Abstract

In the onset and progression of psoriasis, redox imbalance is a vital factor. It's widely accepted that too much reactive oxygen species (ROS) always make psoriasis worse. Recent research, however, has shown that the accumulation of ROS is not entirely detrimental, as it helps reduce psoriasis lesions by inhibiting epidermal proliferation and keratinocyte death. As a result, ROS appears to have two opposing effects on the treatment of psoriasis. In this review, the current ROS-related therapies for psoriasis, including basic and clinical research, are presented. Additionally, the design and therapeutic benefits of various drug delivery systems and therapeutic approaches are examined, and a potential balance between anti-oxidative stress and ROS accumulation is also trying to be investigated.

Keywords: Psoriasis, ROS related therapies, Antioxidant, ROS accumulation

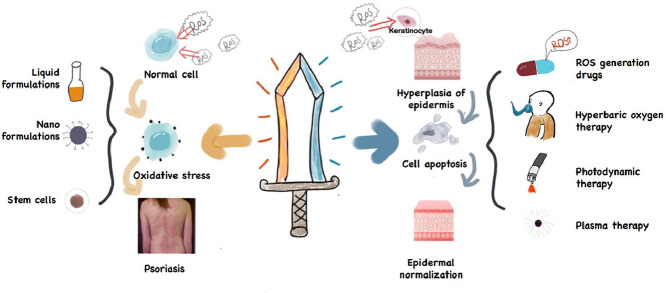

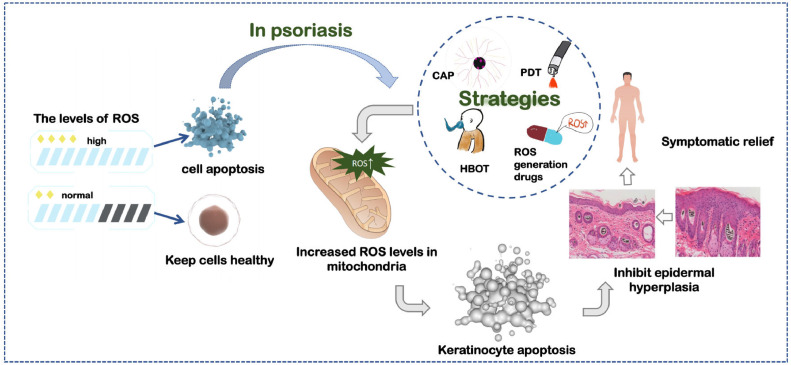

Graphical abstract

ROS plays a double-edged role in the treatment of psoriasis. Reducing the level of ROS can alleviate oxidative stress, while the accumulation of ROS inhibits epidermal hyperplasia by inducing apoptosis. Both ways can improve the symptoms of psoriasis.

1. Introduction

Psoriasis (Ps) is a common chronic, immune-mediated skin disease [1], which is clinically manifested as persistent itching, burning and soreness of the skin [2]. According to the skin manifestations of Ps patients, it can be divided into Ps Vulgaris, Ps guttate, Ps inverted, pustular Ps, etc. Multiple Ps phenotypes can sometimes manifest in the same patient. Approximately 125 million patients worldwide suffer from Ps at present [3]. The long duration and easy recur greatly impact patients' physical and mental health. Various studies on Ps prove that it is not just a partial skin disease, but systemic and inflammatory [4]. The increased release of immune-related cellular pro-inflammatory cytokines caused by Ps and the chronic activation of the innate and adaptive immune system [5,6] cause long-term damage to various tissues and organs of the human body, which in turn, causes a variety of serious complications. Among the common complications are rheumatism [6], [7], [8], cardiovascular diseases [8,9], and mental illnesses [9,10]. According to statistics, about 1/3 of patients with Ps eventually develop psoriatic arthritis [10,11]. Due to its high incidence rate, complex pathogenesis, serious complications, and lack of effective treatments, the therapeutic strategies of Ps arise broad interest worldwide. Every year, lots of new methods to treat Ps are proposed.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) is the general term for a series of molecular oxygen derivatives, such as superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, ozone, etc. ROS is highly reactive due to the presence of unpaired electrons. In organisms, superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide produced by mitochondrial respiration, is the major source of ROS [12]. The current view believes that ROS, as a pleiotropic physiological signal regulator, participates in redox regulation in the body [13] and is necessary for regulating cell physiological functions [14,15]. In the organism, the delicate balance between the production of ROS and the antioxidant mechanism of cells makes the body function normally [15,16]. Once this balance is broken, the harmful accumulation of ROS will put the body in a state of oxidative stress (OS) [15], [16], [17], which in turn, leads to a variety of adverse effects, including cell and tissue damage [18,19], DNA, lipid and protein peroxidation and modification [20] as well as neutrophil extracellular bactericidal network formation [21]. These changes may account for cancer [22,23], neurodegenerative diseases [24], [25], [26], diabetes [27,28] and many other serious diseases [29,30].

Skin is the main target organ of OS. The long-term existence of ROS in the microenvironment and the skin's metabolism may destroy the ROS defense mechanism and result in various skin diseases [31]. Ps is a disease with complex etiology. Although the exact mechanism of OS on Ps is not fully understood, it has been widely accepted that OS is involved in the occurrence and development of Ps [32]. OS caused by excessive production of ROS and decreased antioxidant capacity can change cell signaling pathways [33], which promotes the progression of Ps. Therefore, the treatment of Ps based on antioxidant stress is considered to be feasible. Currently, many studies have reported the treatment of Ps based on relieving OS [34,35].

On the other hand, although excessive ROS causes many kinds of damage to the body, ROS is gradually proven to play a dual role in some diseases. It is considered to have broad therapeutic potential in anti-cancer treatment [36,37] and regenerative medicine [38,39]. To date, ROS is widely used in treating many diseases [40], and the potential of using ROS to treat Ps is also discovered and reported. Although the exact mechanism is unclear, it seems that ROS is not always harmful to treating Ps.

Based on the duality of ROS in Ps treatment, this review elaborates on the role of ROS as a double-edged sword in the pathogenesis of Ps and the application of ROS related therapies in treating Ps.

2. Psoriasis and oxidative stress

2.1. The influence of oxidative stress on psoriasis

After years of exploration, people discover the possible mechanism of OS in the occurrence and progression of Ps. On the one hand, abnormal release and accumulation of ROS are found in Ps patients’ skin lesions. In the course of Ps, the abnormal activation of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α induces keratinocytes and fibroblasts to release ROS [41,42]. Neutrophils infiltrate the epidermis and form Munro microabscesses, which produce a large amount of ROS [43]. The abnormal release and accumulation of ROS in these cells put the body in a state of redox imbalance and ultimately lead to OS.

On the other hand, abnormal level of oxidase is also found in Ps patients. Compared with the neutrophils of healthy adults, the neutrophils obtained from Ps patients significantly enhance activities of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase and myeloperoxidase (MOP) [44], which may be the cause of the increased level of ROS in Ps fibroblasts [45]. The abnormal accumulation of ROS increases the consumption of antioxidants in the body, leading to the imbalance of the oxidative defense system in the body, which will also promote a state of OS for a long time.

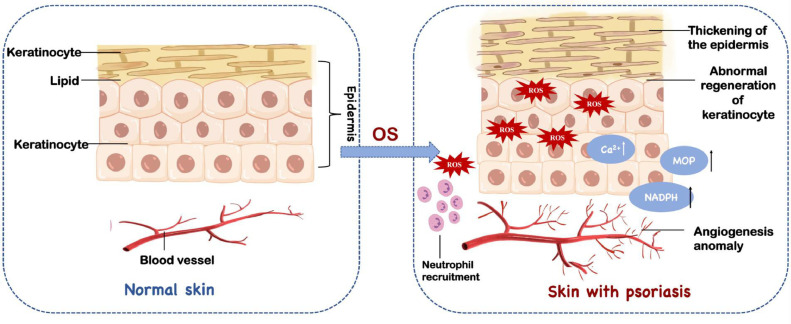

The body's long-term OS is likely to cause much harm. With the continuous overproduction of ROS, dendritic cells are stimulated to present antigens to T cells, which leads to the imbalance of T helper cells, abnormal proliferation of keratinocytes and abnormal angiogenesis [46,47]. The accumulation of ROS increases the level of calcium ions in the cytosol. Excessive calcium concentration leads to overload death of cells (Fig. 1) [48]. Meanwhile, ROS is also used as a signaling molecule to regulate various cellular pathways related to the progression of Ps, such as nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) [49]. Based on these evidence, it is generally believed that alleviating the body's OS state can reduce the symptoms of Ps [50]

Fig. 1.

Oxidative stress is one of the important factors in causing psoriasis. It has various damages to the body including abnormal angiogenesis, neutrophil recruitment and excessive proliferation of keratinocytes.

2.2. Formulations for psoriasis treatment based on antioxidant strategies

In recent years, studies have reported the treating formulations of Ps based on anti-oxidative stress. These formulations, which are summarized in Table 1, can be classified into the following types: liquid preparations, nano-based delivery systems and stem cells.

Table 1.

