Abstract

Objectives:

The purpose of the study was to describe unique care needs of people with dementia (PWD) and their caregivers during transitions from skilled nursing facilities (SNF) to home.

Design:

A qualitative study using focus groups, semi-structured interviews, and descriptive qualitative analysis.

Setting and Participants:

The study was set in one state, in 4 SNFs where staff had experience using a standardized transitional care protocol. The sample included 22 SNF staff, 4 home health nurses, 10 older adults with dementia, and their 10 family caregivers, of whom 39 participated in focus groups and/or interviews.

Methods:

Data collection included 4 focus groups with SNF staff and semi-structured interviews with home health nurses, SNF staff, PWD, and their family caregivers. Standardized focus group and interview guides were used to elicit participant perceptions of transitional care. We used the framework analytic approach to qualitative analysis. A steering committee participated in interpretation of findings.

Results:

Participants described four unique care needs: (1) PWD and caregivers may not be ready to fully engage in dementia care planning while in the SNF, (2) caregivers are not prepared to manage dementia symptoms at home, (3) SNF staff have difficulty connecting PWD and caregivers to community supports, and (4) caregivers receive little support to address their own needs.

Conclusions and Implications:

Based on findings, recommendations are offered for adapting transitional care to address the needs of PWD and their caregivers. Further research is needed (1) to confirm these findings in larger, more diverse samples and (2) to adapt and test interventions to support successful community discharge of PWD and their caregivers.

Keywords: Dementia, Caregivers, Transitional care, Skilled nursing facilities, Qualitative research

Brief summary

Transitional care of people with dementia (PWD) and their caregivers must address four unique care needs: (1) PWD and caregivers may not be ready to fully engage in dementia care planning while in the SNF, (2) caregivers are not prepared to manage dementia symptoms at home, (3) SNF staff have difficulty connecting PWD and caregivers to community supports, and (4) caregivers receive little support to address their own needs.

Background

Annually in the U.S., 1.5 million older adults transfer from hospitals to skilled nursing facilities (SNF) for rehabilitation prior to returning home.1 One in three SNF patients have a dementia diagnosis. Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias are underdiagnosed in routine practice, so SNFs also serve others who lack this formal diagnosis but have persistent problems with memory and thinking that interfere with function.2, 3 The transition from SNF to home is challenging for people with dementia (PWD), who are at risk for poor nutrition, hydration, pain control, and new health problems (e.g., respiratory infections) resulting in re-hospitalizations.4, 5 Furthermore, their family caregivers often lack resources and training to manage challenges at home.6 Developing transitional care matched to needs of this population is essential to improving outcomes.

Transitional care is a set of time-limited services designed to support coordination and continuity of care during transfers between providers and settings of care.7, 8 Studies demonstrate the effectiveness of transitional care at improving outcomes after transitions from hospital to home;9, 10 some evidence suggests effectiveness in SNFs.11, 12 While few studies describe transitional care in dementia,5 available evidence suggests gaps in (1) expertise in dementia,5, 13 (2) recognition of how transitions fit in dementia health trajectories,14 (3) preparation of caregivers,5, 13, 14 and (4) communication between providers.5, 13, 15, 16 In quasi-experimental studies, hospital-based transitional care for PWD, compared to usual care, was associated with fewer hospital readmissions and decreased caregiver burden.17–19 Prior studies have not examined the high risk transitions of PWD from SNF to home; thus, this qualitative study described stakeholder perspectives on the care needs of PWD and their caregivers during transitions from SNFs to home.

