Abstract

Background

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the loss of upper and lower motor neurons, leading to progressive weakness of voluntary muscles, with death following from neuromuscular respiratory failure, typically within 3 to 5 years. There is a strong genetic contribution to ALS risk. In 10% or more, a family history of ALS or frontotemporal dementia is obtained, and the Mendelian genes responsible for ALS in such families have now been identified in about 50% of cases. Only about 14% of apparently sporadic ALS is explained by known genetic variation, suggesting that other forms of genetic variation are important. Telomeres maintain DNA integrity during cellular replication, differ between sexes, and shorten naturally with age. Sex and age are risk factors for ALS and we therefore investigated telomere length in ALS.

Methods

Samples were from Project MinE, an international ALS whole genome sequencing consortium that includes phenotype data. For validation we used donated brain samples from motor cortex from people with ALS and controls. Ancestry and relatedness were evaluated by principal components analysis and relationship matrices of DNA microarray data. Whole genome sequence data were from Illumina HiSeq platforms and aligned using the Isaac pipeline. TelSeq was used to quantify telomere length using whole genome sequence data. We tested the association of telomere length with ALS and ALS survival using Cox regression.

Results

There were 6,580 whole genome sequences, reducing to 6,195 samples (4,315 from people with ALS and 1,880 controls) after quality control, and 159 brain samples (106 ALS, 53 controls). Accounting for age and sex, there was a 20% (95% CI 14%, 25%) increase of telomere length in people with ALS compared to controls (p = 1.1 × 10−12), validated in the brain samples (p = 0.03). Those with shorter telomeres had a 10% increase in median survival (p = 5.0×10−7). Although there was no difference in telomere length between sporadic ALS and familial ALS (p=0.64), telomere length in 334 people with ALS due to expanded C9orf72 repeats was shorter than in those without expanded C9orf72 repeats (p = 5.0×10−4).

Discussion

Although telomeres shorten with age, longer telomeres are a risk factor for ALS and worsen prognosis. Longer telomeres are associated with ALS.

Keywords: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), telomere–genetics, whole genome sequence (WGS), genomics, bigdata, MND–motor neuron disorders

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease affecting motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord resulting in progressive paralysis and death, within three to five years, typically due to respiratory failure (Brown and Al-Chalabi, 2017; Hardiman et al., 2017). The first symptoms of weakness can occur in the bulbar innervated muscles, manifesting as difficulty with speech or swallowing, or in the spinal innervated muscles, manifesting as limb weakness or breathing difficulty. About 5% may have a frank frontotemporal dementia, and frontotemporal impairment is seen in up to 80% of people by the time King’s Stage 4 disease is reached (Roche et al., 2012; Crockford et al., 2018).

The last decade has seen substantial advances in our understanding of the genomic basis of ALS (van Rheenen et al., 2021; Hop et al., 2022) but a significant proportion of the genetic contribution to risk remains unexplained. This hidden heritability may be harbored in other types of genomic variation as well as in rare variants that may be unique to an affected individual or family (Al-Chalabi et al., 2010; McLaughlin et al., 2015).

Telomeres are repeated TTAGGG nucleotide sequences located at the ends of chromosomes and exist to maintain chromosomal structural integrity during cellular replication. They shorten naturally with age and differ in average length between the sexes (Muzumdar and Atzmon, 2012; Kong et al., 2013; Gardner et al., 2014); age and sex are also risk factors for ALS (McCombe and Henderson, 2010; Al-Chalabi and Hardiman, 2013; Westeneng et al., 2018). Telomere length is a marker for aging, chromosomal instability and DNA damage, and might therefore be relevant as a risk factor for ALS (Murnane, 2006; Conomos et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2013; Marzec et al., 2015).

Previously, in a pilot study in a UK cohort, we showed that longer telomeres might be associated with ALS when compared to age and sex-matched controls (Al Khleifat et al., 2019). We therefore sought to explore this finding in detail, using whole-genome sequence data from the Project MinE consortium (van Rheenen et al., 2018), a large international ALS genomics collaboration.

Materials and methods

Data sources and data extraction

Blood samples

Samples were from the international Project MinE whole genome sequencing consortium and derived from seven countries: the USA, Ireland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain, Turkey, and the United Kingdom (van Rheenen et al., 2018).

DNA was isolated from venous blood using standard methods. The DNA concentrations were set at 100 ng/ul as measured by a fluorimeter with the PicoGreen® dsDNA quantitation assay. DNA integrity was assessed using gel electrophoresis.

Post-mortem samples

Post-mortem motor cortex was from the MRC London Neurodegenerative Diseases Brain Bank based at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London. Tissue was flash frozen stored at −80°C. 100 mg tissue blocks were excised. DNA was isolated from the same tissue block and sequenced. The study cohort consisted of 64 people with apparently sporadic ALS and 53 controls with no known neurological disease (controls below Hyperphosphorylated tau (HP-τ) in human brain tissue and BNE\Braak stage 2).

