Abstract

Objective

The relationship between atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure with depressed ejection fraction (EF) is complex. AF-related tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy (TMC) can lead to worsening EF and clinical heart failure. We sought to determine whether a hybrid team ablation approach (HA) can be performed safely and restore normal sinus rhythm in patients with TMC and heart failure and to delineate the effect on heart failure.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed patients with nonparoxysmal (ie, persistent and long-standing persistent) AF-related TMC with depressed left ventricular EF (LVEF ≤40%) and heart failure (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class ≥2) who underwent HA between 2013 and 2018 and had at least 1 year of follow-up. Pre-HA and post-HA echocardiograms were compared for LVEF and left atrial (LA) size. Rhythm success was defined as <30 seconds in AF/atrial flutter/atrial tachycardia without class I or III antiarrhythmic drugs. Results are expressed as mean ± SD and 95% confidence interval (CI) of the mean.

Results

Forty patients met the criteria for inclusion in our analysis. The mean patient age was 67 ± 9.4 years. The majority of patients had long-standing persistent AF (26 of 40; 65%), and the remainder had persistent AF (14 of 40; 35%). All patients had NYHA class II or worse heart failure (NYHA class II, 36 of 40 [90%]; NYHA class III, 4 of 40 [10%]). The mean time in AF pre-HA was 5.6 ± 6.7 years. All patients received both HA stages. No deaths or strokes occurred within 30 days. Three new permanent pacemakers (7.5%) were placed. Rhythm success was achieved in >60% of patients during a mean 3.5 ± 1.9 years of follow-up. LVEF improved significantly by 12.0% ± 12.5% (95% CI, 7.85%-16.0%; P < .0001), and mean LA size decreased significantly by 0.40 cm ± 0.85 cm (95% CI, 0.69-0.12 cm; P < .01), with a mean of 3.0 ± 1.5 years between pre-HA and post-HA echocardiography. NYHA class improved significantly after HA (mean pre-HA NYHA class, 2.1 ± 0.3 [95% CI, 2.0-2.2]; mean post-HA NYHA class, 1.5 ± 0.6 [95% CI, 1.3-1.7]; P < .0001).

Conclusions

Thoracoscopic HA of AF in selected patients with TMC heart failure is safe and can result in rhythm success with structural heart changes, including improvements in LVEF and LA size.

Key Words: arrythmia surgery, hybrid ablation, tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy, heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction

Abbreviations and Acronyms: AAD, antiarrhythmic drug; AF, atrial fibrillation; AT, atrial tachycardia; AFL, atrial flutter; CA, catheter ablation; HA, hybrid ablation; LA, left atrium/atrial; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PV, pulmonary vein; TMC, tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy

Graphical abstract

Thoracoscopic and endocardial hybrid ablation (HA) of atrial fibrillation (AF) with depressed left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). HA in patients with tachycardia-mediated heart failure is safe and provides freedom from AF in the majority of patients. In our cohort, >60% of patients achieved rhythm success, with an average absolute LVEF improvement of 12% and an absolute left atrial size decrease of 0.4 cm, and no patient experienced stroke or death.

Video Abstract

Hybrid ablation of atrial fibrillation with depressed ejection fraction can lead to significant improvement in ejection fraction.

Central Message.

Selected patients with depressed left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and atrial fibrillation (AF) can respond to a hybrid team ablation approach with improved freedom from AF and LVEF and improved New York Heart Association classification.

Perspective.

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy often have depressed ejection fraction. Restoration of normal sinus rhythm in these patients is feasible via a hybrid ablation (HA) approach. Our single-center experience found significant improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction, left atrial size, and New York Heart Association classification after a minimally invasive, beating-heart HA approach.

The relationship between atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure continues to be defined. Our electrophysiology colleagues have demonstrated in randomized control studies that a rhythm control strategy with endocardial catheter ablation (CA) in selected patients with heart failure can improve clinical outcomes.1, 2, 3 Previous cardiac surgical studies also have highlighted the synergistic effect of surgical ablation for AF in patients with heart failure undergoing concomitant cardiac surgery.4 Damiano and colleagues5 recently published their results of Cox-Maze IV surgical ablation in patients with AF and tachycardia-induced heart failure and similarly found improved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification.

