Abstract

Background

Recent data have shown high rates of opioid misuse among inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. We conducted a qualitative study to explore IBD patient and provider perceptions and experiences with pain management and opioid prescribing.

Methods

We conducted a focus group with IBD patients and semistructured interviews with IBD-focused physicians and nurses. We used an inductive approach for analysis and the constant comparison method to develop and refine codes and identify prominent themes. We analyzed interview and focus group data concurrently to triangulate themes.

Results

Nine patients and 10 providers participated. We grouped themes into 3 categories: (1) current practices to manage pain; (2) perceived pain management challenges; and (3) suggestions to optimize pain management. In the first category (current practices), both patients and providers reported building long-term patient–provider relationships and the importance of exploring nonpharmacologic pain management strategies. Patients reported proactively trying remedies infrequently recommended by IBD providers. In the second category (pain management challenges), patients and providers reported concerns about opioid use and having limited options to treat pain safely. Patients discussed chronic pain and having few solutions to manage it. In the third category, providers shared suggestions for improvement such as increasing use of nonpharmacologic pain management strategies and enhancing care coordination.

Conclusions

Despite some common themes between the 2 groups, we identified some pain management needs (eg, addressing chronic pain) that matter to patients but were seldom discussed by IBD providers. Addressing these areas of potential disconnect is essential to optimize pain management safety in IBD care.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel diseases, pain management, opioid analgesics, health services research, qualitative research methods

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, are characterized by chronic, relapsing inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.1 These diseases affect over 3 million individuals in the United States2 and their incidence continues to rise.3 Across the continuum of IBD care, pain is a frequently reported symptom among patients. Up to 70% of IBD patients experiencing the initial onset or exacerbations of active disease as well as up to 50% of patients in clinical remission present with pain.4 Estimates suggest that pain and other related symptoms associated with IBD account for over a billion dollars annually in healthcare costs and lost workplace productivity.5,6 In addition to this economic burden, pain—as well as the fear of pain—is linked with significant detrimental effects on quality of life and health outcomes among IBD patients.7,8 Today, the impact of pain in IBD possibly extends far beyond cost and quality of life given that pain management with opioid analgesics carries a higher morbidity and mortality risk9,10 and because IBD patients may be disproportionately affected by the ongoing national opioid epidemic.11,12 It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation (CCF) in 2019 highlighted the need to optimize pain management and reduce opioid use in IBD care among its most pressing clinical research priorities.13

To date, studies contributing toward these priorities have been, predominantly, large quantitative analyses examining the deleterious effects of opioids and opioid use patterns in the IBD population. From this evidence base, it is clear that potentially unsafe opioid use—such as chronic use—is a significant problem in IBD care14 and is associated with an increased risk of addiction, death, and higher healthcare costs.15–18 Prior studies have also shown that opioid use during an IBD flare is linked with an increased likelihood of chronic opioid use, particularly among younger IBD patients and those with common comorbid conditions such as depression or functional GI disorders.19–21 This is especially concerning given that chronic opioid use is not associated with improvements in either abdominal pain or quality of life scores22 and, instead, is tied to poorer IBD outcomes and a broad range of serious potential harms including bowel dysfunction.23–26 Analyses of administrative databases have also established that diagnoses related to opioid use disorders are increasing among IBD patients and may be linked with longer lengths of hospital stays.27

These studies present important insights. They also inform many residual questions about current pain management practices, existing challenges, and ways to identify an actionable path forward. For example: What are providers’ current practices to manage pain and patient safety among their IBD patients, particularly in the presence of comorbid conditions? How do patients perceive their own pain management needs and to what extent are those needs met? What are the underlying factors that contribute to opioid use in IBD care? And what practical, evidence-based steps can patients and providers take to manage pain safely and effectively in IBD? Qualitative research—methods specifically designed to understand not just “how often,” but also “why” and “how” a phenomenon occurs—has been a persistent gap in the current IBD literature focused on pain management and opioid use. Few prior qualitative studies have been conducted in this area, and, to our knowledge, these have been limited to exploring the experience of pain among patients with IBD.28,29 To address this gap, we conducted a qualitative study to explore patient and provider perceptions and experiences related to pain management needs and opioid prescribing in IBD care.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

We conducted an in-depth focus group with IBD patients and semistructured interviews with IBD-focused physicians and nurses from the IBD program at the Digestive Health Center (DHC) at Northwestern Medicine. We used the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guideline to report key study details.30

Patients who were eligible to participate in the focus group were characterized as (1) being 18 years of age or older; (2) previously diagnosed with IBD; and (3) having at least 1 clinic visit with a gastroenterologist in the DHC in the 12 months preceding the focus group. Patients who met eligibility criteria were contacted by e-mail and invited to participate in the study. All providers who cared for patients with IBD at the DHC (including gastroenterologists, nurses, and nurse practitioners) were invited to participate in individual semistructured interviews.

Data Collection

We conducted the focus group with patients using video-based conferencing in April 2021. Two study team members (S.B. and C.I.) facilitated the 90-minute focus group using a focus group moderator guide (Appendix A). The focus group guide was developed after a review of relevant literature on pain management and opioid use in the IBD patient population and with input from the study team members, all of whom have experience with qualitative methods and research focused on opioid safety and pain. Questions focused on gaining insights from patients about their pain management needs, experiences with opioid use, and potential nonopioid pain management approaches. We also asked about patients’ concerns about opioid use. All patient participants completed a questionnaire to obtain basic demographic information (eg, age, sex, IBD diagnosis).

We conducted 30- to 60-minute individual semistructured interviews with participating providers. One study team member (S.B.), with prior training in qualitative interviewing and input from the remaining team members with qualitative expertise, conducted the interviews between March and April 2021, using telephone and video-based conferencing. A semistructured interview guide focused on providers’ decision-making processes as they relate to managing pain and prescribing opioid analgesics, as well as the factors that shape their decision-making. Additionally, we focused on providers’ clinical practices, potential challenges they perceived in managing pain among the IBD patients they care for, and suggestions for improvement (Appendix B). We used the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which has been used in prior qualitative studies focused on pain management,31 to inform the interview guide. This framework helps to explain how attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived control can interact to influence providers’ intentions and behavior surrounding pain management and opioid prescribing. Attitudes, in this framework, reflect knowledge, experiences, and information sources; subjective norms are shaped by an individual’s social environment; and perceived behavioral control is affected by perceptions of an individual’s ability to perform a given behavior or access specific services in a particular setting.32,33

Data Analysis

Transcripts were audio recorded, professionally transcribed verbatim, and prepared by the research team for analysis. Coding was conducted by 2 study team members trained in qualitative data analysis (S.B. and C.I.) with input from 2 additional team members (W.S. and J.J.) across multiple rounds to identify emerging themes. We used an inductive coding approach for analysis and the constant comparison method to compare data from an initial group of transcripts and generate a preliminary patient and provider codebook.34,35 The 2 coders independently coded all transcripts, compared codes, and then, collaboratively, refined the codebooks and code definitions. The final codebooks (Appendices C and D) were applied to the remaining transcripts. Discrepancies were reconciled through consensus.36 Coded transcripts were analyzed within and across cases to develop themes. Focus group and interview data were analyzed concurrently to triangulate data. We used the MAXQDA software package (Version 2020, VERBI Software GmbH) to support data storage, coding, and analysis.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the institutional review board at Northwestern University and all participants provided verbal consent (IRB#: STU00213896). For their participation, focus group participants each received a $50 gift card and interview participants each received a $10 gift card.