The 100 mg tissue blocks were divided to allow DNA purification. For each sample, a 25 mg tissue block for DNA was homogenized using a Qiagen PowerLyzer 24 Homogenizer. DNA was purified from the homogenate using the standard protocol from Qiagen’s DNeasy Blood and Tissue Mini Kit. DNA was quantified using PicoGreen (Quant-iT™ PicoGreen® dsDNA Reagent, ThermoFisher Scientific) and measured using a Spectromax Gemini XPS (Molecular Devices).

Library preparation and DNA sequencing

Library preparation was performed using the Illumina DNA Sample Preparation HT Kit alongside the Illumina SeqLab DNA PCR-Free Library Prep Guide. Libraries were then quantified using qPCR and evaluated using gel electrophoresis. All samples were sequenced using Illumina’s FastTrack services (San Diego, CA, USA). Some blood-derived DNA samples were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. Sequencing was 100 bp paired-end performed using PCR-free library preparations and targeted ∼40x coverage across each sample. Remaining blood-derived and all brain-derived DNA libraries were clustered onto flow cells using the Illumina cBot System, as per cBot System Guide using Illumina HiSeq X HD Paired End Cluster Kit reagents and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeqX with 151 bp paired-end runs using independent flow cell lanes and with a target minimum of 30x average coverage per sample. Binary sequence alignment/map formats (BAM) were generated for each individual. All the genomes were aligned with Isaac (Illumina) to hg19. The details of the Isaac alignment and variant calling pipelines are discussed in Project MinE design (van Rheenen et al., 2018) and the Isaac protocol (Raczy et al., 2013).

Determination of telomere length

TelSeq (Ding et al., 2014) was used to quantify telomere length using whole genome sequence data. Telomere lengths were estimated from reads, defined as repeats of more than seven TTAGGG motifs.

Statistical analysis

The effect of telomere length on ALS risk was tested using a multivariable linear regression model. To account for different sequencing platforms and population stratification, principal components of ancestry, center and technology platform were included as covariates. To assess the model, Pearson’s chi-squared test was used. Because telomere length correlates with age, we performed an additional test to examine the possibility that survival bias could affect the results. To do this, we also performed the analysis restricted to the subgroup of people with ALS onset below the median cohort age (62 years). As brain is composed of neurons which do not divide, as well as glia which do, we expected that the average telomere length in brain would be longer than in blood. Furthermore, nervous tissue is the target of the disease process rather than blood. We therefore additionally tested the effect of age on telomere length in brain tissue.

To determine if telomeres are lengthened in ALS, or simply shorten less rapidly than in controls, we analysed the effect of age on telomere length in each group using multivariable linear regression.

To assess the effect of covariates on telomere length affecting survival, we used Cox regression, controlling for age, sex and site of disease onset (bulbar or spinal), population stratification, principal components, center and sequencing platforms.

Repeat primed PCR and Expansion Hunter-v2.5.1 (Dolzhenko et al., 2017) were used to assay the hexanucleotide repeat expansion in the C9orf72 gene since this is a known risk factor for ALS and associates with survival.

Statistical tests were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA), and RStudio, R Foundation for Statistical Computing 3.4.1 (RStudio, Vienna, Austria).

Quality control

Quality control was performed separately on the genotyped data of each population as reported previously (van Rheenen et al., 2016; Supplementary Appendix 1).

Ethical approval

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in this project according to the ethical approval at each participating Project MinE site as previously described (van Rheenen et al., 2018).

Results

There were 6,580 whole genome sequences (4,515 from people with ALS and 2,065 from controls), reducing to 6,195 [4,315 (95.6%) from people with ALS and 1,880 (91%) from controls] after quality control, with minimum ∼25x coverage across each sample. The set was enriched for apparently sporadic ALS [4,236 compared with 79 with familial ALS (FALS)]. The male-female ratio was 2:1. Overall, 22 had ALS-frontotemporal dementia (ALS-FTD). Phenotypically, 37 had pure progressive bulbar palsy (PBP) and 68 and progressive muscular atrophy. There were 1,908 sequenced using the HiSeq2000 platform and 4,287 sequenced using the HiSeqX Illumina platform (Table 1). There were 344 people carrying an expanded C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat, 334 with ALS and 10 without symptoms.

TABLE 1.

Detailed demographic features of the study population.

