Abstract

Background

Treatment decisions about oral anticoagulants (OACs) for atrial fibrillation (AF) are complex in older care home residents.

Aim

To explore factors associated with OAC prescription.

Design and setting

Retrospective cohort study set in care homes in Wales, UK, listed in the Care Inspectorate Wales Registry 2017/18.

Method

Analysis of anonymised individual-level electronic health and administrative data was carried out on people aged ≥65 years entering a care home between 1 January 2003 and 31 December 2018, provisioned from the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage Databank.

Results

Between 2003 and 2018, 14 493 people with AF aged ≥65 years became new residents in care homes in Wales and 7057 (48.7%) were prescribed OACs (32.7% in 2003 compared with 72.7% in 2018) within 6 months before care home entry. Increasing age and prescription of antiplatelet therapy were associated with lower odds of OAC prescription (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.96 per 1-year age increase, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.95 to 0.96 and aOR 0.91, 95% CI = 0.84 to 0.98, respectively). Conversely, prior venous thromboembolism (aOR 4.06, 95% CI = 3.17 to 5.20), advancing frailty (mild: aOR 4.61, 95% CI = 3.95 to 5.38; moderate: aOR 6.69, 95% CI = 5.74 to 7.80; and severe: aOR 8.42, 95% CI = 7.16 to 9.90), and year of care home entry from 2011 onwards (aOR 1.91, 95% CI = 1.76 to 2.06) were associated with higher odds of an OAC prescription.

Conclusion

There has been an increase in OAC prescribing in older people newly admitted to care homes with AF. This study provides an insight into the factors influencing OAC prescribing in this population.

Keywords: anticoagulants; atrial fibrillation; long-term care; nursing homes; practice patterns, physicians’; primary health care

INTRODUCTION

Atrial fibrillation (AF) disproportionately affects older people, with its prevalence increasing in parallel to population growth and ageing.1,2 Older care home residents represent a growing group of people with AF. Previous estimates for the proportion of older care home residents with a diagnosis of AF have ranged from 7% to 38%.3–5

Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of stroke four-to fivefold;6 therefore, stroke prevention is the cornerstone of AF management. This focuses on the prescription of oral anticoagulants (OACs);7 however, there is evidence of underprescribing of OACs in care home residents.3 The prevalence of anticoagulant use for AF in care homes ranges from 17% to 68% across multiple studies.3,5,8 With concerns of iatrogenic harm and doubt of the net clinical benefit of treatment, often clinicians face the dilemma of a ‘treatment– risk paradox’ in this vulnerable group. The risk of adverse events is heightened because of the complex interplay between altered pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles, frailty, dementia, falls risk, polypharmacy, multimorbidity, and an exponential increase in stroke and bleeding risk with advancing age.9,10 However, the consequences of non-prescription of anticoagulation can be catastrophic; AF-related strokes are often more severe than strokes related to other causes, and people who have an AF-related stroke are more likely to die, experience chronic disability, and require constant nursing care.11–13

How this fits in

| Available data on factors that influence the decision to prescribe anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in care home residents is conflicting. This study adds to the body of evidence to suggest that advancing age and concomitant antiplatelet therapy are barriers to anticoagulant prescription in older people newly admitted to care homes. Targeted educational tools on anticoagulant prescribing in older people with atrial fibrillation and an indication for antiplatelet therapy (for example, peripheral vascular disease, ischaemic stroke, and acute coronary syndrome) are needed. |

The latest European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on AF state there is sufficient evidence to support OAC prescribing in older people based on a meta- analysis of landmark trials on non- vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) including people aged ≥75 years.7,14–19 Results from other trials also support the use of warfarin for stroke prevention in people aged ≥75 years with AF.20,21 The ESC guidelines also emphasise that frailty, falls risk, and multimorbidity are not sufficient justification for not prescribing OACs in those who are eligible for treatment.7 This study aims to elucidate the factors associated with OAC prescription in older people aged ≥65 years newly admitted to care homes in Wales.

METHOD

Study design

This was a retrospective cohort study using anonymised linked data from the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) Databank on CARE home residents with AF (any subtype or atrial flutter) in Wales (SAIL CARE-AF), following the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely- collected health Data (RECORD) 2015 guidelines (see Supplementary Table S1).22

Data sources

This study utilised anonymised, individual- level population-scale routinely collected electronic health record and administrative data for the population of Wales available within the SAIL Databank.23–25 The data sources included the Welsh Demographic Service Dataset,26 the Welsh Longitudinal General Practice (WLGP),27 and the Patient Episode Database for Wales (PEDW).28 Data were extracted from the PEDW and WLGP using International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) and Read version 2 codes, respectively (see Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). The WLGP version available to and used by this study contains primary care data with ∼80% coverage of patients and general practices in Wales, and PEDW secondary care data with 100% coverage of patients and services.

Participants

The (CARE) care home data source within the SAIL Databank is derived from care home information available from the Care Inspectorate Wales (CIW) registry with an assigned Residential Anonymous Linking Field.29 This is linked to anonymised address data for individual participants.30–32 The CIW registry 2017/18 was used in this study. Data were extracted for people aged ≥65 years on care home entry with a record of AF (any subtype or atrial flutter) within the PEDW or WLGP (see Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). All participants had a minimum of 12 months data coverage within the WLGP before moving to a care home between 1 January 2003 and 31 December 2018. The cohort was restricted to the first care home entry date to prevent participants being accounted for more than once if they moved in and out of different care homes.

Covariates

For information on study covariates, see Supplementary Appendix S1.

