Abstract

The Mga protein in B514Sm, a Streptococcus pyogenes strain isolated as a mouse pathogen, contains amino acid substitutions at conserved sites that render the protein defective. Replacement of mga50 with the functional homolog mga4.1 restored full expression of Mga-regulated proteins. Restoration of Mga function did not affect fibrinogen binding, nor did it affect virulence in several mouse models of group A streptococcus infection.

Streptococcus pyogenes, the group A streptococcus (GAS), is a gram-positive human pathogen responsible for diseases ranging from self-limiting pharyngitis and impetigo to the severe and life-threatening necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (7, 48). Several pleiotropic regulators of virulence factors have been identified for GAS, including Mga (9), the pel locus (27), and CovR (14, 17, 25). The multiple-gene regulator, Mga, is the best characterized of these and has been shown to activate expression of such important virulence determinants as M protein, M-related proteins (MRPs), C5a peptidase, and serum opacity factor (if present in the strain) (23, 29, 39, 46). Mga also activates its own expression (28).

GAS strain B514Sm (19) is a streptomycin-resistant derivative of strain B514, originally isolated as the causative agent in an outbreak of mouse respiratory disease (18). This strain is closely related to clinical isolates from GAS disease (52) and is itself capable of causing human disease (D. N. Kurl, Letter, Lancet ii:752, 1981). Recently, Yung et al. have shown that the mga50 allele from this strain contains three missense mutations at conserved residues and that these mutations render Mga50 defective (57). B514Sm contains three MRPs: Mrp, Emml, and Enn, which are expressed at very low levels in the wild-type strain (56). Expression of the homologous mga4.1 gene (derived from an M type 4 GAS strain) in trans from a multicopy plasmid complements the defective mga50, resulting in increased expression of Mga-regulated proteins (57).

We have used B514Sm to examine virulence in three mouse models of GAS infection. The first model, subcutaneous inoculation into the flanks of mice, enables assessment of the ability of GAS strains to colonize, invade tissues, and cause systemic infection (3) and mimics some types of invasive disease in humans. B514Sm is not lethal in this model of GAS infection, although infected mice do develop necrotic lesions at the site of inoculation (data not shown). In the second model, intratracheal inoculation, B514Sm is lethal because it causes pneumonia, usually within 3 days of infection (19). The third model, intranasal inoculation, results in either long-term throat colonization or lethal pneumonia, depending on the strain of mouse used (19). Both the intranasal and intratracheal infections mimic aspects of human GAS disease. Intranasal inoculation provides information about early stages of infection, such as pharyngeal colonization, and intratracheal inoculation addresses later stages of disease, including the massive infiltration of the lung by neutrophils and macrophages, destruction of lung tissue, and spread of the GAS to cause bacteremia (19). Since GAS infections sometimes result in lethal pneumonia in humans (4, 8), these models are useful for studying a specific human disease, as well as for studying the progression from pharyngitis to invasive disease and general host inflammatory responses to GAS infection (19).

Derivatives of B514Sm that contain mutations for production of MRPs or C5a peptidase showed no attenuation of virulence when inoculated intratracheally and no changes in the ability to colonize the throats of mice (20). Strains with mutations involving the production of hyaluronic acid capsule, however, had reduced ability to cause pneumonia in mice, and all bacteria that effectively colonized the throats of mice had reverted to the wild type (20). The presence of a defective Mga in B514Sm, and the resultant deficiency of the Mga-regulated MRPs and C5a peptidase (57), may be the reason that deletion of these proteins did not attenuate virulence in the mouse models. To address this, we have constructed a B514Sm derivative that expresses functional Mga, and we compared the virulence of this strain to that of the parent strain in mouse models of GAS infection.

Construction and characterization of mga deletion strain JRS934 and mga replacement strain JRS584.

