Abstract

DNA-based immunization of mice by Plasmodium falciparum liver-stage antigen 3 (PfLSA3), a novel highly conserved P. falciparum preerythrocytic antigen, was evaluated. Animals developed a dominant Th1 immune response (high gamma interferon T-cell responses and predominance of immunoglobulin G2a) to each of three recombinant proteins spanning the molecule. We have exploited the immunological cross-reactivity of PfLSA3 with its putative homologue on sporozoites of the rodent parasite Plasmodium yoelii, and we show for the first time that responses induced by PfLSA3 in mice significantly protect against a heterologous challenge by P. yoelii sporozoites. These results support a significant effect of DNA-induced immune responses on preerythrocytic stages.

To date, the only means of inducing strong, sterile protection against preerythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum in humans has been through repeated immunizations with nonlethally irradiated sporozoites (4). Therefore, efforts have focused on the identification of subunit vaccines able to induce similar protection. Two important limitations of the vaccine candidates proposed to date are their substantial polymorphism within immunologically important regions and their suboptimal immunogenicity. We previously identified several vaccine candidates which might overcome these limitations. P. falciparum liver-stage antigen 3 (PfLSA3) is the first preerythrocytic antigen selected by screening based on differences in the immune response between protected and nonprotected volunteers immunized with irradiated sporozoites. PfLSA3 is a 200-kDa protein, expressed in both sporozoite and liver stages, and is highly conserved among parasites from various geographical regions (70 isolates have been tested so far). PfLSA3 displays promising antigenic, immunogenic, and protective properties in Aotus monkeys (11) and chimpanzees (1–3). Cross-reactivity was observed at the immunological level with Plasmodium yoelii but not with P. berghei, which suggests the existence of an as yet uncharacterized homologous antigen in the rodent parasite P. yoelii (K. Brahimi et al., unpublished data).

In this study, we set out to assess the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a DNA vaccine encoding PfLSA3 in mice. Immunization with antigen-encoding plasmid DNAs offers a number of advantages over classical immunization strategies and has been used to induce immune responses to infectious diseases in several animal models (9). The fact that strong T-cell responses are often elicited indicates that DNA constructs might be very suitable for vaccination against malaria preerythrocytic stages (4). We show here that PfLSA3 DNA immunization induces potent Th1 responses with protective properties and confers protection against heterologous P. yoelii challenge in mice. This confirms the interest shown in PfLSA3 as a DNA vaccine candidate.

Plasmids.

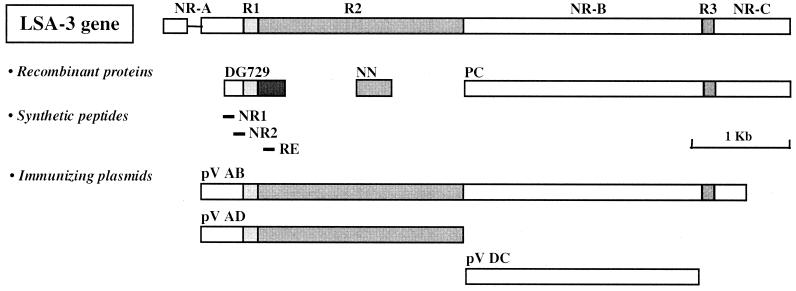

The PfLSA3 plasmid pVR2555, referred to as pV AB, was constructed by cloning a PCR fragment corresponding to the nearly full-length LSA3 gene (spanning over 3,920 bp) from P. falciparum clone 3D7 in plasmid pVR1020, licensed by Vical. Construct pV AD corresponds to the N-terminal half of the gene (1,930 bp spanning the nonrepeat region NR-A and the repeat regions R1 and R2), whereas construct pV DC corresponds to the nonrepeat region NR-B (2,145 bp) of the LSA3 gene (Fig. 1). Supercoiled plasmids were produced in Escherichia coli and purified with EndoFree Plasmid Giga kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The endotoxin concentration was between 5 and 50 EU/mg of DNA, as determined by the Limulus amebocyte lysate test (BioWhittaker).

