Abstract

Objective

Serum inflammatory biomarkers play crucial roles in the development of acute ischemic stroke (AIS). In this study, we explored the association between inflammatory biomarkers including platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), and clinical outcomes in AIS patients who achieved successful recanalization.

Methods

Patients with AIS who underwent endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) and achieved a modified thrombolysis in the cerebral infarction scale of 2b or 3 were screened from a prospective cohort at our institution between January 2013 and June 2021. Data on blood parameters and other baseline characteristics were collected. The functional outcome was an unfavorable outcome defined by a modified Rankin Scale of 3–6 at the 3-month follow up. Other clinical outcomes included symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH) and 3-month mortality. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the effects of PLR, NLR, and MLR on clinical outcomes.

Results

A total of 796 patients were enrolled, of which 89 (11.2%) developed sICH, 465 (58.4%) had unfavorable outcomes at 3 months, and 168 (12.1%) died at the 3-month follow up. After adjusting for confounding variables, a higher NLR (OR, 1.076; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.037–1.117; p < 0.001) and PLR (OR, 1.001; 95%CI, 1.000–1.003; p = 0.045) were significantly associated with unfavorable outcomes, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of NLR and PLR was 0.622 and 0.564, respectively. However, NLR, PLR, and MLR were not independently associated with sICH and 3-month mortality (all adjusted p > 0.05).

Conclusion

Overall, our results indicate that higher PLR and NLR were independently associated with unfavorable functional outcomes in AIS patients with successful recanalization after EVT; however, the underlying mechanisms are yet to be elucidated.

Keywords: acute ischemic stroke, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio, endovascular thrombectomy

Background

Previous randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) secondary to large vessel occlusion could benefit from reperfusion therapy with endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) (1, 2). However, approximately half of patients who achieve successful recanalization of the occluded artery post-EVT have unfavorable outcomes at 90 days (3–5). The mechanisms underlying the mismatch of successful recanalization and good outcomes remain unclear (6).

The neuroinflammatory response has been increasingly recognized to be important in the pathophysiology of AIS (7). Activation of leukocytes, platelets, or other pro-inflammatory mediators plays a vital role in AIS neurological prognoses. The potential novel biomarkers of inflammation, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), have recently been proposed as critical predictors of unfavorable outcomes in patients with AIS (8, 9). It has been found that NLR and PLR in AIS patients with a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) ≥6 were significantly higher than in patients with a NIHSS <6, indicating the severity of stroke was related to the value of NLR and PLR (10). In addition, higher NLR and MLR have been found to be positively correlated with stroke severity, adverse complications, and death (11, 12), while higher PLR predicted unfavorable functional outcomes with a higher modified Rankin Scale (mRS) and NIHSS scores (13). However, few studies support the predictive value of NLR, PLR, and MLR on clinical outcomes in AIS patients with successful recanalization (14). In this study we aimed to explore the association of PLR, NLR, and MLR with clinical outcomes in patients with AIS who underwent EVT and achieved successful recanalization.

Methods

Study design

Data for this study were obtained from a prospective cohort of consecutive patients with AIS who underwent EVT at our hospital between January 2013 and June 2021. Information on the prospective cohort, EVT procedure for AIS, and imaging evaluations have been described previously (15). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xuanwu Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legally authorized representatives.

Study population

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) age ≥18 years, (2) treatment with EVT within 24 h and successful recanalization, defined as a modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction (mTICI) of 2b or 3. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) pre-stroke mRS > 2, (2) absence of blood parameters before EVT, and (3) lack of 3-month follow-up.

Data collection

Variables including demographics, vascular risk factors, baseline clinical assessment (admission systolic blood pressure [SBP], diastolic blood pressure [DBP], NIHSS, Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score [ASPECTS], or posterior circulation Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score [pc-ASPECTS]), laboratory tests (fasting blood glucose [FBG], NLR, PLR, MLR), lesion location, stroke etiology, treatment (general anesthesia, time interval from symptom onset to puncture [OTP], time interval from symptom onset to recanalization [OTR], intravenous thrombolysis [IVT]), intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH), and clinical outcomes at 3 months were collected from the database and analyzed.