Yung et al. (57) showed that mga50 was complemented by expression of mga4.1 in trans from a multicopy plasmid. To avoid the problem of abnormal gene dosage, and because plasmids are not always stably maintained by strains introduced into animals, we constructed a derivative of B514Sm in which the chromosomal mga50 allele was replaced with mga4.1. We first constructed JRS934, a B514Sm mutant in which 0.6 kb of internal mga50 sequence was replaced by the ΩKm-2 interposon (35). This step was necessary for two reasons: (i) because extensive homology between mga50 and mga4.1 would have allowed recombination to occur along the length of the gene, and we wanted to replace the entire mga50 with the entire mga4.1 rather than generate chimeric mga50::mga4 genes, and (ii) to provide a kanamycin resistance gene as a marker for the mga50 deletion strain (JRS934) to distinguish it from the parent strain (B514Sm) and the subsequent mga-replaced strain (JRS584).

Plasmid pMga4-4 contains the Mga regulon from GAS strain AP4 (M type 4), including the 3′ end of isp, all of mga4.1 and the region upstream of it, and the 5′ end of the mrp gene (2). Following removal of a 600-bp fragment internal to mga4.1 from pMga4-4 by BclI digestion, a 2.1-kb BamHI fragment from pUC4ΩKm2 (35) containing the ΩKm-2 interposon was ligated into the compatible BclI site to produce the mga4.2 allele carried on pJRS932. The 5.4-kb EcoRI-XbaI mga4.1 fragment from pJRS932 was blunted with T4 DNA polymerase and cloned into EcoRV-digested pJRS9160 (K. S. McIver and J. R. Scott, unpublished data), a derivative of the temperature-sensitive shuttle vector pJRS233 (38), to produce pJRS934. The mga50 deletion strain JRS934 was constructed using pJRS934 to replace mga50 with the mga4.2 allele (Fig. 1A) in the chromosome of B514Sm, as described previously (38). Construction of JRS934 was confirmed by PCR analysis.

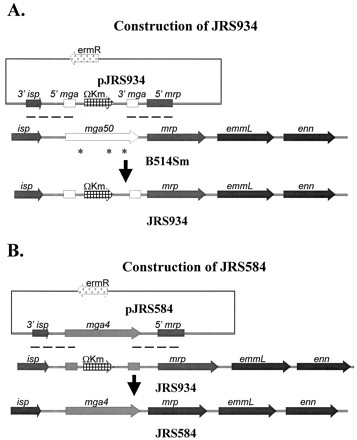

FIG. 1.

Construction of strains JRS934 and JRS584. (A) For JRS934, pJRS934 was used to replace the defective mga50 allele in the B514Sm chromosome with the mga4.2 allele, which contains the 5′ and 3′ ends of mga4.1 interrupted by the ΩKm interposon. The three missense mutations in mga50 are indicated by stars. Areas of homology where recombination can occur are indicated by dashed lines below the plasmid construct. (B) For JRS584, pJRS584 was used to replace the mga4.2 allele in the JRS934 chromosome with mga4.1 (light shading). Areas of homology where recombination can occur are indicated by dashed lines.

JRS934 was used as the parent strain for construction of JRS584, in which mga4.1 was substituted for mga50. The 3.6-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment from pMga4-4, containing the mga4.1 gene and surrounding sequences, was cloned into EcoRI-HindIII-digested pBluescript II KS(−) (Stratagene) to produce pJRS580. Plasmid pJRS584 contains the 3.6-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment from pJRS580 blunted with T4 DNA polymerase and cloned into EcoRV-digested pJRS9160 to create pJRS584. This plasmid was used as described previously (38) to replace mga4.2 with mga4.1 in the chromosome of JRS934 (Fig. 1B). This resulted in strain JRS584, which contains mga4.1, as confirmed by PCR analysis and sequence analysis of the entire mga gene.

