Abstract

Lauraceae is a large family with significant economic and medicinal value. Bioactive ingredients from Lauraceae plants have contributed greatly to medicines, food nutrients and fine chemical products. In recent years, quite a few sesquiterpenes and diterpenes with unique structures have been achieved from Lauraceae and their potential benefits are embodied in a wide range of health areas. To our knowledge, there is no review to summarizes these constituents and their biological effects systematically. This current work aims to classify and ascribe the structural types and bioactivities of the identified sesquiterpenes and diterpenes. Herein, a total of 362 sesquiterpenes and 69 diterpenes were comprehensively complied. The various bioactivities could be recognized as cytotoxicity, anti-proliferation and/or anti-apoptosis, anti-inflammation, anti-oxidation, anti-bacterium, etc. This updated data could serve as a catalysis of these sesquiterpenes and diterpenes for the future medical and industrial applications.

Keywords: Lauraceae, Sesquiterpenes, Diterpenes, Traditional application, Biological activities

Lauraceae; Sesquiterpenes; Diterpenes; Traditional application; Biological activities.

1. Introduction

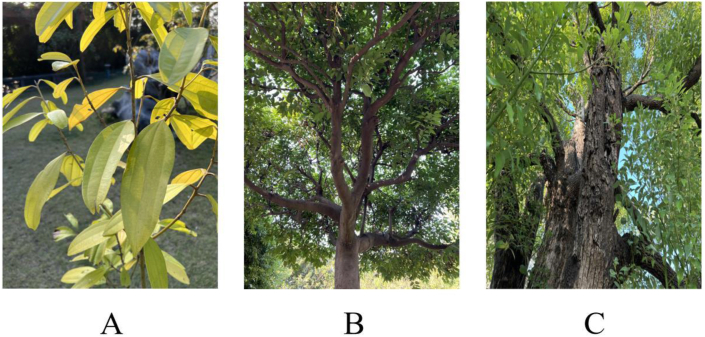

Lauraceae, a large family belonging to Magnoliidae, comprises 2000–2500 species grouped to 45 genera. Most plants of Lauraceae are pantropic evergreen arbor, distributed natively in mountain and rainforests of southern and southeastern Asian, Australia, Africa and Southern America (Figure 1). In China, there are 25 genera, 445 species spreading across the middle and low altitude mountains from Southwest to South region. Among them, Sinosassafras and Sinopora are endemic to China, while Laurus and Persea are the commercially cultivated genera (Figure 2A–C) [1].

Figure 1.

Distribution of Lauraceae plants around the world (the red zone, original map downloaded from http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn/index.html).

Figure 2.

Three representative Lauracea plants in China. (A) Cinnamomum cassia Presl; (B) Cinnamomum burmannii (Nees) BL; (C) Cinnamomum camphora (L.); Presl.

Due to the multifaceted importance of Lauraceae plants, a broad range of studies on comprehensive phytochemical and bioactive of Lauraceae plants are carried out. Our literature retrieval manifested that the genera of Cinnamomum, Persea, Laurus, Litsea, Lindera, Neolitsea and Ocotea were intensively studied, while Nectandra, Caryodaphnosis, Beilschmiedia, Machilus, Crytocarya and Pleurothyrium barely had a handful of scientific investigations. Terpenes (monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes and diterpenes), phenylpropanoids, polyphenols (lignans, flavonoids, dibenzocycloheptanoids, coumarins and their glycosides), alkaloids, polysaccharides and aliphatics [2, 3, 4, 5] encompassed the predominant constituents of this family, and which pharmacological activities covering the antioxidation, antibiosis, anti-inflammation, cytotoxicity, neuroprotection, hepatoprotection, cytokine modulation and pain soothing [6, 7, 8, 9]. Although phenylpropanoids and polyphenols are the perceived best-known ingredients, sesquiterpenes and diterpenes have become the emerging representative constituents, as for their various unprecedent structures, multiple health-beneficial bioactivities and potential chemotaxonomic significance in the phytology study.

Up to now, there are several reviews concluded the traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of genus Cinnamomum, C. cassia or C. verum [5, 10, 11]; but no comprehensive review specially focuses on the characteristic sesquiterpenes and diterpenes covering the whole family, even though their quantity and variety are greatly enriched in recent years. Herein, we presented a compilation aimed to systematically classify the structural type of sesquiterpenes and diterpenes isolated from Lauraceae and figure out their potential beneficials to human health. Databases and primary sources including SciFinder, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, PubMed, CNKI, PhD and MSc dissertations were conducted with the query words “pharmacological”, “phytochemistry”, “sesquiterpenes”, “diterpenes”, “healthy”, “traditional usage”, “medicinal” and the names of each genera and species of Lauraceae, etc. We look forward to this article can provide some valuable scientific reference for the further studies and utilization of these functional components.

2. Traditional application

Lauraceae plants possess great economic value, extend beyond the nutritional, industrial and medicinal applications. Avocado or called as alligator pears, is a kind of green- to purple-skinned pulpy nutty fruit of Persea americana which is rich in healthy fats and oils and recognized as beneficial for all ages [12]. The stem woods of some high trees from Ocotea, Nectandra, Persea [13], Beilschmiedia [14], Machilus and Phoebe [15] are precious timbers for architecture, shipbuilding and home furnishing. Oil-rich barks, leaves and fruits of Cinnamomum, Litsea, Lindera, Laurus, Neolitsea and Cryptocarya species are applied widely as spices, perfume, natural preservatives, pesticides, agrochemicals, disinfectants, as well as the corrective agents in food, beverage and cosmetics [11, 16, 17, 18]. Moreover, as the important industrial raw materials, natural borneol can be acquired from Cinnamomum camphora [19] or C. japonicum [20] and camphor is found in C. camphora [19] and C. osmophloeum [21].

In terms of the officinal purpose, the barks and twigs of Cinnamomum cassia, the root tubers of Lindera aggregata and the fruits of Litsea cubeba have long been used in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) for dispersing body cold, relieving stomach pain, treating of kidney disease, impotence, dysmenorrhea, diabetes and some inflammatory disorders [22, 23, 24, 25]. On the basis of folk usage, people further find out that the essential oil distilled from C. cassia is of significant antibacterial, spasmolytic and sedative activities [26]. Some representative classic TCM prescriptions and their functions with the above-mentioned herbs are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of classic TCM prescriptions of Lauraceae plants.

| Herbal | Prescription name | Traditional and clinical uses | Documentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barks of C. cassia | You Gui Pills | Treating deficiency of kidney Yang, sour and cold waist and knees, low spirit, fear of cold, impotence, spermatorrhea, frequent and clear urination | Jing Yue Quan Shu |

| Su Zi Jiang Qi Soup | Treating the reducing of Qi and relieving asthma, stuffy chest and diaphragm, eliminating phlegm and relieving cough | Tai Ping Hui Min He Ji Ju Fang | |

| Shi Quan Da Bu Soup | Treating lack of Qi and blood, fatigue, cough, ulcers and ulcers, metrorrhagia and leakage | Tai Ping Hui Min He Ji Ju Fang | |

| Gui Fu Du Zhong Soup | Treating cold, backache, green tongue, contraction of scrotum and trembling | Hui Yue Yi Jing | |

| Twigs of C. cassia | Shen Qi Pills | Treating backache, soft feet, adverse urination or excessive urination, impotence, premature ejaculation, light and fat tongue | Jin Gui Yao Lue |

| Gui Zhi Fu Zi Soup | Dispel wind, warm meridians, help Yang and remove dampness | Shang Han Lun | |

| Ma Huang Soup | Treating cold and aversion, fever, headache and body pain, panting without sweat | Shang Han Lun | |

| Root tubers of Lindera aggregata | Si Mo Soup | Treating Qi descending, distended and stuffy of chest and diaphragm, short of breath | Ji Sheng Fang |

| Suo Quan Pills | Nourishing Yin and kidney, treating frequency of urination and nocturnal enuresis caused by kidney deficiency | Fu Ren Liang Fang | |

| Ge Xia Zhu Yu Soup | Promoting blood circulation and removing blood stasis, treating accumulation of mass caused by blood stasis | Yi Lin Gai Cuo | |

| Fruits of L. cubeba | Bi Cheng Qie Powder | Treating stabbing pain and cold on abdomen and heart, soft limbs | Bian Que Xin Shu |

| Bi Cheng Qie Pills | Treating weakness of spleen and stomach, discomfort of chest and diaphragm, anorexia | Ji Sheng Fang |

3. Phytochemistry

3.1. Sesquiterpenoids

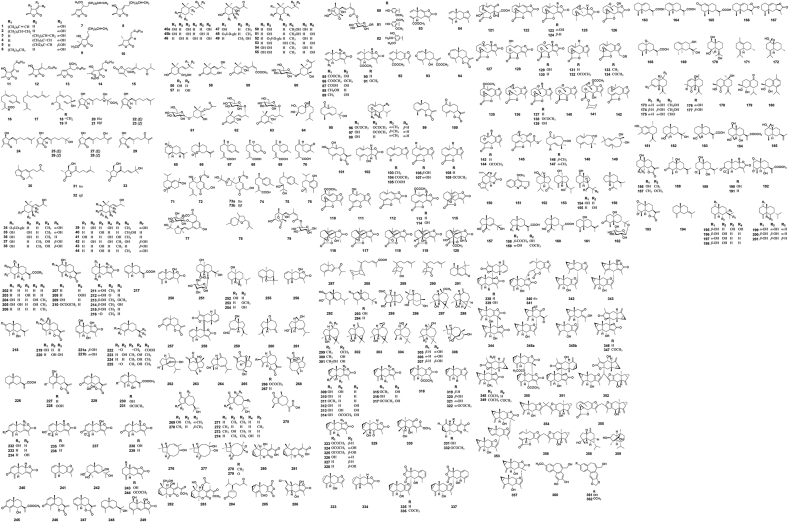

To date, a total of 362 sesquiterpenes had been acquired from the plant materials of 12 genera and 44 species in Lauraceae family. Among them, megastigmane-, germacrane-, eudesmane- and lindenane-type sesquiterpenoids account for a fairly large proportion. Besides, a number of dimers and polymers discovered recently were further amplified the diversity of Lauraceae sesquiterpenoids [27, 28]. Hydroxyl, carbonyl, methyl, glycosyl and phenzyl substitutions with different configurations, as well as double bonds or epoxy groups are found to be the most common structural characteristics in sesquiterpenes. These compounds exhibit the extraordinary chemo-diversity and can be sketchily classified into acyclic, monocyclic, bicyclic and tricyclic system in the light of carbon rings, or assigned to sesquiterpene alcohols, aldehydes and lactones according their oxidation degree. Their detailed skeleton types, names, plant resources, applied botanical parts and chemical structures are listed in Table 2 and Figure 3, respectively.

