Abstract

Rationale

The relationship between eczema, wheeze or asthma, and rhinitis is complex, and epidemiology and mechanisms of their comorbidities is unclear.

Objectives

To investigate within-individual patterns of morbidity of eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis from birth to adolescence/early adulthood.

Methods

We investigated onset, progression, and resolution of eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis using descriptive statistics, sequence mining, and latent Markov modeling in four population-based birth cohorts. We used logistic regression to ascertain if early-life eczema or wheeze, or genetic factors (filaggrin [FLG] mutations and 17q21 variants), increase the risk of multimorbidity.

Measurements and Main Results

Single conditions, although the most prevalent, were observed significantly less frequently than by chance. There was considerable variation in the timing of onset/remission/persistence/intermittence. Multimorbidity of eczema+wheeze+rhinitis was rare but significantly overrepresented (three to six times more often than by chance). Although infantile eczema was associated with subsequent multimorbidity, most children with eczema (75.4%) did not progress to any multimorbidity pattern. FLG mutations and rs7216389 were not associated with persistence of eczema/wheeze as single conditions, but both increased the risk of multimorbidity (FLG by 2- to 3-fold, rs7216389 risk variant by 1.4- to 1.7-fold). Latent Markov modeling revealed five latent states (no disease/low risk, mainly eczema, mainly wheeze, mainly rhinitis, multimorbidity). The most likely transition to multimorbidity was from eczema state (0.21). However, although this was one of the highest transition probabilities, only one-fifth of those with eczema transitioned to multimorbidity.

Conclusions

Atopic diseases fit a multimorbidity framework, with no evidence for sequential atopic march progression. The highest transition to multimorbidity was from eczema, but most children with eczema (more than three-quarters) had no comorbidities.

Keywords: asthma, wheeze, eczema, atopic march, birth cohorts

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

The relationship between eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis is complex, and there is an ongoing controversy over the epidemiology and mechanisms of comorbidity. One paradigm is atopic march, which describes the progression of atopic disease in an individual as a sequential development starting with eczema in infancy and progressing to wheezing/asthma, and then rhinitis, in later childhood.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis are not independent from each other, but there is no specific or typical sequence of symptoms development that characterizes atopic multimorbidity. Physicians should inquire about different atopic disorders if a child presents with one but should not make recommendations about ways to prevent atopic march or inform parents that children with eczema may later develop asthma.

Childhood eczema, wheezing/asthma, and rhinitis are often referred to as atopic diseases (1, 2). The clinical presentation encompasses multiple phenotypes, and some patients have symptoms affecting a single organ, whereas others have symptoms of varying severity affecting several organs (3, 4). The pathophysiological mechanisms that underpin this heterogeneity are largely unknown.

The relationship between atopic diseases is complex, and there is an ongoing controversy over the epidemiology and mechanisms of comorbidity (5). One paradigm is atopic march, which, as originally proposed, described their progression in an individual as a sequential development starting with eczema in infancy and progressing to wheezing/asthma, and then rhinitis, in later childhood (6, 7). A specific sequence is implicit by the use of the term march (2). This framework is extended to the recommendation that primary care physicians “should inform parents that children with eczema may later develop asthma” (8) and has underpinned clinical trials specifically aiming to prevent wheezing/asthma in children with early-life eczema (9, 10). However, some studies have shown a substantial heterogeneity among patients in the chronology of symptom development (11–13), questioning a specific sequence of atopic march (14). Application of Bayesian machine learning to model the development of eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis from birth to school age in two birth cohorts revealed eight latent profiles of symptom development, each with different temporal patterns of their comanifestation (15), and distinct genetic associates (16). Thus, the evidence to date is convincing that atopic diseases coexist (1, 17–19); however, although there is increasing acknowledgment of different trajectories (19, 20), a comprehensive analysis of their long-term evolution within individuals is lacking, and the mechanisms of their coexistence remain unclear (5).

Atopic comorbidities may occur because of the effects of an index disease (as in atopic march, in which eczema, as the index disease, impacts the future risk of wheeze/asthma and rhinitis [7]) or in a multimorbidity framework, in which no single condition holds priority over any cooccurring condition (21). However, cooccurrence can also occur by chance; for example, if the population prevalence of eczema is 25%, and wheeze 30%, by chance alone we would expect 7.5% of individuals (0.25 × 0.3 = 0.075) to have both. To capture the spectrum of morbidity of atopic disease from birth to adulthood, we investigated patterns of onset, remission, and persistence of eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis using data from four birth cohorts and used sequence-mining techniques to disaggregate and describe within-individual patterns. To ascertain whether there is evidence for shared genetic architecture across different patterns of cooccurring diseases, we took a candidate gene approach by investigating associations with Filaggrin loss-of-function mutations and a representative variant from 17q21 locus.

Methods

Study Design, Setting, Participants, and Data Sources

Methods are described in detail in the online supplement. Briefly, we used data from four U.K. population−based birth cohorts in the STELAR (Study Team for Early Life Asthma Research) consortium: Ashford (22), Isle of Wight (IOW) (23), Manchester Asthma and Allergy Study (MAAS) (24) and Aberdeen cohort (SEATON) (25). All studies recruited pregnant women who gave birth to 642, 1,456, 1,184, and 1,924 children, respectively, between 1989 and 1999. All studies were approved by research ethics committees. Informed consent was obtained from parents, and participants gave their assent/consent when applicable. Data were integrated in a web-based knowledge management platform to facilitate joint analyses (26).

Information on symptoms was collected using validated questionnaires administered on multiple occasions from infancy to adolescence/early adulthood (seven in Ashford over 14 yr, six in MAAS over 16 yr, six in SEATON over 14 yr, and six in IOW over 26 yr). The cohort-specific follow-up time points, the questions used to define variables, and sample sizes are shown in Table E1 in the online supplement.

Definition of Outcomes

We ascertained current eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis at each follow-up. For each individual at each time point we derived a variable summarizing the presence/coexistence of individual diseases: 1) no disease; 2–4) single disease: only eczema (E), only wheeze (W), or only rhinitis (R); 5–7) combinations of two diseases: eczema+wheeze (E+W), eczema+rhinitis (E+R), or wheeze+rhinitis (W+R); and 8) atopic triad (multimorbidity): eczema+wheeze+rhinitis (E+W+R).

Definitions of all variables are presented in the online methods and Table E2.

Genotyping

Genotyping and quality control are described in the online supplement. Briefly, FLG was genotyped using TaqMan-based allelic discrimination assay for R501X and S3247X loss-of-function mutations, and a fluorescent-labeled PCR for 2282del4 (27). Children carrying one or more of the three genetic variations were considered as having a FLG loss-of-function mutation. For the 17q21 locus, we used the SNP rs7216389 in the GSDMB, which was coded for its risk allele (T); an additive model was used.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive cross-sectional analyses

We calculated the prevalence of single and cooccurring conditions at each time point. Based on the point prevalence of eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis at each time in each cohort, we calculated the probabilities of symptom coexistence in the same individual being observed by chance. We then compared observed and expected probabilities across populations and time points to ascertain which cooccurrence patterns were observed more frequently than by chance using the exact binomial test with Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to account for multiple comparisons.

Longitudinal analyses

We used two approaches to longitudinal analyses among subjects with complete information on all three symptoms or diseases at all follow-ups: sequence analysis and multivariate latent Markov modeling (LMM).

Sequence analysis described and visualized trajectories and transitions. We then used multinomial logistic regression models to ascertain if early-life eczema or wheeze as index diseases and rs7216389 and FLG (including their interaction) increased the risk of multimorbidity thereafter; results are reported as relative risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

LMM was used for measuring the dynamics of change between successive time points (28, 29). The optimal number of states was identified using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) index in conjunction with interpretation of the conditional response probabilities. Finally, we explored associations between derived latent states and allergic sensitization and ascertained their genetic associates. All analyses were conducted in R using the LMest (30) and TraMineR (31) packages.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of study populations and comparisons among subjects included and excluded in the longitudinal analyses are shown in Table E3. Maternal smoking was significantly less common among included participants in all cohorts.

