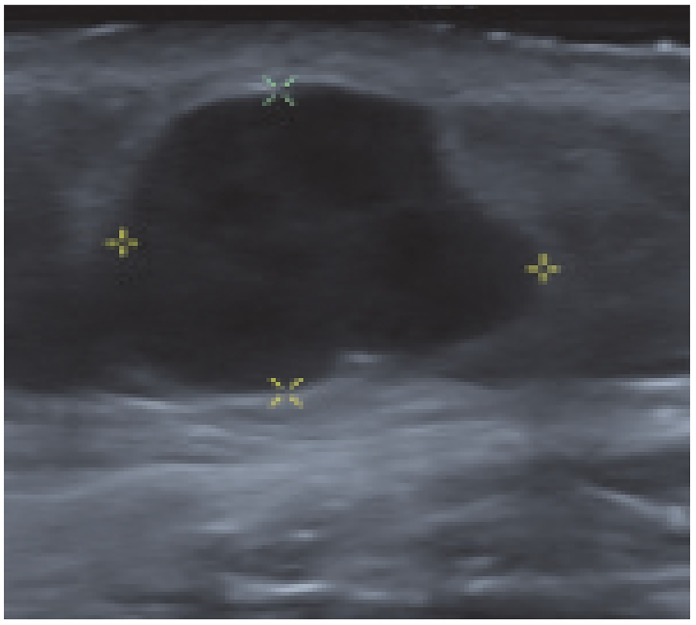

A female patient, aged 65 years, presented for evaluation of a right breast mass at the inframammary crease. There were no concerns identified on the mammographic component of her diagnostic studies; however, on ultrasound she was found to have a 1.4 × 1.3 × 1.3 cm area of abnormality (Figure 1), at the 5 o’clock position, 7 cm from nipple, which was hypoechoic, heterogeneous, irregular, and very suspicious and was classified as breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS) 5. Further ultrasound of the right axilla highlighted a single right axillary lymph node with a few focally lobulated cortex. Ultrasound-guided biopsy identified an estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor 2 (Her2) negative invasive adenocarcinoma with mucinous differentiation and a benign axillary lymph node. The tumor was initially thought to be most consistent with breast ductal adenocarcinoma of intermediate grade with necrosis, and the patient was referred for a surgical evaluation. Given the atypical location and atypical pathology, a multidisciplinary discussion was held with medical oncology and pathology, which resulted in pursuing a computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis to rule out a different primary source of her tumor. The patient was found to have a 6.7 × 6.7 × 5.5cm left hilar mass encasing the left upper lobe bronchovascular structures and abutting the mediastinum including the aorta and left main pulmonary artery (Figure 2). There were multiple lytic bone lesions consistent with bone metastases involving the spine, manubrium, right scapula, multiple ribs, and the bony pelvis. The index presenting mass was noted as a 1.6 cm subcutaneous nodule in the low anterior right chest. A subsequent positron emission tomography (PET)/CT was performed that re-demonstrated the above suspicion of metastatic lung cancer with intense activity to the left anterosuperior hilar mass, left intrapulmonary nodules, pleural studding, large left pleural effusion, 2 subcutaneous foci (posterior right shoulder and inferior breast) and numerous skeletal lytic lesions. The patient was trialed on different regimens including platinum-based chemotherapy and immunotherapy with continued disease progression and ultimately passed away less than a year after presentation secondary to hypoxic hypercapnic respiratory failure.

Figure 1.

1.4 × 1.3 × 1.3 cm irregular hypoechoic mass with irregular margins below the inframammary.

Figure 2.

Large anteriosuperior hilar mass abutting the mediastinum and encasing the bronchovascular structures to the left upper lobe. Mass at inframammary crease noted as 1.6 cm subcutaneous nodule (red arrow).