Table 2.

Sesquiterpenoids from the family Lauraceae.

| No. | Name | Species | Botanical parts | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chain sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| Butanolides | ||||

| 1 | (+)-(2E,3R,4S)-2-(Dodec-11-ynylidene)-3-hydroxy-4-methylbutanolide | Machilus wangchiana | Barks | [29] |

| 2 | (+)-(2E,3R,4S)-2-(Dodec-11-enylidene)-3-hydroxy-4-methylbutanolide | Machilus wangchiana | Barks | [29] |

| 3 | (+)-(2Z,3R,4S)-2-(Dodec-11-enylidene)-3-hydroxy-4-methylbutanolide | Machilus wangchiana | Barks | [29] |

| 4 | (+)-(2Z,3R,4S)-2-(Dodec-11-ynylidene)-3-hydroxy-4-methylbutanolide | Machilus wangchiana | Barks | [29] |

| 5 | (-)-(2Z,3S,4S)-2-(Dodec-11-ynylidene)-3-hydroxy-4-methylbutanolide | Machilus wangchiana | Barks | [29] |

| 6 | ent-Litsenolide C1 | Machilus wangchiana | Barks | [29] |

| 7 | 2-(1-Methoxy-11-dodecenyl)-penta-2,4-dien-4-olide | Lindera obtusiloba | Stems | [30] |

| 8 | (2Z,3S,4S)-2-(11-Dodecenylidene)-3-hydroxy-4-methylbutanolide | Lindera obtusiloba | Stems | [30] |

| 9 | (2E,3R,4R)-2-(11-Dodecenylidene)-3-hydroxy-4-methoxy-4-methylbutanolide | Lindera obtusiloba | Stems | [30] |

| 10 | Isoreticulide | Cinnamomum reticulatum | Leaves | [31] |

| 11 | Tenuifolide A | Cinnamomum tenuifolium | Stems | [32] |

| 12 | Isotenuifolide A | Cinnamomum tenuifolium | Stems | [32] |

| 13 | Tenuifolide B | Cinnamomum tenuifolium | Stems | [32] |

| 14 | Secotenuifolide A | Cinnamomum tenuifolium | Stems | [32] |

| 15 | Litseasesquibutenolide | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [33] |

| Other chain sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 16 | (2E,6E)-2,6-Dimethyl-10-methylene-dodecatrienoic acid | Ocotea minarum | Leaves | [34] |

| 17 | Caparratriene | Ocotea caparrapi | Oil extract | [35] |

| 18 | 3S-(+)-9-Oxonerolidol | Cinnamomum camphora, Cinnamomum chartophyllum | Aerial parts | [36, 37] |

| 19 | Nerolidol | Ocotea caparrapi | Oil extract | [35] |

| Monocyclic sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| Litseane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 20 | Litseaverticillol L | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [33] |

| 21 | Litseaverticillol M | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [33] |

| 22 | Litseaverticillol A | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [38] |

| 23 | Litseaverticillol B | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [38] |

| 24 | Litseaverticillol C | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [38] |

| 25 | Litseaverticillol D | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [38] |

| 26 | Litseaverticillol E | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [38] |

| 27 | Litseaverticillol F | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [38] |

| 28 | Litseaverticillol G | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [38] |

| 29 | Litseaverticillol H | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [38] |

| 30 | Litseachromolaevane B | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [39] |

| 31 | Isolitseane A | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [40] |

| 32 | Isolitseane B | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [40] |

| 33 | Isolitseane C | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [40] |

| Megastigmane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 34 | Turpenionoside A | Cinnamomum cassia | Immature buds | [41] |

| 35 | Wilsonol A | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 36 | (3S,4S,5S,6S,9S)-3,4-Dihydroxy-5,6-dihydro-β-ionol | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 37 | (3S,5R,6R,7E,9S)-3,5,6,9-Tetrahydroxy-7-ene-megastigmane | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 38 | (3S,5R,6S,7E)-Megasfifigma-7-ene-3,5,6,9-tetrol | Cinnamomum subavenium | Leaves | [44] |

| 39 | Wilsonol B | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 40 | Wilsonol D | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 41 | Wilsonol G | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 42 | Wilsonol H | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 43 | (3S,5S,6S,9R)-3,6-Dihydroxy-5,6-dihydro-β-ionol | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 44 | (3S,5R,6S,7E,9R)-7-Megastigmene-3,6,9-triol | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 45 | Wilsonol E | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 46 | Wilsonol F | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 47 | Wilsonol C | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 48 | Lasianthionoside A | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 49 | (3S,5R,6S,7E)-3,5,6-Trihydroxy-7-megastigmen-9-one | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [45] |

| 50 | Wilsonol I | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 51 | Wilsonol J | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 52 | (3R,9S)-Megastigman-5-ene-3,9-diol 3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 53 | (3S,4R,9R)-3,4,9-Trihydroxymegastigman-5-ene | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 54 | (1R,2R)-4-[(3S)-3-Hydroxybutyl]-3,3,5-trimethylcyclohex-4-ene-1,2-diol | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 55 | (1R,2R)-4-[(3R)-3-Hydroxybutyl]-3,3,5-trimethylcyclohex-4-ene-1,2-diol | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 56 | Wilsonol K | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 57 | Wilsonol L | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 58 | Apocynol A | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 59 | (+)-(6S,7E,9Z)-Abscisic ester | Cinnamomum wilsonii | Leaves | [42] |

| 60 | Asicariside B1 | Cinnamomum subavenium | Leaves | [44] |

| 61 | Staphylionoside D | Litsea cubeba | Twigs | [46] |

| 62 | Vomifoliol 9-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Litsea cubeba | Twigs | [46] |

| 63 | Dihydrovomifoliol-9-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Litsea cubeba | Twigs | [46] |

| Bisabolane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 64 | 3,4-Dihydroxy-β-bisabolol | Machilus zuihoensis | Stem woods | [47] |

| 65 | rel-(5R,7R)-l0-Desmethyl-1-methyl-1,10-dioxo-1,10-seco-11-eudesmene | Ocotea corymbosa | Unripe fruits | [48] |

| 66 | Azoridione | Laurus azorica | Aerial parts | [49] |

| 67 | (+)-β-Sesquiphellandren-12-oic acid | Ocotea minarum | Leaves | [34] |

| 68 | (+)-2-Methyl-6 [4-oxo-2-cyclohexen-1-yl]-2-(E)-heptenoic acid | Ocotea minarum | Leaves | [34] |

| 69 | (-)-Lanceolic acid | Ocotea minarum | Leaves | [34] |

| 70 | 4-oxo-Lanceolic acid | Ocotea minarum | Leaves | [34] |

| 71 | 4-Hydroxy-1,10-seco-muurol-5-ene-1,10-dione | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [50] |

| 72 | 6-(2-Hydroxy-6-methylhept-5-en-2-yl)-3-(hydroxymethyl)-4-oxocyclohex-2-en-1-yl acetate | Lindera benzoin | Leaves | [51] |

| 73a/b | 3-(Hydroxymethyl)-6-(5-(2-hydroxypropan-2-yl)-2-methyltetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-4-oxocyclohex-2-en-1-yl acetate | Lindera benzoin | Leaves | [51] |

| 74 | (-)-Curcumen-12-oic acid | Ocotea minarum | Leaves | [34] |

| 75 | 2-Methyl-6-(p-tolyl)heptane-2,3-diol | Cinnamomum chartophyllum | Aerial part | [52] |

| 76 | Litseachromolaevane A | Litsea verticillata, Cinnamomum cassia | Twigs, Barks, Leaves | [39, 50] |

| 77 | Cinnacasside A | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [45] |

| 78 | Bisabolene oxide | Phoebe porosa | Oil extract | [53] |

| 79 | (1S,3S,5R,6S)-11-O-β-D-Glucopyranosyl-14-oxo-dihydrophaseate | Litsea cubeba | Twigs | [54] |

| 80 | – a (CAS: 1300726-66-2) | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [55] |

| 81 | – a (CAS: 1300726-67-3) | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [55] |

| 82 | – a,b | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [55] |

| Elemane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 83 | Hiiranlactone C | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [56] |

| 84 | Isofuranogermacrene | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [57] |

| 85 | Sericealactone | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Roots | [58] |

| 86 | Hiiranlactone A | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [56] |

| 87 | de-O-Methylsericealactone | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [56] |

| 88 | Linderolide F | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [59] |

| 89 | 8-Hydroxyisogermafurenolide | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| 90 | Hiiranlactone B | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [56] |

| 91 | Hiiranlactone D | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [56] |

| 92 | Isosericenine | Neolitsea sericea | Leaves | [60] |

| 93 | Lauroxepine | Laurus nobilis | Fruits | [61] |

| 94 | Spirafolide | Laurus nobilis | Fruits | [61] |

| Germacrane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 95 | Litseagermacrane | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [39] |

| 96 | Shiromodiol-diacetate | Parabenzoin trilobum = Lindera triloba | Leaves | [62] |

| 97 | Shiromodiol-monoacetate | Parabenzoin trilobum = Lindera triloba | Leaves | [62] |

| 98 | Shiromool | Parabenzoin trilobum = Lindera triloba | Leaves | [62] |

| 99 | Costunolide | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [63] |

| 100 | Anhydroperoxycostunolide | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 101 | Lucentolide | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 102 | Deacetyl laurenobiolide | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [65] |

| 103 | Cyclodeca [b]furan,4,7,8,11-tetrahydro-3,6,10-trimethyl | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [57] |

