Key Points

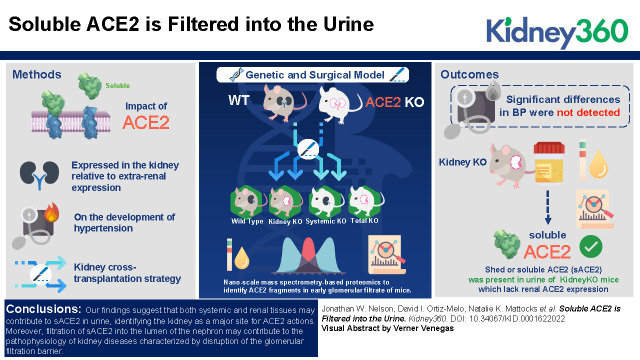

Combining unique genetic and surgical models, we demonstrate that both renal and systemic sources contribute to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) detected in the urine in angiotensin II–mediated hypertension.

Micropuncture coupled with nanoproteomics confirm detection of ACE2 in early glomerular filtrate obtained from Bowman’s capsule in mice.

Kidney-derived ACE2 and soluble ACE2 may be useful clinical targets in kidney disease.

Keywords: hypertension, ACE2, basic science, kidney, renin angiotensin system, soluble ACE2

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

ACE2 is a key enzyme in the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) capable of balancing the RAS by metabolizing angiotensin II (AngII). First described in cardiac tissue, abundance of ACE2 is highest in the kidney, and it is also expressed in several extrarenal tissues. Previously, we reported an association between enhanced susceptibility to hypertension and elevated renal AngII levels in global ACE2-knockout mice.

Methods

To examine the effect of ACE2 expressed in the kidney, relative to extrarenal expression, on the development of hypertension, we used a kidney crosstransplantation strategy with ACE2-KO and WT mice. In this model, both native kidneys are removed and renal function is provided entirely by the transplanted kidney, such that four experimental groups with restricted ACE2 expression are generated: WT→WT (WT), KO→WT (KidneyKO), WT→KO (SystemicKO), and KO→KO (TotalKO). Additionally, we used nanoscale mass spectrometry–based proteomics to identify ACE2 fragments in early glomerular filtrate of mice.

Results

Although significant differences in BP were not detected, a major finding of our study is that shed or soluble ACE2 (sACE2) was present in urine of KidneyKO mice that lack renal ACE2 expression. Detection of sACE2 in the urine of KidneyKO mice during AngII-mediated hypertension suggests that sACE2 originating from extrarenal tissues can reach the kidney and be excreted in urine. To confirm glomerular filtration of ACE2, we used micropuncture and nanoscale proteomics to detect peptides derived from ACE2 in the Bowman’s space.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that both systemic and renal tissues may contribute to sACE2 in urine, identifying the kidney as a major site for ACE2 actions. Moreover, filtration of sACE2 into the lumen of the nephron may contribute to the pathophysiology of kidney diseases characterized by disruption of the glomerular filtration barrier.

Introduction

First reported just 20 years ago, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is a monocarboxypeptidase that is distinct from its homolog, the dicarboxypeptidase ACE (1). ACE2 hydrolyzes several angiotensin peptides but has highest affinity for Angiotensin II (AngII) (1). By removing a single amino acid from AngII, ACE2 generates Ang(1–7), which signals via the Mas receptor (2), and thereby plays an integral role in AngII metabolism and balancing the overall tone of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) (3). ACE2 has been implicated in several clinical cardiovascular and renal pathologies, including heart failure, where it was first described (1), along with hypertension and CKD (4–7). Because of its pivotal position in the RAS, ACE2 remains the focus of studies aimed at understanding the regulation of cardiovascular and renal function. Furthermore, although not directly examined in these studies, ACE2 also serves as the receptor for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 and, as such, plays a significant role in coronavirus disease 2019 complications, including a high incidence of kidney dysfunction (8–11).

Previously, our group leveraged the use of gene-targeting in mice to study cardiovascular and renal functions of ACE2 (12). We generated global ACE2-knockout (ACE-KO) mice and observed that lack of ACE2 was associated with an exaggerated BP response and elevated AngII peptide levels in the kidney during AngII-mediated hypertension (12). We also showed that, under baseline conditions, reduced ability to degrade AngII was associated with increased oxidative stress in kidney tissue from ACE2-KO mice (13). Furthermore, research by others using ACE2-KO mouse models revealed that, in addition to modulating BP (14–16), ACE2 also protects against cardiac hypertrophy (17) and plays a role in diabetic renal injury (4).