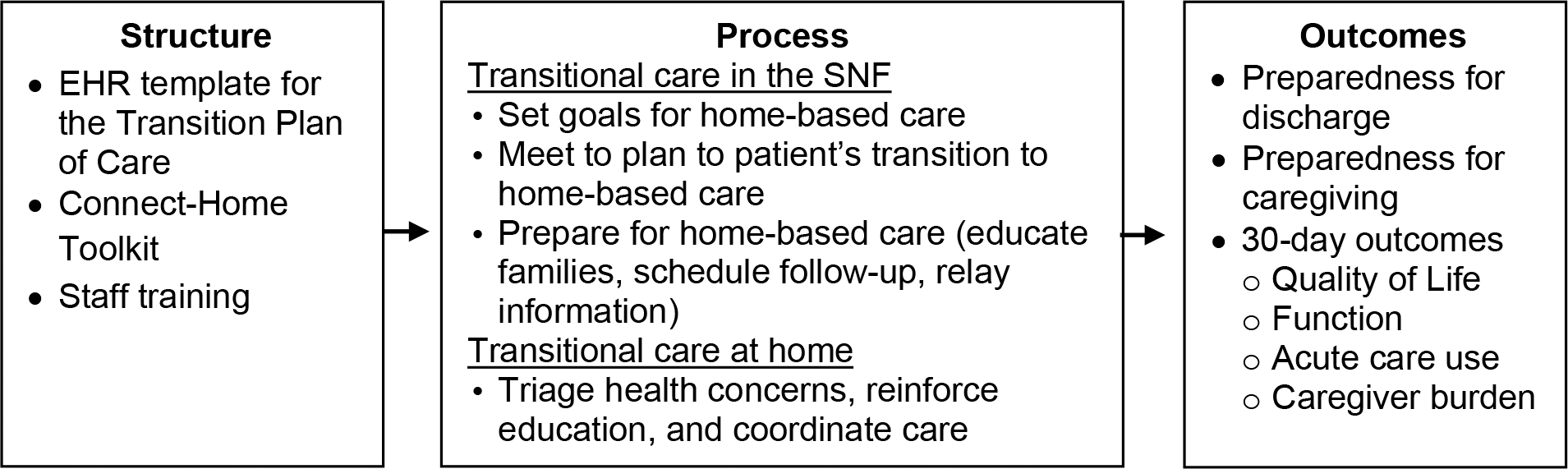

Conceptual Framework: Connect-Home Transitional Care

This study was guided by the conceptual framework underlying the Connect-Home intervention protocol.20, 21 Extensive formative work with SNF staff, patients, and caregivers informed the Connect-Home framework.12, 22, 23 As summarized in Figure 1, the framework posits that transitional care requires structures (e.g., staff training and tools in the electronic health record) to support the time-limited processes designed to address care needs at home (e.g., safety, symptom management) and improve patient and caregiver outcomes.23, 24 The framework was used to guide the questions that were asked to identify unique care needs of PWD and their caregivers.

Figure 1. Transitional Care Framework.

Methods

Design

From August 2020 to July 2021, we conducted a qualitative study using focus groups and interviews with stakeholders in SNFs with experience with Connect-Home. The study was supported by a steering committee, comprised of caregivers of PWD (recruited from an adult day program), research team members, and a SNF executive. Committee members participated in virtual (Zoom) meetings to review study procedures and support interpretation of findings. Findings were reported using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ).25 Approval for study activities was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Setting and Sample

The setting was four SNFs that implemented Connect-Home in a completed pilot study (2014–2017)20 and sustainment project (2018–2019), and continue to sustain the intervention.26 The rationale for setting the research in these SNFs was to elicit perspectives of stakeholders with experience using a transitional care model. Participants were recruited in two phases. First, we recruited SNF nurses, social workers, rehabilitation therapists, and others to participate in focus groups (N=4 groups). Group membership was limited to SNF staff with daily experience using the transitional care model (5–6 members per group). Second, we recruited SNF staff, home health nurses, and PWD and their caregivers to participate in semi-structured interviews. We purposefully sampled SNF staff to maximize years of experience and diversity of roles in the transitional care process. We recruited home care nurses who had experience providing care after transitions from SNF to home. For SNF patients, inclusion criteria were (1) short stay in the SNF, (2) ability to speak English, (3) plan for discharge to home, (4) diagnosis of dementia or a Brief Inventory for Mental Status (BIMS) score <13 documented in the Minimum Data Set,27 and (5) a caregiver willing to participate. In this low risk study, we used judgement of skilled nursing staff to discover capacity of individuals to consent. When PWD were unable to consent and had a legally authorized representative who was also a family caregiver (i.e., not a court-appointed guardian), we recruited the family caregiver as the proxy respondent. PWD were excluded if hospital readmission was planned within 30 days of discharge. Caregivers were identified in health records or conversations with SNF staff and were included if they assisted with care at home and spoke English. SNF patients and caregivers were recruited and consented remotely (via Zoom) and by telephone.