Hybrid ablation (HA), involving combined epicardial surgical ablation and endocardial CA, has been reported to provide promising early results in selected patients with AF6; however, its role in the heart failure population remains to be defined. The safety and effect of HA in the AF heart failure population have yet to be described. In the present study, we sought to determine whether HA can be performed safely in a cohort of patients with tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy (TMC) and heart failure, to explore whether HA can restore normal sinus rhythm, and to observe the effects of HA on heart failure.

Methods

Study Design and Patient Selection

This study was a retrospective review of patients with TMC and heart failure who underwent HA between 2013 and 2018. Study approval was granted by the Adventist Health–St Helena Institutional Review Board (January 21, 2020), in accordance with the requirements set forth in 45 CFR 46.110, Expedited Review Category 5. Owing to the retrospective nature of this review, the need for patient consent was waived.

Baseline patient demographic data and clinical outcomes were obtained from our institutional Society of Thoracic Surgeons database and our internal AF database. Patients were initially selected for evaluation in this study if they met the following criteria: (1) presence of persistent or long-standing persistent AF, (2) presence of LVEF ≤40% prior to HA, (3) presence of NYHA class ≥2 heart failure, and (4) completion of both stages of HA, as described previously.6 Patient charts were then reviewed to identify other sources of irreversible depressed ejection fraction as defined by Washington University's clinical algorithm,7 including but not limited to left ventricular fibrosis, amyloidosis, alcohol-mediated cardiomyopathy, and viral cardiomyopathy. Patients with “depressed” LVEF (defined as ≤40%) were further characterized as TMC or TMC with ischemia (TCM-I), with the latter defined by the presence of (1) a history of coronary artery disease necessitating intervention by percutaneous coronary intervention or surgery, (2) reversible ischemic defect on a stress test, or (3) coronary artery obstruction detected on angiography.

Thoracoscopic HA Procedure

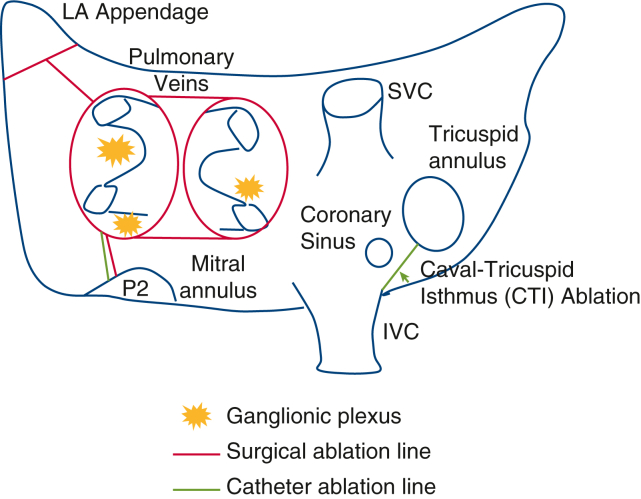

During the surgical epicardial stage, 4 thoracoscopic ports were typically used bilaterally to perform the procedure. Radiofrequency energy ablation was used to create a lesion set that included bilateral pulmonary vein (PV) isolation, interconnecting lesions between superior and inferior PVs, respectively, a line from the base of the left atrial (LA) appendage to the left superior PV, and a partial mitral isthmus line extending from the left inferior PV onto the coronary sinus (Figure E1). All patients had the ligament of Marshall divided and the LA appendage excluded and electrically isolated with an epicardial clip (AtriClip; AtriCure).8, 9, 10, 11 During endocardial CA, assessment of surgical integrity consisted of confirmation of PV isolation, posterior box isolation, and complete mitral and tricuspid isthmus block. All necessary touch-up ablations were performed using radiofrequency energy. Ablations to complete the mitral isthmus line were performed with 45W to 50W energy at the mitral annulus, 35W at the posterior wall, and 25W from within the coronary sinus.

Figure E1.

Diagram of hybrid ablation. Red lines represent lesions created during first-stage epicardial ablation (bilateral pulmonary vein [PV] isolation, interconnecting lines [roof and floor]—left atrial [LA] “box,” LA appendage to left superior PV [coumadin ridge], and mitral isthmus). Green lines represent lesions created during the second-stage endocardial ablation (completion of the mitral isthmus, cava-tricuspid isthmus, and any additional ablation needed to complete the posterior wall and PV isolation). Ganglionic plexi are also ablated during the epicardial ablation. LA, Left atrial; SVC, superior vena cava; IVC, inferior vena cava.

