Abstract

Angelman syndrome (AS) is a severe neurodevelopmental disorder caused by loss of expression of the maternally-inherited UBE3A on chromosome 15q11.2. In AS due to a chromosomal deletion that encompasses UBE3A, paternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 15, or imprinting defects (ImpD), the SNRPN locus is unmethylated, while in neurotypical individuals, it iŝ50% methylated. We present the developmental profile of two adults with mild AS assessed using standardized behavioral and neurodevelopmental measures. Both had intellectual disability with unusually advanced verbal communication skills compared to other individuals with AS. Methylation of the SNRPN locus was examined using Methylation Specific Quantitative Melt Analysis (MS-QMA) in different tissues at one time point for participant A (22 years) and two time points for participant B (T1: 22 years, T2: 25 years), and these levels were compared to a typical AS cohort. While participant A showed methylation levels comparable to the typical AS cohort, participant B showed methylation mosaicism in all tissues at both time points and changes in methylation levels from T1 to T2. AS should be considered in individuals with intellectual disability and verbal speech who may not have the typical symptoms of AS.

Keywords: Mosaicism, Imprinting defect, Atypical Angelman syndrome, Developmental disabilities, Intellectual disabilities

1. Introduction

Angelman syndrome (AS) is a rare neurogenetic disorder characterized by developmental delay, limited speech, and seizures. It is caused by a lack of functional UBE3A, encoded by the maternal UBE3A in neurons (Bird, 2014). Expression of UBE3A in neurons is regulated by the Prader-Willi syndrome imprinting center (PWS-IC), which includes SNRPN promoter upstream of UBE3A; the PWS-IC is unmethylated on the paternal allele, but methylated on the maternal allele. Thus, this region is usually ~50% methylated. In AS individuals with a chromosomal deletion that encompasses UBE3A, paternal uniparental disomy (UPD) of chromosome 15, or an imprinting defect (ImpD), the maternal allele would either be absent or unmethylated, so the region would be unmethylated (Bird, 2014; Buiting, 2010).

ImpDs occur in ~8% of AS individuals, 30–40% of whom are mosaic, with reported SNRPN methylation levels up to 20% (Bird, 2014; Buiting, 2010; Buiting et al., 2003; Nazlican et al., 2004). This mosaicism often results in an atypical AS phenotype, presumably due to the normal expression of UBE3A in some cells (Le Fevre et al., 2017). However, investigations on how the degree of methylation in AS individuals with mosaic ImpD correlates with phenotypic spectrum and severity are limited (Le Fevre et al., 2017; Nazlican et al., 2004), with no studies to date reporting methylation levels between tissues or over time in these individuals. Additionally, few studies on mosaic AS have utilized standardized clinical assessments (Carson et al., 2019; Fairbrother et al., 2015; Russo et al., 2015). This study describes the developmental profiles of two adults with atypical AS due to presumed mosaic ImpD. Methylation levels at the imprinted locus were examined between tissues at two time points and compared to levels in neurotypical controls and individuals with non-mosaic AS (Baker et al., 2020).

2. Clinical report

2.1. Editorial policies and ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Royal Children’s Hospital and Boston Children’s Hospital research ethics boards. Informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians of the participants.

2.2. Clinical history

Participant A was a 21-year-old woman at the time of initial assessment who was born full term with reportedly normal growth parameters. She had frequent feeding difficulties in infancy but gained weight at a normal rate. She had sleep difficulties during infancy, which resolved in adolescence. She never had seizures. Her developmental milestones were delayed (Table S1). Concerns for global developmental delay were raised when she was two years old. At six years old, she was diagnosed with “non-deletion” AS following abnormal results for SNRPN methylation analysis but normal fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) for the 15q11.2q13 region. She was subsequently diagnosed as having an ImpD due to an epimutation following a normal chromosomal microarray, uniparental disomy analysis, and PWS-IC deletion analysis. Due to her mild presentation, she was suspected of having somatic mosaicism.