FIG. 1.

Location in the lsa3 gene of the various peptide and DNA sequences used in this study. R1, R2, and R3 represent repeat regions, and NR-A, NR-B, and NR-C represent nonrepeat regions. DG729, NN, and PC sequences were expressed as either GST-fused or His-tagged recombinant proteins (see Materials and Methods).

Antigens.

The PfLSA3 recombinant proteins NN (LSA3-NN) and PC (LSA3-PC) were produced as glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins in the pGEX vector as previously described (3). The recombinant 729-H protein corresponds to the previously reported DG729 sequence (3) produced as a histidine (His)-tailed fusion protein using the plasmid pTcr His as recommended by the manufacturer (BioWhittaker) (Fig. 1) (3).

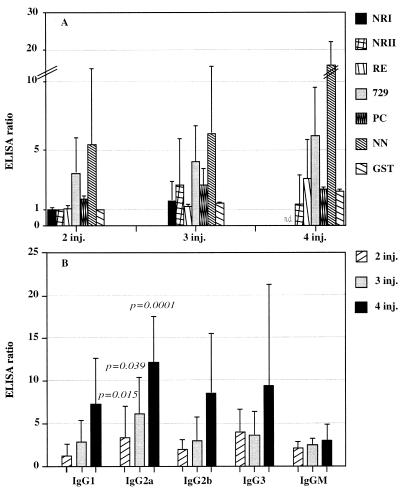

Two groups of 18 BALB/c and C3H mice (7- to 10-week-old female mice purchased from CERJ, Le Genest St. Isle, France) were immunized three times with 100 μg of pV AB intramuscularly (i.m.) at 3-week intervals (each time, the dose was equally distributed between the two tibialis anterior muscles). Sera were collected 3 weeks after each injection and tested against each of the three recombinant proteins using a standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) procedure (1). Antibodies became detectable after two injections both in BALB/c mice (Fig. 2) and in C3H mice (data not shown). The mean ELISA titers increased after further immunizations (Fig. 2A), and the proportion of responding mice reached 100%. Antibodies (Abs) to NRI and NRII peptides derived from the nonrepeat region of LSA3-729 (2) became detectable only after the third immunization. A high proportion of mice (94% of C3H mice and 78% of BALB/c mice) produced Abs mostly to the repeat region (i.e., LSA3-NN). Ab titers were higher to LSA3-NN and LSA3-729 than to LSA3-PC (Fig. 2). Immunofluorescent-antibody assays performed using P. yoelii and P. falciparum sporozoites showed that Abs elicited by PfLSA3 DNA immunization specifically reacted with the surface of both sporozoite species at similar levels (titers of 1:50 to 1:200). By contrast, preliminary experiments indicated that Abs elicited by protein immunization recognized the native protein better than did those obtained by DNA immunization, even after four injections of DNA (data not shown). This would be consistent with previous observations that, in contrast to protein immunization, increasing the number of DNA injections does not increase Ab avidity, suggesting little or no affinity maturation of specific Abs during the course of DNA immunization (8).

FIG. 2.

Ab responses in LSA3 DNA immune mice are directed to different regions of LSA3. (A) A group of 18 BALB/c mice were immunized i.m. with 100 μg of pV AB, and Ab responses to recombinant proteins LSA3-729, LSA-NN, and LSA-PC and to peptides in both repeat and nonrepeat regions of LSA3 were monitored after several injections. Results represent the mean ELISA ratio compared to that obtained with sera collected before immunizations. (B) 729-H-specific antibodies in BALB/c LSA3 DNA immune mice contain predominantly IgG2a. Isotypes of 729-H-specific antibodies in the same sera were analyzed by ELISA. Results represent the mean ELISA ratio compared to that in sera collected before immunizations. Reported P values are those obtained after comparative analysis of IgG1 to IgG2a at each date using Student's test.