Formulations for psoriasis treatment based on antioxidant strategies

| Formulations | Drugs | Model | Delivery | Advantages | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid preparations | Catalpol | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Intraperitoneal | Not obviously | [54] | ||

| Quercetin | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Oral | Wide range of sources and strong efficacy in the treatment of psoriasis, making it a potential drug candidate. | [53,54] | |||

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Oral | Not obviously | [56,57] | |||

| Astilbin | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Oral | Downregulates the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor while alleviating oxidative stress. | [58] | |||

| Cimifugin | NHEKs& IMQ-induced Ps mice | Oral | Good security | [52] | |||

| Rottlerin | NHEKs & IMQ-induced Ps mice |

Oral | Multiple effects besides anti-inflammatory and antioxidant in treating psoriasis. | [55] | |||

| Kan-Lu-Hsiao-Tu-Tan | human neutrophils &IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal | Significant anti-inflammatory, antioxidant effects on neutrophils. | [59] | |||

| Perillyl alcohol | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal | Readily available and cost-effective with fewer side effects. | [62] | |||

| Astragalus mongholicus bunge water extract | human neutrophils &IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal | Topical application can effectively remove ROS and inhibit neutrophil activation. | [60] | |||

| Ambroxol | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Subcutaneous & Transdermal | High safety profile and exhibits excellent antioxidant as well as anti-inflammatory properties | [61] | |||

| Nano formulations | Nano particles | Cur | PLGA | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal | Encapsulation of Cur into PLGA enhances the biological activity of Cur by enhancing drug penetration, release and dispersion | [67] |

| VES-g-ε-PLL& silk fibroin |

This nano formulation exhibits enhanced skin penetration and a more effective anti-keratinization process. | [68] | |||||

| Bilirubin | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal | BRNPs caused little toxicity and high biocompatibility. | [73] | |||

| Bilirubin/JPH203 | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal | Weak toxicity while enhancing the therapeutic effect. | [90] | |||

| Gallic acid/ Rutin | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal | Good entrapment of drug in the chitosan polymer and remarkable control drug release. | [89] | |||

| CeO2 | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal | The introduction of β-CDs improved the water solubility, biocompatibility and antioxidant properties of CeNPs owe to its porous nanostructures with unique hydrophobic cavity. | [81] | |||

| ethosome | Curcumin/ Glycyrrhetinic acid |

IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal | It achieves the codelivery of Cur and GA to act as a synergistic treatment for psoriasis. | [91] | ||

| nanogel | Clobetasol propionate | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal | CP nanosponges offer several merits in terms of high payload, sustained release, high stability and solubilization capacity. | [77] | ||

| Babchi oil | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal | The nanogel results in high entrapment, sustained release of the drug and excellent therapeutic effects. | [70] | |||

| Stem cells | EVs | MBNs | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal | Simple preparation method with high biological safety and remarkable therapeutic effect. | [88] | |

| MSC-Exos | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal | Excellent biological safety. | [87] | |||

| HMSCs & vitamin E |

IMQ-induced Ps mice | Subcutaneous | Inhibit ROS accumulation to a greater extent | [97] | |||

| SOD3-transduced MSCs | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Subcutaneous | Immunomodulatory properties were enhanced | [95] |

2.2.1. Conventional liquid formulations

Benefiting from its wide range of sources, natural medicines are a significant source of new drug discovery [51] . Moreover, traditional herbal medicine is widely used in Asia, especially in China, Japan, and South Korea. With long-term use, some traditional herbal medicines' efficacy is widely recognized. In the future, if advanced scientific methods explore the mechanism of action of traditional herbal medicine, the practical components are extracted, and the useless or toxic parts are avoided, which probably provides patients with safer and more effective treatments. Since liquid formulations are usually easy to prepare and adaptable for multiple routes of administration, natural medicines tend to be first designed as liquid preparations to investigate their therapeutic potential on Ps. This section mainly focuses on liquid preparations of natural medicines that relieve OS in Ps.

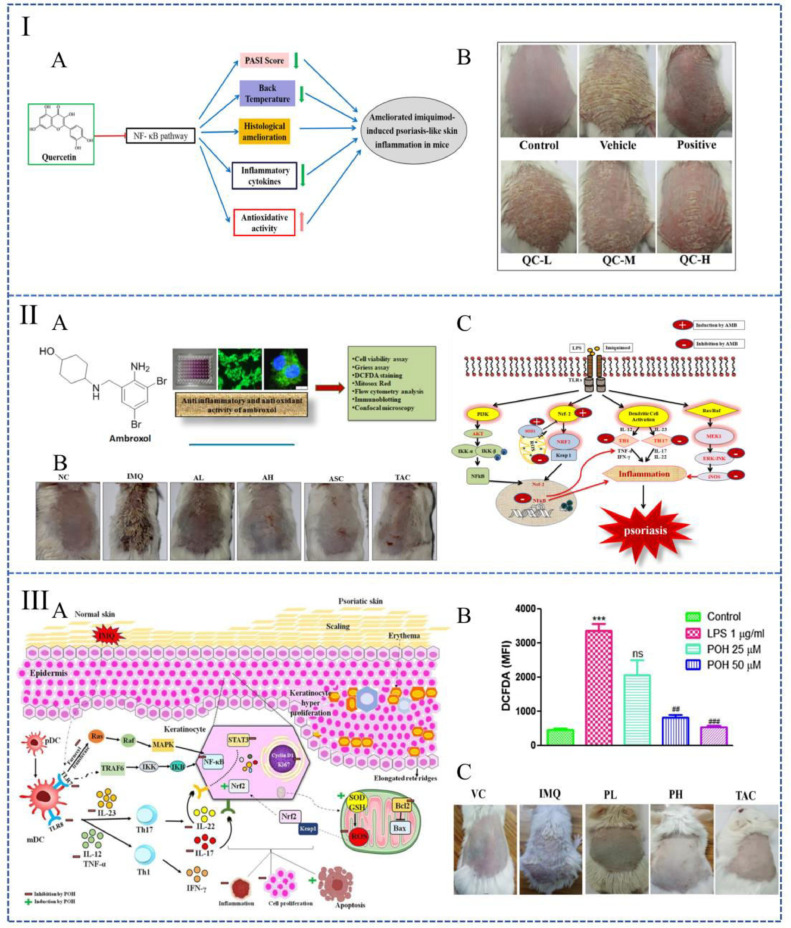

Liquid formulations for systemic administration: In the treatment of Ps, the systemic route of administration is mainly oral, while a few numbers of preparations are administered intraperitoneally. As studies reported, oral cimifugin [52], quercetin (Fig. 2I) [53] or intraperitoneal injection of catalpol [54] increase the levels of catalase (CAT), Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione (GSH), which consequently weaken the level of ROS and ameliorate Ps. Among them, cimifugin and catalpol regulate OS by inhibiting NF-κB and MAPKs pathways [52,54]. As for quercetin, OS is affected through the inhabitation of the non-canonical NF-κB [53]. It is also reported that rottlerin [55] and ginsenoside rg1 [56,57] have good therapeutic properties for Ps. They can inhibit OS by reducing ROS levels in keratinocytes. In addition, some drugs, such as astilbin, are able to ameliorate OS in the treatment of Ps by a different mechanism [58]. Astilbin is a type of flavonoid that has excellent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. Researchers found that oral astilbin is capable of increasing the accumulation of Nrf2 in the nucleus, as a result, various antioxidant-related proteins could be activated to decrease the level of ROS [58].

Fig. 2.

Liquid preparations used to treat psoriasis by alleviating oxidative stress. (I): Mechanism diagram of quercetin in the treatment of psoriasis (A); Macro images of the backs of mice 7 d after treating with quercetin (B). (Reproduced with permission from [53], Copyright© 2017 Elsevier B.V.); (II): Summary image of ambroxol for the treatment of psoriasis (A); Macroscopic image of mice back on the seventh day of treatment (B); A schematic diagram represents ambroxol's molecular mechanism against psoriasis (C). (Reproduced with permission from [61], Copyright© 2019 Elsevier B.V.). (III): Mechanism diagram of perillyl alcohol to improving psoriasis (A); Quantitative analysis of intracellular ROS levels after treating with perillyl alcohol (B); Macro images of the skin surface on the seventh day treating with perillyl alcohol (C). (Reproduced with permission from [62], Copyright© 2021 Elsevier B.V.).

Liquid formulations for topical administration: Systemic administration is usually challenging to achieve the desired therapeutic concentration and is highly toxic to the body. Based on this, it is necessary to develop formulations for topical administration.

Benefiting from less trauma, most liquid formulations tend to choose transdermal delivery. Recent studies point out that smear Kan-Lu-Hsiao-Tu-Tan (KLHTT, a traditional Chinese medicine formula) [59], astragalus mongholicus bunge water extrat [60], ambroxol [61] or perillyl alcohol [62]at the affected area of imiquimod (IMQ) -induced Ps mice effectively reduce the skin lesions. KLHTT and astragalus mongholicus bunge water extract decrease ROS generation by inhibiting the respiratory burst of neutrophils [59,60]. The NF-κB pathway can be inhibited by perillyl alcohol (Fig. 2III) and ambroxol [61,62]. Moreover, a study also compared the therapeutic effect of ambroxol between subcutaneous injection and transdermal delivery. The result indicated that subcutaneous injection achieves better efficacy at smaller therapeutic concentrations despite the relatively severe injuries (Fig. 2II) [61].

2.2.2. Nano-based formulations

Although some drugs have sound therapeutic effects on psoriasis, their poor stability and solubility, as well as their toxicity and irritation to the skin, limit their topical application. With research on nano formulations continuing to evolve, the utilization of nanocarriers in transdermal delivery is gaining great attention. It has tremendous benefits both in drug penetration enhancement and toxicity reduction for topical medications [63]. This section summarizes nano formulations that can modulate redox levels in psoriasis. These nano formulations are all delivered by transdermal.

Natural medicine combined with nano-based delivery system: As mentioned in the previous section, natural medicines have the potential for the treatment of Ps due to their excellent antioxidant properties. However, the traditional formulations of topical therapies are limited in bioavailability and efficacy, restricting the use of natural medicine. Since the nano-topical drug delivery system makes up for the deficiency of natural medicine, the combination of natural medicine and nano-topical drug delivery system is highly regarded.