She was assessed with the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Third Edition (Vineland-3; Sparrow, Cincchetti, & Saulnier, 2016), the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second Edition (WASI-II; Wechsler, 2011), and the Aberrant Behavior Checklist-Community (ABC-C; Aman, Singh, Stewart, & Field, 1985) at 21 years of age, and subsequently with the PWS Behavior Questionnaire (PWSBQ; Avrahamy et al., 2014) at 22 years of age. She has been attending a live-in boarding school for children with disabilities since age 14. Her physical appearance was notable for brachycephaly and a flat face, widely spaced teeth, thin vermilion of the upper lip, and hypotonia. She was obese with a BMI of 39.4 kg/m2.

Participant B was a 22-year-old woman at the time of initial assessment (Patient 1 in Le Fevre et al., 2017) who was born full term with normal growth parameters. She was not reported to be hypotonic, fed well during infancy, and gained weight easily. She tended to drool and protrude her tongue. She had sleep difficulties, usually sleeping for no more than four continuous hours. She met her early developmental milestones on time (Table S1), and she had no history of seizures. She began speech and occupational therapy at ~6 years old. At 10 years old, she was found to have an abnormal SNRPN promoter methylation pattern and was diagnosed with mosaic AS, subsequently found to be due to an epimutation, as previously described (Le Fevre et al., 2017).

She was assessed at 22 years of age with the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV; Wechsler, 2008) and the ABC-C, and subsequently with the Vineland-3 and PWSBQ at 25 years of age. At the time of both assessments, she lived in her family home with her biological parents. At initial assessment, she was obese with a BMI of 30.5 kg/m2.

2.3. Developmental assessments

Table 1 summarizes the results of the developmental assessments. Participant A’s overall IQ was in the Extremely Low range, and she had a slightly higher verbal than non-verbal IQ. She displayed more advanced receptive than expressive communication and used complex sentences with two or more clauses, such as “Dad, if you do it for me, I will be so happy.” Participant A’s overall adaptive functioning (Vineland-3) fell in the Extremely Low range. Her Vineland-3 daily living skills were notable for her ability to cut her food, use the stove or oven for cooking, and do laundry independently. Her mother reported few maladaptive behaviors with particularly low irritability and hyperactivity scores on the ABC-C (Table S2). She scored below a PWS normed sample on the PWSBQ (Table S2).

Table 1.

Intellectual and adaptive functioning of participants A and B.

| Intellectual Functioning | Participant A | Participant B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WASI-II | WAIS-IV | |||

| Intellectual Functioning | Standard Score (M = 100, SD = 15) | T-Scores (M = 50, SD = 10) | Standard Score (M = 100, SD = 15) | Subtest Scaled Score (M = 10, SD = 3) |

| Overall/Full Scale IQ | 52 | 42 | ||

| Nonverbal IQ/Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI) | 48 | 50 | ||

| Block Design | 21 | 1 | ||

| Matrix Reasoning | 21 | 1 | ||

| Visual Puzzles | NA | 2 | ||

| Verbal IQ/Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) | 61 | 52 | ||

| Vocabulary | 29 | 3 | ||

| Similarities | 23 | 1 | ||

| Information | NA | 2 | ||

| Adaptive Functioning | Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale, Third Edition | |

|---|---|---|

| Age Equivalent | Age Equivalent | |

| Communication | ||

| Receptive | 11 years, 0 months | 1 year, 10 months |

| Expressive | 5 years, 4 months | 2 years, 1 month |

| Written | 9 years, 0 months | 3 years, 10 months |

| Daily Living Skills | ||

| Personal | 8 years, 4 months | 3 years, 0 months |

| Domestic | 15 years, 0 months | <3 years, 0 months |

| Community | 9 years, 10 months | <3 years, 0 months |

| Socialization | ||

| Interpersonal Relationships | 3 years, 2 months | 1 years, 3 months |

| Play/Leisure | 11 years, 9 months | 1 year, 2 months |

| Coping Skills | 7 years, 7 months | <2 years, 0 months |

| Adaptive Behavior Composite | 52 | 20 |

Note. M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation; NA = Not applicable; WASI-II = Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second Edition; WAIS-IV = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Fourth Edition.