Although DNA immunization induced Abs of all subclasses, the immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) isotype was predominant with respect to IgG1 and IgG2b in a statistically significant manner both in BALB/c (Fig. 2B) and in C3H (data not shown) immunized mice. IgG3 (particularly in C3H mice) and IgM were found at low levels. Over the course of the immunization, the level of IgG2a (an isotype promoted by Th1-like responses) increased more than that of IgG1 (an isotype facilitated by Th2-like responses) (P < 0.05), and the differences increased with the number of immunizations (Fig. 2B).

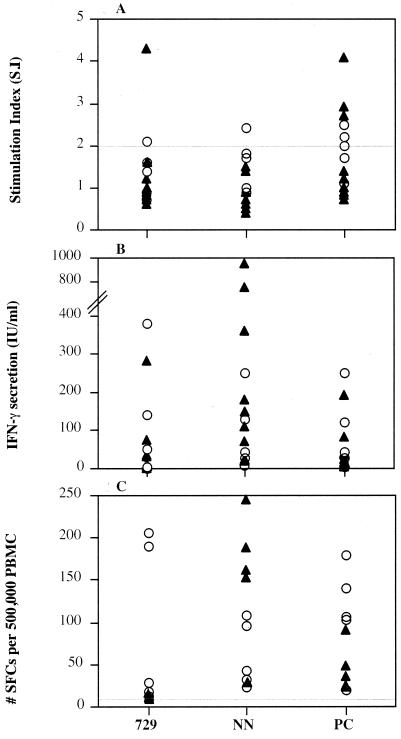

At the T-cell level, major differences were observed between proliferative and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) responses (Fig. 3). Low proliferative responses were detected in DNA-immunized BALB/c mice (six of eight mice) only after in vitro stimulation of spleen cells with recombinant protein PC (Fig. 3A). No such responses were detectable in C3H mice. Surprisingly, in both C3H and BALB/c mice, high IFN-γ secretion was consistently detected (100% of mice), both in the supernatants of stimulated cells (Fig. 3B) and by enzyme-linked immunospot assay (Fig. 3C). IFN-γ titration in supernatants from 48-h spleen cell proliferation cultures (using a pair of capture and detection rat anti-mouse IFN-γ monoclonal Abs from Becton Dickinson, San Diego, Calif.) showed high to very high levels of the cytokine in each mouse in response to at least one of the three antigens tested. The highest levels were obtained in C3H mice in response to LSA3-NN (up to 900 IU/ml). By contrast, responses elicited in BALB/c mice were lower (highest titer at 380 IU/ml) and directed to all regions of the protein. These results were further confirmed using the sensitive ELISPOT assay with fresh, unstimulated spleen cells incubated with each of the three LSA3 recombinant proteins for 40 h. Activated cells were found in all mice tested, and a high frequency was found in C3H mice in response to NN (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

T-lymphocyte responses in DNA LSA3-immunized mice. C3H and BALB/c mice were injected three times i.m. with 100 μg of pV AB DNA construct. At 1 month after the last injection, their spleens were removed and T-cell responses to selected regions of LSA3 were studied. Results of lymphoproliferation (A), IFN-γ titration in supernatants (B), and ELISPOT assays for IFN-γ (C) of eight individually tested C3H (▴) and BALB/c (○) mice are represented. Unstimulated cells did not produce detectable amounts of IFN-γ. The mean values obtained in wells with GST alone as negative control were as follows: stimulation index (S.I.), 0.99 ± 0.23; IFN-γ, 1.31 ± 1.49; and ELISPOT, 21 ± 18.4 (BALB/c mice); and S.I., 0.6 ± 0.17; IFN-γ, 13.9 ± 10.1; and ELISPOT, 5.6 ± 2.6 (C3H mice). SFC, spot-forming cell; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