Case 2: The Multiple Breast Lesions

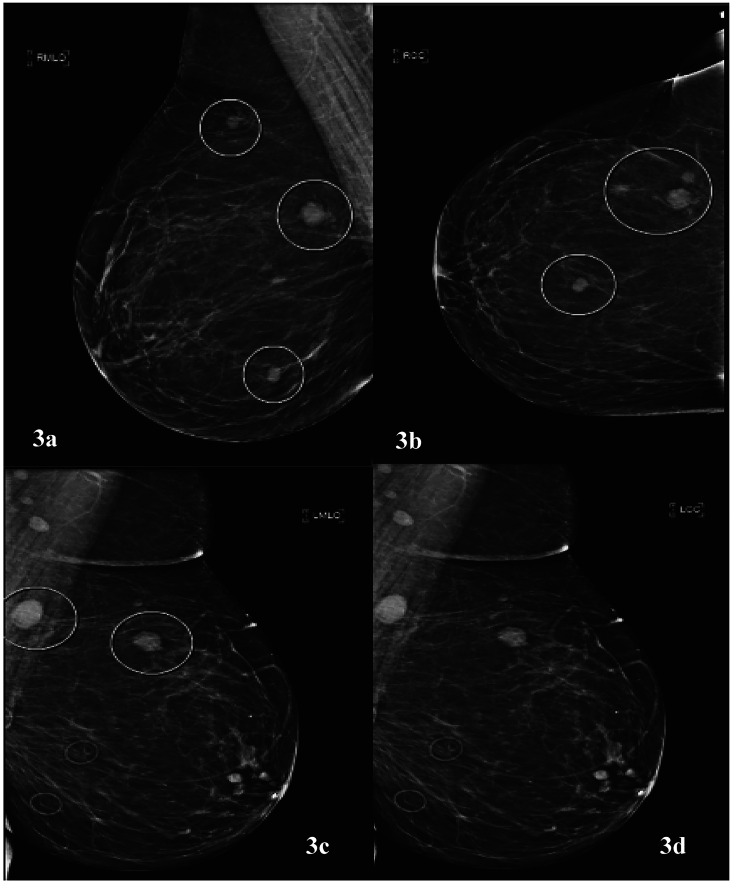

A female patient, aged 74 years, with history of tobacco abuse and T4b melanoma of the right cheek presented with a left breast mass found on self-examination. Of note, the patient had undergone wide local excision of melanoma and sentinel lymph node biopsy with negative margins and benign lymph nodes on pathology followed by adjuvant interferon therapy 13 years prior to current presentation. Diagnostic breast imaging with mammography and ultrasound was pursued. The patient was found to have several irregular high-density masses in bilateral breasts at approximately 6 o’clock, 10 o’clock, and 11 o’clock in the right breast and at 1 o’clock and 11 o’clock in the left breast (Figure 3). An ultrasound-guided biopsy was performed of the 6 o’clock right breast and 1 o’clock left breast lesion, and the patient was referred for surgical evaluation with initial index of suspicion for metastatic melanoma. The patient complained of increased fatigue over the last 2 years; however, review of systems otherwise was unremarkable, including no respiratory symptoms or uncharacteristic headaches. On physical examination, she was noted to have some fullness in the right thyroid gland and an abnormal breast examination. The pathology finding of metastatic poorly differentiated carcinoma was discussed with pathology. Melanoma cocktail, S-100, CK20, GATA-3, P40, CD31, CD34, PAX8, thyroglobulin, and napsin staining were negative. The tumor was positive for cytokeratin cocktail, CK7, and TTF-1. Based on immunohistochemistry, we ruled out metastatic melanoma and the possibility of metastatic thyroid carcinoma. Given unknown primary malignancy, a PET/CT was performed that showed a large right perihilar mass (Figure 4) with multiple metastatic lesions including, but not limited t,o separate right upper lung mass, abnormal right thyroid region, multiple bilateral breast legions, mesenteric/peritoneal lesions, multiple skeletal metastasis, and brain abnormalities. A follow up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain (Figure 5) showed at least 15 enhancing parenchymal brain masses including right cerebellum and left frontal lobe consistent with metastatic disease. The patient received radiation therapy to the brain, one cycle of chemotherapy with pemetrexed and carboplatin and two cycles of immunotherapy based treatment with pembrolizumab with drastic progression. She had significant functional decline and asthenia secondary to radiation-induced leukoencephalopathy and was transitioned to comfort focused care with hospice. The patient died within 6 months of diagnosis.

Figure 3.

