Executive Summary

Around the world, populations are ageing at a faster pace than in the past and this demographic transition will have impacts on all aspects of societies. In May 2020, the UN General Assembly declared 2021–2030 the Decade of Healthy Ageing, highlighting the importance for policymakers across the world to focus policy on improving the lives of older people, both today and in the future. While rapid population ageing poses challenges, China’s rapid economic growth over the last forty years has created space for policy to assist older persons and families in their efforts to improve health and well-being at older ages. As China is home to 1/5 of the world’s older people, China is often held up as an example for other middle-income countries. This Commission Report aims to help readers to understand the process of healthy ageing in China as a means of drawing lessons from the China experience. In addition, with the purpose of informing the ongoing policy dialogue within China, the Commission Report highlights the policy challenges on the horizon and draws lessons from international experience.

The uniqueness of China’s ageing society

From a global perspective, China shares some of the economic and social challenges faced by other countries with rapidly ageing populations. China stands out, however, as it already has the world’s largest older population, and China’s ageing burdens will increase further as the ‘second baby boomers’ (those born between 1962 and 1975) start to enter retirement in 2022. In addition, China’s rapid demographic transition over the last four decades will lead to a dramatic decline in the number of living children for each older person in China and bring substantial challenges for both family-based care and social care. Compounding demographic changes, personnel planning in geriatric and rehabilitation medicine has not kept pace with the growth of the older age population, and there is a shortage of medical resources targeted at the ageing population. In Section 1, the report stresses the importance of achieving “healthy ageing” in light of socio-economic progress, urbanization and migration, and China’s demographic transition.

Health complexity and inequalities among China’s older population

China completed its epidemiological transition from infectious diseases to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) during the past three decades. As in many other ageing countries, the upward trend in the incidence of NCDs and the presence of multimorbidity pose special challenges for China’s healthcare sector. Even as some older Chinese continue to suffer from such communicable diseases as hepatitis, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted diseases, chronic conditions, such as cognitive impairments, mental disorders, and frailty, are becoming much more prominent. These chronic conditions are complex to treat and manage and are associated with more functional disability and greater care needs. Along with the emergence of NCDs, substantial gaps in health are apparent by gender, rural versus urban residence, ethnicity, and socio-economic status. Investments in healthy ageing, from promoting education in health literacy to improving access to health care, are promising means of improving the well-being of older adults and reducing the gaps in health across socioeconomic groups in China. Even as China’s population ages, investments in healthy ageing offer a path for older Chinese to play meaningful and productive social roles in society, while limiting burdens on their families. The latest facts on health status and health inequities among China’s older adults are presented in Section 2 of the report.

Modifiable factors of healthy ageing: Evidence from China.

Current evidence on the determinants of health and functioning status of China’s older population is summarized in Section 3. In China, as elsewhere, health at older ages results from the cumulative effects of behaviours and events that occur across the life cycle. These include exposures to unhealthy environments and parental decisions influencing in-utero and childhood health, later health behaviours as teenagers and adults (including decisions on educational investments, smoking, drinking, and physical activity), and decisions over food consumption which influence diet and nutritional status. Many of these decisions and behaviors are influenced by health literacy and socio-economic conditions, but they may also be influenced by policy (Section 5). Finally, Section 3 highlights the health benefits of social connections and participating in leisure activities such as square dancing and promoting age-friendly environments in China.

Integrating medical and social care for Chinese older people.

Older people require access to high-quality health services that include prevention, promotion, curative, rehabilitative, palliative and end-of-life care. An update on China’s policy initiatives regarding healthcare and social care relevant to the ageing population is provided in Section 4. In addition to achieving universal health insurance coverage, China has invested heavily in public health promotion and the consolidation of the primary healthcare system. Further, as the role of the family in providing care for older people is eroded by dwindling family size and changing living arrangements, especially with the outmigration of adult children, China is taking steps to build up institutional and community care infrastructure as both a substitute for, and complement to, family care. Furthermore, long-term care insurance (LTCI) has been piloted in many cities as a financing mechanism. China’s experience with the LTCI pilots suggests that it will be difficult to sustain LTCI under the current pay-as-you-go framework, and that there will be a considerable public financial risk as the population ages. Although China’s government has placed the integration of health care with long-term care (LTC) at the forefront of its policy agenda, the progress for the integration has been slow.

Lessons learned from China and implications for the future.

An overview of the evidence presented earlier in the report is presented in Section 5, followed by policy recommendations for supporting healthy ageing in China. Policy recommendations outlined here can be generalized to other countries, especially low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). First, health promotion initiatives should focus on changing people’s behavior, especially smoking cessation, weight control, and health literacy education to reduce the incidence of NCDs and care burdens. Second, there is an urgent need to move away from disease-centred care to person-centred care and to increase the supply of health care workers, particularly in geriatric medicine, rehabilitation medicine, and hospice care. Third, innovative measures should be taken to remove obstacles to upgrading community and home environments and thus facilitate mobility and social engagement among older people.

There are several other policy areas that should be addressed, given China’s unique institutional environment. These include regional segmentation of health insurance systems and the regulatory environment for healthcare delivery. Specifically, the report suggests that policy in China should focus on: (1) national integration of the health insurance system to eliminate the current segmentation across regions and occupations; (2) capping regionally segmented LTCI initiatives, and striving for a national scheme that is independently funded; (3) switching government subsidies in the aged care sector from subsidising providers to subsidising consumers to facilitate market competition and to help existing care facilities to meet safety regulations; (4) strengthing the capacity to regulate medical service providers, especially in screening for fraud against the national medical insurance schemes and reforming the healthcare delivery sector by lowering barriers to entry and facilitating choice.

Older people are an important part of a family and an invaluable asset to society. Healthy ageing will not only enable older people to enjoy their later life to the fullest but has the potential to unleash the intellectual and vocational capacities of society as a whole. Recognizing that China’s older population will continue to grow, it is important to take their needs into account and prepare well in advance by creating an age-friendly environment for the ageing population. As China’s “second baby boomers” start to reach retirement age in 2022, it is imperative to take the window of opportunity afforded by China’s economic growth to make coordinated efforts across sectors to address the concerns of an ageing nation.

Section 1. Introduction

The Chinese population has aged and will continue to age rapidly for decades. In 2021, 14.2% of China’s population was 65 and older, implying that China doubled the share of its older adults aged 65 and over from 7% to 14% in 21 years. In contrast, high-income countries (HICs) took about half a century to double this share.1 By 2065, China will become the oldest country among the twenty most populous countries globally.2 China already has the world’s largest number of older people, and the number is growing. By 2050, there will be 395 million people aged 65 and older in China, equivalent to 1.2 times the current population of the United States (US). The oldest old, 80 and older, will reach 135 million and exceed the current population of Japan.2

As in the rest of the world, declining fertility and rising life expectancy have both contributed to population ageing in China. The total fertility rate was 6.1 in 1950–55; in 2020, it was 1.3. The total number of births reached a record low of 10.62 million in 2021, and net population growth was merely 0.48 million. Meanwhile, life expectancy at birth went from 44 years in 1950–1955; in 2021, it was 78.20 years.

A rapidly ageing population poses serious economic challenges. An ageing society can only be supported if the economy is growing successfully. A growing economy depends on a flourishing working-age population. When retirement age stays fixed, the number and proportion of the working-age population will decline, draining the economy of the productive labour force. With pay-as-you-go social security systems, which dominate almost all countries, rising retiree-to-worker ratios will either lead to a large and growing deficit in social pension programs or an increasing financial burden on the current working-age population. Health care financing will also be strained since older people tend to use health care services at disproportionally higher rates. Furthermore, older people, particularly those who are unhealthy, require more long-term care (LTC) than younger people, which adds to private and public financial and instrumental care burdens.

In the absence of coordinated investments in healthy ageing, the rate of demographic change in China implies that the economic and social challenges associated with population ageing could be greater for China. The old-age dependency ratio, defined as the ratio of people aged 65 and older to those aged 20–64, is expected to more than triple from 0.18 in 2019 to 0.55 in 2050.2 The social security system in China, which recently expanded to cover the rural population, is highly fragmented. People living in rural areas receive very little pension support and live well below the poverty line. China faces greater fiscal pressures to meet obligations for a viable social security program that provides economic security for older adults, and that burden is expected to rise rapidly. The Chinese family traditionally took care of their older parents and other relatives, but decreases in fertility over the last 40 years have put pressure on traditional arrangements, and in rural areas and small towns, family capacity to provide instrumental care is further eroded by the out-migration of working-age adults.

Can China solve the ageing problem by adopting radical pro-natalist policies to drive up birth rates and/or to increase immigration to supplement below-replacement fertility? For a country the size of China, the role of immigration will be minimal. The Chinese government officially terminated the one-child policy in 2015 and further permitted three children in 2020, coupled with a pledge to provide incentives for childbirth. However, many countries have tooled with pro-natalist policies in the past, and very few are effective. Even if fertility can rebound a little, it cannot stop the trend of population ageing, as continued advances in life expectancy will drive future ageing.

Even so, amid the doom and gloom of population ageing, the prospect of healthy ageing provides a reason for optimism. Healthier older adults will be physically able to delay retirement, converting an otherwise dependent population into a productive workforce that contributes to the economy. In so doing, they also delay taking social security, alleviating the adverse effects of the support ratio on the social pension system. In addition, improved health during old age can reduce the demand for healthcare services and lead to healthier older persons who can live independently for longer and require less care from family and society. Further, healthy older persons contribute to families and communities as providers of care and mentoring for children, which may facilitate an increased labor supply for working-age parents. As a result, policymakers in any country facing an ageing population would be wise to implement integrated policies to promote healthy ageing.

Under an ideal setting, healthy ageing would be reflected in a compression of morbidity, i.e., older adults living longer would live for more years in a healthy state and fewer years in an unhealthy one. There is evidence of morbidity compression in HICs, but limited evidence has been found in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).3

Longevity does not guarantee good health in old age. People may live into old age against all odds but still bear the marks of past assaults on their bodies and minds. With the population ageing, China has shifted from a mortality pattern dominated by acute infectious diseases to chronic diseases. Thus, reducing mortality and improving the health of older adults will require a greater emphasis on controlling chronic diseases and the occurrence of multiple chronic conditions.

