Abstract

Oxalate decarboxylase from Bacillus subtilis is a binuclear Mn‐dependent acid stress response enzyme that converts the mono‐anion of oxalic acid into formate and carbon dioxide in a redox neutral unimolecular disproportionation reaction. A π‐stacked tryptophan dimer, W96 and W274, at the interface between two monomer subunits facilitates long‐range electron transfer between the two Mn ions and plays an important role in the catalytic mechanism. Substitution of W96 with the unnatural amino acid 5‐hydroxytryptophan leads to a persistent EPR signal which can be traced back to the neutral radical of 5‐hydroxytryptophan with its hydroxyl proton removed. 5‐Hydroxytryptophan acts as a hole sink preventing the formation of Mn(III) at the N‐terminal active site and strongly suppresses enzymatic activity. The lower boundary of the standard reduction potential for the active site Mn(II)/Mn(III) couple can therefore be estimated as 740 mV against the normal hydrogen electrode at pH 4, the pH of maximum catalytic efficiency. Our results support the catalytic importance of long‐range electron transfer in oxalate decarboxylase while at the same time highlighting the utility of unnatural amino acid incorporation and specifically the use of 5‐hydroxytryptophan as an energetic sink for hole hopping to probe electron transfer in redox proteins.

Keywords: 5‐hydroxytryptophan, density functional theory, electron paramagnetic resonance, genetic code expansion, long range electron transfer, oxalate decarboxylase

1. INTRODUCTION

Genetic code expansion (GCE) technology has significantly expanded the biochemical toolbox over the past two decades to include selective incorporation of over 300 unnatural amino acids (UAAs) in proteins through codon suppression (de la Torre & Chin, 2021; Manandhar et al., 2021; Shandell et al., 2021; Young & Schultz, 2018). GCE codon suppression is significant for studying post‐translational modifications, specific cross‐linking on protein surfaces, and mechanistic enzymology (Addy et al., 2018; Cooley et al., 2014; Meichsner et al., 2021; Meyer et al., 2022).

Incorporation of tyrosine analogs are well documented and have been used to probe long‐range electron transfer (LRET) in ribonucleotide reductase and cytochrome c peroxidase (Chang, Yee, et al., 2004; Ravichandran et al., 2013; Ravichandran et al., 2017; Reece & Seyedsayamdost, 2017; Yee et al., 2019). Tryptophan analogs are increasingly used in recombinant proteins, primarily for their cross‐linking ability, their fluorescence properties, their ability to serve as pH sensors, and for GCE methods development (Bae et al., 2003; Boknevitz et al., 2019; Buddha & Crane, 2005; Budisa et al., 2002; Englert et al., 2015; Hilaire et al., 2017; Italia et al., 2017; Ohler et al., 2021; Pastore et al., 2022; Pratt & Ho, 1975; Ross et al., 1992; Singh‐Blom et al., 2014; Wong & Eftink, 1997). The selective incorporation of tryptophan analogs became feasible recently by applying GCE technologies as demonstrated by Italia et al. (2017), Englert et al. (2015), and Ficaretta et al. (2022) and is ideal for studying the biophysical role of tryptophan residues because their respective indole side chains possess different electronic properties (Ohler et al., 2021). Ohler et al. introduced 5‐hydroxytryptophan (5‐HTP) as well as fluorinated 5‐HTP into a β‐hairpin peptide and the copper protein azurin because of their unique radical EPR spectra and the lower standard potentials which makes these UAAs ideal probes to study redox processes in proteins (Ohler et al., 2021).

Oxalate decarboxylase (OxDC) consumes mono‐protonated oxalate to raise the cytosolic pH of Bacillus subtilis under acidic stress as shown in Scheme 1 (Tanner et al., 2001; Tanner & Bornemann, 2000). An interesting aspect of OxDC is the requirement of dioxygen as an initiator and Mn as a co‐factor despite the fact that the catalyzed reaction is nominally redox‐neutral (Saylor et al., 2012; Tanner et al., 2001).

SCHEME 1.

Decarboxylase activity of OxDC: Two Mn ions are cofactors in a single OxDC subunit. The resting state of the active site is Mn(II) while Mn(III) catalyzes the initial oxidation of the substrate (Twahir et al., 2016). The pH is raised by consumption of the acidic proton of the substrate and formation of a covalent C—H bond in the product, formate

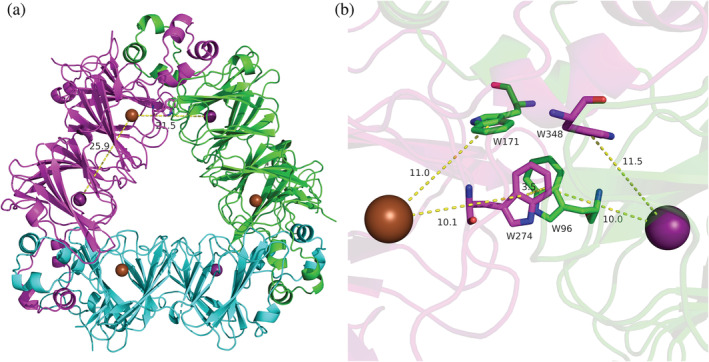

Half of the hexameric quaternary structure of OxDC is shown in Figure 1a forming a characteristic triangle with three protein subunits (Just et al., 2004). Each monomer subunit contains a bicupin motif with a Mn(II) ion in each cupin domain. The N‐terminal Mn was determined to be the active site by a combination of X‐ray crystallography and mutagenesis experiments (Imaram et al., 2011; Just et al., 2004; Moomaw et al., 2009). The presence of a Mn in the C‐terminal metal‐binding site is obligatory for activity (Moomaw et al., 2009). Because of the large distance between the two Mn ions of 25.9 Å within a subunit and 21.5 Å across subunit boundaries, a direct redox role was initially not considered for the C‐terminal Mn (Just et al., 2004). However, we recently reported the catalytic competency of a conserved π‐stacked tryptophan dimer, W96/W274, which straddles the boundaries of two subunits and features center‐to‐center distances to either Mn of the order of 10 Å (see Figure 1b) (Pastore et al., 2021). Substitution of W96 or W274 with redox‐inactive phenylalanine reduced catalytic efficiency while redox‐active tyrosine restored it. The conclusion was that W96 and W274 mediate LRET through a hole hopping mechanism (Pastore et al., 2021). Dioxygen is assumed to act as an initiator, possibly binding at the C‐terminal cupin domain and oxidizing the C‐terminal Mn(II) ion to Mn(III). The positive hole hops through the W96/W274 pair to the N‐terminal Mn(II) after substrate binds and generates oxidized Mn(III) at the N‐terminal site which drives catalysis (Pastore et al., 2021).

FIGURE 1.