Assessment of NLR, PLR, and MLR

Blood samples were collected within 10 min of arrival at the hospital. Parameters including neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelets were analyzed using an automated blood cell counter (MEK-722K, NIHON, KOHEN, JAPAN). The NLR, PLR, and MLR were calculated by dividing the number of neutrophils, platelets, and monocytes by the number of lymphocytes.

Assessment of clinical outcomes

The functional outcome was an unfavorable outcome at 3 months defined as an mRS of 3–6 (16). Other clinical outcomes were sICH and mortality at the 3-month follow up. The sICH was diagnosed according to the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III (17) as ICH associated with any of the following conditions: (1) NIHSS score increased >4 points; (2) clinical deterioration determined by investigators, or adverse events including drowsiness and increase of hemiparesis (18, 19).

Statistical analyses

All enrolled patients were divided into favorable and unfavorable outcome groups according to their 3 months mRS score as previously described. Differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups were analyzed. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR). Analysis was performed using the t-test for independent samples or the Mann-Whitney U-test, respectively. Categorical variables were described as numbers (percentages) and analyzed using the chi-square test. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to explore the effect of NLR, PLR, and MLR on 3-month functional outcomes, adjusting for age, sex, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, admission DBP, NIHSS, ASPECTS, FBG, lesion location, general anesthesia, and sICH. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to test the discriminative ability of the NLR, MLR, and PLR for 3-month functional outcomes. In addition, the association between NLR, MLR, PLR, and sICH as well as mortality at 3 months was also analyzed.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (version.26; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was indicated by p < 0.05.

Results

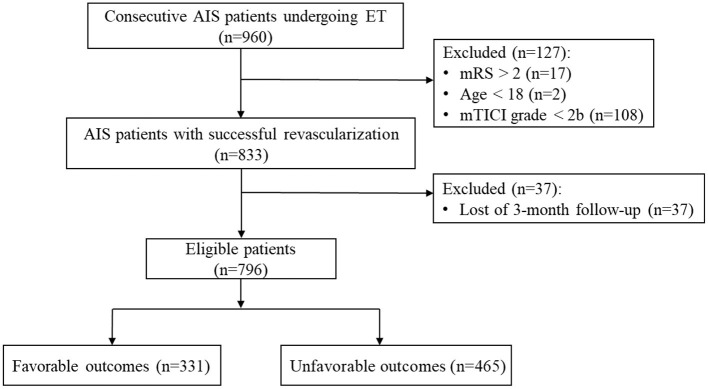

A total of 960 patients with AIS who underwent EVT were screened, and 796 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included in the study (Figure 1). The mean age of the patients was 62.89 ± 12.22 years, and 566 (71.1%) were male. The median baseline NIHSS and ASPECTS/pc-ASPECTS scores were 16 and 9, respectively. Large-vessel occlusion in the anterior circulation was observed in 568 patients (71.4 %). A total of 270 patients (33.9%) underwent IVT before EVT. The median OTP and OTR were 380 and 458 min, respectively. sICH occurred in 89 (11.2%) patients. During the follow-up at 3 months, 465 (58.4%) patients had unfavorable functional outcomes and 168 (12.1%) patients died.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. AIS, acute ischemic stroke; EVT, endovascular thrombectomy; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; mTICI, modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction.

Univariate analyses of patients with favorable and unfavorable outcomes

A comparison of the detailed characteristics of the patients with favorable and unfavorable outcomes is shown in Table 1. In the univariable analysis, patients with unfavorable outcomes were much older (65.07 ± 11.93 vs. 59.83 ± 11.98, p < 0.001), had higher proportions of diabetes (34.0 vs. 21.1%, p < 0.001), hyperlipidemia (69.5 vs. 42.0%, p < 0.001), previous stroke (29.5 vs. 20.2%, p = 0.003), posterior circulation lesion (32.9 vs. 22.7%, p = 0.002), general anesthesia (42.2 vs. 29.9%, p < 0.001), ICH (44.1 vs. 22.7%, p < 0.001), and sICH (17.8 vs. 1.8%, p < 0.001). However, there was a lower proportion of current smokers (35.7 vs. 45.6%, p = 0.005).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with favorable and unfavorable outcomes.