Descriptive Cross-Sectional Analyses

Table 1 shows prevalence of eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis and their cooccurrence at each time point across cohorts. Having a single disease was much more common than cooccurrence at all time points and in all cohorts, with approximately one-third of study participants experiencing a single disease compared with 7–14% with two (Table E4). E+W+R multimorbidity was relatively rare throughout the observation period (∼2–4% by the final time point) and increased gradually from infancy to age 4–5 years, with little change thereafter (Tables 1 and E4).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Morbidity at Each Cross-Sectional Time Point

| Cohort | n | Eczema Only | Wheeze Only | Rhinitis Only | Wheeze + Eczema | Wheeze + Rhinitis | Eczema + Rhinitis | Eczema + Wheeze + Rhinitis | No Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAAS | |||||||||

| 1 yr | 935 | 225 (24.1) | 130 (13.9) | 3 (0.3) | 90 (9.6) | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 482 (51.6) |

| 3 yr | 1,049 | 228 (21.7) | 111 (10.6) | 12 (1.1) | 96 (9.2) | 10 (1.0) | 8 (0.8) | 16 (1.5) | 568 (54.2) |

| 5 yr | 1,034 | 172 (16.6) | 82 (7.9) | 111 (10.7) | 40 (3.9) | 54 (5.2) | 69 (6.7) | 54 (5.2) | 452 (43.7) |

| 8 yr | 1,020 | 125 (12.3) | 56 (5.5) | 124 (12.2) | 32 (3.1) | 45 (4.4) | 76 (7.5) | 51 (5.0) | 511 (50.1) |

| 11 yr | 912 | 95 (10.4) | 47 (5.2) | 155 (17.0) | 22 (2.4) | 65 (7.1) | 57 (6.3) | 39 (4.3) | 432 (47.4) |

| 16 yr | 734 | 46 (6.3) | 29 (4.0) | 193 (26.3) | 13 (1.8) | 51 (7.0) | 51 (7.0) | 31 (4.2) | 320 (43.6) |

| Ashford | |||||||||

| 1 yr | 454 | 22 (4.9) | 141 (31.1) | 10 (2.2) | 24 (5.3) | 14 (3.1) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.9) | 238 (52.4) |

| 2 yr | 615 | 53 (8.6) | 129 (21.0) | 22 (3.6) | 26 (4.2) | 23 (3.7) | 7 (1.1) | 10 (1.6) | 345 (56.1) |

| 3 yr | 615 | 62 (10.1) | 99 (16.1) | 33 (5.4) | 36 (5.9) | 23 (3.7) | 10 (1.6) | 13 (2.1) | 339 (55.1) |

| 4 yr | 611 | 54 (8.8) | 73 (12.0) | 36 (5.9) | 18 (3.0) | 28 (5.6) | 10 (1.6) | 13 (2.1) | 379 (61.0) |

| 5 yr | 604 | 47 (7.8) | 48 (8.0) | 51 (8.4) | 13 (2.2) | 27 (4.5) | 9 (1.5) | 20 (3.3) | 389 (64.4) |

| 8 yr | 593 | 40 (6.8) | 30 (5.1) | 74 (12.5) | 12 (2.0) | 26 (4.4) | 17 (2.9) | 11 (1.9) | 383 (64.6) |

| 14 yr | 499 | 20 (4.0) | 21 (4.2) | 110 (22.0) | 3 (0.6) | 33 (6.6) | 28 (5.6) | 15 (3.0) | 269 (53.9) |

| IOW | |||||||||

| 1 yr | 1,247 | 87 (7.0) | 38 (3.1) | 64 (5.1) | 21 (1.7) | 52 (4.2) | 21 (1.7) | 18 (1.4) | 946 (75.9) |

| 2 yr | 1,157 | 139 (12.0) | 66 (5.7) | 34 (2.9) | 29 (2.5) | 68 (5.9) | 34 (2.9) | 18 (1.6) | 769 (66.5) |

| 4 yr | 1,157 | 151 (13.1) | 90 (7.8) | 73 (6.3) | 40 (3.5) | 40 (3.5) | 34 (2.9) | 32 (2.8) | 697 (60.2) |

| 10 yr | 1,347 | 88 (6.5) | 121 (9.0) | 173 (12.8) | 17 (1.3) | 76 (5.6) | 20 (1.5) | 38 (2.8) | 814 (60.4) |

| 18 yr | 1,080 | 37 (3.4) | 78 (7.2) | 211 (19.5) | 6 (0.6) | 108 (10.0) | 24 (2.2) | 26 (2.4) | 590 (54.6) |

| 26 yr | 1,028 | 36 (3.5) | 76 (7.4) | 253 (24.6) | 9 (0.9) | 123 (12.0) | 29 (2.8) | 29 (2.8) | 473 (46.0) |

| SEATON | |||||||||

| 6 m | 1,585 | 151 (9.5) | 188 (11.9) | 171 (10.8) | 30 (1.9) | 64 (4.0) | 12 (0.8) | 24 (1.5) | 945 (59.6) |

| 1 yr | 1,507 | 128 (8.5) | 132 (8.8) | 110 (7.3) | 36 (2.4) | 54 (3.6) | 27 (1.8) | 10 (0.7) | 1,010 (67.0) |

| 2 yr | 1,372 | 176 (12.8) | 108 (7.9) | 76 (5.5) | 34 (2.5) | 48 (3.5) | 25 (1.8) | 19 (1.4) | 886 (64.6) |

| 5 yr | 1,175 | 174 (14.8) | 79 (6.7) | 16 (1.4) | 48 (4.1) | 11 (0.9) | 8 (0.7) | 17 (1.5) | 822 (70.0) |

| 10 yr | 883 | 53 (6.0) | 36 (4.1) | 128 (14.5) | 5 (0.6) | 39 (4.4) | 40 (4.5) | 26 (2.9) | 556 (63.0) |

| 15 yr | 703 | 48 (6.8) | 19 (2.7) | 163 (23.2) | 8 (1.1) | 35 (5.0) | 42 (6.0) | 16 (2.3) | 372 (52.9) |

Definition of abbreviations: IOW = Isle of Wight; MAAS = Manchester Asthma and Allergy Study; SEATON = Aberdeen.

Data are given as n (%).