| Cohort | Sample | Case | Control | Female | Male |

| Belgium | 548 | 368 | 180 | 209 | 339 |

| Ireland | 403 | 267 | 136 | 161 | 242 |

| Netherlands | 2894 | 1859 | 1035 | 1182 | 1712 |

| Spain | 338 | 233 | 105 | 145 | 193 |

| Turkey | 223 | 148 | 75 | 87 | 136 |

| United Kingdom | 1402 | 1124 | 278 | 603 | 799 |

| United States | 387 | 316 | 71 | 153 | 234 |

| Total | 6195 | 4315 | 1880 | 2540 | 3655 |

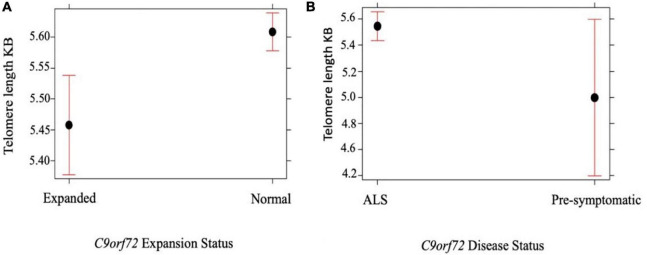

The mean telomere length in people with ALS was 5.5 kb, and in controls, 5.38 kb (Figure 1). Multivariable linear regression accounting for sex and age as covariates showed a mean 20% (95% CI 14, 25%) longer telomere length in people with ALS compared to controls (p = 1.1 × 10–12). Covariate analysis showed that regardless of disease status, females (p = 2.42 × 10–5) and younger people (p = 1.2 × 10–16) had on average longer telomeres (Table 2), confirming the results of earlier studies that telomere length reduces with age and females have on average longer telomeres.

FIGURE 1.

Mean telomere length by age (A), sex (B), and disease status (C). Purple bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

TABLE 2.

Telomere length comparison between people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and healthy controls using a generalized linear model.

| Estimate | SD of estimate | P-value | |

| Age (per year) | −2% | 0.02 | 1.1 × 10–16 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | −8% | 0.03 | 2.42 × 10–5 |

| Case-control status (controls vs. cases) | −29% | 0.02 | 1.1 × 10–12 |

To assess if the observed longer telomere length in apparently sporadic ALS is also seen in familial ALS, we assessed telomere length in 79 people, not included in the main analysis, with a family history of ALS in a first degree relative (FALS). Multivariable linear regression after correcting for age and sex again showed a longer average telomere length in people with FALS than in controls (p = 2.0 × 10–16).

Examining the effect of age on telomere length in ALS and controls separately, showed that the rate of shortening by age is slower in ALS than in controls, suggesting it is not an active lengthening of telomeres in ALS (0.022% per year, p < 0.0001 vs. 0.012% per year, p < 0.0001) and also arguing against the possibility that telomeres are longer to start with in people who will later develop ALS. The rate of shortening was different in males and females, with females showing a faster rate of shortening than males (Supplementary Figure 1).

In an analysis exploring survival bias as an explanation for our results, we restricted testing to those younger than the median age (62 years). Multivariable linear regression accounting for sex and age still showed that telomeres were longer in people with ALS compared to controls (p = 8.12 × 10–12) with mean telomere length in people with ALS, 5.8 kb, and in controls, 5.5 kb. To ensure that telomere length analysis was not biased by population effects, we excluded the UK, a population we used previously for discovery analysis, and using a subset of samples the association was still observed (p = 6.6 × 10–9).