(a) Trimer half of the hexameric quaternary assembly. In the crystal structure two of these trimers are stacked face‐to‐face to form the hexamer in the unit cell. The bicupin monomers are shown in green, cyan, and magenta colors. The Mn ions are shown as purple (N‐terminal) and brown (C‐terminal) spheres. (b) Interface between the green and magenta sub‐unit in (a) showing the 4‐TRP box with the π‐stacked dimer, W96 and W274, as well as monomers W171 and W348. Their colors (in part b) correspond to the respective subunit colors (in part a). Distances are measured from the center of the indole rings and are given in units of Å. Both figures used the low‐pH crystal structure of OxDC, 5VG3, and were drawn using PyMol

The present work focuses on the selective substitution of W96 with 5‐HTP in OxDC via opal (TGA) codon suppression. 5‐HTP has a lower reduction potential than tryptophan because of the electron donating hydroxyl group on the indole ring (Humphries et al., 1993; Humphries & Dryhurst, 1987; Ohler et al., 2021; Robinson et al., 2009). Therefore, we expected that enzymatic activity would be affected.

The selectivity of 5‐HTP incorporation was confirmed by trypsin digestion LC–MS/MS. The 5‐HTP substituted mutant enzyme was characterized by steady‐state kinetics and cw‐EPR spectroscopy. We find a stable carbon‐based radical in this mutant protein in the absence of substrate. Partially deuterated d4,d6,d7‐5‐HTP demonstrates that the corresponding radical is located on the 5‐HTP residue. This UAA acts as a sink for the hole keeping it away from the N‐terminal Mn where it is needed for catalysis thereby inactivating the enzyme. Our experiments provide a working guide to the use of selective 5‐HTP incorporation for mechanistic enzymology as well as probing charge transfer in protein–protein complexes.

2. RESULTS

2.1. Selectivity of 5‐HTP incorporation determined by mass spectrometry

The level of 5‐HTP incorporation was determined by LC–MS/MS after trypsin digestion of the protein as shown in Figure SI‐1 in the Data S1. The wild type (WT) and the mutant protein in the absence of any 5‐HTP during induction did not show any significant +16 u mass shift of any tryptophanyl group indicating that spontaneous oxidation of tryptophan is rare.

Using a 1 mM concentration of 5‐HTP during induction, we found an incorporation level of 98.6% at the 96th residue in the mutant. Partially deuterated d4,d6,d7‐5‐HTP was used to uniquely distinguish the target UAA from adventitiously oxidized tryptophan by an additional mass shift of +3 u. Because of the cost of the deuterated compound, a concentration of only 0.2 mM was used during induction. Incorporation of the deuterated 5‐HTP at W96 was therefore lower but nonetheless very specific showing a level of 41.5% at the 96th residue. Incorporation of 5‐HTP at other unmodified tryptophan sites was low, at or below 1.5% which may be possible due to low‐level incorporation of 5‐HTP into the native tryptophanyl tRNA synthetase.

2.2. Enzyme kinetics

The 5‐HTP mutant enzyme showed Michaelis–Menten kinetics for the decarboxylation of oxalate (see Data S1, Figure SI‐2). The kinetic parameters are given in Table 1. Mn incorporation is relatively low with only 0.64 Mn/monomer as determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP‐MS). It is not uncommon for OxDC mutants to show low Mn incorporation (Moomaw et al., 2009). Since activity is linear with Mn incorporation (Moomaw et al., 2009), the observed k cat was normalized by the number of Mn ions per subunit for comparison of activity between the mutant and WT enzyme. The 5‐HTP mutant showed approximately 20 times lower catalytic efficiency compared to WT. This loss of activity is even more pronounced than what we previously observed for the W96F mutation which showed approx. 8% of the catalytic activity of the WT enzyme (Pastore et al., 2021).

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters of the 5‐HTP mutant and WT OxDC

| Enzyme | K M (mM) | k cat (s−1) | Mn/monomer | k cat /Mn (s−1) | ε/Mn (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5‐HTP | 15.3 ± 1.5 | 0.72 ± 0.01 | 0.64 | 1.13 ± 0.11 | 74 ± 7 |

| WT | 33.3 ± 0.4 | 89.2 ± 1.4 | 1.93 | 46.2 ± 0.9 | (1.39 ± 0.03) × 103 |

Note: ε represents the catalytic efficiency, k cat/K M.

2.3. EPR spectroscopy

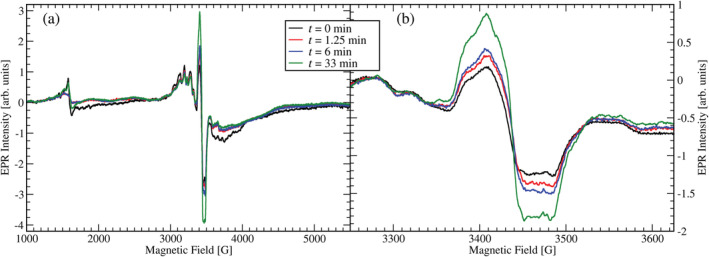

Figure 2a shows X‐band EPR spectra of the 5‐HTP substituted mutant enzyme at 6 K taken in perpendicular mode. The sample was prepared in succinate buffer and poised at pH 4.5. The typical g ≈ 2 multiline Mn(II) spectrum is observed between 2500 and 4000 G. Surprisingly, we observed a strong g = 2 radical signal at 3500 G. Figure 2b shows this signal with higher spectral resolution. It shows some poorly resolved fine structure and its apparent linewidth is ~119 G (measured between the low field and high field inflection points of the spectrum, see Data S1) which is large compared to the ~20 G linewidth of the tyrosyl radical usually seen in WT OxDC under turnover conditions (Chang, Svedružić, et al., 2004). The signal was not power‐broadened despite the low sample temperature of 6 K and relatively high microwave power of 0.6325 mW as observed in a power scan before the EPR spectra were recorded. WT OxDC does not show any carbon‐based radical signal in the absence of substrate or an oxidizing agent. Upon addition of oxalate, the g = 2 signal increased in intensity during turnover, reaching a maximum after approximately 2 h, corresponding with the time needed for the substrate to be consumed. Since the WT enzyme shows a small oxidase activity (approx. 0.2% of all turnovers) the oxidation potential of the solution rises over time due to the release of hydrogen peroxide (Tanner et al., 2001). This may explain the observed slow increase in EPR signal intensity under turnover conditions.

FIGURE 2.