Data Collection

Experienced qualitative researchers collected data in two phases (MV and MT). A group moderator (MV) used a semi-structured guide to lead focus groups with staff members in four SNFs (Supplementary Material). The focus groups were designed to facilitate conversations among SNF staff about transitional care and how prepared PWD and their caregivers were for transitions to home. Staff were also asked to compare their experiences caring for patients with and without dementia. Focus groups were conducted virtually via one-hour telephone conferences that were recorded with permission. Data from the focus groups were analyzed and findings were used to refine interview guides for the second phase in data collection, which included individual interviews with SNF and homecare staff, older adults with dementia, and family caregivers. A unique interview guide was developed for each participant group (Supplementary Material). While the form of the questions varied by participant group, each interview guide focused on discharge planning, preparedness for care at home, the impact of dementia on home-based care, and recommendations for improving transitional care. To explore care processes in detail, some SNF staff participated in focus groups and interviews. Telephone interviews, conducted in 30 days after SNF discharge, lasted approximately 30–60 minutes. A standardized instrument was used to abstract data from medical records, such as PWD age, sex, gender and primary diagnosis.

Data Analysis

Focus groups and interviews were transcribed verbatim and entered into ATLAS.ti 9.0 to facilitate analysis (Scientific Software Development GmbH, ATLAS.ti Windows). We used the five-stage framework analytic approach, which included (1) familiarization, (2) identifying a thematic framework, (3) indexing, (4) charting, and (5) mapping and interpretation.28 In stage 1, research team members read the transcripts to become familiar with the data. In stage 2, team members (MV, JL, TV, MT) used the Connect-Home transitional care framework (Table 1) to develop a codebook for indexing data in focus group and interview transcripts. The coding framework included transitional care structures (e.g., tools and training), transitional care processes (e.g., care plan meetings), six key care needs (e.g., symptom management), and patient and caregivers outcomes (Supplementary Material). During the indexing process (stage 3), new codes were added when needed. In stage 3, team members (MV, JL, TV) double coded the transcripts and met regularly to discuss and resolve any coding discrepancies. In stage 4, to chart the data, team members (MV, TV, JL, LH, MT) examined themes across the transcripts and, where possible, described overarching themes about unique care needs during transitions to home-based care. In stage 5, the full research team met to discuss and interpret the findings, and a report from this meeting was presented to the steering committee for their input on the validity of findings and feasibility and acceptability of recommendations.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Sample (N=46)

| Type | Characteristic | |

|---|---|---|

| Person with Dementia (n=10) | Age, mean years (SD*) | 78.5 (8.5) |

| Female, n (%) | 5 (50%) | |

| White race, n (%) | 10 (100%) | |

| Dementia diagnosis, n (%) | 6 (60%) | |

| Problem list with >5 diagnoses, n (%) | 10 (100%) | |

| SNF† length of stay, mean days (SD) | 25.4 (14.6) | |

| Discharge to home, n (%) | 8 (80%) | |

| Discharge to assisted living, n (%) | 2 (20%) | |

| Caregiver (n= 10) | Age, mean years (SD) | 67.4 (9.5) |

| Female, n (%) | 7 (70%) | |

| White race, n (%) | 10 (100%) | |

| Spouse, n (%) | 5 (50%) | |

| Adult child, n (%) | 5 (50%) | |

| Years as caregiver, mean years (SD) | 1.9 (0.7) | |

| Staff (n= 26) | SNF 1, n (%) | 5 (19%) |

| SNF 2, n (%) | 6 (23%) | |

| SNF 3, n (%) | 6 (23%) | |

| SNF 4, n (%) | 5 (19%) | |

| Home Care, n (%) | 4 (15%) | |

| Female, n (%) | 26 (100%) | |

| Manager, n (%) | 4 (15%) | |

| Nurse, n (%) | 17 (65%) | |

| SNF SW‡, n (%) | 4 (15%) | |

| Other SNF staff, n (%) | 5 (20%) | |

Footnotes:

standard deviation

skilled nursing facility

social worker

Results

Of 26 staff who were invited to participate, 26 were enrolled; 22 staff participated in focus groups and 8 staff (4 SNF and 4 homecare) participated in interviews. Of 11 paired PWD and caregivers who were invited to participate, 10 pairs were enrolled; 3 PWD and 10 caregivers were able to participate in interviews (Table 1). Thus, 39 individuals participated in the focus groups and interviews. PWD and caregivers reported white race. The sample included 6 individuals with documented diagnosis of dementia; four others, with BIMS scores less than 13, had persistent problems with thinking and memory that affected function, consistent with probable dementia. Most index hospital stays were for acute infections (40%) and hip/pelvic fractures (40%). Eight PWD transferred from SNF to home and 2 transferred to assisted living.. We retained the transcripts of interviews with caregiver of individuals who transferred to assisted living in the analysis after determining they included themes similar to caregivers for individuals who transferred to home. Most caregivers were related to the PWD as a spouse (50%) or adult child (50%).

Unique transitional care needs of people with dementia in SNFs and their caregivers.

Collectively, participants described four unique care needs in transitional care for persons with dementia and their caregivers: (1) PWD and caregivers may not be ready to fully engage in dementia care planning while in the SNF, (2) caregivers are not prepared to manage dementia symptoms at home, (3) SNF staff have difficulty connecting PWD and caregivers to community supports, and (4) caregivers receive little support to address their needs. These care needs are summarized in Table 2 and presented in greater detail below.

Table 2.

Unique Care Needs and Exemplar Quotations

| Unique Care Need | Caregiver Perspectives | Staff Member Perspectives |

|---|---|---|

| PWD and caregivers may not be ready to fully engage in dementia care planning while in the SNF. | “They did tell me that he [patient] needed 24-hour care…and that I would need some assistance…I turned that all down because I thought I could do it myself. Well, I proved that I could not…Now, I understand I was supposed to get a nurse…but I never did.” (Participant 20) | “We’ll have meetings and you just don’t feel like the caregiver’s getting it, and you don’t really get that reassurance. Whether they’re just not understanding, or they’re just not buying into it, or they’re just overwhelmed.” (Participant 12) |

| Caregivers are not prepared to manage dementia symptoms at home. | “I have two cochlear implants so I remove my processors when I go to bed. If he needs me in the night, he knows to wake me. But if he would get up, I’m concerned he would get up and fall in the bathroom. I might not know it for a while.” (Participant 17) | “It’s important to have the families involved upfront, so that…the family is aware of additional deficits the patient might have that would necessitate more supervision at home…And we are finding recently that we’re having to make those decisions quicker and quicker…” (Participant 31) |

| SNF staff have difficulty connecting PWD and caregivers to community supports. | “I can look…on the internet to try to find something…but as far as someone to talk to and consult with dealing with dementia…No, I don’t feel like I have that at all. I don’t know who I would talk to.” (Participant 24) | “They can’t afford to pay for it privately and they don’t qualify for Medicaid…we see that a lot…they’re really in a quandary and then there’s only so many services they can afford…” (Participant 13) |

| Caregivers receive little support to address their own needs | “It’s just hard work for somebody to try to do, 80 or 90% of what a person is not able to do. It don’t matter who’s taking care of anybody, it’s gonna be hard on them.” (Participant 28) | “A lot of these families may not have taken care of their loved ones in the state that they leave here…So that adds a whole ’nother demand…you know, maybe the patient’s not lived with them and then we’re discharging them with the family, and that just adds a lot of emotional pieces to that, it’s exhausting.” (Participant 15) |

PWD and caregivers may not be ready to fully engage in dementia care planning while in the SNF.

SNF staff reported that many caregivers and patients were not ready to acknowledge the extent of cognitive decline and therefore were not ready to engage in dementia care planning. As one social worker noted, “It’s all going to depend on the family’s level of acceptance before you’re really able to do anything” (Participant 2). Home care nurses reported that caregivers often do not recognize the extent of cognitive decline until after the PWD has been discharged to home. A home care nurse stated, “I’ve actually had that several times, where…the caregiver and the patient say, ‘No, we’re not confused. There’s no problems...’ And then, a week or two in, the caregiver says, ‘Yes, I am starting to see what they were saying now’” (Participant 32). SNF staff were most concerned about how difficult it was to engage PWD and caregivers in developing plans to reduce safety risk, including risks related to falls, driving, wandering, meal preparation, and medication management, among others. Multiple staff highlighted the specific challenge of helping PWD and caregivers to recognize the need for someone to be present 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Caregivers are not prepared to manage dementia symptoms at home.