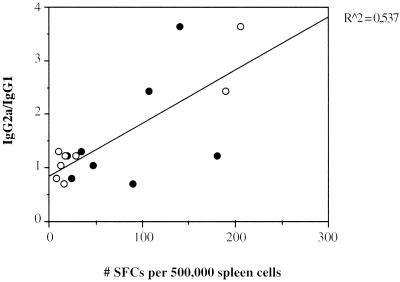

The results obtained by DNA immunization contrast with those previously obtained using LSA3 recombinant proteins with various adjuvants or by lipopeptide immunization (reference 1 and our unpublished observations). Indeed, C3H mice immunized with peptides or proteins showed consistent proliferative responses, which was not the case for those given DNA immunizations. When recombinant proteins were used, the highest proliferative responses and IFN-γ were directed mainly against LSA3-PC and infrequently against LSA3-NN or LSA3-729, whereas DNA-induced responses were restricted to the repeat region NN. Similarly, protein-based immunization induced Ab responses mainly to PC rather than to NN, which was the main target of DNA-induced Ab responses. It is noteworthy that naturally acquired Abs to LSA3 in malaria-exposed individuals have a pattern of recognition of LSA3 similar to that of Abs in DNA-immunized mice (B. L. Perlaza, J. P. Sauzet, A. Toure-Balde, K. Brahini, P. Daubersies, G. P. Corradin, and P. Druilhe, submitted for publication). This similarity might be the result of a correctly folded NN region by in vivo DNA-transfected cells. Finally, protein immunization generated a rapid and equally distributed isotype profile, suggesting a mixed Th1-Th2 pattern of response. In contrast, our results indicate the ability of LSA3 DNA immunization to channel mouse responses toward epitopes preferentially recognized by humans. The response generated is directed toward a Th1-biased type of immune response, as supported by the fact that the IgG2a/IgG1 ratio and the frequency of LSA3-specific peripheral IFN-γ-secreting T cells evolved in parallel (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Correlation between the IgG2a/IgG1 ratio and the frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells in LSA3 DNA-immunized mice. The IgG2a/IgG1 ratio was found to be correlated with the frequency of IFN-γ-producing spleen cells specific for LSA3-729 (●) and LSA3-PC (○) determined by an ELISPOT assay in both BALB/c and C3H mice immunized with LSA3 DNA. SFC, spot-forming cell.

IFN-γ secretion in response to DNA immunization was found to be high, and this cytokine has been proposed to be a major effector of defense mechanisms against the liver stages of the parasite (5, 6, 10, 12).

To study the protective capacities of the PfLSA3 DNA vaccine formulation, we exploited the interspecies B- and T-cell cross-reactivity of LSA3-specific immune responses between P. falciparum and P. yoelii (Brahimi et al., unpublished). Mice immunized with four injections of pV AB were challenged by intravenous inoculation with 150 P. yoelii sporozoites (clone 1.1, derived from the 17XNL strain), dissected from infected salivary glands. All five C3H mice and five of seven BALB/c mice (71%) were protected against sporozoite challenge (Table 1). Protection was defined either as the complete absence of blood-stage parasitemia from days 4 to 14 postchallenge (two of five C3H mice [40%] and one of seven BALB/c mice [14%]) or as a delayed onset of parasitemia compared to control groups. In the latter case, the influence of the parasite load in the liver on the subsequent course of blood-stage parasitemia has been estimated in naive mice as a function of the size of the sporozoite inoculum; hence, a 1-, 2-, or 3-day-delayed onset of parasitemia would represent an 80, 96, and 99.2% reduction in parasite burden, respectively (Table 2). Of seven LSA3 DNA immune BALB/c mice, four (57%) achieved such partial protection, with three mice being delayed by 2 days and one mouse being delayed by 1 day. Similarly, three of five C3H mice (60%) were partially protected, with one mouse even having a 3-day delay and the two others having a 1-day delay. In contrast, the onset of blood parasitemia in all eight nonimmunized control mice, as in all eight mice immunized with control DNA (influenza virus gene cloned in the same Vical vector), always occurred on the same day (day 4 postchallenge) in parallel experiments and with the same sporozoite preparation (Table 1). Taken together, our results indicate that PfLSA3 DNA-based immunization induces a significant, although not always complete, protective effect on parasite preerythrocytic development.