CW EPR spectra of the 5‐HTP substituted mutant enzyme at pH 4.5 in X‐band before (black spectrum) and after reaction with substrate oxalate. The red, blue, and green spectra are scans after the reaction was stopped by freezing in liquid nitrogen after a cumulative reaction time of 1.25 min, 6.0 min, and 33 min, respectively. Enzyme concentration was 0.3 mM and initial substrate concentration was set at 50 mM. The EPR parameters were 9.6506 GHz frequency, 10 G modulation amplitude (part a) and 4 G modulation amplitude (part b). The modulation frequency was 100 kHz and the microwave power 0.6325 mW. The temperature was set at 6 K. (a) Wide field sweep. (b) Narrow sweep around the g = 2 region

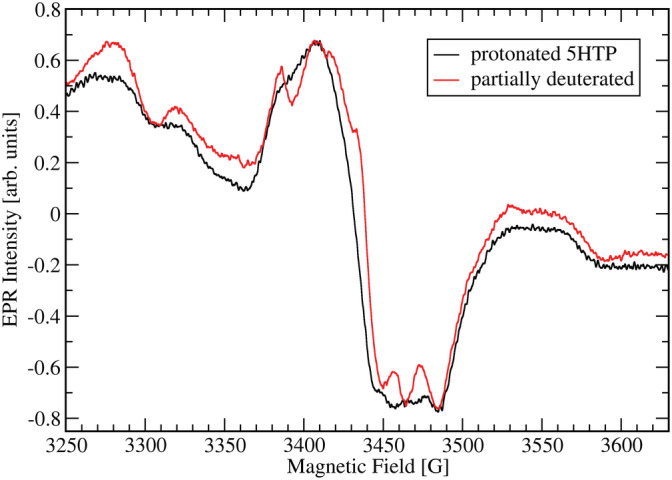

Given the low standard reduction potential of 5‐HTP, we suspected the g = 2 signal to arise from oxidized 5‐HTP. To test this possibility, we repeated the EPR measurements with partially deuterated d4,d6,d7‐5‐HTP (see Figure 3). Interestingly, the linewidth of the signal did not change much (114 G) but the resolution increased, and separated peaks became visible indicating that the radical's spin density was at least in part located on the partially deuterated indole ring.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison between the EPR spectra of the 5‐HTP substituted mutant enzyme with fully protonated 5‐HTP and partially deuterated 5‐HTP in the g ≈ 2 region. EPR parameters are the same for both spectra as given for Figure 2b

We also carried out parallel mode EPR experiments on the same samples to search for the Mn(III) signal which is visible at low pH in WT (Twahir et al., 2016). However, we were unable to observe any indication of Mn(III) in these samples (data not shown).

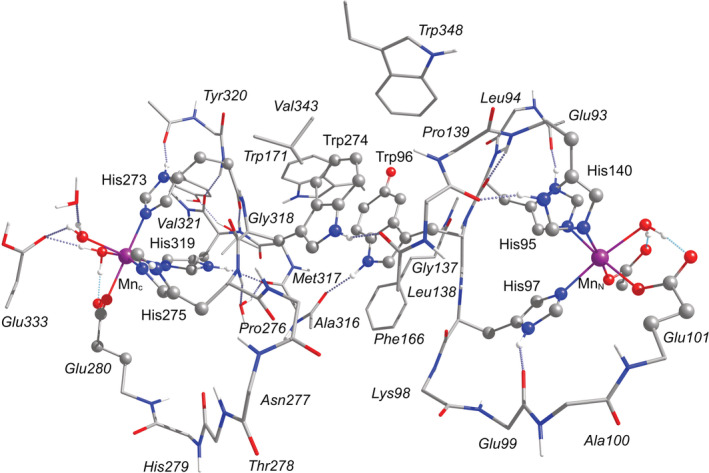

2.4. DFT calculations

Structural models of the OxDC active site from B. subtilis were constructed based on the low‐pH crystal structure of OxDC, PDB ID# 5VG3 (Burg et al., 2018; RCSB PDB, 2017). The models include the amino acids that directly coordinate the C‐ and N‐terminal Mn ions, as well as the W96/W274 pair, and residues between them, as shown in Figure 4. The W96 residue was modified by adding an oxygen atom on the 5C′ position to generate the deprotonated 5‐HTP that is expected to exist as a radical. Mn‐coordinated crystallographic water molecules were included in their aquo form. The C‐ and N‐terminal Mn(II) first coordination spheres and the 5‐HTP/W274 pair were optimized in separate calculations keeping the rest of the structure constrained, and subsequently combined into a single model. Long‐range effects were accounted for through implicit solvation. The resulting model consists of 441 atoms and is shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

DFT model of the OxDC active site with the labels of the amino acids as defined in the 5VG3 crystal structure from B. subtilis. Hydrogen atoms bonded to carbon atoms are omitted for clarity

Single‐point calculations were performed on this model to probe its electronic structure and spectroscopic properties. We first focused on the location and nature of the radical. If 5‐HTP is assumed to be a cationic radical, then our calculations show that localization of the unpaired electron on this residue (or any other) is not possible. Instead, the spin density corresponding to the unpaired electron is diffused throughout the model and distributed fractionally among 5‐HTP, W274, and several carboxylate and histidine residues (see Figure SI‐7A in Data S1). The loss of a proton from 5‐HTP is required to form a localized radical. Therefore, the DFT calculations confirm the nature of the observed radical as a neutral radical of 5‐HTP.

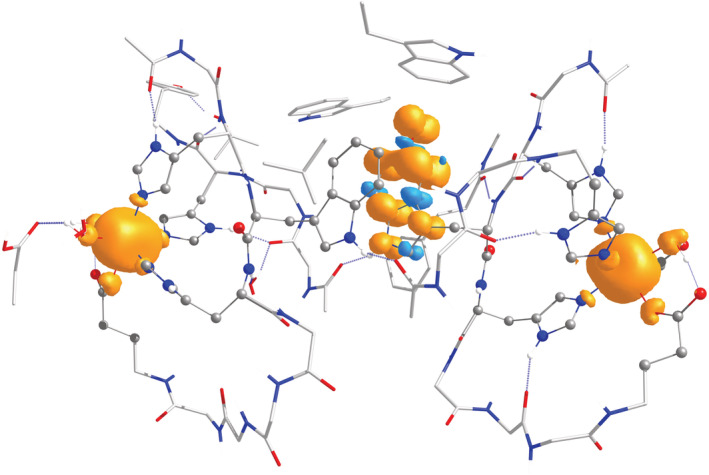

Two different deprotonation possibilities were examined. It is noted that for the isolated 5‐HTP˙ radical, deprotonation of the 5C′ oxygen to yield the neutral 5‐HTP˙ radical is energetically favored by 8 kcal mol−1 compared to the indole N deprotonation. This agrees with the results by Ohler et al. (2021). For the OxDC active site model, we computed this preference to be even stronger (energy difference of 21 kcal mol−1). This is in part because deprotonation of the nitrogen eliminates the hydrogen bonding interaction between the W96 nitrogen and the backbone carbonyl of A316 (see Figure 4). Therefore, we conclude that the best description of the radical is as a neutral 5‐HTP˙ radical that has been deprotonated at the 5C′ oxygen. The calculated Mulliken spin populations of the C‐terminal Mn, the N‐terminal Mn, and the neutral 5‐HTP˙ radical are 4.94, 4.93, and 1.02, respectively, showing clearly that the electron hole is localized on the deprotonated neutral 5‐HTP residue (π‐type distribution mirroring the frontier singly occupied orbital of the radical), while both Mn ions are in the Mn(II) oxidation state (high‐spin d5 electronic configuration). The total spin density distribution is illustrated in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

Total spin density distribution plot for the OxDC model of the 5HTP/W274 neutral radical with the hydroxide proton of the 5‐HTP removed

We also calculated the expected g‐tensor and anisotropic hyperfine coupling constants for the indole nitrogen and all protons in the 5‐HTP radicals (see Data S1, Tables SI‐2 through SI‐8) and simulated the expected EPR spectra using the Easyspin toolbox for MATLAB™ (see Data S1, Figures SI‐9 through SI‐11) (Stoll & Schweiger, 2006). We found peak‐to‐peak linewidths of the predicted spectra of 17 G and 12 G for the protonated and partially deuterated 5‐HTP˙ radicals well below those observed in the mutant enzyme.