Caregivers raised concerns about the lack of guidance they received on how to manage symptoms of dementia. One caregiver noted, “It [SNF planning] was all about…the physical needs” (Participant 22). This same caregiver expressed an unmet need for a “dementia care plan.” Some caregivers were surprised when loved ones with dementia experienced worsened confusion and distress. A caregiver said, “When she [PWD] first got home…she cried for hours at a time…she just felt like she was being a burden and she just wanted to die” (Participant 24).

Caregivers reported being unprepared to manage the impact of dementia symptoms on their efforts to manage co-occurring illnesses. For example, caregivers administered more than 10 medications per day and described difficulty with family members who resisted taking medications. Some caregivers described challenges managing pain; one caregiver reported, “not really understanding how much pain she [person with dementia] was in” (Participant 26). Additionally, caregivers described how symptoms of dementia limited their ability to support activities of daily living, such as bathing and dressing. One caregiver stated, “I have to try to convince her [patient] to use a cane and it just gets very contentious…because she feels like I’m trying to tell her everything to do” (Participant 22). Three caregivers reported their family member with dementia fell shortly after returning to home. One added, “I did not know how bad his dementia was because it got worse during his accident. How to know – him not being able to give me at least 80% help when dressing him or him going to the bathroom” (Participant 20). Some SNF staff reported that they had limited knowledge about managing dementia care at home. A social worker stated, “I understand how dementia works here in this building…I could use some education as to how that really does work out in the world… how do other people go about successfully supporting people with dementia at home?” (Participant 31).

SNF staff have difficulty connecting PWD and caregivers to community supports.

Participants identified community supports that PWD and caregivers might use following discharge, including adult day care, pharmacy delivery services, personal care services, and home care, among others. SNF staff identified cost as a primary barrier to accessing those supports. A social worker said, “A lot of times they make too much money to qualify for Medicaid, but then they don’t make enough to cover it out of pocket” (Participant 11). Some caregivers and PWD had difficulty connecting with service providers. A social worker noted, “You can’t just give them a phone number or anything like that. They actually have to have you dial the phone and hand it to them and then help them understand what it is they’re hearing” (Participant 6). Furthermore, when SNF staff were able to connect PWD and caregivers to community supports, the PWD sometimes terminated the support. A SNF nurse noted, “So, you can put all these things in place but when they get home, they can refuse to have home health come in, they can refuse to answer calls” (Participant 3). Several SNF staff made the case that coordinating with community supports was best done by providers in the community. One SNF nurse stated “We’re sort of inside the fence, if you will. We’re not out there roaming the neighborhood. I would say, really, that home health agencies would have to pick up that deficit, if you will, because they’re the ones who are out there in the community” (Participant 5).

Caregivers receive little support to address their own needs.

SNF and home care staff consistently identified support for caregivers as an unmet need, “Something that really, really gets over-looked” (Participant 31). One caregiver said, “I could probably use some support, if, you know, if I would just go and ask for it, but again, I’m not someone who is comfortable with asking for a lot of help.” (Participant 25). Staff worried caregivers would “overdo it” and “wear themselves out.” A nurse explained, “They have a loss of that person…and sometimes the family gets to feeling so disconnected and frustrated with themselves because they are grieving” (Participant 3). When caregivers were asked, “How prepared are you to take care of yourself?” some related stories of resilience. “I learned that I need to stop and do things for myself” (Participant 28); others described feeling “uncertain,” “frantic,” and “exhausted.”

Discussion

In this qualitative study, we identified unique care needs that PWD and caregivers experience during care transitions from SNF to home. While limited by our study design and sample, the findings support and extend earlier research, and provide evidence for adapting transitional care of PWD and their caregivers, as described below.

We found PWD and caregivers often were not ready to engage in dementia care planning to address emerging safety risks while in the SNF. Prior research suggests that PWD and caregivers may experience a period of adjustment that limits their ability to recognize new safety risks and make plans to address them.14, 29, 30 Other research suggests that discharge processes may be rushed and provide families limited time for planning effectively.31 Adding to this research, our findings suggest that caregivers need more detailed information on reducing safety risks in the SNF, and that they may not be ready to fully engage with that information until after the transition to home.