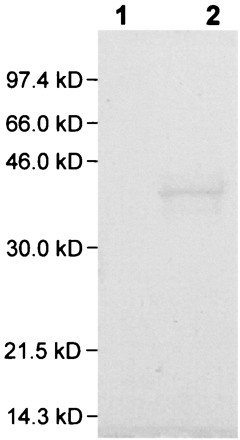

While it has been reported that expression of Mga4 protein from a multicopy plasmid in B514Sm resulted in increased expression of the MRPs, which constitute most of the surface proteins extractable by cyanogen bromide (57), a single copy of mga4.1 might not complement as effectively. Therefore, we investigated whether JRS584 efficiently expresses the MRPs. Surface proteins from B514Sm and JRS584 were extracted with cyanogen bromide (43) as described previously for B514Sm/pMga4 (57). These proteins were then separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) in a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel and visualized by staining with Coomassie blue (44). The protein profile of the cyanogen bromide extracts of JRS584 was essentially identical to that reported previously for B514/pMga4 (57) (Fig. 2), indicating that a single functional copy of mga complements the inactive mga50 allele for efficient expression of MRPs.

FIG. 2.

Surface proteins extracted with cyanogen bromide were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie blue staining. Lane 1, cyanogen bromide extract of B514Sm; lane 2, cyanogen bromide extract of JRS584.

A functional Mga does not affect virulence of B514Sm.

Although B514Sm is a mouse pathogen, it is not lethal for mice when inoculated subcutaneously (B. Limbago, V. Penumalli, B. Weinrick, and J. R. Scott, unpublished data). One reason for this could be the lack of MRPs expressed in this strain. Some M and M-related proteins have been implicated in binding to a variety of eukaryotic cell types, including keratinocytes and pharyngeal cells (5, 12, 32, 33, 37, 50). M proteins and MRPs are also important for bacterial survival in whole blood (24, 40), where these proteins bind several blood components, including immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgA, and fibrinogen (1, 6, 42, 47, 51, 54). IgG binding correlates with increased virulence in mouse models and bacterial survival in blood, although the molecular basis for this activity is not well understood (41, 42). In some strains, fibrinogen binding by the M protein and MRPs is needed for resistance to phagocytosis (12, 13, 53, 55), one of the main immunologically nonspecific clearance mechanisms for GAS infection (31). The ability to bind fibrinogen is also important for bacterial acquisition of plasmin-like activity, which has been implicated in destruction of the extracellular matrix and the invasive spread of GAS strains (11, 51).

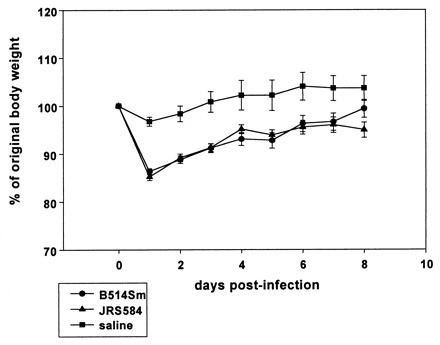

To determine if the presence of an active Mga protein causes B514Sm to be lethal, we compared the abilities of JRS584 and B514Sm to cause disease in mice when administered subcutaneously. Approximately 108 CFU of each strain was used to infect 10 (B514Sm) or 15 (JRS584) female CD1 mice subcutaneously, as described previously (3, 27a). Neither strain was lethal, and there was no difference in the size or morphology of the necrotic lesion formed (not shown). Analysis of changes in mouse body weight following infection is another way of assessing virulence and might detect subtle differences in stress levels between mice infected with the different strains. However, mice infected with either B514Sm or JRS584 initially lost ∼15% of their body mass, and then both groups began to gain weight by 2 days after infection (Fig. 3). This decrease in mass was due to GAS infection rather than to stress associated with inoculation, because mice injected with sterile saline showed only a small change in mass (<5%). Thus, restoration of a functional Mga protein did not result in increased virulence of B514Sm in the skin infection model.

FIG. 3.

Weight loss of mice following subcutaneous inoculation with GAS strains. Female CD1 mice inoculated with ∼108 CFU of B514Sm (circles), JRS584 (triangles), or sterile saline (squares) were weighed daily following inoculation. Average daily weight is plotted as a percentage of the average starting weight.