Healthy ageing, however, is more than just freedom from disease. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), healthy aging is more than just the absence of disease; it is the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age.4 The Chinese Geriatric Association defines healthy ageing in five dimensions: free from major chronic diseases, without cognitive impairment, taking part in family and social activities, retaining functioning ability, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle.5 The key to healthy ageing is maintaining functional ability despite having chronic conditions. Subjective measures of well-being play an equally important role in healthy ageing. As such, the first goal of this report is to describe the health status, functional abilities, and subjective well-being (SWB) of older people in China (Section 2).

Understanding the determinants of health and functional status at older ages is essential to promoting healthy ageing. A better understanding of the health and functional status of older people in China will help the government develop well-designed interventions to improve older adults’ health and functional abilities. Thus, the second goal of this report is to present analyses about the determinants of health and functional status, with particular focus on those that may be modifiable (Section 3). This report takes a life-cycle perspective in understanding how interventions long before old age contribute to healthy ageing since health in old age reflects health-enhancing investments and negative perturbations to health over a lifetime.

Government has an important role to play in promoting healthy ageing. Even when health policies promulgated by China’s government do not explicitly target the health of older people, they have substantial impacts on health at older ages. One example is the expansion of health insurance coverage for the whole population. Other examples include establishing a national public health infrastructure, strengthening primary care, and implementing the clean air act. Some policies, such as integrating medical and social care, promote health services for older people. In addition to health care, social care for older people is also a necessary investment. Traditionally, Chinese families have taken care of their older members. However, caregiving may have adverse effects on family caregivers; some care needs, inevitably, may not be met under traditional family care. The Chinese government has implemented policies to enhance and support family care with social and institutional care. Although long-term care insurance (LTCI) provides funding for aged care, it can be expensive if improperly designed. We will review the progress in efforts in healthcare and social care in Section 4.

We summarise the evidence presented earlier in the report and provide the outlook and policy recommendations for healthy ageing in China. The policy recommendations target three main fields: enhancing an age-friendly environment and healthy behaviors, advancing useful innovations to current healthcare systems, and improving the LTC and insurance, which address the care needs of ageing populations in China (Section 5).

There are two concurrent cross-cutting themes throughout the report: inequity between urban and rural China and disparities between men and women. The disparities are generally evident in every section of the report. Older people’s health and functional status differ dramatically between urban and rural areas, as do health behaviors and the social and environmental factors that influence health. Further, while China’s government has made considerable efforts to improve access to high-quality health care for the rural population, substantial differences persist, and these are also manifest in differential access to LTC. There are also gender differences in health outcomes and health behaviors. Women tend to live longer than men, so their care needs are also more likely to be unmet since they have less access to high-quality care from within the family.

Beyond this introductory section, this report consists of four detailed sections. In Section 2, we describe the health and functioning status of older people in China, followed by Section 3, which discusses factors that can be modified to influence the health of older people. In Section 4, we overview the previous healthcare and social care policies that directly or indirectly promote healthy ageing. Finally, section 5 proposes the outlook and policy recommendations dedicated to health promotion for older people in China.

Section 2. Health status

2.1. Life expectancy and causes of death

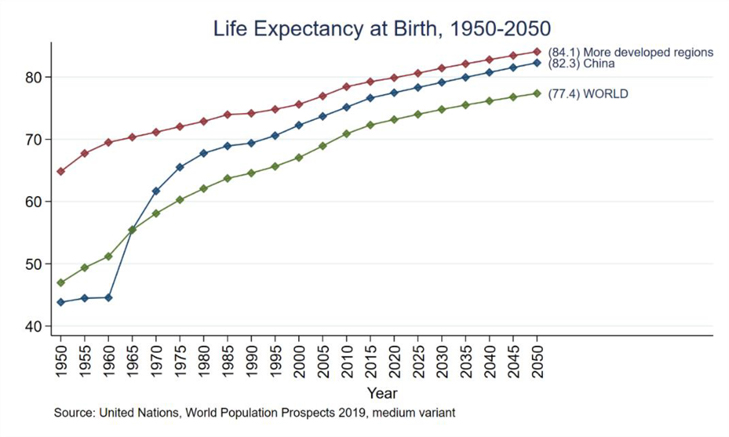

Life expectancy in China has increased significantly since the People’s Republic of China was founded (Figure 1). In the 1960s and 1970s, public health campaigns and universal basic medical care led to the greatest gains in life expectancy. Beginning in the early 1980s, China’s economic reforms reduced poverty and improved living standards considerably, altering disease patterns and closing the life expectancy gap with HICs.

Figure 1: Life expectancy at Birth, 1950–2050.

Source: United Nations, World Population Prospects 2019, medium variant

Reducing infant mortality has largely contributed to an increase in life expectancy. In China, several national programs reduce maternal mortality and eliminate neonatal tetanus.6 Infectious diseases have also been controlled through medical innovations such as immunization and antibiotic therap.7 Based on the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, life expectancy in China improved from 1990 to 2013 due to reductions in diarrhea, lower respiratory infections, neonatal disorders, and cancer.8

During the 1990s and 2000s, China completed its epidemiological transition from infectious diseases to non-communicable diseases (NCDs). The age-standardised mortality rate decreased by 74.1% for communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases, higher than that for NCDs (35.7%).8 Between 1990 and 2017, communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases decreased by 1.2 million. Lower respiratory infections ranked first in 1999, but ranked 12th in 2017.9 However, deaths from NCDs rose from 5.9 million to 7.9 million. The most common NCDs, including stroke, ischemic heart disease, cancers, and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD), have become the leading causes of death in China since the 1990s.9

2.2. Chronic conditions and Infectious Diseases

2.2.1. Chronic conditions

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

China’s prevalence and mortality of Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) have increased substantially due to several reasons including high caloric diets and sedentary lifestyles. It was estimated that 230 million people suffered from CVD in 2007; by 2018, that number had increased to 290 million.10 CVD is China’s leading cause of death, accounting for over 40% of all deaths. As per the China Statistical Yearbook, CVD deaths accounted for 43.5% of mortality in urban areas and 45.9% in rural areas, with 265.11/100,000 deaths for heart disease and 126.41/100,000 deaths for cerebrovascular disease in urban areas and 161.18/100,000 deaths for heart disease and 158.15/100,000 deaths for cerebrovascular disease in rural areas.11

Stroke is also among the leading causes of death. According to the National Epidemiological Survey of Stroke in China (NESS-China), stroke prevalence in 2013 was 42.6% (men 47.1%, women 38.3%), 66.7% (men 75.1%, women 58.8%), and 59.7% (men 73.9%, women 48.1%) in those aged 60–69, 70–79, and 80 years old or older.12 First attacks have increased from 1,890 per million population (PMP) in 2002 to 3,790 in 2013, with an overall annual increase of 8.3%.13

Coronary heart disease (CHD) contributes to most cardiac deaths in China, and around half of CHD deaths are caused by acute myocardial infarction (AMI).10 From 2013 to 2017, cardiac mortality doubled in rural areas and exceeded that in urban.10 The mortality rate of CHD in 2017 was 1153 PMP in urban areas (1181 PMP compared to 1125 PMP for men and women) and 1220 PMP in rural areas (1257 PMP compared to 1183 PMP for men and women).11

Hypertension

Chinese hypertension prevalence has risen steadily since 1991. From 2012–2015, the China Hypertension Survey found that prevalence rates of hypertension were 44.6%, 55.7%, and 60.2% among people aged 55–64, 65–74, and ⩾75, respectively, and were higher among men (24.5% vs. 21.9% for women).14 Not surprisingly, hypertension is more prevalent among the older population. One study found a U-shaped association between SBP and all-cause mortality among respondents aged 80 or older. A study of oldest-old respondents found a U-shaped correlation between SBP and mortality. Among those with a SBP between 107 and 154 mm Hg, higher SBP (>154 mm Hg) was associated with CVD mortality, and lower SBP (<107 mm Hg) with non-CVD mortality. Older adults over the age of 80 may not benefit from current blood pressure guidelines.15

In rural areas, access to health care has been a major problem in diagnosing and treating hypertension. Improvements have been made in recent decades. Among hypertensive patients, hypertension awareness increased from 26.2% in 1991 to 46.9% by 2015. Treatment rates rose from 12.1% in 1991 to 40.7% in 2015.14 Rural improvements were even more impressive. Rural vs. urban awareness rates were 13.9% vs. 35.6% in 1991, narrowing to 44.7% vs. 50.9% in 2015. For treatment, the rural vs. urban rates were 5.4% vs. 17.1% in 1991, narrowing to 38.0% vs. 45.8% in 2015.14 Despite this progress, control rates remain low. Only 19.4% of urban and 13.1% of rural patients successfully controlled their blood pressure in 2015.14

Diabetes

Diabetes is increasingly prevalent in China, especially among older persons.16 Deaths from diabetes rose from 19th place in 1990 to 8th place in 2017.9According to a recent national survey, 27.8% of adults aged 70 and over had diabetes in 2018.17 Another national survey reported the weighted prevalence of diabetes in older adults aged 60–69 and 70 or older were 28.8% and 31.8%, respectively.18 In 2011–2012, the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) reported 17.4% prevalence rate of diabetes (16.9% vs. 17.9% for men and women, 23.9% vs. 14.8% for urban and rural).16

Rural diabetes rates are rising faster than urban rates. In 1997, rural areas had lower diabetes and Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT) prevalence rates than urban areas (rural vs. urban diabetes rate: 1.7%–2.7% vs. 3.3%–4.6%; IGT: 3.1%–5.0%).19 Although rural residents still have a lower prevalence of diabetes (9.5% rural vs. 12.6% urban in 2013), rural residents have a relatively high prevalence of prediabetes (37.0% vs. 34.3%).20

According to CHARLS 2011 data, awareness of having diabetes was 40.7% (37.3% vs. 44.0% for men and women, 52.9% vs. 32.6% in urban and rural).16 However, diabetes awareness and treatment rates remain problems in China despite much stronger health campaigns since 2009.16 Treatment rates increased from 25.8% to 32.2%, and control rates among treated patients increased from 39.7% to 49.2% from 2010 to 2013.20 The management of diabetes in rural areas is much more challenging. Diabetes management in rural areas is more challenging. In 2013, the awareness, treatment, and control rates in rural areas were 29.1%, 25.2%, and 42.3%, significantly lower than in urban areas (43.1%, 38.4%, and 53.3%, respectively).20

Obesity and overweight

Overweight and obesity are associated with increased morbidity and CVD mortality.21 Rapid economic growth has led to changes in dietary and physical activity levels, leading to obesity and overweight in China.