Our study also found that caregivers reported a lack of preparation to provide day and night supervision; to manage symptoms of resistance, distress, and confusion; and to support medications and function, especially to prevent falls. Earlier studies reported similar challenges31–33 and demonstrated the value of educating PWD and family caregivers on how to lessen emotional and behavioral symptoms of dementia.34, 35 Little is known about how transitional care prepares caregivers for this role. Our findings suggest SNF staff have limited knowledge/skills related to dementia or how to manage symptoms of dementia at home or to access resources available in the community. New training and tools for SNF staff may be necessary to build capacity for providing effective transitional care for PWD and their caregivers.

Our study also identified the unmet needs of caregivers. The responsibilities of caregivers in dementia are known to exceed many other caregiving roles.36, 37 We found that caregiving activity surged during SNF-to-home transitions. Thus, to support caregivers, effective transitional care must include plans for respite and check-ins, such as telephone-based support provided by dementia caregiving specialists.

This study has limitations, most importantly, the generalizability of findings, which is limited by the small sample size from four SNFs in a single organization in one state. Limitations in the sample size may have prevented saturation; thus, future research is needed to explore differences in the needs of PWD and their caregivers, for example, when the PWD is discharged to assisted living versus home. Another limitation, as with other studies of dementia, was our reliance on measures of cognitive impairment and diagnosis to arrive at the study population. Another limitation is the lack of diversity in the sample of PWD and caregivers. Future research in a larger group of SNFs and SNFs with greater diversity is essential to determine needs of individuals and families from under-represented regions, groups, and racial and ethnic minorities. Strengths of the study are supported by elements in the study design. The research team – with expertise in transitional care, geriatrics, and dementia – used data from multiple points of view, which facilitated our ability to triangulate data and bolster the validity of findings. Other strengths were setting the study in SNFs where staff had experience using a transitional care model and our steering committee that assisted in interpretation of findings.

A key implication of this study is the need to adapt transitional care for PWD and their caregivers. As a first step, the research team and our steering committee identified opportunities to adapt Connect-Home. In Table 3, a summary of each Connect-Home structure and process is followed by recommended adaptations. Our recommendations accord with prior research. First, careful assessment and medical consultation is necessary to rule-out and treat delirium and other non-dementia causes of cognitive impairment.38 Then, when dementia or probable dementia is identified, transitional care must focus on relief of dementia symptoms and safety at home.39 Third, transitional care should (1) examine care transitions in the context of dementia health trajectories,14, 40, 41 (2) plan care with dementia-specific goals,31, 39, 42, 43 train caregivers to manage dementia symptoms,31, 39, 42 and communicate dementia diagnosis and plans to community providers.39, 42, 44

Table 3.

Adapting SNF transitional care for people with dementia and their caregivers

| Process: Services and supports for PWD and Caregivers | |

|

| |

| Step 1 – transitional care in the SNF | • Set goals for home-based care. Use a modified EHR-template for the discharge summary form to record plans for safety and supervision, medical follow-up, medications, and symptom management at home. Adapt to include: ○ Identification of delirium, dementia or probable dementia ○ Dementia symptom management ○ Strategies for communication, ADLs, medication administration |

| • Meet to plan the patient’s transition to home-based care. In a care plan meeting, review plans for care at home, discuss preferences, set priorities, and educate the patient and caregiver. Adapt to include: ○ Observed problems with memory and thinking ○ Dementia care plan based on observed symptoms and safety needs • Prepare the patient and caregiver for home-based care. Teach skills for care at home, reconcile medications, schedule follow-up appointments, and initiate discharge (e.g., teach the written TPOC and transmit medical records to community providers). Adapt to include: ○ Dementia care plan focused on comfort and safety at home ○ Referrals for dementia evaluation and/or specific services and supports ○ Communication of the dementia care plan with primary care provider | |

|

| |

| Step 2 – transitional care at home |

• Implement the transition plans at home. In post discharge calls and/or home care visits, review the TPOC, set-up new care routines, triage medical questions, and coordinate follow-up care. Adapt to include: ○ Home care with person with dementia and caregiver ○ Plans to prevent falls and to assess and manage pain ○ Activation community-based services and supports. |