Outcomes

The outcome of interest was OAC prescription or non-prescription between 6 months before care home entry and the date of care home entry. This was used as a proxy for prescription/non-prescription at the point of care entry.

Statistical analyses

Unadjusted logistic regression models were used to explore the association between all covariates and OAC prescription or non-prescription. Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) were reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P-values. Following the process of purposeful selection, any covariate that was not significant at the level 0.1 and not judged to be a potential confounder by the authors was excluded from the multivariate model.33 This threshold was used because conventional significance levels such as 0.05 can fail to identify important variables.34 Similar covariates were grouped together and multicollinearity was assessed using the variance inflation factor (see Supplementary Appendix S1). Results were reported as adjusted ORs (aORs) with 95% CIs and P-values.

For the covariate major bleeding, a sensitivity analysis was carried out to exclude people that had evidence of OAC prescription and a major bleeding event (defined using ICD-10 codes listed in Supplementary Table S2) within 6 months before care home entry. This attempted to account for any association that may have arisen because of bleeding caused by OACs. All analyses were completed using Stata (version 15).

Research ethics and information governance

For information on research ethics and information governance see Supplementary Appendix S1.

RESULTS

Characteristics of study cohort on care home entry

Between 2003 and 2018, 14 493 people with AF aged ≥65 years who had ≥12 months of primary care data became new residents in care homes in Wales (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S1). The median age of the cohort was 87.0 years (interquartile range [IQR] 82.6–91.2) and 5103 (35.2%) were male.

Table 1.

Characteristics of adults with atrial fibrillation aged ≥65 years on care home entry (2003–2018) within the SAIL Databank, by prescription of oral anticoagulation

| Characteristics | All participants with AF (N = 14 493) | Participants with AF not prescribed OACs (n = 7436) | Participants with AF prescribed OACsa (n = 7057) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 87.0 (82.6–91.2) | 87.9 (83.4–92.0) | 86.2 (81.9–90.2) | <0.001 |

| Age category, years, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 65–74 | 770 (5.3) | 341 (4.6) | 429 (6.1) | |

| 75–84 | 4682 (32.3) | 2117 (28.5) | 2565 (36.3) | |

| 85–94 | 7859 (54.2) | 4157 (55.9) | 3702 (52.5) | |

| ≥95 | 1182 (8.2) | 821 (11.0) | 361 (5.1) | |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 5103 (35.2) | 2427 (32.6) | 2676 (37.9) | <0.001 |

| WIMD quintile, n (%) | 1.000 | |||

| 1 (most deprived) | 2459 (17.0) | 1270 (17.2) | 1189 (17.1) | |

| 2 | 3053 (21.3) | 1567 (21.2) | 1486 (21.4) | |

| 3 | 3435 (23.9) | 1774 (24.0) | 1661 (23.9) | |

| 4 | 2842 (19.8) | 1468 (19.9) | 1374 (19.8) | |

| 5 (least deprived) | 2554 (17.8) | 1316 (17.8) | 1238 (17.8) | |

| Missing | 150 (1.0) | 41 (0.3) | 109 (0.8) | |

|

| ||||

| Frailty, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No frailty | 1864 (12.9) | 1600 (21.5) | 264 (3.7) | |

| Mild | 3714 (25.6) | 2142 (28.8) | 1572 (22.3) | |

| Moderate | 5145 (35.5) | 2329 (31.3) | 2816 (39.9) | |

| Severe | 3770 (26.0) | 1365 (18.4) | 2405 (34.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Stroke risk, CHA2DS2-VASc score,b median (IQR) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Bleeding risk, HAS-BLED score,b median (IQR) | 3 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Social history, n (%) | ||||

| Smoking history | 3996 (27.6) | 1620 (21.8) | 2376 (33.7) | <0.001 |

| Alcoholism | 1223 (8.4) | 513 (6.9) | 710 (10.1) | <0.001 |

| Heavy drinker | 224 (1.5) | 118 (1.6) | 106 (1.5) | 0.680 |

|

| ||||

| Comorbiditiesc | ||||

| Any stroke | 2929 (20.2) | 1248 (16.8) | 1681 (23.8) | <0.001 |

| Stroke (unknown origin) | 618 (4.3) | 266 (3.6) | 352 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 2232 (15.4) | 932 (12.5) | 1300 (18.4) | <0.001 |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 336 (2.3) | 144 (1.9) | 192 (2.7) | 0.002 |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 796 (5.5) | 361 (4.9) | 435 (6.2) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1131 (7.8) | 560 (7.5) | 571 (8.1) | 0.210 |

| Heart failure | 4204 (29.0) | 1796 (24.2) | 2408 (34.1) | <0.001 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 162 (1.1) | 93 (1.3) | 69 (1.0) | 0.120 |

| Vascular dementia | 552 (3.8) | 275 (3.7) | 277 (3.9) | 0.480 |

| Other dementia or unspecified | 542 (3.7) | 306 (4.1) | 236 (3.3) | 0.014 |

| Asthma | 1214 (8.4) | 512 (6.9) | 702 (9.9) | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1794 (12.4) | 811 (10.9) | 983 (13.9) | <0.001 |

| Other pulmonary disease | 9 (0.1) | <5 (<1) | 7 (0.1) | 0.081 |

| Peptic ulcer | 422 (2.9) | 215 (2.9) | 207 (2.9) | 0.880 |

| Diabetes | 728 (5.0) | 299 (4.0) | 429 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 1052 (7.3) | 457 (6.1) | 595 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| Liver disease | 45 (0.3) | 25 (0.3) | 20 (0.3) | 0.570 |

| Cancer | 2236 (15.4) | 1055 (14.2) | 1181 (16.7) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 6967 (48.1) | 3125 (42.0) | 3842 (54.4) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 1765 (12.2) | 679 (9.1) | 1086 (15.4) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 855 (5.9) | 352 (4.7) | 503 (7.1) | <0.001 |

| Aortic plaque | 8 (0.1) | <5 (<1) | 5 (0.1) | 0.430 |

| Major bleeding | 2635 (18.2) | 1095 (14.7) | 1540 (21.8) | <0.001 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 464 (3.2) | 93 (1.3) | 371 (5.3) | <0.001 |

Prescription within 6 months before care home entry used as a proxy for prescription at the point of care home entry.