Results

In total, 9 patients and 10 providers participated in the study. Patients were, on average, 40 years old, predominantly female (78%), and mostly diagnosed with Crohn’s disease (78%). Patients’ mean age at the time of IBD diagnosis was approximately 22 years and over half (56%) had undergone IBD surgery previously. Nearly all patients (89%) were taking 1 or more medications to manage their IBD at the time of the focus group. Among these medications, biologic therapy was the most frequently used with 67% of patients reporting current use. Providers included 5 gastroenterologists, 3 nurses, and 2 nurse practitioners, all of whom focused on IBD clinical care. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Emerging themes related to pain management were grouped into 3 broad categories: (1) current practices surrounding pain management; (2) concerns, needs, and experiences related to pain management challenges in IBD care; and (3) suggestions to optimize the delivery and safety of pain management in IBD care. Emerging themes, and whether they were reported by patients, providers, or both, are denoted in bolded text in this section.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Mean ± SD or frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Patients (N = 9) | |

| Age | 39.8 ± 14.9 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 7 (77.8) |

| Male | 2 (22.2) |

| IBD diagnosis | |

| Crohn’s disease | 7 (77.8) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2 (22.2) |

| Age at IBD diagnosis | 21.8 ± 9.6 |

| Had prior surgery to treat IBD (% yes) | 5 (55.6) |

| Current IBD medications | |

| Biologic therapy | 6 (66.7) |

| Immunomodulator | 4 (44.4) |

| 5-ASA | 2 (22.2) |

| None | 1 (1.1) |

| Providers (N = 10) | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 3 (30) |

| Female | 7 (70) |

| Profession | |

| Physician | 5 (50) |

| Nurse | 3 (30) |

| Nurse practitioner | 2 (20) |

Abbreviation: 5-ASA, aminosalicylates; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Category 1 Themes: Current Practices Surrounding Pain Management

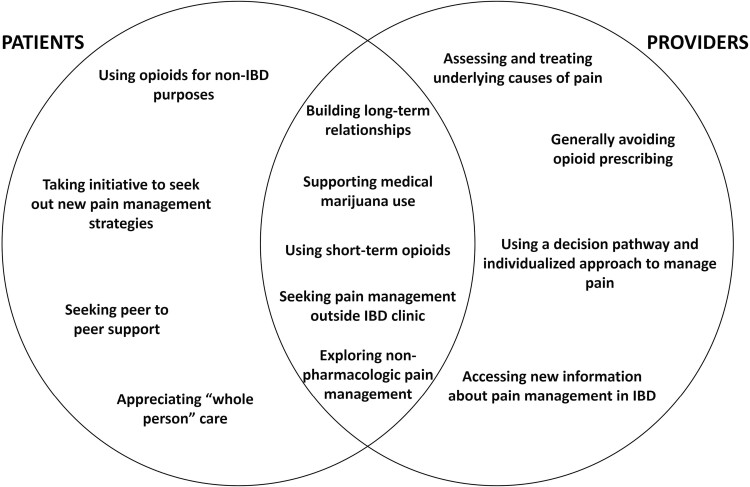

We identified several themes that describe patients’ and providers’ current practices surrounding pain management. Figure 1 presents these themes according to the group(s) that reported them (patients, providers, or both). Table 2 includes representative quotes related to each theme.

Figure 1.

Category 1 themes: current practices surrounding pain management, reported by patients, providers, or both.

Table 2.

Current practices surrounding pain management, stratified by group.

| Theme | Representative quote | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Providers | ||

| Reported by providers and patients | Building long-term relationships and trust | “Last week I called the office and said, ‘Hey, I need to talk to [the IBD nurse]. I have questions.’ Two days later, [the nurse] called me. And I hadn’t talked to her in six months, but we have that whole rapport and I think that’s huge because what we’re dealing with, for lack of a better word is, shitty, you know. That’s just what it is and it’s important for me and my team that everybody is all in and… supportive.” [Patient] | “I wish I could take away their pain. But the good thing about my role is having these long-term relationships with patients, so I really do know them, and they trust me. And so, explaining to them why we can’t prescribe them certain medications and talking about other like safe alternatives or things they can do in the meantime and knowing that it’s not long-term. Once we heal their IBD, their pain will go away. So re-circling to that, on focusing on treating their disease… which will subsequently treat their pain.” [Nurse] |

| “I feel like you have to explain to the patient and get the buy-in. Because these are our chronic patients, so it’s not like the ER where you’re like, give them narcotics, they’ll go disappear. So we have this ongoing relationship with our patients. So it’s establishing that track. Because if you give them narcotics once, you’re setting the stage for yourself, I think, in the future to always … this is what you did, why won’t you give it to me again? Setting the premise before.” [Physician] | |||

| Using short-term opioids to get through an acute flare | “When I was in my flare prior to my surgery I was three weeks from graduating college, so, of course, while you’re in that, it’s stressful as it is, so I was put on Percocet and a steroid as well.” [Patient] | “In general, we try to treat the underlying reason rather than give pain medication, although certainly, some pain medication might be required temporarily.” [Physician] | |

| Seeking pain management help outside of IBD clinic | “For me, the [GI Pysch] Behavioral Department was a godsend. The breathing exercises, I think, helped my pain the most. I would say almost every day in my life now. Or, if I’m sitting in the car and I really have to go to the bathroom and I know I have 10 more minutes before I’m going to make it home, that can calm me down. Those exercises are amazing.” [Patient] | “A couple of these patients, we’ve had to refer them to pain management clinic to try to get them some more resources and more help beyond what we’re able to give them. So, it’s just I think realizing that there’s only so much that we can do for some people, and that we need to obviously look for other resources in collaboration with people who might be better suited to help them.” [Nurse] | |

| Exploring nonpharmacologic pain management strategies | “I’ve spent many years addressing my diet and lifestyle and even where I live to try and get on top of this sort of chronic pain. The diet over the years, I’ve taken out gluten and dairy and processed foods just because it didn’t sit well with me, not sort of intentionally, and gotten to a diet where I don’t really have a lot of GI pain anymore, but my diet’s very restricted and I have a very controlled lifestyle. I have a luxury of being able to control a lot of my lifestyle, so that’s been helpful, I guess.” [Patient] | “If a patient comes in with pain from Crohn’s disease in the hospital, just taking them off food will eliminate the pain. So they may need an immediate relief, but when they’re not eating they shouldn’t have pain. If they have pain when they are not eating, there’s an abscess there or a cancer or a blockage there. Okay? So, that’s a pretty simple thing. I’ll take them off food for a little bit, treat the inflammation, whether it’s drain the abscess or start them on steroids to control the inflammation. And then I don’t start them feeding again until they’re in no pain. If they have pain, they got to reduce their diet.” [Physician] | |

| Supporting and using medical marijuana | “I experimented trying marijuana from people because that was all I could really get by since I was just a high school student. It’s just that wasn’t covered for colitis. I don’t think it, at least for me, truly would help with the pain, it was just a distraction from the pain.” [Patient] | “I write plenty of marijuana cards… Not day-to-day, but on a month-to-month basis. So I think that if marijuana treats their underlying GI symptoms, including pain, and I talked to them about my expectations if they’re going to use marijuana, then I’m certainly fine with them using it. I’d much rather them use that than narcotics.” [Physician] | |