| 104 | Sericenine | Neolitsea sericea | Leaves | [66] |

| 105 | Sericenic acid | Neolitsea sericea | Leaves | [66] |

| 106 | Deacetylzeylanine | Neolitsea parvigemma | Stems | [67] |

| 107 | Parvigemonol | Neolitsea parvigemma | Stem | [67] |

| 108 | Linderalactone | Neolitsea hiiranensis, Neolitsea zeylanica, Lindera strychnifolia, Neolitsea parvigemma | Roots, Stems | [58, 68, 69, 70] |

| 109 | Litsealactone | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [71] |

| 110 | Zeylanane | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [71] |

| 111 | Parvigemone | Lindera strychnifolia, Neolitsea parvigemma | Roots, Stems | [72, 73] |

| 112 | Linderanlide C | Lindera aggregata | Root tubers | [74] |

| 113 | Zeylaninone | Neolitsea acutotrinervia = N. aciculata | Roots | [75] |

| 114 | Acutotrinol | Neolitsea acutotrinervia = N. aciculata | Roots | [75] |

| 115 | Pseudoneoliacine |

|

Leaves, Roots | [56, 76] |

| 116 | Neoliacinolide A | Neolitsea hiiranensis, Neolitsea aciculuta | Leaves | [56, 77] |

| 117 | Neoliacine | Neolitsea aciculuta | Leaves | [77] |

| 118 | Linderoline | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [59] |

| 119 | Neoliacinolide B | Neolitsea aciculuta | Leaves | [77] |

| 120 | Neoliacinolide C | Neolitsea aciculuta | Leaves | [77] |

| 121 | Neoliacinic acid | Neolitsea aciculuta | Leaves | [77] |

| 122 | Linderanine B | Lindera aggregata | Root tubers | [74] |

| 123 | Linderanine A | Lindera aggregata | Root tubers | [74] |

| 124 | Linderanlide A | Lindera aggregata | Root tubers | [74] |

| 125 | Litseacassifolide | Litsea cassiaefolia | Barks | [78] |

| 126 | Pseudovillosine | Neolitsea kedahensis | Stems | [79] |

| 127 | Linderanlide B | Lindera aggregata | Root tubers | [74] |

| 128 | Acutotrinone | Neolitsea acutotrinervia = N. aciculata | Roots | [75] |

| 129 | (+)-Villosine | Neolitsea hiiranensis, Neolitsea villosa | Leaves, Roots | [56, 76] |

| 130 | Acutotrine | Neolitsea acutotrinervia = N. aciculata | Roots | [75] |

| 131 | Linderane | Neolitsea zeylanica, Lindera strychnifolia, Cryptocarya densiflora | Barks, Roots | [68, 71, 80] |

| 132 | Litseaculane | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [71] |

| 133 | Linderanlide D | Lindera aggregata | Root tubers | [74] |

| 134 | Linderanlide E | Lindera aggregata | Root tubers | [74] |

| 135 | Zeylanane | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [71] |

| 136 | Linderadine | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [71] |

| 137 | Pseudolinderadin | Cryptocarya densiflora | Barks | [80] |

| 138 | Zeylanidine | Neolitsea zeylanica, Neolitsea parvigemma, | Roots, Stems, Leaves, | [68, 70, 81] |

| 139 | Deacetylzeylanidine | Neolitsea parvigemma | Stems | [70] |

| 140 | (+)-Linderadine | Neolitsea Hiiranensis, Neolitsea villosa | Roots | [58, 76] |

| 141 | Neolitrane | Neolitsea parvigemma | Stems | [73] |

| 142 | Neolinderane | Neolitsea zeylanica, Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [68, 71] |

| 143 | Pseudoneolinderane | Neolitsea parvigemma, Neolitsea villosa | Stems, Roots | [70, 76] |

| 144 | Zeylanicine | Neolitsea zeylanica, Neolitsea parvigemma, | Roots, Stems, Leaves | [68, 70, 81] |

| 145 | Neolindenenonelactone | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [82] |

| Humulane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 146 | Litseahumulane B | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [39] |

| 147 | Litseahumulane A | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [39] |

| 148 | Humulene Epoxide Ⅲ | Phoebe porosa | Oil extract | [53] |

| 149 | (2E,9E)-6,7-cis-Dihydroxyhumulan-2,9-diene | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [45] |

| Other monocyclic sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 150 | Isolinderalactone | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [83] |

| 151 | Zeylanine | Neolitsea zeylanica | Roots | [68] |

| Bicyclic sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| Oplopanane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 152 | Oplopanone | Neolitsea acuminatissima | Roots | [7] |

| Oppositane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 153 | Octahydro-4-hydroxy-3R-methyl-7-methylene-R-(1-methylethyl)-1H-indene-1-methanol | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [39] |

| 154 | 1β,7-Dihydroxyl opposit-4(15)-ene | Cinnamomum cassia | Buds | [41] |

| 155 | 1β,11-Dihydroxyl opposit-4(15)-ene | Cinnamomum cassia | Buds | [41] |

| Cyperane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 156 | (+)-Faurinone | Lindera glauca | Twigs | [84] |

| 157 | Cinnamosim A | Cinnamomum cassia | Buds | [41] |

| 158 | 3α-Hydroxyisoiphion-11 (13)-en-12-oic acid 5β-Hydroxy-4-oxo-11 (13)-dehydroiphionan-12-oic acid | Nectandra cissiflora | Barks | [85] |

| 159 | 5β-Hydroxy-4-oxo-11 (13)-dehydroiphionan-12-oic acid | Nectandra cissiflora | Barks | [85] |

| 160 | Eudeglaucone | Lindera glauca | Twigs | [84] |

| Eremophilane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 161 | 4β,5β,7β- Eremophil-11-en-10α-ol | Ocotea lancifolia | Leaves | [86] |

| 162 | 10,11-Dihydroxyeremophilan-3-one 11-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [55] |

| 163 | (rel)-4β,5β,7β-Eremophil-9-en-12-oic acid | Ocotea lancifolia | Leaves | [86] |

| 164 | (rel)-4β,5β,7β-Eremophil-1 (10)-en-12-oic acid | Ocotea lancifolia | Leaves | [86] |

| 165 | (rel)-4β,5β,7β-Eremophil-1 (10)-en-2-oxo-12-oic acid | Ocotea lancifolia | Leaves | [86] |

| 166 | (rel)-4β,5β,7β-Eremophil-9-en-12,8α-olide | Ocotea lancifolia | Leaves | [86] |

| 167 | (rel)-4β,5β,7β-Eremophil-9-en-12,8β-olide | Ocotea lancifolia | Leaves | [86] |

| 168 | (rel)-4β,5β,7β-Eremophil-9α,10α-epoxy-12-oic acid | Ocotea lancifolia | Leaves | [86] |

| 169 | Valenc-l (l0)-ene-8,ll-diol | Litsea excelsa | Barks | [78] |

| Cadinane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 170 | 1β,4β,11-Trihydroxyl-6β-gorgonane | Cinnamomum cassia | Buds | [41] |

| 171 | rel-(4S,6S)-Cadina-1(10),7(11)-diene | Nectandra amazonum | Leaves | [87] |

| 172 | rel-(1R,4S,6S,10S)-Cadin-7 (11)-en-10-ol | Nectandra amazonum | Leaves | [87] |

| 173 | 15-Hydroxy-α-cadinol | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [45] |

| 174 | (-)-15-Hydroxy-T-muurolol | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [45] |

| 175 | 10-Hydroxyl-15-oxo-α-cadinol | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [39] |

| 176 | Cinnamoid B | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [45] |

| 174 | Cinnamoid C | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [45] |

| 178 | (4α,10β)-4,10-Dihydroxy cadin-1 (6)-en-5-one | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [45] |

| 179 | Oxyphyllenodiol B | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [40] |

| 180 | 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydro-2,5-dimethyl-8-(1-methylethyl)-1,2-naphthalenediol | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [40] |

| 181 | rel-(1R,4S)-7-Hydroxycalamenene | Ocotea elegans | Leaves | [88] |

| Eudesmane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 182 | Cryptomeridol | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Roots | [58] |

| 183 | Ilicic acid | Lindera glauca | Twigs | [84] |

| 184 | (1S,2S,4αR,5R,8R,8αS)-Decahydro-1,5,8-trihydroxy-4α,8-dimethyl-methylene-2-naphthaleneacetic acid methylester | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 185 | rel-(1S,4S,5R,7R,10R)-10-Desmethyl-1-methyl-11-eudesmene | Ocotea corymbosa | Unripe fruits | [48] |

| 186 | (3αS,5αR,6R,9S,9αS,9βS)-6,9-Dihydroxy-5α,9-dimethyl-3-methylidene-6. 3α,4,5,6,7,8,9α,9b-octahydrobenzo [g] [1]benzofuran-2-one | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 187 | (3αS,5αR,6R,9R,9αS,9βS)-6-Hydroxy-9-methoxy-5α,9-dimethyl-3-methylidene-3α,4,5,6,7,8,9α,9β-octahydrobenzo [g] [1]benzofuran-2-one | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 188 | rel-(1S,4R,5R,7R,l0R)-l0-Desmethyl-l0-hydroxy-1-methyl-3-oxo-ll-eudesmene | Ocotea corymbosa | Unripe fruits | [48] |

| 189 | Lauradiol | Laurus azorica | Aerial parts | [49] |

| 190 | Linderolide B | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [59] |

| 191 | Linderolide D | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [59] |

| 192 | (1S,2S,4αR,5R,6R,7R,8S,8αS)-Decahydro-1-hydroxy-5,6,7,8-diepoxy-4α,8-dimethyl-methylene-2-naphthaleneacetic acid methylester | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 193 | (3αS,5αR,6R,7R,8R,9S,9αS,9βS)-6,7,8,9-Diepoxy-5α,9-dimethyl-3-methylidene-5. 3α,4,5,6,7,8,9α,9β-octahydrobenzo [g][1]benzofuran-2-one | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 194 | γ-Selinene | Persea japonica | Stems | [89] |

| 195 | 4(15)-Eudesmene-1β,7,11-triol | Cinnamomum cassia | Buds | [41] |

| 196 | 1β,6α-Dihydroxyeudesm-4(15)-ene | Cinnamomum cassia | Buds | [41] |

| 197 | Polydactin B | Lindera communis | Fruits | [90] |

| 198 | Eudesm-4(15)-ene-1β,6α-diol | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [39] |