| Factors |

Total number

(n = 796) |

Favorable outcomes

(n = 331) |

Unfavorable outcomes

(n = 465) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 62.89 ± 12.22 | 59.83 ± 11.98 | 65.07 ± 11.93 | <0.001* |

| Male, n (%) | 566 (71.1%) | 256 (77.3%) | 310 (66.7%) | <0.001* |

| Vascular risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 558 (70.1%) | 220 (66.5%) | 338 (72.7%) | 0.059 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 228 (28.6%) | 70 (21.1%) | 158 (34.0%) | <0.001* |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 462 (58.0%) | 139 (42.0%) | 323 (69.5%) | <0.001* |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 317 (39.8%) | 151 (45.6%) | 166 (35.7%) | 0.005* |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 259 (32.5%) | 95 (28.7%) | 164 (35.3%) | 0.051 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 204 (25.6%) | 67 (20.2%) | 137 (29.5%) | 0.003* |

| Baseline clinical assessment | ||||

| Admission SBP (mmHg), mean ± SD | 146 ± 33 | 143.55 ± 22.58 | 150.67 ± 24.15 | <0.001* |

| Admission DBP (mmHg), mean ± SD | 83 ± 15 | 83.03 ± 14.43 | 85.27 ± 14.79 | 0.033* |

| Admission NIHSS, median (IQR) | 16 (12–21) | 13 (10–17) | 18 (14–26) | <0.001* |

| Admission ASPECTS/pc-ASPECTS, median (IQR) | 9 (7–10) | 9 (8–10) | 8 (7–10) | 0.006* |

| Laboratory test | ||||

| FBG (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 7.37 (6.15–9.49) | 6.89 (5.71–8.25) | 7.96 (6.56–10.48) | <0.001* |

| NLR, median (IQR) | 5.87 (3.39–9.82) | 4.85 (2.79–7.76) | 6.57 (4.00–11.21) | <0.001* |

| PLR, median (IQR) | 161.79 (108.46–241.67) | 153.90 (105.04–218.23) | 168.89 (114.38–254.48) | 0.002* |

| MLR, median (IQR) | 0.30 (0.22–0.42) | 0.28 (0.21–0.37) | 0.32 (0.22–0.47) | <0.001* |

| Lesion location | 0.002* | |||

| Anterior circulation, n (%) | 568 (71.4%) | 256 (77.3%) | 312 (67.1%) | |

| Posterior circulation, n (%) | 228 (28.6%) | 75 (22.7%) | 153 (32.9%) | |

| Stroke etiology | ||||

| LAA, n (%) | 479 (60.2%) | 210 (63.4%) | 269 (57.8%) | 0.088 |

| CE, n (%) | 281 (35.3%) | 103 (31.1%) | 178 (38.3%) | |

| Others, n (%) | 36 (4.5%) | 18 (5.4%) | 18 (3.9%) | |

| Treatment | ||||

| General anesthesia, n (%) | 295 (37.1%) | 99 (29.9%) | 196 (42.2%) | <0.001* |

| OTP (min), median (IQR) | 380 (284–528) | 389 (286–540) | 375 (282–520) | 0.775 |

| OTR (min), median (IQR) | 458 (358–600) | 450 (360–597) | 465 (353–602) | 0.507 |

| IVT, n (%) | 270 (33.9%) | 112 (33.8%) | 158 (34.0%) | 0.967 |

| Clinical outcomes | ||||

| ICH, n (%) | 280 (35.2%) | 75 (22.7%) | 205 (44.1%) | <0.001* |

| sICH, n (%) | 89 (11.2%) | 6 (1.8%) | 83 (17.8%) | <0.001* |

P < 0.05. SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; NIHSS, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; ASPECTS, Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score; pc-ASPECTS, posterior circulation Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score; FBG, fast blood glucose; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; MLR, monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio; LAA, large artery atherosclerosis; CE, cardio embolism; OTP, time interval from symptoms onset to puncture; OTR, time interval from symptoms onset to recanalization; IVT, intravenous thrombolysis; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; sICH, symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage.

The results showed that men were more likely to favorable outcomes (77.3 vs. 66.7%, p < 0.001). In addition, patients with unfavorable outcomes also had higher baseline SBP (150.67 ± 24.15 vs. 143.55 ± 22.58 mmHg, p < 0.001), higher DBP (85.27 ± 14.79 vs. 83.03 ± 14.43 mmHg, p = 0.033), higher NIHSS score (median, 18 vs. 13, p < 0.001), lower ASPECTS/pc-ASPECTS score (median, 8 vs. 9, p = 0.006). For laboratory tests, patients in the unfavorable outcome group had higher FBG (median, 7.96 vs. 6.89 mmol/L, p < 0.001), NLR (median, 6.57 vs. 4.85, p < 0.001), PLR (median, 168.89 vs. 153.90, p = 0.002), and MLR (median, 0.32 vs. 0.28, p < 0.001).