Cooccurrence patterns

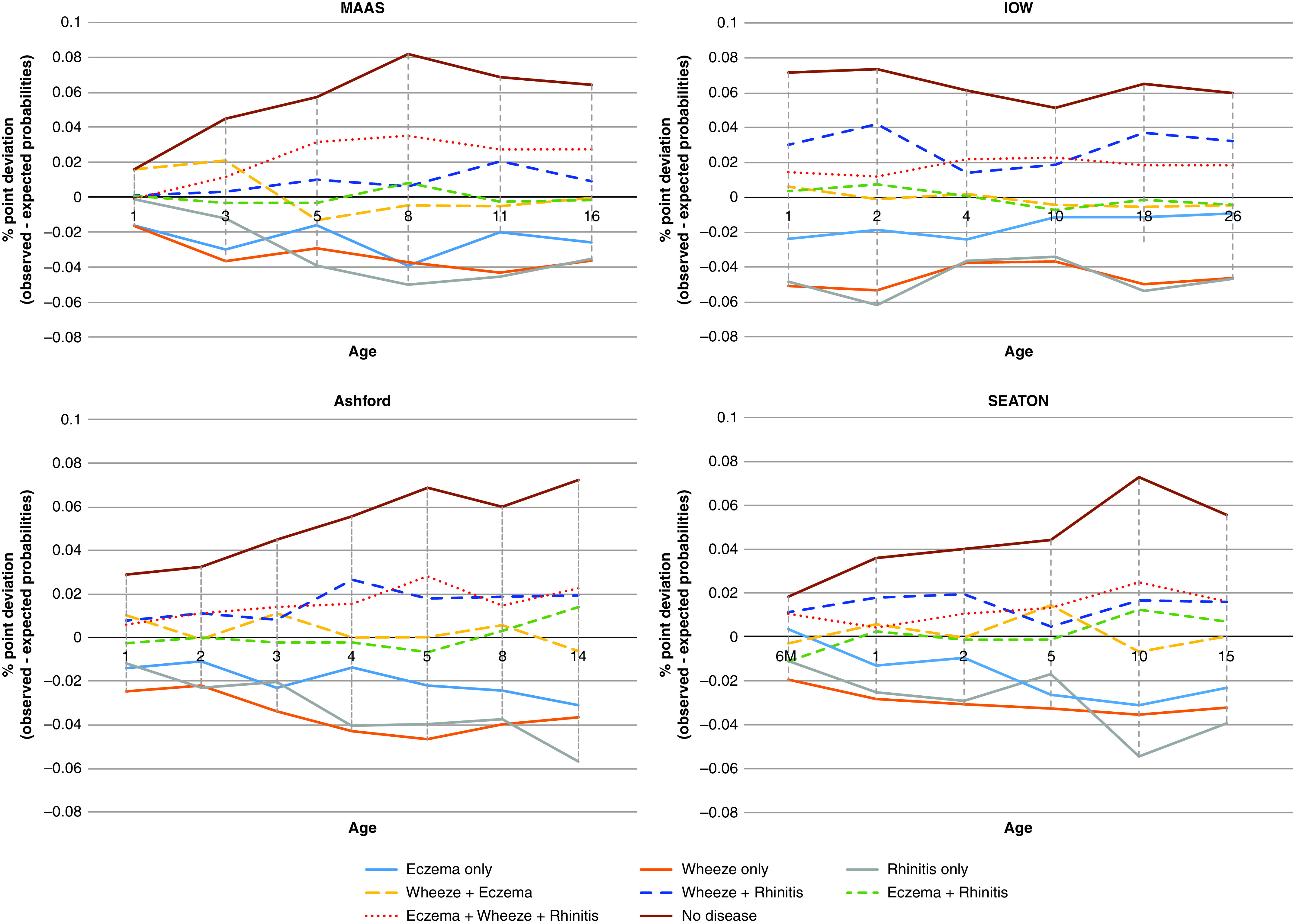

Figure 1 and Table E5 show the deviation of observed from expected probabilities of symptom cooccurrence at each time point. Across all cohorts, single conditions, although the most prevalent cross-sectionally, were observed significantly less frequently than by chance at all follow-ups. In general, two-disease combinations tended to cooccur as often as would be expected by chance. E+W+R multimorbidity was rare but significantly overrepresented in all cohorts and time points (on average, three to six times more often than by chance).

Figure 1.

Trends in the deviation between observed and expected probabilities for each disease category over time (expressed as percentage point difference). Negative numbers show that observed probabilities were lower than expected probabilities; for example, single diseases were observed less frequently than expected in the population, and eczema+wheeze+rhinitis was observed more than expected. IOW = Isle of Wight; MAAS = Manchester Asthma and Allergy Study. SEATON = Aberdeen cohort.

Longitudinal Sequence Analysis

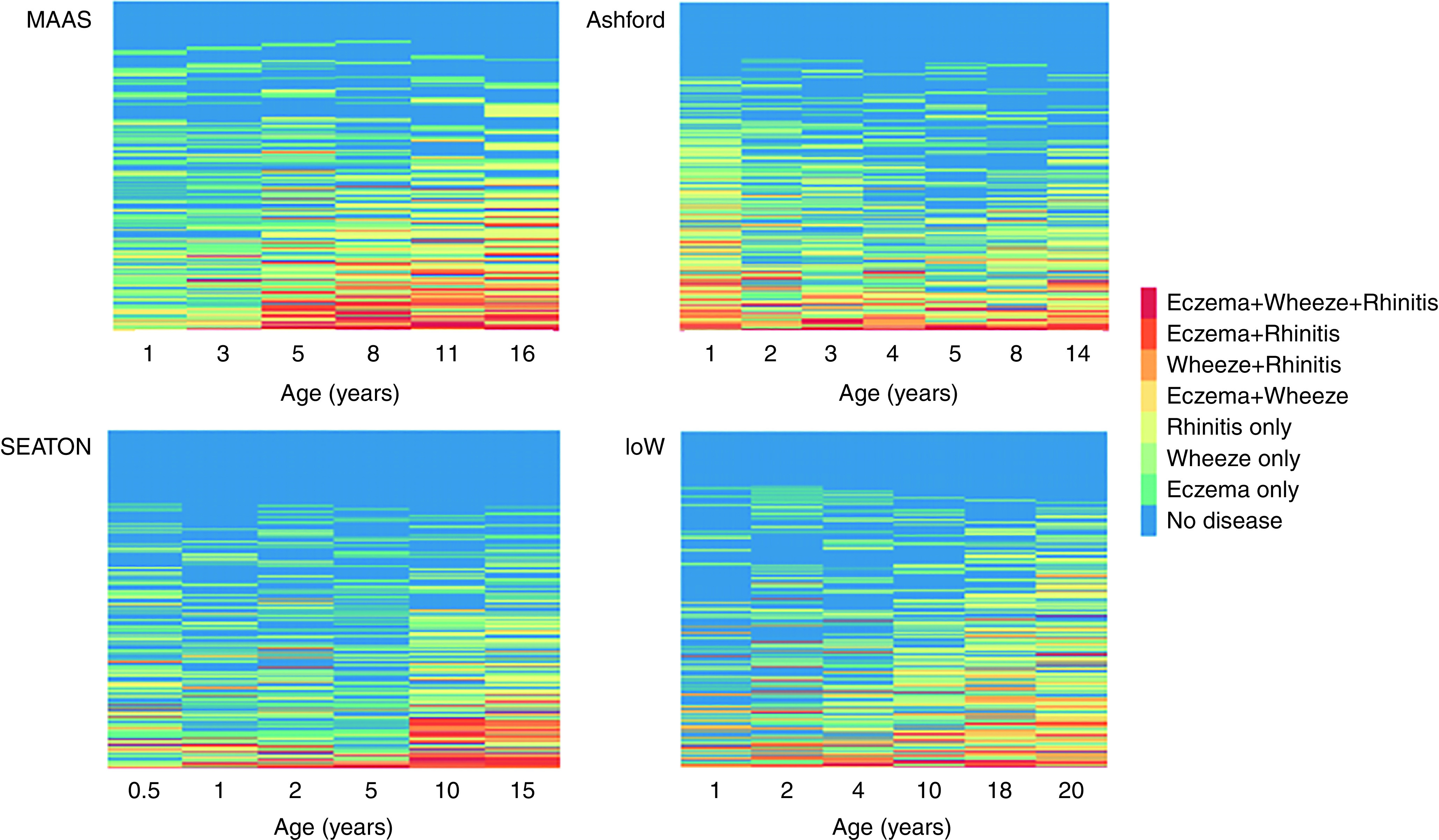

We performed longitudinal analyses among 1,898 participants with complete data at all follow-ups. Figure 2 shows individual-level sequences of symptoms across time. There was no typical trajectory; there was considerable heterogeneity in the onset, remission, and persistence of symptoms. The number of person-unique sequences ranged from 220 to 351 across cohorts. Figure E1 shows sequence frequency plots for 20 most common trajectories, which accounted for only ∼26–32% of all sequences. Among children with eczema (Figure E2) or wheeze (Figure E3) in the first 3 years, transition to no disease was the most common sequence. All three symptoms were reported (including noncontemporaneously) by 374/1,898 (19.6%), and 166 (8.7%) reported coincident E+W+R at least once.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal sequences of the development of eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis (including comorbid conditions) in individual participants in the four cohorts. Each row is colored by the presence of symptoms and their combinations at each time point. The number of person-unique sequences: 220 SEATON (Aberdeen cohort), 259 Ashford, 295 IOW (Isle of Wight), 351 MAAS (Manchester Asthma and Allergy Study).