| Reported by providers only | Generally avoiding opioid prescribing | “I’m not ignoring their pain, and I’m not trying to get a work around to all this, I simply don’t believe that narcotics are the answer for pretty much anything, and so I don’t prescribe them or do I want others to prescribe narcotics for them. So, I’m very open with my patients about it. And I think if you ask some of my patients with pain I’d be curious to see what they say about me as their provider, but at the same time, I tell people that if there’s danger to these medications. At least my impression of myself it’s not like I say no and ignore their pain. That’s not what I try to do. Again, I’d be curious to hear what my patients say about this, but I’m certainly not quick to brush off their pain with a prescription pad.” [Physician] | |

| Assessing and treating underlying causes of disease | “The first assessment needs to be made in terms of where their pain is, and what’s driving their pain and if their pain is inflammatory bowel disease related, or if it’s related to something else. That’s really where you have to start in terms of pain within our IBD population. Certainly if the pain is obstruction from strictures and Crohn’s disease, or if it’s pain within their lower abdomen because they’ve got ulcerative colitis and it’s inflammation within their colon that’s driving their pain, then that usually will depend upon what we do for that pain. Because if the pain is deriving from inflammation, then treating the inflammation is what we have to do.” [Physician] | ||

| Using a decision pathway and an individualized approach to manage pain | “Usually when a patient presents in clinic with, if I think it’s a flare, there may be some diagnostic workup, rule out infections or other things that we do, but … And then we, in terms of basic things for pain management, most of us start with Tylenol. You can take up to four grams a day. If that doesn’t work, then we are comfortable in prescribing tramadol, Ultram, but usually that’s after the diagnostic workup. Unless they’re in significant pain, because if they’re in really significant pain and they have Crohn’s, you have to figure out what’s really going on. Because their disease shouldn’t be causing that significant pain. And if it is, then they probably need to be in the hospital.” [Physician] | ||

| Accessing new information about pain management in IBD | “Ways I keep up with, up to date, on new information in the world of IBD is on Twitter. There’s a huge Twitter presence of IBD providers across the nation. Um, and so constantly sharing new research articles and new information to guide our practice. So, that, and then, you know, other, using PubMed with other research articles and journals.” [Nurse Practitioner] | ||

| Reported by patients only | Seeking peer to peer support | “I’ve met lovely people in [the support group]. Even though all of our stories are different and we’re all experiencing different things, man, it is so reassuring and such a great piece of mind to know that if I have to go into the hospital for something, I could call one of them and be like, ‘Hey, have any of you guys experienced this? What’s going on?’ So, that group has been very helpful because I know we’re not the only ones here.” [Patient] | |

| Using opioids for non-IBD purposes | “I had said before that the pain medicine didn’t actually help with my IBD cramping pain. I was given them and you know, at the same time, you’re on prednisone, you can’t sleep. So, actually, I would sometimes take them to help me sleep which is a slippery slope… I luckily never got addicted, and I kept it under control and all that, but I’m sure other people have done that and how it can result in addiction and we’re using it in ways that aren’t intended. So, that was my experience with the opioids.” [Patient] | ||

| Taking initiatives to seek out new pain management strategies | “I’ve also found a lot of relief in Epsom salt and Epsom salt baths and literally just laying in warm water and just laying there and it’s very relaxing. It’s been great for me.” [Patient] | ||

| Appreciating “whole-person” care | “The biggest thing for me is when I met my doctor for the first time, she’s like, I know you’re overwhelmed and she gave me a hug. She treated me like a person and I’ve had other physicians where I left there in tears with my mom because they didn’t believe the pain that I had and it was reassuring to me that this person cared, legitimately cared. So, it’s reassuring to me.” [Patient] | ||

Abbreviation: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Reported by patients and providers

Both patients and providers reported that building long-term patient–provider relationships and trust was an important component of IBD care and a step that they took in their respective role as patient or provider. These long-term relationships would sometimes play a role in their decision-making about how to address pain. For example, 1 nurse commented that, because of her long-standing relationships with IBD patients, she may know if a patient experiencing pain has a history of prior depression or drug or alcohol abuse. In this case, the nurse stated that knowledge of such risk factors, in turn, would guide subsequent conversations with the patient, in which the nurse would try to clearly communicate the potential harms of opioid use while showing compassion and sensitivity to the patient’s history. The use of short-term opioids to get through an acute flare was also reported by both groups. Patients reported that these opioid prescriptions included codeine, hydrocodone, morphine, oxycodone, and tramadol. Physicians reported that while they generally avoid prescribing opioids, they will prescribe short-term pain medications to manage acute episodes. Beyond these short-term opioid prescriptions, both groups reported occasionally seeking pain management help outside of the IBD clinic (including referrals to pain management specialists). This included, for example, patients seeking out support from GI-focused psychologists if they felt their pain was not fully addressed by their IBD providers. It also included IBD providers, who reported that they occasionally felt the need to refer patients to pain management specialists if the patient had longer-term pain issues. Both groups also shared the belief that it was important to explore nonpharmacologic pain management strategies, such as modifying diet and using acupuncture, to minimize patients’ pain, although most providers noted that they currently do not routinely implement these strategies in their clinical practice. Both groups indicated that they supported the use of medical marijuana as a complementary treatment in IBD care. Providers supported and patients felt comfortable using medical marijuana, although providers acknowledged that there are limited data documenting the benefits of medical marijuana in reducing inflammation and patients expressed concern over marijuana use.

Reported by providers only

Although they acknowledged that short-term opioids were often needed for patients to get through an acute flare, providers stated that they generally avoid prescribing opioids to IBD patients due to the specific risks these pose to the GI system. All providers stated that they focus on assessing and treating underlying causes of pain using a data-driven approach as they consider potential pain management needs. They discussed wanting to identify the physiologic cause of the pain (eg, inflammation or strictures) and treat the underlying disease, rather than just treating the pain. They then often used a decision pathway to individualize pain management, using imaging or other testing to characterize the causes of pain. They also described caring for patients with IBD with a team-based approach, soliciting input and collaboration from providers with different expertise. Providers commented, for example, on informal initiatives they had implemented to minimize potential opioid exposure among IBD patients who receive emergency department (ED) care services for IBD. One initiative included providing an informational card to patients to share with ED providers, letting those providers know that both opioid and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use is generally not recommended for IBD patients. Finally, providers reported that they continually sought out new knowledge about pain management in IBD by reading scientific medical journals, attending conferences, and participating on digital platforms, such as Twitter, to ensure they were up-to-date on the most recent research and guidance.

Reported by patients only

Several patients described the benefits they derived from peer-level support through IBD patient support groups. Throughout the focus group, patients related with one another and thanked each other for sharing their stories. A few patients described prior experiences using opioid prescriptions for non-IBD purposes (eg, to fall asleep), in some cases, despite their knowledge of the potential harms of opioid use. And although both patients and providers agreed on the importance of exploring nonpharmacologic pain management strategies, we found that, most often, patients alone described taking the initiative to proactively try out different nonpharmacologic pain management strategies, that were often not discussed by their IBD provider, to address their pain. These included seeing a physical therapist, chiropractor, making lifestyle changes such as diet modifications, doing deep breathing exercises, and using Epsom bath salts and heating pads. Patients described a much wider array of nonpharmacologic pain management solutions than providers did. Patients also described that they appreciated providers’ efforts to care for them as a “whole person,” including showing compassion toward patients, actively listening, and acknowledging both IBD and non-IBD struggles (as opposed to simply treating their IBD) throughout the continuum of their care.