The isotropic exchange coupling constants between the Mn(II) ions and the neutral 5‐HTP˙ radical were calculated using broken‐symmetry DFT. For the N‐terminal Mn(II) ion the coupling to the neutral 5‐HTP˙ radical is 0.005 cm−1 (150 MHz) and for the C‐terminal Mn(II) ion it is 0.001 cm−1 (26 MHz). An exchange coupling of 150 MHz would result in an EPR linewidth of almost 300 G (see Data S1, Figure SI‐13). However, a reduced coupling constant of 50 MHz gave approximately the right linewidth with a small reduction to around 97% upon deuteration (see Data S1, Figure SI‐14).

The vertical ionization energy (VIE) of the 5‐HTP/W274 pair was calculated following the same procedure as before (Pastore et al., 2021). With only 6.77 eV it was found to be significantly lower than the previously calculated 7.09 eV for the W96/W274 pair in WT enzyme.

3. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Complete and specific labelling for 5‐HTP and other tryptophan analogs has been observed for green fluorescent protein with the same expression system described in our work (Italia et al., 2017). When 5‐HTP is not present during induction, other amino acids, including tryptophan, can be inserted at opal codons based on their low but finite affinity to the engineered tryptophanyl tRNA synthetase.

5‐HTP is structurally similar to tryptophan and the quaternary assembly of the protein is therefore expected to be unperturbed, just like in the case of W96F and W96Y (Pastore et al., 2021). The native PAGE patterns (see Data S1, Figure SI‐3) imply that the mutant assembles similar to WT in solution. Therefore, our results indicate that the 5‐HTP mutant is properly expressed and stable for characterization.

The hydroxyl group at position 5 results in a significantly lower one‐electron reduction potential for the 5‐HTP/5‐HTP˙ pair compared to tryptophan (Jovanovic et al., 1990; Mahmoudi et al., 2016; Ohler et al., 2021). With only ~565 mV against the normal hydrogen electrode (NHE), the 5‐HTP standard reduction potential at pH 7 is about 420 mV below that of a regular TRP/TRP˙ couple. At pH 4 the potential of the 5‐HTP/5‐HTP˙ pair is expected to be ~740 mV against NHE because of its pH dependence of about −59 mV per pH unit (Ohler et al., 2021). Since 5‐HTP acts as a “hole sink” in OxDC (vide infra), we can take 740 mV as the lower bounds of the standard potential of the Mn(II)/Mn(III) couple in the active site of OxDC at pH 4. The upper bounds may be set theoretically at ~1100 mV based on the estimated standard potential of the π‐stacked TRP pair W96/W274 (Merkel et al., 2009; Pastore et al., 2021; Roy et al., 2018).

Since incorporation of 5‐HTP prevents the formation of Mn(III) at the N‐terminal Mn site even in the presence of small carboxylates, enzymatic activity should be negligible because Mn(III) is required for catalysis (Twahir et al., 2016). The residual activity seen in the 5‐HTP mutant enzyme is likely due to a small amount of protein without 5‐HTP incorporation. If 98.6% of W96 is replaced by 5‐HTP and shows no activity, and the remaining 1.4% of unsubstituted enzyme has WT‐like activity, the preparation would be expected to show a reduced k cat = (1.4%) (89.2 s−1) = 1.2 s−1. This is further reduced to 0.41 s−1 if only 0.64 Mn is present in the unsubstituted monomer units. The observed value of 0.72 s−1 is therefore compatible with the assumption that the 5‐HTP substituted enzyme is inactive.

The loss of activity in the 5‐HTP mutant enzyme supports our previous conclusion that W96 is critical for catalysis (Pastore et al., 2021). Phenylalanine is more difficult and 5‐HTP is easier to oxidize than tryptophan (Roy et al., 2018). This can also be seen in the calculated VIEs of these species in the OxDC pair structure of 7.19 eV, 6.77 eV, and 7.09 eV for the W96F, 5‐HTP substituted, and WT proteins, respectively (Pastore et al., 2021). Clearly, W96F presents a higher energy barrier for hole hopping compared to WT while the 5‐HTP substituted mutant acquired an energy sink along the hopping path. The W96F and the 5‐HTP mutants therefore represent two different cases of catalytic suppression. 5‐HTP acts as a hole sink that funnels the hole away from the N‐terminal Mn ion, preventing it from forming Mn(III), and explaining the mutant enzyme's lack of activity. Residual activity for W96F was explained by the action of the auxiliary tryptophan residues W171 and W348 which can provide a secondary hole hopping pathway (Pastore et al., 2021). This is not possible for the 5‐HTP substituted protein because those pathways are short‐circuited by the hole sink on the 5‐HTP residue. Rather, we assume that any residual activity observed for the 5‐HTP mutant is due to incomplete incorporation of 5‐HTP at position W96.

Typical tryptophan radicals show broad EPR spectra spread over up to 60 G at X‐band with usually well resolved fine structure owing to the relatively large hyperfine interactions of the indole nitrogen and the protons attached to carbons 2, 4, 6, and the β–carbon (Bernini et al., 2012; Bernini et al., 2013; Lendzian et al., 1996; Miller et al., 2003; Pogni et al., 2005; Pogni et al., 2006; Pogni et al., 2007; Stoll et al., 2011; Svistunenko et al., 2011). Please note that in this contribution we follow the IUPAC recommendations for the numbering of carbon atoms in the indole ring, which is slightly different from that used in the older literature (see Data S1, Figure SI‐5) (1984). The g‐anisotropy of both neutral and cation radicals of TRP is small and remains unresolved in the X‐band (Davis et al., 2018; Pogni et al., 2007). Hence, the main features leading to any spectral splittings are the large nitrogen and proton hyperfine couplings due to the unpaired electron spin densities on the indole N, carbons C2, C4, C6, and the β–carbon. Additional unresolved hyperfine coupling to other protons leads to inherent peak‐to‐peak linewidths in typical EPR spectra of the order of 10 to 15 G (Lendzian et al., 1996; Pogni et al., 2005; Pogni et al., 2006; Pogni et al., 2007).

The most striking observation about the EPR spectra in Figures 2 and 3 is the large linewidth of the 5‐HTP˙ radical which is almost an order of magnitude larger than what may be expected from the isolated radical in solution (Davis et al., 2018). The linewidth of the spectrum decreases only marginally from 119 G to 114 G upon partial deuteration of the 5‐HTP. However, its fine structure is better resolved for the deuterated case and proves that the radical is located on 5‐HTP. Clearly, the overall linewidth is not determined by the hyperfine coupling constants of the hydrogens on carbons 4, 6, or 7. Unresolved superhyperfine interaction with the nearest Mn(II) center can safely be excluded from consideration given the distance of 10 Å and the correspondingly small spin density on the Mn nucleus. The relevant coupling strengths were estimated by DFT to be about 6 mG at most, that is, orders of magnitude smaller than the hyperfine coupling constants with nuclei within the radical itself (see Data S1, Table SI‐9).