E+W+R multimorbidity

We performed further analyses exploring symptom development among 166/1,898 (8.7%) participants who experienced E+W+R at least once (Table E6). Of those, 157 (95%) had E+W+R in the school-age, adolescence, or early adulthood period, and 9 (5%) in infancy only. Among 157 participants with E+W+R multimorbidity in the school-age, adolescence, or early adulthood period, the majority (n = 87, 55.4%) had eczema in the first year of life. However, 41 (26.1%) did not have any symptoms in the first year, and 29 (18.5%) had wheeze only. Although infantile eczema was clearly associated with subsequent E+W+R multimorbidity, most children with eczema in the first year of life (267/354, 75.4%), as a single disease or comorbid condition, did not have E+W+R to adolescence or early adulthood.

Early-Life Eczema and Wheeze as Index Diseases

We further investigated the relationship between eczema and wheeze in the first 3 years as index conditions with subsequent persistence, or development of different comorbidity patterns, to preschool, midschool, and adolescence using multivariable logistic regression analyses of joint data at harmonized time points (early life: 0–3 yr; preschool: 4–5 yr; midchildhood: 8–10 yr; adolescence: 14–18 yr). Early-life eczema only was associated with an increased risk of all profiles containing eczema through to adolescence (Table 2); the risk of eczema persistence as a single disease decreased significantly with increasing age, but there was no change in the magnitude of risk for comorbid E+W or E+W+R. Early-life wheeze only was associated with persistence of wheeze, and a threefold increase in W+E and W+R at preschool age, with no consistent comorbidity associations thereafter. Finally, E+W in the first 3 years was associated with substantially higher risk of all comorbidity patterns, with ∼18-fold increase in E+W+R multimorbidity and ∼14- to 21.5-fold higher risk of the persistence of E+W. In all three time periods, early E+W increased the risk of all conditions more than single index diseases.

Table 2.

The Association between Eczema Only, Wheeze Only, and Eczema+Wheeze in First 3 Years as Index Diseases with Subsequent Persistence or Development of Different Patterns of Eczema, Wheeze, and Rhinitis at Preschool, Midschool Age, and Adolescence

| Predictors | E |

W |

R |

E+W |

W+R |

E+R |

E+W+R |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Outcomes at preschool (n = 2,314) | ||||||||||||||

| Early eczema only | 8.32 (6.20–11.17) | <0.001 | 1.21 (0.65–2.23) | 0.550 | 0.58 (0.30–1.12) | 0.106 | 3.04 (1.52–6.11) | 0.002 | 0.13 (0.02–0.95) | 0.044 | 6.98 (4.10–11.88) | <0.001 | 4.64 (2.25–9.58) | <0.001 |

| Early wheeze only | 0.51 (0.23–1.12) | 0.094 | 6.03 (4.04–8.99) | <0.001 | 1.05 (0.57–1.91) | 0.882 | 2.67 (1.18–6.00) | 0.018 | 2.96 (1.66–5.28) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.28–3.18) | 0.933 | 2.01 (0.67–6.03) | 0.211 |

| Early eczema and wheeze | 6.62 (3.38–12.97) | <0.001 | 8.20 (3.94–17.06) | <0.001 | 1.29 (0.43–3.90) | 0.653 | 37.20 (17.92–77.25) | <0.001 | 6.41 (2.65–15.49) | <0.001 | 8.07 (2.96–22.01) | <0.001 | 58.65 (27.39–125.62) | <0.001 |

| Filaggrin loss-of-function mutation | 1.11 (0.73–1.70) | 0.625 | 0.67 (0.34–1.31) | 0.241 | 1.47 (0.86–2.51) | 0.164 | 1.99 (1.04–3.81) | 0.039 | 0.84 (0.35–1.99) | 0.690 | 1.49 (0.72–3.07) | 0.281 | 2.53 (1.30–4.94) | 0.006 |

| rs7216389 | 1.11 (0.92–1.33) | 0.276 | 1.12 (0.88–1.42) | 0.346 | 0.97 (0.76–1.23) | 0.805 | 1.75 (1.23–2.49) | 0.002 | 1.31 (0.95–1.80) | 0.099 | 0.98 (0.70–1.37) | 0.904 | 1.69 (1.15–2.47) | 0.007 |

| Sex (male) | 0.81 (0.63–1.05) | 0.116 | 1.36 (0.98–1.89) | 0.066 | 1.53 (1.09–2.14) | 0.014 | 1.44 (0.88–2.35) | 0.143 | 1.43 (0.91–2.24) | 0.119 | 1.05 (0.65–1.70) | 0.845 | 1.37 (0.80–2.34) | 0.251 |

| Outcomes at midchildhood (n = 2,409) | ||||||||||||||

| Early eczema only | 3.86 (2.73–5.47) | <0.001 | 1.76 (1.03–3.01) | 0.038 | 1.19 (0.82–1.72) | 0.367 | 3.41 (1.41–8.25) | 0.007 | 1.38 (0.78–2.43) | 0.265 | 5.65 (3.58–8.92) | <0.001 | 5.49 (3.11–9.69) | <0.001 |

| Early wheeze only | 0.82 (0.42–1.62) | 0.571 | 4.79 (3.04–7.54) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.55–1.42) | 0.613 | 1.14 (0.25–5.08) | 0.868 | 1.79 (0.99–3.24) | 0.055 | 1.71 (0.81–3.61) | 0.161 | 1.71 (0.64–4.54) | 0.282 |

| Early eczema and wheeze | 4.35 (2.14–8.81) | <0.001 | 6.88 (3.21–14.72) | <0.001 | 1.90 (0.92–3.93) | 0.085 | 40.10 (17.52–91.80) | <0.001 | 6.01 (2.81–12.83) | <0.001 | 6.00 (2.53–14.22) | <0.001 | 24.82 (12.01–51.32) | <0.001 |

| Filaggrin loss-of-function mutation | 1.22 (0.75–2.01) | 0.426 | 1.07 (0.58–1.97) | 0.832 | 1.10 (0.72–1.68) | 0.666 | 1.41 (0.55–3.57) | 0.472 | 1.50 (0.85–2.64) | 0.163 | 1.28 (0.67–2.46) | 0.452 | 3.09 (1.74–5.48) | <0.001 |

| rs7216389 | 1.00 (0.81–1.24) | 0.983 | 1.20 (0.94–1.54) | 0.147 | 1.24 (1.04–1.47) | 0.017 | 1.65 (1.05–2.60) | 0.030 | 1.43 (1.10–1.86) | 0.008 | 0.89 (0.67–1.19) | 0.439 | 1.41 (1.01–1.97) | 0.041 |

| Sex (male) | 0.72 (0.53–0.97) | 0.032 | 1.40 (0.99–2.00) | 0.060 | 1.23 (0.96–1.57) | 0.100 | 0.95 (0.50–1.80) | 0.866 | 1.40 (0.96–2.03) | 0.078 | 0.78 (0.52–1.18) | 0.240 | 0.75 (0.47–1.21) | 0.243 |

| Outcomes at adolescence (n = 1,978) | ||||||||||||||

| Early eczema only | 2.22 (1.31–3.77) | 0.003 | 1.29 (0.63–2.62) | 0.485 | 1.28 (0.92–1.78) | 0.136 | 9.54 (2.60–34.96) | 0.001 | 0.93 (0.51–1.70) | 0.821 | 6.95 (4.36–11.09) | <0.001 | 3.43 (1.78–6.62) | <0.001 |

| Early wheeze only | 1.16 (0.53–2.52) | 0.714 | 4.55 (2.61–7.94) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.59–1.36) | 0.605 | 12.48 (3.22–48.42) | <0.001 | 1.56 (0.88–2.76) | 0.127 | 0.88 (0.34–2.30) | 0.798 | 1.32 (0.45–3.89) | 0.616 |

| Early eczema & wheeze | 3.98 (1.59–9.94) | 0.003 | 6.58 (2.71–16.02) | <0.001 | 1.53 (0.79–2.95) | 0.209 | 58.80 (14.47–239.01) | <0.001 | 3.78 (1.70–8.39) | 0.001 | 2.57 (0.83–7.92) | 0.101 | 17.63 (7.91–39.30) | <0.001 |

| Filaggrin loss-of-function mutation | 0.85 (0.38–1.90) | 0.686 | 1.03 (0.48–2.23) | 0.942 | 1.28 (0.87–1.87) | 0.207 | 0.49 (0.06–3.81) | 0.493 | 1.24 (0.69–2.23) | 0.476 | 2.10 (1.15–3.81) | 0.015 | 2.31 (1.15–4.66) | 0.019 |

| rs7216389 | 0.88 (0.65–1.18) | 0.396 | 1.22 (0.90–1.66) | 0.196 | 0.96 (0.82–1.12) | 0.598 | 1.54 (0.82–2.88) | 0.177 | 1.32 (1.03–1.70) | 0.028 | 1.20 (0.88–1.62) | 0.246 | 1.66 (1.14–2.42) | 0.008 |

| Sex (male) | 0.49 (0.32–0.76) | 0.001 | 0.89 (0.58–1.36) | 0.596 | 1.24 (0.99–1.55) | 0.057 | 0.45 (0.18–1.16) | 0.098 | 1.05 (0.74–1.49) | 0.780 | 1.14 (0.74–1.75) | 0.548 | 0.48 (0.28–0.84) | 0.010 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; E = eczema; R = rhinitis; RRR = relative risk ratio; W = wheeze.