| 199 | 7-epi-Eudesm-4(15)-ene-1α,6α-diol | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [39] |

| 200 | 7-epi-Eudesm-4(15)-ene-1β,6β-diol | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [39] |

| 201 | 5-epi-Eudesm-4(15)-ene-1β,6β-diol | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [39] |

| 202 | Costic acid | Nectandra cissiflora | Barks | [85] |

| 203 | Viscic acid | Nectandra cissiflora | Barks | [85] |

| 204 | Baynol C | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 205 | Methyl-1β,2β,6α-trihydroxy-5α,7αH-eudesma-4(15),11(13)-dien-12-oate | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 206 | Costic acid methyl ester | Ocotea caudata | Leaves | [91] |

| 207 | Reynosin | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 208 | Hydroperoxide-magnolialide | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 209 | 1β,2β-Dihydroxy-5α,6β,7αH-eudesma-4(15),11(13)-dien-12,6-olide | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 210 | (3αS,5αR,6S,7R,9αR,9βS)-6-Hydroxy-7-acetoxy-5α-methyl-3,9-dimethylidene-3α,4,5,6,7,8,9α,9β-octahydrobenzo[g] [1]benzofuran-2-one | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 211 | Linderolide G | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| 212 | Linderolide H | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| 213 | Methylneolitacumone A | Neolitsea acuminatissima | Roots | [7] |

| 214 | Neolitacumone A | Neolitsea acuminatissima | Roots | [7] |

| 215 | Neolitacumone B | Neolitsea acuminatissima | Roots | [7] |

| 216 | Neolitacumone E | Neolitsea acuminatissima | Roots | [7] |

| 217 | 12-Carboxyeudesman-3,11(13)-diene | Nectandra cissiflora | Barks | [85] |

| 218 | Linerenone | Lindera communis | Fruits | [90] |

| 219 | Santamarine | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 220 | (3αS,5αR,6R,7R,9αS,9βS)-6,7-Dihydroxy-5α,9-dimethyl-3-methylidene-4,5,6,7,9α,9β-hexahydro-3αH-benzo[g] [1]benzofuran-2-one | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 221 | Linderagalactone E | Lindera aggregata | Root tubers | [92] |

| 222 | 3-oxo-g-Costic acid | Nectandra cissiflora | Barks | [85] |

| 223 | Machikusanol | Persea japonica | Stems | [89] |

| 224 | γ-Eudesmol | Persea japonica | Stems | [89] |

| 225 | Carissone | Persea japonica | Stems | [89] |

| 226 | γ-Costic acid | Lindera glauca | Twigs | [84] |

| 227 | Magnolialide | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 228 | 3α-Peroxyarmefolin | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 229 | Tubiferin | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 230 | (1S,2S,4αS,7R,8αR)-Decahydro-1,7-dihydroxy-4α-methyl-,8-bis(methylene)-2-naphthaleneacetic acid methylester | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 231 | (1S,2S,4αS,7R,8αR)-Decahydro-1-hydroxy-7-acetoxy-4α-methyl-,8-bis(methylene)-2-naphthaleneacetic acid methylester | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 232 | Linderolide E | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [59] |

| 233 | Lindestrenolide | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| 234 | Hydroxylindestrenolide | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| 235 | Linderolide A | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [59] |

| 236 | Linderolide C | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [59] |

| 237 | Linderolide J | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| 238 | Linderolide I | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| 239 | 3-oxo-4,5αH,8βH-Eudesma-1,7 (11)-dien-8,12-olide | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [93] |

| 240 | 3-oxo-5αH,8βH-Eudesma-1,4(15),7(11)-trien-8,12-olide | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [93] |

| 241 | Lindestrene | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [94] |

| 242 | Cinnamosim B | Cinnamomum cassia | Buds | [41] |

| 243 | Neolitacumone C | Neolitsea acuminatissima | Roots | [7] |

| 244 | 1β-Acetoxyeudesman-4(15),7(11),8(9)-trien-8,12-olide | Neolitsea acuminatissima | Stem barks | [95] |

| 245 | (1S,2S,4αS)-Decahydro-1-hydroxy-7-oxo-4α,8-dimethyl-methylene-2-naphthaleneacetic acid methylester | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 246 | 11,13-Dehydrosantonin | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [64] |

| 247 | Gazaniolide | Laurus nobilis | Fruits | [61] |

| 248 | 7αH-10βMe-eudesma-3,5-dien-11-ol | Litsea lancilimba | Fruits | [96] |

| 249 | Linderagalactone D | Lindera aggregata | Root tubers | [92] |

| 250 | 8-Hydroxylindestenolide | Lindera aggregata | Root | [82] |

| 251 | 1α,6β-Dihydroxy-5,10-bis-epi-eudesm-15-carboxaldehyde-6-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Cinnamomum subavenium | Leaves | [44] |

| 252 | Verticillatol | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [97] |

| 253 | (-)-ent-6α-Methoxyeudesm-4(15)-en-1β-ol | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [56] |

| 254 | Eudesm-4(15)-ene-1β,6α-diol | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [33] |

| 255 | α-Agarofuran | Phoebe porosa | Oil extract | [53] |

| 256 | (-)-Hydroxylindestrenolide | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [72] |

| 257 | 3-oxo-Eudesma-l,4(15),ll (13)triene12,6α-olide | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [98] |

| 258 | Bilindestenolide | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [99] |

| Isodaucane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 259 | Aphanamol II | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [39] |

| 260 | Salvialenone | Phoebe porosa | Oil extract | [53] |

| Guaiane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 261 | 4α-10α-Dihydroxy-5β-H-guaja-6-ene | Cinnamomum cassia | Buds | [41] |

| 262 | Isocurcumol | Litsea cassiaefolia | Barks | [78] |

| 263 | Pseudoguaianelactone C | Lindera glauca | Roots | [100] |

| 264 | Alismol | Phoebe poilanei | Leaves | [101] |

| 265 | Pseudoguaianelactone A | Lindera glauca | Roots | [100] |

| 266 | Zaluzanin D | Laurus nobilis | Leaves | [63] |

| 267 | Dehydrocostuslactone | Lindera aggregata | Root tubers | [74] |

| 268 | Pseudoguaianelactone B | Lindera glauca | Roots | [100] |

| 269 | Lancilimbnoid C | Litsea lancilimba | Fruits | [96] |

| 270 | Pancherione | Litsea lancilimba | Fruits | [96] |

| 271 | Lancilimbnoid D | Litsea lancilimba | Fruits | [96] |

| 272 | Lancilimbnoid E | Litsea lancilimba | Fruits | [96] |

| 273 | Shiluone B | Litsea lancilimba | Fruits | [96] |

| 274 | Shiluone C | Litsea lancilimba | Fruits | [96] |

| 275 | (-)-(4S,7S,10S)-2-oxo-Guaia-1(5),11(13)-dien-12-oic acid | Machilus wangchiana | Barks | [29] |

| Caryophyllane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 276 | (+)-Caryophyllenol II | Laurus azorica | Aerial parts | [49] |

| 277 | (4R,5R)-4,5-Dihydroxycaryophyll-8 (13)-ene | Beilschmiedia tsangii | Roots | [102] |

| 278 | β-Caryophyllene oxide | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [56] |

| 279 | Kobusone | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [56] |

| Spiroaxane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 280 | Linderagalactone B | Lindera aggregata | Root tubers | [92] |

| 281 | Linderagalactone C | Lindera aggregata | Root tubers | [92] |

| 282 | Lindenanolide G | Lindera chunii | Roots | [103] |

| 283 | Linderolide M | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| Other bicyclic sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 284 | Chromolaevanedione | Litsea verticillata | Leaves, Twigs | [40] |

| 285 | Lindenanolide E | Lindera chunii | Roots | [103] |

| 286 | Linderagalactone A | Lindera aggregata | Root tubers | [92] |

| 287 | Porosadienone | Phoebe porosa | Oil extract | [53] |

| Tricyclic sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| Bergamotene-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 288 | (+)-(E)-exo-α-Bergamoten-12-oic acid | Ocotea minarum | Leaves | [34] |

| Campherenane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 289 | Campherenol | Cinnamomum camphora | Woods | [104] |

| 290 | Campherenone | Cinnamomum camphora | Woods | [104] |

| Aristolane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 291 | Aristofone | Lindera communis | Fruits | [90] |

| Rearranged cadinane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 292 | Cinnamoid D | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [45] |

| 293 | Cinnamoid E | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [45] |

| 294 | Mustakone | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [45] |

| Gymnomitrane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 295 | (+)-5-Hydroxybarbatenal | Beilschmiedia tsangii | Roots | [102] |

| Clovane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 296 | Clovane -2β,9α-diol | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [45] |

| Aromadendrane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 297 | (6α,7α)-4β-Hydroxy-10α-methoxyaromadendrane | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [56] |

| 298 | Espatulenol | Ocotea lancifolia | Leaves | [86] |

| 299 | (-)-ent-4β-Hydroxy-10α-methoxyaromadendrane | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [56] |

| 300 | 4β,10α-Dihydroxyaromadendrane | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [56] |

| 301 | Pipelol A | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [56] |

| 302 | Spathulenol | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [56] |

| 303 | Hiiranepoxide | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [56] |

| 304 | Epiglobulol | Lindera communis | Fruits | [90] |

| 305 | Aromadendrane-4β,10α-diol | Cinnamomum cassia | Buds | [41] |

| 306 | Aromadendrane-4α,10α-diol | Cinnamomum cassia | Buds | [41] |

| 307 | 1-Epimeraromadendrane-4β,10α-diol | Cinnamomum cassia | Buds | [41] |

| Caryolane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 308 | Caryolane-1,9β-diol | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [45] |

| Lindenane-type sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 309 | Linderolide K | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| 310 | Linderolide N | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [72] |

| 311 | Linderolide O | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [72] |

| 312 | Linderolide P | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [72] |

| 313 | Linderolide Q | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [72] |

| 314 | Linderolide R | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [72] |

| 315 | Linderolide T | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [72] |

| 316 | Strychnilatone 2,6-dihydroxyxanthone | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [72] |