Participant B’s overall intellectual functioning was also in the Extremely Low range, with approximately equivalent performance between verbal and non-verbal tasks, and all WAIS-IV index scores fell in the Extremely Low range. Similarly, while her expressive and receptive communication skills were similar, participant B scored in the Extremely Low range and achieved lower age equivalents than participant A for all Vineland-3 domains. Participant B used simple phrase speech with three to four utterances, such as “I scare you” and “I TV at home”. Participant B was also reported to have few maladaptive behaviors with a particularly low hyperactivity score on the ABC-C, but she scored within a PWS-normed sample on multiple domains of the PWSBQ (Table S2).

2.4. Sample processing and SNRPN promoter methylation analysis

Saliva and buccal epithelial cell (BEC) samples were collected using the Oragene® DNA Self-Collection Kit (Genotek, ON, Canada) and Gentra Purgene Buccal Cell Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), respectively. Participant B was assessed at two time points and provided samples at these times points (T1: 22 years and T2: 25 years); she also provided a venous blood sample at T1 (15 ml in an EDTA tube). Changes in promoter methylation levels over time have been shown in other conditions associated with epigenetic changes and mosaicism (e,g., fragile X syndrome; Godler et al., 2013). Collection of samples at two time points from Participant B allowed us to explore SNRPN promoter methylation changes over time in this mosaic AS patient. Participant A was only assessed at one time point and therefore only provided one set of saliva and BEC samples. Saliva swab and BEC samples were processed per manufacturer’s instructions. No brush or swab samples had blood contamination upon visual inspection by two staff members at the time of sample receipt. DNA was extracted from all samples using the QIA-symphony DSP DNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and bisulfite converted using the EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The bisulfite converted DNA was then analyzed using Methylation Specific Quantitative Melt Analysis (MS-QMA) to determine SNRPN promoter methylation levels using previously established protocols (Godler et al., 2022), and as detailed in Supplemental Note 1.