Results are derived from jointly modeling the cohorts by harmonizing time points (early life: age 0–3 yr; preschool: age 4–5 yr; midchildhood: age 8–10 yr; adolescence: age 14–18 yr). The model was adjusted by including a predictor for cohort to control for intercohort differences. Sex, FLG (fillaggrin loss-of-function mutation), and rs7216389 were included as covariates. Results are presented as adjusted RRRs with 95% CIs. “No disease” is the reference category. Boldface represents coefficients that are significant at P ⩽ 0.05.

We found no significant associations between FLG mutations or rs7216389 with persistence of eczema or wheeze as single conditions. However, both were associated with the development of E+W+R multimorbidity (Table 2). In all three models, FLG mutations were associated with a two- to threefold higher risk of E+W+R, and relative risk ratios for rs7216389 were smaller (1.4–1.7) (Table 2). rs7216389, but not FLG, was associated with W+R from midchildhood. We tested for an interaction effect of FLG*rs7216389; however, this was not significant.

We tested the sensitivity of our results using eczema in the first year as the predictor; the associations with each disease category were consistent compared with using eczema in the first 3 years of life (data available on request).

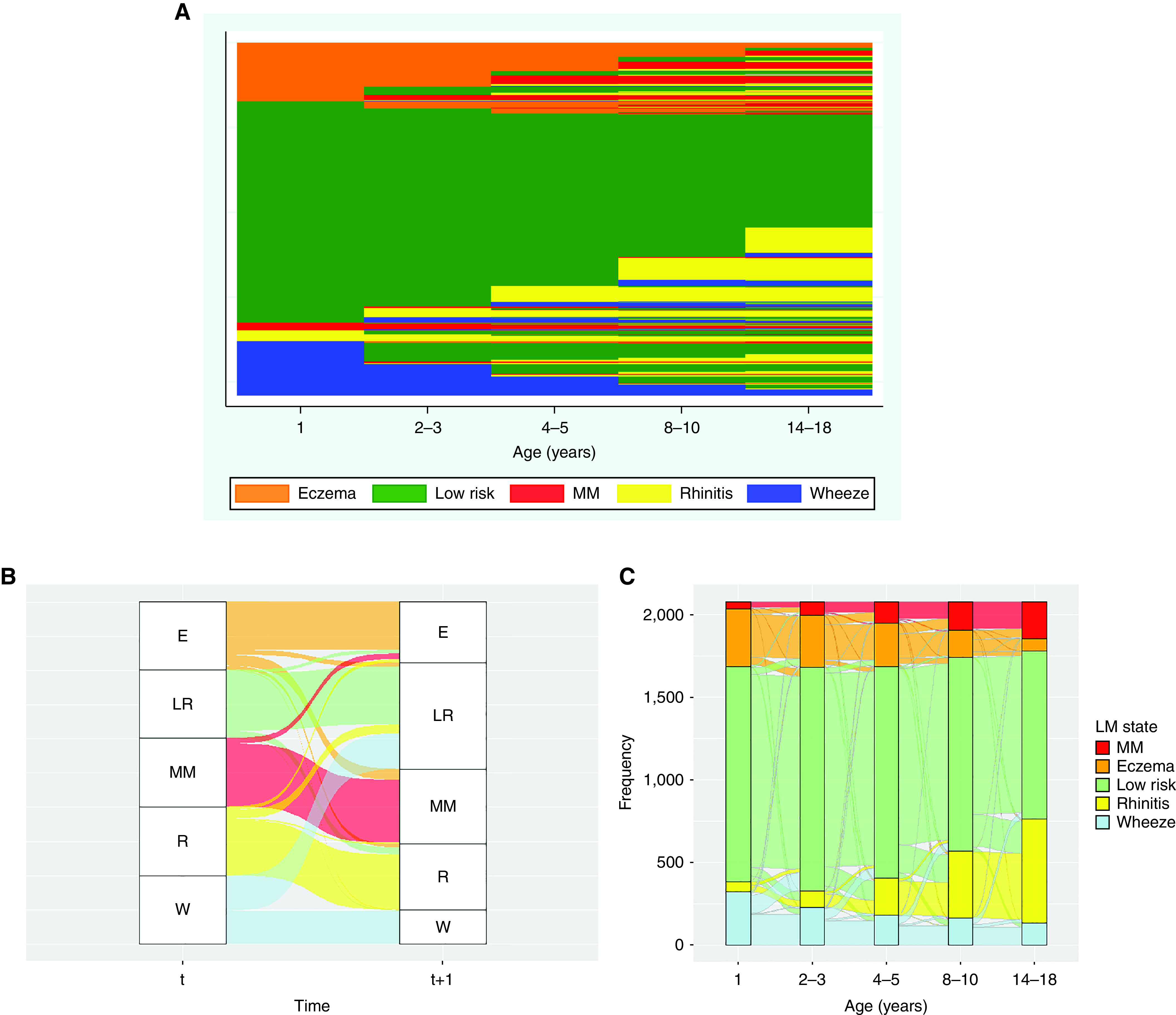

Dynamics of Change Over Time: LMM

We applied LMM in a joint model to data from 2,079 subjects with complete information on eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis at five harmonized time points: infancy (age 1 yr), early life (age 2–3 yr), preschool (age 4–5 yr), midschool (age 8–10 yr), and adolescence (age 14–18 yr) (Table E7). The optimal solution was a time-homogeneous model with five latent states (Table E8). There was a spectrum of comorbidity risk in each latent state (conditional response probabilities; Table 3). We labeled the states based on the probability of dominant symptom as 1) no disease or low risk; 2) mainly eczema; 3) mainly wheeze; 4) mainly rhinitis; and 5) multimorbidity.

Table 3.

Estimated Conditional Responses and Transition Probabilities between Latent States from Latent Markov Model with Five Optimal States and Assuming Time-Homogeneous Transitions

| Conditional response probabilities of observed symptoms for each latent state |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Risk | Eczema | Wheeze | Rhinitis | Multimorbidity | ||

| Observed symptoms | Eczema | 0.05 | 0.857 | 0.061 | 0.061 | 0.459 |

| Wheeze | 0.013 | 0.176 | 0.734 | 0.123 | 0.705 | |

| Rhinitis | 0.001 | 0.138 | 0.092 | 0.562 | 0.845 | |

| Initial probabilities of starting in each latent state |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Risk | Eczema | Wheeze | Rhinitis | Multimorbidity | ||

| 0.627 | 0.166 | 0.154 | 0.031 | 0.022 | ||

| Matrix of transition probabilities |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

t + 1 |

||||||

| Low Risk | Eczema | Wheeze | Rhinitis | Multimorbidity | ||

| t | Low Risk | 0.798 | 0.028 | 0.031 | 0.139 | 0.003 |

| Eczema | 0.116 | 0.619 | 0.011 | 0.048 | 0.207 | |

| Wheeze | 0.278 | 0.021 | 0.591 | 0.083 | 0.028 | |

| Rhinitis | 0.086 | 0.006 | 0.022 | 0.873 | 0.014 | |

| Multimorbidity | 0.044 | 0.054 | 0.062 | 0.064 | 0.777 | |

The transition matrix shows the probability of transitioning between latent state between time t to t + 1 assuming time-homogenous probabilities.