Effect of NLR, PLR, and MLR on 3-month functional outcomes

After adjusting for potential confounders (age, sex, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, admission DBP, NIHSS, ASPECTS, FBG, lesion location, general anesthesia, and sICH), NLR (OR, 1.076; 95% CI, 1.037–1.117; p < 0.001), and PLR (OR, 1.001; 95% CI, 1.000–1.003; p = 0.045) were found as independent predictors of unfavorable outcomes. Nevertheless, MLR was not significantly associated with unfavorable outcomes (OR, 1.052; 95% CI, 0.954–2.365; p = 0.079) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable analysis of NLR, PLR, MLR in predicting clinical outcomes.

| Variable | β | SE | Adjusted OR | Adjusted 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfavorable outcomes at 3 months | ||||||

| NLR@ | 0.074 | 0.019 | 1.076 | 1.037 | 1.117 | < 0.001* |

| PLR@ | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.001 | 1.000 | 1.003 | 0.045* |

| MLR@ | 0.407 | 0.232 | 1.502 | 0.954 | 2.365 | 0.079 |

| sICH | ||||||

| NLR& | 0.010 | 0.015 | 1.010 | 0.980 | 1.042 | 0.500 |

| PLR& | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 1.001 | 0.601 |

| MLR& | 0.057 | 0.265 | 1.059 | 0.630 | 1.778 | 0.830 |

| Mortality at 3 months | ||||||

| NLR@ | 0.022 | 0.013 | 1.023 | 0.997 | 1.049 | 0.082 |

| PLR@ | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.001 | 1.000 | 1.002 | 0.268 |

| MLR@ | 0.193 | 0.183 | 1.213 | 0.847 | 1.737 | 0.292 |

P < 0.05.

Adjusting for age, sex, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, admission DBP, NIHSS, ASPECTS/pc-ASPECTS, FBG, lesion location, general anesthesia, and sICH.

Adjusting for age, admission SBP, FBG, lesion site, TOAST, and IVT.

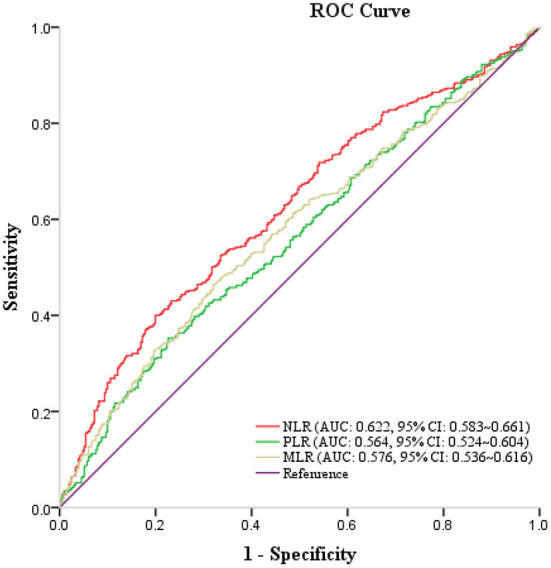

The areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC) of NLR, PLR, and MLR were 0.622 (95% CI, 0.583–0.661; p < 0.001), 0.564 (95% CI, 0.524–0.604; p = 0.002), and 0.576 (95% CI, 0.536–0.616; p < 0.001), respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of NLR, PLR, MLR in predicting unfavorable outcomes at 3 months.

Effect of NLR, PLR, and MLR on sICH and 3-month mortality

We also analyzed the relationship between NLR, PLR, MLR, and sICH as well as 3-month mortality. After adjusting for potential confounders, NLR, PLR, and MLR was neither significantly associated with sICH [NLR (OR: 1.010, 95% CI: 0.980–1.042, p = 0.500), PLR (OR: 1.000, 95% CI: 0.998–1.001, p = 0.601), MLR (OR: 1.059, 95% CI: 0.630–1.778, p = 0.830)] nor mortality at 3 months [NLR (OR: 1.023, 95% CI: 0.997–1.049, p = 0.082), PLR (OR: 1.001, 95% CI: 1.000–1.002, p = 0.268), MLR (OR: 1.213, 95% CI: 0.847–1.737, p = 0.292)].