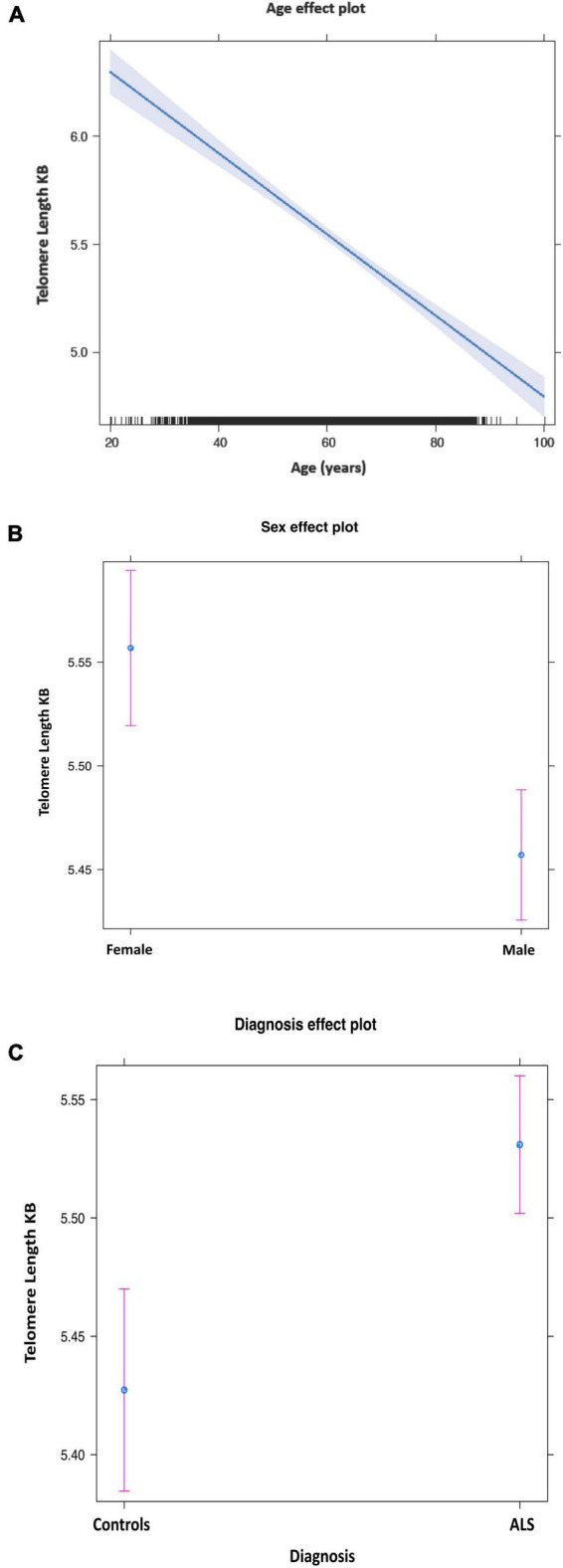

We compared telomere length in 334 people with ALS with C9orf72 repeat expansion against people with ALS with confirmed non-expanded C9orf72 status. Multivariable linear regression showed that the telomere was shorter in expansion carriers (p = 5.0 × 10–4) (Figure 2A and Table 3). Although ALS C9orf72 expansion carriers had a shorter telomere length than non-expansion carriers, telomere length was still longer in those carrying a C9orf72 repeat expansion than controls (p = 0.001) (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

(A) Telomere length comparison between 334 people with ALS carrying an expanded C9orf72 repeat against people with ALS not carrying an expansion. Multivariable linear regression shows that the telomere is shorter in those carrying a C9orf72 expansion compared with age and sex matched disease controls not carrying an expansion (p = 5.0 × 10– 4). (B) Telomere length comparison between 334 people with ALS with C9orf72 repeat expansion against 10 healthy individuals with confirmed expanded C9orf72 status. Multivariable linear regression shows that the telomere is longer in people with ALS with C9orf72 repeat expansion (p = 0.05). Telomere length reported in kilobases (kb). Red bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

TABLE 3.

Telomere length comparison between 552 people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) with a C9orf72 repeat expansion and 907 people with ALS with normal C9orf72 repeat length using a multivariable linear regression.

| Estimate | SD of estimate | P-value | |

| Age (per year) | −2% | 0.02 | 1.1 × 10–16 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | −15% | 0.03 | 2.42 × 10–5 |

| C9orf72 (expanded) | −27% | 0.02 | 5.0 × 10–4 |

We therefore assessed the relationship between the estimated number of telomere repeats and estimated number of C9orf72 repeats using ExpansionHunter in 1,589 samples from the UK. Multivariable linear regression showed that the number of telomere repeats is associated negatively with C9orf72 repeat expansion size (p = 0.003) supporting the previous results.

To assess if the relationship between C9orf72 repeat expansion and telomere repeat size was specific to C9orf72-mediated ALS, we ran ExpansionHunter on three ALS genes which also contain disease-associated repeat expansions: ATXN1, ATXN2, and NIPA1. There was no difference in telomere length observed between expansion carriers and non-expansion carriers for any of these genes.

Cox regression analysis showed that people with ALS with telomere length less than 5.3 Kb had a 10% increase in median survival compared with those with longer telomeres (p = 5.0 × 10–7) after correcting for age, sex, site of onset, C9orf72 status and principal components of ancestry.

To validate our findings in a different tissue we used 159 post-mortem brain samples, 106 from people with apparently sporadic ALS and 53 controls. The male-female ratio was 2:1. The mean telomere length in people with ALS was 6.8 kb, and in controls, 6.56 Kb, not taking into account gender or age. Multivariable linear regression accounting for these covariates showed that telomere length in people with ALS was longer by mean 29% (95% CI 30, 55%) compared with controls (p = 0.03).

Discussion

Using a large disease-specific whole genome sequencing dataset, we have shown that longer telomeres are associated with ALS, confirming initial findings from a pilot study (Al Khleifat et al., 2019). We were additionally able to show that our findings are likely a result of less rapid shortening of telomeres being associated with ALS, rather than active telomere lengthening in ALS. In keeping with expectations, we also found that mean telomere length was on average longer in females, and in all samples, shortened with increasing age. The association of longer telomeres with apparently sporadic ALS was also seen in FALS, supporting the notion that familial and sporadic ALS are not mutually exclusive categories but rather a spectrum (Al-Chalabi and Hardiman, 2013; Al-Chalabi et al., 2014; Chiò et al., 2018; Mehta et al., 2018). Furthermore, telomere length was inversely correlated with C9orf72 repeat expansion size.

Telomere elongation phenomena are well-documented but far less well-understood than telomere shortening phenomena (Bryan et al., 1995; Cesare and Reddel, 2010; Arora and Azzalin, 2015; Haycock et al., 2017). While telomere shortening is typically seen in cancers, telomere elongation can occur in cancers of the nervous system, and for example, is seen in 25% of primary brain tumors, in glioblastoma multiforme and in 10% of neuroblastomas (Bryan et al., 1997; Hakin-Smith et al., 2003; Henson et al., 2005; Durant, 2012; Boutou et al., 2013). In general, cancers in which cells have long telomeres are resistant to therapy and carry a poor prognosis (Haycock et al., 2017). Telomere elongation has also been associated with schizophrenia (Nieratschker et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2018), a disorder that genetically overlaps with ALS (McLaughlin et al., 2017). Additionally, longer telomeres are also reported in Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia blood and brain (Asghar et al., 2022).