| 317 | Linderanlide F | Lindera aggregata | Root tubers | [74] |

| 318 | Lindenanolide A | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| 319 | Lindenene | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| 320 | Lindenenol | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| 321 | Lindeneol | Lindera chunii | Roots | [103] |

| 322 | Lindeneyl acetate | Lindera chunii | Roots | [103] |

| 323 | Lindenanolide H | Lindera chunii | Roots | [103] |

| 324 | Strychinstenolide 6-O-acetate A | Lindera chunii | Roots | [103] |

| 325 | Strychinstenolide 6-O-acetate B | Lindera chunii | Roots | [103] |

| 326 | Strychnilactone | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [59] |

| 327 | Shizukanolide | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| 328 | Chloranthalactone D | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| 329 | Linderolide S | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [72] |

| 330 | Lindenanolide G | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [72] |

| 331 | Linderolide U | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [83] |

| 332 | Linderolide L | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [28] |

| 333 | Lindenenol | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [83] |

| 334 | Menelloide C | Lindera strychnifolia | Roots | [72] |

| 335 | Linderanoid A | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 336 | Linderanoid B | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 337 | Linderanoid C | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 338 | Linderanoid D | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 339 | Linderanoid E | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 340 | Linderanoid F | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 341 | Linderanoid G | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 342 | Linderanoid H | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 343 | Linderanoid I | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 344 | Linderanoid J | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 345 | Linderanoid K | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 346 | Linderanoid L | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 347 | Linderanoid M | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 348 | Linderanoid N | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 349 | Linderanoid O | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [27] |

| 350 | Lindenanolide I | Lindera chunii | Roots | [105] |

| 351 | Lindenanolide F | Lindera chunii | Roots | [103] |

| 352 | Aggreganoid A | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [106] |

| 353 | Aggreganoid B | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [106] |

| 354 | Aggreganoid C | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [106] |

| 355 | Aggreganoid D | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [106] |

| 356 | Aggreganoid E | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [106] |

| 357 | Aggreganoid F | Lindera aggregata | Roots | [106] |

| Other tricyclic sesquiterpenoids | ||||

| 358 | Oreodaphnenol | Phoebe porosa | Woods | [107] |

| 359 | Cinnamoid A | Cinnamomum cassia | Bark | [45] |

| 360 | Subamol | Cinnamomum subavenium | Roots | [108] |

| 361 | Reticuol | Cinnamomum reticulatum | Leaves | [109] |

| 362 | Tenuifolin | Cinnamomum reticulatum, Cinnamomum tenuifolium | Leaves, Stems | [31, 32] |

The compound name was not given in the reference.

The CAS number was not given in the reference.

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of the sesquiterpenes isolated from Lauraceae.

3.2. Diterpenes

Based on the existed scientific research, 69 diterpenes were summed up in this review. Most diterpenes possess unprecedent, cage-like tricyclic or tetracyclic rigid carbon skeletons with multiple highly oxidized and modified functionalities. According to the different oxidation degree, these compounds can be divided into hemiketal-, ketal-, lactone- and diketone-type. Along with the deep-going research, eight sub-types of diterpene skeletons are categorized as: 11,12-seco-ryanodane (cinncassiol A type), ryanodane (cinncassiol B type), 7,8-seco-ryanodane (cinncassiol C type), isoryanodane (cinncassiol D type), 10,13-cyclo-12,13-seco-isoryanodane (cinncassiol E type), 12,13-seco-isoryanodane (cinncassiol F type), 11,12-seco-isoryanodane (cinncassiol G type) and 6,10-cyclo-12,13-seco-isoryanodane (cinnamomane). Among them, ryanodane diterpenes featured with a complex polyoxygenated 6/5/5/6/5 pentacyclic fused ring system prove to be the most characteristic chemical types. Notably, the distribution of ryanodane diterpenoid is so confined in Cinnamomum cassia, Cinnamomum zeylanicum and Persea indica that they can be regarded as the chemotaxonomic markers of the above species. All these compounds are summarized in Table 3 and their corresponding structures are detailed in Figure 4.

Table 3.

Diterpenoids from the family Lauraceae.

| No. | Name | Species | Botanical parts | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemiketal-type diterpenoids | ||||

| 363 | Cassiabudanol A | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [110] |

| 364 | Cassiabudanol B | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [110] |

| 365 | Secoperseanol | Persea indica | Aerial parts | [111] |

| 366 | Cinncassiol D1 | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [112] |

| 367 | Cinncassiol D1 glucoside | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [112] |

| 368 | Cinncassiol D2 | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [112] |

| 369 | Cinncassiol D2 glucoside | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [112] |

| 370 | Cinncassiol D3 | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [112] |

| 371 | Cinncassiol D4 | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [113] |

| 372 | Cinncassiol D4 glucoside | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [113] |

| 373 | Indicol | Persea indica | Branches | [114] |

| 374 | Vignaticol | Persea indica | Branches | [114] |

| 375 | Perseanol | Persea indica | Branches | [114] |

| 376 | 18-Hydroxyperseanol | Cinnamomum cassia | Stem barks | [115] |

| 377 | (18S)-3-Dehydroxycinncassiol D3 | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 378 | (18S)-3-Dehydroxycinncassiol D3 glucoside | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 379 | (18S)-3,5-Didehydroxy-1,8-dihydroxycinncassiol D3 | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 380 | (18S)-3-Dehydroxy-8-hydroxycinncassiol D3 | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 381 | 19-Dehydroxy-13-hydroxycinncassiol D1 | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 382 | (18S)-1-Hydroxycinncassiol D1 | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 383 | (18R)-1-Hydroxycinncassiol D1 | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 384 | 16-O-β-D-Glucopyranosyl-perseanol | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 385 | (18S)-Cinncassiol D1 | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 386 | (18S)-Cinncassiol D3 | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 387 | (E)-3-Dehydroxy-13(18)-ene-19-O-β-D glucopyranyl-cinncassia D3 | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 388 | Cinnacetal A | Cinnamomum cassia | Twigs and Leaves | [116] |

| 389 | Cinnacetal B | Cinnamomum cassia | Twigs and Leaves | [116] |

| 390 | Cinnzeylanine | Cinnamomum cassia, Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [117, 118] |

| 391 | Cinnzeylanol | Cinnamomum cassia, Cinnamomum cassia, Persea indica | Barks, Terminal Twigs | [117, 118, 119] |

| 392 | Cinncassiol B | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [120] |

| 393 | Cinncassiol B 19-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [120] |

| 394 | epi-Cinnzeylanol | Persea indica | Branches | [121] |

| 395 | Cinnzeylanone | Persea indica | Branches | [121] |

| 396 | Ryanodol | Persea indica | Terminal twigs | [121] |

| 397 | Ryanodol 14-monoacetate | Persea indica | Branches | [121] |

| 398 | 18-Hydroxycinnzeylanine | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [122] |

| 399 | Garajonone | Persea indica | Branches | [123] |

| 400 | 2,3-Didehydrocinnzeylanone | Persea indica | Branches | [123] |

| Ketal-type diterpenoids | ||||

| 401 | Cinncassiol F | Cinnamomum cassia | Stem barks | [115] |

| 402 | Cinnamomol A | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [124] |

| 403 | Cinnamomol B | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [124] |

| 404 | Cinncassiol E | Persea indica | Aerial parts | [111] |

| Lactone-type diterpenoids | ||||

| 405 | Anhydrocinnzeylanine | Cinnamomum cassia, Persea indica | Barks, Branches | [118, 123] |

| 406 | Anhydrocinnzeylanol | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [118] |

| 407 | Cinncassiol A | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [118] |

| 408 | 2,3-Dehydroanhydrocinnzeylanine | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [122] |

| 409 | 1-Acetylcinnacassiol A | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [122] |

| 410 | 18S-Cinncassiol A 19-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [122] |

| 411 | 18R-Cinncassiol A 19-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [122] |

| 412 | Anhydrocinnzeylanone | Persea indica | Branches | [123] |

| 413 | Epianhydrocinnzeylanol | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [125] |

| 414 | Cinnacasol | Cinnamomum cassia | Twigs | [126] |

| 415 | Cinnacaside | Cinnamomum cassia | Twigs | [126] |

| 416 | Cinnacasiol H | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [125] |

| 417 | Cinncassiol G | Cinnamomum cassia | Stem barks | [115] |

| 418 | 16-O-β-D-Glucopyranosyl-19-deoxycinncassiol G | Cinnamomum cassia | Stem barks | [116] |

| 419 | Cinncassiol G2 | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [127] |

| 420 | Cinnamomol C | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 421 | Cinnamomol D | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 422 | Cinnamomol E | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 423 | Cinnamomol F | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| 424 | Cinnamomol F glucoside | Cinnamomum cassia | Leaves | [43] |

| Diketone-type diterpenoids | ||||

| 425 | Cinncassiol C1 | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [128] |

| 426 | Cinncassiol C1 19-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [129] |

| 427 | Cinncassiol C2 | Cinnamomum cassia | Barks | [129] |

| 428 | Cinncassiol C3 | Cinnamomum cassia, Persea indica | Barks, Fruits | [129] |

| Other diterpenoids | ||||

| 429 | Kaurenoic acid | Pleurothyrium cinereum | Leaves | [130] |

| 430 | Cubelin | Persea indica | Fruits | [131] |

| 431 | Phytol | Lindera glauca | Aerial parts | [132] |

| 432 | trans-Phytol | Neolitsea hiiranensis | Leaves | [133] |

Figure 4.

Eight known carbon skeletal types of diterpenoids from C. cassia and chemical structures of the diterpenes isolated from Lauraceae.

The key biosynthetic pathways of representative diterpenes were also summarized in this review. Both 388 and 389 have the same cinnamaldehyde structural fragment, their respective intermediates a and b are cascade oxidized by 373. Then intermediates a and b with cinnamaldehyde, produce 388 and 389 through a step of acetalization at 5-OH, 16-OH and 4-OH, 5-OH, respectively. As for 401–403, a ketone intermediate ii is formed by 375, which the ether linkage between C-11 and C-6 of the hemiketal group is hydrolyzed under the catalysis of acid. 402 is produced by ii through aldol, retro-aldol, oxidation reaction and nucleophilic addition, while 403 is produced by an enzyme-mediated oxidation from 402. Similarly, biosynthesis of 417 can be derived from 375 through oxidation, reduction and dehydration reaction. The proposed biosynthetic pathways of 388, 389, 401–403 and 417 are described as Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The proposed biosynthetic pathways of compounds (388, 389, 401–403 and 417).