While curcumin (Cur) is a natural drug with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [64], its aqueous solubility, chemical stability, and penetration ability across the skin are poor [65]. These properties limit its clinical application. Extensive evidence suggests that lipid- and polymer-based nanoparticles can improve drug permeability and reduce toxicity, benefiting from good compatibility with lipophilic drugs and high skin affinity [66]. In 2017, Sun et al. prepared a curcumin-loaded lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) nanoparticles for topical application to treat Ps [67]. MAO et al. prepared a hydrogel loaded with curcumin nanoparticles. They synthesized a self-assembled cationic nanoparticles amphiphilic polymer coated with curcumin at first, and the prepared nanoparticles were then mixed into silk fibroin hydrogel [68]. Both nanoparticles address the dispersion, sustained release, accumulation and penetration of lipophilic Cur, resulting in significantly improved anti-psoriasis activity in mice.

Babchi oil (BO) is an essential oil extracted from psoralen. It has been used in traditional Chinese medicine to treat skin conditions on account of its antimicrobial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [69]. But the conventional BO formulations are prone to oxidative degradation. What's worse, it is irritating and toxic to the skin when applied topically [70]. Cyclodextrin is shown to have the function of reducing local irritation and facilitating drug transport [71]. A preparation which uses cyclodextrin-based nanogel as a delivery carrier of BO effectively addresses the deficiencies of traditional BO formulations. This nanogel can provide sustained release, thereby reducing the frequency of administration. Meanwhile, it shows the therapeutic anti-psoriatic activity as well [70].

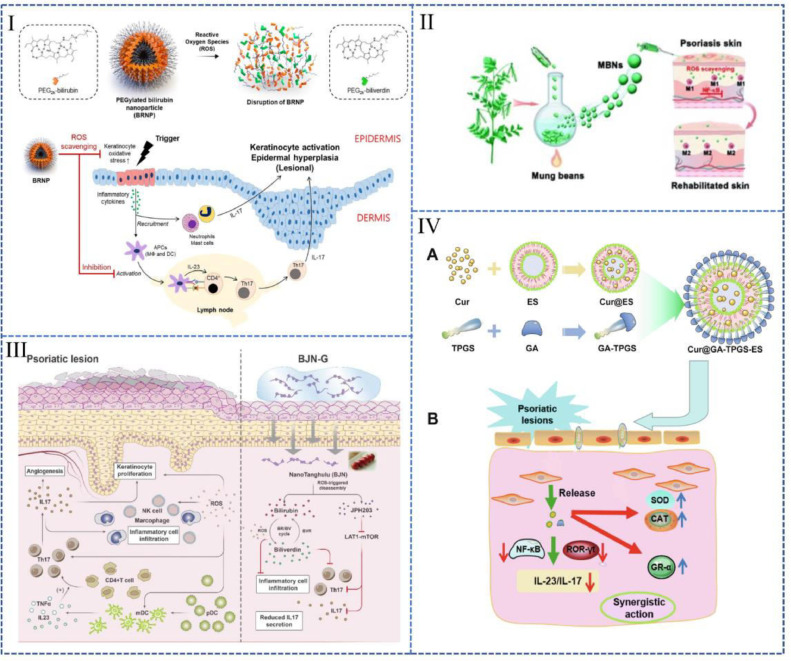

Bilirubin is an endogenous molecule with anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory properties [72]. A nanoparticle prepared with bilirubin and hydrophilic polyethylene glycol (BRNPs) (Fig. 3I) could easily penetrate the skin stratum corneum. It can be absorbed by keratinocytes, where it effectively reduced the accumulation of intracellular ROS [73]. This nanoparticle has high biocompatibility and biodegradability in response to ROS, which may make it a tremendous potential drug for clinical translation.

Fig. 3.

Nano preparations used to treat psoriasis by alleviating oxidative stress. (I): BRNPs (Reproduced with permission from [73], Copyright© 2020, Elsevier B.V.); (II): MBNs (Reproduced with permission from [88], Copyright© 2022, The Royal Society of Chemistry). (III): A "sugar gourd"-like nanoplatform co-loaded with bilirubin and JPH203 (Reproduced with permission from [90], Copyright© 2021 Elsevier B.V.). (IV): Ethosomes co-loaded with GA and Cur (Reproduced with permission from [91], Copyright © 2021 Elsevier B.V.).

Nano-delivery systems loaded with glucocorticoids drugs: Although some drugs have become the first-line drugs for the treatment of Ps in clinical practice, the significant toxicity and side effect often lead to limited application. Under this circumstance, modifying these drugs into nano-delivery systems can enhance safety.

Clobetasol propionate (CP) has great therapeutic effectiveness for Ps via regulating antioxidant enzymes and oxidative stress [74]. However, FDA stipulates the use of CP for not more than two weeks continuously [75] due to its side effects as a superpotent corticosteroid [76]. In 2021, Kumar et al. designed a CP-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponge hydrogel, which not only alleviates unfavorable side effects but also addresses formulation issues such as poor solubility and stability for CP [77]. Moreover, CP nanogel also has the characteristics of sustained release. This nanosponge hydrogel improves patient compliance, making CP potentially be long-term used.

Nanozymes: Nanozyme is a type of nanomaterials with enzyme-like activity [78]. Ceria nanoparticles (CeNPs) show great potential as antioxidant enzyme due to the dual oxidation states (Ce3+/Ce4+) on the surface of these particles in which Ce3+ is responsible for eradicating O2•−and •OH, while Ce4+ eliminating H2O2 [79]. CeNPs have been applied to treat various ROS-associated diseases. Yuan et al. designed a ceria nanozyme-integrated microneedles patch that can ameliorate OS to reshape the microenvironment of perifollicular for androgenetic alopecia treatment [80].

CeNPs have also been explored for Ps treatment. Wu et al. reported a multifunctional drug delivery system based on CeNPs capped with β-cyclodextrins (β-CDs) [81]. The β-CDs/CeO2 NPs could validly eliminate O2•− and H2O2 and provide excellent cryoprotection against ROS-mediated damage, thereby showing a splendid therapeutic effect in IMQ-induced psoriatic model. More importantly, introducing β-CDs improved the water solubility, biocompatibility and antioxidant properties of CeNPs owe to its porous nanostructures with unique hydrophobic cavities [81].

Extracellular vesicles: Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are nanometer-sized, lipid membrane-enclosed vesicles secreted by cells, which contain lipids, proteins, and nucleic acid of the source cell [82], [83], [84]. The abundant compositions of EVs such as mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) make them confer great potential in disease therapy. According to a recent study, MSC-Exos can ameliorate OS-induced skin injury by reducing ROS generation, aberrant calcium signaling, DNA damage and mitochondrial changes [85,86]. Zhang et al. demonstrated that topical application of MSC-Exos can effectively reduce the symptoms of IMQ-induced Ps [87]. In another study on EVs, topical administration of mung bean-derived extracellular vesicles (MBNs) reduced ROS and modulated the immune microenvironment, which lead to a relief of Ps (Fig. 3II) [88]. the study further suggested that the antioxidant properties of MBNs are realized by regulating macrophage polarization and inhibiting the activation of NF-κB signaling pathway. EVs derived from plants are relatively easy to obtain [88], which indicates a promising strategy of cell-free therapy represented by EVs in treating Ps.

Multi-drug co-loaded nano-delivery system: Nano-drug delivery system also has the ability to achieve synergistic delivery of multiple drugs. Considering the complex etiology, the monotherapy often fails to acquire ideal effect in Ps treatment. The combined therapy of topical antioxidants and anti-inflammatory drugs shows enhanced therapeutic effects to Ps. Shandil et al. demonstrated in a study focused on lutin and gallic acid that the nano-formulation combined with lutin and gallic acid showed better results than the individual drug [89]. In another research, a "sugar gourd"-like nanoplatform realized the co-loading of bilirubin with the specific LAT1 inhibitor JPH203 (Fig. 3III) [90]. This co-loading plays the effects of bilirubin and JPH203 simultaneously, including scavenging ROS, inhibiting cell proliferation and reducing the secretion of inflammatory factors.

Furthermore, nano-delivery systems such as ethosomes may enable co-delivery of two drugs with dramatically different physical properties. For instance, the co-application of glycyrrhetinic acid (GA) and curcumin (Cur) gains more efficiency in the treatment of Ps. Teng et al. prepared a type of ethosomes to achieve the co-delivery of GA and Cur with the assistance of d-α-tocopherol acid polyethylene glycol succinate (TPGS), which is a stabilizer, penetration enhancer and emulsifier (Fig. 3IV) [91]. In this system, the conjugates of GA and TPGS are inserted into the phospholipid layer, while Cur is distributed in the inner core of the liposome system.

This section focuses on nanoformulations that play an antioxidant role in treating psoriasis. As Ps is a skin disease, transdermal administration is the most acceptable way. Compared with traditional formulations, nanoformulations have the following advantages: (1) To improve the properties of the drug and promote its percutaneous absorption. (2) To achieve sustained and controlled release of drugs, which may be beneficial for long time utilization. (3) To achieve the combined delivery of multiple drugs. With proper design, the nano-delivery system could realize synergistic delivery of multiple drugs to improve the therapeutic effect of psoriasis.

2.2.3. Stem cells

Human mesenchymal stem cells (HMSCs) play an important role in immune regulation [92], cell survival [93]and anti-fibrosis [94]. It is a biological agent with good biocompatibility and wide application. HMSCs can both inhibit the production of ROS [95] and regulate the antioxidant system to improve the inflammatory microenvironment [96]. Therefore, HMSCs are also widely applied to treating Ps. Studies have found that the combined use of HMSCs and other drugs (such as vitamin E) can ameliorate OS in mice with IMQ-induced Ps and significantly improve the treatment effect. The combination of human adipose tissue-derived MSCs (hAD-MSCs) and vitamin E can make the frequency of administration descend, while, at the same time, inhibit ROS to a greater extent. Although the treatment mechanism remains unclear, researchers speculate that the antioxidant activity of extracellular vesicles may contribute to the effect [97]. According to another related study, superoxide dismutase (SOD3) transduced MSCs showed stronger immunomodulatory properties and antioxidant activity than MSCs alone. However, the limitation of MSCs cannot be ignored. Restricted by cell size, local administration of MSCs is usually achieved by subcutaneous injection, which causes relatively severe harm to the skin. Not only that, but the extraction cost of HMSCs is high. Thus, there is still a long way to go for the large-scale application of HMSCs.