Discussion

In this study, we found that approximately half (58.4%) of the patients with successful recanalization still had unfavorable outcomes at follow-up after 3 months. Moreover, higher NLR and PLR before EVT were significantly associated with unfavorable functional outcomes in patients with AIS who achieved successful recanalization after EVT.

Currently, EVT is recognized as the most effective reperfusion therapy for the treatment of AIS secondary to the occlusion of large vessels (20). Despite EVT yielding a successful recanalization rate of >80% compared with traditional therapies, around half of the patients who achieved successful recanalization still suffer from unfavorable functional outcomes (3), as was observed in this study. Possible causes include subsequent secondary brain injury from cerebral edema (CED), hemorrhagic transformation, and infarct growth due to impaired microvascular reperfusion mediating early neurological deterioration and 3-month unfavorable functional outcomes (21, 22). The inflammatory response plays an essential role in the pathophysiology and predicting the prognosis of ischemia or hemorrhagic stroke (23, 24). In acute ischemic stroke, the inflammatory response may worsen the CED, ICH, and delay cerebral ischemia thereby leading to poor prognosis (8, 9, 21).

In this study, we found that NLR and PLR before EVT were significantly associated with unfavorable functional outcomes in patients with AIS after successful recanalization with EVT. Firstly, to determine whether these inflammatory indexes increased the prognosis of poor function by increasing sICH, we analyzed the relationship between PLR, NLR, MLR, and sICH. However, no significant association between inflammatory indexes and sICH was found. Secondly, recent imaging studies have shown that the no-reflow phenomenon, which indicates incomplete microvascular reperfusion of the tissue despite successful macrovascular revascularization, provides insights into the underlying mechanisms of this unfavorable prognosis of successfully recanalized stroke (25). However, advanced perfusion imaging for the evaluation of microvascular tissue reperfusion is too time-consuming for timely treatment, thus difficult to implement in the clinic. In patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention, composite inflammatory biomarkers have been shown to be strong predictors of both the no-reflow phenomenon and unfavorable functional outcomes (26). We hypothesized that NLR, PLR, and MLR may mediate neurological outcomes through microvascular no-reflow mechanism in patients with AIS treated with EVT. Theoretically, ischemic brain tissues can release various cytokines and chemokines to guide the proliferation and migration of peripheral leukocytes (27). Elevated levels of peripheral leukocytes transmigrating and infiltrating to the ischemic tissues may cause thrombosis, aggravate endothelial edema, and lead to microvascular occlusion, thereby participating in the microvascular no-reflow phenomenon (25). Therefore, composite inflammation indexes such as NLR, PLR, and MLR, are easy-to-acquire biomarkers, which mayserve as potential predictors of the no-reflow phenomenon, and could be associated with unfavorable functional outcomes in successfully recanalized patients with AIS (28, 29). In the present study, NLR and PLR were found to be independently correlated with functional outcome; however, MLR was not significantly associated with functional outcome. Further investigations are needed to explore the relationship between inflammatory indices, the no-reflow phenomenon, and functional outcomes in human ischemic stroke.

In addition, inflammatory biomarkers have been found to predict functional outcomes in patients with intracerebral (23) and subarachnoid hemorrhage (24). Therefore, in either ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, inflammatory biomarkers may share common mechanisms in mediating secondary brain injury following acute vascular events. Moreover, anti-inflammatory therapy targeting their common pathways may help improve the neurological prognosis of patients with acute stroke (27).

This study had some limitations. Firstly, the cohort included subjects from only one region of China, which would have introduced selection bias. Therefore, further exploration using larger multicenter prospective studies is warranted to substantiate our findings. Second, covariates related to AIS could not be completely collected due to data limitations. Thirdly, the area under the ROC curve values of NLR, PLR, and MLR for outcome prediction were relatively low and need further exploration. Finally, only preoperative inflammatory indicators were evaluated without post-operative indicators; therefore, post-operative inflammatory indicators will need to be evaluated in future studies.