4. Biological activities

At present, quite a few bioactivity studies on the isolated sesquiterpenes and diterpenes have been carried out. Notably, sesquiterpenes are the main class responsible for the anti-tumor effects, which exhibit the cytotoxic, anti-proliferative and/or apoptotic activities against a variety of human cancer cell lines. Besides, the sesquiterpenes inhibitory capacities on inflammation, oxidation, bacterium, HIV virus, diabetic nephropathy, platelet aggregation and E. coli β-Glucuronidase (anti-eβG) are also striking. As for the diterpenes, immunomodulation is their most prominent activity. Through the ConA/LPS-induced splenocyte proliferation assay, several ryanodines and isoryanodines with novel carbon skeletons exert the extraordinary T cells and Treg cells modulation abilities. Specific biological properties of the isolated sesquiterpenes and diterpenes are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Biological properties of the isolated sesquiterpenes and diterpenoids.

| Biological properties | Compound number | Effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxic and anti-proliferative activity | |||

| Cytotoxicity against myeloid leukemia cell (HL-60), hepatocellular carcinoma cell (SMMC-7721), lung cancer cell (A549), breast cancer cell (MCF-7) and colon cancer cell (SW-480) | 52 | IC50 values are 5.04, 3.13, 2.50, 3.14 and 12.28 μM, respectively | [42] |

| Cytotoxicity against human ovarian cancer cell (A2780) | 99, 247, 93, 219, 246, 94, 207 | IC50 values are 6.4, 4.2, 34.6, 9.4, 6.6, 4.0 and 13.5 μg/mL, respectively | [61] |

| Cytotoxicity against human CEM leukemia cell | 17 | IC50 value is 3.0 ± 0.5 μM | [35] |

| Cytotoxicity against A549 cell line, ovarian cancer cell (SK-OV-3), skin cancer cell (SK-MEL-2), CNS cancer cell (XF498) and colon cancer cell (HCT15) | 7, 8, 9 | EC50 values are 9.65, 4.73, 3.19, 3.88, 3.57 μg/mL for 7; EC50 values are 9.43, 6.71, 4.06, 7.14, 5.21 μg/mL for 8; EC50 values are 14.63, 12.92, 10.07, 12.80, 10.14 μg/mL for 9 | [30] |

| Cytotoxicity against A549 cell line and colon cancer cell (HCT-8) | 79 | IC50 values are 8.9, 9.6 μM, respectively | [54] |

| Cytotoxicity against leukemia cell (K562) | 207, 208, 210, 219, 220, 227, 228, 193, 186, 187, 246, 229, 100, 101, 230, 192, 184, 245 | IC50 values are 126.61 ± 16.30, 24.19 ± 0.38, 243.41 ± 66.90, 22.47 ± 1.46, 222.09 ± 52.20, 27.83 ± 1.05, 4.57 ± 2.10, 136.73 ± 42.61, 193.31 ± 41.51, 58.71 ± 36.57, 46.95 ± 6.62, 90.90 ± 9.70, 39.46 ± 1.65, 116.00 ± 26.12, 111.27 ± 27.79, 182.66 ± 54.07, 233.28 ± 55.02, 246.03 ± 83.75 μM, respectively | [64] |

| Cytotoxicity against A549 cell line, mouse lymphocytic leukemia cell (P-388), oral epithelial carcinoma KB cell and colon cancer cell (HT-29) | 150 | EC50 values are 1.420, 0.816, 2.990, 1.528 ppm, respectively | [83] |

| Cytotoxicity against SK-MEL-2 and HCT15 cell lines | 204, 202 | IC50 values are 10.25 and 9.98 μM for 204; 12.20 and 11.60 μM for 202 | [84] |

| Cytotoxicity against human lung cancer cell (H460), human mammary cancer cell (ES2) and human prostatic cancer cell (DU145) | 218, 197, 291, 304 | IC50 values are 2.1 ± 0.72, 2.8 ± 0.65, 3.0 ± 0.70 μM for 218; 56.1 ± 2.5, 57.0 ± 2.3, 45.8 ± 1.6 μM for 197; 51.3 ± 0.9, 61.5 ± 1.1, 58.0 ± 0.9 μM for 291; 33.0 ± 1.5, 29.9 ± 0.3, 27.3 ± 0.6 μM for 304 | [90] |

| Cytotoxicity against human small lung cancer cell (SBC-3) | 239 | IC50 values are 7.2 and 32.2 μM, respectively | [93] |

| Cytotoxicity against human hepatoma cell (Hep G2) and Hep G2 cell transfected with HBV (Hep 2,2,15) | 214, 215, 243 | IC50 values are 8.4 ± 0.74, 8.4 ± 0.26 μM for 214; 7.6 ± 0.22, 0.24 ± 0.04 μM for 215; 8.5 ± 0.43, 0.08 ± 0.02 μM for 243 | [95] |

| Growth inhibition and apoptotic induction to HL-60 cell line | 99, 266 | The proliferations of HL-60 cells are inhibited at 10μM of 99 and 15μM of 266, respectively. They exert antitumor activity by triggering apoptotic chromatin condensation | [63] |

| 100, 257 | 100 and 257 induced the apoptotic morphological changes of the nucleus and chromatin condensation in the HL-60 cells | [98] | |

| Growth inhibition and apoptotic induction to HCT-116 cell line | 150 | IC50 value is 21.8 μM | [83] |

| Growth inhibition and apoptotic induction to human cervical cancer cell line (HeLa) | 430 | IC50 values are 34.43 μM at 24 h and 21.92 μM at 48 h. The cells exhibited changes in nuclear morphology and the cleaved caspase-3/-7, caspase-8 and caspase-9 of 430 | [131] |

| Cytotoxicity against HSC-T6 hepatic stellate cells | 211, 233, 241 | 211 and 233 showed inhibition of the viability of HSC-T6 cells, and 241 exhibits a weaker inhibition | [28] |

| Immunomodulatory activity | |||

| ConA/LPS-induced splenocyte proliferation assay | 35, 39, 50, 53, 43 | 35, 39, 50, 53 inhibited the proliferation of ConA-induced murine T cells, and 50, 53, 43 inhibited the proliferation of LPS induced murine B cells | [42] |

| 416, 414 | 416 and 414 inhibited the proliferation of ConA/LPS-induced splenocyte in a dose-dependent manner | [115] | |

| 363, 364 | 363 and 364 promoted the proliferation of ConA/LPS-induced splenocyte with enhancement rates up to 39.99% and 92.36% at 0.0015 μM. 364 enhanced the immune function by upregulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and downregulating Tregs | [110] | |

| ConA-induced splenocyte proliferation assay | 402, 403 | 402 and 403 enhanced the proliferation of ConA-induced murine T cells with enhancement rates ranging from 29 to 64% at concentrations from 0.391 to 100 μM. 402 enhanced immunity by increasing CD4+ T cell proliferation, while reducing Treg differentiation | [124] |

| Evaluation of the immunomodulatory effects on the splenocyte proliferation | 280, 91, 432 | 280, 91 and 432 suppressed IFN-γ in vitro. 280 inhibits the expression of IFN-γ, T-bet, IL-12β2, T-cell differentiation and Th1-assocaited genes | [133] |

| Anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative activity | |||

| Evaluation of Nrf2 inducing effects | 18 | 18 activates Nrf2 and its downstream genes, NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 and γ-glutamyl cysteine synthetase, and enhances the nuclear translocation and stabilization of Nrf2 in human lung epithelial cells | [36, 37] |

| Inhibition of PGE2 formation in A549 cell line | 72, 73a/b | 72 and 73a/b reduce PGE2 formation at 10 μM and 100 μM, respectively | [51] |

| Inhibition of LPS-stimulated NO production in RAW 264.7 cells | 18 | 18 inhibite LPS-stimulated NO production, blocked NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-6 and PGE2 activation | [36, 37] |

| 236, 191, 88 | 236, 191 and 88 are moderately inhibition to LPS-stimulated NO production | [59] | |

| 311, 312, 111 | 311, 312 and 111 show inhibition against NO production with IC50 values of 6.3, 9.6 and 9.0 μM, respectively | [72] | |

| 265, 268, 263 | 265, 268 and 263 inhibite NO production with IC50 values of 2.43 ± 0.27 μM, 4.00 ± 1.15 μM and 1.38 ± 0.30 μM, respectively, and suppress the production of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and PGE2 and the enzyme expression of iNOS and COX-2 in protein levels | [100] | |

| 269, 271, 272 | IC50 values of 269, 272 and 272 are 35.5, 32.1, 46.7 μM, respectively | [96] | |

| Inhibition of fMLP-induced superoxide production | 90, 91 | IC50 values are 21.86 ± 3.97 and 25.78 ± 4.77 μM, respectively | [56] |

| Inhibition of fMLP-induced neutrophils | 143, 108 | IC50 values are 21.86 ± 3.97 and 25.78 ± 4.77 μM, respectively | [70] |

| Inhibition of H2O2-induced oxidative damages on HepG2 cells | 221, 131, 250, 108 | 221, 131, 250 and 108 show hepatoprotective activity against H2O2-induced oxidative damages on HepG2 cells with EC50 values of 67.5, 167.0, 42.4 and 98.0 μM, respectively | [92] |

| Inhibition of NO production in BV-2 cells | 413, 416, 406, 405, 407, 391, 390 | 413, 416, 406, 405, 407, 391 and 390 show inhibition activities on NO production in LPS induced BV-2 microglial cells with IC50 values of 80.7, 76.1, 83.8, 73.8, 78.7, 72.3, 81.8, 68.6 and 71.5 μM, respectively | [125] |

| 160, 183, 226, 202 | 160, 183, 226, 202 significantly inhibite NO levels in LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells with IC50 values of 15.90, 3.67, 26.48, 14.92, 24.44 and 12.13 μM, respectively | [84] | |