TABLE 1.

Protective status induced in mice by LSA3 DNA vaccinationa

| Mouse strain | Construct | Protection (no. of mice protected/total no.)

|

Protection rate (no. protected/total no.) (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Partial (delayed parasitemia)

|

|||||

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | ||||

| C3H | pV AB | 2/5 | 2/5 | 0/5 | 1/5 | 5/5 (100) |

| C3H | pV AD | 1/3 | 1/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 2/3 (67) |

| C3H | pV DC | 0/3 | 3/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 3/3 (100) |

| BALB/c | pV AB | 1/7 | 1/7 | 3/7 | 0/7 | 5/7 (71) |

| BALB/c | None | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/8 (0) |

| BALB/c | Vical-Flu | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/8 (0) |

Mice were inoculated four times i.m. with 100 μg of pV AB. At 3 weeks after the last injection, they were challenged with 150 P. yoelii (clone 1.1) sporozoites injected intravenously. Blood-stage parasitemia was observed from days 4 to 14 after the challenge. Total protection was defined as the absence of parasitemia, and partial protection was defined as a significant delay (1, 2, or 3 days) in the onset of parasitemia compared to controls, either naive nonimmunized mice or Vical DNA-Flu-immunized BALB/c mice (or C3H mice [data not shown]). Shown are results for control mice challenged with the same sporozoite batch as LSA3 DNA-immunized mice. The same reproducibility in patency (no delay of parasitemia) was obtained in ca. 100 control mice in other experiments (not shown).

TABLE 2.

Influence of parasite load in the liver on the subsequent course of blood-stage parasitemia estimated in naive mice as a function of the size of the sporozoite inoculuma

| No. of sporozoites | % Reduction | Delay in onset of parasitemia (h) |

|---|---|---|

| 15,000 | 0 | |

| 3,000 | 80 | 24 |

| 600 | 96 | 48 |

| 125 | 99.2 | 72 |

Results of a representative experiment with two naive BALB/c mice, infected with 125, 600, 3,000, or 15,000 P. yoelii sporozoites (clone 1.1), are shown. Parasitemia in each mouse was observed daily from days 1 to 13. Compared to the normal day 3 appearance of blood stages in mice infected with the highest dose, a 1-, 2-, or 3-day-delayed onset of parasitemia corresponded to 80, 96, and 99.2% reduction in parasite burden, respectively. Similar data were recorded in other independent experiments.

To try to identify the regions of PfLSA3 responsible for the induced protection against P. yoelii, C3H mice were immunized with DNA constructs encoding either the N-terminal (pV AD) or C-terminal (pV DC) region of the protein. As shown in Fig. 4, pV AD induced protection in two of three mice, with one of them being totally protected. It is noteworthy that pV AD encodes the LSA3-729 region, which contains several B- and T-cell epitopes with protective potential in chimpanzees (2). The three mice immunized with pV DC were partially protected, since parasitemia was only delayed in all three. It is unclear whether one or both regions are important for full protection.

The results described in this report show that a naked DNA encoding the PfLSA3 antigen is strongly immunogenic in mice, inducing both B- and T-cell responses to different subregions of the molecule. Furthermore, these responses translate into a biological effect. These results compare favorably with DNA vaccination against a wide range of infectious diseases (9), including mice immunized by a plasmid DNA encoding the P. yoelii circumsporozoite protein (7). The fact that the highest levels of protection were achieved in C3H mice might be related to the ability of this mouse strain to secrete high IFN-γ levels in response to the repeat region of LSA3. Although total protection was not obtained in all the mice, it must be noted that protection was obtained in a very demanding heterologous system, where the immunogen and challenge sporozoites are from different Plasmodium species. This differs from other immunization experiments such as those with circumsporozoite protein, where protection was demonstrated against homologous species and homologous strain challenge. Finally, the variability in protection in individual mice might be related to the surprisingly large variations in the levels of immune responses found among inbred mice.