3. Psoriasis and ROS accumulation

3.1. The positive effect of ROS accumulation on PS

Under normal circumstances, the elevated ROS usually destroys cellular components during oxidative stress, thus it is involved in the pathogenesis of various diseases such as cancer and inflammation [98]. However, the increasing evidence also showed that ROS has a dual role in tumors. Lower levels of ROS can promote cell survival and tumorigenesis, while elevated ROS levels can induce tumor cell apoptosis or senescence [99], [100], [101].

Similarly, the excessive proliferation and abnormal differentiation of epidermal keratinocytes is a vital characteristic of Ps, so inhibiting the excessive proliferation of keratinocytes is one of the main goals in Ps treatment. In addition, high levels of ROS have also been found to prevent IMQ-induced psoriatic dermatitis through promoting regulatory cells (Treg) function [102], while insufficient ROS can exacerbate the progression of Ps. Based on these facts, combating psoriasis through ROS accumulation has gradually received attention though the mechanism remains a deeper exploration. Since ROS-mediated reductions in keratinocyte necroptosis and inflammation-related factor levels are found in the research of psoriasis, the current view tends to suggest that the therapeutic effect of ROS accumulation on psoriasis is achieved by inhibiting epidermal hyperplasia and reducing skin inflammation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Excessive accumulation of ROS in the volume can induce apoptosis and inhibit tumors. In psoriasis, apoptosis mediated by ROS leads to normalization of the epidermis, as a result, improving symptoms in patient.

In the following, we would like to introduce the strategy of treating psoriasis with ROS aggregation from the following aspects: ROS generation drugs, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, photodynamic therapy and cold atmospheric pressure plasma therapy (summarized in Table 2).

Table 2.

Strategies for psoriasis treatment based on ROS accumulation.

| Strategies | Active substance | Model | Delivery | Advantages | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROS generation drugs | Gel | 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal delivery | Not obviously | [104] |

| Liquid preparation | Saikosaponin A | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Oral administration | Saikosaponin A has excellent anti-inflammatory effect in addition to promoting ROS generation to induce apoptosis. | [103] | |

| Convallatoxin | IMQ-induced Ps mice & TPA-induced epidermal hyperplasia mouse model | Transdermal delivery | Both drugs have been shown to inhibit epidermal hyperplasia by inducing necroptosis in two psoriasis models. | [107] | ||

| Periplogenin | IMQ-induced Ps mice& TPA-induced epidermal hyperplasia mouse model | Transdermal delivery | [108] | |||

| Nano formulation | Alantolactone | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal delivery | CHALT shows limited toxicity and good anti-psoriatic activity. | [105] | |

| Selenium | IMQ-induced Ps mice | Transdermal delivery | The biological inertness of SeNPs makes it cause less adverse effects. | [106] | ||

| HBOT | O2 | IMQ-induced Ps mice | —— | HBOT gains superior security. | [102] | |

| Photodynamic therapy | Systematic | ALA-PDT | K14-VEGF transgenic mice | Intraperitoneal injection | Photodynamic therapy is less invasive which is suitable for systemic administration. Simultaneous the use of safe photosensitizers reduces toxicity and side effects as well. | [113] |

| IR-780 -PDT | IMQ-induced mice model | Intravenous injection | [115] | |||

| Topical | ALA-PDT | IMQ-induced mice model | Transdermal delivery | [114] | ||

| MTX & ALA-PDT | IMQ-induced mice model | Transdermal delivery | The nanogel not only addresses the systemic toxicity of oral MTX, but also overcomes the low permeability of ALA. | [116] | ||

| CAP therapy | Surface air plasma | Cell model | —— | The plasma treatment is less harmful and it provides a new treatment idea for psoriasis. | [116,119] | |

| Cold atmospheric plasma | IMQ-induced Ps mice | —— | [120] | |||

3.2. Strategies for psoriasis treatment based on ROS accumulation

3.2.1. ROS generation drugs

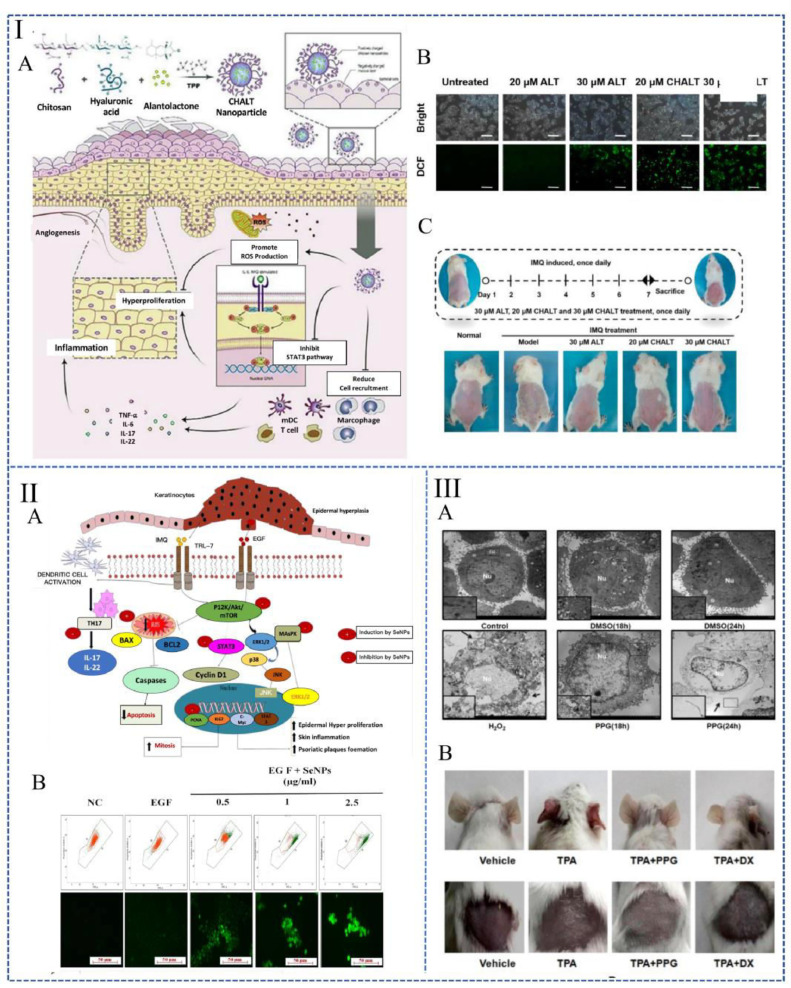

Several small-molecule active substances are found to promote ROS generation, disrupt mitochondrial membrane potential, and ultimately lead to necroptosis. These drugs have shown excellent therapeutic efficacy in Ps in preclinical studies. In the IMQ-induced Ps mice model, oral saikosaponin A [103] or topical application of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid [104], alantolactone-loaded chitosan/hyaluronic acid nanoparticles (CHALT) (Fig. 5I) [105] and selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) (Fig. 5II) [106] all play a role in promoting HaCaT cell apoptosis and inhibiting epidermal hyperplasia. Additionally, it is also reported that topical application of convallatoxin [107] and periplogenin (Fig. 5III) [108] has the capability to accelerate apoptosis which is ROS mediated. The results indicate Ps remission in both IMQ-induced and tissue plasminogen activator (TPA)-induced psoriasis models, whether treated with convallatoxin or periplogenin.

Fig. 5.

Drugs based on ROS generation for the treatment of psoriasis. (I): The in vivo fate map of CHALT (A). Generation of ROS in different groups under fluorescence (B). The experimental design and the macroscopic images of psoriatic mice backs after seven days of CHALT treatment (C). (Reproduced with permission from [105], Copyright ©2022, Shenyang Pharmaceutical University). (II): Mechanism of SeNPs in the treatment of psoriasis (A). (B): (a) Changes in mitochondrial membrane redox potential by SeNPs assessed by JC-1 staining. (b) DCFDA staining to determine the level of oxidative stress induced by SeNPs. (Reproduced with permission from [106], Copyright © 2021, The Authors). (ⅠII): Ultrastructural changes of HaCaT cells after periplogenin treatment (A). Perilogenin reduces skin inflammation and hyperplasia in a TPA-induced mouse model. Macro view of mice ears and backs at the end of the experiment (B). (Reproduced with permission from [108], Copyright © 2016 Elsevier Inc.).