Rhythm Success and LVEF and Left Atrial Size Changes

The effectiveness of HA was determined by standard monitoring techniques (electrocardiography, continuous ambulatory monitoring, implantable loop recording, 7- to 14-day ZioPatch, or pacemaker interrogation) with at least 1 year of follow-up. Rhythm success was defined by the Heart Rhythm Society criteria of <30 seconds of AF/atrial flutter (AFL)/atrial tachycardia (AT) and off class I and III antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs).12 Any additional direct-current cardioversions or CAs were described as well. Pre-HA and post-HA echocardiograms were compared to determine the effect of HA on LVEF and LA size. For post-HA assessment, we used the echocardiogram that correlated with the latest rhythm monitoring follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis and creation of figures were performed using Prism 9.2.0 (GraphPad Software). Statistical significance for nonparametric variables was determined using the Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank test with P < .05. All results are reported as mean ± SD with 95% confidence interval (CI) of the mean unless noted otherwise. Kaplan–Meier estimates were censored for AF recurrence.

Multivariable logistic regression and simple logistic regression analyses were performed with the dependent outcome variable of 1-year rhythm success and predictor variables including age at the procedure, sex, body mass index, previous CA, NYHA class, time in AF, AF type (ie, persistent, long-standing persistent), pre-HA LVEF, pre-HA LA size, and duration of epicardial surgery.

Results

Baseline Patient Characteristics

Forty patients met the analysis criteria, of whom 87.5% (35 of 40) were male and 65% (26 of 40) had long-standing persistent AF (Table 1). The mean time in AF prior to HA was 5.6 ± 6.7 years. The mean LVEF was 34.5 ± 5.9% (95% CI, 32.7%-36.4%), and mean LA size was 5.3 ± 0.8 cm (95% CI, 4.9-5.5 cm). Prior to ablation, 90% of the patients (36 of 40) were in NYHA class II, and 87.5% (35 of 40) were on oral anticoagulation therapy. Fifteen percent of the patients (6 of 40) had a history of transient ischemic attack or stroke. Pre-HA TMC and TMC-I were observed in 31 and 9 patients, respectively (Figure E2).

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographic data (N = 40)

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 66.7 ± 9.4 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 31.2 ± 6.6 |

| Sex, males:females, n | 35:5 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 31 (78) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 6 (15) |

| VHD, n (%) | 12 (30) |

| NYHA classification, n (%) | |

| Class II | 36 (90) |

| Class III | 4 (10) |

| LVEF, %, mean ± SD | 34.5 ± 5.9 |

| Left atrial size, cm, mean ± SD | 5.3 ± .8 |

| AF type, n (%) | |

| Persistent | 14 (35) |

| Longstanding persistent | 26 (65) |

| Time in AF, y, mean ± SD | 5.6 ± 6.7 |

| History, n (%) | |

| Cardioversion | 24 (60) |

| Catheter ablation | 6 (15) |

| Pacemaker | 6 (15) |

| Heart surgery | 4 (10) |

| Oral anticoagulation | 35 (88) |

| TIA/stroke | 6 (15) |

| Bleeding | 4 (10) |

SD, Standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; VHD, valvular heart disease (moderate mitral or tricuspid regurgitation); NYHA, New York Heart Association; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; AF, atrial fibrillation; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Figure E2.

Rhythm results with hybrid ablation in patients with tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy (TMC) and TMC-ischemia (TMC-I): <30 seconds of atrial fibrillation (AF)/atrial flutter (AFL)/atrial tachycardia (AT) (dark green), electrocardiography (ECG) in normal sinus rhythm (NSR) off antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs; light green), 0% AF burden but >30 seconds AT (blue), ECG in NSR with AAD (orange), paroxysmal AF (black and white pattern), continuous AF/AFL/AT (black), and reintervention with direct-current cardioversion (DCCV) or catheter ablation (CA; asterisks). Red boxes show patient numbers. CAM, continous ambulatory monitor; AF, atrial fibrillation; AFL, atrial flutter; AT, atrial tachycardia; AAD, antiarrhythmic drugs; EKG, electrocardiogram; NSR, normal sinus rhythm; DCCV, Direct-current cardioversion; CA, catheter ablation; TMC, tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