We found that pathologically expanded C9orf72 repeats are negatively associated with telomere repeat length, so that people with expanded C9orf72 repeats had shorter telomeres on average. C9orf72 gene repeat expansion is the most frequent genetic cause of ALS and of the related condition, frontotemporal dementia (Shatunov et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2013; Hardiman et al., 2017; Iacoangeli et al., 2019). A possible explanation for the negative association is in the liability threshold model of disease. Those people who already have a high liability to ALS do not need the additional liability of longer telomeres and so on average would appear to have shorter telomeres. Alternatively, those in the higher risk group (non-repeat expansion carriers) need a greater contribution from other sources of disease liability and so have longer telomere repeats. Against this explanation is the observation that other gene variants that predispose to ALS risk such as intermediate ATXN2 repeat expansions, do not show any association with telomere length, and neither do people with familial ALS. The explanation might therefore lie in the C9orf72 repeat expansion itself. Both telomeres and large C9orf72 repeats have a tendency to fold into structures called G quadruplexes (Fratta et al., 2012; Grigg et al., 2014). G quadruplex structures have important roles in DNA replication, recombination and telomere maintenance (Millevoi et al., 2012; Bryan, 2019). Although there have been several studies of the G quadruplexes formed by C9orf72 repeat expansion, the relationship between C9orf72 repeats and other G quadruplexes such as telomeres is not documented at population level and has not been well-characterized in vivo (Zhang et al., 2019).

Some genetic variations that contribute to ALS risk also worsen prognosis. This is seen in carriers of the C9orf72 repeat expansion mutation, those carrying the UNC13A homozygous risk genotype, and for some variants of the SOD1 gene for example. In keeping with that pattern, we have found that longer telomere length is associated with ALS risk as well as with worse prognosis, with those with the shortest telomeres having a 10% increase in survival.

The genetic landscape of ALS is one of some monogenic causes, several gene variations that substantially but not dramatically increase risk, and a polygenic component. For those with a monogenic basis of their disease, the variable and age-dependent penetrance seen is likely because of the contribution of other factors to risk (Al-Chalabi and Hardiman, 2013; Al-Chalabi et al., 2014; Chiò et al., 2018; Garton et al., 2021). Based on these findings, telomere length could be such a factor.

The main limitation of this study is that we did not directly measure telomere length using Southern blotting, but estimated it using whole genome sequence data. The method we have used, TelSeq, was recently used to estimate telomere length in 75,000 whole genome sequences. Comparing the performance of TelSeq with other bioinformatics tools such as Computel, the estimates of telomere length were highly correlated between the bioinformatics methods and with Southern blot results, with the advantage that TelSeq had a faster processing time (Taub et al., 2019), although it is not possible to draw conclusions about the exact length of a telomere. Other studies have also shown a good correlation between TelSeq telomere length estimates, Southern blotting and Q-PCR (Ding et al., 2014; Cook et al., 2016). With this in mind, different sequencing technologies might generate different telomere length estimates because of differences in library preparation and platform (Ma, 1995; Aviv et al., 2011). To overcome this potential weakness, we have used the same industry-leading sequencing platform for all samples, as well as designing the study to minimize batch effects by having cases and controls sharing the same sequencing plate. Our study has the advantage of a large sample size of more than 4,500 cases, far larger than for previous reports.

We have shown that despite being an age-related, male-predominant condition, ALS is associated with longer telomere lengths in blood-derived and in brain-derived DNA.

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are deposited in the Project MinE consortium public repository (http://databrowser.projectmine.com).

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Board at each respective recruiting site within the Project MinE consortium as previously described (van Rheenen et al., 2018).

Author contributions

AA-C and AAK conceived and planned the study, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, did the statistical analysis, and prepared the figures and tables. AAK and AI created the bioinformatics pipeline for analysis. JvV ran ExpansionHunter on Project MinE data. MM and RZ prepared phenotypic data. AA-C, JHV, OH, MP, JM, PS, JL, CS, NB, OH, WR, PVD, and LB helped in sample collection and provided whole genome sequence data and analysis and intellectual input for data interpretation on behalf of the Project MinE Consortium. JHV, OH, and MM provided intellectual input for data interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Samples used in this research were in part obtained from the UK National DNA Bank for MND Research, funded by the MND Association and the Wellcome Trust. We thank people with MND and their families for their participation in this project. We acknowledge sample management undertaken by Biobanking Solutions funded by the Medical Research Council at the Centre for Integrated Genomic Medical Research, University of Manchester. The authors acknowledge use of the research computing facility at King’s College London, Rosalind (https://rosalind.kcl.ac.uk), which is delivered in partnership with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centres at South London and Maudsley and Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trusts, and part-funded by capital equipment grants from the Maudsley Charity (award 980) and Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Charity (TR130505). We also acknowledge Health Data Research UK, which is funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Department of Health and Social Care (United Kingdom), Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Health and Social Care Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), British Heart Foundation and Wellcome Trust.

