Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) preferentially affects epithelia of the upper and lower respiratory tract. Thus, impairment of kidney function has been primarily attributed until now to secondary effects such as cytokine release or fluid balance disturbances. We provide evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can directly infiltrate a kidney allograft. A 69-year-old male, who underwent pancreas-kidney transplantation 13 years previously, presented to our hospital with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia and impaired pancreas and kidney allograft function. Kidney biopsy was performed showing tubular damage and an interstitial mononuclear cell infiltrate. Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction from the biopsy specimen was positive for SARS-CoV-2. In-situ hybridization revealed SARS-CoV-2 RNA in tubular cells and the interstitium. Subsequently, he had 2 convulsive seizures. Magnetic resonance tomography suggested meningoencephalitis, which was confirmed by SARS-CoV-2 RNA transcripts in the cerebrospinal fluid. The patient had COVID-19 pneumonia, meningoencephalitis, and nephritis. SARS-CoV-2 binds to its target cells through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, which is expressed in a broad variety of tissues including the lung, brain, and kidney. SARS-CoV-2 thereby shares features with other human coronaviruses including SARS-CoV that were identified as pathogens beyond the respiratory tract as well. The present case should provide awareness that extrapulmonary symptoms in COVID-19 may be attributable to viral infiltration of diverse organs.

KEYWORDS: clinical research/practice, infection and infectious agents – viral, infectious disease, kidney (allograft) function/dysfunction, kidney transplantation/nephrology, pancreas/simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation, translational research/science

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

1. INTRODUCTION

There are an increasing number of reports on the clinical course of coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in solid organ transplant recipients.1, 2, 3 Due to their comorbidities and immunosuppressive therapy, transplant recipients are presumed to be at increased risk for adverse outcome. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) preferentially infects cells in the respiratory tract. Thus, first reports on the disease primarily focused on pulmonary manifestations in both the general and the transplant population.4 In the recent course of the pandemic, however, first autopsy series data revealed a multiorgan tropism of the virus including the kidney.5 , 6 Kidney injury in COVID-19 may thereby be not only the consequence of systemic inflammation but also of direct infection of renal cells. To date, there are no data on kidney biopsies during COVID-19. Here, we describe a case of multiorgan involvement of SARS-CoV-2 in a pancreas-kidney transplant recipient. Kidney biopsy demonstrated allograft infection by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and RNA scope in-situ hybridization.

2. CASE REPORT

A 69-year-old male pancreas-kidney transplant recipient was admitted to an external hospital for fever, cough, and diarrhea 13 years after pancreas--kidney transplantation. His immunosuppressive medication consisted of tacrolimus and mycophenolic acid. The nasopharyngeal swab test was positive for SARS-CoV-2 (reverse transcriptase [RT]-PCR; SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR: Altona Diagnostics, Hamburg, Germany). Since he had a diarrhea-associated increase of tacrolimus trough levels (trough level at admission >40 ng/mL; 4.6 ng/mL before admission in January), the drug was paused. Within the next 10 days, kidney and pancreas graft function deteriorated, and he was transferred to our transplant center. On admission, both pancreas and kidney graft function were substantially impaired: Insulin therapy had to be initiated promptly and his serum creatinine concentration had increased from baseline values of 1.2-2.2 mg/dL. Further laboratory findings presented absolute lymphopenia and an elevation of lactate dehydrogenase and C-reactive protein. Computed tomography of the chest revealed bilateral ground-glass opacity and lung consolidation suggesting subacute COVID-19 pneumonia ( Figure 1). Mycophenolic acid was paused and intravenous hydrocortisone (200 mg/d) was administered. Kidney allograft biopsy was performed showing mild acute tubular damage and a mononuclear inflammatory infiltration ( Figure 2A). According to Banff criteria 2017, there was no cellular or antibody-mediated rejection.7 RT-PCR from the biopsy specimen was positive for SARS-CoV-2, while being negative in a peripheral blood sample. In-situ hybridization (RNA in-situ hybridization: Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, NJ) detected positive staining for viral RNA of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in tubular epithelial cells as well as in the interstitium (Figure 2B). Quantification of positive signals yielded 26 signals per biopsy area.

FIGURE 1.

Thoracic computed tomography showing bilateral ground-glass opacity (arrow) and lung consolidation in subacute coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia

FIGURE 2.