HA Procedural Outcomes and Safety

The average time between the first-stage epicardial ablation and second-stage endocardial ablation was 58.7 ± 45.3 days. At the time of the second-stage endocardial ablation, endocardial mapping revealed bilateral PV isolation in 87.5% of patients (35 of 40) and LA posterior wall isolation in 65% (26 of 40) (Table 2). After the second-stage endocardial CA, bilateral PVs were isolated in 100% of the patients (40 of 40), LA posterior wall isolation was observed in 95% (38 of 40), the mitral isthmus was isolated in 95% (38 of 40), and the cavo-tricuspid isthmus was isolated in all patients. Three patients (7.5%) required a permanent pacemaker implantation because of sick sinus syndrome. At 30 days postablation, no deaths or strokes had occurred. One patient experienced right phrenic nerve palsy between the epicardial and endocardial stage.

Table 2.

Procedural outcomes

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Epicardial surgical time, h, mean ± SD | 2.3 ± .6 |

| Hospital length of stay following surgery, d, mean ± SD | 3.03 ± 1.10 |

| Endocardial catheter time, h, mean ± SD | 2.1 ± 1.0 |

| Time between first and second stages, d, mean ± SD | 58.7 ± 45.3 |

| Patients with complete PVI after first stage, n (%) | 35 (88) |

| Patients with complete PVI after second stage, n (%) | 40 (100) |

| Patients with complete left atrial “box” after first stage, n (%) | 26 (65) |

| Patients with complete left atrial “box” after second stage, n (%) | 38 (95) |

| Pacemaker implantation, n (%) | 3 (8) |

| Off oral anticoagulation at last follow-up, n (%) | 23 (68)∗ |

| Off AADs at last follow-up, n (%) | 28 (82)∗ |

| Deaths within 30 d, n | 0 |

| TIA/stroke within 30 d, n | 0 |

| Phrenic nerve palsy, n (%) | 1 (3) |

| Post-HA echocardiography findings, mean ± SD | |

| Time between pre-HA and post-HA echocardiography, y | 3.0 ± 1.5 |

| Time between HA and post-HA echocardiography, y | 2.8 ± 1.5 |

| LVEF, % | 46.5 ± 12.8 |

| Left atrial size, cm | 4.8 ± 1.0 |

| Rhythm success (<30 s AF/AFL/AT; off AAD) | |

| Time between pre-HA and post-HA rhythm monitoring, y, mean ± SD | 3.5 ± 1.9 |

| At 1 y, n (%) | 26 (65)† |

| At 2 y, n (%) | 25 (71)‡ |

| At 3 y, n (%) | 15 (63)§ |

SD, Standard deviation; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; AADs, antiarrhythmic drugs; TIA, transient ischemic attack; HA, hybrid ablation; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; AF, atrial fibrillation; AFL, atrial flutter; AT, atrial tachycardia.

Out of 34 patients.

Out of 40 patients.

Out of 35 patients.

Out of 24 patients.

HA Rhythm Outcomes

The mean duration of follow-up for rhythm assessment was 3.5 ± 1.9 years. Rhythm success was achieved in 65% of the patients (26 of 40) at 1 year, in 71.4% (25 of 35) at 2 years, and in 62.5% (15 of 24) at 3 years (Figure 1 and Video Abstract). Freedom from AF, as detected by >24 hours of continuous ambulatory monitoring or electrocardiography with or without the use of AADs or additional interventions, was 85% (34 of 40) at 1 year, 88.6% (31 of 35) at 2 years, and 87.5% (21 of 24) at 3 years. At last follow-up, 67.6% of patients (23 of 34) were off oral anticoagulation, and 82.3% (28 of 34) were off AADs. Kaplan–Meier freedom from AF recurrence (defined as <30 seconds of AF/AFL/AT) for the entire follow-up period is presented in Figure 2. Oral anticoagulation and AAD use were deferred to the referring physician.

Figure 1.