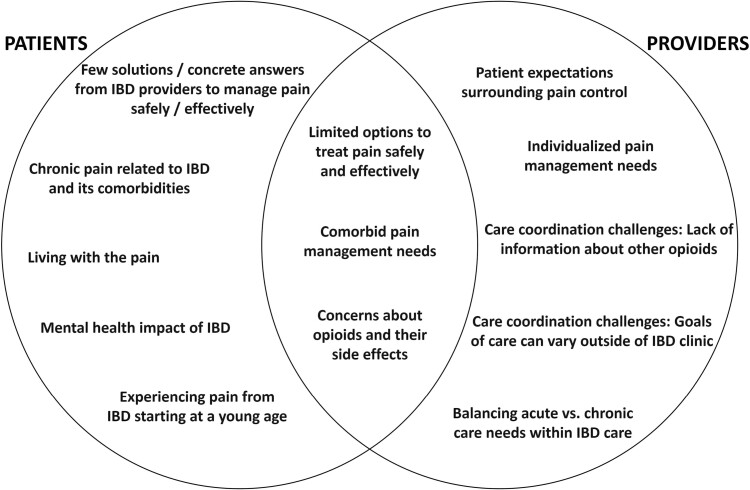

Category 2 Themes: Challenges Related to IBD Pain Management

We identified several themes that reflect the concerns, needs, and experiences of patients and providers related to pain management challenges in IBD care. Figure 2 presents these themes according to the group(s) that reported them (patients, providers, or both). Table 3 includes representative quotes related to each theme.

Figure 2.

Category 2 themes: challenges related to IBD pain management, reported by patients, providers, or both. Abbreviation: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Table 3.

Challenges related to IBD pain management, stratified by group.

| Theme | Representative quote | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Providers | ||

| Reported by providers and patients | Limited options to treat pain safely and effectively | “There aren’t a lot of pain medications that we can take. I can’t take Ibuprofen or Aspirin. Even Tylenol isn’t recommended based on what [my doctor] says for daily aches and pains. And so that doesn’t leave a lot that’s over the counter that would be safe, even.” [Patient] | “We tend to steer clear of opioids because they can actually make things worse. And [IBD patients] cannot take NSAIDs. So, for pain, we’re kind of limited in what we can prescribe, but so we usually stick with Tylenol.” [Nurse] |

| Comorbid pain management needs | “I’ve had a lot of muscular skeletal pain over the years… associated with joint swelling and stiffness. I got to a point a few years ago where I was frantic with this sort of daily pain and fatigue. I’ve had a lot of imaging and scans. They found inflammation in my side joint, but nothing concrete and offered me a heavy immunosuppressant like Enbrel. But I didn’t have something pathologically threatening to my muscular skeletal system and I didn’t have active inflammation for Crohn’s and so it felt like I was only considering it for symptoms of quality of life which is such a difficult call for patients with chronic illness… because you just don’t know when that breaking point is and you don’t want to go on something you can’t get off.” [Patient] | “I mean, even [having] a kidney stone is an acute pain but it’s treated with opioids appropriately short-term. Sometimes even the extraintestinal manifestations such as the arthritis may require opioid management.” [Physician] | |

| Concerns about opioids and their side effects | “The other side of the [opioid] pills was I would get vicious dreams. I didn’t like that side of it because it is kind of scary when you necessarily don’t feel like you have control over your body anyway at that point, just because you’re just waiting for whatever the next option may be whether that’s surgery or whatever the case is.” [Patient] | “One of the main reasons that we don’t give anything stronger is because it does mask the flare and yes, we don’t want our patients in pain but we don’t want to make things worse. Opioids slow gut motility and can cause constipation and a whole slew of other problems.” [Nurse] | |

| Reported by providers only | Patient expectations surrounding pain control | “Unfortunately, I feel like society feels like if you throw a pain pill at them and they, they want it fixed right away. And not always, I mean, it’s definitely not our approach. So you have to have more of an in-depth conversation with them about different options to treat pain. It’s a process for sure. And sometimes it’s a little trial and error in different things they may never have tried before, and it’s educating them on those different types of therapies. It’s just shifting the mindset.” [Nurse Practitioner] | |

| Individualized pain management needs | “It seems to be so different from one patient to the next patient, whether it’s their disease course, and they’ve had it for 50 years, and they’re doing relatively fine or they’ve had it for five years, and they have a really bad disease progression.” [Nurse practitioner] | ||

| Care coordination challenges: Lack of information about other opioid prescriptions | “That’s definitely a gap. I know we’ve used the [opioid] prescriber database in the past. It’s not something that we use necessarily all the time just to track prescriptions. For our patients where we’re more concerned about opioid use, we’ve looked before, but, it’s not something that’s in our workflow. There’s definitely opportunity for us to be missing things. Especially, if you consider where patients might be getting treated for different kinds of pain. I don’t have access to Shirley Ryan’s records if they’re going there for anything. Or, Rush is great for ortho, I’m not necessarily getting all that information. [That information] could be extremely beneficial.” [Nurse] | ||

| Care coordination challenges: Goals of care can vary outside of IBD clinic (eg, emergency department) | “We’re all very often subverted in [opioid stewardship]. We’re subverted by patients who are going to other doctors who are getting pain narcotics. We’re subverted by emergency rooms. Two things happen in an emergency room, Dilaudid and a CT scan. That’s what happens. So, I think that we’re not by any means the only influence here. Makes it very challenging because number one, they have an easier access to opioids than through us and that reinforces that behavior. And it subverts our ability to intervene on a longer-term basis because patients can just come in and get their hit and get admitted. And every one of our orders, every one of our requests to the emergency room and to the hospitalists on the floor are ‘No narcotics.’ And unfortunately we’re not able to. They are not able/willing to implement that. And I can understand that because at two o’clock in the morning when the hospitalist is called and says, ‘Somebody wants pain.’ And they’ve got three other admissions to deal with… just giving them a dose of IV Dilaudid versus going away from the other three admissions that are critically or more ill to go talk to the patient and try and talk them down, it’s not an easy button for them.” [Physician] | ||

| Balancing acute vs chronic care needs within IBD care | “One nice thing about my role is seeing patients if they get sick and if I’m like, ‘You know, they need to get a colonoscopy done, ASAP, things are not good.’ Our doctors are pretty good about getting them in for a procedure within a week or in a few days. So, overall I feel as though we can act pretty quickly and if we can’t, then we need them to get managed and expedited in their care, then I will admit them to the hospital and make sure that they’re getting appropriate care. But that, that comes with a risk because sometimes that’s where they get the pain meds sometimes, you know?” [Nurse practitioner] | ||

| Reported by patients only | Few solutions or concrete answers from IBD providers to manage pain safely and effectively | “I feel like I’ve never really been given any actual tangible solutions and you’re right, you can’t take Ibuprofen. There’s like nothing you can do, so I spend a lot of time with heating pads and you learn to tolerate the pain.” [Patient] | |

| Chronic pain related to IBD and its comorbidities | “You don’t read a lot about the fatigue or about the aches and pains… I think both are related because fatigue and pain sort of feed on each other. I think a lot of patients live with this discomfort or this ongoing malaise and there’s this perception that you’re sort of complaining or there are not a lot of solutions and physicians are great, but it seems like it’s not scientifically validated or studied in a way that makes you want to keep saying it and then what are you going to do about it. You’re supposed to just kind of keep going anyway. Because chronically ill patients are used to living uncomfortably so if you aren’t bleeding or you aren’t having horrific GI symptoms, you sort of just go on.” [Patient] | ||