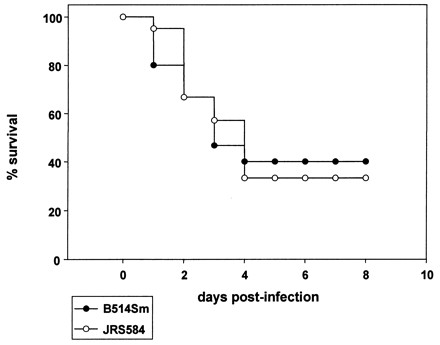

B514Sm is virulent for mice following intratracheal inoculation (19), so we examined whether restoring Mga function would increase the virulence of this strain. We compared the relative abilities of B514Sm and JRS584 to induce pneumonia in mice. Fifteen (B514Sm) or 21 (JRS584) female C3HeB/FeJ mice were inoculated intratracheally with 5 × 107 to 1 × 108 CFU of each strain as described previously (19). By 4 days postinfection, 40% of the mice inoculated with B514Sm, and 35% of the mice inoculated with JRS584, were alive (Fig. 4). This difference was not significant, as determined by a log-rank test (16).

FIG. 4.

Incidence of pneumonia following intratracheal inoculation with GAS strains. Mice were inoculated with ∼108 CFU of B514Sm (closed circles) or JRS584 (open circles) and monitored daily for development of pneumonia.

We also compared B514Sm and JRS584 in the intranasal model of GAS infection. In addition to the roles MRPs might have in the intratracheal model of infection, they might be important for adherence to pharyngeal tissue (32, 37, 50) and in preventing clearance in the early stages of respiratory disease. Ten female C57BL/6 mice were infected with 5 × 106 CFU of each strain as described previously (19; L. K. Husmann, unpublished data). By 10 days after intranasal inoculation, ∼60% of the mice infected with each strain developed pneumonia and were euthanized or died (not shown). Thus, we determined that B514Sm and JRS584 are equally efficient at causing pneumonia when inoculated either intranasally or intratracheally.

Fibrinogen binding of strains B514Sm and JRS584.

All of these experiments indicate that restoration of Mga function to strain B514Sm does not affect its virulence for mice. This was somewhat surprising, because M proteins are antiphagocytic (24) and have been shown to be important virulence determinants in other GAS strains (3, 26). The fact that B514Sm, which expresses extremely low levels of MRPs, is able to cause disease in mice (18, 19) and in humans (D. N. Kurl, letter) suggests that this strain has somehow bypassed the need for these proteins. M proteins are the main fibrinogen-binding molecules on the surface of GAS strains (21, 53, 55), and the bound fibrinogen helps to prevent bacterial clearance (53, 55) and may also be important for the tissue destruction associated with invasive disease (11, 51).

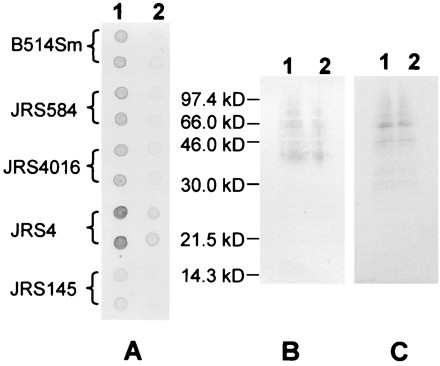

Since fibrinogen binding has many activities that are relevant to GAS survival in the host, we examined whether or not the MRPs on the surface of B514Sm and JRS584 were able to bind fibrinogen. JRS4, an M type 6 strain, and JRS145, an isogenic strain lacking M protein (9a), were included as positive and negative controls, respectively. JRS4016, which is isogenic to B514Sm but with a deletion of the MRP genes (20), was included as a negative control for MRP-specific binding activity. Binding activity of whole cells was assayed as follows: overnight cultures of each strain grown in THY broth (15) at 37°C were concentrated by centrifugation, resuspended in saline, and adjusted to equal concentrations based on optical density at 600 nm. Aliquots were spotted onto nitrocellulose and allowed to dry for 2 h at room temperature. Blots were probed with 1 μg of digoxigenin-labeled fibrinogen (Boehringer-Mannheim) and detected by an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antidigoxigenin antibody (Boehringer-Mannheim).