Obesity prevalence rose from 3.1% in 2004 to 8.1% in 2018, according to the China Chronic Disease and Risk Factors Surveillance.22 Urban BMI and obesity prevalence has declined significantly since 2010, and moderately in rural men, but rural women’s prevalence has continued to rise. The CHARLS 2015 wave found that older women were more likely than men to be overweight/obese. The obesity prevalence among men (women) 60 and older was 3.0% (5.7%), and the central obesity prevalence was 8.0% (47.1%). People with non-agricultural hukou were more likely to be overweight (41.7% vs. 29.1%), obese (5.9% vs. 3.7%), and have central obesity (30.6% vs. 26.3%). The illiterate are more likely to be overweight, but less likely to be obese or have central obesity.

Chronic Kidney Disease

In 2016, chronic kidney disease (CKD) was the 16th most prevalent cause of Years of Life Lost (YLLs) in China, and it is anticipated to become the 5th most prevalent by 2040.23 According to a national survey in 2010, the prevalence of CKD was 10.8%. The prevalence was higher in rural areas (11.3% vs. 8.9% in urban areas) and among women (12.9% vs. 8.7% among men).24 Due to the rise in diabetes and hypertension, CKD has become more prevalent. According to a study using the National Hospital Quality Monitoring System database, diabetes-related CKD has overtaken glomerulonephritis as the most common cause of CKD.25 Diabetes-related CKD increased from 19.5% to 24.3% from 2010 to 2015, and hypertension-related CKD increased from 11.5% to 15.9%.25

Due to the disease’s silent nature, awareness of CKD was only 12.5% in 2010 despite its high prevalence rate.24 Previous studies suggest that screening for persistent albuminuria among high-risk populations could be a cost-effective strategy for early detection.26

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

In 2017, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was China’s third leading cause of mortality.9,27 COPD incidence increased from 8.2% in 2004 to 13.6% in 2015 in China with industrialisation and air pollution.27,28 There was a higher prevalence among men than among women (19.0% vs. 8.1%). COPD prevalence was highest in southwest China (20.2%) and rural areas (14.9% vs. 12.2% in urban areas).27

At less than 3%, the awareness of COPD is extremely low.27 In COPD, only 5.9% of patients were tested by spirometry, a standard diagnostic test.27 Although the current diagnostic situation is still not optimal, there has been a significant increase in early-stage COPD diagnoses since 2004.27,28 The assessment of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stratification found that more COPD patients in stage I (mild disease) were diagnosed in 2015 while more patients in stage II (moderate disease) were diagnosed in 2004.27,28

Cancers

According to the Cancer Registration in China, although the crude cancer mortality rate rose from 74.2 per 100, 000 in 1973–75 to 170.1 per 100, 000 in 2015, age-standardised death rates declined from 94.4 per 100, 000 in 1990–92 to 77.9 per 100, 000 in 2015, indicating that much of the increase in the crude rate is associated with an ageing population.29 According to a multicenter study conducted in China, cancer is the leading cause of hospitalization among older inpatients, followed by hypertension, ischemic heart disease, diabetes, and cerebrovascular disease.30 China’s top five cancers in 2020 were lung cancer, stomach cancer, colorectum cancer, liver cancer, and breast cancer.31 For men, lung cancer was the most common type (n = 0.54 million), and to women, breast cancer was the most frequent type (n = 0.42 million).29,31 In 2013, cancer incidence was lower in rural than urban areas (182.4 vs. 189.9 per 100,000), but by 2015 it reversed (213.6 in rural vs. 191.5 in urban, per 100,000).32 Higher measured incidence may also be due to improvements in early detection and screening in rural areas.

The 5-year survival rate for all patients with cancer in 2012–15 was higher in urban areas (46·7%) than in rural areas (33·6%). The geographical disparities narrowed. As compared to 2003–05, rural cancer patients showed greater survival increases than urban cancer patients, with the survival gap declining from 17.7% in 2005–05 to 13.1% in 2012–15.33

Multimorbidity

Multimorbidity is more common among older adults as chronic disease becomes the dominant health concern. UK Academy of Medical Sciences defines multimorbidity as the coexistence of at least two chronic conditions, each of which must be an NCD, a mental health disorder, or an infectious disease with long duration.34 The neglect of multimorbidity and the treatment of each condition separately leads to excessive healthcare use, inappropriate polypharmacy, and conflicting treatments.35

It is interesting to note that multimorbidity prevalence is lower in LMICs than in HICs. There is a likely underdiagnosis of chronic diseases in these LMICs. China had the lowest multimorbidity prevalence among those aged 50–59 (including India, Ghana, Mexico, Russia, Poland, South Africa, Finland and Spain) according to a multi-country study. It is likely that this finding is due to nonrandom sampling in China, which results in a higher proportion of healthy participants.36

A CHARLS study with combined three waves (2011, 2013, and 2015) found a multimorbidity prevalence of 42.4% among participants 50 years and older, which was higher among urban residents (43.7% vs. 41.0% in rural areas) and women (45.6 vs. 39.6% among men). Relying on self-reports alone may lead to an undermeasurement of multimorbidity.37 Reliance on self-reports alone may well lead to under-measurement of multimorbidity, as suggested in a recent study. This study analyzed measured hypertension and blood biomarkers associated with a few chronic conditions, along with self-reported chronic conditions. According to the study, multimorbidity prevalence was 68.1% using objective measures, but only 47.7% using self-reported conditions alone.38

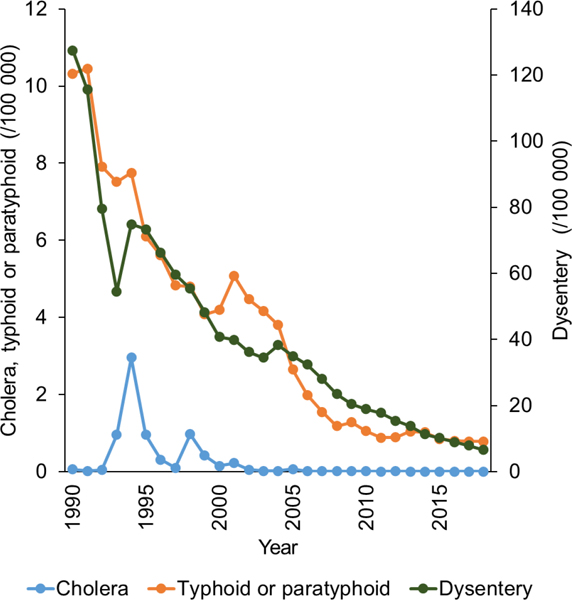

2.2.2. Infectious Diseases

The decline in intrinsic ability and immunity of older adults makes infectious diseases a significant threat to their health in China, despite NCDs becoming the leading cause of death. In China, despite the shift of resources to chronic diseases as a result of population ageing, infectious diseases are still a major threat to the health of older people. In addition to Corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which affects older individuals disproportionately, many other diseases should require attention. In 2019, China reported 3,072,338 cases of infectious diseases of classes A and B.39 In contrast to Class A diseases, which include cholera and plague, Class B diseases include viral hepatitis, tuberculosis, syphilis, and HIV/AIDS, which are common and affect older people disproportionally.40

HIV/AIDS

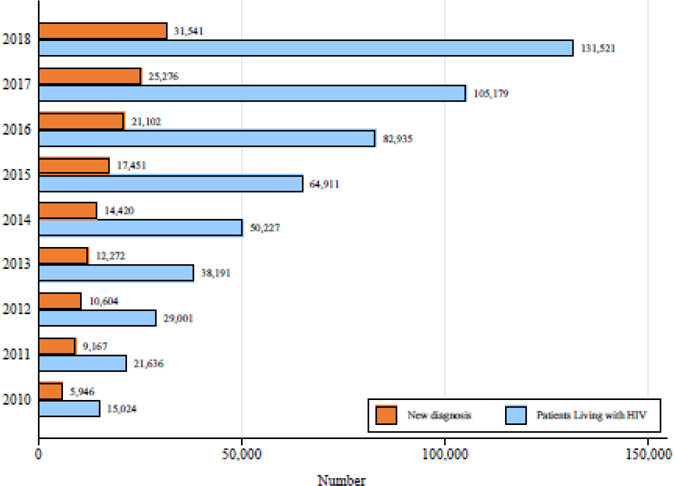

By global standards, China has a very low HIV/AIDS prevalence of under 0.1%, which should be borne in mind during this discussion. HIV transmission in China has shifted significantly from injection-drug-driven transmission to almost exclusively sexual transmission.41 Sexually active young people are frequently viewed as more responsible for HIV transmission. Over the past decade, however, HIV infection through heterosexual transmission has increased significantly among older individuals (≥60 years old), particularly older males, increased significantly over the past decade.41 The number of newly diagnosed HIV cases among older people increased from 5,946 in 2010 to 31,541 in 2018 (see Figure 2). The share of older heterosexual males among newly diagnosed HIV cases has increased from 7.4% in 2010 to 16.5% in 2018.42 China may have late diagnosis for some of these new cases among older people, but this is not the whole story. Researchers in Guangxi found that older males have a higher HIV infection risk than younger males, based on repeated HIV screenings of the population.43 An increase in infection among older males may be related to the rising popularity of erectile dysfunction medication (EDM) and less expensive illegally manufactured aphrodisiacs. Researchers have found that older Chinese men who engage in low-cost commercial sex and do not use condoms are more likely to contract HIV and other sexually transmitted infections when using EDM or aphrodisiacs.44 It is imperative to focus on prevention and testing interventions in this vulnerable group of older adults.

Figure 2. The number of HIV infections among older people (≥60) in China from 2010 to 2018.