3.2.2. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy

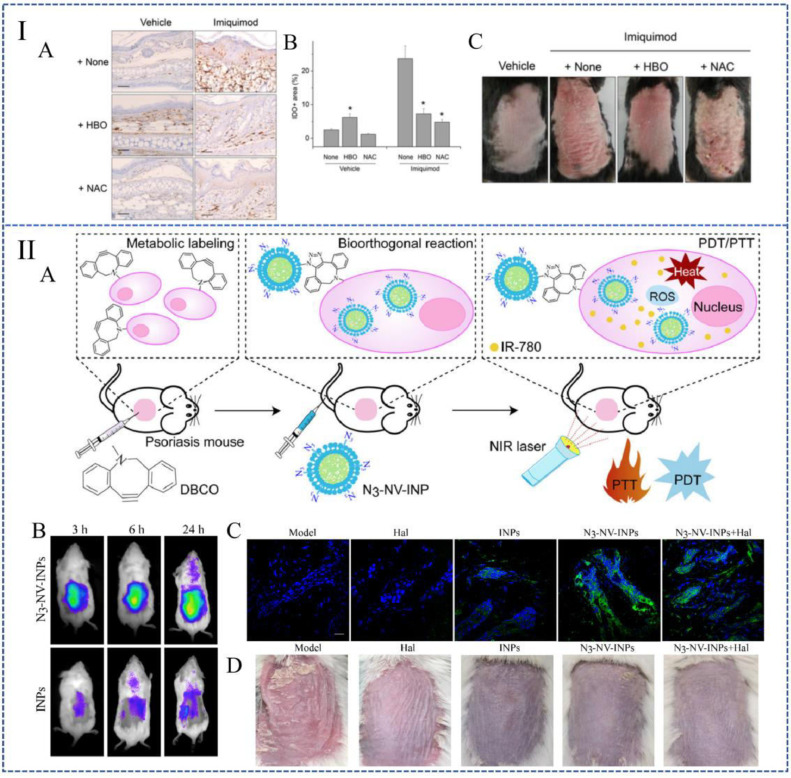

The treatment of breathing pure (100%) oxygen at increased atmospheric pressure is defined as hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). HBOT increases intracellular ROS levels in response to tissue hyperoxia (Fig. 6IA and 6IB) [109,110]. Studies reported that HBOT has a certain improved effect on IMQ-induced psoriatic dermatitis (Fig. 6IC). It is believed that this improvement is achieved by the increasing level of ROS and the enhancing function of Treg cells [102]. The sequelae of HBOT are very rare, which means it is a very safe treatment with excellent application prospects.

Fig. 6.

Therapeutic strategies based on ROS aggregation. (I): (A) and (B) HBOT increased the expression of IDO in healthy mice, indicating that ROS levels in tissue are elevated. (C) Macro view of mice backs. (Reproduced with permission from [102], Copyright ©2014 Kim et al.). (II): N3 -NV-INPs enhanced PDT in psoriasis. (A) Schematic representation of N3 -NV-INPs. (B) N3 -NV-INPs promote ROS generation. (C) In vivo imaging of mice after treating with N3-NV-INPs. (D) Macro images of mouse backs after treating with different drugs. (Reproduced with permission from [115], Copyright © 2021 Elsevier Ltd.).

3.2.3. Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is based on the accumulation of photosensitizers in target cells or tissues. When exposed to visible light under aerobic conditions, it will destroy cells and tissues through the formation of ROS and free radicals [111]. 5-Aminolevulinic acid (ALA), as a hydrophilic small molecule in the heme biosynthesis pathway, is one of the commonly used photosensitizers in PDT therapy [112]. According to the study conducted by Chen et al., the systemic treatment of K14-VEGF transgenic mice with ALA-PDT reduced the histological and clinical severity of Ps, which also effectively reduced the number of T cells and prevented the expression of IL-17 and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) [113]. Fei et al. further prove that ALA-PDT can attenuate the IFN-γ induced proliferation of keratinocytes by increasing the level of ROS, thereby relieving Ps lesions [114].

Although PDT is prized for its noninvasive characteristic and topical selective treatment, its limitations cannot be ignored. Recent research related to PDT focused on enhancing the therapeutic effects. There are mainly two ways of optimization. First, some photosensitizers have certain limitations. For example, IR-780 iodide has good tissue penetration; it can convert light energy into heat energy and increase ROS generation. However, IR-780 is rapidly cleared in the blood circulation. Combined with the low accumulation at target sites, its application is often limited. A study based on the artificial targeting strategy of bioorthogonal metabolic glycoengineering designed and synthesized a kind of cellular nanovesicles with bioorthogonal targeting (N3 -NV-INPs) [113], which increased the accumulation of photosensitizers in the diseased skin and promoted the PDT effect (Fig. 6II). In addition, PDT has also achieved good results synergistically with other treatments. A biomimetic nanogel which uses chitosan and hyaluronic acid as raw materials is designed to co-loaded ALA and methotrexate (MTX) to increase the curative effect on Ps [116]. This nanogel not only addressed the systemic toxicity of oral MTX, but also overcome the low permeability of ALA, achieving the desired therapeutic effect while minimizing side effects.

3.2.4. CAP therapy

Cold atmospheric pressure plasma (CAP) is an ionized gas produced by electrical discharge. It can control or trigger complex biochemical reactions at the cellular level by mixing active agents, mainly producing ROS and nitrogen species (RONS) [117]. As a way to induce ROS production, plasma therapy (including direct and indirect therapy) can provide continuous and controllable exogenous ROS, so that the body can reach an anti-proliferative ROS concentration. Keratinocytes in psoriatic lesions with oxidative imbalance can be preferentially eliminated by plasma-mediated oxidative damage, thereby improving abnormal skin proliferation [118]. Zhong et al. preliminarily proved that surface air plasma can not only cause decreased cell viability and apoptosis, but also reduce the ROS production in intracellular and mitochondrial in a dose-dependent manner at the cellular level [119]. Subsequently, Lu et al. confirmed that in the IMQ-induced Ps model, CAP treatment could alleviate psoriatic dermatitis, reducing epidermal growth and thinning the epidermis [120].

4. Clinical applications of ROS in the treatment of psoriasis

Generally speaking, the treatment based on antioxidant stress started earlier with broader applications than the treatment based on ROS accumulation in the clinical research of Ps (summarized in Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical applications of ROS on the treatment of psoriasis.

| Treatment | Patients | Research method | Therapeutic effect | Stage | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infliximab | 29 patients with moderate psoriasis | Parallel controlled trials | Infliximab therapy showed significant REDOX equilibrium effect. | Small sample clinical trials | [122] |

| Autologous Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells | 1 patient with psoriasis vulgaris, 1 patient with psoriatic arthritis | Self-control test | ROS levels were significantly reduced and patients' dependence on methotrexate, a powerful immunosuppressant, was reduced. | Small sample clinical trials | [122,123] |

| Molecular hydrogen | 3 patients with psoriasis and arthritis | Randomized double-blind parallel control | Psoriatic skin lesions almost disappeared by the end of treatment. | Small sample clinical trials | [124] |

| Hydrogen-water bathing | 41 patients with vulgaris psoriasis and 6 patients with plaque psoriasis | Parallel controlled trials were conducted in patients with psoriasis and self-controlled trials in patients with plaque psoriasis | Psoriasis symptoms relived significantly after treatment and can be used in patients with psoriasis who are resistant to other therapies. | Small sample clinical trials | [125] |

| Tapinarof | 228 patients with plaque psoriasis | Randomized double-blind parallel control | Tapinarof has been clinically demonstrated as significant efficacy topical drugs in the treatment of inflammatory skin diseases, with good tolerability and safety. | Phase III clinical trial accomplished | [128,131] |

| 500 patients with plaque psoriasis | Randomized double-blind parallel control | ||||

| ALA-PDT | 35 patients with fingernails psoriasis | Randomized double-blind parallel control | The clinical symptoms of patients were relieved, and ALA-PDA had obvious advantages in the treatment of severe psoriasis. | Small sample clinical trials | [130] |

| 311 nm narrow band UVB phototherapy | 22 patients with plaque psoriasis | Randomized double-blind parallel control | Oxidative stress-related parameters were significantly improved in the patients and their quality of life was improved. | Small sample clinical trials | [129] |

4.1. Clinical research based on antioxidant stress

Early clinical research mainly focused on conventional drugs in terms of inhibiting OS. Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α therapy is widely used to treat Ps [121]. However, its effect on the blood redox state remains unclear until 2013. Barygina et al. proved that using Infliximab for anti-TNF-α treatment has a significant redox balance effect in patients with moderate Ps. This is considered to be related to the normalization of NADPH enzyme activity in white blood cells [122].

In 2016, a study reported that the levels of ROS significantly reduced in a patient with Ps vulgaris (PV) and a patient with psoriatic arthritis (PA) after intravenous injection of Autologous Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (ADSCs). At the same time, it can reduce patients' dependence on the powerful immunosuppressant methotrexate, which illustrates the safety and potential clinical utility of ADSCs in treating autoimmune diseases (such as PV and PA) [123].

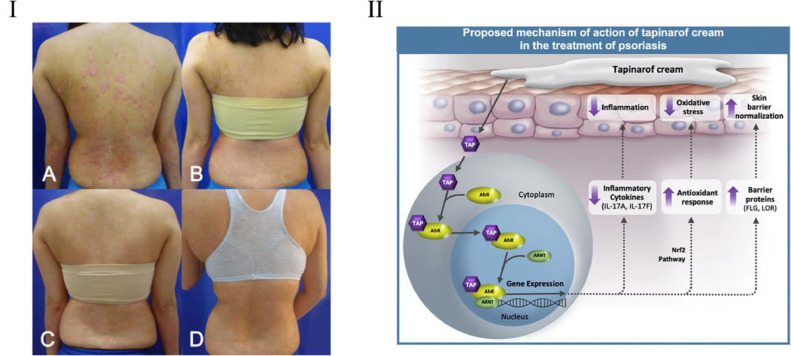

Molecular hydrogen (H2) is a classic ROS scavenger. In 2015, It was proposed by Ishibashi et al. that the skin lesions of psoriatic arthritis patients almost disappeared after molecular hydrogen treatment [124]. Although this is not a typical clinical study, it illustrates the effectiveness of molecular hydrogen in the treatment of Ps. Later, in 2018, in a clinical study involving 41 patients with Ps and 6 patients with plaque Ps, Zhu et al. proved that hydrogen-water bathing had a noticeable effect on relieving symptoms of Ps (Fig. 7I) [125]. It can be used for Ps patients who are resistant to other therapies.