As expected, the M6 strain JRS4 bound fibrinogen, and the M− derivative JRS145 did not (Fig. 5A). Thus, in this strain, fibrinogen binding is dependent on the M protein. Surprisingly, B514Sm, JRS4016, and JRS584 all bound fibrinogen equally poorly (Fig. 5A). This indicates that restoration of Mga activity to B514Sm did not improve fibrinogen binding. It also suggests that unlike that of many other GAS strains (34, 47), fibrinogen binding by B514Sm does not depend on the MRPs.

FIG. 5.

Fibrinogen binding of B514Sm and JRS584. (A) Tenfold dilutions of equal amounts of cells from each strain were spotted onto nitrocellulose in duplicate and probed with digoxigenin-labeled fribrinogen. Lane 1, undiluted; lane 2, 10-fold dilution. (B) Surface proteins extracted with lysin were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and assayed for the ability to bind digoxigenin-labeled fibrinogen. Lane 1, phage lysin extract of B514Sm; lane 2, phage lysin extract of JRS584. (C) A gel identical to the one blotted for panel B was stained with Coomassie blue to show the amounts of protein loaded in each lane. Lanes are as in panel B.

To address the possibility that other surface proteins in B514Sm mask fibrinogen binding in whole-cell dot blots, we compared binding of surface protein extracts from B514Sm and JRS584. Extraction of surface proteins with cyanogen bromide releases fragments of M protein and MRPs of different sizes. The larger molecules, which are close to full-size proteins, retain the ability to bind fibrinogen (50a). Cyanogen bromide MRP extracts from equal amounts of GAS cells were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted to nitrocellulose (44), and assayed for fibrinogen binding. Although the MRPs from the Mga-replaced strain, JRS584, were present at essentially full size in the extract (Fig. 2), they did not bind fibrinogen (data not shown). When phage lysin was used to extract total surface proteins (14), many more bands were present (Fig. 5C), and some of these bound fibrinogen (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, the binding profiles were identical for the two strains. Since equivalent amounts of each lysin extract preparation were present in the gel (Fig. 5C), it appears that the MRPs extracted from JRS584 do not bind fibrinogen. Because many of the protein species in the phage lysin extract from both B514Sm and JRS584 that bound fibrinogen were larger than the MRPs (molecular mass, 35,000 to 42,000 Da; 57), it seems that a protein other than MRP is binding fibrinogen in this strain. It is possible that the >97-kDa protein in B514Sm that bound fibrinogen (Fig. 5B) is protein F, a 120-kDa protein that binds both fibronectin and fibrinogen in other strains (22). The other bands in the 40- to 66-kDa size range may be either breakdown products of protein F or additional fibrinogen-binding proteins.

Conclusions.

MRPs from other strains of GAS bind fibrinogen (1, 34, 47), but those from B514Sm and JRS584 apparently do not. However, we have shown that another protein (or proteins) in these strains binds fibrinogen. MRPs are considered the major virulence factors of GAS because of their antiphagocytic function, which depends on their ability to bind fibrinogen in some strains (12, 53). In B514Sm, the presence of additional factors with fibrinogen-binding activity may substitute for the MRPs, and this is presumably the reason that these proteins are not important for virulence of this strain (20). The accumulation of mutations in mga in B514Sm is consistent with the dispensability of the corresponding protein for virulence. This implies that Mga-activated proteins are not required for pathogenesis of this strain in the models examined. Although the role of serum opacity factor has not been examined directly for B514Sm with these mouse models, previous results indicate that deletion of scpA, the gene encoding the C5a peptidase, had little effect on virulence (20).