ACE2 exists as a membrane-bound protein but can be cleaved by ADAM17 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein) to produce a smaller, shed, or soluble form (soluble ACE2 [sACE2]) that maintains catalytic activity (18). Shedding can functionally relocate ACE2 activity, moving ACE2 from cells where it was originally expressed to allow ACE2 to gain access to new sites where it can regulate AngII levels (19). As an example, cleavage of ACE2 from cells in the central nervous system into the cerebrospinal fluid exacerbates hypertension due to loss of local brain ACE2 activity (19). Although these studies by Xia et al. (19) identified regulatory mechanisms for the local brain RAS, it remains unknown how shedding of ACE2 functions in the kidney. Here, we examine the relative contributions of renal versus systemic ACE2 by genetically restricting expression to renal or systemic tissues. Our kidney crosstransplant studies, combined with micropuncture-guided nanoproteomics, demonstrate that extrarenal sources of sACE2 are able to reach the kidney where it may play a role to modulate the renal RAS during AngII-mediated hypertension.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

The generation of ACE2-KO mice has been previously described (12). Kidney crosstransplant experiments were performed in male (129×C57BL/6)F1 ACE2-KO mice, at 2–4 months of age, along with their age-matched, wild-type (WT) littermates (Figure 1A). Aspiration of glomerular filtrate was performed on 8- to 12-week-old male C57BL/6 mice purchased from Jackson Laboratories (21).

Figure 1.

ACE2 expression and activity reflect crosstransplantation groups. (A) Schematic depicting experimental strategy. Wild-type (WT; +/y) or ACE2-knockout (ACE2-KO) mice (−/y) were transplanted with either a WT or ACE2-KO kidney. The WT cohort had a full complement of ACE2; the KidneyKO group expressed ACE2 systemically, with no expression of ACE2 in the transplanted kidney. Mice in the SystemicKO group expressed ACE2 in the kidney, but not systemically, and the TotalKO group lacked ACE2 expression globally. (B) Renal Ace2 mRNA expression confirms expression of ACE2 within the crosstransplanted groups according to genotype. (C) Immunoblot demonstrating expression of full-length ACE2 in the kidneys of WT and SystemicKO mice, but not in KidneyKO or TotalKO animals. (D) Cortical ACE2 activity assay demonstrates a lack of ACE2 within the kidneys of the KidneyKO and TotalKO cohorts. Data expressed as mean±SEM, analyzed as one-way ANOVA with a Dunnett multiple comparison post hoc analysis. N=3–7 animals per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

All animals were bred, housed, or maintained in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International–accredited animal facility at the Durham Veterans Affairs Health Care Center, Oregon Health and Science University, or the Portland Veterans Affairs Medical Center, according to National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Approval for animal care and experiments was granted by institutional animal care and use committees.

Renal Crosstransplantation

Mouse renal transplantation surgeries were performed as previously described (22,23). Briefly, the donor kidney, ureter, and bladder were harvested en bloc, including the renal artery and vein with a small aortic and vena cava cuff, respectively. End-to-side anastomoses were created, below the level of the native renal vessels. In the same way, the recipient vena cava was anastomosed to the donor vena cava cuff. Total ischemic time averaged 20 minutes. Donor and recipient bladders were anastomosed dome to dome. The left native kidney was removed at the time of transplant surgery, and the right native kidney was removed through a flank incision 1–3 days later. The adrenal glands and adrenal blood supply were preserved.

Measurement of BP

BPs were measured in conscious, unrestrained mice using a radiotelemetry system, as described previously (12). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with inhaled 1.5% isoflurane and a nonthrombogenic, pressure-sensing catheter connected to a small radiotelemetry device (DSI PAC-10) was inserted into the carotid artery of the mouse and advanced into the aortic arch. The transducer unit was then inserted into a subcutaneous pouch along the right flank. Before measurements were recorded, mice were given 1 week to recover from surgery and regain normal circadian rhythm. During the measurement period, mice were housed unrestrained in individual cages, in a quiet monitoring room. BPs were measured continuously over a 10-second interval every 5 minutes and data were collected, stored, and analyzed using Dataquest ART software (version 4.1; Transoma Medical). Telemetry values were averaged before or after AngII osmotic pump implantation to determine baseline and AngII-mediated hypertension values, respectively, for mean arterial pressure (MAP), systolic BP, diastolic BP, and heart rate.

Experimental Protocol

Baseline BPs were measured continuously for 2 weeks while the animals ingested a normal chow diet (LabDiet 5001) and had free access to water. After baseline recordings, AngII peptide (A9525; Sigma-Aldrich) was infused at a dosage of 1000 ng/kg per minute for 2 weeks using subcutaneous osmotic minipumps (Alzet 1004) (12,24). During the infusion period, BPs were monitored by radiotelemetry as described above. Urine was collected as 24-hour samples in individual metabolic cages (Hatteras Instruments, Cary, NC). At the end of the experiment, serum was collected and the kidney was harvested. Animals were euthanized under 4.5% isoflurane by exsanguination.

Enzymatic ACE2 Activity

ACE2 activity was determined after incubation with the intramolecularly quenched synthetic ACE2-specific substrate Mca-APK-Dnp (Anaspec), as previously described (13).

Analysis of ACE2 Protein in Kidney and Urine by Immunoblot

Approximately 2–3 mg of kidney cortex was homogenized in a buffer containing 20 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.4), 2 mmol/L EDTA, 0.3 mol/L sucrose, 1.0% nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, and 1:100 dilution of a protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340; Sigma). Kidney homogenates were centrifuged for 30 minutes at 1000 × g, and supernatants were stored at −80°C. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Protein Assay). For urine samples, equal volumes of undiluted urine were loaded into a 4%–12% PAGE. Detection of ACE2 protein by immunoblot was carried out as previously described (12).