Figure 3A shows predicted latent Markov states across all follow-ups for each individual participant. The initial probabilities of state membership and the probabilities of transitioning to different states are shown in Table 3; Figure 3B shows the relative size of transitions between latent states. The probability of starting in the eczema and wheeze states was similar (0.17 and 0.15) and was close to zero for rhinitis and multimorbidity states (0.03 and 0.02). Children in eczema and wheeze states were most likely to stay in these states (0.62 and 0.59). Children in wheeze state were more likely to transition to no disease than those in eczema state (0.28 and 0.12). The most likely transition to multimorbidity was from eczema state (0.21). However, although this was one of the highest transition probabilities, only one in five children transitioned from eczema to multimorbidity state (Figure 3B). For participants in the multimorbidity state, there was a high probability of persisting in this state (0.78). Figure 3C shows the individual-level transitions between the states at each time point.

Figure 3.

Dynamics of change in eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis over time. Latent Markov modeling in the joint cohort model (2,079 children with complete observations on eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis at five time points). Data were harmonized at overlapping time points to represent five stages of development (infancy: age 1 yr; early childhood: ages 2–3 yr; preschool: ages 4–5 yr; midchildhood: ages 8–10 yr; adolescence: 14–18 yr). (A) Predicted latent Markov states from joint modeling of all four cohorts; each row represents the individual-level latent states across time. (B) Alluvial plot to show relative size of transitions between latent states between time t and t+1 (based on time-homogeneous transition probabilities displayed in Table 4). Children from the eczema (E) state are more likely to persist in the same state. Although relatively small, they are more likely to transition to multimorbidity (MM) than children from other states. Children in the wheeze (W) state are more likely to transition to low risk (LR) than to any other state. R = rhinitis. (C) Dynamics of change in eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis over time. Latent Markov modeling: alluvial plot to show individual-level transitions between predicted latent Markov states at each time point.

Genetic Associations of Multimorbidity Persistence

To investigate whether FLG mutations and rs721389 were associated with multimorbidity state persistence, we ran multinomial logistic regression analyses using the number of time periods in the multimorbidity state (zero, one, two to five) as the outcome (Table 4). Eczema and wheeze states in early life were included as predictors. Neither FLG mutations nor rs721389 were significantly associated with having multimorbidity once, but both significantly increased the risk of persistent multimorbidity. In the model controlling for early-life eczema and wheeze states and sex, FLG mutations significantly increased the risk of multimorbidity persistence (odds ratio, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.05–2.92; P = 0.032), and rs721389 was associated with ∼50% increase in risk (odds ratio, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.15–1.94; P = 0.003). There was no significant interaction between FLG and rs721389.

Table 4.

Multinomial Regression Analyses to Investigate Genetic Associations with Multimorbidity State Persistence

| Model 1 (n = 1,463) |

Model 2 (n = 1,463) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM at 1 TP (n = 84) |

MM at 2–5 TPs (n = 205) |

MM at 1 TP (n = 84) |

MM at 2–5 TPs (n = 205) |

|||||

| RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Wheeze state in early life | 3.00 (1.33–6.76) | 0.008 | 1.00 (0.51–1.95) | 1.000 | 3.00 (1.33–6.77) | 0.008 | 1.00 (0.51–1.95) | 1.000 |

| Eczema state in early life | 39.65 (20.58–76.39) | <0.001 | 19.72 (12.64–30.77) | <0.001 | 39.60 (20.54–76.37) | <0.001 | 19.73 (12.64–30.79) | <0.001 |

| Filaggrin loss-of-function mutation | 0.88 (0.37–2.10) | 0.771 | 1.75 (1.05–2.92) | 0.032 | 0.40 (0.07–2.23) | 0.298 | 1.53 (0.57–4.15) | 0.399 |

| rs7216389 | 1.03 (0.71–1.49) | 0.881 | 1.49 (1.15–1.94) | 0.003 | 0.95 (0.64–1.42) | 0.814 | 1.48 (1.11–1.96) | 0.007 |

| Filaggrin*rs7216389 | — | — | — | — | 2.01 (0.60–6.80) | 0.260 | 1.13 (0.54–2.39) | 0.743 |

| Male | 0.96 (0.57–1.63) | 0.892 | 1.06 (0.73–1.53) | 0.753 | 0.96 (0.57–1.62) | 0.882 | 1.06 (0.73–1.53) | 0.753 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; MM = multimorbidity; RRR = relative risk ratio; TP = time point.

For rs7216389, an additive (dosage) model was used, where the number of risk alleles was treated as a continuous variable in the regression analysis, where 0 = CC (homozygous for the C allele), 1 = CT (heterozygous [one C and one T allele]), and 2 = TT (homozygous [two T alleles]). Outcome is 0: no MM; 1: MM at 1 TP; 2: MM at 2–5 TPs. No MM is the omitted category. Boldface represents coefficients that are significant at P ⩽ 0.05.

Associations of Multimorbidity Persistence with Allergic Sensitization

Table E9 shows associations between multimorbidity and sensitization in preschool and adolescence. Children in the multimorbidity state were more likely to be sensitized, and sensitization prevalence was consistently higher in the group with persistent multimorbidity (two to five time points). A similar trend is evident for polysensitization. However, more than half of subjects with persistent multimorbidity were not sensitized at age 5 years, and ∼30% were not sensitized in adolescence. Characteristics of children with persistent multimorbidity stratified by sensitization status in childhood (age 5 yr) and adolescence (age 14–18 yr) is shown in Table E10. Atopic multimorbidity at both ages was associated with male sex. Maternal eczema was more common in those with nonatopic multimorbidity in school age, but paternal hay fever was associated with a greater risk of atopic multimorbidity. There was a trend toward higher proportion of maternal smoking in nonatopic multimorbidity; however, the difference was not significant.

Discussion

We used different temporal frameworks and different methodologies (descriptive statistics, frequentist methods, and stochastic modeling) to investigate the sequence of the development of eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis from infancy to early adulthood. Figure E4 provides a schematic overview of the results. Across all cohorts and time points, single conditions were considerably more prevalent than any cooccurrence. The combination of two diseases in the same individual occurred as frequently as expected by chance (apart from W+R, which occurred more frequently from midchildhood onward). Although the prevalence of E+W+R multimorbidity was low (2–4% by adolescence), a consistent finding was that this pattern was more prevalent in all cohorts than by chance and was stable from early school age (e.g., in the IOW cohort in which data collection spanned to age 26 yr, the proportion of participants with E+W+R multimorbidity remained at ∼3% from age 4 yr to adulthood).

We identified considerable variation in the timing of onset and remission, persistence, and intermittence of symptoms. All methods led to similar conclusions, including the observation that most children with early-life eczema did not develop wheeze and/or rhinitis, and of those who experienced all three symptoms during the observation period, very few followed a sequence described as the atopic march. Sequence mining of individual trajectories highlighted the vast heterogeneity in individual-level symptom development, and no single pattern dominated, with different trajectories leading to multimorbidity. Although children with early-life eczema had a higher risk of developing multimorbidity than those with early wheeze, the attributable risk for an individual child with early-life eczema was small. This dynamic of change was confirmed by LMM, in that children had higher risk of transitioning to the multimorbidity state from eczema than from wheeze state, but those in eczema state were more likely to remain in the same state than to transition to multimorbidity. Our results suggest that the relationship between atopic diseases fits a multimorbidity framework in which no single disease holds priority over any of the cooccurring conditions (32).

There may be a genetic predisposition for developing multimorbidity, and FLG may be important locus. FLG was not associated with early-onset transient eczema or with eczema persistence as a single disease. However, we showed a consistent association of FLG with persistent multimorbidity (i.e., all patterns leading to coexistence of all three symptoms in the same individual), which is consistent with two previous studies (16, 33). It is tempting to speculate that genotyping patients with early-life eczema (particularly those with cooccurring wheeze) for FLG mutations could help identify children who may benefit from interventions targeted at prevention of multimorbidity.