Viral Hepatitis, Tuberculosis, and Syphilis

Virus hepatitis, tuberculosis, and syphilis affect older people disproportionally. In 2019, people aged 60 and older accounted for 18.1% of the total China’s population, but accounted for 24.9%, 22.5% and 34.5% of total viral hepatitis, viral hepatitis B, and viral hepatitis C cases, respectively.45 Similarly, tuberculosis and syphilis among those 60 and older accounted for 34.6% and 32.3% of total cases, respectively.45 The higher tuberculosis infection rates in older people may be due to their weakened immune systems, while the higher viral hepatitis C infection rates may be due to their more extensive use of blood infusions in medical treatments. As syphilis and HIV cases increase among older people, it indicates that older people are more sexually active than previously thought.

COVID-19

Globally, COVID-19 has infected disproportionately older people, and clinical severity and case-fatality ratios are significantly higher among older adults than among youth.46 In China, the incidence of COVID-19 among people 60 years and older was two times higher than for people under 60 years of age. Case-fatality ratios were less than 1% for those under the age of 50, 3.1% for those between the ages of 50 and 59, 8.2% for those between the ages of 60 and 69, 18.5% for those between the ages of 70 and 79, and 32.1% for those over the age of 80.47 Meanwhile, older age was associated with a lack of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination.48

2.3. Mental Disorder and Cognition Impairment

2.3.1. Depression and Depressive symptoms

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a pattern of behavior or mental experience that results in significant distress or functional impairment. Depression (major depressive disorder) is one common and serious mental disorder. Globally, depression is a major cause of death in old age. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) estimates that loss of Disability-adjusted life year (DALYs) from major depression increased from 634 (ranked 20th) per 100,000 in 1990 to 675 (ranked 14th) per 100,000 in 2017, and 779 (ranked 20th) per 100,000 in 2017.49 According to the China Mental Health Survey (CMHS, 2012–15), lifetime depressive disorder prevalence was 7.3%, while 12-month depressive disorder prevalence was 3.8%.50 Chinese people aged 60 and older reported 3.0% major depressive disorder over the past 12 months.51

As different instruments (e.g., Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [CES-D], Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HAM-D], Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9], and Geriatric Depression Scale [GDS]) are used in different studies, estimates of depressive symptoms among older Chinese vary greatly. Zhang et al. found that older Chinese had a pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms of 22.7% (95% CI: 19.4–26.4%).52 According to an updated meta-analysis, 19.9% of those 60 years and older in China reported depressive symptoms (95% CI: 13.9% - 28.6%) in 2011–2012.53 According to both meta-analyses, depressive symptoms are more prevalent in women (23.9%) than men (19.3%), and in rural (25.2%) than urban areas (20.6%). Furthermore, depressive symptoms decrease monotonically with education. There was no apparent age trend.

A ten-question version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CESD-10) scale is used in the CHARLS data to measure depressive symptoms. Based on the 2018 CHARLS data, 42% of Chinese women and 29% of men showed elevated depressive symptoms. For both genders, rural residents have a higher prevalence (32% vs. 22% for men and 47% vs. 30% for women). Depressive symptoms grow monotonically with age among rural but not urban people. Illiterate adults suffer from 47.8% of depressive symptoms, while those with high school education and above have a prevalence of 20.9%.54 Depressive symptoms are associated with chronic pain in older adults. A CHARLS study found a positive correlation between pain severity and depressive symptoms.55

Anxiety disorders often accompany depression in older adults due to fears of falling, being unable to afford living expenses and medication, being victimized, being dependent, being alone, and being left alone.56 Older Chinese also experienced greater anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. The prevalence rates of anxiety symptoms among COVID-19 infected, healthy, and chronically ill individuals were 14%, 23%, and 85%, respectively, suggesting that we should pay particular attention to anxiety symptoms of older patients with chronic diseases during outbreaks.57

At its worst, depression can lead to suicide. Chinese suicide rates were among the lowest globally in 1999 with 5.29 per 100,000. Chinese older people, however, rank the third in the world.58 Chinese suicides show unique demographic patterns with age: the older group (aged 65 years and over) has the highest rate (44.3 to 200 suicides per 100,000), four to five times higher than the general population.58 Over the past three decades, suicides among older adults have decreased significantly. The national suicide rate of older adults significantly decreased from 76.6 in 1987 to 30.2 per 100000 in 2014: suicide rates among older adults decreased from 76.6 in 1987 to 30.2 in 2014.59

2.3.2. Dementia and Cognitive Impairment

The normal cognitive ageing process is associated with declines in cognitive abilities, which affecting decision making in late life’s daily living. It may be possible to achieve successful cognitive ageing by participating in certain activities, building cognitive reserves, and engaging in cognitive retraining. Some normal cognitive ageing may develop mild cognitive impairment and dementia over time.60

Dementia is a chronic disease primarily affecting older people that causes almost irreversible cognitive decline. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD) are two of the most common causes of dementia. According to a multi-center survey of residents aged 65 or older conducted between 2008 and 2009 in China, dementia, AD, VaD, and Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) are prevalent to 5.14%, 3.21%, 1.50%, and 20.8%, respectively.61,62 In rural areas, dementia, MCI, and AD, but not VaD, were more prevalent than in urban areas, and differences in education may explain this.61,62 In 2013, there was a 5.56% prevalence of dementia among people aged 65 and above.51 Among people aged 60 and over recruited between 2015 and 2018, an age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of dementia was estimated at approximately 6.0%.63 China’s dementia surveys consistently show that it is highly prevalent.

MCI prevalence was found to be 12.7% (95% CI: 9.7% - 16.5%) in a meta-analysis of 22 community-based studies.64 According to another meta-analysis of 36 studies (total N = 114,592), community-dwelling adults aged 55 and older had a 14.5% prevalence of MCI (95% CI: 12.8% - 16.2%).65 MCI increased gradually between 2001 and 2015 (7.5% in 2001–2003, 12.1% in 2004–2006, 13.1% in 2007–2009, 16.9% in 2010–2012, and 19.5% in 2013–2015). There are considerable differences by geography. Shaanxi had the highest prevalence (20%–25%), followed by Inner Mongolia (15%) and Shanghai (10%). MCI prevalence increases with age and is highest among those over 90 (23.5%). There are significant differences in demographic characteristics; the prevalence is higher among women (16.0% vs. 12.6% in men), unmarried (16.4% vs. 13.1%), and rural residents (18.2% vs. 13.6%). Those with more education also have a lower prevalence of MCI: illiterate individuals had the highest prevalence (24.0%), followed by primary school students (20.1%), and higher education students (8.0%).63

2.4. Functioning independency and Disability

Although chronic illnesses can be debilitating, they do not necessarily cause one to lose independence when adequately treated and managed. Indeed, maintaining functionality despite having one or more chronic conditions is fundamental for healthy ageing.

2.4.1. Functioning independency

Functional independency is the ability to perform basic and instrumental activities of daily living. Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) measure the ability to carry on essential activities of functional living, and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) measure the ability to live independently in a community. Using the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS), a longitudinal study with samples mostly in eastern provinces, IADL and ADL disability prevalence among those aged 60 and older declined from 1997 (38.9% and 13.2%) to 2006 (26.6% and 9.9%).66,67

CHARLS collected data regarding the functioning dependency in terms of ADLs and IADLs. ADLs include dressing, bathing, eating, using the toilet, getting in or out of bed, and continence; IADLs include cooking, shopping, making phone calls, managing money, doing housework, taking medications, and taking public transportation. According to a recent CHARLS study, those requiring help among the over 60 population, as indicated by ADLs, declined from 11.7% to 8.1% from 2011 to 2020. If determining care needs using both ADL and IADL items, the share requiring help declined from 24.5% to 17.8%.68 Disability prevalence has declined over the last few years due to improved educational attainment, age-friendly environments, and healthcare access. In 2011, the estimated number of people needing ADL/IADL help was 45.3 million and this number remained constant – the decline in the share of the population with disability and requiring help was offset by a larger population base and growth in older populations who were aged 60 years old and above.

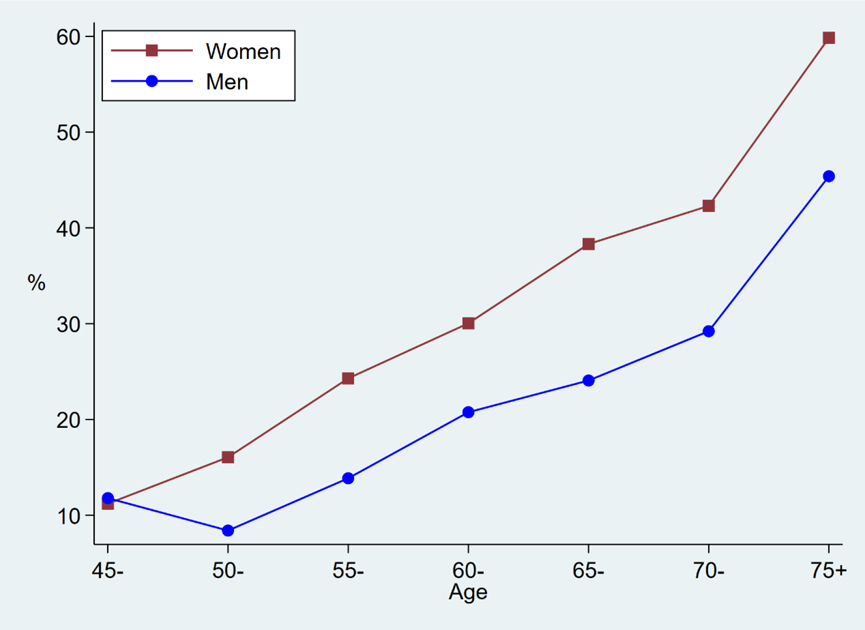

The ADL/IADL disability prevalence increases sharply with age (Figure 3). The prevalence of disability is higher among agricultural than non-agricultural hukou holders. An education gradient is evident: disability prevalence in 2020 is 49.2% among illiterate older adults, and 13.0% among those with high school degrees or more.

Figure 3: Disability rates by age and gender from CHARLS 2020 data.