CHA2DS2-VASc, stroke risk assessment scoring one point each for female sex, age 65–74 years, history of heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, vascular disease, and two points each for history of stroke/transient ischaemic attack/venous thromboembolism and age ≥75 years. HAS-BLED, bleeding risk assessment scoring one point each for age >65 years, uncontrolled hypertension, liver disease, renal disease, harmful alcohol use, stroke history, prior major bleeding or a predisposition to bleeding, labile international normalised ratio, and medication usage predisposing to bleeding. See Supplementary Tables S4 and S5 for definitions of the HAS-BLED and CHA2DS2-VASc risk assessment scores used in this study.

Younger-onset dementia not reported on because of small numbers and risk of resident identification.

AF = atrial fibrillation. IQR = interquartile range. OAC = oral anticoagulation. SAIL = Secure Anonymised Information Linkage. WIMD = Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation.

Of the total cohort with AF, 7057 (48.7%) had a record of OAC prescription within 6 months before care home entry (Table 1). There were 5734 (81.3%) residents on vitamin K antagonist (VKA), 623 (8.8%) on NOACs, and 700 (9.9%) that switched between VKA or NOAC therapy in the 6 months preceding care home entry (data not shown).

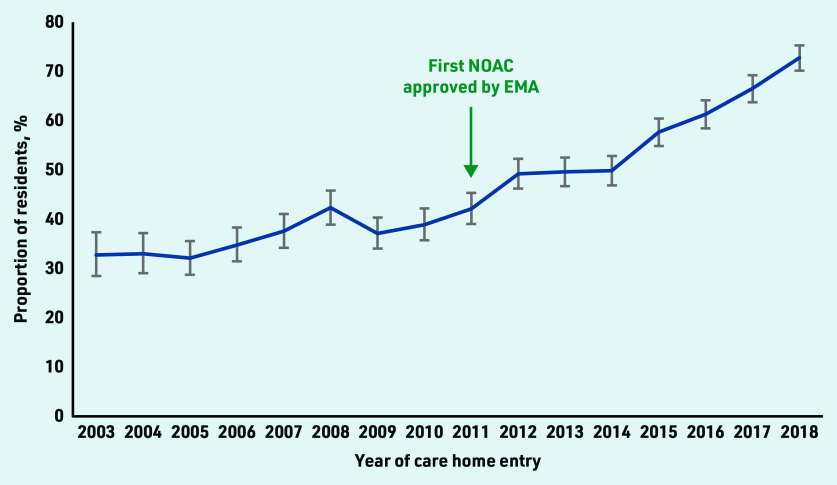

The proportion of residents prescribed OACs increased from 32.7% in 2003 to 72.7% in 2018 (Figure 1). In 2003, all residents were on VKA. In 2018, 385 (33.0%) were on VKA, 228 (19.5%) were on NOACs, and 236 (20.2%) changed between VKA or NOACs before care home entry (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Proportion of care home residents aged ≥65 years with atrial fibrillation prescribed an oral anticoagulant within 6 months before care home entry between 2003 and 2018.

EMA = European Medicines Agency. NOAC = non- vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant.

Residents prescribed OACs were slightly younger (median age 86.2 years, IQR 81.9– 90.2 versus 87.9 years, IQR 83.4– 92.0) and a higher proportion were male (37.9% versus 32.6%). The median stroke risk (CHA2DS2-VASc score 4, IQR 3–5) at care home entry was the same in residents prescribed OACs and those residents not prescribed OACs, with a slightly higher median bleeding risk at care home entry for those prescribed OACs (HAS-BLED score 3, IQR 2–3 versus 2, IQR 2–3, respectively) (Table 1).

There was a greater proportion of residents not prescribed OACs on care home entry who were classified as non- frail (21.5% versus 3.7%), whereas more residents categorised with moderate (39.9% versus 31.3%) or severe frailty (34.1% versus 18.4%) were prescribed OACs (Table 1). Severely frail residents more commonly had a history of stroke, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), myocardial infarction, hypertension, heart failure (HF), peripheral vascular disease (PVD), venous thromboembolism (VTE), and diabetes compared with those who were mildly or moderately frail. This translated into a higher median CHA2DS2- VASc score of 5 (IQR 4–5) for severely frail residents compared with 4 (IQR 3–5) for mild or moderately frail residents (Table 2).

Table 2.