The best explanation for the observed linewidth is spin–spin coupling between the unpaired electron spins on the 5‐HTP˙ radical and the neighboring Mn(II) ions. This type of effect is well known and leads to significant line broadening (Cox et al., 2010). Dipolar coupling between two spin‐1/2 radicals leads to energetic shifts of the order of 78 MHz/r3 with r the distance in nm between the radicals or approximately 28 G/r3 (Eaton & Eaton, 2005). This value would have to be multiplied by approximately a factor of 2 when the interacting spin is increased from 1/2 to 5/2 because of the dependence of the dipolar coupling on the total spin. Since the N‐terminal Mn(II) is approximately 10 Å center‐to‐center distance away from W96 and the C‐terminal Mn(II) approximately 12.3 Å, a broad EPR line of the order of 120 G for the radical is entirely plausible. Our broken‐symmetry DFT calculations overestimate the isotropic exchange coupling between the 5‐HTP˙ neutral radical and the neighboring Mn(II) ions but yield the correct order of magnitude.

To our knowledge, this is the first use of 5‐HTP applied to the study of an electron transfer pathway in a redox‐active, natively assembled protein complex. It supports the importance of W96 for catalysis in OxDC and leads to the first OxDC mutant protein with a stable carbon‐based radical in the resting state. 5‐HTP acts as a hole sink and allows to give a lower estimate for the standard potential of the N‐terminal Mn(II)/Mn(III) couple of 740 mV against NHE at pH 4, the pH of highest catalytic activity.

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1. Materials

All chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific unless otherwise stated. Q5 polymerase was purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, Massachusetts), primers were ordered from IDT DNA (Coralville, Iowa), and Sanger sequencing was performed by Genewiz (South Plainfield, NJ). Primer sequences can be found in the Data S1, Table SI‐1. DH5α cells from New England Biolabs were used to amplify plasmid DNA. Miniprep kits for isolating DNA were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). The materials and methods for UAA incorporation of 5‐HTP are documented by Italia et al. (2017). Briefly, the original pET32A vector encoded for OxDC was modified to have a TGA site introduced at position 96, the t7 promoter was replaced by a ptac promoter, and a TAA stop codon was inserted at the end of the His6‐tag.

4.2. Expression and purification

The 5‐HTP mutant was purified using established protocols from the literature (Italia et al., 2017). Cultures were grown in the presence of 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol, 50 μg/ml ampicillin, and 100 μg/ml spectinomycin. Cells were grown to an optical density of 0.5 at 600 nm in Luria‐Bertani broth at 37°C followed by heat‐shocking at 42°C for 15 min. After heat shocking, MnCl2 was added to the LB broth until the concentration of MnCl2 reached 4.6 mM. Isopropyl β‐d‐1‐thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and l‐arabinose were added for a final solution concentration of 0.8 mM and 3.33 mM, respectively. Finally, 5‐HTP was added for a final concentration of 1 mM. Cells were grown for four more hours before being centrifuged in a Sorvall RC 6 centrifuge equipped with a SLA‐3000 rotor at 6000 revolutions per minute (6080×g) for 18 min at 4°C. Cell pellets were stored at −80°C until further processing. Partially deuterated d4,d6,d7‐(5‐HTP) was purchased from CDN Isotopes (Quebec, Canada) and was used at induction concentrations of 0.2 mM and 0.5 mM in separate experiments. Cell pellets were resuspended in 40 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM tris, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole at pH 7.5) and lysed by sonication. Cell lysate was incubated with nickel‐NTA resin for 2 h at 4°C and washed with 8 column volumes of wash buffer (20 mM tris, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole at pH 8.5). OxDC was collected from fractions as the resin was washed with elution buffer (20 mM tris, 500 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, at pH 8.5). Imidazole is removed through standard dialysis with 50 mM tris and 500 mM NaCl at pH 8.5. Chelex resin from Bio‐Rad was used to remove free metal cations in solution and Amicon filters with a 30 kDa molecular weight cut‐off were used to concentrate OxDC. Protein concentration was determined with the Bradford assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

4.3. Mn content analysis

Aliquots of OxDC (200–300 μl) were diluted to 1.5 ml with chelex‐treated dialysis buffer, followed by dilution to 10 ml with de‐ionized water and the addition of 200 μl of trace‐metal grade nitric acid. The samples were sent to the University of Georgia Center for Applied Isotope Studies for ICP‐MS analysis of metal content.

4.4. Steady‐state turnover

Decarboxylation was studied through an endpoint coupled assay in which the product, formate, is indirectly measured via the production of NADH after incubation with formate dehydrogenase (FDH) and NAD+. The first step involved incubation of enzyme in a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube with 0.004% (m/v) triton‐X, 612 μM ortho‐phenylenediamine (O‐PDA), 500 mM NaCl, 50 mM poly buffer (50 mM each of citrate, piperazine, tris, bis‐tris) at pH 4.2, and varying concentrations of potassium oxalate at 25°C for a total volume of 104 μl. The reaction was quenched by the addition of 10 μl of 1 M NaOH. Fifty‐five microliters of this mixture was mixed with 945 μl of an aqueous solution containing 0.0004% (m/v) FDH, 50 mM K2HPO4 (pH 7.8), and 1.5 mM NAD+ with overnight incubation at 37°C. The amount of NADH produced was measured by its absorption at 340 nm (ε 340 = 6220 M−1 cm−1) (Bernofsky & Wanda, 1982; Horecker & Kornberg, 1948), which can be correlated to the amount of formate produced. A standard plot is generated from known concentrations of formate by linear regression to quantify how much formate was produced. Kinetic parameters were determined by modeling the formate concentrations vs. oxalate concentration with Michaelis–Menten kinetics using Grace software.