| Living with the pain | “I would go to work and just try to make it through the day and everyone just said that my face was just drained. You could see the pain on my face. But again, I was so used to feeling this that this was beyond anything I had dealt with because I had suffered through pain.” [Patient] | ||

| Mental health impact of IBD | “The mind-gut connection of IBD and irritable bowel syndrome [IBS] is huge. Looking back on my whole experience in the past five to six years, having my resection, I did not know the mental obstacles I would face through all of this… So… my pains may not be physical joint pains or whatever. Mine has been more psychological just through my whole experience.” [Patient] | ||

| Experiencing pain from IBD starting at a young age | “I was also diagnosed in high school, my junior year. I think the pain that I experienced at the time, I just got used to it. I just dealt with it. Right before I had been diagnosed I was eating Tums like it was candy. That was what I ate and so when I fainted, I was severely anemic as well, and when I fainted my school nurse was like, "Oh, you may have a bleeding ulcer." I didn’t know what was going on, but that excruciating pain that you had, it was just like the discomfort within your bowels and everything. And, you know, you’re 17, you’re trying to figure out your own world and it’s not fun. It’s not cute at all.” [Patient] | ||

Abbreviation: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Reported by patients and providers

Both groups discussed concerns with opioid use and opioid-related side effects. This included general concerns, including risk of addiction or misuse, and opioid-related side effects that may be specific to the GI tract, and are particularly dangerous for patients with IBD. Both patients and providers also discussed having limited options to treat pain safely and effectively due to the specific risks of opioids and other pain medications, such as NSAIDs, to the GI system. Both groups described challenges with pain management needs due to patients’ comorbid illnesses beyond IBD. Although most patients described experiencing pain from extraintestinal IBD manifestations, particularly joint pains, others also discussed experiencing pelvic pain and pain related to irritable bowel syndrome.

Reported by providers only

Providers reported the importance of addressing patients’ expectations surrounding pain control. This included having in-depth conversations with patients about treatment options and removing expectations of a “quick fix” to their pain. Most providers acknowledged that individual pain management needs varied across IBD patients and that this was part of the rationale for some of their current practices, including conducting a detailed assessment to understand the underlying causes of pain or inflammation. Care coordination challenges described by providers included a lack of information about opioid prescriptions from other providers outside of the IBD clinic. They also discussed the idea that goals of care can vary outside of the IBD clinic, particularly in the ED, where non-IBD providers may not be aware of the unique risks of opioid use among IBD patients. Providers commented, moreover, that there currently was no formal procedure to conveniently track opioid prescriptions received by their patients, particularly those prescribed outside of the IBD clinic. Providers noted that these challenges—specifically a lack of information and potentially differing goals of care outside the IBD clinic—could contribute to patient safety issues such as unsafe opioid use. Providers also noted that carefully balancing acute versus chronic care needs within IBD care was important, both in general and to prevent long-term pain management needs. In instances when a patient may not be feeling well, for example, providers commented on a need to work quickly to address any acute patient needs. This may initially involve scheduling necessary procedures or admitting the patient as soon as possible to address underlying causes of pain or other symptoms. While providers found this to be challenging at times, they also suggested that being responsive to acute needs can help in minimizing longer-term issues with pain.

Reported by patients only

Patients commented that they often felt a lack of concrete answers from their IBD provider about why their pain was occurring and few tangible solutions to address the pain safely and effectively. Several patients also reported that they experienced chronic pain related to IBD and its comorbidities, including joint and musculoskeletal pain. Patients reported that, despite having a long-standing relationship with their IBD provider, they sometimes felt like their pain experiences were not well understood by providers, in part because of the lack of tangible solutions to manage chronic aches and pains. Many patients also described feeling a sense of hopelessness, accepting that they must tolerate or live with their pain as part of their daily life. They also discussed their perceptions around the mental health impact of their IBD. In this context, patients described feeling fear and anxiety about their pain returning as well as a perceived cycle of mental health and emotional stress exacerbating their IBD outcomes. Although providers discussed referring patients on occasion to GI-focused psychologists, few explicitly acknowledged the mental health burden of IBD and how that may be tied to pain issues. Several patients also noted the psychosocial challenges that they experienced pain from IBD starting at a young age. Onset of their IBD began during a formative, adolescent age, making it particularly challenging to manage their social life and growing independence with their painful early experiences with IBD.

Category 3 Themes: Suggestions to Optimize Pain Management in IBD Care

Table 4 presents provider-reported suggestions to optimize the delivery and safety of pain management in IBD care. As areas of improvement, providers suggested improving patient education and recalibrating patient expectations about pain management. Most providers commented on the need to educate patients and help them better understand the importance of targeting the underlying disease rather than masking it with pain medications. Providers also suggested enhancing non-IBD provider education on opioid safety and safer alternatives to treat pain, especially as it relates to the unique needs of patients with IBD. Providers recommended adopting a multidisciplinary approach to improve patient safety and care coordination. This included suggestions to leverage clinical alerts on patients’ electronic medical records to inform providers about potential opioid safety issues, such as polypharmacy, as well as collaborating with pain clinics and pharmacists to address pain safely. They also commented to the need to develop standardized approaches and tools to address pain and patient education related to pain. Few providers also suggested systematically expanding implementation of nonpharmacologic pain management strategies, including acupuncture and abdominal massages, more routinely among IBD patients. Providers also suggested that pain management efforts may be strengthened with a shift toward a patient-centered or “whole person” care model, including better understanding patient perspective of their pain management needs. Finally, 1 provider suggested that, as new interventions are developed to improve pain management safety, providers and researchers should carefully consider the potential challenges of changing provider behavior related to pain management.

Table 4.

Suggestions to optimize pain management in IBD care, reported by providers.

| Theme | Representative quote | |

|---|---|---|

| Reported by providers only | Improve patient education and recalibrate patient expectations about pain management | “Educate first and foremost. Because a lot of patients don’t realize how harmful pain medications can be to their disease. But just because we don’t want them to take pain medication doesn’t mean that we want them to be in pain. We want to treat their disease and get rid of their pain but sometimes it’s not a quick fix.” [Nurse] |

| “The biggest part is like education for patients, like understanding, making the correlation of like their disease process and where some medicines affect you long term. So I think education modules or any type of, you know, I mean, we’re so used to giving a pamphlet and I just think that gets kicked to the waste side. I think you got to think something electronically or something where patients have a better understanding of, um, what their disease is, because I can’t tell you how many times patients I still see don’t really understand their disease. You know, and I think it starts from there.” [Nurse Practitioner] | ||

| “I think [it] would be helpful if it’s something that we can visualize, but also that’s something we can show to a patient when we see them. Like, you know, is, is there a scale to show them, like with these comorbid conditions. This is the risk that you accrue if you’re going into chronic narcotic use or frequent narcotic use and what that could really factor into your care long-term. So, I think visualizing it for a patient when you see them and when they’re asking you for this would be really helpful.” [Nurse Practitioner] | ||

| Enhance provider education on opioid safety and safer alternatives to treat pain | “If we have [pain management information] on our website being an IBD center, [and] if other providers or patients from other sites are seeing this information, they understand how significant it is to avoid opioids and how they’re not hopeful and can actually be harmful in IBD.” [Nurse] | |