Our study has several limitations. There were differences in question wording between cohorts, and different definitions can impact prevalence estimates and associated risk factors (34, 35). However, we chose variables to be as consistent as possible. A further limitation relevant for interpretation is that we used symptom-based classifications by questionnaire-based definitions, and from these definitions we could not ascertain whether the severity of eczema (or wheeze) is associated with multimorbidity (10). We could not discern whether observations of the same symptoms in different children (or in the same child at different time points) may have arisen through different mechanisms.

FLG mutations, which we used in this study, play an important role in individuals of White ancestry, but their associations with clinical outcomes differ by race (36). Our results are therefore not transferable to other ethnic groups.

Food allergy might be involved in the transitions to multimorbidity. However, very few population-based birth cohorts have oral food challenge–confirmed data on food allergy. In MAAS, we performed oral food challenges to confirm peanut allergy (37–39) and have shown that the risk is markedly higher among children with persistent eczema (40), and those with comorbid persistent eczema and wheeze, but not with transient phenotypes. In the exploratory single-cohort analysis in the current study, MAAS participants with multimorbidity persistence were five times more likely to have peanut allergy than those without multimorbidity (10% vs. 2%; data available on request), suggesting a link between food allergy and multimorbidity. However, we cannot quantify this confidently, given the relatively small sample, and this warrants further investigation.

For our analyses, we opted to use wheeze instead of asthma. Although not all wheezers have asthma diagnosis (41, 42), wheeze is the most common manifestation of asthma. One of the difficulties in population-level studies is that there is no formal operational definition of asthma, and preschool children are rarely diagnosed as having asthma (43).

One strength of our approach is that we used data from four birth cohorts with detailed longitudinal phenotyping, which were harmonized to allow joint analyses. Further strength includes the application of various methodologies, with all findings pointing in the same directions, providing evidence of not only replication but also triangulation (44), thereby strengthening confidence in our findings.

Latent class analysis and group-based trajectory models have been extensively applied to longitudinal data of single allergic diseases (45–50). In the current analysis, we used LMM. A key difference is that in the latent class analysis models every subject remains in the same latent class across time, whereas in LMM subjects can transition between latent states, thereby allowing for phenotypic instability over time. An advantage of this approach is that it allows the time dependency between successive multivariate observations to be estimated. More specifically, we could observe whether the presence of one disorder increases the probability of developing (or transitioning) to others. Our results were obtained under the first-order Markov assumption, which states that the future state is independent of the historical events given the current state. This assumption could be relaxed by adopting a higher-order Markov chain, thereby allowing the conditional independence to include more time lags. However, over-parametrizing the transition probabilities increases the complexity and affects the interpretability of the final model.

The observation of cooccurrence does not imply any specific causal relationship (in particular in relation to sensitization, as almost one-third of individuals with E+W+R multimorbidity were not sensitized). Association of nonatopic multimorbidity with maternal eczema, and a trend toward higher frequency of maternal smoking, suggest the potential importance of skin barrier and specific environmental exposures in nonatopic triad. However, caution is required when interpreting these findings, because in the stratified analysis, the sample size was relatively low. The relationship between multimorbidity and sensitization warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, our findings confirm that eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis are not independent from each other, but there is no specific or typical sequence of symptom development that characterizes multimorbidity. Overall, ∼50% of children have at least one of these symptoms, but only ∼4–6% have multimorbidity that does not arise as a chance cooccurrence. We found no evidence of a sequential atopic march progression. The early comorbidities increase the risk of future persistent multimorbidity; hence, early-life diseases should be examined (both clinically and epidemiologically) in the context of the cooccurrence of other conditions. We suggest that physicians should inquire about different atopic disorders if a child presents with one but should not make recommendations about ways to prevent atopic march or inform parents that children with eczema may later develop asthma. The term atopic march should not be used to describe atopic multimorbidity, and we should reform the taxonomy of atopic diseases from traditional symptom-based criteria toward a mechanism-based framework. However, for this change to be meaningful, the current symptom-based diagnoses will have to be surpassed by understanding of disease mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

STELAR/UNICORN investigators: Professor John Ainsworth, School of Health Sciences, The University of Manchester; Dr. Andrew Boyd, University of Bristol; Professor Andrew Bush, NHLI, Imperial College London; Dr. Philip Couch, School of Health Sciences, The University of Manchester; Professor Graham Devereux, Clinical Sciences, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Liverpool; Dr. Ibrahim Emam, Department of Computing, Imperial College London; Professor Yi-ke Guo, Department of Computing, Imperial College London; Professor Sejal Saglani, NHLI, Imperial College London; Professor Ashley Woodcock, University of Manchester.

Footnotes

A complete list of STELAR/UNICORN investigators may be found before the beginning of the References.

Supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) Programme grant MR/S025340/1 (UNICORN consortium); MRC grants G0601361 and MR/K002449/1 (STELAR consortium); Wellcome Trust Strategic Award 108818/15/Z (R.G.); Asthma UK grants no. 301 (1995–1998), 362 (1998–2001), 01/012 (2001–2004), and 04/014 (2004–2007) (MAAS); BMA James Trust (2005), the JP Moulton Charitable Foundation (2004–2016), The North West Lung Centre Charity (1997–current), and MRC grant MR/L012693/1 (2014–2018) (MAAS); and the Isle of Wight Health Authority, the National Asthma Campaign, UK grant no. 364, and NIH grants R01 HL082925-01, R01 AI091905, and R01 AI121226 (IOW).

Author Contributions: A.C., A.S., S.H., and S.F. conceived and planned the study and wrote the manuscript. S.H., S.F., and G.H. analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript. A.S. and C.S.M. are supported by the National Institute for Health Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202110-2418OC on June 9, 2022

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

Contributor Information

on behalf of the STELAR/UNICORN investigators:

John Ainsworth, Andrew Boyd, Philip Couch, Graham Devereux, Ibrahim Emam, Yi-ke Guo, Sejal Saglani, and Ashley Woodcock