4.5. Trypsin digestion LC–MS/MS for labeling efficiency

5‐HTP substituted enzyme was precipitated with a 4:1 v/v mixture of acetone and nanopure water at −20°C overnight. The precipitant was centrifuged at 14,000 revolutions per minute at 4°C and the supernatant was decanted. Two more washes of 4:1 acetone‐water solution were used, samples were centrifuged, and decanted as previously stated. The protein pellet was air‐dried for 30 min at room temperature for residual solution to evaporate. The protein pellet was stored at −20°C until further use. Three times the sample volume of rapid digestion buffer (provided along with the digestion kit from Promega) was added to the samples. The sample was incubated at 56°C with 1 μl of dithiothreitol (DTT) solution (0.1 M in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate) for 30 min prior to the addition of 0.54 μl of 55 mM iodoacetamide in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Iodoacetamide was incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. The trypsin was prepared fresh as 1 μg/ml in the rapid digestion buffer. One microliter of enzyme was added and the samples were incubated at 56°C for 1 h, the digestion was stopped by the addition of 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid. Positive mode LC–MS/MS was performed with a Q Exactive (QE) HF Orbitrap mass spectrometer equipped with an EASY Spray nanospray source. The LC system used was an UltiMate™ 3000 RSLC nano. The mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid and acetic acid in water and the mobile phase B was acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid in water. Five microliters of the digested peptides was injected onto a 2 cm C18 column and washed with mobile phase A. The injector port was switched to inject, and the peptides were eluted off the trap onto a 25 cm C18 column for separation. Peptides were eluted directly off the column into the QE system using a gradient of 2–80% of mobile phase B with a flow rate of 300 nl/min. The total run time was 1 h. The EASY Spray source operated with a spray voltage of 1.5 kV and a capillary temperature of 200°C. The scan sequence of the mass spectrometer was based on the TopTen™ method. All MS/MS spectra were analyzed using Sequest (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA; version IseNode in Proteome Discoverer 2.4.0.305). Sequest was set up to search a home‐built library containing the sequence of interest plus common contaminates assuming the digestion enzyme trypsin. Sequest was searched with a fragment ion mass tolerance of 0.020 Da and a parent ion tolerance of 10.0 ppm. Carbamidomethyl of cysteine was specified in Sequest as a fixed modification. Met‐loss of methionine, met‐loss + acetyl of methionine, oxidation of methionine and acetyl of the n‐terminus were specified in Sequest as variable modifications. Oxidation of tryptophan and the deuterated form was included in the variable modifications.

4.6. CW‐EPR spectroscopy

EPR spectra were collected on a Bruker Elexsys E500 spectrometer. The ER4116 Dual Mode resonator was used for perpendicular mode and parallel mode spectra at 6 K. The frequency for perpendicular mode was 9.6506 GHz and the frequency for parallel mode was 9.4067 GHz. For wide spectral sweeps the center field was chosen as 3550 G with a sweep width of 7000 G. Further parameters are listed for each separate figure. For EPR experiments the d4,d6,d7‐(5‐HTP) substituted enzyme was expressed with 0.5 mM UAA concentration during induction.

4.7. DFT calculations

All calculations were performed with the Orca 5 quantum chemistry software (Neese et al., 2020). Geometry optimizations of the large structural model (see Figure 4) were carried out using the BP86 (Becke, 1988; Perdew, 1986) functional with D3BJ dispersion corrections (Grimme et al., 2010; Grimme et al., 2011) using the resolution of identity (RI) approximation. The conductor‐like polarizable continuum model (CPCM) (Barone & Cossi, 1998) with dielectric constant ε = 6 was applied in optimizations. Single‐point calculations on the optimized structure were performed using the TPSSh functional (Staroverov et al., 2003), which has been proven reliable for the calculation of magnetic properties of transition metal complexes, with the chain‐of‐spheres (RIJCOSX) approximation (Neese et al., 2009) to exact exchange. Scalar relativistic effects were treated with the zeroth order regular approximation (ZORA) (van Lenthe et al., 1993; van Lenthe et al., 1994; van Wüllen, 1998). The ZORA‐recontracted (Pantazis et al., 2008) def2‐TZVP(−f) basis sets (Weigend & Ahlrichs, 2005) were used for all atoms. For the Coulomb fitting the SARC/J auxiliary basis sets were used (Pantazis et al., 2008; Weigend, 2006). For the calculation of the proton and nitrogen hyperfine coupling tensors of the tryptophan radicals, the Mn ions in the model were substituted with diamagnetic Zn ions. In order to estimate the superhyperfine coupling between the 5HTP radical and the Mn ions the Zn ions were assigned a nuclear spin of 5/2 with the gyromagnetic ratio of Mn. For the H atoms the EPR‐II basis set (Rega et al., 1996) was used and for N the ZORA‐def2‐TZVP(−f) basis set was used with decontracted s‐functions and three additional tight s‐functions obtained by scaling the innermost exponent of the original basis by 2.5, 6.25, and 15.625 (Neese, 2002). “Picture‐change” effects due to the use of the scalar relativistic Hamiltonian were also taken into account. The spin‐orbit coupling operator was constructed to include one‐electron terms, to compute the Coulomb term using the RI approximation and to include exchange via one‐center exact integrals including the spin–other orbit interaction (SOCFlags 1,3,3,0 in Orca convention). For the calculation of the isotropic exchange coupling constants between the Mn(II) ions and the neutral 5‐HTP˙ radical the B3LYP functional (Becke, 1988; Becke, 1993; Lee et al., 1988) was used along with VeryTightSCF convergence criteria.

The VIE was calculated as described by Pastore et al. for the 5‐HTP dimer stack (Pastore et al., 2021).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Anthony John Pastore: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); investigation (lead); visualization (supporting); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (equal). Alvaro Montoya: Investigation (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Manasi Kamat: Investigation (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Kari B. Basso: Data curation (equal); funding acquisition (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). James S. Italia: Methodology (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Abhishek Chatterjee: Funding acquisition (equal); methodology (lead); writing – review and editing (equal). Maria Drosou: Investigation (supporting); visualization (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal). Dimitrios A. Pantazis: Conceptualization (equal); funding acquisition (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Alexander Angerhofer: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); funding acquisition (equal); project administration (lead); supervision (lead); visualization (lead); writing – original draft (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting Information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the NSF (CHE‐2002950 to A.A.) and by the NIH (R35GM136437 to A.C., and S10 OD021758‐01A1 to K.B.B.). D.A.P. and M.D. acknowledge support by the Max Planck Society.

Pastore AJ, Montoya A, Kamat M, Basso KB, Italia JS, Chatterjee A, et al. Selective incorporation of 5‐hydroxytryptophan blocks long range electron transfer in oxalate decarboxylase. Protein Science. 2023;32(1):e4537. 10.1002/pro.4537

Review Editor: John Kuriyan

Funding information National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Numbers: R35GM136437, S10 OD021758‐01A1; National Science Foundation, Grant/Award Number: CHE‐2002950; Max Planck Society

Contributor Information

Abhishek Chatterjee, Email: abhishek.chatterjee@bc.edu.

Dimitrios A. Pantazis, Email: dimitrios.pantazis@kofo.mpg.de.

Alexander Angerhofer, Email: alex@chem.ufl.edu.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request from the authors.