RNA Isolation and Analysis

Relative levels of mRNA for Ace2 were measured in kidney cortices from each group. RNA was isolated and reverse transcription performed using qScript cDNA Supermix (Quanta Biosciences). Quantitative PCR was carried out using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The amount of target gene relative to endogenous control was determined by the ΔΔCT method. The following primer sequences were used:

ACE2 forward, 5′-ACTCACAGCAACCCTCCAAG-3′;

ACE reverse, 5′-ATCACCACCAAGCTGTTTCC-3′ (236 bp);

GAPDH forward, 5′-TCACCACCATGGAGAAGGC-3′;

GAPDH reverse, 5′-GCTAAGCAGTTGGTGGTGCA-3′ (168 bp);

18S forward, 5′-TCACCACCATGGAGAAGGC-3′; and

18S reverse, 5′-GCTAAGCAGTTGGTGGTGCA-3′ (168 bp).

Measurement of ACE2 in Early Glomerular Filtrate

Samples (n=4) were obtained via micropuncture from the Bowman’s space and analyzed as previously described (21).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism. Values for each parameter are expressed as the mean±SEM, with individual data points plotted when possible. The statistical analysis used for each comparison is described within each figure legend. Statistical significance was defined as a P<0.05. Peptide identifications from mass spectrometry were filtered against a reversed decoy database at false discovery rate of 0.01. Peptide BLAST alignments were filtered for statistical significance at an e-value <0.05. Binary comparisons of peptide origin (sequences corresponding to endo- or ectodomain) in plasma and glomerular filtrate samples were carried out by chi-squared analysis.

Results

Effect of Renal ACE2 on BP Regulation and Renal and Cardiac Injury

To examine the relative contribution of renal ACE2 to the pathogenesis of AngII-mediated hypertension, we used a kidney crosstransplantation approach (22,25–27). Specifically, we transplanted kidneys from genetically matched (129×C57BL/6)F1 WT and ACE2-KO mice into (129×C57BL/6)F1 WT and ACE2-KO recipients, such that four kidney crosstransplant groups were generated: WT, KidneyKO, SystemicKO, and TotalKO (Figure 1A). Because all mice underwent bilateral native nephrectomy, expression of ACE2 was determined experimentally by genotype of transplanted kidney and recipient. As controls, a group of WT recipients were transplanted with kidneys from WT donors (WT). In KidneyKO mice, ACE2 expression is maintained in systemic tissues but absent from the kidney; conversely, in SystemicKO mice, ACE2 expression is maintained within the single transplanted kidney, but is absent from all other systemic tissues. Lastly, ACE2-KO mice were transplanted with ACE2-KO kidneys to generate TotalKO mice, which lacked ACE2 expression in all tissues. These models were validated by measuring renal ACE2 mRNA and protein expression and renal cortical ACE2 activity, which followed the genotype of recipient and donor as expected (Figure 1, B–D).

At baseline, there were no differences in BPs among the four groups, consistent with our previous findings in ACE2-KO mice (Figure 2A, Table 1) (12). During infusion of AngII, BPs increased significantly from baseline in all four groups, and mean±SEM MAPs during AngII infusion for WTs (132±7 mm Hg), KidneyKOs (140±4 mm Hg), and SystemicKOs (141±13 mm Hg) were nearly identical (P=0.83; Figure 2A, Table 1). The mean±SEM MAP response in the TotalKO group was higher than that of the other groups (148±5 mm Hg) throughout the infusion period, but this did not reach statistical significance. Additionally, there were no differences in systolic BP, diastolic BP, or heart rate (Table 1). Nonetheless, compared with the WT group, TotalKO mice developed significantly more pronounced cardiac hypertrophy (6.3±0.2 and 7.2±0.4 mg/g, P=0.03 versus WT; heart weight/body weight; Figure 2B), a surrogate marker for chronic BP elevation (28). Furthermore, urinary albumin excretion was significantly increased in TotalKO mice (3224±663 and 1519±457 µg, P=0.02 versus WT; Figure 2C). Thus, expression of ACE2 in either the kidney or extrarenal compartment appears similarly capable of modulating BP responses and attenuating hypertensive complications during chronic AngII infusion.

Figure 2.

ACE2 expression in the kidney or systemic tissues attenuate hypertensive complications. (A) Mean arterial pressures (MAPs) at baseline and with continuous angiotensin II (AngII) infusion for 15 days. (B) Heart weight/body weight (HW/BW) ratios of crosstransplanted mice at the end of the experiment. (C) Twenty-four-hour albumin excretion during AngII infusion. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. HW/BW and albuminuria were analyzed as t test between WT and TotalKO groups. N=6–11 animals per group. *P<0.05.

Table 1.