Fig. 7.

Clinical studies on ROS-based treatment of psoriasis. (Ⅰ): Clinical evaluation of a patient after four weeks of hydrogen bath treatment. (Reproduced with permission from [125], Copyright © 2018 The AuthorS). (II): Potential mechanisms of action of tapinarof in the treatment of psoriasis. (Reproduced with permission from [131], Copyright ©2020 Elsevier Inc.).

Tapinarof is a small-molecule topical therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)–modulating agent. It is able to scavenge ROS, including hydroxyl free radicals and superoxide anions, showing good antioxidant activity [124]. Tapinarof also induces the AhR-Nrf2 transcription factor pathway, leading to the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes, which ultimately reduce ROS (Fig. 7II) [126,127]. Based on these characteristics, tapinarof is being developed clinically for the treatment of Ps and atopic dermatitis. The Phase III clinical trial of Tapinarof cream was completed in 2020 and fully announced [128], which proves it has good tolerance, safety and effectiveness. In 2021, the FDA accepted a new drug application for tapinarof cream to treat plaque psoriasis in adults.

Some specific wavelengths of light have also been clinically shown to alleviate OS in Ps treatment. In 2018, in a clinical study involving 22 patients with plaque psoriasis vulgaris, Darlenski et al. found that 311 nm narrow-band UVB phototherapy (NB-UVB) can ameliorate epidermal barrier function, SCH and systemic oxidative stress parameters. After treatment, the patient's Ps plaques are ameliorated with improved quality of life [129].

4.2. Clinical research based on ROS accumulation

In recent years, phototherapy has been favored by clinical research. In 2020, in a randomized, double-blind experiment involving 35 fingernail Ps patients, it was found that the aggregation of ROS caused by ALA-PDT induced the apoptosis of keratinocytes and ameliorated the clinical symptoms of patients, which was well tolerated [130]. It has obvious advantages compared with clobetasol propionate in treating severe Ps.

5. Conclusions and outlook

This review elaborates on the application of ROS as a double-edged sword in treating Ps (Table 4). Though it seems that both the treatment based on the elimination of ROS and the accumulation of ROS can ameliorate the symptoms to a certain extent, there does not exist an inevitable connection between the two approaches. Currently, the treatment of Ps based on antioxidant strategies occupies the mainstream. Many active substances with antioxidant properties have been prepared into various preparations in preclinical research. While little research focuses on ROS generation, some scholars have proposed that this kind of treatment idea has certain advantages. Apoptosis caused by ROS accumulation showed minimal inflammation and tissue damage [106], suggesting that strategies like ALA-PDT are possible to improve the compliance of patients, especially for those with severe skin lesions so that apoptosis-based therapy may have excellent research prospects in the future. Additionally, both therapy concepts have certain uses in clinical research. Nonetheless, it is difficult to compare which approach is better. A notable characteristic is the preference for systemic administration-friendly treatment modalities in clinical settings, such as PDT and UVB therapy.

Table 4.

Contrast between anti-OS and ROS generation strategies.

| Approaches to treating psoriasis | Antioxidant stress | ROS generation |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | By inhibiting NF-kB and other signaling pathways, these drugs can inhibit the generation of ROS in neutrophils and keratinocytes, thereby alleviating the oxidative stress state of the body. | The accumulation of ROS can disrupt mitochondrial membrane potential, ultimately inducing necroptosis. |

| Formulations & Therapy | Liquid formulations, nano formulations, stem cells | ROS generation drugs, PDT, CAP |

| Advantages | At present, many drugs for the treatment of psoriasis based on anti-OS have been reported. Among them some drugs have achieved better efficacy after improving dosage forms. | Apoptosis caused by ROS accumulation showed minimal inflammation and tissue damage, suggesting that patients are probably easier to accept this type of treatment. |

| Our opinions | In the progression of psoriasis, under the action of the oxidation and antioxidant systems in the body, the ROS level in the body may not always be in a state of oxidative stress, but in a dynamic state. Thus, it is necessary to clarify the level of ROS in different stages of psoriasis, and to use drugs for specific stages, so that the double-edged sword of ROS can be maximized. | |

In the previous sections, we strived to find a balance between anti-ROS and ROS generation in ameliorating Ps. However, almost all drugs either play an antioxidant role or promote ROS generation during the treatment. Also, since the current research for Ps based on ROS accumulation is far less than which based on anti-ROS, there is still a lack of the exact mechanism of ROS accumulation in treating Ps. Moreover, the exact mechanism of ROS in the onset, progression, treatment, and prognosis of psoriasis is unclear. The above facts give us great difficulty in finding a balance between these two treatment methods. However, we are trying to propose a hypothesis that in the progression of Ps, under the action of oxidation and antioxidant systems in the body, the ROS level may not always be in a state of oxidative stress but in a dynamic form. Based on this assumption, we believe that the real goal of treating psoriasis should be to improve the redox microenvironment in the body. Both anti-oxidation and pro-oxidation may only be the means to achieve this goal. Dimethyl fumarate has been used to treat psoriasis for over 20 years. For a long time, it has been widely believed that it is the antioxidant properties that provide relief from psoriasis [132]. However, in recent years, a study reported that it could also induce apoptosis by increasing the accumulation of ROS in keratinocytes [133]. Therefore, we believe that it is necessary to clarify the level of ROS in different stages of psoriasis, and to use drugs for specific stages, so that the double-edged effects of ROS can be maximized.

In summary, the review comprehensively summarizes ROS-related therapies for the treatment of psoriasis, first proposes the concept that “ROS is a double-edged sword”, and submits possible ideas for treating psoriasis according to existing studies, which may provide guidance and reference in the future.