Advancing frailty and the prevalence of stroke risk factors in care home residents aged ≥65 years with atrial fibrillation

| Category | Frailty category on care entrya | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| No frailty (n = 1864) | Mild frailty (n = 3714) | Moderate frailty (n = 5145) | Severe frailty (n = 3770) | |

| Stroke risk factors on care entry, n (%)b | ||||

| Age category, years | ||||

| 65–74 | 109 (5.8) | 253 (6.8) | 242 (4.7) | 166 (4.4) |

| 75–84 | 638 (34.2) | 1249 (33.6) | 1603 (31.2) | 1192 (31.6) |

| 85–94 | 962 (51.6) | 1899 (51.1) | 2856 (55.5) | 2142 (56.8) |

| ≥95 | 155 (8.3) | 313 (8.4) | 444 (8.6) | 270 (7.2) |

| Sex, male | 641 (34.4) | 1375 (37.0) | 1854 (36.0) | 1233 (32.7) |

| Heart failure | 297 (15.9) | 731 (19.7) | 1525 (29.6) | 1651 (43.8) |

| Hypertension | 258 (13.8) | 1480 (39.8) | 2810 (54.6) | 2419 (64.2) |

| Diabetes | 46 (2.5) | 83 (2.2) | 215 (4.2) | 384 (10.2) |

| Myocardial infarction | 135 (7.2) | 188 (5.1) | 380 (7.4) | 428 (11.4) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 36 (1.9) | 142 (3.8) | 287 (5.6) | 390 (10.3) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 38 (2.0) | 82 (2.2) | 171 (3.3) | 173 (4.6) |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 85 (4.6) | 165 (4.4) | 267 (5.2) | 279 (7.4) |

| Strokec | 331 (17.8) | 761 (20.5) | 1048 (20.4) | 789 (20.9) |

|

| ||||

| Stroke risk assessment on care home entry | ||||

| CHA2DS2-VASc category,d n (%) | ||||

| Low moderate | 24 (1.3) | 42 (1.1) | 22 (0.4) | 9 (0.2) |

| Moderate high | 1840 (98.7) | 3672 (98.9) | 5123 (99.6) | 3761 (99.8) |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score,d median (IQR) | 3 (3–4) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 5 (4–5) |

Defined using the eFI: no frailty (eFI 0 0.12); mild (eFI >0.12 0.24); moderate (eFI >0.24 0.36); or severe (eFI >0.36) frailty.

Aortic plaque not reported on as a stroke risk factor because of small numbers and risk of resident identification.

Including ischaemic, haemorrhagic stroke, and stroke of unknown origin.

CHA2DS2-VASc, stroke risk assessment scoring one point each for female sex, age 65–74 years, history of heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, vascular disease, and two points each for history of stroke/transient ischaemic attack/venous thromboembolism and age ≥75 years.

eFI = electronic Frailty Index. IQR = interquartile range.

Factors associated with OAC prescription

From unadjusted analyses (Table 3), factors associated with OAC non-prescription included increasing age and prescription of antiplatelet therapy. Conversely, stroke risk factors such as prior stroke (ischaemic, haemorrhagic, and stroke of unknown origin), TIA, hypertension, HF, smoking history, VTE, diabetes, and PVD were associated with OAC prescription. Male sex, advancing frailty, harmful alcohol use, major bleeding, cancer, pulmonary disease, renal disease, prescription of non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and care home entry from 2011 were also associated with OAC prescription. All variables had a significance level <0.05.

Table 3.

Association between care home resident characteristics and the prescription of oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillationa

| Characteristics of residents with atrial fibrillation | Unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, per 1-year increase | 0.96 (0.96 to 0.97) | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.96) | <0.001 |

| Age category | |||

| 65–74 years | Reference | ||

| 75–84 years | 0.96 (0.83 to 1.12) | ||

| 85–94 years | 0.71 (0.61 to 0.82) | ||

| ≥95 years | 0.35 (0.29 to 0.42) | ||

| Sex, male | 1.26 (1.18 to 1.35) | 1.09 (1.01 to 1.18) | 0.024 |

| WIMD quintile | |||

| 1 (most deprived) | Reference | ||

| 2 | 1.01 (0.91 to 1.13) | ||

| 3 | 1.00 (0.90 to 1.11) | ||

| 4 | 1.00 (0.90 to 1.11) | ||

|

| |||

| Year of care home entry ≥2011 | 2.27 (2.12 to 2.43) | 1.91 (1.76 to 2.06) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Frailty | |||

| No frailty | Reference | Reference | |

| Mild | 4.45 (3.85 to 5.14) | 4.61 (3.95 to 5.38) | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 7.33 (6.36 to 8.44) | 6.69 (5.74 to 7.80) | <0.001 |

| Severe | 10.68 (9.23 to 12.36) | 8.42 (7.16 to 9.90) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Social history before care home entry | |||

| Smoking history | 1.82 (1.69 to 1.96) | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.26) | 0.001 |

| Harmful alcohol usec | 1.51 (1.34 to 1.70) | 1.00 (0.88 to 1.14) | 0.966 |

|

| |||

| Medical history before care home entry | |||

| Dementiad | 0.91 (0.81 to 1.03) | ||

| Pulmonary diseasee | 1.38 (1.26 to 1.50) | 0.94 (0.85 to 1.03) | 0.191 |

| Peptic ulcer | 1.01 (0.84 to 1.23) | ||

| Cancer | 1.22 (1.11 to 1.33) | 1.04 (0.94 to 1.15) | 0.401 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 1.81 (1.63 to 2.00) | 1.13 (1.02 to 1.27) | 0.025 |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 1.42 (1.14 to 1.76) | 1.18 (0.93 to 1.50) | 0.183 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 1.58 (1.44 to 1.73) | 1.51 (1.37 to 1.67) | <0.001 |

| Stroke of unknown origin | 1.42 (1.20 to 1.67) | 1.32 (1.10 to 1.58) | 0.002 |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 1.29 (1.12 to 1.49) | 1.22 (1.04 to 1.43) | 0.012 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.08 (0.96 to 1.22) | ||

| Heart failure | 1.63 (1.51 to 1.75) | 1.46 (1.35 to 1.58) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.54 (1.33 to 1.80) | 1.05 (0.88 to 1.24) | 0.603 |