(a) Mediolateral oblique and (b) craniocaudal view demonstrating multiple irregular high density masses in the right breast at 6 o’clock, 10 o’clock, and 11 o’clock. (c) Mediolateral oblique and (d) craniocaudal view demonstrating irregular masses at 11 o’clock and 1 o’clock in the left breast.

Figure 4.

(Positron emission tomography/computed tomography with extensive disease including but not limited to large right perihilar mass, multiple lesions in the breasts bilaterally, abnormal right thyroid lobe region, and multiple mesenteric and skeletal metastasis.

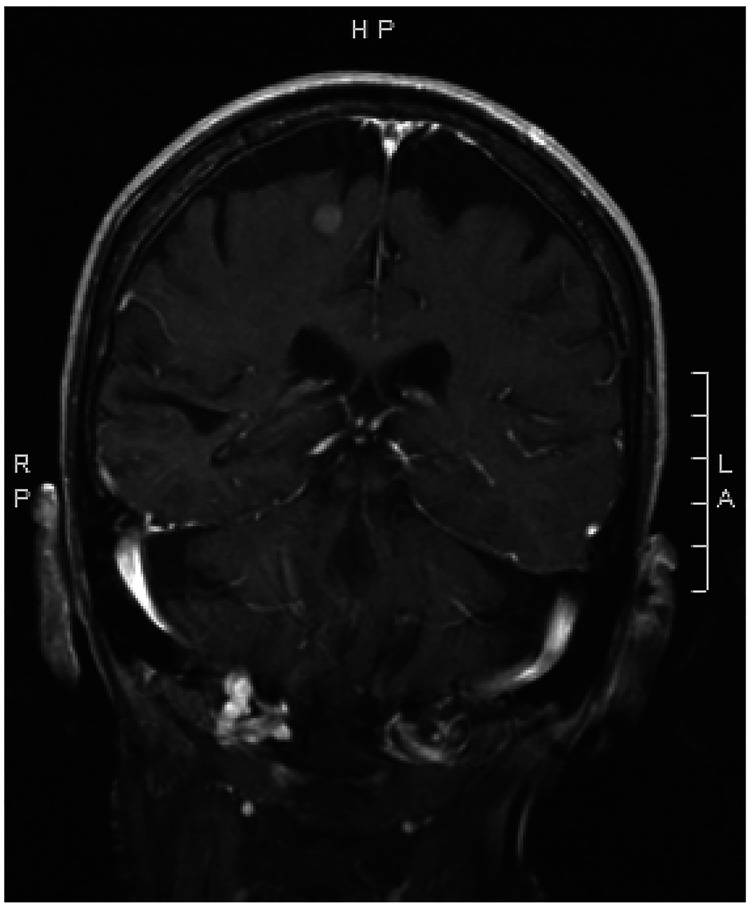

Figure 5.

Small widely metastatic lesions in the brain on MRI.