References

- 1. Moreno MA. JAMA pediatrics patient page: atopic diseases in children. JAMA Pediatr . 2016;170:96. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Custovic A, Custovic D, Kljaić Bukvić B, Fontanella S, Haider S. Atopic phenotypes and their implication in the atopic march. Expert Rev Clin Immunol . 2020;16:873–881. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2020.1816825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Custovic A, Henderson J, Simpson A. Does understanding endotypes translate to better asthma management options for all? J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2019;144:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Akar-Ghibril N, Casale T, Custovic A, Phipatanakul W. Allergic endotypes and phenotypes of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract . 2020;8:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Silverberg JI. Comorbidities and the impact of atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol . 2019;123:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spergel JM. From atopic dermatitis to asthma: the atopic march. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol . 2010;105:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bantz SK, Zhu Z, Zheng T. The Atopic march: progression from atopic dermatitis to allergic rhinitis and asthma. J Clin Cell Immunol . 2014;5:202. doi: 10.4172/2155-9899.1000202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Munidasa D, Lloyd-Lavery A, Burge S, McPherson T. What should general practice trainees learn about atopic eczema? J Clin Med . 2015;4:360–368. doi: 10.3390/jcm4020360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Warner JO, ETAC Study Group. Early Treatment of the Atopic Child A double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of cetirizine in preventing the onset of asthma in children with atopic dermatitis: 18 months’ treatment and 18 months’ posttreatment follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2001;108:929–937. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.120015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schneider L, Hanifin J, Boguniewicz M, Eichenfield LF, Spergel JM, Dakovic R, et al. Study of the atopic march: development of atopic comorbidities. Pediatr Dermatol . 2016;33:388–398. doi: 10.1111/pde.12867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Williams H, Flohr C. How epidemiology has challenged 3 prevailing concepts about atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2006;118:209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barberio G, Pajno GB, Vita D, Caminiti L, Canonica GW, Passalacqua G. Does a ‘reverse’ atopic march exist? Allergy . 2008;63:1630–1632. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Nickel R, Grüber C, Niggemann B, et al. Multicenter Allergy Study Group The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2004;113:925–931. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.01.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hopper JL, Bui QM, Erbas B, Matheson MC, Gurrin LC, Burgess JA, et al. Does eczema in infancy cause hay fever, asthma, or both in childhood? Insights from a novel regression model of sibling data. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2012;130:1117–1122.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Belgrave DC, Granell R, Simpson A, Guiver J, Bishop C, Buchan I, et al. Developmental profiles of eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis: two population-based birth cohort studies. PLoS Med . 2014;11:e1001748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clark H, Granell R, Curtin JA, Belgrave D, Simpson A, Murray C, et al. Differential associations of allergic disease genetic variants with developmental profiles of eczema, wheeze and rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy . 2019;49:1475–1486. doi: 10.1111/cea.13485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pinart M, Benet M, Annesi-Maesano I, von Berg A, Berdel D, Carlsen KC, et al. Comorbidity of eczema, rhinitis, and asthma in IgE-sensitised and non-IgE-sensitised children in MeDALL: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Respir Med . 2014;2:131–140. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ballardini N, Kull I, Lind T, Hallner E, Almqvist C, Ostblom E, et al. Development and comorbidity of eczema, asthma and rhinitis to age 12: data from the BAMSE birth cohort. Allergy . 2012;67:537–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spergel JM. The atopic march: where we are going? Can we change it? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol . 2021;127:283–284. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2021.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Paller AS, Spergel JM, Mina-Osorio P, Irvine AD. The atopic march and atopic multimorbidity: many trajectories, many pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2019;143:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Melen E, Himes BE, Brehm JM, Boutaoui N, Klanderman BJ, Sylvia JS, et al. Analyses of shared genetic factors between asthma and obesity in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2010;126:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cullinan P, MacNeill SJ, Harris JM, Moffat S, White C, Mills P, et al. Early allergen exposure, skin prick responses, and atopic wheeze at age 5 in English children: a cohort study. Thorax . 2004;59:855–861. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arshad SH, Holloway JW, Karmaus W, Zhang H, Ewart S, Mansfield L, et al. Cohort profile: the Isle of Wight Whole Population Birth Cohort (IOWBC) Int J Epidemiol . 2018;47:1043–1044i. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Custovic A, Simpson BM, Murray CS, Lowe L, Woodcock A, NAC Manchester Asthma and Allergy Study Group The National Asthma Campaign Manchester Asthma and Allergy Study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol . 2002;13:32–37. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3038.13.s.15.3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martindale S, McNeill G, Devereux G, Campbell D, Russell G, Seaton A. Antioxidant intake in pregnancy in relation to wheeze and eczema in the first two years of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2005;171:121–128. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-220OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Custovic A, Ainsworth J, Arshad H, Bishop C, Buchan I, Cullinan P, et al. The Study Team for Early Life Asthma Research (STELAR) consortium ‘Asthma e-lab’: team science bringing data, methods and investigators together. Thorax . 2015;70:799–801. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Palmer CN, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Zhao Y, Liao H, Lee SP, et al. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet . 2006;38:441–446. doi: 10.1038/ng1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartolucci F, Farcomeni A, Pennoni F. Latent Markov models for longitudinal data. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Langeheine R, Van de Pol F. A unifying framework for Markov modeling in discrete space and discrete time. Sociol Methods Res . 1990;18:416–441. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bartolucci F, Pandolfi S, Pennoni F. LMest: an R package for latent Markov models for longitudinal categorical data. J Stat Softw . 2017;81:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gabadinho A, Ritschard G, Müller NS, Studer M. Analyzing and visualizing state sequences in R with TraMineR. J Stat Softw . 2011;40:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nicholson K, Makovski TT, Griffith LE, Raina P, Stranges S, van den Akker M. Multimorbidity and comorbidity revisited: refining the concepts for international health research. J Clin Epidemiol . 2019;105:142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marenholz I, Esparza-Gordillo J, Rüschendorf F, Bauerfeind A, Strachan DP, Spycher BD, et al. Meta-analysis identifies seven susceptibility loci involved in the atopic march. Nat Commun . 2015;6:8804. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakamura T, Haider S, Colicino S, Murray CS, Holloway J, Simpson A, et al. STELAR investigators Different definitions of atopic dermatitis: impact on prevalence estimates and associated risk factors. Br J Dermatol . 2019;181:1272–1279. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Frainay C, Pitarch Y, Filippi S, Evangelou M, Custovic A. Atopic dermatitis or eczema? Consequences of ambiguity in disease name for biomedical literature mining. Clin Exp Allergy . 2021;51:1185–1194. doi: 10.1111/cea.13981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Margolis DJ, Mitra N, Wubbenhorst B, D’Andrea K, Kraya AA, Hoffstad O, et al. Association of filaggrin loss-of-function variants with race in children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol . 2019;155:1269–1276. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nicolaou N, Poorafshar M, Murray C, Simpson A, Winell H, Kerry G, et al. Allergy or tolerance in children sensitized to peanut: prevalence and differentiation using component-resolved diagnostics. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2010;125:191–197.e1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nicolaou N, Murray C, Belgrave D, Poorafshar M, Simpson A, Custovic A. Quantification of specific IgE to whole peanut extract and peanut components in prediction of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2011;127:684–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brough HA, Simpson A, Makinson K, Hankinson J, Brown S, Douiri A, et al. Peanut allergy: effect of environmental peanut exposure in children with filaggrin loss-of-function mutations. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2014;134:867–875.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nakamura T, Haider S, Fontanella S, Murray CS, Simpson A, Custovic A. Modelling trajectories of parentally reported and physician-confirmed atopic dermatitis in a birth cohort study. Br J Dermatol . 2022;186:274–284. doi: 10.1111/bjd.20767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Haider S, Granell R, Curtin J, Fontanella S, Cucco A, Turner S, et al. Modeling wheezing spells identifies phenotypes with different outcomes and genetic associates. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2022;205:883–893. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202108-1821OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Saglani S, Cohen RT, Chiel LE, Halayko AJ, Pascoe CD, Custovic A. Update in asthma 2021. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2022 doi: 10.1164/rccm.202203-0439UP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Robinson PFM, Fontanella S, Ananth S, Martin Alonso A, Cook J, Kaya-de Vries D, et al. Recurrent severe preschool wheeze: from prespecified diagnostic labels to underlying endotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2021;204:523–535. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202009-3696OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lawlor DA, Tilling K, Davey Smith G. Triangulation in aetiological epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol . 2016;45:1866–1886. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Deliu M, Belgrave D, Sperrin M, Buchan I, Custovic A. Asthma phenotypes in childhood. Expert Rev Clin Immunol . 2017;13:705–713. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2017.1257940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mulick AR, Mansfield KE, Silverwood RJ, Budu-Aggrey A, Roberts A, Custovic A, et al. Four childhood atopic dermatitis subtypes identified from trajectory and severity of disease and internally validated in a large UK birth cohort. Br J Dermatol . 2021;185:526–536. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Oksel C, Granell R, Haider S, Fontanella S, Simpson A, Turner S, et al. STELAR investigators; Breathing Together investigators Distinguishing wheezing phenotypes from infancy to adolescence: a pooled analysis of five birth cohorts. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2019;16:868–876. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201811-837OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Oksel C, Granell R, Mahmoud O, Custovic A, Henderson AJ, STELAR; Breathing Together Investigators Causes of variability in latent phenotypes of childhood wheeze. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2019;143:1783–1790.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Paternoster L, Savenije OEM, Heron J, Evans DM, Vonk JM, Brunekreef B, et al. Identification of atopic dermatitis subgroups in children from 2 longitudinal birth cohorts. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2018;141:964–971. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roduit C, Frei R, Depner M, Karvonen AM, Renz H, Braun-Fahrländer C, et al. the PASTURE study group Phenotypes of atopic dermatitis depending on the timing of onset and progression in childhood. JAMA Pediatr . 2017;171:655–662. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]