Summary of telemetry measurements

| Measurement | Mean±SEM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild- Type | KidneyKO | SystemicKO | TotalKO | |

| Baseline | ||||

| MAP (mm Hg) | 112±2 | 113±2 | 107±5 | 111±1 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 128±3 | 128±3 | 120±5 | 124±1 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 99±2 | 97±2 | 93±5 | 96±2 |

| HR (bpm) | 579±8 | 576±9 | 563±11 | 570±6 |

| AngII HTN | ||||

| MAP (mm Hg) | 132±7 | 140±4 | 141±13 | 148±5 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 150±7 | 159±5 | 155±13 | 161±5 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 120±6 | 122±4 | 127±14 | 136±6 |

| HR (bpm) | 519±22 | 535±26 | 553±20 | 549±11 |

Shown are measurements at baseline and during AngII-HTN. KidneyKO, systemic expression of ACE2 with no expression of ACE2 in the transplanted kidney; SystemicKO, expression of ACE2 in the kidney but not systemically; TotalKO, global lack of ACE2 expression; MAP, mean arterial pressure; SBP, systolic BP; DBP, diastolic BP; HR, heart rate; AngII HTN, angiotensin II–mediated hypertension.

Extrarenal Source of sACE2 in Serum and Urine

On the basis of our previous studies using conventional ACE2-KO mice, we had hypothesized that ACE2 actions within the kidney to metabolize AngII were critical to abrogate hypertension. To examine potential mechanisms explaining the lack of effect of ACE2 deficiency in the kidney alone on AngII-dependent hypertension, we examined circulating and urinary levels of ACE2 in the transplanted groups. Although our primary goal was to confirm that ACE2 expression and activity followed the patterns expected on the basis of genotype, we considered the possibility that ACE2 arising from extrarenal tissues might enter the kidney circulation and/or urine to provide a compensatory source of ACE2 contributing to the attenuated BP response observed in the KidneyKOs during AngII-mediated hypertension. As shown in Figure 3A, plasma levels of ACE2 activity were significantly reduced in SystemicKOs and TotalKOs, indicating a major contribution of extrarenal tissues to circulating ACE2 levels, as predicted by genotype. Yet, reduced plasma ACE2 activity alone in SystemicKOs did not affect baseline BP or increase hypertensive responses to AngII infusion, indicating an ability of ACE2 in kidney to compensate for its absence in systemic tissues.

Figure 3.

Soluble ACE2 is filtered into the urine. (A) Plasma ACE2 activity. (B) ACE2 activity in the urine (24-hour urine collection). (C) Composite immunoblot demonstrating full-length ACE2 in the urine of WT and SystemicKO mice, but not TotalKO or KidneyKO animals. In contrast, soluble, amino-terminal extracellular catalytic domain ACE2 is detectable in the urine of WT, KidneyKO, and SystemicKO mice. Data expressed as mean±SEM. Plasma and urine ACE2 activity data analyzed as one-way ANOVA with Dunn multiple comparison test. N=5–7 animals per group. *P<0.05, versus WT.

We next compared ACE2 activity in the urine among the four groups. As expected, ACE2 activity in urine was absent in TotalKO mice (Figure 3B). Urinary ACE2 activity was present in the SystemicKO group (127.62±65.91 RFU/µl per hour) but tended to be reduced compared with WT (289.49±72.37 RFU/µl per hour, P=0.49), indicating the kidney is a major source of ACE2 in urine. Unexpectedly, ACE2 activity was also easily detected in urine from KidneyKO mice at levels not different from controls (306.95±179.52 RFU/µl per hour, P=0.99) despite genetic elimination of ACE2 from the transplanted kidney. Thus, in KidneyKO mice, enzymatically active ACE2 derived from systemic (nonrenal) sources reaches the kidney and is excreted in the urine during AngII-mediated hypertension.

To further characterize the nature of ACE2 in urine during AngII-mediated hypertension, we measured ACE2 protein by immunoblot with an antibody generated against the extracellular amino-terminus domain, expected to be present in both full-length ACE2 and sACE2 (Figure 3C). In the WT group, we detected two species of immunoreactive ACE2 at 98 and 62 kD, consistent with full-length and sACE2 moieties, respectively (29,30). Similarly, both forms of ACE2 were detected in urine of SystemicKOs, although the relative amounts of the smaller ACE2 fragment appeared to be reduced, in parallel with activity levels (Figure 3C). Although neither full-length ACE2 nor sACE2 was detected in urine from TotalKO mice as expected, prominent immunoreactive bands representing sACE2 were detected in urine from KidneyKO mice (Figure 3C). We did not detect any full-length ACE2 in the urine from KidneyKO mice, suggesting that, in the absence of endogenous kidney ACE2, only smaller sACE2 is able to reach the lumen of the nephron. Furthermore, given that the transplanted kidney in KidneyKO mice lack all ACE2 expression, the sACE2 detected in the urine must have originated outside the kidney.