Rhythm results with hybrid ablation in patients with heart failure at 1-, 2-, and 3-year follow-ups: <30 seconds of atrial fibrillation (AF)/atrial flutter (AFL)/atrial tachycardia (AT) (dark green), electrocardiography (ECG) in normal sinus rhythm (NSR) off antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) (light green), 0% AF burden but >30 seconds of AT (blue), ECG in NSR with AAD (orange), paroxysmal AF (black and white pattern), continuous AF/AFL/AT (black), and reintervention with direct-current cardioversion (DCCV) or catheter ablation (CA) (white). DCCV, Direct-current cardioversion; CA, catheter ablation; AF, atrial fibrillation; AFL, atrial flutter; AT, atrial tachycardia; NSR, normal sinus rhythm; AAD, antiarrhythmic drugs; EKG, electrocardiogram; CAM, continuous ambulatory monitor.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier freedom from atrial fibrillation (AF) recurrence (red) with 95% confidence intervals. Freedom from AF recurrence is defined as <30 seconds of AF, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia. AF, Atrial fibrillation.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis found no significant predictors of rhythm success at 1 year. Simple logistic regression analysis similarly demonstrated no significant predictors of rhythm. However, time in AF ≥8 years and LA diameter ≥8 cm individually trended toward having an effect on rhythm success (Figure E3).

Figure E3.

Simple logistic regression analysis of time in atrial fibrillation (AF) (A) and left atrial (LA) size (B) to predict rhythm success at 1 year. AF, Atrial fibrillation; AFIB, atrial fibrillation; LA, left atrial.

LVEF

The mean time between pre-HA echocardiography and latest follow-up echocardiogram with rhythm monitoring was 3.0 ± 1.5 years. When all patients were considered, there was a mean 12.0% increase in LVEF (pre-HA, 34.5 ± 5.9% vs post-HA, 46.5 ± 12.8%; 95% CI, 7.95%-16.0%; P < .001) (Figure 3). Fourteen patients (35%) experienced full LVEF recovery to ≥55%. When binned by follow-up time, mean LVEF improvements were 8.4% at <2 years of follow-up, 16.4% at 2 to 3 years, and 13.7% at >3 years. Independent comparisons of TMC and TMC-I LVEF changes revealed improvements across both populations (Figure E4).

Figure 3.

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in patients with tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy (TMC) and heart failure pre- and post-hybrid ablation (HA) of atrial fibrillation (AF). EF, Ejection fraction.

Figure E4.

Structural heart changes of hybrid ablation in patients with tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy (TMC) and TMC with ischemia (TMC-I). LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction; LA, left atrial; TMC, tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy.

Four patients did not experience any increase in LVEF despite significant improvement in freedom from AF. Two of these patients had what appears to be end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy, and the other 2 patients had significant coronary artery disease that was not detected on their initial ischemia evaluation. Five patients experienced improved LVEF without strict rhythm control success. Two of these patients experienced significant AF burden reduction, which may have contributed to LVEF improvement. One patient had a device upgrade to a cardiac resynchronization therapy device post-HA. One patient experienced improved rate control with an AAD post-HA (Figure E2).

LA Diameter and NYHA Classification

When all patients were analyzed together, a mean 0.4-cm decrease in LA size was observed (pre-HA: 5.25 ± .084 cm [95% CI, 4.93-5.51 cm]; post-HA: 4.82 ± 1.01 cm, [95% CI, 4.48-5.16 cm]; difference, 0.40 ± 0.85 cm [95% CI, 0.69-0.12 cm]; P = .0078) (Figure 4). An independent comparison of TMC and TMC-I LA size effects revealed improvement across the TMC population, but not the TMC-I population (Figure E4). Following HA, the overall distribution of NYHA classification was improved significantly (pre-HA: 2.10 ± 0.3 [95% CI, 2.0-2.20]; post-HA: 1.45 ± 0.64 [95% CI, 1.25-1.65]; difference, 0.65 ± 0.62 [95% CI, 0.85-0.45]; P < .0001) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Left atrial (LA) size (cm) in patients with tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy and heart failure pre- and post-hybrid ablation of atrial fibrillation. LA, Left atrial.

Figure 5.

New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification improvement after hybrid ablation (HA). NYHA, New York Heart Association; HA, hybrid ablation.