Case 3: The Indistinguishable Lesion

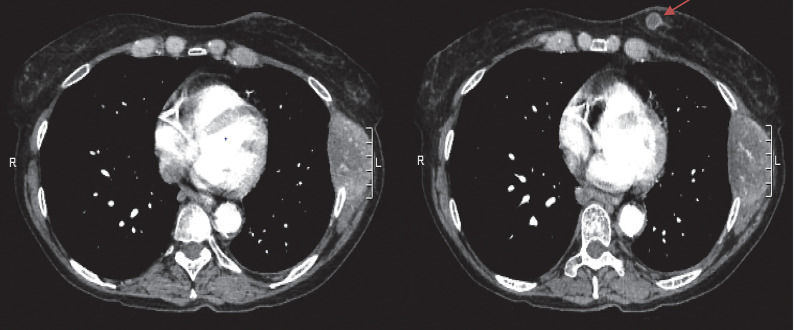

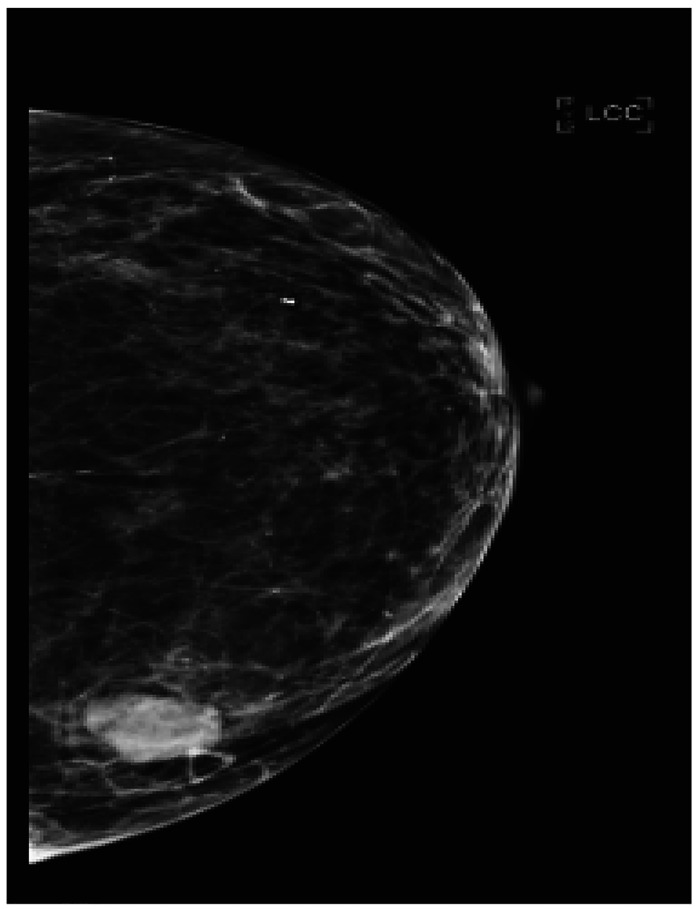

A female patient, aged 65 years, presented with few weeks history of “smoker’s cough” and associated left anterior chest wall pain aggravated by moving. A chest radiograph was performed that showed destruction of the 7th left rib with abnormal density within the left lateral chest wall. A follow-up CT of the chest (Figure 6) showed a 1.3 cm left breast, with what was initially thought to be evidence of metastatic breast carcinoma, with the largest lesion in the lateral left 7th rib measuring up to 5.9 cm and prominent lymphadenopathy in bilateral axillae, mediastinum, and right hilar region. Left adrenal metastasis was also noted. The mass on CT was revisualized on bilateral breast mammography (Figure 7). Left breast ultrasound showed a mass at the 9 o’clock position 9cm from nipple with irregular margins involving the basal layer of epidermis. There were two other oval shaped circumscribed lesions at 1 o’clock and 9 o’clock that were thought to be intramamary lymph nodes. Ultrasound guided biopsy of breast mass demonstrated poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. The mass was estrogen receptor positive but progesterone and HER2 negative. While the mass was CK7-positive/CK20-negative, positive TTF-1 and negative GATA-3 favored malignancy from a lung primary over metastatic breast cancer.8 Fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology of the chest wall mass had concordant pathology. The patient was evaluated by medical oncology and further molecular testing was performed with minimal PD-L1 expression and negative for other tested mutation. Conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy versus supportive care were discussed. In the interim, MRI of the brain (Figure 8) was prompted due to patient’s complaints of headaches that showed a solitary metastasis in the right frontal lobe. The patient underwent two cycles of systemic therapy including bevacizumab, pemetrexed, and cisplatin. She also received palliative whole brain radiation. Unfortunately, she demonstrated disease progression on interval imaging (Figure 9) and was subsequently lost to follow up.

Figure 6.

Computed tomography of the chest demonstrating a destructive soft tissue mass in the lateral left 7th rib measuring 5.9 × 5.8 × 4.2 cm. 1.3 cm left breast mass (red arrow).

Figure 7.

Craniocaudal view of left breast with a 2 cm irregular mass at 9 o’clock.

Figure 8.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showing a solitary metastasis involving right frontal lobe.