REFERENCES

- Addy PS, Italia JS, Chatterjee A. An oxidative bioconjugation strategy targeted to a genetically encoded 5‐hydroxytryptophan. Chembiochem. 2018;19:1375–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae JH, Rubini M, Jung G, Wiegand G, Seifert MHJ, Azim MK, et al. Expansion of the genetic code enables design of a novel “gold” class of green fluorescent proteins. J Mol Biol. 2003;328:1071–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone V, Cossi M. Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model. J Phys Chem A. 1998;102:1995–2001. [Google Scholar]

- Becke AD. Density‐functional exchange‐energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys Rev A At Mol Opt Phys. 1988;38:3098–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke AD. Density‐functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5648–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bernini C, Pogni R, Basosi R, Sinicropi A. The nature of tryptophan radicals involved in the long‐range electron transfer of lignin peroxidase and lignin peroxidase‐like systems: insights from quantum mechanical/molecular mechanics simulations. Proteins. 2012;80:1476–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernini C, Andruniów T, Olivucci M, Pogni R, Basosi R, Sinicropi A. Effects of the protein environment on the spectral properties of tryptophan radicals in Pseudomonas aeruginosa azurin. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:4822–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernofsky C, Wanda SY. Formation of reduced nicotinamide adenine‐dinucleotide peroxide. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:6809–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boknevitz K, Italia JS, Li B, Chatterjee A, Liu SY. Synthesis and characterization of an unnatural boron and nitrogen‐containing tryptophan analogue and its incorporation into proteins. Chem Sci. 2019;10:4994–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buddha MR, Crane BR. Structure and activity of an aminoacyl‐tRNA synthetase that charges tRNA with nitro‐tryptophan. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:274–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budisa N, Rubini M, Bae JH, Weyher E, Wenger W, Golbik R, et al. Global replacement of tryptophan with aminotryptophans generates non‐invasive protein‐based optical pH sensors. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:4066–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg MJ, Goodsell JL, Twahir UT, Bruner SD, Angerhofer A. The structure of oxalate decarboxylase at its active pH. bioRxiv. 2018;426874. [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Svedružić D, Ozarowski A, Walker L, Yeagle G, Britt RD, et al. EPR spectroscopic characterization of the manganese center and a free radical in the oxalate decarboxylase reaction – identification of a tyrosyl radical during turnover. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52840–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MCY, Yee CS, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. Site‐specific replacement of a conserved tyrosine in ribonucleotide reductase with an aniline amino acid: a mechanistic probe for a redox‐active tyrosine. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:16702–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley RB, Feldman JL, Driggers CM, Bundy TA, Stokes AL, Karplus PA, et al. Structural basis of improved second‐generation 3‐nitro‐tyrosine tRNA synthetases. Biochemistry. 2014;53:1916–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (1984). Nomenclature and symbolism for amino‐acids and peptides ‐ recommendations 1983. Eur J Biochem. 138:9–37. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb07877.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox N, Ogata H, Stolle P, Reijerse E, Auling G, Lubitz W. A Tyrosyl‐Dimanganese Coupled Spin System is the Native Metalloradical Cofactor of the R2F Subunit of the Ribonucleotide Reductase of Corynebacterium ammoniagenes . J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11197–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis I, Koto T, Terrell JR, Kozhanov A, Krzystek J, Liu AM. High‐frequency/high‐field electron paramagnetic resonance and theoretical studies of tryptophan‐based radicals. J Phys Chem A. 2018;122:3170–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre D, Chin JW. Reprogramming the genetic code. Nat Rev Genet. 2021;22:169–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Measurement of distances between electron spins using pulsed EPR. In: Eaton SR, Eaton GR, Berliner LJ, editors. Biomedical EPR, part B: methodology, instrumentation, and dynamics. US: Springer; 2005. p. 223–36. [Google Scholar]

- Englert M, Nakamura A, Wang YS, Eiler D, Söll D, Guo LT. Probing the active site tryptophan of Staphylococcus aureus thioredoxin with an analog. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:11061–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficaretta ED, Wrobel CJJ, Roy SJS, Erickson SB, Italia JS, Chatterjee A. A robust platform for unnatural amino acid mutagenesis in E. coli using the bacterial tryptophanyl‐tRNA synthetase/tRNA pair. J Mol Biol. 2022;434:167304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S, Antony J, Ehrlich S, Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT‐D) for the 94 elements H‐Pu. J Chem Phys. 2010;132:154104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S, Ehrlich S, Goerigk L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J Comput Chem. 2011;32:1456–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilaire MR, Ahmed IA, Lin CW, Jo H, DeGrado WF, Gai F. Blue fluorescent amino acid for biological spectroscopy and microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:6005–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horecker BL, Kornberg A. The extinction coefficients of the reduced band of pyridine nucleotides. J Biol Chem. 1948;175:385–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries K, Dryhurst G. Electrochemical oxidation of 5‐hydroxytryptophan in acid‐solution. J Pharm Sci. 1987;76:839–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries KA, Wrona MZ, Dryhurst G. Electrochemical and enzymatic oxidation of 5‐hydroxytryptophan. J Electroanal Chem. 1993;346:377–403. [Google Scholar]

- Imaram W, Saylor BT, Centonze CP, Richards NGJ, Angerhofer A. EPR spin trapping of an oxalate‐derived free radical in the oxalate decarboxylase reaction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:1009–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Italia JS, Addy PS, Wrobel CJJ, Crawford LA, Lajoie MJ, Zheng Y, et al. An orthogonalized platform for genetic code expansion in both bacteria and eukaryotes. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:446–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic SV, Steenken S, Simic MG. One‐electron reduction potentials of 5‐indoxyl radicals. A pulse radiolysis and laser photolysis study. J Phys Chem. 1990;94:3583–8. [Google Scholar]

- Just VJ, Stevenson CEM, Bowater L, Tanner A, Lawson DM, Bornemann S. A closed conformation of Bacillus subtilis oxalate decarboxylase OxdC provides evidence for the true identity of the active site. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19867–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Development of the Colle‐Salvetti correlation‐energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys Rev B. 1988;37:785–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendzian F, Sahlin M, MacMillan F, Bittl R, Fiege R, Pötsch S, et al. Electronic structure of neutral tryptophan radicals in ribonucleotide reductase studied by EPR and ENDOR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8111–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi L, Kissner R, Nauser T, Koppenol WH. Electrode potentials of L‐tryptophan, L‐tyrosine, 3‐nitro‐L‐tyrosine, 2,3‐difluoro‐L‐tyrosine, and 2,3,5‐trifluoro‐L‐tyrosine. Biochemistry. 2016;55:2849–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manandhar M, Chun E, Romesberg FE. Genetic code expansion: inception, development, commercialization. J Am Chem Soc. 2021;143:4859–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meichsner SL, Kutin Y, Kasanmascheff M. In‐cell characterization of the stable tyrosyl radical in E. coli ribonucleotide reductase using advanced EPR spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2021;60:19155–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkel PB, Luo P, Dinnocenzo JP, Farid S. Accurate oxidation potentials of benzene and biphenyl derivatives via electron‐transfer equilibria and transient kinetics. J Org Chem. 2009;74:5163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Kehl A, Cui C, Reichardt FAK, Hecker F, Funk LM, et al. 19F electron‐nuclear double resonance reveals interaction between redox‐active tyrosines across the alpha/beta interface of E. coli ribonucleotide reductase. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144:11270–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JE, Grădinaru C, Crane BR, Di Bilio AJ, Wehbi WA, Un S, et al. Spectroscopy and reactivity of a photogenerated tryptophan radical in a structurally defined protein environment. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14220–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moomaw EW, Angerhofer A, Moussatche P, Ozarowski A, García‐Rubio I, Richards NGJ. Metal dependence of oxalate decarboxylase activity. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6116–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F. Prediction and interpretation of the 57Fe isomer shift in Mössbauer spectra by density functional theory. Inorg Chim Acta. 2002;337:181–92. [Google Scholar]