| Adopt a multidisciplinary approach to improve patient safety and care coordination | “The more we move towards a multi-disciplinary team, those things can be helpful. I think that IBD is very tied to colorectal surgery and vice versa because of the nature of what we do. I think that it could definitely benefit from having folks that are part of that integrative medicine plan. Having folks that are specializing in pain management, social workers, in addition to our dieticians and nutritionists. Having that multidisciplinary approach to patient care and maybe having even more dialogues or collaborations with those departments can only be helpful to the patient because they will have people to reach out to as opposed to just a referral generally to something that will have a point person for doing that.” [Physician] | |

| “Tracking medications [across centers] would be super helpful, because… some patients are really good about informing us when they’re on different types of medications. But others, we don’t hear from as much. And it’s pertinent to their disease process. That’s information that we want to know. So if it were something that were more readily available to us, I think it’d be helpful.” [Physician] | ||

| Develop standardized approaches and tools to address pain | “I think… we all approach things very similarly as far as pain management, from a provider perspective. But, I think that it’s not documented anywhere, like this is the process. If a patient has X, Y and Z, what is the process map for treating them, and what is the goal for us and for our patients, and how do we get there? I don’t necessarily want to say a standardized approach, because it’s really difficult to standardize things with our patients as we talked about. But, if there was maybe just something, like a process that we could work through, like a tool. A tool between not just the provider but the patient and the provider, so we’re all on the same page.” [Nurse] | |

| Routinely implementing nonpharmacologic pain management strategies | “There are non-steroid types of things that we can use for abdominal cramping, abdominal bloating. IBGard, which has peppermint oil, can also be used as an adjunct. Also, things that are not typically considered a part of Western medicine, but Eastern medicine. For instance, acupuncture can be used, abdominal massages can used, referrals to Shirley Ryan for our physiatrist to actually see patients to manage other chronic related pain conditions associated with it.” [Physician] | |

| Shift toward a patient-centered or “whole person” care model | “When you’re treating an IBD patient, not only are you treating the disease… There’s a whole health maintenance aspect of it. There’s mental health. There’s all this cancer screening that we have to do. I think it’s part of the puzzle. Rather than just treating the IBD, if we were looking at things more holistically, it could be helpful. And then, it would help all these things that I’m like, ‘Well, I feel like we could do a better job with mental health. Or, I feel like we could do a better job of taking control if it was just more of the focus.’” [Nurse] | |

| “My sense is a lot of our patients would tell you they’re maybe not being treated for their pain… It would be interesting to see from the patient’s side, because maybe they think we undertreat pain. They probably do. I don’t know.” [Physician] | ||

| “I think as an IBD provider, you look at the patient as a whole. I don’t know. This specific patient, I care because I care about him. That’s the bottom-line answer. I care because I care about him as a person and as a whole. Yes, opioid dependence definitely has an impact on the colitis. It can increase the risk for a toxic colon and so on and so forth, especially if you’re inflamed. Then we’ve talked all about that. Yeah, it impacts me that way. The reason that I wanted him to stop was it is for the colitis, but also for himself as a person.” [Physician] | ||

| Consider potential challenges of changing provider behavior related to pain management | “I’m a bit cynical when it comes to resources because I’ve seen so many that are just not useful, websites and brochures and calculators, and phone numbers and support groups, and all this stuff. And I just don’t think any of those things replace the one-on-one conversation with a provider. I’m certainly willing to use those types of things, but I just don’t know how that looks… It’s hard for me to disconnect my own personal opinions from my patients. So, if I don’t think it would help me as a person, it’s hard for me to make that leap to advise my patients use it. If I think an app to track whatever is silly for me, why would I then go and tell my patients to use it? So, that’s a huge barrier for me. If I don’t personally buy into it, how do I then go and try to sell it to my patients? Part of it is me. Part of it is my own biases and my own opinions, and things like that. And maybe, the intervention needs to be for me rather than for my patients, but that’s sort of my own issue.” [Physician] |

Abbreviation: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Discussion

In this study, we leveraged the strengths of qualitative research methods35 and included patients and providers to examine their perceptions and experiences on current practices and challenges related to pain management in IBD care. Through this investigation, we also obtained practical suggestions to improve the delivery and safety of pain management for individuals with IBD. By triangulating patient and provider viewpoints, findings from this study underpin a novel contribution that has not been previously described in the IBD literature focused on pain management or patient safety: Despite some common themes between IBD patients and providers, including the importance of patient–provider relationships and concerns about opioid use, we note a potential misalignment between how patients with IBD and providers who treat IBD describe their pain management needs and experiences and, subsequently, the steps they take to manage pain. The management of pain in IBD patients could be improved by better balancing acute and chronic pain management needs and by better recognizing the overlap between IBD-related pain and IBD-related psychosocial comorbidities. Addressing these unique needs may go beyond IBD providers’ current practices and resources.

The burden of pain and characteristics of opioid utilization among individuals with IBD are well established,12,15,27,37–39 as are the needs to improve pain management and opioid reduction efforts.13 This work uniquely builds on prior literature to provide depth and nuance to the current evidence base, bringing together patient and provider perspectives in a way that quantitative research, typically, cannot. We learned that providers in this study often considered pain among their IBD patients—and any needs for pain management—as part of specific disease-related events, such as periods of active inflammation, that invariably occur along the continuum of IBD care. This led to a data-driven approach in which providers usually assessed the possible underlying physiologic causes of pain and used an informal decision pathway to treat pain as a short-term concern. In most cases, providers’ overarching goals were to address the active disease or inflammation, anticipating that any pain reported by patients would subsequently be addressed as well. In contrast, the patient viewpoint in this study did not include many of these terms, including “active disease” or “treating the underlying inflammation.” Patient perceptions of their own pain management needs, instead, went beyond traditional clinical parameters, suggesting that issues related to chronic pain and comorbid joint pain were, often, a part of daily life as an IBD patient and may need to be addressed even during times of clinical remission. Some patients also felt that they had to simply “live with” their chronic pain, either because there were no safe and effectives remedies, or because their provider did not recognize their chronic pain. Patients’ concerns and experiences related to pain were also closely tied to the complex interplay of psychosocial elements of IBD, including fatigue and the widely recognized mental health burden associated with having IBD.40–42

A few prior studies have observed differences between IBD patient and provider views and expectations related, more broadly, to IBD care delivery. We previously demonstrated, for example, that IBD patients’ understanding of the terms “active IBD flares” and “remission” is largely symptom based, and often differs from clinician knowledge.43 This pointed to a need to improve patient education and, in conjunction, increase awareness of patients’ perspectives among IBD providers. Additionally, a recent review found that, to improve the quality of care provided to patients with IBD, efforts to better align patient and physician expectations are essential.44 These calls to enhance the alignment of patient and provider expectations are also corroborated in the larger GI literature beyond IBD.45 Our study findings extend the existing evidence in this area to suggest that potential differences between IBD patient and provider groups may be especially prominent on the subject of pain management. And, as suggested in the broader pain management literature, this may contribute to a misalignment in healthcare expectations, gaps in patient–provider communication, and, in turn, possibly unsafe opioid use.46–48 Addressing the areas of potential disconnect between patients and providers, as we observed in this study, will undoubtedly be necessary for any effort to align these groups and incorporate their voices into future pain management and patient safety initiatives in IBD care. And although the focus of many opioid safety research and quality improvement studies remains on metrics such as the number of opioid pills dispensed to a patient at a given time, findings suggest that our efforts should—perhaps first and foremost—shift toward understanding and bridging any potential disconnect between patients and providers. Opioid safety initiatives in IBD should include new strategies, such as increasing patient engagement and shared decision-making in pain management discussions, that have already been used to enhance pain management and its safety in other clinical settings.49–51 It should also focus on recognizing the impact of pain on patients’ social and emotional wellbeing, particularly for those with chronic pain. Implementation of these strategies can easily leverage the long-standing supportive relationships between IBD patients and their providers, which nearly all our study participants reported enjoying.