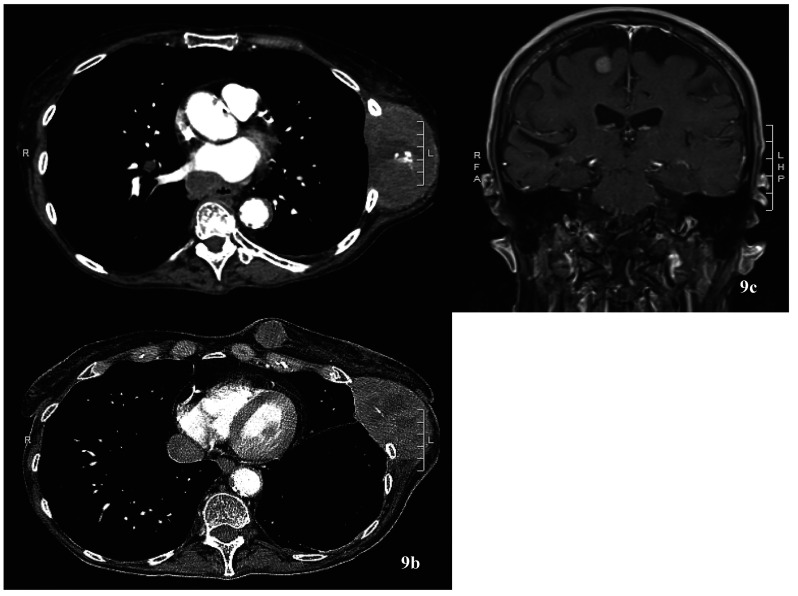

Figure 9.

Computed tomography of the chest (a & b) with disease progression and left chest wall mass now measuring 9.5 × 5.3 cm and left breast mass now 2.4 × 2.3 cm (from 1.3 × 1.2cm). (c) Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain with interval enlargement of the right frontal enhancing lesion, 0.9 × 1 cm (was 0.6 cm).

Discussion

Initial evaluation, treatment, and prognosis of metastatic breast cancer varies significantly from extra-mammary neoplasms like primary lung adenocarcinoma with breast metastasis, as in our three patients. The 5-year survival of stage IV breast cancer has been reported around 28.1%,1 while that of metastatic lung cancer a grim 5.8%.9 While often described as small, superficially located, poorly defined, and irregular without calcification lesions, breast metastasis from extra-mammary neoplasms can have variable clinical and radiologic manifestation. There should be a high index of suspicion for metastatic disease when encountering atypical location and pathology.

In our patient described in case 1, her breast mass was found to be in the inframammary crease beyond the glandular breast tissue, thus prompting further workup. The role of immunohistochemistry is pivotal in identifying the primary source of malignancy. For the patient described in case 2, we were able to rule out two clinical differentials of metastatic melanoma and thyroid cancer due to negative S-100, and PAX8, and thyroglobulin stains, respectively. The diagnosis of primary lung adenocarcinoma was based on the findings of CK-7 and TTF-1 positivity. The latter was similar for the patient described in case 3. While not indicated in the initial work up of primary breast carcinoma unless prompted by symptomology, additional work up with PET/CT or CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis should be considered in such cases. Accurately diagnosing the lesions as metastatic foci rather than primary breast malignancy helps avoid unwarranted surgical interventions. A multidisciplinary discussion between pathology and medical and surgical oncology is crucial to guide workup and therapeutic planning.

References

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al., eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2017, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD; Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2017/ based on November 2019 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A.. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7-30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Breast Cancer Statistics . Breastcancer.org. 27 Jan. 2020, Available at: www.breastcancer.org/symptoms/understand_bc/statistics.

- 4.Incidence and Incidence Rates. Metastatic Breast Cancer Network. 13 Oct. 2019, Available at: mbcn.org/incidence-and-incidence-rates/.

- 5.Babu KS, Roberts F, Bryden F, et al. Metastases to breast from primary lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(4):540-542. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819c8556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramar K, Pervez H, Potti A, Mehdi S.. Breast metastasis from non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2003;20(2):181-184. doi: 10.1385/MO:20:2:181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramar K, Pervez H, Potti A, Mehdi S.. Breast metastasis from non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2003;20(2):181-184. doi: 10.1385/MO:20:2:181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shield PW, Crouch SJ, Papadimos DJ, Walsh MD.. Gata3 Immunohistochemical Staining is A Useful Marker for Metastatic Breast Carcinoma in Fine Needle Aspiration Specimens. J Cytol. 2018;35(2):90-93. doi: 10.4103/JOC.JOC_132_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cancer of the Lung and Bronchus - Cancer Stat Facts. SEER- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NIH National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. Available at: seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html. [Google Scholar]