|

| |

| Structure: Tools and Training for Staff | |

|

| |

| Tools | • Electronic health record (EHR) template to create a patient-centered discharge summary form. Adapt to include: ○ a section for the dementia care plan ○ dementia specific services and resources. • Staff manual, add dementia care and resources |

| Training | • Training with SNF and home care nurses, therapists, social workers; training includes staff roles and the 2-step transitional care process. Adapt to include: ○ dementia content, e.g., dementia screening and symptom management. |

Conclusion and Implications

Supporting successful community discharge is an essential element of post-acute care. In this study, participants identified unique care needs during transitions from SNFs to home or assisted living. Research is needed to confirm these findings in larger, more diverse samples and to adapt transitional care for the unique needs of PWD and their caregivers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Jacquelyn Covington, Megan Sprinkle, and members of the project steering committee. The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis and preparation of paper

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (3R01NR017636–03S1).

References

- 1.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress; 2019. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar19_medpac_entirereport_sec_rev.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed February 1 2020.

- 2.Bardenheier BH, Rahman M, Kosar C, et al. Successful Discharge to Community Gap of FFS Medicare Beneficiaries With and Without ADRD Narrowed. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69(4):972–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke RE, Xu Y, Ritter AZ. Outcomes of post-acute care in skilled nursing facilities in Medicare beneficiaries with and without a diagnosis of dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sloane PD, Schifeling CH, Beeber AS, et al. New or Worsening Symptoms and Signs in Community-Dwelling Persons with Dementia: Incidence and Relation to Use of Acute Medical Services. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65(4):808–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson A, Blenkinsopp A, Downs M, et al. Stakeholder perspectives of care for people living with dementia moving from hospital to care facilities in the community: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 2019;19(1):202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson L, Clare L, Evans K Making sense of dementia and adjusting to loss: psychological reactions to a diagnosis of dementia in couples. Aging Ment Health 2005;9(4):337–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman EA, Boult C Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51(4):556–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naylor MD, Aiken LH, Kurtzman ET, et al. The care span: The importance of transitional care in achieving health reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(4):746–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Berre M, Maimon G, Sourial N, et al. Impact of Transitional Care Services for Chronically Ill Older Patients: A Systematic Evidence Review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65(7):1597–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verhaegh KJ, Seller-Boersma A, Simons R, et al. An exploratory study of healthcare professionals’ perceptions of interprofessional communication and collaboration. J Interprof Care 2017;31(3):397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner RL, Pelland K, Youssef R, et al. Reducing Hospital Readmissions Through a Skilled Nursing Facility Discharge Intervention: A Pragmatic Trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020;21(4):508–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toles M, Colon-Emeric C, Asafu-Adjei J, et al. Transitional care of older adults in skilled nursing facilities: A systematic review. Geriatr Nurs 2016;37(4):296–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ray CA, Ingram V, Cohen-Mansfield J Systematic review of planned care transitions for persons with dementia. Neurodegener Dis Manag 2015;5(4):317–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashbourne J, Boscart V, Meyer S, et al. Health care transitions for persons living with dementia and their caregivers. BMC Geriatr 2021;21(1):285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Roberts TJ, King BJ, et al. Transitions From Hospitals to Skilled Nursing Facilities for Persons With Dementia: A Challenging Convergence of Patient and System-Level Needs. Gerontologist 2017;57(5):867–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terrell KM, Miller DK. Challenges in transitional care between nursing homes and emergency departments. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2006;7(8):499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boustani MA, Sachs GA, Alder CA, et al. Implementing innovative models of dementia care: The Healthy Aging Brain Center. Aging Ment Health 2011;15(1):13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naylor MD, Hirschman KB, Hanlon AL, et al. Comparison of evidence-based interventions on outcomes of hospitalized, cognitively impaired older adults. J Comp Eff Res 2014;3(3):245–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terayama H, Sakurai H, Namioka N, et al. Caregivers’ education decreases depression symptoms and burden in caregivers of patients with dementia. Psychogeriatrics 2018;18(5):327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toles M, Colón-Emeric C, Naylor MD, et al. Connect-Home: Transitional Care of Skilled Nursing Facility Patients and their Caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65(10):2322–2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toles M, Colón-Emeric C, Hanson LC, et al. Transitional care from skilled nursing facilities to home: study protocol for a stepped wedge cluster randomized trial. Trials 2021;22(1):120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toles M, Barroso J, Colón -Emeric C, Corazzini K, et al. Staff interaction strategies that optimize delivery of transitional care in a skilled nursing facility: a multiple case study. Fam Community Health 2012;35(4):334–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toles M, Colón -Emeric C, Naylor MD, et al. Transitional care in skilled nursing facilities: a multiple case study. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berkowitz RE, Fang Z, Helfand BK, et al. Project ReEngineered Discharge (RED) Lowers Hospital Readmissions of Patients Discharged From a Skilled Nursing Facility. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14(10):736–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19(6):349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leeman J, Toles M What does it take to scale-up a complex intervention? Lessons learned from the Connect-Home transitional care intervention. J Adv Nurs 2020;76(1):387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Minimum Data Set 3.0 RAI Manual 2013. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/MDS30RAIManual.html. Accessed March 2017.