It is likely that one starting point to better align patients and providers in such safety initiatives will be to leverage the common themes we found across both groups. Among both patients and providers included in this study, for example, there was broad recognition that (1) pain is a significant problem in IBD care; (2) there appear to be limited pharmacologic options to treat pain safely and effectively; (3) prolonged opioid use, and any related side effects, is concerning; (4) there is a need to expand our understanding and use of safe, effective nonpharmacologic pain remedies; as well as (5) a need to engage non-IBD providers in pain management and patient safety efforts for this patient population. Long-term patient–provider relationships and trust, furthermore, were valued by both groups. This, perhaps, is where an integrated, patient-centered care model, as suggested by participants themselves, can be particularly beneficial.

Predicated on the principles of delivering comprehensive, high-quality and coordinated care with a commitment to meeting patient needs and preferences, patient-centered care models have already been successfully implemented in some IBD care centers.52,53 Prior studies have noted that this model, in the context of IBD, can be especially valuable in individualizing care, improving patient engagement and education, and addressing patients’ mental health needs as part of their routine care.54 As adoption of patient-centered care increases across IBD centers, these approaches can be expanded to also include pain specialists as part of routine care, helping to inform patients and providers about safer nonopioid pain management options as well as nonpharmacologic options derived from complementary and integrative medicine. Early evidence has shown, moreover, that a patient-centered IBD care model can support reductions in opioid use.55

This study also begins to unpack the complex challenge faced by IBD providers to both manage IBD and relieve pain while being attuned to a patient’s individual safety needs and risks. Although providers in this study reported that they generally avoided opioid prescribing in their IBD practice, they acknowledged that they often lacked information about prescriptions their patients receive from other providers for comorbid conditions. Most patients in our study also reported having been prescribed opioids at some point in their experience with IBD. Given the higher prevalence among IBD patients of mental health illnesses as well as painful non-GI comorbidities,56–59 it is possible that a lack of coordination of care across specialties is a contributing factor toward the high rates of opioid use and polypharmacy observed in recent IBD-focused analyses.14,27,60 Although opioid use monitoring through audit-and-feedback and statewide prescription drug monitoring programs may help to address this issue,19,61 this study and our prior research demonstrate that these interventions are seldom used by IBD providers.62 And as some providers noted in this study, there may be a lack of easily accessible and reliable information about IBD patients’ opioid use and risk factors for unsafe opioid use, particularly as it corresponds to care of comorbid conditions outside of the IBD clinic.

Providers should be aware that, for patients, pain can permeate across the IBD continuum of care—often due to non-IBD reasons such as a back pain or kidney stones—and that strategies are needed to address it on an ongoing basis safely and seamlessly. Extraintestinal manifestations and comorbidities—including psychologic, rheumatologic, or musculoskeletal conditions—can also impact pain and how it is perceived. Developing and implementing safe and coordinated pain management strategies will invariably require the active engagement—not only of providers, but also—of patients and quality improvement researchers. Beyond a patient-centered model where pain specialists can readily lend their expertise, providers in this study suggested a need to address gaps in knowledge that may lead to opioid safety issues. These gaps may include, for example, lack of information among IBD providers about their patients’ opioid use for comorbid conditions or a lack of knowledge among non-IBD providers about the risks of prolonged opioid use among IBD patients. To address these gaps, perhaps we must draw on lessons learned from initiatives outside of IBD at the intersection of coordination of care and opioid safety, such as a Department of Veterans Affairs effort to use learning health systems to track opioid use data and deliver tailored safety information to patients and providers in a way that supports patient education needs and providers’ clinical decision-making.63,64 Applying such an approach in IBD care could be an especially viable strategy given the importance of building long-term patient–provider relationships and trust, as participants suggested in our findings.

The study is subject to several limitations. Although participants represented patient and provider groups, they were recruited from a single institution. Our findings may not represent the larger population of IBD patients and providers and may not translate to other clinical settings or populations. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the patient participants may have impacted their experiences with pain and, by extension, the study findings. More than half of our patient participants had undergone prior IBD surgery and most were diagnosed with Crohn’s disease. The sample was predominately female and, furthermore, may not have captured the diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds observed in the current IBD population.65 As described in existing methodological literature, however, the goal of qualitative research is, often, to investigate discrete phenomenon in-depth and not to generalize broadly to larger populations. To this end, smaller sample sizes, such as those in this study, are appropriate if thematic saturation is reached.35,66 Future research should include a greater focus on gathering the views of individuals with IBD from racial or ethnic minority backgrounds, as well as other types of providers, such as emergency medicine physicians and GI surgeons, who may not be directly involved in chronic IBD care, but often play an essential role in the care of patients with IBD.

Conclusion

In this study, we qualitatively examined current practices and challenges related to pain management in IBD care and engaged patients and providers in a discussion about how to tailor pain management practices to the unique needs of this patient population. These findings suggest a misalignment between IBD patients and providers in terms of how these 2 groups describe pain management needs and experiences, how they perceive these topics, and the steps they take to manage pain. Beyond expanding safe, effective pain management options, we learned that there is a need to (1) acknowledge pain as a major issue in IBD; (2) better inform providers about IBD patients’ opioid use, particularly for comorbid conditions; and (3) partner with patients on efforts to optimize pain management and patient safety to ensure their complex and unique needs are met. Taken together, findings from this study underscore a need to shift existing pain management and safety practices in IBD care to better address potential communication gaps between patients and providers surrounding these topics. Future efforts should focus on actively engaging patients as partners with providers and health systems to optimize pain management and reduce unsafe opioid use in this population.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Salva N Balbale, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, USA; Center for Health Services and Outcomes Research, Institute of Public Health and Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, USA; Center of Innovation for Complex Chronic Healthcare, Health Services Research & Development, Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital, Hines, Illinois 60141, USA.

Cassandra B Iroz, Department of Surgery, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Willemijn L A Schäfer, Center for Health Services and Outcomes Research, Institute of Public Health and Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, USA; Department of Surgery, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Julie K Johnson, Center for Health Services and Outcomes Research, Institute of Public Health and Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, USA; Department of Surgery, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Jonah J Stulberg, Department of Surgery, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, USA; Department of Surgery, University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston, Texas, USA.

Authors’ Contributions

Concept and design: S.N.B. and J.J.S. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: S.N.B. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Administrative, technical, or material support: S.N.B. and J.J.S. Supervision: J.K.J. and J.J.S.

Funding

This work was supported by the Digestive Health Foundation (an institutional grant affiliated with Northwestern University’s Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology; Co-PIs: S.N.B. and J.J.S.).

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Data Availability

Data available upon request.