The selection of LSA3 as a new P. falciparum liver-stage molecular target is based on a strong rationale; antigenicity studies in humans, immunogenicity data in mice and non-human primates, and sequence conservation have further increased the interest in this molecule. The present results obtained by genetic immunization lend further support to its vaccine potential.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by European Commission Inco-DC grant 98-0387 and WHO-Tdr grant 940023.

We thank Aventis-Pasteur for assistance and encouragement and for the gift of the control plasmid used in these experiments, Georges Snounou for critical review of the manuscript, and Nicolas Puchot for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.BenMohamed L, Gras-Masse H, Tartar A, Daubersies P, Brahimi K, Bossus M, Thomas A, Druilhe P. Lipopeptide immunization without adjuvant induces potent and long-lasting B, T helper, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses against a malaria liver stage antigen in mice and chimpanzees. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1242–1253. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.BenMohamed L, Thomas A, Bossus M, Brahimi K, Wubben J, Gras-Masse H, Druilhe P. High immunogenicity in chimpanzees of peptides and lipopeptides derived from four new plasmodium falciparum pre-erythrocytic molecules. Vaccine. 2000;18:2843–2855. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daubersies P, Thomas A W, Millet P, Brahimi K, Langermans J A M, Ollomo B, BenMohamed L, Slierendregt B, Eling W, Guérin-Marchand C, Van Belkum A, Dubreuil G, Meis J F G M, Cayphas S, Cohen J, Gras-Masse H, Druilhe P. Protection against P. falciparum malaria in chimpanzees by immunization with a conserved pre-erythrocytic antigen, LSA3. Nat Med. 2000;6:1258–1263. doi: 10.1038/81366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Druilhe P L, Renia L, Fidock D A. Immunity to liver stages. In: Sherman I W, editor. Malaria: parasite biology, pathogenesis, and protection. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1998. pp. 513–543. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreira A, Schofield L, Enea V, Schellekens H, van der Meide P, Collins W E, Nussenzweig R S, Nussenzweig V. Inhibition of development of exoerythrocytic forms of malaria parasites by gamma-interferon. Science. 1986;232:881–884. doi: 10.1126/science.3085218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman S L, Crutcher J M, Puri S K, Ansari A A, Villinger F, Franke E D, Singh P P, Finkelman F, Gately M K, Dutta G P, Sedegah M. Sterile protection of monkeys against malaria after administration of interleukin-12. Nat Med. 1997;3:80–83. doi: 10.1038/nm0197-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman S L, Sedegah M, Hedstrom R C. Protection against malaria by immunization with a Plasmodium yoelii circumsporozoite protein nucleic acid vaccine. Vaccine. 1994;12:1529–1533. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang Y, Calvo P A, Daly T M, Long C A. Comparison of humoral immune responses elicited by DNA and protein vaccines based on merozoite surface protein-1 from Plasmodium yoelii, a rodent malaria parasite. J Immunol. 1998;161:4211–4219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai W C, Bennett M. DNA vaccines. Crit Rev Immunol. 1998;18:449–484. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v18.i5.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maheshwari R K, Czarniecki C W, Dutta G P, Puri S K, Dhawan B N, Friedman R M. Recombinant human gamma interferon inhibits simian malaria. Infect Immun. 1986;53:628–630. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.3.628-630.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perlaza B L, Arevalo-Herrera M, Brahimi K, Quintero G, Palomino J C, Gras-Masse H, Tartar A, Druilhe P, Herrera S. Immunogenicity of four Plasmodium falciparum preerythrocytic antigens in Aotus lemurinus monkeys. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3423–3428. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3423-3428.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sedegah M, Finkelman F, Hoffman S L. Interleukin 12 induction of interferon gamma-dependent protection against malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10700–10702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]