Kidney allograft biopsy showing (A) an interstitial mononuclear cell infiltrate (arrow) and tubular damage in PAS staining. (B) In-situ hybridization using RNA scope visualized SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA as dotted red staining in tubules and interstitial tissue. PAS, periodic acid–Schiff; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

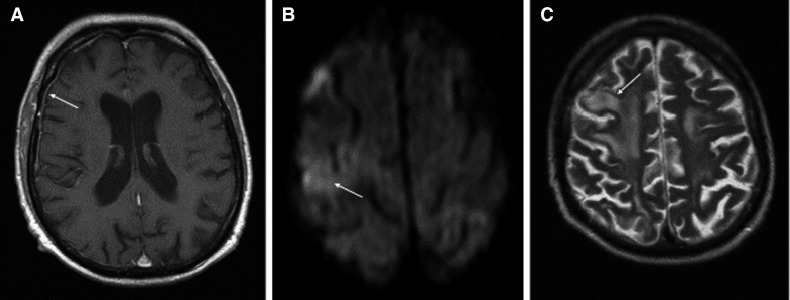

The patient needed oxygen supply (maximum 4 L/min) but no mechanical ventilation. Within 1 week he was recovering continuously from cough, dyspnea, and diarrhea. Computed tomography demonstrated regression of pulmonary infiltration and tacrolimus was reinitiated. Three days later, the patient’s general condition deteriorated again. He reported a recurrence of diarrhea, increasing fatigue, and he had 2 convulsive seizures. Magnetic resonance tomography showed linear meningeal enhancement ( Figure 3A) and white matter edema without mass effect (Figure 3C), thereby suggesting meningoencephalitis. Laboratory examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) revealed a cell count of 1/µL (100% lymphocytes), a protein concentration of 110 mg/dL, and a normal glucose concentration of 93 mg/dL. Supportive for the diagnosis of viral meningoencephalitis was a high intrathecal oligoclonal IgG synthesis (13.20 mg/dL, reference <3.4 mg/dL). Whereas the infectiological work-up was unremarkable for bacteria and herpes viruses, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in the cerebrospinal fluid. On neurological examination, he had a left-sided neglect. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit. Levetiracetam and hydroxychloroquine were administered and tacrolimus (trough level 3 ng/mL at the timepoint of the seizure) was withheld again. Within the following days his condition improved gradually and after 1 week he left the intensive care unit. Neurologic symptoms disappeared and his serum creatinine concentration returned to 1.2 mg/dL. Pancreas transplant function recovered partially. There was still a need for low-dose insulin administration at discharge from the hospital. SARS-CoV-2 RT--PCR performed in blood samples every 3-5 days remained negative during the whole follow-up. Figure 4 summarizes the clinical course of our patient.

FIGURE 3.

Magnetic resonance tomography of the brain. A, Transversal T1-weighted images showing linear meningeal enhancement (arrow). B, Diffusion-weighted images showing a subtle area of diffusion restriction (arrow), and C, T2-weighted images showing edema without mass effect (hyperintensity in the white matter)

FIGURE 4.

Timeline of the clinical course. ICU, intensive care unit; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

3. DISCUSSION

COVID-19 primarily affects epithelia of the upper and lower respiratory tract.8 The present case demonstrates, however, that SARS-CoV-2 can infiltrate diverse organs. The patient had COVID-19 pneumonia, meningoencephalitis, and nephritis. Moreover, pancreas allograft dysfunction occurred in association with COVID-19. Noteworthy, the detection of SARS-CoV-2 transcripts in the kidney allograft tissue was successful while blood samples tested negative. Thus, a false-positive finding caused by perfusion of the renal graft tissue with the infected blood is unlikely. These findings are confirmed by the results of RNA in-situ hybridization. SARS-CoV-2 binds to its target cells through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, which is expressed in a broad variety of tissues including the lung, brain, and kidney.9 , 10

This is the first detection of SARS-CoV-2 in a kidney allograft. So far, deterioration of kidney function in COVID-19 has primarily been explained by cytokine release, organ cross-talk, or fluid balance disturbances.11 None of the available reports reported direct viral infiltration as the source of impaired renal function. The present mononuclear cell infiltrate accompanied by the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in the kidney allograft indicates, however, that the virus is able to enter renal parenchyma and may cause interstitial nephritis. Recent postmortem histopathological analyses showed positive immunostaining with SARS-CoV nucleoprotein antibody in tubules, which supports our findings.6 After discharge of the patient, an autopsy series confirmed the multiorgan tropism of the virus. SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in all kidney compartments with preferential targeting of glomerular cells.5