| Renal disease | 1.41 (1.24 to 1.60) | 0.96 (0.84 to 1.11) | 0.582 |

| Liver disease | 0.84 (0.47 to 1.52) | ||

| Hypertension | 1.65 (1.54 to 1.76) | 1.05 (0.98 to 1.13) | 0.176 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.54 (1.34 to 1.78) | 1.09 (0.93 to 1.26) | 0.293 |

| Aortic plaque | 1.76 (0.42 to 7.35) | ||

| Major bleeding | 1.62 (1.48 to 1.76) | 1.35 (1.23 to 1.48) | <0.001 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 4.38 (3.48 to 5.51) | 4.06 (3.17 to 5.20) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Medication history within 6 months before care home entry | |||

| Prescription of antiplatelet(s) without NSAID(s) | 0.88 (0.83 to 0.95) | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.98) | 0.014 |

| Prescription of NSAID(s) without antiplatelet(s) | 2.05 (1.80 to 2.33) | 1.75 (1.51 to 2.02) | <0.001 |

Prescription within 6 months before care home entry used as a proxy for prescription at the point of care home entry.

Reported for adjusted odds ratio.

Including alcoholism and heavy drinker.

Including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, younger-onset dementia, and other or unspecified dementia.

Including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and other pulmonary. NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. WIMD = Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation.

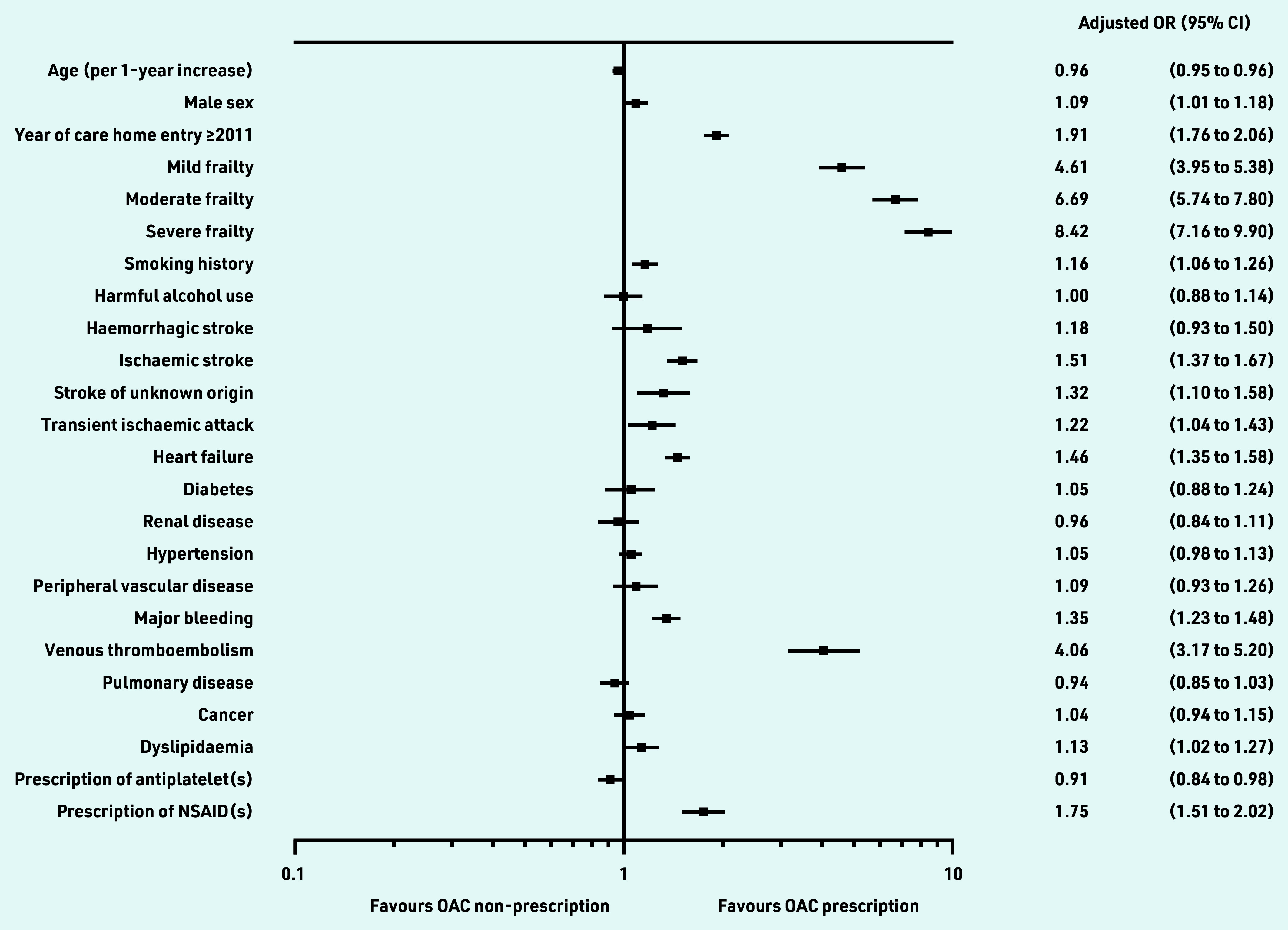

In the multivariate model (Table 3 and Figure 2), advancing age (aOR 0.96 per 1-year increase, 95% CI = 0.95 to 0.96, P<0.001) and prescription of antiplatelet therapy remained as factors significantly associated with OAC non-prescription (aOR 0.91, 95% CI = 0.84 to 0.98, P = 0.014). Prior VTE (aOR 4.06, 95% CI = 3.17 to 5.20, P<0.001), ischaemic stroke (aOR 1.51, 95% CI = 1.37 to 1.67, P<0.001) and HF (aOR 1.46, 95% CI = 1.35 to 1.58, P<0.001) were the stroke risk factors most strongly associated with OAC prescription. Dyslipidaemia, smoking history, stroke of unknown origin, and TIA were also other stroke risk factors independently associated with OAC prescription. There was no significant association found between hypertension and OAC prescription.