Discussion

TCM due to uncontrolled AF can lead to reduced LVEF and clinical heart failure but has been shown to respond positively to a rhythm control strategy, whether by endocardial CA1, 2, 3,13 or open surgical Cox-Maze IV.4,5 According to the most recent Society of Thoracic Surgeons data for stand-alone AF, the use of off-pump surgical ablation procedures continues to increase compared with the gold standard on-pump Cox-Maze IV surgery.14

The specific role of an HA approach in patients with heart failure has not been described previously. In our single-center heart failure cohort, patients experienced an average 12.0% improvement in LVEF and a 0.4-cm decrease in LA size, and no patient experienced stroke or death with a HA approach. We have demonstrated that in patients with depressed LVEF fraction, an AF heart team HA approach with combined thoracoscopic epicardial and endocardial ablation can provide significant recovery of left ventricular function, improved freedom from AF, and an acceptable risk profile without the need for sternotomy, thoracotomy, or cardiopulmonary bypass.

Damiano and colleagues at Washington University5 published the benchmark study for the effect of the Cox-Maze IV surgery in patients with stand-alone AF and tachycardia-mediated heart failure. They reported a 12-month freedom from AF off AADs of 89%, improvement in LVEF from 32% at baseline to 55%, and significant improvement in NYHA classification with an average follow-up of 22 months. Other studies have shown improvement in LVEF of 3% to 11% in patients following HA using a subxiphoid or transdiaphragmatic approach.15, 16, 17, 18 In our HA cohort, 65% of the patients had 12-month freedom from AF off AADs, and mean TCM LVEF improved from 35% to 47% with an average follow-up of nearly 3 years. We also observed a significant improvement in NYHA classification; however, notably, our cohort had less severe NYHA heart failure at baseline compared with the cohort at Washington University. Interestingly, we also found that patients with >2 years of follow-up had greater improvement in LVEF compared with those with <2 years of follow-up (<2 years, 8.4% improvement; 2-3 years, 16.4% improvement; >3 years, 13.7% improvement). This may suggest that prolonged freedom from AF beyond 2 years may lead to further gains in LVEF, but that ultimately the ceiling of recovery might not increase beyond 3 years.

In addition to LVEF improvement, we observed a modest yet significant decrease in mean LA size by 0.4 cm. We speculate that the mechanism for this decrease in LA size may involve increased atrial contractility from atrial synchrony rather than atrial remodeling at the structural-cellular level, although neither mechanism was evaluated directly. It is well known that increased LA size is a predictor of rhythm failure after surgical ablation.19

Ad and colleagues20 previously demonstrated that in patients with a LA size >5.5 cm, the success rate of surgical ablation with Cox-Maze IV in the concomitant setting (Cox-Maze with CABG, AVR or MVR) is significantly lower but still approaches 80%.20 We identified a similar, although not statistically significant, trend via simple logistic regression analysis of 1-year rhythm success and LA size (Figure E3). It appears that even with LA size approaching 8 cm, the probability of achieving rhythm success exceeds that of not achieving rhythm success and should be considered in patient selection. Similarly, our cohort analysis suggests that time in AF, although a known predictor of rhythm failure,21 might not eliminate the possibility of improving rhythm control. Even with an average time in AF of >5 years pre-HA, we were still able to achieve a significant reduction of AF burden in >80% of our cohort. Again, simple logistic regression, although not statistically significant, showed that patients with up to 8 years of AF prior to HA still have a reasonable opportunity of achieving rhythm control (Figure E3).

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that our HA approach does not replicate the Cox-Maze IV lesion set. The present study's thoracoscopic HA approach leaves absent 4 lesions from the Cox-Maze IV: the coronary sinus lesion, superior vena cava–inferior vena cava intercaval line, the intracaval line to the tricuspid annulus (although a cavo-tricuspid isthmus line is created at the time of endocardial CA), and the lesion to the tip of the right atrial appendage. Here we have reported our experience with a bilateral thoracoscopic approach6; however, other centers22,23 may provide versions of a HA that are procedurally different and have different lesion sets than that of the recent CONVERGE trial.22, 23, 24 The HA approach for managing patients with heart failure described in the present analysis is positioned between isolated endocardial ablation and a complete Cox-Maze IV procedure. Defining which patients may be best suited to respond to this approach warrants further investigation.