| Antimicrobial activity | |||

| Evaluation for antimicrobial activities against E. coli, C. albicans and S. aureus using an agar-well diffusion method. | 157, 242, 154,195, 196, 308, 261, 306, 307 | 157, 242, 154, 195, 196, 308, 261, 306 and 307 exhibit strong antimicrobial activities against C. albicans with inhibitory zones of 11, 10, 8, 9, 11, 10, 9, 10 and 10 mm at 300 μg/disk. 196, 308 and 306 show moderate antibacterial activities against E. coli and S. aureus with inhibitory zones of 8.5, 7, 7 and 11, 8.5, 10 mm, respectively | [41] |

| Evaluation for antifungal activities against C. albicans, C. krusei, and Cryptococcus neoformans using the broth microdilution method. | 67, 69, 68, 288, 16 | 67, 69, 68, 288 and 16 exhibit MIC values in the 50–100 μg/mL | [34] |

| Evaluation for antimicrobial activities against periodontal pathogens | 102 | 102 shows growth inhibitory effects with MICs at 375, 63, 500 and 125 μg/mL against Actinomyces viscosus, A Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia | [65] |

| Evaluation the Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Rv by the microplate Alamar Blue assay | 429 | 429 induces 91.3% growth inhibition at 50 μg/mL against M. tuberculosis H37Rv | [130] |

| Anti-HIV activity | |||

| Inhibitory effects against HIV-1 replication in a reporter cell line HOG.R5 | 20 + 21 | 20 + 21 exhibit anti-HIV activity with an IC50 value of 49.6 μM | [33] |

| 32, 179, 180 | 32, 179 and 180 inhibit HIV-1 replication in HOG.R5 cell line with IC50 values of 38.1 ± 4.2, 54.6 ± 4.2, 91.0 ± 6.5 μM, respectively. | [40] | |

| 95, 201, 30 | 95, 201 and 30 inhibit HIV-1 replication in HOG.R5 cell line with IC50 values of 6.5 (27.5), 17.4 (73.1) and 28.0 (119.7) μg/mL (μM), respectively | [38] | |

| 252 | 252 demonstrates weak activity with an IC50 value of 34.5 μg/mL (144.7 μM) while being devoid of cytotoxicity at 20 mg/mL | [97] | |

| Other bioactivities | |||

| Antidiabetic nephropathy activity | 293, 174, 300 | 293, 174 and 300 markedly decrease the expression of fibronectin, MCP-1 and interleukin-6 at the concentration of 50 μΜ in the high glucose-stimulated mesangial cells | [45] |

| Inhibition of platelet aggregation | 138, 144, 108, 106, 111, 107 | At the concentration of 100 μg/mL, 138 and 144 inhibit the PAF induced platelet aggregation. 108 and 106 show inhibition of AA induced platelet aggregation. 111 and 107 inhibit the collagen-induced platelet aggregation | [134] |

| Anti-E. coli β-Glucuronidase (anti-eβG) activity | 213 | 213 shows a moderate inhibitory effect and enzyme activity on bacterial-βG but not human-βG | [7] |

5. Conclusion and prospects

The extensive application in medicinal and nutraceutical products of Lauraceae plants have inspired great attention of researchers on their scientific investigations and commercial development. Published works act as a jumping-off point for future research, however, the dispersive and broad conclusions from independent exploration are somewhat inability to precisely reflect the valuable points and highlights. This review summaries the sesquiterpenes and diterpenes obtained from Lauraceae plants and systematically examines their health-promoting benefits related to the plant traditional effectiveness and the modern pharmacology, which is intended to offer some preliminary information for follow-up studies on any bioactivities and components.

As reported, sesquiterpenes are a substantial oily composition and distribute so widely in the barks, leaves, twigs, roots and stem woods of all the Lauraceae plants studied so far. Coincide with the structure diversity, sesquiterpenes show a variety of physicochemical and biological properties. Notably, this composition is utilized primarily and coarsely in pharmacy, food and light industries until now. On the basis of this review, some clues for expanding their potential value are provided. Conversely, diterpenes appear only in a very limited species and ryanodane-type diterpenes are account for the overwhelming majority. As a kind of newfound compounds with unprecedent and diverse carbon skeletons, ryanodane-type diterpenes quickly become the focuses of organic chemistry, biosynthesis and pharmacology field. In the view of secondary metabolites biosynthesis, the structure type and species-genera distribution of sesquiterpenes and diterpenes in Lauraceae are indeed unique compared with other plants. Four types sesquiterpenes, megastigmane-, germacrane-, eudesmane- and lindenane-sesquiterpenes accounted for more than 60% of total sesquiterpenes. And almost all ryanodine-type diterpenes so concentrated in three Lauraceae plants Cinnamomum cassia, Cinnamomum zeylanicum and Persea indica that could be used as the chemical marker for plants identification. The highly concentration both chemicals and plants indicated some definite distribution and biosynthesis regularity deserved further research. Besides, research have indicated that ryanodane diterpenes are proposed as a potential new type agonist on ryanodine receptor, an important calcium channel in sarcoplasmic reticulum and one of the most important insecticide targets. The obvious antifeedant bioactivity of ryanodanes and the toxicity difference acting on the insects and mammalians prompts that ryanodanes are a category of promising pesticides and deserved a profound study.

This review points that 102 sesquiterpenes and 15 diterpenes possess the confirmed health promotive effects, but their applications in function improvements still face numerous challenges. Most of them need more in-depth studies, including in vitro and in vivo evaluation to prove the efficacy and safety of use. As the promising natural pesticide, ryanodanes are required more toxicological investigations to confirm the exact insecticidal activity. Once satisfactory results are obtained, engaged in the discovery of diverse ryanodanes and applied them in the medicine, fine chemistry and food industry is of broad prospects. Overall, the sesquiterpenes and diterpenes from Lauraceae plants are a large category of valuable natural resource that is worthy paying strengthened attention due to their extensive bioactivities and potential development.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

Dr. Meng Shao was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province [2020A1515010603], Guangzhou Science and Technology Project [201904010405], Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Guangdong Province of China Project [20221261]. Yiping Jiang was supported by Zhuhai Medical Research Fund Project [No. ZH3310200024PJL], Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Guangdong Province of China Project [20211356].

Data availability statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Contributor Information

Daoqi Zhu, Email: zhudaoqi@163.com.

Meng Shao, Email: shaomeng_smu@163.com.