Detection of ACE2 Fragments in Early Glomerular Filtrate

The finding of sACE2 in urine of KidneyKOs suggests sACE2 is being filtered at the glomerulus into the nephron and is excreted in the urine of mice. To examine this possibility, we directly sampled early glomerular filtrate from the Bowman’s space using multiphoton micropuncture followed by nanoproteomics. In samples obtained with this technique, systemic peptides are typically over-represented relative to the very low levels of kidney-specific peptides (21). In addition, this methodology allows the use of mass spectrometry in fluid specifically aspirated from the urinary space in a single nephron. After tryptic digest and mass spectrometry of the aspirated early glomerular fluid, sequence analysis demonstrated multiple, highly-specific peptides of ACE2 in the filtrate. Comparison of peptides recovered from plasma and recombinant ACE2 demonstrates identical peptides in plasma and glomerular filtrate, and similar patterns of coverage, particularly that centered around the most highly significant ACE2 identification peptide (R.QLQALQQSGSSALSADKNK.Q), with the sequence start at ACE2 amino acid position 95 (aa95). Together, these data strongly support the presence of sACE2 in the glomerular filtrate. To assess the relative contribution of the soluble fraction of ACE2 within samples, we compared recovered peptides from the soluble ectodomain (those with sequence endings at position <aa709) with those from the endodomain (sequence ending ≥aa709). As expected, no peptides were identified in the recombinant ACE2 sample after the ADAM17 cleavage site, because this preparation is truncated at aa740. The relative presence of endodomain- versus ectodomain-derived peptides was similar between plasma and glomerular filtrate samples (P=0.3), suggesting plasma can serve as the source of ACE2 in glomerular filtrate. Figure 4 summarizes the sequence alignments of peptides recovered from the three types of samples. Our direct sampling of ACE2 peptides from the glomerular filtrate strongly supports the filtration of systemically derived sACE2.

Figure 4.

ACE2 is detected in the glomerular filtrate by nanoproteomics. Highly significant (e-value<0.05) ACE2-aligned peptides are similar in glomerular filtrate, plasma, and recombinant ACE2-derived samples. The x axis is the amino acid position within the sequence of ACE2_MOUSE. Each significantly aligned peptide is displayed as a bar with length equal to the peptide sequence length and starting position along the x axis equal to the ACE2_MOUSE alignment starting position. The y axis displays the ranked frequency of each identified peptide, with more frequently identified peptides appearing at higher rank. A vertical line at position 709 represents the ADAM17 cleavage site between endo- and ectodomain. FL-ACE2, full-length ACE2; sACE2, soluble ace2.

Discussion

As an integrated network of signaling cascades with broad expression throughout the body, the RAS coordinates key renal and cardiovascular functions. Here, we have uncovered an additional and novel layer of RAS regulation involving ACE2. This study builds on our prior work that identified ACE2 as a modulator of intrarenal RAS and hypertension. Here, we show that, in response to AngII-mediated hypertension, sACE2 is shed from cells outside of the kidney, enters the circulation, and crosses the glomerular filtration barrier, ultimately being excreted in the urine.

Following our earlier findings of enhanced hypertension and elevated renal AngII levels in mice completely deficient in ACE2, we hypothesized that ACE2 within the kidney serves as a critical regulator of BP through its actions to metabolize AngII and diminish its effects to promote renal sodium reabsorption (12). We reasoned that mice lacking ACE2 in the kidney (KidneyKO and TotalKO) would have an exaggerated BP response to AngII infusion, compared with SystemicKO and WT groups, which retained normal expression of ACE2 in kidney. Whereas mean BPs in the TotalKO group were numerically higher than the other three groups throughout the AngII infusion period (Figure 2A, Table 1), these differences did not reach statistical significance. This may have been due to unusual variability in BP values and high mortality during this complex study requiring multiple surgeries (22,23,27). Nonetheless, cardiac hypertrophy was significantly exaggerated in TotalKOs compared with WTs, which was also seen in global ACE2 KOs and typically correlates with increased pressure load in experimental models of hypertension (26,31). Another surrogate marker suggesting higher sustained BP in TotalKO mice was the significantly elevated levels of albuminuria, also likely indicative of elevated BP and consequent renal injury. Although we do not have other markers of damage to the filtration barrier, such as nephrin levels, the markedly elevated levels of albuminuria indicate significant damage because we have previously reported that nephrinuria correlates with both albuminuria and podocyte dropout (32).

A truncated, circulating from of ACE2 (sACE2) can be produced by cleavage of the extracellular domain of ACE2 by metalloproteinases, such ADAM17 also known TACE (29,33,34). Studies by Xiao et al. (35) demonstrated ACE2 exhibits constitutive shedding of enzymatically active fragments, which can be stimulated by AngII or glucose. We reasoned that the somewhat unexpected finding of ACE2 enzymatic activity in the urine of KidneyKO mice might be due to the presence of a cleaved sACE2 originating outside of the kidney, because renal expression of ACE2 is absent in KidneyKOs.

Although it has been identified as a potential biomarker (36), the biologic and clinical significance of ACE2 ectodomain shedding is yet to be fully characterized. We propose that ACE2 shed from extrarenal sources, as in KidneyKO mice, can be filtered to reach the luminal surface of the nephron to affect disease processes dependent on upregulation of the intrarenal RAS. Furthermore, modulation of shedding by enhancement or inhibition of enzymes, such as ADAM17, could have therapeutic potential in hypertension and other kidney diseases. Although Xia et al. demonstrated that shedding of ACE2 into the cerebrospinal fluid effectively removes it from exerting actions in the RAS centers of the central nervous system, our studies suggest shedding of ACE2 in the systemic circulation actually allows it to gain access to the kidney, where it can affect actions of AngII and the intrarenal RAS (19). Thus, ACE2 shedding appears to influence physiologic functions in a system-dependent manner.