2.4.2. Frailty and Sarcopenia

Frailty, another major risk factor for functional dependency, is a clinical syndrome characterised by the decline in the physiological capacity of multiple organ systems, resulting in increased susceptibility to stressors.69 Worldwide, there are two main frailty assessment methods, based on different conceptual models. Fried frailty phenotypes (FFPs) underlie phenotypic models. It suggests frailty is a syndrome characterized by physiological and metabolic changes. FFP determines frailty by three or more characteristics: weakness, slow gait speed, low physical activity, exhaustion, and unintentional weight loss. A second method is the frailty index (FI), which takes into account signs, symptoms, and diseases to analyze frailty. FI indicates how many potentially unhealthy measurement indicators there are in their physical, social, cognitive, and psychological measurements.70 The number of indicators and cut-off value of FI may vary depending on the research purpose. As an example, Li et al. constructed an FI consisting of 28 indicators based on CKB,71 while Gu et al. built an FI with 38 indicators based on Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS).72 Frailty prevalence varies due to differences in measures. Chinese older adults aged 65 years in 14 studies showed 8% and 12% frailty prevalence, respectively, in the FFP and FI.73 In a CHARLS study, the prevalence of frailty among 5330 older people aged ≥60 years was 9.6% for the FI in 2011.74 CHARLS also found an incidence of 60.6/1000 person-years of frailty among 4939 community older adults aged 60 and over over an average follow-up period of 2.1 years.75

Sarcopenia and frailty are linked, but distinct, correlates of musculoskeletal aging. Sarcopenia has received considerable attention around the world as an age-related disease. Sarcopenia is defined by the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) 2014 consensus as “aging-related loss of muscle mass, weak muscles, and/or low physical performance.”76 In the AWGS 2019, the diagnosis and treatment of sarcopenia were updated. AWGS 2019 provides two assessment/diagnostic criteria for community and clinical settings. The AWGS 2019 introduced the concept of “possible sarcopenia”, defined as low muscle strength or physical performance in the community. 77

There was a 12.9% prevalence of sarcopenia in men and 11.2% in women in a meta-analysis of 24,879 community-dwelling Chinese older adults aged 65 years, based on AWGS 2014 criteria.78 A recent CHARLS study found a prevalence of 38.5%, 18.6%, and 8.0% of possible sarcopenia, sarcopenia, and severe sarcopenia, respectively.79

2.4.3. Falls and Fractures

Older Chinese are at risk of fall-related injuries, a major cause of disability. In China, the number of DALYs caused by falls increased from 27th in 1990 to 17th in 2017.9 Based on GBD data, the estimated incidence rate of falls among people aged 60 years and older was 3799.4 per 100 000.80 The WHO Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) project in China reported that the incidence of fall-related injuries in the past year was 3.2% among adults 50 and older in 2010.81

In China, falls are the leading cause of injury-related mortality and traumatic bone fractures among older people.82 Over the past two years, a CHARLS study reported that 15.9% of men and 24.5% of women 60 and older experienced falls in 2015; among them 8.7% of men and women suffered serious falls. In comparison to older people with non-agricultural hukou, older people with agricultural hukou suffered more falls (21.3% vs. 18.1%) and fall-related injuries (9.1% vs. 7.6%). The illiterate experience more falls and serious falls than those with at least a high school diploma (24.0% compared to 11.4% for falls and 11.4% compared to 8.7% for serious falls in 2018).

Fractures are also a public health concern because they cause considerable morbidity, excess mortality, great risk of disability, and high societal healthcare costs. According to prospective studies in China, post-fall injuries occur in 60–70% of falls. A systematic review and meta-analysis found 54.95 injuries per 1,000 in mainland China. Of all falls, 10% are major injuries, and 6–8% are fractures.80 Of all fall-related injuries, 10% are major injuries, and fall-related fractures accounted for 6–8% of all injuries. Fall-related hip fractures are often the most serious and costly consequences of a fall. For females, hip fracture incidence rates were 180.72 (95% CI 137.16, 224.28) in 2012 and 177.13 (95% CI 139.93, 214.33) in 2016, and for males, the incidence was 121.86 (95% CI 97.30, 146.42) in 2012 and 99.15 (95% CI 81.31, 116.99) in 2016.83 There is a high prevalence of osteoporosis and fractures in China; 5.0% of men and 20.6% of women over 40 have osteoporosis, and 10.5% of men and 9.7% of women have vertebral fractures.84 China National Fracture Study (CNFS) showed that slips, trips, and falls (57.7%) caused the most fractures in older women and men, followed by traffic accidents (20.4%).85

Falls and fractures can be prevented. Exercise, nutrition, and home safety modifications can reduce falls.86 China has taken concrete measures to prevent falls by hardening rural roads, installing more streetlights, and building handicap access. Additionally, there are programs to provide handrails, anti-slip floors, and remove door sills for low-income families. (more in Section 6, Home Environment and Housing Policy). In 2021, the National Health Commission (NHC) issued 15 guidelines regarding fall risks, modifiable factors, prevention, education, and care for older people who fell.

2.4.4. Self-Reported Pain

Pain is associated with a greater risk of functional decline. Early-life adversity (ELA) such as parental neglect, physical abuse, and social stress can predispose adults to chronic pain.87

The 4th wave of the CHNS in 2008, which measured pain from one of the EuroQol five dimensions (EQ-5D) items: pain/discomfort in the interviewed day, showed that 18.3% of the over 60 population reported self-reported pain.88 According to CHARLS 2018, 67.8% and 53.2% of women and men over 60, reported experiencing pain. Pain is more common in agricultural hukou holders than in non-agricultural hukou holders (63.1% vs. 54.8%). There is a sharp education gradient here, with 48.5% of those with at least a high school education reporting pain, while 67.1% report pain among the illiterate.

2.4.5. Self-Reported Sensory Function

In 2017, sensory organ disease affecting vision and hearing was the third leading cause of years lived with disability (YLDs).9 In 2018, 27.6% of men and 36.3% of women aged 60 and over reported poor eyesight, while 18.2% of older men and 18.8% of older women reported poor hearing, according to CHARLS. Agricultural hukou holders had a higher rate of impaired sensory function (35.6% vs. 23.8% for impaired vision and 20.8% vs. 13.3% for impaired hearing) than non-agricultural hukou holders. Sensory function is also associated with education. Illiterates are more likely than high school graduates to have poor sensory function (42.1% vs. 20.1% have poor vision, 24.3% vs. 11.7% have poor hearing in 2018).

Using sensory aids contributes to the difference in sensory function between agricultural and non-agricultural hukou. Only 13.8% of older people wore glasses, and only 1.0% wore hearing aids. People with agricultural hukou are less likely to wear glasses and hearing aids (9.1% vs. 24.5% for glasses and 0.96% vs. 1.04% for hearing aids in 2018). In 2018, high school graduates are more likely to wear glasses and hearing aids than illiterates (30.9% vs. 6.3% for glasses, 1.0% vs. 0.8% for hearing aids).

2.4.6. Dental Health

Despite eating being vital for physical health, Chinese oral health is poor. Only 23% of older adults brush their teeth twice a day; only 5% use fluoridated toothpaste, and only 6% have had a dental checkup in the last two years.89 Tooth loss is the most important indicator of poor oral health, with edentulism being the extreme case.

According to the CHARLS 2018 wave, 26.0% of people aged 60 and older had edentulism. Women are more likely than men to be edentulous (28.2% vs. 23.7%). In agricultural hukou, 28.8% of those were edentulous versus 19.4% in non-agricultural hukou. Older people rarely see dentists; only 19.1% did in 2015. No obvious gender difference exists in seeking dental care. In 2015, agricultural hukous were much less likely to have dental care than non-agricultural hukous (15.4% vs. 26.1%). High school graduates are less likely to be edentulous and more likely to receive dental care than the illiterate (14.2% vs. 34.5% for edentulous in 2018, 29.3% vs. 14.2% for dental care in 2015).

2.5. Subjective Wellbeing and related conditions

2.5.1. Subjective Wellbeing

An evaluation of subjective well-being (SWB) allows us to sketch a more comprehensive picture of the health status of older individuals.90 Across the world, the age pattern of SWB reports has attracted substantial attention. Typically, a review paper observed a U-shaped age pattern regarding the SWB in 145 countries, the pattern was also found in China.91

A rapid expansion in education across birth cohorts also implies a strong negative correlation between education and age. Since both factors—economic resources and education—improve SWB but decline with age in China, the age profile tends to show an even sharper increase in SWB at older ages: positive cohort effects, in terms of more education and economic resources, tend to reduce the growth rate in SWB among older ages in China. Without those positive cohort effects, SWB would increase at an even more rapid flow at older groups.

A study investigated the relationship between social networks and SWB in China.92 Overall, their analysis indicates that maintaining good social networks in China is associated with better SWB. Concerning kinship relationships, they find the probability of being very happy is 13.8 percentage points higher for married people, while the likelihood of being very satisfied with life is 10.3 percentage points higher. Families with more visits to family and friends during the Spring Festival have a higher sense of well-being and satisfaction with life, and the more frequent such contacts, the higher the life satisfaction they could observe. One notably particular but also interesting finding is on gift-giving/receiving behaviour, the four groups of participants have ranked in terms of happiness and life satisfaction, with the both-giver-and-receiver group first, followed by the only giver second, the only receiver, and the neither group taken the last.

In these associations between SWB and social networks, it is essential to remember that both may be associated with both observable and unobservable dimensions of access to economic resources and vulnerability. While the nature of this association between SWB and economic factors such as wealth, inequality and economic growth and fluctuations, are constant and contested themes in the literature.93

Just as education and economic resources matter for individual happiness and life satisfaction, so are gender and residence. Adult men in China are less satisfied with their lives than women, and adults in urban places are less satisfied with their lives.92 Older women are happier than older men, and those living in cities are happier than those living in villages, although those living in townships do not differ much from those in rural areas.94

2.5.2. Skin conditions, urinary incontinence, and lack of sexual activities

In older individuals, skin and subcutaneous diseases (skin conditions), urinary incontinence and lack of sexual activities are among the most prevalent conditions that do not necessarily cause great physical pains or premature deaths, but can adversely affect the quality of life and SWB.