Figure 2.

Factors associated with prescription of oral anticoagulationa in new care home residents aged ≥65 years with atrial fibrillation, using a multivariable adjusted model. The reference for frailty categories is no frailty. Multivariate model adjusted for dyslipidaemia, smoking history, cancer diagnoses, year of care home entry ≥2011, and individual components of CHA2DS2VASc and HAS-BLED risk assessment scores. a Prescription within 6 months before care home entry used as a proxy for prescription at the point of care home entry.

NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. OAC = oral anticoagulant. OR = odds ratio.

Other independent predictors of OAC prescription included male sex (aOR 1.09, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.18, P = 0.024), advancing frailty (mild: aOR 4.61, 95% CI = 3.95 to 5.38, P<0.001; moderate: aOR 6.69, 95% CI = 5.74 to 7.80, P<0.001; severe: aOR 8.42, 95% CI = 7.16 to 9.90, P<0.001), major bleeding (aOR 1.35, 95% CI = 1.23 to 1.48, P<0.001), prescription of NSAIDs (aOR 1.75, 95% CI = 1.51 to 2.02, P<0.001) and care home entry from 2011 onwards (aOR 1.91, 95% CI = 1.76 to 2.06, P<0.001).

The variance inflation factor was <1.5 for all covariates (see Supplementary Table S6). When age was included as a categorical variable, the same covariates were identified as predictors of OAC prescription or non-prescription (see Supplementary Table S7). When people who had a major bleeding event and evidence of OAC prescription within 6 months before care home entry were excluded, the positive association between OAC prescription and major bleeding was attenuated (aOR 1.12, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.23, P = 0.028) (see Supplementary Figure S2).

DISCUSSION

Summary

This study found that between 2003 and 2018, less than half of new care home residents with AF aged ≥65 years were prescribed OACs. The proportion of new residents prescribed an OAC within 6 months before care home entry more than doubled from 2003 to 2018. Increasing age and prescription of antiplatelet therapy were independently associated with OAC non- prescription. In contrast, advancing frailty, prior VTE, and year of care home entry after 2011 were the strongest predictors independently associated with OAC prescription.

Strengths and limitations

To the authors’ knowledge, this is one of the largest population studies conducted exclusively in new care home residents that aims to elucidate the factors associated with OAC prescription for AF. Study limitations pertain to the observational design and use of routinely collected data. Data can only give insight into association rather than causation, and the direction of causality cannot be conferred. It is possible that some diagnoses were missed using Read and ICD-10 codes, or classified incorrectly. In the present study it is anticipated there may be a greater proportion of residents with dementia than actually reported, and the number of people with uncontrolled hypertension may have been overestimated using the study’s definition. Investigation of the temporal association between major bleeding and OAC prescription was limited because it was not possible to confirm whether OACs were prescribed before or after the major bleeding event, or what time elapsed between the two. It was not possible to explore temporal associations between NSAID prescription or harmful alcohol use and OAC prescription as these data were not available in SAIL.

Comparison with existing literature

When comparing the findings in the present study to other care home studies, some of the results are conflicting. One systematic review3 of observational studies in care homes found the majority of studies reported older age,35–40 falls/fall risk,39,40 and dementia/cognitive impairment36–39,41 as independent predictors of anticoagulant non-prescription, but a number of studies did not.37,40–42 Studies also reported previous stroke/TIA35,36,38,39,43 and VTE35,36,39 as independent predictors of anticoagulant prescription, but again, this was not found in all studies.42 Two studies reported no association between anticoagulant prescription and antiplatelet therapy in multivariate analysis,36,42 but one study reported antiplatelet therapy as an independent predictor of anticoagulant non-prescription.35 Inconsistencies in results likely relate to differences in study methods to establish residents’ medical and medication history. Another explanation is diversity across care home settings, where resident characteristics, clinical practice, and perception of OAC use will differ.

Over the past decade, guidance on stroke prevention management for AF has changed. NOACs became available in Europe in 2011, and are now recommended in preference to VKA therapy.7 Devoid of complex monitoring requirements, NOACs have improved accessibility to OAC therapy and this is reflected in the study results; people who entered a care home in the post-NOAC era (from 2011 onwards) were significantly more likely to be prescribed OAC therapy. The standpoint on concomitant prescription of antiplatelet and OAC therapy has remained unchanged, with guidelines advising against this to minimise the risk of bleeding.7,44 An exception to this is in the event of acute coronary syndrome or percutaneous coronary intervention where antiplatelet therapy is indicated alongside OACs for up to 12 months post-event.7,44 Caution should also be applied when prescribing NSAIDs alongside OAC therapy because of the increased risk of bleeding.7 Although the results of this study suggest an aversion to concomitant prescription of OAC and antiplatelet therapy, this does not appear to be the case for NSAID therapy. NSAIDs are usually prescribed for a short duration to manage acute pain arising from inflammatory conditions. Without being able to distinguish residents prescribed an acute course of NSAID from those regularly prescribed NSAIDs alongside their OAC therapy, the findings must be interpreted cautiously. Concomitant prescription is not an absolute contraindication, so it is possible the results reflect an acceptance to prescribe short courses of NSAIDs alongside OAC therapy in some individuals.