- Neese F, Wennmohs F, Becker U, Riplinger C. The ORCA quantum chemistry program package. J Chem Phys. 2020;152:224108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F, Wennmohs F, Hansen A, Becker U. Efficient, approximate and parallel Hartree–Fock and hybrid DFT calculations. A ‘chain‐of‐spheres’ algorithm for the Hartree–Fock exchange. Chem Phys. 2009;356:98–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ohler A, Long H, Ohgo K, Tyson K, Murray D, Davis A, et al. Synthesis of redox‐active fluorinated 5‐hydroxytryptophans as molecular reporters for biological electron transfer. Chem Commun. 2021;57:3107–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis DA, Chen X‐Y, Landis CR, Neese F. All‐electron scalar relativistic basis sets for third‐row transition metal atoms. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4:908–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastore AJ, Teo RD, Montoya A, Burg MJ, Twahir UT, Bruner SD, et al. Oxalate decarboxylase uses electron hole hopping for catalysis. J Biol Chem. 2021;297:100857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastore AJ, Ficaretta E, Chatterjee A, Davidson VL. Substitution of the sole tryptophan of the cupredoxin, amicyanin, with 5‐hydroxytryptophan alters fluorescence properties and energy transfer to the type 1 copper site. J Inorg Biochem. 2022;234:111895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew JP. Density‐functional approximation for the correlation energy of the inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 1986;33:8822–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogni R, Baratto MC, Giansanti S, Teutloff C, Verdin J, Valderrama B, et al. Tryptophan‐based radical in the catalytic mechanism of versatile peroxidase from Bjerkandera adusta . Biochemistry. 2005;44:4267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogni R, Baratto MC, Teutloff C, Giansanti S, Ruiz‐Dueñas FJ, Choinowski T, et al. A tryptophan neutral radical in the oxidized state of versatile peroxidase from Pleurotus eryngii ‐ a combined multifrequency EPR and density functional theory study. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9517–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogni R, Teutloff C, Lendzian F, Basosi R. Tryptophan radicals as reaction intermediates in versatile peroxidases: multifrequency EPR, ENDOR and density functional theory studies. Appl Magn Reson. 2007;31:509–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt EA, Ho C. Incorporation of fluorotryptophane into proteins of Escherichia‐coli . Biochemistry. 1975;14:3035–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravichandran KR, Liang L, Stubbe J, Tommos C. Formal reduction potential of 3,5‐Difluorotyrosine in a structured protein: insight into multistep radical transfer. Biochemistry. 2013;52:8907–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravichandran KR, Zong AB, Taguchi AT, Nocera DG, Stubbe J, Tommos C. Formal reduction potentials of difluorotyrosine and trifluorotyrosine protein residues: defining the thermodynamics of multistep radical transfer. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:2994–3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RCSB PDB . 5VG3: Structure of oxalate decarboxylase from Bacillus subtilis at pH 4.6. RCSB PDB Protein Data Bank; 2017. 10.2210/pdb5VG3/pdb [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reece SY, Seyedsayamdost MR. Long‐range proton‐coupled electron transfer in the Escherichia coli class Ia ribonucleotide reductase. In: Lippard SJ, Berg JM, editors. Essays Biochem. London: Portland Press Ltd; 2017. p. 281–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rega N, Cossi M, Barone V. Development and validation of reliable quantum mechanical approaches for the study of free radicals in solution. J Chem Phys. 1996;105:11060–7. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D, Besley NA, O'Shea P, Hirst JD. Calculating the fluorescence of 5‐hydroxytryptophan in proteins. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:14521–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JBA, Senear DF, Waxman E, Kombo BB, Rusinova E, Huang YT, et al. Spectral enhancement of proteins: biological incorporation and fluorescence characterization of 5‐hydroxytryptophan in bacteriophage λ cI repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:12023–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Seidel R, Kumar G, Bradforth SE. Exploring redox properties of aromatic amino acids in water: contrasting single photon vs resonant multiphoton ionization in aqueous solutions. J Phys Chem B. 2018;122:3723–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor BT, Reinhardt LA, Lu ZB, Shukla MS, Nguyen L, Cleland WW, et al. A structural element that facilitates proton‐coupled electron transfer in oxalate decarboxylase. Biochemistry. 2012;51:2911–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shandell MA, Tan ZP, Cornish VW. Genetic code expansion: a brief history and perspective. Biochemistry. 2021;60:3455–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh‐Blom A, Hughes RA, Ellington AD. An amino acid depleted cell‐free protein synthesis system for the incorporation of non‐canonical amino acid analogs into proteins. J Biotechnol. 2014;178:12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staroverov VN, Scuseria GE, Tao J, Perdew JP. Comparative assessment of a new nonempirical density functional: molecules and hydrogen‐bonded complexes. J Chem Phys. 2003;119:12129–37. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll S, Schweiger A. EasySpin, a comprehensive software package for spectral simulation and analysis in EPR. J Magn Reson. 2006;178:42–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll S, Shafaat HS, Krzystek J, Ozarowski A, Tauber MJ, Kim JE, et al. Hydrogen bonding of tryptophan radicals revealed by EPR at 700 GHz. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:18098–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svistunenko DA, Adelusi M, Dawson M, Robinson P, Bernini C, Sinicropi A, et al. Computation informed selection of parameters for protein radical EPR spectra simulation. Stud Univ Babes‐Bolyai Chem. 2011;56:135–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner A, Bornemann S. Bacillus subtilis YvrK is an acid‐induced oxalate decarboxylase. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5271–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner A, Bowater L, Fairhurst SA, Bornemann S. Oxalate decarboxylase requires manganese and dioxygen for activity – overexpression and characterization of Bacillus subtilis YvrK and YoaN. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43627–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twahir UT, Ozarowski A, Angerhofer A. Redox cycling, pH dependence, and ligand effects of Mn(III) in oxalate decarboxylase from Bacillus subtilis . Biochemistry. 2016;55:6505–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lenthe E, Baerends EJ, Snijders JG. Relativistic regular two‐component Hamiltonians. J Chem Phys. 1993;99:4597–610. [Google Scholar]

- van Lenthe E, Baerends EJ, Snijders JG. Relativistic total energy using regular approximations. J Chem Phys. 1994;101:9783–92. [Google Scholar]

- van Wüllen C. Molecular density functional calculations in the regular relativistic approximation: method, application to coinage metal diatomics, hydrides, fluorides and chlorides, and comparison with first‐order relativistic calculations. J Chem Phys. 1998;109:392–9. [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F, Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: design and assessment of accuracy. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2005;7:3297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F. Accurate coulomb‐fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2006;8:1057–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CY, Eftink MR. Biosynthetic incorporation of tryptophan analogues into staphylococcal nuclease: effect of 5‐hydroxytryptophan and 7‐azatryptophan on structure and stability. Protein Sci. 1997;6:689–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee EF, Dzikovski B, Crane BR. Tuning radical relay residues by proton management rescues protein electron hopping. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:17571–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young DD, Schultz PG. Playing with the molecules of life. ACS Chem Biol. 2018;13:854–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting Information.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.