Conclusion

This study showed that NLR and PLR before EVT were significantly associated with 3-month functional outcomes in patients with AIS who achieved successful recanalization after EVT. Further studies are needed to confirm these results and explore the underlying mechanisms.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Xuanwu Hospital. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the patient/participants or patient/participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

JM and WG conceived of the study idea, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. JX, LW, and WZ participated in the data collection and analysis. XJ, SL, CR, CW, CL, JC, JD, QM, and HS participated in the coordination of the study. WZ and XJ helped to interpret the data and modify the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all the patients and their families in this study. We also thank Xuanwu Hospital and Capital Medical University for their support.

Abbreviations

AIS, acute ischemic stroke; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; MLR, monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio; EVT, endovascular thrombectomy; mTICI, modified thrombolysis in cerebral infarction; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; CI, confidence interval; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; NIHSS, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; ASPECTS, Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score; pc-ASPECTS, posterior circulation Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score; FBG, fasting blood glucose; LAA, large artery atherosclerosis; CE, cardio embolism; OTP, time interval from symptoms onset to puncture; OTR, time interval from symptoms onset to recanalization; IVT, intravenous thrombolysis; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; sICH, symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Funding

This research was supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (JQ22020), Beijing Nova Program (No. Z201100006820143), General Project of Science and Technology of Beijing Municipal Education Commission (No. KM202110025018), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82001257 and 82027802), and the Key Project of Science and Technology Development of China Railway Corporation (No. K2019Z005).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Zi W, Qiu Z, Li F, Sang H, Wu D, Luo W, et al. Effect of endovascular treatment alone vs intravenous alteplase plus endovascular treatment on functional independence in patients with acute ischemic stroke: the DEVT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2021) 325:234–43. 10.1161/str.52.suppl_1.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leng T, Xiong ZG. Treatment for ischemic stroke: from thrombolysis to thrombectomy and remaining challenges. Brain Circ. (2019) 5:8–11. 10.4103/bc.bc_36_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou T, Yi T, Li T, Zhu L, Li Y, Li Z, et al. Predictors of futile recanalization in patients undergoing endovascular treatment in the DIRECT-MT trial. J Neurointerv Surg. (2021). 10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-017765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lattanzi S, Norata D, Divani AA, Di Napoli M, Broggi S, Rocchi C, et al. Systemic inflammatory response index and futile recanalization in patients with ischemic stroke undergoing endovascular treatment. Brain Sci. (2021) 11:1164. 10.3390/brainsci11091164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng G, Xiao J, Yu H, Chen M, Shang K, Qin C, et al. Predictors of futile recanalization after endovascular treatment in acute ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg. (2021) 14:881–5. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-017963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitano T, Todo K, Yoshimura S, Uchida K, Yamagami H, Sakai N, et al. Futile complete recanalization: patients characteristics and its time course. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:4973. 10.1038/s41598-020-61748-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belayev L, Obenaus A, Mukherjee PK, Knott EJ, Khoutorova L, Reid MM, et al. Blocking pro-inflammatory platelet-activating factor receptors and activating cell survival pathways: a novel therapeutic strategy in experimental ischemic stroke. Brain Circ. (2020) 6:260–8. 10.4103/bc.bc_36_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lux D, Alakbarzade V, Bridge L, Clark CN, Clarke B, Zhang L, et al. The association of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and lymphocyte-monocyte ratio with 3-month clinical outcome after mechanical thrombectomy following stroke. J Neuroinflammation. (2020) 17:60. 10.1186/s12974-020-01739-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozgen E, Guzel M, Akpinar CK, Yucel M, Demir MT, Baydin A. The relationship between neutrophil/lymphocyte, monocyte/ /lymphocyte, platelet/lymphocyte ratios and clinical outcomes after ninety days in patients who were diagnosed as having acute ischemic stroke in the emergency room and underwent a mechanical thro. Bratisl Lek Listy. (2020) 121:634–9. 10.4149/BLL_2020_102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sung PH, Chen KH, Lin HS, Chu CH, Chiang JY, Yip HK. The correlation between severity of neurological impairment and left ventricular function in patients after acute ischemic stroke. J Clin Med. (2019) 8:190. 