The study finding that each 1-year age increase is associated with a 4% reduction in OAC prescription verifies ongoing concerns about underprescribing in older people because of misperceptions of the risk of adverse effects.45 Ageing is a prominent non-modifiable risk factor for stroke,6,7 and any reduction in OAC prescription as a result of older age will have clinical consequences. Recently, a large registry study verified OAC safety in people aged >90 years with a history of chronic kidney disease and intracranial haemorrhage.46

There is considerable overlap between bleeding and stroke risk factors, and people with AF and a history of bleeding or intracranial haemorrhage remain at a high ischaemic stroke risk.7 This may explain the positive association found between major bleeding and OAC prescription. Although this study found an expected rise in OAC prescribing for increasingly frail people, further work is needed to investigate the interaction with deprivation and other socioeconomic and demographic factors to assess potential inequalities in prescribing across these groups. Nevertheless, this finding provides an interesting insight on prescribing patterns before definitive guidance on OAC prescription in people with frailty was detailed by the ESC in 2020, which states that frailty should not be a barrier to OAC prescription.7 Another electronic health record study of 58 204 people with AF aged ≥65 years in England also reported a positive association between advancing electronic Frailty Index frailty category and OAC prescription (mild: aOR 1.84, 95% CI = 1.72 to 1.96; moderate: aOR 2.34, 95% CI = 1.18 to 2.50; and severe: aOR 2.51, 95% CI = 2.33 to 2.71).47 One explanation may be that frailer adults are more frequently reviewed by clinicians, so there are less likely to be omissions in OAC prescribing.

Implications for research and practice

This study provides an important insight into the factors that influence OAC prescribing for new care home residents with AF, a high-risk group that is underrepresented in research. The proportion of new residents prescribed OAC therapy has increased with the introduction of NOACs, but OAC prescription rates are still suboptimal. There is a need for future research to elucidate other barriers to OAC prescription, and further explore temporal associations between OAC prescription and falls, alcohol use, and prescription of antiplatelet/NSAID therapy.

Acknowledgments

This study makes use of anonymised data held in the SAIL Databank. The authors would like to acknowledge all the data providers who make anonymised data available for research. All research conducted has been completed under the permission and approval of the SAIL IGRP (project number: 0912).

Funding

No specific funding was received for this work. This work was supported by Health Data Research UK (reference number: HDR-9006), which receives its funding from the UK Medical Research Council, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Department of Health and Social Care (England), Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Health and Social Care Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), British Heart Foundation (BHF), and the Wellcome Trust; and Administrative Data Research UK, which is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number: ES/S007393/1). Sarah E Rodgers is part-funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration North West Coast (ARC NWC). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Ethical approval

The study received Information Governance Review Panel (IGRP) approval (project number: 0912) before data were made available within the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) Databank.

Data

The data used in this study are available in the SAIL Databank at Swansea University, Swansea, UK. Analytic code could be provided for future work after agreed acknowledgement in any future publications. All proposals to use SAIL data are subject to review by an IGRP. Before any data can be accessed, approval must be given by the IGRP. The IGRP ensures appropriate use of SAIL data. When access has been approved, it is gained through a privacy-protecting safe haven and remote access system referred to as the SAIL Gateway. An application process should be followed by anyone who would like to access data via SAIL at: https://saildatabank.com/data/apply-to-work-with-the-data.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

Stephanie L Harrison has received an investigator-initiated grant from Bristol- Myers Squibb (BMS); Gregory YH Lip has been a consultant and speaker for BMS/Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi-Sankyo, no fees are received personally; Deirdre A Lane has received investigator-initiated educational grants from BMS, has been a speaker for Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and BMS/Pfizer, and has consulted for BMS and Boehringer Ingelheim; Daniel Harris reports grants and speaker fees from BMS/Pfizer, outside the submitted work; and Peter E Penson owns four shares in AstraZeneca PLC, and has received honoraria and/or travel reimbursement for events sponsored by AKCEA, Amgen, AMRYT, Link Medical, Napp, and Sanofi. Leona A Ritchie, Ashley Akbari, Fatemeh Torabi, Joe Hollinghurst, Asangaedem Akpan, Oluwakayode B Oke, Sarah E Rodgers, and Julian P Halcox have declared no competing interests