Different GAS strains use different combinations of factors to achieve the same end: virulence. This is suggested by the observation that established virulence factors are not always expressed by clinical GAS isolates (10, 30, 45, 49). In some strains, virulence depends on the presence of Mga-regulated proteins (23, 36). However, we have shown here that complementation of defective Mga50 with functional Mga4 does not affect virulence of B514Sm for mice. Thus, the need for Mga-regulated gene products has been bypassed in this strain, possibly because of the expression of other proteins with similar activity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R37-AI20723 from the National Institutes of Health, and K.S.M. was supported in part by National Research Service award AI09460 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

We thank Tim Barnett for help with the dot blot experiment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akerstrom B, Lindqvist A, Lindahl G. Binding properties of protein ARP, a bacterial IgA-receptor. Mol Immunol. 1991;28:349–357. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(91)90147-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson G, McIver K, Heden L O, Scott J R. Complementation of divergent mga genes in group A Streptococcus. Gene. 1996;175:77–81. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashbaugh C D, Warren H B, Carey V J, Wessels M R. Molecular analysis of the role of the group A streptococcal cysteine protease, hyaluronic acid capsule, and M protein in a murine model of human invasive soft-tissue infection. J Clin Investig. 1998;102:550–560. doi: 10.1172/JCI3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basiliere J L, Bistrong H W, Spence W F. Streptococcal pneumonia: recent outbreaks in military populations. Am J Med. 1968;44:580–589. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(68)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkower C, Ravins M, Moses A E, Hanski E. Expression of different group A streptococcal M proteins in an isogenic background demonstrates diversity in adherence to and invasion of eukaryotic cells. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1463–1475. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bessen D E, Fischetti V A. Nucleotide sequences of two adjacent M or M-like protein genes of group A streptococci: different RNA transcript levels and identification of a unique immunoglobulin A-binding protein. Infect Immun. 1992;60:124–135. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.124-135.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bisno A L, Stevens D L. Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:240–245. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601253340407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burmeister R W, Overholt E L. Pneumonia caused by hemolytic streptococcus. Arch Intern Med. 1963;111:367–375. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1963.03620270093015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caparon M G, Scott J R. Identification of a gene that regulates expression of M protein, the major virulence determinant of group A streptococci. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8677–8681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Caparon M G, Geist R T, Perez-Casal J, Scott J R. Environmental regulation of virulence in group A streptococci: transcription of the gene encoding the M protein is stimulated by carbon dioxide. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5693–5701. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.17.5693-5701.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaussee M S, Liu J, Stevens D L, Ferretti J J. Genetic and phenotypic diversity among isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes from invasive infections. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:901–908. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.4.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christner R, Li Z, Raeder R, Podbielski A, Boyle M D. Identification of key gene products required for acquisition of plasmin-like enzymatic activity by group A streptococci. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1115–1120. doi: 10.1086/516450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courtney H S, Liu S, Dale J B, Hasty D L. Conversion of M serotype 24 of Streptococcus pyogenes to M serotypes 5 and 18: effect on resistance to phagocytosis and adhesion to host cells. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2472–2474. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2472-2474.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dale J B, Washburn R G, Marques M B, Wessels M R. Hyaluronate capsule and surface M protein in resistance to opsonization of group A streptococci. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1495–1501. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1495-1501.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Federle M J, McIver K S, Scott J R. A response regulator that represses transcription of several virulence operons in the group A streptococcus. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3649–3657. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3649-3657.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischetti V A, Jones K F, Scott J R. Size variation of the M protein in group A streptococci. J Exp Med. 1985;161:1384–1401. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.6.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glantz S A. Primer of biostatistics. 4th ed. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill Health Professions Division; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heath A, DiRita V J, Barg N L, Engleberg N C. A two-component regulatory system, CsrR-CsrS, represses expression of three Streptococcus pyogenes virulence factors, hyaluronic acid capsule, streptolysin S, and pyrogenic exotoxin B. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5298–5305. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5298-5305.