On the basis of our findings, we suggest that enzymatically active fragments of ACE2 in urine may play a key role in BP control, such as defending against acute increases in BP induced by AngII. ACE2 shed into the lumen of the nephron would be optimally positioned to metabolize AngII along the length of the nephron, extinguishing its physiologic actions, while also generating Ang1–7, which may have independent effects to ameliorate hypertension (37). Limited samples prevented us from assessing full peptide profiles in these transplanted animals, but our prior report of strong correlation between renal AngII levels and hypertension suggest renal angiotensin peptides play a key role in regulating BP and the intrarenal RAS. The presence of full-length ACE2 (in addition to sACE2) in the urine of WT and SystemicKO mice may represent another mechanism by which ACE2 can be released from kidney cells, such as the proximal tubule, through cell shedding, to extend its activity along the nephron to regulate the RAS. The presence of urinary sACE2 in the KidneyKOs, derived from systemic sources, may represent a means of extrarenal compensation against sustained, exaggerated hypertension. Our proteomics analysis confirms ACE2 peptides are present in early glomerular filtrate, likely originating from plasma that demonstrated a similar profile of sACE2 fragments. The direct micropuncture approach circumvents potential confounding influence of ACE2 peptides originating from renal epithelial cells or more distal urologic sources, including the bladder. Our assays of the early filtrate provide a clear explanation for our findings in the crosstransplantation studies, establishing a pathway by which sACE2 reaches the lumen of kidney tubules and is excreted in urine.

In the future, it will be important to identify the specific cellular origins of extrarenal circulating sACE2 and the signaling pathways controlling its shedding. ACE2 was originally identified from the cardiac ventricular tissue and is highly expressed in kidney, indicating robust expression in cardiovascular tissues, which may serve as important sources of sACE2. Future studies could address the mechanism(s) of shedding and release of ACE2 from the cell surface, likely mediated by enzymes such as ADAM17 as in other tissues (35,36). On the basis of our findings, we anticipate the modulators of this regulatory process might be promising therapeutic targets in hypertension and other kidney diseases.

Disclosures

T.M. Coffman reports serving in an advisory or leadership role for Cell Metabolism and The Journal of Clinical Investigation (editorial boards), Kidney Research Institute University of Washington, Singapore Eye Research Institute, and the Singapore Health Services (board of directors). S.B. Gurley serving as Associate Editor for the Diabetes and a family member being employed by, and having ownership interest in, United Therapeutics. M.P. Hutchens reports having ownership interest in ATT, Exxon, Frontier, and Verizon; and having patents or royalties with ProjectLite, LLC. P.D. Piehowski reports receiving research funding from Jacobs (worldwide research principal investigator) and Pfizer; and being employed by, and having patents or royalties with, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. R. Wakasaki reports having ownership interest in Fuji Film Holdings, KDDI, Lion, and Toyota. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The following funding sources supported this work: American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Foundation for Kidney Research grant 2009 Alaska Kidney Foundation (S.B. Gurley); National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants R01 DK098382 (S.B. Gurley), P30 DK096493 (S.B. Gurley), 5T32 DK00773 (D.I. Ortiz-Melo), and K01DK121737 (J.W. Nelson); American Heart Association Grant in Aid (S.B. Gurley); NIH grants 5T32GM109835-03 and 5TL1TR002371-04 (J.M. Emathinger); and US Department of Veterans Affairs grant I01BX004288A1 (M.P. Hutchens).

Footnotes

See related editorial, “ACE2 in the Urine: Where Does It Come From?,” on pages 2001–2004.

Author Contributions

T.M. Coffman, J.M. Emathinger, S.B. Gurley, M.P. Hutchens, J.W. Nelson, and D.I. Ortiz-Melo reviewed and edited the manuscript; T.M. Coffman, S.B. Gurley, and D.I. Ortiz-Melo conceptualized the study; T.M. Coffman and S.B. Gurley provided supervision; J.M. Emathinger, R.C. Griffiths, S.B. Gurley, M.P. Hutchens, N.K. Mattocks, D.I. Ortiz-Melo, P.D. Piehowski, J. Prescott, R. Wakasaki, and K. Xu performed experiments; J.M. Emathinger, S.B. Gurley, M.P. Hutchens, and J.W. Nelson were responsible for visualization; S.B. Gurley was responsible for funding acquisition, project administration, and resources; S.B. Gurley, M.P. Hutchens, J.W. Nelson, and D.I. Ortiz-Melo wrote the original draft and were responsible for data curation; S.B. Gurley, M.P. Hutchens, J.W. Nelson, D.I. Ortiz-Melo, J.M. Emathinger, and P.D. Piehowski were responsible for formal analysis; S.B. Gurley, M.P. Hutchens, D.I. Ortiz-Melo, and P.D. Piehowski were responsible for methodology; S.B. Gurley, M.P. Hutchens, and D.I. Ortiz-Melo were responsible for validation; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

All data are included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.