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Karamichalakis N, Letsas KP, Vlachos K, et al. Managing atrial fibrillation in the very elderly patient: challenges and solutions. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2015;11:555–562. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S83664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: update from the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(25):2982–3021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritchie LA, Oke OB, Harrison SL, et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation and outcomes in older long-term care residents: a systematic review. Age and Ageing. 2021;50(3):744–757. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaskes MJ, Hanner N, Karmilowicz P, Curtis AB. Abstract 14963: screening for atrial fibrillation in high-risk nursing home residents. Circulation. 2018;138(Suppl 1):A14963. doi: 10.1016/j.hroo.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Caoimh R, Igras E, Ramesh A, et al. Assessing the appropriateness of oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in advanced frailty: use of stroke and bleeding risk-prediction models. J Frailty Aging. 2017;6(1):46–52. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2016.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22(8):983–988. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.8.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eu Heart J. 2021;42(5):373–498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oo W, Kozikowski A, Stein J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy practices in older adults residing in the long-term care setting. South Med J. 2015;108(7):432–436. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damanti S, Braham S, Pasina L. Anticoagulation in frail older people. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2019;16(11):844–846. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2019.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sluggett JK, Harrison SL, Ritchie LA, et al. High-risk medication use in older residents of long-term care facilities: prevalence, harms, and strategies to mitigate risks and enhance use. Sr Care Pharm. 2020;35(10):419–433. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2020.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics – 2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(7):948–954. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin HJ, Wolf PA, Kelly-Hayes M, et al. Stroke severity in atrial fibrillation. The Framingham Study. Stroke. 1996;27(1):1760–1764. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.10.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reiffel JA. Atrial fibrillation and stroke: epidemiology. Am J Med. 2014;127(4):e15–e16. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sardar P, Chatterjee S, Chaudhari S, Lip GY. New oral anticoagulants in elderly adults: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(5):857–864. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):981–992. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauersachs R, Berkowitz SD, Brenner B, et al. Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2499–2510. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al. Extended use of dabigatran, warfarin, or placebo in venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(8):709–718. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rash A, Downes T, Portner R, et al. A randomised controlled trial of warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in octogenarians with atrial fibrillation (WASPO) Age Ageing. 2007;36(2):151–156. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mant J, Hobbs FDR, Fletcher K, et al. Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study, BAFTA): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9586):493–503. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyons RA, Jones KH, John G, et al. The SAIL databank: linking multiple health and social care datasets. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009;9:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ford DV, Jones KH, Verplancke JP, et al. The SAIL Databank: building a national architecture for e-health research and evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:157. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones KH, Ford DV, Jones C, et al. A case study of the Secure Anonymous Information Linkage (SAIL) Gateway: a privacy-protecting remote access system for health-related research and evaluation. J Biomed Inform. 2014;50(100):196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Digital Health and Care Wales, Secure Anonymised Information Linkage Welsh Demographic Service Dataset (WDSD) 2019. https://web.www.healthdatagateway.org/dataset/8a8a5e90-b0c6-4839-bcd2-c69e6e8dca6d (accessed 8 Dec 2022).

- 27.Welsh General Practices that have signed up to SAIL, Secure Anonymised Information Linkagae. Welsh Longitudinal General Practice Dataset (WLGP) — Welsh Primary Care. 2021. https://web.www.healthdatagateway.org/dataset/33fc3ffd-aa4c-4a16-a32f-0c900aaea3d2 (accessed 8 Dec 2022).

- 28.Digital Health and Care Wales, Secure Anonymised Information Linkage Patient Episode Dataset for Wales (PEDW) 2019. https://web.www.healthdatagateway.org/dataset/4c33a5d2-164c-41d7-9797-dc2b008cc852 (accessed 8 Dec 2022).

- 29.Hollinghurst J, Akbari A, Fry R, et al. Study protocol for investigating the impact of community home modification services on hospital utilisation for fall injuries: a controlled longitudinal study using data linkage. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e026290. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodgers SE, Lyons RA, Dsilva R, et al. Residential Anonymous Linking Fields (RALFs): a novel information infrastructure to study the interaction between the environment and individuals’ health. J Public Health (Oxf) 2009;31(4):582–588. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hollinghurst J, Fry R, Akbari A, Rodgers S. Using residential anonymous linking fields to identify vulnerable populations in administrative data. Int J Popul Data Sci. 2018;3(4):302. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodgers SE, Demmler JC, Dsilva R, Lyons RA. Protecting health data privacy while using residence-based environment and demographic data. Health Place. 2012;18(2):209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(1):125–137. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghaswalla PK, Harpe SE, Slattum PW. Warfarin use in nursing home residents: results from the 2004 national nursing home survey. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10(1):25–36.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gill CS. Oral anticoagulation medication usage in older adults with atrial fibrillation residing in long-term care facilities. 2018 https://www.proquest.com/openview/12ff4973b146d356f22eee19d380347a/1 (accessed 8 Dec 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dutcher SK. Pharmacotherapeutic management and care transitions among nursing home residents with atrial fibrillation. 2014 https://archive.hshsl.umaryland.edu/bitstream/handle/10713/4104/Dutcher_umaryland_0373D_10531.pdf (accessed 8 Dec 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gurwitz JH, Monette J, Rochon PA, et al. Atrial fibrillation and stroke prevention with warfarin in the long-term care setting. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(9):978–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frain B, Castelino R, Bereznicki LR. The utilization of antithrombotic therapy in older patients in aged care facilities with atrial fibrillation. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2018;24(3):519–524. doi: 10.1177/1076029616686421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bahri O, Roca F, Lechani T, et al. Underuse of oral anticoagulation for individuals with atrial fibrillation in a nursing home setting in France: comparisons of resident characteristics and physician attitude. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(1):71–76. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel AA, Reardon G, Nelson WW, et al. Persistence of warfarin therapy for residents in long-term care who have atrial fibrillation. Clin Ther. 2013;35(11):1794–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lau E, Bungard TJ, Tsuyuki RT. Stroke prophylaxis in institutionalized elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(3):428–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Latif AKA, Peng X, Messinger-Rapport BJ. Predictors of anticoagulation prescription in nursing home residents with atrial fibrillation. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6(2):128–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Atrial fibrillation: diagnosis and management NG196. 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng196 (accessed 30 Nov 2022). [PubMed]

- 45.Zathar Z, Karunatilleke A, Fawzy AM, Lip GYH. Atrial fibrillation in older people: concepts and controversies. Front Med (Lausanne) 2019;6:175. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chao TF, Chiang CE, Chan YH, et al. Oral anticoagulants in extremely-high-risk, very elderly (>90 years) patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2021;18(6):871–877. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2021.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilkinson C, Clegg A, Todd O, et al. Atrial fibrillation and oral anticoagulation in older people with frailty: a nationwide primary care electronic health records cohort study. Age Ageing. 2021;50(3):772–779. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]