References

- 1.Flora of China Editorial Committee . Science Press; Beijing, China: 2008. Flora of China. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao Y., Gao X.L., Su G.Z., Yu X.L., Tu P.F., Chai X.Y. The genus Neolitsea of Lauraceae: a phytochemical and biological progress. Chem. Biodivers. 2015;12(10):1443–1465. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201400084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y., Xie S., Ying J., Wei W., Gao K. Chemical structures of lignans and neolignans Isolated from Lauraceae. Molecules. 2018;23(12) doi: 10.3390/molecules23123164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silva Teles M.M.R., Vieira Pinheiro A.A., Da Silva Dias C., Fechine Tavares J., Barbosa Filho J.M., Leitao Da Cunha E.V. Alkaloids of the lauraceae. Alkaloids - Chem. Biol. 2019;82:147–304. doi: 10.1016/bs.alkal.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J., Su B., Jiang H., Ning C., Sun Y. Traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of the genus cinnamomum (lauraceae): a review. Fitoterapia. 2020;146 doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2020.104675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zareie A., Sahebkar A., Khorvash F., Bagherniya M., Hasanzadeh A., Askari G. Effect of cinnamon on migraine attacks and inflammatory markers: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Phytother Res. 2020;34(11):2945–2952. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin C.H., Chou H.J., Chang C.C., Chen I.S., Chang H.S., Cheng T.L., Kuo Y.H., Ko H.H. Chemical constituent of beta-Glucuronidase inhibitors from the root of Neolitsea acuminatissima. Molecules. 2020;25(21) doi: 10.3390/molecules25215170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Souza K.F.S., Tofoli D., Pereira I.C., Filippin K.J., Guerrero A.T.G., Paredes-Gamero E.J., de Fatima Cepa Matos M., Garcez W.S., Garcez F.R., Perdomo R.T. A styrylpyrone dimer isolated from Aniba heringeri causes apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 triple-negative breast cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021;32 doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.115994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliveira-Junior J.B., da Silva E.M., Veras D.L., Ribeiro K.R.C., de Freitas C.F., de Lima F.C.G., Gutierrez S.J.C., Camara C.A., Barbosa-Filho J.M., Alves L.C., Brayner F.A. Antimicrobial activity and biofilm inhibition of riparins I, II and III and ultrastructural changes in multidrug-resistant bacteria of medical importance. Microb. Pathog. 2020;149 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang C., Fan L., Fan S., Wang J., Luo T., Tang Y., et al. Cinnamomum cassia presl: a review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology. Molecules. 2019;24(19) doi: 10.3390/molecules24193473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh N., Rao A.S., Nandal A., Kumar S., Yadav S.S., Ganaie S.A., Narasimhan B. Phytochemical and pharmacological review of Cinnamomum verum J. Presl-a versatile spice used in food and nutrition. Food Chem. 2021;338 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao Y., Xu B. New insights into chemical compositions and health promoting effects of edible oils from new resources. Food Chem. 2021;364 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salleh Wan Mohd, Wan Nuzul Hakimi, Ahmad Farediah. Phytochemistry and biological activities of the genus Ocotea (Lauraceae): a review on recent research results (2000–2016) J. Appl. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2017;7(5):204–218. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H., Liu B., Davis C.C., Yang Y. Plastome phylogenomics, systematics, and divergence time estimation of the Beilschmiedia group (Lauraceae) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2020;151 doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2020.106901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sundararaj R., Shanbhag R.R., Nagaveni H.C., Vijayalakshmi G. Natural durability of timbers under Indian environmental conditions – an overview. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2015;103:196–214. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Julian Thielmann, Maria Theobald, Andrea Wutz, Tomislav Krolo, Alexandra Buergy, Julia Niederhofer, Peter Muranyi. Litsea cubeba fruit essential oil and its major constituent citral as volatile agents in an antimicrobial packaging material. Food Microbiol. 2021;96 doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2020.103725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen F., Miao X., Lin Z., Xiu Y., Shi L., Zhang Q., Liang D., Lin S., He B. Disruption of metabolic function and redox homeostasis as antibacterial mechanism of Lindera glauca fruit essential oil against Shigella flexneri. Food Control. 2021;130 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozogul Yesim, El Abed, Nariman, Ozogul Fatih. Antimicrobial effect of laurel essential oil nanoemulsion on food-borne pathogens and fish spoilage bacteria. Food Chem. 2021;368 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian Z., Luo Q., Zuo Z. Seasonal emission of monoterpenes from four chemotypes of Cinnamomum camphora. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;163 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao C.C., Yang X.B., Xu M., Yang L., Mo K.L. GC-MS analysis of volatile oil from leaves of Cinnamomum pedunculatum from Sichuan. J Sichuan Forestry Sci. Tech. 2018;39:26–29. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee S.C., Wang S.Y., Li C.C., Liu C.T. Anti-inflammatory effect of cinnamaldehyde and linalool from the leaf essential oil of Cinnamomum osmophloeum Kanehira in endotoxin-induced mice. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018;26(1):211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X., Lu H.Y., Jiang X.W., Yang Y., Xing B., Yao D., Wu Q., Xu Z.H., Zhao Q.C. Cinnamomum cassia extract promotes thermogenesis during exposure to cold via activation of brown adipose tissue. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020;266 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai H., Wang J., Luo Y., Wang F., He G., Zhou G., Peng X. Lindera aggregata intervents adenine-induced chronic kidney disease by mediating metabolism and TGF-beta/Smad signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021;134 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y.S., Wen Z.Q., Li B.T., Zhang H.B., Yang J.H. Ethnobotany, phytochemistry, and pharmacology of the genus Litsea: an update. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;181:66–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J., Lim S. Anti-inflammatory, and anti-arthritic effects by the twigs of Cinnamomum cassia on complete Freund's adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021;278 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun L., Liu L.N., Li J.C., Lv Y.Z., Zong S.B., Zhou J., Wang Z.Z., Kou J.P., Xiao W. The essential oil from the twigs of Cinnamomum cassia Presl inhibits oxytocin-induced uterine contraction in vitro and in vivo. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017;206:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X., Fu J., Shen R.S., Wu X.J., Yang J., Bai L.P., Jiang Z.H., Zhu G.Y. Linderanoids A–O, dimeric sesquiterpenoids from the roots of Lindera aggregata (Sims) Kosterm. Phytochemistry. 2021;191 doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2021.112924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Q., Ahn J.H., Kim S.B., Lee C., Hwang B.Y., Lee M.K. Sesquiterpene lactones from the roots of Lindera strychnifolia. Phytochemistry. 2013;87:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng W., Zhu C., Xu W., Fan X., Yang Y.C., Li Y., Chen X.G., Wang W.J., Shi J.G. Chemical constituents of the bark of Machilus wangchiana and their biological activities. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72(12):2145–2152. doi: 10.1021/np900504a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwon H.C., Baek N.I., Choi S.U., Lee K.R. New cytotoxic butanolides from Lindera obtusiloba Blume. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000;48(5):614–616. doi: 10.1248/cpb.48.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin I.J., Yeh H.C., Cham T.M., Chen C.Y. A new butanolide from the leaves of Cinnamomum reticulatum. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2011;47(1):43. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin R.J., Cheng M.J., Huang J.C., Lo W.L., Yeh Y.T., Yen C.M., Lu C.M., Chen C.Y. Cytotoxic compounds from the stems of Cinnamomum tenuifolium. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72(10):1816–1824. doi: 10.1021/np900225p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guan Y., Wang D., Tan G.T., Van Hung N., Cuong N.M., Pezzuto J.M., Fong H.H., Soejarto D.D., Zhang H. Litsea species as potential antiviral plant sources. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2016;44(2):275–290. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X16500166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nogueira C.R., Carbonezi L.H., de Oliveira C.T.F., Garcez W.S., Garcez F.R. Sesquiterpene derivatives from Ocotea minarum leaves. Phytochem. Lett. 2021;42:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palomino E., Maldonado C., Kempff M.B., Ksebati M.B. Caparratriene, an active aesquiterpene hydrocarbon from Ocotea caparrapi. J. Nat. Prod. 1996;59(1):77–79. doi: 10.1021/np960012r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Y.R., Fu C.S., Yang W.J., Wang X.L., Feng D., Wang X.N., Ren D.M., Lou H.X., Shen T. Investigation of constituents from Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J. Presl and evaluation of their anti-inflammatory properties in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;221:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou M.X., Li G.H., Sun B., Xu Y.W., Li A.L., Li Y.R., Ren D.M., Wang X.N., Wen X.S., Lou H.X., Shen T. Identification of novel Nrf2 activators from Cinnamomum chartophyllum H.W. Li and their potential application of preventing oxidative insults in human lung epithelial cells. Redox Biol. 2018;14:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang H.J., Tan G.T., Hoang V.D., Hung N.V., Cuong N.M., Soejarto D.D., Pettuto J.M., Fong H.H.S. Natural anti-HIV agents. Part 3: Litseaverticillols A–H, novel sesquiterpenes from Litsea verticillata. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:141–148. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang H.J., Tan G.T., Santarsiero B.D., Mesecar A.D., Hung N.V., Cuong N.M., Soejarto D.D., Pezzuto J.M., Fong H.H.S. New sesquiterpenes from Litsea verticillata. J. Nat. Prod. 2003;66(5):609–615. doi: 10.1021/np020508a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H.J., Nguyen V.H., Nguyen M.C., Soejarto D.D., Pezzuto J.M., Fong H.H., Tan G.T. Sesquiterpenes and butenolides, natural anti-HIV constituents from Litsea verticillata. Planta Med. 2005;71(5):452–457. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-864142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guoruoluo Y., Zhou H., Zhou J., Zhao H., Aisa H.A., Yao G. Isolation and characterization of sesquiterpenoids from Cassia buds and their antimicrobial activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017;65(28):5614–5619. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shu P., Wei X., Xue Y., Li W., Zhang J., Xiang M., Zhang M., Luo Z., Li Y., Yao G., Zhang Y. Wilsonols A-L, megastigmane sesquiterpenoids from the leaves of Cinnamomum wilsonii. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;76(7):1303–1312. doi: 10.1021/np4002493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou L. A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requiterments for the Degree of Master; Wuhan, WH: 2016. Study on the Chemical Constituents and Immunomodulatory Activities of Leaves of Cinnamomum cassia. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hao X., Chen J., Lai Y., Sang M., Yao G., Xue Y., Luo Z., Zhang G., Zhang Y. Chemical constituents from leaves of Cinnamomum subavenium. Biochem. Systemat. Ecol. 2015;61:156–160. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yan Y.M., Fang P., Yang M.T., Li N., Lu Q., Cheng Y.X. Anti-diabetic nephropathy compounds from Cinnamomum cassia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;165:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang L.Y., Qu Y.H., Li Y.C., Wu Y.Z., Li R., Guo Q.L., Wang S.J., Wang Y.N., Yang Y.C., Lin S. [Water soluble constituents from the twigs of Litsea cubeba] Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2017;42(14):2704–2713. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.2017.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng M.J., Jayaprakasam B., Ishikawa T., Seki H., Tsai I.L., Wang J.J., Chen I.S. Chemical and cytotoxic constituents from the stem of Machilus zuihoensis. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2002;85 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chavez J.P., Gottlieb O.R., Yoshida M. 10-Desmethyl-1-Methyl-Eudesmanes from Ocotea corymbosa. Phytochemistry. 1995;39(4):849–852. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fraga B.M., Cabrera I., Reina M., Terrero D. Two new sesquiterpenes from Laurus azorica. Z. Naturforsch., C: J. Biosci. 2001;56(7-8):503–505. doi: 10.1515/znc-2001-7-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen B.J. A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requiterments for the Degree of Master; Shandong, SD: 2015. Research on Chemical Constituents of Cinnamomum cassia Presl and Cinnamomum porrectum (Roxb.) Kosterm. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryen H.A., Göls T., Steinmetz J., Tahir A., Jakobsson P.-J., Backlund A., Urban E., Glasl S. Bisabolane sesquiterpenes from the leaves of Lindera benzoin reduce prostaglandin E2 formation in A549 cells. Phytochem Lett. 2020;38:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu Y.W. A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requiterments for the Degree of Master; Shandong, SD: 2016. Research on Chemical Constituents of Cinnamomum chartophyllum H. W.Li. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weyerstahl P., Marschall H., Splittgerber U. Porosadienone, a Phoebe oil sesquiterpene with a new carbon skeleton. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1994:523–525. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang L.Y., Tian Y., Qu Y.H., Wu Y.Z., Li Y.C., Li R., Lin P.C., Shang X.Y., Lin S. Two new terpenoid ester glycosides from the twigs of Litsea cubeba. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2018;20(12):1129–1136. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2018.1526789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mimura A., Sumioka H., Matsunami K., Otsuka H. Conjugates of an abscisic acid derivative and phenolic glucosides, and a new sesquiterpene glucoside from Lindera strychnifolia. J. Nat. Med. 2010;64(2):153–160. doi: 10.1007/s11418-010-0391-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liou B.J., Chang H.S., Wang G.J., Chiang M.Y., Liao C.H., Lin C.H., Chen I.S. Secondary metabolites from the leaves of Neolitsea hiiranensis and the anti-inflammatory activity of some of them. Phytochemistry. 2011;72(4-5):415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takeda K., Ishii H., Tozyo T. Components of the root of Lindera strychnifolia Vill. Part XVI. Isolation of Lindenene showing a new fundamental sesquiterpene skeleton, and its correlation with Linderene. J. Chem. Soc. C. 1969;(14):2826. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu S.L., Li W.S. Chemical constituents from the roots of Neolitsea hiiranensis. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 1995;42(3):555–560. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sumioka H., Harinantenaina L., Matsunami K., Otsuka H., Kawahata M., Yamaguchi K. Linderolides A-F, eudesmane-type sesquiterpene lactones and linderoline, a germacrane-type sesquiterpene from the roots of Lindera strychnifolia and their inhibitory activity on NO production in RAW 264.7 cells in vitro. Phytochemistry. 2011;72(17):2165–2171. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]