In addition, the role of the totally thoracoscopic single-stage procedure also requires evaluation, as selected patients might not require the second endocardial stage.25 The single-stage approach without a compulsory second endocardial stage provides the advantage of omitting undue risk of a second procedure if the patient remains in normal sinus rhythm. Nonetheless, we support a 2-stage approach for 2 specific reasons: (1) endocardial mapping at the second stage provides critical feedback regarding the transmurality of epicardial lesions and thus the opportunity for iterative improvements in the epicardial technique while also fostering important dialog within the AF heart team, and (2) the endocardial stage allows for an ablation lesion set that more closely approaches the Cox-Maze IV lesion, and we are hopeful that this will confer a more durable freedom from AF.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include its retrospective study cohort with a sample size of only 40 patients. Our small sample size limited our ability to model predictors of rhythm success and to claim generalizability of our findings, and is fraught with confounders that we were not able to control for in our analysis. An inherent selection bias might have biased our results toward more favorable outcomes. A comparison of the effectiveness of an isolated single-stage thoracoscopic approach and a 2-stage epicardial-endocardial hybrid approach was not possible, because all patients underwent both stages of the HA. Finally, our study is limited in its follow-up. Although we went to great lengths to ensure maximal follow-up, we provide care in a rural setting in northern California and most of our patients travel >50 miles to receive care, which poses challenges for follow-up. We acknowledge that over time, rhythm control in most series evaluating freedom from AF deteriorates, and we would expect to find the same trend in this patient cohort if we were able to capture improved follow-up.

Conclusions

HA in patients with tachycardia-mediated heart failure is safe and provides freedom from AF in the majority of cases. In our cohort, >60% of patients achieved rhythm success, with an average absolute mean LVEF improvement of 12% and absolute mean LA size decrease of 0.4 cm, and no patient experienced stroke or death.

Conflict of Interest Statement

A.K., G.D., and S.E. serve on a speakers' bureau for AtriCure. All other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The Journal policy requires editors and reviewers to disclose conflicts of interest and to decline handling or reviewing manuscripts for which they may have a conflict of interest. The editors and reviewers of this article have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support was provided by Latoya M. Mitchell, PhD, CMPP of AtriCure, under the direction of the authors.

Appendix E1

Figure E5.

Patient Flow Diagram. LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction; ECHO, echocardiogram; F/u, follow up; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Supplementary Data

Tachycardia mediated cardiomyopathy with depressed ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation is responsive to surgical ablation. Using a hybrid ablation with staged epicardial and endocardial approaches can lead to improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction and heart failure classification while avoiding traditional open sternotomy, on-pump cardiac surgery.Video available at: https://www.jtcvs.org/article/S2666-2736(22)00352-7/fulltext.