Beyond COVID-19 pneumonia and allograft infiltration, the patient had meningoencephalitis. Neurologic symptoms have been described in one third of a COVID-19 cohort in Wuhan with a broad spectrum of symptoms.12 Whereas headaches, anosmia, dysgeusia, and neuralgia occur even in mild courses of the disease, epilepsy, acute cerebrovascular disease, and disturbed consciousness have been described in severe cases of COVID-19.13 Reports of COVID-19 encephalitis are rare.14 , 15 To the best of our knowledge, the present case constitutes the first description of meningoencephalitis in a solid organ recipient. The case demonstrates an important diagnostic aspect of SARS-CoV-2-associated meningoencephalitis: The cell count in CSF may be unexpectedly low, potentially due to the severe lymphopenia in COVID-19. In case of suggestive clinical presentation and imaging findings, PCR for SARS-CoV-2 should be pursued in CSF, even though cell count might be low.

Data on several cohorts of transplant recipients with COVID-19 have been published so far. Whereas a small cohort of 15 patients showed clinical courses comparable to the general population,16 larger cohorts of 36 and 90 transplant recipients showed more severe courses and a substantially increased mortality of 18%-28% compared to the general population.1 , 2 Compared to the general population, cough is more common, whereas fever may be absent in up to one half.17 Among 701 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, 43.9% had proteinuria and 26.7% had hematuria.18 This finding was interpreted mainly as being due to immune system activation during active SARS-CoV-2 infection.19 The present findings show, however, that direct infection of renal cells may contribute to renal disease in COVID-19 as well.

With the potential to infiltrate various organs, SARS-CoV-2 shares features with other human coronaviruses including SARS-CoV that were identified as pathogens beyond the respiratory tract as well.20 The present case should provide awareness in the transplant community that extrapulmonary symptoms in COVID-19 patients may be attributable to viral infiltration of diverse organs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding information German Research Foundation, SFB 1350, TP C2 (E. Vonbrunn). Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pereira MR, Mohan S, Cohen DJ, et al. COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients: Initial report from the US epicenter. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(7):1800–1808. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akalin E, Azzi Y, Bartash R, et al. COVID-19 and kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(25):2475–2477. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2011117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Husain SA, Dube G, Morris H, et al. Early outcomes of outpatient management of kidney transplant recipients with coronavirus disease 2019 [published online ahead of print May 18, 2020]. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 10.2215/CJN.05170420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Zhu L, Gong N, Liu B, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in immunosuppressed renal transplant recipients: a summary of 10 confirmed cases in Wuhan, China. Eur Urol. 2020;77(6):748–754. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puelles VG, Lütgehetmann M, Lindenmeyer MT, et al. Multiorgan and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2 [published online ahead of print May 13, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 10.1056/NEJMc2011400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Su H, Yang M, Wan C, et al. Renal histopathological analysis of 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int. 2020;98(1):219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haas M, Loupy A, Lefaucheur C, et al. The Banff 2017 Kidney Meeting Report: revised diagnostic criteria for chronic active T cell-mediated rejection, antibody-mediated rejection, and prospects for integrative endpoints for next-generation clinical trials. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(2):293–307. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1101/2020.02.06.20020974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol. 2020;94(7) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. e00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harmer D, Gilbert M, Borman R, Clark KL. Quantitative mRNA expression profiling of ACE 2, a novel homologue of angiotensin converting enzyme. FEBS Lett. 2002;532(1–2):107–110. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03640-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ronco C, Reis T. Kidney involvement in COVID-19 and rationale for extracorporeal therapies. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(6):308–310. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-0284-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):1–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asadi-Pooya AA, Simani L. Central nervous system manifestations of COVID-19: A systematic review. J Neurol Sci. 2020;413:116832. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, et al. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Olama M, Rashid A, Garozzo D. COVID-19-associated meningoencephalitis complicated with intracranial hemorrhage: a case report. Acta Neurochir. 2020;162(7):1495–1499. doi: 10.1007/s00701-020-04402-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Columbia University Kidney Transplant Program Early Description of Coronavirus 2019 Disease in Kidney Transplant Recipients in New York. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(6):1150–1156. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020030375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fishman JA. The immunocompromised transplant recipient and SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(6):1147–1149. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020040416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, et al. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97(5):829–838. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kronbichler A, Gauckler P, Windpessl M, et al. COVID-19: implications for immunosuppression in kidney disease and transplantation. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(7):365–367. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-0305-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu J, Gong E, Zhang BO, et al. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Exp Med. 2005;202(3):415–424. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.