Skin conditions

Skin conditions are more common among older people because their skin is less oily, less elastic and thinner.95 Eczema, psoriasis, and pruritus are the most common skin conditions among older people. When left untreated, patients scratch the skin, which can worsen the condition. Skin diseases can affect older patients’ physical health, causing pain, sleep disturbance and itching.96

Age-related skin conditions can be easily prevented with emollients and soap substitutes. Because these conditions are not life-threatening, older Chinese tend to view them as nuisances and rarely seek treatment. Epidemiological and prevention studies of skin diseases in older people are rare. One study indicated that skin diseases significantly affect the YLDs. In 2017, there were 7.05 million YLDs due to skin disease, compared to 6.16 million in 1990 as a result of population growth and ageing.97

Studies have revealed that older adults with skin disorders have higher rates of depression, anxiety, inferiority, shame, social barriers, even suicidal tendencies and other negative psychological states.98 It is important to take good care of the mental health of older people with skin diseases, helping them overcome their anxiety and face the disease positively, as this is conducive to the realization of healthy ageing.

Urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence is defined as the involuntary loss of urine. Older women are more likely to experience urinary incontinence due to weak bladder and pelvic floor muscles. In a literature review conducted between 2013 and 2019, 16.9–61.6% of Chinese older women reported urinary incontinence.99 Women predominate (56.3% of females and 35.0% of males) among Chinese rural residents aged 65 years and older.100 Since patients and caregivers lack a proper understanding of urinary incontinence, the actual prevalence rate may be higher than reported.101

Older people may reduce going out due to frequent bathroom needs. In addition, being embarassed by leaking urine leads to a shrinking away from social contacts. Consequently, the person experiences urinary incontinence and social isolation, leading to a higher risk of self-neglect and death. Urinary incontinence can be prevented or alleviated by pelvic floor muscle training. China has not yet popularized such training. Using adult diapers can prevent embarrassing leaks, but many older Chinese are ashamed of the practice.

Sexual activities

Sexual activities are generally associated with better mental health, self-esteem, marital quality, and SWB.102 Older people experience the same. However, in certain countries like China and India, it is taboo for older people to express their sexual expectations and desires.103,104

Currently, very little scientific literature exists on sexuality in later life, especially in China.105 A Chinese females are usually reluctant to discuss sexual issues because of a long history of conservatism and a lack of sex education.106 In a study conducted in Central China, approximately one-third of older adults consider sex abnormal or unhealthy in later life.107 The percentage of older women who engaged in sexual activity in perimenopause and postmenopause, respectively, more than once a week was only 18.4% and 2.8%, respectively.104 It has been found in several studies that older Chinese have relatively low levels of sexual interest and types of sexual activity.102,104,106

The lack of partners and limited social activities also prevent most older people from having access to the sexual experiences they need. It is important for older adults and their families, as well as medical practitioners, to realize that many older people are still interested in sex and are sexually active. Health education should consider sexual conditions, and physicians should be instructed to ask their older patients about their sexual concerns.

Section 3. Determinants of health status of Chinese older people

Understanding health and functional status determinants are essential to prioritizing interventions in policymaking. In China, as elsewhere, health at older age result from the cumulative effects of behaviours and eventsthroughout their lifespan. These include exposure to parental decisions influencing in-utero and childhood health, health behaviours in adulthood (including smoking, drinking, and physical activity), and diet and nutritional status, many of which are heavily affected by socio-economic conditions. Less directly, the unobserved dimensions like socioeconomic position (SEP) may have additional influence on physical and emotional well-being, associated with the interaction within the family and community. Finally, environmental hazards are an unavoidable challenge for health. This section summarizes current evidence on these potential influences on the health status of older people in China.

3.1. In Utero and Childhood Health

Growing evidence suggests that ageing begins early in life, during which family and community environments play ireeplaceable roles. Childhood, and even as early as in utero circumstances, may be influential factors in hralthy ageing.108–110 Studies demonstrating the negative impacts of adverse early life circumstances and perturbations on well-being in old-age have exploited both retrospective information and the exposure to the severe nutritional events during China’s Great Famine.

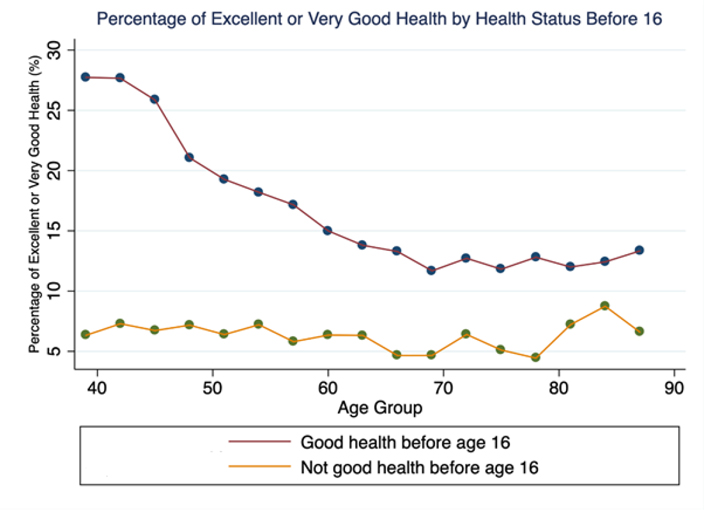

Back the data from the CHARLS survey, for example, respondents self-reported their child health status before age 16, while the comparsion with the current health status is shown in Figure 4. Childhood advantage in good health evidently persists over time, which that consistently higher than for those in poor childhood health and without improvement.

Figure 4: Self-rated Health among Middle-Aged and Older Adults by Child Health.

Source: CHARLS National Sample (2011, 2013, 2015)

Notes: In this figure, each respondent in the longitudinal survey is only counted once. In cases when a respondent participated in multiple waves of survey, information on the earliest wave of participation is used in plotting the figure.

Health outcomes may be impacted even more by adverse events during the first two trimesters of pregnancy. 108 For example, the Great Famine of 1959–61, to which most Chinese over 60-year-olds today were exposed at some point in their early lives, has been linked to several diseases in late life. The famine, coupled with a ‘rich’ nutrient environment later in life, may add to health risks in old age, especially for those with high incomes.109 Malnourished people may have developed a “thrifty genotype” to cope with adversity during the 1959–1961 famine. Undernutrition, however, was followed by rapid economic development since 1978, leading to nutritional abundance and a higher risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and CHD.110

In recent studies, comprehensive domains of risk factors have been assembled to understand how child factors may coalesce and show up in health disparities later in life. This will further promote the efficient allocation of resources in a way that mitigates health disparities. Research, for instance, has shown that in China, low educational attainment is among the most relevant risk for late-life frailty, followed by poor childhood health, poor neighbourhood quality, and low paternal education.111

3.2. Health Behaviours

With the population agieng in China, the health issues of older people have gained greater attention from all sectors. Considering the impact of unhealthy lifestyles on ageings’ health from multiple perspectives, including smoking, alcohol consumption, sedentary lifestyles, and diet, is essential to promoting “healthy ageing”.

3.2.1. Smoking

The harms of tobacco exposure are to nearly all organs of the body and all ages of society, and smoking is one of the leading causes of death for men in China. During the 2010s, it is estimated that smoking caused 20% of all adult male deaths in China,112 with 33.6% of male deaths attributable to smoking in 2019.113

Smoking prevalence has declined in China, as it has in many other countries, but the increase in the population has not resulted in a decrease in the total number of smokers.113,114 Between 1980 and 2012, the prevalence of daily tobacco consumption decreased by 8.1% (53.2% to 45.1%), while the number of smokers increased by about 100 million (182 million to 282 million).113,114 In the absence of widespread cessation, China’s tobacco-related deaths are projected to increase from about 1 million in 2010 to 2 million in 2030 and 3 million in 2050.113

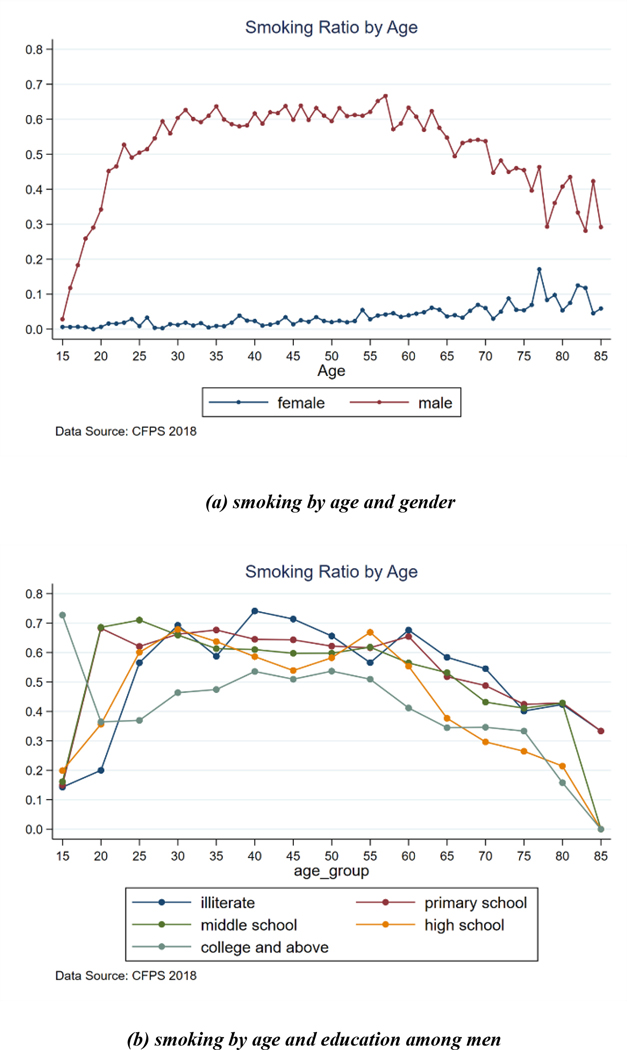

China has one of the highest smoking levels worldwide, especially among men. According to GBD 2019 Tobacco Collaborators, 49.7% of men and 3.5% of women older over age ten in China smoke, and the former is 17 percent higher than the global picture.113 According to the 2018 wave of Chinese Family Panel Studies (CFPS) data, smoking increases drastically at school-leaving ages115, while some cessation occurs after age 55. The difference in smoking for higher education obtained versus other education levels is significant (Figure 5), and the similar situation exists for older men in agricultural hukou versus non-agricultural hukou (49.6% vs. 39.5%), regarding the 2018 CHARLS survey data.

Figure 5: Prevalence of smoking among the Chinese population from CFPS 2018 data.