2.5. Analysis of SNRPN methylation

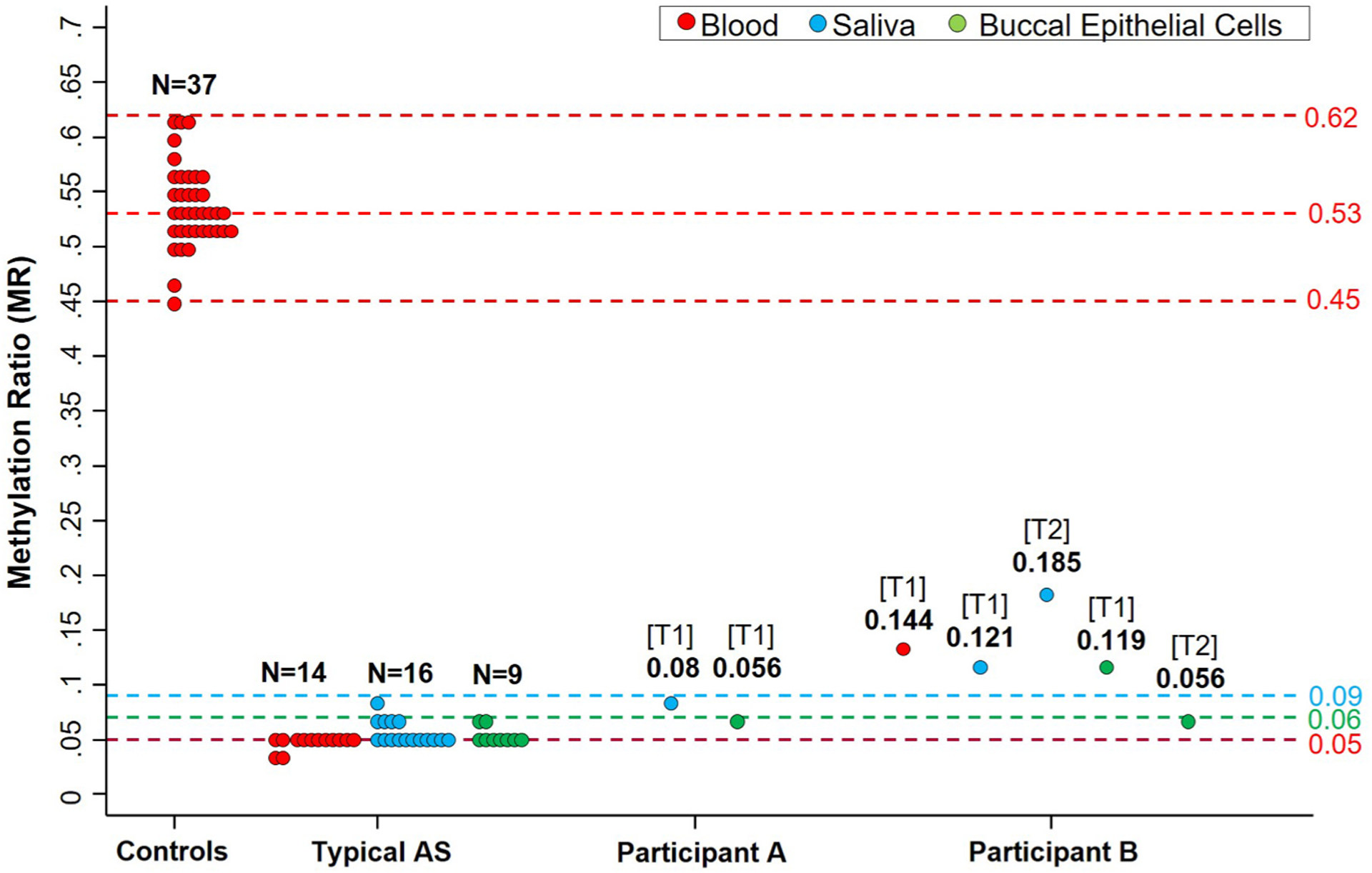

MS-QMA was used to examine methylation of the SNRPN promoter in BEC, saliva DNA, and blood (participant B only). Methylation is presented as methylation ratio (MR), which is an output of MS-QMA where approximately 0.05 MR is the technical limit of detection, with all values at 0.05 MR or below considered completely unmethylated. Participant A showed MR in saliva and in BEC within the typical AS range and significantly below the levels observed in neurotypical controls (Fig. 1). Participant B showed consistent MRs between 0.12 and 0.14 at T1 across tissues (above the typical AS range, but below the levels in neurotypical controls), consistent with presence of methylation mosaicism at this locus. Interestingly, the MR in saliva increased from T1 (0.12) to T2 (0.19), and the MR in BECs decreased from T1 (0.12) to T2 (0.056) in participant B (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. SNRPN promoter methylation analysis using MS-QMA in blood, saliva, and buccal epithelial cells (BEC) from neurotypical controls, typical AS, and participants A and B.

Note: Maximum and minimum values for the control cohort are 0.62 and 0.45 methylation ratio (MR) respectively, with mean and median at 0.53 MR. For typical AS, the maximum value in blood was 0.05 MR, BEC was 0.06 MR, and saliva was 0.09 MR. These maximum MR values are MS-QMA cut-offs representing the unmethylated non-mosaic state for the SNRPN promoter (MS-QMA technical limit of detection). T1 and T2 indicate sampling at time points 1 and 2 respectively. Numbers below T1 and T2 indicate MRs for the respective samples.

3. Discussion

Individuals with AS due to mosaic ImpD may exhibit unusually mild symptoms, including mild intellectual disability and advanced expressive communication beyond that expected in AS (Carson et al., 2019; Le Fevre et al., 2017). Participants A and B had intellectual disability based on tests of intelligence and adaptive functioning. However, it is important to note that most individuals with AS would score at the floor of these specific tests, which participants A and B did not. While the overall adaptive functioning (Vineland-3) of both participants was in the Extremely Low range, participant A’s age equivalent scores reflected her advanced communication and daily living skills (Table 1), which were also consistent with her ability to communicate verbally and live semi-independently, compared to participant B and to individuals with non-mosaic AS (Den Besten et al., 2021).