References

- 1.Donoghue M, Hsieh F, Baronas E, Godbout K, Gosselin M, Stagliano N, Donovan M, Woolf B, Robison K, Jeyaseelan R, Breatbart R, Acton S: A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1-9. Circ Res 87: E1–E9, 2000. 10.1161/01.RES.87.5.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santos RA, Simoes e Silva AC, Maric C, Silva DM, Machado RP, de Buhr I, Heringer-Walther S, Pinheiro SV, Lopes MT, Bader M, Mendes EP, Lemos VS, Campagnole-Santos MJ, Schultheiss HP, Speth R, Walther T: Angiotensin-(1-7) is an endogenous ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor Mas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 8258–8263, 2003. 10.1073/pnas.1432869100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tipnis SR, Hooper NM, Hyde R, Karran E, Christie G, Turner AJ: A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem 275: 33238–33243, 2000. 10.1074/jbc.M002615200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong DW, Oudit GY, Reich H, Kassiri Z, Zhou J, Liu QC, Backx PH, Penninger JM, Herzenberg AM, Scholey JW: Loss of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) accelerates diabetic kidney injury. Am J Pathol 171: 438–451, 2007. 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soler MJ, Wysocki J, Ye M, Lloveras J, Kanwar Y, Batlle D: ACE2 inhibition worsens glomerular injury in association with increased ACE expression in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Kidney Int 72: 614–623, 2007. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crackower MA, Sarao R, Oudit GY, Yagil C, Kozieradzki I, Scanga SE, Oliveira-dose-Santos AJ, da Costa J, Zhang L, Pei Y, Scholey J, Ferrario CM, Manoukian AS, Chappell MC, Backx PH, Yagil Y, Penninger JM: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature 417: 822–828, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burrell LM, Johnston CI, Tikellis C, Cooper ME: ACE2, a new regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. Trends Endocrinol Metab 15: 166–169, 2004. 10.1016/j.tem.2004.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shang J, Wan Y, Luo C, Ye G, Geng Q, Auerbach A, Li F: Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117: 11727–11734, 2020. 10.1073/pnas.2003138117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q: Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 367: 1444–1448, 2020. 10.1126/science.abb2762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen D, Li X, Song Q, Hu C, Su F, Dai J, Ye Y, Huang J, Zhang X: Assessment of hypokalemia and clinical characteristics in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wenzhou, China. JAMA Netw Open 3: e2011122, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sparks MA, South A, Welling P, Luther JM, Cohen J, Byrd JB, Burrell LM, Batlle D, Tomlinson L, Bhalla V, Rheault MN, Soler MJ, Swaminathan S, Hiremath S: Sound science before quick judgement regarding RAS blockade in COVID-19. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 714–716, 2020. 10.2215/CJN.03530320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gurley SB, Allred A, Le TH, Griffiths R, Mao L, Philip N, Haystead TA, Donoghue M, Breitbart RE, Acton SL, Rockman HA, Coffman TM: Altered blood pressure responses and normal cardiac phenotype in ACE2-null mice. J Clin Invest 116: 2218–2225, 2006. 10.1172/JCI16980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wysocki J, Ortiz-Melo DI, Mattocks NK, Xu K, Prescott J, Evora K, Ye M, Sparks MA, Haque SK, Batlle D, Gurley SB: ACE2 deficiency increases NADPH-mediated oxidative stress in the kidney. Physiol Rep 2: e00264, 2014. 10.1002/phy2.264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamazato M, Yamazato Y, Sun C, Diez-Freire C, Raizada MK: Overexpression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in the rostral ventrolateral medulla causes long-term decrease in blood pressure in the spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 49: 926–931, 2007. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000259942.38108.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rentzsch B, Todiras M, Iliescu R, Popova E, Campos LA, Oliveira ML, Baltatu OC, Santos RA, Bader M: Transgenic angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 overexpression in vessels of SHRSP rats reduces blood pressure and improves endothelial function. Hypertension 52: 967–973, 2008. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.114322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu CX, Hu Q, Wang Y, Zhang W, Ma ZY, Feng JB, Wang R, Wang XP, Dong B, Gao F, Zhang MX, Zhang Y: Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 2 overexpression ameliorates glomerular injury in a rat model of diabetic nephropathy: A comparison with ACE inhibition [published correction appears in Mol Med 28: 53, 2022]. Mol Med 17: 59–69, 2011. 10.2119/molmed.2010.00111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto K, Ohishi M, Katsuya T, Ito N, Ikushima M, Kaibe M, Tatara Y, Shiota A, Sugano S, Takeda S, Rakugi H, Ogihara T: Deletion of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 accelerates pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction by increasing local angiotensin II. Hypertension 47: 718–726, 2006. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000205833.89478.5b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai ZW, Hanchapola I, Steer DL, Smith AI: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 ectodomain shedding cleavage-site identification: Determinants and constraints. Biochemistry 50: 5182–5194, 2011. 10.1021/bi200525y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xia H, Sriramula S, Chhabra KH, Lazartigues E: Brain angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2 shedding contributes to the development of neurogenic hypertension. Circ Res 113: 1087–1096, 2013. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Navar LG, Satou R, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA: The increasing complexity of the intratubular Renin-Angiotensin system. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1130–1132, 2012. 10.1681/ASN.2012050493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wakasaki R, Matsushita K, Golgotiu K, Anderson S, Eiwaz MB, Orton DJ, Han SJ, Lee HT, Smith RD, Rodland KD, Piehowski PD, Hutchens MP: Glomerular filtrate proteins in acute cardiorenal syndrome. JCI Insight 4: 4, 2019. 10.1172/jci.insight.122130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crowley SD, Gurley SB, Oliverio MI, Pazmino AK, Griffiths R, Flannery PJ, Spurney RF, Kim HS, Smithies O, Le TH, Coffman TM: Distinct roles for the kidney and systemic tissues in blood pressure regulation by the renin-angiotensin system. J Clin Invest 115: 1092–1099, 2005. 10.1172/JCI23378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu PL, Gigliotti JC, Cechova S, Bodonyi-Kovacs G, Chan F, Ralph DL, Howell N, Kalantari K, Klibanov AL, Carey RM, McDonough AA, Le TH: Renal collectrin protects against salt-sensitive hypertension and is downregulated by angiotensin ii. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1826–1837, 2017. 10.1681/ASN.2016060675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gurley SB, Riquier-Brison ADM, Schnermann J, Sparks MA, Allen AM, Haase VH, Snouwaert JN, Le TH, McDonough AA, Koller BH, Coffman TM: AT1A angiotensin receptors in the renal proximal tubule regulate blood pressure. Cell Metab 13: 469–475, 2011. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dolina JS, Cechova S, Rudy CK, Sung SJ, Tang WW, Lee J, Hahn YS, Le TH: Cross-presentation of soluble and cell-associated antigen by murine hepatocytes is enhanced by collectrin expression. J Immunol 198: 2341–2351, 2017. 10.4049/jimmunol.1502234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crowley SD, Gurley SB, Herrera MJ, Ruiz P, Griffiths R, Kumar AP, Kim HS, Smithies O, Le TH, Coffman TM: Angiotensin II causes hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy through its receptors in the kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 17985–17990, 2006. 10.1073/pnas.0605545103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gurley SB, Griffiths RC, Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH, Coffman TM: Renal actions of RGS2 control blood pressure. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1847–1851, 2010. 10.1681/ASN.2009121306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crowley SD, Zhang J, Herrera M, Griffiths R, Ruiz P, Coffman TM: Role of AT1 receptor-mediated salt retention in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F1124–F1130, 2011. 10.1152/ajprenal.00305.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambert DW, Yarski M, Warner FJ, Thornhill P, Parkin ET, Smith AI, Hooper NM, Turner AJ: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha convertase (ADAM17) mediates regulated ectodomain shedding of the severe-acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2). J Biol Chem 280: 30113–30119, 2005. 10.1074/jbc.M505111200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye M, Wysocki J, William J, Soler MJ, Cokic I, Batlle D: Glomerular localization and expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin-converting enzyme: Implications for albuminuria in diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3067–3075, 2006. 10.1681/ASN.2006050423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sparks MA, Rianto F, Diaz E, Revoori R, Hoang T, Bouknight L, Stegbauer J, Vivekanandan-Giri A, Ruiz P, Pennathur S, Abraham DM, Gurley SB, Crowley SD, Coffman TM: Direct actions of AT1 (type 1 angiotensin) receptors in cardiomyocytes do not contribute to cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension 77: 393–404, 2021. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang JH, Paik SY, Mao L, Eisner W, Flannery PJ, Wang L, Tang Y, Mattocks N, Hadjadj S, Goujon JM, Ruiz P, Gurley SB, Spurney RF: Diabetic kidney disease in FVB/NJ Akita mice: Temporal pattern of kidney injury and urinary nephrin excretion. PLoS One 7: e33942, 2012. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwata M, Silva Enciso JE, Greenberg BH: Selective and specific regulation of ectodomain shedding of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 by tumor necrosis factor alpha-converting enzyme. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 297: C1318–C1329, 2009. 10.1152/ajpcell.00036.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jia HP, Look DC, Tan P, Shi L, Hickey M, Gakhar L, Chappell MC, Wohlford-Lenane C, McCray PB Jr: Ectodomain shedding of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in human airway epithelia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L84–L96, 2009. 10.1152/ajplung.00071.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao F, Zimpelmann J, Agaybi S, Gurley SB, Puente L, Burns KD: Characterization of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 ectodomain shedding from mouse proximal tubular cells. PLoS One 9: e85958, 2014. 10.1371/journal.pone.0085958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salem ES, Grobe N, Elased KM: Insulin treatment attenuates renal ADAM17 and ACE2 shedding in diabetic Akita mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F629–F639, 2014. 10.1152/ajprenal.00516.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santos RA: Angiotensin-(1-7). Hypertension 63: 1138–1147, 2014. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]