References

- 1. Ramos GP, Papadakis KA.. Mechanisms of disease: inflammatory bowel diseases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(1):155–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(12):720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alatab S, Sepanlou SG, Ikuta K, et al. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(1):17–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bielefeldt K, Davis B, Binion DG.. Pain and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(5):778–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, et al. Direct health care costs of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in US children and adults. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(6):1907–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Park K, Ehrlich OG, Allen JI, et al. The cost of inflammatory bowel disease: an initiative from the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Graff LA, Walker JR, Lix L, et al. The relationship of inflammatory bowel disease type and activity to psychological functioning and quality of life. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(12):1491–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sweeney L, Moss-Morris R, Czuber-Dochan W, Meade L, Chumbley G, Norton C.. Systematic review: psychosocial factors associated with pain in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(6):715–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheatle MD. Prescription opioid misuse, abuse, morbidity, and mortality: balancing effective pain management and safety. Pain Med. 2015;16(Suppl 1):S3–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Balbale SN, Cao L, Trivedi I, et al. Opioid-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations among patients with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms and disorders dually enrolled in the Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare Part D. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Szigethy E, Knisely M, Drossman D.. Opioid misuse in gastroenterology and non-opioid management of abdominal pain. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(3):168–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Targownik LE, Nugent Z, Singh H, Bugden S, Bernstein CN.. The prevalence and predictors of opioid use in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(10):1613–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scott FI, Rubin DT, Kugathasan S, et al. Challenges in IBD research: pragmatic clinical research. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(Suppl 2):S40–S47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Niccum B, Moninuola O, Miller K, Khalili H.. Opioid use among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(5):895–907.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alley K, Singla A, Afzali A.. Opioid use is associated with higher health care costs and emergency encounters in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(12):1990–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anderson A, Click B, Ramos-Rivers C, et al. The association between sustained poor quality of life and future opioid use in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(7):1380–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Click B, Ramos Rivers C, Koutroubakis IE, et al. Demographic and clinical predictors of high healthcare use in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(6):1442–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Szigethy EM, Murphy SM, Ehrlich OG, et al. Opioid use associated with higher costs among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Crohns Colitis 360. 2021;3(2):otab021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crocker JA, Yu H, Conaway M, Tuskey AG, Behm BW.. Narcotic use and misuse in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(12):2234–2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Noureldin M, Higgins PD, Govani SM, et al. Incidence and predictors of new persistent opioid use following inflammatory bowel disease flares treated with oral corticosteroids. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(1):74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wren AA, Bensen R, Sceats L, et al. Starting young: trends in opioid therapy among US adolescents and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease in the Truven MarketScan database between 2007 and 2015. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(10):2093–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Coates M, Seth N, Clarke K, et al. Opioid analgesics do not improve abdominal pain or quality of life in Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65(8):2379–2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Drossman D, Szigethy E.. The narcotic bowel syndrome: a recent update. Am J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2014;2(1):22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Frank JW, Lovejoy TI, Becker WC, et al. Patient outcomes in dose reduction or discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(3):181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jones JL, Loftus EV Jr. Avoiding the vicious cycle of prolonged opioid use in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(10):2230–2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Szigethy E, Schwartz M, Drossman D.. Narcotic bowel syndrome and opioid-induced constipation. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16(10):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cohen-Mekelburg S, Rosenblatt R, Gold S, et al. The impact of opioid epidemic trends on hospitalised inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(9):1030–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bernhofer EI, Masina VM, Sorrell J, Modic MB.. The pain experience of patients hospitalized with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2017;40(3):200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sweeney L, Moss-Morris R, Czuber-Dochan W, Belotti L, Kabeli Z, Norton C.. ‘It’s about willpower in the end. You’ve got to keep going’: a qualitative study exploring the experience of pain in inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Pain. 2019;13(4):201–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J.. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Simmonds MJ, Finley EP, Vale S, Pugh MJ, Turner BJ.. A qualitative study of veterans on long-term opioid analgesics: barriers and facilitators to multimodality pain management. Pain Med. 2015;16(4):726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hardeman W, Johnston M, Johnston D, Bonetti D, Wareham N, Kinmonth AL.. Application of the theory of planned behaviour in behaviour change interventions: a systematic review. Psychol Health. 2002;17(2):123–158. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ.. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schwarze ML, Kaji AH, Ghaferi AA.. Practical guide to qualitative analysis. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(3):252–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miles MB, Huberman AM.. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Casati J, Toner BB, De Rooy EC, Drossman DA, Maunder RG.. Concerns of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45(1):26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schirbel A, Reichert A, Roll S, et al. Impact of pain on health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(25):3168–3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zeitz J, Ak M, Müller-Mottet S, et al. Pain in IBD patients: very frequent and frequently insufficiently taken into account. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sajadinejad MS, Asgari K, Molavi H, Kalantari M, Adibi P.. Psychological issues in inflammatory bowel disease: an overview. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Szigethy EM, Allen JI, Reiss M, et al. White paper AGA: the impact of mental and psychosocial factors on the care of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(7):986–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Van Langenberg D, Gibson PR.. Systematic review: fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(2):131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Trivedi I, Darguzas E, Balbale SN, et al. Patient understanding of “flare” and “remission” of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2019;42(4):375–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Al Khoury A, Balram B, Bessissow T, et al. Patient perspectives and expectations in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;67:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ahmed S, Almario CV, Chey WD, et al. Sa1083 marked disagreement between referring physicians and patients’ reason for GI consultation. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(4):S234–S235. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Matthias MS, Johnson NL, Shields CG, et al. “I’m not gonna pull the rug out from under you”: patient-provider communication about opioid tapering. J Pain. 2017;18(11):1365–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Matthias MS, Krebs EE, Collins LA, Bergman AA, Coffing J, Bair MJ.. “I’m not abusing or anything”: patient–physician communication about opioid treatment in chronic pain. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(2):197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nicolaidis C. Police officer, deal-maker, or health care provider? Moving to a patient-centered framework for chronic opioid management. Pain Med. 2011;12(6):890–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Frantsve LME, Kerns RD.. Patient–provider interactions in the management of chronic pain: current findings within the context of shared medical decision making. Pain Med. 2007;8(1):25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Henry SG, Matthias MS.. Patient-clinician communication about pain: a conceptual model and narrative review. Pain Med. 2018;19(11):2154–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shields CG, Fuzzell LN, Christ SL, Matthias MS.. Patient and provider characteristics associated with communication about opioids: an observational study. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(5):888–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Regueiro M, Click B, Anderson A, et al. Reduced unplanned care and disease activity and increased quality of life after patient enrollment in an inflammatory bowel disease medical home. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(11):1777–1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Regueiro M, Click B, Holder D, Shrank W, McAnallen S, Szigethy E.. Constructing an inflammatory bowel disease patient-centered medical home. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(8):1148–1153.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Weaver E, Szigethy E.. Managing pain and psychosocial care in IBD: a primer for the practicing gastroenterologist. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22(4):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Szigethy E, Goldblum Y, Weaver EK, et al. Su1782 – reduction of opioid use and depression within an IBD medical home care model. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(6):S-609–S-610. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bähler C, Schoepfer AM, Vavricka SR, Brüngger B, Reich O.. Chronic comorbidities associated with inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and impact on healthcare costs in Switzerland. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(8):916–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bakshi N, Hart AL, Lee MC, et al. Chronic pain in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Pain. 2021;162(10):2466–2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bernstein CN, Hitchon CA, Walld R, et al. Increased burden of psychiatric disorders in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(2):360–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]