We cannot directly compare the intellectual and adaptive capabilities of our participants to previously reported mosaic AS individuals since those reports were in young children (Carson et al., 2019; Fairbrother et al., 2015; Russo et al., 2015) or did not utilize standardized developmental assessments (Aypar et al., 2016; Le Fevre et al., 2017; Russo et al., 2015). Based on subjective descriptions, participant A had more advanced expressive communication than most individuals reported with mosaic ImpD, including having an extensive vocabulary (over 100 words), the ability to use complex sentences, and the ability to write at a 9-year-old level. Case reports and series of individuals with mosaic ImpD have reported vocabularies of 50 to over 100 words, while one study utilizing parent-reported surveys found that ~20% of individuals with mosaic AS had a vocabulary of over 1000 words (Carson et al., 2019; Le Fevre et al., 2017). In contrast, participant B’s expressive communication skills were more consistent with previously reported mosaic AS cases. She also had a vocabulary of over 100 words, but used simple phrase speech and had writing skills at a 3-year 10-month-old level. Participant A also possessed advanced daily living skills that allowed her to live a semi-independent life. Her unusually high level of functioning compared to other individuals with mosaic ImpD may be partly due to her age at assessment; most reported cases of mosaic ImpD were in children, whereas participant A’s adaptive functioning was assessed when she was 21 years old. She, therefore, demonstrated the level of functioning that some individuals with mosaic AS may eventually develop.

The behavioral features often observed in AS include frequent laughter, hyperactivity, and irritability, and individuals with ImpD tend to exhibit more severe hyperactivity and irritability than those with a deletion (Sadhwani et al., 2019). Our participants displayed low hyperactivity (Table S2), and only 37% of reported individuals with mosaic ImpD displayed frequent laughter (Le Fevre et al., 2017). In addition to their advanced developmental profiles, this atypical behavioral presentation may further complicate diagnosis of individuals with mosaic ImpD.

PWS symptoms have been observed in individuals with AS due to ImpD (Gillessen-Kaesbach et al., 1999). Of 25 individuals with mosaic ImpD previously reported, 32% (8/25) had obesity and 55% (11/20) had hyperphagia, both of which are symptoms of PWS (Le Fevre et al., 2017). On the PWSBQ, participant B reported symptoms that closely resembled PWS in several domains, while participant A reported low levels of PWS-like symptoms in all domains (Table S2). However, participant A had hyperphagia and scored higher than participant B in the “food-seeking behaviors” domain. Both participants were obese at initial assessment. Despite both participants having overlapping symptoms with PWS and lacking typical features of AS (e.g., verbal speech and lack of seizures), neither participant was considered to have PWS prior to their confirmed diagnoses of AS. Based on facial features and limited verbal speech, Participant B was considered more likely to be mosaic AS.

It has been suggested that ~90% of individuals with ImpD have an epimutation, which results in the maternal IC resembling the epigenotype of the paternal IC (Buiting et al., 2003). Of these, 30–40% are thought to lose their maternal imprint post-zygotically, resulting in somatic methylation mosaicism in which some cells carry the maternal 15q11q13 methylation pattern and some cells do not (Buiting, 2010; Buiting et al., 2003). Our participants’ mild phenotypes might be due to the presence of a normal maternal 15q11q13 methylation pattern in some cells that varies across tissues and/or changes over time. One study examined SNRPN promoter methylation levels in a cohort of patients with mosaic ImpD and found that higher methylation levels to be correlated with a milder clinical phenotype, although these results were not statistically significant (Nazlican et al., 2004). Another report examined methylation in three patients with mosaic ImpD, including participant B, and did not find the highest functioning patient to have the highest level of normally-methylated cells (Le Fevre et al., 2017). We analyzed methylation of the SNRPN promoter from BEC and saliva from both participants via MS-QMA. Based on their clinical presentations, we expected participant A to have higher MRs since she displayed more advanced adaptive functioning and communication than participant B. However, participant B had higher MRs in both saliva and BECs. Additionally, the MRs of participant A were in the range of the typical AS cohort, which was not consistent with the differences in the developmental functioning, adaptive functioning, and expressive communication skills observed between participant A and typical AS.