10.3390/jcm8020190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kömürcü HF, Gözke E, Ak PD, Aslan IK, Salt I, Bi ÇIÖ. Changes in neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet ratios and their relationship with NIHSS after rtPA and/or thrombectomy in ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovascular Dis. (2020) 29:105004. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng H-R, Song J-Y, Zhang Y-N, Chen Y-B, Lin G-Q, Huang G-Q, et al. High monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with stroke-associated pneumonia. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:575809. 10.3389/fneur.2020.575809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu J-H, He X-W, Li Q, Liu J-R, Zhuang M-T, Huang F-F, et al. Higher platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with worse outcomes after intravenous thrombolysis in acute ischaemic stroke. Front Neurol. (2019) 10:1192. 10.3389/fneur.2019.01192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X, Wu F, Jiang C, Feng X, Wang R, Song Z, et al. Novel peripheral blood cell ratios: Effective 3-month post-mechanical thrombectomy prognostic biomarkers for acute ischemic stroke patients. J Clin Neurosci. (2021) 89:56–64. 10.1016/j.jocn.2021.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao W, Che R, Shang S, Wu C, Li C, Wu L, et al. Low-dose tirofiban improves functional outcome in acute ischemic stroke patients treated with endovascular thrombectomy. Stroke. (2017) 48:3289–94. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.019193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ha SH, Kim BJ Ryu JC, Bae JH, Kim JS. Basilar artery tortuosity may be associated with early neurological deterioration in patients with pontine infarction. Cerebrovas Dis. (2022) 51:594–9. 10.1159/000522142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neuberger U, Möhlenbruch MA, Herweh C, Ulfert C, Bendszus M, Pfaff J. Classification of bleeding events: comparison of ECASS III (European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study) and the new Heidelberg bleeding classification. Stroke. (2017) 48:1983–5. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Xie Y, Wang H, Yang D, Jiang T, Yuan K, et al. Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage after mechanical thrombectomy in Chinese ischemic stroke patients: the ASIAN score. Stroke. (2020) 51:2690–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, von Kummer R, Davalos A, Meier D, et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second Eur Aust Acute Stroke Study Invest Lancet. (1998) 352:1245–51. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08020-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warner JJ, Harrington RA, Sacco RL, Elkind M. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. (2019) 50:3331–2. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.027708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferro D, Matias M, Neto J, Dias R, Moreira G, Petersen N, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts cerebral edema and clinical worsening early after reperfusion therapy in stroke. Stroke. (2021) 52:859–67. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gong P, Liu Y, Gong Y, Chen G, Zhang X, Wang S, et al. The association of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, platelet to lymphocyte ratio, and lymphocyte to monocyte ratio with post-thrombolysis early neurological outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Neuroinflammation. (2021) 18:51. 10.1186/s12974-021-02090-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lattanzi S, Cagnetti C, Rinaldi C, Angelocola S, Provinciali L, Silvestrini M. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio improves outcome prediction of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurol Sci. (2018) 387:98–102. 10.1016/j.jns.2018.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, Pandey S, Shen R, Xu Y, Zhang Q. Increased systemic immune-inflammation index is associated with delayed cerebral ischemia in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:745175. 10.3389/fneur.2021.745175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schiphorst AT, Charron S, Hassen WB, Provost C, Naggara O, Benzakoun J, et al. Tissue no-reflow despite full recanalization following thrombectomy for anterior circulation stroke with proximal occlusion: a clinical study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2021) 41:253–66. 10.1177/0271678X20954929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esenboa K, Kurtul A, Yamantürk Y, Tan TS, Tutar DE. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts no-reflow phenomenon after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Acta Cardiologica. (2021) 77:1–8. 10.1080/00015385.2021.1884786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maida CD, Norrito RL, Daidone M, Tuttolomondo A, Pinto A. Neuroinflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: focus on cardioembolic stroke, background, and therapeutic approaches. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:6454. 10.3390/ijms21186454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen C, Gu L, Chen L, Hu W, Feng X, Qiu F, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as potential predictors of prognosis in acute ischemic stroke. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:525621. 10.3389/fneur.2020.525621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee S-H, Jang MU, Kim Y, Park SY, Kim C, Kim YJ, et al. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios predict reperfusion and prognosis after endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke. J Pers Med. (2021) 11:696. 10.3390/jpm11080696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.