3.2.2. Alcohol consumption

Globally, alcohol use was the seventh leading risk factor for both deaths and DALYs in 2016, and studies have linked alcohol consumption to 60 acute and chronic diseases116 while dependent drinking can also lead to injury and potential self-harm or violence. In China, the drinking prevalence among men remains higher than in most other HICs,117 the share of drinkers engaging in harmful drinking behaviours increased over the past decade,118 but the prevalence of alcohol dependence has remained high over the past three decades which is similar to that found in western countries.119 Excessive alcohol consumption is associated with increased mortality from other diseases such as cancer, with liver cancer accounting for more than 60%.120 In China, 4.4% of all cancer deaths were attributable to alcohol consumption, with a male bias (6.7% in men, 0.4% in women).

Like smoking, alcohol consumption is primarily a male phenomenon in China, but women catch up quickly. In 1991, among those aged 15 and older, 35.1% of men drank while only 2.6% of women did under the definition of drinking wine, beer, baijiu or yellow rice wine more than 50 grams a month; in 2002, d for the same range of alcohol, the proportion drinking at least once a week rose to 39.6% (growth of 12.8%) and 4.5% (growth of 73%), respectively.120 In 2007, among those age capped at 69, 55.6% of men and 15.0% of women reported consuming any alcoholic beverage over the past 12 months with 62.7% and 51.0%,respectively, drinking excessively.121

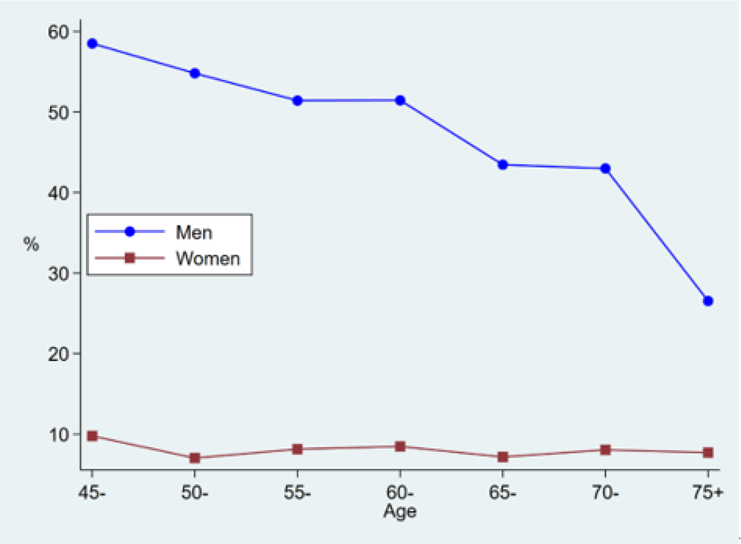

CHARLS provides reliable national estimates of drinking among older adults. As men age, their drinking declines sharply, while women drink much less in every cohort (Figure 6). In 2018, 41.3% of men and 7.8% of women aged 60 and older drank. For hukou, drinking prevalences were not significantly different, but education was positively related, with an increase from illiterate (36.2%) to high school and above (45.9%).

Figure 6: Prevalence of drinking among the middle-aged adults from CHARLS 2018 data.

3.2.3. Physical activity

National physical activity has declined with domestic economic development and urbanisation. The CHNS showed that, compared to 1991, average weekly physical activity among adults in China fell by 32% (in 2006).122 According to the CLHLS, Chinese oldest-old persons have become more sedentary and solitary in the past 2 decades. The odds ratio for television viewing among China’s oldest old increased by two to three times since 1998, and both recreational activities, including playing cards and Mah-Jongg, and exercise decreased.123

Over 80.3% of those 60 and older participated in mild physical activity, 42.4% in moderate and 23.0% in vigorous activity, according to the CHARLS survey. Vigorous activities were more popular among men (27.1% vs. 19.1%), and agricultural hukou holders had a higher participation rate than non-agricultural hukou holders (27.8% vs. 12.2%). Rural-urban differences in physical activity are mainly due to their different purposes. Among older Chinese men, participation in the labour force is higher than among women, and rural people work more than urban residents.124 Among those reporting physical activity, 45.0% of men reported activity related to work demands, but only 35.5% of women. In urban areas, 50.4% of people with agricultural hukou reported physical activity associated with their work, compared to 16.2% of people without agricultural hukou. Illiterates were more likely to engage in vigorous activities (24.5% vs. 17.8% in 2018) and to report that physical activities were required for labour work (47.0% vs. 23.4%).

3.2.4. Diet and nutrition

Food scarcity in China was conquered before the 1990s. As a result, it has evolved from a traditional diet high in carbohydrates to one high in fats, sugars, and sodium in packaged processed foods and beverages, and an increase in animal-based foods. Dietary diversity not only brought benefits but also led to an increase in diet-related diseases, such as chronic conditions and cancer. 125

China’s food consumption patterns vary greatly. According to China Kadoorie Biobank (CKB), the main cereal consumed every day was rice in southern China and wheat in northern China.126 Western regions consumed the most livestock meats and dairy products, eastern regions consumed the most poultry and eggs, and eastern and central regions consumed the most aquatic products.125 Regional diet patterns may explain regional health differences. Studies show regional dietary preferences can predict diabetes, hypertension, and body mass index.127

In China, nutritional excess and deficiencies coexist. The CHNS reported both dietary quality problems and dietary imbalances in the older population in 2009.128 Despite excessive intake of cereals, oils, and salt, respondents showed moderate to serious deficits in fish, vegetables, fruits, milk, and soybeans. There was no deficit in meat consumption.

Other studies have found that more than 30% of dietary energy was from fat,129 while inadequate intake of fruits, vegetables and protein was noted after 2010.125,130 A study in Singapore studied sarcopenia in 92 older adults and found that a regimen of physical exercise over six months was able to reduce the severity of respondents’ symptoms.131 Since sarcopenia is related to protein deficiencies, and the Singapore study suggests that protein deficiency is a potential major problem in the diets of Chinese older adults.

Undernutrition has also been documented among older Chinese, especially underweight, defined as BMI less than 18.5. In CHARLS data for respondents 60 and older, 7.7% were underweight, and 12.6% were undernourished. The prevalence of underweight was 47.1% in persons aged older than 80 years, and participants who were underweight suffered from the highest risk of CVD, non-CVD, and all-cause mortality.132

Chinese scholars have conducted intervention studies, which provide evidence for forming public health policies, including reducing salt intake. The results of a large-scale cluster randomised controlled trial conducted in 20,995 Chinese participants aged ≥60 years with hypertension showed that the prevalence of stroke, major cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in participants who used salt substitutes were lower than participants using ordinary salt.133

3.3. Social Environments

A substantial body of literature suggests that social networks, or the structure of social ties, are important social determinants of health and overall well-being.134 Further, the association between social networks on health in the older generation is particularly noteworthy because of the cumulative nature of exposure. Social networks operate through social support, social engagement, or social integration. While these terms are often used interchangeably, they have different meanings and are often associated with specific health outcomes.134 What’s more, it is important to note the implicit associations of social networks with observed and unobserved dimensions of socioeconomic well-being and vulnerability.

The discussion below emphasizes the positive relationship between social networks, social participation, and health status. Next, “empty nest” households are discussed, and the harm older people may suffer when they lack family in close proximity is highlighted. Finally, in a discussion of square dancing among older Chinese people, the benefits of physical activity are emphasized.

3.3.1. Social Networks and Social Support

People are surrounded by supportive others during their lifetime, and these constitute the social network and support, while the former has structural characteristics135 and the latter has functional characteristics. 136

Social networks and the support and social engagement derived from social relationships contribute to morbidity, mortality, and well-being. Coronary artery disease, all-cause mortality, cancer, and CVD mortality are independently predicted by social networks. In older adults, social relationships are associated with fewer depressive symptoms, better cognitive functioning, less functional disability, and better SWB.137

Over the past four decades, China’s social relationships have reflected both traditional values about family ties and support, as well as massive socioeconomic changes. Rural and urban areas have different social networks and participation. For instance, the massive out-migration and the heavy work associated with urban development have led to less social interaction and this change continues to occur.138

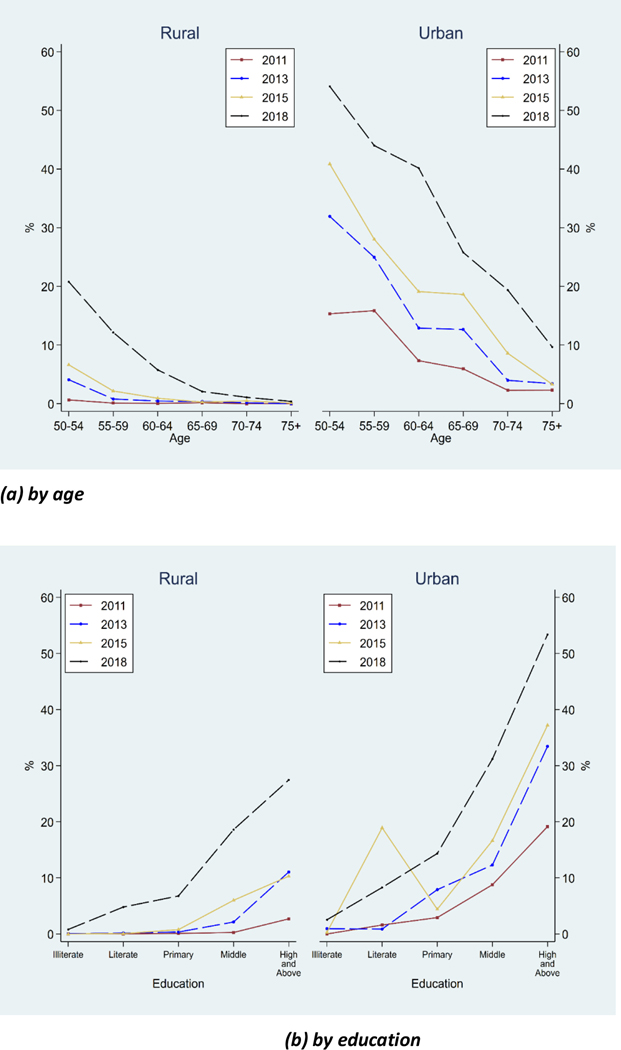

Technological developments, represented by the Internet, can connect people across distances and maintain or expand social ties. CHARLS data show that from 2011 to 2018, the number of people aged 50 and older using the Internet grew from 2.9% to 14.8%, while the distinct gaps in technology adoption between rural and urban areas and across age groups (Figure 7). For instance, the expansion of internet use is greater among urban residents and the more educated (Figure 7). In 2018, 31.9% of urban residents 50 and older used the internet, while the rate was 8.0% among rural residents. Older people are much less likely to adopt the internet. In 2018, only 3.5% of those 75 and older used the internet, while 28.6% of those 50–54 used the internet.