References

- 1.Prabhu S., Taylor A.J., Costello B.T., Kaye D.M., McLellan A.J., Voskoboinik A., et al. Catheter ablation versus medical rate control in atrial fibrillation and systolic dysfunction: the CAMERA-MRI study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1949–1961. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marrouche N.F., Brachmann J., Andresen D., Siebels J., Boersma L., Jordaens L., et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:417–427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Biase L., Mohanty P., Mohanty S., Santangeli P., Trivedi C., Lakkireddy D., et al. Ablation versus amiodarone for treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with congestive heart failure and an implanted device: results from the AATAC multicenter randomized trial. Circulation. 2016;133:1637–1644. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pecha S., Ahmadzade T., Schäfer T., Subbotina I., Steven D., Willems S., et al. Safety and feasibility of concomitant surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with severely reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46:67–71. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adademir T., Khiabani A.J., Schill M.R., Sinn L.A., Schuessler R.B., Moon M.R., et al. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;108:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.01.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunnington G.H., Pierce C.L., Eisenberg S., Bing L.L., Chang-Sing P., Kaiser D.W., et al. A heart-team hybrid approach for atrial fibrillation: a single-centre long-term clinical outcome cohort study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;60:1343–1350. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezab197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khiabani A.J., Schuessler R.B., Damiano R.J., Jr. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;162:1100–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.05.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamohara K., Fukamachi K., Ootaki Y., Akiyama M., Zahr F., Kopcak M.W., Jr., et al. A novel device for left atrial appendage exclusion. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:1639–1644. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamohara K., Fukamachi K., Ootaki Y., Akiyama M., Cingoz F., Ootaki C., et al. Evaluation of a novel device for left atrial appendage exclusion: the second-generation atrial exclusion device. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benussi S., Mazzone P., Maccabelli G., Vergara P., Grimaldi A., Pozzoli A., et al. Thoracoscopic appendage exclusion with an AtriClip device as a solo treatment for focal atrial tachycardia. Circulation. 2011;123:1575–1578. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.005652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Starck C.T., Steffel J., Emmert M.Y., Plass A., Mahapatra S., Falk V., et al. Epicardial left atrial appendage clip occlusion also provides the electrical isolation of the left atrial appendage. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;15:416–418. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivs136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calkins H., Hindricks G., Cappato R., Kim Y.H., Saad E.B., Aguinaga L., et al. 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:e275–e444. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sohns C., Zintl K., Zhao Y., Dagher L., Andresen D., Siebels J., et al. Impact of left ventricular function and heart failure symptoms on outcomes post ablation of atrial fibrillation in heart failure: CASTLE-AF trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020;13:e008461. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.120.008461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ad N., Holmes S.D., Roberts H.G., Jr., Rankin J.S., Badhwar V. Surgical treatment for stand-alone atrial fibrillation in North America. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;109:745–752. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geršak B., Zembala M.O., Müller D., Folliguet T., Jan M., Kowalski O., et al. European experience of the convergent atrial fibrillation procedure: multicenter outcomes in consecutive patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:1411–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toplisek J., Pernat A., Ruzic N., Robic B., Sinkovec M., Cvijic M., et al. Improvement of atrial and ventricular remodeling with low atrial fibrillation burden after hybrid ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2016;39:216–224. doi: 10.1111/pace.12791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zembala M., Filipiak K., Kowalski O., Buchta P., Niklewski T., Nadziakiewicz P., et al. Staged hybrid ablation for persistent and longstanding persistent atrial fibrillation effectively restores sinus rhythm in long-term observation. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:109–117. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.53960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oza S.R., Crossen K.J., Magnano A.R., Merchant F.M., Joseph L., De Lurgio D.B. Emerging evidence of improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction after convergent ablation in persistent and longstanding persistent AF patients with reduced ejection fraction. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17:S366. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scherer M., Therapidis P., Miskovic A., Moritz A. Left atrial size reduction improves the sinus rhythm conversion rate after radiofrequency ablation for continuous atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing concomitant cardiac surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;54:34–38. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-865873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ad N., Henry L., Hunt S., Holmes S.D. Should surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation be performed in patients with a significantly enlarged left atrium? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ad N., Holmes S.D., Shuman D.J., Pritchard G. Impact of atrial fibrillation duration on the success of first-time concomitant Cox maze procedures. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:1613–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.04.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maesen B., Pison L., Vroomen M., Luermans J.G., Vernooy K., Maessen J.G., et al. Three-year follow-up of hybrid ablation for atrial fibrillation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;53(suppl_1):i26–i32. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezy117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vos L.M., Bentala M., Geuzebroek G.S., Molhoek S.G., van Putte B.P. Long-term outcome after totally thoracoscopic ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020;31:40–45. doi: 10.1111/jce.14267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeLurgio D.B., Crossen K.J., Gill J., Blauth C., Oza S.R., Magnano A.R., et al. Hybrid convergent procedure for the treatment of persistent and long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation: results of CONVERGE clinical trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020;13:e009288. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.120.009288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee R., McCarthy P.M., Passman R.S., Kruse J., Malairsrie S.C., McGee E.C., et al. Surgical treatment for isolated atrial fibrillation: minimally invasive vs. classic cut and sew maze. Innovations (Phila) 2011;6:373–377. doi: 10.1097/IMI.0b013e318248f3f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tachycardia mediated cardiomyopathy with depressed ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation is responsive to surgical ablation. Using a hybrid ablation with staged epicardial and endocardial approaches can lead to improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction and heart failure classification while avoiding traditional open sternotomy, on-pump cardiac surgery.Video available at: https://www.jtcvs.org/article/S2666-2736(22)00352-7/fulltext.