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hook E W, Wagner R R, Lancefield R C. An epizootic in Swiss mice caused by a group A streptococcus, newly designed type 50. Am J Hyg. 1960;72:111–119. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Husmann L K, Dillehay D L, Jennings V M, Scott J R. Streptococcus pyogenes infection in mice. Microb Pathog. 1996;20:213–224. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Husmann L K, Yung D L, Hollingshead S K, Scott J R. Role of putative virulence factors of Streptococcus pyogenes in mouse models of long-term throat colonization and pneumonia. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1422–1430. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1422-1430.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kantor F F. Fibrinogen precipitation by streptococcal M proteins. I. Identity of the reactants, and stoichiometry of the reaction. J Exp Med. 1965;121:849–859. doi: 10.1084/jem.121.5.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katerov V, Andreev A, Schalen C, Totolian A A. Protein F, a fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes, also binds human fibrinogen: isolation of the protein and mapping of the binding region. Microbiology. 1998;144:119–126. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-1-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kihlberg B M, Cooney J, Caparon M G, Olsen A, Bjork L. Biological properties of a Streptococcus pyogenes mutant generated by Tn916 insertion in mga. Microb Pathog. 1995;19:299–315. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(96)80003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lancefield R C. Current knowledge of type-specific M antigens of group A streptococci. J Immunol. 1962;89:307–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levin J C, Wessels M R. Identification of csrR/csrS, a genetic locus that regulates hyaluronic acid capsule synthesis in group A Streptococcus. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:209–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z, Ploplis V A, French E L, Boyle M D. Interaction between group A streptococci and the plasmin(ogen) system promotes virulence in a mouse skin infection model. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:907–914. doi: 10.1086/314654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Z, Sledjeski D D, Kreikemeyer B, Podbielski A, Boyle M D P. Identification of pel, a Streptococcus pyogenes locus that affects both surface and secreted proteins. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6019–6027. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.6019-6027.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27a.Limbago B, Penumalli W, Weinrick B, Scott J R. The role of streptolysin O in a mouse model of group A streptococcal disease. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6384–6390. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6384-6390.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McIver K S, Thurman A S, Scott J R. Regulation of mga transcription in the group A streptococcus: specific binding of mga within its own promoter and evidence for a negative regulator. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5373–5383. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5373-5383.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLandsborough L A, Cleary P P. Insertional inactivation of virR in Streptococcus pyogenes M49 demonstrates that VirR functions as a positive regulator of streptococcal C5a peptidase and M protein in OF+strains. Dev Biol Stand. 1995;85:149–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller-Alouf H, Geoffroy C, Geslin P, Bouvet A, Felten A, Gunther E, Ozegowski J H, Reichardt W, Alouf J E. Serotype, biotype, pyrogenic exotoxin, streptolysin O and exoenzyme patterns of invasive Streptococcus pyogenes isolates from patients with toxin shock syndrome, bacteremia and other severe infections. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;418:241–243. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1825-3_58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller-Eberhard H J, Gotze O. C3 proactivator convertase and its mode of action. J Exp Med. 1972;135:1003–1008. doi: 10.1084/jem.135.4.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okada N, Liszewski M K, Atkinson J P, Caparon M. Membrane cofactor protein (CD46) is a keratinocyte receptor for the M protein of the group A streptococcus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2489–2493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okada N, Pentland A P, Falk P, Caparon M G. M protein and protein F act as important determinants of cell-specific tropism of Streptococcus pyogenes in skin tissue. J Clin Investig. 1994;94:965–977. doi: 10.1172/JCI117463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Toole P, Stenberg L, Rissler M, Lindahl G. Two major classes in the M protein family in group A streptococci. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8661–8665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perez-Casal J, Caparon M G, Scott J R. Mry, a trans-acting positive regulator of the M protein gene of Streptococcus pyogenes with similarity to the receptor proteins of two-component regulatory systems. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2617–2624. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.8.2617-2624.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez-Casal J, Dillon H F, Husmann L K, Graham B, Scott J R. Virulence of two Streptococcus pyogenes strains (types M1 and M3) associated with toxic-shock-like syndrome depends on an intact mry-like gene. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5426–5430. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5426-5430.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perez-Casal J, Okada N, Caparon M G, Scott J R. Role of the conserved C-repeat region of the M protein of Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:907–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perez-Casal J, Price J A, Maguin E, Scott J R. An M protein with a single C repeat prevents phagocytosis of Streptococcus pyogenes: use of a temperature-sensitive shuttle vector to deliver homologous sequences to the chromosome of S. pyogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:809–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Podbielski A, Flosdorff A, Weber-Heynemann J. The group A streptococcal virR49 gene controls expression of four structural vir regulon genes. Infect Immun. 