Funding

AAK was funded by ALS Association Milton Safenowitz Research Fellowship (grant number 22-PDF-609. doi: 10.52546/pc.gr.150909), The Motor Neurone Disease Association (MNDA) Fellowship (Al Khleifat/Oct21/975-799), The Darby Rimmer Foundation, and The NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre. This project was also funded by the MND Association and the Wellcome Trust. This is an EU Joint Programme-Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND) project. The project is supported through the following funding organizations under the aegis of JPND–www.jpnd.eu [United Kingdom, Medical Research Council (MR/L501529/1 and MR/R024804/1) and Economic and Social Research Council (ES/L008238/1)]. AA-C was a NIHR Senior Investigator. CS and AA-C received salary support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Dementia Biomedical Research Unit at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The work leading up to this publication was funded by the European Community’s Health Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013; grant agreement number 259867) and Horizon 2020 Program (H2020-PHC-2014-two-stage; grant agreement number 633413). This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (grant agreement no. 772376–EScORIAL. The collaboration project was co-funded by the PPP Allowance made available by Health∼Holland, Top Sector Life Sciences and Health, to stimulate public-private partnerships. Project MinE Belgium was supported by a grant from IWT, the Belgian ALS Liga and a grant from Opening the Future Fund (KU Leuven). PVD holds a senior clinical investigatorship of FWO-Vlaanderen and was supported by E. von Behring Chair for Neuromuscular and Neurodegenerative Disorders, the ALS Liga België and the KU Leuven funds “Een Hart voor ALS,” “Laeversfonds voor ALS Onderzoek,” and the “Valéry Perrier Race against ALS Fund”. RM was supported by Science Foundation Ireland (17/CDA/4737). MinE USA was funded by the US ALS Association.

Conflict of interest

AA-C was a consultant for Mitsubishi-Tanabe Pharma, GSK, and Chronos Therapeutics, and chief investigator for clinical trials for Cytokinetics and OrionPharma. JvV reports to have sponsored research agreements with Biogen. VS was a consultant for Novartis and Biogen. LB reports grants from Netherlands ALS Foundation, grants from Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (Vici Scheme), grants from The European Community’s Health Seventh Framework Programme [grant agreement no. 259867 (EuroMOTOR)], grants from Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development) the STRENGTH project, funded through the EU Joint Programme—Neurodegenerative Disease Research, JPND), during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Calico, personal fees from Cytokinetics, grants and personal fees from Takeda, non-financial support from Orion, non-financial support from Orphazyme, outside the submitted work. AA-C also serves on scientific advisory boards for Mitsubishi Tanabe, Roche, Denali Pharma, Cytokinetics, Lilly, and Amylyx research. CS reports grants from Avexis, grants from Eli Lilly, grants from Chronos Therapeutics, grants from Vertex Pharmaceuticals, during the conduct of the study; grants from QurAlis, grants from Chronos Therapeutics, grants from Biogen, outside the submitted work. JL was a member of the scientific advisory board for Cerevel Therapeutics, a consultant for ACI Clinical LLC sponsored by Biogen, Inc. or Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. JL was also a consultant for Perkins Coie LLP and may provide expert testimony and also supported by funding from NIH/NINDS (R01NS073873 and R56NS073873). The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fncel.2022.1050596/full#supplementary-material