The discrepancy between clinical severity and SNRPN promoter methylation levels between our participants may be due to varying levels of methylation across different tissues. It is possible that other unrecognized etiologies, such as environmental or polygenic factors, could have contributed to the milder phenotype seen in participant A. However, it is more likely that we were unable to sample the tissues that were critical for neurodevelopment, such as neurons in the brain, where the MR could have been higher, thereby resulting in greater neuronal UBE3A expression. Unfortunately, we did not have access to blood or samples from other tissues from participant A, which might have demonstrated higher levels of SNRPN promoter methylation within the mosaic range. Future studies should examine the relationships between SNRPN promoter methylation levels in different tissues and phenotypic severity in a cohort of individuals with mosaic ImpD. These studies should also use other approaches that examine a larger area of the SNRPN promoter, which may reveal mosaicism for CpG sites not directly targeted by MS-QMA.

This is the first study we are aware of that examined changes in SNRPN promoter methylation over time. Participant B’s saliva MR increased from T1 to T2, while her BEC MR decreased from T1 to T2. While these results may suggest that methylation levels in individuals with mosaic AS can change over time, these observations may also be due to sampling bias of mosaic tissues. Future studies utilizing repeated measures in multiple tissues from a much larger number of individuals with atypical AS would be needed to validate this observation as it may have implications for interpretation of SNRPN promoter methylation data from peripheral tissues.

Due to the atypical presentation of individuals with mosaic ImpD described here and elsewhere in the literature (Aypar et al., 2016; Carson et al., 2019; Le Fevre et al., 2017; Russo et al., 2015), individuals who have AS due to ImpD may not be referred for AS-specific testing and therefore may not receive appropriate treatment and interventions. AS-specific testing should be considered in individuals with mild to moderate intellectual disability and greater receptive than expressive communication skills, especially if PWS-like symptoms are also present. The presence of speech and absence of typical AS behaviors should not preclude a clinical suspicion for AS due to mosaic ImpD. Future studies should explore identification of additional mosaic AS cases in other patient populations with overlapping clinical features, such as patients referred for chromosomal microarray testing due to developmental delay of unknown etiology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and their families for contributing to this study.

Funding

This study was supported by 1R01FD006003 from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (awarded to W.H.T), Next Generation Clinical Researchers Program - Career Development Fellowship, funded by the Medical Research Future Fund (MRF1141334 to D.E.G.), Foundation for Angelman Syndrome Therapeutics Australia (AUS) (to D.E.G and E.K.B) and Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program, Australia (to D.E.G and E.K.B).

Footnotes

Author statement

Emma K. Baker: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Supervision. David E. Godler: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Tracy Dudding-Byth: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. Catherine F. Merton: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Visualization, Project administration. Wen-Hann Tan: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Anjali Sadhwani: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Visualization, Supervision.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmg.2022.104456.