1995;63:9–20. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.9-20.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Podbielski A, Schnitzler N, Beyhs P, Boyle M D P. M-related protein (Mrp) contributes to group A streptococcal resistance to phagocytosis by human granulocytes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:429–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.377910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raeder R, Boyle M D. Analysis of immunoglobulin G-binding-protein expression by invasive isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2:484–486. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.4.484-486.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raeder R, Boyle M D. Association between expression of immunoglobulin G-binding proteins by group A streptococci and virulence in a mouse skin infection model. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1378–1384. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1378-1384.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raeder R, Otten R A, Chamberlin L, Boyle M D. Functional and serological analysis of type II immunoglobulin G-binding proteins expressed by pathogenic group A streptococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:3074–3081. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.12.3074-3081.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiseki M, Miwa K, Nemoto Y, Kato H, Suzuki J, Sekiya K, Murai T, Kikuchi T, Yamashita N, Totsuka K, Ooe K, Shimizu Y, Uchiyama T. Comparison of pathogenic factors expressed by group A Streptococci isolated from patients with streptococcal toxic shock syndrome and scarlet fever. Microb Pathog. 1999;27:243–252. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1999.0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simpson W J, LaPenta D, Chen C, Cleary P P. Coregulation of type 12 M protein and streptococcal C5a peptidase genes in group A streptococci: evidence for a virulence regulon controlled by the virR locus. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:696–700. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.696-700.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stenberg L, O'Toole P, Lindahl G. Many group A streptococcal strains express two different immunoglobulin-binding proteins, encoded by closely linked genes: characterization of the proteins expressed by four strains of different M-type. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1185–1194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stevens D L, Tanner M H, Winship J, Swarts R, Ries K M, Schlievert P M, Kaplan E. Severe group A streptococcal infections associated with a toxic shock-like syndrome and scarlet fever toxin A. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907063210101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Talkington D F, Schwartz B, Black C M, Todd J K, Elliott J, Breiman R F, Facklam R R. Association of phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of invasive Streptococcus pyogenes isolates with clinical components of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3369–3374. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3369-3374.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thern A, Stenberg L, Dahlback B, Lindahl G. Ig-binding surface proteins of Streptococcus pyogenes also bind human C4b-binding protein (C4BP), a regulatory component of the complement system. J Immunol. 1995;154:375–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50a.Tsivitse M, Boyle M D P. Evidence for independent binding domains within a group A streptococcal type IIo IgG-binding protein. Can J Microbiol. 1996;42:1172–1175. doi: 10.1139/m96-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang H, Lottenberg R, Boyle M D. Analysis of the interaction of group A streptococci with fibrinogen, streptokinase and plasminogen. Microb Pathog. 1995;18:153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(95)90013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whatmore A M, Kapur V, Sullivan D J, Musser J M, Kehoe M A. Non-congruent relationships between variation in emm gene sequences and the population genetic structure of group A streptococci. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:619–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whitnack E, Beachey E H. Antiopsonic activity of fibrinogen bound to M protein on the surface of group A streptococci. J Clin Investig. 1982;69:1042–1045. doi: 10.1172/JCI110508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whitnack E, Beachey E H. Biochemical and biological properties of the binding of human fibrinogen to M protein in group A streptococci. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:350–358. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.1.350-358.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whitnack E, Beachey E H. Inhibition of complement-mediated opsonization and phagocytosis of Streptococcus pyogenes by D fragments of fibrinogen and fibrin bound to cell surface M protein. J Exp Med. 1985;162:1983–1997. doi: 10.1084/jem.162.6.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yung D-L, Hollingshead S K. DNA sequencing and gene expression of the emm gene cluster in an M50 group A streptococcus strain virulent for mice. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2193–2200. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2193-2200.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yung D-L, McIver K S, Scott J R, Hollingshead S K. Attenuated expression of the mga virulence regulon in an M serotype 50 mouse-virulent group A streptococcal strain. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6691–6694. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6691-6694.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]