References

- Al Khleifat A., Iacoangeli A., Shatunov A., Fang T., Sproviero W., Jones A. R., et al. (2019). Telomere length is greater in ALS than in controls: A whole genome sequencing study. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 20 229–234. 10.1080/21678421.2019.1586951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Chalabi A., Hardiman O. (2013). The epidemiology of ALS: A conspiracy of genes, environment and time. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9 617–628. 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Chalabi A., Calvo A., Chio A., Colville S., Ellis C. M., Hardiman O., et al. (2014). Analysis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis as a multistep process: A population-based modelling study. Lancet Neurol. 13 1108–1113. 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70219-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Chalabi A., Fang F., Hanby M. F., Leigh P. N., Shaw C. E., Ye W., et al. (2010). An estimate of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis heritability using twin data. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 81 1324–1326. 10.1136/jnnp.2010.207464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora R., Azzalin C. M. (2015). Telomere elongation chooses TERRA ALTernatives. RNA Biol. 12 938–941. 10.1080/15476286.2015.1065374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asghar M., Odeh A., Fattahi A. J., Fattahi A. J., Henriksson A. E., Miglar A., et al. (2022). Mitochondrial biogenesis, telomere length and cellular senescence in Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia, scientific reports. Nat. Res. 12:17578. 10.1038/s41598-022-22400-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviv A., Hunt S. C., Lin J., Cao X., Kimura M., Blackburn E., et al. (2011). Impartial comparative analysis of measurement of leukocyte telomere length/DNA content by Southern blots and qPCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:e134. 10.1093/nar/gkr634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutou E., Vlachodimitropoulos D., Pappa V., Stürzbecher H.-T., Vorgias C. E. (2013). “DNA repair and telomeres — an intriguing relationship,” in New research directions in DNA repair, ed. Chen C. (Norderstedt: Books on Demand; ). 10.5772/56115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. H., Al-Chalabi A. (2017). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 377 162–172. 10.1056/NEJMra1603471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan T. M. (2019). Mechanisms of DNA replication and repair: Insights from the study of G-quadruplexes. Molecules 24:3439. 10.3390/molecules24193439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan T. M., Englezou A., Dalla-Pozza L., Dunham M. A., Reddel R. R. (1997). Evidence for an alternative mechanism for maintaining telomere length in human tumors and tumor-derived cell lines. Nat. Med. 3 1271–1274. 10.1038/nm1197-1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan T. M., Englezou A., Gupta J., Bacchetti S., Reddel R. R. (1995). Telomere elongation in immortal human cells without detectable telomerase activity. EMBO J. 14 4240–4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesare A. J., Reddel R. R. (2010). Alternative lengthening of telomeres: Models, mechanisms and implications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11 319–330. 10.1038/nrg2763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiò A., Mazzini L., D’Alfonso S., Corrado L., Canosa A., Moglia C., et al. (2018). The multistep hypothesis of ALS revisited: The role of genetic mutations. Neurology 91 e635–e642. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conomos D., Stutz M. D., Hills M., Neumann A. A., Bryan T. M., Reddel R. R., et al. (2012). Variant repeats are interspersed throughout the telomeres and recruit nuclear receptors in ALT cells. J. Cell Biol. 199 893–906. 10.1083/jcb.201207189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D. E., Zdraljevic S., Tanny R. E., Seo B., Riccardi D. D., Noble L. M., et al. (2016). The genetic basis of natural variation in Caenorhabditis elegans telomere length. Genetics 204 371–383. 10.1534/genetics.116.191148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockford C., Newton J., Lonergan K., Chiwera T., Booth T., Chandran S., et al. (2018). ALS-specific cognitive and behavior changes associated with advancing disease stage in ALS. Neurology 91 e1370–e1380. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z., Mangino M., Aviv A., Spector T., Durbin R. (2014). Estimating telomere length from whole genome sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 42:e75. 10.1093/nar/gku181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolzhenko E., van Vugt J. J. F. A., Shaw R. J., Bekritsky M. A., van Blitterswijk M., Narzisi G., et al. (2017). Detection of long repeat expansions from PCR-free whole-genome sequence data. Genome Res. 27 1895–1903. 10.1101/gr.225672.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant S. T. (2012). Telomerase-independent paths to immortality in predictable cancer sub-types. J. Cancer 3 67–82. 10.7150/jca.3965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratta P., Mizielinska S., Nicoll A. J., Zloh M., Fisher E. M., Parkinson G., et al. (2012). C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia forms RNA G-quadruplexes. Sci. Rep. 2:1016. 10.1038/srep01016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M., Bann D., Wiley L., Cooper R., Hardy R., Nitsch D., et al. (2014). Gender and telomere length: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 51 15–27. 10.1016/j.exger.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garton F. C., Trabjerg B. B., Wray N. R., Agerbo E. (2021). Cardiovascular disease, psychiatric diagnosis and sex differences in the multistep hypothesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 28 421–429. 10.1111/ene.14554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigg J. C., Shumayrikh N., Sen D. (2014). G-quadruplex structures formed by expanded hexanucleotide repeat RNA and DNA from the neurodegenerative disease-linked C9orf72 gene efficiently sequester and activate heme. PLoS One 9:e106449. 10.1371/journal.pone.0106449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakin-Smith V., Jellinek D. A., Levy D., Carroll T., Teo M., Timperley W. R., et al. (2003). Alternative lengthening of telomeres and survival in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Lancet 361 836–838. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12681-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardiman O., Al-Chalabi A., Chio A., Corr E. M., Logroscino G., Robberecht W., et al. (2017). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 3:17071. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycock P. C., Burgess S., Nounu A., Zheng J., Okoli G. N., Bowden J., et al. (2017). Association between telomere length and risk of cancer and non-neoplastic diseases a mendelian randomization study. JAMA Oncol. 3 636–651. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson J. D., Hannay J. A., McCarthy S. W., Royds J. A., Yeager T. R., Robinson R. A., et al. (2005). A robust assay for alternative lengthening of telomeres in tumors shows the significance of alternative lengthening of telomeres in sarcomas and astrocytomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 11 217–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hop P. J., Zwamborn R. A., Hannon E., Shireby G. L., Nabais M. F., Walker E. M., et al. (2022). Genome-wide study of DNA methylation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis identifies differentially methylated loci and implicates metabolic, inflammatory and cholesterol pathways. Philippe Couratier 18:37. 10.1101/2021.03.12.21253115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iacoangeli A., Al Khleifat A., Jones A. R., Sproviero W., Shatunov A., Opie-Martin S., et al. (2019). C9orf72 intermediate expansions of 24–30 repeats are associated with ALS. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 7:115. 10.1186/s40478-019-0724-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong C. M., Lee X. W., Wang X. (2013). Telomere shortening in human diseases. FEBS J. 280 3180–3193. 10.1111/febs.12326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T. S. (1995). Applications and limitations of polymerase chain reaction amplification. Chest 108 1393–1404. 10.1378/chest.108.5.1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzec P., Armenise C., Pérot G., Roumelioti F. M., Basyuk E., Gagos S., et al. (2015). Nuclear-receptor-mediated telomere insertion leads to genome instability in ALT cancers. Cell 160 913–927. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCombe P. A., Henderson R. D. (2010). Effects of gender in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Gend. Med. 7 557–570. 10.1016/j.genm.2010.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin L. R., Vajda A., Hardiman O. (2015). Heritability of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis insights from disparate numbers. JAMA Neurol. 72 857–858. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin R. L., Schijven D., van Rheenen W., van Eijk K. R., O’Brien M., Kahn R. S., et al. (2017). Genetic correlation between amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and schizophrenia. Nat. Commun. 8:14774. 10.1038/ncomms14774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta P. R., Jones A. R., Opie-Martin S., Shatunov A., Iacoangeli A., Khleifat A., et al. (2018). Younger age of onset in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is a result of pathogenic gene variants, rather than ascertainment bias. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 90 268–271. 10.1136/jnnp-2018-319089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millevoi S., Moine H., Vagner S. (2012). G-quadruplexes in RNA biology. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 3 495–507. 10.1002/wrna.1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnane J. P. (2006). Telomeres and chromosome instability. DNA Repair 5 1082–1092. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar R., Atzmon G. (2012). Telomere length and aging. Rev. Sel. Top. Telomere Biol. 1 3–30. 10.5772/2329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nieratschker V., Lahtinen J., Meier S., Strohmaier J., Frank J., Heinrich A., et al. (2013). Longer telomere length in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 149 116–120. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.06.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raczy C., Petrovski R., Saunders C. T., Chorny I., Kruglyak S., Margulies E. H., et al. (2013). Isaac: Ultra-fast whole-genome secondary analysis on illumina sequencing platforms. Bioinformatics 29 2041–2043. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche J. C., Rojas-Garcia R., Scott K. M., Scotton W., Ellis C. E., Burman R., et al. (2012). A proposed staging system for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 135 847–852. 10.1093/brain/awr351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatunov A., Mok K., Newhouse S., Weale M. E., Smith B., Vance C., et al. (2010). Chromosome 9p21 in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the UK and seven other countries: A genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol. 9 986–994. 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70197-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. N., Newhouse S., Shatunov A., Vance C., Topp S., Johnson L., et al. (2013). The C9ORF72 expansion mutation is a common cause of ALS+/-FTD in Europe and has a single founder. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 21 102–108. 10.1038/ejhg.2012.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub M. A., Conomos M. P., Keener R., Iyer K. R., Weinstock J. S., Yanek L. R., et al. (2019). Novel genetic determinants of telomere length from a multi-ethnic analysis of 75,000 whole genome sequences in TOPMed. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 10.1101/749010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Rheenen W., Sara L. P., Annelot M. D., Al Khleifat A., William J. B., Kevin P., et al. (2018). Project MinE: Study design and pilot analyses of a large-scale whole-genome sequencing study in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 26 1537–1546. 10.1038/s41431-018-0177-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rheenen W., Shatunov A., Dekker A. M., McLaughlin R. L., Diekstra F. P., Pulit S. L., et al. (2016). Genome-wide association analyses identify new risk variants and the genetic architecture of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 48 1043–1048. 10.1038/ng.3622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rheenen W., van der Spek R. A. A., Bakker M. K., van Vugt J. J. F. A., Hop P. J., Zwamborn R. A. J., et al. (2021). Common and rare variant association analyses in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis identify 15 risk loci with distinct genetic architectures and neuron-specific biology. Anneke J. Van Der Kooi 17:129. 10.1101/2021.03.12.21253159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westeneng H. J., Debray T. P. A., Visser A. E., van Eijk R. P. A., Rooney J. P. K., Calvo A., et al. (2018). Prognosis for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Development and validation of a personalised prediction model. Lancet Neurol. 17 423–433. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30089-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Li S., Stohr B. A. (2013). The role of telomere biology in cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 8 49–78. 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Sun H., Yang D., Liu Y., Zhang X., Chen H., et al. (2019). Evaluation of the selectivity of G-quadruplex ligands in living cells with a small molecule fluorescent probe. Anal. Chim. Acta X 2:100017. 10.1016/j.acax.2019.100017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Hishimoto A., Otsuka I., Watanabe Y., Numata S., Yamamori H., et al. (2018). Longer telomeres in elderly schizophrenia are associated with long-term hospitalization in the Japanese population. J. Psychiatr. Res. 103 161–166. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are deposited in the Project MinE consortium public repository (http://databrowser.projectmine.com).