Conflicts of interesting

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Griffiths C.E.M., Armstrong A.W., Gudjonsson J.E., Barker JNWN. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1301–1315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32549-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greb J.E., Goldminz A.M., Elder J.T., Lebwohl M.G., Gladman D.D., Wu J.J., et al. Psoriasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2(1):16082. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parisi R., Symmons D.P.M., Griffiths C.E.M., Ashcroft D.M. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(2):377–385. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang Y., Sarkar M.K., Tsoi L.C., Gudjonsson J.E. Psoriasis: a mixed autoimmune and autoinflammatory disease. Curr Opin Immunol. 2017;49:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harden J.L., Krueger J.G., Bowcock A.M. The immunogenetics of psoriasis: a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2015;64:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zachariae H., Zachariae R., Blomqvist K., Davidsson S., Molin L., Mørk C., et al. Quality of life and prevalence of arthritis reported by 5795 members of the nordic psoriasis associations. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82(2):108–113. doi: 10.1080/00015550252948130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gladman D.D., Antoni C., Mease P., Clegg D.O., Nash P. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(suppl 2) doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.032482. 14–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahlehoff O., Skov L., Gislason G., Lindhardsen J., Kristensen S.L., Iversen L., et al. Cardiovascular disease event rates in patients with severe psoriasis treated with systemic anti-inflammatory drugs: a D anish real-world cohort study. J Intern Med. 2013;273(2):197–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalgard F.J., Gieler U., Tomas-Aragones L., Lien L., Poot F., Jemec G.B.E., et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(2):984–991. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reich K., Krüger K., Mössner R., Augustin M. Epidemiology and clinical pattern of psoriatic arthritis in Germany: a prospective interdisciplinary epidemiological study of 1511 patients with plaque-type psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(4):1040–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.09023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mease P.J., Gladman D.D., Papp K.A., Khraishi M.M., Thaçi D., Behrens F., et al. Prevalence of rheumatologist-diagnosed psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis in European/North American dermatology clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sies H., Jones D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21(7):363–383. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J., Wang X., Vikash V., Ye Q., Wu D., Liu Y., et al. ROS and ROS-mediated cellular signaling. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/4350965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sena L.A., Chandel N.S. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell. 2012;48(2):158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Go Y.M., Jones D.P. Redox theory of aging: implications for health and disease. Clin Sci. 2017;131(14):1669–1688. doi: 10.1042/CS20160897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egea J., Fabregat I., Frapart Y.M., Ghezzi P., Görlach A., Kietzmann T., et al. European contribution to the study of ROS: a summary of the findings and prospects for the future from the COST action BM1203 (EU-ROS) Redox Biol. 2017;13:94–162. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sies H. Hydrogen peroxide as a central redox signaling molecule in physiological oxidative stress: oxidative eustress. Redox Biol. 2017;11:613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan D.Q., Suda T. Reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial homeostasis as regulators of stem cell fate and function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018;29(2):149–168. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liguori I., Russo G., Curcio F., Bulli G., Aran L., Della-Morte D., et al. Oxidative stress, aging, and diseases. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:757. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S158513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juan C.A., Pérez de la Lastra J.M., Plou F.J., Pérez-Lebeña E. The chemistry of reactive oxygen species (ROS) revisited: outlining their role in biological macromolecules (DNA, lipids and proteins) and induced pathologies. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):4642. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinegin B., Vorobjeva N., Pashenkov M., Chernyak B. The role of mitochondrial ROS in antibacterial immunity. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(5):3745–3754. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moloney J.N., Cotter T.G. ROS signalling in the biology of cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;80:50–64. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srinivas U.S., Tan B.W.Q., Vellayappan B.A., Jeyasekharan A.D. ROS and the DNA damage response in cancer. Redox Biol. 2019;25 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.101084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cobley J.N., Fiorello M.L., Bailey D.M. 13 reasons why the brain is susceptible to oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2018;15:490–503. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarafdar A., Pula G. The role of NADPH oxidases and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(12):3824. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sbodio J.I., Snyder S.H., Paul B.D. Redox mechanisms in neurodegeneration: from disease outcomes to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Sign. 2019;30(11):1450–1499. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watson J.D. Type 2 diabetes as a redox disease. Lancet. 2014;383(9919):841–843. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62365-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgos-Morón E., Abad-Jiménez Z., Martinez de Maranon A., Iannantuoni F., Escribano-López I., López-Domènech S., et al. Relationship between oxidative stress, ER stress, and inflammation in type 2 diabetes: the battle continues. J Clin Med. 2019;8(9):1385. doi: 10.3390/jcm8091385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shekhova E. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species as major effectors of antimicrobial immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Checa J., Aran J.M. Reactive oxygen species: drivers of physiological and pathological processes. J Inflamm Res. 2020;13:1057. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S275595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pleńkowska J., Gabig-Cimińska M., Mozolewski P. Oxidative stress as an important contributor to the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(17):6206. doi: 10.3390/ijms21176206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin X., Huang T. Oxidative stress in psoriasis and potential therapeutic use of antioxidants. Free Radic Res. 2016;50(6):585–595. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2016.1162301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cannavò S.P., Riso G., Casciaro M., di Salvo E., Gangemi S. Oxidative stress involvement in psoriasis: a systematic review. Free Radic Res. 2019;53(8):829–840. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2019.1648800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He X., Xue J., Shi L., Kong Y., Zhan Q., Sun Y., et al. Recent antioxidative nanomaterials toward wound dressing and disease treatment via ROS scavenging. Mater Today Nano. 2022;17 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forman H.J., Zhang H. Targeting oxidative stress in disease: promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20(9):689–709. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00233-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perillo B., di Donato M., Pezone A., di Zazzo E., Giovannelli P., Galasso G., et al. ROS in cancer therapy: the bright side of the moon. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52(2):192–203. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-0384-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cui Q., Wang J.Q., Assaraf Y.G., Ren L., Gupta P., Wei L., et al. Modulating ROS to overcome multidrug resistance in cancer. Drug Resist Update. 2018;41:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yao Y., Zhang H., Wang Z., Ding J., Wang S., Huang B., et al. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-responsive biomaterials mediate tissue microenvironments and tissue regeneration. J Mater Chem B. 2019;7(33):5019–5037. doi: 10.1039/c9tb00847k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diwanji N., Bergmann A. An unexpected friend−ROS in apoptosis-induced compensatory proliferation: implications for regeneration and cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;80:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen C., Pandey S. Exploiting mitochondrial vulnerabilities to trigger apoptosis selectively in cancer cells. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(7):916. doi: 10.3390/cancers11070916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baek J.O., Byamba D., Kim T.G., Kim D.S., Kim D.Y., Kim S.M., et al. Assessment of an imiquimod-induced psoriatic mouse model in relation to oxidative stress. J Dermatol Sci. 2013;69(2):e16. doi: 10.1007/s00403-012-1272-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang W.M., Jin H.Z. Role of neutrophils in psoriasis. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/3709749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chiang C.C., Cheng W.J., Korinek M., Lin C.Y., Hwang T.L. Neutrophils in psoriasis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2376. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dilek N., Dilek A.R., Taşkın Y., Erkinüresin T., Yalçın Ö., Saral Y. Contribution of myeloperoxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase to pathogenesis of psoriasis. Adv Dermatol Allergol. 2016;33(6):435. doi: 10.5114/ada.2016.63882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Becatti M., Barygina V., Mannucci A., Emmi G., Prisco D., Lotti T., et al. Sirt1 protects against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in fibroblasts from psoriatic patients: a new insight into the pathogenetic mechanisms of psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):1572. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oyoshi M.K., He R., Kumar L., Yoon J., Geha R.S. Cellular and molecular mechanisms in atopic dermatitis. Adv Immunol. 2009;102:135–226. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(09)01203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chamian F., Krueger J.G. Psoriasis vulgaris: an interplay of T lymphocytes, dendritic cells, and inflammatory cytokines in pathogenesis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(4):331–337. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000129715.35024.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magenta A., Dellambra E., Ciarapica R., Capogrossi M.C. Oxidative stress, microRNAs and cytosolic calcium homeostasis. Cell Calcium. 2016;60(3):207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abdel-Mawla M.Y., Nofal E., Khalifa N., Abdel-Shakoor R., Nasr M. Role of oxidative stress in psoriasis: an evaluation study. J Am Sci. 2013;9:151–155. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Medovic M.V., Jakovljevic V.L.J., Zivkovic V.I., Jeremic N.S., Jeremic J.N., Bolevich S.B., et al. Psoriasis between autoimmunity and oxidative stress: changes induced by different therapeutic approaches. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/2249834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berdigaliyev N., Aljofan M. An overview of drug discovery and development. Fut Med Chem. 2020;12(10):939–947. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2019-0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu A., Zhao W., Zhang B., Tu Y., Wang Q., Li J. Cimifugin ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis by inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation via NF-κB/MAPK pathway. Biosci Rep. 2020;40(6) doi: 10.1042/BSR20200471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen H., Lu C., Liu H., Wang M., Zhao H., Yan Y., et al. Quercetin ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice via the NF-κB pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;48:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu A., Zhang B., Zhao W., Tu Y., Wang Q., Li J. Catalpol ameliorates psoriasis-like phenotypes via SIRT1 mediated suppression of NF-κB and MAPKs signaling pathways. Bioengineered. 2021;12(1):183–195. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2020.1863015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Min M., Yan B.X., Wang P., Landeck L., Chen J.Q., Li W., et al. Rottlerin as a therapeutic approach in psoriasis: evidence from in vitro and in vivo studies. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi Q., He Q., Chen W., Long J., Zhang B. Ginsenoside Rg1 abolish imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis in BALB/c mice via downregulating NF-κB signaling pathway. J Food Biochem. 2019;43(11):e13032. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mao J., Ma X., Zhu J., Zhang H. Ginsenoside Rg1 ameliorates psoriasis-like skin lesions by suppressing proliferation and NLRP3 inflammasomes in keratinocytes. J Food Biochem. 2022:e14053. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.14053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang W., Yuhai W.H, Chasuna B. Astilbin reduces ROS accumulation and VEGF expression through Nrf2 in psoriasis-like skin disease. Biol Res. 2019;52(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s40659-019-0255-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chiang C.C., Cheng W.J., Lin C.Y., Lai K.H., Ju S.C., Lee C., et al. Kan-Lu-Hsiao-Tu-Tan, a traditional Chinese medicine formula, inhibits human neutrophil activation and ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;246 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheng W.J., Chiang C.C., Lin C.Y., Chen Y.L., Leu Y.L., Sie J.Y., et al. Astragalus mongholicus Bunge water extract exhibits anti-inflammatory effects in human neutrophils and alleviates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.762829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sunkari S., Thatikonda S., Pooladanda V., Challa V.S., Godugu C. Protective effects of ambroxol in psoriasis like skin inflammation: exploration of possible mechanisms. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;71:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sudha Yalamarthi S., Puppala E.R., Abubakar M., Saha P., Challa V.S., Np S., et al. Perillyl alcohol inhibits keratinocyte proliferation and attenuates imiquimod-induced psoriasis like skin-inflammation by modulating NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;103 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.108436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jeevanandam J., Chan Y.S., Danquah M.K. Nano-formulations of drugs: recent developments, impact and challenges. Biochimie. 2016;128–129:99–112. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kang D., Li B., Luo L., Jiang W., Lu Q., Rong M., et al. Curcumin shows excellent therapeutic effect on psoriasis in mouse model. Biochimie. 2016;123:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Raja M.A., Zeenat S., Arif M., Liu C. Self-assembled nanoparticles based on amphiphilic chitosan derivative and arginine for oral curcumin delivery. Int J Nanomed. 2016;11:4397. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S106116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Han S., Mei L., Quach T., Porter C., Trevaskis N. Lipophilic conjugates of drugs: a tool to improve drug pharmacokinetic and therapeutic profiles. Pharm Res. 2021;38(9):1497–1518. doi: 10.1007/s11095-021-03093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sun L., Liu Z., Wang L., Cun D., Tong H.H.Y., Yan R., et al. Enhanced topical penetration, system exposure and anti-psoriasis activity of two particle-sized, curcumin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles in hydrogel. J Control Rel. 2017;254:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.03.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mao K.L., Fan Z.L., Yuan J.D., Chen P.P., Yang J.J., Xu J., et al. Skin-penetrating polymeric nanoparticles incorporated in silk fibroin hydrogel for topical delivery of curcumin to improve its therapeutic effect on psoriasis mouse model. Colloid Surf B. 2017;160:704–714. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khushboo P.S., Jadhav V.M., Kadam V.J., Sathe N.S. Psoralea corylifolia Linn.—“Kushtanashini. Pharmacogn Rev. 2010;4(7):69. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.65331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumar S., Singh K.K., Rao R. Enhanced anti-psoriatic efficacy and regulation of oxidative stress of a novel topical babchi oil (Psoralea corylifolia) cyclodextrin-based nanogel in a mouse tail model. J Microencapsul. 2019;36(2):140–155. doi: 10.1080/02652048.2019.1612475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wadhwa G., Kumar S., Chhabra L., Mahant S., Rao R. Essential oil–cyclodextrin complexes: an updated review. J Incl Phenom Macrocycl Chem. 2017;89:39–58. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee Y., Kim H., Kang S., Lee J., Park J., Jon S. Bilirubin nanoparticles as a nanomedicine for anti-inflammation therapy. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2016;55(26):7460–7463. doi: 10.1002/anie.201602525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Keum H., Kim T.W., Kim Y., Seo C., Son Y., Kim J., et al. Bilirubin nanomedicine alleviates psoriatic skin inflammation by reducing oxidative stress and suppressing pathogenic signaling. J Control Rel. 2020;325:359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Patel H.K., Barot B.S., Parejiya P.B., Shelat P.K., Shukla A. Topical delivery of clobetasol propionate loaded microemulsion based gel for effective treatment of vitiligo: ex vivo permeation and skin irritation studies. Colloid Surf B. 2013;102:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Panonnummal R., Jayakumar R., Sabitha M. Comparative anti-psoriatic efficacy studies of clobetasol loaded chitin nanogel and marketed cream. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2017;96:193–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hengge U.R., Ruzicka T., Schwartz R.A., Cork M.J. Adverse effects of topical glucocorticosteroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kumar S., Prasad M., Rao R. Topical delivery of clobetasol propionate loaded nanosponge hydrogel for effective treatment of psoriasis: formulation, physicochemical characterization, antipsoriatic potential and biochemical estimation. Mater Sci Eng C. 2021;119 doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2020.111605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huang Y., Ren J., Qu X. Nanozymes: classification, catalytic mechanisms, activity regulation, and applications. Chem Rev. 2019;119(6):4357–4412. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nicolini V., Gambuzzi E., Malavasi G., Menabue L., Menziani M.C., Lusvardi G., et al. Evidence of catalase mimetic activity in Ce3+/Ce4+ doped bioactive glasses. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119(10):4009–4019. doi: 10.1021/jp511737b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yuan A., Xia F., Bian Q., Wu H., Gu Y., Wang T., et al. Ceria nanozyme-integrated microneedles reshape the perifollicular microenvironment for androgenetic alopecia treatment. ACS Nano. 2021;15(8):13759–13769. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c05272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wu L., Liu G., Wang W., Liu R., Liao L., Cheng N., et al. Cyclodextrin-modified CeO2 nanoparticles as a multifunctional nanozyme for combinational therapy of psoriasis. Int J Nanomed. 2020;15:2515. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S246783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Raposo G., Stahl P.D. Extracellular vesicles: a new communication paradigm? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(9):509–510. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yáñez-Mó M., Siljander P.R.M., Andreu Z., Bedina Zavec A., Borràs F.E., Buzas E.I., et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4(1):27066. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.27066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tkach M., Théry C. Communication by extracellular vesicles: where we are and where we need to go. Cell. 2016;164(6):1226–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Quiñones-Vico M.I., Sanabria-de la Torre R., Sánchez-Díaz M., Sierra-Sánchez Á., Montero-Vílchez T., Fernández-González A., et al. The role of exosomes derived from mesenchymal stromal cells in dermatology. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.647012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang T., Jian Z., Baskys A., Yang J., Li J., Guo H., et al. MSC-derived exosomes protect against oxidative stress-induced skin injury via adaptive regulation of the NRF2 defense system. Biomaterials. 2020;257 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang B., Lai R.C., Sim W.K., Choo A.B.H., Lane E.B., Lim S.K. Topical application of mesenchymal stem cell exosomes alleviates the imiquimod induced psoriasis-like inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(2):720. doi: 10.3390/ijms22020720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sun H., Zhao Y., Zhang P., Zhai S., Li W., Cui J. Transcutaneous delivery of mung bean-derived nanoparticles for amelioration of psoriasis-like skin inflammation. Nanoscale. 2022;14(8):3040–3048. doi: 10.1039/d1nr08229a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shandil A., Yadav M., Sharma N., Nagpal K., Jindal D.K., Deep A., et al. Targeting keratinocyte hyperproliferation, inflammation, oxidative species and microbial infection by biological macromolecule-based chitosan nanoparticle-mediated gallic acid–rutin combination for the treatment of psoriasis. Polymer Bull. 2020;77(9):4713–4738. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jiang X., Yao Q., Xia X., Tang Y., Sun M., Li Y., et al. Self-assembled nanoparticles with bilirubin/JPH203 alleviate imiquimod-induced psoriasis by reducing oxidative stress and suppressing Th17 expansion. Chem Eng J. 2022;431 [Google Scholar]