References

- Aman MG, Singh NN, Stewart AW, Field CJ, 1985. The aberrant behavior checklist: a behavior rating scale for the assessment of treatment effects. Am. J. Ment. Defic 89 (5), 485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avrahamy H, Pollak Y, Shriki-Tal L, Genstil L, Hirsch HJ, Gross-Tsur V, Benarroch F, 2014. A disease specific questionnaire for assessing behavior in individuals with Prader–Willi syndrome. Compr. Psychiatr 58, 189–197. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aypar U, Hoppman NL, Thorland EC, Dawson DB, 2016. Patients with mosaic methylation patterns of the Prader-Willi/Angelman Syndrome critical region exhibit AS-like phenotypes with some PWS features. Mol. Cytogenet 9 (1), 26. 10.1186/s13039-016-0233-0, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker EK, Butler MG, Hartin SN, Ling L, Minh B, Francis D, Godler DE, 2020. Relationships between UBE3A and SNORD116 expression and features of autism in chromosome 15 imprinting disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 10 (1), 362. 10.1038/s41398-020-01034-7, 362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird LM, 2014. Angelman syndrome: review of clinical and molecular aspects. Appl. Clin. Genet 7, 93–104. 10.2147/TACG.S57386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buiting K, 2010. Prader–willi syndrome and Angelman syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet Part C, Seminars in medical genetics 154C (3), 365–376. 10.1002/ajmg.c.30273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buiting K, Groß S, Lich C, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, El-Maarri O, Horsthemke B, 2003. Epimutations in Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes: a molecular study of 136 patients with an imprinting defect. Am. J. Hum. Genet 72 (3), 571–577. 10.1086/367926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson RP, Bird L, Childers AK, Wheeler F, Duis J, 2019. Preserved expressive language as a phenotypic determinant of Mosaic Angelman Syndrome. Mol. Gene. Genom. Med 7 (9) 10.1002/mgg3.837 e837-n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den Besten IE, de Jong RF, Geerts-Haages A, Brüggenwirth H, Koopmans M, Brooks A, deWit MCY, 2021. Clinical aspects of a large group of adults with Angelman syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet 185 (1), 168–181. 10.1002/ajmg.a.61940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother LC, Cytrynbaum C, Boutis P, Buiting K, Weksberg R, Williams C, 2015. Mild Angelman syndrome phenotype due to a mosaic methylation imprinting defect. Am. J. Med. Genet 167 (7), 1565–1569. 10.1002/ajmg.a.37058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Demuth S, Thiele H, Theile U, Lich C, Horsthemke B, 1999. A previously unrecognised phenotype characterised by obesity, muscular hypotonia, and ability to speak in patients with Angelman syndrome caused by an imprinting defect. Eur. J. Hum. Genet.: EJHG (Eur. J. Hum. Genet.) 7 (6), 638–644. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godler DE, Inaba Y, Shi EZ, Skinner C, Bui QM, Francis D, Slater HR, 2013. Relationships between age and epi-genotype of the FMR1 exon 1/intron 1 boundary are consistent with non-random X-chromosome inactivation in FM individuals, with the selection for the unmethylated state being most significant between birth and puberty. Hum. Mol. Genet 22 (8), 1516–1524. 10.1093/hmg/ddt002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godler DE, Ling L, Gamage D, Baker EK, Bui M, Field MJ, Amor DJ, 2022. Feasibility of screening for chromosome 15 imprinting disorders in 16 579 newborns by using a novel genomic workflow. JAMA Netw. Open 5 (1), e2141911. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.41911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Fevre A, Beygo J, Silveira C, Kamien B, Clayton-Smith J, Colley A, Dudding-Byth T, 2017. Atypical Angelman syndrome due to a mosaic imprinting defect: Case reports and review of the literature. Am. J. Med. Genet 173 (3), 753–757. 10.1002/ajmg.a.38072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazlican H, Zeschnigk M, Claussen U, Michel S, Boehringer S, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Horsthemke B, 2004. Somatic mosaicism in patients with Angelman syndrome and an imprinting defect. Hum. Mol. Genet 13 (21), 2547–2555. 10.1093/hmg/ddh296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo S, Mainini E, Chiara Luoni C, Francesca Cogliati F, Giorgini V, Bonati M, Larizza L, 2015. Somatic mosaicism as modulator of the global and intellectual phenotype in epimutated Angelman syndrome patients. J. Intellect. Disability - Diagn.Treatment 3 (3), 126–137. 10.6000/2292-2598.2015.03.03.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadhwani A, Willen JM, LaVallee N, Stepanians M, Miller H, Peters SU, Tan WH, 2019. Maladaptive behaviors in individuals with Angelman syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet 179 (6), 983–992. 10.1002/ajmg.a.61140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow S, Cincchetti D, Saulnier C, 2016. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, third ed. Pearson, San Antonio, TX: (Vineland-3). [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D, 2008. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV). Pearson, San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D, 2011. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, second ed. Pearson, San Antonio, TX: (WASI-II). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.