- 28.Ritchie J, Spencer L, W OC. Carying out qualitative analysis. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, eds. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradway C, Trotta R, Bixby MB, et al. A Qualitative Analysis of an Advanced Practice Nurse-Directed Transitional Care Model Intervention. Gerontologist 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byrne K, Orange JB, Ward-Griffin C Care transition experiences of spousal caregivers: from a geriatric rehabilitation unit to home. Qual Health Res 2011;21(10):1371–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kable A, Chenoweth L, Pond D, et al. Health professional perspectives on systems failures in transitional care for patients with dementia and their carers: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prusaczyk B, Olsen MA, Carpenter CR, et al. Differences in Transitional Care Provided to Patients With and Without Dementia. J Gerontol Nurs 2019;45(8):15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reinhard S, Young HM. Young Levine, C, Kelly K, Choula RB, Accius J. Home Alone Revisited: Family Caregivers Providing Comlex Care. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prizer LP, Zimmerman S Progressive Support for Activities of Daily Living for Persons Living With Dementia. Gerontologist 2018;58(suppl_1):S74–s87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitlatch CJ, Orsulic-Jeras S Meeting the Informational, Educational, and Psychosocial Support Needs of Persons Living With Dementia and Their Family Caregivers. Gerontologist 2018;58(suppl_1):S58–s73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertrand RM, Fredman L, Saczynski J Are all caregivers created equal? Stress in caregivers to adults with and without dementia. J Aging Health 2006;18(4):534–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moon H, Dilworth-Anderson P Baby boomer caregiver and dementia caregiving: findings from the National Study of Caregiving. Age Ageing 2015;44(2):300–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Medical Directors Association. Transitions in Care in the Long Term Continuum Clinical Practice Guideline. Columbia, MD: AMDA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirschman KB, Hodgson NA. Evidence-Based Interventions for Transitions in Care for Individuals Living With Dementia. Gerontologist 2018;58(suppl_1):S129–s140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gallagher-Thompson D, Choryan Bilbrey A, Apesoa-Varano EC, et al. Conceptual Framework to Guide Intervention Research Across the Trajectory of Dementia Caregiving. Gerontologist 2020;60(Suppl 1):S29–s40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas JM, Cooney LM Jr., Fried TR. Prognosis as Health Trajectory: Educating Patients and Informing the Plan of Care. J Gen Intern Med 2021;36(7):2125–2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.American Medical Directors Association. Dementia in Care Transitions; 2016. https://paltc.org/amda-white-papers-and-resolution-position-statements/dementia-care-transitions. Accessed July 7 2021.

- 43.Ritchie K, Duff-Woskosky A, Kipping S Mending the Cracks: A Case Study in Using Technology to Assist with Transitional Care for Persons with Dementia. World Health Popul 2019;18(1):90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindquist LA, Miller RK, Saltsman WS, et al. SGIM-AMDA-AGS Consensus Best Practice Recommendations for Transitioning Patients’ Healthcare from Skilled Nursing Facilities to the Community. J Gen Intern Med 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.