- 91.Guo T., Lu J., Fan Y., Zhang Y., Yin S., Sha X., et al. TPGS assists the percutaneous administration of curcumin and glycyrrhetinic acid coloaded functionalized ethosomes for the synergistic treatment of psoriasis. Int J Pharm. 2021;604 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Leyendecker Jr A., Pinheiro C.C.G., Amano M.T., Bueno D.F. The use of human mesenchymal stem cells as therapeutic agents for the in vivo treatment of immune-related diseases: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2056. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yoshida S., Miyagawa S., Fukushima S., Kawamura T., Kashiyama N., Ohashi F., et al. Maturation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes by soluble factors from human mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Ther. 2018;26:2681–2695. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.El Agha E., Kramann R., Schneider R.K., Li X., Seeger W., Humphreys B.D., et al. Mesenchymal stem cells in fibrotic disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21(2):166–177. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sah S.K., Park K.H., CO Y., Kang K.S., Kim T.Y. Effects of human mesenchymal stem cells transduced with superoxide dismutase on imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice. Antioxid Redox Sign. 2016;24(5):233–248. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Regmi S., Pathak S., Kim J.O., Yong C.S., Jeong J.H. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for the treatment of inflammatory diseases: challenges, opportunities, and future perspectives. Eur J Cell Biol. 2019;98(5–8) doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shi F., Guo L.C., Zhu W.D., Cai M.H., Chen L.L., Wu L., et al. Human adipose tissue-derived MSCs improve psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice by negatively regulating ROS. J Dermatol Treat. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2021.1925622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Harris I.S., DeNicola G.M. The complex interplay between antioxidants and ROS in cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2020;30(6):440–451. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Milkovic L., Cipak Gasparovic A., Cindric M., Mouthuy P.-.A., Zarkovic N. Short overview of ROS as cell function regulators and their implications in therapy concepts. Cells. 2019;8(8):793. doi: 10.3390/cells8080793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Guo Z., Wang G., Wu B., Chou W.C., Cheng L., Zhou C., et al. DCAF1 regulates Treg senescence via the ROS axis during immunological aging. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(11):5893–5908. doi: 10.1172/JCI136466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bian Q., Huang L., Xu Y., Wang R., Gu Y., Yuan A., et al. A facile low-dose photosensitizer-incorporated dissolving microneedles-based composite system for eliciting antitumor immunity and the abscopal effect. ACS Nano. 2021;15(12):19468–19479. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c06225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kim H.R., Lee A., Choi E.J., Hong M.P., Kie J.H., Lim W., et al. Reactive oxygen species prevent imiquimod-induced psoriatic dermatitis through enhancing regulatory T cell function. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e91146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liu M., Zhang G., Naqvi S., Zhang F., Kang T., Duan Q., et al. Cytotoxicity of Saikosaponin A targets HEKa cell through apoptosis induction by ROS accumulation and inflammation suppression via NF-κB pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;86 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gao J., Guo J., Nong Y., Mo W., Fang H., Mi J., et al. 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid induces human HaCaT keratinocytes apoptosis through ROS-mediated PI3K-Akt signalling pathway and ameliorates IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin lesions in mice. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2020;21(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s40360-020-00419-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chen R., Zhai Y.Y., Sun L., Wang Z., Xia X., Yao Q., et al. Alantolactone-loaded chitosan/hyaluronic acid nanoparticles suppress psoriasis by deactivating STAT3 pathway and restricting immune cell recruitment. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2022;17(2):268–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ajps.2022.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gangadevi V., Thatikonda S., Pooladanda V., Devabattula G., Godugu C. Selenium nanoparticles produce a beneficial effect in psoriasis by reducing epidermal hyperproliferation and inflammation. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s12951-021-00842-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jiang B.W., Zhang W.J., Wang Y., Tan L.P., Bao Y.L., Song Z.B., et al. Convallatoxin induces HaCaT cell necroptosis and ameliorates skin lesions in psoriasis-like mouse models. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;121 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhang W.J., Song Z.B., Bao Y.L., Li W., Yang X.G., Wang Q., et al. Periplogenin induces necroptotic cell death through oxidative stress in HaCaT cells and ameliorates skin lesions in the TPA- and IMQ-induced psoriasis-like mouse models. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;105:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Thom S.R. Oxidative stress is fundamental to hyperbaric oxygen therapy. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106(3):988–995. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91004.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Thom S.R. Hyperbaric oxygen–its mechanisms and efficacy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(1):131S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181fbe2bf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fonda-Pascual P., Moreno-Arrones O.M., Alegre-Sanchez A., Saceda-Corralo D., Buendia-Castaño D., Pindado-Ortega C., et al. In situ production of ROS in the skin by photodynamic therapy as a powerful tool in clinical dermatology. Methods. 2016;109:190–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gold M.H., Goldman M.P. 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy: where we have been and where we are going. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(8):1077–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chen T., Zhang L., Fu L., Wu Y., Liu X., Guo Z. Systemic ALA-PDT effectively blocks the development of psoriasis-like lesions and alleviates leucocyte infiltration in the K14-VEGF transgenic mouse. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42(8):849–856. doi: 10.1111/ced.13148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yi F., Zheng X., Fang F., Zhang J., Zhou B., Chen X. ALA-PDT alleviates the psoriasis by inhibiting JAK signalling pathway. Exp Dermatol. 2019;28(11):1227–1236. doi: 10.1111/exd.14017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang H., Su D., Huang R., Shu F., Cheng F., Zheng G. Cellular nanovesicles with bioorthogonal targeting enhance photodynamic/photothermal therapy in psoriasis. Acta Biomater. 2021;134:674–685. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wang Y., Fu S., Lu Y., Lai R., Liu Z., Luo W., et al. Chitosan/hyaluronan nanogels co-delivering methotrexate and 5-aminolevulinic acid: a combined chemo-photodynamic therapy for psoriasis. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;277 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]