Figure 7: Prevalence of Internet use by education among the adults aged 50+ from CHARLS data.

Of particular interest is the association of certain group activities, such as playing cards and mahjong, with cognitive ability. Organized social activities may be mediated by physical exercise and cognitive ability, with different social activities having different mediating pathways.139 This study demonstrates the specificity of social network structure and function in health outcomes.

However, in other longitudinal studies, we have found that social support is not a strong predictor of maintaining cognitive ability, but rather that social engagement is a stronger predictor. This finding would suggest that participating in games that require older men and women to draw upon cognitive skills by the very nature of the activity and level of social engagement may promote healthy brain ageing in terms of cognition.

3.3.2. Demographic Transitions and Social Network Structure: The Case of Empty-Nest Older People in China

Families and households are integral parts of social networks. As life expectancy has improved significantly in many countries, fertility has decreased, and geographic mobility has increased, the empty nest situation has become more common. Besides economic changes, the one-child policy has also contributed to this situation in China. The number of older Chinese living in “empty nests” is estimated at 59% in 2011.140

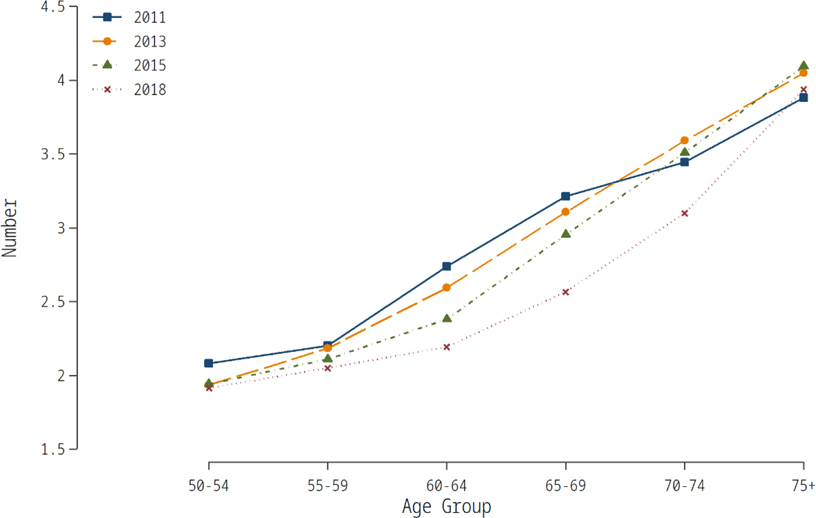

As a result, family support is important in China. Among older Chinese, family support is positively associated with psychological well-being and self-reported health, as reflected by higher life satisfaction and lower depression rates. Also, family support protects older adults from loneliness, whether they are empty nesters or not. Since most empty nesters have children nearby, family support is currently available, but that will change in the future.140 Figure 8 shows a dramatic decline in the number of children by cohorts. In 2018, those 75 years and older had 3.94 living children, but those aged 55–60 only had 2.05. With the out-migration of children, it will be difficult to expect children to live nearby. The stress of living in urban areas in China may make it hard for young migrants to provide support to their rural parents.

Figure 8: Number of living children among the adults aged 50+ from CHARLS data.

3.3.3. When Social Activity and Physical Activity are One: The Case of Square Dancing in China

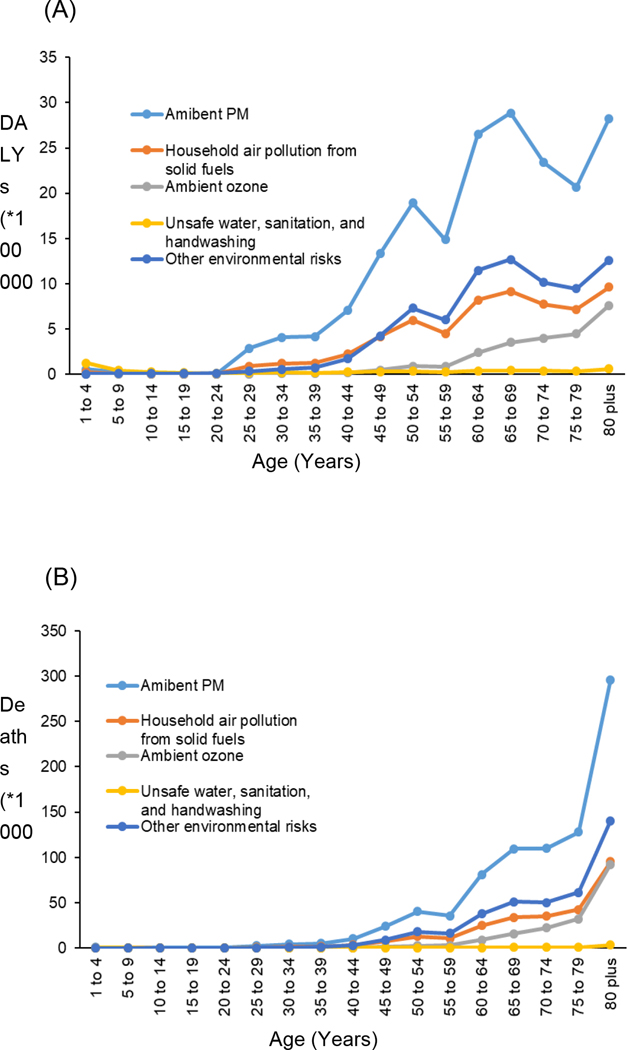

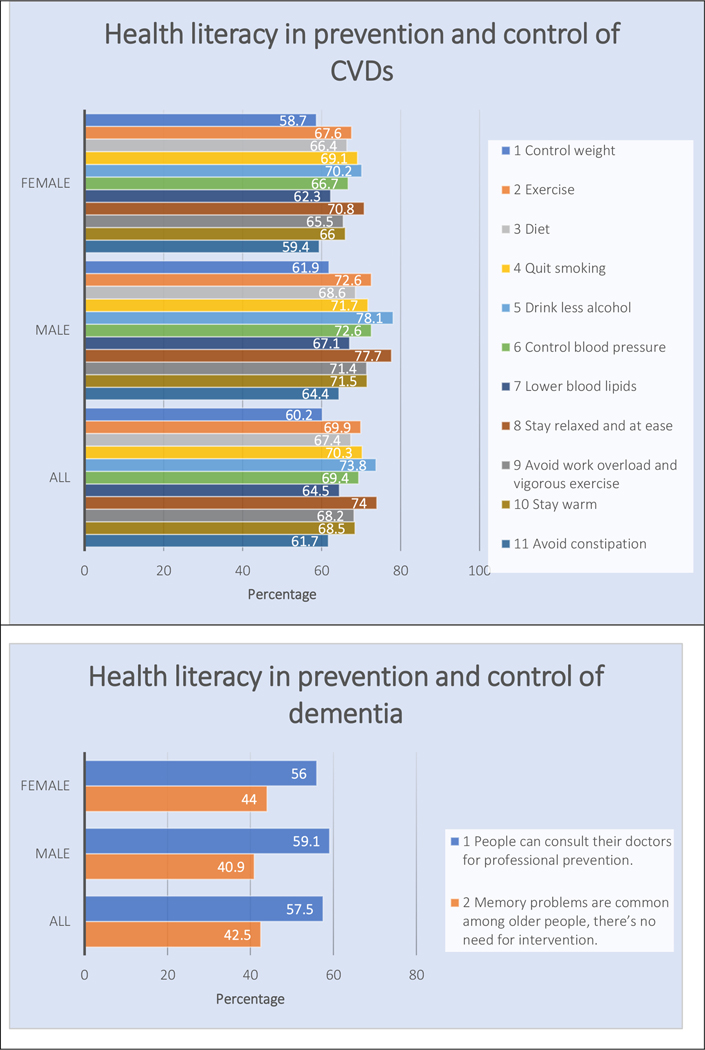

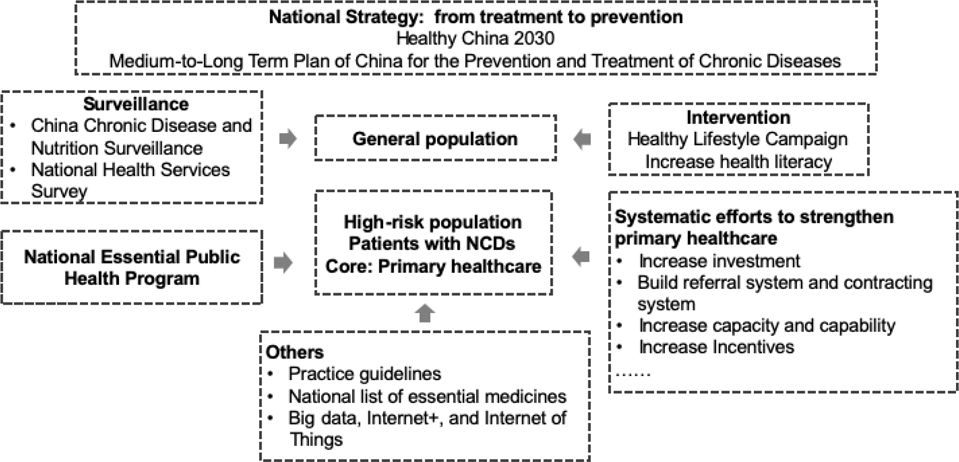

Disaggregating the social from the physical aspects that lead to health benefits is especially challenging in research, while Tai Chi and square dancing stand out as two typical examples in China of physical-social activities.Square dancing, a type of social activity for older Chinese in which people perform various dances in public areas, has grown in popularity in recent years. A recent study estimated that there are over 100 million people who participate in recreational square dancing in China.141 And square dancing is found to be positively associated with cognition and mental health among older Chinese.142